1. Introduction

The global wave of population aging is reshaping the world’s social, economic, and spatial landscapes at an unprecedented rate [

1,

2,

3]. By 2050, the global population aged 65 and above will reach 1.6 billion, accounting for approximately 16% of the world’s population [

4]. Against this backdrop, governments around the world have been actively promoting aging-related research [

5]. In particular, the Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities, a concept developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasizes the creation of an age-friendly environment [

6] that enhances elderly individuals’ ability to gain access to the required places (physical environment) and to the required people (social environment) [

7] to enable them to continue to participate in social, economic, livelihood, and sporting activities and to guarantee their quality of life as they age [

8].

By the end of 2024, the elderly population aged 60 and above accounted for 22.0% of the total population in China, while the elderly population aged 65 and above accounted for 15.6% of the total population, representing increases of 5.9% and 5.1%, respectively, compared to the data regarding 2015, demonstrating a trend of gradual increase year by year [

9]. China, as one of the countries with the most rapidly aging populations in the world [

10], faces greater challenges in rural areas, where the aging rate is significantly higher than in cities due to the outmigration of young adults and declining fertility [

11]. This leads to a growing phenomenon of “aging depression,” characterized by sparse elderly populations and weak service provision [

12]. Meanwhile, in the process of China’s urbanization, rural areas are in a disadvantaged position in terms of policy support [

13], resource allocation, and infrastructure construction. This development imbalance has led to a serious mismatch between public activity space supply and the demands of elderly rural residents, making it difficult to meet their needs for daily communication and recreation [

14].

In recent years, China has implemented a rural revitalization strategy, injecting new development opportunities into rural construction [

15]. However, in some remote villages with low population density and dispersed elderly residents, large-scale age-friendly adaptations are both costly and likely to be underutilized, thereby posing challenges in realizing the anticipated economic benefits [

16]. Suburban rural areas, as a special geographical unit [

17], offer more favorable conditions due to their proximity to cities, higher population density, and better infrastructure [

18]. Additionally, the trend of part-time employment and non-farming in suburban villages has diversified villagers’ lifestyles, blending urban and rural habits [

19]. Hence, the age-friendly transformation of suburban rural public spaces must reconcile both modern and traditional needs rather than applying a uniform urban-centric model.

This study takes Jiashan Village in Wuhan City as an example and aims to achieve three breakthroughs by integrating the spatial–temporal behavior analysis of new time–geography with the hierarchical framework of Maslow’s needs theory by first dynamically analyzing the spatial–temporal differentiation of elderly activity patterns and their correlation with emotional changes and identifying the priority of differentiated transformation; secondly, an evaluation model of demand space satisfaction is constructed to quantify the interaction between facility usage and emotional feedback; and, thirdly, a multi-subject collaborative age-friendly adaptation strategy is proposed to promote the transformation of suburban and rural areas from passive adaptation to active empowerment, providing a theoretical and practical basis for addressing aging depression and urban–rural integration development.

To situate these objectives within the existing body of knowledge, it is necessary to review how age-friendly retrofitting research has evolved internationally and within China, and to identify the theoretical gaps that this study seeks to fill.

2. Literature Review

Over the past few decades, both theoretical research and practical efforts in age-friendly retrofitting have achieved notable progress worldwide [

20]. A growing consensus among scholars emphasizes that standards for such transformations should be grounded in the specific needs of the elderly population [

21,

22]. Developed countries, which encountered aging challenges earlier [

23], initiated studies on age-friendly environments as early as the 1990s [

24]. Their development can be broadly divided into three key phases.

In the first phase, the focus was on the material dimension of space. Retrofitting strategies were led primarily by architectural and engineering perspectives, emphasizing standardized and universal design principles for barrier-free environments. Older adults were often viewed as a homogeneous group. For example, France’s Planning and Design for the Elderly established criteria for age-friendly public spaces in rural areas [

25], while Japan’s Welfare Law for Rural Areas introduced differentiated facilities based on village aging rates [

26].

In the second phase, attention shifted to the social dimension of aging. Researchers began to recognize the heterogeneity in health status, psychological conditions, and social engagement among elderly individuals [

27]. In the early 2000s, the U.S. introduced the concept of Active Adult Retirement Communities (AARCs) in suburban settings [

28], classifying seniors into “active” (65–75), “frail” (75–85), and “dependent” (85+) categories and designing spatial and service strategies accordingly [

29].

The third phase marks the rise of technologically precise approaches. With advances in big data and smart technologies, age-friendly transformation has become increasingly data-driven. This phase emphasizes accurately identifying user needs through real-time monitoring and intelligent systems. For instance, in Maryland, wearable sensor data are used to track seniors’ movement patterns and facility usage, enabling dynamic and responsive adjustments in service provision [

30]. Collectively, these developments illustrate an evolution from physical infrastructure to social interaction and then to intelligent response systems. This “material–social–technological” trajectory offers a comprehensive, systematic, and adaptable theoretical framework.

In comparison, China entered an aging society relatively late, in 1999 [

31]. Although the research on age-friendly transformation started later, it has achieved notable progress over the past two decades. The early studies focused on the relationship between older adults and the physical environment. Scholars such as Zhou Yanmin were pioneers in proposing age-friendly design principles for residential areas [

27]. Later, researchers like Li Yuanyuan systematically examined the physical, social, cultural, and institutional dimensions of age-friendliness, building a comprehensive and sustainable framework for transformation [

32]. With the rise of big data and related technologies, scholars such as Wang Luyu further explored community planning strategies based on the spatial–temporal behavior of elderly individuals at the micro scale [

33].

However, despite the progress achieved in age-friendly environmental research, three major limitations remain. First, most existing studies are urban-centric, lacking adaptive exploration into the living characteristics and spatial constraints of the rural elderly [

34]—particularly those residing in suburban village contexts. As a result, the applicability of these studies to rural settings remains limited [

35]. Second, the current research tends to rely excessively on single-dimensional demographic classifications, overlooking the dynamic differentiation in the spatial–temporal behavior patterns of older adults. This reductionist approach has led to the widespread adoption of top-down supply-driven retrofitting strategies, resulting in mismatched facilities and inefficient spatial use [

36]. Consequently, the complex needs of rural elderly individuals—ranging from service accessibility and social interaction to personal value realization—are often inadequately addressed [

37]. Third, the existing studies often focus on physical improvements at the micro scale while neglecting the dynamic interrelationships among behavior, emotion, and space [

38,

39]. They fail to acknowledge how emotional feedback influences spatial perception and satisfaction, thus limiting the human-centered depth of age-friendly transformation strategies [

40]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop an age-friendly public space retrofitting framework that is tailored to rural contexts and responsive to the diverse needs of elderly residents.

To address these shortcomings, scholars have turned to theoretical perspectives that can better capture the dynamics of elderly behavior and needs. Among them, the space–time path approach of new time–geography provides a valuable analytical tool. Compared with the traditional time–geography proposed by Hagstrom, this theory shifts from “absolute spacetime” to “relative spacetime”, emphasizing the dynamic relationship between social and cultural constraints and individual organizational interactions [

41]. It can accurately capture the spatial–temporal behavior patterns of elderly people in their “daily life circle” and reveal the coupling mechanism between their activity preferences and emotional needs [

42]. At the same time, the hierarchical logic of Maslow’s needs theory can further map behavioral characteristics to the hierarchy of needs [

43,

44], providing value orientation for spatial optimization. The combination of the two can not only make up for the shortcomings of the existing research in behavioral dynamics and demand complexity but also provide a systematic path for the coordinated optimization of a “space service system” for the age-friendly adaptation of suburban and rural areas [

45].

4. Results

4.1. Activity Space Needs of Elderly with Different Lifestyles Based on the New Time–Geography

The research team randomly selected 30 elders (15 male and 15 female) aged 55+. All the participants were informed about the purpose of the study (life situation, movement trajectory, and emotions), anonymity and data confidentiality, device security, and the right to withdraw at any time. After the notification was completed, the experimenter confirmed that the subjects fully understood the situation and agreed to participate in the experiment.

The classification of elderly lifestyles was derived from a combination of GPS trajectory data, questionnaire responses, and interview information. First, individual space–time paths were constructed from GPS tracking records to capture daily activity duration, travel distance, and spatial range. Second, the questionnaire items relating to daily routines, household responsibilities, and social participation were integrated to supplement the behavioral data. Third, the semi-structured interviews provided qualitative insights into the underlying motivations for activity choices. Based on these data, a clustering analysis was performed, and four representative lifestyle types were identified (

Figure 7).

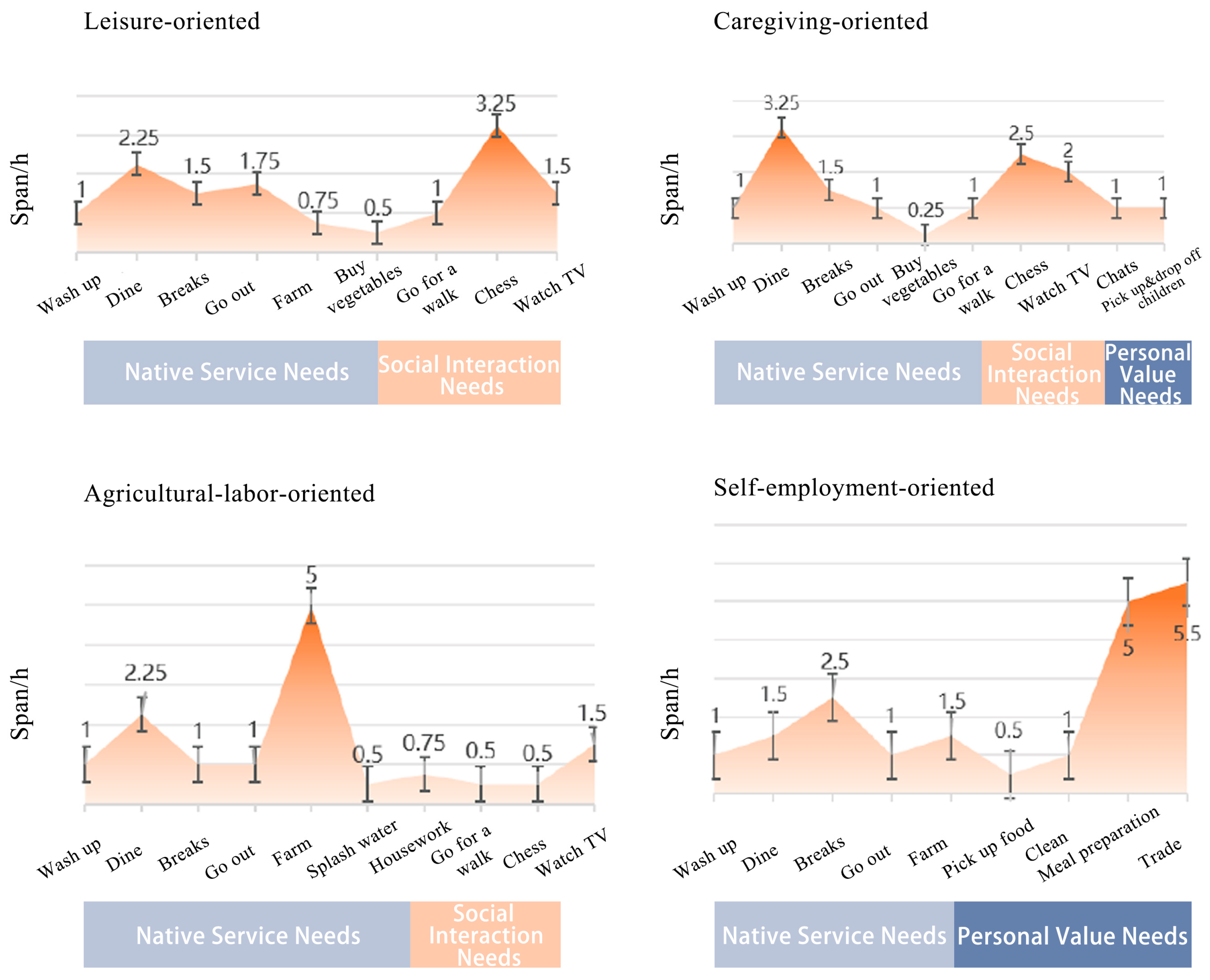

Summarizing the lifestyle and spatial–temporal behavioral characteristics of the four types of elderly individuals, they can be categorized as follows: the leisure-oriented type (1), the caregiving-oriented type (2), the agricultural-labor-oriented type (3), and the self-employment-oriented type (4). Specifically, the leisure-oriented type refers to elderly people whose all-day activities are mainly leisure activities, with less than 2 h of labor, such as farming and business; the caregiving-oriented type refers to elderly people whose all-day activities include childcare, transporting and accompanying children for more than 4 h; the agricultural-labor-oriented type refers to elderly people whose all-day activities are mainly farming activities, with more than 4 h of labor, such as ploughing and chopping wood; and the self-employment-oriented type refers to elderly people whose all-day activities mainly involve self-employment, with more than 6 h of labor, such as laboring or looking after a shop.

From the planning of the daily lives of the elderly in the four types of lifestyles, there are some differences in the types of activities and spaces, the magnitude of emotional fluctuations, and the richness of social interaction among the elderly (

Table 3).

To complement the space–time path analysis, this study additionally employs a planar color-block representation to highlight the spatial distribution of behavioral events at different time periods within Jiashan Village (

Figure 8). By mapping morning (6:00–9:00), midday (10:00–14:00), afternoon (15:00–18:00), and evening (19:00–22:00) activities onto the village plan, the visualization reveals clear spatial clustering of the user behaviors. For instance, the agricultural-labor-oriented seniors show concentrated activity blocks around the farmland and irrigation facilities in the morning, while the leisure-oriented seniors exhibit stronger clustering in the public plazas and riverside walkways during the afternoon. The caregiving-oriented elders are more active around homesteads and near children’s play areas, particularly in the evening, whereas the self-employment-oriented elders remain centered around the household–commercial nodes throughout the day.

Analyzing the activity needs of the four categories of elderly people on this basis, from the results of the analysis (

Figure 9), the leisure-oriented seniors have the most urgent need and free time for social public spaces, including the chess and card rooms, small plazas, and river walks, which combine intergenerational interaction, children’s companionship, and emotional adjustment for seniors. The agricultural-labor-oriented type of elderly people have less free time, and their daily life revolves around their own land and farmland, with occasional recreational activities, such as shopping and card games. They have the most prominent demand for the refinement of the waterfront steps and farmland irrigation facilities. For the caregiving-oriented type of elderly people, the most important thing for them is to take care of their grandchildren, transport them to and from their farms, keep them company, and play games, and they have more time for recreation. Those elderly who are self-employed have the least amount of time for leisure and recreation and are mainly engaged in business activities every day, rarely using the recreational facilities in the village. Linear recreational spaces such as walking paths and waterfront trails play a significant role in restoring their emotions.

4.2. Satisfaction with and Reasons for Aging of Existing Activity Spaces

Processing the emotional scoring results, combined with the data of the spatial–temporal behaviors of the elderly, we obtain the emotional scores of the elderly with different lifestyles in daily life activities (

Figure 10), and the comprehensive satisfaction scores, to understand the satisfaction of the elderly in different spaces and to conduct corresponding analyses (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

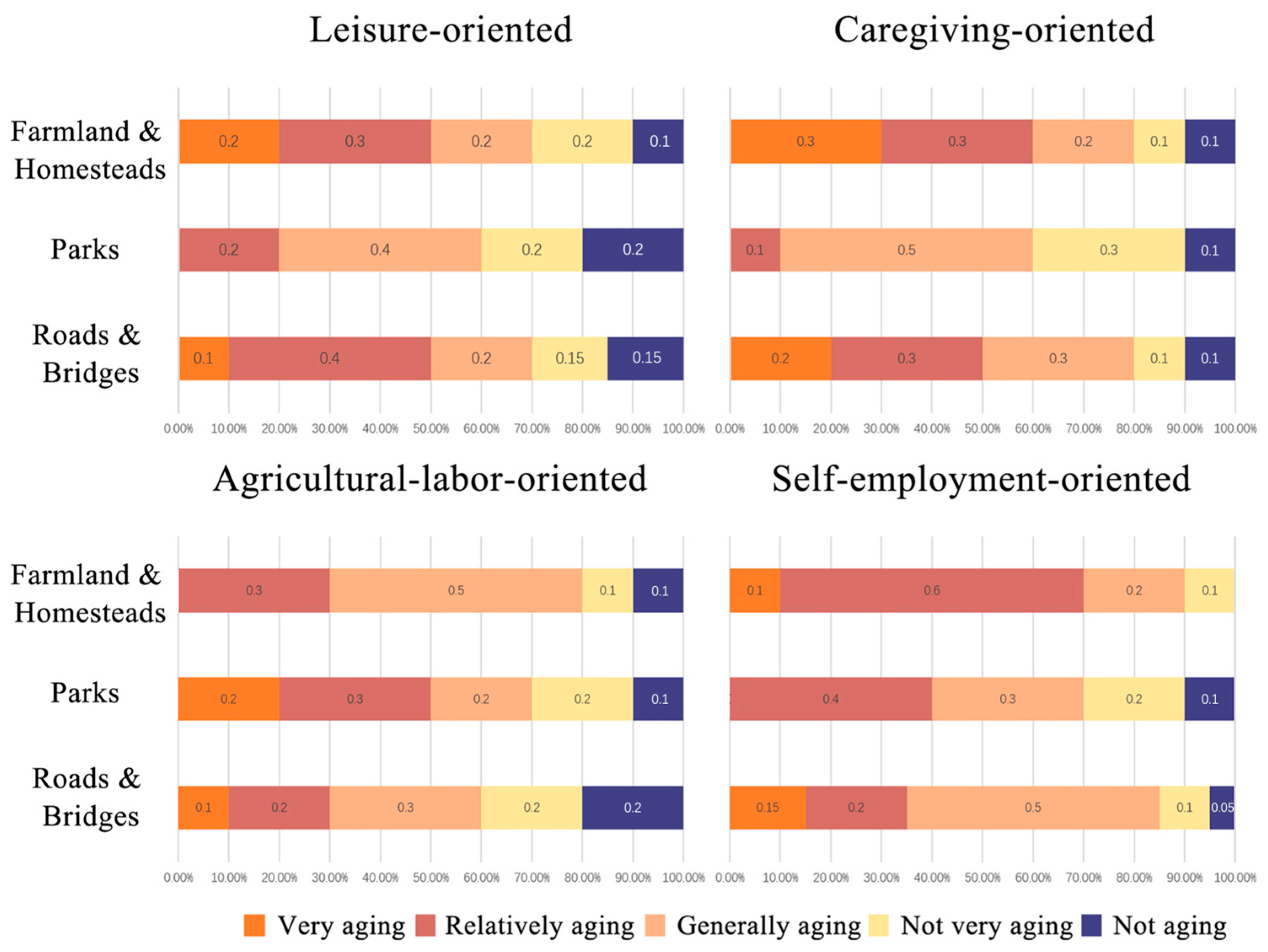

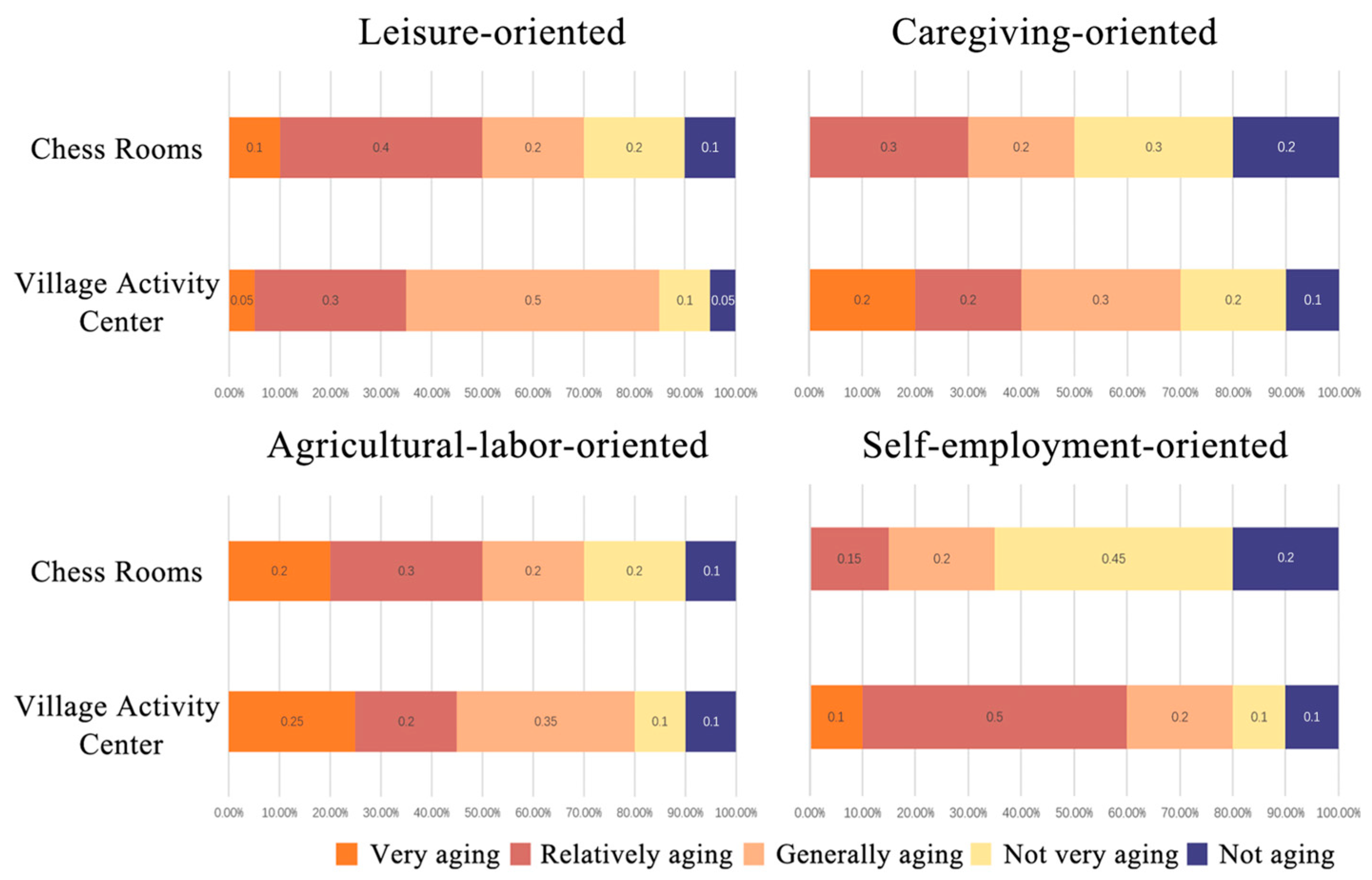

With regard to the outdoor environment, in terms of satisfaction with farmland and homesteads, more elderly people in the agricultural-labor-oriented category consider them to be “very suitable for the elderly”. With regard to parks, except for the caregiving-oriented type, where half of the respondents rated the parks as “more suitable for the elderly” or higher, the satisfaction level of the other three types of elderly people was generally on the lower side of average. With regard to the roads and bridges in the village, half of the elderly people with leisure-oriented and agricultural-labor-oriented lifestyles rated them as “quite suitable for the elderly” or “very suitable for the elderly,” and half of the elderly people with caregiving-oriented and self-employment-oriented lifestyles rated them as “moderately suitable for the elderly”. The largest number of elderly people in the caregiving-oriented and self-employment-oriented lifestyles said that they were “generally comfortable in old age”.

With regard to indoor environments, there are large differences in the evaluation of different indoor environments in relation to different types of lifestyles. Specifically, 50% of the leisure-oriented and caregiving-oriented seniors rated the chess rooms as “quite suitable for the elderly” and above, while very few of the agricultural-labor-oriented and self-employed-oriented seniors rated them as “very suitable for the elderly”, and half of them and more than half of them rated them as not suitable enough. More than half rated them as not old enough. Fewer of the four types of elderly people had a negative attitude towards the village activity center, and 60% of the self-employed elderly people rated the service center as “more suitable for the elderly” or above.

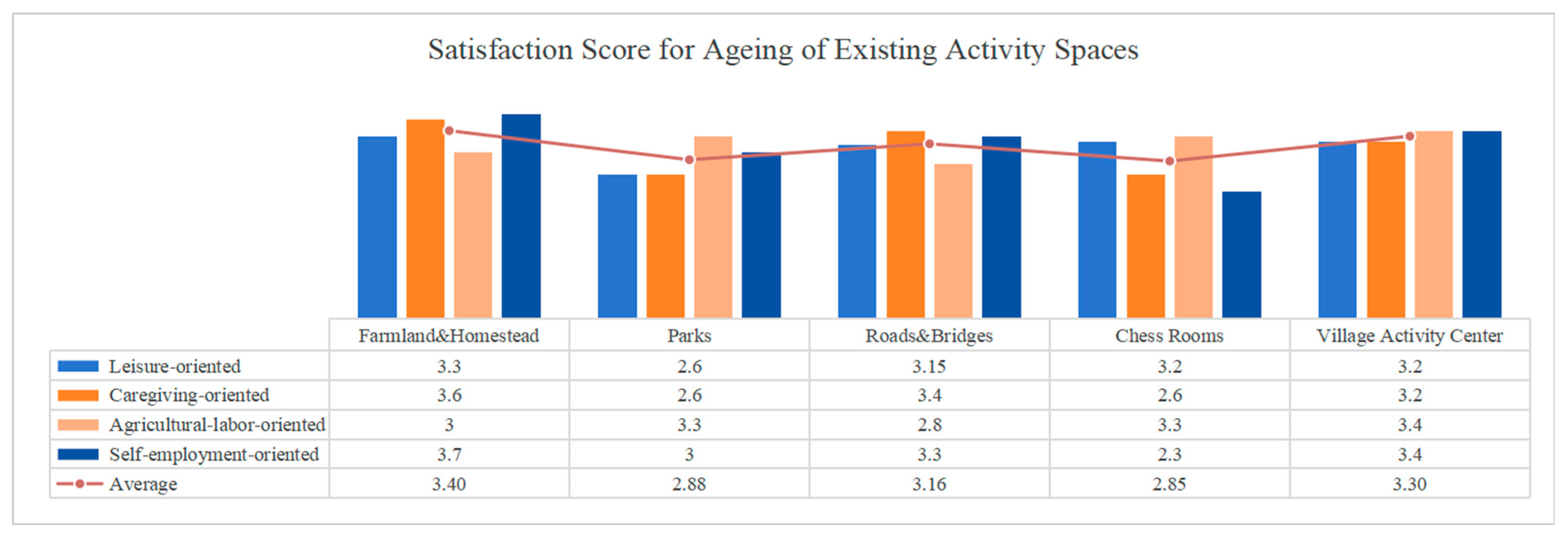

In order to further quantify the differences in satisfaction with the core activity spaces among the different elderly groups, this study integrates the standardized ratings of the above five types of spaces to obtain detailed results (

Figure 13). It can be seen more intuitively that farmland has the highest level of satisfaction, but the satisfaction of the agricultural-labor-oriented type, who uses farmland the most, is the lowest among the four types of seniors; parks and board rooms have the lowest level of satisfaction, and the self-employed type, in particular, only rated the board rooms at 2.3. Overall, the aging-adaptability scores of the various types of spaces are relatively average, fluctuating around the standard line of the “Generally aging” threshold.

The results of the above analyses generally demonstrate the characteristics of different types of elderly people’s use of and satisfaction with activity spaces. In order to better elucidate the differences in choices between respondents and clarify the direction of age-friendly adaptation, this study analyzes the reasons for the results of the space satisfaction scores, taking into account the personal attributes of different types of elderly respondents.

Elderly people’s satisfaction with space is closely related to their companionship in daily life. Combining the spatial and temporal activity characteristics of the elderly to analyze the companionship of different types of elderly people’s lifestyles (

Figure 14), it is evident that the activities of elderly people with leisure-oriented lifestyles are more varied, they have less time to be alone, and the comprehensive aging satisfaction evaluation results show that they have higher satisfaction with their lives. Except for the self-employed elderly, most of the elderly demonstrate good fits between the daily mood change line and the social intimacy line, forming an obvious positive correlation. The richness of the activity types and locations is related to mood: the mood of the self-employed elderly is relatively stable and calm throughout the day, which may be related to the high repetitiveness of the content and locations of their daily activities and the low sense of freshness, while the low mood in the evening may be related to the day’s exertion. The mood of the elderly is also related to the high level of satisfaction in their life when they engage in activities involving social recreation and entertainment. The elderly were generally in better moods when engaging in activities that included social recreation, with subsequent increases in satisfaction with the space.

4.3. Demand and Decision-Making Preferences for Age-Friendly Adaptation of Activity Spaces

Based on the satisfaction evaluation and cause analysis, the study further explores the mechanism and optimization path of age-friendly adaptation. The survey interviews show that the elderly in Jiashan Village have a strong and diversified willingness to undertake age-friendly adaptation of the spaces in the village, and, in order to better explore the specific aging retrofitting approaches, it is also necessary to analyze the actual spaces as well as the preferences of the elderly for retrofitting methods.

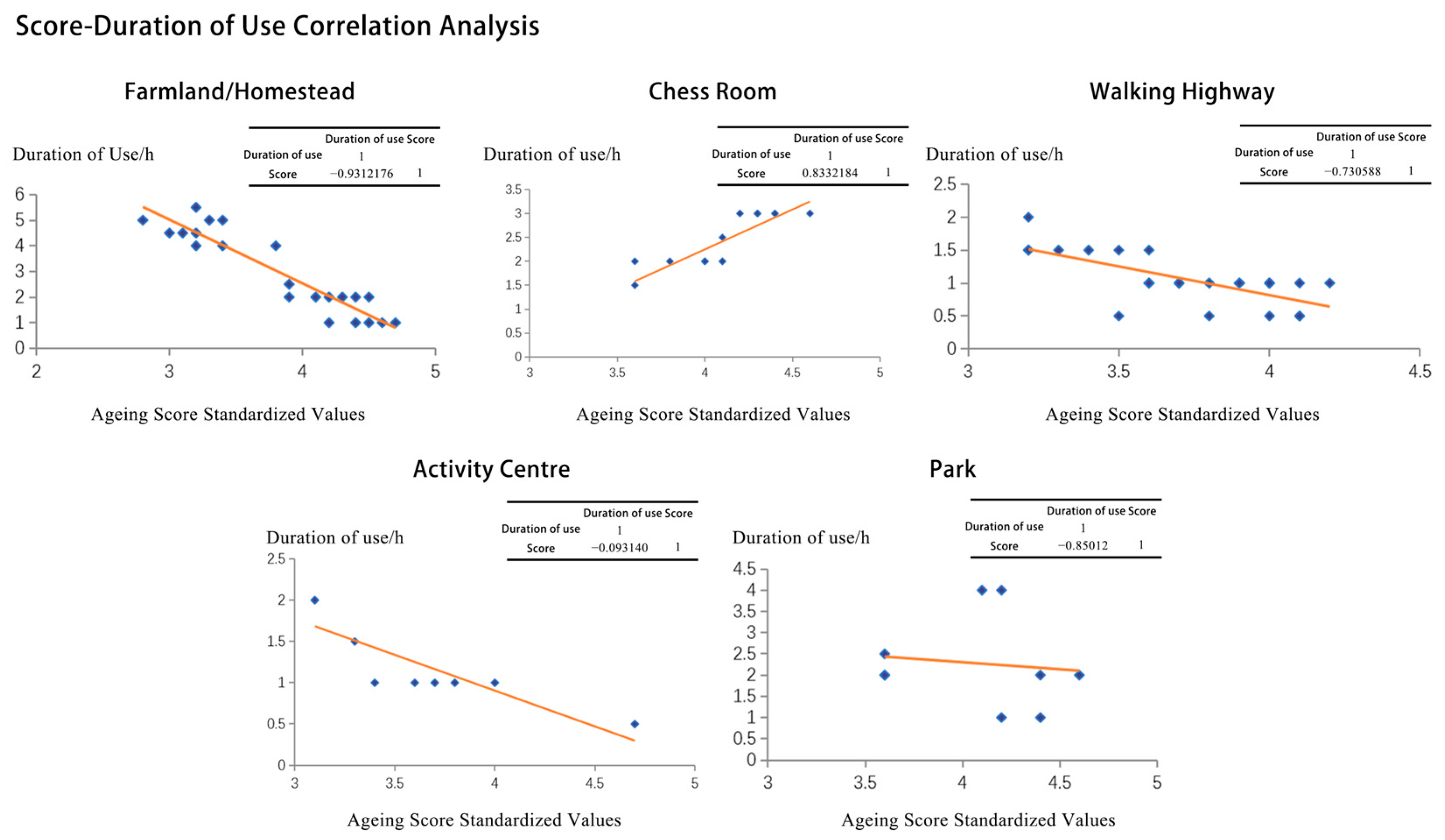

According to the results of the linear regression analysis (

Figure 15), it can be seen that there is a strong negative correlation between the satisfaction scores and usage duration in the farmland/homesteads and parks, a strong positive correlation regarding the chess rooms, a significant negative correlation regarding the walking roads, and no correlation between the satisfaction scores and usage duration in the activity center.

Based on the results of the correlation analysis, it is clear that there is an urgent need for age-friendly improvements to the farmland/homesteads, parks, and walking roads for the elderly. Therefore, the study specifically analyzes typical existing spaces with potential for age-friendly renovation (

Table 4) to understand the deficiencies and age-friendly demands of the existing spaces.

The research team distributed 207 paper questionnaires to the elderly in the village, and 152 valid questionnaires were collected, with an effective recovery rate of 73.4%. The questionnaire results were quantified via the SP method and MNL model to obtain the effects of different influencing elements on the satisfaction of the elderly environment of the community residents in Jiashan Village (

Table 5). The analysis demonstrates that, among the four types of facility modifications, the quality improvement of production and business facilities is the most necessary for farmers, followed by leisure and recreation facilities; in terms of centralized activities, the effect of regular census on the living conditions and difficulties of the elderly is the most significant. Among all the influencing factors, the utility of fine-tuning farmland was significant, with an increase of 1.5873 compared to un-tuned farmland. For recreational facility renovation, the improvement of new facilities was greater than the utility associated with renovating the existing facilities, but both showed a significant effect.

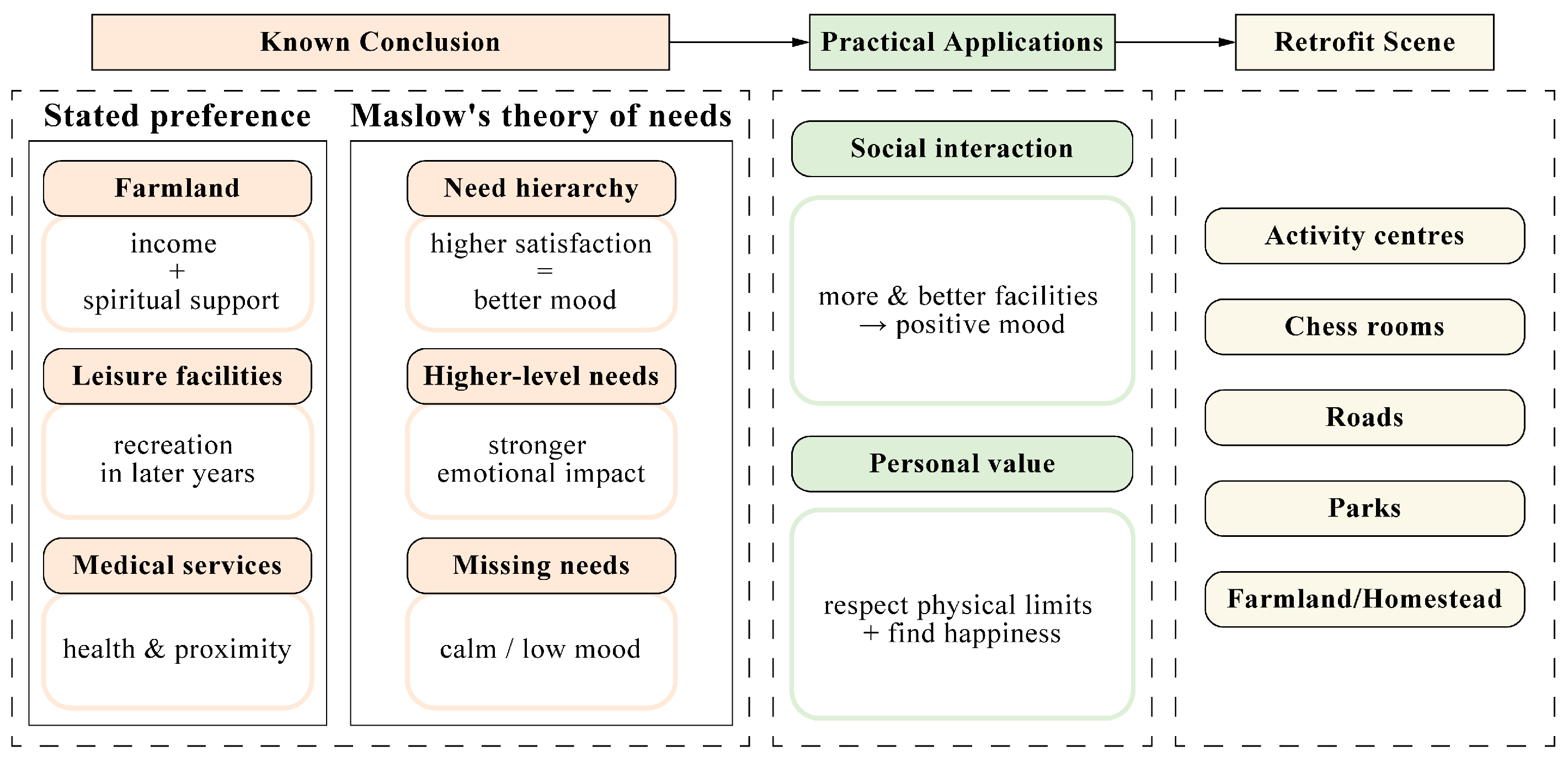

In order to understand the needs of the elderly for age-friendly retrofitting, this study combines Maslow’s theory of needs with the analysis. Maslow’s theory of needs includes a five-level model of human needs, often depicted as a hierarchy within a pyramid. From the bottom of the hierarchy upwards, the needs are physiological, safety, social needs, respect, and self-actualization [

61]. Among them, physiological needs and safety needs are lower-level needs, social needs and respect needs are higher-level needs, and self-actualization needs are the highest-level needs.

On this basis, Maslow’s theory of needs can be further divided into three dimensions: survival needs, belonging needs, and value needs. Survival needs, considered the most basic level of needs, are concerned with sustaining life and basic safety, and, for the elderly, this is reflected in the satisfaction of three meals a day, safe shelter, health protection, avoidance of risks in daily activities, and other basic survival security. After their basic survival needs are met, individuals seek emotional connection, social belonging, and recognition from others. Daily activities corresponding to the elderly include walking, chatting, and neighborhood interactions, which satisfy their needs for social interaction, emotional support, and a sense of group belonging. Finally, people’s need to grow beyond themselves, that is, the need for self-actualized values, is the highest level of need, pointing to the fulfillment of personal potential, the quest for a sense of meaning, and the realization of self-worth. For older people, this may be manifested in learning new things, engaging in creative activities, assuming specific social roles, or making sustained contributions to the family and community. Based on the above theoretical mapping and the analysis of the daily behavioral activities of the elderly in Jiashan Village, this study distills three progressive levels of their needs for aging adaptation: the need for native services, the need for social interaction, and the need for personal value (

Figure 16). These three levels follow the order of satisfaction from low to high, which provides a solid theoretical foundation and value orientation for the subsequent identification of the differentiated needs of different elderly groups and the clarification of the priority direction of spatial aging adaptation.

Comparing the different types of elderly people in Jiashan Village (

Figure 17), we can learn that the daily activities of the leisure-oriented elderly people and agricultural-labor-oriented elderly people mostly include the needs for native services and social interaction; the daily activities of the caregiving-oriented elderly people include the needs for native services, social interaction, and personal values; and the daily activities of the self-employed-oriented elderly people lack social interaction needs, and the system of needs is not complete and continuous.

According to Maslow’s theory of needs, the more needs that are satisfied from low to high, the higher and more positive the emotions of the elderly should be. According to the emotional analysis (

Figure 10), the ranking of the time of emotional surge for different types of elderly people is as follows: caregiving-oriented type > leisure-oriented type > agricultural-labor-oriented type > self-employment-oriented type. It can be concluded that high-level needs have a greater positive emotional impact than low-level needs, such as social interaction needs having a greater emotional impact than native service needs. At the same time, the lack of certain needs in the daily life of the elderly can lead to a discontinuous demand system, which can also affect their emotions. For example, self-employed elderly people lack social interaction needs, and their emotions tend to be calm and low.

Through the hierarchy of needs analysis and satisfaction analysis, opinions guiding the practical application of age-friendly retrofitting were obtained, and the positioning of the age-friendly adaptation place for the elderly in Jiashan Village was finally determined (

Figure 18).

5. Discussion

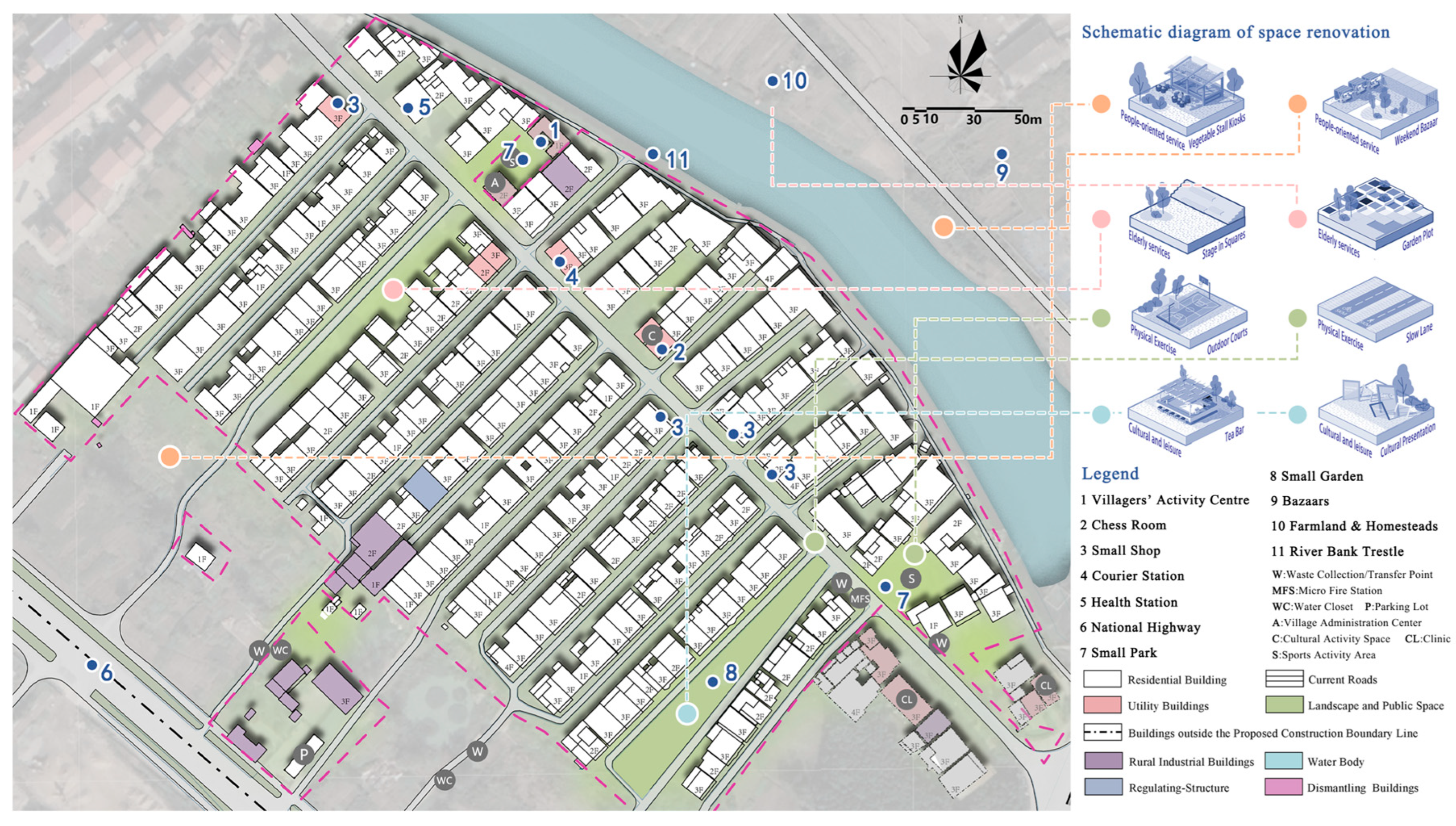

Based on the positioning of the renovation site, combined with the needs of the elderly, the method of spatial renovation as well as the system of creating a rural age-friendly community are proposed.

5.1. Combination of Multiple Methods to Prioritize Public Space Improvements

Based on five aspects—main activity space use demand, use experience, aging score satisfaction results, and SP-MNL model utility values—the transformation priority of the space is clarified, and the initial transformation direction is proposed in combination with the basic principles of space transformation (

Figure 19) and the actual situation of Jiashan Village.

The “high demand–poor use experience–mediocre satisfaction” category of space needs to be prioritized for renovation, including farmland/homesteads and roads/bridges, which share the common characteristics of long use time, decreasing satisfaction with increasing use time, and mediocre overall satisfaction ratings. The spatial demand of the elderly for farmland is high, but satisfaction is strongly negatively correlated with length of use, especially the lowest satisfaction ratings of the agricultural-labor-oriented-type elderly, who have the strongest spatial demand for farmland. The SP model shows that the utility value of fine-tuning is the highest, so it is necessary to renovate the farmland first, and then it is possible to consider focusing on the improvement of the safety of the waterfront steps and the convenience of the irrigation facilities. As a space for the elderly to pass through and relax in daily life, the roads/bridges have potholes on the surface, and satisfaction is negatively correlated with length of use, so it is recommended to widen the road surface and add lighting and resting points.

The next area that needs to be optimized is the space of “general needs–poor experience–low satisfaction”, such as community parks. As the core needs of socialization for the leisure-oriented and caregiving-oriented elderly, the quality of the existing park facilities is average. Combined with the intention of the elderly in Jiashan Village to renovate the park, we can consider updating and adding to the existing facilities. It should be noted that, although park renovation is necessary, SP shows that its utility value is lower than that of the farmland, and the latter should be prioritized in terms of allocating potentially limited resources.

Activity spaces with “general needs–good utilization experience–low satisfaction” can be selectively renovated in light of the actual development of the village, such as the chess room. This type of space focuses on interaction with others, has low spatial requirements, and the satisfaction level is greatly affected by the socialization of different elderly people, so increasing the openness and inclusiveness of the space should be considered during the renovation.

For the villagers’ activity center, which has general demand, good experience, and relatively high satisfaction, the current status quo should be retained, and the supporting facilities should be improved moderately.

In addition, the economic feasibility of different retrofitting measures should be considered. Rural areas often face limited resources, making cost a key constraint. A preliminary cost-effectiveness analysis indicates that high-input measures such as new plaza construction may encounter financial barriers, whereas low-cost options such as transforming idle homesteads into public spaces could achieve higher benefit–cost ratios. Coupling transformation strategies with villagers’ willingness-to-pay surveys will further enhance the practicality and prioritization of interventions.

Special scenarios such as extreme weather and sudden health incidents should not be overlooked. For example, elderly residents face higher risks when traveling during storms, and the lack of emergency shelter space exacerbates safety concerns. Future transformation strategies should therefore incorporate scenario simulations and design elements such as rain shelters, shaded resting points, and emergency passages, enhancing the safety and resilience of suburban rural public spaces.

5.2. Spatial Adaptation Priorities for Seniors with Differentiated Lifestyles

Based on the needs hierarchy analysis of the elderly in Jiashan Village corresponding to Maslow’s needs theory, targeted strategies are proposed in combination with the behavioral characteristics of elderly individuals with different lifestyles.

For leisure-oriented seniors, the strategies aim to satisfy their needs for social interaction and personal value realization by adding a small plaza stage and outdoor seating areas to facilitate leisure and social activities, alongside introducing community vegetable plots to combine light horticultural work with emotional fulfillment.

For the caregiving-oriented elderly, whose existing needs are largely met, the emphasis lies in enhancing intergenerational interaction and children’s safety; this is achieved by embedding child-friendly play areas within existing plazas, installing guardrails along the riverfront walkway, and designing shared activity zones to encourage interaction between grandparents and grandchildren.

In the case of agricultural-labor-oriented seniors, the spatial improvements focus on ensuring safe agricultural production while promoting informal social contact through upgrading the farmland facilities, such as irrigation and waterfront access, complemented by the provision of resting areas with stone benches near farmland to support both productive work and casual social exchange.

For self-employment-oriented seniors, the core needs for convenient services and opportunities for incidental socialization are addressed by deploying small kiosks along frequently used commercial and residential paths, thereby meeting daily service demands while creating opportunities for “bypass socialization”.

By analyzing the needs of the elderly and the current situation of Jiashan Village, a specific schematic diagram of the spatial renovation (

Figure 20) was created to meet the diversified needs of the elderly and provide quality living services. They also reflect the hierarchy of needs framework: farmland renovation addresses basic survival and safety needs, plazas and courts fulfill social belonging, while community pavilions and horticultural gardens provide opportunities for self-actualization and value expression.

Moreover, intra-group heterogeneity deserves further exploration. For instance, the observed “lack of social needs” among self-employment-oriented seniors may stem from work intensity, time constraints, or accessibility barriers, while agricultural-labor-oriented seniors may exhibit differentiated farmland facility demands depending on their age and health status. To deepen this understanding, future studies can supplement in-depth interviews and construct a “behavior–demand–space” correlation matrix, thereby providing a more detailed evidence base for precise adaptation strategies.

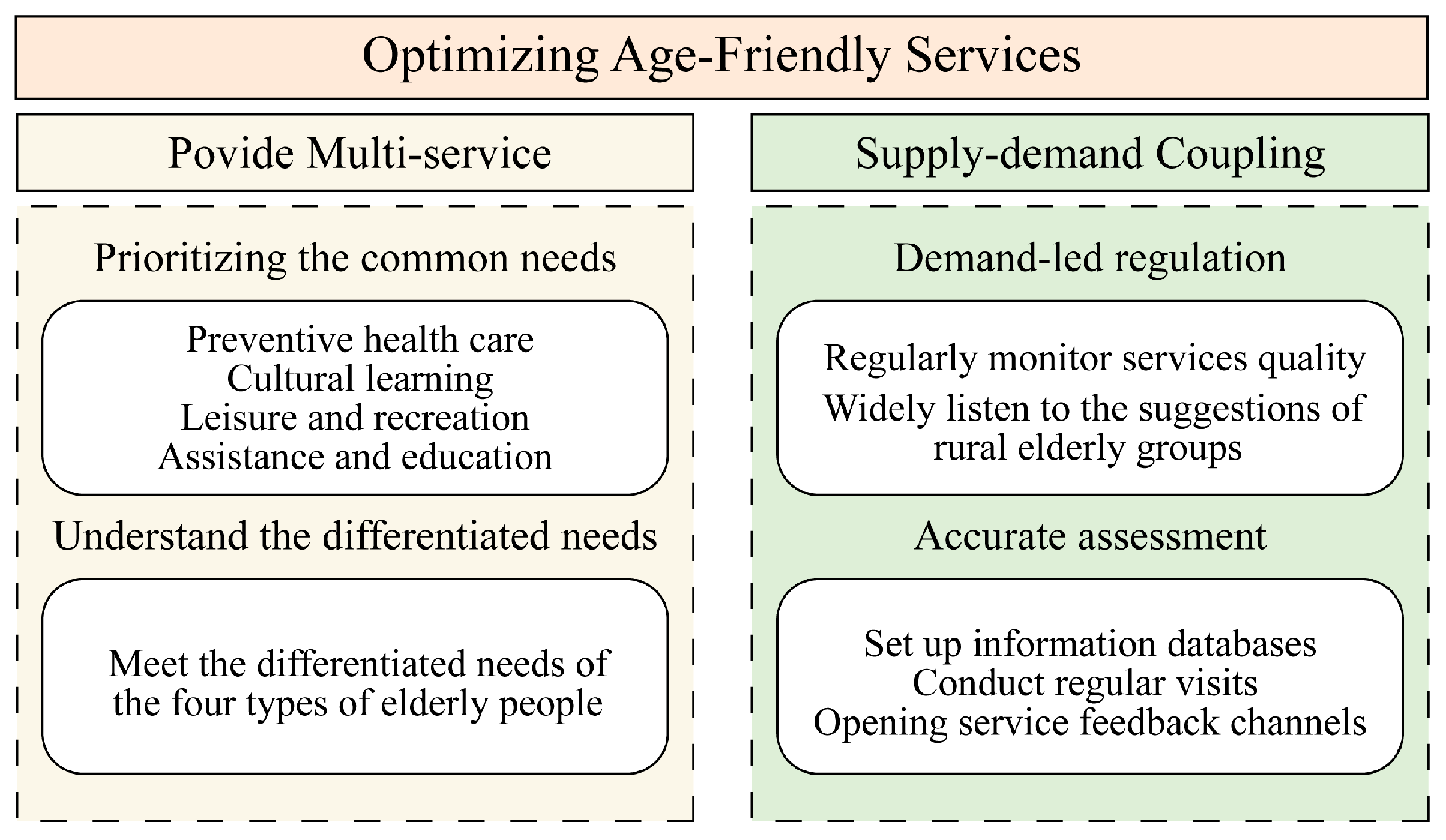

5.3. Optimizing Age-Friendly Services: Embedding Support Within the Spatial Framework

In order to comprehensively respond to the multifaceted and complex needs of different elderly groups while improving spatial carriers, it is necessary to embed age-friendly services into the daily life scenarios of the elderly through institutional design and multi-party collaboration (

Figure 21).

Firstly, a demand-oriented approach should be adopted to promote the coupling of supply and demand, providing diversified and high-quality age-friendly services. In response to the physical and mental characteristics and practical needs of rural elderly groups, priority should be given to addressing common high-frequency service demands, with a focus on strengthening the supply of urgently needed services, such as preventive healthcare, cultural education, leisure and recreation, and intergenerational educational support.

At the same time, it is essential to fully accommodate the differentiated needs of various elderly groups in terms of physical capacity, time availability, and social participation so as to achieve precise matching between service provision and individual characteristics. For example, for time-constrained self-employment-oriented and agricultural-labor-oriented elderly individuals, flexible and convenient services such as in-home health monitoring, mobile maintenance, and delivery of daily necessities should be developed. For leisure-oriented and caregiving-oriented elderly individuals, a variety of social and recreational activities, lifelong learning resources, and temporary childcare support should be provided, thereby comprehensively enhancing the targeting and coverage of services.

On this basis, a dynamic management mechanism should be established to regulate supply based on demand and drive optimization through evaluation and feedback. Village committees can take the lead in creating an elderly population information database, combined with regular household visits, to grasp and predict the potential needs of the elderly in real time. Meanwhile, it is necessary to establish sound service feedback channels, extensively collect evaluations from the elderly on service content and quality, closely monitor changes in their physical and mental states, and build a closed-loop management system of “demand identification–service provision–feedback optimization” to continuously improve service responsiveness and satisfaction among the elderly population.

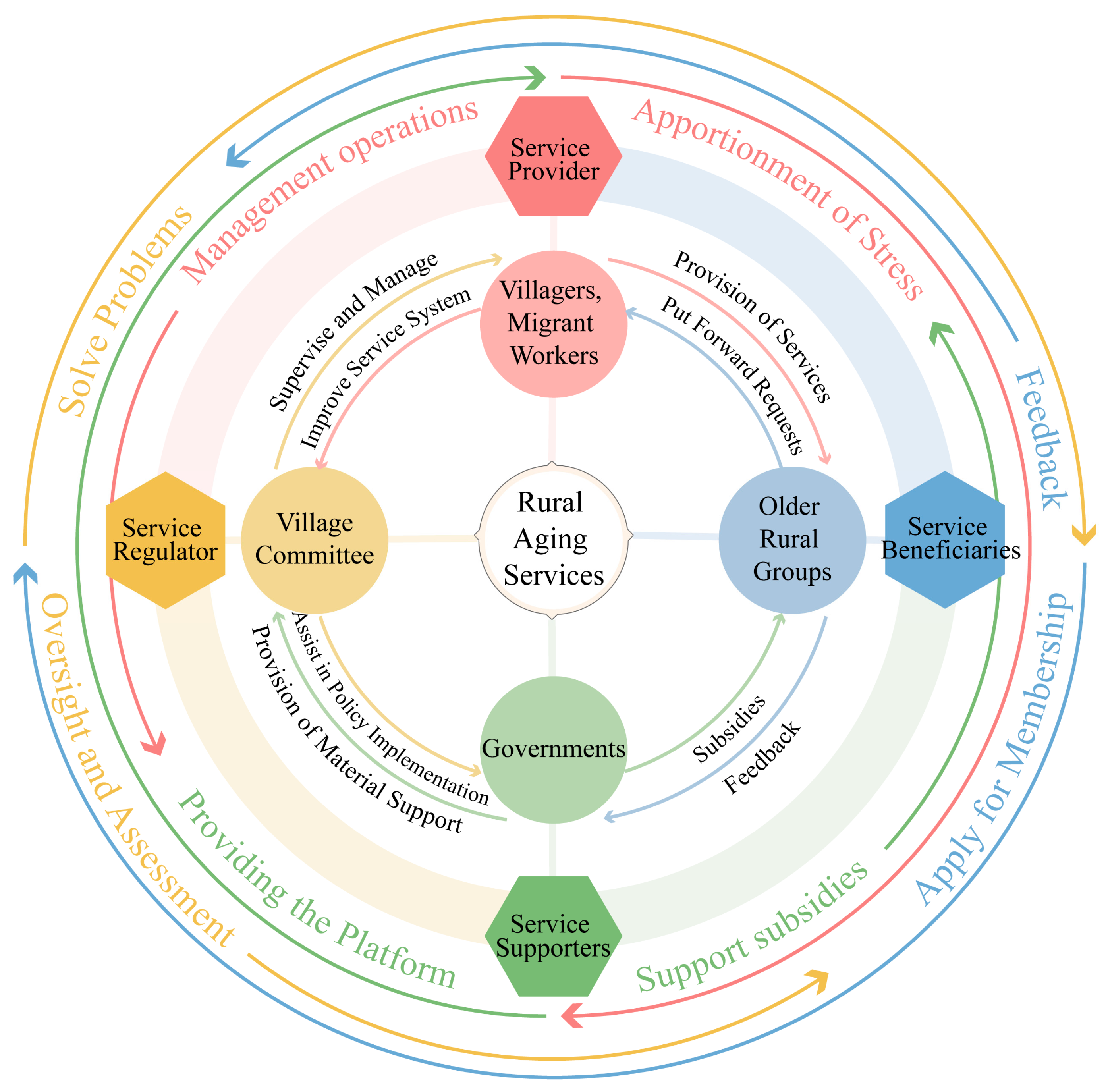

Secondly, establishing a multi-agent collaborative governance mechanism is essential for implementing age-friendly services in rural areas. As illustrated in

Figure 22, this mechanism integrates four core stakeholders: government agencies (service supporters), village committees (service regulators), villagers and migrant workers (service providers), and older rural residents (service beneficiaries). By aligning the interests and responsibilities of these diverse actors, the framework aims to transcend fragmented supply-driven approaches and foster a coordinated sustainable system for aging services.

Government agencies provide financial subsidies, policy guidance, and infrastructure investments while overseeing implementation, allocating resources, and facilitating the scaling of effective practices. Village committees serve as regulatory and coordinating bodies, responsible for assessing service demands, applying for policy support, and mediating divergent interests among older adults with varying needs—such as tensions between healthcare and recreational services. Villagers and migrant workers act as direct service providers, offering daily assistance, volunteer support, or semi-professional care. Their involvement not only addresses service shortages but also strengthens community cohesion. Older rural groups, as end-users, articulate needs and evaluate services, ensuring that adaptation strategies align with their lived realities rather than top-down decisions.

This collaborative model clarifies the nexus of actors, responsibilities, and resources, offering a replicable pathway for multi-stakeholder cooperation. It underscores that effective rural aging services rely not only on government support but also on co-production through structured collaboration, interest negotiation, and iterative learning—achieving a synergistic “win–win” scenario that enhances both service efficacy and community agency.

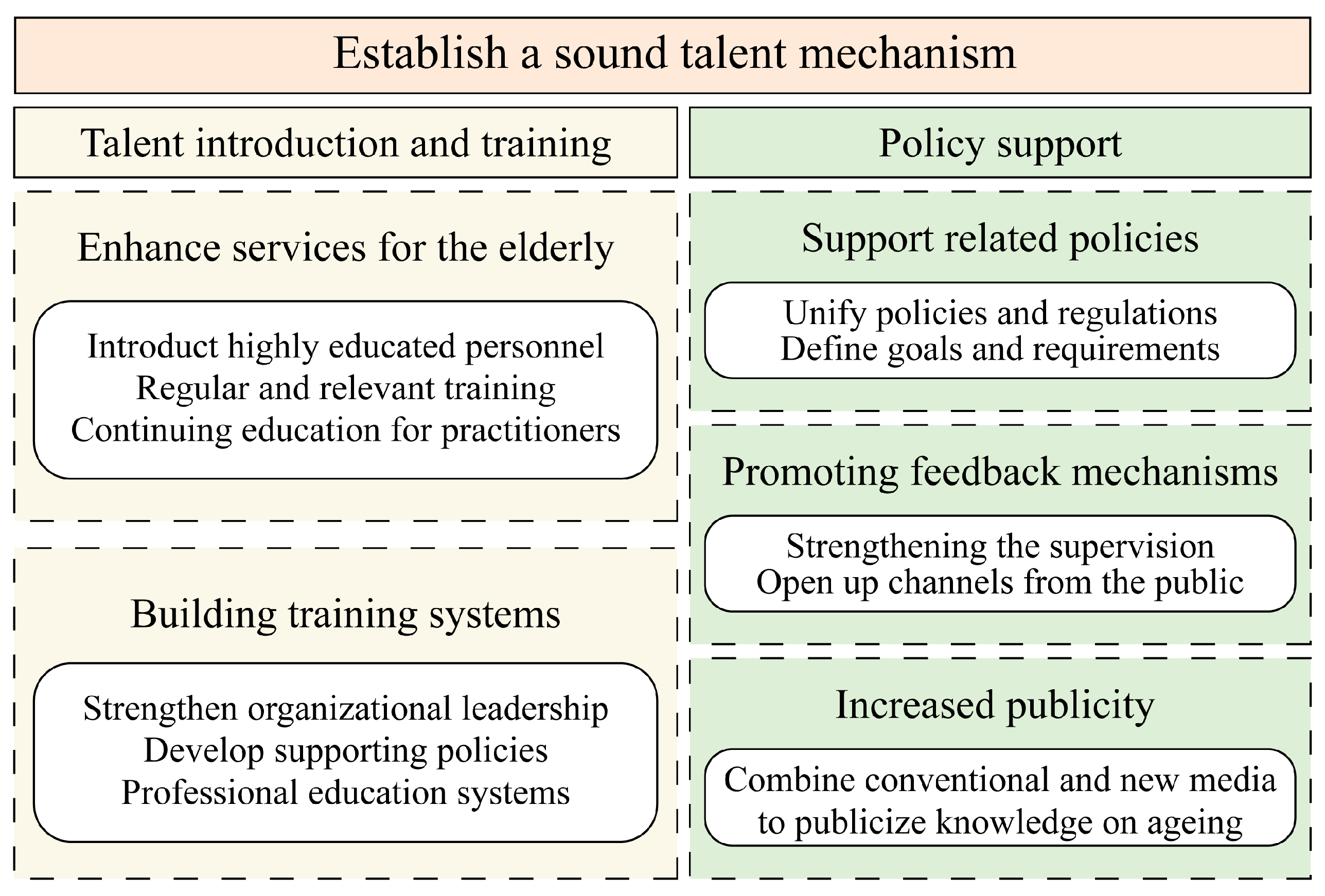

Finally, it is essential to strengthen talent introduction and training to improve the management system for elderly care services (

Figure 23). In light of rural realities, efforts should focus on introducing professional elderly care talent, enhancing grassroots service capabilities, and ensuring service sustainability through institutional guarantees. Specifically, it is necessary to actively recruit elderly care professionals with relevant expertise, develop a systematic training system, promote continuing education and regular on-the-job training for practitioners, and improve the quality of frontline services. At the same time, government guidance and support should be strengthened by formulating specific policies and regulations, establishing supervision and assessment mechanisms, and increasing publicity efforts around age-friendly concepts and policies. This will ensure the standardized operation and resource integration of the elderly care service system at an institutional level.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzes the spatial–temporal characteristics and influencing factors of the daily activities of older adults in the village of Jiashan through the new time–geography model. By extending the categorization of needs to the composite dimensions of behavioral patterns and affective experiences, it provides a theoretical tool for understanding and guiding age-friendly adaptation in a specific geographic unit of a suburban village. The integration of Maslow’s hierarchy with the new time–geography advances a three-tiered framework that links behavioral dynamics to spatial satisfaction, providing a nuanced perspective for precise age-friendly adaptation.

The study successfully identified four distinct lifestyles of older adults in Jiashan Village, each of which differed significantly in terms of spatial activity needs, social intensity, and emotional characteristics. This empirically validates the theoretical proposition that demographic attributes alone are insufficient to understand the complexity of rural older adults’ needs. The strong correlation between frequency of facility use and increased satisfaction, particularly through interventions such as farmland improvements and new plazas, is consistent with a core tenet of Maslow’s theory that meeting basic physiological and safety needs is a prerequisite for higher-level social and esteem needs. The proposed collaborative, multi-level, multi-objective retrofitting strategy directly addresses the identified mismatch between the top-down supply model and the comprehensive needs of rural older adults, moving in the direction of more responsive needs. The findings support the utility of the new time–geography model in capturing the dynamic spatial–temporal constraints and organizational interactions within rural older adults’ “daily life circles,” revealing how activity richness and social companionship are key drivers of spatial satisfaction and emotional well-being.

Compared with existing domestic and international studies, this research further highlights the differentiated age-friendly needs of suburban rural areas. Unlike the WHO’s “age-friendly community” standards, which are primarily city-oriented, suburban villages also rely on production spaces such as farmland, reflecting a distinctive dependence not fully addressed in urban frameworks. Similarly, domestic urban transformation experiences emphasize service accessibility and public facilities but less so agricultural production and intergenerational caregiving, which are prevalent in rural contexts. Therefore, this study supplements and revises existing theories by emphasizing the coexistence of production–living–social spaces in suburban villages, demonstrating its theoretical contribution to the broader discourse on age-friendly environments.

While this study provides valuable insights, there are several limitations that warrant careful consideration when interpreting the results and planning future applications.

First, in terms of sample scope and representativeness, this study focuses on Jiashan Village in Wuhan, a suburban village with relatively favorable economic conditions and development prospects as a future urban sprawl area. Although these findings were selected for their typicality in terms of their peri-urban characteristics and lifestyle diversity, they may not be fully generalizable to suburban villages in areas with significantly different economic structures, cultural backgrounds, or levels of urbanization. The sample size (30 GPS follow-ups and 152 valid SP questionnaires) was sufficient for case study exploration but limits robust statistical generalization to a wider population. Therefore, the specific lifestyle categorizations, prioritization of spatial needs, and utility values derived from the SP-MNL model should be interpreted as specific to the context of Jiashan Village or similar economically advantaged suburban environments. Direct application of these findings to remote or impoverished villages requires caution and adaptation. Furthermore, to clarify the applicable boundaries of the conclusions, future research should adopt a stratified sampling approach to include suburban villages with different economic levels and degrees of urbanization. Comparative analyses with remote or underdeveloped suburban villages can further test the universality of the lifestyle typologies identified in this study. In addition, expanding the sample size—especially by including special elderly groups such as those living alone and the advanced aged—would enhance statistical robustness and avoid potential representativeness bias.

Second, recognition performance may vary across demographics, especially among elderly individuals, due to facial morphology, wrinkles, and the generally reserved nature of emotional expression in this group. To enhance applicability in the rural elderly context, several measures were incorporated into the experimental design. First, all the data collection was conducted under evenly distributed indoor lighting, with the participants positioned frontally, minimizing occlusion and ensuring stable recording quality. Second, a pilot test involving 10 elderly participants from the study community was carried out to verify recognition stability under real conditions and to adjust camera distance, lighting, and task pacing. Third, stimulus tasks were designed to allow sufficient time for expression considering the slower dynamics of elderly facial responses, and short breaks were introduced to maintain attention. Fourth, the emotion recognition outcomes were cross-validated with participants’ self-reported evaluations from questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, which helped to reduce potential bias associated with cultural differences in emotional expression. Finally, data quality indicators provided by the software were used to filter out recordings affected by poor responsiveness or environmental interference, such as glare and shadow. Through this combination of optimized recording conditions, pre-experimental validation, task design, cross-verification, and strict quality control, the study ensured that the facial expression recognition results reliably reflected the emotional states of rural elderly participants while minimizing potential biases introduced by cultural and demographic factors.

Finally, this study provides cross-sectional analyses, but the long-term effectiveness of the proposed renovation strategies remains to be validated. Future research will benefit from a tracking design with 6-month and 1-year follow-up evaluations, covering indicators such as space usage rate, satisfaction change, and emotional state fluctuation. Such longitudinal tracking will enable assessing the sustainability of the transformation measures. In parallel, a demographic simulation should be incorporated to forecast future spatial demand and enhance the forward-looking value of strategy formulation.

Recognizing the limitations, future research should focus on expanding the study to suburban villages at different economic levels and geographic regions to validate and refine the lifestyle typology and needs framework, identifying universal principles and context-specific adaptations. Additionally, methodological refinements should focus on exploring complementary or alternative methods to enhance emotion measurement and behavioral tracking and investigate the cultural specificity of emotional expression in rural elderly populations. By recognizing these limitations and pursuing these future directions, the field can move towards more robust, adaptive, and sustainable strategies for creating truly age-friendly environments in the diverse and evolving landscapes of rural and peri-urban areas in developing countries.