The Mutual Verification of Agricultural Imagery and Granary Architecture in Ancient China: A Case Study of the Fuzhou “Room-Style” Granaries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Lack of analysis on the form and structural patterns of local granary buildings: Granaries have received less attention in the literature compared to other types of buildings, a phenomenon that is not difficult to understand. Compared to residential, religious, public affairs management, and entertainment venues, granaries occupy a secondary position in terms of function [11]. However, with the increasing convergence of urbanization, rural areas, as places where people reconnect with inland regions and cultural roots, have attracted growing attention. Granaries, as agricultural buildings, are increasingly being recognized as objects for preservation due to their intrinsic value [12]. People have come to realize that granary buildings were not only important facilities for ancient ancestors to store materials but also an essential part of individual households and even the social life of entire nations. Existing studies on storage architecture have primarily focused on aspects such as architectural history, construction techniques, categories of stored goods, and management systems, with a particular emphasis on large-scale official granary buildings [13]. Research on local granary heritage, however, remains scarce. As a single-function building type, traditional granary buildings in Fuzhou City have undergone slow iterations, retaining ancient cultural genes that merit further investigation. In China, certain traditional granary buildings have been officially recognized within the national heritage protection system. According to the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics, some granaries are designated as “The National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units or Provincial Key Cultural Relics Protection Units”. Representative examples include the Nanxincang of Beijing and Fengtu Charity Granary of Shanxi [14,15], both of which are acknowledged for their historical significance and architectural value. These categorizations highlight that traditional granary buildings are not only functional structures but also integral components of China’s cultural heritage, deserving of further scholarly attention. At present, there remains a gap in the indigenous construction knowledge system of traditional granaries.

- Insufficient cross-verification between documentary records and physical remains: Traditional granaries, with their unique grain storage methods and distinctive architectural features, integrate local climatic conditions, geographical environments, and cultural traditions. They provide invaluable physical evidence for a deeper understanding of vernacular grain storage practices. As witnesses to the development of agrarian civilization, they embody the material and spiritual life, as well as the level of social development, in the Fuzhou City, while demonstrating building techniques and storage wisdom. Despite their wide distribution and large numbers, such granaries have long been overlooked. Building on prior studies of related topics, a systematic cross-verification of documentary sources and physical remains, aimed at uncovering the indigenous construction knowledge embedded in the surviving traditional granaries of eastern Jiangxi, remains to be further explored.

- Inadequate research on the construction wisdom of storage architecture: The construction system of traditional granaries represents a comprehensive decision-making framework [16]. Based on extensive experience in disaster relief, ancient builders developed highly sophisticated storage systems and architectural wisdom adapted to local needs. Granary is one of the architectural forms emerging early in human history [17]. Globally, granary buildings have always been a symbol of agricultural wisdom. For example, stone granaries in the Iberian Peninsula prevent rodent invasion and ground moisture by raising their foundations; North American barns serve multiple functions such as livestock housing, feed and grain storage, and are often located near main roads; traditional Japanese granaries use a beam-column structural system with clay plaster on the exterior for fireproofing; traditional granaries in Iran adopt elevated foundations and semi-open designs to promote drying and moisture protection of the grain [18]. Unlike the above examples, the traditional granary in Fuzhou is a composite building formed by combining “courtyard-type residences and raised-platform structure,” This unique combination not only creates a distinct type of storage architecture but also embodies rich construction wisdom. Therefore, further exploration and research on the construction wisdom of traditional granaries is urgently needed.

1.1. Historical Development of the Storage System

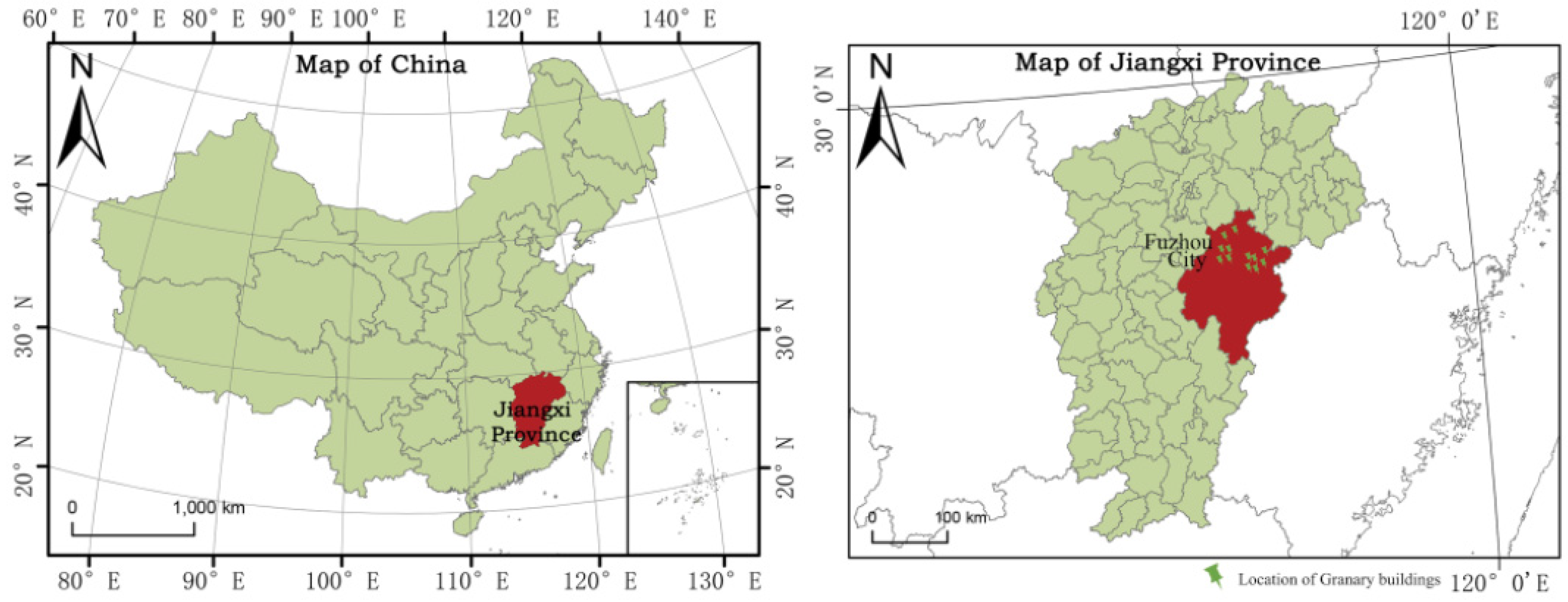

1.2. Overview of Traditional Granary Buildings in Fuzhou City, Jiangxi Province

1.3. Overview of Ancient Chinese Agricultural Imagery

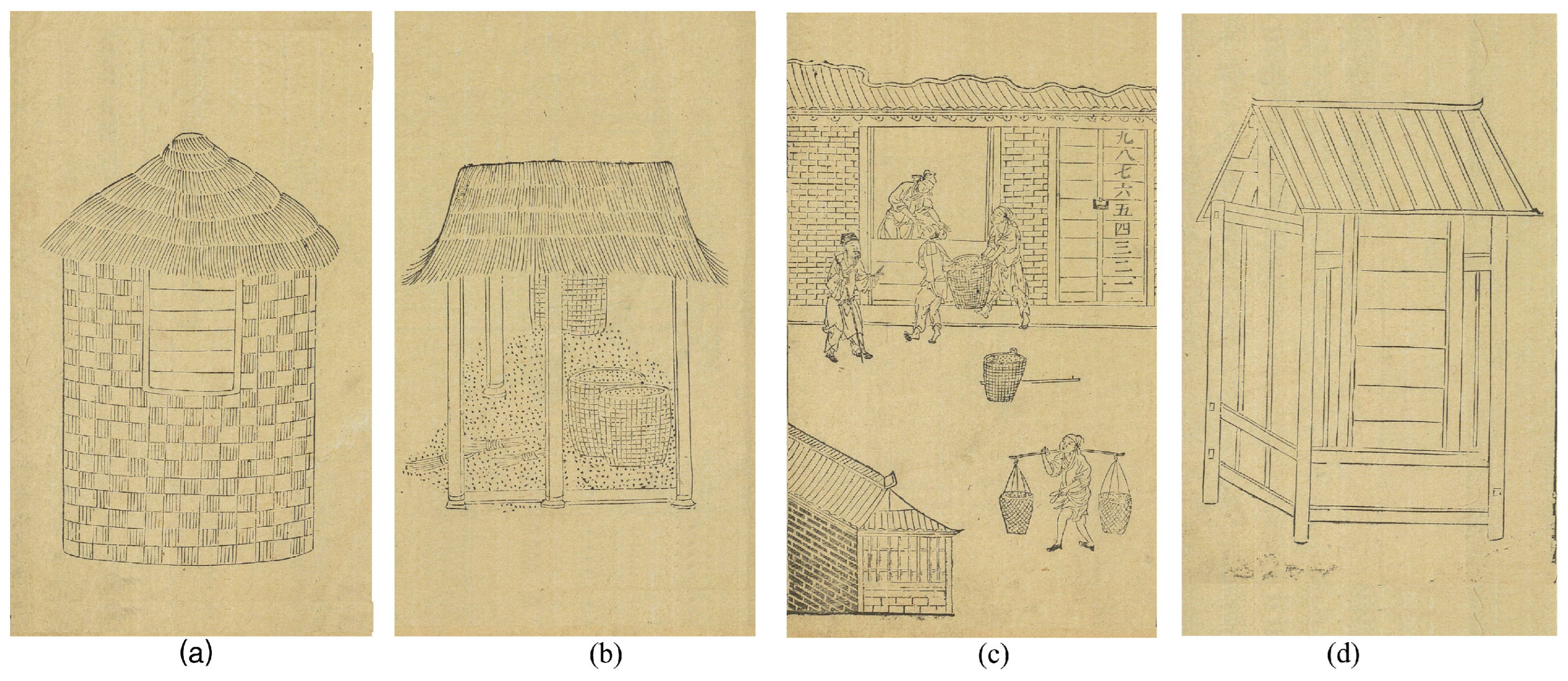

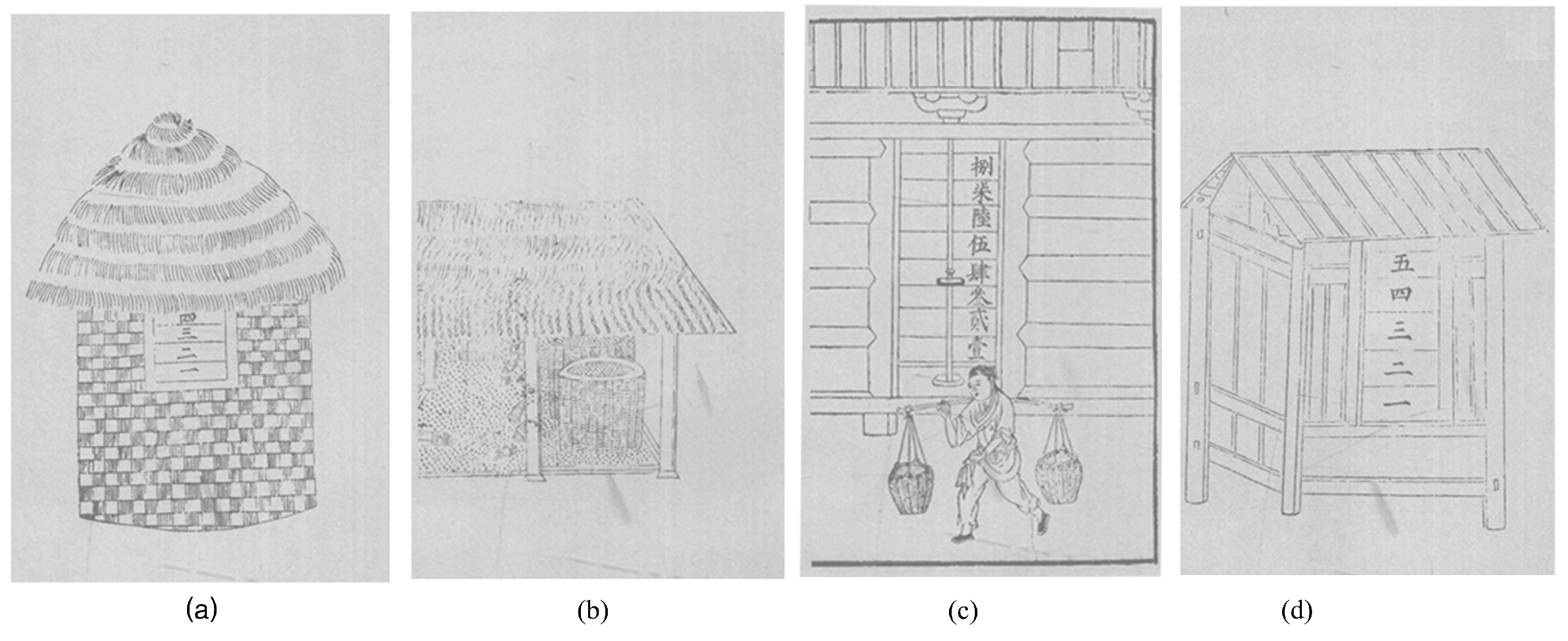

- Systematic Geng zhi Tu (耕织图,Pictures of Tilling and Weaving)

- 2.

- Agricultural Treatises

- 3.

- Pictorial Bricks and Tomb Mural Agricultural Imagery

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

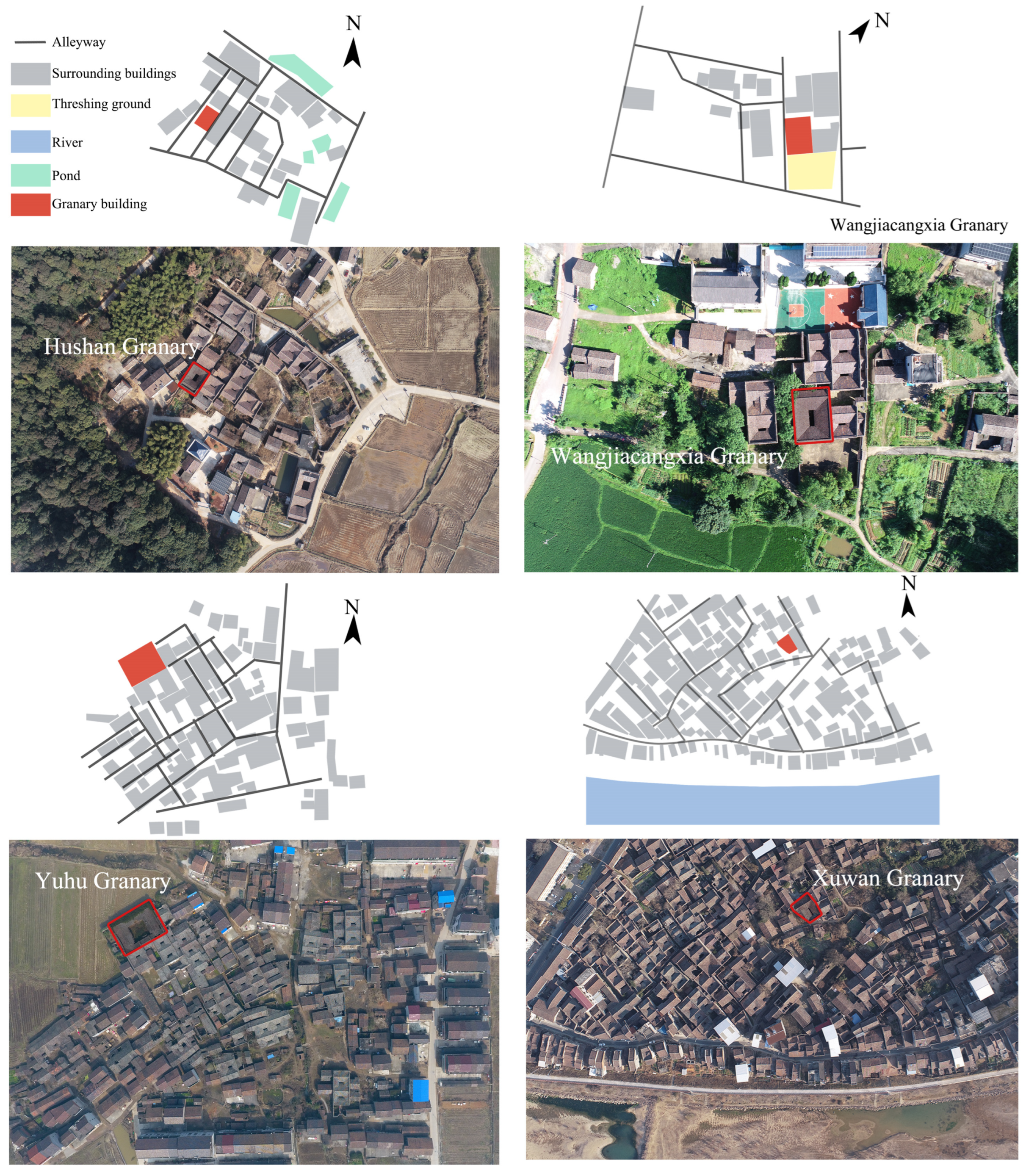

2.2. Field Surveys

2.3. Digital Modeling

2.4. Case Study Analysis

2.4.1. Compositional-Dimension Analysis

2.4.2. Image–Artifact Corroboration

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Granaries

3.1.1. External Space

3.1.2. External Form

3.1.3. Interface Composition

3.1.4. Internal Space

3.1.5. Semi-External Space

3.1.6. Structural System

- Chuandou-style (穿斗) primary frameworkThe primary structure of the granary is a chuandou-frame timber system, with brick walls serving as the exterior enclosure. A few granaries converted from ancestral halls adopt a tailiang (抬梁, a traditional Chinese beam-lift construction) structure, but the chuandou frame remains the predominant form (Figure 11).

- Raised-Platform Structure storage roomsThe raised-platform structure is an ancient architectural form in which the building is elevated on stilts, creating an open space between the structure and the ground to enhance ventilation [41]. In addition, the open bottom space provides a free passage for cats, which helps prevent rodent infestations. In Fuzhou’s traditional granaries, this form is innovatively adapted by incorporating a dual moisture-proof system consisting of sandstone sleeper walls (500 mm high × 100 mm thick) and timber sleeper beams, effectively blocking ground moisture (Figure 10). The earthen rampart walls of granaries are typically made from red sandstone unique to the Danxia landform in Jiangxi. Red sandstone is hard in texture and highly resistant to weathering, making it suitable for use in humid environments. This material is also commonly used in more decorative architectural elements, such as window frames and stone carvings, reflecting the local cultural characteristics and the esthetic style of the architecture.

3.2. Identifying Structures Through Imagery: Correlations Between Agricultural Depictions and Surviving Physical Remains

3.2.1. Comparison of Functions of Granary Buildings

3.2.2. Comparison of Granary Building Structures

3.3. Identifying Structures Through Imagery: Detail Recognition and Physical Reconstruction of Agricultural Granaries

3.3.1. Roof Ventilation Windows and Ventilated Loft Spaces

3.3.2. Numbered Slotted-Board Doors and Bolt-Locked Slotted-Board Doors

3.3.3. Wooden Plank Walls and Bamboo-Lath and Clay Partitions

4. Discussion

- To elucidate the role and significance of room-style granary buildings in eastern Jiangxi within ancient agricultural production, thereby providing empirical support for understanding ancient grain storage systems;

- To reveal, through cross-verification of agricultural imagery and surviving physical remains, the authentic aspects and cultural connotations of ancient agrarian life.

4.1. Testimony of Zhu Xi’s She-Cang Method

4.2. Reflection of the “Neo-Confucian” Beliefs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.H. Farming Civilization and Chinese Rural Society; Shandong University Press: Shandong, China, 2023; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Hou, R.; Yu, J.; Niu, S.; Chen, X.; Han, B.; Zhang, P. Historical vicissitudes of grain storage environment of granaries in the North China Plain. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.L.; Wang, S.M.; Zhuang, G.P. Types, Values, and Protection of Agricultural Tools Cultural Heritage in Jiangnan Rice Agriculture—A Discussion on the Rice Farming Tools in the South Song Dynasty Copy of “Geng Zhi Tu”. China Agric. Hist. 2015, 3, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.X. A Re-Study of Grain Granary Images in the Dajie Han Tomb. Huaxia Archaeol. 2023, 5, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.X. Ancient Chinese Grain Storage Facilities and Techniques; Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1987; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.Z. Two Notes on the Raised Granaries. Archaeol. Cult Relics 2021, 5, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.H. A Brief Discussion on Agricultural Archaeology. Agric. Archaeol. 1984, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.G. A Study of Ancient Granary Names. Agric. Archaeol. 1985, 1, 344–345. [Google Scholar]

- Golas, P.J. Picturing Technology in China; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2015; Available online: https://hkupress.hku.hk (accessed on 12 January 2015).

- Endersby, E.; Greenwood, A.; Larkin, D.; Rocheleau, P. Barn Preservation & Adaptation: The Evolution of a Vernacular Icon; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes Balsas, C.J. From Granary to Arts Incubator: An Evolutionary Perspective on the Concept of Food for Thought. World 2024, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picuno, P. Farm buildings as drivers of the rural environment. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 693876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Deng, H.; Zhu, Z. Research on the sustainable design strategies of vernacular architecture in southwest Hubei—A case study of the First Granary of Xuan’en County. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0316518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, X.; Tang, M. Modes of Protection and Utilization for Urban Historical and Cultural Streets: A Case Study of Nanxincang Historical and Cultural Street in Beijing. Yunnan Univ. Natl. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 31, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, X. Study on the Architectural Design of Granaries in Guanzhong during the Qing Dynasty: A Case Study of Fengtuyi Granary. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 50, 872–877. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. From hinterland granary fort to frontier mountain fortress: Initiation, construction, and expansion of the Diaoyucheng Fortress, Hechuan, China, in the wars during 1125–1279. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.S. An Initial Exploration of Han Dynasty Granaries. Zhongyuan Cultural Relics 1986, 1, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vahdati, F.; Tedjosaputro, M. A Comparative Study: Vernacular Timber Construction Techniques of Iranian, Japanese, and Spanish Granary Structures. In Proceedings of the 57th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Gold Coast, Australia, 26–29 November 2024; pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.T. The History of Famine Relief in China; Dongfang Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.Z. A Review of Famine Relief Policies Since the 20th Century. China Hist. Res. Trend 2004, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.W. The Effectiveness of Qing Dynasty Grain Storage and State Capacity in Famine Relief. Jianghai J. Stud. 2021, 1, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.W. Clarifying the Concepts of Yi Granary and She Granary. Qing Hist. Rev. 2018, 2, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y. Essence of the Four Treasuries of the Imperial Library; Jilin University Press: Jilin, China, 2009; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.Q. Outline of the History of Ancient Chinese Grain Storage (Part II)—The First Important Development Period of Grain Storage in Qin and Han Dynasties. China Storage Transp. 1992, 1, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.D.; Qiao, Q. From “Resisting the Oppressive Taxes” to “Taking the Interest from Grain Loans”: The Evolution and Moral Dilemma of China’s Ancient Famine Relief Loan Interest Strategies. China Agric. Hist. 2021, 6, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.W.; Wen, X.H. A Study on Grain Storage in Jiangxi during the Ming Dynasty. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2015, 7, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, S.D. Zhuzi Community Granary and the Formation of Southern Song Villages. Yunnan Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, F.; Zheng, Y. Collection of Local Chronicles of China 50: Jiangxi County Chronicles, Photocopy Edition, Tongzhi Jinxian Chronicle; Phoenix Press: Beijing, China, 2013; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Du, Y.T.; Yang, Z.S. Xinjian County Chronicle, Construction Chronicle: Granary Storage, Tongzhi Edition. Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 1871; Volume 24, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K. Time and Space Distribution and Operation of Social Granaries in Qing Dynasty Jiangxi. Agric. Archaeol. 2016, 3, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. The Concept and Methodology of Ancient Chinese Agricultural Image Studies. China Agric. Hist. 2023, 42, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.Y.; Zhang, S.S. Rituals and Customs Interaction: Social and Cultural Integration in Jinan; Qilu Press: Shandong, China, 2019; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.Z. Imperial Manuscripts of Geng Zhi Tu, Kangkai’s 35th Year, Imperial Edition; Imperial Household Department: Beijing, China, 1696. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.B.; You, X.C. Selected Agricultural Scientific Literature in China, Vol. 1: Wang Zhen’s Agricultural Manual; Hunan Science and Technology Press: Changsha, China, 2014; p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, S.Y. San Cai Tu Hui (Original Edition, Ming Dynasty), “Palaces and Buildings”. 1609, Volume 2. Available online: https://old.shuge.org/ebook/san-cai-tu-hui/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 December 2015).

- Wang, Z. Wang Zhen’s Agricultural Manual; Ming Dynasty Woodblock Print Facsimile; Zhonghua Shuju: Beijing, China, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, K. Architectural Composition: Methods of Architectural Design; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2018; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.B.; Sakamoto, K.; Xie, W.J. Settlement, Rhetoric, Composition—Kazuaki Sakamoto Talks about Architectural Composition: The Method of Architectural Design. J. Archit. 2023, 6, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. Image and History; Yang, Y., Translator; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, F. History and Its Images: Art and the Interpretation of the Past; Kong, L., Translator; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.H. Symbols of Ancient Architecture; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2011; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Collected Works of Wei Yuan, Vol. 15: Imperial Government and Administration; Yuelu Press: Changsha, China, 2004; p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Huang, R.X. Fuzhou Financial Chronicle; Fuzhou Financial Chronicle Editing Committee: Fuzhou, China, 2002; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.; Lin, Z. Han Dynasty Agricultural Image Brick and Stone; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1996; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q. Research on Chinese Han Paintings; Guangxi Normal University Press: Guilin, China, 2004; Volume 1, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Golden Hibiscus Under the Black Soil “Eastern Han Elderly Image Brick Rubbing”; Bashu Publishing House: Chengdu, China, 2020; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, W.; Peng, H.; Jia, R.; Sun, Q. Assessment of Variation in Paddy Microbial Communities Under Different Storage Temperatures and Relative Humidity by Illumina Sequencing Analysis. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q. Gengzhi Tu. Lou, Shu. Gengzhi Tu Attributed to Cheng Qi (Yuan dynasty), Copy After Lou Shu. Handscroll, Ink and Color on Silk. Available online: https://www.shuge.org/view/geng_zhi_tu_juan/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Jiao, B. Z Imperial Farming and Weaving Illustrations, Figure 22 “Entering the Granary”; Imperial Press: Wayne, MI, USA, 1704. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, F. Bianmin Tuzhuan [Convenient Image Seal], 15 Volumes; Yongqing Edition; 1593; Available online: https://guji.atimebook.com/1316.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Chen, G.C.; Ying, Y.X.; Jin, X.G.; Sun, J. The History and Culture of Zhi Ying, a Famous Town in Central Zhejiang in the Southern Dynasties; Yanshan University Press: Beijing, China, 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- San, Y.F. Song Dynasty Grain Security Policies and Their Practices. J. Northwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 61, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.T.; Chen, Y.B. History of Anhui Literature, Vol. 1: Pre-Qin to Northern Song Dynasty; Anhui Literature Press: Anhui, China, 2013; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.P. On the Academic Demonstrative Significance and Its Influence of the “Ehu Meeting”. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2011, 31, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

| Types | Materials | Field Documentation Images |

|---|---|---|

| Roof | cylindrical clay tiles |  |

| Wall | exterior walls: Blue Brick |  |

| The side walls of storage rooms: bamboo-lath and clay partitions |  | |

| Front wall of storage room: cedar boards |  | |

| Floor | Courtyard floor: Bluestone |  |

| Storage room Floor: rammed earth floors |  |

| Types | Single-Row Layout Type | Double-Row Layout Type | U-Shaped Layout Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granary Buildings layout |  |  |  |

| Case Study | Width (mm) | Depth (mm) | Height (mm) | Area (m2) | Quantity | Total Grain Storage Capacity (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hushan Granary | 1600 | 2200 | 2100 | 3.52 | 4 | 29.6 |

| Hougong Granary | 1500 | 3400 | 2200 | 5.1 | 7 | 173.1 |

| 2100 | 4400 | 2200 | 9.24 | 4 | ||

| 1800 | 3400 | 2200 | 6.12 | 2 | ||

| Wangjiacangxia Granary | 1500 | 2400 | 2500 | 3.6 | 8 | 72 |

| Xiadongcao Granary | 1600 | 1700 | 2100 | 2.72 | 4 | 22.8 |

| He’s Granary | 1400 | 2000 | 2000 | 2.8 | 6 | 33.6 |

| Gefang Granary | 1300 | 2900 | 3000 | 3.77 | 4 | 81.1 |

| 1300 | 2300 | 3000 | 2.99 | 4 | ||

| Xingjuxuan Granary | 2700 | 3100 | 2200 | 8.37 | 6 | 110.5 |

| Hebu Granary | 1800 | 2000 | 2900 | 3.6 | 2 | 29.4 |

| 1400 | 2100 | 2900 | 2.94 | 1 | ||

| Yuhu Granary | 2900 | 4100 | 2300 | 11.89 | 10 | 469.6 |

| 3300 | 5100 | 2300 | 16.83 | 3 | ||

| 3300 | 4200 | 2300 | 13.86 | 1 | ||

| 4100 | 5100 | 2300 | 20.91 | 1 | ||

| Fengying Granary | 2600 | 2600 | 2200 | 6.67 | 3 | 63.5 |

| 1100 | 2600 | 2200 | 2.86 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, J. The Mutual Verification of Agricultural Imagery and Granary Architecture in Ancient China: A Case Study of the Fuzhou “Room-Style” Granaries. Buildings 2025, 15, 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183343

Yi Y, Du J, Xu J. The Mutual Verification of Agricultural Imagery and Granary Architecture in Ancient China: A Case Study of the Fuzhou “Room-Style” Granaries. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183343

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Yu, Juan Du, and Jianhe Xu. 2025. "The Mutual Verification of Agricultural Imagery and Granary Architecture in Ancient China: A Case Study of the Fuzhou “Room-Style” Granaries" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183343

APA StyleYi, Y., Du, J., & Xu, J. (2025). The Mutual Verification of Agricultural Imagery and Granary Architecture in Ancient China: A Case Study of the Fuzhou “Room-Style” Granaries. Buildings, 15(18), 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183343