Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Safety-specific transformational leadership (independent variable):

- 2.

- Safety behavior (dependent variable):

- 3.

- Knowledge sharing (mediating variable):

- 4.

- Psychological safety (moderating variable):

- Relationships:

- Contributions:

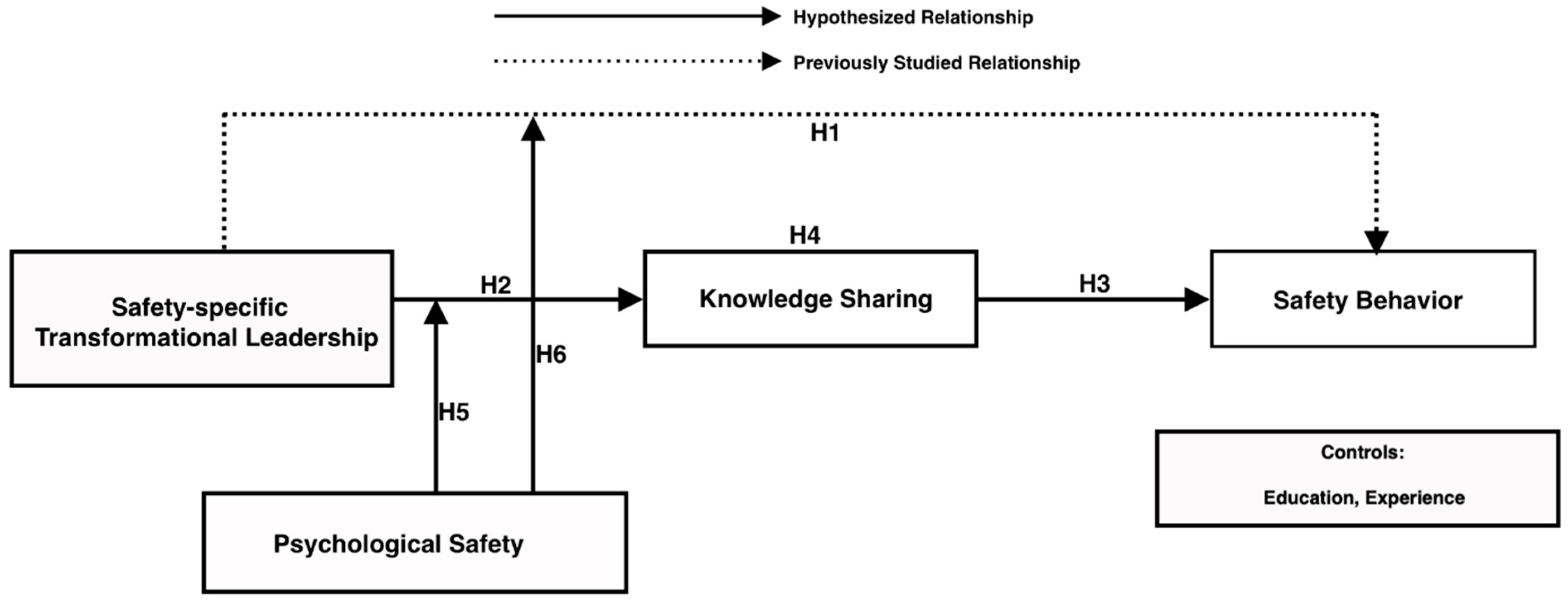

- This study uses four variables: safety-specific transformational leadership, safety behavior, knowledge sharing, and psychological safety. Among these variables, safety-specific transformational leadership is an independent variable, safety behavior is a dependent variable, knowledge sharing is a mediating variable, and psychological safety is a moderating variable.

- Social exchange theory and the positive organizational behavior framework are used to examine the impact of safety-specific transformational leadership (SSTL) on safety behavior.

- The primary objective of this study is to investigate how safety-specific transformational leadership impacts safety behavior among construction workers, specifically exploring the roles of knowledge sharing and psychological safety.

- The research seeks to understand how leaders can encourage a safety-conscious environment in construction by promoting knowledge sharing and psychological safety, which leads to better safety outcomes for workers.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

2.2. Positive Organizational Behavior (POB) Perspective

2.3. SSTL and Safety Behavior

2.4. SSTL and Knowledge Sharing

2.5. Knowledge Sharing and Safety Behavior

2.6. The Mediation Role of Knowledge Sharing

2.7. The Moderation Role of Psychological Safety

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

3.2. Survey Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

3.4. Non-Response Bias

3.5. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

4.2. Direct and Indirect Effect Results

| Relationships | Sample Estimate | Standard Error | t-Values | p-Values | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| M1: knowledge sharing | ||||||

| Intercept | 5.578 | 0.016 | 340.281 | 0.000 | 5.546 | 5.610 |

| SSTL | 0.440 | 0.023 | 19.369 | 0.396 | 0.485 | |

| PS | 0.466 | 0.020 | 23.852 | 0.000 | 0.428 | 0.505 |

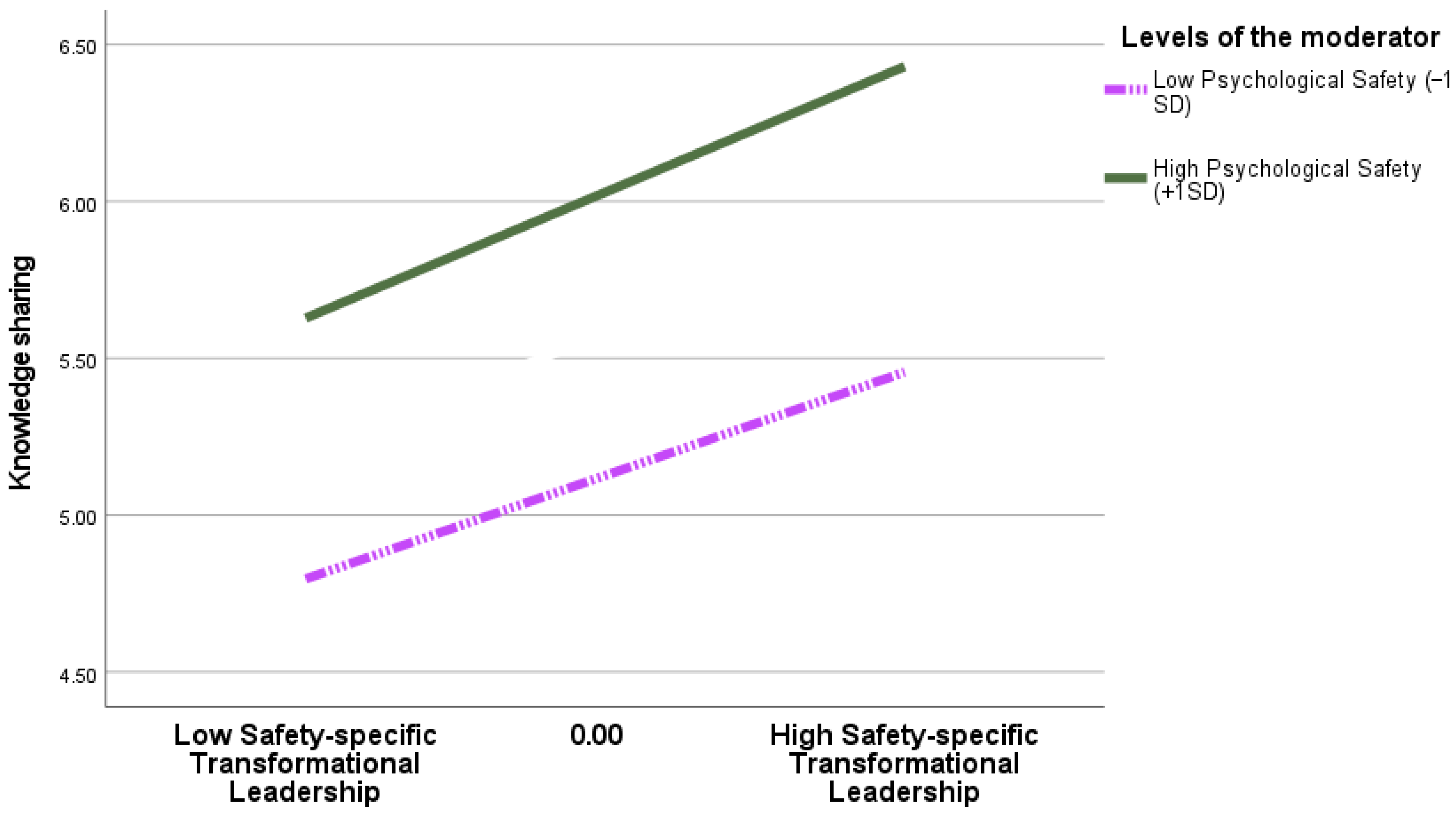

| SSTL × PS | 0.044 | 0.017 | 2.690 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.077 |

| Experience | 0.049 | 0.028 | 1.781 | 0.075 | −0.005 | 0.104 |

| Education | −0.015 | 0.014 | −1.045 | 0.295 | −0.042 | 0.0127 |

| The conditional direct effect of SSTL on KS at different levels of PS | ||||||

| −1SD (Low) | 0.397 | 0.025 | 15.655 | 0.000 | 0.347 | 0.447 |

| +1SD (High) | 0.483 | 0.030 | 16.107 | 0.000 | 0.424 | 0.542 |

| R2 = 0.625 *** | ||||||

| M2: Safety behavior | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.905 | 0.129 | 38.381 | 0.000 | 4.697 | 5.203 |

| SSTL | 0.303 | 0.024 | 12.509 | 0.000 | 0.255 | 0.350 |

| KS | 0.110 | 0.023 | 4.770 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.155 |

| PS | 0.487 | 0.022 | 22.418 | 0.000 | 0.444 | 0.530 |

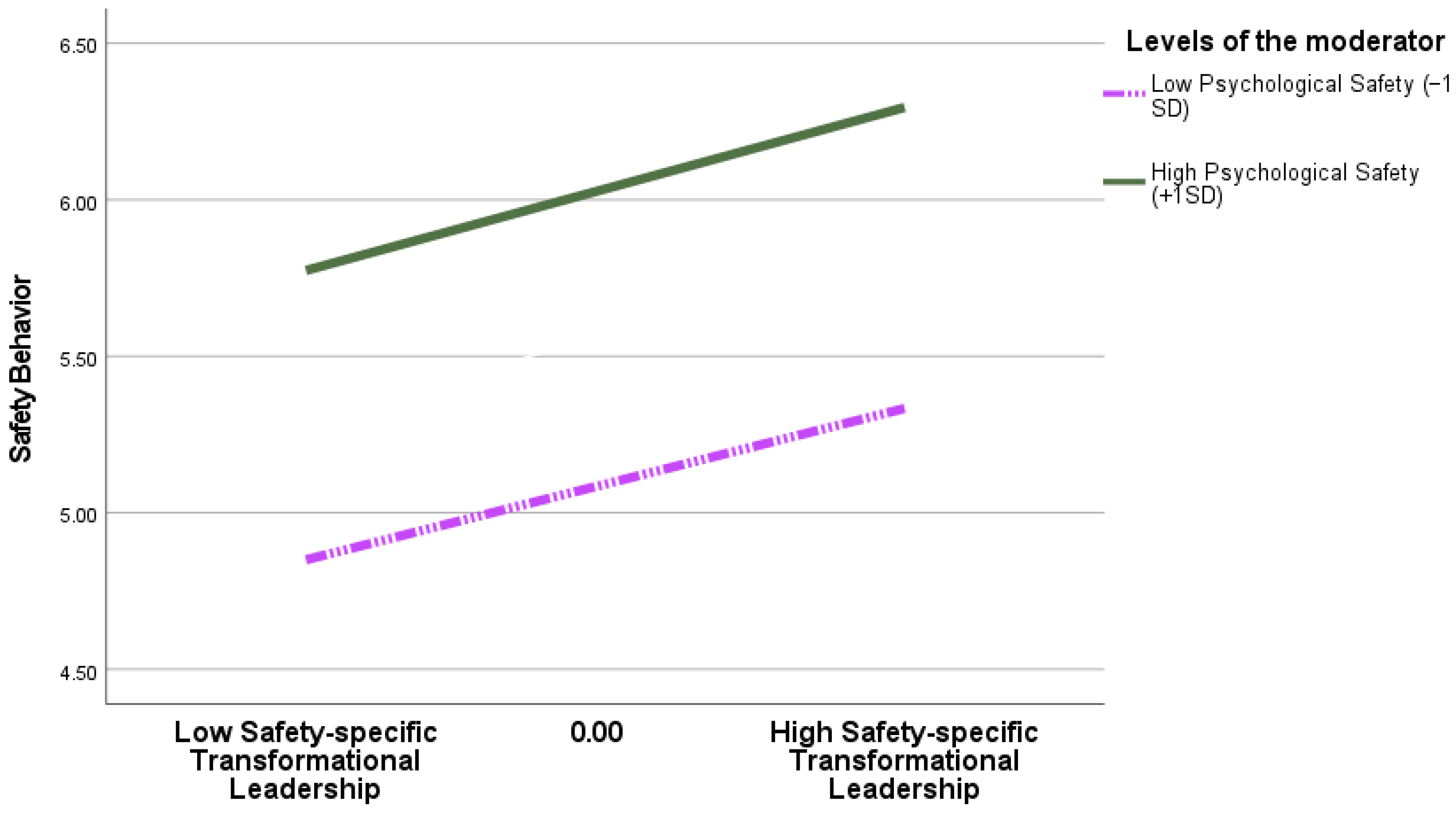

| SSTL × PS | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.727 | 0.469 | −0.020 | 0.043 |

| Experience | −0.008 | 0.027 | −0.312 | 0.755 | −0.061 | 0.044 |

| Education | 0.020 | 0.013 | 1.513 | 0.130 | −0.006 | 0.047 |

| R2 = 0.642 *** | ||||||

| The conditional indirect effect of SSTL on SB through KS at different levels of PS | ||||||

| −1SD (Low) | 0.044 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.068 | ||

| +1SD (High) | 0.053 | 0.015 | 0.023 | 0.082 | ||

| Index of moderation mediation | ||||||

| 0.005 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.011 | |||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Practical Implication

6.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, H.; Shi, X.; Yang, D.; Liu, K. Impact of mindfulness on construction workers’ safety performance: The mediating roles of psychological contract and coping behaviors. Saf. Sci. 2022, 146, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayouz, H.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K. Using benevolent leadership to improve safety behaviour in the construction industry: A moderated mediation model of safety knowledge and safety training and education. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2025, 31, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slil, E.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Impact of Safety Leadership and Employee Morale on Safety Performance: The Moderating Role of Harmonious Safety Passion. Buildings 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafindadi, A.D.; Napiah, M.; Othman, I.; Mikić, M.; Haruna, A.; Alarifi, H.; Al-Ashmori, Y.Y. Analysis of the Causes and Preventive Measures of Fatal Fall-Related Accidents in the Construction Industry. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naser, N.K.; Al-Tabtabai, H. The Impact of Safety Violations on Construction Project Performance: A Case Study of the ADFA Project. J. Eng. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShemeili, H.; Davidson, R.; Khalid, K. Impact of empowering leadership on safety behavior and safety climate: Mediating and moderating role of safety monitoring. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 22, 1282–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Tawaih, K.; Adu, M.A. Work Pressure and Safety Behaviors among Health Workers in Ghana: The Moderating Role of Management Commitment to Safety. Saf. Health Work. 2016, 7, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Sun, Z.; Zong, Z.; Mao, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Maguire, P.; Hu, Y. The effect of benevolent leadership on safety behavior: A moderated mediation model. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. Safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviours. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, K.; Gibbons, A.M.; Johnson, S.K.; Cigularov, K.P.; Chen, P.Y.; Rosecrance, J.C. The differential effects of transformational leadership facets on employee safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ju, C.; Koh, T.Y.; Rowlinson, S.; Bridge, A.J. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Safety Climate and Individual Safety Behavior on Construction Sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barling, J.; Loughlin, C.; Kelloway, E.K. Development and test of a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Wu, T.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Safety-Specific Leadership, Goal Orientation, and Near-Miss Recognition: The Cross-Level Moderating Effects of Safety Climate. Front. Psychol 2019, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; You, X. The influence of safety-specific transformational leadership on safety behavior among Chinese airline pilots: The role of harmonious safety passion and organizational identification. Saf. Sci. 2023, 166, 106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lin, L.; Li, P.P. How to enable employee creativity in a team context: A cross-level mediating process of transformational leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3240–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Gillespie, N.; Mann, L.; Wearing, A. Leadership and trust: Their effect on knowledge sharing and team performance. Manag. Learn. 2010, 41, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, E.-J. Fostering organizational learning through leadership and knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1408–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Lu, T.-E.; Yang, C.C.; Chang, G. A multilevel approach on empowering leadership and safety behavior in the medical industry: The mediating effects of knowledge sharing and safety climate. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Anantatmula, V. Psychological Safety Effects on Knowledge Sharing in Project Teams. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 3876–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.V.; Balasubramanian, S.; Anand, G. The Influence of Psychological Safety and Confidence in Knowledge on Employee Knowledge Sharing. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2009, 11, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ma, Z.; Yu, H.; Jia, M.; Liao, G. Transformational leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Explore the mediating roles of psychological safety and team efficacy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 24, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-L.; Lee, Y.-C. Empowering group leaders encourages knowledge sharing: Integrating the social exchange theory and positive organizational behavior perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L.D. Theoretical Comparisons of Forms of Exchange. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhweildi, M.; Vetbuje, B.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Leading with Green Ethics: How Environmentally Specific Ethical Leadership Enhances Employee Job Performance Through Communication and Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.Q.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Axtell, C.M.; Davies, S. Reconciling general transformational leadership and safety-specific transformational leadership: A paradox perspective. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 84, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Quick, J.C. The emerging positive agenda in organizations: Greater than a trickle, but not yet a deluge. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazlina Zaira, M.; Hadikusumo, B.H.W. Structural equation model of integrated safety intervention practices affecting the safety behaviour of workers in the construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2017, 98, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chang, Y. Relationship between perception of patient safety climate, work pressure and safety behaviour. Cheng Ching Med. J. 2018, 29, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Irshad, M.; Majeed, M.; Khattak, S.A. The Combined Effect of Safety Specific Transformational Leadership and Safety Consciousness on Psychological Well-Being of Healthcare Workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 688463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; DeJoy, D.M.; Dyal, M.-A. Safety specific transformational leadership, safety motivation and personal protective equipment use among firefighters. Saf. Sci. 2020, 131, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, R.; Yang, S.; Huseynova, A.; Atif, M. Spiritual leadership and intellectual capital: Mediating role of psychological safety and knowledge sharing. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 24, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership and employee creativity: Mediating role of creative self-efficacy and moderating role of knowledge sharing. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, N.-I.; Berends, H.; van Baalen, P. Relational models for knowledge sharing behavior. Eur. Manag. J. 2011, 29, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, W.; Qi, L. What matters for knowledge sharing in collectivistic cultures? Empirical evidence from China. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xi, Y. Differentiated transformational leadership and knowledge sharing: A cross-level investigation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.; Lei, H. Determinants of innovation capability: The roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-S.; Yang, C.-S. Safety leadership and safety behavior in container terminal operations. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al’Ararah, K.; Çağlar, D.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Mitigating Job Burnout in Jordanian Public Healthcare: The Interplay between Ethical Leadership, Organizational Climate, and Role Overload. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarbrough, H. Knowledge management, HRM and the innovation process. Int. J. Manpow. 2003, 24, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurier, C.E.; Vincent, C.A.; Parmar, D.G. Learning from errors in nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. Learning from failure in health care: Frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2004, 13 (Suppl. 2), ii3–ii9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.T.; Lee, D.Y.; Park, C.S. A social network system for sharing construction safety and health knowledge. Autom. Constr. 2014, 46, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-P.; Gwak, H.S.; Lee, D.E. Modeling the predictors of safety behavior in construction workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2015, 21, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesheim, T.; Gressgård, L.J. Knowledge sharing in a complex organization: Antecedents and safety effects. Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.T.; Abbas, J.; Lei, S.; Haider, M.J.; Akram, T. Transactional leadership and organizational creativity: Examining the mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1361663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J.T. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- HSE. Health and Safety Statistics: 2023 to 2024 Annual Release. GOV.UK. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/health-and-safety-statistics-2023-to-2024-annual-release (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Loosemore, M.; Malouf, N. Safety training and positive safety attitude formation in the Australian construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SWA. Notifiable Fatalities: December 2015 Monthly Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/notifiable-fatalities-report-december-2015.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Li, H.; Lu, M.; Hsu, S.-C.; Gray, M.; Huang, T. Proactive behavior-based safety management for construction safety improvement. Saf. Sci. 2015, 75, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.H.W.; Goh, Y.M.; Wong, K.L.X. A system dynamics view of a behavior-based safety program in the construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2018, 104, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkesen, S.; Sadikoglu, E.; Jayamanne, E. Assessing psychological safety in lean construction projects in the United States. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Ballard, G.; Arroyo, P.; Hackler, C.; Spencley, R.; Tommelein, I.D. Lean, Psychological Safety, and Behavior-Based Quality: A Focus on People and Value Delivery. Director 2020, 2, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Peterson, S.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Hartnell, C.A. An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Ababneh, B. The relationships between CEOs’ psychological attributes, top management team behavioral integration and firm performance. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2021, 24, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva Dodoo, J.; Surienty, L.; Zahidah, S. Safety citizenship behaviour of miners in Ghana: The effect of hardiness personality disposition and psychological safety. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, L.; Guo, M. The influence of occupational calling on safety performance among train drivers: The role of work engagement and perceived organizational support. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, P.E.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, M. Assessing the effects of safety leadership, employee engagement, and psychological safety on safety performance. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 86, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, Y.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The influence of entrepreneurial innovations in building competitive advantage: The mediating role of entrepreneurial thinking. Kybernetes 2023, 53, 4051–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enbaia, E.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Interplay Between Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Performance: Does Organizational Green Culture and Green Innovation Really Matter? Sustainability 2024, 16, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; McCabe, B.; Jia, G.; Sun, J. Effects of Safety Climate and Safety Behavior on Safety Outcomes between Supervisors and Construction Workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Mullen, J.; Francis, L. Divergent effects of transformational and passive leadership on employee safety. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, N.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, W. Influencing Mechanism of Job Satisfaction on Safety Behavior of New Generation of Construction Workers Based on Chinese Context: The Mediating Roles of Work Engagement and Safety Knowledge Sharing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.F.; Li, X.C.; Wang, Z.N. Safety climate, work pressure and safety behavior. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2014, 10, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, E.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Al-Geitany, S. Destination Social Responsibility and Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Assessing the Mediating Role of Community Attachment and Involvement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashiq, S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. From Sustainable Tourism to Social Engagement: A Value-Belief-Norm Approach to the Roles of Environmental Knowledge, Eco-Destination Image, and Biospheric Value. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cote, J.A.; Buckley, M.R. Estimating Trait, Method, and Error Variance: Generalizing across 70 Construct Validation Studies. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, R.I.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Hamdan, S. Examining the Relationships Between Frontline Bank Employees’ Job Demands and Job Satisfaction: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Ababneh, B.; Emeagwali, L.; Elrehail, H. Strategic Stances and Organizational Performance: Are Strategic Performance Measurement Systems the Missing Link? Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 16, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Dappa, K. The influence of learning orientation on entrepreneurial performance: The role of business model innovation and risk-taking propensity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krara, W.; Alzubi, A.; Khadem, A.; Iyiola, K. The Nexus of Sustainability Innovation, Knowledge Application, and Entrepreneurial Success: Exploring the Role of Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuseta, H.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Digital Technologies and Business Model Innovation in Turbulent Markets: Unlocking the Power of Agility and Absorptive Capacity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkish, I.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Does Digitization Lead to Sustainable Economic Behavior? Investigating the Roles of Employee Well-Being and Learning Orientation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J.; Verdú-Jover, A.J. The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Performance through Knowledge and Innovation. Br. J Manag. 2008, 19, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; McCabe, B.; Jia, G. Effect of leader-member exchange on construction worker safety behavior: Safety climate and psychological capital as the mediators. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inness, M.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Stride, C.B. Transformational leadership and employee safety performance: A within-person, between-jobs design. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MG, S.P.; KS, A.; Rajendran, S.; Sen, K.N. The role of psychological contract in enhancing safety climate and safety behavior in the construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 23, 1189–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. How safety accountability impacts the safety performance of safety managers: A moderated mediating model. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 89, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, O.L.; Zickar, M.J.; Jex, S.M. Role Definition as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Safety Climate and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Hospital Nurses. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Mahdinia, M.; Doosti-Irani, A. Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership and Safety Outcomes at Workplaces: A Scoping Review Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics (n = 706) | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 677 | 95.89 |

| Female | 29 | 4.11 |

| Experience (years) | ||

| Less than one | 23 | 3.26 |

| 1–3 | 102 | 14.45 |

| 3–5 | 89 | 12.61 |

| 5–10 | 364 | 51.55 |

| Above 10 | 128 | 18.13 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 213 | 30.17 |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent | 441 | 62.47 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 14 | 1.98 |

| Others | 38 | 5.38 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Less than 25 | 201 | 28.47 |

| 26–30 | 317 | 44.90 |

| 31–35 | 144 | 20.40 |

| 36–40 | 24 | 3.40 |

| Above 41 | 20 | 2.83 |

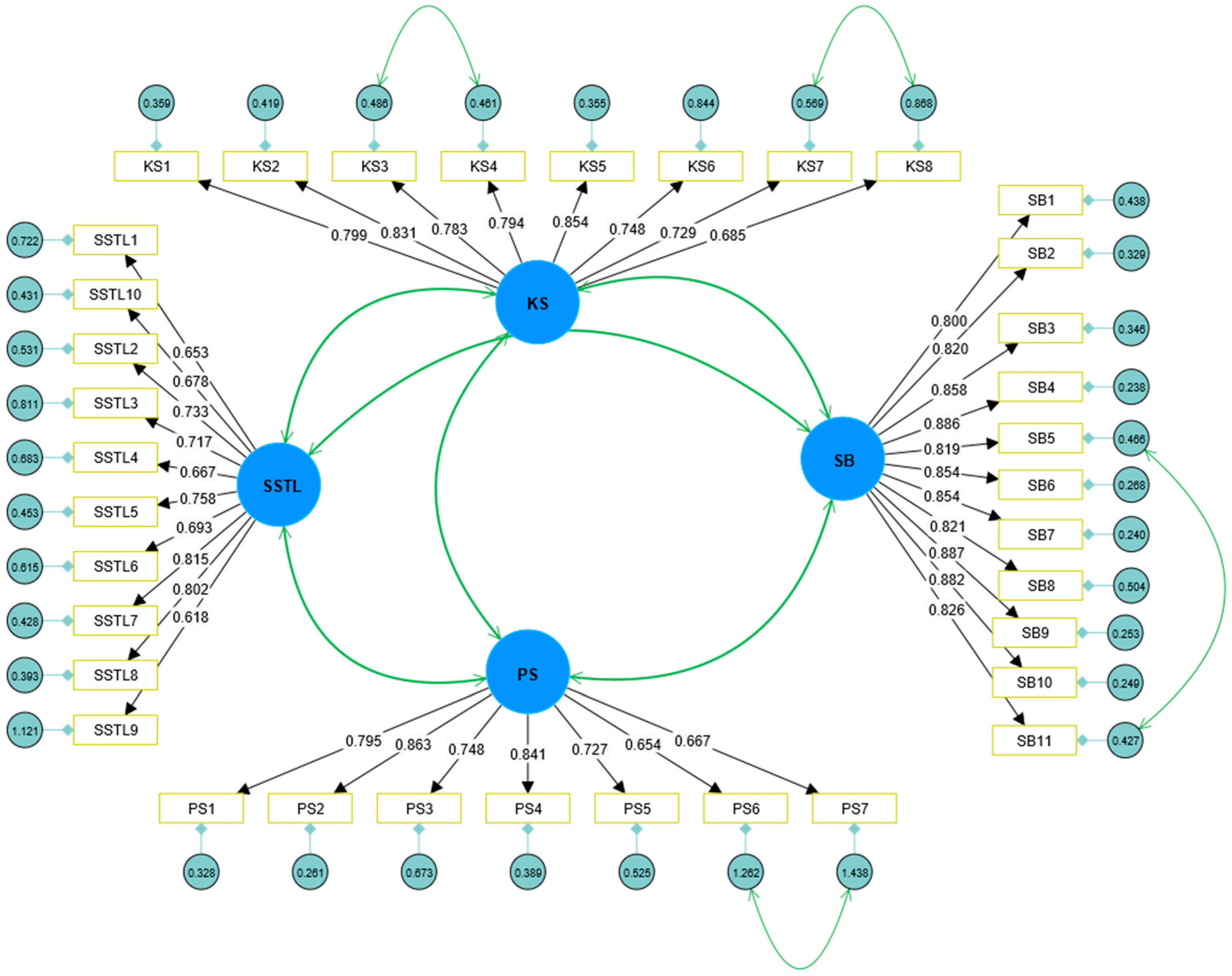

| Construct/Item | Factor Loadings | SMC | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety-specific transformational leadership (SSTL) | 0.909 | 0.913 | 0.513 | ||

| SSTL1 | 0.653 | 0.504 | |||

| SSTL2 | 0.733 | 0.537 | |||

| SSTL3 | 0.717 | 0.514 | |||

| SSTL4 | 0.667 | 0.510 | |||

| SSTL5 | 0.758 | 0.575 | |||

| SSTL6 | 0.693 | 0.508 | |||

| SSTL7 | 0.815 | 0.665 | |||

| SSTL8 | 0.802 | 0.643 | |||

| SSTL9 | 0.618 | 0.502 | |||

| SSTL10 | 0.678 | 0.508 | |||

| Knowledge sharing (KS) | 0.926 | 0.925 | 0.608 | ||

| KS1 | 0.799 | 0.638 | |||

| KS2 | 0.831 | 0.691 | |||

| KS3 | 0.783 | 0.612 | |||

| KS4 | 0.794 | 0.631 | |||

| KS5 | 0.854 | 0.729 | |||

| KS6 | 0.748 | 0.559 | |||

| KS7 | 0.729 | 0.532 | |||

| KS8 | 0.685 | 0.510 | |||

| Psychological safety (PS) | 0.895 | 0.905 | 0.578 | ||

| PS1 | 0.795 | 0.632 | |||

| PS2 | 0.863 | 0.744 | |||

| PS3 | 0.748 | 0.560 | |||

| PS4 | 0.841 | 0.707 | |||

| PS5 | 0.727 | 0.528 | |||

| PS6 | 0.654 | 0.504 | |||

| PS7 | 0.667 | 0.507 | |||

| Safety behavior (SB) | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.717 | ||

| SB1 | 0.800 | 0.639 | |||

| SB2 | 0.820 | 0.672 | |||

| SB3 | 0.858 | 0.736 | |||

| SB4 | 0.886 | 0.785 | |||

| SB5 | 0.819 | 0.672 | |||

| SB6 | 0.854 | 0.729 | |||

| SB7 | 0.854 | 0.729 | |||

| SB8 | 0.821 | 0.674 | |||

| SB9 | 0.887 | 0.786 | |||

| SB10 | 0.882 | 0.779 | |||

| SB11 | 0.826 | 0.682 | |||

| Construct | M | SD | SSTL | KS | PS | SB | Edu | Exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSTL | 5.740 | 0.830 | (0.716) | |||||

| KS | 5.601 | 0.948 | 0.702 ** | (0.780) | ||||

| PS | 4.408 | 0.613 | 0.665 ** | 0.729 ** | (0.760) | |||

| SB | 5.570 | 0.938 | 0.681 ** | 0.670 ** | 0.748 ** | (0.846) | ||

| Edu | - | - | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.016 | - | |

| Exp | - | - | 0.009 | 0.018 | 0.041 | 0.003 | 0.017 | - |

| Goodness of Fit Indices | Recommended Threshold | Reference | Results | Goodness of Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <3 | [74,86,87] | 2.601, p < 0.001 | Fit |

| GFI | >0.9 | 0.905 | Fit | |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.936 | Fit | |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.940 | Fit | |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.941 | Fit | |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.937 | Fit | |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.061 | Fit |

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variable | Estimates (β) | Standard Error | t-Values | p-Values | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1: KS | Intercept | 0.999 | 0.112 | 8.939 | 0.000 | [0.780, 1.219] |

| R2 = 0.493 | SSTL | 0.802 | 0.019 | 41.582 | 0.000 | [0.764, 0.840] |

| M2: SB | Intercept | 0.774 | 0.108 | 7.156 | 0.00 | [0.562, 0.986] |

| SSTL | 0.470 | 0.026 | 18.366 | 0.000 | [0.420, 0.520] | |

| R2 = 0.537 | KS | 0.374 | 0.022 | 16.699 | 0.000 | [0.330, 0.418] |

| The indirect impact of SSTL on safety behavior via knowledge sharing | ||||||

| Direct effect of X on Y | 0.470 | 0.026 | 18.366 | 0.000 | [0.420, 0.520] | |

| Total effect | 0.770 | 0.020 | 39.296 | 0.000 | [0.732, 0.809] | |

| SSTL → KS → SB | 0.300 | 0.024 | [0.255, 0.348] | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, M.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings 2025, 15, 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183340

Ali M, Iyiola K, Alzubi A, Aljuhmani HY. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183340

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Mohamed, Kolawole Iyiola, Ahmad Alzubi, and Hasan Yousef Aljuhmani. 2025. "Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183340

APA StyleAli, M., Iyiola, K., Alzubi, A., & Aljuhmani, H. Y. (2025). Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings, 15(18), 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183340