The Decorative Art and Evolution of the “Xuan” in Ancestral Halls of Southern Anhui

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Complex and Varied Frame Styles

2.1. Frame Styles

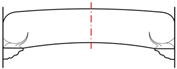

2.1.1. Chuanpeng (Boat-Canopy) Xuan

2.1.2. Renzi (人-Shaped) Xuan

2.1.3. Hejing (Crane-Neck) Xuan

2.2. Combination of Different Frame Styles

3. Multiple and Unified Components

3.1. Main Components

3.2. Accessory Components

4. Evolution Across Time and Different Districts

4.1. Evolution with Time

4.1.1. The Decline of Renzi Xuan and the Development of a Mainstream Frame Style

4.1.2. Standardization of Main Components and Diversification of Accessory Components

4.2. Evolution Across Different Districts

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Dominant style transition: The mid-Ming period marked a pivotal shift in Xuan frame styles, with Chuanpeng Xuan emerging as the dominant architectural form, replacing the previously prevalent Renzi Xuan.

- (2)

- Structural component standardization: The main structural components exhibited a clear tendency towards standardization by the late Qing dynasty. This resulted in the predominance of square short columns and moon beams with refined curvature and optimized height-to-width ratios.

- (3)

- Accessory component diversification: In contrast to structural components, accessory components displayed diversification and became more elaborate, particularly during the commercial boom of the mid-Qing period. This era witnessed the proliferation of intricate elements such as flood-dragon-shaped diagonal braces and S-shaped short beams.

- (4)

- Core–periphery spatial distribution: Spatial analysis revealed a distinct core–periphery distribution pattern of Xuan styles. Mainstream frame styles (especially Chuanpeng Xuan types such as “2Columns2Beams + Short-beam/Xiangbi”) and uniform stylistic applications were densely concentrated in the core counties of Southern Anhui. Conversely, diverse frame style combinations within single halls and the use of niche or complex accessory components tended to cluster in the peripheral border regions.

- (5)

- Socio-historical drivers of evolution: The evolution of Xuan decorative art appears to be correlated with key socio-historical factors. The Jiajing-era ritual reforms enabled ancestral hall proliferation, patronage of Huizhou merchants drove mid-Qing decorative elaboration, innovations in carving tools facilitated the fabrication of intricate accessory components, and resource constraints during wartime in the late Qing dynasty prompted structural simplification and ornament standardization.

Notes

- ➀

- “Southern Anhui” is the abbreviation for Wannan Province. Although the five prefectures (Huizhou, Ningguo, Chizhou, Taiping, and Guangde) within its jurisdiction were established in the 5th year of the Xianfeng reign during the Qing dynasty (1855) and were officially designated as such in the 34th year of the Guangxu reign (1908), the administrative divisions remained relatively stable during earlier periods. During the Ming dynasty, these regions were part of the Southern Metropolitan Region, while in the early Qing dynasty, they fell under the jurisdiction of the Anhui Provincial Administration Commissioner of Jiangnan Province. Therefore, “Southern Anhui” in this study refers to the districts of Huizhou Prefecture, Ningguo Prefecture, Chizhou Prefecture, Taiping Prefecture, and Guangde Prefecture during the Ming and Qing dynasties [24].

- ➁

- The ancestral hall is a place where clans, bound by paternal blood ties, worship their ancestors daily and hold regular rituals [25]. The ancestral halls in Southern Anhui are typically composed of individual buildings that have a front hall, a central hall, and a rear hall. The central hall is the site of the most important rituals, making it the core building of the ancestral hall. The Xuan (a type of attached space) is used in the transitional areas in the front, central, and rear halls. The Xuan is most commonly seen in the central hall, where it not only adds spatial depth but also imparts certain flexibility through its strong decorative elements. The decorative art of Xuan is comprised of the frame style and detailed components, which collectively constitute its form [26].

- ➂

- Academic research on ancestral halls in Southern Anhui has largely focused on the Huizhou Prefecture area, with an emphasis on clan culture, architectural style, spatial organization, and decorative art [27,28,29]. Meanwhile, most studies on the Xuan itself focus on core areas in southern China, such as Suzhou, Wuxi, and Changzhou [30]. In contrast, studies on the Xuan in Southern Anhui, and especially the decorative art and temporal evolution of the Xuan, are fairly limited.

- ➃

- Through field research conducted at 123 cultural relic protection units (provincial level or above) focusing on ancestral halls in Southern Anhui, it was discovered that among various spatial configurations, the Xuan located before the central hall was the most prevalent (115 sites), accounting for 93.5% of the total number of ancestral halls surveyed. This was followed by the Xuan located before the rear hall (51 sites), the Xuan located after the central hall (33 sites), the Xuan positioned before the front hall (26 sites), and the Xuan positioned after the front hall (15 sites). As a focal point of the front hall, the Xuan also exhibited strong representativeness. Therefore, this study focused on ancestral halls where the Xuan is located before the central hall.

- ➄

- There is some debate among scholars regarding the terminology that should be used to describe the type of Xuan found in the ancestral halls of Southern Anhui. For example, Zhu has referred to them as “Juanpeng” or “Renzipeng” [21]. However, Yao used the terms “Chuanpeng Xuan,” “Renzipeng Xuan,” and “Ejing Xuan” [31]. In the “Yingzao Fayuan,” apart from Renzi Xuan, which is not documented, the other two types of Xuan are denoted as “Chuanpeng Xuan” and “Hejing Xuan.” According to the author’s interview with Cheng Huiping, General Manager of Huangshan Damu Ancient Architecture Design Co., Ltd., located in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, China and based on the records regarding the Chuanpeng Xuan and Hejing Xuan in the Yingzao Fayan, this study categorized the three main types of Xuan in ancestral halls as Chuanpeng Xuan, Renzi Xuan, and Hejing Xuan.

- ➅

- Xiangbi is among the most representative decorative components seen in Southern Anhui, and it is usually located on the outer side of short columns. This component is shaped like an elephant’s trunk, with beautiful and curled lines at its ends.The diagonal brace, in traditional Chinese architecture, typically refers to a diagonal structural component that provides support. It is commonly found beneath the eaves of buildings. In the Xuan of ancestral halls in Southern Anhui, diagonal braces function as crucial connectors, linking the shorter columns to the main columns and thereby playing a pivotal structural role.Head-to-head lions are commonly found in regions such as Guichi, Qingyang, and Jing County. These structures are made by stacking multiple pieces of wood and carving them as a single unit. Their name is derived from their unique form, which depicts two lions facing each other with their heads turned towards a central pearl, creating a striking and symbolic visual.

- ➆

- For the sake of convenience, this research divides the Ming and Qing dynasties into early, middle, and late periods. Early Ming dynasty: Hongwu year 1 to Xuande year 10 (1368–1435); Mid-Ming dynasty: Zhengtong year 1 to Jiajing year 45 (1436–1566); Late Ming dynasty: Longqing year 1 to Chongzhen year 17 (1567–1644); Early Qing dynasty: Shunzhi year 1 to Yongzheng year 13 (1644–1735); Mid-Qing dynasty: Qianlong year 1 to Jiaqing year 25 (1736–1820); and Late Qing dynasty: Daoguang year 1 to Xuantong year 3 (1821–1911). In this study, we surveyed ancestral halls built between the early Ming dynasty and the late Qing dynasty [32,33].

- ➇

- In Southern Anhui, the traditional architectural framework along the depth of a building is usually called a “Series,” which is the same as the “Feng/Ceyang” in the Yingzao Fashi and the “Tieshi” in the Yingzao Fayuan. This term appears in classical Chinese architectural records. In “Yuanye,” there are references to “five beams … with one added at the front and rear, making a total of seven beams in a series” and “seven beams, which are the beams that form the roof structure.” This terminology has also been used in other regions of Jiangnan (such as Ningbo). In the traditional five-bay architecture of Southern Anhui, the structures to the east (west) of the central bay are called the east (west) mid-series, east (west) secondary series, and east (west) side series, respectively. With regard to the Xuan frame, some ancestral halls in Southern Anhui have a framework located between two rows, usually between the east and west series or between the series and the side series. This study adopts the customary term used by local craftsmen, i.e., “extra series” [34].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huan, J.; Guo, X.; Guan, Z.; Yan, T.; Chu, T.; Sun, Z. An Experimental Study of The Hysteresis Model of the Kanchuang Frame used in Chinese Traditional Timber Buildings of the Qing Dynasty. Buildings 2022, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, Q.; Song, C.; Jiang, Y. The Influence of Ancestral Temple on the Landscape of Traditional Chinese Villages: Based on Landscape Pattern Analysis and Spatial Syntax Approach. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 4195–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Shi, Y. Research on the Coordinated Development of Traditional Village Protection and Utilization from a Centralized and Contiguous Perspective: Taking Mentougou in Beijing as an Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 41, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Ding, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. A Quantitative Investigation on the Passive Features in Vernacular Mu Nia Tibetan Houses. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D. Solar Passive Features in Vernacular Gyalrong Tibetan Houses: A Quantitative Investigation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Zhang, J. The evolution of Functional Organization in Vernacular Gyalrong Tibetan Houses: A Quantitative Investigation. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2435–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Xia, S.; Gao, M.; Ye, M.; Shi, T. Research on the Spatial Sequence of Building Facades in Huizhou Regional Traditional Villages. Buildings 2023, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lyu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Fan, Z. The Characteristic of Regional Differentiation and Impact Mechanism of Architecture Style of Traditional Residence. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 1864–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N.; Cheng, L. Expressing the Spatial Concepts of Interior Spaces in Residential Buildings of Huizhou, China: Narrative Methods of Wood-Carving Imagery. Buildings 2024, 14, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Tang, Z.; Li, B. Construction and Geo-Distribution of the Architectural Characteristics of Clan Ancestral Halls Along the Yile–Xijing Historical Trail in Lechang. Buildings 2024, 14, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Shan, J. Reverse Geomancy: The Spatial Patterns Between Jimei Ancestral Halls and Their Surrounding Environment. Buildings 2025, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Bahauddin, A.; Miao, J. Sense of Place and Sacred Places: A Phenomenological Study of Ancestral Hall Spatial Narratives—The Shike Ancestral Hall, En Village, Guangdong. Buildings 2025, 15, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y.; Bi, Z. The Culture and Inheritance of Huizhou Architecture: Taking the Design Practice of INK Weiping Tourism Cultural Street as an Example. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis Cedex A, France, 2021; Volume 237, p. 04028. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z. The Evolution of the Living Environment in Suzhou in the Ming and Qing Dynasties Based on Historical Paintings. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Yu, Y.; Tang, Q. English Translation of Traditional Chinese Architectural Terms: Systematic Analysis Based on International Journal Papers. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, C.; Morganti, C.; Bartolomei, C. Traditional Chinese Architecture: The Transmission of Technical Knowledge for the Development of Building Heritage. TEMA 2022, 8, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.Q.; Guo, Y.Q.; Zeng, X. Research of Architectural Art and Environment Design of South Anhui’s Ancient Residence. AMM 2014, 584–586, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.Z.; Bi, Z.S. On the Structural Elements Features of Ancestral Temple in Huizhou. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Civil, Architecture and Pollution Control (ICCAPC 2021), Suzhou, China, 12–14 March 2021; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 760, p. 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z. Study on Chinese Characters How to Represent Chinese Ancient Architectural Culture. US-China Foreign Lang. 2024, 22, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-Y.; Kılınçer, N.Y.; Aboutalebi Tabrizi, H. Illustrations of the 1925-Edition Yingzao Fashi 營造法式: Jørn Utzon’s Aesthetic Confirmation and Inspiration for the Sydney Opera House Design (1958–1966). J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Pan, G.T. Several Regional Characteristics of Dougong in Ming and Qing Dynasty Architecture in Huizhou. Archit. J. 1998, 6, 59–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Sharudin, S.A.; Xu, Y. Study on the Influencing Factors and Mechanisms of the Evolution of the Architectural Characteristics of Guangfu Ancestral Halls in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. JWA 2024, 8, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Cai, X. A Cultural Geography Study of the Spatial Art and Cultural Features of the Interior of Lingnan Ancestral Halls in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3128–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huadong, G. Ancient Villages in Southern Anhui—Xidi and Hongcun. In Atlas of Remote Sensing for World Heritage: China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Ancestral Hall and Ancestor Veneration Narrative of a Huizhou Lineage in Ming–Qing China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, A.; Hielscher, A. Materiality as Decor: Aesthetics, Semantics and Function. In Materiality in Roman Art and Architecture: Aesthetics, Semantics and Function; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.P.; He, H.; Feng, Q.; Hu, J.J.; Guo, L. Destination Imagery of Ancient Villages in Southern Anhui Province Based on Tourists’ Photos: A Case from Hongcun Village. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yang, X. Spatial Symbols: An Analysis of Cultural Characteristics of Interior Furnishings in Huizhou Residential Houses. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2024, 47, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Yu, H.; Chen, T. Identifying Elements of Nostalgia Culture from a Tourism Perspective: Taking the Ancient Huizhou Cultural Tourism Area as Case Study. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 2237–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Ikebe, K. Urban Heritage Conservation and Modern Urban Development from the Perspective of the Historic Urban Landscape Approach: A Case Study of Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.Y. The Impact of Architectural Reforms in the Ming Dynasty on the Roofs of Huizhou-style Buildings. Tradit. Chin. Archit. Gardens 2010, 3, 61–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, G.; Xu, W.; Kong, D.; Gao, X.; Wang, S.; Feng, C. The Locust Plagues in the Yangtze River Delta of China during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Nat. Hazards 2023, 115, 2333–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Hu, M.; Somenahalli, S.; Bian, X.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, Y. A Study of Spatio-Temporal Differentiation Characteristics and Driving Factors of Shaanxi Province’s Traditional Heritage Villages. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, M. Economy and Extravagance in Craft Culture: The Deployment of a Grand Building Code in Chinese Construction History. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3160–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Facade | Section | Representative Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photographs | Name | Period, District | ||||

| Short Column | Circular section column |  |  |  | Zheng‘s ancestral hall | Late Ming Dynasty, Yi County |

| Square-section column |  |  |  | Tangyue Bao’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| Square section with smoothed edges |  |  |  | Huang’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Xiuning County | |

| Special section column |  |  |  | Ye‘s ancestral hall | Early Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| Beam | Round and robust Donggua beam |  |  |  | Taihu Wu’s ancestral hall | Late Ming Dynasty, Yi County |

| Tall and slender Donggua beam |  |  |  | Hong’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Taiping County | |

| Moon beam analogous to that depicted in the “Yingzao Fashi” |  |  |  | Nanping Cheng’s ancestral hall | Late Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| Straight beam |  |  |  | Nanping Ye’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| Type | Facade | Representative Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photographs | Name | Time, District | |||

| Diagonal brace | Arc-shaped |  |  | Yangchun Fang’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Wuyuan County |

| Flood-dragon-shaped |  |  | Xichong Yu’s ancestral hall | Mid-Qing Dynasty, Wuyuan County | |

| Dingtou arch | Hollow-shaped |  |  | Huang’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Xiuning County |

| Centrally decorated |  |  | Xu’s ancestral hall | Late Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| Arch eye-eliminated |  |  | Chifeng Pan’s ancestral hall | Late Qing Dynasty, Wuyuan County | |

| Queti | Overall sculpture molding |  |  | Longchuan Hu’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Jixi County |

| Flat engraving pattern |  |  | Hong’s ancestral hall | Mid-Qing Dynasty, Taiping County | |

| Short- beam | Horizontal moon beam |  |  | Hang’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Yi County |

| C-shaped tilted beam |  |  | Hang’s ancestral hall | Late Ming Dynasty, Yi County | |

| S-shaped twisted beam |  |  | Baigong’s ancestral hall | Mid-Qing Dynasty, Jixi County | |

| Xiangbi-shaped beam |  |  | Wangkou Yu’s ancestral hall | Mid-Qing Dynasty, Wuyuan County | |

| Xiangbi | Curls outwards |  |  | Tangyue Bao’s ancestral hall | Mid-Ming Dynasty, Yi County |

| Curls inwards |  |  | Huang’s ancestral hall | Early Qing Dynasty, Wuyuan County | |

| Time Period | Typical Decorative Feature Changes | Social Background | Sociopolitical/Technological Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-Ming Dynasty | Standardization of frameworks | Economic prosperity and social stability drove the first wave of ancestral hall construction. Craftsmanship transitioned from imitating “Yingzao Fashi” toward developing localized structural systems. | Policy support: Jiajing-era ritual reforms legalized ancestor worship, increasing clan organization and construction demands. Technological developments: Timber framing techniques were explored on a region-specific level. |

| Late Ming Dynasty | Diversification of components | The continued construction boom fostered technical specialization. Southern Anhui merchants accumulated capital, which was injected into architectural ornamentation. | Relaxation of artisan registration: Increased mobility of craftsmen facilitated cross-regional knowledge exchange. Functional refinement: Localized adaptations of structural components occurred. |

| Mid-Qing Dynasty | Development of more elaborate carvings | The economic peak under the patronage of merchants from Southern Anhui drove decorative rivalry. Social competition among clans led to the development of ornate designs. | Tool innovation: Advanced carving techniques were introduced. Commercial influence: Ostentatious aesthetics reflected wealth display. |

| Late Qing Dynasty | Simplification of components | Resource scarcity occurred due to wars and economic decline. There was a pragmatic shift toward cost-effective construction. | Western technological impact: Mechanized production reduced reliance on handcrafted decorations. Functional prioritization: Overly complex designs were abandoned due to maintenance challenges. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, Y.; Cai, J.; Jiang, L. The Decorative Art and Evolution of the “Xuan” in Ancestral Halls of Southern Anhui. Buildings 2025, 15, 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183294

Fan Y, Cai J, Jiang L. The Decorative Art and Evolution of the “Xuan” in Ancestral Halls of Southern Anhui. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183294

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Yilun, Jun Cai, and Liwen Jiang. 2025. "The Decorative Art and Evolution of the “Xuan” in Ancestral Halls of Southern Anhui" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183294

APA StyleFan, Y., Cai, J., & Jiang, L. (2025). The Decorative Art and Evolution of the “Xuan” in Ancestral Halls of Southern Anhui. Buildings, 15(18), 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183294