1. Introduction

Under the background of accelerated knowledge iteration in the digital era, mega projects serve as key drivers in the construction of the national infrastructure system and the optimization of the industrial structure. The improvement of their implementation efficiency and innovation performance has become one of the core driving forces for achieving high-quality economic and social development. Compared with conventional construction projects, mega projects involve greater investment scales, more complex technical requirements, and a broader range of stakeholders [

1], making them a vital component of China’s modern engineering system. However, these characteristics also expose complex engineering projects to technological, managerial, financial, and market risks [

2]. Precisely because of such high levels of risk and uncertainty, project organizations need to foster a favorable organizational context to promote the sharing of tacit knowledge among members, thereby mitigating risks, addressing problems, and ultimately enhancing both innovation performance and the likelihood of project success. Therefore, establishing a systematic innovation-driven mechanism is critical not only for optimizing the effectiveness of full life-cycle project management, but also for facilitating the digital transformation and sustainable development of the construction industry.

The innovative performance of mega projects not only relies on technological breakthroughs but also depends on the organization’s ability to coordinate dynamic organizational contexts and the efficiency of tacit knowledge sharing and transformation. The resource-based theory posits that the rational allocation and utilization of resources enables organizations to establish sustainable competitive advantages [

3]. Knowledge resources, as a fundamental means of acquiring and leveraging organizational assets, constitute an indispensable foundation for project innovation [

4]. Polanyi [

5] first classified knowledge into tacit and explicit forms. Tacit knowledge, which originates from long-term practical experience, is characterized by specificity and practicality. People often absorb and apply tacit knowledge unconsciously and passively, making it difficult to articulate clearly to others. Moreover, tacit knowledge can only be effectively shared through interactive communication and practical engagement. Tacit knowledge is widely recognized as a critical resource for strategic innovation and a foundation for establishing sustainable competitive advantage. Compared with explicit knowledge, tacit knowledge relies more heavily on experiential exchange and socialization processes, which render its transfer more challenging. Consequently, tacit knowledge sharing is not only a core component of knowledge management but also an essential mechanism for strengthening organizational innovation capability. Recent empirical studies consistently emphasize the pivotal role of knowledge sharing in driving innovation performance. At the macro level, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (KBDCs) foster innovation through knowledge creation, diffusion, absorption, and application. Knowledge creation is the strongest predictor of innovation performance in developed and developing economies, whereas knowledge absorption exerts the greatest influence in transitional economies, underscoring the importance of knowledge-related capabilities [

6]. At the firm level, management innovation—encompassing new structures, processes, and practices—significantly enhances innovation outcomes in SMEs. External knowledge search breadth acts as a partial mediator, highlighting the critical role of knowledge acquisition and sharing mechanisms [

7]. Similarly, digital transformation directly fosters green technological innovation performance and additionally exerts a mediating effect through internal knowledge sharing [

8]. At the project level, digital capability of project teams positively influences innovation performance, with value co-creation serving as a mediator fundamentally dependent on intra- and inter-team knowledge exchange [

9]. Overall, across both macro-level innovation ecosystems and micro-level organizational and project practices, knowledge sharing consistently emerges as a central mediator and driver of innovation performance. Nevertheless, although extensive research has examined traditional knowledge management, a comprehensive understanding of tacit knowledge and its linkages with organizational context and innovation performance remains limited. This gap underscores the importance and necessity of further exploring the role of tacit knowledge sharing [

10]. Due to their provisionality and the scarcity of sharing environments, individual knowledge and experience generated during the implementation of mega projects stay in the minds of organizational members and are lost with the dissolution of the organization after the completion of the project, leading to increased difficulties in sharing tacit knowledge during the implementation of the project in all phases [

11]. Therefore, further elucidating the mechanism of tacit knowledge sharing in linking organizational context with innovation performance is of critical significance for strengthening managerial effectiveness and advancing the innovation capability of complex engineering projects.

With the dynamic evolution of governance mechanisms in mega projects and the ongoing improvement of governance capacity, the organizational context have become increasingly susceptible to the influence of institutional environments, resource constraints, and organizational climate [

12]. As a system encompassing deep-seated values and behavioral norms, organizational culture shapes the project team’s cognitive and behavioral patterns toward innovation through contextual embedding. In contrast, organizational structure provides infrastructural support for innovation activities by delineating authority and responsibility, establishing coordination mechanisms, and facilitating information flow. According to social exchange theory, resource interactions among actors can be conceptualized as a form of reciprocal exchange. The core premise of this theory is that relationships among individuals follow the principle of reciprocity, whereby the returns from exchange encompass not only material benefits but also psychological outcomes, including support, trust, and cooperation. Resource exchange can occur through formal contractual arrangements or through interpersonal trust. In recent years, research on organizational context has shifted from focusing on its conceptualization and definitions to examining the mechanisms through which different contextual elements influence innovation and knowledge processes. A review of the existing literature reveals that current studies on organizational context primarily address the following dimensions: in terms of research content, it mainly focuses on the impact of organizational context on knowledge-sharing behavior [

13] and knowledge-sharing willingness [

14], the impact of organizational context on employees’ and organizations’ performance [

15], and the impact of organizational context on organizational learning [

16], etc.; in terms of the research object, studies on organizational context mainly concentrate on individual employees [

15], small- and medium-sized enterprises, and within business organizations [

13]. From a knowledge management perspective, the mechanisms by which the sharing of tacit knowledge affects the organizational environment and innovation performance remain under-researched. This is particularly true in the field of mega projects. Despite a growing academic interest in organizational context and innovation performance under the broader innovation-driven development strategy, existing studies tend to treat organizational context as a single static factor, focusing on enterprise-level environments or generalized effects on knowledge sharing and transfer. There is a notable gap in understanding the deeper mechanisms by which organizational context affects innovation outcomes in large-scale, multi-stakeholder projects, as well as the mediating or moderating role of tacit knowledge sharing in this process.

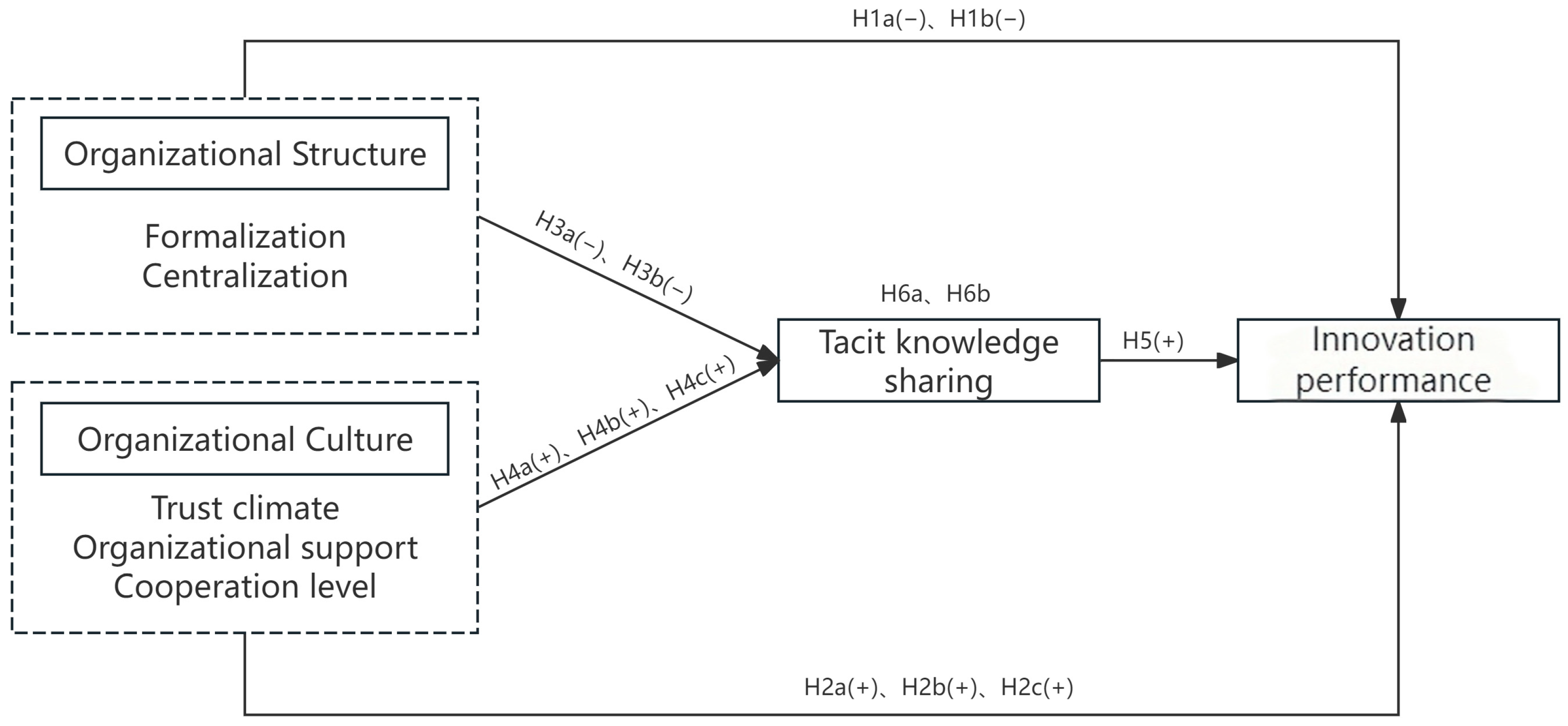

In summary, investigating the influence of organizational context on innovation performance in mega projects is of substantial value. Such research provides important theoretical and practical insights. These insights are essential for constructing a compatible organizational environment that fosters significant advancements in innovation capability and outcomes. This study develops a mechanism model with tacit knowledge sharing as a mediating variable, systematically analyzes the multidimensional components of organizational context, and proposes a research hypothesis framework structured as “organizational context—tacit knowledge sharing—innovation performance”. In the first phase, hypotheses concerning the effects of organizational context and tacit knowledge sharing on innovation performance were derived from a comprehensive literature review, leading to the construction of a theoretical model. Subsequently, the theoretical model was empirically tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

5. Discussion

This study empirically investigates the influence of organizational context on innovation performance in mega projects. At the structural level, centralization exerts a significant inhibitory effect, whereas formalization shows no direct impact. In highly centralized environments, the excessive concentration of decision-making authority limits frontline teams’ autonomy and capacity for experimentation, thereby constraining creativity and flexibility. Unlike Damanpour [

20] and Zhou Guohua [

14], who found that formalization hinders innovation in corporate and project-based settings, this study demonstrates that, in multi-stakeholder mega projects, its effect is context-dependent. Under decentralized conditions, formalization—through institutionalized procedures and standardized frameworks—mitigates uncertainty, delineates responsibilities, and fosters cross-organizational knowledge integration. Thus, whereas centralization consistently imposes a negative effect, formalization exerts dual, context-contingent influences. Further analysis indicates that neither centralization nor formalization alone significantly influences tacit knowledge sharing. However, their combination severely restricts informal exchanges, corroborating the “over-rigidity effect” described in institutional complementarity theory [

63]. Accordingly, this study advocates a “decentralization–formalization” structure that balances flexibility and control, reduces decision bottlenecks, and provides institutional safeguards for knowledge sharing. Characterized by decentralized decision-making and clear procedural norms, this configuration alleviates the constraints of centralization and fosters cross-organizational tacit knowledge flows, providing organizational assurance for sustainable knowledge sharing.

Secondly, at the cultural level, this study aligns with Boadu [

30] and Rajan [

33], confirming that a climate of trust and organizational support significantly enhances both innovation performance and tacit knowledge sharing. However, this finding contrasts with Liu Jingtao [

36], who argued that inter-organizational cooperation exerts no direct on innovation performance, likely because of the complexity and multi-stakeholder nature of mega projects. Without deep collaborative mechanisms, cooperation often remains limited to task allocation or information exchange, hindering substantive innovation outcomes. Only in a high-trust environment can informal communication and experiential sharing transcend organizational boundaries, enabling effective tacit knowledge sharing and improving innovation performance.

Finally, this study highlights the critical mediating role of tacit knowledge sharing in driving innovation performance. Cross-organizational tacit knowledge sharing directly enhances project management efficiency and innovation potential, partially mediates the effects of formalization, centralization, trust climate, and organizational support, and fully mediates the relationship between cooperation and innovation performance. These findings suggest that cooperation alone is insufficient to realize innovation outcomes; only when tacit knowledge sharing is deeply embedded can cooperative relationships translate into substantive innovation performance. Accordingly, project managers should prioritize building trust mechanisms, fostering a supportive knowledge-sharing environment, refining institutional and incentive systems, and promoting cross-organizational learning to fully leverage tacit knowledge sharing’s mediating role.

In summary, this study elucidates the underlying mechanisms linking organizational context, tacit knowledge sharing, and innovation performance in complex engineering projects. The findings contribute to enhancing the efficiency of knowledge transfer and integration while providing institutional and cultural safeguards for achieving innovation performance. Moreover, they provide systematic support for a paradigm shift in knowledge management and the governance of complex engineering projects.

6. Conclusions and Implications

From a mega project management perspective, this study used questionnaire data and applied Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the relationship between organizational context and innovation performance. The analysis focused on two core dimensions—organizational structure and organizational culture—with tacit knowledge sharing as a mediating variable. Results indicate that organizational structure, particularly centralization, has a significant negative effect on innovation performance, whereas formalization shows context-dependent effects. Organizational culture, especially a climate of trust and organizational support, positively influences both tacit knowledge sharing and innovation performance. By contrast, cooperation alone does not directly enhance innovation performance, but its effect becomes significant when mediated by tacit knowledge sharing. Among these factors, tacit knowledge sharing is the strongest driver of innovation performance, followed by trust climate and organizational support, whereas centralization functions mainly as an inhibiting factor.

Theoretically, this study elucidates the mediating role of tacit knowledge sharing between organizational context and innovation performance, thereby extending the scope of research on knowledge management and innovation performance. It advances understanding of how organizational structure, culture, and cooperative mechanisms jointly shape innovation outcomes. Moreover, the proposed “organizational context–tacit knowledge sharing–innovation performance” framework offers a novel reference for governing complex engineering projects and advancing knowledge integration research. Practically, this study offers important managerial implications. Project managers should prioritize building trust mechanisms, fostering a supportive organizational climate, and adopting a “decentralization–formalization” structure to reduce bottlenecks and promote cross-organizational knowledge sharing. However, implementing such a structure poses challenges, particularly in large-scale, multi-stakeholder projects. A balanced approach—characterized by “strategic centralization and decentralized execution” supported by digital platforms (e.g., BIM and digital twins), and reinforced by contracts, performance evaluation, and joint governance bodies—can reconcile flexibility with control. In this way, decentralization mitigates bottlenecks, while formalization provides safeguards for cross-organizational collaboration and knowledge sharing. Together, these mechanisms yield valuable insights for enhancing innovation performance in mega projects.

7. Limitations

Despite its contributions to revealing the mechanisms linking organizational context, tacit knowledge sharing, and innovation performance in mega projects, this study has several limitations. First, reliance on cross-sectional survey data captures only static associations, making it challenging to track the dynamic evolution of organizational structures, cultures, and knowledge-sharing mechanisms throughout the project lifecycle. Future research should employ longitudinal designs and collect processual data from mega projects to more accurately capture temporal relationships and evolutionary trajectories, thereby strengthening causal inference and model robustness. Second, because this study is grounded in the Chinese context, it does not consider potential moderating effects of cross-national cultural differences. In international mega projects, cultural dimensions such as power distance, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance may significantly shape the relationships among organizational culture, tacit knowledge sharing, and innovation performance. Future research should draw on cross-cultural management theories and cultural dimension frameworks to examine these effects, thereby enhancing the model’s generalizability and explanatory power. Finally, this study focuses on organizational context and tacit knowledge sharing as core drivers. Although this clarifies their mechanisms, the model’s explanatory power remains limited. Future research should incorporate additional variables such as project scale and the use of digital tools (e.g., BIM and digital platforms) to build a more comprehensive multi-factor model of innovation performance. This will enhance the completeness and external validity of the framework.