1. Introduction

The engineering–procurement–construction (EPC) approach, as a fast-track delivery method, has been increasingly adopted in competitive international markets because of its high efficiency in integrating diverse design, procurement, and construction processes simultaneously [

1,

2]. By the end of 2032, the EPC market worldwide is projected to expand at a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 5.7% to reach USD 13,800 billion [

3]. In China, the largest developing country in the world, the EPC approach also has a promising future. For instance, the investment in China’s EPC projects increased from RMB 55.765 billion in 2012 to RMB 117.1 billion in 2018 [

4]. However, a limited number of companies are competent enough to fulfill the EPC tasks while relying only on their own capacities [

5], and a great number of EPC contractors are construction companies. Chinese EPC contractors’ strengths are primarily in construction [

5,

6].

Construction project design develops integrated sets of plans, drawings, and specifications. These documents must be clear, comprehensive, detailed, and meet client requirements within resource, technological, financial, and environmental constraints [

5,

7,

8]. An appropriate level of owner design is sufficient to describe the owner’s requirements but not to discourage the contractor from offering innovative design solutions [

9,

10]. Extensive owner-led design prior to contractor selection fragments project phases, resembling traditional design–bid–build (DBB) procurement [

10]. In contrast, EPC contractor design management commences with conceptual design review to define client requirements [

7,

11] and encompasses subsequent phases. The design phase has the highest level of influence in EPC projects, as many key decisions will be made during the pre-project planning and design phases [

12]. These decisions will significantly affect design management and project performance in terms of cost, quality, and schedule. Moreover, a quantitative investigation based on Chinese construction companies has also come to the conclusion that design management has the strongest effect on EPC project cost [

5]. So, design management is critical for construction companies involved as EPC contractors [

5]. For China, whose EPC approach is still in the early stage, design management is extremely important for construction companies functioning as EPC contractors.

EPC contractors’ design management starts by reviewing a conceptual design that defines clients’ expectations and requirements and prepares satisfying proposals to win contracts [

7,

11]. However, because of China’s low level of social trust [

13,

14], EPC project owners still retain more project control rights instead of delegating them to contractors. As a result, the control rights (e.g., design management right) entrusted to EPC contractors are often insufficient [

15]. EPC project design management in China persists in the owner-led mode [

10]. This frequently causes execution-stage design changes, resulting in delays, cost over-runs, and uncontrolled investment [

16,

17]. This is because owners and general contractors usually have different interests. So, design management problems and even design management failure occurs frequently in Chinese EPC projects. However, scholars have not focused on this design interest paradox [

18,

19]. As a result, EPC project design management struggles to operate smoothly. Consequently, this study aims to address this research gap.

The value co-creation theory proposed by Prahalad and Ramaswamy [

20,

21] has two core ideas. One is that the co-creation of consumer experience is at the heart of value co-creation between consumers and firms, and the other is that the interaction among value network members is the way to achieve value co-creation. This theory is widely applied across diverse fields, including manufacturing, services, production, and consumer sectors [

22,

23,

24]. It addresses key issues such as improving service quality and productivity [

25], enhancing brand value [

26], and boosting enterprise management efficiency [

27]. Moreover, based on value co-creation theory, Prahalad et al. [

20] and Ramaswamy [

28] further proposed the DART model, which consists of four components: dialogue, access, risk assessment and transparency.

Dialogue means interactivity, engagement, and a propensity to act-on both sides.

Access begins with information and tools. And risk refers to the possibility of causing harm to consumers, so

risk assessment is the process of analyzing potential events that may result in the loss of an asset, loan, or investment. As for

transparency, it refers to information about products, technologies, and business systems becoming more accessible [

29]. In short, the combination of these four elements can give full play to the advantages of all participants, better promoting cooperation and communication among cooperative partners and strengthening information exchange and sharing. As a result, a win–win situation among cooperative partners could come to pass. The DART model based on value co-creation theory provides a new idea to eliminate the design interest paradox between Chinese EPC project owners and general contractors. Moreover, the PDCA cycle is widely applicable to various industries and is especially useful when quick improvements are desired [

30]. Unfortunately, there is no related research that applies the DART model and PDCA cycle to the design management of Chinese EPC projects.

To fill this research gap, this research constructs a “DART-PDCA” design management model based on the value co-creation theory and the PDCA cycle. The purpose of this research is as follows: (1) defining the “two-stage design interest paradox” and discussing the manifestation of the “two-stage design interest paradox” of Chinese EPC projects; (2) showing the outcomes in the case EPC projects by application of the DART-PDCA model; (3) and providing effective practice guidance to eliminate the design interest paradox for Chinese EPC project owners and general contractors. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the theoretical background related to this study. Then,

Section 3 establishes the research framework and proposes several case study questions.

Section 4 discusses the manifestation of the paradox and reports the outcomes of the case projects.

Section 5 shows the theoretical and practical implications of the present research. And this study concludes with

Section 6, consisting of findings, contributions, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining the “Two-Stage Design Interest Paradox” from the Value Engineering Perspective

The conflicts of interest among construction project stakeholders are a persistent challenge, often framed through established theoretical lenses such as principal–agent problems (focusing on information asymmetry and opportunistic behavior) or goal incongruence (emphasizing misaligned objectives). However, these traditional lenses inadequately capture the collaborative yet conflicted dynamic between owners and general contractors in the design phase of Chinese EPC projects.

Unlike principal–agent theory’s presumption of adversarial relationships [

31,

32], or goal incongruence’s oversight of joint value drivers, the observed paradox emerges from a context where structured collaboration is contractually mandated yet undermined by conflicting incentives:

- (1)

Owners seek to maximize project value (Value = Function/Cost) through cost control and functional optimization [

33,

34];

- (2)

General contractors, constrained by EPC’s lump-sum contracts and design–build integration, prioritize profit protection by linking functional upgrades to proportional cost increases [

35].

This tension constitutes the “two-stage design interest paradox,” a cyclical conflict where both parties depend on collaboration to achieve project goals yet their incentive structures fundamentally impede value co-creation.

So, compared with the principal–agent theory and goal incongruence, value co-creation theory provides the optimal framework for defining and resolving this paradox because (1) it addresses the necessary interdependence of owners and general contractors—a core feature ignored by principal–agent models; (2) it centers on joint value generation (Value = Function/Cost) rather than static goal alignment, transcending goal incongruence’s limitations; and (3) its pillars (dialogue, access, risk-sharing, transparency) directly map to the paradox’s drivers (e.g., design ambiguity, information barriers, and risk misallocation).

2.2. Value Co-Creation Theory and the PDCA Cycle

Value co-creation, which is being developed as a new paradigm in the management literature, allows companies and customers to create value through interaction [

36]. Prahalad and Ramaswamy [

37] introduce value co-creation by acknowledging changing roles in the theater of the market: Customers and suppliers interact and largely collaborate beyond the price system that traditionally mediates supply–demand relationships. From the value co-creation perspective, suppliers and customers are, conversely, no longer on opposite sides but interact with each other for the development of new business opportunities [

20,

34]. Other perspectives to be considered when delineating the value co-creation field’s boundaries in management-related theories are those of innovation studies [

38,

39], business marketing [

40,

41], experiential marketing [

42,

43,

44], and branding marketing [

45]. However, value co-creation theory has attracted little interest from construction management researchers.

Critically, this theory is uniquely suited to address the EPC design interest paradox because it transcends traditional governance frameworks (e.g., transaction cost economics focusing on opportunism mitigation, or relational governance emphasizing trust-building). While these established theories address either conflict or cooperation, value co-creation explicitly navigates the tension between necessary collaboration and inherent goal conflicts in EPC design—a dynamic central to the paradox. Its DART pillars (dialogue, access, risk, transparency) provide direct mechanisms to align owner–general contractors incentives through structured interaction, rather than merely enforcing compliance or assuming goodwill.

The PDCA (plan–do–check–act) cycle is based on the “Shewhart cycle,” and was made popular by W. Edwards Deming [

46], who developed a statistical process control chart in the Bell Laboratories in the USA during 1930s [

47]. PDCA is a quality management system that is used to coordinate continuous improvement efforts [

47] and is widely used in many sectors and fields [

48]. The PDCA has been embraced as an excellent foundation for, and foray into, quality improvement for many fields as it is both simple and powerful. For instance, in Toyota’s culture, the PDCA method is daily used as a problem-solving method to ensure fact-based solutions and to avoid solutions which only remove symptoms [

49]. Moreover, the PDCA cycle is designed to be used as a dynamic model, and completion of one round of the cycle flows into the beginning of a new cycle [

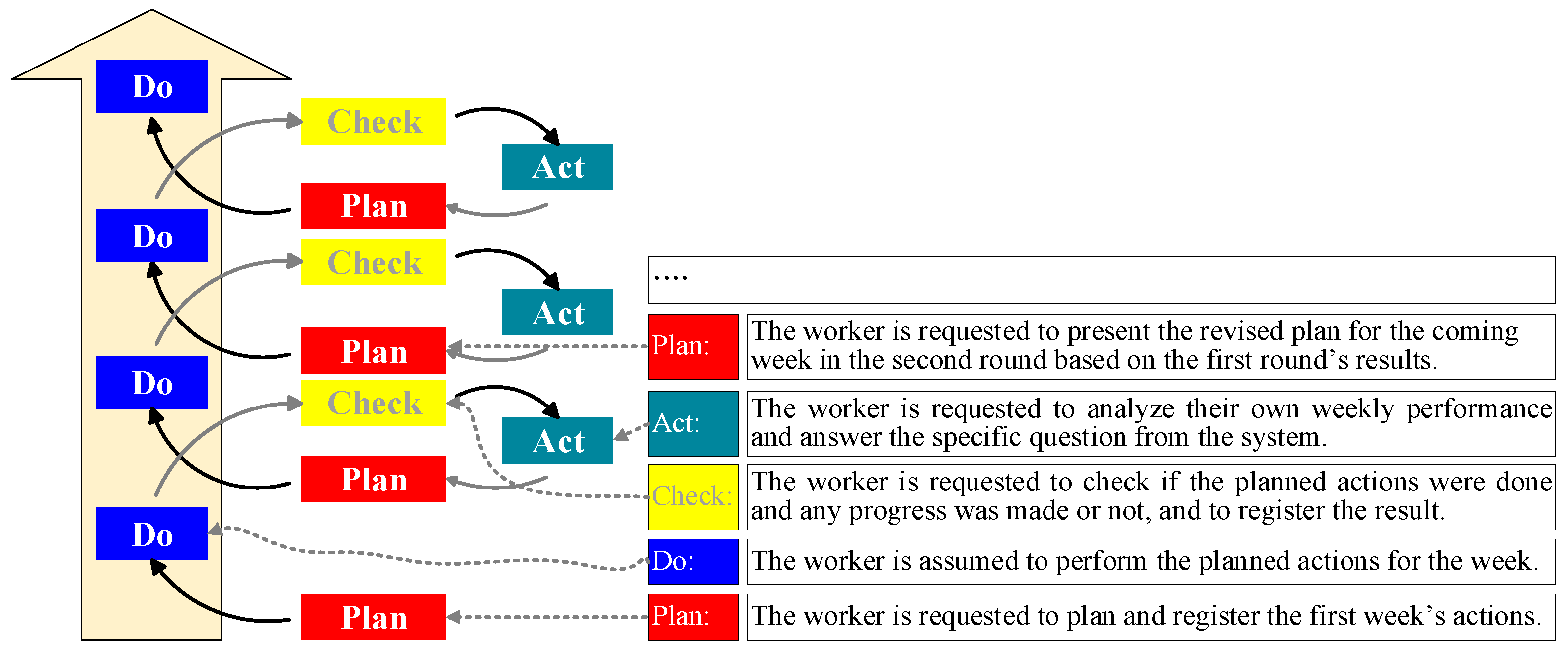

50]. A four-round PDCA cycle for improving knowledge workers’ weekly performance is shown in

Figure 1. Moreover, the PDCA cycle has proven versatility in driving incremental changes for continuous improvement of the systems, processes, and operational activities in an enterprise [

51]. However, researchers in the construction management field seldom pay attention to the role of the PDCA cycle in improving design management performance.

The integration of PDCA with value co-creation is strategically optimal for resolving the EPC paradox for three reasons: (1) PDCA’s iterative structure operationalizes DART principles into actionable phases (e.g., Plan = Dialogue/Risk-sharing; Do = Access/Transparency), enabling systematic co-creation; (2) unlike static governance models (e.g., contract-based enforcement), PDCA’s cyclical nature allows for the adaptive recalibration of collaborative mechanisms as design evolves; and (3) it compensates for value co-creation’s lack of process granularity by providing a scalable implementation framework—a gap unaddressed by alternative theories like agency or transaction cost approaches.

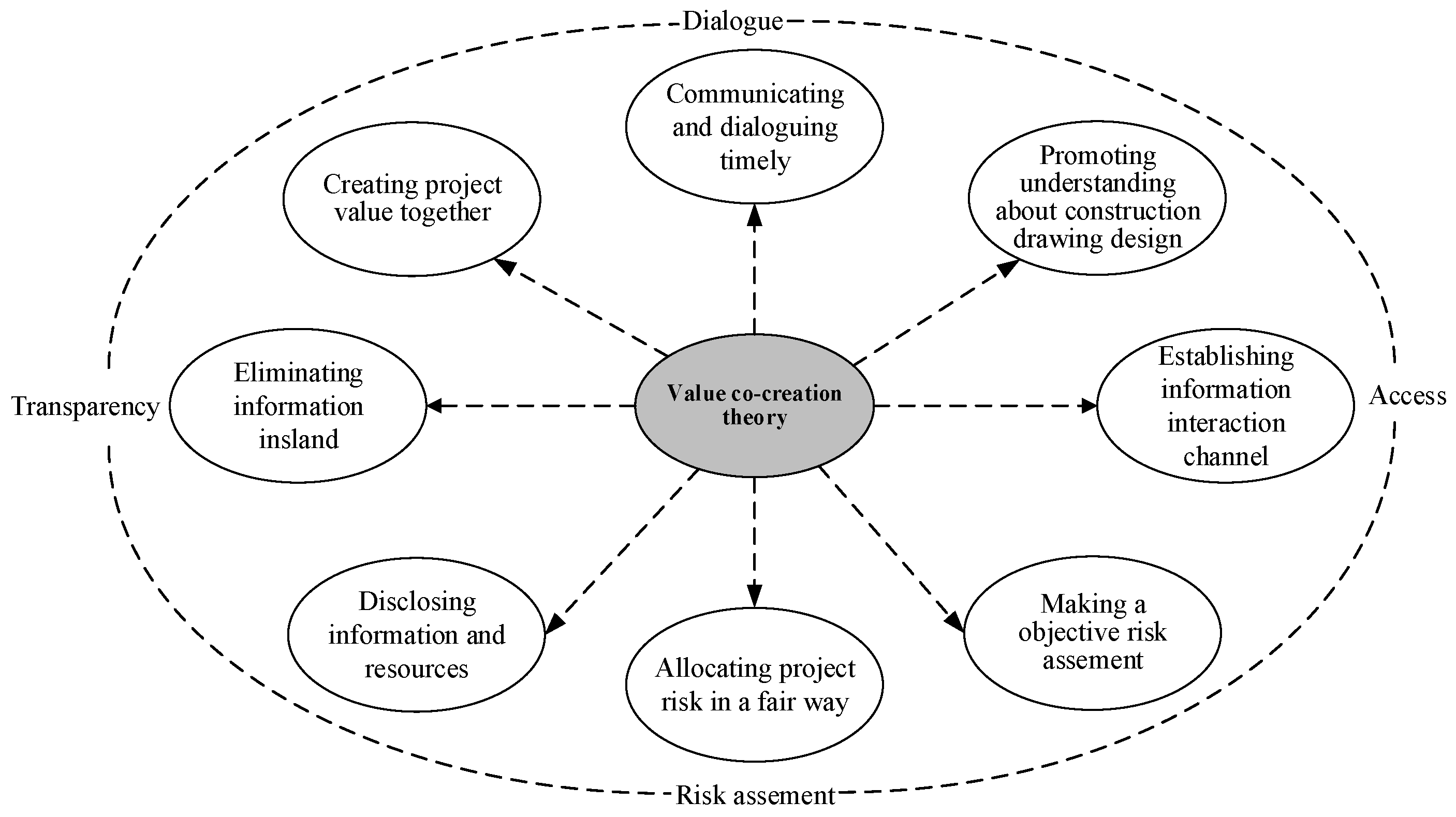

2.3. The DART Model

Based on value co-creation theory, Prahalad and Ramaswamy [

20] and Ramaswamy [

28] proposed the DART model, which consists of dialogue (D), access (A), risk assessment (R), and transparency (T). The combination of these four elements can give full play to the advantages of each participant, better promoting participants’ cooperation and communication and enhancing information exchange and sharing. So, a win–win result among participants can be achieved. The DART model can better fit the cooperative relationships between owners and general contractors of EPC projects in the design stage. For example, in terms of dialogue, owners are typically less involved in specific organization and construction activities [

33]. However, during the design stage, they can still communicate promptly with general contractors to convey construction drawing requirements and provide guidance. Correspondingly, general contractors of EPC projects can also understand owners’ needs more clearly so that the chance of unfavorable situations arising in the construction process can be reduced. In terms of access, owners and general contractors can establish a smooth information interaction channel to form a relatively trustful cooperative environment, which can contribute to the smooth implementation of EPC projects. With regard to risk assessment, in general, EPC project risks are mainly taken by general contractors [

33], e.g., meeting the required performance based on a defined and agreed project schedule [

53]. However, if owners and general contractors can make an objective risk assessment and then allocate project risk in a reasonable and fair way, better cooperation results will be achieved [

54,

55]. As for transparency, owners and general contractors of EPC projects may deliberately create an information silo and resource asymmetry out of their own interests, which may lead to a reduction in their cooperation efficiency [

56]. Under the condition of transparency and openness, both partners can selectively disclose information and resources to each other to create value together. The DART model is highly suitable for solving the two-stage design interest paradox, as shown in

Figure 2.

2.4. The Design Management Model of the “DART-PDCA”

Based on the above analysis, the value co-creation theory and the DART model are very important to solving the problem of the two-stage design interest paradox between owners and general contractors in Chinese EPC projects. In addition, the DART model can promote information and resources sharing and promote cooperation and communication between owners and general contractors. Moreover, it is helpful to build a platform in the interest of mutual benefit in which both owners and general contractors become a “community of shared destiny” during EPC projects.

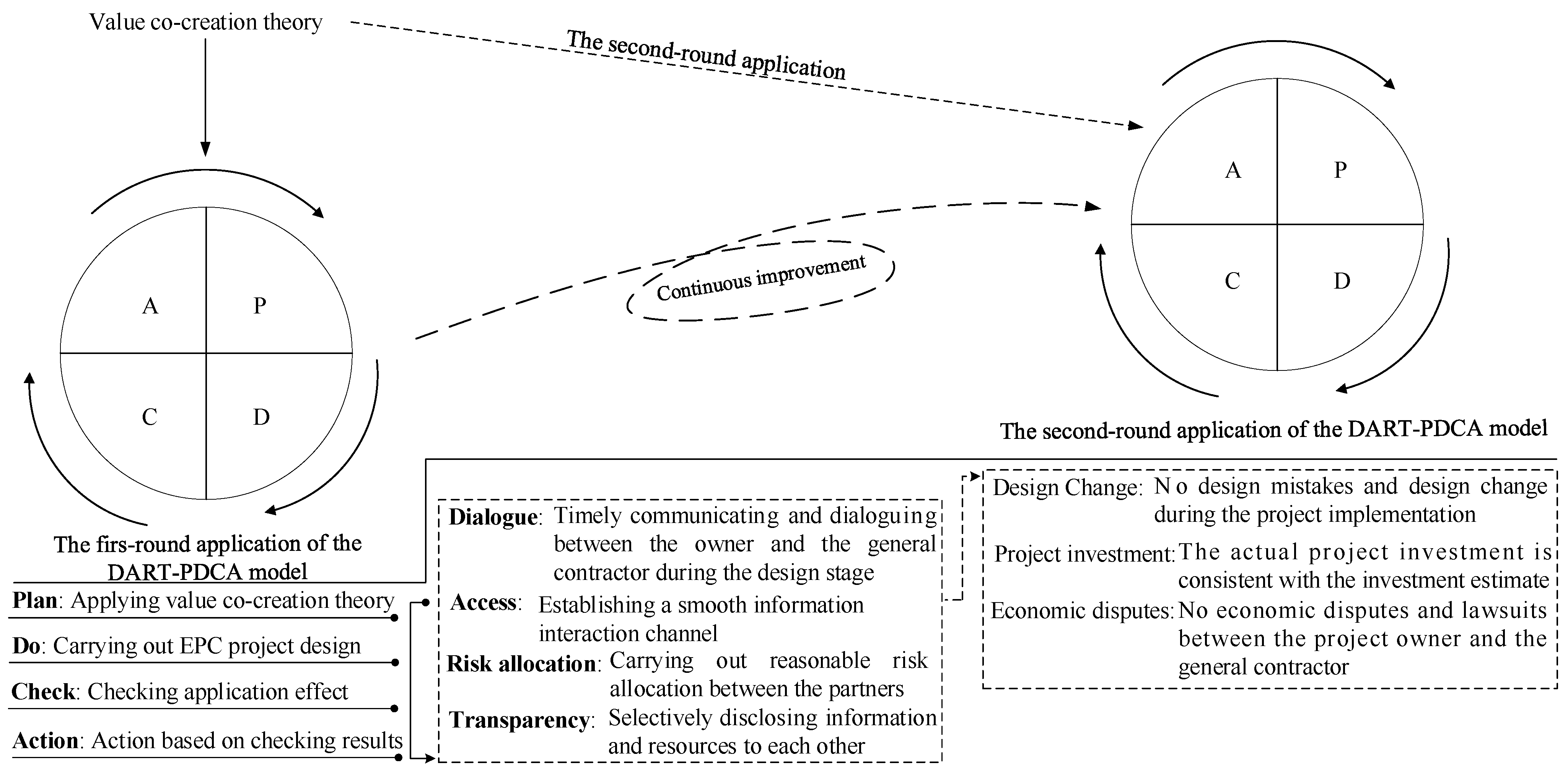

However, solely relying on the DART model cannot perfectly solve the problem of the two-stage design interest paradox under the Chinese context of low social trust [

57], and we cannot expect to solve the problem by applying the DART model just one time. The PDCA cycle, as mentioned previously, has been embraced as an excellent foundation for, and foray into, quality improvement in many fields as it has been used as an efficient tool for continuous quality improvement in many studies [

58,

59,

60]. So, a multi-round PDCA cycle was adopted to strengthen the implementation effect of the DART model. As a result, the “DART-PDCA” design management model is proposed in this research to solve the problem of the two-stage design interest paradox between owners and general contractors in Chinese EPC projects.

4. Manifestation of the “Two-Stage Design Interest Paradox” and the Outcomes in the Case Project by Application the DART-PDCA Model

4.1. Manifestation of the “Two-Stage Design Interest Paradox” of the Chinese EPC Projects

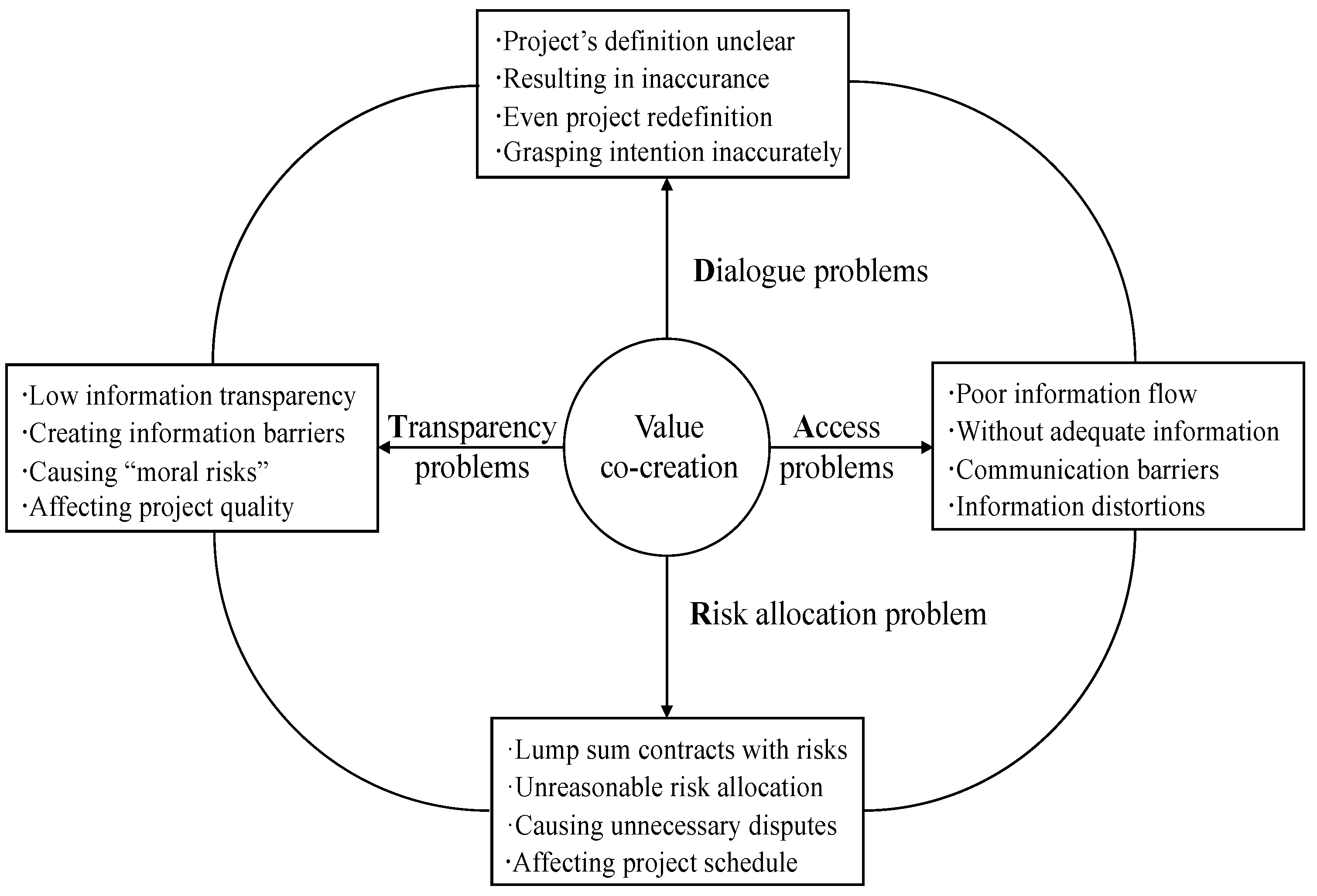

4.1.1. Problems Arising from Lack of Dialogue and Interaction Between the Partners (D)

Most Chinese EPC project definitions are unclear at the contract signing stage. This differs distinctly from DBB projects, where design is largely complete before construction bidding. This inherent ambiguity in EPC often results in reworking or even project redefinition during construction. Crucially, under the EPC model, where the contractor integrates design and construction, the lack of continuous and deep dialogue means the general contractor’s grasp of the owner’s evolving design intention is frequently inaccurate. While owners initially provide concepts and standards, the absence of finalized design drawings (unlike DBB) and the reliance on the contractor to develop detailed designs create a unique vulnerability. Insufficient communication throughout the design development phase, a core EPC responsibility, directly leads to misinterpretations, unnecessary design changes, and compromised project quality and execution.

4.1.2. Problems Caused by Barriers to Access to Information of the Partners (A)

The integrated nature of EPC contracts creates unique information flow challenges. Differences in participation roles lead to distinct information channels and poor information exchange. Specifically within the EPC framework, where the contractor manages the entire process, information critical for owner oversight (e.g., detailed design rationale, real-time procurement choices, and construction methodology nuances) often resides primarily with the general contractor. Although contracts grant owners access rights, the reality in EPC projects is that owner information access is heavily dependent on, and filtered by, the contractor’s voluntary disclosure, unlike segmented contracts where designers or specialized contractors might hold distinct information silos. Formal requests and contractual stipulations often prove inadequate, exacerbated by the contractor’s potential incentive to control information flow impacting their profit within the lump sum contract. This leads to information being “trapped,” hindering effective oversight and collaboration specifically under the single-point responsibility model of EPC.

4.1.3. Problems Arising from Unreasonable Risk Allocation Between the Partners (R)

The fundamental structure of EPC lump sum contracts dictates a unique and heavy risk burden on the general contractor. Compared to DBB or other multi-contract models, where risks like design errors, market price fluctuations, or unforeseen site conditions might be shared or fall to the owner, EPC contracts, by design, transfer the vast majority of economic, technical, management, and significant portions of political, social, and natural risks to the contractor. This is intrinsic to the “single point of responsibility” and fixed-price nature of EPC. Crucially, the bid assumption that contractors have fully accounted for all risks (e.g., material costs and adverse geotechnical conditions) in their lump sum price is a defining and often problematic feature of EPC, not typical of cost-reimbursable or unit-price contracts common elsewhere. This concentrated and often unrealistic risk allocation inherent to the EPC model is a primary driver of disputes during the design stage and project delays.

4.1.4. Problems Arising from Low Information Transparency Between the Partners (T)

Distrust in the Chinese construction industry is amplified within the EPC model due to the contractor’s combined control over design and construction. Participants, particularly general contractors who manage the integrated process, may perceive high information transparency as a threat to their profit margins within the fixed-price contract. This creates a unique incentive within EPC for contractors to deliberately erect information barriers [

73], especially during the critical design management phase where decisions significantly impact downstream costs and profits. While information asymmetry exists in other models, the EPC contractor’s position as the sole source for comprehensive design, procurement, and construction information creates a pronounced risk of moral hazard and adverse selection, specifically against the owner. The owner’s ability to effectively monitor and restrain the contractor is particularly weakened in EPC compared to models where design and construction are separate precisely because the contractor aggregates the information and resources across the entire project lifecycle.

In summary, the poor communication and dialogue (D) between EPC owners and general contractors can make EPC projects definition unclear, and the barriers to access to information make for poor information flow (A). Moreover, owners allocate most of the project risks to general contractors, and unreasonable risk allocation may cause disputes (R). Finally, owners and general contractors are in a state of low information transparency (T), which may lead to the work orientation being prone to deviation. The above problems faced by the design process of EPC projects are mapped out in

Figure 4 using the DART model.

4.2. The Case EPC Project Profile

The Yuzhou High-speed Rail Station Square and Related Infrastructure PPP Project is located in the eastern Chu River area of Yuzhou city, Henan province, China, west of Zhengwan High-speed Railway Yuzhou Station. The project covers an area of 70,500 square meters, with a total investment of USD 7,559,000 (excluding land costs). The main construction content include the high-speed rail station square (with a construction area of 39,005 square meters), the passenger transport complex (including passenger station and passenger distribution centers, with a construction area of 35,750 square meters), and underground space (construction area of 38,905 square meters).

The project adopts the EPC general contracting mode. During the construction period, the owner, Yuzhou Transportation Investment Co., Ltd., is responsible for dealing with administrative approval procedures for the project’s capital construction, compensation for land acquisition, and the relocation for the project’s construction site. The general contractor, a consortium composed of China Railway Siyuan Survey and Design Group Co., Ltd., China Railway No.5 Engineering Group Co., Ltd., and China Railway Siyuan Group Investment Co., Ltd., is responsible for the survey and design, investment and financing, and construction of the project. Since the project adopts a PPP cooperation mode, after completing the project, it shall be owned by the owner or the relevant unit and shall be provided to the general contractor for operation for a reasonable benefit. At the end of the operation period (for 180 months), the general contractor shall hand over the project facilities to the owner or other institutions designated by the government without compensation and in good condition. The project cooperation period is 198 months, including a construction period of 18 months and an operation period of 180 months.

4.3. The Outcomes in the Case Project by Application the DART-PDCA Model

4.3.1. Dialogue

In the case project, a consortium, as the general contractor, needs to complete the project survey and design, conduct project construction, provide continuous and stable operation services, and assume the corresponding responsibilities and risks. The design documents should meet the functional needs of the EPC project itself and accord with Chinese laws and the general contract. So, it is obvious that the general contractor and the owner should build a good dialogue environment to efficiently complete the project design and the follow-up work. First, it is important for project participants to adopt BIM technology in construction project management to provide an efficient dialogue channel. For example, in terms of technical communication, the use of a BIM-based digital and visual dialogue platform can reduce information asymmetry between the partners and break up the information island. By leveraging the platform’s visual information dialogue function and intelligent terminal, it can accelerate the transfer process of related problems among the project participants during project execution.

4.3.2. Access

In the case project, there is “information stickiness” between the owner and the general contractor. To be specific, the design stage of the case project involves a wide range of professions, and the information stickiness is often obvious due to the strong professionalism and technical complexity involved in the design work. The consortium, consisting of design and construction units, shall complete the design, procurement, and construction work of the case project. Thus, the design unit (i.e.,

China Railway Siyuan Survey and Design Group Co., Ltd.) carries out the design of the project, and

China Railway No.5 Engineering Group Co., Ltd., another unit of the consortium, carries out the construction of the case project based on the design drawings provided by the design unit. So, the design unit may cause a lot of information to be stuck due to the lack of information integration and information transmission, thus causing the phenomenon of information stickiness. For the construction unit, this may delay the progress of the project because it cannot receive the design drawings in a timely manner. So, it is beneficial to establish an efficient and smooth information access channel, which permit the owner, the general contractor, and other participants to know more about each other and make information access more convenient. Moreover, information access in the case project can consist of formal and informal channels [

74]. For the owner and the general contractor, they can reduce the information stickiness by establishing a clear division of functions, designing a reasonable formal contract, establishing an incentive mode for information sharing, and establishing an information security control mode.

4.3.3. Risk Allocation

According to the general contract of the case project, a lump sum contract is adopted; that is, the price risk shall be borne by the general contractor. However, to encourage the general contractor to execute the contract well, the owner has implemented incentive measures in the form of engineering change. For example, during the construction period, the owner, the general contractor, and relevant participants have the right to apply for engineering change according to the basic procedures for engineering change in Xuchang city government-invested projects for reasonable purposes such as optimizing design and saving engineering investment. With regard to procurement risks, the contract of the case project stipulates that the owner has the right to inspect and review all materials and equipment purchased by the general contractor. If any materials and equipment are found to have defects or do not meet the Chinese compulsory standards and agreements, the general contractor shall immediately repair the inspected quality defects and bear the relevant expenses and risks arising therefrom. However, to avoid the abuse of the supervision power of the owner, it is also stipulated that if the materials and equipment audited or inspected by the owner meet the Chinese compulsory standards and agreement, the owner shall bear the relevant expenses incurred therefrom. As for the uncertain risks, by signing a framework clause or agreement, the risk allocation focus will be on renegotiation in the construction process, and the performance of the design work improvement strategy set will be improved. Especially for a case project with complex geology and uncertain construction technology, the owner and the general contractor should pay more attention to the adjustment mechanism based on risk re-sharing in the design stage.

4.3.4. Transparency

The difference in the amount of information possessed by the owners and the general contractors often results in “information superiority,” which may adversely affect the smooth execution of EPC projects. For instance, in the bidding stage of EPC projects, owners have a large amount of preliminary information about proposed projects and therefore may hide some unfavorable information (such as the poor hydrological and geological conditions of the project site), which frequently leads to the phenomenon of “moral risks” and thus infringes upon general contractors’ rights and interests. After signing general contracts, general contractors will carry out the project design, procurement, and construction work of these EPC projects, meaning that general contractors have almost all the data and information of these EPC projects, which is an advantageous information position. Therefore, general contractors may act opportunistically, which is bad for owners. The fundamental solution to such problems is to enhance the mutual trust between owners and general contractors [

75], such as advocating for information exchange at the beginning of projects [

76] so as to overcome and eliminate self-serving behaviors on the part of the information-advantaged side and finally realize value co-creation between owners and general contractors under the condition of information transparency.

In the case project, both the owner and the general contractor agreed in the general contract that information technology should be used to disclose project information in a timely manner. For example, the general contract stipulates that the owner shall upload the contract and relevant project files to the project management database of the Project information base of the China Public Private Partnerships Center, which is the regulator of PPP projects in China. In addition, both the owner and the general contractor should upload relevant information to the Project information base in a timely manner along with the progress of the case project. This stipulation aims to safeguard public interests and promote administration in accordance with Chinese laws and the general contract and improve project transparency.

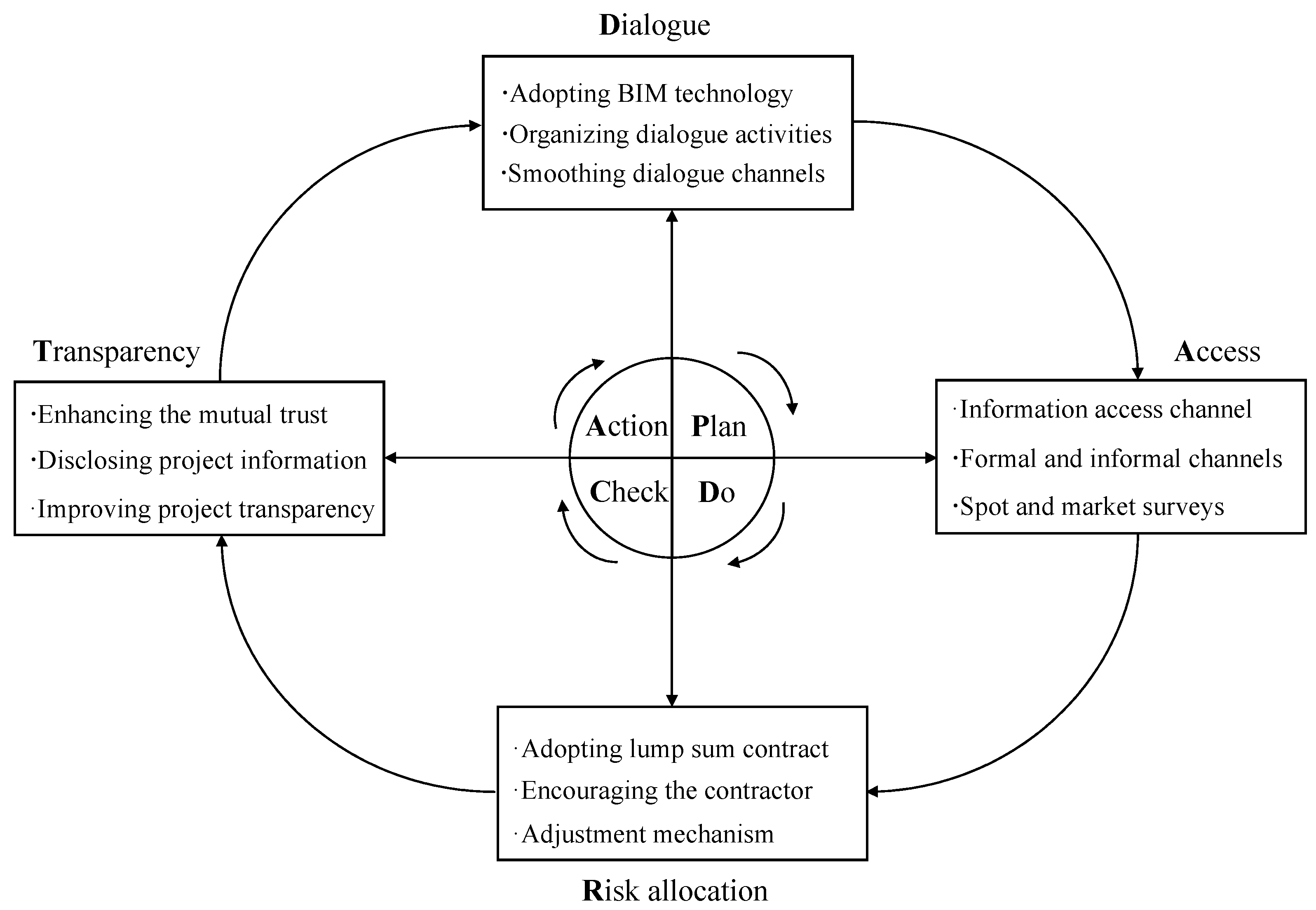

4.3.5. The “DART-PDCA” Design Management Model

In the case project, the PDCA cycle could be used to improve the application effect of the DART model and value co-creation theory. To be specific, when applying the PDCA cycle, owners and general contractors should first put forward the plan (plan, i.e., P) to apply the DART model and value co-creation theory to the design work of the case project together. Second, under the guidance of the DART model and the value co-creation theory, the EPC project design should be carried out, and the owner and the general contractor are guided to implement value co-creation such as through design optimization and function improvement (do, i.e., D). Then, the design work should be observed to test the optimization of the design work, the value-added to the project by the DART model, and the value co-creation theory (check, i.e., C). Finally, based on the result, the owner and the general contractor should act circularly to continuously improve design management performance (A). The above solutions provided for the case project are shown in

Figure 5.

It is worth noting that the DART-PDCA model can be applied many times, and that it is a cyclical upward process. So, the application of the DART model in the first design management stage of the case project can provide the basis for the next design management stage. Correspondingly, the second design management stage of the case project can serve to constantly optimize the results of the first design management stage. So, the DART-PDCA model for the case project drives continuous design management improvement. The “DART-PDCA” design management model is shown in

Figure 6.

4.4. The Application Effect of the “DART-PDCA” Design Management Model

It is worth noting that the DART-PDCA model proposed in the present research is an effective method in improving Chinese EPC project design management performance. According to the final acceptance report of Yuzhou High-speed Rail Station Square and Related Infrastructure PPP Project, there are no design mistakes or design changes during the project implementation. Moreover, the design is effective in controlling project investment, and the actual project investment is consistent with the investment estimate. There are no economic disputes and lawsuits between the project owner and the general contractor in Yuzhou High-speed Rail Station Square and Related Infrastructure PPP Project. Moreover, the Construction project (Phase I) of the Hangzhou Branch of the China National Archives of Publications and Culture and the EPC General Contracting Project of Equestrian Project (Main Stadium) of Hangzhou Asian Games, which are mentioned as examples earlier in this research, also demonstrated good design management performance because their owners and contractors used design management ideas that are similar to the DART-PDCA model proposed in the present research.

4.5. Extended Case for Applying the DART-PDCA Model

4.5.1. Project Overview

(1) Project title: Yuhang District Asian Games Venue Renovation EPC Project.

(2) EPC contract scope: Comprehensive design services (including construction drawings and specialized design); pre-approval, completion acceptance, and filing; procurement, installation, and commissioning of all materials and equipment; construction, inspection, handover, filing, and warranty services.

(3) Investment scale and construction content: Total investment: CNY 950 million. Construction scope: Renovation of stadium; new construction of gymnasium, comprehensive training hall, covered sports ground, underground parking lot, and municipal ancillary facilities. Total site area: 89,414.41 m2. Total floor area: 95,644.44 m2.

(4) Core challenge: Project duration (including construction drawing design and project construction) was compressed from a baseline of 1080 days to 780 days, thus placing stringent demands on the precision and accuracy of construction drawing design for the project.

4.5.2. Empirical Application of DART-PDCA Model

Through analyzing specialized works on hands-on experience in the case project design management process and semi-structured interviews with general contractor personnel, the case project’s implementation measures for applying the design management model were found to include the following:

(1) Dialogue mechanism: A “design-led” collaborative dialogue framework was established to achieve efficient integration of multiple stakeholders. Moreover, construction management teams engaged proactively in the design phase. Design units systematically incorporated construction feedback to enhance operability, transforming external control into endogenous collaboration and establishing an iterative design–construction optimization mechanism.

(2) Information access: Full-process supervision and information transparency were implemented for critical stages—including technical preparation, briefing, material inspection, construction operations, and concealed works—in compliance with technical specifications and management systems.

(3) Risk allocation: The project department organized joint drawing reviews and optimization sessions with owners, designers, and contractors. More than 1000 review comments were proposed, significantly mitigating cost over-runs and schedule delays caused by design conflicts, rework modifications, and construction errors.

(4) Transparency: Lightweight 3D simulations using Navisworks platform precisely visualized complex nodal details and construction techniques. This enhanced the clarity of technical briefings and facilitated stakeholders’ understanding of critical processes.

4.5.3. Implementation Outcomes of the Design Management Model

By applying the DART-PDCA model, the case project simultaneously achieved schedule compression targets. Moreover, through effective collaboration between design and construction teams, the design plan was improved and optimized, thereby reducing investment in the flood lighting system alone by approximately CNY 15 million. By incorporating recommendations from the construction management team, the design team optimized the excavation support scheme while ensuring structural integrity and safety as well. This involved replacing cement-mixed retaining piles with precast concrete (PC) piles, achieving both project time savings and a cost reduction of approximately CNY 20 million.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Findings

There is a two-stage design in Chinese EPC projects and can seriously and negatively affect design management performance and project performance in terms of cost, quality, and schedule. However, the two-stage design has not yet received sufficient attention by scholars. This research aims to address this research gap. Employing case study methodology, this research operationalizes value co-creation theory and PDCA cycles into the “DART-PDCA” design management model, with principal findings being (1) that the two-stage design interest paradox negatively impacts design management quality in China’s low-trust environment; and (2) that the “DART-PDCA” design management model effectively resolves this paradox, leading to demonstrable improvements in design management quality, efficiency, and stakeholder alignment.

6.2. Contributions to the Body of Knowledge

The design phase has the highest level of influence on EPC projects as many key decisions will be made during the pre-project planning and design phases. These decisions will significantly affect design performance and project performance in terms of cost, quality, and schedule. So, it is critical to strengthen design management, especially in China, whose design management is different from other countries in the world. There is a design interest paradox in Chinese EPC projects, and this phenomenon has not yet received sufficient attention. This research makes important primary contributions to the body of knowledge, with both theoretical and practical prospects.

First, this study provides the first conceptual definition of the “two-stage design interest paradox,” a core phenomenon prevalent in Chinese EPC project practice that has long been neglected by theoretical research. This work thus addresses a significant gap in the existing body of knowledge.

Second, this study develops an integrative theoretical model for the EPC project design management. Specifically, it innovatively constructs the “DART-PDCA” design management model tailored to the Chinese context. This model effectively integrates interdisciplinary knowledge domains encompassing owner–general contractor relationships, design management, and EPC project management. It systematically elucidates, from a macro-level perspective, the unique multi-organizational dynamic collaboration mechanisms inherent in Chinese EPC projects.

Finally, this study validates model efficacy through case-based research and provides actionable practical guidance. Rigorously adhering to the case study theory-building research paradigm, it conducts an in-depth analysis of EPC project design management practices within the Chinese construction industry context. This analysis empirically validates the effectiveness of the “DART-PDCA” design management model in resolving the two-stage design interest paradox. Consequently, it offers actionable, practical guidance for project owners and general contractors to eliminate this paradox and enhance design management performance.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

(1) The generalizability of this study needs to be further enhanced. The case study is mainly based on representative EPC projects concerning a high-speed railway station square and stadium project in China, which are not common in practice. In addition, the level of trust in Chinese society is known to be low [

14], so the findings based on a case project such as the one analyzed in this research should be cautiously generalized to contexts with significantly different trust dynamics. Subsequent studies can be integrated and validated with cases from other countries and religions to fully address the two-stage design interest paradox of EPC projects.

(2) The factors involved in this research should also be expanded. As is known to all, the design management of EPC projects involves the engineering of a complex system [

83], which is a difficult task. It not only involves a wide range of professional aspects but also involves multiple partners such as EPC project owners, design units, and general contractors. The following questions are worthy of further study: What roles do all partners play in design management? How do we build an efficient dialogue pathway? How do we improve the design management method to better serve the owners of EPC projects?

(3) The conclusions of this case study need to be supplemented by an empirical analysis approach. Based on the two-stage design interest paradox in Chinese EPC projects, this study adopts a case study research approach to exploratorily construct the DART-PDCA model and offers preliminarily reports on its application effects across a range of project practices. Given the exploratory nature of this research, the case analysis method is methodologically appropriate at the current stage. To enhance the credibility and generalizability of this research, future research can consider incorporating quantitative methods, such as statistical testing and comparative analysis, across a broader project sample.