From Vacancy to Vitality: NIMBY Effects, Life Satisfaction, and Scenario-Based Design in China’s Repurposed Residential Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

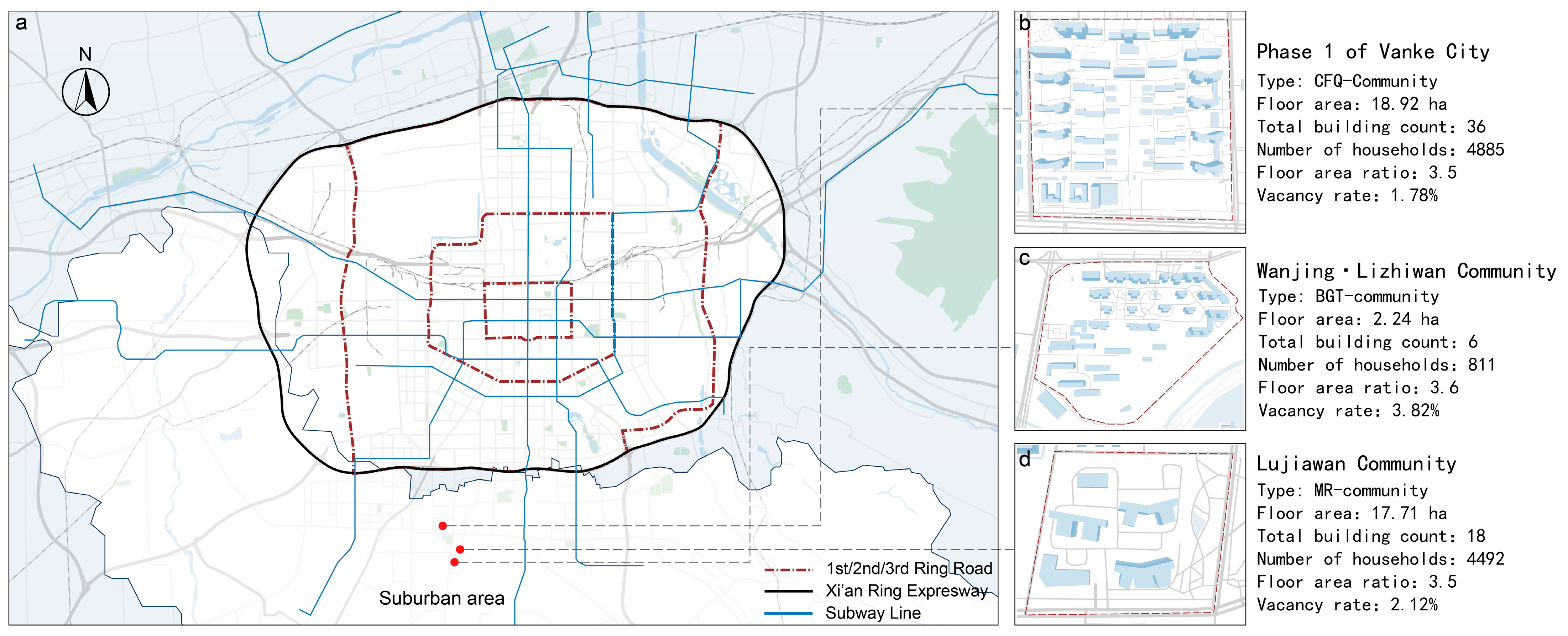

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Indicators

2.2.2. Survey Method and Sample Size

2.2.3. Sampling Characteristics in the Three Types of Communities

2.3. Ordered Logistic Model

3. Results

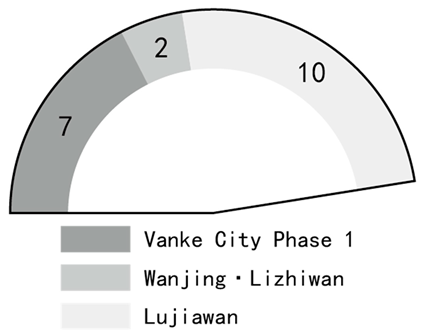

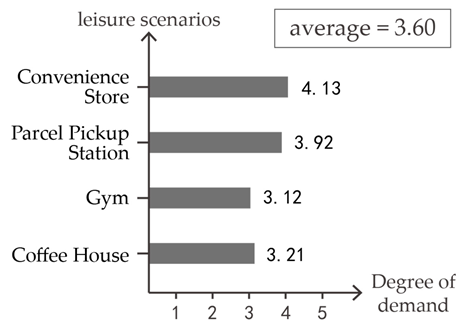

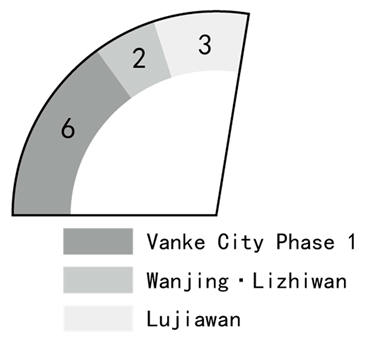

3.1. Usage Characteristics of Residential Space After the Facilities Were Integrated

3.2. Satisfaction and NIMBY in Housing Functional Transformation

3.2.1. Life Satisfaction of Community Residents

3.2.2. NIMBY and Housing Functional Transformation in Community

3.3. Ordered Logistic Model Results

4. Dicussion

4.1. A Dynamic Comparison with Other Cities

4.2. Measures for Embedding Service Facilities in Residential Spaces

4.2.1. Layered and Categorized Facility Allocation

4.2.2. Mitigating the NIMBY Effect

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Dependent Variable Threshold | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Noise pollution | 0.65 | 1.54 |

| Garbage pollution | 0.61 | 1.64 |

| Safety risks | 0.47 | 2.15 |

| Fire safety hazards | 0.71 | 1.41 |

| Neighborhood relationships | 0.74 | 1.35 |

| Response to residents’ issues | 0.73 | 1.37 |

| Information accessibility | 0.77 | 1.30 |

| Sense of respect | 0.72 | 1.39 |

| Facilities accessibility | 0.79 | 1.27 |

| Public space encroachment | 0.68 | 1.47 |

Appendix A.2

| Fit the Indicator | Leisure | Health | Education | Society | Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df = 10) | 125.6 *** | 158.3 *** | 98.7 *** | 142.8 *** | 115.4 *** |

| −2 log likelihood | 852.6 | 798.3 | 915.2 | 810.5 | 882.1 |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.27 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.31 |

| McFadden R2 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| AIC | 880.6 | 826.3 | 943.2 | 838.5 | 910.1 |

| BIC | 948.2 | 893.9 | 1010.8 | 906.1 | 977.7 |

| Parallel line test χ2 | 15.2 | 17.8 | 12.5 | 16.4 | 14.1 |

| Parallel line test p-value | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

References

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook-2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Yuan, F.; Ye, Z. Evaluating China’s urbanization trajectory: An overextension or still in progress? Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1465864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiong, W. China’s Real Estate Market. In The Handbook of China’s Financial System; Princeton University Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beike Research Institute. Survey Report on Housing Vacancy Rates in Major Chinese Cities. 2022. Available online: https://kandian.ke.com/detail/MjY3MjM4NzI=.html?beikefrom=pc_kd_index (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Zhang, E.; Hou, J.; Long, Y. The form of China’s urban commercial expansion in the digital era. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J. Analysis and optimization of 15-minute community life circle based on supply and demand matching: A case study of Shanghai. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. Design strategies for aging adaptation design of public spaces under the community elderly care model. Salud Cienc. Tecnol.-Ser. Conf. 2024, 3, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchaniya, R.J.; Černeckienė, J.; Gudumasu, N.S.; Kundziņa, A. Adaptive Property Reuse for Social Housing: Benefits, Challenges, and Best Practices. Balt. J. Real Estate Econ. Constr. Manag. 2025, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Cui, J.; Lin, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Beijing Symbiotic Courtyard Model’s Post Evaluation from the Perspective of Stock Renewal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuscan, S.; Muntean, R. Building Conversion: Enhancing Sustainability Through Multifunctionality and Movable Interior Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, S.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Circular Economy and Social Circularity. Diffuse Social Housing and Adaptive Reuse of Real Estate in Internal Areas. In Urban Regeneration Through Valuation Systems for Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T. Tianzifang: A Case Study of a Creative District in Shanghai; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Jhun, K.K.; Vijayan, V.T. Reflection on the Value Characteristics and Protection Modes of Shanghai Shikumen Lilong. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Urban Engineering and Management Science, Tianjin, China, 2–4 August 2024; EDP Sciences: London, UK, 2024; Volume 565, p. 03023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Zhong, X. Commercial development from below: The resilience of local shops in Shanghai. In Global Cities, Local Streets; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Hu, X.; Lin, H.; Xie, X.; Liu, X. Mismatch between infrastructure supply and demand within a 15-minute living circle evaluation in Fuzhou, China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L. Influencing factors and realization paths for smart community construction in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; He, S.; Liu, Y.; Rui, G.; Wang, S. Conflict-mediation, consensus-building, and co-production: Three models of co-governance in China’s neighborhood regeneration. Trans. Plan. Urban Res. 2024, 3, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Lei, X. New trends in population aging and challenges for China’s sustainable development. China Econ. J. 2020, 13, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, X. Exploration on ways of research and construction of chinese child-friendly city—A case study of changsha. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. The new paradigm of future cities? Facilitating dialogues between the 15-minute city and the 15-minute life circle in China based on a bibliometric analysis. Trans. Plan. Urban Res. 2024, 3, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Tao, L.; Lian, Y.; Huang, W. Measuring spatial accessibility of urban medical facilities: A case study in Changning district of Shanghai in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Zhu, W.; Wu, D.; Li, H. Parental satisfaction with early childhood education services in rural China: A national survey. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 115, 105100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y. From service capacity to spatial equity: Exploring a multi-stage decision-making approach for optimizing elderly-care facility distribution in the city centre of Tianjin, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, R.; Liang, X.; Shen, X.; Chen, J.; Lin, X. Smart community: An internet of things application. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2011, 49, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, J.A. Urbanism and community sentiment: Extending Wirth’s model. Soc. Sci. Q. 1979, 60, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.K.; Kang, H.G.; Park, S.B. A study on the residents’ evaluation for the component of high-Rise and high-density apartment community. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2013, 29, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Lee, T. A Study on Building Sustainable Communities in High-rise and High-density Apartments. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Sakieh, Y.; Khammar, S. Measuring satisfaction: Analyzing the relationships between sociocultural variables and functionality of urban recreational parks. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 2577–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schively, C. Understanding the NIMBY and LULU phenomena: Reassessing our knowledge base and informing future research. J. Plan. Lit. 2007, 21, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, E.; Masso, D.A.; Castrechini, A.; Bonet, M.R.; Vidal, T. Psychological parameters to understand and manage the NIMBY effect. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2006, 56, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C.; Xia, B.; Ke, Y.; Skitmore, M. Social acceptance of NIMBY facilities: A comparative study between public acceptance and the social license to operate analytical frameworks. Land Use Policy 2023, 124, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, J. NIMBY effects of urban service facilities in Taipei metropolitan living areas. City Plan. 1996, 23, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Palazón-Bru, A. Multivariate Ordered Logistic Regression Models: Dealing with the Model-Building Strategy. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W. An Exploration of Needs within Maslow’s Hierarchy of Motivation. Adv. Soc. Behav. Res. 2024, 14, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Urban Management and Law Enforcement Bureau. Provisions of Shanghai Municipality on Residential Property Management. 2023. Available online: https://cgzf.sh.gov.cn/channel_89/20241122/c312ef086ace49b68918273fed5bc929.html (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Shanghai Lunicipal Tax Service, State Taxation Administration. The First Research Group of Shanghai Tax Service participated in the “Coordination Meeting on Issues Related to the Construction and Development of Tianzifang as a Shanghai-Style Cultural Brand”. 2018. Available online: https://shanghai.chinatax.gov.cn/xwdt/ztzl/zhl/ddyzl/dydt/201810/t442282.html (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Akristiniy, V.A.; Boriskina, Y.I. Vertical cities-the new form of high-rise construction evolution. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 33, 01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradaschia, M. MVRDV four projects. IL Progett. 2015, 41, 14–25. Available online: https://arts.units.it/bitstream/11368/2853417/1/41_MVRDV_MB.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Glass, M.R.; Salvador, A.E. Remaking Singapore’s heartland: Sustaining public housing through home and neighbourhood upgrade programmes. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okresek-Oshima, T.; Baldauf, T.; Okresek, M.T.; Halbartschlager, R. How to Meet the City–Urban Spaces for Friendly Encounters. In Proceedings of the REAL CORP 2019, 24th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information Society, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2–4 April 2019; Available online: https://repository.corp.at/524/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Tang, L.; Dai, C. Research on the intergenerational integration model of community service facilities. Archit. Cult. 2024, 11, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Research on Risk Assessment and Problem Management of Community Noise Nuisance in Beijing Based on Bayesian Network; Beijing Jiaotong University: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Research on Urban Community Public Safety Governance Countermeasures from the Perspective of Resilience. China Emerg. Manag. Sci. 2025, 07, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Research on Multi-Subject Collaborative Governance of Urban Community Domestic Waste Classification; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | NIMBY Effect Content | NIMBY Effect Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Comfort | Noise pollution | Noise pollution |

| Garbage pollution | Garbage pollution | |

| Security | Risk of personal safety and property damage | Safety risks |

| Fire safety hazards | Fire safety hazards | |

| Belonging | Neighborhood relationships | Neighborhood relationships |

| Timely responsiveness of the property to residents’ questions | Response to residents’ issues | |

| Information is available on important matters for the community | Information accessibility | |

| Respect from business and industry | Sense of respect | |

| Spatial fairness | Accessibility to various facilities | Facilities accessibility |

| Public space encroachment | Public space encroachment |

| Respondent Demographics | CFQ-Community (Vanke City Phase 1 Community) | BGT-Community (Wanjing Lizhiwan Community) | MR-Community (Lujiawan Community) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 90 | 94 | 92 |

| Gender | Male (40.00%) | Male (40.43%) | Male (40.23%) |

| Female (60.00%) | Female (59.57%) | Female (59.78%) | |

| Age | <20 (8.89%) | <20 (11.70%) | <20 (9.78%) |

| 20–35 (23.33%) | 20–35 (19.15%) | 20–35 (26.09%) | |

| 36–50 (62.22%) | 36–50 (55.32%) | 36–50 (46.74%) | |

| >50 (5.56%) | >50(13.83%) | >50 (17.39%) | |

| Family structure | Nuclear family (60.00%) | Nuclear family (53.19%) | Nuclear family (50.00%) |

| Single-person (25.56%) | Single-person (11.70%) | Single-person (7.61%) | |

| Extended family (14.44%) | Extended family (35.11%) | Extended family (42.39%) | |

| Income/year (thousand CNY) | <50 (3.33%) | <50 (11.93%) | <50 (16.78%) |

| 50–100 (18.56%) | 50–100 (34.67%) | 50–100 (45.32%) | |

| 100–200 (54.22%) | 100–200 (42.34%) | 100–200 (31.73%) | |

| >200 (23.89%) | 200 (11.06%) | >200 (6.17%) |

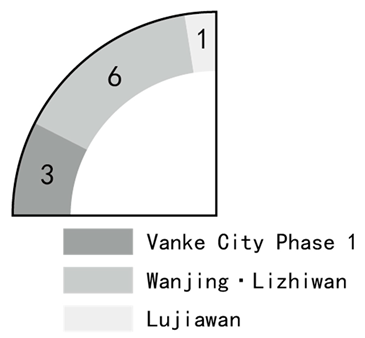

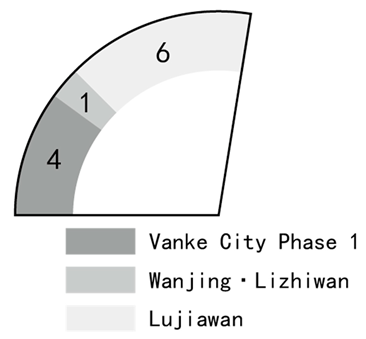

| Residential Functional Conversion | CFQ-Community (Vanke City Phase 1 Community) | BGT-Community (Wanjing Lizhiwan Community) | MR-Community (Lujiawan Community) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Residential functional conversion | 24 | 13 | 22 |

| Percentage of Residential functional conversion | 0.5% | 0.2% | 1.3% |

| Distribution of Residential functional conversion | Distributed across all floors | Distributed from the lower to middle floors | Located on lower floors |

| Primary scenarios formed | Leisure | Education | Leisure and society |

| Scenarios | Content | Picture | Frequency of Use | Quantity (Unit) | Degree of Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure | Convenience Store Parcel pickup station Gym Coffee house |  | 3–5 times/week |  |  |

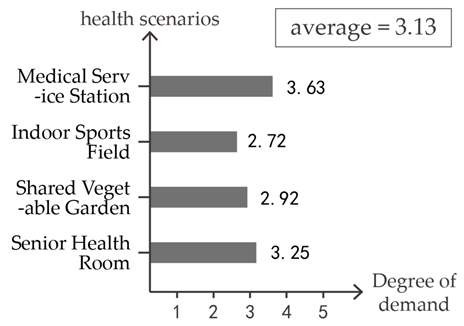

| Health | Medical service station Indoor sports field Shared vegetable garden Senior health room |  | 2 times/week |  |  |

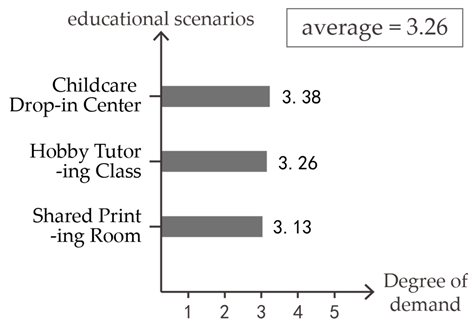

| Education | Childcare drop-in center Hobby tutoring class Shared printing room |  | 2 times/week |  |  |

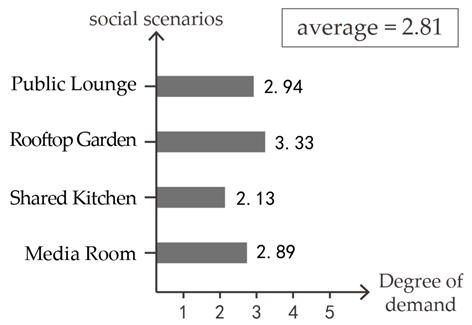

| Society | Public lounge Rooftop garden Shared kitchen Media room |  | 3 times/week |  |  |

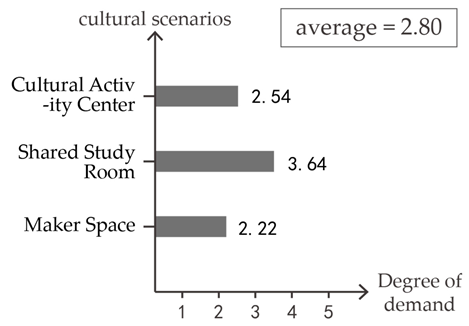

| Culture | Cultural activity center Shared study room Maker space |  | 1 times/week |  |  |

| Type of Housing Functional Transformation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure | Health | Education | Society | Culture | |

| Male | 3.40 (1.24) | 2.96 (0.97) | 3.14 (0.79) | 2.43 (1.02) | 1.76 (1.12) |

| Female | 3.28 (0.86) | 2.87 (0.93) | 3.17 (0.96) | 2.32 (1.09) | 1.69 (0.75) |

| Under 20 years old | 3.47 (0.62) | 3.24 (0.51) | 2.98 (1.07) | 3.58 (1.15) | 2.17 (1.51) |

| Aged 20–35 years old | 3.63 (0.43) | 3.12 (0.68) | 3.07 (1.01) | 3.73 (0.57) | 1.95 (0.65) |

| Aged 36–50 years old | 3.75 (0.78) | 2.87 (0.56) | 3.16 (1.13) | 3.56 (0.69) | 1.76 (1.23) |

| Over 50 years old | 3.66 (0.27) | 2.74 (0.53) | 3.25 (1.37) | 3.47 (1.56) | 2.31 (0.98) |

| Nuclear family | 3.18 (1.21) | 2.06 (0.97) | 3.08 (1.53) | 2.44 (0.67) | 1.63 (1.79) |

| Single-person | 3.24 (0.82) | 2.48 (0.34) | 3.25 (1.42) | 2.04 (1.24) | 2.15 (1.32) |

| Extended family | 3.52 (0.47) | 2.11 (0.69) | 3.21 (1.37) | 2.53 (0.46) | 1.94 (1.13) |

| Income blow 50 1 | 3.74 (0.37) | 2.85 (0.56) | 3.22 (0.48) | 2.88 (0.79) | 2.27 (0.58) |

| Income from 50 to 100 1 | 3.65 (0.21) | 2.62 (0.72) | 3.13 (0.88) | 2.54 (0.62) | 1.95 (1.19) |

| Income from 100 to 200 1 | 3.62 (0.21) | 2.49 (0.67) | 3.32 (1.03) | 2.56 (0.40) | 2.09 (0.85) |

| Income over 2001 | 3.02 (0.76) | 2.61 (0.59) | 3.06 (0.59) | 2.72 (0.92) | 2.06 (1.08) |

| Total sample | 3.60 (1.42) | 2.37 (1.53) | 3.16 (0.83) | 2.40 (1.11) | 1.90 (0.79) |

| NIMBY Effect Index | Leisure | Health | Education | Society | Culture | Evaluate Scores | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise pollution | 2.57 | 3.12 | 2.64 | 3.22 | 2.37 | 2.78 | ① |

| Garbage pollution | 4.25 | 2.98 | 4.37 | 4.28 | 4.36 | 4.05 | ⑩ |

| Safety risks | 3.92 | 3.32 | 2.97 | 3.58 | 3.66 | 3.49 | ⑥ |

| Fire safety hazards | 3.28 | 3.15 | 3.11 | 3.45 | 3.02 | 3.20 | ② |

| Neighborhood relationships | 4.03 | 3.19 | 3.35 | 4.23 | 3.14 | 3.59 | ⑦ |

| Response to residents’ issues | 3.41 | 3.83 | 4.06 | 2.79 | 2.95 | 3.41 | ⑤ |

| Information accessibility | 3.29 | 4.27 | 4.13 | 3.57 | 3.73 | 3.80 | ⑧ |

| Sense of respect | 4.14 | 3.98 | 4.21 | 3.02 | 4.28 | 3.93 | ⑨ |

| Facilities accessibility | 3.39 | 3.30 | 3.22 | 3.18 | 3.26 | 3.27 | ④ |

| Public space encroachment | 3.27 | 3.56 | 2.84 | 3.23 | 3.44 | 3.27 | ③ |

| NIMBY index | 10.91 | 14.63 | 23.18 | 61.36 | 41.52 |

| Leisure | Health | Education | Society | Culture | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable threshold | Beta | OR | Beta | OR | Beta | OR | Beta | OR | Beta | OR |

| Satisfaction ≤ 1 | −2.50 *** | 0.08 | −3.10 *** | 0.05 | 0.38 *** | 0.06 | 0.42 *** | 0.04 | 0.37 *** | 0.07 |

| Satisfaction ≤ 2 | −1.20 *** | 0.30 | −1.60 *** | 0.20 | 0.30 *** | 0.27 | 0.33 *** | 0.22 | 0.29 *** | 0.33 |

| Satisfaction ≤ 3 | 0.80 ** | 2.23 | 0.50 | 1.65 | 0.26 * | 1.82 | 0.28 | 1.49 | 0.28 ** | 2.01 |

| Satisfaction ≤ 4 | 2.50 *** | 12.18 | 2.20 *** | 9.03 | 0.32 *** | 8.17 | 0.36 *** | 9.97 | 0.31 *** | 7.39 |

| Argument | ||||||||||

| Noise pollution | −0.82 *** | 0.44 | −0.25 | 0.78 | −0.58 ** | 0.56 | −0.20 | 0.82 | −0.15 | 0.86 |

| Garbage pollution | −0.41 ** | 0.66 | −1.05 *** | 0.35 | −0.20 | 0.82 | −0.35 * | 0.70 | −0.50 ** | 0.61 |

| Safety risks | −0.30 * | 0.74 | −0.49 ** | 0.63 | −0.35 ** | 0.71 | −0.38 ** | 0.68 | −0.13 | 0.84 |

| Fire safety hazards | −0.20 * | 0.82 | −0.90 *** | 0.41 | −0.15 | 0.86 | −0.18 | 0.84 | −0.10 | 0.90 |

| Neighborhood relationships | 0.65 *** | 1.92 | 0.40 ** | 1.49 | 0.50 ** | 1.65 | 1.35 *** | 3.86 | 0.55 ** | 1.73 |

| Response to residents’ issues | 0.35 ** | 1.42 | 0.73 *** | 2.08 | 0.30 * | 1.35 | 0.54 ** | 1.72 | 0.40 ** | 1.49 |

| Information accessibility | 0.28 * | 1.32 | 0.25 * | 1.28 | 0.60 ** | 1.82 | 0.30 * | 1.35 | 0.85 *** | 2.34 |

| Sense of respect | 0.40 ** | 1.49 | 0.35 * | 1.42 | 0.92 *** | 2.51 | 0.45 ** | 1.57 | 0.78 *** | 2.18 |

| Facilities accessibility | 1.20 *** | 3.32 | 0.45 ** | 1.57 | 0.35 * | 1.42 | 0.25 * | 1.28 | 0.62 ** | 1.86 |

| Public space encroachment | −0.75 *** | 0.47 | −0.30 * | 0.74 | −0.25 * | 0.78 | −0.77 *** | 0.46 | −0.30 * | 0.74 |

| χ2 (df = 10) | 125.6 *** | 158.3 *** | 98.7 *** | 142.8 *** | 115.4 *** | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.31 | |||||

| Test of parallel lines | p = 0.12 | p = 0.09 | p = 0.21 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.15 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhai, B. From Vacancy to Vitality: NIMBY Effects, Life Satisfaction, and Scenario-Based Design in China’s Repurposed Residential Spaces. Buildings 2025, 15, 2953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162953

Wu Y, Wang S, Zhai B. From Vacancy to Vitality: NIMBY Effects, Life Satisfaction, and Scenario-Based Design in China’s Repurposed Residential Spaces. Buildings. 2025; 15(16):2953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162953

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yuqiao, Shan Wang, and Baoxin Zhai. 2025. "From Vacancy to Vitality: NIMBY Effects, Life Satisfaction, and Scenario-Based Design in China’s Repurposed Residential Spaces" Buildings 15, no. 16: 2953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162953

APA StyleWu, Y., Wang, S., & Zhai, B. (2025). From Vacancy to Vitality: NIMBY Effects, Life Satisfaction, and Scenario-Based Design in China’s Repurposed Residential Spaces. Buildings, 15(16), 2953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162953