1. Introduction

The rapid growth of the global population has led to the expansion of the built environment and an increase in population density within urban areas [

1,

2]. According to data from the World Bank [

3], more than half of the global population, approximately 4.4 billion people, currently live in cities. Projections for 2050 indicate that this trend will continue, and it is expected that seven out of ten people will live in urban areas. As a result, the global urbanization rate is expected to reach 68% [

4]. This increase in density has gradually decreased human interactions with nature, which have historically been a key part of life, leading to disconnection from natural environments in some regions [

5,

6].

The decreasing interaction between humans and nature, mainly caused by the spread of the built environment, significantly influences how people experience space and is vital for their cognitive and physical development [

7,

8,

9]. The nexus between architectural environments and human well-being has become an increasingly important area of research across many fields, including education, health sciences, theology, environmental psychology, and architecture. In response, recent years have witnessed the emergence of diverse architectural design paradigms that prioritize sustainability, technology, and user-centered experiences. Among these emerging paradigms, sustainable architecture, parametric and digital design, smart and technology-integrated systems, inclusive and human-centered approaches, adaptive reuse, and biophilic design are prominent frameworks [

10]. Biophilic design, in particular, has gained importance as a strategy to reconnect people with nature by incorporating natural elements into architectural environments [

11,

12]. This approach has become increasingly essential in mitigating the negative impacts of urbanization on individual well-being, encompassing physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects, and in fostering restorative environments through stronger connections between constructed forms and the natural world [

13,

14,

15].

The concept of biophilic design is based on the term “biophilia” (love of life), which was first introduced by Erich Fromm in 1964 [

12]. This idea was later expanded by naturalist and biologist Edward O. Wilson, who published the Biophilia Hypothesis in 1984, proposing that humans have an innate connection to nature and living systems [

16]. In his later work, Wilson stressed that this natural bond requires meaningful interactions with the environment, showing that humans are evolutionarily inclined to seek closeness to natural elements [

10,

17,

18]. The proximity between built environments and natural elements is vital for supporting psychological, emotional, and physiological well-being [

19,

20,

21]. This notion has significantly influenced architects and urban planners who aim to design environments that improve well-being and facilitate psychological restoration, particularly in urban areas where access to nature is limited [

21,

22,

23].

Biophilic design, which emphasizes the natural human connection to nature and the importance of contact with nature for human well-being, aims to strengthen human–nature bonds through architectural planning and design strategies [

23,

24,

25]. However, this approach involves more than just adding plants to space. It includes a comprehensive process where biophilic design strategies are guided by the spatial context, functional needs, and the specific characteristics of the users engaging with the environment [

26,

27]. The core elements of biophilic design that architects and urban planners are encouraged to consider during the design process were categorized by Kellert [

19] into six main themes. These include “environmental features, such as water, fire, and indoor vegetation; natural shapes and forms, including biomimicry and biomorphic structures; natural patterns and processes, such as fractals and sensory variability; light and space, including the use of natural daylight and spatial openness; place-based relationships, such as landscape ecology and orientation within natural contexts; and human–nature relationships, including principles of prospect and refuge, as well as reverence and spirituality” [

19].

Today, people spend approximately 90% of their time indoors [

28,

29]. Therefore, interior spaces play a vital role in sustainable development and significantly affect human well-being, as well as physical and mental health [

15,

30]. In recent years, research on applying biophilic design in interior environments has mostly focused on office settings [

29], healthcare facilities [

31], educational buildings [

9], shopping malls [

32], and hospitality and tourism spaces [

33]. These studies have highlighted the effects of various biophilic design elements, such as natural light, water features, views of nature, organic forms, vegetation and green spaces, natural materials, and nature-inspired patterns and textures. Multiple studies demonstrate that incorporating biophilic design helps reduce carbon dioxide levels [

34], improve air quality [

35], enhance acoustic performance [

36], and maintain optimal temperature and humidity conditions [

37]. Additionally, by activating the parasympathetic nervous system, biophilic environments have been shown to lower stress and anxiety, improve cognitive performance and focus, accelerate recovery, increase esthetic enjoyment, support emotional health, and promote relaxation [

38,

39,

40]. In this context, The Spheres, located at Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle, exemplifies the effective use of biophilic design in office environments by enabling employees to work in close contact with nature [

41]. Similarly, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital in Singapore demonstrates the restorative effects of biophilic design in healthcare settings through its integration of native vegetation, interior courtyards, and open-air spaces [

41]. In educational buildings, the Green School in Bali, built using natural and locally sourced materials, is notable for its use of natural light, seamless connection between indoor spaces and the surrounding environment, and its commitment to sustainable material practices [

42]. In retail architecture, Hongkong Land’s Yorkville—The Ring in China incorporates various biophilic elements, including an indoor botanical garden, water features, the effective use of natural daylight, and organically inspired structural forms [

43]. Within the hospitality and tourism sector, one notable example is the Six Senses Con Dao resort in Vietnam, which offers guests an immersive experience in nature through natural materials, open-plan architecture, and lush green landscapes [

44]. These examples collectively demonstrate the potential of biophilic design to enhance user experience across different types of built environments.

Religious buildings are among the spatial settings that accommodate a wide range of human needs, including worship practices at specific times of the day or week, spiritual exploration, and social integration [

45,

46]. Throughout history, such spaces have served as environments for personal reflection, the performance of daily rituals by believers, the delivery of religious education, the reinforcement of social belonging and communal cohesion, and venues for cultural and touristic visitation [

47].

In this context, a wide range of sacred structures, including monumental cathedrals in Europe and peaceful temples in Asia, have been built with the goal of fostering a connection with the divine and evoking a sense of transcendence. Architectural features such as soaring vaults, intricately designed stained-glass windows, and symbolic decorations are intentionally crafted to inspire feelings of awe, reverence, and deep reflection among worshippers [

48]. For example, in Gothic architecture, the use of natural light is seen as a symbol of divine illumination, while in Islamic architecture, water features inside mosques represent purification and spiritual renewal [

48,

49].

Various psychological theories and measurement tools have been developed to assess and evaluate the restorative effects of biophilic design in spatial environments. Among the most recognized are the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS). Developed by Kaplan and Kaplan [

39], ART suggests that interaction with nature can reduce cognitive fatigue and increase attention capacity. This theory holds particular importance in the fields of cognitive psychology, environmental psychology, urban design, landscape architecture, and architecture. According to ART, an environment is considered restorative if it encompasses four foundational qualities [

50]. These include “being away, which refers to a psychological or physical sense of detachment from daily pressures; fascination, the effortless and naturally rewarding way attention is engaged; extent, the feeling of being immersed in a coherent and richly detailed environment; and compatibility, which indicates alignment between the setting and the individual’s intentions, needs, and preferences” [

50,

51]. As a common framework used in environmental psychology and design fields, ART is often measured with the PRS to assess the restorative potential of physical environments. The PRS, developed by Hartig et al. [

52], is a psychological tool designed to measure how much an environment is perceived as restorative by individuals. The PRS includes items that assess the four main components of ART [

51,

53].

In this context, it is suggested that biophilic design implemented in religious buildings may influence individuals’ spiritual experiences and that being present in such spaces may offer restorative effects. For instance, Rai et al. [

54] demonstrated that colonial churches in Himachal Pradesh, India—characterized by biophilic architectural features—statistically enhanced visitors’ perceived spirituality and sense of restoration. Similarly, Pretorius [

55] showed that monastic gardens in medieval Chinese cities, which were deeply integrated with natural elements, contributed to improved mental, physical, and spiritual well-being among early urban populations. However, a review of the current literature shows that studies exploring the impact of biophilic design elements in religious settings on individuals’ spirituality levels and their psychological well-being remain limited. Given the important role of religious buildings in supporting individuals’ spiritual and emotional health, assessing how biophilic features in these spaces influence spiritual experiences and determining the extent to which these environments have restorative potential become vital areas for research.

This study aims to explore how the biophilic design approach, as applied to mosque interiors, influences individuals’ perceptions of spirituality and the restorative qualities of these spaces. The study was guided by the following questions: How does incorporating biophilic design elements into mosque interiors impact individuals’ sense of spirituality? What is the restorative potential of biophilic design in mosque interiors? Which biophilic design features are most favored by users in mosques? To address these questions, a questionnaire was developed, along with visual materials showing biophilic design elements specific to mosque interiors, which were then assessed by mosque congregants.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

An examination of the gender distribution of the participants revealed that females constituted 63.8% of the sample, while men accounted for 36.2%. Regarding age distribution, the majority of participants (56.9%) were between 18 and 30 years old, followed by those aged 31 to 50 (29.7%) and over 51 (13.4%). An assessment of participants’ educational backgrounds showed that nearly half (46.7%) held a bachelor’s degree, followed by associate degree graduates (21%) and individuals with postgraduate qualifications (14.1%). Participants with only high school or primary school education constituted 18.2% of the sample. Regarding occupational status, 48.5% of the participants were employed, while 32.1% were students. Participants identified as housewives (5.1%), retirees (8.2%), and unemployed individuals (6.2%) were less represented. An analysis of income distribution showed that most participants (38.5%) earned between TRY 23,001 and 50,000 per month, followed by those in the TRY 50,001–100,000 income range (30.3%). Participants in the lowest income group (TRY ≤23,000) accounted for 13.1%, while 18.2% reported a monthly income over TRY 100,000 (

Table 1).

3.2. Participants’ Perceptions of Biophilic Design and Its Elements

A total of 7.7% of the participants reported having detailed knowledge about the concept of biophilic design, while 37.7% stated that they had heard of the concept but lacked in-depth understanding. The remaining 54.6% indicated that they had never encountered the term before.

All participants who reported having detailed knowledge of the concept of biophilic design correctly identified it as the integration of natural elements into human-made environments. Among those who had heard of the concept but lacked detailed knowledge, 46.3% demonstrated a partial understanding of its meaning. In contrast, 85.4% of participants who had never encountered the term reported a lack of knowledge about its meaning. This difference was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 314.725, Cramer’s V = 0.635, p < 0.001).

A total of 54.1% of participants reported having previously been in a space that incorporated biophilic design elements. Among these participants, 53.6% stated that they encountered such environments occasionally, with 30.8% encountering it rarely, 13.3% encountering it frequently, and 2.4% encountering it regularly.

A large majority of participants (84.4%) expressed a desire for more biophilic design elements to be used in their living and working environments. Among those who supported wider use of these elements, 54.4% preferred them in homes, 58.4% in offices, 71.1% in schools, 59.9% in hospitals, 41.0% in places of worship, 65.7% in parks and green spaces, 44.7% in shopping centers, and 61.4% in cafes and restaurants.

There was a statistically significant difference in opinions regarding the use of biophilic design elements in religious buildings between individuals who had previously worshiped in a mosque incorporating such elements and those who had not (t(388) = 2.45, p = 0.015). In this context, participants who had worshiped in a biophilic mosque (M = 4.07, SD = 1.041) found the inclusion of biophilic design elements in religious spaces more important than those who had not (M = 3.79, SD = 1.120). Furthermore, 77.2% of participants supported the inclusion of natural light, 66.2% preferred vegetation and green spaces, 64.4% supported the use of water features, 45.1% valued organic forms, 55.6% endorsed natural patterns and textures, and 57.2% favored natural materials in the biophilic design of religious spaces.

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Before conducting the EFA for the BSPS, the appropriateness of the data for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. A KMO value above 0.90 is considered excellent [

63,

64,

65,

66], and in this analysis, the KMO value was 0.961. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also statistically significant (χ

2 = 5392.176, df = 36,

p = 0.001). Based on these findings, the data were deemed suitable for factor analysis (

Table 2).

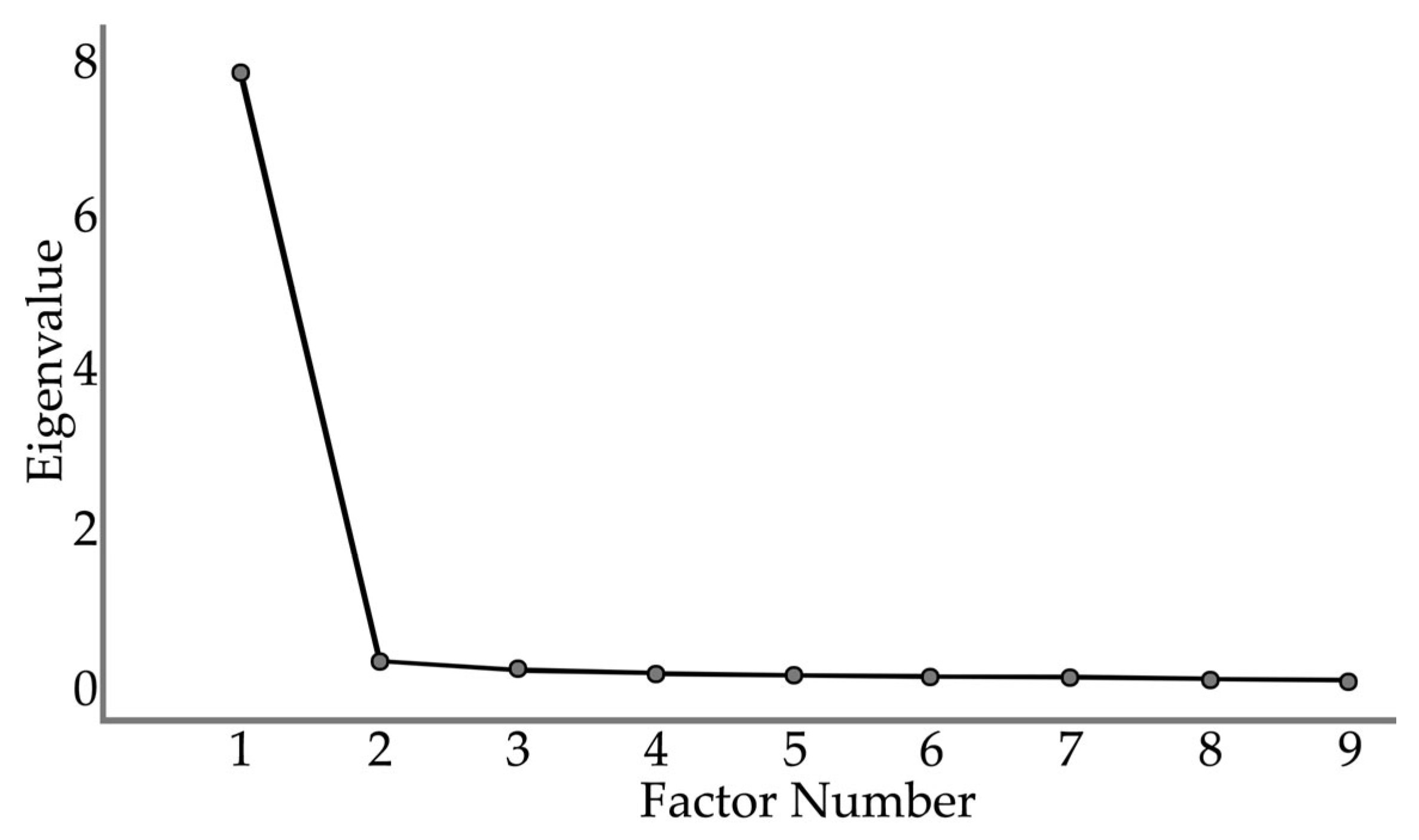

The principal axis factoring revealed a single component with an eigenvalue greater than 1. In this context, the total variance explained and the scree plot (

Figure 3) indicated hte unidimensional structure of the scale.

In the scree plot presented in

Figure 3, the curve flattens after the first point, indicating that the subsequent factors only contribute minimally and similarly to the explained variance. In the exploratory factor analysis, the minimum factor loading cutoff was set at 0.32 [

67,

68,

69], and no item was found to fall below this threshold. The contribution of the single factor identified in the analysis to the total variance was calculated as 85.146% (

Table 3). Additionally, the factor pattern and factor loadings of the scale are presented in

Table 4.

The evaluation of the factor pattern and factor loadings revealed that the loadings in the BSPS ranged from 0.855 to 0.948. The highest loading was for item I1, “Biophilic design in mosque interiors makes the space more inviting” (0.948). The lowest was for item I9, “Biophilic design in mosque interiors enables me to connect with nature” (0.855).

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

An examination of the CFA results for the BSPS showed that all t-values exceeded 2.56 and were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. Regarding error variances, no item had an error variance above 0.90 (

Table 5). All factor loadings of the items on the scale were statistically significant, ranging from 0.84 to 0.94.

Based on the fit indices from the factor analysis, a χ

2/df ratio below 3 indicates an ideal model fit [

70]. An RMSEA value under 0.08 suggests a good fit [

71], while CFI and TLI values above 0.95 indicate an excellent fit [

72]. Additionally, an SRMR value below 0.05 also demonstrates a strong model fit [

73]. These results confirm the unidimensional structure of the BSPS.

At this stage, confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the PRS. The scale was modeled based on a 4-factor structure, consisting of being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility, with a total of 26 items evaluated. In the initial model, the loadings of items I11 and I13 on the fascination factor were examined. According to the results of the confirmatory factor analysis, the loadings of items I11 and I13 on the fascination factor were found to be −0.010 and 0.006, respectively. These coefficients indicated that the items did not adequately represent the factor and did not contribute to the model. Therefore, to improve the conceptual integrity and construct validity of the PRS, items I11 and I13 were removed from the model. Additionally, based on the modification indices, error covariances were added between specific items to enhance the model.

Accordingly, error covariances were established between items I24 and I25, I25 and I26, and I24 and I26. These adjustments were justified by the content overlap among the related items and the acceptability of local dependency. The final confirmatory factor analysis results, based on the remaining 24 items, are shown in

Table 6.

Based on the results of the confirmatory factor analysis for the PRS, all t-values exceeded 2.56 and were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. Error variances indicated that no item had an error variance above 0.90. Additionally, all factor loadings of the scale items were substantial, ranging from 0.76 to 0.95. An evaluation of the model fit indices showed that a χ

2/df ratio below 5 indicates an acceptable level of model fit (

Figure 4). Based on these results, the four-factor structure of the PRS was confirmed.

3.3.3. Reliability Analysis

To assess the internal consistency reliability of the scales, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the BSPS was 0.981. For the PRS, the overall reliability coefficient was 0.970, while the reliability coefficients for its sub-dimensions—being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility—were 0.956, 0.975, 0.944, and 0.970, respectively (

Table 7). In both scales, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeded the 0.70 threshold proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein [

74], indicating a high level of reliability across all sub-dimensions.

3.4. Relationship Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Scales

3.4.1. Findings by Gender

The study investigated whether BSPS and perceived restorativeness scores varied by gender. Females (M = 33.32, SD = 10.39) scored significantly higher than men (M = 28.67, SD = 12.48) on the BSPS (t(388) = 3.94, p < 0.001). Regarding the sub-dimensions of the PRS, females also scored significantly higher than men in being away (t(388) = 3.92, p < 0.001), fascination (t(388) = 4.11, p < 0.001), and compatibility (t(388) = 2.51, p = 0.013). No significant difference was found between females (M = 8.27, SD = 4.15) and men (M = 8.48, SD = 4.62) in the extent sub-dimension (t(388) = −0.44, p = 0.658).

3.4.2. Findings by Age

The presence of significant differences in BSPS scores and the sub-dimensions of the PRS across age groups was examined using one-way ANOVA. No statistically significant difference was found between age groups in BSPS scores (F(2, 387) = 0.11,

p = 0.899). Similarly, there were no significant differences across age groups in the sub-dimensions of being away (F(2, 387) = 1.23,

p = 0.295), fascination (F(2, 387) = 0.57,

p = 0.566), extent (F(2, 387) = 0.75,

p = 0.472), or compatibility (F(2, 387) = 0.79,

p = 0.457) (

Table 8).

3.4.3. Findings by Educational Background

The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to determine whether there were significant differences in participants’ educational backgrounds and their BSPS scores, as well as in the sub-dimensions of the PRS. A significant difference was found between BSPS scores and education levels (χ2(4) = 14.47, p = 0.002). Post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences between high school graduates and bachelor’s degree holders (p = 0.024), and between high school graduates and those with postgraduate degrees (p = 0.010). A significant difference was also found between associate degree holders and participants with postgraduate education (p = 0.045).

Although a significant difference was found between education levels and the being away sub-dimension (χ

2(4) = 9.28,

p = 0.026), post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction showed no statistically significant differences. An important difference was also observed between education levels and the Fascination sub-dimension (χ

2(4) = 11.27,

p = 0.024). However, after applying the Bonferroni correction, there were no significant differences between high school graduates and bachelor’s degree holders (

p = 0.139), or between associate degree holders and bachelor’s degree holders (

p = 0.149). No significant differences were found between education levels and the extent (χ

2(4) = 2.28,

p = 0.555) or compatibility (χ

2(4) = 4.11,

p = 0.395) sub-dimensions (

Table 9).

3.4.4. Findings by Employment Status

The question of whether there were significant differences in the sub-dimensions of the BSPS and PRS based on participants’ employment status was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis H test. A statistically significant difference was found between employment status groups in terms of BSPS scores (χ2(4) = 13.01, p = 0.011). Post hoc comparisons revealed a statistically significant difference between unemployed individuals and housewives (p = 0.025); however, no other pairwise comparisons yielded significant differences (Bonferroni-adjusted p > 0.05).

A significant difference was also observed between groups in the being away sub-dimension of the PRS (χ2(4) = 10.18, p = 0.040). However, post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences between unemployed individuals and the other groups after applying the Bonferroni correction (all adjusted p > 0.05).

Similarly, a significant difference was observed between employment status groups in the fascination sub-dimension (χ2(4) = 10.18, p = 0.040); however, post hoc comparisons showed no statistically significant differences after applying the Bonferroni correction (p > 0.05).

On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were found between employment status groups in the extent (χ

2(4) = 7.48,

p = 0.114) and compatibility (χ

2(4) = 7.68,

p = 0.109) sub-dimensions (

Table 10).

3.4.5. Findings by Income Level

The presence of significant differences in BSPS and its sub-dimensions across income level groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA. A significant difference was identified between BSPS scores and income groups (F(3, 386) = 2.97, p = 0.032). The post hoc Tukey HSD test results showed that participants in the income group above 100,000 TL (M = 34.32, SD = 10.12) scored higher on BSPS than those in the 23,000–50,000 TL income range (M = 29.69, SD = 11.89); however, this difference was not statistically significant in pairwise comparisons (adjusted p > 0.05). No significant differences were observed among the other income groups either.

No significant differences were found between income levels and the sub-dimensions of the PRS: being away (F(3, 386) = 1.82,

p = 0.143), fascination (F(3, 386) = 1.70,

p = 0.167), extent (F(3, 386) = 0.40,

p = 0.755), and compatibility (F(3, 386) = 2.54,

p = 0.056) (

Table 11).

3.5. Relationship Between BSPS and PRS

Firstly, there is no statistically significant difference between participants’ frequency of visiting mosques and their views on the use of biophilic design elements in mosque interiors (F(2, 387) = 0.424,

p = 0.655). Additionally, when the effect of mosque attendance frequency on BSPS scores was examined, no statistically significant difference was observed between mosque attendance frequency and BSPS scores (t(183.71) = −0.73,

p = 0.468) (

Table 12).

The analysis of the being away variable revealed that the regression model was statistically significant (F(1, 388) = 603.67, p < 0.001). The BSPS variable explained 61% of the variance in being away scores (R2 = 0.609), with a strong and positive effect (β = 0.780).

Regarding the fascination dimension, the regression results also revealed a statistically significant model (F(1, 388) = 739.83, p < 0.001). In this case, BSPS accounted for 66% of the variance in fascination scores (R2 = 0.656), demonstrating a strong positive relationship (β = 0.810).

In contrast, the model for the extent variable was not statistically significant (F(1, 388) = 0.76,

p = 0.384). The BSPS variable explained only 0.2% of the variance in extent scores (R

2 = 0.002), and the relationship between the two variables was not significant (β = −0.044). Finally, the regression analysis for the compatibility variable produced a statistically significant model (F(1, 388) = 512.29,

p < 0.001). The BSPS variable accounted for 57% of the variance in compatibility scores (R

2 = 0.569), with a strong and positive effect (β = 0.754) (

Table 13).

4. Discussion

The effects of the built environment on individuals’ physical health [

60,

75], psychological well-being [

57], and spiritual perceptions [

76] have been thoroughly documented. Built environments are settings that require ongoing attention and interaction in daily life [

77]. However, the high density of stimuli in these environments can lead to mental fatigue and cognitive exhaustion [

27,

78]. The current literature in environmental psychology suggests that urban stimuli place a greater load on the cognitive system than natural environments, thereby increasing cognitive fatigue [

79,

80]. In this context, the potential negative effects of built environments have heightened the need for biophilic spaces that support attentional restoration and psychological balance.

Increased interaction with natural elements enhances individual well-being, enhances attentional capacity, and helps relieve stress [

9,

25,

81]. However, urbanization has reduced opportunities for people to connect with natural environments, and built environments have become a major barrier to human–nature interaction [

30,

59]. In this context, biophilic design acts as a bridge between the built environment and nature, improving interaction with natural elements [

26,

58]. However, as McGee and Park [

82] point out, implementing biophilic design in interior spaces is a complex process because of nature’s multidimensional and diverse character.

Aligned with the aim of this study, the impact of biophilic design on individuals’ perception of spirituality in mosque interiors is examined. Since no existing scale in the literature directly measured this specific relationship, the BSPS was created as a new measurement tool. The scale’s development process was meticulously conducted through expert evaluations and pilot testing, with its one-dimensional structure and high levels of validity and reliability confirmed through EFA and CFA. As a result, the BSPS provides an innovative and reliable instrument for assessing how biophilic elements in mosque interiors influence perceptions of spirituality, thereby contributing to the existing literature. To assess the restorative effects of biophilic mosque interiors, ART and its measurement instrument, the PRS, were employed. Two items from the fascination dimension of ART were removed due to structural inconsistency; this adjustment ensured the scale’s conceptual coherence, improved the validity of the measurement model, and increased its reliability.

Recent studies [

83,

84,

85] indicate a growing use of AI-based visual production tools in architectural research, particularly in conceptual visualization and user perception studies. While these tools offer valuable opportunities, their use in culturally and religiously sensitive environments—such as mosque interiors—requires careful consideration. As highlighted by Obaid and Omar [

86] and Sukkar et al. [

87,

88] current AI models often lack the cultural specificity and symbolic depth necessary to fully represent sacred architectural spaces. For this reason, expert oversight and contextual knowledge are crucial in interpreting or applying AI outputs in Islamic architectural settings. In the present study, mosque interiors were generated in a culturally respectful manner by avoiding figurative or inappropriate elements and adhering to the general spatial and material characteristics of Islamic architecture. The sole purpose of these images was to facilitate perception-related assessments of biophilic design. The visual materials were reviewed by researchers with architectural and theological backgrounds to ensure alignment with ethical research standards and cultural sensitivities.

The study’s findings showed that the restorative impact of biophilic mosque interiors and perceptions of spirituality varied by gender. Females reported higher perceptions than men, particularly in the being away, fascination, and compatibility sub-dimensions. This may be due to females’ increased sensitivity to environmental stimuli and their greater psychological benefits from nature-inspired settings [

89,

90]. Additionally, females’ greater interest in spiritual matters and higher levels of religious commitment compared to men also support this result [

91,

92]. These findings help explain why females demonstrated greater interest in this study, which focused on the evaluation of biophilic mosque interiors. Moreover, when it comes to spiritually and restoratively perceived environmental stimuli like biophilic design, females’ heightened environmental sensitivity and emotional awareness are believed to influence these perceptions.

The analysis revealed that neither the perception of spirituality nor the restorative effect of biophilic mosque interiors varies across age groups. Unlike some earlier studies, this suggests that the spiritual influence of biophilic design elements in mosque interiors is not exclusive to older people; individuals of different ages can also experience similar spiritual benefits within religious spaces. Several studies in the literature indicate that advancing age often leads people to think more introspectively due to factors like seeking meaning in life, contemplating the afterlife, losing close social ties, and facing increasing health challenges [

93,

94,

95]. This inward focus then encourages them to turn to spiritual resources. However, in modern contexts, individuals’ lifestyles, levels of introversion, and environmental sensitivity complicate the relationship between age, spiritual perception, and restorative impact. Within this context, it can be suggested that biophilic design in sacred spaces like mosques has a universal ability to foster inner peace, providing restorative support across different age groups.

The study reveals that the effect of biophilic design in mosque interiors on spirituality perception tends to grow as education level increases. However, because spiritual perception is a subjective and personal experience, it cannot be solely linked to educational attainment. This inconsistency across empirical studies suggests that the relationship between education and spirituality remains context-dependent and theoretically debated. While Kıraç [

96] reported the existence of a positive link between educational attainment and spirituality levels, Gürsu and Ay [

97] argued that education does not have a significant effect on spiritual well-being. Additionally, the literature indicates that people’s awareness of nature and environmental sensitivity generally rises with higher levels of education [

98,

99]. However, in this study, no statistically significant differences were observed between educational levels and the dimensions of restorative effect, particularly in multiple comparison analyses.

Biophilic design in mosque interiors appears to support restorative perceptions across individuals from various socioeconomic backgrounds. However, the analysis indicated no statistically significant differences in this perception based on participants’ income or employment status. Notably, although income level did not have a meaningful impact on spiritual perception, a significant difference emerged between housewives and other non-working participants. This may be because individuals who spend more time indoors, like housewives, tend to develop a deeper spiritual connection with sacred spaces.

The analysis revealed that mosque attendance frequency is not associated with the impact of biophilic design on spiritual perception. This suggests that the influence of biophilic design on spiritual experiences is not necessarily tied to time but is more affected by spatial and environmental factors. As highlighted by Kaplan and Kaplan [

39] and Ulrich [

38], even brief interactions with natural elements can greatly foster psychological and spiritual renewal. In

The Luminous Ground, the fourth book in The Nature of Order series, Alexander [

100] claims that space not only has a physical dimension, but also an existential and spiritual one. According to Alexander, the living structure enhances the sense of life of both the space and the user through the holistic relationship of its centers [

100]. This approach overlaps with the effects of biophilic design on the perception of spirituality in mosque interiors discussed in this study. In mosque architecture, central elements such as the dome and mihrab are compatible with Alexander’s concept of centers; through these elements, the user establishes a deep connection with the space and lives a spiritual experience. In this context, the findings of the studies on the relationship between biophilic design and spirituality, when supported by Alexander’s theoretical framework, offer a deeper perspective on how both spiritual and vital integrity can be built in religious buildings.

The findings of this study demonstrate that biophilic design in mosque interiors contributes to stress reduction, enhanced emotional well-being, cognitive support, and a heightened sense of spiritual calm. These outcomes reinforce the value of integrating natural light, vegetation, water elements, natural materials, and organic forms within sacred interiors. In parallel, Agboola et al. [

101] emphasize that biophilic design also contributes meaningfully to sustainability goals in architecture. Together, these perspectives support the development of a holistic design strategy that addresses both user well-being and environmental sustainability.

Mosques serve as spaces where Muslims practice their faith, engage in worship, and express their cultural identity [

46]. Throughout history, mosques have experienced structural changes, influenced by the socio-cultural and architectural traits of their respective construction periods [

102,

103]. After the industrialization efforts of the Republican period, unplanned and rapid urbanization processes negatively impacted mosque architecture in Türkiye. Several legal frameworks, such as Law No. 3194 on Zoning, the Regulation on the Preparation of Spatial Plans, and the Zoning Regulation for Planned Areas, have been established. However, there is currently no legal regulation that explicitly governs the architectural and esthetic qualities of mosques.

The official guideline developed to assist relevant individuals and institutions in planning and designing mosques does not include any provisions related to biophilic design principles. This omission is probably due to a lack of awareness about biophilic design, as well as the inadequacy of existing design guidelines, industry standards, and methodological frameworks in this area.

5. Conclusions

Since ancient times, sacred structures have led the way in biophilic design through their symbolic, functional, and spatial links to nature. From Egypt and Mesopotamia’s religious monuments to East Asian temples, and from Hellenistic sanctuaries to the sacred architecture of Abrahamic faiths, natural elements have consistently been key parts of sacredness and spirituality. In Islamic architecture, especially in mosque design, traditional biophilic features such as water elements inspired by paradise gardens, shade trees, and large open courtyards help to create a richer biophilic experience (e.g., the Alhambra Palace, and the Süleymaniye, Selimiye, and Blue Mosques).

This study is one of the pioneering efforts used to quantitatively examine how biophilic design principles in mosque interiors influence individuals’ perceptions of spirituality and their experience of restorative spaces. It emphasizes the multidimensional impact of these principles on perceptions of spirituality and restorative experiences within mosque interiors. The BSPS, created as part of this research, makes a valuable contribution to the literature as a new measurement tool used for the first time in this field, with a high level of internal consistency (α = 0.981). This scale provides a strong foundation for assessing how biophilic elements affect the link between mosque interiors and people’s inner spiritual worlds. Moreover, the study’s innovative methodological aspect is the creation of mosque interior visuals using AI tools and utilizing these visuals as data collection methods in the scale application.

Empirical evidence from the study confirms that biophilic design should be seen not just as an esthetic approach but as a comprehensive strategy that promotes psychological, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Mosque interiors that incorporate biophilic elements were found to enhance individuals’ perception of spirituality by 70.3% and amplify their restorative experience by 67.6%. These findings strongly suggest that spatial design is closely linked to mental functions like attention restoration, stress reduction, and the cultivation of inner peace.

Furthermore, the fact that the impact of biophilic design appears to be independent of demographic variables, such as age, income level, and frequency of mosque visits, suggests its broad applicability. Notably, female participants reported higher scores in the dimensions of being away, fascination, and compatibility, highlighting the decisive role of environmental sensitivity and spiritual awareness in shaping individual experiences.

Nonetheless, the lack of biophilic design criteria in current planning and design laws in Türkiye is a significant shortcoming that hampers the development of mosque interiors in this area. Incorporating Kellert’s biophilic design principles into mosque design guidelines and relevant regulations not only enhances architectural quality but also contributes to the creation of culturally and psychologically enriching worship environments.

The architecture of mosques in Türkiye has been shaped by both the shared traditions of the Islamic world and the local building culture of Anatolia. Regional factors such as climate, materials, settlement patterns, and cultural values have contributed to architectural variation. While this study focuses on mosque interiors from the Turkish Republican period, which reflects a modernized and state-guided interpretation of mosque design, it does not encompass the full diversity of mosque architecture across history or geography. Future studies that include different styles and periods will provide a more holistic understanding of how biophilic design affects spiritual and restorative perceptions in sacred architecture.

Finally, biophilic design proves to be a multidimensional approach that supports individuals’ spiritual and psychological well-being within sacred spaces like mosques. The institutional recognition of this approach is crucial not only for improving spatial quality but also for enriching the worship experience.