Abstract

The growth of urban areas and climate change affect the performance of water management, increasing the rate of flooding and decreasing the quality of available water. To address this issue, the sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDs) and conventional urban drainage systems (UDIs) must be promoted. In both systems, grey infrastructure plays an important role, in the form of reinforced concrete tanks, filters, and water treatment plants. Nowadays, the use of reinforced concrete is a major contributor of the environmental impact of human activities environmental impacts. This study aims to assess the potential of nanoparticle-based concrete to mitigate the environmental impacts of water management facilities. To achieve this target, a comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) analysis was performed on a multi walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) based concrete, and a conventional one. To evaluate the corresponding benefits, a Functional Unit has been defined representing a frequently used element in water management facilities. The conducted review found no similar research. It is noted that the functional units used in published studies on nanoproducts are usually defined for the production of mass units. This study, found that using MWCNT-based concrete reduced the weight of the steel reinforcement by 47%. This reduction in steel outweighs the environmental impacts corresponding to used MWCNTs. The impact scores obtained are significantly lower for the MWCNT-based concrete. Therefore, the use of this material is recommended in Water management facilities, only on an environmental basis. Further investigation is recommended into the economic viability of this use.

1. Introduction

Currently, there are two main challenges regarding water management: the consequences of climate change and the steep increase in the surface area of urban areas [1]. Both issues increase the incidence of stormwater damage and reduce the filtering capacity of affected soils [2]. The consequences of climate change include acute rainfall episodes, winter-based circumstances, and an annual increase in flood cases. By 2050, the world population is predicted to reach 9800 million people, and 60% of the population is predicted to live in urban areas [3]. The urbanisation process seals the affected areas’ soil by covering it with pavement, which contributes to the adverse effects of stormwater runoff [2].

These issues are addressed in initiatives such as The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which include water and sanitation accessibility and urban resilience against natural disasters. In the EU, the above-mentioned initiatives are further developed in compulsory laws, such as the EU Water Framework Directive and the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive [4]. The implementation of these principles and regulations involves an increase in investment in urban drainage systems. The UN has reported a gap of 61% in the investment in water and sanitation facilities [4]. Furthermore, the current estimates of the EU point to an annual 50% increase in capital investment in wastewater management facilities [4]. For a great city such as Barcelona, the scheduled increase in the budget of the Integral Drainage Plan has risen nearly 100% from the previous one [3].

These new facilities are projected as new or extended water supply systems, alternative water resources, and additional storage [4]. All these facilities help to cope with climate change and drought risk. The proposed revision to the EU Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive promotes sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS), with integrated urban wastewater management plans (UDS) [4]. These hybrid systems (‘grey’ and ‘green’) are projected to collect rainwater and storm water runoff at or near its source and transport it to areas where infiltration into the ground is possible [5]. For example, the Barcelona Integral Drainage Plan includes SUDS implementation and storm tanks, first flush tanks, and conduits other than the SUDS [3]. Consequently, a substantial increase in the construction of grey elements in water management facilities is expected.

Bearing in mind that most of water management grey facilities elements are made of reinforced concrete, the expected increase in these facilities is an environmental problem. Research has alerted on the reduction need of impacts corresponding to Cement and steel use [6]. Cement and steel production are intense in energy and resources consumption; therefore, they are responsible of high emissions, resulting in a contribution for each of them of 7–8% of global CO2-eq emissions [7]. Currently, the production of one ton of cement emits about 0.63 Ton CO2-eq, and the production of a ton of steel 1.09 Ton CO2-eq [8,9]. Extensive research has been conducted on reducing the impacts of cement and steel. Research areas in the cement industry comprise improving production process efficiency [10], converting to electricity-based processes [11], carbon capture and storage [12], and the introduction of alternative raw materials [13]. In the case of steel industry, research has explored the use of recycled steel [14], hydrogen-based production processes [15], the use of biomass as an energy source in the production [16], and the recycling of gasses and scrap generated in the production [17]. Finally, holistic approaches are considered the most effective strategies to tackle this issue [8,14]. Following these efforts, this study is in line with nowadays efforts to reduce the huge environmental impact produced by the widespread use of steel reinforced concrete use. This study aim is to evaluate the resulting environmental benefit of the use of MWCNT reinforced concrete in water management grey facilities.

Nowadays, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are one of the most interesting groups of nanoparticles for the industry, representing a market share of 26% of the overall nanomaterials industry [18]. They are classified as single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs), which are referred to particles in the form of nanotubes with a single wall, and multi-walled nanotubes (MWNTs) [19]. Regarding these two CNT types, SWCNT production is more intensive in terms of energy use than MWCNTs, as the former requires an additional purification process [20]. Consequently, SWCNTs are mostly used when their specific properties are required [20]. Conversely, MWCNTs exhibit the highest efficiency in terms of resistance enhancement of resulting cementitious products [21]. Among the production systems used to obtain manufactured nanotubes, the most widely used in industry today is carbon vapour deposition (CVD) [22,23]. The production of both SWCNTs and MWCNTs is intensive in electricity consumption, resulting in the main contributor of the corresponding environmental impacts [23]. This energy-intensive process is outweighed in the production of the corresponding nanoproduct because nanoparticles are combined with bulk material in a very small proportion [21]. Finally, as this is a novel technology, producers do not disclose data regarding the industrial production processes of CNTs; therefore, current research is based on laboratory scale and pilot plant production results [19,24]. In this respect, published research concerning the scaling up of CNT production established that industrial processes may decrease the research-measured energy consumption by one to two orders of magnitude [25]. Scaling up the production of SWCNTs from a small size to industrial production can reduce the corresponding impacts by up to 94% [26]. In [27], the reported scaling up to industrial production yielded an impact reduction factor of 6.5 of the results obtained in the laboratory scale production. More recently published studies have evaluated this reduction of up to 88% of the impacts in the case of silver nanoparticles production [18]. As a result, current research relies on the use of theoretically scaling up factors and extrapolating the results [28].

The properties of CNTs Cementitious materials have been widely studied, and the results show enhanced tensile and compressive strength [20,29,30], enhanced conductivity [31,32], and waterproof improvement [31,33]. The most influential factor in the production of CNT-based concrete is the degrouping and redistribution of CNTs within solvents, which is called the dispersion process [34]. Dispersion can be achieved using the ultrasonication technique [35], and currently, surfactant-assisted ultrasonication is the most commonly used method [36]. Several products have been tested as surfactant agents; non-ionic polyoxyethylene [37], the mixture of sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) and Triton X-100 (TX10) [38], and polycarboxylate superplasticizers, which are considered the most effective dispersion agents [21,39].

Concerning the environmental aspects of nanoparticles, the current steep increase in worldwide production has raised concerns regarding the existing lack of knowledge about the behaviour of the product released to the environment [40]. Research on the fate, exposure, and toxicity of nanoparticle emissions to living tissues is scarce [41,42]. As a result, the environmental impacts of this energy-intensive production process need to be evaluated [18]. In this regard, the method of consensus to assess these environmental impacts is the Life Cycle Assessment, (LCA) [43]. Regarding the use of LCA to evaluate nanoparticle production, published research has reported the lack of characterisation factors for nanoparticle emissions in existing calculation methods [42,43]. Furthermore, published Life Cycle Assessment studies usually refer to a mass functional unit related to a nanoparticle production method; therefore, they do not accurately represent the benefits of the corresponding nanoparticle use [24,42,43].

This study aimed to evaluate the ability of MWCNT reinforced concrete to mitigate the environmental impacts associated with the expected seep increase in water management grey facilities construction. A comparative Life Cycle Assessment of a hypothetical water tank wall, built with in situ reinforced concrete, was performed to assess the impact reduction. The composition of this element has been defined for two models: a conventional reinforced concrete (Model B) and a reinforced concrete with carbon nanotubes (MWCNT-based concrete) (Model A). The chosen structural component is a standard feature in water management infrastructure, including storm tanks, first flush tanks, and wastewater treatment facilities; consequently, the findings are meant to be indicative of these grey infrastructure.

The MWCNT production data were obtained from [44]. Data for MWCNT energy consumption production were obtained from reference [23]. The consumption and emissions corresponding to the adopted dispersion method were obtained from [30]. The composition and resulting characteristics of the assessed MWCNT concrete were obtained from [45]. The requirements of the designed elements for models A and B were designed according to Eurocode 2 [46]. Currently, Eurocode 2 [47] regulation is compulsory in the European Union to define the structural elements of steel reinforced concrete.

The novelty of this study is the use of the LCA method to evaluate the complete design of this structural element. Although several researchers have studied the LCA of the most used nanoparticles, such as MWCNTs, these studies usually focus on mass unit production processes [42,43]. Reported LCA studies of applied nanoproducts are scarce [18]. A comprehensive review of the existing literature found no other comparative LCA studies introducing a functional unit defined for 1 m2 surface of a water tank reinforced concrete wall. Furthermore, this study applies the current regulation criteria to obtain waterproof reinforced concrete structural elements, which involves cracking width control. The enhanced flexural properties of MWCNT reinforced concrete produce a reduction in steel use, and this reduction outweighs the impacts associated with the use of MWCNT. Considering that all data used were obtained from published research and the design method is based on the current compulsory regulation, the obtained results are considered valid.

Following the obtained results, the introduction of a very reduced proportion of MWCNTs in the conventional concrete allows for a 47% reduction in the steel reinforcement weight. Consequently, the obtained impact scores for the most relevant categories are lower for the reinforced MWCNT-based concrete model than for the non-reinforced concrete model. Moreover, in the conducted sensitivity assessment regarding electricity consumption, the use of photovoltaic electricity in the MWCNT production process resulted in a further reduction in impacts. Finally, an industrial production scenario was defined by applying the scaling up coefficients for the impact categories discussed in reference [26]. The results of this industrial production scenario calculation show that the obtained scores in all assessed impact categories are substantially lower for Model A.

Overall, the obtained results indicate that the use of reinforced MWCNT-based concrete has the potential to reduce the huge environmental impact corresponding to the assessed structural element, which is included in most water management grey facilities. A 47% reduction in steel use is in line with current efforts to reduce the impact of steel reinforced concrete. The obtained results clearly show that this reduction outweighs the impacts corresponding to the use of MWCNT. Following the commented results, the use of this MWCNT is recommended in water management grey facilities on an environmental basis. This study does not include economic criteria; therefore, further research is needed to assess the economic viability of this proposal. However, information gaps regarding nanoparticle emissions and the risks associated with the resulting exposure, together with the existing lack of available information regarding production at an industrial scale, must be investigated to obtain more exact results [41,42].

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the materials assessed in the study as well as the methods used to evaluate the resulting environmental impacts which is Life Cycle Assessment (LCA).

2.1. Structural Design of Model A and Model B

Reinforced concrete is one of the most used construction materials nowadays [19]. Hardened reinforced concrete has a microscopic structure with voids, which reduces its resistance to tensile stress and increases its water permeability [21]. The criteria of the current regulation to define the waterproof characteristics of reinforced concrete is cracking width control [47] (EC2 Section 7.3.1). The cracking width must be reduced to enhance the waterproofing of a structurally reinforced concrete. This is usually achieved by increasing the cement and steel content of the composite. In this regard, there is published research on the use of MWCNT addition to concrete. These nanoparticles occupy the voids within the microscopic structure of concrete, thereby increasing its tensile strength and waterproofing properties [31,36,48]. In this regard, the results of reviewed research on carbon nanotubes tested in small proportions as a component of concrete are specimens with enhanced compression stress and increased tensile stress resistance [20,30,45].

In this study, the walls of a water tank, built with in situ reinforced concrete, were designed. This is a common element included in water and sanitation facilities. The composition of this hypothetical element has been defined for two models: a conventional reinforced concrete (Model B) and a reinforced concrete with carbon nanotubes (MWCNT-based concrete) (Model A). The mechanical properties of the used MWCNT-based concrete (Model A) were obtained from published research results [45]. In both cases, the requirements for the designed element were calculated according to Eurocode 2 [46]. Currently, Eurocode 2 [47] regulation is compulsory in the European Union to define the requirements needed to produce reinforced concrete structural elements. Therefore, it regulates the cement, sand, and coarse mixtures, resulting in the corresponding concrete class. Similarly, this standard is the basis for calculating the steel reinforcement required for any structural application of reinforced concrete.

The concrete elements bearing stresses show cracking. The crack width value is the defining characteristic of this cracking. This value affects the waterproofing characteristics of concrete [47] (EC2 Section 7.3.1). Following Eurocode 2 Part 1.1, Table 4.1, the required concrete exposure class for water tanks is XD2, which is achieved with a minimum concrete compressive strength of 30 N/mm2 and a minimum cover for the reinforcements of 45 mm. Finally, the recommended maximum cracking width for elements bearing filling and emptying water cycles is 0.1 mm [47].

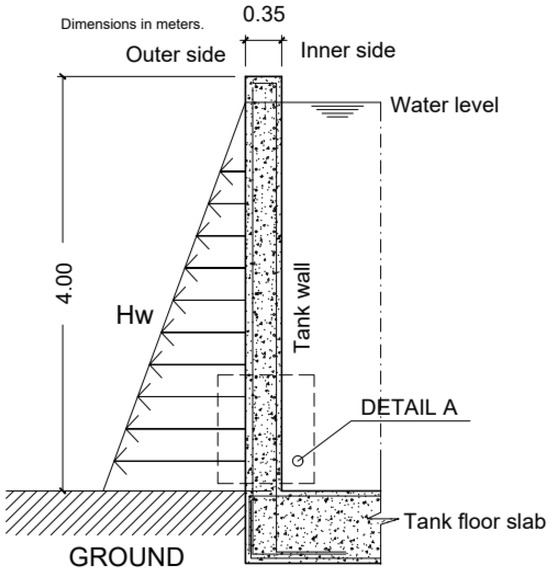

In this study, the in situ reinforced concrete wall of a prismatic water tank is studied. The characteristics chosen to develop this tank wall structural calculation are as follows: water height of 4.00 mts, vertical walls, and a thickness of 35 cm. These characteristics are very common, as the advised minimum height of this type of water tank is 4.00 m, allowing the use of the equipment necessary for maintenance. The proportion of 4.00 m height to 0.35 m depth usually leads to the optimal use of combined concrete and steel. For these elements, the most demanding case is the on-ground tank bearing the hydrostatic pressure corresponding to the filled situation (Figure 1). In this case, the hydrostatic horizontal forces (Hw) produce the main stress, which generates a bending moment (Mw) at the base of the wall tank, as shown in Figure 1. The wall is calculated as a cantilever fixed to the tank floor slab.

Figure 1.

Assessed tank wall. Geometry.

The reinforced concrete section of the wall is designed to resist Mw at the base of the tank, with a concrete cracking width maximum value of 0.1 mm.

2.1.1. Model A and Model B Mechanical Properties

In this study, the characteristics and composition of the hypothetical MWCNT-based concrete and conventional concrete Model B have been defined according to the reference research [45]. Following this, the designed conventional concrete specimen, Model B, was designed to show a compressive strength of 50 MPa. The cement, sand, coarse, and water proportions are reported in Table 1. In the reference research, the optimised enhanced mechanical properties for Model A are defined for concrete with a proportion of 0.20% MWCNTs to cement weight. The reported results for this optimised specimen are a 23% improvement in compressive strength (fck) and a 22% improvement in tensile strength (fctm). The enhanced mechanical properties of Model A, adding MWCNT to the same mix of Model B, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Assessed tank wall characteristics.

2.1.2. Model A and Model B Design

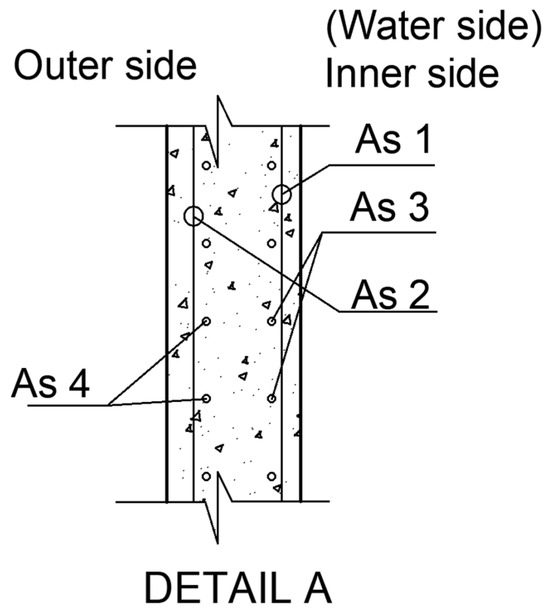

The steel reinforcement for the assessed wall (Figure 1) was designed to resist the bending moment Mw (Figure 1). The design value for this bending moment is 10.66 mTon/m. This bending moment is resisted by the vertical reinforcements corresponding to the wall’s inner side As1 (Figure 2). As1 was calculated following [47] EC2 Section 7.3.4 for a maximum crack width of 0.1 mm. It is noted that the crack width calculation mainly depends on both the steel reinforcement area and the concrete mean tensile strength, fctm. The rest of the needed reinforcements are designed to resist secondary forces. These are generally defined as a proportion either of the main reinforcement As1 or a proportion of the wall cross section, according to EC2 Section 9.6.

Figure 2.

Detail A. Assessed tank wall steel reinforcement.

Table 1 presents the reinforcements required for the conventional reinforced concrete water tank wall (Model B). These results show that Model A, including the addition of 0.2% to cement weight, of MWCNTs, allows the reduction of 47% weight used of steel reinforcement for each square metre of tank wall. The calculation of both Model A and Model B is detailed in the available Supplementary Materials (Annex A).

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment Method

Once it has been established that the use of a small proportion of MWCNTs saves a significant amount of steel, the potential reductions in the environmental impacts must be evaluated. A comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was performed for this purpose. LCA is a method to calculate the environmental impacts of products and activities and follows the framework defined in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards [49,50]. The software SimaPro by Pré Sustainability B.V. was used in this study [51]. The used release version of the programme is SimaPro 10.2.0.1. The used version of the elementary flows database is Ecoinvent 3.11.

2.2.1. Goal of the Study

The goal for this study is to obtain the environmental impact scores for the reference scenario, Model A (steel reinforced MWCNT-based concrete, as defined in the previous section), and to compare them with the scores corresponding to Model B (the conventional reinforced concrete defined in the previous section).

2.2.2. Scope of the Study

The scope of this study is the stages included in a comparative cradle to construction site LCA analysis, including product stages A1–A3 and construction stages A4 and A5, as defined in [52] (EN 15804). As mentioned in precedents sections, data corresponding to the use and end of product phases for CNTs are scarce or nonexistent for Model A [18,43]. Consequently, the resulting study is a cradle to construction site LCA, limited to phases A1–A3 plus A4 and A5.

As remarked in [19,43], the available data to evaluate the consumption and emissions of Model A are referred to a lab or a pilot plant scale. It is noted that the use of resources and energy at this scale is significantly less efficient than in industrial production [18]. In this study, the data corresponding to the production of carbon nanotubes were obtained from a pilot plant, according to data included in [23]. Table 2 shows the data corresponding to the used consumptions and emissions. On the other hand, the environmental data used for Model B were obtained from available databases [53] (Ecoinvent 3.11), representing the current market in the European Union EU 27.

Table 2.

MWCNTs production process, consumption, and emissions.

Table 3.

Catalyst production (Ion on Zeolite powder).

Table 3.

Catalyst production (Ion on Zeolite powder).

| Ion on Zeolite Powder (Catalyst) | Units | Batch (0.22 GR) | Mass (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Produced | g | 0.22 | 10.00 |

| Consumption | |||

| Iron III chloride, 40% in water | g | 1.19 | 54.10 |

| Deionized water | g | 2.20 | 100.00 |

| Nitrogen | g | 2.77 | 126.00 |

| Energy | |||

| Electricity | kWh | 1.98 × 10−2 | 0.90 |

| Output | |||

| Nitrogen | g | 2.77 | 126.00 |

The adopted functional unit (F.U.) for all calculations is 1.00 m2 of the in situ reinforced concrete wall of a water tank, designed following the European Union regulation for structural reinforced concrete elements [47], as defined in Section 2.1.3—Design working life, durability and quality management of Eurocode 2. It has to be mentioned that the chosen geometry for the designed water tank represents a common situation, with the aim of assessing the potential steel savings for replacing conventional reinforced concrete with reinforced MWCNT-based concrete. The reference life service (RSL) adopted F.U. in this study is 50 years, as this is the “design working life” defined for building structures and other common structures (Category 4) in [46] “Eurocode 0—Basis of structural design”.

2.2.3. Inventory Analysis—LCI Modelling Framework

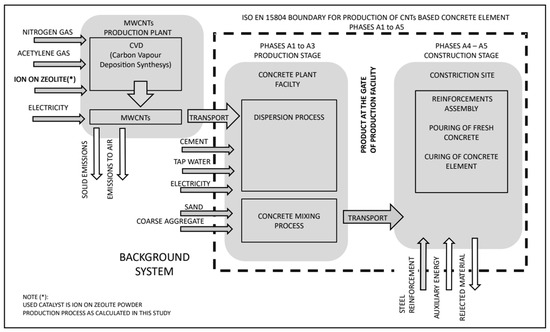

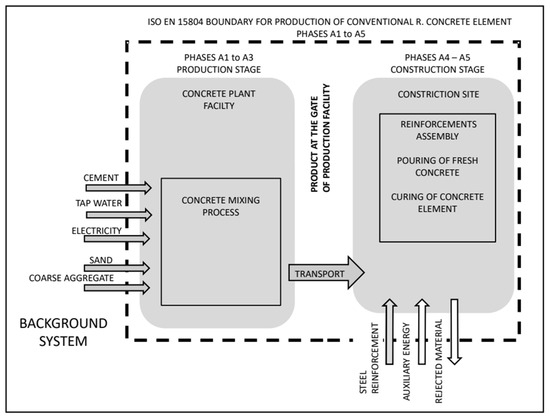

The adopted standard for LCI calculation of Models A and B is [52]. This decision has been adopted to enable the comparison with Environmental Products Declarations (EPD) [56] of similar elements within the EU27 geographical range. According to [52] (EN 15804), the LCA attributional approach has been adopted [50,52,57]. Consequently, this study is representative of the existing conditions in the EU27. The information used to calculate the impact scores corresponding to the elementary flows of both, Model A and B was obtained from existing databases (Ecoinvent 3.11) and represents current technology in Europe. Table 4 shows the used elementary flows. Regarding allocation, there are no secondary products in the assessed processes, so it is not necessary to define allocation rules in this study. Regarding cut-off rules, all inputs and emissions corresponding to the production, transportation and mixing of the CNTs needed to obtain the enhanced concrete, Model A, have been included, as shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the inputs and emissions corresponding to the conventional concrete, Model B. All these inputs are included in the elementary flows used to calculate the conventional components.

Table 4.

Model A and Model B. Use of data.

Figure 3.

Assessed CNTs-based reinforced concrete element production. System boundaries.

Figure 4.

Assessed conventional reinforced concrete element production. System boundaries.

Following the above-mentioned conditions, the system boundaries have been adopted according to the cradle-to-gate approach with additional A4 and A5 phases, in line with the modular structure established in EN 15804. Therefore, the following stages have been assessed:

- A1: Extraction and processing of raw materials.

- A2: Transportation to the concrete mixing plant.

- A3: Production at the concrete mixing plant and the obtention of the final product at the factory gate. Including energy consumption and processing of wastes.

- A4: Transportation to the construction site.

- A5: Construction phase. In this case, the installation of steel reinforcements and the pouring of fresh concrete

As declared in precedent sections, this study has been elaborated following the EN 15804 standard. As a consequence, it is compulsory to apply the impact calculation method [58] (CML 2016). This method includes the following impact categories:

- -

- Abiotic resource depletion (kg Sb eq).

- -

- Primary energy depletion (MJ).

- -

- Global Warming Potential. GWP 100 (kg CO2 eq).

- -

- Stratospheric ozone depletion potential ODP (kg CFC−11 eq).

- -

- Photochemical ozone formation potential, POCP (C2H4 eq).

- -

- Soil and water acidification AP (kg SO2 eq).

- -

- Eutrophication potential EP (kg PO4--- eq).

In addition, the impact scores corresponding to Human toxicity, which is not included in the EN 15804 standard, were calculated. This decision has been adopted to represent the impact on this category, as it is a concerning issue regarding the extended use of nanoparticles.

- -

- Human toxicity. kg 1,4-DB eq.

It should be noted that specific emissions and toxicity values for exposure to nanoparticles are not included in [58] CML 2016. In the same way, they are not included in any other available impact characterisation method

Finally, it has been implemented in the corresponding Normalisation step. This step is optional in the LCA methodology [51,57], but its use is advisable to improve the interpretation of the obtained results. The Normalisation factors used in this study correspond to CML EU25+3 [59,60]. Moreover, weighting factors have not been used in this study.

2.3. Life Cycle Assessment of Developed Product

Although several researchers have studied the LCA of the most used nanoparticles, such as MWCNTs, the functional unit of these studies is usually the mass unit production process of the product [42,43]. Furthermore, research has established that the assessed functional unit must be defined on the basis of functional equivalence to include the benefits associated with the use of nanoproducts [42]. Conversely, LCA studies of applied nanoproducts are scarce [18]. In this study, a comparative LCA of a nanoproduct, which is a MWCNT-based reinforced concrete (Model A), and the corresponding conventional product (Model B). The assessed functional unit is 1 m2 of a water tank wall. Moreover, the conducted review of existing research articles did not find another comparative LCA study with a functional unit defined for an MWCNT-based reinforced concrete element.

2.3.1. Input Data

The material composition of the assessed Model A and Model B is described in Table 1.

Data Corresponding to Reinforced Concrete Model A and B

According to the boundaries for the assessed processes, defined in Figure 3 and Figure 4, it has been considered that raw materials described in Table 1 are transported to the concrete plant, where the CNT dispersion process is performed. After that, the concrete components are mixed. Finally, the mixing of fresh concrete is transported to the construction site to produce the reinforced concrete wall. The transport distances for raw materials are equal for Model A and Model B, as the only difference is the weight of the MWCNTs used, which is negligible (0.2 wt% to cement weight).

The maximum transport distance from the concrete plant to the construction site is limited to one hour. This is so as to preserve the concrete properties once the fresh concrete is mixed. In practice, this means an average of 50 km. A transport distance of 50 km was considered for the steel reinforcements because this is the average distance from steel wholesale stores to the construction site.

Data Corresponding to Production of MWCNT-Based Concrete Model A

To model the production of the MWCNTs included in Model A, the data have been obtained from the reference research [44]. The production method assessed in this reference research is the CVD synthesis method. Because this process is defined at the lab scale, the efficiency is low [18]. To compensate for this shortcoming, the energy consumption data corresponding to the CVD pilot plant equipment was used [23]. It must be stressed that data regarding the industrial production of nanoparticles are currently scarce or do not exist [18]. To model the emissions to air presented in Table 2, the elementary flow representing the incineration of waste coal was chosen because the emissions have a similar composition [61]. The considered consumption and emissions corresponding to the assessed MWCNTs production are presented in the following Table 2

In addition to this, the necessary dispersion process has been assessed. The surfactant-assisted ultrasonication method with polycarboxylate surfactant was used, as this is the most commonly used dispersant method [34]. The considered consumption and emissions corresponding to the assessed dispersion method are defined according to [30]. This process has been adapted to a small pilot plant size, in line with the considerations made for CNTs lab-scale production. Results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Dispersion process (surfactant-assisted ultrasonication) [30].

Use of Data

The elementary flows used to represent the consumptions and emissions detailed in the previous section, for Model A and Model B, have been included in Table 5.

Impact Scores Corresponding to MWCNTs Production

As an intermediate calculation, the obtained impacts to produce 1 kg of MWCNTs, which is one of the raw materials necessary to produce Model A, are presented in Table 6 and Table 7. These impact scores have been calculated with the consumptions obtained in Table 2 and Table 3 and applying [58] (CML 2016) impact category characterisation factors to the corresponding elementary flows, represented in Table 4.

Table 6.

Model A. Impact scores for 1 kg of catalyst production (Ion on Zeolite powder).

Table 7.

Model A. Impact scores for 1 kg of MWCNTs.

3. Results

As explained in precedent paragraphs, the adopted functional unit is 1.00 m2 of a water tank wall made of in situ reinforced concrete. The reference scenario, Model A, is an MWCNTs-based reinforced concrete, and Model B is a conventional reinforced concrete. As the assessed functional unit is a cast on site water tank wall, the assessed stages include the production stage, A1 to A3, and the construction stage, A4 and A5. The obtained impact scores corresponding to Model A and Model B are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

LCA for Functional Unit. Models A and B.

In Table 8, Model A and Model B scores are considered equal for Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels) as they differ by 0.5%. Furthermore, for Human toxicity, Photochemical oxidation, Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels), Global Warming, Eutrophication, and Acidification, Model A showed substantially lower scores than Model B, with differences that range from 23.31% for Human toxicity to 9.75% for Acidification. Conversely, for the ozone layer depletion category, Model A scores are slightly larger than Model B, with a 3.24% difference. Consequently, it can be concluded that Model A, MWCNT-based reinforced concrete, clearly shows a better environmental performance than the conventional Model B, according to the conducted cradle to construction site LCA study.

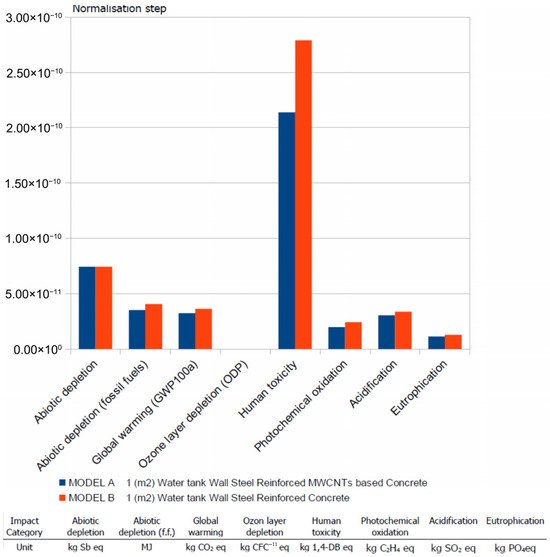

3.1. Normalisation Step

In this study, the Normalisation step has been applied to the obtained results. The LCA Methodology [50,57] defines the Normalisation step as an optional tool that is used to improve the interpretation of the obtained impact scores, as mentioned in Section 2.2.3. This step shows the relative contribution of the calculated impact scores to the total score for the corresponding impact category at the regional level. In this calculation, the scores obtained for each impact category (see Table 8) are divided by the corresponding normalisation factor, which is included in CML EU25+3, to obtain the normalised score for each category.

CML EU25+3 Normalisation factors represent the impacts produced within European Union countries during the year 2000 [59,60]. It has to be stressed that the obtained normalised scores cannot be applied in the weighting calculation; therefore, it is not possible the direct comparison of the obtained normalised scores for the different impact categories. In conclusion, the obtained normalised scores are used to calculate the contribution of the assessed product system to the total yearly environmental impacts for this region. Figure 5 presents the normalised scores obtained for the assessed functional unit.

Figure 5.

Normalised impacts for F.U. (1 m2 reinforced concrete wall tank). Models A and B.

In Figure 5, it can be observed that the impact category with the highest contribution is Human toxicity. For this category, the obtained scores for Model A are significantly lower than for Model B, with differences of over 20%. For the second category, Abiotic depletion, results show differences below 0.5%, and consequently, they are considered equal. Furthermore, for Photochemical oxidation, Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels), Global Warming, Eutrophication, and Acidification, Model A obtained impact scores are lower. With differences that range from 18.7% for Photochemical oxidation to 9.75% for Acidification.

In conclusion, the impact scores for the reference scenario Model A show the lowest values in the most relevant impact categories, an equivalent score in the second relevant category, and slightly higher scores in the least relevant category. Therefore, it can be concluded that Model A, MWCNT-based reinforced concrete, shows a better environmental performance than the conventional Model B, according to the conducted cradle to construction site LCA study.

As an additional interpretation tool, CML EU25+3 Normalisation factors were divided by the EU25+3 population [62]. The results represent the average total impacts corresponding to each individual in Europe during the year 2000. The obtained impacts and the corresponding CML EU25+3/population are shown in Table 9. These figures enable the comparison of the obtained impact to the average annual impact corresponding to each individual (Ind. Impact). In Table 9, the conclusions are equal to the Normalisation step. The more relevant impact categories are Human toxicity, Abiotic depletion (f.f.), Global Warming, Acidification, Photochemical oxidation, and Eutrophication. Model A scores in all these categories are lower than Model B, except for Abiotic depletion. For this category, the difference between Models A and B is below 0.5%; thus, it is considered negligible. On the other hand, for ozone layer depletion, the Model B score is slightly below Model A, as commented in the preceding paragraph.

Table 9.

Comparison of the obtained scores to the average yearly impact corresponding to each individual. (*) (Indv. Imp. = CML EU25+3/population).

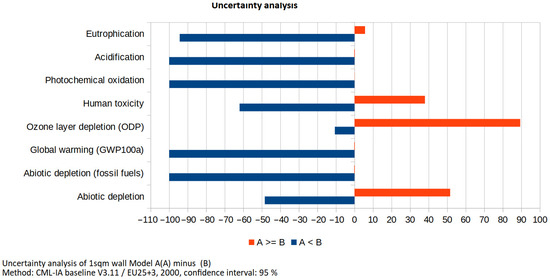

3.2. Uncertainty Assessment

All data in LCA models have some uncertainty. In this study, an uncertainty analysis has been performed with the Simapro tool, Monte Carlo. Monte Carlo analysis is a numerical method for processing uncertainty data and establishing an uncertainty range in the obtained results. In the Monte Carlo approach, the computer takes a random variable for each value within the specified uncertainty range and recalculates the results. This calculation is repeated by taking different samples within the uncertainty range. Each result is stored. It is advisable to repeat the procedure 1000 times to obtain an adequate approach [51]. The results presented in Figure 5 were assessed using a Monte Carlo simulation. The results are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Uncertainty analysis. Model A and Model B.

Table 10 provides the Standard Deviation (SD) and the coefficient of variation (CV) of each category score for 1000 Monte Carlo runs. The SD is a measure of the variation relative to the mean value of a dataset, while the CV is the percentage of the mean value represented by the SD. It can be observed that the value of SD is lower for Acidification, ozone layer depletion, and Global Warming, with the corresponding CV being approximately 10% of the mean value. This indicates that the uncertainty of the results is low for these categories. Conversely, for Human toxicity, the SD value is more than ten times higher than for the other impact categories; therefore, the uncertainty of the obtained results is high. These results are consistent with those published in [63,64,65]. As outlined in the reviewed research, the uncertainty obtained is generated by the quality of the data used—in this case, data included in Ecoinvent—and the characterisation factors included in the LCA method used, as mentioned in [65,66]. Furthermore, ref. [65] comments on the large uncertainty in the toxicity impact category characterisation factors.

Finally, a Monte Carlo assessment is presented as a graphic showing the number of runs in which product A is larger than product B, in order to assess the uncertainty in the comparison of the two different models. In general, it is assumed that if 90% to 95% of the Monte Carlo runs are favourable for a product, the difference may be considered significant [51]. Figure 6 presents a Monte Carlo comparison graphic.

Figure 6.

Uncertainty analysis. Comparison of Model A and Model B runs.

Figure 6 shows that the scores for Model A are lower in most impact categories with sufficient confidence, as the value A < B is above 90% of runs. It is noted that for ozone layer depletion, the scores are lower for Model B, with enough confidence as the value A ≥ B is above 90% of runs. In addition, for the impact of Abiotic depletion, both results A < B and B < A are balanced. This is an expected result as the obtained impact scores have differences below 0.5%, and this difference falls within error margins. Finally, neither option is above the 90% runs for Human toxicity, despite Model A scores being more than 20% lower than Model B. This reflects the uncertainty attached to the Human toxic category in the adopted CML-IA method.

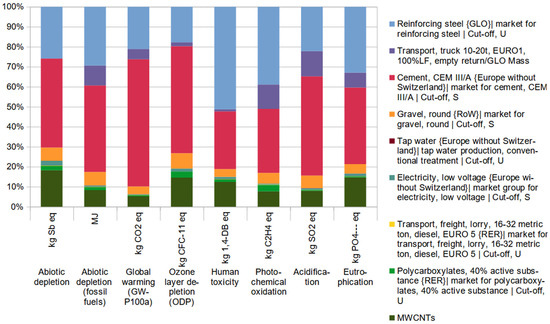

3.3. Contribution Analysis

In line with [50,57], a contribution analysis has been performed to assess the reference scenario Model A. In Figure 7, the relative contribution of all elementary flows included in the Impact calculation for Model A is represented. These results correspond to 1 m2 of Water Tank Wall made of Reinforced Steel MWCNT-based Concrete, as shown in Table 8.

Figure 7.

Contribution analysis for F.U. (1 m2 reinforced concrete wall tank). Model A.

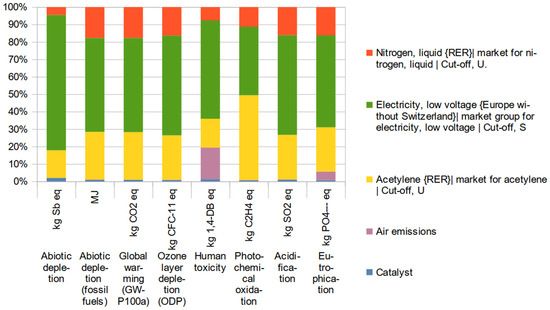

Globally, the most relevant processes are steel reinforcement, cement, and MWCNT production. It has to be noticed that the flows corresponding to the transportation to the construction site of mixed Cement, Sand, Steel, and Tap water are common for Model A and Model B. Therefore, the specific flows corresponding to the production of MWCNT-based concrete are the MWCNT production, its transportation to the concrete plant, and the polycarboxylates and electricity used in the dispersion process. Out of these specific processes, it is observed that the most relevant scores correspond to the production of MWCNT. Figure 8 shows the contribution analysis of the assessed MWCNT production process.

Figure 8.

Contribution analysis for 1 kg MWCNTs production.

For the MWCNTs assessed production process, the use of electricity makes the largest contribution. This is coherent with the results included in the reviewed bibliography [18,23], which remark that impacts for electricity use represent an average of 80% of the Global Warming Potential impact scores. Therefore, according to above mentioned results, a substantial environmental improvement can be achieved by reducing electricity consumption.

According to Figure 7, two transport processes have been assessed: one from the MWCNT production facility to the concrete plant, and the other is the transportation of all concrete elements from the concrete plant to the construction site. The transportation of all concrete components to the construction site is a fixed distance, as it corresponds to the maximum length of time allowed for transportation of the fresh concrete in a mixing truck. As a consequence, the only alternative transport scenario can be established for the transportation of MWCNTs. This is a small weight, so there is no room for a significant impact score reduction.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

According to the recommendations included in ISO 14044 and ILCD standards [50,57], it has been conducted a sensitivity analysis, for Model A most relevant specific flow, which is the use of electricity, as explained in the previous section. Furthermore, although the specific transport flow variation in Model A is not expected to significantly influence the final impact scores, an alternative scenario was defined, considering a national range of distances for the MWCNTs production facility.

3.4.1. Sensitivity Analysis for Electricity Use

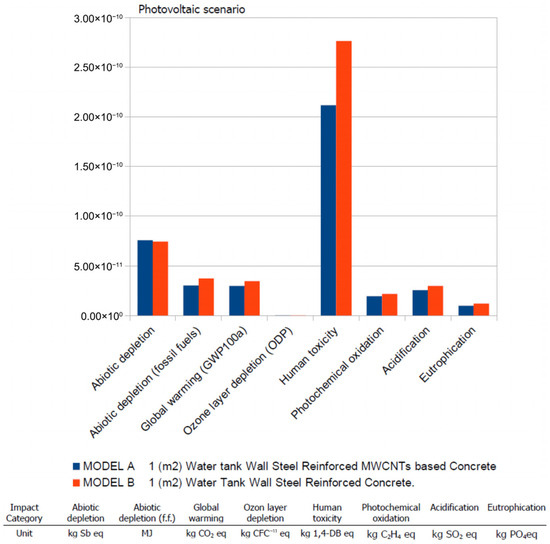

In the case of electricity consumption sensitivity analysis, an alternative best scenario has been considered, where all the energy used is photovoltaic. To evaluate this alternative scenario, it has been used the cradle to grave impacts included in the environmental product declaration (EPD) corresponding to 1.00 kWh produced in a Photovoltaic Plant in Europe [67] was used. The use of Photovoltaic electricity defined in this scenario is in line with the current economic trends in southern European countries. The Following Table 11 presents the comparison of Model B and Model A impact scores applying the use of 100% Photovoltaic electricity.

Table 11.

Impact scores comparison Model A to Model B. Sensitivity analysis. A total of Photovoltaic electricity is used.

This table shows a clear environmental improvement for Model A in all impact categories with a meaningful contribution, as its scores are lower than those of Model B. For the Abiotic depletion category, the impact can be considered equal in both categories as the difference is below 2%. The only case in which Model A’s impact score is higher than Model B is ozone layer depletion, which bears a negligible contribution, as shown in Figure 9. The observed differences range from 23.5% for Human toxicity to 11.1% for Photochemical oxidation. The normalised scores corresponding to this sensitivity analysis are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis. A total of 100% photovoltaic electricity is used. Normalised impacts for F.U. (1 m2 reinforced concrete wall tank). Models A and B.

In comparison with the national electricity mix, the photovoltaic electricity scenario shows negligible differences for Human Health, which is the most influential category. On the other hand, a slight improvement can be observed for the remaining influential categories, ranging from 10% for Eutrophication, 5% for Abiotic depletion of fossil fuels and Acidification, and finally, 1% for Global Warming. Finally, Model A shows a significantly better environmental performance than Model B for the 100% photovoltaic electricity use scenario. However, it only yields a moderate improvement compared with the national mix electricity scenario.

In the calculation of this scenario, the direct data corresponding to one product EPD was used. There is no available uncertainty data for this EPD. Consequently, the uncertainty analysis of this sensitivity scenario cannot be generated.

3.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis Transport Use

In this section, it has been assessed an alternative worst-case scenario for the transportation of the used MWCNTs, from the producer facility to the concrete plant. In this scenario, the considered distance is changed from the considered 85 km, provincial range, to 500 km, national range. Currently, this is a probable scenario for European countries. Table 12 shows the variation in Model A impact scores due to the consideration of a 500 km distance for used MWCNTs transportation.

Table 12.

Model A. 1.00 m2 of reinforced MWCNT-based concrete water tank wall. Sensitivity analysis. Impact variation for 500 km for MWCNTs transportation distance.

Table 11 shows that all impact scores are higher as the transportation distance has been increased. However, the nearly six-fold increase in the considered distance produced an impact score increase lower than 1.00% in all impact categories. Therefore, as expected, it can be concluded that the transportation distance for the used MWCNTs is not influential regarding Model A obtained impact scores

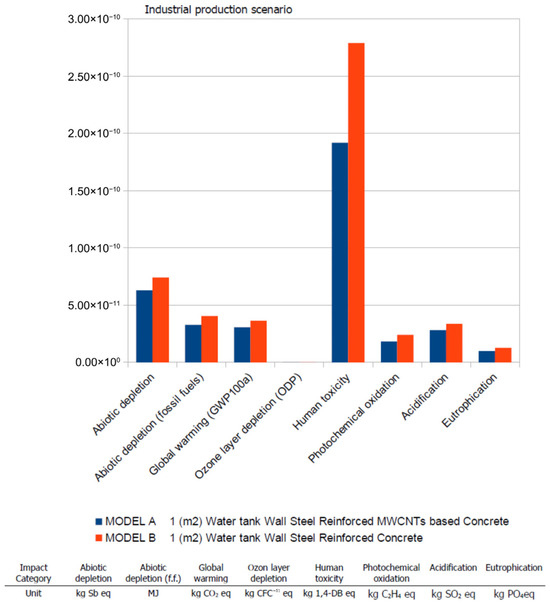

3.4.3. Considerations Regarding MWCNTs Industrial Production Process

It should be noted that nanoparticles industrial production is a novel field, and the companies involved do not disclose the corresponding data, as mentioned in Section 1. Therefore, recently published LCA studies rely on data obtained from laboratory or pilot-scale production plants. Published research considers that these data do not represent the actual impacts of current industrial production, which is estimated to have already been substantially optimised. In this regard, the reviewed research estimations consider an average reduction factor of 6.5 for industrial production in all impact category scores [27]. Considering that this study is a comparative LCA of a novel product, Model A, with a conventional one, Model B, obtaining a good approximation to the actual expected data corresponding to the industrial scale production for the assessed Model A is essential. To achieve this target, a reduction factor has been applied to the obtained impact scores corresponding to MWCNT production according to reference [26]. These factors represent the expected impact reduction for MWCNT production scaling up using a patented CVD process.

Figure 10 presents the obtained Normalised impact scores corresponding to the scaling up to industrial production of MWCNTs, according to reference [26].

Figure 10.

Scaling up of results according to the reviewed research. Normalised impacts for F.U. (1 m2 reinforced concrete wall tank). Models A and B.

The resulting normalised impact scores for Model A and Model B, once the scaling up to the industrial production scenario is applied, show lower impact scores for Model A in all assessed categories. As shown in Table 13, the differences in the most influential categories are 31.27% for Human toxicity, 15.28% for Abiotic depletion, 19.56% for Abiotic depletion of fossil fuels, and 15.39% for Global Warming Potential. Therefore, the application of the scaling-up factors significantly reduces all impact scores.

Table 13.

Impact scores comparison MODEL A to MODEL B. Scaling up of results according to the reviewed research.

It is noted that this scenario has been defined by applying reduction factors to the obtained impact scores, following reference [26]. Consequently, it is not possible to define an uncertainty analysis for it.

4. Discussion

The current regulation to design waterproof reinforced concrete has been implemented to calculate Model A, which is 1 m2 of a water tank wall made of a hypothetical MWCNT reinforced concrete. The comparison of Model A with a conventional reinforced concrete wall, Model B, resulted in a 47% steel weight use reduction. This is consistent with current efforts to reduce the huge impacts associated with using reinforced concrete [6]. To evaluate the environmental benefits corresponding to this steel saving, a comparative cradle-to-construction-site LCA was performed. In this analysis, the Normalisation step, Section 3.1, shows that the obtained score for the most influential impact categories is substantially lower in Model A than Model B, with differences over 20% for Human health, 18.7% for Photochemical oxidation, and around 10% for Global Warming, Abiotic depletion f.f., Eutrophication, and Acidification. For the second most influential category, Abiotic depletion, the results are considered equal. Only for the least influential category, which is ozone layer depletion, the Model B score is lower than Model A. In addition, the uncertainty assessment of Model A and B comparison presented in Figure 6 shows that scores for Model A are lower in most impact categories with sufficient confidence. The exceptions are that the scores for ozone layer depletion are lower for Model B, with sufficient confidence, and for Abiotic depletion, the results A < B, and B < A are balanced. Consequently, according to the LCA performed, Model A shows a substantially better environmental performance than the conventional reinforced concrete, Model B.

Furthermore, the most influential flow in the performed contribution analysis was the use of electricity, apart from the use of cement and steel reinforcement, which are common in Models A and B. This is a consequence of the use of MWCNT because, as shown in Figure 8, electricity is the main consumption flow in MWCNT production. This is consistent with the reviewed research [23]. Following this result, it has been performed a sensitivity analysis was performed, considering the use of 100% photovoltaic-generated electricity. The scores obtained for this scenario (Section 3.4.1) only yield moderate improvement compared with the national electricity mix scenario. This result suggests that the use of cement and steel has the greatest impact on the final score, while variations in electricity consumption only influence the final result moderately.

Together with this, it has been established that the only specific flow for Model A regarding transportation is the one referred to the weight of MWCNTs being taken from the producer facility to the concrete plant. Although this weight is a very small amount, a sensitivity analysis was performed. The results show that despite increasing the distance by almost six-fold, the scores obtained only show variations below 0.5% for all impact categories. Therefore, it is concluded that transportation of used MWCNTs is not a core flow for the assessed functional unit.

As this study is a comparative LCA of a novel product, Model A, with a conventional industrialised product, Model B, a good approach to the actual industrial production data of MWCNTs is essential. To achieve this goal, the parameters corresponding to the scaling up, from the considered pilot plant level to an industrial production scale, have been used, following reviewed research results [26]. The assessment of this industrial production scenario (Section 3.4.3) shows that Model A scores are substantially lower in all assessed impact categories. In conclusion, Model A shows an additional improved environmental performance than Model B for this scenario.

In conclusion, the results of the comparative LCA conducted on Model A and Model B show that the steel savings in Model A outweigh the corresponding impacts of using MWCNTs. This outcome is in line with the reviewed research [21], as the used nanoparticles are a very small proportion of the water tank wall mass. Furthermore, this environmental benefit has been identified because the functional unit of the conducted comparative LCA refers to the function of Model A. Conversely, published nanoproducts LCA studies usually are focused on the mass unit production process [42,43].

Finally, the uncertainty attached to this LCA analysis (Section 3.2) has been assessed, and the results show a large dispersion in the score corresponding to Human toxicity. This is due to the data used (Ecoinvent) and the characterisation method employed. This outcome is consistent with the reviewed research [63,64,65]. Additionally, it has to be mentioned that LCA is the method of consensus to evaluate the environmental impacts of nanoproducts [43]. However, current research has reported that LCA characterisation factors are not adapted to evaluating nanoparticle emissions into the environment, and that LCA inventories do not include these emissions [42,43]. Consequently, current LCA characterisation methods misrepresent Human health impacts.

The results obtained in this study only include the cradle to construction site phases, as the data corresponding to the use and end-of-life phases of nanoparticles is scarce or non-existent. Furthermore, the LCA study was defined for the geographical range of Europe 27. In the case that this study were applied to other regional areas, the results might be different. Similarly, the inclusion of use and end-of-life phases could modify the results obtained.

5. Conclusions

This research focuses on the evaluation of MWCNT-based concrete to reduce the environmental impacts associated with the expected increase in the construction of water management facilities. To assess the associated environmental benefits of MWCNT-based concrete use, it has been conducted a cradle to construction site comparative LCA study has been conducted. The adopted Functional Unit is 1.00 m2 of cast in situ, steel-reinforced concrete wall of a water tank, which is a frequently used element in grey water management facilities. This element has been designed with a hypothetical steel-reinforced MWCNT-based concrete (Model A) and a hypothetical conventional reinforced concrete (Model B). For the design of both models, the current compulsory regulation in EU countries, ref. [47] has been followed. For the MWCNT-based concrete, the data corresponding to carbon nanotube production have been obtained from reference [23,44], and for the necessary dispersion process from reference [30]. For the enhanced mechanical properties of the MWCNT-based concrete, data have been obtained from reference [45]. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

- The calculation of the assessed functional unit shows a 47% reduction in the use of steel reinforcement for Model A.

- The obtained results show a better environmental performance for MWCNT-based concrete, Model A, as the obtained impact scores are clearly lower for the most relevant impact categories. Therefore, the steel use reduction outweighs the impacts associated with the use of MWCNTs.

- The contribution analysis performed for Model A established that electricity is the core flow for the MWCNTs production process. In contrast, the assessed alternative scenario for 100% use of photovoltaic electricity only shows a moderate improvement. This indicates that the impacts corresponding to the use of MWCNT are much lower than the impacts corresponding to the other two main contributors, which are the use of cement and steel.

- To obtain an appropriate estimate of the environmental impacts associated with the current industrial production of MWCNTs, the reduction factors included in [26] were applied. The results obtained for this industrial production scenario demonstrate an improvement in the environmental performance of Model A. This approach is considered to provide a more accurate representation of the current nanoparticle market.

- The conducted uncertainty analysis shows a great dispersion in Human toxicity results. This is in line with the reviewed research. Together with this, nowadays LCA is the method of consensus to evaluate nanoproducts environmental performance. However, research has reported shortcomings regarding this method that affect the evaluation of the Human toxicity impact category.

In conclusion, the comparative LCA conducted on the hypothetical MWCNT reinforced concrete (Model A) shows a better environmental performance than the conventional (Model B). Consequently, the use of steel-reinforced MWCNT-based concrete can mitigate the huge environmental impacts associated with the expected increase in the construction of water management facilities. It is noted that nanoproducts are a novel field, and the definition of a regulation on the composition and mechanical characteristics of MWCNT concrete is necessary prior to the commercial use of these new construction materials. Finally, the use of this MWCNT is recommended in water management grey facilities only on an environmental basis. As this study does not include economic criteria, further research is required to assess the economic viability of this proposal.

Together with this, future research should be focused on establishing the actual consumptions and emissions of current MWCNTs industrial production processes, and to assess the optimisation of MWCNT-based concrete mixing processes and proportions, as well as enhancing LCA methods to address current knowledge gaps concerning nanoparticles assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15162818/s1, reference [68].

Author Contributions

M.A.S.-B.: Reinforced concrete modelling, nanoparticles data, LCA modelling, Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, visualisation, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. A.-F.T.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Validation, Supervision; P.M.-M.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is co-funded by the European Union and within the framework of an initiative of 2022 KA220, co-operation partnerships in higher education, with the support of the “Servicio Español para la Internacionalización de la Educación” (SEPIE, Spain): 2022-1-ES01-KA220-HED-000089985.

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Materials to this article is available. Any other data used or analysed in this study are available under reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support provided by the University of Seville, the National Technical University of Athens and the NaNoer project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pappalardo, V.; La Rosa, D. Policies for sustainable drainage systems in urban contexts within performance-based planning approaches. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Wood, H. Containing a sustainable urbanized environment through SuDS devices in management trains. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Velasco, M.J.; Esbri, O.; Medina, V.; Russo, B. The Economic Impact of Climate Change on Urban Drainage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIB Water Sector Orientation-Building Climate-Resilient Water Systems. European Investment Bank. 2023. Available online: https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/20230016_eib_water_sector_orientation_en.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Tondera, K.; Brelot, E.; Fontanel, F.; Cherqui, F.; Nielsen, J.E.; Brüggemann, T.; Naismith, I.; Goerke, M.; López, J.S.; Rieckermann, J.; et al. European stakeholders’ visions and needs for stormwater in future urban drainage systems. Urban Water J. 2023, 20, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.; Kumar, M.S. An overview of environmental sustainability in cement and steel production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tautorat, P.; Lalin, B.; Schmidt, T.S.; Steffen, B. Directions of innovation for the decarbonization of cement and steel production–A topic modeling-based analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ryberg, M.; Yang, Y.; Feng, K.; Kara, S.; Hauschild, M.; Chen, W.Q. Efficiency stagnation in global steel production urges joint supply- and demand-side mitigation efforts. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantini, A.; Leoni, L.; De Carlo, F.; Salvio, M.; Martini, C.; Martini, F. Technological energy efficiency improvements in cement industries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, T.; Engvall, J. Evaluation of Usage of Plasma Torches in Cement Production—A Heat Transfer Modelling Study. Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Olabi, A.G.; Wilberforce, T.; Elsaid, K.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Large scale application of carbon capture to process industries—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Bishnoi, S.; Martirena, F.; Scrivener, K. Limestone calcined clay cement and concrete: A state-of-the-art review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 149, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.T.M.; Velenturf, A.P.M.; Bernal, S.A. Circular Economy strategies for concrete: Implementation and integration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, A.; Karakaya, E.; Urban, F. Enabling the transition to a fossil-free steel sector: The conditions for technology transfer for hydrogen-based steelmaking in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, H.; Umeki, K.; Mousa, E.; Hedayati, A.; Romar, H.; Kemppainen, A.; Wang, C.; Phounglamcheik, A.; Tuomikoski, S.; Norberg, N.; et al. Use of biomass in integrated steelmaking e status quo, future needs and comparison to other low-CO2 steel production technologies. Appl. Energy 2018, 213, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Nurni, V.N.; Tathavadkar, V.; Basu, S. A review on the generation of solid wastes and their utilization in Indian steel industries. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. 2017, 126, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila Temizel-Sekeryan Fan Wu Andrea, L. Hicks. Global scale life cycle environmental impacts of single and multi-walled carbon nanotube synthesis processes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsev, T.; Tiza, T.M.; Mogbo, O.; Singh, S.K.; Chakravarti, A.; Shaik, N.; Singh, S.P. Application of nanomaterials in civil engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 5140–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Mehta, A. Effect of carbon nanotubes on properties of cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumari, B.Y.; Swaminathan, E.N.; Partheeban, P. A review on characteristics studies on carbon nanotubes-based cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.A.; Sadeghi-Nik, A.; Bahari, A.; Jin, C.; Ahmed, R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; de Brito, J. Strength optimization of cementitious composites reinforced by carbon nanotubes and Titania nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 303, 124510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Z.; Temizel-Sekeryan, S.; Ghamkhar, R.; Hicks, A.L. Assessing the environmental impact and payback of carbon nanotube supported CO2 capture technologies using LCA methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Fthenakis, V. Life Cycle Energy and Climate Change. Implications of Nanotechnologies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teah, H.Y.; Sato, T.; Namiki, K.; Asaka, M.; Feng, K.; Noda, S. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Long and Pure Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized via On-Substrate and Fluidized-Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavankar, S.; Suh, S.; Keller, A.A. The Role of Scale and Technology. Maturity in Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Technologies. A Case Study on Carbon Nanotubes. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinno, F.; Hischier, R.; Seeger, S.; Som, C. Predicting the environmental impact of a future nanocellulose production at industrial scale: Application of the life cycle assessment scale-up framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Z.; Hicks, A.L. Life Cycle Impact of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle Synthesis through Physical, Chemical, and Biological Routes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4078–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aodkeng, S.; Sinthupinyo, S.; Chamnankid, B.; Hanpongpun, W.; Chaipanich, A. Effect of carbon nanotubes/clay hybrid composite on mechanical properties, hydration heat and thermal analysis of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, M.O.; Taha, R.; Abu Taqa, A.; Shaat, A. Optimum carbon nanotubes’ content for improving flexural and compressive strength of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reales, O.A.M.; Toledo Filho, R.D. A review on the chemical, mechanical and microstructural characterization of carbon nanotubes-cement based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsta-Gdoutos, M.S.; Aza, C.A. Self sensing carbon nanotube (CNT) and nanofiber (CNF) cementitious composites for real time damage assessment in smart structures. Cem Concr Compos. 2014, 53, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawreen, A.; Bogas, J. Creep, shrinkage and mechanical properties of concrete reinforced with different types of carbon nanotubes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 198, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesmawala, G.R.; Vaghela, A.R.; Yadav, K.; Patil, Y. Effectiveness of polycarboxylate as a dispersant of carbon nanotubes in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1170–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsta-Gdoutos, M.S.; Metaxa, Z.S.; Shah, S.P. Multi-scale mechanical and fracture characteristics and early-age strain capacity of high performance carbon nanotube/cement nanocomposites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Nam, I.; Yang, B.; Yoon, H.; Lee, H.; Park, S. Carbon nanotube (CNT) incorporated cementitious composites for functional construction materials: The state of the art. Compos. Struct. 2019, 227, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yu, X.; Ou, J. Effect of water content on the piezoresistivity of MWNT/cement composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 3714–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Duan, Z.; Li, H. The influence of surfactants on the processing of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in reinforced cement matrix composites. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2009, 206, 2783–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, F.; Lambert, J.; Duan, W.H. The influences of admixtures on the dispersion, workability, and strength of carbon nanotube–OPC paste mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Study of the EU Market for Nanomaterials, Including Substances, Uses, Volumes and Key Operators. European Chemicals Agency. 2022. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2823/680824 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Kim, M.; Goerzen, D.; Jena, P.V.; Zeng, E.; Pasquali, M.; Meidl, R.A.; Heller, D.A. Human and environmental safety of carbon nanotubes across their life cycle. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 9, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salieri, B.; Turner, D.A.; Nowack, B.; Hischier, R. Life cycle assessment of manufactured nanomaterials: Where are we? NanoImpact 2018, 10, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, N.U.M.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Woon, K.S. A Content Review of Life Cycle Assessment of Nanomaterials: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompeta, A.-F.; Koklioti, M.A.; Perivoliotis, D.K.; Lynch, I.; Charitidis, C.A. Towards a holistic environmental impact assessment of carbonnanotube growth through chemical vapour deposition. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 384e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshidat, M.R. Bond strength evaluation between steel rebars and carbon nanotubes modified concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, e00477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1990:2002/A1; Eurocode-Basis of Structural Design. European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1992-1-1; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2004.

- Evangelista, A.C.J.; de Morais, J.F.; Tam, V.; Soomro, M.; Di Gregorio, L.T.; Haddad, A.N. Evaluation of Carbon Nanotube Incorporation in Cementitious Composite Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006(en); Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management. Life Cycle Assessment. Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Goedkoop, M.; Oele, M.; Vieira, M.; Leijting, J.; Ponsioen, T.; Meijer, E. SimaPro Tutorial; PRé Sustainability, B.V.: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EN 15804:2012+A2:2019; Sustainability of Construction Works-Environmental Product Declarations-Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2019.

- Ecoinvent Database. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org/database/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Li, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Yuan, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, C. Commercial activated carbon as a novel precursor of the amorphous carbon for high-performance sodium-ion batteries anode. Carbon 2018, 129, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.-H. Full graphitization of amorphous carbon by microwave heating. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 24667–24674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14025:2006(en); Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type III Environmental Declarations—Principles and Procedures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- EUR 24708 EN-2010; ILCD Handbook, International Reference Life Cycle Data System. IES, JRC, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- CML-IA Characterisation Factors. 2016. Available online: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/research/research-output/science/cml-ia-characterisation-factors (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Sleeswijk, A.W.; van Oers, L.F.; Guinée, J.B.; Struijs, J.; Huijbregts, M.A. Normalisation in product life cycle assessment: An LCA of the global and European economic systems in the year 2000. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 390, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsioen, T. Pré Sustainability 2014. Normalization: New Developments in Normalization Sets. 2014. Available online: https://pre-sustainability.com/articles/the-normalisation-step-in-lcia/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Coal Explained. Coal and the Environment. U.S. Energy Information Administration. Independent Statistics and Analysis. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/coal/coal-and-the-environment.php#:~:text=Several%20principal%20emissions%20result%20from,respiratory%20illnesses%2C%20and%20lung%20disease (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EUROPE IN FIGURES—Eurostat Yearbook July 2006. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/5609869/KS-CD-06-001-01-EN.PDF/ebb28696-2f37-4d37-87c9-e6ac574329c0?version=1.0 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Chen, X.; Matthews, H.S.; Griffin, W.M. Uncertainty caused by life cycle impact assessment methods: Case studies in process-based LCI databases. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 172, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, G.; Hellweg, S.; Hungerbühler, K. Uncertainty Analysis in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Case Study on Plant-Protection Products and Implications for Decision Making. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2005, 10, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-L.; Ma, H.-W. Quantifying system uncertainty of life cycle assessment based on Monte Carlo simulation. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2009, 14, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahmand, Z.; Eikeland, M.S. Life Cycle Assessment under Uncertainty: A Scoping Review. World 2022, 3, 692–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPD Italy. The Norwegian EPD Foundation. DMEGC Bifacial Monocrystalline Photovoltaic Module (N-type cells). In Accordance with ISO 14025. Jiangsu Dongci New Energy Technology Co., Ltd., 2024. Available online: https://www.epditaly.it/en/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/DMEGC-EPD3_Public-report-20240126.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Montoya, P.J.; Meseguer, Á.G.; Cabré, F.M.; Portero, J.C.A. Ajustada a Código Modelo y Eurocódigo, 14th ed.; Editorial Gustavo Gili S.L.: Barcelona, Spain, 2000; ISBN 84-252-1825-X, 9788425218255. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).