Abstract

Throughout history, communities have struggled to build homes in places actively hostile to their presence, a challenge long faced by African descendants in the American diaspora. In cities across the U.S., including Washington, D.C., efforts have often been made to erase Black cultural identity. D.C., once a hub of Black culture, saw its urban fabric devastated during the 1968 riots following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Since then, redevelopment has been slow and, more recently, marked by gentrification, which has further displaced Black communities. Amid this context, Black architects such as Michael Marshall, FAIA, and Sean Pichon, AIA, have emerged as visionary leaders. Their work exemplifies Value-Inclusive Design and aligns with Roberto Verganti’s Design-Driven Innovation by embedding cultural relevance and community needs into development projects. These architects propose an intentional approach that centers Black identity and brings culturally meaningful businesses into urban redevelopment, shifting the paradigm of design practice in D.C. This collective case study (methodology) argues that their work represents a distinct architectural style, Black Modernism, characterized by cultural preservation, community engagement, and spatial justice. This research examines two central questions: Where does Black Modernism begin, and where does it end? How does it fit within and expand beyond the broader American Modernist architectural movement? It explores the consequences of the destruction of Black communities, the lived experiences of Black architects, and how those experiences are reflected in their designs. Additionally, the research suggests that the work of Black architects aligns with heutagogical pedagogy, which views community stakeholders not just as beneficiaries, but as educators and knowledge-holders in architectural preservation. Findings reveal that Black Modernism, therefore, is not only a design style but a method of reclaiming identity, telling untold histories, and building more inclusive cities.

1. Background

The concept of an American utopia was introduced by modernity, especially for Black communities. The idea was to escape the dystopian reality, even if it meant staying in one’s own house. The accomplishments of African American architects and designers have been disregarded and underappreciated for almost a century, despite the fact that their work influenced the modern United States (U.S.) architecture movement. African American architects have continuously pushed the boundaries of how people live in their built environments by encouraging creativity and experimentation. From transatlantic to European influences, from historical events to current trends, Black Modernism was a movement that was establishing itself in white society. It not only sparked amazing movements like the Harlem Renaissance, but it also made society aware of the inadequacies in black rights and the black experience. This research examines two central questions: Where does Black Modernism begin, and where does it end? How does it fit within and expand beyond the broader American Modernist architectural movement? It explores the consequences of the destruction of Black communities, the lived experiences of Black architects, and how those experiences are reflected in their designs. Black Modernism is still evolving as an artistic movement, and as a result, it produces modern art for a new generation [1].

The field of Black Modernism is underappreciated and understudied. As a result, investigating it is a useful method to assist designers in tackling difficult issues and motivating them to create architecture that expresses their own distinct narratives. In order to foster sustainability, resilience, and historic preservation in the built environment for social and judicial equity through transformation, this involves reducing the erasure of contemporary architectural sites by Black architects and designers by narrating their stories in more robust, imaginative, and long-lasting ways. Cities are complex systems of interrelated ecological, economic, and social dimensions, and therefore, addressing urban challenges requires interdisciplinary approaches that go beyond conventional urban planning [2]. Architecture can be a catalyst for changing the meaning of space, particularly in ways that challenge historical narratives and promote inclusive spatial experiences within the built environment [3]. This movement integrates the tenets of Modernist thought with the distinct experiences, histories, and esthetics of Black communities. Emerging prominently in the early 20th century, Black Modernism was fueled by the dual forces of a global Modernist ethos and the lived realities of Black individuals and communities, particularly in the U.S. and the Caribbean [4]. It reshaped the visual and material culture of Black people, contributing to new identities, artistic practices, and social spaces [5]. The importance of this movement lies in its capacity to challenge traditional cultural norms while simultaneously fostering a sense of empowerment and solidarity within marginalized communities.

The most significant new architectural and design philosophy of the 20th century was Modernism, which rejected decoration and embraced minimalism. Modernism is defined as a specific way of doing, creating, or performing something. It was linked to a methodical approach to the purpose of buildings, the logical application of frequently novel materials, structural innovation, and the removal of ornamentation. Rigid Modernist designs from the 1930s to the early 1960s have been referred to as the “Modern Movement” in Britain [6]. Black Modernism identifies how Blacks throughout the world responded to the experience of modernity, globalism, and anticolonialism as well as to the expanded sense of artistic experimentation and visibility of Black expressive culture. Places that hold a multiplicity of stories, memories, and legacies that can be told and that can empower visitors when they are interpreted and presented to the public. Black people’s intersectional relationships across different geographies, from their homelands to cosmopolitan settings, are expressed through the form. There is a periodic resurgence of interest in history, and we can trace the origins of this inspiration back to the turn of the 20th century.

In actuality, only a select few, including Max Bond, Norma Merrick Sklarek, Paul Revere Williams, and John Chase, were able to break past the restrictions throughout the Modernist era. Less is known about the contributions made by those who did not. The spatial and formal [built] manifestation of the Black cultural projects that arose for African Americans is known as black architectural modernity. It dates back to the Civil Rights Movement, Jim Crow laws, disinvestment, and carceral programs that sought to punish and control black people even after they were ostensibly free. Black people have had to consider themselves human in a world that rejects their humanity [7]. Black architectural modernity started as a process of humanization and resistance, by surviving and growing into a whole person in this hazardous environment. It has now evolved into a way of life. Racial uplift is a process that involves both striving for and achieving, as well as the manner in which our constructed environments reflect this goal. For design historians, anything that deviates from the Eurocentric white frame that permeates architectural history and practice seems to be invalid. It is then acceptable to discuss renowned Black architects like Paul Revere Williams and Robert Robinson Taylor for what makes them modern after the world forces them to deal with those issues, and they rediscover and selectively include things that they can justify in their architectural practices [7]. Black Modernism begins as an act of cultural resistance and spatial reclamation within the hostile conditions of segregation and systemic exclusion, and it continues as a living, evolving practice that redefines modern architecture through the lens of Black identity, community, and resilience both fitting within and expanding beyond the broader American Modernist movement by infusing it with narratives of liberation, cultural memory, and social justice.

1.1. Defining Black Modernism

One of the central themes in Black Modernism is the integration of art, architecture, and design as vehicles for social transformation [8]. In particular, the concept of community capacity building within design has garnered attention for its ability to strengthen and amplify the agency of communities often excluded from mainstream design and planning processes [9]. Building community capacity means not just physically constructing spaces but also fostering resilience, empowerment, and self-determination through collaborative design approaches. In the context of Black Modernism, this principle emphasizes the active role of Black communities in shaping their environments culturally, socially, and economically while resisting top-down impositions of design that fail to reflect their unique values, needs, and aspirations. What is important throughout the years is that different elements drew together and shaped the esthetic and visual language of Black Modernism. As Figure 1 illustrates, Modernism focused on envisioning the future through design and human experience; accordingly, the concept of Black Modernism evolved in parallel, shaped by the shifting dynamics of the Black experience and community during this period. The following sub-sections examine these developments in greater depth.

Figure 1.

Features of Modernist architecture. Photo credit: RIBA architecture [6].

1.2. Significance of Building Community Capacity in Design

This research examines change-meaning through architectural experiences as a radical innovative design practice for the transformation of cities and their economic development [3]. This historical investigation uncovers how the innovations of Black Architects impacted Washington, D.C. as part of the Black Modernist movement and how it is emerging today. Overall, this discussion aimed to bring into focus a previously ignored dimension of architectural inquiry and move the architectural contributions of Black Architects to the foreground. Thus, a platform from which new Black architecture can be envisioned, which transcends social, economic, political, and cultural barriers [10]. O’Hara and Naiker [2] envision cities as sites of learning and innovation, noting that “Universities must develop the capacity to place the concrete knowledge of community experts, and the knowledge of credentialed experts into dialogue.” Building community capacity in design empowers residents to actively participate in shaping their built environment, ensuring that architectural solutions reflect local needs, histories, and values. This approach fosters long-term resilience, equity, and stewardship by transforming design from a top-down process into a collaborative tool for social and spatial justice through value-inclusive design.

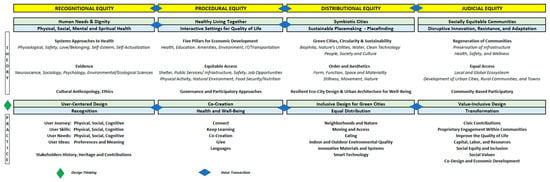

1.3. Value-Inclusive Design Principles and Intentional Design

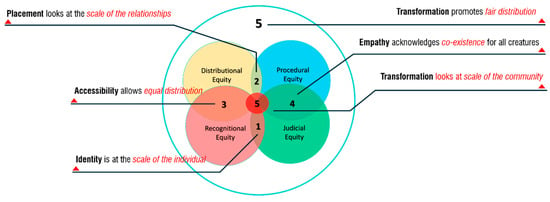

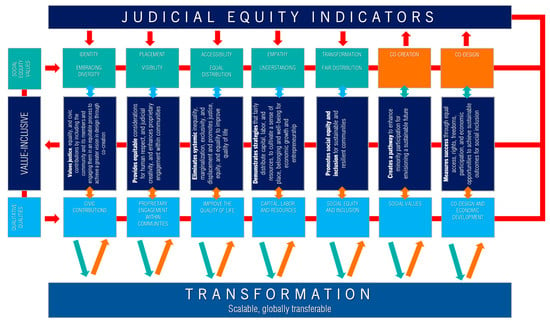

Integral to the notion of Black Modernism is the principles of Value-Inclusive Design (VID), Figure 2. These principles promote the idea that design should not only meet functional and esthetic standards but should also reflect the values, experiences, and cultural identities of diverse groups [11,12]. In this context, VID focuses on social justice, equity, and inclusivity as central tenets. For Black communities, these principles challenge the dominant Eurocentric paradigms of design, which often overlook or marginalize Black cultural expressions. By embedding cultural relevance and social equity into design, Value-Inclusive principles aim to create spaces that affirm the dignity, history, and collective identity of Black people. It therefore aims to build capacity by promoting the skills and competencies of local communities to develop, implement and sustain their own solutions and exercise control over their physical, social, economic and cultural environments This aligns with heutagogical principles, as approach the pedagogy that embraces learners as co-teachers and experts of tier own social, cultural and environmental contexts [13].

Figure 2.

Value-inclusive design model. Social value construct; 1: Identity, 2: Placement, 3: Accessibility for all, 4: Empathy, and 5: Transformation [11].

Intentional Design is a purposeful approach to creating environments, products, or systems that reflect clearly defined values, goals, and the needs of users, particularly those historically excluded from traditional design processes. It aligns closely with Value-Inclusive Design, as both prioritize equity, dignity, and cultural relevance by embedding social and environmental responsibility into every stage of the design process. Together, they ensure that design is not just functional or esthetic, but also transformative and inclusive. Building community capacity through Intentional Design and Value-Inclusive Design principles empowers communities to shape environments that reflect their values, histories, and aspirations. By embedding social construct values such as identity, placemaking, accessibility for all, empathy, and transformation, design becomes a collaborative tool that fosters resilience, inclusion, and cultural continuity. Creating social equity and inclusion in Black Modernism through Intentional Design practices involves centering Black cultural narratives, community engagement, and spatial justice to reimagine the built environment as a vehicle for dignity, resilience, and collective empowerment.

This paper builds on the Value-Inclusive Design (VID) framework by demonstrating how its core principles, identity, accessibility, empathy, and transformation, can be operationalized in architectural design and urban development. Through a collective case study and analysis, it shows how VID is not just theoretical but actively shapes the built environment when applied through an intentional design process. The projects of Michael Marshall and Sean Pichon serve as compelling examples of VID in practice, as they intentionally embed cultural identity, community engagement, and social equity into every phase of their design work.

1.4. Black Modernism and the Emergence of Its Cultural and Architectural Legacy

A review of the literature on Black Modernism indicates that the topic emerged as a response to cultural and racial exclusions from mainstream Modernist movements in art, architecture, and design. Rooted in the socio-political upheavals of the early 20th century and crystallizing during the Harlem Renaissance (1918–1937), Black Modernism became an esthetic and ideological framework for African American creatives to assert their identity and agency. Black Modernism was both a rejection of Eurocentric artistic norms and a reimagining of modernism through the lens of African American identity and experience. Gates and McKay [14] identify the Harlem Renaissance as the “birthplace” of Black Modernism, where writers, painters, and musicians used Modernist forms to explore Black consciousness, heritage, and resistance. The Black Modernist movement was deeply influenced by African American history and culture. Black art’s subject focus, form, and purpose were influenced by slavery, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and the Civil Rights Movement. For example, the collage method of Romare Bearden, which combines figuration and abstraction, is interpreted as a metaphor for the fractured yet resilient Black experience in America [15]. Similarly, jazz and blues heavily influenced the rhythmic and improvisational qualities of Black visual and spatial design. Paul Gilroy’s concept of the “Black Atlantic” (1993) helps explain how Black cultural production in the Americas, particularly in design and architecture, has always drawn from a diasporic dialog, connecting African traditions with New World realities [16]. Architecturally, the movement found expression through figures who defied segregation and institutional barriers to leave a lasting imprint on the built environment, as depicted in Figure 3. Paul R. Williams, a prolific Los Angeles-based architect, designed thousands of buildings during a career that spanned much of the 20th century. Despite facing overt racism, including having to learn to draw upside down so he would not have to sit next to white clients, Williams developed a style that merged classical modernism with the needs and esthetics of Black and white communities alike [17]. Earlier trailblazers like Robert Robinson Taylor, the first Black architect accredited in the U.S., helped shape educational environments at Tuskegee University, blending classical architectural design with the mission of racial uplift [18].

Figure 3.

Features of Black Modernist architecture. Photo credit: Shutterstock [19].

Black architects and designers often worked in and for communities that were systematically excluded from the mainstream, leading to an approach rooted in service, empowerment, and resilience. As Borchert [20] notes in her study of John A. Lankford, one of the first licensed Black architects, architecture was not just a profession but a vehicle for building Black institutions and spaces of autonomy. This was evident in structures like churches, schools, and mutual aid halls, which became anchors of social and political life in Black neighborhoods as depicted in Figure 4. Contemporary Black architects and designers are pushing this legacy forward by integrating social justice, innovation, and cultural memory into their work. Walter Hood, for example, is renowned for landscape architecture that weaves together history, ecology, and African American narratives. His designs for places like the Oakland Museum and the International African American Museum are noted for their sensitivity to both site and story [21]. Likewise, initiatives focused on design-led community development, such as cooperative housing and public space transformation, embody a forward-thinking interpretation of Black Modernism rooted in resilience and equity. Black Modernism and design innovation cannot be separated from the broader historical, social, and cultural contexts of African American life. From early pioneers like Taylor and Lankford to contemporary innovators like Hood, Black architects and designers have continually redefined the boundaries of modernism to reflect their own histories and aspirations. Their work not only critiques the limitations of mainstream design discourse but also offers visionary alternatives grounded in community, culture, and justice. Despite these strides, the destruction of Black communities had profound consequences that shaped the lived experiences of Black architects and significantly influenced the evolution of their architectural designs.

Figure 4.

The Republic Theatre (1937) was located in the heart of U Street. It was later demolished to make room for the Metro system; Image Credits: Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution [22].

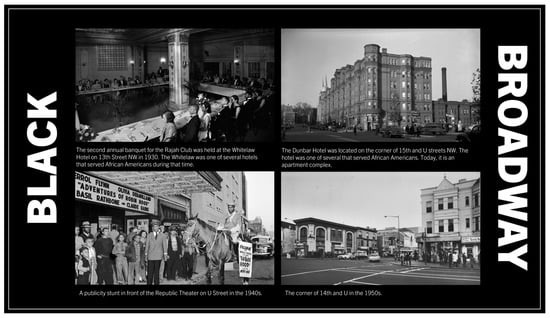

This lived experience cultivated Black Broadway as shown in Figure 5. “Black Broadway” refers to the vibrant African American cultural corridor along Washington, D.C.’s U Street N.W., particularly during the early to mid-20th century. Once dubbed the “Harlem of D.C.,” this stretch of U Street became a national center for Black music, performance, business, and civic life during a time when segregation restricted Black access to mainstream venues and institutions. Anchored by landmarks like the Lincoln Theatre and the Howard Theatre, Black Broadway nurtured the careers of musical legends such as Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, and Cab Calloway, offering a stage for Black excellence to flourish [23]. The U Street corridor was more than an entertainment district; it was a nexus of Black self-determination and resilience. During segregation, U Street thrived with Black-owned businesses, restaurants, banks, and even a hospital, Freedman’s Hospital, now Howard University Hospital. Institutions like the True Reformer Building, designed by African American architect John A. Lankford in 1903, provided space for community organizing and economic empowerment [20]. These structures served as physical embodiments of Black aspirations and resistance, challenging systemic exclusion through architectural presence and cultural visibility. Black Broadway’s significance also is tied to broader movements in urban development and civil rights. The area’s decline following the 1968 riots and its more recent gentrification raise critical questions about heritage preservation, displacement, and community memory.

Figure 5.

Black Broadway. Image credits: Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution [22]. Graphic by Author.

The 1968 race riots in Washington, D.C., following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., were a profound response to centuries of racial injustice, economic disparity, and political neglect. Sparked by grief and rage, the uprising engulfed key Black neighborhoods such as U Street, Shaw, and H Street NE, areas that had long served as cultural and economic centers for the city’s African American community. In the immediate aftermath, widespread fires and looting left over 1200 buildings damaged or destroyed, and many Black-owned businesses never reopened. While the physical damage was severe, the deeper and longer-lasting impact was the disinvestment that followed; federal and private capital withdrew, further marginalizing these communities and setting the stage for decades of neglect [24]. In the decades that followed, the vacuum created by post-riot disinvestment became fertile ground for controversial urban redevelopment projects that promised revitalization but often resulted in gentrification and displacement. The construction of the U Street Metro station in the 1980s, while ultimately improving transportation access, led to years of closed streets and disrupted access to the historic U Street corridor. This prolonged construction period forced the closure of many Black-owned businesses that had long defined the area culturally and economically, accelerating the decline of what was once known as “Black Broadway.” The disruption contributed to economic displacement and diminished the corridor’s role as a vibrant hub for the African American community. Starting in the late 1990s and accelerating into the 21st century, many of the same neighborhoods that had been devastated by the 1968 riots were targeted for luxury development, ultimately raising property values and fomenting demographic shifts. Projects in Shaw, Columbia Heights, and along the U Street corridor were promoted as urban renewal but frequently erased the very Black cultural fabric that had defined these spaces for generations. The resulting transformation, while framed as progress, has led to the displacement of long-time residents and the loss of historically significant sites, igniting ongoing debates about preservation, equity, and the right to remain in place [25]. Scholars such as Briana Thomas [26] emphasize the importance of preserving U Street’s legacy as a site of Black cultural innovation and political activism. Today, efforts to revitalize the corridor include both historic preservation and the promotion of inclusive urban design practices that honor the district’s legacy while addressing contemporary challenges.

As “blight,” the consequences of racism, segregation, and disadvantage turned into threats and obligations for the privileged, serving as a blueprint for additional exclusions of those who were already marginalized [27]. Definitions of blight have evolved dramatically throughout time, as urban historians have occasionally pointed out. However, what has not yet been highlighted is how those changes consistently have allowed communities of color to be displaced and evicted from American cities: on the one hand, blight definitions have always applied to property that is owned or occupied by people of color, and on the other hand, blight remediation has always been used to transfer property from people of color to primarily white investors, developers, or owners through the state. The people of D.C. also experienced the effects of blight, gentrification, displacement, and redlining. Despite these adversities, the movement continued to forge ahead by influencing African American culture and history.

1.5. Influences from African American Culture and History

African American culture and history significantly shaped Black Modernism. The Middle Passage, slavery, Reconstruction, the Great Migration, and the Civil Rights Movement are not only historical events but also cultural signifiers that influenced artistic production. Figure 6 depicts these elements imbuing Black Modernist expressions with a distinct sense of resilience and spirituality. As Powell notes, Black Modernism was not only about esthetics but also about the reclamation and affirmation of identity through design and representation [15]. There is a misconception that there is “not a lot” of work by women or people of color, or that it is “hard to find,” because the history of modern architecture and design in the 20th century has long focused on the individual achievements of architects and designers who were primarily white and male. However, if we broaden our definition of architecture and design to encompass everyone involved in a project, not just the lead architect, a small amount of research will produce a lot of results [28].

Figure 6.

Study for aspects of Negro life: An Idyll of the Deep South, 1934, Tempera on paper; Image Credit: Collection of David C. and Thelma Driskell [29].

1.6. Key Figures and Movements

Key figures in Black Modernism include artists and designers such as Aaron Douglas, Romare Bearden, and architects Paul R. Williams and Max Bond. Each contributed significantly to a Modernist expression that was rooted in African American identity. Aaron Douglas, for example, infused African motifs and Modernist techniques to produce works that reflected Black history and pride [30]. Paul R. Williams, often regarded as one of the most influential Black architects of the 20th century, broke racial barriers by designing elegant structures for both Black and white clients in Los Angeles and beyond [31]. Williams was a groundbreaking figure in American architecture, widely celebrated as the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and a pioneer of Black Modernism in the United States. Known as the “Architect to the Stars”, Williams designed more than 2000 homes in Southern California, including residences for celebrities such as Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball, yet his impact extended far beyond residential luxury. His work spanned public buildings, churches, and civic projects, including the iconic Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and the First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Los Angeles, showcasing his mastery of various architectural styles from Neoclassical to Streamline Moderne [32]. Williams’ ability to adapt and innovate despite the racial segregation of the era positioned him as a powerful symbol of Black excellence in the built environment. His success not only broke barriers for future generations of Black architects but also helped redefine American modernism through a distinctly inclusive and human-centered lens. As historian Karen Hudson notes, Williams “used design not only as a craft but as a means of social and cultural transformation,” embodying the ideals of Black Modernism by asserting a Black presence in elite and civic architectural spaces [17,31].

J. Max Bond, Jr. stands as a towering figure in American architecture, not only for his design excellence but also for his unwavering commitment to social justice, education, and Black empowerment through the built environment. As one of the most prominent African American architects of the 20th century, Bond broke racial barriers throughout his career, earning widespread acclaim for culturally significant projects such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta and his instrumental role in early designs for the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. [32]. His career was marked by a commitment to community-driven, humanistic design, one that challenged dominant architectural paradigms and pushed for greater inclusion of African American voices in the field. Bond’s impact extended beyond his own practice; he mentored generations of Black architects and helped create institutional pathways through his leadership roles at institutions like Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation.

Bond’s architectural worldview significantly was shaped by his time in Ghana during the 1960s, where he worked on public infrastructure and university buildings shortly after the country’s independence. This experience exposed him to a context where Blackness was not peripheral, but central to the national and cultural narrative. It profoundly altered his perception of architecture’s potential to express identity and shape civic life. In Ghana, Bond saw firsthand how architecture could be a tool for post-colonial nation-building, and this deeply informed his design ethos when he returned to the U.S. [33]. His Ghanaian work emphasized local materials, communal spaces, and symbolic forms, which later translated into his advocacy for Afrocentric and intentional design principles in American cities, including Washington, D.C. The influence of this cross-cultural engagement resonated with many younger Black architects who saw Bond’s example as a model for blending cultural heritage, modernism, and social relevance, an approach that continues to inform Black architectural practice today.

1.7. Precedents in Design and Architecture

Precedents in design and architecture were set by early African American architects who navigated systemic racism to create lasting contributions. Figures such as Robert Robinson Taylor, the first accredited African American architect and the first Black student at MIT, laid the groundwork for a generation of Black designers [18]. These pioneers operated within and outside traditional institutions, often building for segregated Black communities and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), thereby establishing a distinct design legacy. The United States is filled with Modernist buildings created by architects with well-known names such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn, and Frank Lloyd Wright. The “less is more” philosophy of these structures, which includes what were once thought to be modern building components like reinforced concrete, steel frames, and an abundance of windows and glass, is researched and commended. The style is similar in other designs by Robert Kennard (Figure 7), Harvey Gantt, Charles McAfee, and Walter Livingston Jr., but there is one notable distinction: those architects are Black. Their contributions to the field of architecture have frequently gone unnoticed. Additionally, the Conserving Black Modernism initiative, led by preservation experts to protect works by Black architects, will conclude its current phase in 2025. As part of this effort, national organizations like the National Trust and AIA will recognize eight significant buildings and a wider group of overlooked Black architects [34].

Figure 7.

Pioneering Black architect Robert Kennard led the team that designed Carson City Hall in Carson, Calif., which opened in 1976. The team also included Frank Sata and Robert Alexander [35]. Image Credit: Elon Schoenholz/Getty Foundation.

1.8. Cultural Influences

The cultural influences on Black Modernism are vast and multifaceted. Jazz, blues, and gospel music influenced the rhythm and form of visual and spatial compositions. African diasporic traditions, storytelling, and spirituality played a central role in shaping the esthetics and values of Black design. Gilroy [16] refers to this as the “Black Atlantic,” a transnational space of cultural production that intersects African, American, and Caribbean influences. The work of individuals who identified as builders, architects, contractors, landscape architects, surveyors, carpenters, and others who shaped the built environment in a professional capacity that is, as a livelihood is included in the Black Architects Archive because it encompasses a wide range of built environment practitioners, regardless of whether they received compensation for their labor or received public recognition for their efforts. Segmenting building practices by separating mental and manual labor, giving mental labor a higher value, and then defining Black labor only through physical work were common strategies used to limit self-building and bar Black builders from profitable construction projects [36]. Moreover, this led to exclusion in the design field.

1.9. Reactions to Exclusion from Mainstream Modernism

The reaction to exclusion from mainstream modernism led to the creation of alternative networks and advocacy organizations. The founding of the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) in 1971 marked a significant moment in the fight for professional recognition and equity in design. NOMA continues to challenge dominant narratives in architecture, advocating for inclusive practices and increased representation [37]. These efforts underscore a broader paradigm shift in architectural practice from designing for elite clients to designing with and for communities. These efforts were not only about inclusion but about transforming the very criteria by which architecture and design are judged. The architectural profession still is tarnished by the underrepresentation of Black designers and architects. Despite making up 14% of the U.S. population today, Black people only make up less than 2% of the 116,000 or so licensed architects in the nation. The industry must address the need to create more egalitarian cities and spaces and include communities of color in these design processes, in addition to broadening diversity within the profession [37,38]. More than 600 structures in Washington, D.C. were built or designed by at least 100 Black architects, including well-known structures like Florida Avenue Baptist Church (Romulus Cornelius Archer Jr.), the residence of the Belgian ambassador (Julian Abele), and the Twelfth Street YMCA (William Sidney Pittman). However, a large portion of that history still is unknown and unrecorded, particularly in regard to lesser-known buildings [39]. To maintain a connection to the past, Black architectural modernity aimed to modernize vernacular methods and incorporate them into new applications. Frequently, they began as Black occupation or Black resistance tactics in white spaces, and subsequently, depending on the circumstances, they were codified as architectural techniques [7]. This pathway fostered community resilience and sustainability.

1.10. Building Community Resilience Through Design and Economic Development

Design has become a powerful tool for community resilience in Black communities, particularly in addressing socio-economic disparities and spatial injustice. Initiatives such as community land trusts, cooperative housing, and culturally responsive urban planning exemplify this shift. As Sutton and Kemp [40] argue, community-driven design fosters local economic development and empowerment. Projects led by Black architects often prioritize sustainability, heritage conservation, and economic equity. O’Hara [41] (p. 202) also argues that urban sustainability must be grounded in equity, stating that “resilience without justice will merely preserve the status quo of inequality.” For many years, Black architects in Washington, D.C., were limited to smaller projects, particularly homes, shops, churches, and schools in African American communities. The Walter E. Washington Convention Center in 1982, the Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center in 1986, and the Studio Theatre in 1987 are just a few examples of the large-scale civic and business commissions that practitioners like Paul Devrouax and Marshall Purnell were receiving by the 1980s. Today, many fans who attend games at Nationals Park, Figure 8, and Capital One Arena are unaware that they are taking in the creations of Black architects [39].

Figure 8.

National park in D.C. Photograph by Mitchell Layton/Getty Images.

Building community resilience correlates with the principles of Black Modernism, which emphasizes the intentional and culturally informed design of spaces that foster well-being, identity, and community cohesion [42]. Black Modernist architects have historically recognized that the built environment is not just functional, but deeply tied to psychological, emotional, and cultural experiences, especially in marginalized communities. For example, architects like J. Max Bond, Jr. and Paul R. Williams designed environments that considered not only esthetic form but also cultural resonance and emotional rejuvenation for their occupants, particularly African Americans navigating exclusionary urban landscapes. The insights from Maffei et al. [43] about workplace regeneration through elements like coherence, scope, and fascination are highly relevant to the goals of Black Modernism, which often incorporates symbolic, historical, and natural elements into design to elevate both the function and meaning of space. These environments are meant to do more than serve; they restore, empower, and affirm identity. In urban spaces shaped by systemic inequity, the movement reclaims design as a healing and productive force. Integrating historical architecture, culturally relevant materials, and sensory elements like light, texture, and color aligns with the Black Modernist vision of design as a transformative tool for social and psychological well-being.

1.11. Black Architects and Design-Driven Innovation

Black architects are increasingly at the forefront of design-driven innovation, integrating technology, community needs, and cultural narratives. Walter Hood, known for his landscape architecture, blends historical context with contemporary design to reimagine public spaces [20]. These innovations challenge traditional paradigms and introduce more inclusive frameworks for urban and architectural development. Stewardship and interpreting Black Modernism and the cultural significance of Black American architects are critical for preserving the physical aspect and historical relevance of Architecture to Verganti’s Design-Driven Innovation [44].

1.12. Black Architect’s New Vision for Promoting Quality of Life in D.C.—A Paradigm Shift (D.C. Paradigm Shift Driving Community Resilience)

In D.C., Black architects are leading a paradigm shift focused on enhancing the quality of life through community-driven design. This shift emphasizes inclusive placemaking, equitable access to resources, and participatory planning. The redevelopment of neighborhoods like D.C.’s Anacostia with the reflects this ethos, where design interventions align with cultural heritage and community resilience strategies [45]. Until we acknowledge the outstanding contributions of Black architects and designers, we will not have a clear grasp of modernism in the U.S. [46].

1.13. Black Architects as Developers—Intentional Design and Competitiveness: Implications for Architectural Design

The emergence of Black architects as developers signals a significant transformation in the profession. By engaging in both design and development, Black professionals assert greater control over the built environment and its socio-economic impacts. This dual role requires architectural design to adapt, integrating training in finance, entrepreneurship, and policy [47,48]. Melvin Mitchell, FAIA, is a pioneering Black architect and former professor at the University of the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C., best known for co-founding Bryant Mitchell Architects (formerly Bryant and Bryant Architects), the firm responsible for designing UDC’s Van Ness campus. As an early advocate for the concept of “Architects as Developers,” Mitchell emphasized the importance of intentional design as a tool for economic empowerment and community transformation. His work and scholarship have had a lasting impact on the profession, shaping conversations around Black architectural leadership, design competitiveness, and the integration of development practice within architectural education and equity-driven design.

Intentional design is not only a goal but a strategy for competitiveness and community uplift. At the same time that it was being used as a metaphor, “blight” evolved into a technical term for an urban state. This took place within the framework of two recently established professions: real estate development and urban planning. Every profession used the term “blight” to refer to one of the main issues that it could either address or profit from. Blight’s status as a mystery ailment and symbolic figure was both exchanged and changed; it evolved into an issue that called for the technical solutions of urban planning and created opportunities and problems for the development of real estate. The appearance, feel, and functionality of every room you enter after leaving your house are determined by commercial architecture and design, which is primarily created by white people. Equity in the built environment can be achieved through commercial architecture and design, but only if the individuals who develop those places are representative of the general community. Notwithstanding the structural challenges they encounter, Black-Owned Firms persist in making remarkable contributions to the built environment.

“Paul Gilroy talked about the Black Atlantic where we tend to reference intellectually the legacy from Western Europe to the US but we forget about the transatlantic slave trade in Africa and the trades that come that way so understanding the Black Atlantic understands a synthetic integration of West means and practices with the Black cultural needs and practices and spaces and so Black architectural modernism has to be that broader cultural project and so of course we use the same materials and we use the same drawing conventions and notations. But there is an embodied sense of place in a lot of Black modern architectural spaces that we have yet to write and it is the spatial embodiment that we miss in architecture, particularly in architectural schools and so it is really interesting to talk about architecture within the context of preservation because preservationists tend to understand this and foreground this idea of placemaking long histories of buildings, looking at the social setting themselves [44].”

2. Materials and Methods

A central theoretical framework guiding contemporary architectural practice in Washington, D.C. is the Value-Inclusive Design Model, which prioritizes human-centered, culturally responsive approaches to the built environment [11]. This model rejects purely esthetic or market-driven paradigms in favor of a value-driven methodology that integrates social equity, community needs, and cultural relevance into every stage of the design process [46]. In Washington, D.C., where urban development has often exacerbated racial and economic disparities, this model offers a corrective strategy.

Community design centers and grassroots organizations, such as the Urban Design Center of D.C., emphasize participatory processes in which residents are not only consulted but empowered as co-designers. As Bailey notes [49], involving communities in shaping their environment enhances both the social function and spatial relevance of architecture, particularly in historically marginalized neighborhoods. A foundational component of this model is community engagement, which repositions architecture as a dialogic rather than top-down discipline. This is especially critical in D.C., a city shaped by a complex interplay of federal authority, racial segregation, gentrification, and displacement. Architects who adopt a value-inclusive approach employ methods such as stakeholder workshops, public charrettes, and iterative feedback loops to ensure the resulting design reflects the lived experiences and aspirations of the community [50]. Projects like the redevelopment of Barry Farm illustrate how engagement-centered design can help preserve cultural identity while addressing infrastructural needs [51]. The model creates a number of ways for everyone to participate in an activity and feel included.

Intentional Design accounts for every situation while reconsidering and redesigning the existing physical environment to overcome its discriminatory aspects. For instance, analyzing the pipeline for Black women in architecture shows the conflation of race and gender leading to significant issues of representation in the profession. Only 1.9% of architecture degrees obtained by Black women were recognized as pre-professional or accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB). Furthermore, only 34% of all Black architecture students across all degree types and school types, including two-year colleges, are Black women, while making up nearly two-thirds (63%) of all Black students in higher education. According to these figures, Black women are tasked with forging their own path through the academy into the profession [52]. The VID model measures these disparities to combat systemic inequities and offers equitable solutions to advance the profession of Architecture for co-creation and co-design. Franz [3] contributes to the evolving understanding that architecture is not static, but can adapt, respond, and reframe meaning in ways that empower users and communities to see their surroundings, and themselves, differently.

Intersectionality, which seeks to understand how race, class, gender, and culture intersect to shape people’s experience of space, is another theoretical underpinning for our analysis. First introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw [53] in legal studies, intersectionality has been adapted by urban theorists and designers to acknowledge the layered inequalities embedded in the built environment. In Washington, D.C., where long-standing disparities along racial and socioeconomic lines persist, intersectional design frameworks demand an inclusive process that prioritizes those historically excluded from urban development narratives [11,54]. By addressing race, class, and culture, intersectional design challenges architects to go beyond surface-level diversity and engage deeply with systemic inequities. This involves acknowledging the legacy of redlining, urban renewal, and other policies that have disproportionately harmed Black and low-income communities. Scholars such as Sutton and Kemp [55] argue that design should be an instrument of restorative justice, distributing power and resources through equitable urban form. This approach is evident in projects like the 11th Street Bridge Park [56], where intentional design principles are being used to prevent displacement and ensure economic benefits are shared with long-term residents. Franz [57] argues that design has the capacity to “reinterpret traumatic sites and imbue them with new layers of meaning,” transforming spaces of loss into environments of reflection, education, and community healing, which build communities.

Finally, a collective case study approach is used to demonstrate how projects led by Black and minority architects [58,59,60,61] can provide a rich, contextualized understanding of how community capacity can be built through the design process. Here we define community capacity building as the creation of environments, systems, and practices that meet present community needs, such as housing, economic opportunity, and cultural expression, while strengthening the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This implies the responsible use of resources, inclusive planning, and long-term thinking that supports both ecological health and social equity. This collective intergenerational approach resonates with value-inclusive design principles that prioritize both immediate needs and long-term empowerment. As part of the data collection process, Borgers and Harmsen’s [58] measurement methods model emphasizes aligning data collection tools with the cognitive and emotional capacity of respondents, particularly in qualitative research involving marginalized groups. Their approach advocates for context-sensitive instruments to improve accuracy, reliability, and depth of insight in measuring perceptions, behaviors, and experiences. Similarly, Eisenhardt’s (1989) [59] measurement methods model emphasizes the use of a collective case study research for building theory, combining qualitative and quantitative data from multiple sources such as interviews, documents, and observations. Her approach focuses on triangulation, iterative data collection, and within-case and cross-case analysis to identify emerging patterns and construct robust, grounded theoretical insights.

Our collective case study of Black Modernism examines how architectural curricula integrate Black Modernism through three categories: (A) projects by Black and minority architects, (B) architectural firms owned by African Americans in the U.S., and (C) Value-Inclusive Design (VID) projects in Washington, D.C. These categories were analyzed for their contributions to history, theory, and preservation education, with a focus on sustainability and resilience as shown in Table A1 in Appendix A.1, both of which were strongly aligned with the principles of intentional design and value-inclusive design. The findings reveal recurring themes such as cultural preservation, spatial justice, and community empowerment. Projects in each category demonstrated ecological responsibility through material reuse, green infrastructure, and local sourcing, key aspects of sustainability. Resilience emerged through participatory design, cultural continuity, and economic inclusion. The collective case study shows that integrating Black Modernist projects and VID principles (Appendix B) into the architectural design not only fills historical gaps but also equips designers to address contemporary challenges in equitable, sustainable urban design. The collective case study approach also highlighted an emergent heutagogical model of architectural design where community members, particularly in historically Black neighborhoods, act as the teachers, not simply the subjects or observers, of design practice and historical preservation [13]. This shift from the community as learners to the community as co-teacher, along with the credentialed expert architect, values lived experience, cultural memory, and local expertise as central to understanding and sustaining architectural identity. Black architects, through their intentional and inclusive approaches, are at the forefront of this model, drawing design inspiration from grassroots knowledge and positioning their work within a larger continuum of cultural resilience and self-determination.

3. Results

3.1. Observations of the Collective Case Study

By asking where Black Modernism begins and how it fits within and beyond the broader American Modernist architectural movement, our research offers a collective case study to explore topics such as displacement, disinvestment, and cultural loss. These topics were prevalent, especially following the 1968 race riots in Washington, D.C., and linked Black Modernism to systemic issues of spatial injustice. Our inquiry into how the lived experiences of Black architects have informed their design strategies reveals a deep interconnection between biography, community, and form, anchoring architecture in lived realities. Moreover, the question of preservation highlights the urgency of protecting both tangible structures and the intangible narratives embedded within them. Central to the study is the proposition that the work of architects Marshall and Pichon initiates Black Modernism as a distinct architectural style, positioning it not only as a socio-political lens but also as a unique esthetic and theoretical framework within the broader architectural canon.

These research questions established the foundation for a collective case study, where 30 projects were selected and grouped into three categories to explore and evaluate patterns, differences, and themes across time and context. Category A examined seminal Black Modernism Projects by Black and minority architects, tracing historical legacies and form-driven expressions of identity and resistance. Category B focused on Architectural Firms Owned by African Americans in the U.S., assessing firm leadership, project typologies, and contributions to cultural and economic infrastructure. Category C centered on Value-Inclusive Projects in the Washington, D.C. area, specifically investigating how community-responsive, equity-driven projects exemplify contemporary applications of Black Modernist principles. Together, these categories allowed the study to compare historical foundations with present-day practices, drawing connections between theory, lived experience, and the built form. This collective case study not only provided evidence for a cohesive design methodology but also suggested that the work of architects like Marshall and Pichon may indeed define and advance Black Modernism as a recognizable architectural style.

Marshall’s work on the Howard Theatre restoration, Figure 9, is a prime example; the project not only revived a historic landmark but also served as a cultural and economic revitalization effort for the Shaw neighborhood, once known as “Black Broadway” [62]. These projects illustrate how community-driven design can preserve heritage while promoting local pride and engagement. Another powerful example of community-driven design is the 11th Street Bridge Park project, led by the nonprofit Building Bridges Across the River. Though not solely designed by Black architects, it was shaped through deep community collaboration and inclusive planning strategies that prioritized residents in Wards 7 and 8, areas often excluded from development processes. The team, including minority-owned architecture and planning firms, worked with residents to develop an equitable development plan focused on affordable housing, workforce training, and local business support [63]. This project exemplifies how the collective case study method can illuminate the importance of transparency, local agency, and economic empowerment in the design process. These community-led efforts also show the value of design as a tool for resilience and empowerment, rather than displacement.

Figure 9.

Howard Theatre, Washington D.C.; Image Credit: Shutterstock.

3.1.1. Examples of Successful Community-Driven Designs

Michael Marshall and Sean Pichon are two prominent Black architects based in Washington, D.C., whose architectural practices embody a refined expression of Black Modernism, an approach that merges Modernist principles with culturally grounded, community-driven design. From an architectural perspective, their “Black Modernism style” is marked by intentional form-making, clarity in materiality, and a deliberate focus on cultural narrative. Both architects draw upon African diasporic traditions and history, integrating symbolism, geometric patterns, and rhythms reminiscent of African design into the contemporary urban context. Their work also reflects a deep understanding of spatial justice, using architecture to affirm the presence and identity of Black communities within historically marginalized environments. Their projects are not only structurally sound and esthetically striking, but also socially resonant, reflecting a clear dialog between people, place, and memory.

A defining feature of Marshall and Pichon’s architectural vision is intentional openness, both physically and metaphorically. Their designs often incorporate large public-facing façades, transparent materials like glass, and broad entryways that welcome community interaction. For example, Michael Marshall’s design for the Chuck Brown Memorial Park and his work on the Franklin D. Reeves Center emphasize gathering, cultural storytelling, and civic pride, using open-air spaces and layered façades that invite public engagement while embedding African-inspired motifs and textures. Similarly, Sean Pichon’s design for Unity Health Care East and educational facilities in underserved areas often features courtyards, generous lobby spaces, and murals that convey heritage and openness. Both architects prioritize the inclusion of culturally relevant businesses, health services, and educational components within their structures, ensuring that architecture becomes not only a reflection of community identity but also a platform for economic development and social empowerment.

The redevelopment of the Franklin D. Reeves Center [64], Figure 10, at 14th and U Streets N.W. in Washington, D.C., represents a significant example of how intentional design can be aligned with community-driven urban revitalization. Originally built in the 1980s as a civic anchor in a historically Black neighborhood, the Reeves Center is now being reimagined as a mixed-use hub that includes affordable housing, commercial space, and the new national headquarters for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The project’s focus on maintaining cultural legacy while addressing modern economic and social needs reflects intentional design, design rooted in the values, goals, and lived experiences of the surrounding community. This project also embodies the core principles of VID by integrating identity, accessibility, empathy, placemaking, and transformation into both the planning and the projected outcomes [11].

Figure 10.

A rendering of the proposed redevelopment of the Franklin D. Reeves Center located at 14th and U Streets N.W.—A design collaboration between Michael Marshall and Sean Pichon. Image Credit: Michael Marshall Design/ Reeves CMC (2023).

By including a substantial portion of affordable units, providing opportunities for minority-owned businesses, and anchoring a culturally significant organization like the NAACP, the Reeves Center aligns with VID’s emphasis on designing for dignity, community health, and inclusive urban futures. Moreover, the project’s participatory planning process reflects empathy and transformation by inviting local voices into decision-making and ensuring that long-time residents are not displaced but empowered [65,66]. Together, intentional design and VID converge in this project to ensure that equity is not an afterthought but a driving force in shaping resilient and representative urban space.

The Reeves Center redevelopment project incorporates several sustainable features that contribute to recognitional equity, which refers to the acknowledgment and inclusion of historically marginalized groups in the design, planning, and development of the built environment. Recognitional equity focuses not just on outcomes, but on the respect, cultural visibility, and representation of communities often excluded from development processes. The inclusion of the NAACP’s national headquarters is a powerful symbol of cultural recognition and historical continuity. By placing a landmark civil rights organization at the heart of the redevelopment, the project affirms the Black community’s long-standing social and political presence in Washington, D.C., particularly in the historic U Street Corridor. With a commitment to provide at least 30% of the 322 residential units with affordable housing, the project ensures economic accessibility while resisting the displacement of long-time residents. This supports recognitional equity by affirming the right of lower-income residents, many of whom are Black or people of color, to remain in their historically rooted communities. The selection of a development team led by Black-owned firms, including Michael Marshall Design, signals an intentional shift in how power and visibility are distributed in major urban projects. This inclusion creates professional recognition for Black architects and developers, supporting equity in design leadership. The project was awarded through the Equity Request for Proposal (RFP) process, which mandated extensive community engagement [67]. Weekly meetings with stakeholders helped shape the design to reflect community values, ensuring that local voices were heard, seen, and respected, a critical pillar of recognitional equity. The design supports sustainable urban living by combining residential, commercial, and cultural spaces near public transit.

This ecological approach supports social sustainability and helps reinforce community cohesion while reducing environmental impact [68]. The proposed inclusion of public art and cultural spaces rooted in African American heritage reflects the design team’s commitment to preserving and honoring the legacy of “Black Broadway.” Such features create spaces of cultural affirmation and historical continuity, a core goal of recognitional equity. Despite their success, this collective case study also reveals significant challenges faced by minority architects and community-focused projects. Marshall, for example, has openly discussed the difficulty of securing large-scale commissions, like the Reeves Center, and the persistent undervaluing of Black-led design work in competitive public and private sectors [65]. Similarly, Pichon’s work on healthcare and education facilities across the D.C. area demonstrates that although community-focused projects are critical, they often encounter funding limitations, regulatory hurdles, and political obstacles that delay or restrict progress. These constraints limit not only the scale but also the sustainability of such efforts. Studying these challenges through this collective case study offers critical insights into the need for systemic changes in procurement policies, institutional biases, and access to capital for minority-led firms. By integrating affordable housing, culturally rooted institutions, minority-led design, and community-driven planning, the Reeves Center project creates sustainable infrastructure that honors and sustains the cultural identity of historically marginalized communities. This reflects the very essence of recognitional equity: being seen, valued, and represented in the fabric of the city. Building on this foundation, the work of architects Michael Marshall and Sean Pichon completes the study by exemplifying the continuity and advancement of Black Modernism in contemporary practice. Their projects reflect intentional design principles grounded in lived experience, cultural identity, and social equity, translating the historical legacies explored in the collective case study into tangible, community-responsive built environments. Through their innovative designs that integrate cultural storytelling, economic inclusion, and architectural openness, Marshall and Pichon demonstrate how Black Modernism is not only a historical phenomenon but a living, evolving architectural style.

The results of the collective case study, Table A2 in Appendix A.2, compared multiple projects to identify patterns or differences across different contexts by evaluating the content, learning objectives, and any Black Modernism projects highlighted in history and theory classes. These programs may have historic preservation classes where Black Modernism is addressed. These observations confirmed the equity and social impact of Black Modernism.

The work of Architects Marshall and Pichon is characterized by key elements of the architectural style of the movement, and their buildings, along with the histories they reveal, offer critical opportunities for preservation that honor cultural identity, community resilience, and inclusive design practices. Our collective case study was designed to compare Black Modernism projects across multiple historical and theoretical contexts. This chart evaluated content, learning objectives, and highlighted projects or architects that may be featured in architecture or historic preservation classes, helping identify recurring themes, gaps, and emerging patterns across institutions or course syllabi. As a result, projects designed by Black Architects Michael Marshall, FAIA, and Sean Pichon, AIA, definitely demonstrate value-inclusive design, which builds community capacity through intentional design practices for change-meaning. This includes preserving Black Modernism for a sustainable and resilient future.

The themes and patterns of the movement reveal a powerful narrative of cultural resilience, spatial justice, and community empowerment in the face of systemic exclusion. They highlight how Black architects and designers have historically used architecture not only as a form of creative expression but as a tool for reclaiming identity, preserving cultural memory, and resisting erasure from urban and academic landscapes. The movement also uncovers alternative design logics that prioritize lived experience, communal values, and social transformation over traditional Eurocentric esthetics. Ultimately, these themes challenge dominant narratives in architectural history and call for more inclusive, equitable frameworks that recognize the cultural depth and innovation inherent in Black spatial practices for change-meaning. Here are three key recommendations for studying Black Modernism within History, Theory, and Preservation Curricula:

- Integrate Black Modernist Figures and Case Studies into Core CourseworkEmbed the works of Black architects, designers, and community builders such as Paul R. Williams, J. Max Bond Jr., and Norma Merrick Sklarek into required architectural history and theory syllabi to ensure students engage critically with underrepresented contributions to modernism.

- Adopt Interdisciplinary and Inclusive Research MethodsEncourage the use of oral histories, ethnographies, and cultural criticism to explore Black Modernist legacies that may not be well-documented in traditional archives. This expands methodological approaches to preservation and allows for a fuller, more inclusive understanding of spatial heritage.

- Partner with Black Communities and Cultural Institutions for Preservation ProjectsCollaborate with local communities, HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), and cultural organizations to document, preserve, and interpret sites of Black Modernist significance. These partnerships reinforce community agency in preservation and create opportunities for experiential learning grounded in Value-Inclusive Design.

3.1.2. Lessons Learned from Challenges Faced

One key lesson learned from these projects is the importance of intentional and sustained community engagement. In both Marshall’s and Pichon’s practices, community outreach is not a one-time consultation but an ongoing dialog that informs every stage of the design process. This includes neighborhood listening sessions, participatory design charrettes, and follow-up evaluation methods that help foster trust and build design literacy among residents [66]. Through this collective case study, we also learn that culturally competent design is not merely esthetic; it involves the inclusion of social memory, local needs, and community aspirations into architectural form. These insights underscore the need to train future architects not only in design skills but also in communication, cultural empathy, and community-building strategies. This visual language and esthetic translate into Black Modernist style.

Ultimately, the use of a collective case study as a methodology for examining Black Modernism and community capacity building provides a powerful lens to understand the intersection of design, justice, and empowerment. These real-life examples demonstrate that when Black and minority architects lead projects with community values at the core, the outcomes extend beyond buildings; they help rebuild community identity, promote equity, and stimulate local economies [68]. More importantly, they offer a roadmap for replicating these successes in other urban areas. As design education and practice continue to evolve, case studies from Washington, D.C. and beyond can serve as foundational learning tools for promoting more inclusive and impactful architectural practices and Design-Driven Innovation. This includes recognizing Black Modernism as a form and style for design.

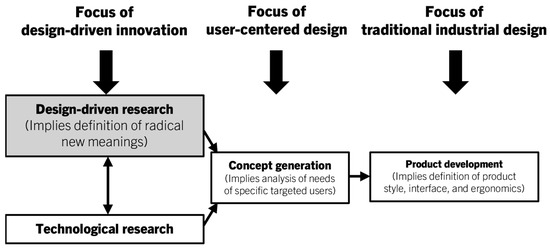

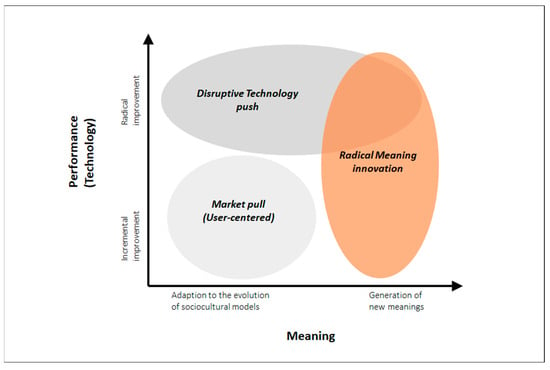

3.2. Design-Driven Innovation: Role of Community in the Design Process

3.2.1. Empowering Local Voices

Roberto Verganti’s concept of Design-Driven Innovation, as depicted in Figure 11, emphasizes the creation of new meanings through design, not just new functionalities or improvements. Within this framework, the role of the community becomes essential in redefining how products, services, or environments are understood and experienced. While Verganti originally focused on product design, the principles extend naturally to architecture and urban planning when local communities are positioned as co-creators of meaning. Empowering local voices in the design process ensures that innovations are not only technically sound but also culturally resonant and socially impactful. As Verganti [69] notes, “radical innovation in meaning is not discovered through traditional market research, but through deep interaction with interpreters who are able to propose new visions.” In urban design, these interpreters can and should be community members themselves, especially in historically marginalized neighborhoods where existing spatial meanings are often products of exclusion or displacement. This approach is particularly relevant in architecture and urban design, where the reinterpretation of space can lead to shifts in social behavior, cultural identity, and economic activity. For example, in community-based design, changing the meaning of a public space from a zone of neglect to a site of cultural pride and collective memory exemplifies design-driven innovation in action.

Figure 11.

The strategy of Design-Driven Innovation as a radical change of design (Verganti 2009; HBR Press) [69].

Thus, by focusing on meaning-making, Verganti’s framework empowers designers to act as cultural agents, driving deep transformation through intentional, visionary practices. Since building occupant behavior impacts a building’s sustainability, it was discovered that sustainable building construction alone could not solve the issue of architecture’s negative environmental impact. Therefore, the psychological elements that are crucial to sustainable behavior, such as green mindfulness, tend to be reinforced when sustainable design fails to encourage sustainable behavior [70]. Design-Driven Innovation emphasizes the creation of new meanings rather than merely improving functionality, and within this framework, the role of community becomes central to shaping design outcomes that are culturally relevant, emotionally resonant, and socially transformative. By actively involving communities as co-creators rather than passive recipients, this approach enables designers to uncover deep insights about local values, histories, and aspirations that can inform innovative spatial solutions. Community participation enhances design authenticity and ensures that spaces reflect the lived experiences of those who use them, which is especially vital in projects addressing marginalized populations. As Verganti asserts, innovation in meaning emerges not through traditional market analysis but through interpretive engagement, making the community not only a stakeholder but a source of visionary input [69]. Through this process, Design-Driven Innovation becomes a powerful tool for achieving equity and sustainability in the built environment.

3.2.2. Collaborative Design Approaches

Building on this, collaborative design approaches rooted in community partnerships align closely with Verganti’s call for innovation through meaning-making. Participatory processes such as design charrettes, storytelling workshops, and co-design sessions invite residents to articulate their needs, values, and aspirations. This collaboration enriches the design process by embedding multiple layers of local context, from cultural identity to socio-economic challenges. When architects and designers actively engage with communities, they help translate these lived experiences into spatial and structural elements that reflect shared meaning. As Manzini and Rizzo [71] argue, “collaborative design is not only about solving problems but about constructing a shared vision of the future.” This approach to innovation is especially transformative in urban environments where equitable development and cultural preservation are key. By applying Verganti’s theory, Appendix C, through inclusive practices, designers can help communities reimagine their spaces in ways that are both meaningful and forward-looking through ideal implementation.

3.3. Ideal Prototype: Applications of Value-Inclusive Design

3.3.1. Practical Implementation in Urban Planning

The ideal prototype of value-inclusive design emphasizes the integration of community values, social equity, and cultural identity into the fabric of urban planning. This model goes beyond esthetics or functionality; it redefines design as a democratic, collaborative process. In practical terms, this means embedding participatory planning processes into every stage of development, from visioning to execution. Urban planners and architects who adopt this approach work closely with residents to co-create environments that reflect local values and respond to pressing social needs. As Sanoff [50] explains, “participatory design is most successful when it aligns design intent with community aspirations.” In cities like Washington, D.C., where rapid redevelopment threatens to erase historically Black neighborhoods, value-inclusive design offers a counter-model that centers resident voices and promotes long-term resilience. As a result, this will boost local economies and promote sustainability. Practical implementation in urban planning involves translating policy goals and community needs into tangible, spatial solutions through zoning, infrastructure, and land-use decisions. When guided by inclusive frameworks, it enables equitable development by prioritizing affordable housing, accessible transportation, and culturally relevant public spaces.

3.3.2. Impact on Local Economies and Sustainability

In terms of economic and environmental outcomes, value-inclusive design contributes significantly to local sustainability. By focusing on community-driven priorities such as affordable housing, access to green space, and localized job creation, this model supports the development of inclusive economies. For example, community land trusts and co-designed commercial corridors not only stabilize housing costs but also foster entrepreneurship among historically excluded groups. According to Sutton and Kemp [55], “urban design that builds social infrastructure alongside physical infrastructure promotes more equitable and sustainable urban growth.” Furthermore, by encouraging locally sourced materials and energy-efficient building strategies, value-inclusive design aligns with environmental sustainability goals, creating neighborhoods that are both livable and future-oriented.

3.3.3. Promoting Cultural Heritage Through Intentional Design

Another key application of value-inclusive design is its ability to preserve and promote cultural heritage through architecture and placemaking. This is especially important in communities facing gentrification or cultural erasure. Projects that incorporate public art, historic references, and vernacular design elements help reinforce collective memory and cultural identity. Architects like Michael Marshall have championed this approach through projects such as the restoration of D.C.’s Howard Theatre, where historic preservation and community storytelling were central to the design process [62]. These interventions not only beautify public space but also reaffirm a community’s right to visibility and belonging. As Costanza-Chock [56] notes, “design justice demands that the voices of the most marginalized be not just heard but be primary in shaping our built environment.” Value-inclusive design, therefore, acts as both a practical and symbolic tool for justice, equity, and empowerment. Yet, there are still barriers and adversities to overcome. The study of Black Modernism highlights the need for urban planning policies that prioritize cultural preservation, community ownership, and inclusive design practices, particularly in historically marginalized neighborhoods. For education and professional practice, this necessitates curriculum reform and cross-sector collaboration with diverse stakeholders, including residents, policymakers, and developers, to ensure equitable development reflects the social and cultural fabric of the communities it serves.

4. Discussion

Challenges and Opportunities

The evolution of Black Modernism, intentional design, and design-driven innovation has been groundbreaking, yet it continues to face systemic challenges. A primary barrier is institutional resistance; many academic and professional architecture spaces still operate within Eurocentric models that fail to acknowledge the contributions and intellectual frameworks of Black architects. As Drecksel and Dunham [72] point out, such resistance can result in discriminatory hiring, exclusion from key commissions, and a general undervaluing of culturally grounded design approaches. Equally troubling is the lack of financial support for community-driven projects led by Black professionals. These initiatives often are excluded from traditional funding streams and operate without the resources required for meaningful implementation. Sutton and Kemp [55] emphasize that equity-driven innovation demands long-term investment, not one-time grants, yet funding often comes with conditions that prioritize institutional interests over community needs.