Abstract

This study explores how architectural atmosphere can foster mindfulness constructs in response to the growing mental health crisis. Mindfulness, known for improving mental health, reducing stress, and enhancing overall well-being, is increasingly recognized as a potential solution to mental health challenges. However, research on how architectural atmosphere supports mindfulness is limited. This study systematically reviews architectural atmosphere features that promote mindfulness constructs, which includes awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness. A literature review was conducted using the Scopus database, following PRISMA guidelines for transparency. Fifty-three articles were selected, focusing on mindfulness features in architectural atmosphere: awareness (4), openness (1), attention (28), focus (5), and connection (15). No studies were found on architectural atmosphere fostering calmness. The findings suggest that architectural atmosphere plays a significant role in supporting mindfulness, but further empirical studies are needed to validate these results in real-world contexts.

1. Introduction

In recent years, mental health and well-being have become prominent discussion topics in architectural design. Architecture significantly impacts the psychological well-being of individuals []. Prior research indicates visible architectural components, such as shape, form, proportion, color, and materials, and invisible sensory factors, such as sound and scent, can profoundly affect human well-being [,]. Even though most architecture is intentionally designed by architects to positively impact building occupants [], specific architectural design characteristics may adversely affect the well-being of building users [,] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The dual impact of architectural design on occupant well-being.

These are examples of negative impacts on mental health that arise from architectural characteristics. Previous research has indicated that symmetrical form can decrease an individual’s sense of satisfaction [,]. Objects with sharp angles tend to elicit stronger feelings of fear than those with curved forms [,,]. Environmental noise has been shown to elevate human stress levels [,]. The absence of vegetation in built environments has been linked to increased stress, a sense of oppression, and elevated user arousal [,]. While buildings may adversely affect human mental health, individuals spend more than 90% of their time indoors [,].

Furthermore, modern ways of living and current social, economic, and technological conditions increasingly challenge individuals’ ability to sustain mental health and overall well-being []. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized the urgent need to address mental health care for populations [,]. The United Nations incorporated the promotion of well-being into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), identifying it as a key objective to be achieved by 2030 [,]. Given these challenges, this study seeks to determine how architectural design can mitigate mental health issues, given its ability to be intentionally shaped.

Amid growing efforts to address mental health issues, mindfulness has been receiving increasing attention []. It is being used by individuals and large organizations, and even incorporated into public policies in some countries [,,,]. Building upon this growing interest, an expanding body of research has highlighted the positive impact of mindfulness on mental health and overall well-being, including its association with better sleep quality and enhanced life satisfaction [,,,,]. Empirical studies further demonstrate that mindfulness practices can effectively alleviate a wide range of psychological challenges, such as stress, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, rumination, burnout, and symptoms of depression [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. In parallel, emerging evidence points to the potential of architectural environments to facilitate mindfulness, thereby offering additional pathways to support mental health and psychological resilience [] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A conceptual model of mindful architecture and its mental health benefits.

The findings underscore the potential of architectural design to enhance mental well-being by mitigating the negative impacts that may arise from the built environment itself and by supporting psychological recovery from the stresses of everyday life. Thus, the following section reviews the state of existing studies on architecture that fosters mindfulness. This review also identifies a critical gap in the current body of knowledge, pointing to the need for further research.

1.1. Existing Research and Gaps

A publication from 2017 indicated a notable lack of knowledge regarding architectural design that supports mindfulness []. The study focuses on exploring design approaches for environments that promote mindfulness, specifically in the context of healthcare architecture and biophilic design. Due to the study’s relatively specific research objectives, gaps in other related areas remain and can be further explored by future research. Subsequently, a 2018 study emphasized the urgent need to explore architectural design approaches that foster mindfulness, particularly to promote sustainability []. This study considers mindfulness as a mechanism to effectively foster sustainable behaviors within the built environment. Moreover, it acknowledges that architecture can significantly influence its occupants. Therefore, promoting mindfulness through architectural design for the benefit of its users is a promising direction for further research. These two studies clearly highlighted the lack of knowledge about architecture supporting mindfulness. Based on a systematic literature review covering the period from 2013 to 2022, it was found that there were no studies specifically addressing architecture that promotes mindfulness during this time, until the emergence of more recent research.

A systematic literature review published in 2023 on architecture that supports mindfulness revealed several vital insights []. The publications reviewed in this study were sourced from three major databases: Scopus, Google Scholar, and Thai Journals Online, encompassing publications from 2013 to 2022. It was found that the architectural atmosphere is crucial in fostering mindfulness []. In particular, elements drawn from Buddhist contemplative spaces [,,], characteristics of traditional Japanese architecture [], and components of biophilic design have been recognized for their potential to promote various states of mindfulness [,,]. Buddhist architecture and biophilic design were mentioned in three studies, whereas Japanese architecture was only referenced in one. Due to the limited number of studies on mindfulness-supportive architecture, these conclusions are drawn from a limited body of literature comprising only eight publications. Thus, although this review has identified key components and design approaches that may foster mindfulness through architecture, the small number of relevant publications retrieved through the systematic literature review highlights the fact that a substantial research gap still exists.

A 2023 study decoded architectural characteristics in images tagged with #Mindfulness on Instagram, predicting that these places contribute to individuals’ ability to access states of mindfulness []. The results revealed that the architectural characteristics in the images predominantly align with traditional Japanese architecture, followed by biophilic design, with Buddhist contemplative spaces being the least represented. Based on these findings, conventional Japanese architecture seems most strongly associated with individuals’ sense of mindfulness. This finding differs from the results of the systematic literature review, where traditional Japanese architecture was mentioned only once. Therefore, it is not yet possible to conclude which approach will most likely stimulate mindfulness.

In 2025, a study analyzed images of mindful architecture generated by DALL·E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, assuming these AI outputs reflect large-scale perceptions []. The results revealed consistent features: structured lines with sharp edges, open indoor–outdoor connections, vertical and horizontal movement, natural lighting, earth-tone colors, use of wood, stone, and glass, and views of greenery creating calm, atmospheric environments with gentle natural sounds. The findings of this study provide insights into architectural features that are likely to support mindfulness.

As the reviewed literature suggests, scholarly investigations into how architectural design can support or cultivate mindfulness remain relatively scarce. Moreover, the architectural concepts and specific design features that may stimulate mindfulness remain underexplored. Furthermore, existing research indicates that mindfulness is a complex psychological construct, closely associated with various interrelated mental states. It is conceptualized through six interlinked dimensions: awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness [,,,,,,,,,,]. This finding leads to the formulation of this study’s research objective and question, which are outlined in the following section (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The conceptual framework of this study.

1.2. Research Objective and Question

This study aims to explore architectural design approaches that positively impact mental health, in response to the worsening mental well-being crisis. While mindfulness is increasingly recognized as a potential solution to well-being challenges, and architecture has the capacity to support mindfulness, research in this area remains limited. Based on the literature review, architectural atmosphere has been identified as the most influential architectural element in fostering mindfulness. Previous studies have shown that mindfulness encompasses several interrelated constructs: awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness. Accordingly, this study aims to explore the architectural atmosphere features that foster mindfulness constructs. This research seeks to answer the question: which architectural atmosphere characteristics contribute to fostering mindfulness constructs?

To enhance clarity and facilitate effective communication with readers, definitions of key research terminology are presented in the following section.

1.3. Definition of Research Terminology

Architectural atmosphere refers to the architectural elements that play a crucial role in fostering mindfulness. These elements include form, space, movement, light, color, material, object, view, sound, and weather [,,,,,].

Mindfulness constructs refer to the psychological states or emotional qualities that constitute the broader experience of mindfulness. These include awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness [,,,,,,,,,,].

2. Methodology

This study’s methodology was designed to address the academic gap between architecture and mindfulness by exploring the concept of architectural atmosphere that fosters mindfulness constructs, an area that remains relatively underexplored in the existing body of literature [,,]. To explore architectural design approaches and gather insights from diverse disciplines beyond the conventional boundaries of architecture [,,], this study adopts a systematic literature review methodology [,,].

This systematic literature review was conducted using the Scopus database, which is recognized as the largest academic database available [,]. All search procedures were undertaken and completed by the end of February 2024.

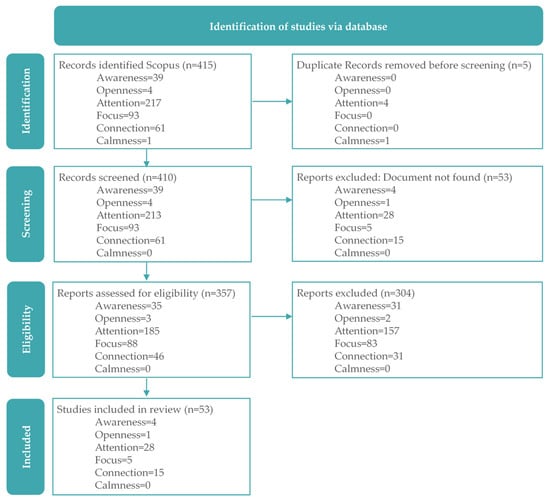

The systematic literature review conducted in this study follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, as this approach ensures transparency, reliability, and replicability of results, while minimizing bias [,]. The following section will describe the four phases of the PRISMA process as applied in this study.

2.1. Identification Phase

To explore studies concerning architectural atmosphere, the term architecture was selected to expand the search scope and avoid the limitations of overly specific terminology. In order to locate articles that support the mindfulness construct, we employed terms that convey the relevant experiential qualities, including awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness. These terms will be queried in the titles, abstracts, and keywords, as these sections represent critical elements of the article [].

To enhance the credibility of the sources, the search was limited to publications classified as articles, reviews, conference papers, and conference reviews []. Furthermore, to ensure relevance to architecture or the built environment, the search was restricted to documents categorized under the engineering field and containing content related to architecture []. To ensure that the selected publications were accessible for content analysis, only English-language publications were included.

Finally, the search strings used to identify publications related to architecture that fosters mindfulness constructs can be summarized according to each sensory-related component, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strings for Scopus Database.

During the Identification phase, a triangulation method involving multiple researchers was employed, to ensure the objectivity and accuracy of the data []. Three undergraduate research assistants from the field of architecture conducted the search and cross-check processes. These individuals were selected based on their familiarity with architectural academic discourse and their proficiency in English. To ensure accuracy, a graduate student in architecture reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles. Their names are acknowledged in the Acknowledgements section.

This process led to the identification of a total of 415 documents published between 1984 and 2024. The documents were compiled into Google Sheets and organized based on search terms and year of publication. Five articles were excluded, due to duplication across databases.

2.2. Screening Phase

All 410 publications were considered in the screening phase. After excluding the duplicates, a quick scan was conducted to ensure that the documents were available for access. A graduate student in architecture, mentioned above, also carried out this step.

After screening, 53 articles were removed because the documents were not found or were inaccessible.

2.3. Eligibility Phase

In the eligibility phase, the remaining 357 documents were screened by the graduate student. To confirm the accuracy and objectivity of this review, three authors, one architectural researcher and two architects, independently reviewed the full-length articles to confirm their suitability for this systematic literature review.

A total of 304 articles unrelated to architectural atmosphere and mindfulness constructs were excluded, as they were outside the scope of the research.

2.4. Inclusion Phase

After careful consideration and discussion by the authors, the number of publications included in this review came to fifty-three.

The reviewed articles explore architectural atmospheres that support different facets of mindfulness, including awareness (4 articles), openness (1 article), attention (28 articles), focus (5 articles), and connection (15 articles). Notably, no articles were identified that explicitly address architectural environments fostering calmness. The systematic literature review process conducted following PRISMA guidelines is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic literature review.

The following section provides an overview of the 53 selected articles, offering detailed descriptions to help readers understand their characteristics. These articles will be used to analyze and address the research questions in this study.

3. Selected Articles

The selected articles from the previous stage include details such as year of publication, publication source, country of publication, first author’s affiliation country, and number of citations, as outlined in the following section.

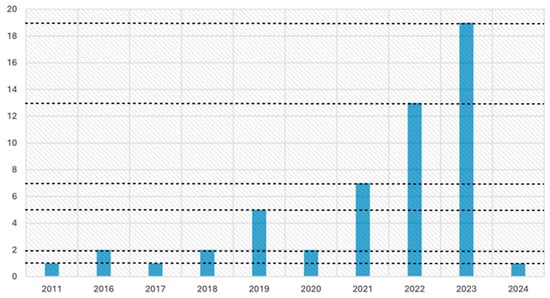

3.1. Year of Publication

Between 2011 and 2017, research on how architecture relates to mindfulness was still developing, averaging only one to two publications annually. Momentum began to build in 2018 and 2019, when output rose to roughly two and five papers. Although the COVID-19 pandemic caused a slight dip in 2020, the numbers bounced back quickly: the number of studies doubled in 2021 and reached its highest level in 2022–2023, with approximately 15–20 papers published annually. The 2024 tally is presently low, because the year’s publication cycle is not yet complete. These data show that the topic has quickly moved from a small, experimental area of study to one that many researchers now focus on (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Publication year of selected articles.

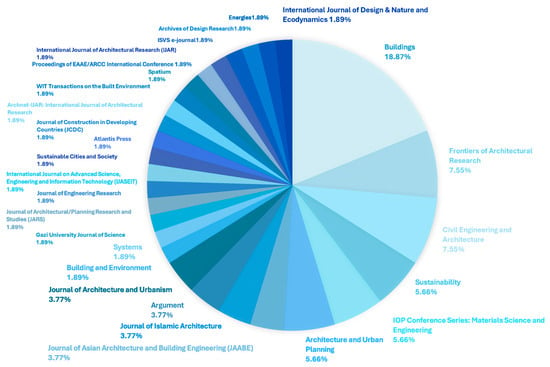

3.2. Publication Source

The publications published in Buildings accounted for nearly one-fifth of the papers, underscoring its role as the leading journal for research on architecture and mindfulness. Two additional journals, Frontiers of Architectural Research and Civil Engineering and Architecture, contribute about 8%. Sustainability, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, and Architecture and Urban Planning add roughly 6% apiece. The remaining half of the publications are spread across over twenty other journals and conference proceedings (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Publication source of selected articles.

3.3. Country of Publication

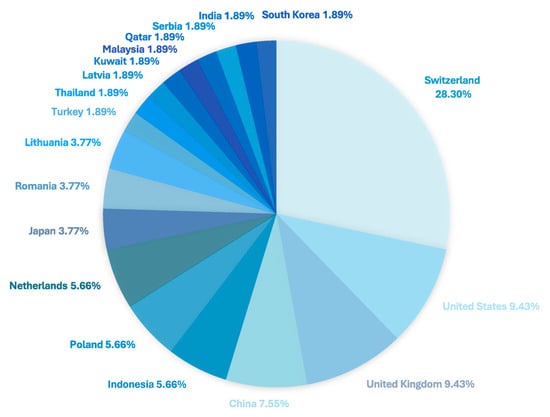

Switzerland dominates the dataset, contributing roughly one-third of all publications. Immediately following in productivity are the United States, the United Kingdom, and the People’s Republic of China, each responsible for approximately one-tenth of the total output (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Publication country of selected articles.

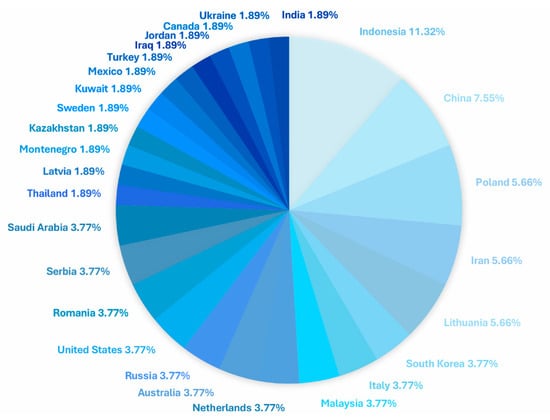

3.4. First-Author-Affiliation Country

Indonesia provides the largest share of first authors, about 15%, with China close behind, at roughly 10%. Poland, Iran, and Lithuania each contribute 6–8%, while South Korea, the United States, Australia, the Netherlands, Italy, and Russia fall in the mid-single digits. All other countries, more than twenty, each supply less than 3% (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

First-author-affiliation country of selected articles.

3.5. Number of Citations

Approximately 80 percent of the articles record fewer than 20 citations; the most cited publication is the work of Weijie Zhong, which has 394 citations, followed by the research of Asaad Almssad, Yao Chen, and Luis Alfonso de la Fuente Sua’rez in the 60–66 range, followed by the study by Keunhye Lee and the Mohamed S. Abdelaal datasets, which have a peak of 35 and 49 citations.

However, the articles’ titles, authors’ names, and other related information for the selected articles discussed in this section are included in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D and Appendix E.

4. Results

Upon analyzing the content of the 53 selected articles, the attributes of architectural atmospheres that promote the mindfulness construct can be delineated, based on the following components:

4.1. Awareness-Influencing Architecture Elements

- Space

The proximity distance of mosques and tombs influences awareness and a reminding of death []. Openness and tactile spaces in architecture further shape how individuals experience their surroundings, guiding their awareness of space and interaction [].

- 2.

- Light

Light change and illumination play a crucial role in shaping awareness by altering the perception of space and influencing emotional response through dynamic lighting effects [].

- 3.

- Color

The colorful beauty of natural landscapes [] enhances natural-landscape awareness, while spiritual needs increase. Black charred surfaces with other elements are claimed to influence emotions and awareness [].

- 4.

- Material

Material condition changes during a building’s lifetime influence empathetic awareness of the current ecological crisis []. Concrete and cement play a significant role in shaping people’s emotions, along with other elements [].

- 5.

- Object

Mosques, tombs, and mihrabs influence awareness through their cultural and religious significance []. Natural landscape resources enhance people’s awareness of the environmental crisis []. Chapels captivate emotions and awareness, when designed with some significant elements [].

- 6.

- View

Mental maps and symbolic interaction guide awareness about death []. Sky view, land view, water view, and life view promote awareness and encourage engagement with nature []. Openings to sky views enhance awareness [].

- 7.

- Sound

Mystical silence and responsive silence significantly influence auditory awareness, along with other elements [].

- 8.

- Weather

Weather impacts human emotions and awareness; instances from this study can be observed from Peter Zumthor’s famous Bruder Klaus Field Chapel and his other works [].

These results are based on four studies that explore how architecture can promote various forms of awareness, including heritage conservation, climate change, sustainable practices, and clarity of purpose.

4.2. Openness-Influencing Architecture Elements

- Form

Flat, same-height floors promote equality, eliminating spatial hierarchies to respect all guests equally [].

- 2.

- Space

Open spaces without walls enhance visual connection and openness [].

- 3.

- Material

Movable wooden walls, like Gebyok, reflect openness, allowing adaptable spaces for homeowners [].

This study discusses the use of open-plan architectural features to convey the homeowner’s sense of openness.

4.3. Attention-Influencing Architecture Elements

- Form

Unique forms of different architectural styles [] and specific design elements such as roofs, curves [], compositions [,,], and dominant geometric forms like spheres or high-rise structures [] naturally guide the eye and create attention, as do, similarly, features such as symmetrical shapes, structural hierarchies [], and the expression of architectural forms []. At the same time, geometrical characteristics [,], including patterns, and recognizable forms [] can anchor attention emotionally and cognitively.

- 2.

- Space

Elements such as open spaces [], natural exposure, and green areas [,,,] help offer relief and connection to nature, and promote attention. Spatial features like axis spaces and corridors direct attention within the built environment []. Meanwhile, spatial organization, whether through compressed layouts [], public spaces [], or a learning environment [], structures how individuals navigate and engage with their surroundings. These spatial qualities ultimately enhance attention [].

- 3.

- Movement

Design elements such as main pathways [], horizontal flows, entrances, and axis endpoints [] naturally guide visual and physical navigation through space. Features like wave-like forms [] and sequences of open and closed areas [] stimulate curiosity and maintain engagement as people move, influencing attention.

- 4.

- Lighting

Elements like high-contrast and warm white scenarios [], silhouettes [], and natural daylight [,] guide attention, in the same way as luminosity [], light reflection [,], and dynamic lighting []. In general, lighting in designs affects attention [].

- 5.

- Color

Elements like greenery [], bright colors [], and color differences [] create focal points that naturally draw attention. Colors that create patterns and combinations establish visual flow, attracting people’s vision []. Additionally, the interplay of color and contrast can also impact attention [,,].

- 6.

- Material

Architectural material selection guides attention: for instance, natural patterns and green walls [], patterned brick [], nature-derived materials [], tactile surfaces and stone []. Together, these material applications were claimed to sharpen perception and direct people’s attention.

- 7.

- Object

Architectural objects such as sphinxes, mosques, and iconic buildings [,,,] capture attention through their symbolic presence. Large buildings [] anchor attention via scale, while geometric forms and structures [,] also guide emotion. Natural elements, greenery, water, and landscapes [,,,,,] consistently draw one’s attention, with biophilic cues. Artworks and illusions [,] sustain engagement, and external elements, such as windows, doors, and facades [,,,], shape how attention is distributed.

- 8.

- View

Architectural elements like green views, indoor vegetation, and landscape features [,,] consistently capture attention through biophilic appeal. Visual tasks, memory, and resolution [,,] benefit from features that sharpen perception and enhance emotion. Similarly, relative viewing angles and visual lines [,] guide attention across spaces. Design contrasts and spatial variations [,] influence what stands out within architecture. Lastly, reflective surfaces and vantage points revealing hidden areas [,] shape how visual attention shifts throughout a space.

- 9.

- Sound

Research indicates that acoustic environments serve as pivotal elements in guiding auditory attention within architecture [].

The studies referenced in this section are primarily concerned with generating interest in religious buildings and creating visual engagement. In addition, some studies explore the use of architecture to facilitate attention restoration.

4.4. Focus-Influencing Architecture Elements

- 1.

- Form

The shape of space is an architectural element that can be calmly focused on in a specific environment []. Biomorphic forms allow users of the built environment to feel connected to nature and enhance their focus [].

- 2.

- Space

Design-studio environments have been indicated to cause more focused attention among students [].

- 3.

- Light

The light of the Moon influences focus by providing illumination that shapes spatial perception [].

- 4.

- Material

Microalgae facades enhance more focus on environmental sustainability when studied in students who conducted tasks in their environment, compared to students in a controlled environment [].

- 5.

- Object

Façades of famous historic buildings were calmly focused on by many tourists every year, through their architectural significance [].

- 6.

- View

Illuminated architecture involves people focusing on building []. Visually and perceptually, pleasing natural patterns enhance concentration and focus [].

- 7.

- Sound

A quiet, contemplative silence emerges when one calmly focuses on architecture [].

The topic of architecture that promotes focus is often associated with educational and religious buildings.

4.5. Connection-Influencing Architecture Elements

- 1.

- Form

Environment-driven design [,]. Open roofs link spaces to sky and surroundings [], while strict lines, biomorphic shapes, and spatial hierarchies [] guide interaction. Proportions, compressed spaces, and modular forms [,] enhance experience. Form and volume, entrance geometry [], and spatial arrangement with human scale [] further contribute to architectural connection.

- 2.

- Space

Narrow connective spaces, plazas, and courtyards link areas and enhance engagement [,]. Features like inner gardens and rooftop terraces add intrigue and mystery [], while spacious and confined spaces affect mood []. Opportunities for movement and spatial continuity strengthen cohesion [], and entrances and transitions support connection []. Lastly, cozy, transitional spaces like those in churches create a sense of something greater [].

- 3.

- Movement

Rooftop paths, public routes, and visual axes offer panoramic engagement []. Paths over water, air movement, and stargazing experiences foster co-creation with nature []. Interaction between occupants and surroundings deepens spatial awareness [], while bodily interaction and adaptation shape experience []. Passages, entrances, and doorways guide connection and control movement [].

- 4.

- Light

Facades with solar penetration and light refraction balance shade and transparency []. The interplay of light and shadow, shifting sunlight, and diffused light creates a visual connection []. Full windows and natural light promote positive emotions [], while contrasts of light and darkness enhance connection, as seen in Zumthor’s Thermal Vals [].

- 5.

- Color

Local limestone and rammed earth blend with natural surroundings []. Visual and functional links are established through color compositions [], while roofing colors evoke traditional wooden architecture [].

- 6.

- Material

Visual and functional ties emerge through material choices [], with timber cladding, aging wood, local materials, and planted surfaces enhancing context []. Materials influence psychological responses [], while tactile engagement with stone, wood, water, and mist deepens bodily connection []. Exposed stone and wooden structures evoke comfort and familiarity.

- 7.

- Object

Elements like fountains, ponds, wood facades, and planted columns enhance sensory and spatial interaction []. Furniture selection shapes mood and emotional response []. Entrances guide spatial transitions and engagement []. Modernist buildings promote stronger connections between interior spaces and the surrounding environment [].

- 8.

- View

Arranging volumes and walls to blend with the landscape strengthens spatial integration []. Views to pine groves, open vistas, cloud movement, and birds, enhance natural engagement []. Windows shape perception and foster community connection [], while systems like Chidori offer layered views and distance-balanced exterior links. Visual depth, angles, and inside–outside connections further enrich spatial experience [].

- 9.

- Sound

Natural sounds: wind through plants, water babbling, rustling curtains, and nature heard through open windows, enhance spatial connection and engagement []. Flowing water in Thermal Vals deepens sensory immersion and generates connection []. Acoustic qualities contribute to how spaces are perceived and recognized, shaping memorable architectural experiences [].

- 10.

- Weather

Microclimates like shaded courtyards and thermal walls help manage desert heat []. Humidity and thermal conditions in mountain and coastal areas shape comfort strategies and spatial experience []. These elements promote connection.

Architecture that promotes connection differs notably from other themes, as most studies tend to interpret connection as linking architectural elements, rather than fostering interpersonal or emotional connectedness.

4.6. Calmness-Influencing Architecture Elements

This systematic literature review did not identify any studies that explicitly explored how architectural design may contribute to the cultivation of calmness.

5. Discussion

To address the following question, which architectural atmosphere characteristics contribute to fostering mindfulness constructs? this systematic review highlights the critical elements that foster mindfulness constructs: awareness, openness, attention, focus, connection, and calmness. The review was conducted using the Scopus database, one of the largest academic databases, and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparency and reliability. This resulted in 53 articles being selected for final inclusion. These articles explored various aspects of mindfulness in architecture: awareness (4), openness (1), attention (28), focus (5), and connection (15), with no studies found on architecture fostering calmness. However, the results are derived solely from the search conducted based on the specific criteria outlined in Section 2.1. Therefore, future research employing different keywords, search parameters, or academic databases, may yield different outcomes, including the possibility of not identifying any studies related to architecture that promotes calmness.

The selected articles were published most frequently in 2023, followed by 2022 and 2021, respectively. The journal Buildings, based in Switzerland, published the highest number of selected articles. The majority of lead researchers are from Indonesia, followed by those from China and Poland. By a significant margin, the most frequently cited article is Biophilic Design in Architecture and Its Contributions to Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability, which is referenced far more often than any other source. When considered alongside the literature reviewed in Section 1.1, which identifies biophilic design as a key architectural approach for promoting mindfulness [,], this finding further reinforces the significance of biophilic design in mindful architecture. Additional research also highlights architectural features that foster mindfulness in ways that align closely with biophilic design principles []. These insights suggest that biophilic design plays a critical role in shaping architectural environments that support mindfulness and mindful constructs. This may be attributed to the human inclination toward nature, commonly called biophilia [,]. Several studies support the notion that addressing biophilic needs enhances individuals’ ability to achieve mindfulness [,] and promotes overall physical and mental well-being [,,]. This observation opens up potential avenues for future research to empirically investigate this relationship.

The results in Section 4 show that there are various architectural atmosphere features that promote mindfulness constructs. However, by focusing on design features that support multiple sensory experiences, which are core components of mindfulness, a pattern language for architectural design to foster mindfulness constructs can be summarized as follows [,]: in the element of Form, biomorphic shapes and the design employing distinct geometric architectural forms are significant, as they are found in the elements of Attention, Focus, and Connection. In the element of Space, the use of open space is significant, as it is found in the components of Awareness, Openness, and Attention. In the element of Movement, there are various approaches to promotion. In the element of Light, natural light plays a significantly promotive, role as it is found in the components of Attention and Connection. In the element of Color, there are various approaches to promotion. In the element of Material, there are various approaches to promotion. In the element of Object, natural landscape resources and the presence of windows are significant, as they are found in the components of Awareness, Attention, and Focus. In the element of View, there are various approaches to promotion. In the element of Sound, acoustics and the complexity of sound are significant, as they are found in the components of Attention and Connection. While various approaches have been employed to promote mindfulness constructs concerning the element of weather, the findings do not demonstrate any significant pattern of consistency.

Appendix F provides a detailed summary of these key architectural atmosphere characteristics that foster mindfulness constructs. However, these summaries are based on analyzing research articles published in academic databases. While research on the impact of architecture on human experience has advanced significantly, current studies have begun to incorporate biometric tools (e.g., eye-tracking, skin conductance) to objectively measure human responses to the built environment, an approach commonly referred to as Cognitive Architecture [,]. Therefore, to determine which of the identified characteristics genuinely influence mindfulness constructs, future studies should seek to provide empirical validation.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review identifies key architectural atmosphere characteristics that contribute to fostering mindfulness constructs: awareness, openness, attention, focus, and connection. The findings highlight the significant role of biophilic design, with recurring features such as biomorphic forms, open spaces, natural light, and views of nature, all of which support multiple sensory experiences central to mindfulness. Specific architectural elements found to be particularly influential include distinct geometric and biomorphic forms (supporting attention, focus, and connection), open space (supporting awareness, openness, and attention), natural light (supporting attention and connection), natural landscapes and windows (supporting awareness, attention, and focus), and acoustic complexity (supporting attention and connection). These findings provide a foundation for a pattern language in architectural design that promotes mindfulness through multisensory engagement.

However, these results are based on specific database searches and literature parameters, and future empirical studies are needed to validate the actual impact of these architectural characteristics on mindfulness, particularly through the lens of cognitive architecture, using biometric tools such as eye-tracking and skin conductance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T. and L.S.; formal analysis, S.P., D.W., S.S., P.P., S.B. and R.W.; methodology, C.T. and T.W.; supervision, S.B. and R.W.; validation, L.S. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang [Grant Number: KREF186810].

Data Availability Statement

The data from Scopus were accessed and obtained in February 2024, and they were extended in April 2025 for analysis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Pakin Anuntavachakorn, Panyaphat Somngam, and Noraphat Jerdkarn (data collector), Nongnapat Sap-umnoyporn and Chitsanupong Fusaeng (research assistant), and Karn Kuntichote (graphic designer).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Enhances Awareness.

Table A1.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Enhances Awareness.

| Article | Author | First-Author-Affiliation Country | Year | Source | Country of Publication | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tracing Persian influences: exploring the meaning of mosques and Mausoleums in south Sulawesi as iconic Islamic architecture. | Sutrisno, M. | Indonesia | 2023 | Journal of Islamic Architecture | Indonesia | 1 |

| The architectural material as palimpsest Monitoring climatic changes within the built environment. | Trif, S.-E. | Romania | 2023 | Argument | Romania | 7 |

| Effects of Multisensory Integration through Spherical Video-Based Immersive Virtual Reality on Students’ Learning Performances in a Landscape Architecture Conservation Course. | Wu, W. Zhao, Z. Du, A. Lin, J. | China | 2022 | Sustainability | Switzerland | 13 |

| On minimalism in architecture— Space as experience. | Vasilski, D. | Serbia | 2016 | Spatium | Serbia | 19 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Encourages Openness.

Table A2.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Encourages Openness.

| Article | Author | First-Author-Affiliation Country | Year | Source | Country of Publication | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploring Islamic vision on the environmental architecture of Traditional Javanese landscape: study of thematic tafseer Perspective. | Fajariyah, L. Halim, A. Rohman, N. Anwar, M. Z. Zulhazmi, A. Z. | Indonesia | 2023 | Journal of Islamic Architecture | Indonesia | 4 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Cultivates Attention.

Table A3.

Selected Articles on Architectural Atmosphere that Cultivates Attention.

| Article | Author | First-Author-Affiliation Country | Year | Source | Country of Publication | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of the Historical Gardens and Buildings Lighting Interaction through Virtual Reality: The Case of Casita de Arriba de El Escorial. | Gargiulo, M. Carleo, D. Ciampi, G. Masullo, M. Chìas Navarro, P. Maliqari, A. Scorpio, M. | Italy | 2024 | Buildings | Switzerland | 4 |

| Restoring the Mind: A Neuropsychological Investigation of University Campus Built Environment Aspects for Student Well Being. | Asim, F. Chani, P. S. Shree, V. Rai, S. | India | 2023 | Building and Environment | Netherlands | 26 |

| Designing with Nature: Advancing Three Dimensional Green Spaces in Architecture through Frameworks for Biophilic Design and Sustainability. | Zhong, W. Schroeder, T. Bekkering, J. | Netherlands | 2023 | Frontiers of Architectural Research | China | 36 |

| Elements of Biophilic Design Increase Visual Attention in Preschoolers. | Fadda, R. Congiu, S. Roeyers, H. Skoler, T. | Italy | 2023 | Buildings | Switzerland | 2 |

| AI-Based Environmental Color System in Achieving Sustainable Urban Development | Wang, P. Song, W. Zhou, J. Tan, Y. Wang, H. | China | 2023 | Systems | Switzerland | 18 |

| Spirituality of Light in the Mosque by Exploring Iranian–Islamic Architectural Styles. | Ghouchani, M. Taji, M. Yaghoubi Rooshan, A. H. | Iran | 2023 | Gazi University Journal of Science | Turkey | 4 |

| Fall Incidents and Interior Architecture— Influence of Executive Function in Normal Ageing | Chanbenjapipu, P. Chuangchai, W. Thepmalee, C. Wonghempoom, A. | Thailand | 2022 | Journal of Architectural/Planning Research and Studies (JARS) | Thailand | 5 |

| Nancy Art Nouveau Architecture | Krastiņš, J. | Latvia | 2023 | Architecture and Urban Planning | Latvia | 2 |

| A Passive Design Comfort Assessment Method of Indoor Environment | Kujundzic, K. Stamatovic Vuckovic, S. Radivojević, A. | Montenegro | 2023 | Sustainability | Switzerland | 30 |

| Pre-Evaluation method of the experiential architecture based on multidimensional physiological perception | Pei, W. Guo, X. Lo, T. | China | 2022 | Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering | Japan | 16 |

| Key Stylistic References in Public Facilities | Truspekova, K. K. Sharipova, D. S. | Kazakhstan | 2022 | Civil Engineering and Architecture | United States | 12 |

| Masonry in the Context of Sustainable Buildings: A Review of the Brick Role in Architecture | Almssad, A. Almusaed, A. Homod, R. Z. | Sweden | 2022 | Sustainability | Switzerland | 66 |

| Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability | Zhong, W. Schröder, T. Bekkering, J. | Netherlands | 2022 | Frontiers of Architectural Research | China | 394 |

| An architectural analytical study of contemporary minaret design in Kuwait | Alajmi, M. Al-Haroun, Y. | Kuwait | 2022 | Journal of Engineering Research | Kuwait | 15 |

| Discovering the Factor of the Bird’s Nest Stadium as the Icon of Beijing City | Lianto, F. Trisno, R. | Indonesia | 2022 | International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology (IJASEIT) | Indonesia | 3 |

| How do landscape elements affect public health in subtropical high-density city: The pathway through the neighborhood physical environmental factors. | Fang, Y. Que, Q. Tu, R. Liu, Y. Gao, W. | China | 2022 | Sustainable Cities and Society | Netherlands | 18 |

| Fractal Dimension Calculation and Visual Attention Simulation: Assessing the Visual Character of an Architectural Façade. | Lee, J. H. Ostwald, M. J. | Australia | 2021 | Buildings | Switzerland | 25 |

| Subjective experience and visual attention to a historic building: A real-world eye tracking study. | de la Fuente Suárez, L. A. | Mexico | 2020 | Frontiers of Architectural Research | China | 66 |

| Striking elements—A lifebelt or a fad? Searching for an effective way of adapting abandoned churches. | Szuta, A. F. Szczepanski, J. | Poland | 2020 | Frontiers of Architectural Research | China | 8 |

| Contemporary urban environment: the image of the history and the history of the image. | Dutsev, M. V. | Russia | 2021 | Atlantis Press | Netherlands | 2 |

| Iconic architecture and sustainability as a tool to attract the global attention. | Aatty, H. M. S. Al Slik, G. M. R. | Iraq | 2019 | IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering | United Kingdom | 10 |

| Concept of Organic Architecture in the Second Half of the XXth Century in the Context of Sustainable Development. | Bystrova, T. Y. | Russia | 2019 | IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering | United Kingdom | 11 |

| A Study of the Concept of Iranian Traditional Architecture in Bazaars and Shopping Centres | Sadafi, N. Sharif, M. | Malaysia | 2019 | Journal of Construction in Developing Countries (JCDC) | Malaysia | 6 |

| Tactile Architectural Models as Universal ‘Urban Furniture’ | Kłopotowska, A. | Poland | 2017 | IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering | United Kingdom | 8 |

| A Study on the Comparison of the Visual Attention Characteristics on the Facade Image of a Detached House Due to the Features on Windows. | Cho, H. | South Korea | 2018 | Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering (JAABE) | Japan | 16 |

| People’s evaluation towards media façade as new urban Landmarks at night | Vahedi Moghaddam, E. Ibrahim, R. | Malaysia | 2016 | Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research | Qatar | 17 |

| The sound of daylight: the visual and auditory nature of designing with natural light | Butko, D. J. | United States | 2011 | WIT Transactions on the Built Environment | United Kingdom | 7 |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Selected Articles on an Architectural Atmosphere that Supports Focus.

Table A4.

Selected Articles on an Architectural Atmosphere that Supports Focus.

| Article | Author | First-Author-Affiliation Country | Year | Source | Country of Publication | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping Architecture by Nature: Investigating Rewilding Architecture Design Methods. | Rahman, A. Paramita, K. D. Atmodiwirjo, P. | Indonesia | 2023 | Civil Engineering and Architecture | United States | 2 |

| Converging Directions of Organic Architecture and City Planning: A Theoretical Exploration. | Oliynyk, O. Amandykova, D. Konbr, U. Eldardiry, D. H. Iskhojanova, G. Zhaina, T. | Ukraine | 2023 | ISVS e-journal | India | 7 |

| Rethinking the Heritage through a Modern and Contemporary Reinterpretation of Traditional Najd Architecture, Cultural Continuity in Riyadh. | Moscatelli, M. | Saudi Arabia | 2023 | Buildings | Switzerland | 26 |

| Color in architecture From material appearance to chromatic concept. | Petre-Spiru, A. | Romania | 2023 | Argument | Romania | 15 |

| Mapping The Actual–Virtual in Architecture Exhibition. | Redyantanu, B. P. Yatmo, Y. A. Atmodiwirjo, P. | Indonesia | 2023 | Archives of Design Research | South Korea | 2 |

| Classification of Biophilic Buildings as Sustainable Environments. | Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I. Daugelaite, A. Viliunas, G. | Lithuania | 2022 | Buildings | Switzerland | 23 |

| The Impact of Indoor, Outdoor and Urban Architecture on Human Psychology. | Alharbi, S. Basaad, H. | Saudi Arabia | 2022 | Civil Engineering and Architecture | United States | 1 |

| The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. | Lee, K. | South Korea | 2022 | Buildings | Switzerland | 49 |

| The Connection between Architectural Elements and Adaptive Thermal Comfort of Tropical Vernacular Houses in Mountain And Beach Locations. | Hermawan, H. Švajlenka, J. | Indonesia | 2021 | Energies | Switzerland | 35 |

| The sense of entrance to a place in Kashan historical houses. | Danaeinia, A. | Iran | 2021 | Journal of Architecture and Urbanism | Lithuania | 7 |

| Masonry in the Context of Sustainable Buildings: Modernism and the Phenomenon of Kaunas. | Doğan, H. A. Laurinaitis, P. T. | Lithuania | 2021 | Architecture and Urban Planning | Poland | 23 |

| Cultural urban catalysts as meaning of the city. | Balvočienė, V. Zaleckis, K. | Lithuania | 2021 | Architecture and Urban Planning | Poland | 11 |

| The role of tacit knowledge in the formation and Continuation of architectural patterns case study: Garden-houses of Meybud, Iran. | Danaeinia, A. Hodaei, M. | Iran | 2019 | Journal of Architecture and Urbanism | Lithuania | 8 |

| The Beauty of Architectural complexity. | Barelkowski, R. | Szczecin | 2018 | International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics | United Kingdom | 8 |

Appendix E

Table A5.

Selected Articles on an Architectural Atmosphere that Fosters Connection.

Table A5.

Selected Articles on an Architectural Atmosphere that Fosters Connection.

| Article | Author | First-Author- Affiliation Country | Year | Source | Country of Publication | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Impact of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in Design Studios on the Comfort and Academic Performance of Architecture Students. | Al-Jokhadar, A. Alnusairat, S. Abuhashem, Y. Soudi, Y. | Jordan | 2023 | Buildings | Switzerland | 9 |

| Effect of a Microalgae Facade on Design Behaviors: A Pilot Study with Architecture Students. | Warren, K. Milovanovic, J. Kim, K. H. | United States | 2023 | Buildings | Switzerland | 6 |

| Window View Access in Architecture: Spatial Visualization and Probability Evaluations Based on Human Vision Fields and Biophilia | Parsaee, M. Demers, C. M. H. Potvin, A. Hébert, M. Lalonde, J.-F. | Canada | 2021 | Buildings | Switzerland | 12 |

| Architecture as a Consequence of Perception. | Skaza, M. | Poland | 2019 | Proceedings of EAAE/ARCC International Conference | Poland | 16 |

| History matters: the origins of biophilic design of Innovative learning spaces in traditional architecture. | Abdelaal, M. S. Soebarto, V. | Australia | 2023 | International Journal of Architectural Research (IJAR) | United States | 45 |

Appendix F

Table A6.

Summary of Shared Architectural Characteristics that Foster Mindfulness Constructs.

Table A6.

Summary of Shared Architectural Characteristics that Foster Mindfulness Constructs.

| Element | Attention | Openness | Awareness | Focus | Connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | dominant geometric forms | - | - | biomorphic | biomorphic shapes, forms dominate |

| Space | open space | open space without covering walls | openness, tactile spaces | - | - |

| Movement | no overlapping issues were found | ||||

| Light | natural lighting | - | - | - | natural light promoting positive emotions |

| Color | no overlapping issues were found | ||||

| Material | no overlapping issues were found | ||||

| Object | landscape elements, windows and doors (openings) | - | natural landscape resources | windows | - |

| View | no overlapping issues were found | ||||

| Sound | acoustic, acoustical intricacy | - | - | - | acoustics make architecture recognizable |

| Weather | no overlapping issues were found |

References

- St-Jean, P.; Clark, O.G.; Jemtrud, M. A Review of the Effects of Architectural Stimuli on Human Psychology and Physiology. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assem, H.M.; Khodeir, L.M.; Fathy, F. Designing for Human Wellbeing: The Integration of Neuroarchitecture in Design—A Systematic Review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A.; Alexander, C. Unified Architectural Theory: Form, Language, Complexity: A Companion to Christopher Alexander’s “the Phenomenon of Life—The Nature of Order, Book 1”; Vajra Books: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh, A.; Talmon, R.; Karp, O.; Amir, I.; Bar, M.; Grobman, Y.J. Affective Response to Architecture—Investigating Human Reaction to Spaces with Different Geometry. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2016, 60, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, M.; Neta, M. Humans Prefer Curved Visual Objects. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Llinares Millán, C.; Montañana i Aviñó, A.; Rojas, J.-C. Multisensory Stress Reduction: A Neuro-Architecture Study of Paediatric Waiting Rooms. Build. Res. Inf. 2019, 48, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Sun, C.; Zhou, X.; Leng, H.; Lian, Z. The Effect of Indoor Plants on Human Comfort. Indoor Built Environ. 2013, 23, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, J.A.; Nelson, W.C.; Burnett, R.T.; Aaron, S.; Raizenne, M.E. It’s about Time: A Comparison of Canadian and American Time–Activity Patterns. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2002, 12, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, C.; Stieb, D.; Davis, K.; Egyed, M.; Rose, A.; Chou, B.; Brion, O. Effects of Age, Season, Gender and Urban-Rural Status on Time-Activity: Canadian Human Activity Pattern Survey 2 (CHAPS 2). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 2108–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halat, D.H.; Soltani, A.; Dalli, R.; Alsarraj, L.; Malki, A. Understanding and Fostering Mental Health and Well-Being among University Faculty: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global Prevalence and Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, N.; Zhou, Z.; Tao, X.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, M. Symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Their Relationship with the Fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 Burden among Health Care Workers after the Full Liberalization of COVID-19 Prevention and Control Policy in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guégan, J.-F.; Suzán, G.; Kati-Coulibaly, S.; Bonpamgue, D.N.; Moatti, J.-P.; Guégan, J.-F.; Suzán, G.; Kati-Coulibaly, S.; Bonpamgue, D.N.; Moatti, J.-P. Sustainable Development Goal #3, “Health and Well-Being”, and the Need for More Integrative Thinking. Veterinaria México OA 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canada.ca. COVID-19: Current Situation. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331901/9789240003910-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Baminiwatta, A.; Solangaarachchi, I. Trends and Developments in Mindfulness Research over 55 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications Indexed in Web of Science. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 2099–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every Mind Matters. Find Your Little Big Thing for Your Mental Health. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for Its Salutary Effects. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Trombka, M.; Lovas, D.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Vago, D.R.; Gawande, R.; Dunne, J.P.; Lazar, S.W.; Loucks, E.B.; Fulwiler, C. Mindfulness and Behavior Change. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, E.; Schlosser, K.; Pandey, R.; Kumari, V. Coping with COVID-19: Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Mitigating Mental Health Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 563417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, K.; Harrison, M.; Adams, M.; Quin, R.H.; Greeson, J. Developing Mindfulness in College Students through Movement-Based Courses: Effects on Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy, Mood, Stress, and Sleep Quality. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 58, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristínardóttir, S.M. The Relationship Between Mindfulness and Mental Health. Bachelor’s Thesis, Reykjavik University, Reykjavik, Iceland, June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Almomani, E.Y.; Qablan, A.M.; Almomany, A.M.; Atrooz, F.Y. The Coping Strategies Followed by University Students to Mitigate the COVID-19 Quarantine Psychological Impact. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5772–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catling, J.C.; Bayley, A.; Begum, Z.; Wardzinski, C.; Wood, A. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Mental Health in a UK Student Sample. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolamo, G.; Cerveri, G.; Clerici, M.; Monzani, E.; Spinogatti, F.; Starace, F.; Tura, G.; Vita, A. Mental Health in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Emergency—The Italian Response. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 974–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality during COVID-19 Outbreak in China: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, R.; Agrawal, A.; Sharma, M. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2020, 11, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; et al. Mental Health Problems and Correlates among 746,217 College Students during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.E.; Soulliard, Z.A.; McCuddy, W.T.; Mahoney, J.J. Frequency and Perceived Effectiveness of Mental Health Providers’ Coping Strategies during COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5753–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P. Closure of Universities due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus 2020, 12, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Miller, J.G.; Hartman, T.K.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; Stocks, T.V.A.; et al. Anxiety, Depression, Traumatic Stress and COVID-19-Related Anxiety in the UK General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Goldberg, S.B.; Lin, D.; Qiao, S.; Operario, D. Psychiatric Symptoms, Risk, and Protective Factors among University Students in Quarantine during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Mishra, A. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress and Socio-Demographic Correlates among General Indian Public during COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, M.; Duhem, S.; Vaiva, G.; Baubet, T.; Habran, E.; Veerapa, E.; Debien, C.; Molenda, S.; Horn, M.; Grandgenèvre, P.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Disorders among University Students in France Confined during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact: Scientific Brief, 2 March 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Thampanichwat, C.; Moorapun, C.; Bunyarittikit, S.; Suphavarophas, P.; Phaibulputhipong, P. A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N.; Bramham, J.; Thomas, M. Mindfulness and design: Creating spaces for well being. In Proceedings of the 5th 102 International Health Humanities Conference, Sevilla, Spain, 15–17 September 2017; pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tezel, E.; Giritli, H. Understanding Sustainability Through Mindfulness: A Systematic Review. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Proceedings of the 3rd International Sustainable Buildings Symposium (ISBS 2017), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 15–17 March 2017; Fırat, S., Kinuthia, J., Abu-Tair, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere as mindful physical presence in space. OASE J. Archit. 2013, 91, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Teerapanyo, S.; Kumpeerayan, S.; Kaewkoo, J.; Sangsai, P. An Analytical on Jetiya in Thailand. JHUSO 2017, 8, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pagunadhammo, P.; Vichai, V.; Chanreang, T. The Analytical Study of The Buddhist Concept Appeared in The Pagodas in Chiang Sean City. JMND 2019, 6, 2444–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Porter, N.; Tang, Y. How Does Buddhist Contemplative Space Facilitate the Practice of Mindfulness? Religions 2022, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, Y. Designing Mindfulness: Spatial Concepts in Traditional Japanese Architecture; Japan Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiero, G. Affective Ecology as Development of Biophilia Hypothesis. Vis. Sustain. 2021, 16, 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Simon, M.; Fix, S.; Vivino, A.A.; Bernat, E. Exploring a sustainable building’s impact on occupant mental health and cognitive function in a virtual environment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, F. Architecture of Mindfulness: How Architecture Engages the Five Senses. Master’s Thesis, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thampanichwat, C.; Bunyarittikit, S.; Moorapun, C.; Phaibulputhipong, P. A Content Analysis of Architectural Atmosphere Influencing Mindfulness through the Lens of Instagram. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampanichwat, C.; Wongvorachan, T.; Sirisakdi, L.; Chunhajinda, P.; Bunyarittikit, S.; Wongmahasiri, R. Mindful Architecture from Text-To-Image AI Perspectives: A Case Study of DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. Buildings 2025, 15, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giluk, T.L. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction: Facilitating Work Outcomes Through Experienced Affect and High-Quality Relationships. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, G.; Foad, C.M.G.; Thorne, S. How do people conceptualize mindfulness? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.P.; Krompinger, J.; Baime, M.J. Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2007, 7, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J. Matters of mind: Mindfulness/mindlessness in perspective. Conscious. Cogn. 1992, 1, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, M.A.; Bishop, S.R.; Segal, Z.V.; Buis, T.; Anderson, N.D.; Carlson, L.; Shapiro, S.; Carmody, J.; Abbey, S.; Devins, G. The toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 1445–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.H.; Thatcher, J.B.; Klein, R. Using Information Technology Mindfully; SAIS 2007 Proceedings. 2007. Paper 1. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/sais2007/1 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E. The Art and Science of Mindfulness: Integrating Mindfulness into Psychology and the Helping Professions; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Inthuyos, P.; Karnsomkrait, L. Enhancing Ambience Product Derived from Clam State of Mind. J. Fine Appl. Arts Khon Kaen Univ. 2018, 10, 226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The System of Objects; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Tanizaki, J. In Praise of Shadows; Vintage Classics, Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmospheric Architectures: The Aesthetics of Felt Spaces; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere. In Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie; Universitätsbibliothek: Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsh, D. Atmosphere, mood, and scientific explanation. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 1154737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Rivera, A.; Ochoa, W.; Larrinaga, F.; Lasa, G. How-to Conduct a Systematic Literature Review: A Quick Guide for Computer Science Research. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, S.; Chen, K. Augmented and Virtual Reality (AR/VR) for Education and Training in the AEC Industry: A Systematic Review of Research and Applications. Buildings 2022, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettithanthri, U.; Hansen, P.; Munasinghe, H. Exploring the Architectural Design Process Assisted in Conventional Design Studio: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 1835–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, L.T.M.; Chakrabarti, A. DRM, a Design Research Methodology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Technische Universität Berlin. Description of the Systematic Literature Review Method. Available online: https://www.tu.berlin/en/wm/bibliothek/research-teaching/systematic-literature-reviews/description-of-the-systematic-literature-review-method (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Lame, G. Systematic Literature Reviews: An Introduction. Proc. Des. Soc. Int. Conf. Eng. Des. 2019, 1, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2016, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Lopes, M.; Fregni, F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: Implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- iLovePhD. List of Subject Areas Covered by Scopus Database. iLovePhD. 2021. Available online: https://www.ilovephd.com/list-of-subject-areas-covered-by-scopus-database/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Bhandari, P. A Beginner’s Guide to Triangulation in Research. Scribbr. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/triangulation/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Sutrisno, M. Tracing Persian Influences: Exploring the Meaning of Mosques and Mausoleums in South Sulawesi as Iconic Islamic Architecture. J. Islam. Archit. 2023, 7, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilski, D. On Minimalism in Architecture—Space as Experience. Spatium 2016, 36, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Du, A.; Lin, J. Effects of Multisensory Integration through Spherical Video-Based Immersive Virtual Reality on Students’ Learning Performances in a Landscape Architecture Conservation Course. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trif, S. The Architectural Material as Palimpsest. Monitoring Climatic Changes within the Built Environment. Argum. Spațiul Construit Concept Expresie 2023, 15, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajariyah, L.; Halim, A.; Rohman, N.; Anwar, M.Z.; Zulhasmi, A.Z. Exploring Islamic Vision on the Environmental Architecture of Traditional Javanese Landscape: Study of Thematic Tafseer Perspective. J. Islam. Archit. 2023, 7, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krastiņš, J. Nancy Art Nouveau Architecture. Archit. Urban Plan. 2023, 19, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutsev, M.V. Contemporary Urban Environment: The Image of the History and the History of the Image. IOP Conf. Ser. 2020, 775, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Guo, X.; Lo, T. Pre-Evaluation Method of the Experiential Architecture Based on Multidimensional Physiological Perception. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 1170–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatty, H.M.S.; Al Slik, G.M.R. Iconic Architecture and Sustainability as a Tool to Attract the Global Attention. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 518, 022076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłopotowska, A. Tactile Architectural Models as Universal “Urban Furniture”. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 082039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truspekova, K.K.; Sharipova, D.S. Architecture of Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Key Stylistic References in Public Facilities. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 3185–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, M.; Al-Haroun, Y. An Architectural Analytical Study of Contemporary Minaret Design in Kuwait. J. Eng. Res. 2022, 10, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianto, F.; Trisno, R. Discovering the Factor of the Bird’s Nest Stadium as the Icon of Beijing City. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2022, 12, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ostwald, M.J. Fractal Dimension Calculation and Visual Attention Simulation: Assessing the Visual Character of an Architectural Façade. Buildings 2021, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadafi, N.; Sharifi, M. A Study of the Concept of Iranian Traditional Architecture in Bazaars and Shopping Centres. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 23, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente Suárez, L.A. Subjective Experience and Visual Attention to a Historic Building: A Real-World Eye-Tracking Study. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 774–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. A Study on the Comparison of the Visual Attention Characteristics on the Facade Image of a Detached House due to the Features on Windows. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, F.; Chani, P.S.; Shree, V.; Rai, S. Restoring the Mind: A Neuropsychological Investigation of University Campus Built Environment Aspects for Student Well-Being. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Designing with Nature: Advancing Three-Dimensional Green Spaces in Architecture through Frameworks for Biophilic Design and Sustainability. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 732–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Biophilic Design in Architecture and Its Contributions to Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability: A Critical Review. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 11, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Que, Q.; Tu, R.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W. How Do Landscape Elements Affect Public Health in Subtropical High-Density City: The Pathway through the Neighborhood Physical Environmental Factors. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butko, D.J. The Sound of Daylight: The Visual and Auditory Nature of Designing with Natural Light. Light Eng. Archit. Environ. 2011, 121, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, M.; Carleo, D.; Ciampi, G.; Masullo, M.; Navarro, P.C.; Maliqari, A.; Scorpio, M. Assessment of the Historical Gardens and Buildings Lighting Interaction through Virtual Reality: The Case of Casita de Arriba de El Escorial. Buildings 2024, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, E.V.; Ibrahim, R. People’s Evaluation Towards Media Façade as New Urban Landmarks at Night. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet-IJAR 2016, 10, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Song, W.; Zhou, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, H. AI-Based Environmental Color System in Achieving Sustainable Urban Development. Systems 2023, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, R.; Congiu, S.; Roeyers, H.; Skoler, T. Elements of Biophilic Design Increase Visual Attention in Preschoolers. Buildings 2023, 13, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almssad, A.; Almusaed, A.; Homod, R.Z. Masonry in the Context of Sustainable Buildings: A Review of the Brick Role in Architecture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanbenjapipu, P.; Chuangchai, W.; Thepmalee, C.; Wonghempoom, A. A Review Article: Fall Incidents and Interior Architecture— Influence of Executive Function in Normal Ageing. J. Arch. Res. Stud. (JARS) 2022, 20, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouchani, M.; Taji, M.; Yaghoubi Roshan, A.H. Spirituality of Light in the Mosque by Exploring Iranian-Islamic Architectural Styles. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2023, 36, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystrova, T.Y. Concept of Organic Architecture in the Second Half of the XXth Century in the Context of Sustainable Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 481, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuta, A.F.; Szczepański, J. Striking Elements—A Lifebelt or a Fad? Searching for an Effective Way of Adapting Abandoned Churches. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaza, M. Architecture as a Consequence of Perception. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 022033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, M.S.; Soebarto, V. History Matters: The Origins of Biophilic Design of Innovative Learning Spaces in Traditional Architecture. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet-IJAR 2018, 12, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jokhadar, A.; Alnusairat, S.; Abuhashem, Y.; Soudi, Y. The Impact of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in Design Studios on the Comfort and Academic Performance of Architecture Students. Buildings 2023, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K.; Milovanovic, J.; Kim, K.H. Effect of a Microalgae Facade on Design Behaviors: A Pilot Study with Architecture Students. Buildings 2023, 13, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliynyk, O.; Amandykova, D.; Konbr, U.; Eldardiry, D.H.; Iskhojanova, G.; Zhaina, T. Converging Directions of Organic Architecture and City Planning: A Theoretical Exploration. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settl. 2023, 10, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre-Spiru, A. Color in Architecture. From Material Appearance to Chromatic Concept. Argum. Spațiul Construit Concept Expresie 2023, 15, 148–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. Rethinking the Heritage through a Modern and Contemporary Reinterpretation of Traditional Najd Architecture, Cultural Continuity in Riyadh. Buildings 2023, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I.; Daugelaite, A.; Viliunas, G. Classification of Biophilic Buildings as Sustainable Environments. Buildings 2022, 12, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.; Basaad, H. The Impact of Indoor, Outdoor and Urban Architecture on Human Psychology. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. Buildings 2022, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaeinia, A. The Sense of Entrance to A Place in Kashan Historical Houses. J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvočienė, V.; Zaleckis, K. Cultural Urban Catalysts as Meaning of the City. Archit. Urban Plan. 2021, 17, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Paramita, K.D.; Atmodiwirjo, P. Mapping Architecture by Nature: Investigating Rewilding Architecture Design Methods. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2023, 11, 2886–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, H.A.; Laurinaitis, P.T. Modernism and the Phenomenon of Kaunas. Archit. Urban Plan. 2021, 17, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H.; Švajlenka, J. The Connection between Architectural Elements and Adaptive Thermal Comfort of Tropical Vernacular Houses in Mountain and Beach Locations. Energies 2021, 14, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Philpapers.org. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/KELTBH?utm_source=nationaltribune&utm_medium=nationaltribune&utm_campaign=news (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Joye, Y.; De Block, A. “Nature and I Are Two”: A Critical Examination of the Biophilia Hypothesis. Environ. Values 2011, 20, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, G. Biophilia and Gaia. Two Hypotheses for an Affective Ecology. J. Bio-Urbanism 2011, 1, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. The Potential of Biophilic Fractal Designs to Promote Health and Performance: A Review of Experiments and Applications. Sustainability 2021, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.H. Human-Nature for Climate Action: Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]