Abstract

Housing informality in Morocco has taken root within Rabat’s formal neighborhoods, quietly reshaping façades, extending plot lines, and redrawing the texture of entire blocks. This ongoing transformation runs up against the rigidity of official planning frameworks, producing tension between state enforcement and tacit tolerance, as residents navigate persistent legal and economic ambiguities. Prior Moroccan studies are neighborhood-specific or socio-economic; the field lacks a city-wide, multi-class analysis linking everyday tactics to long-term governance dilemmas and policy design. The paper, therefore, asks how and why residents and architects across affordable, middle-class, and affluent districts craft unapproved modifications, and what urban order emerges from their cumulative effects. A mixed qualitative design triangulates (i) five resident focus groups and two architect focus groups, (ii) 50 short, structured interviews, and (iii) 500 geo-referenced façade photographs and observational field notes, thematically coded and compared across housing types. In addition to deciphering informality methods and impacts, the results reveal that informal modifications are shaped by both reactive needs—such as accommodating family growth and enhancing security—and proactive drivers, including esthetic expression and real estate value. Despite their legal ambiguity, these modifications are socially normalized and often viewed by residents as value-adding improvements rather than infractions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

Although housing informality is frequently relegated to the peripheries of urban discourse—both spatially and administratively—seminal scholarship has long disrupted this reductive association, illustrating that informality possesses an intrinsic rationale and is, in many contexts, deeply embedded within the operational frameworks of the formal urban economy [1,2,3]. Recent research shows that informal changes are common even within formally designed neighborhoods [4]. Inhabitants often adapt their homes to meet cultural habits, daily needs, or economic pressures [5,6,7]. These changes, which include additions, enclosed balconies, or interior adjustments, are usually made without legal approval but can significantly alter the urban fabric over time [8].

In Morocco, resident-driven changes to formal housing show that informality is not limited to the urban margins. Scholars have traced how families adjust interiors to fit extended kin, carve out rental units, or express social ambitions. In Kenitra’s public housing, for instance, residents commonly install balcony kitchens, build rooftop platforms for water tanks, or fence shared courtyards to regain essential functions. In Kenitra, families living in social housing adjusted their homes to make up for the lack of basic services. They added features such as kitchenettes on balconies, platforms for water tanks on rooftops, and fences around courtyards [9]. In response to poor communal conditions in M’sila, residents turned informal spaces such as rooftops and pavements into practical extensions of their homes [10,11]. Meanwhile, in Daksi, Constantine, the residential function of many buildings gave way to business use. This led to growing friction over sidewalk access, ambient noise, and the loss of intimate domestic boundaries [12].

In several North African cities, housing informalities follow similar patterns. In Constantine, parcels were informally divided before any official urban plans were implemented, triggering waves of spontaneous construction just ahead of each legalization period [13,14]. According to surveys in Diar Zitoun, 62% of respondents supported the idea of legalizing their unauthorized homes, while 27% favored removal or relocation [15]. These choices often depended on the physical layout and condition of the units. Although authorities have launched several demolition campaigns in Ouad El Had over the past decade, informal housing still reappears. This resilience stems from strong family ties and a common hope that formal recognition may follow [16]. In most of these contexts, authorities focus mainly on punitive actions such as demolitions, financial penalties, and evictions, while paying limited attention to measures that could protect or mediate informal housing practices [17].

Beyond the Maghreb, comparative research underscores that formal housing frequently diverges from its authorized blueprint. Cairo’s residents have used small interventions like moveable seats, painted sidewalks, and lightweight kiosks to reinforce informal uses of space while avoiding full-scale redevelopment [18]. In Buru-Buru, Nairobi, families have enclosed open spaces and expanded vertically to adapt inherited Modernist layouts to local social norms [19]. archeological findings in Ethiopia reveal that what are often labeled as “irregular” settlements have long-standing adaptive logics rooted in history. This perspective questions the view that informal development is disordered or accidental [20]. Around the world, small-scale changes—such as enclosing a balcony for better ventilation during health emergencies [21] or building a partition in a backyard to support informal businesses [7]—show how everyday people find ways to adapt despite rigid regulations [22,23,24].

In Moroccan studies of housing informality, three key gaps continue to shape the field. First, while several neighborhood-level investigations exist [25,26,27], they do not explain how scattered and incremental changes combine to form larger urban patterns. Second, although researchers have emphasized the need for ethnographic work that follows informal practices from households to urban planning institutions [24,28], no Moroccan research has yet mapped this path in detail. As a result, informal modifications are rarely traced through the administrative stages of permit approval, and policies often shift between strict enforcement and quiet acceptance [29]. Third, despite growing evidence on how social ties and market aims interact, studies in Morocco have yet to examine these factors jointly across all income levels [30,31,32]. This study addresses these gaps with a metropolitan, cross-class investigation (affordable, middle-class, and affluent housing) of how informal modifications interact with long-term governance imperatives and regulatory pressures. Rather than praising informal practices, this research explores which changes help families cope and which may lead to unfair or unsafe outcomes. The section that follows introduces key terms such as quiet reshaping, tacit tolerance, and the back and forth between formal rules and everyday needs.

1.2. Key Concepts

1.2.1. Quiet Reshaping

Within the study of urban informality, quiet reshaping denotes a subdued yet sustained spatial process wherein residents, circumventing bureaucratic procedures, undertake architectural adjustments in direct response to evolving domestic or communal needs. These adaptations—frequently nuanced and architecturally consonant with the surrounding structures—include practices such as incremental extensions and subtle reconfigurations [19,33].

1.2.2. Tacit Tolerance

In settings where spatial alterations proceed without official authorization yet become socially accepted or politically overlooked, state institutions frequently adopt what we can be described as tacit tolerance. This stance entails a strategic decision not to enforce regulations, whereby the lack of legal permits is met with a conscious choice to avoid sanctions. Such environments generate a blurred legal landscape in which governmental silence becomes a functional mode of control, enabling informal practices to persist within planning systems that appear formally regulated [29].

1.2.3. Adaptive Transformation and the Expression of Cultural Identity

Residents’ frequent deployment of informal modifications in formally developed housing illustrates an effort to reconcile shifting cultural identities, unstable economic contexts, and inflexible regulatory boundaries. Dovey conceptualized this informal agency in spatial terms [34], a theoretical stance reinforced by canonical works that reveal how such practices endure in settings governed by restrictive planning paradigms [6,8,22]. The self-built extensions in Buru-Buru, Nairobi, show how families reshape modernist dwellings to reflect local traditions [35], just as façade modifications in Brazilian tract housing highlight the influence of aspiration in informal design [36]. According to recent studies, these practices meet pressing household needs and, at the same time, play an active role in reshaping the urban fabric, deeply embedded in lived realities [5,7,28].

1.2.4. Negotiation Between Formal Regulations and Lived Realities

In formal settings, housing informality emerges as a dynamic negotiation between strict regulatory systems and the practical demands of everyday life. Though buildings are typically constructed in line with formal regulations, multiple sources, including official field studies, show that residents frequently modify them beyond their original blueprints [13,37]. What Scott sees as the collapse of legibility [23], and Roy frames as “informalization” [6], Sassen deepens by showing how such spatial practices forge alternative terrains of political belonging and action within regulated urban space [38]. Their flexibility partly emerges from the ongoing push and pull between centralized control and community-led adaptation [7,28].

1.3. Research Gaps

Although global scholarship on informality is extensive, Moroccan research and policy face three interrelated gaps.

1.3.1. From Micro Case-Studies to City-Wide Evidence

Though grounded in neighborhood-level inquiry [25,26,39], existing studies fail to offer a city-wide analysis of how informal modifications cumulatively affect urban housing governance.

1.3.2. Linking Everyday Tactics to Regulatory Impasses

Roy [24] and McFarlane [28] advocate for ethnographies that follow residents as they negotiate state regulation. In Morocco, however, no existing study captures informal transformations from the household scale to the permit desk, resulting in reactive planning that swings between repression and passive tolerance.

1.3.3. Intersecting Socio-Cultural Motives with Market Logics

At the junction of cultural imperatives and economic needs, informal practices develop, shaped by the desire for extended family space and social recognition [7,32], alongside market speculation and livelihood strategies [30,31]. Rabat lacks a unified study that addresses these drivers across different social classes.

This study offers a metropolitan, cross-class investigation (affordable, middle-class, and affluent housing) of how informal modifications interact with long-term governance and regulatory pressures. Rather than celebrating informality wholesale, it identifies spatial responses that strengthen resilience while flagging those that erode equity or safety, contributing to Morocco’s evolving toolkit for differentiated regularization.

Two essential questions guide this study. One examines the cultural and economic drivers behind informal housing changes across income groups, “Which socio-cultural and economic logics underwrite informal modifications across income strata?” and the other explores how these drivers are materialized incrementally in the built environment, at the level of the dwelling, the street-facing edge, and the surrounding public space: “How are those logics spatialized through incremental, material acts at the scale of the plot, frontage, and street?” These questions are posed to better understand the relationship between small-scale informal actions and broader tensions within urban governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Design Logic

Building on the theoretical underpinnings of assemblage urbanism [8] and enhanced by discourses surrounding everyday governance [6,37], this research conceptualizes informality as a spatial practice of negotiation. Challenging the presumed formal and informal boundary reframes these categories as fluid and interwoven. To capture both the underlying rationales (why people build) and their physical outcomes (what they build), we paired:

- Actor-centered techniques—resident focus group discussions and structured interviews with residents.

- Metropolitan morphological scans—geolocated housing photographs and diachronic Google Earth imagery (2005–2025).

This study used a triangulated evidence base to satisfy Gilbert’s criteria for rigorous methodology [40], adhere to Devlin’s principles for validating findings [41], and engage directly with the issues raised by Deboulet regarding the disconnect between regulatory systems and lived realities [42]. Focus-group responses revealed culturally informed motivations behind informal housing actions, consistent with analyses from Varley [7] and Chiodelli [4]. To reinforce empirical triangulation and deepen interpretive understanding, the study followed up with individual interviews. Deboulet [42] underscored the need to examine the everyday as a way to capture the subtle shifts occurring within formal planning systems. This study applied real-time observational tools, including targeted photography and localized visual mapping, following the methodological framework proposed by Mrani et al. [39]. The research was rooted in assemblage theory, which understands informal housing modifications as outcomes of interconnected relationships rather than individual regulatory breaches. These relationships include the exchange between built forms, household needs, cultural values, and policy structures. In line with this approach, we designed a data collection method that included field observation at both small and large scales, visual recordings over time, and interviews that captured the motivations and timing of informal actions. These combined methods helped demonstrate how repeated practices gradually transform urban space.

2.1.2. Data Collection Instruments

This section details the three primary instruments used in the empirical investigation: focus-groups (with residents and architects), a visual archive (comprising street-level photographs and diachronic satellite imagery), and structured interviews (with individual residents across socio-economic strata).

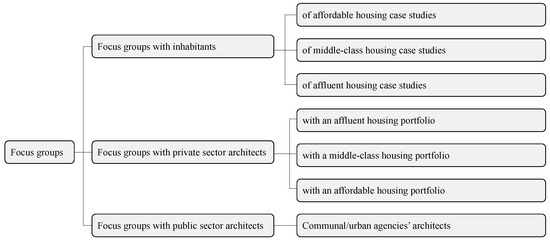

Focus group notebooks: seven in total, comprehending three resident focus groups (n = 9), three architect focus groups of the private sector (n = 9), and one architect focus group of the public sector (n = 3); about thirty-five pp.

Audio recording was intentionally avoided to maintain a welcoming environment for participants and to promote openness. In place of recordings, the first author documented the discussions through detailed handwritten notes. These were later typed, enriched, and reviewed systematically using Freeform on an iPad to ensure a full account of participant input. While this method captured essential content, the absence of audio may have restricted the retention of exact language and emotional undertones. Although key points were noted as closely as possible to the original wording, some expressive subtleties might have been lost. This compromise was necessary to build confidence among participants, especially when discussing informal housing actions. The conversations explored collective spatial reasoning, following the guidance of Mrani et al. [43] in the Rabat context [27].

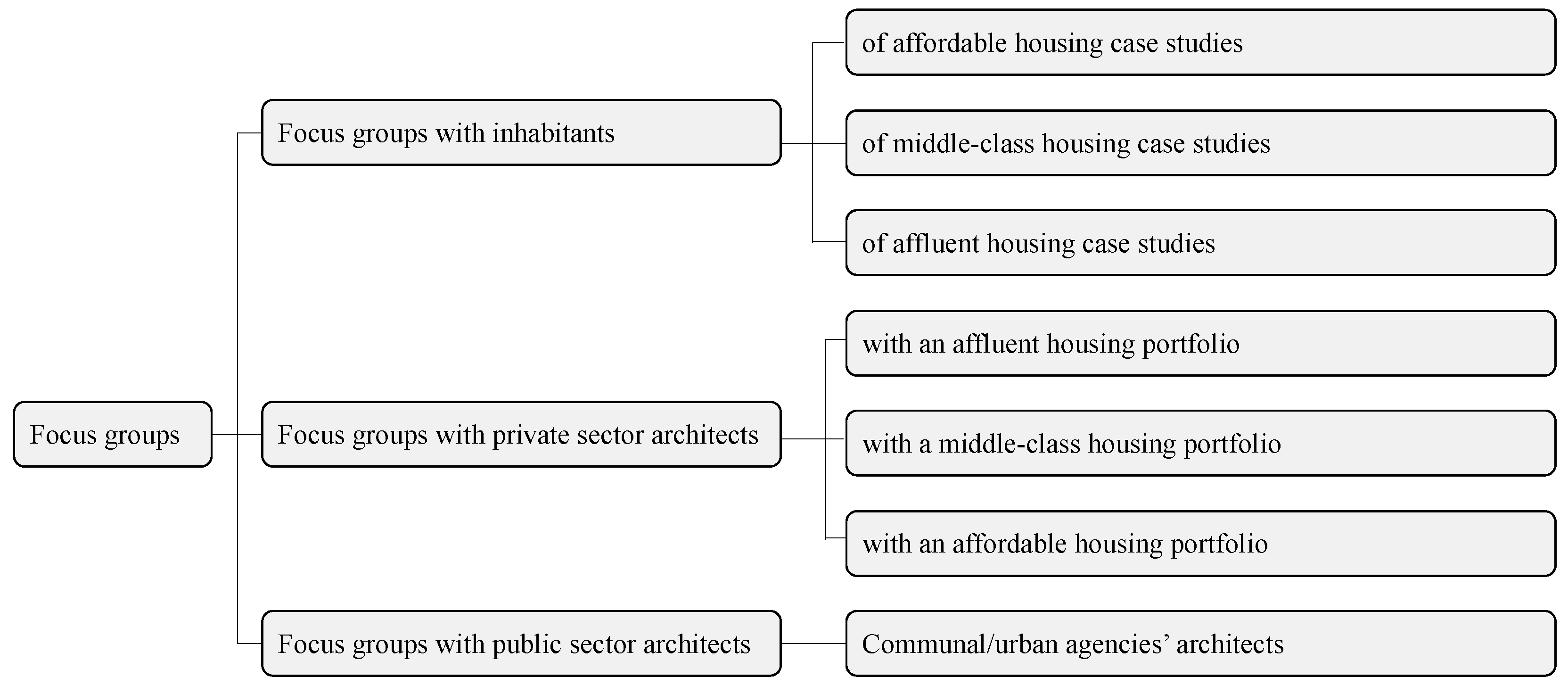

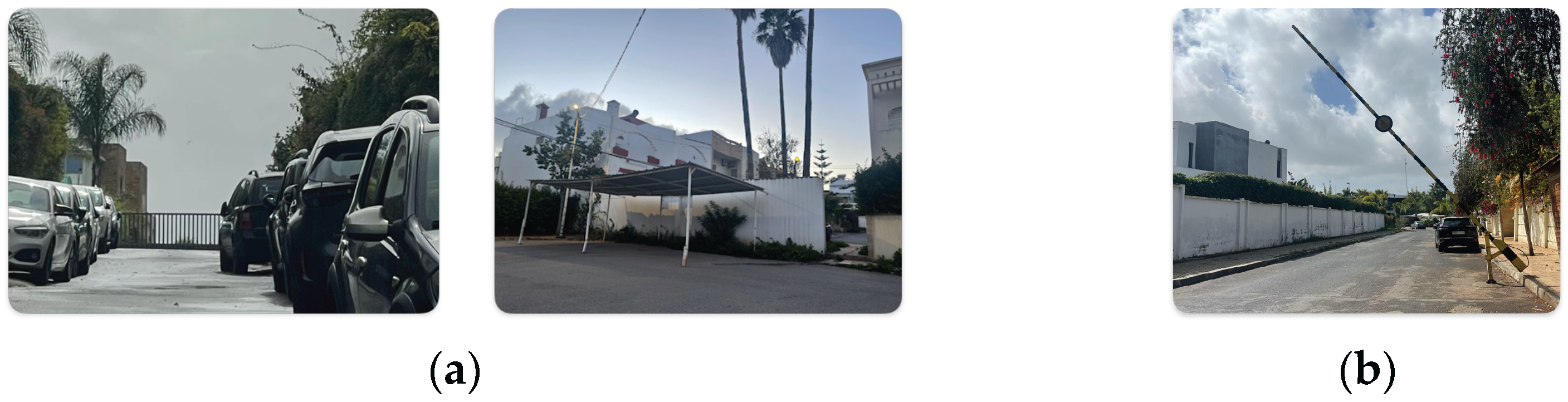

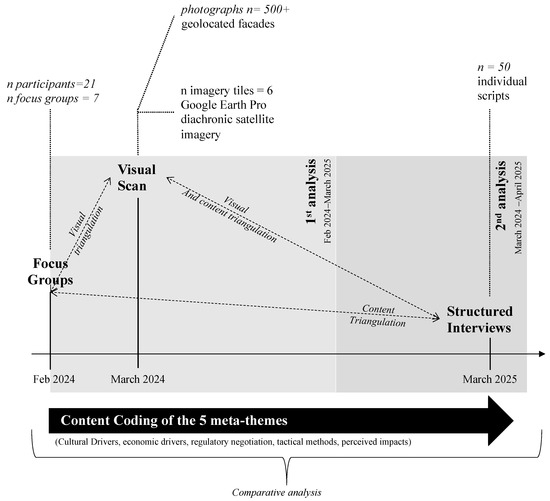

An excellent groundwork of methodology anticipation is essential to ensure successful conduct and qualitative data products of the focus groups [44]. As shown in Figure 1, the groundwork reflects both the conceptual and chronological structure of the two focus groups. The conceptual dimension highlights the foundational logic behind the sessions held with residents in person and those conducted online with architects. Face-to-face focus groups with the inhabitants ought to bring clarity towards how the inhabitants think of and feel about informalities of housing [45], therefore contextualizing their behavior towards this matter [46] and enlightening the drivers behind it in each one of the three housing contexts, making feasible a cross-check analysis of the sociocultural similarities and disparities. On the other hand, online focus groups with the architects composed of architects working in the private sector link the results (chronological organization) obtained from the inhabitants to their everyday professional practices, and the focus groups composed of architects working in the public sector link the results obtained from both parties (conceptual and chronological organization) to the regulatory policies in force to clarify deployed architectural maneuvers in tandem with compliance or hostility towards the formal framework. Hence, for a total of three different socioeconomic contexts and two categories of architects, we explore seven FGs, one for each context (affordable, midrange, and affluent), one for each socioeconomic portfolio (architects each with a portfolio of housing projects with affordable, middle-class, and affluent dimensions), and one for the public sector architects, investigating the relationship between regulations and professional practice. Furthermore, each FG is composed of three participants. Conducting small focus groups with only three participants is a well-supported method in qualitative research, especially when dealing with sensitive issues such as informal housing changes. Smaller groups ease social tension and create an atmosphere where participants feel safe to share openly. This is particularly important when the topic involves potentially illegal or morally complex actions. Toner noted that very small focus groups often produce rich, context-specific insights, especially from individuals with limited structural power or those who tend to speak less [47]. Wheelan also found that groups of three often achieve a higher level of focus and cohesion [48]. In this study, this format worked well, allowing both residents and architects to share thoughtful reflections on how they adapt spaces and deal with building regulations.

Figure 1.

Organization of the seven focus groups composed of inhabitants and architects.

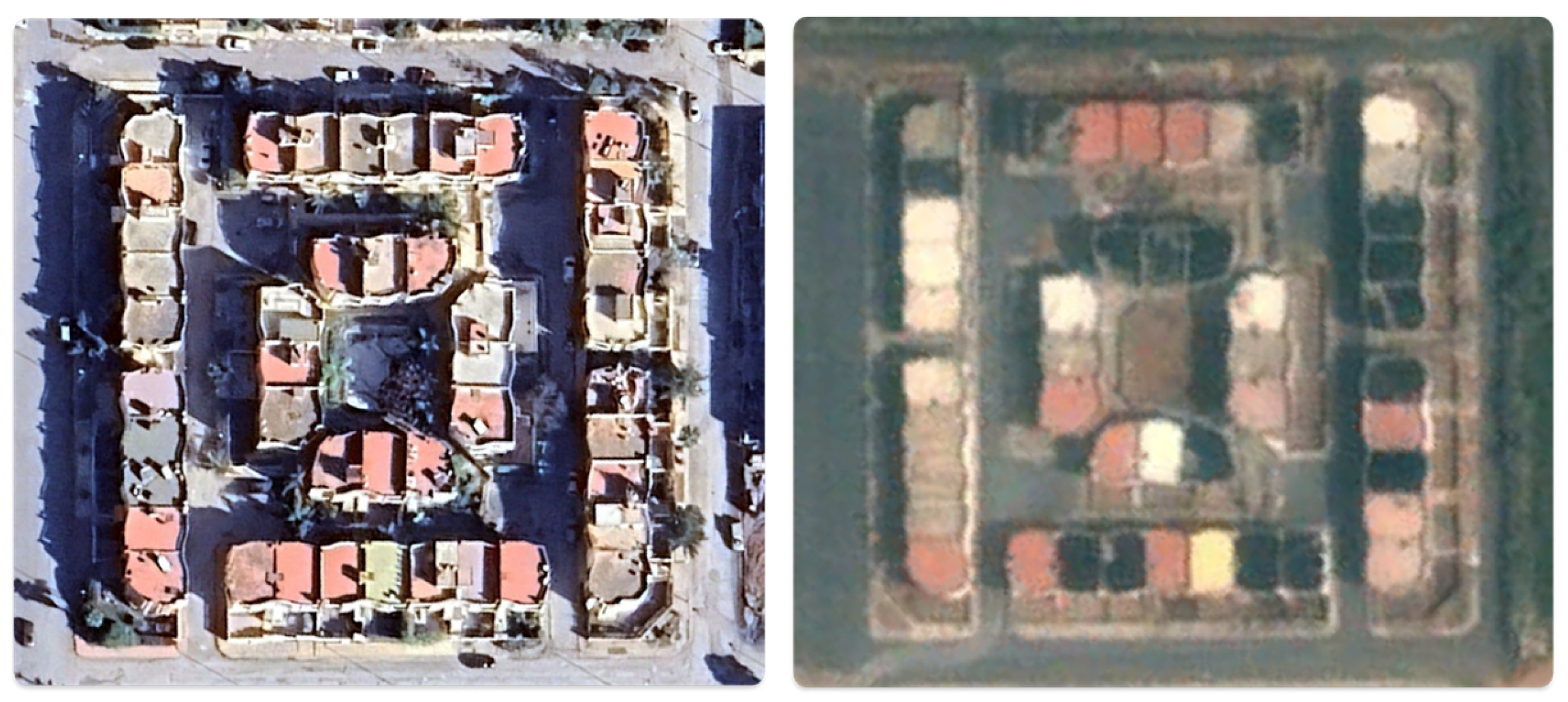

Visual archive: Over 500 geolocated facade photographs (captured in March 2024) were analyzed from April 2024 to March 2025, and 6 Google Earth Pro diachronic satellite imagery tiles from 2005 to 2025 were investigated in April 2025. Following methodological precedents from Sietchiping [49], spatial documentation was critical for corroborating declared practices with material transformations.

This research employed historical satellite images available through Google Earth. These images were sourced from high-resolution providers, notably Maxar Technologies (from 2005 to 2018) and Airbus (from after 2018 through 2025). The spatial resolution of these images ranges from approximately 0.3 to 0.5 m per pixel, varying by satellite and year of acquisition. The clarity is sufficient to detect large-scale spatial transformations, such as vertical extensions, the building of pools, or the lengthening of driveways. However, smaller and more nuanced modifications—such as the installation of rooftop sheds, changes in façade texture, or short-term additions—are beyond the resolution’s scope. Satellite imagery was therefore used to establish broader trends in informal growth over time. Detailed features were recorded through on-site photography and field observation. These photographs are typical street-level images and do not come with scale calibration. Since determining exact dimensions from them would be speculative, the research approach favored pattern recognition and spatial reading over precise measurement.

Structured interview sheets: Fifty individual scripts (10–15 min each) were collected during March–April 2025 and analyzed immediately thereafter. Goytia et al. emphasized the necessity of multi-scalar data to avoid homogenizing informal behaviors [50].

The research timeline and data collection methods were not limited by COVID-19 measures. Fieldwork was conducted between February 2024 and April 2025, a period during which Morocco had lifted all pandemic-related restrictions. This enabled full face-to-face engagement with participants through focus groups, structured interviews, and field observation.

2.1.3. Analytical Categories: Reactive and Proactive Modifications

The study distinguishes between two types of housing modifications, which are defined as reactive and proactive, depending on what motivates them and when they are carried out.

- The term reactive modifications refers to informal changes that respond directly to immediate spatial or social pressures. Such pressures may stem from family growth, the demand for more privacy, or the absence of necessary domestic infrastructure. These changes are commonly implemented with little delay, limited funding, and minimal formal design. Example: A hastily enclosed balcony to accommodate a growing family.

- Proactive forms of housing modification reveal a deliberate and aspirational logic. These changes are typically motivated by a desire to increase long-term property worth, improve residential comfort, or elevate the building’s appearance. They are usually pre-planned, carried out over time, and require more resources and purposeful design strategies. Example: Constructing a landscaped entrance or rooftop terrace to increase resale appeal or convey status.

2.1.4. Expected Outcomes

Reactive needs: This investigation expects to uncover three thematic strands that recur across cases of resident-led departures from prescribed housing blueprints, a phenomenon well-documented in the works of Maina [51], Fombe [52], and Bayat [53].

Proactive drivers: Beyond responding to urgent material needs, inhabitants frequently act with strategic intent, seeking to maximize profit, elevate their public image, and produce spatial forms that resonate with individualized esthetic values [19,54,55].

Operational methods: Field observations are anticipated to align with patterns of timely contextual adaptation, strategic labeling, and phased or additive temporal practices [22,56,57].

Impacts: We anticipate a mixed ledger of outcomes: economic affordability versus tax erosion, social cohesion versus conflict, governance gray zones, and safety concerns [31,58,59,60].

2.2. Sample Recruitment and Case Selection

Residents: Because no official roster of households exists, resident participants were enlisted through street-intercept convenience sampling [61], supplemented by a single-wave snowball extension [62]. During February 2024, the first author approached passers-by in high-footfall public nodes—neighborhood markets, bus terminals, and coastal promenades—distributed across the six study territories (Hassan, Salé, Temara, Agdal, Harhoura, and Souissi). A brief screener established that each person lived or worked in one of the territories and had first-hand experience with dwelling modifications. At the end of each session, participants were invited to nominate one additional neighbor or relative, broadening the socio-cultural spread while remaining within the same territories. Those who qualified were invited to participate directly in a nearby focus group (February 2024); the same intercept-plus-nomination protocol was reused in March 2025 for the structured interviews. While the intercept method succeeded in reaching many residents involved in informal housing practices, it does present some challenges. The people who chose not to take part may differ in background or perspective from those who did, which could influence how well the findings reflect broader patterns. According to Graham et al., physical appearance and other visible traits may affect who participates [63]. Golinelli et al. also highlighted that relying on public spaces can exclude those who are less present outdoors, including older individuals or caregivers [64]. To limit such bias, the research took place at multiple sites and at various times. Snowball sampling further supported outreach to participants who would not have been encountered in public settings.

Architects: Professional voices were captured through criterion-based purposive sampling [65]. Leveraging the first author’s network, we invited licensed architects who (i) have practiced for at least five years in the Rabat–Salé–Temara metropolitan area and (ii) possess a portfolio of planning-compliant residential projects. Twelve architects accepted and were organized into four architect-only focus groups (three from the private sector and one from the public sector) so that professional narratives remained distinct from lay perspectives. The selection of architect participants followed two main criteria. First, they needed experience in designing or reviewing residential buildings in Rabat and its nearby cities. Second, they had to be familiar with how residents make their own changes to their homes. The team reached out to architects who had worked in the six neighborhoods studied: Hassan, Salé, Temara, Agdal, Harhoura, and Souissi. These professionals had often been involved in building permits, renovations, or evaluations after residents moved in. Their views added depth to the research by showing how official designs are adapted in real life. They helped connect resident stories with professional observations of informal changes.

Spatial cases: For ground photography and satellite checks, maximum-variation sampling [65] secured contrast across socio-economic strata, housing typologies, and morphologies. While formal housing developments generally adhere to governmental regulations, various socio-economic factors—such as affordability constraints, fluctuating incomes, and demographic shifts—drive adaptations that blur the line between formal and informal construction [35,66,67]. In Morocco, residents frequently alter their homes to accommodate extended family structures or to create income through rental units [25,26,68]. These informal tendencies are not confined to Morocco. Chagas Cavalcanti proposed formalizing Brazil’s informal solutions [69], De Sotto championed Peru’s progressive home-building as a path to economic empowerment [66], and Makachia observed their defensive role in Kenya’s eviction-prone settlements [35]. In the United States, informal accessory-dwelling units are affordable tools and wealth-building devices [54]. This pattern reinforces informality as a response to market exclusion and a proactive socio-economic strategy [22,67]. Income categories were defined using a mix of local real estate indicators, official housing policy terms, and visible urban features. Affordable areas were typically made up of government-supported or low-income housing with limited plot sizes and minimal infrastructure. Middle-class zones featured privately developed homes with medium-sized plots and varied ownership. In affluent neighborhoods, housing consisted of expansive villas and secure residences.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

The research process began in February 2024 with three focus group discussions involving residents. Participants were between 18 and 59 years of age, with equal attention to gender representation. All were drawn from neighborhoods located near the recruitment sites. Each focus group consisted of three individuals, and the sessions were conducted over a period lasting between 60 and 90 min. This method followed the guidelines of Devlin [41] and Varley [7], who highlighted the value of understanding shared meanings within different socio-economic settings. During the same month, four focus groups with architects were conducted online via Google Meet. Each session brought together three architects, aged between 30 and 44, with a balance of male and female participants. These meetings typically lasted from 100 to 120 min. This portion of the research was informed by Porter et al.’s framework [59], which sees professional insights as essential for making sense of the logic behind informal urban changes. In March 2024, over 500 photographs with embedded geolocation data were taken across six different sites. The goal was to document informal spatial alterations, such as the use of rooftops, changes in boundary design, and modifications to front facades. In April 2025, the team used Google Earth Pro to analyze satellite images from 2003 to 2025, enabling a detailed comparison of spatial changes over time. In March 2025, a series of fifty face-to-face structured interviews were conducted with men and women aged 18 to 59. Each interview lasted between ten and fifteen minutes. These sessions explored personal housing histories, financial access strategies, and experiences dealing with formal regulation. The interviews were included to broaden the scope of perspectives and to add depth to the data collected during the group sessions. This approach was consistent with the principles developed by Goytia and Pasquini [70]. A single discussion guide was used across all data collection formats, aiming to investigate cultural drivers, economic justifications, spatial approaches, and strategies of regulatory avoidance. All field notes were expanded on the same day and later coded according to major themes.

2.4. Data Analysis Strategy

Data analysis was performed in the following stages:

Content coding: Interview/focus group notes coded for five meta-themes (cultural drivers, economic drivers, regulatory negotiation, tactical methods, and perceived impact).

Visual triangulation: Coded narratives were matched with photographic and satellite-based visual records to verify when and how spatial modifications occurred. This method, consistent with Ijeoma and Saidu [71], highlights the value of visual triangulation in capturing post-occupancy dynamics.

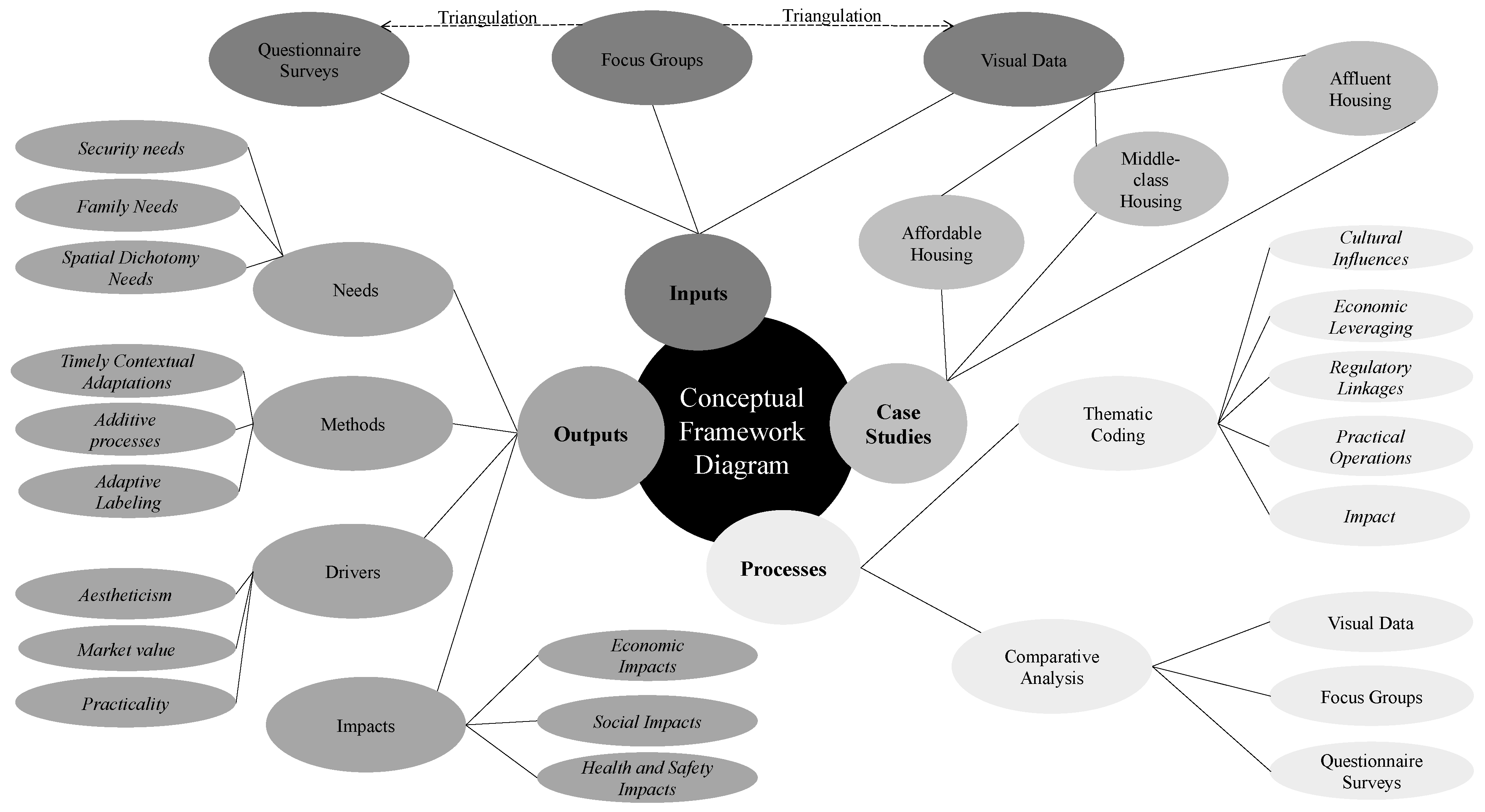

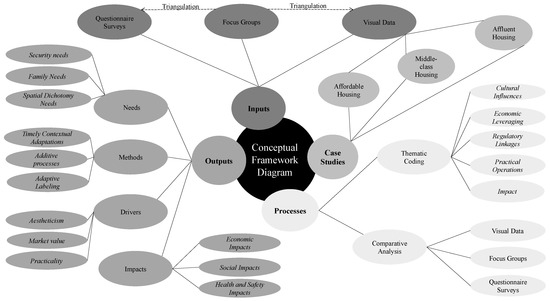

Comparative synthesis: Cross-tabulation by income stratum and housing type highlighted standard repertoires versus context-specific maneuvers; the results fed into the study’s conceptual framework diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework diagram.

The qualitative data were coded manually using a structured thematic approach. This framework emerged from early field observations and was refined through multiple readings of the transcripts. Five overarching themes were used to guide a consistent coding matrix. Although no specialized software such as NVivo or ATLAS.ti was employed, coding was carefully carried out using color tags in the Freeform app on iOS. A spreadsheet supported the process by enabling cross-tabulation for pattern comparison. Photographs of façades and time-series satellite images were annotated and integrated into the dataset to support triangulation.

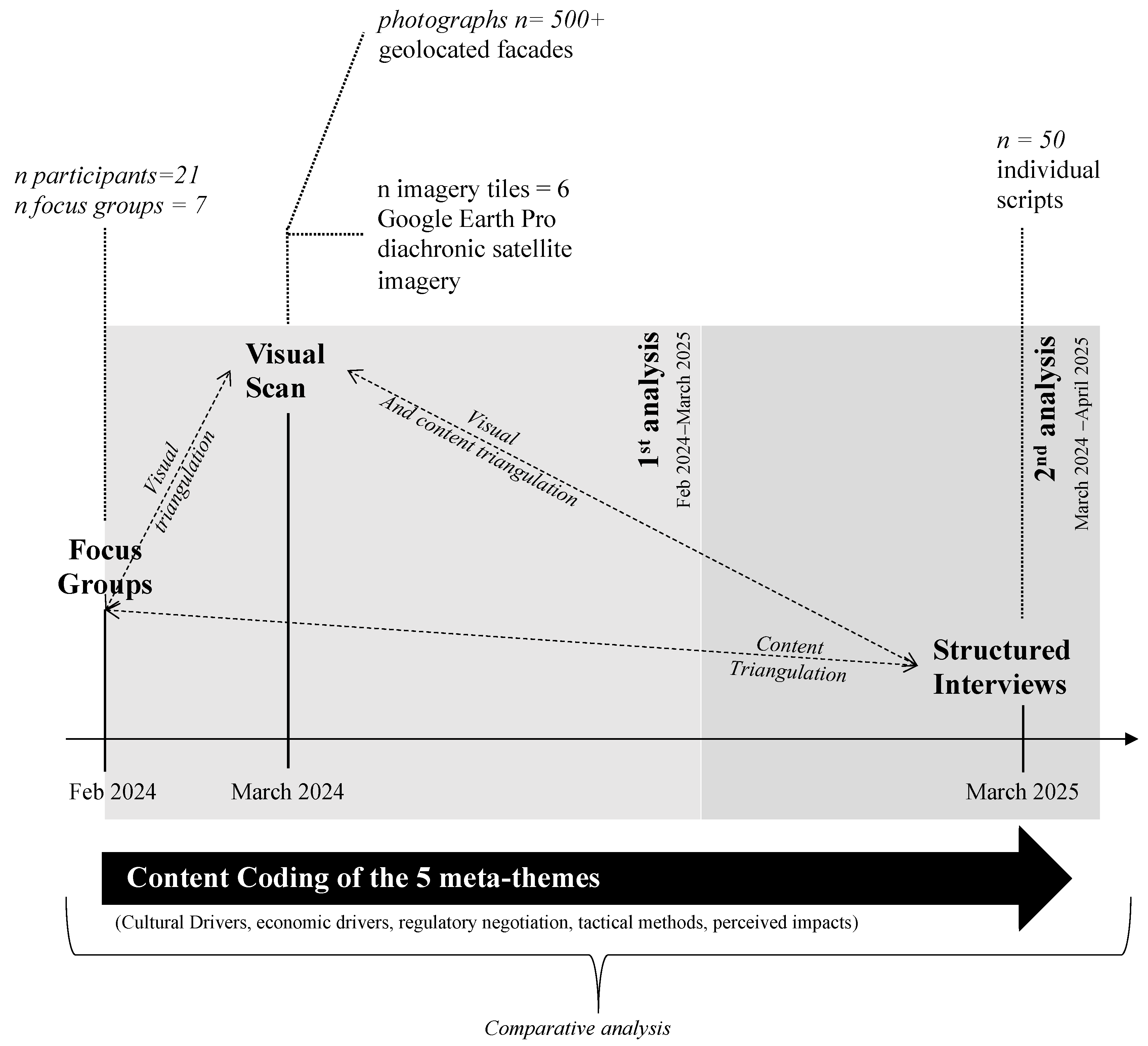

This mixed-method approach, synthesized in Figure 3, generates a rich, layered account centered on actors’ perspectives. It traced the subtle reshaping of formal housing throughout Rabat’s class-based settings.

Figure 3.

Data analysis synthesis of the mixed-method approach comprehends the datasets and data collection timeline.

Coding Consistency and Reliability

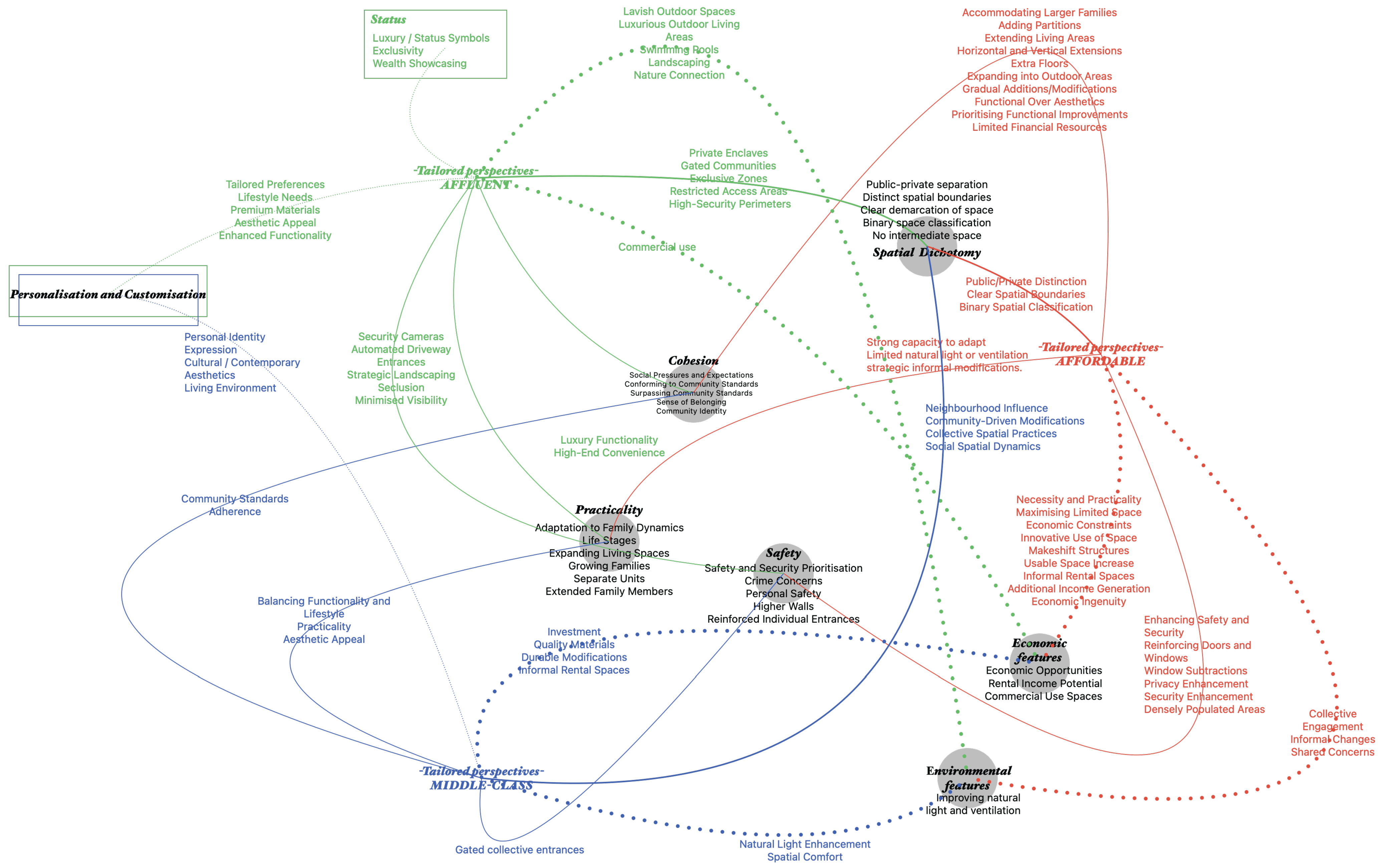

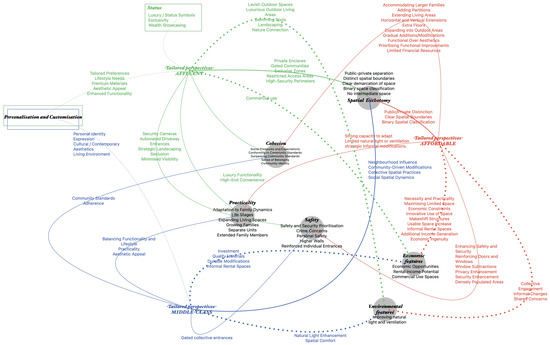

To preserve internal consistency, early coding frameworks were revised during the analysis. Older extracts were reviewed again to assess how they aligned with the newer themes. Analytical memos were used to document thought patterns and coding decisions. An early version of the conceptual map is provided in Figure 4. It captures how spatial practices are shaped by diverse social conditions.

Figure 4.

Preliminary visual synthesis of the exploration of coded themes across datasets. Color-coded paths represent informal housing logics: red for affordable, blue for middle-class, and green for affluent neighborhoods.

3. Results

To ensure clarity and replicability in the analysis, data were collected from a broad spectrum of residential environments in Rabat. The study focused on three income-based housing categories: affordable, middle-class, and affluent. Six neighborhoods—Hassan, Salé, Temara, Agdal, Harhoura, and Souissi—were selected because they reflect this socioeconomic diversity. Apartments, maisonettes, and villas were included in the study to ensure a wide representation of housing forms. This strategy supported a classification system based on neighborhood and socio-economic level, allowing for meaningful comparisons of informal changes. The results presented here highlight the complex structure behind informal housing practices in Rabat. This study is based on a wide range of empirical materials, including data from focus groups with both residents and architects, formal interviews, and field-level observations. The analysis is framed by four guiding themes: socio-cultural motivations [72,73], strategic adaptations [74], informal daily practices [75,76], and long-term effects on health and social life [77]. These categories allow a full understanding of the informal process, from initial triggers to final impacts.

3.1. Reactive Informality–The Needs

Many informal housing practices are driven by immediate social and cultural needs. These include the need to adapt to changing family sizes, to follow cultural traditions, or to feel safe in one’s home [78,79,80,81,82]. These actions usually fall outside official rules and are carried out without long-term planning. In Cameroon, Fombe described similar responses as a way for urban residents to cope with pressure [52]. Informal changes in such cases serve a purpose. They help households preserve cohesion, maintain identity, and respond to threats. This section looks at how reactive informality responds to family, spatial, and security needs.

3.1.1. Family Needs

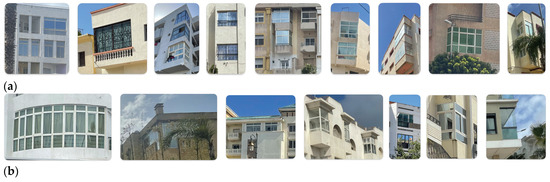

Across different income settings, informal home changes were closely linked to growing or shifting family units. Adapting the living space was often considered essential to everyday life. Formal restrictions were regularly overlooked in favor of supporting familial care structures. Among low-income families, building an extra floor was a widespread solution. Tipple et al. documented comparable trends in housing delivered by the state, where the strong cultural emphasis on family care and closeness shapes how space is informally transformed [31]. Enclosing courtyards and constructing additional floors are typical strategies for accommodating aging parents. As shown in Figure 5a, vertical expansion is often complete, adding a whole upper level. Figure 6a displays a balcony infill, turning outdoor areas into functional interior rooms.

Figure 5.

Informality in private spaces. Vertical extensions in affordable (a), middle-class (b), and affluent (c) housing neighborhoods.

Figure 6.

Informality in private spaces. Infill examples in affordable (a) and middle-class (b) housing neighborhoods.

Vertical extensions, including adding whole or partial floors, are a defining feature of middle-class housing informalities to accommodate dynamic family structures. Balcony conversions often accompany these, as residents prefer “a more spacious interior that feels practical and inviting.” Figure 5b presents examples of vertical extensions commonly found in middle-class neighborhoods, whereas Figure 6b illustrates balcony-to-window conversions that reflect infill strategies aimed at improving interior functionality. In affluent areas, housing informality is also marked by vertical growth, often incorporating specialized rooms and additional floors that support familial intimacy and hosting. Residents would build guest suites or recreational spaces, embodying cultural values tied to hospitality and status. These practices are visually captured in Figure 5c.

Housing informality occurs across different income groups and often relates to changes in how families are structured and how responsibilities are shared. Even when legal rules restrict what can be built or altered, residents still adapt their spaces based on cultural values. These values often highlight the importance of care for family members, long-term continuity between generations, and the need for home spaces to adjust over time.

3.1.2. Spatial Dichotomy Needs

Across all income levels, people consistently worked to preserve clear divisions between private, semi-private, and public space. These efforts stemmed from shared social norms and cultural values that reinforced the idea of responsibility for one’s surroundings—“I do have some kind of ownership towards what I take care of.” In lower-income areas, this often took the form of modest but inventive boundary-making: fences, hedges, or low walls marked out personal space from communal zones (Figure 7a). Residents frequently employed cost-effective and resourceful strategies for clear spatial demarcation in affordable housing neighborhoods. Informal modifications often included intermediate materials such as modest fencing, low walls, and hedges, effectively separating private areas from communal spaces (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Informality in communal spaces. Seclusive attachments via intermediate materials in affordable (a) and middle-class (b) housing neighborhoods.

Residents extended their sense of responsibility beyond private property by caring for shared frontages. They swept pavements, planted greenery, and maintained entrances. This reflects the concept of fina—a traditional spatial threshold in Islamic–Arab urbanism [83], where household pride is expressed through stewardship of adjacent space [56]. As seen in Figure 8, residents built infills to mark limits more clearly. Figure 9 shows how potted plants were also used to add privacy and esthetic value.

Figure 8.

Informality in communal spaces. Infill examples, specifically seclusive infills via permanent materials in affordable neighborhoods.

Figure 9.

Informality in communal spaces. Attachment examples, specifically seclusive landscaping aestheticism via potted vegetation examples in affordable neighborhoods.

In middle-class neighborhoods, informal modifications frequently relied on durable, visually consistent materials to define spatial boundaries in ways that aligned with neighborhood esthetics and sustained communal harmony. Figure 10b emphasizes how permanent garden features and landscaping helped define space and brought visual consistency. In upscale districts, spatial unity was achieved through discreet but high-quality adjustments. These included garden hedges, patterned walls, and elegant gates, all of which were chosen to align with the home’s design and to reflect social distinction. Figure 10c offers further visual evidence of this pattern.

Figure 10.

Informality in communal spaces. Seclusive landscaping aestheticism via permanent vegetation in affordable (a), middle-class (b), and affluent (c) housing neighborhoods.

In the Moroccan context, the front of the house, or bab ddar, holds more than architectural value. It operates as a cultural interface between private life and the shared street. Informal interventions in this area are common. These may include placing metal gates, building screens, or creating shaded corners. Such adjustments are practical, but they are also symbolic. They show respect for modesty, a wish for privacy, and the importance of hospitality. This aligns with the notion of fina, a traditional space of care and presence at the edge of the home. The bab ddar thus becomes a powerful site of quiet social negotiation. Across many social backgrounds, people carry out similar small changes that reflect mutual understanding and cultural rhythm. When formal planning does not respond to daily needs, residents adapt their surroundings. These changes, though minor, carry deep meaning rooted in social life. Selim Hakim, in his study of fina [56], reminds us that these acts are not only spatial. They are tied to everyday social relations.

3.1.3. Security Needs

In affluent and affordable neighborhoods, informal housing changes were frequently motivated by the desire for enhanced security. These acts of spatial adjustment reaffirmed the residents’ sovereignty over their living quarters and introduced imperceptible yet potent territorial cues that structured social use of adjacent communal areas.

- Architectural Scale Security Needs

In affordable areas, architectural responses to insecurity prioritized cost-effective reinforcement. Residents frequently secured vulnerable entry points like windows, doors, and balconies by adding metal bars, grilles, and boundary enclosures. Figure 11a captures how iron-based attachments were used in lower-income areas to manage entry points. By contrast, middle-class housing emphasized security features that blended function with form—decorative ironwork, esthetically matched gates, and reinforced doors equipped with layered locking systems. Some of these refinements are illustrated in Figure 11b.

Figure 11.

Informality in private and communal spaces. Access and control through openings and iron reinforcements in affordable (a) and middle-class (b) housing neighborhoods.

- b.

- Neighborhood Scale Security Needs

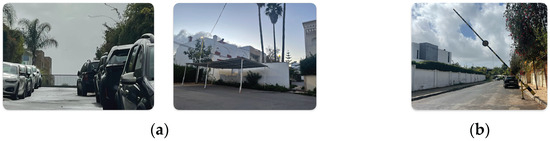

Security-oriented informalities often transcended the private domain, extending to shared neighborhood spaces. In middle-class areas, residents implemented entrance infills and semi-permanent structures—walls, gates, and enclosures—that collectively reinforced the perception of exclusivity and safety. Figure 12a exemplifies how such interventions complicate the public–private divide via architectural and representational devices. Similar visual strategies were employed in affluent neighborhoods, though often more spatially refined. Figure 12b shows how open barriers, such as ornamental gates or structured landscaping, communicated exclusivity without entirely restricting access. These interventions operated on a symbolic level, shaping public perception and reinforcing neighborhood prestige through visual cues rather than physical barriers.

Figure 12.

Informality in private and communal spaces. Drivable entrance infills and attachments in middle-class (a) and affluent (b) housing neighborhoods.

3.2. Proactive Informality–The Drivers

The second analytical focus explores informality as a proactive and aspirational practice. It is divided into three parts that examine esthetic goals, market strategies, and functional needs as core motivations. Unlike reactive adaptations, these actions are planned and future-oriented. They aim to enhance visual appeal, raise property value, or improve daily living conditions. Residents in Rabat described these changes as thoughtful investments rather than illegal actions. Such modifications express ambition, social aspirations, or practical improvement [84,85,86]. The following sections present three main drivers: esthetic transformation, economic positioning, and functional adjustment.

3.2.1. Aestheticism

Across income groups, esthetic ambition drives informal housing modifications, though the means and forms vary. Architects frequently provide “design-only” services, ranging from façade renovations to courtyard design and rooftop structures, enabling residents to sidestep the regulatory system. Such informal acts in middle- and upper-income neighborhoods often express cultural identity and personal taste. Residents selectively adopt global architectural motifs—minimalism, openness, and greenery—to achieve individual distinction and visual integration within their communities. One participant captured this balance by stating, “We wanted something modern but in harmony with the rest of the street.”

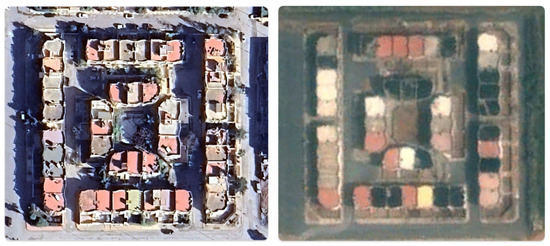

Figure 13 illustrates two examples of pool installations in Harhoura: one in a middle-income context and the other in an affluent neighborhood. A shared ambition for esthetic improvement guides construction in each context, though it unfolds differently. In areas with limited means, this vision is carried out through informal labor and affordable finishes such as plaster painted by hand or ceramic tiles arranged in decorative patterns. One architect remarked that clients in these contexts aim to project pride and aspiration through affordable design. This affirms Dovey’s position that informality is an experimentation and expressive agency field [34].

Figure 13.

Informality in private spaces. Pool additions in Harhoura–Rabat: (a) middle-class neighborhood (2018–2023) and (b) affluent neighborhood (2005–2024). Satellite images extracted from Google Earth. Images © Google Earth 2025.

3.2.2. Informality as an Economic Strategy

In Rabat, where real estate dynamics are rapidly shifting, informal spatial interventions are often made with market logic in mind. Across neighborhoods, homeowners use informal upgrades like adding rooms, enclosing balconies, or installing ornate gates to enhance resale prospects. In affluent districts, modifications are aimed at luxury appeal, including features like pools or rooftop lounges. One resident observed that turning their rooftop into a stylish terrace sharply elevated the asking price. In middle-class areas, the same economic intent is reflected in less costly modifications such as ornamental gates, façade enhancements, or informal additions that expand living space. According to one interviewee, enclosing their balcony created a more appealing layout for potential buyers. In lower-income contexts, residents often extend homes to create rentable sections, turning informality into an entrepreneurial tactic. Such practical strategies reflect a widespread understanding of informality as a means to increase long-term value.

3.2.3. The Pragmatism of Urban Informality

Although frequently discussed in terms of their economic constraints or cultural signification, informal housing adjustments represent pragmatic acts through which residents address design limitations in formal typologies. These interventions are rooted in deliberately recalibrating domestic space to enhance functionality and environmental comfort. Recurring forms of intervention include projecting rooms outward to generate additional space, installing staircases leading to rooftop areas, and converting open driveways into private, enclosed dwelling extensions. These actions reflect pragmatic solutions to space constraints rather than decorative ambitions. Architectural interventions are frequent, such as rearranging internal layouts for better ventilation, lighting, or circulation. As shown in Figure 14, a vertical extension was added in a middle-class neighborhood. Its main purpose is to allow easier access to the rooftop.

Figure 14.

Informality in private spaces. Roof access and floor additions in a middle-class neighborhood in Harhoura–Rabat (2005–2025). Satellite images extracted from Google Earth. Images © Google Earth 2025.

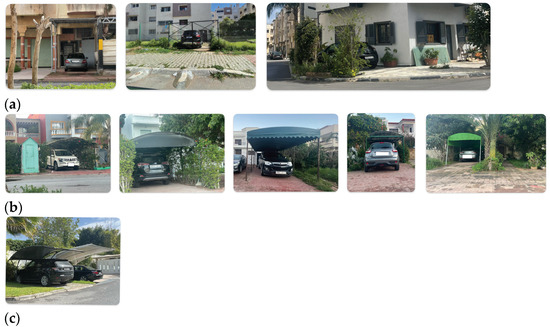

Figure 15 illustrates spatial interventions related to parking across neighborhoods of varying income levels. Due to pressing spatial constraints, such additions are especially prominent in affordable areas, but they also appear in wealthier districts, where vehicular access and security concerns become more pronounced.

Figure 15.

Informality in communal spaces. Parking arrangements in affordable (a), middle-class (b), and affluent (c) housing neighborhoods.

In sum, the drivers of housing informality in Rabat reveal the strategic and aspirational dimensions of informal practices. Aestheticism allows residents to assert identity and status, market-driven motives encourage spatial innovation that increases property value, and practical drivers respond to the everyday realities of living in under-adapted formal structures. While these drivers coexist with basic needs, they stand apart as acts of calculated transformation. This insight frames the upcoming section, illustrating how lay actors and professionals give spatial form to these intentions. In Rabat, informality unfolds not as disorder, but as a set of adaptive maneuvers, temporary fixes adapted to context, linguistic reframing of functions to satisfy rules, and phased construction aligned with changing personal and economic trajectories. These spatial tactics illustrate the intentional and negotiated engagement with formal housing systems, expanding our grasp of how informality serves as a method of spatial agency. The analytical lens adopted here parallels the work of Simões et al., who outlined comparable patterns in Brazilian social housing [87]. This section transitions from conceptual framing to the tangible realm of spatial alteration, examining the inventive ways in which formal regulatory structures are circumvented, reinterpreted, or strategically adjusted through informal modifications.

3.3. Methods of Informality–The Tools

The focus now turns from motivations to the ways informal changes are made. We look at how people put these ideas into action in real spaces. Our analysis reveals three recurring tactics: adjusting to what the context allows, giving new meanings to existing structures, and acting step by step. These strategies are visible across different cases. They point to informality as a set of practical tools, not just rule-breaking. People plan carefully within constraints. Their decisions are shaped by tradition, need, and ongoing dialog with the built environment.

3.3.1. Timely Contextual Adaptations

While architects reiterated their dedication to upholding formal regulatory frameworks during the initial planning process, they also acknowledged that homeowners often diverge from approved designs once the building phase begins. As one architect explained, the official role of planners often ends once the design is approved. However, those approvals rarely reflect how people actually live, showing a clear disconnect between regulations and real spatial use. Figure 16 provides a compelling example of a timely contextual adaptation in affordable housing: windows have been temporarily opened into a shared boundary wall. While these homes were not inhabited by participants interviewed in the focus groups, the observed practice is representative of patterns described across the discussions. Openings are typically kept intact until neighboring parcels are built up, after which they are sealed. This pattern showcases how residents use informal solutions to address current ventilation or spatial needs without compromising future flexibility. It demonstrates a calculated, phased approach to change.

Figure 16.

Informality in private spaces. Timely contextual adaptations through expansibility in an affordable housing neighborhood.

During the focus groups, architects expressed an understanding of the challenges faced by residents. However, they acknowledged that their own role is mostly limited to enforcing rules. Because there is no system in place to monitor changes after initial approval, architects are often left without the ability to respond. This situation highlights a clear gap between unchanging regulations and the evolving nature of city life.

3.3.2. Adaptive Labeling

Evidence from architect focus groups and feedback questionnaires illustrates that modifying terminology is a pragmatic strategy within the broader context of regulatory negotiation. Despite formal planning codes forbidding the recognition of subterranean rooms as residential quarters, approval is frequently granted under the label “storage.” In actual usage, however, these spaces are regularly transformed into living areas to satisfy socio-cultural imperatives or address pressing household requirements like ensuring privacy or lodging extended family members. Utilizing the semantics of official planning discourse, this tactic enables residents to perform informal spatial adaptations under the cover of technical legality. Architects regard this as a strategic compromise, facilitating adherence to professional mandates while meeting clients’ practical expectations. The prevalence of such cases illustrates a co-produced spatial agency, wherein the roles of expert and inhabitant converge in response to the divergence between regulatory prescriptions and real-world use.

In many cases, codes cannot accommodate cultural frameworks or family structures, leading to informal reinterpretations, which Selim Hakim identifies as culturally embedded regulatory flexibility in Islamic–Arab urbanism [56]. Adaptive labeling is more than a means of technical compliance; it serves as a mechanism through which rigid regulations are informally bypassed, enabling formal and informal practices to coexist. Allowing greater degrees of autonomy, this negotiated spatial context challenges conventional urban governance’s supposed rationality and ethical standing. According to Benjamin, negotiated informality involves repurposing formal structures to suit the lived exigencies of residents [22]. When deployed within this gray zone, adaptive labeling brings to light the pronounced limitations of Rabat’s current urban policies in reconciling regulatory intentions with on-the-ground diversity.

3.3.3. Phased and Additive Temporality

Phased temporality, a widespread practice within informal housing strategies, allows dwellers to align with initial regulatory expectations while progressively adapting their structures to accommodate shifting economic, familial, and cultural realities. In doing so, it challenges the rigidity of normative planning protocols and highlights the dynamic character of lived spatial adaptation in Rabat. Focus group participants stressed that phased construction holds cultural significance and practical value, especially in non-affluent housing sectors. In low-income settings, residents frequently rely on phased construction to manage limited budgets. Starting with core structures, they later add rooms or convert existing spaces into rental units. One participant shared that, through years of gradual work, they transformed a modest storage space into a rentable room, boosting revenue and the property’s value. Residents’ stepwise adaptations illustrate how phased temporality balances financial limitation with cultural foresight. Many emphasized building spaces with future generations in mind, reinforcing that homes are temporal constructs rather than static entities. Citing Morton [57], clandestine masonry emerges as a deliberate and temporally nuanced form of urban expression. In keeping with that framework, this study uncovers how residents and built environment professionals engage in spatial experimentation that is both compliant in appearance and transformative in function. Such subdued reworkings of regulatory structures ought to be considered fundamental to resilient urban development’s architecture. Having laid bare the rationale and trajectories underpinning the emergence of informality, the discussion now advances toward unpacking its consequences in economic, social, and morphological terms.

3.4. Impacts of Informality–The Outcomes

This section explores the consequences of informal housing on people’s lives. These consequences appear in three main forms: economic, social, and health-related. While they are analyzed individually, they often overlap in real-life situations. Having looked at how and why informality happens, the discussion now turns to what it does. Informality is not simply a problem. Its effects vary with context and can often bring positive results. Many of these results reflect the same drivers seen earlier, such as economic logic and the flexible use of space. The findings are based on what participants said and what was observed in the field. They show how informal practices can help families adapt, but also where they may create strain. A full understanding of housing informality must include these varied outcomes across different social groups.

3.4.1. Increased Affordability and the Informal Economy

Informal housing practices allow households to improve their homes at a lower upfront cost because they provide a level of flexibility that formal financing does not offer [88,89,90]. Since many residents cannot access standard bank loans, they often rely on savings, family remittances, or small informal loans to gradually fund home improvements. Home improvements are often executed in stages, a rhythm that aligns more seamlessly with sporadic income flows and lessens dependence on expensive credit. These alterations are typically executed within a non-formal building economy that is financially accessible, operating without state regulation, and rooted in local social networks. Such unregulated alterations, when accrued over time, substantially contribute to the future asset value of the residence. Residents often conceptualize these interventions not as regulatory breaches but as sound economic choices intended to generate income from tenants, raise market appeal, or enable connection to improved infrastructure networks. Through a comparative study of housing practices in Ghana and Zimbabwe, Tipple et al. observed that informal arrangements may serve as mechanisms for achieving financial incorporation [31]. These affordability benefits often result from methods of informality such as incremental building and informal contracting (Section 3.3), which enable cost efficiency, and are directly motivated by the economic aspirations explored in Section 3.2.

3.4.2. The Paradox of Social Cohesion and Fragmentation

The social effects of informal housing practices are not always straightforward. While some residents use these changes to create shared responsibility for communal areas [91], others install fences or hedges that set boundaries and reduce openness [92,93]. These physical limits alter the way people interact with space, as shown in Section 3.3. The changes often stem from cultural needs for privacy and informal regulation, as mentioned in Section 3.1. In Lisbon, ref. [58] found that such practices could unite communities but sometimes also strain them.

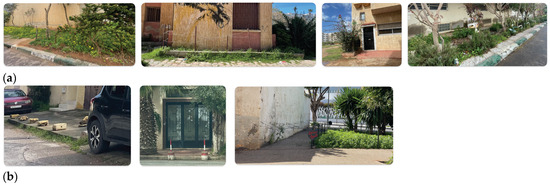

Figure 17 demonstrates that horizontal extensions and attachments in affordable neighborhoods can transform shared courtyards into contested boundaries. Figure 18a,b show how greenery and transient materials assert territorial claims, reinforcing perceived ownership at the expense of shared use.

Figure 17.

Informality in communal spaces. Attachment and horizontal extension examples that create fragmentation in affordable neighborhoods.

Figure 18.

Informality in communal spaces. Greenery and iron examples in affordable (a) and transient material examples in middle-class (b) housing neighborhoods.

3.4.3. Perils of Unregulated Extensions

Many informal housing upgrades circumvent critical safety checks, heightening structural and fire hazards [94,95]. Unpermitted additions can jeopardize structural integrity by introducing loads that exceed the design capacity of beams and walls. Bedrooms and laundry rooms installed over narrow support members may result in cracking or bending. These risks are aggravated when materials are layered without anchorage, leading to misaligned load distribution and weakened building frames. Moreover, the hazards are compounded by improvised electrical wiring, unventilated cooking spaces, and blocked exits. As these dangers are present from the first day of construction, each informal modification creates a physical environment that escalates structural and fire risks. These risks echo those documented by Carrasco et al. in post-resettlement areas in the Philippines, where informality functioned as both a coping mechanism and a destabilizing force [60]. This duality reinforces the need for governance models that balance adaptive flexibility with structural safety, recognizing informality as a persistent and negotiated component of urban life. Informality’s economic, social, and spatial impacts illustrate its ambivalent nature by revealing both empowering and destabilizing outcomes. It is a pragmatic response to systemic inadequacies yet contributes to the persistence of planning inequities and governance blind spots. Such complexity calls for policy approaches that recognize informality as a permanent feature of urban life, demanding a careful balance between enabling agency and ensuring public safety. This research contests the dominant portrayal of housing informality as unlawful or chaotic. Instead, it reveals the deliberate, adaptive, and culturally situated nature of informal residential modifications in Rabat. Rather than opposing regulatory frameworks, informal practices in Rabat actively engage with them.

Several of the hazards discussed are rooted in the informal methods already outlined, including staged building and changing the meaning of spaces over time. These methods also stem from larger aims such as increasing usable space and enhancing property value. While they bring real benefits, they often show where planning systems fail to meet resident needs. Housing informality in Rabat is not a random set of acts. It is built on a mix of social, cultural, and economic drivers. Some acts respond to pressure from growing households or the need for privacy. The transformations made by residents are often guided by the need for better living conditions or financial survival. These changes arise from practical realities and local constraints. Informality becomes a visible response to these pressures through the reworking of space. The next section looks at how these findings might influence planning approaches. In Morocco, the endurance of informal practices must be understood in relation to restrictive planning laws. Law 12–90 offers little flexibility for families whose spatial needs evolve over time. There is no space in the legal framework for flexible density, cultural norms, or user participation. In Rabat, planning regulations, inherited from centralized and colonial systems, fail to respond to family-based spatial demands. Informal changes are thus common. They do not arise from disregard for planning but from a need to adapt spaces to everyday life. These adaptations form an alternative form of governance that is rooted in cultural logic.

4. Discussion

Housing informality in Rabat does not indicate disorder. It shows how people adapt to rigid planning systems while pursuing local goals. Other cities reflect this pattern. In Bahrain, residents upgrade welfare estates [96]. In Bogotá, homes grow upward [97]. In Moroccan cities, relocation sites take new forms [9]. This section has two main parts. First, it looks at how residents repeat what others have carried out nearby. Over time, such alterations become accepted and are closely related to cultural concepts like bab ddar. Difficulties emerge when people do not have clear property titles or when boundaries are uncertain. Authorities tend to see these changes as violations. In contrast, residents view them as beneficial. A resident explained that the extension to his doorway made the house stand out and increased its market value. Focus groups showed that buyers are not concerned about permits. Photos showed solid construction, often matching the house’s design. The gap between formal design and informal work is small. Informal actions often improve the home and reflect shared values. Section 4.2 discusses how this view helps revise how informality is understood in urban studies.

4.1. Informality as Socio-Spatial Expression

Rabat’s housing informalities articulate embedded forms of agency shaped by historical and neighborhood-specific dynamics, much like the collective illegalities in Sofia and Caracas [98] or the flexible citizenship arrangements described by Sassen in ambiguous regulatory settings [99]. The informal morphologies of extension, infill, attachment, and addition express shared spatial logics—accessibility, elevational articulation, expandability, and privatization—paralleling the incremental patterns seen in Nairobi estates [19] and Ghana–Zimbabwean housing schemes [31].

4.1.1. Mirroring and Tacit Consensus: How Informality Spreads and Stabilizes

Mrani et al. discussed the idea of mirroring, a pattern where informal building changes made by some residents are repeated by others [39]. These changes often serve a purpose beyond appearance. They represent shared values or strategies within the community. These actions gradually form silent patterns that repeat across neighborhoods. In several neighborhoods of Rabat, one can notice that balconies are transformed in consistent ways, often repeating the same materials and shapes. These alterations are not the result of any coordinated plan. As shown in Figure 19, the repetition spreads through what residents see and silently accept, shaping a common architectural rhythm.

Figure 19.

Mirrored informal practices in private spaces. Infill examples of balconies incorporated into housing units across middle-class neighborhoods.

Visual imitation spreads easily in these neighborhoods because it is supported by quiet agreement within the community. This kind of social understanding allows informal actions to become part of everyday life, as long as they are seen as reasonable. In affordable housing areas, people often place planters, metal fences, or decorative barriers in shared spaces. These items gradually transform public land into areas that feel more private. When these changes are performed in a modest way, they are rarely questioned. As shown in Figure 20, flower pots are sometimes used to mark parking spaces, while ironwork or vegetation is arranged to set boundaries. These acts are small, but they reshape the meaning and use of communal space.

Figure 20.

Tacit community consensus in communal spaces of affordable neighborhoods. Privatization through vegetation (a), reserved parking with potted plants (b), and iron barriers (b–d).

Informal housing changes often resemble what Nkurunziza calls “silent contracts” [100], and they follow the idea of gradual recognition described by Durand-Lasserve and Selod [67]. Rather than needing permits, residents depend on community support. One participant stated, “If the neighbors are okay, why not?” This kind of informal negotiation, based on copying and quiet agreement, allows such practices to become normal and accepted over time.

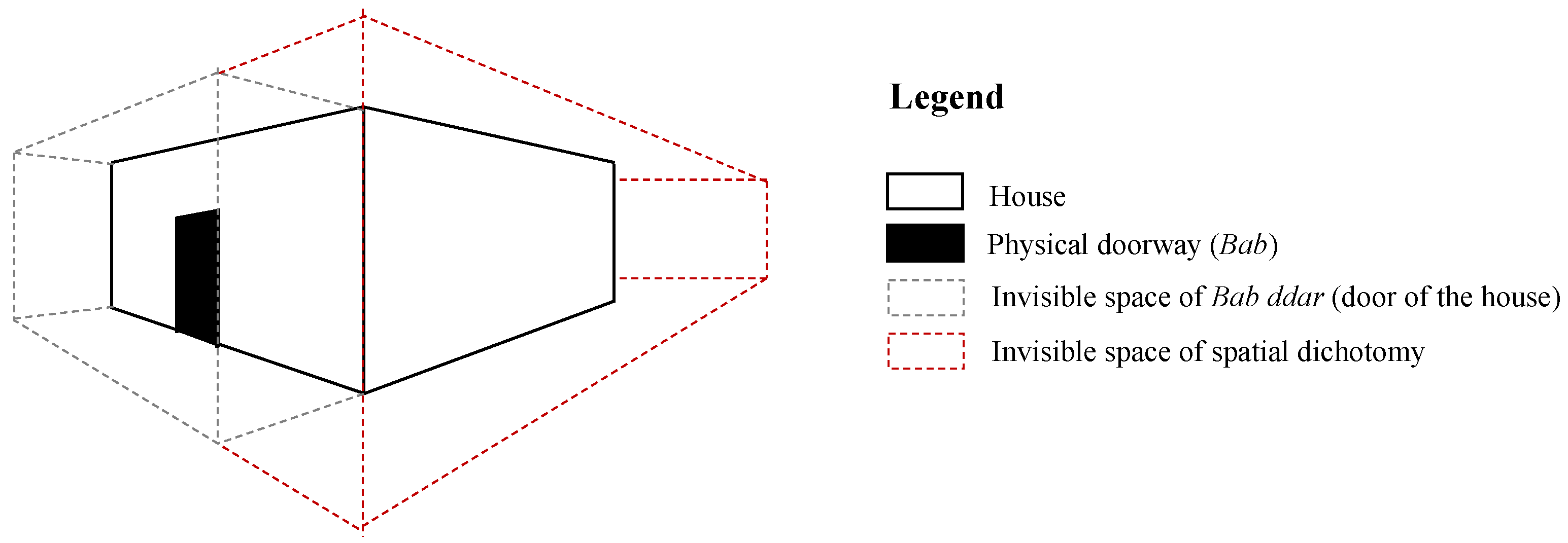

4.1.2. The Concept of “bab ddar” or Door of the House

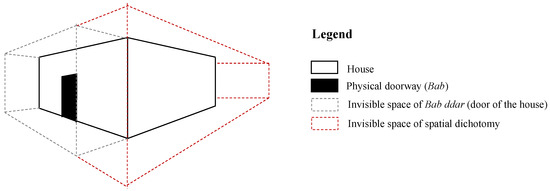

A concept rooted in vernacular spatial practice, bab ddar, translates literally to “door of the house.” In everyday Moroccan usage, this term encompasses more than the architectural threshold itself; it designates both the doorway (bab) and the adjacent strip of pavement that precedes it, a socially and spatially meaningful space despite being physically unmarked (see Figure 21). Everyday acts such as sweeping, tiling, planting, or furnishing the space at the entrance point to a more profound spatial absorption, wherein residents mentally and socially extend their domestic sphere to include the threshold, as Boumediene explains [101]. This spatial assimilation is consistent with the Maghrebi tradition of al-fina, a culturally embedded buffer zone flanking outer walls and tacitly permitting subtle spatial claims like placing planters, seating, or shade devices [102]. The proverb “علامة الدار على باب الدار” (“the sign of the house is on its door”) encapsulates the underlying value: attentiveness to this zone is equated with social dignity, whereas disregard suggests disorder.

Figure 21.

Conceptual schematic. The invisible space of the bab ddar, spatial dichotomy along exterior walls, and the physical doorway.

The diagram in Figure 21 helps clarify how residents think of the space just outside the home. This threshold, the bab ddar, plays both a practical and symbolic role. It is treated as part of the house, even when not legally recognized as such. This makes it an important example of informal use shaped by cultural values. People from different income levels use this area to manage social and spatial divisions. Focus group discussions and images show that the practice spreads across the full edge of the dwelling. In many cases, residents use everyday objects such as screens, potted plants, or containers to define boundaries where formal planning has remained silent.

Figure 22 offers a tangible view of the concept of bab ddar, showing how households from different income levels adapt and mark these threshold spaces. Whether through simple ceramic pots or intricate metalwork, the images document a growing set of informal practices that shape the boundaries between public and private space. Although sidewalks belong to the public domain, residents near them often clean, decorate, or upgrade them. These everyday gestures reflect housing informality at a small scale. They also reveal how residents negotiate spatial boundaries while reinforcing shared values.

Figure 22.

Bab ddar examples across Rabat’s socioeconomic spectrum, showing partial and complete spatial dichotomy.

4.1.3. Informality, Insecurity, and Boundary Disputes

Even when informal housing changes appear minor, they can provoke tensions, especially when they affect shared areas or neighboring comfort. This issue has also emerged in Brazil, where formal neighborhoods face similar conflicts over boundaries [36]. In Rabat, some affluent districts have installed gates across public roads, a pattern that echoes gated communities in São Paulo [55] and Cairo [103]. These disputes rarely escalate to legal courts. Instead, they are resolved through informal negotiations and community relationships. Such tendencies are visible in Algeria [13] and Chile [104]. Deboulet observed that the state often ignores these tensions [42]. While the changes may seem functional, they raise serious legal concerns, especially when they breach planning codes. This leads to uncertainty about property legitimacy. Our findings show that these actions, while common, can result in penalties, sale complications, or demolition orders. Similar outcomes have been reported in Bogotá, Manama, and Istanbul [30,96,97]). Despite this, most residents did not view their actions as illegal. They described them as practical, even necessary. Buyers also tended to accept such changes without questioning permits. This suggests that informal housing practices are broadly normalized. Yet, the tension between household needs and rigid legal frameworks remains. Similar dynamics appear in Kampala [100] and Buenos Aires [50], where small upgrades can lead to legal friction. These changes often rest more on social consensus than formal legality.

4.2. Addressing Gaps and Critical Reflections

Across many cities, including Rabat, people are adapting formal housing to better meet their needs. In Bangkok’s Khlong Toei, the Baan Mankong project supports this idea by showing that when communities lead, housing conditions can improve [105]. In Spain, local activism has shaped how housing is managed during economic crises [106]. These cases confirm the relevance of resident action and inclusive policies. Rabat offers a new lens, where a city-wide study explores how informal housing changes arise from a mix of social needs, market pressures, and legal limitations.

4.2.1. Cross-Class Ethnography of Housing Informalities

To view informality purely through the lens of poverty is to miss its broader function. In Rabat’s well-off neighborhoods, it takes on a language of subtle transformation—minor yet calculated shifts to façades and thresholds. Such practices resonate with Makachia’s accounts of status-making in Nairobi [19] and Simões and Leder’s work on spatial refinement in Brazilian housing [36]. Informality here is the rule, not the exception.

4.2.2. Mechanisms of Informal Diffusion and Social Legitimacy

Urban informality is no longer ignored, but the micro-social engines that drive its spread are poorly understood. Findings indicate that informal spatial transformations endure when they follow established visual codes, are replicated through emulation, and unfold through slow, layered iteration. Comparable dynamics were observed by [54] in the context of American ADUs and by Chiu in rooftop reconfigurations in Taipei [107].

4.2.3. Alternative Interpretations and Study Limitations

The study suggests that informal housing practices in Rabat are shaped by cultural logic and everyday strategies. Yet, another point of view might argue that these patterns show weakness in the formal planning system. If rules are not enforced or if bureaucracy is slow, residents may feel free to change spaces without official approval. Informality, in this sense, signals deeper systemic concerns within urban policy. Though the study delivers rich and context-specific findings, its limited scope reduces the potential for broader generalization. The diversity of neighborhoods studied helps capture class differences, but not the full complexity of Moroccan urban life. Interviews and visual analysis enrich the discussion, but they are not substitutes for statistical tools. Broader patterns might emerge through studies that include numerical data, follow trends over time, or examine multiple cities. Furthermore, this research embraces the limitations of its method and encourages continued exploration into the layered reality of housing informality. Through a comparative and process-oriented lens, it captures the lived and spatial experiences of informal adaptation. It does not apply spatial regression analysis or other forms of statistical modeling. This was a deliberate choice to focus on the meaning and rationale behind everyday decisions. This approach could be expanded by including spatial models that show where informal changes cluster or intensify. Doing so would give researchers a more complete tool for understanding urban informality. This paper sees informal housing not as disobedience, but as a form of life adjustment. In Rabat’s formal areas, residents use informal practices to respond to real needs. The notion of bab ddar and the way people mirror one another’s changes show that informality often creates structure. These acts are common across different income groups and reveal a shared form of home upgrading. This challenges the view that informality is only tied to marginality. Instead, it is a routine part of how people shape space in constrained systems. Urban planners should not ignore these logics. Instead, they should build policies that reflect and support the everyday reasoning behind informal acts. Doing so may lead to more inclusive and effective planning outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The study interprets housing informality in Rabat as a quiet and meaningful form of spatial adaptation. It is not a sign of chaos or illegality but a way residents adjust their homes to match their needs and values. In different parts of the city, informal acts such as extending a porch or modifying a balcony are common. These changes are often subtle but significant. They express aspirations, solve problems, and respond to regulatory gaps. This process resembles housing practices in Nairobi, Brazil, and Istanbul, where similar informal changes serve social and economic goals.

5.1. Embedding Informality in Moroccan Urban Context

Scholarship makes it clear why informal spatial habits endure. Escallier and Pinson showed how households reshaped colonial patterns through daily acts [25,68]. Navez-Bouchanine sees informality as a local agreement about how space should be used [26]. Our research aligns with these broader observations. People reshape their environments through small-scale expansions, careful imitation of façades, and collective responsibility for shared areas. These practices remain common even when formal rules and job pressures are intense. The bab ddar remains a key reference point in these changes. It mixes the home and street, while also expressing ideas about social status and respect. Yet planning documents in Morocco often fail to address these spaces. Cultural practices like the fina are left out of planning frameworks.

5.2. Policy Recommendations for Moroccan Urban Planning

Two main recommendations arise for urban planners and policymakers. The first is the need for governance models that support rather than suppress informality. This includes creating regulatory allowances in the form of “adaptation margins” around legal housing plots, which would make it possible to carry out small additions like vestibules, fences, or eaves legally. Granting official recognition to practices like bab ddar would enable residents to retain these habits without needing to undergo lengthy approval processes. A second key step is ensuring that planning decisions reflect cultural values. Respecting traditions such as threshold decoration or informal neighborhood arrangements strengthens public confidence and encourages adherence to planning norms.

5.3. Theoretical Contributions to Informality Studies

This study challenges traditional views on housing informality by developing the idea of quiet architecture as a way to understand how people reshape their living space through culturally accepted and visually clear actions. Residents often act through silent consensus, repetition of local models, and the use of threshold zones like bab ddar. Such actions give informal modifications a sense of legitimacy. They operate more as forms of adjustment than as acts of defiance. This perspective enriches the broader conversation on informality by illustrating how informal practices can align with formal frameworks to promote adaptable spatial outcomes.

5.4. Directions for Future Research

Future research can expand this work by applying quantitative spatial tools, including spatial regression analysis, to examine how informal modifications cluster and spread across different urban areas. Comparative studies involving Moroccan cities and other places in the MENA region could test whether concepts such as bab ddar and tacit consensus apply more broadly, offering deeper insight into how informality relates to culture, governance, and everyday spatial routines.

5.5. Balancing Strengths and Challenges of Informality

This study recognizes that informal modifications demonstrate strong adaptability, deep cultural grounding, and sensitivity to market needs. However, it also draws attention to their limitations. These informal spatial practices can reinforce existing social and spatial divides, create challenges for public infrastructure delivery, and sustain legal uncertainties. Such uncertainties may weaken long-term planning efforts and reduce access to formal services. Although informality steps in where rigid planning fails, it may also contribute to persistent urban inequalities.

Author Contributions