How Does the Built Environment Shape Place Attachment in Chinese Rural Communities?

Abstract

1. Introduction

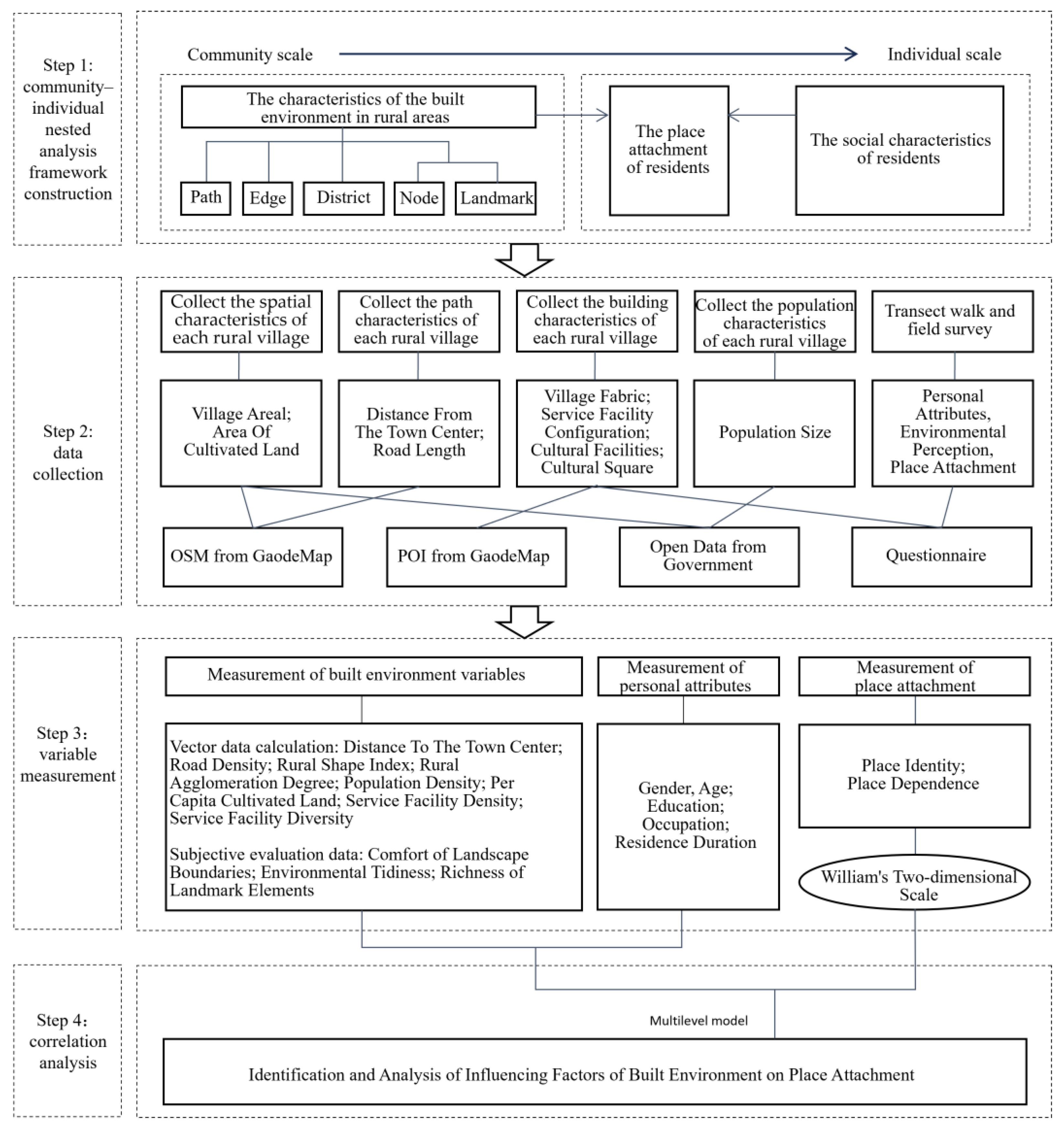

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Framework on the Influence of the Built Environment on Place Attachment

2.2. Variable Description

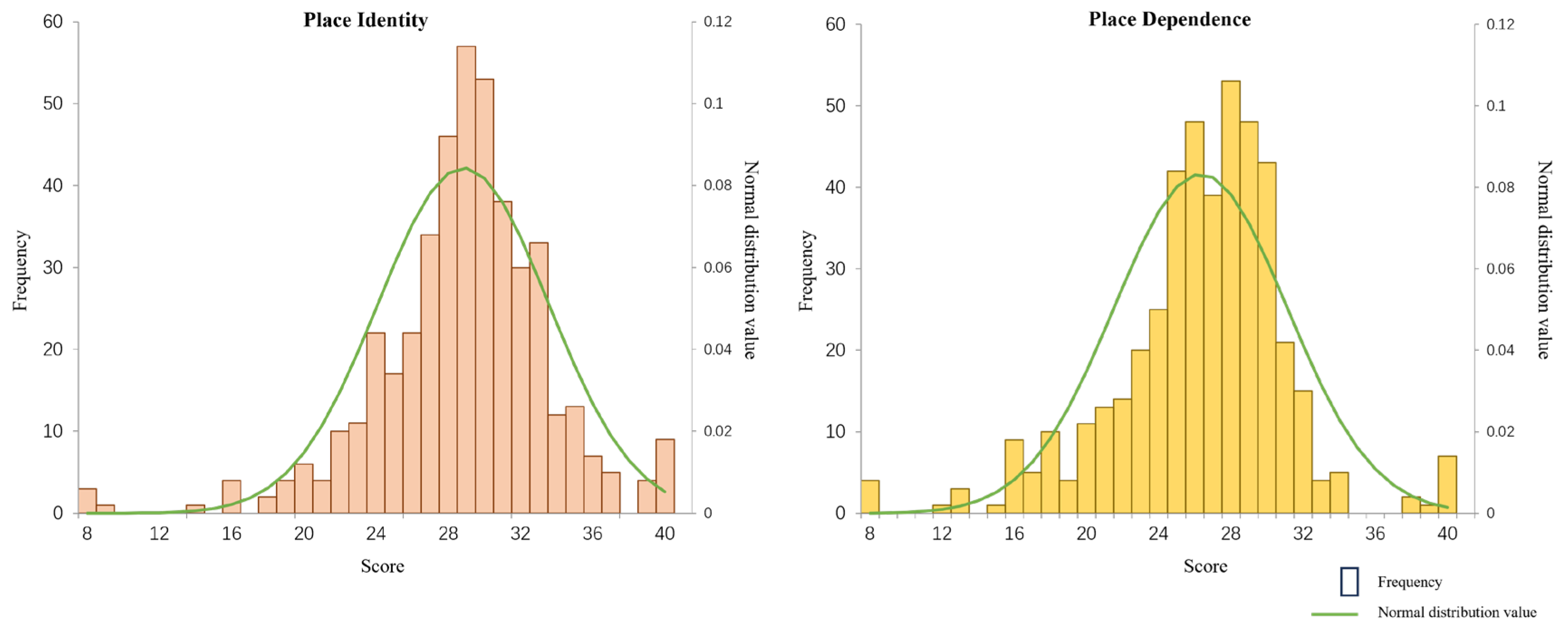

2.2.1. Methods for Measuring Place Attachment

2.2.2. Explanation of Variables Affecting Place Attachment

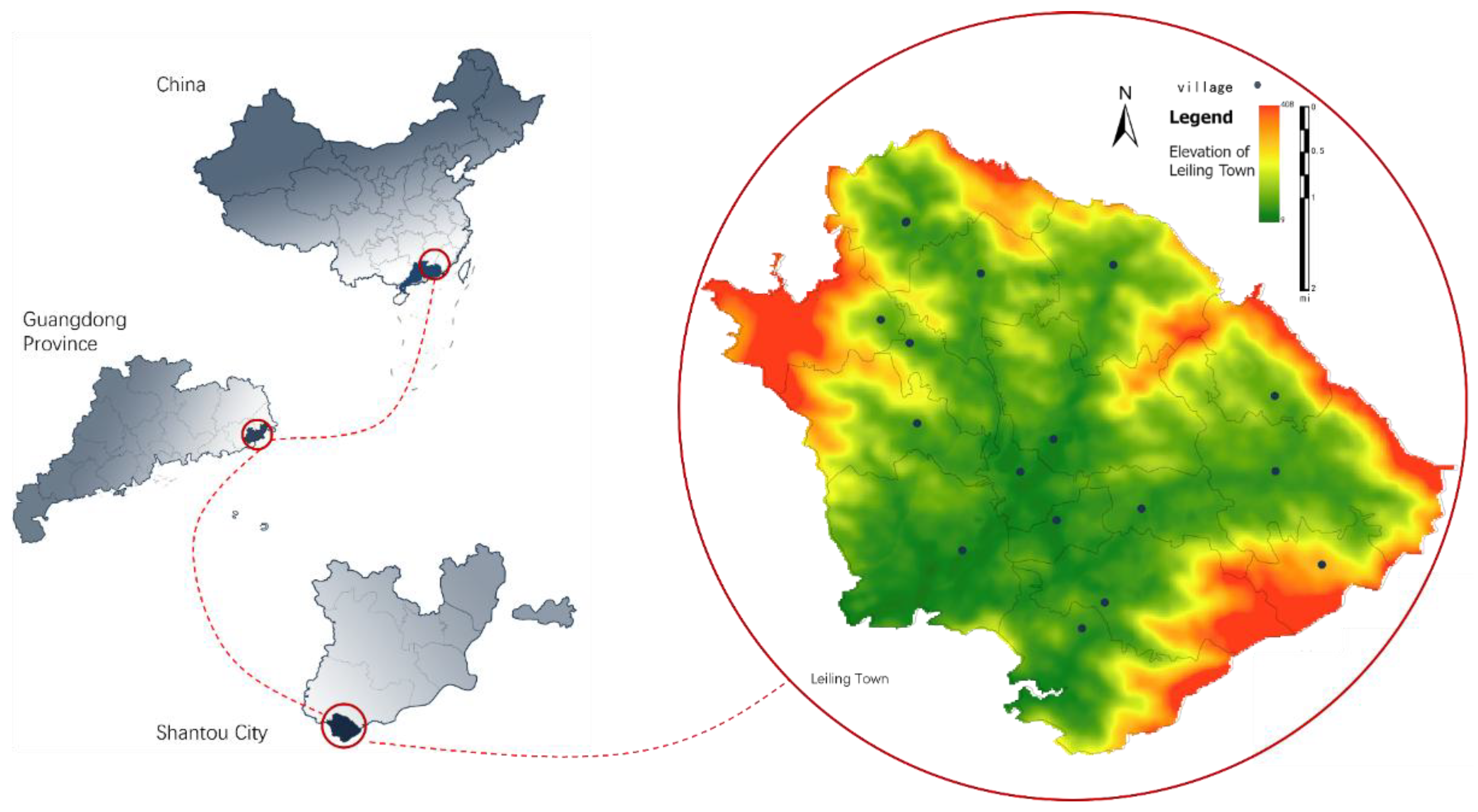

2.3. Case Area and Data Foundation

2.3.1. Overview of the Case Area

2.3.2. Data Sources

2.4. Research Methods

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Overall Characteristics of Rural Residents’ Place Attachment

3.2. Overall Characteristics of the Built Environment in Leiling Town

3.3. Results of Multi-Level Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Research Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The mean value of place attachment of rural residents in Leiling Town is 0.612; gender, age, and length of residence are the main individual variables affecting the place attachment of rural residents.

- (2)

- 14.56% of the variation in rural residents’ place attachment can be attributed to the built environment. Our findings indicate that the distance from the urban center, rural concentration, rural cleanliness, and iconic cultural buildings are the main built environment variables influencing place attachment, which is basically consistent with the results of related studies. The analysis reveals that enhancing the compactness of village building layout, environmental cleanliness, and construction of traditional cultural venues can boost rural residents’ place attachment.

- (3)

- Nodes and landmark elements have a greater impact on the place attachment of rural residents than roads, boundaries, and regional elements. Optimizing the design and experience of nodes and landmark elements is the main way to improve the place attachment of rural residents in the study area.

- (4)

- The formation of rural residents’ place attachment depends on their continuous embodied practice in the countryside and the sharing of meaning in social interactions. The impact of the built environment on attachment follows the identity cycle of “memory identity—place identity—identity”.

5.2. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, S. Structuralism and humanism superposed analysis of local landscape reconstruction: The case study of traditional dangjia village in shanxi province. Geogr. Res. 2025, 44, 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place attachment: Human behavior and environment. Advances in theory and research. In Place Attachment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; de Bakker, M.; Strijker, D.; Wu, H. Effects of distance from home to campus on undergraduate place attachment and university experience in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashid, M.A. Perceived Socioenvironmental Determinants of Neighborhood Attachment: Empirical Evidence among Children in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 04024071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C.M.; Corcoran, J. Mapping and measuring place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 57, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Paper analysis of the relevance of place attachment to environment-related behavior: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félonneau, M. Love and loathing of the city: Urbanophilia and urbanophobia, topological identity and perceived incivilities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, A.A. Physical and Social Factors in Neighborhood Place Attachment: Implications for Design; North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Górny, A.; Toruńczyk-Ruiz, S. Neighbourhood attachment in ethnically diverse areas: The role of interethnic ties. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1000–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N.; Maulan, S.; Ismail, S. Understanding the process of parks’ attachment: Interrelation between place attachment, behavioural tendencies, and the use of public place. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 14, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Chen, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D. Cultural ecosystem services valuation and its multilevel drivers: A case study of Gaoqu Township in Shaanxi province, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 41, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, D.; Fulthorp, K.; Paris, C.M. Examining the relationship between place attachment and behavioral loyalty in an urban park setting. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 25, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion London: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Cui, D.; Cui, H.; Han, X. Research on the connotation, mechanism and implementation strategy of rural community construction from the perspective of place attachment. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2024, 2, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammitt, W.E.; Backlund, E.A.; Bixler, R.D. Place bonding for recreation places: Conceptual and empirical development. Leis. Stud. 2006, 25, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammitt, W.E.; Kyle, G.T.; Oh, C. Comparison of place bonding models in recreation resource management. J. Leis. Res. 2009, 41, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António, J.A.D.; Custódio, M.J.F.; Perna, F.P.A. “Are you happy here?”: The relationship between quality of life and place attachment. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 6, 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Yasunaga, A.; Oka, K.; Nakaya, T.; Nagai, Y.; McCormack, G.R. Place attachment and walking behaviour: Mediation by perceived neighbourhood walkability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring place attachment: Some preliminary results. In Proceedings of the Session on Outdoor Planning and Management, NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–22 October 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Koohsari, M.J.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Tanimoto, R.; Watanabe, R.; Nakaya, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yasunaga, A.; Oka, K.; et al. The built environment and place attachment: Insights from Japanese cities. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 50, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Tang, H.; Guan, M. The impact mechanism and construction strategy of attachment to public places in rural areas—Taking Qiu village in Yingde city as the example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, W.; Shu, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, R. The Multifaceted Impact of Public Spaces, Community Facilities, and Residents’ Needs on Community Participation Intentions: A Case Study of Tianjin, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; He, J.; Liu, M.; Morrision, A.M.; Wu, Y. Building rural public cultural spaces for enhanced well-being: Evidence from China. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 540–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnow, R. Place type or place function: What matters for place attachment? Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2024, 73, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. An Overview of Research on Rural Public Space and Place Attachment: Concepts, Logics, and Associations. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, Y. Residents’ place identity at heritage sites: Symbols, memories and space of the “Home of Diaolou”. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 2381–2394. [Google Scholar]

- Goudy, W.J. Further consideration of indicators of community attachment. Soc. Indic. Res. 1982, 11, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. What Makes Neighborhood Different from Home and City? Effects of Place Scale on Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, S.; Rollero, C. Different Levels of Place Identity: From the Concrete Territory to the Social Categories; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Hall, T.; Force, J.E.; Wulfhorst, J.D. Sociodemographic effects on place bonding. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zen, W. The connection between people and place: The place attachment. Adv. Psychol. 2018, 8, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X. Quantitative Research on the Integrated Form of the Two-Dimensional Plan to Traditional Rural Settlement. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Yin, D.; He, C.; Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Meng, S.; Ren, Q.; Zhao, R.; Inostroza, L. Linking ecosystem services and subjective well-being in rapidly urbanizing watersheds: Insights from a multilevel linear model. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, D. The impact of community environment on the rural residents subjective well-being: Based on the empirical study of Luochuan county, Shaanxi province, China. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Yin, C. Impacts and conditional effects of population density on commuting duration: Evidence from shanghai. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, K.; Healey, M. Place attachment and place identity: First-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M. Cross-validation of abbreviated perceived residential environment quality (PREQ) and neighborhood attachment (NA) indicators. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, B. Concepts analysis and research implications: Sense of place, place attachment and place identity. J. South China Norm. Univ. 2011, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, B.; Klinkenberg, B. Visualization of place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 99, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimbach, D.J.; Fleming, W.; Biedenweg, K. Whose Puget Sound?: Examining Place Attachment, Residency, and Stewardship in the Puget Sound Region. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 112, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chao, T.-Y.S.; Chan, E.H.W. Investigating the links between environment and older people’s place attachment in densely populated urban areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Num. | Place Identity | Place Dependence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | This village is very special to me. | This village better meets my residential needs than other places. |

| 2 | I am extremely satisfied with the living environment in this village. | The living environment in this village cannot be replaced by other places. |

| 3 | I strongly identify as a member of this village. | The feeling I get here cannot be obtained in other places. |

| 4 | I deeply identify the culture and spirit of this village. | Many things I can do in this village cannot be done elsewhere. |

| 5 | I consider this village a part of my life. | When I go to other places, I feel more satisfied. |

| 6 | If possible, I would like to live here long-term. | What I do in other places feels the same as what I do in this village. |

| 7 | I am happy to share my hometown (this village) with others. | In my free time, I prefer to stay in this village rather than go elsewhere. |

| 8 | I would feel very reluctant to leave this village. | I would rather do what I want to do in this village than go elsewhere. |

| Level | Variables | Indicator Description |

|---|---|---|

| Community scale | Path | |

| Distance to town left | Distance from village left to town left (km). | |

| Road density | Calculated as , where li is the length of each road in the village, and S is the village area [38]. | |

| Edge | ||

| Rural shape index | Calculated as [38], where λ is the aspect ratio of the village boundary, P is the perimeter, and A is the area. | |

| Rural agglomeration degree | Calculated as , where S is the area of the study object, and πR2 is the area of its minimum bounding circle. | |

| Landscape boundary comfort | Residents rate the comfort of rural landscape boundaries (1–5 points, where 1 = least comfortable, 5 = most comfortable); scores are standardized and averaged. | |

| District | ||

| Population density | Rural permanent population/rural administrative area (persons/mu). | |

| Per capita cultivated land | Rural cultivated land area/rural administrative area (mu/person). | |

| Environmental tidiness | Residents rate environmental tidiness (1–5 points, where 1 = least tidy, 5 = most tidy); scores are standardized and averaged. | |

| Node and Landmark | ||

| Service facility density | Number of supporting facilities in the village/rural administrative area (units/1000 mu). | |

| Service facility diversity | Calculated as =, where Ad is service facility diversity, k is the number of service facility types, and p is the proportion of each facility type in total spatial activities. | |

| Richness of landmark elements | Number of landmark elements (sacrificial buildings, sacrificial squares, traditional gatehouses, ancient bridges, ancient trees)/rural administrative area. | |

| Individual scale | Gender | Male = 1; female = 0. |

| Age | Continuous variable (years). | |

| Education | None = 1, primary school = 2, junior high school = 3, senior high school/vocational school = 4, and university degree or above = 5. | |

| Residence duration | <5 years = 1, (5,10] years = 2, (10,20] years = 3, (20,40] years = 4, and >40 years = 5 | |

| Current residence | Within the survey area = 1; outside the survey area = 0. |

| Personal Attributes | Classification | Sample Size | Mean of Place Attachment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 240 | 0.607 |

| Female | 208 | 0.617 | |

| Age | <30 | 89 | 0.606 |

| (30,40] | 102 | 0.608 | |

| (40,50] | 113 | 0.600 | |

| (50,60] | 107 | 0.618 | |

| (>60] | 37 | 0.644 | |

| Education | None | 126 | 0.612 |

| Primary school | 64 | 0.620 | |

| Junior high school | 153 | 0.614 | |

| Senior high school/vocational school | 29 | 0.601 | |

| University degree or above | 76 | 0.603 | |

| Residence duration | <5 | 15 | 0.604 |

| (5, 10] | 27 | 0.578 | |

| (10, 20] | 75 | 0.613 | |

| (20, 40] | 132 | 0.621 | |

| >40 | 199 | 0.610 | |

| Current residence | Within the survey area | 319 | 0.611 |

| Outside the survey area | 128 | 0.619 |

| Indicator | Mean Value | Standard Deviation Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance to town center | 2.497 | 1.291 | km |

| Road density | 2.096 | 2.202 | m/km2 |

| Rural shape index | 2.066 | 0.643 | - |

| Rural agglomeration degree | 0.271 | 0.133 | - |

| Landscape boundary comfort | 4.000 | 0.349 | - |

| Population density | 0.388 | 0.156 | person/mu |

| Per capita cultivated land | 0.184 | 0.051 | mu/person |

| Environmental tidiness | 4.036 | 0.351 | - |

| Service facility density | 4.330 | 9.270 | unit/mu |

| Service facility diversity | 3.586 | 2.171 | - |

| Richness of landmark elements | 0.390 | 0.338 | unit/mu |

| Indicator | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | ||

| Community scale | Path | ||||||||||

| Distance to town center | −0.1174 * | 0.1658 | −0.0166 * | 0.1132 | |||||||

| Road density | 0.0365 | 0.1314 | 0.2107 | 0.1122 | |||||||

| Edge | |||||||||||

| Rural shape index | −0.1504 | 0.0612 | −0.1503 | 0.1013 | |||||||

| Rural agglomeration degree | 0.1451 * | 0.081 | 0.1448 * | 0.0576 | |||||||

| Landscape boundary comfort | 0.1227 | 0.1174 | −0.0092 | 0.0862 | |||||||

| District | |||||||||||

| Population density | −0.1473 | 0.1505 | −0.0851 | 0.1129 | |||||||

| Per capita cultivated land | 0.1585 | 0.1023 | 0.1435 | 0.0941 | |||||||

| Environmental tidiness | 0.0937 * | 0.1647 | −0.128 * | 0.1003 | |||||||

| Node and Landmark | |||||||||||

| Service facility density | 0.1065 | 0.1489 | 0.2401 * | 0.0781 | |||||||

| Service facility diversity | −0.018 | 0.0986 | −0.0929 | 0.0915 | |||||||

| Richness of landmark elements | 0.1464 * | 0.1178 | 0.0767 ** | 0.0989 | |||||||

| Individual scale | Gender | −0.2191 ** | 0.1017 | −0.2233 * | 0.1013 | −0.2084 ** | 0.1013 | −0.2267 ** | 0.102 | −0.2404 ** | 0.1018 |

| Age | 0.0629 * | 0.0368 | 0.0646 * | 0.0367 | 0.0651 * | 0.0367 | 0.058 | 0.0369 | 0.0575 * | 0.0368 | |

| Education | 0.0038 | 0.0366 | 0.0007 | 0.0385 | 0.0008 | 0.0365 | 0.0009 | 0.0368 | −0.0027 | 0.0367 | |

| Residence duration | 0.0939 ** | 0.0434 | 0.0959 * | 0.0431 | 0.0838 ** | 0.0432 | 0.1064 ** | 0.0429 | 0.1084 ** | 0.0429 | |

| Current residence | −0.0427 | 0.0933 | −0.0456 | 0.0912 | −0.0502 | 0.0915 | −0.0209 | 0.0923 | −0.0298 | 0.0923 | |

| Constant | 16.46385 | 1.235 | 17.385 | 1.362 | 19.043 | 1.167 | 18.902 | 1.736 | 20.446 | 1.924 | |

| Log likelihood | −1264.754 | −832.479 | −834.675 | −894.416 | −946.2735 | ||||||

| ICC/% | 6.61 | 6.94 | 7.32 | 9.89 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X. How Does the Built Environment Shape Place Attachment in Chinese Rural Communities? Buildings 2025, 15, 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132250

Zhang L, Zhang C, Wang X. How Does the Built Environment Shape Place Attachment in Chinese Rural Communities? Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132250

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Liangduo, Chunyang Zhang, and Xin Wang. 2025. "How Does the Built Environment Shape Place Attachment in Chinese Rural Communities?" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132250

APA StyleZhang, L., Zhang, C., & Wang, X. (2025). How Does the Built Environment Shape Place Attachment in Chinese Rural Communities? Buildings, 15(13), 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132250