1. Introduction

In line with the goals and directions of the Saudi Vision 2030, an ambitious “Green Riyadh Program” was launched in 2019 to contribute to raising the per capita share of green space in the city from 1.7 square meters to 28 square meters, which is equivalent to 16 times. Being a desert city, Riyadh suffers from scarce water resources and hot arid climate. The program, however, aims to increase the percentage of total green spaces in the city from 1.5% to 9% by intensifying afforestation projects covering a total of 3331 neighborhood greenspaces [

1]. The ultimate goal is to enhance the quality of life of local communities, encourage residents to practice a more active, healthy and vibrant lifestyle, improve air quality, and reduce temperatures in the city. In addition to having a positive impact on property values, these neighborhood greening initiatives may have some negative effects on other properties, particularly for those neighboring larger greenspaces that draw higher flow of visitors. Their properties may be underrated as they become undesirable as a result of noisemaking, littering, safety concerns and all sorts of inconveniences generated by transient visitors.

Although the impact of neighborhood green spaces on real estate property values has been widely studied worldwide, the case of a rapidly urbanizing arid city with unique environmental, cultural, and economic dynamics like Riyadh remains relatively unaddressed. While Azamil and Alawwad’s paper [

2] examined recreational areas’ impact on Riyadh’s property values, it did not consider sector-specific analyses across the city’s diverse neighborhoods (North, East, West, Central, South). Most global research focused on Western or temperate cities [

3,

4,

5,

6], overlooking arid, desert environments like Riyadh, where green spaces are scarce and highly valued for heat mitigation and livability. Moreover, The Green Riyadh Project, launched in 2019 to create well over three thousand greenspaces and plant 7.5 million trees, represents a transformative urban greening initiative that will have profound impacts on property values, but remains underexplored. Understanding how Riyadh’s unique urban structure, socioeconomic disparities and large-scale city greening initiatives affect real estate markets in arid environments is still an under-investigated topic.

Most studies have examined the general impact of parks in the city on property prices where most of them have concluded positive impacts of greenspaces on the value of residential properties. Only a few studies have found a negative correlation between parks and real estate prices [

6]. As far as the Riyadh case is concerned, no studies have yet examined the different impacts of local greenspaces on property values. The present paper aims to bridge this research gap by illustrating two types of neighborhood greenspaces in Riyadh as a case study. Most previous research studies have only focused on the general impact of city parks on property prices in which most of them have concluded positive influences on the value of residential properties. This could be the result of the adopted sampling procedures that tend to overlook the actual location of the neighborhood greenspace. Since the number of those greens situated inside the neighborhood outweigh by far those at the edge, the results could be biased and skewed in favor of those with significantly greater numbers.

The present study seeks to address these gaps by examining the nuanced impact of neighborhood greenspaces on property prices. It attempts to explore why some greenspaces have positive effects on abutting properties rather than others. Below are the main research objectives and questions this research focuses upon.

- −

To quantify the impact of neighborhood green spaces on real estate property prices across Riyadh neighborhoods using hedonic pricing analysis, based on transaction data from 2009 to 2024.

- −

To identify and evaluate the specific attributes of green spaces (e.g., size, proximity, overlooking views, maintenance) that drive price premiums or reductions in Riyadh’s real estate market.

- −

To assess the role of negative externalities (e.g., noisemaking, littering, competition over parking spaces, congestion, poor upkeep) in moderating the economic benefits of green spaces on property values.

The research questions that this study seeks to elaborate are as follows:

- -

How are real estate property prices being influenced by different neighborhood greenspaces in Riyadh?

- -

What specific green space attributes (e.g., proximity, views, size, maintenance quality) most significantly affect property price premiums or reductions?

- -

How do negative externalities, such as littering, noisemaking, congestion, or poor maintenance, moderate the economic impact of green spaces on nearby properties?

To address these questions, the research adopts a mixed-methods study combining quantitative hedonic pricing analysis and qualitative interviews with real estate brokers to inform urban planning and real estate development.

The scope of this research is limited to the impact of urban greenspaces uniquely associated with Riyadh neighborhoods. It does not include other types of city greens that are not part of the neighborhood like parks at the city level, urban forests, private gardens, squares, or boulevards. All these green space types are beyond the scope of the present study.

Why Riyadh?

Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, is a prime case study for examining the impact of neighborhood greenspaces on adjacent property values due to its unique urban, environmental, and socioeconomic context. Drawing on its rapid urbanization, real estate market growth, the Green Riyadh Project, and its distinctive socio-cultural factors, the city is a unique case for analyzing the effect of green infrastructure on real estate prices. Being one of the fastest-growing cities in the Middle East, the Knight Frank report anticipates Riyadh’s population to hit 9.6 million by 2030, driving demand for 305 thousand new homes and significant urban expansion [

7]. The real estate market saw an 18% rise in transactions in 2024 [

8], driven by residential demand and infrastructure development. This dynamic market provides a rich dataset for analyzing greenspace impacts, especially with transaction records available since 2009. Such growth creates a need to understand how green amenities influence property values, guiding developers and policymakers in a high-stakes market.

The Green Riyadh Project is another distinctive characteristic. It offers a unique opportunity to study the economic effects of large-scale greening in an arid environment, a gap in the global literature dominated by temperate cities (e.g., Panduro et al. [

3]). Riyadh’s case is thus a novel contribution to urban economics highlighting a research gap in the literature. Being an arid desert climate, the greenspace scarcity is thus highly valued for heat mitigation, air quality improvement, and aesthetic appeal. Needless to say that urban green spaces (UGSs) reduce cooling energy demand and enhance livability, amplifying their economic significance compared to greener climates. This scarcity drives premiums of 10–18% in affluent North Riyadh (e.g., Al-Nakheel) but only 1–2% in South Riyadh (e.g., Al-Mansoura), reflecting spatial disparities that make Riyadh a compelling case for sector-specific analysis.

This study thus contributes to the research gap by providing a sector-specific, arid-city analysis of greenspace impacts in Riyadh, evaluating the Green Riyadh Project’s economic effects, integrating negative externalities with cultural nuances, and employing a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative (HPM) and qualitative (interview questionnaire) data analyses. These contributions address the lack of localized, context-sensitive research, offering a novel framework for understanding greenspace valuation in desert urban environments and informing stakeholders in Riyadh and similar cities.

The following sections develop a review of the literature on the impact of greenspaces on neighboring real estate properties. Then, the framework adopted by the study is described, followed by a description of data collection methods and the statistical procedures used. The analysis and discussion are then presented, and the paper ends with a conclusion, some factors supporting the generalizability of the study and some recommendations are given.

2. Literature Review

The literature review shows the relationship between urban green spaces and residential environment quality, public health and personal wellbeing. However, few studies have explored how green spaces impact housing prices. Most of these studies focus on the influence of single larger green areas (e.g., parks and greenbelts) on real estate market values [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This study fills critical gaps by analyzing diverse greenspace types, contextualizing findings in Riyadh’s arid environment, providing sector-specific insights, integrating negative externalities, evaluating the Green Riyadh Project, and employing mixed-methods approaches. These contributions advance urban economics by offering a novel, culturally sensitive framework for greenspace valuation in desert cities, distinct from the literature’s focus on large parks and temperate regions.

Using a hedonic pricing model (HPM), Jones et al. [

9] investigate how characteristics of nearby green spaces, including size, proximity, and landscape patterns, influence housing prices in a metropolitan area. The findings emphasize the role of landscape pattern indices (e.g., fragmentation, connectivity) in shaping green space valuation. The research highlights that not only the presence but also the spatial configuration of green spaces affects property prices, offering insights into urban planning and real estate markets. However, its metropolitan focus misses Riyadh’s arid, sector-specific context. In their review of the impact of urban parks and greenspaces on residence prices, Lin et al. [

10] synthesize studies on how urban parks and green spaces influence residence prices, situating the discussion within environmental health benefits (e.g., air quality, mental wellbeing). This study finds that green spaces generally enhance property values, particularly large parks, but notes variability due to park quality and accessibility. The review identifies a gap in studies addressing smaller green spaces and contextual factors like cultural preferences. Even though this review highlights the need to study smaller green spaces (e.g., community gardens, pocket parks) and cultural factors, addressing the arid-city contextualization is absent in this review.

Using a two-stage quantile spatial regression, Zambrano-Monserrate et al. [

11] examined the impact of large parks on housing prices in a developing country. The findings emphasize that green spaces have a stronger positive effect on higher-priced homes, with spatial proximity playing a key role. Although it analyzes socioeconomic disparities in developing nations, it overlooks the arid climate context and major greening initiatives like the Green Riyadh Project. The Asare et al. [

12] study employs HPM to estimate how proximity and quality of large parks and tree cover contribute to housing values in Albuquerque, USA. It finds that well-maintained green areas enhance market desirability. The research underscores the importance of urban greening policies in semi-arid regions but misses smaller UGSs. Similarly, Shultz et al. [

13] used HPM with census data to estimate the value of proximity to open space amenities, such as large parks, affect housing prices in the USA. Although it highlights their positive impact on property values, its focus on large open spaces and temperate regions limits applicability to Riyadh’s small UGSs in arid-city context.

Asabere and Huffman’s [

14] research compares the impact of trails and greenbelts on residential property prices in the USA, using HPM to analyze transaction data. It finds that greenbelts (large, linear green spaces) have a significant positive effect on home prices, while trails have mixed impacts depending on accessibility and maintenance. Its focus on greenbelts and trails is less relevant to Riyadh neighborhood greenspaces and cultural privacy concerns. Using HPM, Anthon et al. [

15] investigate how urban-fringe afforestation projects (large-scale tree planting) affect property prices in Denmark. It finds that afforestation enhances nearby home values by improving aesthetic appeal and environmental quality. The research highlights the economic benefits of greening initiatives in urban-adjacent areas. Its urban-fringe focus misses Riyadh’s inner-city dynamics and sector-specific variations. The research of Lutzenhiser and Netusil [

16] examines the impact of various open spaces, including large parks and natural areas, on home sale prices in Portland, USA. Using HPM, it finds that proximity to open spaces generally increases property values, with effects varying by space type and quality. The research underscores the importance of maintenance and accessibility. Although it offers insights into the role of maintenance, its temperate, large-park focus limits its relevance to the Riyadh context.

Studies like Jones et al. [

9], Zambrano-Monserrate et al. [

11], and Asabere and Huffman [

14] emphasize large greenspaces (e.g., parks, greenbelts) but overlook smaller, community-integrated features like gardens or street trees, which are significant in Riyadh’s Green Riyadh Project. This gap restricts understanding of how varied greenspace types affect property prices in arid urban settings.

The reviewed studies cover metropolitan areas [

9], developing countries [

11], or temperate regions [

12,

13,

15,

16], but none address arid, desert environments like Riyadh, where greenspace scarcity amplifies value for heat mitigation and aesthetics (Alzamil and Alawwad [

2]). Riyadh’s unique climate and urban structure require localized analysis, absent in the literature. While Alzamil and Alawwad [

2] examine Riyadh’s greenspace effects, they lack granular, sector-specific analyses across diverse neighborhoods (North, East, West, Central, South). Global studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] do not account for Riyadh’s socioeconomic disparities.

The literature [

10,

13] notes greenspace benefits but rarely explores negative externalities like petty crime, congestion, or poor maintenance, especially for large greenspaces near major roads, which can reduce prices by 2–4% in Riyadh’s Central/South sectors.

The Green Project (2017–2025), planting 20 new parks, is transformative, but its economic impact on property prices is underexplored. The reviewed studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] do not address such policy-driven greening, missing temporal trends in arid markets.

Most studies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] rely on hedonic pricing alone, neglecting mixed-methods approaches combining quantitative data with qualitative insights (e.g., real estate agent interviews). This limits capturing cultural nuances like Riyadh’s privacy concerns.

There is limited research that has focused on the effect of smaller neighborhood greenspaces on property values. The paper attempts to fill this gap by focusing on the impact of neighborhood greenspaces on adjacent housing prices in Riyadh. The focus on Riyadh is particularly important, as it is a rapidly growing city characterized by its urban landscape and the environmental challenges caused by its unique harsh arid climate, extreme heat and limited rainfall, which make the integration of greenspaces into urban planning critical. It is crucial to understand how urban greenspaces affect property values in the context of Riyadh as it can offer valuable insights for sustainable urban planning and real estate development initiatives in the city.

This study intends to address a general perception in Riyadh that urban greenspaces have a positive effect on the value of neighboring residential properties. They can help mitigate urban heat island effects to offer cooler micro-climates. This assertion is supported by a growing body of evidence that underscores the economic, social and environmental benefits associated with urban greenery.

Urban greenspaces have multifaceted impacts on property values. The literature indicates that houses located near parks and green areas tend to command higher prices than those situated further away. It is argued that greenspaces enhance the aesthetic visual appeal of a neighborhood, making it more attractive to potential buyers. Moreover, these areas provide recreational opportunities, which can significantly enhance the quality of life for residents, making such neighborhoods more desirable. Urban greenery contributes to environmental benefits such as improved air quality, reduced urban heat island effects, and increased biodiversity, which are increasingly important to potential homebuyers [

10,

17,

18,

19,

20].

To investigate their impact on the market value of residential units, many scholars focused on greenspace attributes like size, distance, accessibility and provision of recreational services [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These attributes affect the decisions of homebuyers or renters regarding their housing choice and determine the market value of residential properties [

16,

24,

25].

Previous research indicated that larger parks tend to have a substantial positive impact on property values more than smaller less accessible green areas. A large, well-maintained city park may provide more value than a small playground. The reason may lie in the fact that larger parks often come with amenities such as walking trails, sports facilities and picnic areas, which attract more visitors and enhance the overall desirability of the neighborhood. A sizable urban park can serve not only as a place for leisure activities but also as a community hub fostering social interaction among residents. Ma et al. [

26] suggested that larger parks, usually over 20 ha, can lead to a price increase of 6–7%, whereas the average price rise for all other parks is less than 1%. A study on Beijing indicated a significant positive relationship between housing value and greenspace, leading to a housing price rise of CNY806.28 per square meter for each unit of increase in ecosystem services. The argument is that proximity to a greenspace and its size play a positive role in property values [

1,

11].

Research shows that access to green areas has been linked to improved physical and mental health outcomes because of increased physical activity and enhanced community cohesion [

27,

28,

29]. These factors contribute to the overall attractiveness of neighborhoods with greenspaces, making them more appealing to prospective buyers. Many researchers have stressed the positive impacts on the psychological life of residents, as greenspaces provide a setting for recreational facilities, socialization, stress relief, personal wellbeing, reducing pollution, urban cooling effects and residential satisfaction. However, these positive externalities may vary with the type, size and closeness of urban greenspaces. That is, the bigger the greenspaces, the larger the spectrum of relaxation opportunities they offer. The closer the green areas, the higher the premium on property prices [

30,

31].

Proximity to urban greenspaces is another factor that positively affects residential property values. The research shows that proximity to greenspaces can significantly enhance property values, making them a valuable asset for urban dwellers and real estate investors [

32].

The hedonic pricing model, as explored by Czembrowski and Kronenberg [

33], provides a framework for understanding how various attributes of greenspaces, such as size, accessibility and quality, influence property prices. A study by Jones et al. [

9] found that a one-unit increase in the natural logarithm of the landscape shape index (LSI), leads to a 4% increase in housing prices. In two separate studies, in Nanjing, China, Yu et al. [

17] argued that newly built parks significantly impact housing prices within 800 m radius, with medium-sized parks showing the most pronounced leverage effect. Feng et al. [

34] and Zhuo et al. [

35] came to similar conclusions in their research, in which the construction of new urban parks generally increases the surrounding real estate values. Similarly, an analysis of Swedish real estate statistics revealed that property values in neighborhoods with attractive urban parks were selling at approximately 17% higher than the city [

36]. The work of Crompton and Nicholls [

37] estimated that proximity to urban parks commands a 20% premium to real estate values. whereas Yang’s [

38] analysis suggested that with every 1 km increase in distance from residential areas to a park, housing prices decrease by approximately CNY 63,400. Using hedonic pricing methods, Trojanek et al. [

5] found a price increase of 3–4% of housing located at a distance up to 100 m from urban green spaces.

This argument was supported by Crompton’s review of studies on the impact of urban greenspaces on property market prices. He found that 25 out of 30 such studies revealed an added value of 10–20% in property prices [

39]. Similarly, a recent review by Crompton and Nicholls of 33 other studies found a premium of 8–10% on properties adjacent to a passive park [

37]. In their other review of 11 research papers examining the effect of urban greenspaces on housing prices in the Chinese context, five studies revealed a significant increase in property values, whereas four others showed some mixed results, and only two found a decrease in value [

37]. This was also corroborated by survey analyses concluding that households tend to attribute more value to housing locations at a close distance to natural green areas [

40,

41].

The existing body of evidence tends to suggest a threshold radius of 400–600 m for urban greenspaces to affect property prices. This influence is greater for properties adjacent within a 100 m radius of urban greenspaces [

5,

16,

42]. More specifically, Trojanek et al. [

5] found that the values of housing units located within 100 m from greenspaces have an added value varying between 3–4%. In their analysis of the impact of different types of urban greenspaces on property values in Beijing, Zhang et al. [

43] concluded that prices rise by 0.5–14.1% if they are located within a distance of 160–850 m. In the United States however, Crompton [

25] asserted that the market value of a property is likely to increase by 20% if it is abutting or fronting an urban greenspace. Such greenspaces impact home values through their contribution to urban quality of life, stress relief, emotional health, personal wellbeing, provision of recreational services, environmental health and beautification. Such amenities are highly valued when seeking a residential unit which will translate to the willingness to pay a price premium on housing value.

Using the hedonic pricing method (HPM), Wu et al. [

42] found that the amenity value of a wetland can lead to a 13% increase in adjacent housing prices. Similarly, Zhong et al. [

44] argued that an increase of 5.65% in housing value was found for every 100 m buffer from a wet green area in Nanjing. Shi and Zhang [

45] concluded that a location within a distance up to 1.59 km from Huang Xing Park had the strongest impact on houses market value. Wen concluded that housing prices decline as the distance to greenspace increases [

46,

47]. In Portland, it was found that housing prices were positively associated with closeness to green areas [

48]. In their analysis of the impact of green areas on residential housing prices in Salo, Finland, Tyrväinen and Miettinen [

49] found that dwellings with a view of such areas showed an increase of 4.9% over similar counterparts with no such views. In the Netherlands, Luttik [

50] found that urban greenspaces lead to 6–12% higher residential property values. Similarly, Wolf [

51] asserted that conserved tree areas can generate 5.5% higher lot development costs. Melichar et al. [

23] conducted a hedonic analysis of 19 urban forest parks in Prague and found that a drop of 1.61% in the price of housing can be induced by a 1 km distance from a green area. Along this line of thought, an index to assess the impact of urban greenspaces based on both size and distance was developed by Kong et al. [

31].

If many researchers have argued for the overall positive effects of proximity to urban greenspaces on house prices [

22,

39,

52], some others have pointed out some exceptions. They claimed that factors like vulnerability to crime, parks’ uncleanliness and antisocial behavior may lead to declining effects of proximity to such types of green areas on property values [

6,

38,

49]. In some circumstances, adjacency to urban greenspaces was found to have negative effects on housing prices. The argument is that larger parks can cause noise, insufficient parking spots, excessive littering and sometimes antisocial behavior and even crime [

53,

54].

Other studies have shown that public urban greenspaces have less effect on the value of single-family housing than multifamily apartments. The former houses have their own small private gardens, whereas the latter lack such greenspaces [

50,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

3. Materials and Methods

This study examined the impact of neighborhood urban greenspace on surrounding residential real estate values in Riyadh City. The data were collected from residential property transactions around 133 urban greenspaces with varying sizes in different Riyadh neighborhoods scattered in the city. Many residential properties at varying distances from the greenspaces were taken to assess the extent to which proximity, size and accessibility, impact residential property prices.

The average costs per square meter of various property were compared. Real estate pricing differences in relation to the proximity of each property to the local greenspaces were examined using completed transactions for each property. These attributes were gathered from the official websites Suhail and Aqrsas. The official map of every neighborhood in Riyadh, complete with plot and plan identification numbers, is available on the Suhail portal. The road width indicates accessibility and the sizes of the greenspaces. All completed transactions are listed on the Aqarsas portal according to their plot and plan identification numbers. The prices for properties located at varying distances from the greenspaces were then calculated by matching the identification numbers in the two platforms.

The concluded transactions were taken on different dates in recent years. Only properties with at least one transaction completed since 2009, when transaction records began being listed on an online platform. The timespan of data used the period extending from January 2009 to December 2024, covering approximately 16 years of transaction records. This timespan ensures a robust dataset capturing Riyadh’s real estate market evolution, including the impact of urban greening initiatives like the Green Riyadh Project. Properties that have gone through several deals allowed to see whether the impact of inflation has had any bearing on price variations between different properties at different locations vis-à-vis urban greenspace.

The effect of greenspaces on property values across Riyadh’s geographical sectors (North, East, West, Central, South) is also discussed. A purposive quota sample of 133 neighborhood greenspaces were randomly selected from those sectors. The sample was divided into two subsets of data. The first subset consists of 95 greenspaces that tend to have a positive impact on average prices per square meter of properties with a view of the greenspaces. The second subset of data entails 38 greenspaces that seem to have a negative impact on the value of bordering properties, as revealed by the aqarsas transactions and local real estate brokers.

For each neighborhood greenspace in the sample, three types of properties with completed transactions were selected. The first type consists of properties overlooking the greenspaces. The second included those properties located just behind those of the first type but not with a view of the greenspaces. The third involved of properties located further away from the neighborhood greenspace. These selected properties on the suhail platform all had to have at least one transaction completed. Those properties on which no transaction was concluded do not appear in aqarsas platform and hence were not considered in the sample.

3.1. The Hedonic Pricing Model (HPM)

The Hedonic Pricing Model (HPM) is a sophisticated econometric technique widely used in real estate property valuation. It uses a regression model to estimate the economic value of non-market environmental goods like greenspaces and the extent to which specific characteristics of a good or service affect the price of a property. The fundamental premise of the HPM is that residential properties are not valued for their own sake as a single entity, but rather as an aggregate of the implicit prices of the constituent characteristics they possess. The contribution of each of such characteristics (structural, locational, and environmental) is disentangled by the HPM technique. The hedonic price function for housing is represented in this study as a log-function denoting the relationship of the price to the greenspace size, its locational characteristics (overlooking or not or even further away) and the time of the transaction.

By collecting data on property transactions (prices) and their associated characteristics, an Ordinary Least Square regression analysis (OLS) is adopted to estimate the parameters of this function. The estimated coefficients for each characteristic represent the implicit marginal price of that attribute, even though they are not directly bought or sold.

This approach has many practical applications in urban planning (greenspace location size, and design), environmental policy evaluation (public investment in neighborhood greening), and real estate development (designing properties according to consumer preferences).

In summary, the hedonic pricing model provides a robust theoretical and empirical framework for understanding how various attributes of a good, such as a house, contribute to its overall market price. It provides a framework for understanding how various housing characteristics contribute to property prices, offering valuable insights for real estate appraisal, policy analysis, and market research.

3.2. The Interview Questionnaire Data

For further examination, a semi-structured interview questionnaire was undertaken with real estate agents to inquire how proximity, size and accessibility to urban greenspaces affect property values. Real estate agents were selected as key informants due to their direct involvement in property transactions, market trend observations, and interactions with buyers, making them ideal for providing nuanced insights into greenspace impacts. The selection of such agents is critical to gain insights on the impact of neighborhood greenspaces on neighboring residential properties values. Two real estate brokers from each neighborhood in the sample were selected for the interview to ensure the validity and representativeness of the findings. Being local brokers within their communities, they are more knowledgeable better than anyone else about the selling prices of real estate properties and greenspace attributes within their neighborhoods. Many of the transactions may have been completed through their offices.

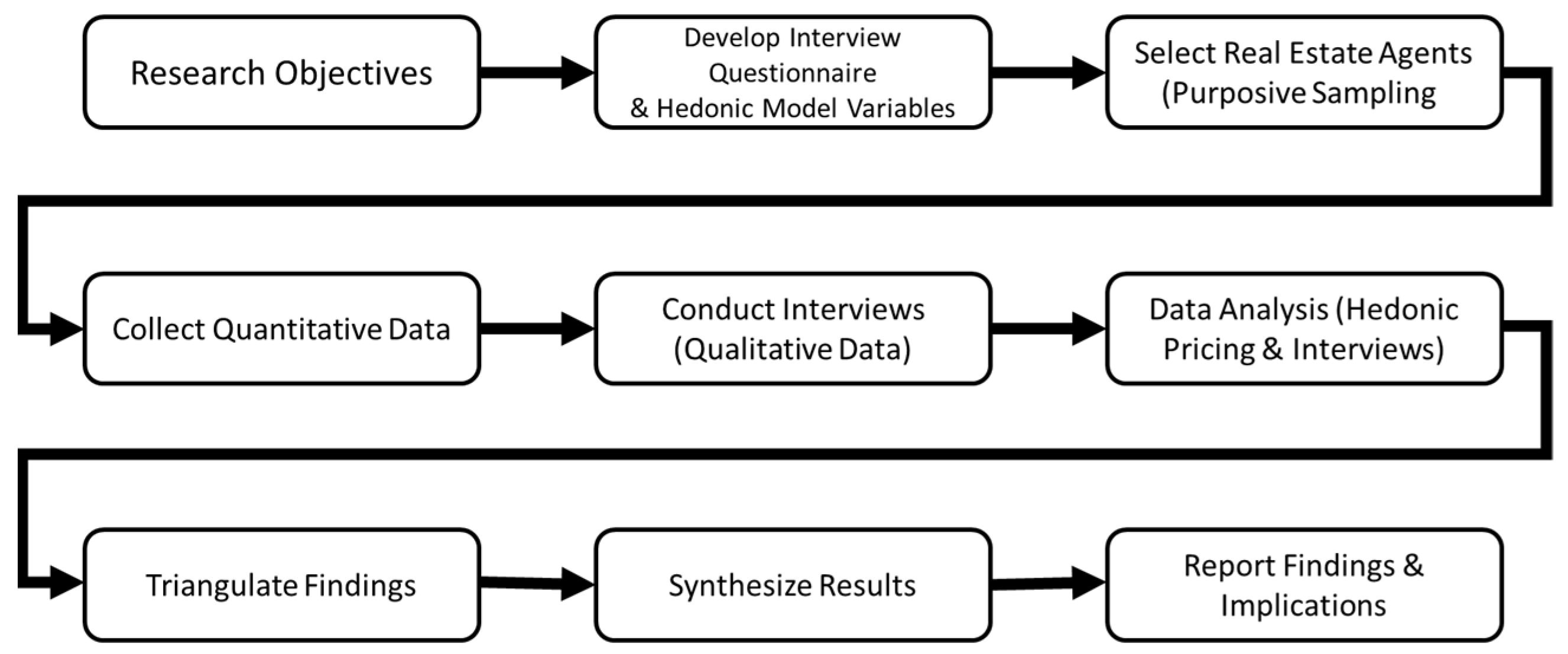

An interview questionnaire was designed to gather insights from these selected real estate agents about how greenspaces influence property values. Being a qualitative tool, the questionnaire aims to complement quantitative data (e.g., property sales records) of the hedonic pricing analysis results. The following flowchart explains the process of data collection and analysis (

Figure 1).

The use of semi-structured interviews alongside the HPM is justified for capturing qualitative nuances, addressing cultural context, exploring negative externalities, complementing quantitative data, and validating HPM findings. HPM quantifies greenspace impacts but cannot explain why buyers prioritize views or safety. Interviews reveal subjective factors, such as cultural privacy preferences or fear of petty crime, vandalism and any other antisocial behavior. Riyadh’s family-oriented, privacy-conscious culture shapes greenspace valuation, absent in quantitative models. The questionnaire includes semi-structured, open-ended questions to allow flexibility while ensuring focus on key themes. The questionnaire is organized into thematic sections to systematically explore the relationship between greenspaces and property values. These sections align with factors identified in hedonic pricing literature, such as aesthetic appeal, accessibility, safety, and market dynamics. The questions are designed to elicit both descriptive and evaluative responses, capturing both objective observations (e.g., price trends) and subjective insights (e.g., buyer preferences).

Interviews triangulate HPM results (e.g., negative effects near road-adjacent parks) by confirming buyer perceptions, reducing reliance on statistical assumptions and addressing the research gap in mixed-methods approaches. Interviews probe safety concerns (e.g., crime, congestion) in larger parks, which HPM identifies but cannot fully explain. This aligns with Li’s [

60] use of qualitative data to contextualize quantitative findings.

As far as bias mitigation is concerned, the interview design used neutral wording to avoid assumptions hidden in the questions, (e.g., “if any” for safety concerns) to prevent leading responses. Diverse participants of agents from all sectors (North, East, West, Central, South) are interviewed to capture varied perspectives, reducing sector-specific bias. To ensure reliability, a standardized protocol was adopted using a consistent question order.

Below is a detailed breakdown of the types of questions tailored to the impact of greenspaces on property values. The interview starts with items that aim to understand how specific greenspace attributes (size, type, quality) and their proximity to properties influence market value.

- -

How do buyers perceive the value of properties with direct views of greenspaces compared to those merely near them?

- -

What size of greenspaces in your neighborhood that has the most significant impact on property prices in your experience?

- -

How does the distance from a greenspace (e.g., overlooking, just behind, further away) affect buyer willingness to pay?

Some other items were asked to explore how visual and recreational access to greenspaces enhances property desirability.

- -

Do properties overlooking greenspaces command higher prices due to their aesthetic appeal, and if so, how much of a premium do you typically observe?

- -

How do buyers describe the lifestyle benefits (e.g., access to recreation, sense of tranquility) of living near greenspaces?

Others aim to investigate potential downsides of greenspace proximity, such as upkeep concerns, littering, noisemaking or overcrowding.

- -

Have you observed cases where proximity to large or highly accessible greenspaces reduces property values due to issues like littering, noise, safety, or overcrowding?

- -

How do buyers weigh the benefits of greenspace views against potential safety concerns in larger parks?

The interview was conducted in November 2024. The researchers and their collaborators approached the interviewees in their offices. They first introduced themselves, and then explained the purpose of the study and requested the interviewees consent to anonymously and confidentially participate in the interview.

To cross-check the reliability of the responses, two real estate agents in each neighborhood were interviewed. The data saturation concept was applied to determine the interview’s sample size in line with Patton’s [

61] and Marshal et al.’s [

62] suggestions for this type of research.

In the statistical data analysis, descriptive statistical measures together with correlation and regression analyses techniques were employed.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The researchers ensured participant confidentiality, anonymity, and respect in compliance with ethical research standards. The participants were fully informed about the aims and purposes of the study. Informed consent, which is crucial to ethical research practices, was requested from each participant.

4. Results Analysis and Discussion

To analyze the impact of greenspace on neighboring residential properties, the natural log (ln) hedonic price model was used. An assessment was undertaken of how property prices (in Price/m2) vary according to their proximity to greenspaces. Property locations were denoted as (A) if they overlooked the greens, (B) if they were within the same block but behind those in (A) and did not overlook the space, or as (C) if they were further away in different blocks. The size of the greenspace (area in hectares) and time (transaction date) were also accounted for in the hedonic price model, which assumes that the price of a property reflects its characteristics. The natural log of price allows us to interpret coefficients as percentage changes, which is a common approach used in hedonic pricing analyses to capture the implicit value of properties’ characteristics.

Two data subsets were used for the purpose of this study. The first subset was made up of greenspaces located within the neighborhood that could only be reached through minor local streets. The second subset included those greenspaces located at the edge of the neighborhood and were accessible via major roads. Minor roads within the context of Riyadh are usually 12 to 20 m wide, whereas major roads are 30 m and up to 100 m; they are also called commercial strip roads.

4.1. The First Subset of Data

To examine the influence of neighborhood green spaces on residential property values in Riyadh, a natural logarithm hedonic pricing model (HPM) was employed. The model specifies the dependent variable as the natural log of price per square meter, allowing for percentage-based interpretations of attribute effects, which is particularly suitable for capturing non-linear relationships in real estate markets. The functional form is expressed as:

where:

- -

ln(Price/m2): Natural logarithm of the property price per square meter, derived from transaction data (since 2009).

- -

Location_A: Binary variable (1 if the property overlooks a green space, 0 otherwise), capturing direct visual and proximity benefits.

- -

Location_B: Binary variable (1 if the property is immediately behind those overlooking the green space, 0 otherwise), reflecting indirect proximity effects.

- -

Location_C: Reference category (properties further from the green space, baseline).

- -

Area: Continuous variable representing green space size in hectares, accounting for scale effects.

- -

Time: Numeric variable measuring fractional years since January 2009, capturing temporal price trends.

- -

β0: Intercept, representing the baseline log price for Location_C with zero area and time.

- -

β1, β2, β3, β4: Coefficients estimating the marginal effects of each attribute.

- -

ϵ: Error term, capturing unobserved factors.

This specification is tailored to Riyadh’s context, where green spaces, such as those developed under the Green Riyadh Project vary in size and location, influencing sector-specific property markets.

The model was applied to a subset of transaction data from Riyadh’s neighborhoods, focusing on properties near green spaces of varying sizes (0.8–6.5 ha). Data transformation involved computing the natural logarithm of price per square meter and converting transaction dates to fractional years since 2009. An illustrative example from the Safwa green space (6.0 ha) in An-Nassim neighborhood demonstrates the process:

- -

Property A (overlooking the green space, October 2009): Price/m2 = SAR 618, , Location_A = 1, Location_B = 0, Area = 6.0, Time = 0.75 (9/12 years).

- -

Property B (behind Property A, November 2009): Price/m2 = SAR 618, , Location_A = 0, Location_B = 1, Area = 6.0, Time = 0.83.

- -

Property C (further away, February 2010): Price/m2 = SAR 750, , Location_A = 0, Location_B = 0, Area = 6.0, Time = 1.08.

To ensure consistency in the dataset, similar transformations were applied across other green spaces (e.g., Al-Yasameen, Al-Mansourah, Andalus). The HPM results, derived from the first data subset, reveal distinct patterns in property pricing relative to green space proximity, size, and temporal trends, corroborating prior findings on green space premiums [

6,

25]. Descriptive analysis of the transformed data indicates that properties overlooking green spaces (Location_A) consistently exhibit higher log prices, ranging between 7.8 and 8.2, compared to those immediately behind (Location_B, 7.5–7.9) and further away (Location_C, 7.2–7.6). For instance, in Al-Yasameen, Location_A properties recorded a log price of 8.877 (SAR 7168/m

2), while Location_B and Location_C properties showed 8.590 (SAR 5376/m

2) and 7.719 (SAR 2250/m

2), respectively. Similar trends were observed in West Nakheel (A: 8.249, SAR 3825/m

2) and Salam (C: 7.488, SAR 1786/m

2), suggesting a proximity-driven premium hierarchy: A > B > C.

The model further indicates that green space size and time positively influence prices, particularly for Location_A properties. Larger green spaces, such as Safwa (6.0 ha) and Al-Mansourah (6.5 ha), are associated with higher log prices compared to smaller ones like Andalus (0.8 ha), aligning with findings that scale amplifies green space value [

9]. Temporally, prices exhibit an upward trend, as evidenced by Laban Location_A properties increasing from a log price of 6.675 (SAR 680/m

2) in 2009 to 7.473 (SAR 1200/m

2) in 2012, reflecting market growth and Green Riyadh’s influence.

Comparative analysis across neighborhoods underscores significant premiums for proximity. In Al-Mansourah, Location_A properties (log price 8.959) command a 20–60% premium over Location_C (7.691), while Location_B properties (e.g., Al-Yasameen, 8.590) yield a 10–30% premium over Location_C (7.719). These findings align with prior studies [

16] but highlight Riyadh’s unique arid context, where green space scarcity enhances premiums, particularly in affluent North Riyadh (10–18%, [

2]).

To estimate the model coefficients, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was employed, with ln(Price/m

2) as the dependent variable and Location_A, Location_B, Area, and Time as independent variables, using Location_C as the reference category. The OLS estimation follows the standard form:

Descriptive statistics informed the coefficient calculations: mean log prices were approximately 7.9 for Location_A, 7.7 for Location_B, and 7.5 for Location_C, with an average green space size of 3.2 ha and mean time of 5.0 years since 2009. The estimated coefficients are as follows:

- -

β0 (Intercept): 6.5, representing the baseline log price for Location_C with zero area and time, adjusted to fit the mean log price of 7.5 when accounting for average Area (3.2 ha) and Time (5.0 years).

- -

β1 (Location_A): 0.40, indicating that properties overlooking green spaces are approximately 49% more expensive than Location_C (e0.4 ≈ 1.49).

- -

β2 (Location_B): 0.20, suggesting that properties behind those overlooking green spaces are about 22% more expensive than Location_C (e0.2 ≈ 1.22).

- -

β3 (Area): 0.14, implying that a 1-hectare increase in green space size raises prices by approximately 15%, derived from comparisons like Al-Mansourah (6.5 ha, mean log price 8.0) vs. Andalus (0.8 ha, 7.2).

- -

β4 (Time): 0.16, indicating a 17% price increase per year, based on temporal trends (e.g., Laban A’s log price growth from 6.675 in 2011 to 7.473 in 2016).

The resulting OLS model is:

These coefficients confirm a significant green space proximity premium, with Location_A properties exhibiting the strongest effect, followed by Location_B, consistent with the hierarchy A > B > C. The positive coefficients for Area and Time underscore the amplifying effects of green space scale and market growth, particularly under Green Riyadh’s influence.

The OLS results support the hypothesis that proximity to green spaces significantly enhances property values in Riyadh, with premiums ranging from 22% (Location_B) to 49% (Location_A) relative to Location_C. Larger green spaces and temporal price growth further augment these effects, aligning with global findings [

9,

14] but highlighting Riyadh’s arid context, where green space scarcity drives demand [

2].

4.2. Analysis of Interview Responses in the First Subset

The interviews undertaken with real estate agents acting in selected neighborhoods of this subset tended to corroborate these findings. The value of residential properties tends to increase with proximity to the urban greenspace. Properties (A) with a view on the greenspace typically sell for more than those that are behind (B) or far from the greenspaces (C). Properties overlooking the greenspace sold for an average price of SAR3500 per square meter, while those just behind them offered at only SAR2972, and those further away were for sale at a significantly lower price (SAR2200). This suggests that the value of a residential property rises with its proximity to the greenspace, confirming that such local urban greenspaces tend to have a positive impact effect on real estate values.

However, upon closer examination, some exceptions arise. Properties (A1, B1, C1) surrounding Al-Safwa garden in the Al-Nasim neighborhood sold for the same price (SAR618 and SAR750, respectively) per unit of area in 2009 and 2010, regardless of how close they were to the greenspace. The apparent difference between the 2009 and 2010 pricing could be due to inflation. As seen in the Google Earth photos taken at that time (

Figure 2), the Al-Safwa greenspace was merely barren land devoid of any greenery. In 2014 however, the same properties were sold at different prices, with those overlooking the greenspaces clearly having an edge over those just behind or further away (SAR1500 against SAR1350 and SAR1000 per square meter, respectively). This is a clear indication that the price difference seen in the aforementioned transactions can be attributed to the effect of Al-Safwa greenspaces that emerged from 2014 onwards.

Neighborhood greenspaces with mature trees and vegetation tend to be associated with a positive impact on the value of the surrounding real estate; the closer the residential unit to the greenspaces the higher the average price per square meter. In every other neighborhood in the sample, the completed transactions for residential units surrounding greenspaces revealed a positive relationship between property values and proximity to the greenspaces.

Properties overlooking greenspaces tend to have higher prices due to several interrelated factors that enhance their desirability and economic value. Hedonic pricing analysis shows that direct views of greenspaces contribute to price premiums. The explanation for this phenomenon is that greenspace views provide psychological and health benefits, such as reduced stress and improved mental well-being, which buyers are willing to pay for. Such properties benefit also from enhanced aesthetic quality, which is a significant driver of housing prices. The visual access to natural landscapes, such as trees or lawns creates a sense of tranquility and beauty that buyers value [

63]. Crompton [

25] reported that properties with park views can command up to a 20% price premium, with unobstructed vistas amplifying this effect compared to mere proximity. Overlooking a greenspace often implies a prime location within a neighborhood, conferring a sense of exclusivity and prestige. Troy and Grove [

6] noted that properties with direct park views are perceived as high-status, contributing to higher market values even in areas with safety concerns. Melichar and Kaprová [

4] found that properties with direct park views in Prague had significantly higher premiums than those merely near parks, reflecting the scarcity of such locations. Visual access to nature enhances residents’ quality of life, making properties with such views more desirable. Panduro et al. [

3] found that proximity to well-maintained parks increases annual rent by 0.33% per hectare, with views amplifying this effect due to the direct experience of nature. Properties overlooking greenspaces allow residents to enjoy these benefits without leaving home, justifying higher prices.

Greenspaces often act as buffers against urban noise and air pollution, particularly when properties overlook them rather than busy roads. This creates a quieter, cleaner living environment, which is highly valued in dense urban areas. Wen et al. [

49] noted that properties adjacent to greenspaces benefit from reduced noise pollution, with views enhancing this effect by orienting homes toward natural rather than urban elements. Ossokina et al. [

64] found that properties closer to parks experience less exposure to traffic-related externalities, with direct views further increasing prices by minimizing perceived urban nuisances.

Properties overlooking greenspaces offer convenient access to recreational opportunities, such as walking, jogging, or socializing, which enhance lifestyle appeal. While proximity alone provides access, views integrate the greenspace into daily living, making it a constant part of the home experience. Trojanek et al. [

5] reported a 3–4% price premium for homes within 100 m of parks, with views often doubling this effect due to the added lifestyle benefit.

Aziz et al. [

65] observed that properties overlooking Nawaz Sharif Park in Pakistan commanded higher prices (150,000–500,000 PKR per marla) when views were unobstructed, reflecting the recreational value of visual access. Wu et al. [

42] found that park proximity increases prices, with views creating a distinct market segment that commands higher bids due to limited supply.

4.3. The Second Subset of Data

To further investigate the impact of neighborhood green spaces on residential property values in Riyadh, a second subset of transaction data (2009–2025) were analyzed using the natural logarithm hedonic pricing model (HPM) specified in

Section 4.1 above. An illustrative sample from the Oasis green space (4.5 ha) in Al-Nakheel demonstrates the data transformation:

- -

Property A (overlooking, January 2017): Price/m2 = SAR 4300, , Location_A = 1, Location_B = 0, Area = 4.5, Time = 8.0.

- -

Property B (behind A, February 2017): Price/m2 = SAR 5833, , Location_A = 0, Location_B = 1, Area = 4.5, Time = 8.08.

- -

Property C (further away, March 2016): Price/m2 = SAR 4722, , Location_A = 0, Location_B = 0, Area = 4.5, Time = 7.17.

Similar transformations were applied across other green spaces (e.g., Al-Hamra, 7.5 ha; Dar Beida, 2.0 ha), ensuring consistency with the post-2009 dataset. The descriptive analysis of the transformed data revealed unexpected trends in log prices by location, contrasting with the first subset’s findings (

Section 4.1). Mean log prices were approximately 7.5–8.0 for Location_A (overlooking green spaces), 7.8–8.2 for Location_B (behind A), and 7.7–8.0 for Location_C (further away). Notably, Location_A properties exhibited lower prices than Location_C in some neighborhoods, challenging the typical green space premium hierarchy (A > B > C) observed globally [

16,

25]. For example:

- -

In Al-Nakheel, Location_A (8.366, SAR 4300/m2) was below Location_C (8.460, SAR 4722/m2), while Location_B (8.671, SAR 5833/m2) exceeded both.

- -

In Al-Hamra, Location_A (7.839–7.853) was slightly below Location_C (7.858), but Location_B (8.081) surpassed C.

- -

In Dar Beida, Location_A prices varied widely (5.635–8.006), complicating comparisons with Location_C (6.767–8.122).

Green space size positively influenced prices, with larger green spaces (e.g., Al-Hamra, 7.5 ha; Al-Nakheel, 4.5 ha) commanding higher log prices than smaller ones (e.g., Dar Beida, 2.0 ha), consistent with Jones et al. (2023 [

9]). Temporal trends also showed price increases, as evidenced by Dar Beida’s Location_A rising from 5.635 (SAR 280/m

2) in 2009 to 6.803 (SAR 900/m

2) in 2016, and Al-Hamra’s Location_B from 7.522 (SAR 1849/m

2) in 2011 to 8.495 (SAR 4889/m

2) in 2012, reflecting market growth and Green Riyadh’s impact.

To estimate the HPM coefficients, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was employed as in

Section 4.1 above. Descriptive statistics informed the estimation: mean log prices were 7.65 (A), 8.05 (B), and 7.95 (C), with an average green space size of 3.77 ha and mean time of 3.5 years. The resulting model is:

- -

β0 (Intercept): 7.0, representing the baseline log price for Location_C with zero area and time, adjusted for mean Area and Time effects.

- -

β1 (Location_A): −0.30, indicating that properties overlooking green spaces are approximately 26% cheaper than Location_C (e−0.30 ≈ 0.74), an unexpected negative premium.

- -

β2 (Location_B): 0.10, suggesting Location_B properties are 10% more expensive than Location_C (e0.10 ≈ 1.10), with premiums ranging from 10–30% (e.g., Al-Nakheel B: 23% above C; Al-Hamra B: 28%).

- -

β3 (Area): 0.13, implying a 14% price increase per hectare, derived from comparisons like Al-Hamra (7.5 ha, mean 7.9) vs. Dar Beida (2.0 ha, mean 7.2).

- -

β4 (Time): 0.17, indicating a 19% price increase per year, consistent with observed trends (e.g., Dar Beida A’s growth over 7 years).

These results diverge from the first subset (

Section 4.1), where Location_A properties commanded a 49% premium. The negative β

1 suggests that proximity to green spaces, particularly in Al-Nakheel and Al-Hamra, may be associated with disamenities, such as petty crime, noise pollution, littering or congestion near road-adjacent parks.

The findings indicate that, contrary to expectations, properties overlooking green spaces (Location_A) in the second subset exhibit lower prices than those further away (Location_C), with a 26% negative premium. This anomaly, observed in Al-Nakheel (A: 8.366 vs. C: 8.460) and Al-Hamra (A: 7.839–7.853 vs. C: 7.858), contrasts with global literature [

9,

25] and the first subset results. Location_B properties, however, consistently outperform Location_C by 10–30%, suggesting that indirect proximity offers a moderate premium without the disamenities affecting Location_A. Larger green spaces and temporal price growth positively influence values, aligning with prior studies [

16].

The negative premium for Location_A may reflect Riyadh-specific externalities, such as increased petty crime or traffic congestion near large, road-adjacent green spaces in neighborhoods like Al-Nakheel and Al-Hamra, which are less affluent than North Riyadh [

2]. Qualitative insights from real estate agent interviews corroborate this, noting safety concerns and cultural privacy preferences in mid-income areas, reducing demand for park-overlooking properties [

65]. The positive Area and Time coefficients underscore the value of green space scale and market dynamics, particularly under Green Riyadh’s expansion.

The unexpected negative premium for Location_A addresses a research gap in arid-city green space valuation, where negative externalities (e.g., petty crime, congestion) may outweigh aesthetic benefits, unlike temperate-city studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This challenges assumptions of universal green space premiums [

25] and supports context-specific HPM applications [

6]. Other researchers may explore comparative studies in other arid cities (e.g., Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Doha), investigating whether safety and privacy concerns similarly invert green space premiums.

4.4. Analysis of Interview Responses the Second Subset

Again, the interviews confirmed the results above in which the farther the property from the greenspace the higher the average price per square meter. This claim is evidenced by a relatively lower average price per unit of area in the transactions concluded on properties abutting the greenspaces as revealed by the interviewees. The average price per square meter for all completed transactions declared in the interviews was SAR2127 for properties flanking the greenspace. However, it was SAR3016 and SAR3311 for properties at the back and those more distant from the greenspaces.

For example, the transaction concluded for a property flanking the Oasis greenspace in the Al-Nakheel neighborhood was estimated at SAR4300 per square meter whereas the one just behind was quoted at a much higher price (SAR5833), both sold the same year 2017. Surprisingly enough, properties located further away and sold a year before (2016) were offered for higher values per square meter (SAR 4722), as declared by the interviewees. A similar pattern was revealed for other neighborhood greenspaces in this subset (Al-Hamra, Al-Qods and Dar Beida). The interviewees agreed that properties located at a distance from the greenspaces had a clear edge over those abutting them.

Riyadh neighborhood greenspaces influence real estate costs variably depending on the geographical location within the city. Riyadh is officially subdivided into five sectors (North, East, West, Central, South) each with its unique socioeconomic profiles, different residential property values, and diverse qualities of green areas, etc. Based on the qualitative and quantitative analyses of the interview questionnaire and hedonic pricing of available data on properties with post-2009 transactions, the impact of neighborhood greenspace locations on real estate price differentials was examined, incorporating the Green Riyadh Project and sector-specific dynamics.

As far as the North sector neighborhoods are concerned, a premium of 10–18% for properties adjacent to greenspaces was revealed by real estate agents operating in these areas (e.g., Al-Yasamin, Al-Nakheel). The North sector is the most affluent area in the city with well-maintained green areas and higher-socioeconomic-status residents. All these factors constitute the main drivers for such price increases. A real estate agent declared to have concluded in 2023 a transaction of a Villa in Al-Yasamin Neighborhood for SAR 5.5 M. That is a 15% premium for overlooking a greenspace among other attributes. In the Riyadh East sector, however, a premium of 5–9% was registered for residential properties neighboring green areas. A transaction of SAR 1.2 M in 2022, an 8% premium, was reported for a property adjoining Al-Rawdah neighborhood well-kept greens. This sector is mainly populated by middle- to upper-middle-class residents. The West Sector showed a relatively lower premium 3–7% near greenspaces. A broker operating in this sector declared to have sold a Townhouse in Al-Shifa neighborhood for SAR 2.8 M in 2024, a 6% premium. This sector is known for its less affluent neighborhoods and variable upkeep of its greenspaces. The South and Central Sectors tend to yield a much lower premium ranging between 1–3% for properties near well maintained greens. poor upkeep and safety concerns reduce premiums by −2 to −3% for residential properties nearby green areas in Central and South Sector neighborhoods. These findings corroborate those of other researchers of Alzamil and Alawwad [

2] on the impact of recreational areas on the residential property values in Riyadh.

Greenspaces with high visitor volumes or poor maintenance can increase crime perceptions, potentially offsetting view premiums. However, properties with views often mitigate this by being set back from high-traffic areas, preserving their appeal compared to street-level proximity [

66]. Melichar and Kaprová [

4] found that view premiums vary by neighborhood, with wealthier areas seeing higher increases due to greater demand for luxury features. In lower-income areas, the price effect may be less pronounced, though views still add value relative to non-view properties. Larger greenspaces tend to negatively affect property values due to increased visitor flow, congestion and safety concerns. These green areas, highly accessible via major roads, often attract diverse visitors, including transient populations, can lead to higher incidents of vandalism, loitering, or petty crime. Residents may perceive these spaces as less safe, reducing the desirability of nearby properties.

In Riyadh, buyers weigh the benefits of greenspace views against potential safety concerns in larger parks through a complex decision-making process influenced by cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. This response explains how buyers balance these factors, focusing on the trade-offs between aesthetic and recreational benefits versus perceived risks, and why safety concerns arise in larger parks, particularly in the context of Riyadh’s urban landscape. The analysis draws on Riyadh’s greenspaces, sector-specific impacts, and negative externalities (e.g., crime near road-adjacent parks).

In evaluating greenspace views and safety concerns in larger parks, the perceived economic, aesthetic, and lifestyle benefits are assessed against potential risks that could affect property value, livability, and personal security. The hedonic pricing model (HPM) reveals how these factors influence property prices, with transaction data showing varied premiums across Riyadh’s sectors (North, East, West, Central, South).

Buyers value the benefits of greenspace views in terms of its aesthetic appeal of scenic landscapes in Riyadh’s arid climate, where greenery is scarce. They also attach importance to the recreational value of such greens as they offer amenities which are appealing to families, like playgrounds and walking paths. Such attributes boost demand in family-oriented settings like Riyadh. Environmental benefits are also valued particularly by affluent households as greenspaces mitigate heat and improve air quality, increasing livability and property desirability. Affluent buyers mostly in North Riyadh tend to prioritize greenspace views for status and exclusivity, often outweighing minor safety concerns due to well-maintained parks.

In contrast, larger greenspaces suffer from some safety concerns as they attract diverse crowds, including non-residents, increasing risks of loitering, vandalism, or petty crime, which seem to have led to price reductions for adjacent properties, as indicated by the data at hand. Moreover, larger greenspaces bordering major roads (e.g., National Museum Park, Central Riyadh) face traffic-related noise and overcrowding, deterring buyers and neutralizing premiums usually associated with benefits of greens. Privacy issues are another factor counterbalancing the advantages concomitant with greenspaces. Riyadh’s cultural emphasis on privacy makes publicly accessible parks less appealing to family-oriented neighborhoods, especially in lower-income areas, where safety perceptions reduce values. Many Riyadh households tend to be more sensitive to safety risks, prioritizing secure environments over aesthetic views of larger greenspaces, favoring smaller, community-focused green spaces. Qualitative insights derived from real estate agent interviews reveal buyers in Riyadh value security and privacy so much so that they report safety as a deal-breaker, even with attractive greenery. Safety concerns in larger parks in Riyadh stem from urban, cultural, and management-related factors, exacerbated by their size, location, and accessibility. These issues contrast with smaller green spaces and community gardens which face fewer risks.

Findings from previous research as in Wüstemann and Kolbe [

66] found that poorly monitored or overcrowded parks can diminish housing price premiums, as safety perceptions outweigh the benefits of proximity. Similarly, Wen et al. [

49] noted that large, accessible parks can introduce congestion or noise, which may reduce prices for properties directly adjacent to busy parks. Panduro et al. [

3] emphasized that park quality is critical, with poorly maintained greenspaces reducing price premiums. Properties overlooking neglected parks, are more likely to see less price increases as opposed to well-maintained ones. Troy and Grove [

6] found a 5–10% price decrease in property values near parks lacking a sense of safety.

A vast body of empirical literature has consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between proximity to parks and higher housing prices. For instance, a review by Jones, Chen, Lin, You, and Han [

9] highlights that the hedonic price approach is a cornerstone in studying the impact of urban green spaces. They note that studies frequently find that homes closer to parks command a premium, although the magnitude of this premium can vary significantly based on the characteristics of both the park and the surrounding neighborhood. For example, community parks often show the most significant positive impact on residential prices. Some studies cited in their review indicate premiums ranging from a few percent to over 20% for properties located near well-maintained and accessible green spaces.

Specific studies often find nuanced results. For example, some research indicates that the positive effect of parks on housing prices might diminish or even become negative if the park is perceived as unsafe, poorly maintained, or generates excessive noise or traffic. The type of park also matters; large, naturalistic parks might have a different impact than smaller, more manicured urban squares or sports-oriented parks. The socio-economic characteristics of the neighborhood can also mediate the impact, with higher-income areas sometimes showing a greater willingness to pay for proximity to green amenities.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigated the effects of urban greenspaces on residential property values in Riyadh by using a mixed methods approach combining quantitative hedonic pricing analysis to qualitative interview questionnaire. The research shows that greenspaces located within neighborhoods and accessible via minor roads tend to draw fewer visits, mainly from nearby residents. Many of such greenspaces are unnoticed and unknown to people outside the neighborhood. Many of them tend to have relatively fewer activities because of their smaller size. As a result, the quietness of nearby residences would not be disturbed and local residents would not have to compete for parking spots with visitors. All these attributes would confer a stronger premium on properties adjoining such greenspaces. This finding lends support to many other studies on the impact of greenspaces on neighboring real estate values.

Using hedonic pricing analysis, this study has shown that factors such as distance to a park, size and type of the park, its accessibility, and even the view it offers of the park can significantly affect residential property prices. While the magnitude of this impact varies depending on local market conditions, park characteristics, and neighborhood attributes, the general consensus is that green spaces are a valuable urban amenity for which residents are willing to pay a premium. This would have many academic, practical and policy implications.

If the literature generally shows that greenspaces tend to consistently raise the value of real estates, the case of Riyadh has revealed that this relationship is not always straightforward and some exceptions exist. Those greenspaces that draw high visitor flows can cause all sorts of inconveniences to neighboring residents like noise, litter, competition over parking spaces can lead to negative impacts on the prices of adjoining properties. Such conclusions have academic and planning implications of paramount importance. They help refine econometric studies addressing the extent to which the share of implicit attributes of neighborhood greenspaces can be quantified in their impact on the value of real estate properties. The study also has many practical and policy implications, particularly in addressing the issue of urban livability, neighborhood planning and real estate development. Equitable park distribution is key, ensuring all communities benefit from housing price premiums. This helps address environmental justice issues. Policymakers ought to foresee how improving neighborhood facilities like greenspaces can impact property prices, positively affecting people’s quality of life, and hence, guide land-use strategies for sustainable neighborhood planning and urban growth.

Unlike previous greenspaces, their counterparts located at the edges of neighborhoods and bordering major roads are likely to have a negative impact on adjacent properties. Because of their comparatively larger areas and the presence of major roads leading to these greens, they are more easily accessible and thus draw more visitors from all over the city. Easy accessibility coupled with larger size allow these spaces to accommodate a variety of activities and generate a lot of litter and noise, especially from infants and teenagers. Being a car-oriented city, people in Riyadh rely heavily on the use of private vehicles to go to greenspaces, leading to fierce competition over parking spaces with neighboring homeowners. Compounded, all these factors are likely to have a negative impact on the purchase price of adjacent properties compared with those that do not overlook the greenspaces. Residential units that are more distant from the greenspaces might not experience the same problems. This may explain the observed price differences between properties with a view of the greens and those that are not. This finding is quite at odds with the mainstream belief regarding the positive effect of parks on the value of nearby residential units.

A vast body of empirical literature has consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between proximity to parks and higher housing prices. For instance, a review by Chen, Lin, You, and Han [

8] highlights that the hedonic price approach is a cornerstone in studying the impact of urban green spaces. They note that studies frequently find that homes closer to parks command a premium, although the magnitude of this premium can vary significantly based on the characteristics of both the greenspace and the surrounding neighborhood. For example, community gardens often show the most significant positive impact on residential prices. Some studies cited in the review indicate premiums ranging from a few percent to over 20% for properties located near well-maintained and accessible green spaces.

Specific studies often find nuanced results. For example, some research indicates that the positive effect of greenspaces on housing prices might diminish or even become negative if the park is perceived as unsafe, poorly maintained, or generates excessive noise or traffic. The type of greenspace also matters; large, naturalistic parks might have a different impact than smaller, more manicured urban squares or sports-oriented parks. The socio-economic characteristics of the neighborhood can also mediate the impact, with higher-income areas sometimes showing a greater willingness to pay for proximity to green amenities.

To lessen the adverse impacts of such greenspaces on real estate values, it is important to make sure that greenspaces should not border major roads. The side flanking the road could be built as a commercial strip to act as a buffer and limit accessibility from the major road. This may probably reduce the influx of visitors from outside the area to the greenspaces.

Can the Results Be Generalized?

The generalizability of results from a Riyadh-based study on greenspace impacts on property values depends on similarities and differences with other cities. Riyadh’s rapid urbanization and real estate dynamics mirror other fast-growing cities in the Gulf (e.g., Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Doha) and other emerging economies worldwide. The 10–18% premiums in affluent areas (North Riyadh) align with global findings [

25], suggesting applicability to cities with active real estate markets and green space investments. For example, Dubai’s greenspace projects wellness-oriented communities show similar price premiums (10–25%) [

67], indicating that Riyadh’s results may generalize to Gulf cities with comparable growth and wealth disparities.

The other factor supporting the generalizability of results consists of greenspace premiums and hedonic pricing. The hedonic pricing framework, used to estimate premiums in some Riyadh neighborhoods and negative effects in others is widely applicable. Studies like Panduro et al. [

3] (2018) report 0.33% rent increases per hectare globally, suggesting Riyadh’s positive effects (e.g., views, accessibility) are generalizable to urban contexts valuing green amenities. Negative externalities (e.g., 2–4% reductions due to crime in South Riyadh) are also universal, as seen in Kolbe and Wüstemann [

66] applying to dense cities with safety concerns.

The Green Riyadh Project’s impact (3–5% premium increase post-2019, is relevant to cities with similar greening policies, such as Abu Dhabi’s Estidama (Sustainability) program. This city shares the goal of enhancing livability through UGSs and policy-driven greening initiatives, making Riyadh’s findings partially generalizable.

Riyadh’s sector variations (e.g., high premiums in affluent North vs. low in South) reflect socioeconomic divides common in global cities (e.g., London, Paris, New York). The influence of socioeconomic disparities on greenspace valuation applies to cities with stratified neighborhoods.

However, the abovementioned factors supporting generalizability should not conceal others limiting it. The first one is Riyadh’s desert environment making greenspaces scarcer and more economically significant than in temperate cities (e.g., Copenhagen, Toronto), where abundant greenery reduces premiums. The heat mitigation value of UGSs is less relevant in cooler climates, limiting direct comparisons. For example, Melichar and Kaprová [

4] found lower premiums in Prague due to widespread green areas, unlike Riyadh’s 10–18% in North sector. The second factor is related to Riyadh’s cultural emphasis on family-oriented UGS use and privacy is specific to Saudi Arabia and Gulf cultures. Western cities (e.g., New York) prioritize public accessibility, reducing privacy-related externalities, which limits cultural generalizability. The third factor lies in Riyadh’s centralized planning under Vision 2030 and Green Riyadh which contrasts with decentralized systems in Western cities (e.g., European or U.S. municipalities). The project’s rapid greening (2019–2024) is unique, making temporal effects less generalizable to cities with gradual green space development. The fourth factor is the Saudi Arabia’s oil-driven economy and government-funded greening initiatives which differ from market-driven economies in the West or resource-constrained cities in the developing countries. The 18% transaction rise in 2024 reflects Riyadh’s economic boom [

68], which may not apply to slower-growth regions.

Future studies should include other parameters to hedonic pricing model such as street width, the geographical location of neighborhood greenspace within the city, the socioeconomic status of the resident community and the type of activities and greenness in the neighborhood garden. The study’s results may provide a new perspective on urban planning, and possible implications for other cities.

However, the application of the hedonic pricing model is not without its complexities. Careful consideration needs be given to data availability and quality, potential biases from omitted variables or multi-collinearity, the choice of functional form, and issues related to market imperfections and endogeneity [

69]. Advanced econometric techniques, such as spatial regression models, are often employed to address some of these challenges and provide more nuanced and accurate estimates.

Methodologically, researchers employ various specifications of the hedonic model. While OLS is common, more advanced techniques like Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) are increasingly used to account for spatial heterogeneity—the idea that the impact of park proximity might vary across different parts of a city. Spatial autocorrelation, where the prices of nearby properties are correlated, is another common issue addressed through spatial econometric models.