1. Introduction

Ancient architectural cultural heritage—monuments, vernacular architecture, and archeological landscapes—represents an irreplaceable repository of cultural memory, identity, and aesthetic achievement [

1]. However, these architectural heritage sites are facing increasing threats from climate change, over-tourism, armed conflict, and rapid urban renewal [

2]. Nowadays, digital technologies can document fragile sites at risk of disappearing, as well as re-present heritage to new audiences through immersive narratives and interactive media [

3]. Digital innovations within cultural heritage offer opportunities to interpret and engage with culture, not merely as a static image of the past, but as a dynamic and continually evolving component of societal development and collective well-being [

4]. Tourist demand for architectural heritage tourism has grown steadily, driven by international promotional campaigns, heritage list designations, and the rise of cultural routes linking multiple heritage sites.

Role-playing games (RPGs) are interactive experiences where participants construct imaginary worlds, investigate different identities, address various challenges, and form social connections [

5]. Since the recognition of cultural presence takes time to reflect upon, a large number of architectural cultural heritage settings are applied in RPGs that do not rely exclusively on time-based challenges. The spread of RPGs set in ancient architectural cultural heritage contexts is growing exponentially, digitally reconstructing the historical context, allowing visitors to explore the reconstruction of lost or damaged sites, and providing narrative layers that deepen understanding [

6]. In this game genre, human players take on the characteristics of certain people or creature types [

7], exploring large-scale open environments and interacting with the numerous NPCs contained therein [

8]. They facilitate highly experiential encounters with cultural content, thus enabling the acquisition of procedural knowledge related to cultural domains [

9].

As an approach to virtual heritage, digitally innovative RPG products aim not merely to depict the visual aspects of cultural artifacts but also to communicate their deeper meanings, significance, and the societal contexts influencing their creation and utilization [

10]. The use of RPGs for the historical contextualization of ancient architecture has become progressively more common [

11]. Nowadays, RPGs related to the historical context of ancient architecture have become an independent field of study, even utilizing trans-media narratives, producing sagas, novels, comics, short and feature films, and developing the phenomenon of gamertourism (defined as the exploration of physical locations where players interact within the game) [

12]. Minecraft, a widely popular open-world multiplayer game, allows users to explore digitized art galleries and rebuild historically significant sites in virtual form. These endeavors include recreating the City of London that was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1666, as well as the Temple of Bel in Palmyra which now lies in ruins [

12].

The game Black Myth: Wukong, for example, demonstrates how pop culture and RPGs merged with ancient mythological themes to revitalize interest in the ancient architectural cultural heritage of Shanxi, China [

13]. The series draws on the story of Wukong from Chinese literature, utilizing beautiful digitized ancient Shanxi architecture and game mechanics to engage the audience. It exemplifies how mythological or historical stories and visual representations of ancient architectural and cultural sites can be reimagined in a modern digital form. Cross-media narrative research has shown that when entertainment venues focus on heritage elements they can inspire curiosity and drive tourism demand [

14]. From this perspective, Black Myth: Wukong can be a powerful incentive to attract visitors to the site, especially when Shanxi’s ancient architectural heritage is combined with complementary digital content or themed events. By connecting the world of RPGs with physical architectural heritage sites, tourists can gain a deeper understanding of the historical and cultural contexts that inspire narratives [

15]. This synergy represents the ways in which cultural heritage tourism can utilize digital culture to enhance the interpretive value and sustainability of heritage destinations.

Most cultural heritage tourism communication channels, including blogs [

16], destination websites [

17], social media campaigns [

18], and virtual reality [

19], share a common limitation: they usually present static or curator-driven narratives. In contrast, role-playing games (RPGs) place visitors at the center of narrative constructs, enabling them to autonomously explore identities and engage in procedural learning in historically charged worlds. Recent research suggests that such narrative agency enhances attachments to place and pro-preservation attitudes [

20], but empirical evidence remains fragmented. There are few studies that analyze commercial, story-driven RPGs depicting ancient buildings or explain how specific design stimuli translate into visitor behavior and willingness to conserve.

The RPGs explored in this study are experiential perceptions of simulated ancient architectural cultural heritage in a gaming context. This study focuses on the dissemination of RPGs aimed at promoting users’ willingness to travel to ancient architectural cultural heritage sites in the game context and the sustainable development of the ancient architectural cultural heritage itself. The first objective of this study is to investigate the influencing factors of RPGs related to users’ perception of ancient architecture on through stimulus–organism–response (SOR) modeling. Then, RPGs, as interactive heritage media, can segregate emotion as a key mediator between cognition and intentionality. Finally, validated scales of immersion, storytelling, and cognitive engagement are combined with heritage-specific travel and conservation metrics to provide design principles for game studios, ancient architecture tourism marketers, and heritage managers seeking to utilize digital narratives to achieve sustainable tourism and conservation goals.

2. Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Theory and Key Constructs

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model

The stimulus–organism–response (SOR) framework was originally proposed by the environmental psychologists Mehrabian and Russell [

21]. The model has been widely used in tourism research to explain how environmental cues or experiences influence visitors’ attitudes and intentions. In the field of cultural heritage, recent studies have utilized SOR-based models to examine users’ perceptions and conservation behaviors. For example, Jiang et al. [

22] extend the SOR model to the continuance intention of intangible cultural heritage VR games. Similarly, Bai et al. [

23] apply the SOR framework to explore the impact of serious games on intangible cultural heritage. Despite these advances, a critical gap remains: no previous research on RPG-related ancient heritage tourism has explicitly used the SOR framework for empirical modeling.

The cultural heritage sector is entering the digital heritage era based on advanced digital technologies, which have become a new medium to enhance the user experience through the enhancement of additional information or content [

24]. Previous research on game-based heritage interpretation has tended to be descriptive or use theories of technological acceptance and motivation, leaving room for the application of a systemic perspective of SOR. RPGs associated with ancient architectural cultural heritage are cultural performances that embody the construction of meaning, which is socially and politically rooted but personally experienced [

25]. Existing research considers both video games and visits to ancient architectural sites to be user-centered design experiences [

25], and thus, situating this study within the SOR paradigm contributes a novel theoretical approach to exploring how RPGs evoke affective engagement and drive tourism and conservation outcomes.

The SOR theory model suggests that external stimuli (Ss) shape an organism’s internal cognitive–emotional state (O), which in turn leads to either convergent or avoidant responses [

26]. When applying SOR to ancient architectural heritage, a stimulus (S) can be defined as an external factor that influences the user’s behavioral intentions, and is an influential factor in the dissemination of ancient architectural heritage based on RPGs. The organism (O) is the internal emotional state of a tourist [

27]. Response (R) refers to a tourist’s perception of behavioral intentions as well as broader sustainability outcomes (including the local economy, environment, and cultural preservation), which includes the behaviors that emerge as a result of changes in users’ cognition and emotions due to internal and external stimuli, which emerge from the interaction between stimulus and organism [

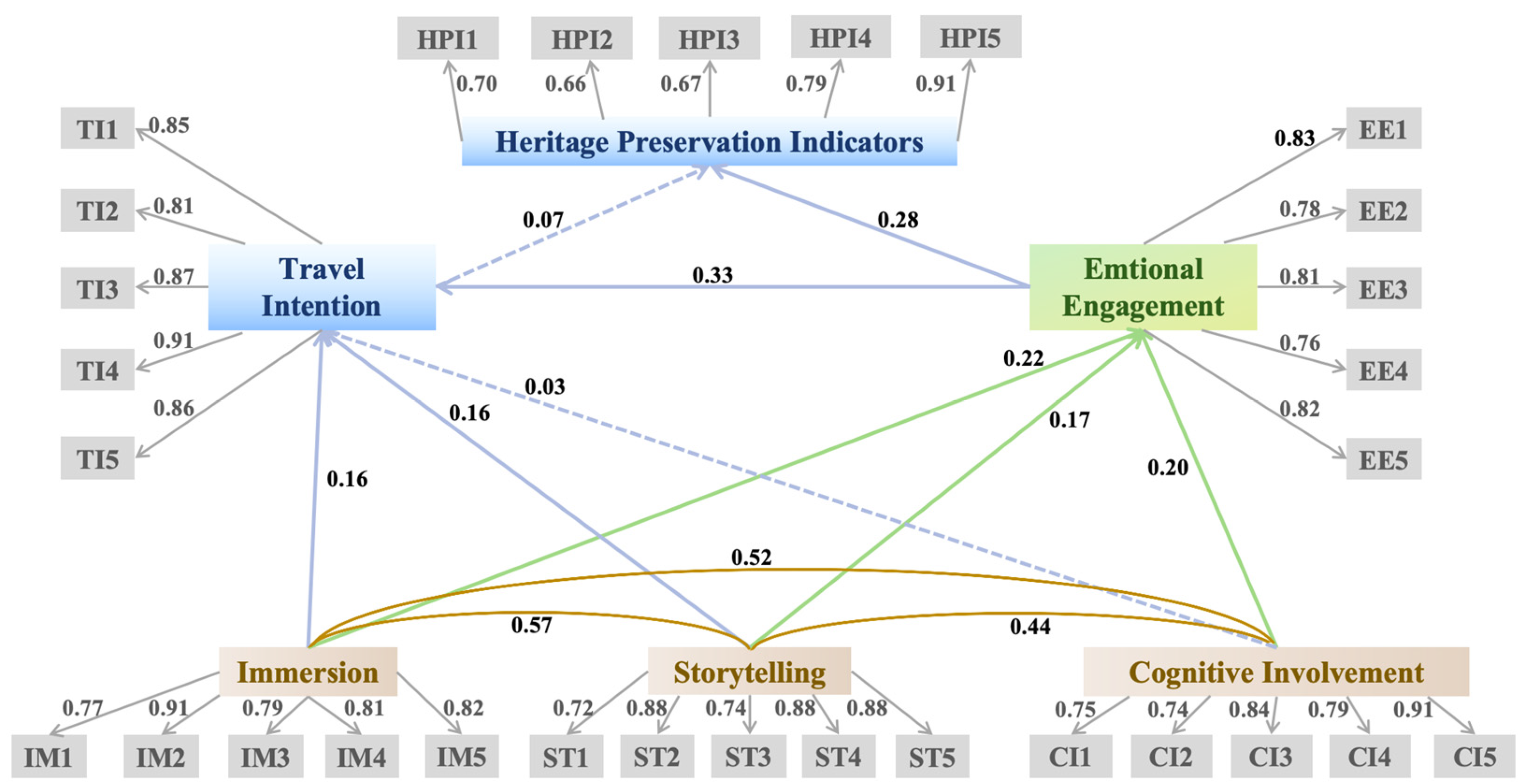

23]. Consequently, considering the theoretical background discussed and the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) framework, this study proposes the conceptual model depicted in

Figure 1 to examine how digital innovations in ancient architectural heritage influence sustainable tourism development.

From a practical perspective, measuring the organism dimension may involve tracking the emotional and affective engagement of visitors. Research markers emphasize the mediating role of emotional responses in translating external stimuli into behavioral outcomes. Conversely, if the technique is perceived as intrusive, it may trigger negative impacts and weaken the willingness to recommend or revisit. The SOR model can be extended to tourism sustainability by recognizing that “responsive” outcomes are not limited to individual behaviors, but can also have a collective impact. When coupled with deeper engagement, such pro-sustainability responses can foster tourists’ sense of ownership and responsibility. Moreover, RPG dissemination can reduce the environmental load on fragile ancient architectural sites by offering partial virtual experiences, effectively diverting some visitors away from architecturally vulnerable areas. This approach to visitor management meets environmental sustainability objectives while also creating new revenue streams through paid on-site digital experiences.

2.2. Key Structures of Stimulus

According to the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model, stimuli can encompass both object-based elements and psychosocial factors [

28]. In this study, stimuli include immersion, storytelling, and cognitive involvement.

Immersion in digital-heritage-related RPGs refers to the player’s deep involvement and sense of presence in a virtual historical environment [

29]. This is due to the ability of RPGs to situate historical architectural heritage in a contemporary context [

30], influencing both physical and emotional engagement with the game world [

31,

32]. For instance, Brown and Cairns [

33] identify three levels of immersion—engagement, total attention, and total immersion—that players can achieve by overcoming a range of barriers to participation. Similarly, Ermi and Mäyrä [

34] distinguish between the sensory, challenging, and imaginative dimensions of immersion, emphasizing how audiovisual richness, gameplay challenges, and narrative imagination can work together to engage players. Game design also emphasizes that creating immersive game worlds is critical to player engagement [

35]. On this basis, Calleja [

36] explains how deep immersion integrates players into the virtual world of a game by combining spatial, narrative, emotional, and other dimensions.

In cultural-heritage-themed RPGs, this deep immersion can help players feel more connected to the architectural narrative, thus effectively bridging the gap between users and cultural content [

36]. Notably, support for the interpretation of virtual heritage sites promotes personal engagement and the construction of virtual emotional assets [

37], which promotes a stronger sense of “immersion” (presence) [

38]. Moreover, immersive experiences are often influenced by the social context: interactions with other players and shared imaginary play can enhance immersion [

39,

40]. Famous or historic sites are particularly likely to benefit from immersive game design, as the player’s pre-existing interest in iconic locations can enhance narrative and spatial immersion [

41]. As a result, immersive RPG experiences are increasingly being used as interactive tools in heritage tourism to project a positive destination image and attract people to real-world sites [

42]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1a. Immersion positively influences travel intention.

In role-playing games, storytelling is recognized as a persuasive strategy [

43], effectively shaping users’ behaviors [

44] and successfully drawing in visitors [

45]. Research in tourism has particularly highlighted the importance of location-based gaming experiences in influencing tourist decisions [

46]. Storytelling provides a clear temporal and spatial location for storytelling to take place. Storytelling influences the way players think about the world and helps cultures reflect on how to present the historical evolution of ancient architecture [

47]. By providing immersive storytelling, personalized itineraries, and interactive educational content, these innovations cater to visitors’ desire for authenticity and novelty. High production values and historical accuracy can enhance perceived authenticity; they act as vehicles for interpretation and education, making heritage more accessible and appealing to different audiences. Simultaneously, storytelling encourages visitors to engage deeply, including interactions on emotional and cognitive levels [

48]. User-generated content related to RPGs, for example, can expand player engagement. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2a. Storytelling positively influences travel intention.

The dissemination of cultural heritage is related to the awareness of the values embedded in cultural heritage [

49]. Woosnam et al. [

50] demonstrated a positive relationship between cognitive and affective destination images, specifically in the context of repeated visitation behaviors. RPGs do not allow people to physically engage with the material entities of cultural heritage, but they do allow people to interact with their representations through perceptual (audiovisual) contact and gaming interactions [

10], thus allowing people to engage with cultural heritage content through cognitive and social engagement. On the other hand, by encouraging deeper thinking about historical context, interactive technologies can lead to a more meaningful experience for visitors and a more positive attitude toward preservation. Specifically, digitally enhanced experiences can increase visitor engagement, learning outcomes, and intent to revisit. For instance, research has shown that current teaching during guided tours of monuments is faced with the fact that external disturbances during physical tours can reduce the learning effectiveness, and that related role-playing teaching games can keep learners quite engaged during the game and even maintain their interest in the monument after the activity is over [

51]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3a. Cognitive involvement positively influences travel intention.

2.3. Key Structures of Organism (Mediating Variables)

The organism in SOR theory represents a person’s cognitive and affective internal state [

28]. Gartner [

52] proposed the hierarchical relationship between cognitive, affective, and intentional images of tourism. Additionally, Lee and Jan [

53] provided evidence that affective images have a positive association with intentional images. Emotional engagement is the degree of empathy, excitement, or emotional engagement felt by the user—an organismic state that is particularly important in the context of heritage games. Heritage tourism experiences can have strong emotional resonance. Positive emotions have been shown to enhance memory and fulfillment [

54], which are crucial for ancient buildings that aim to leave a lasting impact. Emotional images sometimes provoke the initial response to a destination, which leads the individual to act on the destination [

55]. Likewise, Cerquetti [

56] emphasizes that engaging players on an emotional level helps to create a personal connection to cultural heritage through RPGs, and that players also develop deeper connections with characters in digital innovations during and after their visit. Players also realize emotional connections by sharing their gaming experiences with fellow players, spectators, and reviewers [

15]. Therefore, emotional engagement theoretically fosters empathy and prosocial attitudes (e.g., concern for heritage preservation).

Emotional engagement as a mediating mechanism between digital heritage stimuli and user responses and how simulated emotions are translated into attitudes or behaviors needs to be explicitly explored. This study bridges this gap by exploring affective engagement as a key mediating variable in the SOR model. RPGs trigger affective engagement (through their immersive experience, storyline, and role-playing elements), which in turn influences changes in participants’ attitudes towards the preservation of ancient architectural cultural heritage and their willingness to travel. Thus, this study directly responds to the call for research on the affective mechanisms linking digital heritage experiences to actual attitudes and behaviors, which will facilitate further structural transformation of the cultural industry [

57]. The following hypotheses are therefore proposed:

H1b. Immersion indirectly but positively influences players’ travel intention through emotional engagement.

H2b. Storytelling indirectly but positively influences players’ travel intention through emotional engagement.

H3b. Cognitive involvement indirectly but positively influences players’ travel intention through emotional engagement.

H4. Emotional engagement positively influences travel intention.

H5. Emotional engagement positively influences heritage preservation indicators.

2.4. Key Structures of Response

“Response” in the SOR framework corresponds to the outcome or behavior resulting from an experience [

53]. In heritage tourism research, two key response variables are travel intention (desire or intention to visit the site in person) and heritage preservation indicators (willingness to support, volunteer, or donate to the preservation of the site, etc.).

Travel intention represents the economic sustainability of ancient architectural cultural heritage, with key indicators including willingness to revisit, willingness to pay for heritage preservation, and recommendations through channels. The perceived image of ancient architectural cultural heritage influences tourists’ choices, anticipations, and overall satisfaction, making it a significant area of inquiry for both scholars and tourism professionals [

58]. Studies of customer experience frequently adopt a broad perspective, as this approach aids in predicting future consumer behaviors [

59]. Positive experiences generally foster emotional connections to particular entities [

60], and when these entities involve destinations or specific locations, the resulting emotional bond aligns with the concept of place attachment in environmental psychology [

61]. Such place attachment is considered influential in determining individuals’ revisit intentions, which serve as indicators of destination loyalty [

62]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H6. Travel intention positively influences heritage preservation indicators.

Heritage preservation indicators represent the environmental sustainability (raising awareness of preservation) and socio-cultural sustainability (promoting local consumption and cultural diffusion) that digital innovation can support. Ancient architectural heritage, as a non-renewable resource on which cities depend, is crucial to urban character and a driving force for cities to be vibrant as centers of economic development [

63]. Anthropogenic hazards and environmental pressures on architectural heritage may adversely affect its value [

64]. RPGs, in addition to their promotional and dissemination roles, can be realized to some extent as substitutes for tours of fragile ancient architecture as well. Cultural heritage organizations can greatly enhance visibility, audience interaction, and economic outcomes by integrating digital technologies that align visitor expectations with contemporary digital behaviors [

65]. Using heritage preservation indicators as a response structure bridges the research gap on whether playing RPGs related to ancient architectural cultural heritage translates into greater support for heritage preservation, which is in line with heritage tourism’s sustainability goal of linking digital engagement with real-world actions to preserve heritage.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design

This research employed a quantitative survey-based method to empirically evaluate the proposed research model. Utilizing survey methods offered several distinct advantages for this particular study. First, since the data required was based primarily on respondents’ perceptions—specifically their intentions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding visits to ancient cultural heritage sites influenced by RPGs—a questionnaire-based approach was considered highly appropriate [

66]. Second, using a survey enhanced the interpretative clarity and statistical robustness of the findings [

67]. Given the specificity of the data—travel intention driven by RPG experiences—which was unavailable in public databases, primary data collection was necessary.

Participants were systematically recruited for this investigation. The researchers formulated a structured questionnaire by critically reviewing the relevant literature on the influence of RPGs on visitors’ intentions to visit ancient cultural heritage sites. The finalized questionnaire comprised three distinct sections. The initial segment encompassed informed consent procedures and validated each respondent’s eligibility based on prior RPG experience set within contexts involving ancient architecture. Participants who either declined consent or lacked the requisite gaming experience were excluded from further participation. The second segment of the questionnaire gathered demographic details from participants, such as age, gender, and education level. The third and final section specifically captured respondents’ experiential data concerning their interactions with RPGs. Each questionnaire item within this section was rated using a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Measuring Instruments

The aim of this study was to investigate the direct and indirect factors influencing the experience of RPGs on the sustainable development of tourism in the cultural heritage of ancient architecture. To measure the variables in this study, 30 items were used. All the variables and user experience factors were measured using the items listed in

Table 1. These items were obtained from well-established studies in the literature related to the field of RPGs and cultural heritage research.

To ensure a wide range of respondents and accuracy in translation, the questionnaire was initially written in English and underwent a rigorous back-and-forth translation process. Initially, a bilingual researcher, who was not a native English speaker, translated all the questionnaire items from the original English version into the target language. Subsequently, another researcher independently back-translated these items into English. To ensure semantic accuracy, both researchers compared the two English translations, identifying and resolving discrepancies. Ultimately, the questionnaire was produced in both English and Chinese. To enhance content validity, four experts in heritage conservation and four professionals in RPG technologies reviewed the questionnaire, offering recommendations that improved the clarity and comprehensibility of certain items. After incorporating these revisions, the questionnaire was reassessed by the original translators and finalized. To further validate the questionnaire’s structure and wording, a pilot test was conducted with 30 participants familiar with RPGs featuring ancient architectural settings. The pilot test outcomes confirmed that the questionnaire items were clear and unambiguous. The pretest results were not accounted for in the total sample size.

3.3. Data Collection and General Demographics

Consistent with established research methods, the hypotheses in this study were examined using survey data. Researchers recruited respondents via gaming forums and social media communities focused on RPGs set in historical architectural contexts. Eligibility criteria included prior experience playing relevant RPGs. Of the initial 750 completed questionnaires collected, 56 were removed due to incompleteness or duplication. Thus, the final sample used for structural validation and hypothesis testing consisted of 694 valid responses.

Appendix A lists the characteristics of the respondents. The demographics of the respondents (N = 694) showed a relatively even distribution of background characteristics. In terms of gender, males comprised 58.5% (n = 406) of the sample while females comprised 41.5% (n = 288). The majority of respondents (51.0%) were between the ages of 18–25, followed by 28.1% aged 26–33. In terms of usage patterns of RPGs, participants appeared to be highly engaged. Playing “more than 10 h” (41.5%) and “8–10 h” (35.4%) per week indicated a high level of engagement with RPGs, with only 5.9% of respondents reporting less than 4 h of play per week. The frequency of play likewise reflected regular engagement, with a total of 87.4% of respondents playing at least once a day or more.

Moreover, slightly more than two-fifths (41.2%) of respondents had played only one type of RPG, while 58.8% had explored two or more variants. These findings indicate a high level of participation in RPG activities in the sample, thus providing a relevant contextual basis for examining the impact of RPG experiences on the sustainability of tourism in ancient and cultural heritage. Further, non-response bias was assessed using extrapolation to compare late and early respondents [

75]. No differences were found in either demographic or substantive variables, suggesting that there was no substantial non-response bias.

3.4. Research Methodology

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were performed using AMOS software to ensure robust statistical analysis [

76]. SEM was specifically employed as a validation method to assess theoretical models derived from prior research, examining the alignment between the theoretical framework and the collected empirical data [

77]. This analytical technique simultaneously evaluated measurement errors for independent and dependent variables and investigated all the relationships within the proposed research model. Consequently, employing SEM mitigated statistical inaccuracies and lowered the possibility of incorrect conclusions [

78].

4. Results

The data analysis adhered to the two-stage method recommended by Anderson and Gerbing [

79]. Initially, the study validated the measurement model by assessing convergent and discriminant validity, subsequently testing the research hypotheses via the structural model.

4.1. Measurement Model

Reliability and validity were assessed using reflective measurement models, as outlined by Ledgerwood and Shrout [

80]. The reliability test results, presented in

Table 2, showed strong internal consistency, as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and composite reliability (CR) values surpassing the standard benchmarks. Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.859 and 0.928, and CR values ranged from 0.864 to 0.934, confirming the robustness of the scales utilized. Furthermore, the individual factor loadings exceeded 0.65, with the majority surpassing 0.70, reinforcing the constructs’ unidimensionality and verifying that each measurement adequately represented its underlying factor. Additionally, convergent validity was confirmed through average variance extracted (AVE) values, which ranged from 0.563 to 0.740, thus surpassing the recommended minimum threshold of 0.50. These outcomes demonstrate that the constructs effectively explain substantial variance in their observed indicators.

Overall, the combination of high factor loadings, satisfactory composite reliabilities, and acceptable AVE values provided strong evidence of the reliability and validity of the measurement model. This consistency and convergent validity suggest that the scale used in this study is measurably sound and suitable for studying the impact of role-playing game experiences on sustainable tourism development in the context of ancient architectural heritage.

As shown in

Table 3, The validation factor analysis revealed an excellent model fit, with a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) of 1.402 (<3.0) and a root mean square residual (RMR) of 0.033, suggesting that there was very little discrepancy between the theoretical model and the observed data. Additionally, the model exhibited robust goodness-of-fit indicators: the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) was 0.951, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.90; the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) achieved a high value of 0.988; and the comparative fit index (CFI) reached 0.989, exceeding the widely accepted minimum standard of 0.95. Moreover, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value was 0.024, comfortably within the acceptable range (≤0.05). These metrics collectively confirm that the measurement model possesses strong psychometric validity, thereby justifying its application in subsequent analytical procedures.

Given that questionnaire-based data collection can introduce common method bias, this study employed Harman’s single-factor test to evaluate its potential presence. Following Podsakoff et al. [

81], principal component analysis was performed on all the questionnaire items. The results demonstrated that the identified factors collectively accounted for 72.628% of the total variance, indicating a substantial explanatory capacity within the dataset. Moreover, the first extracted factor explained only 33.796% of the variance. Since no single factor dominated, the results confirm that common method bias was unlikely to pose a significant concern in this research.

Appendix B shows that, on average, participants reported moderate to high levels of immersion (M = 3.53, SD = 1.04), storytelling (M = 3.61, SD = 0.84), cognitive involvement (M = 3.80, SD = 1.00), emotional engagement (M = 3.79, SD = 0.86), travel intention (M = 3.72, SD = 0.93), and heritage preservation indicators (M = 3.60, SD = 1.04). The correlation coefficients among these six core constructs are positive and statistically significant (

p < 0.01). The diagonal values (ranging from 0.750 to 0.860) exceed the off-diagonal correlations for each pair of latent constructs, thereby demonstrating satisfactory discriminant validity. Overall, these data indicate that the proposed constructs are both psychometrically robust and meaningfully correlated in the context of examining how role-playing game experiences influence the sustainability of tourism to ancient architectural cultural heritage sites.

4.2. SEM and Direct and Mediated Path Tests

SEM was employed to test the hypothesized relationships among the study variables. SEM serves as a comprehensive analytical technique that allows researchers to examine complex causal relationships within theoretical frameworks, incorporating both measurement and structural components [

82]. This method enables the simultaneous testing of multiple dependencies, providing a robust evaluation of the proposed research model. In this study, these are the relationships between players’ perceived factors in playing RPGs set in ancient architecture and players’ intentions to visit ancient architectural cultural heritage sites.

Figure 2 shows the application of the measurement model to this relationship. The final structural model, which results from applying the refinement criteria mentioned in the modeling section, contains 30 items.

Subsequently, the complete structural model was evaluated.

Table 4 summarizes the model fit indices derived from this structural equation modeling analysis, demonstrating satisfactory alignment between the hypothesized model and the empirical data. Specifically, key indicators—including CMIN/DF, IFI, TLI, CFI, and RMSEA—confirm that the proposed structural model achieves a robust fit to the dataset [

83].

Then, the significance and relevance of the relationships in the structural model were assessed by estimating the path coefficients, the significance of the path coefficients (using the bootstrapping method with 2000 resamples), and the effect sizes of the path coefficients. The direct effects were examined first (

Table 5), and then indirect effects were assessed for mediation analysis (

Table 6). The SEM path analysis in

Table 5 explores the direct relationships between several constructs, focusing on their direct and indirect effects on emotional engagement and travel intention.

Specifically, the direct impact analyses (

Table 5) indicated that immersion, storytelling, and cognitive involvement all had statistically significant positive effects on emotional engagement (

p < 0.001). In turn, immersion (β = 0.163,

p < 0.001) and storytelling (β = 0.155,

p < 0.001) showed significant direct effects on travel intention, whereas cognitive involvement did not have a direct effect on travel intention (

p = 0.492). Emotional engagement emerged as a strong predictor of travel intention (β = 0.334,

p < 0.001) and was also found to positively influence the heritage preservation indicator (β = 0.278,

p < 0.001). In contrast, the direct effect of travel intention on heritage preservation indicators did not reach statistical significance (

p = 0.106), suggesting that the pathway from travel intention to heritage preservation indicators may be moderated by other variables.

Finally,

Table 6 presents the analysis of the indirect effects between game perception variables and travel intention, highlighting the mediating role of emotional engagement. The results indicate that emotional responses significantly mediate the relationships between immersion, storytelling, and cognitive involvement and the intention to visit ancient architectural heritage sites. This underscores the importance of emotional experience as a key mechanism through which game-based elements influence travel-related decision-making.

The mediation analysis (

Table 6) further elucidated the role of emotional engagement as a mediating mechanism. To be specific, while both immersion and storytelling had significant direct effects on travel intention, their indirect effects (0.075 and 0.056) through emotional engagement were also statistically significant (

p < 0.001), suggesting a partial mediating role. On the contrary, the direct effect of cognitive involvement on travel intention was not significant, but its indirect effect through emotional engagement (0.067) was significant (

p < 0.001), indicating a fully mediating effect. In summary, these findings highlight that emotional engagement is a key mediator connecting individuals’ perceptions of RPGs (immersion, storytelling, and cognitive involvement) with their subsequent intentions to travel, and that emotional engagement is also part of the basis for the promotion of heritage conservation indicators.

5. Discussion

The present study investigated the interplay between the perception of RPGs and emotional engagement in explaining travel intention. The study supports previous research in which players’ perceptions of RPGs set in ancient architecture influence travel intentions, as well as emotional engagement assuming a mediating role in this relationship. Our model-based analysis was validated against the data and is discussed below.

Specifically, direct effect analyses indicated that immersion, storytelling, and cognitive involvement all positively predicted emotional engagement, with immersion and storytelling directly affecting travel intention and cognitive involvement not. Emotional engagement also strongly predicted travel intention and heritage preservation indicators, although travel intention did not directly influence heritage preservation indicators. Mediation analyses confirmed that emotional engagement partially mediated the effects of immersion and storytelling on travel intention and fully mediated the effects of cognitive involvement. These findings emphasize the central role of emotional engagement in linking the experience of various RPGs set in ancient architecture to subsequent travel intentions, which in turn can contribute to the sustainable development of ancient architectural cultural heritage.

Immersion indirectly increases players’ travel intentions towards relevant ancient architectural cultural heritage destinations by facilitating emotional engagement with players of RPGs. Consistent with existing research, the level of immersion that players feel towards the represented historical locations may transform their gaming process into a form of digital tourism, an enjoyable experience that promotes a desire to visit authentic ancient architectural cultural heritage sites [

84]. Jang’s [

85] study, for example, proposes that the immersion fostered by games can inspire a desire to travel to real-life ancient architectural cultural heritage sites. The specific representations of the game shape expectations and thus influence the nature and extent of the tourism program.

Storytelling mediates the emotional engagement of players of RPGs as a motivation for players’ travel intentions towards relevant ancient architectural cultural heritage sites. To be specific, different storytelling approaches convey different values of cultural heritage [

56]. Šisler et al. [

86] similarly explored how storytelling through ancient architecture can be disseminated through RPGs to create and reproduce a collective understanding of cultural heritage and further contribute to player behavioral intentions.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that, unlike immersion and storytelling, cognitive involvement only indirectly affects travel intention through emotional engagement, and two mechanisms may explain this pattern. The first is the dual-process theory of decision-making, which suggests that cognitive appraisals must be “elicited” by affective states in order to be translated into intentional outcomes [

87]. In RPGs related to ancient architectural cultural heritage, players may intellectually appreciate historical facts or architectural details, but this knowledge remains abstract unless combined with excitement, nostalgia, or empathy, which shortens the psychological distance and inspires real-world visits [

88]. Subsequently, the lack of physical cues (e.g., ambient sounds, temperature, smells) in screen-based RPGs limits sensory embodiment; emotional immersion compensates for this by simulating a sense of presence, thereby transforming pure cognition into actionable desire [

84]. Therefore, designers and heritage managers should embed emotional elements—music, character arcs, moral dilemmas—in factual content in order to ensure that informational engagement triggers tourist behavior.

Emotional engagement has a positive impact on both the travel intentions of players of RPGs and the heritage preservation indicators of related ancient architecture. Emotional engagement is widely understood as the establishment of a real and virtual ancient architecture with which people have special emotional connections [

89]. The findings related to travel intention align with Sharma’s [

90] assertion that emotional engagement and intentionality within gameplay act as catalysts for motivating players to visit corresponding real-world destinations. This reinforces the view that affective and cognitive experiences in virtual environments can significantly influence real-world behavioral intentions. Moreover, the findings on heritage preservation indicators are also consistent with the theory that cultural heritage games raise emotional awareness and motivate users to adopt sustainable practices related to cultural heritage [

91]. Outcomes such as conservation policy support and increased public awareness reflect the success of play-based heritage promotion programs [

92].

In contrast, the travel intention of players of RPGs is not directly related to the heritage preservation indicators of related ancient architecture, which can be explained by the fact that heritage preservation intention may be a prior variable of travel intention. On the other hand, although a large number of tourists’ intentions and behaviors may bring economic benefits to a local area, they may also increase the burden of cultural heritage preservation of the ancient architecture, so travel intention is not positively related to the heritage preservation indicators of the relevant ancient architecture.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study emphasize the powerful role of digital RPGs in promoting sustainable tourism engagement and conservation outcomes at ancient architectural sites. Through the lens of the SOR framework, experiential stimuli—immersion, storytelling, and cognitive engagement—can significantly enhance tourists’ affective engagement with cultural sites (organismic states). This heightened emotion in turn leads to two distinct outcomes: a stronger intention to visit and stronger willingness to support conservation. Crucially, emotional engagement partially mediates the effects of immersion and narrative, and fully mediates the effects of cognitive engagement, suggesting that cognition alone is not enough and that behavior must be “empowered” by emotion.

Stated differently, while immersive environments and rich narrative elements can directly motivate tourists to visit heritage sites, their most far-reaching impacts are exerted through the emotional bonds they foster. Rational appreciation only translates into a willingness to travel when it is emotionally stimulated, and emotional engagement directly predicts willingness to support conservation. These insights make RPGs a good catalyst for tourism development and heritage management.

These relationships refine the theory in two ways. On the one hand, they extend the SOR framework to the domain of interactive recreation by elucidating the boundary conditions under which cognitive inputs are transformed into behavioral outputs. On the other hand, they reveal that the psychological drivers of travel and protection are not the same. Willingness to travel does not directly predict conservation support, whereas emotions do. This separation suggests that economic and stewardship motives respond to different levers and should be modeled separately in heritage tourism research.

From a design management perspective, the findings highlight design principles for game studios, destination marketers, and venue managers. Games that intertwine historically restored environments with compelling narratives and sensory immersion are most likely to trigger emotional resonance and transform remote play into on-site visits. Simultaneously, if the game also aims to support conservation, developers should embed cues such as moral choices, character attachments, or post-game calls to action to foster empathy for the cultural landscape. For heritage organizations, working with commercial game producers offers a scalable way to reach a wider audience without the physical wear and tear on fragile sites that mass tourism can cause. Virtual experiences can serve as both a “soft gateway” to the final tour and as a partial alternative, taking pressure off of fragile structures. This is consistent with the broader goal of sustainable tourism in cultural landscapes: to encourage visitors to interact meaningfully with the landscape, enhancing appreciation without compromising heritage resources.

Notably, digital RPG experiences allow for virtual immersion in historical environments, with the potential to reach a global audience and inspire far-flung visitors to care for sites. As such, such tools can complement physical tours, increase awareness and respect, and ultimately transform visitors into advocates for preservation. Collectively, this research highlights the promise of combining digital innovations with cultural heritage interpretation—an approach that can stimulate tourism interest and deepen conservation impacts at the same time. These insights not only fill a gap in the literature, but also inspire the further exploration of gamified narratives, affective design, and their ability to strike a harmonious balance between tourist engagement and cultural heritage preservation.

Despite its robust findings, this study faces several limitations. First, given its cross-sectional design, the data capture a single snapshot in time, which may limit our ability to infer causal relationships. Future studies could employ longitudinal or experimental designs to more accurately gauge how individuals’ perceptions and emotions evolve over multiple exposures to RPGs related to ancient architecture. Second, the reliance on self-reported data raises concerns about common method bias and social desirability effects, even though procedural and statistical checks were conducted. Integrating multiple data sources, such as actual visitation records or physiological measures of emotional engagement, could bolster the validity of the findings. Third, the sample, although relatively large, comprised individuals heavily engaged in gaming communities, which might limit the generalizability of the results to more casual players or to those who engage with other forms of digital media.

Future research could explore broader comparative contexts and technologies to further validate and extend the current insights. Cross-cultural comparisons would be particularly illuminating, examining how different cultural backgrounds influence players’ emotional engagement and heritage preservation indicators. Likewise, investigating other digital platforms or game genres (e.g., augmented reality tours, online multiplayer environments) could reveal whether the same mediating and moderating mechanisms apply beyond the scope of RPGs. By integrating these methodological and conceptual expansions, subsequent research can build a more comprehensive picture of how digital innovations shape not only individual tourism intentions but also collective ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., J.Y. and W.Y. (Wenjun Yan); methodology, S.W.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W., J.Y. and W.Y. (Wenjun Yan); formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, S.W. and K.N.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and W.Y. (Weijia Yang); visualization, S.W., J.Y. and W.Y. (Wenjun Yan); supervision, W.Y. (Weijia Yang) and K.N.; project administration, W.Y. (Weijia Yang) and K.N.; funding acquisition, W.Y. (Weijia Yang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research and Development Fund for Talent Initiation Project of Zhejiang A&F University: “Research on the Integration of Industry and Education in Industrial Design Empowered by Artificial Intelligence in the Internet Era” (Project No. 2024FR044).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Based on standard ethical guidelines, Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sociodemographic Profile of Sample.

Table A1.

Sociodemographic Profile of Sample.

| Items | Options | Frequency (N = 694) | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Gender | Male | 406 | 58.5% |

| Female | 288 | 41.5% |

| Age | 18–25 | 351 | 51.0% |

| 26–33 | 193 | 28.1% |

| 34–41 | 98 | 14.2% |

| 42–49 | 34 | 4.9% |

| 50 years and over | 12 | 1.7% |

| Educational background | Undergraduate | 273 | 39.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 206 | 29.7% |

| Master’s degree | 102 | 14.7% |

| Doctoral degree | 30 | 4.3% |

| Other | 83 | 12.0% |

| Employment status | Student or student worker | 256 | 36.9% |

| Self-employed | 88 | 12.7% |

| Full-time employed | 188 | 27.1% |

| Part-time employed | 141 | 20.3% |

| Unemployed or retired | 21 | 3.0% |

| Average time spent playing RPGs per week | Less than 2 h | 11 | 1.6% |

| 2 h–4 h | 30 | 4.3% |

| 5 h–7 h | 119 | 17.1% |

| 8 h–10 h | 246 | 35.4% |

| More than 10 h | 288 | 41.5% |

| Average frequency of playing RPGs per week | Once every 4–7 days | 21 | 3.0% |

| Once every 2–3 days | 66 | 9.5% |

| Once a day | 170 | 24.5% |

| Twice a day | 237 | 34.1% |

| Many times a day | 200 | 28.8% |

| Number of types of RPGs experienced | 1 | 286 | 41.2% |

| 2 | 198 | 28.5% |

| 3 | 103 | 14.8% |

| 4 | 48 | 6.9% |

| More than 4 | 59 | 8.5% |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Related Analysis Results.

Table A2.

Related Analysis Results.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.41 | 0.49 | -- | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 2. Age | 1.78 | 0.98 | 0.060 | -- | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 3. Edu | 2.20 | 1.32 | −0.034 | 0.018 | -- | | | | | | | | | | |

| 4. Status | 2.40 | 1.25 | 0.028 | 0.065 | −0.048 | -- | | | | | | | | | |

| 5. Spent | 4.11 | 0.94 | 0.017 | −0.003 | −0.019 | −0.033 | -- | | | | | | | | |

| 6. Frequency | 3.76 | 1.06 | −0.040 | 0.050 | −0.027 | 0.013 | 0.000 | -- | | | | | | | |

| 7. Number | 2.13 | 1.26 | 0.036 | −0.001 | −0.017 | −0.004 | −0.019 | −0.063 | -- | | | | | | |

| 8. Immersion | 3.53 | 1.04 | 0.012 | 0.015 | −0.010 | 0.016 | 0.014 | −0.010 | 0.014 | 0.822 | | | | | |

| 9. Storytelling | 3.61 | 0.84 | −0.035 | −0.002 | −0.003 | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.067 | −0.042 | 0.531 ** | 0.823 | | | | |

| 10. Cognitive Involvement | 3.80 | 1.00 | −0.008 | 0.026 | −0.015 | 0.023 | 0.016 | −0.018 | −0.034 | 0.479 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.808 | | | |

| 11. Emotional Engagement | 3.79 | 0.86 | 0.007 | 0.018 | −0.005 | 0.052 | 0.026 | −0.031 | −0.031 | 0.378 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.798 | | |

| 12. Visitor Intention | 3.72 | 0.93 | −0.061 | −0.036 | −0.022 | −0.001 | 0.012 | −0.020 | 0.004 | 0.379 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.860 | |

| 13. Heritage Preservation Indicators | 3.60 | 1.04 | −0.002 | 0.024 | 0.031 | −0.025 | 0.018 | 0.036 | −0.009 | 0.295 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.750 |

References

- Yu, Y.; Raed, A.A.; Peng, Y.; Pottgiesser, U.; Verbree, E.; van Oosterom, P. How digital technologies have been applied for architectural heritage risk management: A systemic literature review from 2014 to 2024. NPJ Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, M.; Liang, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Law, A. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagomarsino, S.; Podestà, S. Damage and vulnerability assessment of churches after the 2002 Molise, Italy, earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2004, 20 (Suppl. S1), 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykourentzou, I.; Antoniou, A. Digital innovation for cultural heritage: Lessons from the European year of cultural heritage. SCIRES-IT-Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Pham, H.H.; May, A.Y.C.; Chin, T.L. Exploring the Landscape of Role-Playing Game Research Through Bibliometric Analysis From 1986 to 2023 Using Scopus Database. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2025, 2025, 2315333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochocki, M.; Krawczyk, S.; Mochocka, A. Polish History up to 1795 in Polish Games and Game Studies. Games Cult. 2024, 15554120241228490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M.; McDonell, K.; Reynolds, L. Role play with large language models. Nature 2023, 623, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzoli, D.; Qureshi, A.; Dunwell, I.; Petridis, P.; De Freitas, S.; Rebolledo-Mendez, G. Levels of interaction (loi): A model for scaffolding learner engagement in an immersive environment. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Tutoring Systems: 10th International Conference, ITS 2010, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 14–18 June 2010; Proceedings, Part II 10. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 393–395. [Google Scholar]

- Malegiannaki, I.; Daradoumis, Τ. Analyzing the educational design, use and effect of spatial games for cultural heritage: A literature review. Comput. Educ. 2017, 108, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kapell, M.W.; Elliott, A.B. (Eds.) Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacini, E.; Giaccone, S.C. Gamification and cultural institutions in cultural heritage promotion: A successful example from Italy. Cult. Trends 2022, 31, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitong, W.; Bing, Z.; Yiming, Z.; Shiyi, D. A three-dimensional study on the international communication of Black Myth: Wukong. Int. Commun. Chin. Cult. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, M.; Nisi, V. Leveraging Transmedia storytelling to engage tourists in the understanding of the destination’s local heritage. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 34813–34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochocki, M. Heritage sites and video games: Questions of authenticity and immersion. Games Cult. 2021, 16, 951–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; MacLaurin, T.; Crotts, J.C. Travel blogs and the implications for destination marketing. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.A.; Gretzel, U. Success factors for destination marketing web sites: A qualitative meta-analysis. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.; Page, S.J.; Buhalis, D. Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Potter, L.E. Virtual reality and tourism marketing: Conceptualizing a framework on presence, emotion, and intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1505–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Pictorial element of destination in image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 537–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Pan, Y. What Influences Users’ Continuous Behavioral Intention in Cultural Heritage Virtual Tourism: Integrating Experience Economy Theory and Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, R.; Zheng, F. Understanding users’ behavior intention of serious games for intangible cultural heritage based on the stimulus-organism-response model. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 5137–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, J.; Woo, W. Metadata schema for context-aware augmented reality applications in cultural heritage domain. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; Volume 2, pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Mochocki, M. Role-Play as a Heritage Practice: Historical LARP, Tabletop RPG and Reenactment; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baber, R.; Baber, P. Influence of social media marketing efforts, e-reputation and destination image on intention to visit among tourists: Application of SOR model. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 2298–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.K.; Cheung, C.M.; Lee, Z.W. The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ha, S.; Widdows, R. Consumer responses to high-technology products: Product attributes, cognition, and emotions. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ahn, S. Exploring user behavior based on metaverse: A modeling study of user experience factors. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Antlej, K.; Bykersma, M.; Mortimer, M.; Vickers-Rich, P.; Rich, T.; Horan, B. Real-world data for virtual reality experiences: Interpreting excavations. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) Held Jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.L. Immersion vs. interactivity: Virtual reality and literary theory. Postmod. Cult. 1994, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, A. Immersion, engagement, and presence: A method for analyzing 3-D video games. In The Video Game Theory Reader; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.; Cairns, P. A grounded investigation of game immersion. In CHI’04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaderberg, M.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Dunning, I.; Marris, L.; Lever, G.; Castaneda, A.G.; Beattie, C.; Rabinowitz, N.C.; Morscos, A.S.; Ruderman, A.; et al. Human-level performance in 3D multiplayer games with population-based reinforcement learning. Science 2019, 364, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzin, A.; Junior, R.A.; Hammond, T.; Anastasio, D. Investigating engagement and flow with a placed-based immersive virtual reality game. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2021, 30, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, G. In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Bang, S.; Woo, W. Authoring personal interpretation in a 3D virtual heritage site to enhance visitor engagement. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) Held Jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rajani, M.B.; Patra, S.K.; Verma, M. Space observation for generating 3D perspective views and its implication to the study of the archaeological site of Badami in India. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, e20–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, C.; Zhao, W. Unlocking the impact of user experience on AI-powered mobile advertising engagement. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 4818–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.L. Immersion and shared imagination in role-playing games. In Role-Playing Game Studies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche, M. Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Buhalis, D.; Weber, J. Serious games and the gamification of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, H.; Similä, J.; Markkula, J. Utilizing online serious games to facilitate distributed requirements elicitation. J. Syst. Softw. 2015, 109, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.H.; Tang, K.Y. Who captures whom–Pokémon or tourists? A perspective of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, M.E.; Caci, B.; Cardaci, M.; Perticone, V. Early usage of Pokémon Go and its personality correlates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, M.F.; Perreault, G.; Suarez, A. What does it mean to be a female character in “indie” game storytelling? Narrative framing and humanization in independently developed video games. Games Cult. 2022, 17, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, M.; Young, H.; Sosnowska, E. Evaluating emotional engagement in digital stories for interpreting the past. The case of the Hunterian Museum’s Antonine Wall EMOTIVE experiences. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) Held Jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. World Heritage listing and changes of political values: A case study in West Lake Cultural Landscape in Hongzhou, China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Stylidis, D.; Ivkov, M. Explaining conative destination image through cognitive and affective destination image and emotional solidarity with residents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.W.; Chan, H.Y.; Hou, H.T. Role-playing monument exploration: An online educational game with a role-playing mechanism and multi-dimensional scaffolding for monument tours. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. How does involvement affect attendees’ aboriginal tourism image? Evidence from aboriginal festivals in Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2421–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Khan, S.; Uddin, F. The Power of Positive Emotions: Understanding How Positive Emotions Influence Cognitive Learning Processes. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Arch. 2024, 7, 676. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, D.J.; Young, M. Evaluative images and tourism: The use of personal constructs to describe the structure of destination images. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerquetti, M. The importance of being earnest. Enhancing the authentic experience of cultural heritage through the experience-based approach. In The Experience Logic as a New Perspective for Marketing Management: From Theory to Practical Applications in Different Sectors; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, S. What has influenced the growth and structural transformation of China’s cultural industry?—Based on the input-output bias analysis. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. Advancing destination image: The destination content model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Nah, K. Exploring Sustainable Learning Intentions of Employees Using Online Learning Modules of Office Apps Based on User Experience Factors: Using the Adapted UTAUT Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kyle, G.; Scott, D. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Jin, W.; Okumus, F. Constructing a model of exhibition attachment: Motivation, attachment, and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Payini, V.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mallya, J.; Gopalakrishnan, P. Visitors’ place attachment and destination loyalty: Examining the roles of emotional solidarity and perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. From virtual to actual destinations: Do interactions with others, emotional solidarity, and destination image in online games influence willingness to travel? Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 1427–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, M. Vulnerability of World Cultural Heritage Sites in developing Asian countries. NPJ Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Liu, J.; Nah, K.; Yan, W.; Tan, S. The Influence of AR on Purchase Intentions of Cultural Heritage Products: The TAM and Flow-Based Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of Behavioral Research; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Nah, K. Exploring the mechanisms influencing users’ willingness to pay for green real estate projects in Asia based on technology acceptance modeling theory. Buildings 2024, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, C.; Cox, A.L.; Cairns, P.; Dhoparee, S.; Epps, A.; Tijs, T.; Walton, A. Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, D.; Greitemeyer, T. Immersed in virtual worlds and minds: Effects of in-game storytelling on immersion, need satisfaction, and affective theory of mind. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 6, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.Y.; Huang, Y.H. An analytic creativity assessment scale for digital game story design: Construct validity, internal consistency and interrater reliability. Creat. Res. J. 2015, 27, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Luo, X.R.; Wu, K.; Zhao, W. Exploring viewer participation in online video game streaming: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niksirat, K.S.; Chen, S.; Weng, D.; Sarcar, S.; Ren, X. The impact of a multitasking-based virtual reality motion video game on the cognitive and physical abilities of older adults. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaus, M.; Greipl, S.; Kiili, K.; Lindstedt, A.; Huber, S.; Klein, E.; Karnath, H.O.; Moeller, K. Increased emotional engagement in game-based learning–A machine learning approach on facial emotion detection data. Comput. Educ. 2019, 142, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; Muñoz-González, C.; Joyanes-Díaz, M.D.; Jiménez-Morales, E.; López-Osorio, J.M.; Barrios-Pérez, R.; Rosa-Jiménez, C. Heritage risk index: A multi-criteria decision-making tool to prioritize municipal historic preservation projects. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. A method for comparing completely standardized solutions in multiple groups. Struct. Equ. Model. 2000, 7, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, A.; Shrout, P.E. The trade-off between accuracy and precision in latent variable models of mediation processes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S.; Chen, J. Enterprise Environmental Governance and Fluoride Consumption Management in the Global Sports Industry. Fluoride 2025, 58, 1. Available online: https://www.fluorideresearch.online/epub/files/306.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Bowman, N.D.; Vandewalle, A.; Daneels, R.; Lee, Y.; Chen, S. Animating a plausible past: Perceived realism and sense of place influence entertainment of and tourism intentions from historical video games. Games Cult. 2024, 19, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K. Real in virtual or virtual in real? Intersecting virtual and real experience in open-world video games and heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2024, 19, 714–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šisler, V.; Pötzsch, H.; Hannemann, T.; Cuhra, J.; Pinkas, J. History, heritage, and memory in video games: Approaching the past in Svoboda 1945: Liberation and Train to Sachsenhausen. Games Cult. 2022, 17, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, F.; Deutsch, R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, A. On Object Dialogue Boxes: Silence, empathy and unknowing. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Place: An experiential perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, H.G.; Singh, S.; Bajracharya, A.R. Identification of Indicators for Sustainability of Cultural Heritage. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 17, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Camuñas-García, D.; Cáceres-Reche, M.P.; Cambil-Hernández, M.D.L.E. Maximizing engagement with cultural heritage through video games. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage tourism in the 21st century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).