Abstract

One of the emerging forms of cooperation in managing government projects is partnering (samspill) to address repetitive problems in large projects. Inefficiency, conflict, and cost volatility remain work issues in the public sector. Although risk sharing and incentive schemes are other aspects of partnering that are the subject of a significant amount of research, there is limited investigation into the softer aspects of partnering. The nature of partnering and how it is practiced depends on various components, such as trust, leadership, and culture; however, they are not well defined or appreciated. This paper investigates how these soft aspects are implemented and perceived in four mega Norwegian public construction projects that use a partnering model. In the present study, a qualitative research approach was adopted, and nine face-to-face interviews were conducted with project leaders from four case organizations in public sector healthcare, government, and education sectors. However, despite having similar contractual provisions, the projects exhibited varying degrees of collaboration success, indicating that formal agreements alone do not determine effective partnering. The outcomes from this study established that value-based leadership is central to the success of collaboration and should, therefore, be a priority when designing partnering in the public sector. Additionally, the results add to the existing debates regarding the application of soft values in the formal structures of the business and support the notion of leadership-based approaches in construction management, especially in the public domain.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is known to be inefficient, costly, and characterized by contentious relationships between stakeholders especially in procurement. As per the recent literature, current procurement approaches like design–bid–build or design–build are criticized for increasing fragmentation, shifting risks, and promoting reactive problem solving rather than innovation, integration, or value [1,2]. These challenges are especially significant in Norway and other countries in the context of publicly financed infrastructure projects, as they require managing limited funds, reporting to multiple stakeholders, and dealing with complex projects. Disagreements, misunderstandings, and lack of cooperation persist in influencing project performance, resulting in financial and reputation losses among public agencies [3,4].

As a result, the concept of collaborative delivery models is on the rise. Integrated project delivery (IPD), lean construction, partnering, and value management (VM) strategies have been identified as more suitable approaches [5,6]. These models seek to eliminate adversarial postures, engage all stakeholders right from the planning stage, and establish structures that support the sharing of information, development of trust, and cooperation [1]. Particularly in the Norwegian public sector, partnership is encouraged as a more flexible form of collaboration that includes both the relational aspects, like trust, culture fit, and leadership styles, and the transactional aspects, such as incentives, risk, and rewards [7].

While there are numerous studies on partnering models and their contractual underpinnings [8], there is a conceptual gap in the literature: How are the soft partnering aspects, such as organizational, leadership, and trust culture, implemented, particularly in the initial phases of public projects? This first phase (Phase 1) is recognized as crucial because it establishes the goals, roles, and responsibilities of the team and expectations from the stakeholders [9,10]. Nevertheless, studies that explore how these soft values are carried out and implemented in public projects are scarce [11].

According to the VM literature, structured stakeholder engagement, collaboration, and trust are considered critical to enhancing function, cost, and quality [12,13]. There is a recognized need for a value-driven process that emphasizes communication and shared understanding, rather than isolated technical optimization [14]. Furthermore, engaging in constructive conflict within a collaborative environment can enhance both participant satisfaction and creative outcomes during VM workshops. There is need for proper structure of the VM team, a common vision for VM initiatives, and pre-workshop activities [15,16].

Such evidence is supported by the partnering literature, which states that alliance is not just a technique but a relationship-oriented approach [17]. Routines and organizational behaviors need to facilitate the institutionalization of partnering through constant learning and active leadership [5]. Likewise, Pinnell also emphasized the need to implement a coordinated approach to conflict management to reduce legal action and foster a non-litigious project environment [18]. An extended review of the theoretical uncertainties surrounding partnering relationships suggests adopting a more relational and process-oriented perspective [5].

In all these sources of literature, leadership has been identified as a factor that enhances effective collaboration [8,19]. It is not enough to set up frameworks or organize workshops. There must be an agent that drives the partnering process, demonstrates partnering behaviors, and manages uncertainty [6,8]. Value-based leadership, including ethical, authentic, or servant leadership, has to trickle down from the top organizational leadership to the frontline project management. This is in line with other studies that postulate that trust, reliability, and commitment represent an important but delicate foundation for collaboration in construction projects involving multiple stakeholders [20,21].

Despite this robust theoretical base, little empirical insight exists into how these ideas are realized in public sector projects, particularly during the initial stages. Most studies focus on private or hybrid contexts or emphasize formal instruments like risk registers and incentive contracts rather than the lived experiences of project participants.

This study seeks to address that gap by examining how soft elements, like creating trust, building culture, and leadership style, are practiced in four large Norwegian public partnering projects. Using qualitative interviews with key project leaders, the study explores three central research questions:

RQ1: How are soft elements like trust, shared culture, and value alignment operationalized during the early phase?

RQ2: What leadership behaviors and structures support or inhibit collaborative outcomes?

RQ3: What differentiates successful early-phase partnering processes from less successful ones?

By answering these questions, this study offers both practical and theoretical contributions to understanding the human dynamics of collaboration in construction. It also reinforces the importance of value-based leadership in a domain typically dominated by technical and contractual matters.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

This research employed a qualitative and exploratory research design to investigate how soft factors, such as trust, leadership behavior, and organizational culture, are implemented during the early phase of collaborative public construction projects. Given the relational and context-dependent nature of these elements, the qualitative approach was identified as the best method of recording tacit knowledge, personal experience, and interaction among the project stakeholders.

This approach was chosen as prior qualitative studies in complex social interactions, particularly in areas like partnering and value management, emphasize the need to understand how individuals interpret, act, and make decisions within real project settings. An in-depth qualitative investigation using semi-structured interviews was thus deemed most appropriate for exploring the nuanced perceptions and lived experiences of project leaders, allowing for a deeper understanding of phenomena influenced by multiple factors.

This approach is widely used in construction management research, particularly in studies where complex social interactions, like those in partnering, value management, or stakeholder engagement, are difficult to measure quantitatively. It also aligns with previous work on value-based delivery, trust building, and collaborative governance, which emphasizes the need to understand how people interpret, act, and make decisions within real project settings [22,23,24].

2.2. Case Selection

The research centered on four major public construction projects in Norway that used the samspill (partnering) approach as their contractual and collaborative vehicle. Cases were selected using two criteria: (1) they were commissioned or spearheaded by public sector organizations, and (2) they utilized partnering strategies in the initial phase (Phase 1).

These projects represented a range of early-phase collaboration outcomes, allowing for comparative insights into what facilitates or hinders successful cooperation, consistent with the case study approaches advocated by [25,26].

The projects were:

- Project Alpha: A regional hospital construction project;

- Project Bravo: A major emergency healthcare facility located in a metropolitan area;

- Project Charlie: A government office reconstruction project in the administrative center of the country;

- Project Delta: An anonymized public sector project involving multiple stakeholders, the details of which remain confidential at the request of participants.

While they differed in scope, size, and organizational culture, all were high-stakes, publicly funded initiatives involving complex stakeholder environments.

To provide further context on the scale of the projects analyzed, we include key financial data. Project Alpha, a regional hospital construction project, had a cost framework of NOK 4.1 billion. Project Bravo, a major emergency healthcare facility, had a cost framework of NOK 1.5 billion. Project Charlie, a government office reconstruction project, had a cost framework of NOK 1.1 billion. For Project Delta, an anonymized public sector project, the contract sum was noted as large on a Norwegian scale. While building area was not systematically collected due to confidentiality and project status, these substantial cost frameworks firmly establish these as large-scale public construction projects. Their implementation statuses varied: Project Alpha’s Phase 1 was cancelled, Project Bravo had a planned completion in 2023, Project Charlie was in its implementation phase at the time of the study, and Project Delta did not proceed beyond Phase 1.

2.3. Participants

Nine participants were interviewed across the four projects. Each case was represented by two to three individuals who held leadership roles during the early planning and coordination stages. The participants included:

- Project directors (prosjektdirektører);

- Project leaders (prosjektledere);

- Process leaders (prosessledere);

- Design or group leaders (gruppeledere).

Participants were selected for their direct involvement in implementing partnering principles and their ability to reflect on the interaction between formal project mechanisms (such as contracts, and incentives) and soft factors (such as trust, communication, and values). This sampling strategy reflects prior qualitative studies that seek to capture insights from individuals in key decision-making roles, as highlighted also by [27,28].

2.4. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were the primary data-collection tool, chosen for their ability to explore complex topics in depth, as advocated by [29]. The interview guide was informed by the research questions and the existing literature on value management, partnering, and leadership. Input from a professional advisor also helped refine the guide. Participants received the guide beforehand to support preparation and openness. Participants were provided with a guide before the interviews to provide transparency and readiness.

The nine interviewees represented a diverse set of leadership roles critical to early-phase collaboration in public partnering projects. The participants included: Project Directors (prosjektdirektører), Project Leaders (prosjektledere), Process Leaders (prosessledere), and Design or Group Leaders (gruppeledere). Each of the four case projects included at least two interview participants, ensuring a balanced perspective across cases. Most participants had over a decade of experience in the Norwegian construction or infrastructure sector, often with direct involvement in large-scale public sector projects. Their educational backgrounds were typically at the bachelor’s or master’s level, primarily in engineering, architecture, or construction management. Several held senior positions within public or semi-public agencies, suggesting familiarity not only with technical aspects of project delivery but also with organizational leadership, stakeholder dialogue, and collaborative governance, key areas relevant to the study’s focus on value-based leadership.

All the interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams due to logistical constraints, a practice that is increasingly becoming mainstream in qualitative research. Each session lasted about one hour and was recorded with participant consent. Transcripts were produced for each interview and later verified by the interviewees to ensure accuracy and credibility.

In order to enhance triangulation and contextual validity, two business-to-business webinars were also part of the data-collection process. The webinars, organized by Construction City and Lean Construction Norway, were on collaborative models and early-stage partnering. These webinars served the purpose of enhancing and complementing the empirical evidence as well as checking against contemporary industry discourse.

2.5. Data Analysis

Interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following recognized procedures for identifying and categorizing patterns across qualitative material [30,31]. Initial coding led to the development of three major themes:

- Implementation of soft elements (e.g., trust, cultural alignment, leadership behavior);

- Differences between successful and less successful early-phase projects;

- Perceived interaction between hard and soft elements in partnering.

A comparative examination was subsequently conducted to identify the conditions within projects that successfully moved into implementation from Phase 1 and those that encountered friction, stagnation, or cancellation. This enabled the determination of relevant patterns and repeated behaviors that contributed to or detracted from cooperative efforts.

To assess project performance in the early phase, a set of qualitative criteria was applied, derived from interview data and triangulated with insights from industry webinars and the relevant literature. These included the degree and quality of trust-building efforts, the visibility and relational approach of client-side leadership, the design and facilitation quality of early-phase workshops and collaborative tools, the clarity and alignment of project goals among stakeholders, and the smoothness of the transition from planning to implementation.

All coding and synthesis were conducted using Microsoft Excel, and analytical rigor was supported by iterative memo-writing, which tracked interpretations, refined categories, and maintained transparency throughout the process.

2.6. Rationale for Method

This methodology was chosen because it allowed the research to capture value-based behaviors and nuanced interpersonal processes that are difficult to observe through quantitative measures [32]. Previous studies show that interviewing project actors with firsthand experience can reveal the cultural and behavioral patterns that shape collaboration and performance.

The participants in this study acted as both decision makers and influencers in their respective projects, making their insights especially valuable in understanding how partnering principles were (or were not) put into practice. By combining their perspectives with the current literature and insights from industry webinars, the study offers a context-sensitive and empirically grounded view of how formal partnering frameworks intersect with human factors, ultimately shaping the success or failure of early-phase collaboration in public construction projects.

3. Results

The analysis of interview data, informed by supporting literature and webinars, revealed several recurring themes related to how soft values are embedded during the early phases of public partnering projects. The main themes included trust building, client-side leadership, the use of collaborative tools, and the relationship between formal mechanisms and informal dynamics. For anonymity, the projects are referred to as Project Alpha (hospital), Project Bravo (emergency facility), Project Charlie (government building), and Project Delta (educational facility).

3.1. Importance of Trust Building and Transparency

Trust was the central driver of effective collaboration across all projects. In Projects Alpha and Bravo, participants illustrated how they deliberately set out to create an environment of openness and transparency from the beginning. The leadership teams promoted trust with casual relationship development, formal meetings, and shared areas. These steps proved useful in risk perception and aligning goals early on.

Co-location strategies and participatory planning reinforced trust in Project Alpha. Project Bravo similarly included key stakeholders early and used transparent decision-making approaches. Participants in both cases highlighted that trust minimized strategic behavior and helped to navigate uncertainty.

However, in the case of Projects Delta and Charlie, there were no strong trust-building efforts during the initial phase. Project Charlie’s participants reported a siloed work culture, unclear expectations, and slow communication. In Project Delta, stakeholders came into the project with skepticism, and there was no serious attempt to align behaviors or values.

This study’s results align with previous research that shows openness and trust are core to effective partnering, particularly in the early partnering stages, which are characterized by high uncertainty and stakeholder dependence [1,21]. These are also consistent with the wider value management literature, which emphasizes relational trust and stakeholder alignment as fundamental preconditions for successful collaboration.

3.2. Role of Client-Side Leadership

Client-side leadership was a key determinant of collaborative results in all cases. Projects Alpha and Bravo described leadership as value-driven, visible, and proactive. Leaders constructively managed early tensions, goals were communicated, and cooperative behavior was modeled.

Leadership went beyond contractual compliance to promote mutual respect and psychological safety in Project Bravo. Participating individuals also stressed that this approach created space for open, productive dialogue and built trust. These practices are consistent with the ideals of value-based leadership, such as ethical behavior, servant leadership, and authenticity and reflected in the broader leadership literature [1,14].

Conversely, Project Charlie’s leadership was process-focused and more reactive. Although there was some engagement, participants described a lack of initiative in promoting collaboration, resulting in misalignments and a weak commitment to the partnering philosophy. The leadership engagement with Project Delta was the weakest, characterized by a lack of guidance and role confusion in the shared process.

Findings are consistent with the perspective of leadership as a relational and dynamic practice of engaging others to work together through alignment, responsiveness, and modeling [5,33].

3.3. Use of Workshops and Soft Tools

Tools such as vision seminars, joint planning sessions, and workshops were used to varying degrees and with varied effectiveness. These tools were critical platforms for stakeholder open communication, joint planning, and alignment in Project Alpha and Project Bravo. Clarifying roles, establishing mutual goals, and surfacing concerns were attained via facilitated sessions.

Participants noted that the early-phase workshops allowed for the alignment of behavioral and cultural norms beyond technical goals in Project Alpha. The client guaranteed that workshop outputs were integrated into subsequent phases to maintain a link between planning and action. Dialogue exercises, scenario planning, and role mapping seen in Project Bravo workshops were defined by participants as productive and stimulating.

In Project Charlie, however, the workshop process was seen as trickling down and hierarchical. Stakeholders also reported being informed instead of engaged. The workshops in Project Delta were symbolic; there was no sense of shared ownership and no follow-through.

The evidence supports the existing literature highlighting the importance of well-designed workshops in facilitating alignment and enabling stakeholders [12,34]. However, partnering research and VM also show that the design and facilitation of workshops greatly impact mutual purpose and team cohesion [35].

3.4. Comparative Patterns Across Projects

Clear contrasts in how soft values were practiced emerged through cross-case comparison. Finally, Project Alpha and Project Bravo were the standout projects for their strong client engagement, deliberate trust building, and good use of workshops. Stakeholders in both projects reported high expectations, goal alignment, and risk understanding. Furthermore, the transition from planning to implementation had less friction. Members stressed that the client had earlier set the tone for a good and open working environment, ensuring cooperative behaviors.

Conversely, Project Charlie has low leadership involvement, which makes it difficult to maintain communication and a mutual sense of direction among stakeholders. This resulted in delays and a fragmented planning process. In the case of Project Charlie, fragmentation referred to unclear delegation of responsibilities, limited integration between planning and design disciplines, and the absence of structured collaborative arenas. Interviewees reported that key stakeholders operated in silos, and that role expectations were not clearly communicated during the early phase. This led to repeated iterations and rework during the planning stage. While no exact delay figures were disclosed, respondents indicated a setback of approximately 3–4 months in progressing from early-phase collaboration to detailed design. The delay was attributed to slow decision making and the limited visibility of client-side leadership, which hindered alignment and weakened shared ownership among participants.

Project Delta, lacking both leadership and trust building, struggled to coordinate stakeholder interests and ultimately failed to proceed with implementation.

Although all four projects followed the same structural partnering model, the results of these projects varied widely depending on how the model was brought to life through leadership and collaboration practices, which suggests that partnering success is largely behavioral, not contractual. These results suggest that partnering success depends less on formal frameworks and more on behavioral dynamics, especially leadership, trust, and participation.

To illustrate these findings, Table 1 consolidates the performance of each project by key soft-value criteria.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Findings Across Four Anonymous Public Partnering Projects.

As shown in Table 1, the projects with stronger leadership engagement and more deliberate trust-building efforts (Alpha and Bravo) achieved significantly better early-phase collaboration and project continuity. In contrast, the less successful projects (Charlie and Delta) lacked these soft-value foundations, resulting in delays or termination. This reinforces the importance of integrating relational practices alongside structural partnering tools.

The classification of projects as more or less successful in the early phase was based on qualitative indicators identified during analysis, including trust building, leadership engagement, workshop effectiveness, goal alignment, and transition smoothness.

3.5. Negative or Unexpected Findings

Two unexpected findings emerged. First, formal incentive arrangements such as shared savings models or target cost arrangements did not always equal collaborative action. According to the findings of Project Charlie, some of the participants perceived that relational goals and financial incentives were not properly aligned. In Project Delta, the model of incentives was ill-defined and fostered a culture of distrust rather than cooperation. These findings are consistent with studies that show that hard mechanisms are likely to fail if not supported by soft values and can be detrimental if not aligned with the right team culture [15,36].

Furthermore, partnering was often misread. In both Project Charlie and Project Delta, some stakeholders perceived it as a contractual issue, not as a behavioral and cultural issue. This contributed to mere involvement and regression back to the earlier modes of operation that missed trust and cooperation.

Two unexpected findings emerged. First, formal incentive arrangements such as shared savings models or target cost arrangements did not always equal collaborative action. In Project Delta, which did not proceed beyond Phase 1 due to persistent conflicts and disagreements over cost and execution, the incentive model was perceived as ill-defined. Despite adopting an ‘open book’ principle, the client felt they lacked sufficient information about the contractor’s pricing, fostering distrust. Similarly, in Project Charlie, while shared values and goals were established, some participants perceived a misalignment between relational objectives and financial incentives. This perception arose because, despite bonus/malus provisions, the emphasis on strict adherence to budget sometimes overshadowed the collaborative spirit, leading to a focus on financial outcomes that, at times, superseded the relational goals. These findings are consistent with studies that show that hard mechanisms are likely to fail if not supported by soft values and can be detrimental if not aligned with the right team culture.

These results suggest the necessity of early orientation and orientation of partners in a given project, particularly when the concept of collaboration might be either not well established or applied in a rather flexible manner in the context of the public sector.

3.6. Toward a Model of Value-Based Leadership in Partnering

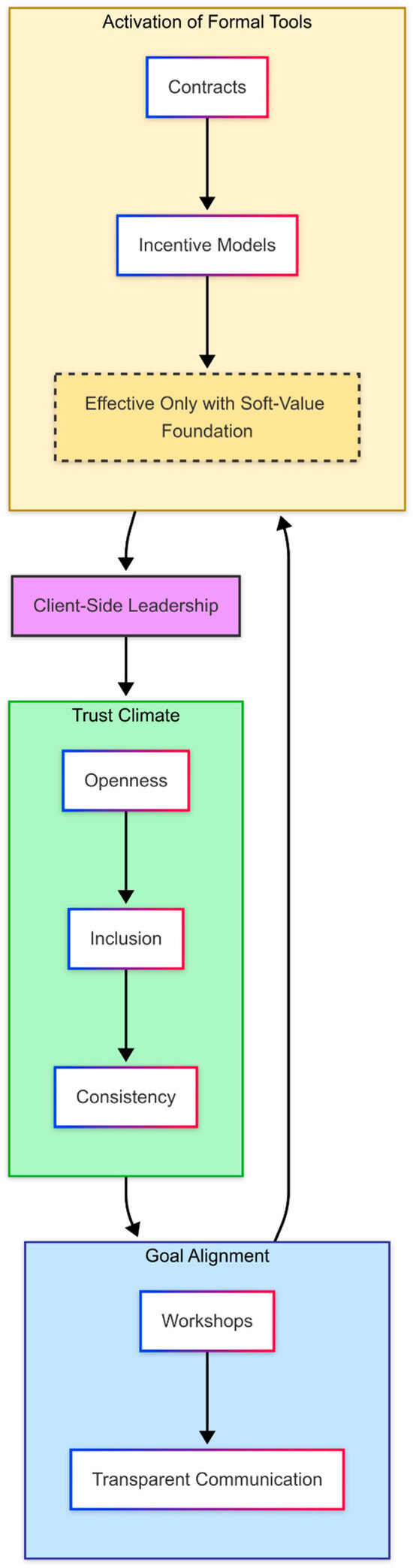

From the four case projects of this study, a cyclical model of value-based leadership on client-side leadership is presented below, which shows how client-side leadership triggers and supports collaboration during the early partnering. The model corresponds to the typical features of best practices: leadership, credibility, involvement in the setting of objectives, and the use of proper instruments.

The model places the client-side leadership in the middle of the process, which reflects its critical role in the formation of the relational and operational environment of the project. Leadership, therefore, expanded its reach through three major domains from this central post:

- Trust Climate is developed through the aspect of Openness, Inclusion, and Behavioral Consistency;

- Corporations and their goals should be aligned with one another through organized and well-coordinated workshops and open communication;

- Some of the contract-based and incentive instruments are only operable when initiated from a platform of shared and trust values.

Contrary to what is represented in the model above, it is not a sequence of steps but a loop with feedback. All the areas interact with one another, and the findings from the results go back to leadership practices. This reflects the process of working on public projects of a certain level of complexity as leadership is not a one-time action, but rather it is a continuous process.

To visually capture the relational dynamics identified in the case studies, Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of value-based leadership in early-phase public partnering projects. The model illustrates how client-side leadership plays a central role in fostering a trust climate, enabling goal alignment, and effectively activating formal tools. These elements interact in a reinforcing cycle, highlighting the iterative nature of collaboration and leadership in complex project environments.

Figure 1.

Value-Based Leadership Loop for Enabling Collaboration in Public Partnering Projects.

The flowchart in Figure 1, illustrates a circular model of value-based leadership for early-stage public partnering projects with a focus on the ongoing interplay among leadership and three critical collaborative domains. Central to the model is client-side leadership, which begins and maintains the process. It initially facilitates the creation of a trust climate that is marked by openness, inclusiveness, and consistency among stakeholders in the project. Such trust foundation fosters successful goal alignment, accomplished through participatory workshops and open communication. Once there are shared objectives, leadership engages formal tools like contracts and incentive models. These tools are only effective if they are found on the soft-value foundation set earlier. Crucially, the process is circular experiments with tools and goal attainment inform and reinforce leadership behavior. The model therefore underscores that collaboration is not linear but a reinforcing loop in which leadership continuously shapes formal mechanisms, communication, and trust that are intertwined with one another. Subgraphs visually group the essential elements of each domain, and color coding facilitates distinguishing their roles, which renders the model useful both analytically and practically for public sector leaders running complex construction projects.

4. Discussion

The findings from this study reinforce international research showing that soft factors including trust, shared culture, and value-based leadership are critical for success in collaborative construction projects. In the early formation phase of public partnering, these elements are especially important for building a shared vision and setting the tone for cooperation. This research supports that hard components (rules, incentives, and formal processes) establish the required structure but are not enough without an underpinning of soft, people-related factors. Such findings are consistent with the previous literature [5,12]. Specifically, the outcomes from these previous studies note that open communication and trust early in a project meaningfully impact stakeholder satisfaction and performance.

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

The research findings obtained from the four cases indicate that client leadership that is proactive and client value-focused is a major key success factor in partnering.

As demonstrated in Projects Alpha and Bravo, formal instruments such as shared savings contracts and early contractor involvement frameworks were most effective when activated through consistent soft-value practices. These included frequent co-location, joint workshops, transparent communication, and leadership modeling of collaborative behaviors. Such efforts helped translate the contractual structure into shared meaning, reducing ambiguity and reinforcing mutual accountability.

While implementing the leadership aspects in Project Alpha and Project Bravo, the following was observed: In such conditions, leaders not only defined what the project was about but also demonstrated actions that encouraged discussion and participation from people. These findings are in line with the value-based leadership theories, which embrace ethical, authentic, and servant leadership behaviors [14,20] and support the argument that such behavior influences the organizations’ performance and culture positively.

On the other hand, Project Charlie and Project Delta illustrated the dangers of low or passive leadership. Major issues that existed in both projects included poor communication, lack of proper expectations, and bad coordination. These findings are consistent with the literature on relational contracting and partnering, where uncertainty of leadership and cultural harmony erode good contractual frameworks [8,19].

The prominence of the role of workshops was also seen. In successful projects, first meetings permitted discussions of expectations and encouraged value co-creation through workshops. Such sessions were participatory and based on open discussions; therefore, they allowed stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of the objectives of the project and the prospective risks. This finding also justifies the assertion in the prior literature that initial-phase workshops are not just technical processes but social processes that are essential for sharing culture and values and building trust [13,37,38].

4.2. Practical Implications

Based on these findings, there are various practical suggestions for public sector organizations looking to enhance collaboration and thereby improve project outcomes:

- Leadership Development: Clients in the public sector ought to invest in development programs that highlight soft skills, such as communication, conflict handling, and moral leadership. All these skills are becoming more realized as key drivers of project achievement, especially where there is working together as previously mentioned by [7,38].

- Improved Workshop Design: Workshops at the early stages must be designed so that they are attended not just by critical decision makers but also by end users, contractors, and designers. As both evidence from practice and the literature such as [34] indicate, inclusive workshops facilitate knowledge sharing, stakeholder empathy, and trust building. An open discussion-based collaborative design may minimize resistance, enhance coordination, and build a sense of joint ownership;

- Balanced Partnering Models: It is essential to balance hard structural aspects (such as contractual terms and incentive schemes) with soft relational aspects (such as interpersonal trust, communication norms, and common values). The value management and lean collaboration literature consistently highlight that the success of formal mechanisms is contingent upon a cooperative mentality and shared commitment [1,37];

- Continual Evaluation: Having feedback loops to evaluate both hard and soft aspects of partnering during the course of the project life can serve to keep everything in line and resolve issues arising. Repeat workshops, pulse-checks, and formal reflection points suggested in some partnering models as also noted by [39], can enhance early-stage successes and avoid relational drift.

By applying these approaches, public sector organizations can greatly enhance project success, minimize conflicts, and maximize long-term value for money. The focus on early involvement and soft values is an expression of the fundamental principles of value management and collaborative delivery, as well as the growing international consensus in the literature that technical tools cannot guarantee project performance, also highlighted by [13,40].

The effectiveness of leadership-based approaches in construction management was evident across the case projects. Where leadership was relational, visible, and value-driven, as observed in Projects Alpha and Bravo, outcomes included stronger trust, clearer goal alignment, and smoother transitions into implementation. These results suggest that leadership approaches grounded in ethical and participatory values can have a meaningful impact on early-phase collaboration. In contrast, in Projects Charlie and Delta, where leadership engagement appeared more limited or less consistent, participants described greater difficulty achieving alignment and continuity, highlighting the importance of proactive leadership in supporting collaborative project environments.

To effectively apply the Value-Based Leadership Loop for Enabling Collaboration in Public Partnering Projects (Figure 1), public sector organizations must prioritize client-side leadership that is actively engaged and value-driven from the outset. This means deliberately cultivating a ‘Trust Climate’ through consistent behaviors, openness, and inclusion, and fostering ‘Goal Alignment’ via well-facilitated workshops and transparent communication channels. Crucially, formal tools like contracts and incentive models, while essential, should be implemented with the understanding that their effectiveness is contingent upon this underlying soft-value foundation. The cyclical nature of the model further underscores the need for continuous leadership engagement and feedback mechanisms to reinforce positive collaborative dynamics throughout the project lifecycle, ensuring that learning from tool activation and goal achievement continuously informs and refines leadership practices.

4.3. Theoretical Contributions

This research presents three main theoretical contributions to the value-based leadership and partnering literature.

To begin, it enlarges the value leadership literature by highlighting how public sector leadership behavior acts as a key in effective partnering. In distinction to much of the literature on private sector dynamics or post-contract collaboration, this study aims to specifically target the early phase, where trust, alignment, and leadership tone are set, as also indicated by [1,41].

Secondly, by utilizing a qualitative, case-oriented methodology, an exploration of knowledge and practice-led learning was feasible. In doing so, the current research contributes to an emergent body of scholarship that seeks to elucidate the operationalization of soft things, specifically high-stakes public sector projects, as also heretofore advocated by [42,43]. Most earlier studies focus on contract design or measurable deliverables, but this study underscores human processes that determine project directions in the background.

Last but not least, the research proposes a cyclical conceptual model whereby client-side leadership facilitates trust climate, goal congruence, and activation of formal instruments. These factors, in turn, loop back to and encourage leadership behavior in the longer term. This circular model provides a novel theoretical framework for conceptualizing collaboration in construction as a system of ongoing relationships and behaviors rather than a linear or phase-bound sequence. This conceptualization challenges researchers and practitioners to go beyond fixed checklists of best practice and instead concentrate on the dynamic interaction of values, actions, and systems [44,45].

Subsequent research may apply or validate this model in other national or industry settings, investigate its use in technology-enabled settings (e.g., BIM-aided partnering), or analyze its application throughout entire project life cycles.

In reinforcing the study’s overall findings, it is evident that the integration of soft skills is crucial for project success in construction. Recent research on public linear infrastructure projects, for instance, identifies communication, leadership, and creativity/curiosity as three main soft skills required for project teams, underscoring the human-centric nature of the industry despite technological advances. Furthermore, studies focusing on soft skills in the broader construction sector highlight existing discrepancies between skills possessed and those required by professionals, emphasizing the need to cultivate abilities such as communication and leadership to enhance overall project performance. This emphasis on behavioral aspects is further supported by investigations into value-based leadership, which demonstrate how such leadership at the frontline positively influences organizational performance and culture [46,47,48].

4.4. Limitations

While insightful, this study is limited in several ways. The study is first conducted in a Norwegian environment that might have limitations in generalizing results across other geographic or market spaces. Cultural and organizational uniqueness within the public projects in Norway might vary distinctly compared to others internationally, particularly within developing countries.

Secondly, the research draws on a relatively small population sample of nine leaders from four projects, potentially missing the diverse range of experience and perception that underlies the involvement of the public sector in construction. Finally, the use of self-reporting data may pose the issue of bias because the participants will offer responses according to social desirability and their own perspectives, rather than hard facts.

4.5. Future Research

With these constraints, some avenues need to be pursued in future research. Longitudinal studies tracing partnering behaviors and partnering outcomes throughout the entire project life cycle would yield a better understanding of the long-term impacts of early-phase interventions. Moreover, incorporating tools like Building Information Modeling (BIM) and sophisticated VM methods into public sector partnering models may provide a better understanding of how process innovation and technology engage with leadership and soft values and as another research documented [13,41]. Lastly, increasing the sample size to incorporate projects from varied geographical locations and industries would aid in the validation of the proposed model and a better understanding of the contributions of soft elements to collaborative construction projects.

5. Conclusions

This study examines how value-based leadership supports effective partnering in public sector construction projects. Drawing from four large-scale Norwegian cases, the findings demonstrate that project success hinges not only on formal structures, but more critically on the quality of early-phase leadership, trust development, and stakeholder alignment. Whereas institutionalized contractual arrangements like incentive models and formal workshops offer critical templates, the operative mechanisms for their effectivity rely heavily on the potency of relationship dynamics facilitated by value-based leadership.

Projects defined by visible, ethical, and genuine leadership demonstrated greater stakeholder trust, alignment, and more effective project handovers. Conversely, poorly led projects in the early stages suffered from communication breakdowns, diminished trust, and less-than-ideal collaborative solutions. This highlights the importance of placing a high emphasis on soft values and relational norms in combination with contractual and structural instruments.

Research envisions a circular model of representing how value-based leadership repeatedly initiates trust climates, facilitates goal congruence, and engages formal mechanisms fruitfully in upholding collaborative achievement. Subsequent research could broaden this exploration in various geographical and organizational settings, further establishing the importance of relational dynamics in collaborative construction contexts. Public sector agencies seeking to maximize project performance need to invest wisely in leadership skills development so that partnering arrangements are grounded in sound interpersonal relationships, common values, and long-term commitment during project life spans.

6. Ethics Statement

This study involved human participants in the form of recorded interviews. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing them with information about the study’s purpose, voluntary nature, and data use. The research was registered with Sikt (formerly NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data), and according to their guidelines, written consent was not required for this type of qualitative research.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, and visualization, O.K.S.; conceptualization, methodology, and data curation, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC (Article Processing Charge) was funded by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study involved interviews with adult professionals about their work in public projects. No sensitive personal data were collected. Verbal informed consent was obtained, and the study was registered with Sikt (formerly NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data), which confirmed that written consent or full ethics review was not needed for this qualitative research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained form all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data were stored on the second author’s personal computer and shared with the first author. They can only be made available upon a necessary and specific request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Galvin, P.; Tywoniak, S.; Sutherland, J. Collaboration and opportunism in megaproject alliance contracts: The interplay between governance, trust and culture. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O.K.; Torp, O. Corrective and Preventive Action Plan (CAPA) for Disputes in Construction Projects: A Norwegian Perspective. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O.K.; Torp, O. CAUSES AND IMPACTS OF DISPUTES IN THE NORWEGIAN CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY WITH GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS. In Proceedings of the 10th IPMA Research Conference: Value Co-Creation in the Project Society, Belgrade, Serbia, 19–21 June 2022; p. 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Pandey, M.K.; Agrawal, S. Conflicts and Disputes in Construction Projects: An Overview. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2017, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygballe, L.E.; Swärd, A. Collaborative Project Delivery Models and the Role of Routines in Institutionalizing Partnering. Proj. Manag. J. 2019, 50, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klakegg, O.J.; Pollack, J.; Crawford, L. Preparing for Successful Collaborative Contracts. Sustainability 2020, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, X.; Nguyen, Q.B.M.; Ma, T.; Gao, S. Soft skills of construction project management professionals and project success factors. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2018, 25, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, S.; Gajendran, T.; Jefferies, M. A systematic review of ‘enablers of collaboration’ in construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 21, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.O.; Wong, W.K.; Yiu, T.W.; Pang, H.Y. Construction Dispute Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebø, A.; Lædre, O.; Young, B.; Larssen, P.F.; Lohne, J.; Klakegg, O.J. Collaborative project delivery methods: A scoping review. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondimu, P.A.; Klakegg, O.J.; Lædre, O. Early contractor involvement in public projects. J. Public Procure. 2020, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Siddharth, S.; Chileshe, N.; Alsolami, B.; Hamed, M.M. Addressing of Value Management Implementation Barriers in Indian Construction: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.M.; Pasquire, C.; Hurst, A. Where Lean Construction and Value Management Meet. 2016. Available online: https://iglcstorage.blob.core.windows.net/papers/attachment-1c650436-241f-4cb2-a1dc-c9b99d608dea.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Emmitt, S.; Sander, D.; Christoffersen, A.K. The Value Universe: Defining a Value Based Approach to Lean Construction. 2005. Available online: https://iglcstorage.blob.core.windows.net/papers/attachment-d9e76cc3-8e3a-4f64-80f4-0bd3cfb93263.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Leung, M.; Yu, J.; Liang, Q. Value Management Techniques, Conflict Management, and Workshop Satisfaction. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 30, 04014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Zhao, X.; Ong, S.Y. Value Management in Singaporean Building Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 31, 04014094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramly, Z.M.; Shen, Q.; Yu, A.T.W. Critical Success Factors for Value Management Workshops in Malaysia. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 31, 05014015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnell, S. Partnering and the Management of Construction Disputes. Disput. Resolut. J. 1999, 54, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux, J.S.; Dority, B.L. Relationship conflict in construction: A literature review. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2020, 38, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.M.; Budhwar, P.; Crawshaw, J. Value-based leadership behavior at the frontline. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Rowlinson, S. The implications of trust in managing construction projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2011, 4, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, S. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data in Mixed Methods Research. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basias, N.; Pollalis, Y. Quantitative and qualitative research in business & tech. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2018, 7, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Somekh, B.; Lewin, C. Research methods in the social sciences. Choice Rev. Online 2005, 42, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB26859968 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Research by Design: Proposition for a Methodological Approach. Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.H.T. Choosing an appropriate research methodology. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1997, 15, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Montoya, M. Interview Protocol Refinement Framework. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, L.; Chakrabarti, A. DRM, A Design Research Methodology; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K. Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C.R. Research Methodology: Methods & Techniques; New Age International: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tabassi, A.A.; Abdullah, A.; Bryde, D. Conflict Management, Team Coordination, and Performance. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 50, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O.K.; Torp, O.; Bruland, A. Resolution of Disputes in Infrastructure Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryger, A. Strategy implementation workshop design. J. Strategy Manag. 2018, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, G. A Systematic Approach to Effective Conflict Management. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejder, E.; Wandahl, S. Partnering Combined with Value-Based Management. 2004. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/da/publications/partnering-combined-with-value-based-management-in-a-building-pro (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Al-Sibaie, E.Z.; Alashwal, A.M.; Abdul-Rahman, H.; Zolkafli, U.K. Conflict factors and project performance. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2014, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oerle, M. Conflict Management in the Construction Industry: A New Paradigm. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Madushika, W.H.S.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Ekanayake, B.; Shen, Q. KPIs of value management in Sri Lankan construction. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, A.; Hewage, K. BIM partnering framework for public construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2013, 31, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building From Cases. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, N.; Shealy, T. Envision Case Study Module. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 05018012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatierra-Garrido, J.; Pasquire, C. Value theory in lean construction. J. Fin. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2011, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, R.K.; Goodrum, P.M.; Taylor, T.R.B. Applying the Tier II Construction Management Strategy to Measure the Competency Level among Single and Multiskilled Craft Professionals. Buildings 2023, 13, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.K.; Posillico, J.J.; Edwards, D.J. Soft Skills for Teams in Public Linear Infrastructure: The Development of a Decision Support Tool. Buildings 2025, 15, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerden, A.; Jelodar, M.B.; Chawynski, G.; Ellison, S. A Study of the Soft Skills Possessed and Required in the Construction Sector. Buildings 2023, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).