Abstract

(1) Objective: This study aims to investigate how transitional housing and the FCBP programme function as infrastructure for improving mental health and building family capacity among low-income households in Hong Kong, introducing the Urban Graduation Approach, adapted from the rural Graduation Approach, as an adaptation of proven poverty-alleviation strategies to urban contexts. (2) Methods: We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 24 residents of transitional housing participating in the Family Capacity Building Planner (FCBP) programme, an important component of The Hong Kong Jockey Club’s Trust-Initiated Project—JC PROJECT LIFT in uplifting residents and enhancing their overall well-being, analysing their experiences through thematic analysis focused on housing transitions, service utilisation, and well-being outcomes. (3) Results: Transitional housing provides essential infrastructure for improving residents’ well-being through both physical improvements and integrated support services. Participants reported significant mental health benefits, with reductions in stress and anxiety directly attributed to increased living space, improved privacy, and better environmental conditions. The FCBP programme functions as soft infrastructure that enables residents to access support networks, enhance family relationships, develop employment skills, and build self-efficacy. Together, these interventions address the multidimensional challenges of urban poverty while fostering sustainable improvements in residents’ capacity to achieve housing security and economic stability. (4) Conclusions: The integration of transitional housing with capacity-building services demonstrates the effectiveness of the Urban Graduation Approach in addressing urban poverty. This model highlights the importance of viewing housing not merely as a physical shelter but as a comprehensive infrastructure for well-being that combines spatial improvements with targeted social support. Policy implications include the need for the continued development of integrated housing models and the scaling of successful elements to broader social housing programmes.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Housing, Health, and Care of Low-Income Households

The impact of housing on physical and mental health, particularly for low-income families, has long been a concern [1,2,3]. Poor housing conditions are generally associated with adverse health outcomes [4], with housing identified as a significant environmental determinant of health [5]. Key housing factors influencing health include cost [6], tenure [7], security [8], environment [7], and living density [9]. The spatial characteristics of housing units play a critical role in determining health outcomes. Unit size significantly impacts mental health, with research showing that insufficient space restricts daily activities, limits privacy, and increases psychological distress [3]. Functional configuration—how spaces are arranged and designated—affects residents’ ability to perform essential activities like cooking, personal hygiene, and sleeping. Poor configurations force compromises in basic functions, creating stress and affecting quality of life [10]. Neighbourhood amenities like health care centres, fresh food markets, and educational facilities also determine access to resources that support healthy lifestyles [11]. Recent studies indicate that housing characteristics such as cost, tenure, and the desire to remain are linked to biomarkers of infection and stress [12]. The effects of housing are both dynamic and long term [13], with cumulative negative consequences over a lifetime [2]. A pathway and life-course approach has been recommended for studying housing impacts [14,15]. Housing factors are interconnected, with affordability influencing quality, tenure, and security, which in turn affect household income and health [16]. Similarly, poor housing conditions are linked to negative mental health outcomes [1]. Factors such as housing stability, precarity [17], affordability [16], and the living environment [18] significantly impact mental health. In industrialised countries, high housing costs and financial constraints are particularly harmful to mental health [19]. The intersection of housing insecurity and poor mental health creates a persistent cycle of disadvantage for low-income urban households. Inadequate housing conditions not only directly impact physical and psychological well-being but also undermine the capacity of families to build the resources and resilience needed to escape poverty. While existing research has examined housing as a social determinant of health, less attention has been paid to how integrated housing and support interventions can simultaneously address multiple dimensions of disadvantage.

The growing influence of neoliberal policy practices has intensified the connections between private housing markets and health care provision. The parallel processes of health care marketisation and housing financialisation reinforce the notion of health care as a market commodity and position housing as a privatised asset base for welfare funding [20]. These practices contribute to the broader individualisation of risk, in which housing is redefined as a financial investment through which individuals are expected to independently manage their lifelong health care needs [21]. As housing investment becomes increasingly embedded in broader policy frameworks, such as pension entitlements and social welfare planning, tenure plays a critical role in shaping access to care opportunities in later life. This dynamic exacerbates socioeconomic disparities, disproportionately advantaging homeowners with higher-value properties while restricting the access of lower-income households to medical and health services. Consequently, this growing inequality not only limits the health care options available to disadvantaged groups but also undermines their overall health and well-being [22].

1.2. The Context of Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the severe public housing supply shortage and escalatory housing prices exacerbate the challenges faced by low-income households, leaving many on the public housing waiting list and forcing a substantial number into subdivided units (SDUs)—housing characterised by small living areas, poor quality, and high rent [23,24]. Drawing on the extended conceptual framework of the 5 Cs (cost, condition, consistency, context, and constitution), Chan [25] reveals that the high rents, cramped spaces, and precarious conditions of SDUs severely impact residents’ physical and mental health. Residents living in SDUs also face numerous living and environmental challenges (Figure 1), including issues like bedbug infestations that negatively affect their health [26,27]. Recent studies in Hong Kong have documented the severe health impacts of housing insecurity and unaffordability. Chung et al. [28] found that housing affordability affects physical and mental health, partially through deprivation, while another study showed that housing quality and neighbourhood quality were associated with mental health [23].

Figure 1.

Internal and external environment of subdivided units: (a) toilets shared by residents of subdivided units; (b) indoor space shared by residents of subdivided units.; (c) stairs of building where subdivided units are located.

Over the past decade, a series of policies, regulations, and intervention programmes have been implemented to alleviate the hardships of low-income families in SDUs. In March 2021, the Tenancy Control Research Working Group submitted a report to the Hong Kong government, proposing a framework for tenancy control to protect the housing rights of SDU residents by capping rent increases and prohibiting landlords from imposing excessive fees for shared facilities. In 2022, the Subdivided Unit Tenancy Control Legislation was enacted. Empirical studies show that the legislation effectively safeguarded the interests of SDU residents and bolstered their confidence by establishing formal lease agreements [29].

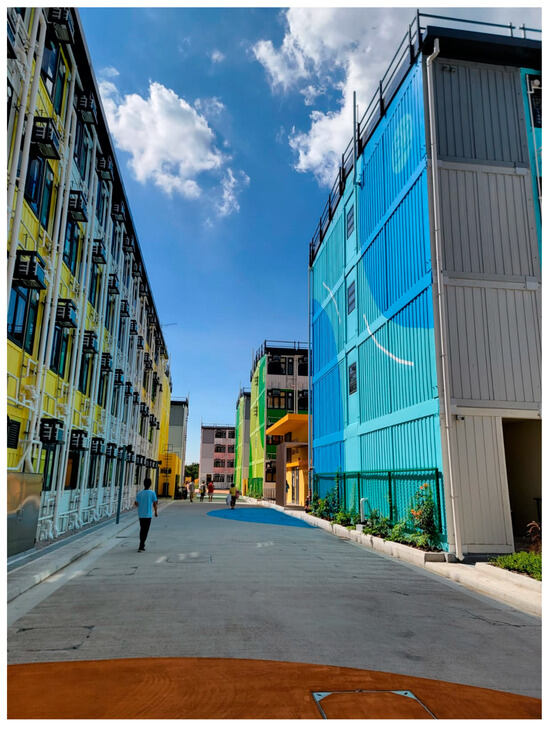

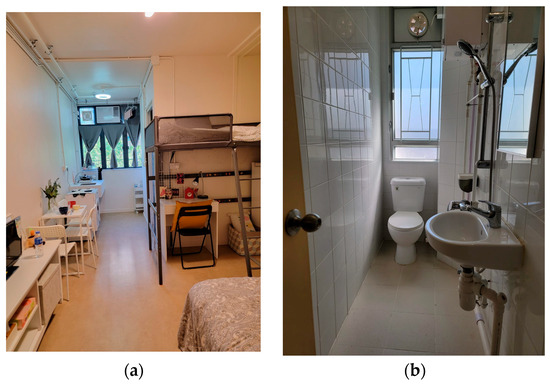

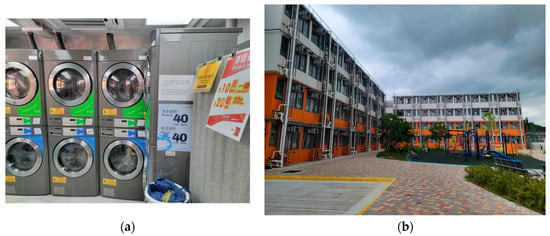

To increase the supply of supportive housing, the Hong Kong government announced community initiatives for Transitional Social Housing (TSH) in the 2017 Policy Address. The Task Force on Transitional Housing was established in 2018 by the Transport and Housing Bureau, and many TSH projects have since been proposed and operated by non-governmental organisations [30]. TSH in Hong Kong represents a distinct housing typology designed to address the immediate needs of low-income households while permanent public housing solutions are developed. TSH typically consists of purpose-built housing units within dedicated buildings or complexes, developed on land with short-term leases granted by the government or private landowners (Figure 2). Physically, TSH projects in Hong Kong encompass diverse configurations. Most commonly, they feature modular, pre-fabricated units arranged in multi-story configurations. Units are typically self-contained with private living space, bathrooms, and small kitchenettes, offering fundamental amenities often unavailable in subdivided housing (Figure 3). Many TSH sites include communal facilities—such as larger kitchen spaces, laundry facilities, and children’s play areas (Figure 4a,b). The main advantages of TSH include improved living conditions, affordability, integrated social services, and community-building opportunities. TSH in Hong Kong operates through a partnership model where non-governmental organisations (NGOs) manage the properties and deliver social services. As of 22 November 2024, the government had identified land for over 21,000 transitional housing units, exceeding the original target of 20,000 units [31]. A longitudinal study of NC202, one of the first TSH programmes in Hong Kong, highlights TSH as an effective intervention for improving residents’ housing circumstances by increasing living area per capita, reducing housing expenses, improving housing conditions, addressing community problems, and enhancing living satisfaction, as well as neighbour and family relationships [32].

Figure 2.

Overview of selected TSH site.

Figure 3.

The inner living space and configuration of TSH unit: (a) TSH residents’ interior space; (b) private toilets and bathrooms in TSH residents’ rooms.

Figure 4.

The communal laundry and playground of TSH: (a) paid laundry facilities in TSH communities; (b) public spaces and recreational facilities within the TSH community.

In Hong Kong, charitable organisations are actively partnering with NGOs to implement a series of social service initiatives aimed at improving the living conditions of residents in transitional housing, uplifting them from poverty, and strengthening their capacity to cope with housing challenges. The Hong Kong Jockey Club’s Trust-Initiated Project—JC PROJECT LIFT pioneers the Urban Graduation Approach (UGA), adapted from the rural Graduation Approach, a proven poverty-alleviation model [33,34], to address urban poverty among families in transitional housing. This initiative empowers these families by enhancing their capacities and fostering sustainable livelihoods through several innovative components. The Urban Graduation Approach is essential due to urban poverty’s unique challenges: higher living costs, distinct livelihoods, and complex social dynamics. Housing issues are particularly severe in cities, where land constraints and market pressures make affordability difficult. Traditional social assistance often falls short, focusing on income support rather than building long-term capabilities. A key feature of JC PROJECT LIFT is the Family Capacity Building Planner (FCBP), which plays a critical role in helping families in transitional housing overcome poverty. The FCBP focuses on developing seven essential family capacities: Caregiving and Empathy, Financial Capability, Health and Well-being, Executive Function, Future Navigation Skills, Social Capital, and Family Mobilisation. Each of these capacities is targeted through tailored interventions designed to meet the specific needs and aspirations of each family, supporting their progress toward economic stability and social well-being. By fostering skills such as financial management, health maintenance, and effective planning, and by strengthening social networks and family unity, the FCBP guides families toward achieving independence and long-term success. With the collaboration of 18 partners and the support of the HKSAR Government’s Housing and Labour and Welfare Bureaus, JC PROJECT LIFT is set to benefit approximately 14,000 families across 25 transitional housing projects.

1.3. Housing as Infrastructure

In recent years, housing and policy research have increasingly embraced the concept of housing as infrastructure, with a growing body of work positioning housing as an infrastructure of care [35,36] and social housing as infrastructure for health, well-being, and economic security [37,38,39]. Amin [40] introduces the concept of the “infrastructural turn”, which emphasises understanding infrastructure as socio-technical systems that organise and shape the possibilities of urban social life, including care and services that improve residents’ health outcomes. Notably, infrastructures exist in a relational context, embodying a “peculiar ontology” in which they are simultaneously “things and the relation between things” [41]. To grasp this dimension, it is useful to conceptualise infrastructures as modal rather than nominal [42], meaning that things become infrastructural when they perform functions within the social world. This perspective highlights the world-building nature of housing infrastructures, suggesting that an infrastructural approach enables researchers to examine how housing contingently supports the health, care, and social lives of its inhabitants in several key ways.

First, understanding infrastructure requires investigating how it underpins practices, intertwining with the world and enabling specific actions. Housing, for instance, organises or patterns possibilities for social practices, making certain practices more or less feasible. This involves identifying the assembled components that constitute housing, including material aspects (such as the housing unit itself) as well as the policies, technologies, and instruments that supply and manage housing services. Second, infrastructures inherently inspire discourses and shape the subjectivities of their inhabitants. Infrastructures “express forms of rule and help constitute subjects in relation to that rule” [43]. They serve as both material and aspirational terrains for “negotiating the promises and ethics of policy-making authority, and the making and unmaking of certain subjects” [44]. Finally, an important perspective on infrastructures involves understanding how they are inhabited. Infrastructures “press into the flesh” [45], representing an intimate point of contact between broader social processes, structures, and daily life.

However, previous studies adopting an infrastructural perspective primarily focus on the hard elements of housing, such as design, space, and materials, and their impact on inhabitants’ health and well-being. The attached social services and supportive networks—widely recognised as critical soft infrastructure within social housing programmes—have been largely overlooked in the existing literature.

To address this gap, our study investigates how transitional housing as a dual infrastructure—encompassing both physical spaces and attached social services—enable low-income households in Hong Kong to access supportive networks and facilities, reorganise physical and mental health practices across household, neighbourhood, and community levels, and exert agency in taking control of their lives and developing self-efficacy. We formulate the following three research questions:

RQ1.

How do the physical features (e.g., unit size, functional layout, communal facilities) of Transitional Social Housing (TSH) influence its residents’ well-being?

RQ2.

To what extent does the Family Capacity Building Planner (FCBP) enhance the capabilities of TSH residents, and how do these capabilities help them uplift from poverty?

RQ3.

How does the integration of TSH with the Urban Graduation Approach (UGA) reconfigure TSH residents’ pathway to achieving sustainable exits from poverty?

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

A qualitative case study was conducted to explore the impacts of transitional housing and its attached social service on low-income residents’ health and well-being. The qualitative case study provides the bottom-up perspective to investigate how the transitional housing unit and its social service operate as infrastructure to empower low-income residents in improving their physical and mental health, enhancing their resilience and well-being, and forming subjectivity with self-efficacy. The qualitative case study was conducted across 4 transitional housing sites under the JC PROJECT LIFT. Twenty-four residents of these 4 transitional housing sites were invited to participate in in-depth, semi-structured interviews in November 2024. Convenience sampling was employed as traditional probability sampling poses practical and ethical challenges (e.g., privacy concerns, distrust of researchers). To mitigate selection bias and enhance diversity, the research team worked closely with social service staff at the transitional housing sites to identify potential participants across varied demographics (age, gender, family structure). Then the research team verified the final selections against the demographic profiles of each TSH site. More importantly, the research team ensured the sampling results reflect the key population characteristics of TSH households in total, including the prevalence of single-mother and elderly households. The demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1. The in-depth, individual interview guide, designed by the first author in collaboration with the research team members, was developed inductively from research objectives/the literature to explore how transitional housing and its associated social services and facilities function as the infrastructure for low-income households to improve their physical and mental health. The interview guide was developed through an iterative process involving research team members with expertise in housing studies, social work, and qualitative methods. More importantly, the research teams piloted the interview guide with experienced social work practitioners to access question clarity and cultural sensitivity, refine sensitive topics, e.g., mental health issues, and establish face validity based on their feedback.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants.

Initial topics and questions were derived from the research objectives and the existing literature on housing transitions and service experiences. The interview guideline encompasses questions relevant to research participants’ previous living experiences in SDUs, the changes in terms of health, well-being, and sense of self-sufficiency after moving to transitional housing, their feedback toward transitional housing unit, its facilities, environment, and attached social services.

Before the interviews, the purpose of the research was explained to the participants, and they were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. During the semi-structured interviews, participants were asked to share their demographic information (e.g., age, gender, educational background, occupation, marital status, family structure, housing status and type prior to moving into transitional housing, and the duration of their stay). They were also invited to describe their physical and mental health, lifestyle, life changes after moving into transitional housing, and their attitudes toward the facilities and social services at the sites. Interviewing ceased at n = 24 after reaching thematic saturation, evidenced by three consecutive interviews yielding no new codes in preliminary analysis, stabilisation of code frequencies across capacity-building (FCBP) and infrastructure themes, and peer debriefing confirming A comprehensive coverage of research question domains. Each interview in Cantonese was transcribed and lasted between 30 and 60 min. Participants received a HKD 100 supermarket coupon as compensation for their time. The in-depth, semi-structured interviews are a critical component of the study, which was approved by the Human and Artefacts Ethics Sub-Committee of the City University of Hong Kong (HU-STA-00000989) on 9 May 2023. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before the interviews.

2.2. Research Team Positionality: Credibility and Trustworthiness

Researchers’ positionality and identities shape how they engage in a study, how they interact with research participants, and how they analyse and interpret the research findings. The research team comprised a social work professor with extensive experience providing support and social services to disadvantaged populations, including poor households living in SDUs and homeless individuals. Another team member is a scholar with research experience focused on migrant workers within the context of rapid urbanisation. A third member is a researcher with training in psychological counselling to various disadvantaged groups, particularly individuals with mental health issues and immigration backgrounds. Collectively, the researchers hold the belief that all individuals deserve safe and secure places to live and belong, which informs their commitment to this research. The team acknowledges the potential influence of their positionality and actively seeks to mitigate biases. To enhance credibility and trustworthiness throughout the analytical process, the research team employed triangulation through multiple coders, prolonged engagement, and peer debriefing [46]. Having a three-person analysis team enabled triangulation, which often involved discussions and debates to achieve a shared understanding. Prolonged engagement with residents of transitional housing allowed the researchers to build deeper relationships with participants and more profoundly understand their experiences.

2.3. Data Analysis

An analytical framework was developed to guide the study, comprising questions related to participants’ living experiences before and after transitional housing, their attitudes toward the facilities and social services available at the transitional housing sites, and the changes in their physical and mental health. These questions aimed to capture the nuanced ways in which transitional housing influenced their daily lives and well-being. Adhering to the principles of thematic analysis [47], we systematically analysed the interview transcripts using open and focused coding to identify key themes, patterns, and similarities or differences across participants’ narratives. During the open coding phase, two researchers independently reviewed transcripts line-by-line, identifying initial codes without predetermined categories. In the subsequent focused coding phase, these initial codes were consolidated into broader conceptual categories through team discussions that identified recurring patterns and theoretical relationships. Special emphasis was on exploring participants’ reflections on their lived experiences and understanding how transitional housing and site-based infrastructure shaped their physical health, mental well-being, and lifestyle choices. This approach allowed us to delve deeper into the interconnected impacts of transitional housing on various aspects of participants’ lives.

3. Empirical Findings

3.1. Transitional Housing as Infrastructure for Protecting Personal Safety and Privacy

Our research participants shared that transitional housing programmes provide them with more decent and stable living conditions. Compared to their previous unstable and unsafe accommodations, transitional housing serves as vital infrastructure that ensures their personal safety by shielding them from various hazardous factors.

“Our flat in transitional housing programme is much safer than our previous temporary squatter. During last year’s torrential black rainstorm, our home was directly flooded, causing extensive damage to our furniture and many household items. Because of living in temporary squatter, I had to cook outdoors, which exposed us to numerous mosquito bites, leaving our legs swollen and covered in welts. Additionally, we faced threats from venomous snakes and insects. Moreover, wild boars were also a significant hazard. One day after a heavy rain, the weather cleared around 10 am. We came out and noticed a wild boar near our squatter. It was the most dangerous time in my life”.(Case 15, Female, Unmarried, 20, Senior High School)

Participants also highlighted that the transitional housing programme provides essential living infrastructure that safeguards their personal privacy and freedom, which were often violated in overcrowded spaces such as SDUs. These improvements in privacy and freedom have significantly contributed to enhancing their mental well-being.

“Overall, the improvements in privacy and sleeping conditions have made us much more comfortable, and we now enjoy greater personal freedom and privacy”.(Case 1, Male, Unmarried, 31, Undergraduate)

Some participants living with children emphasised that transitional housing offers infrastructure that protects their children’s privacy and personal space, which is crucial for adolescents’ healthy development and physical and mental well-being.

“Now, my son has a desk to write and read, although the overall environment is still not ideal. At least he has a small private space where he can sit down and do his own things… which was not possible before”.(Case 2, Female, Married, 50, Junior High School)

“My children and I have private space to sleep separately, which is a significant improvement. This living privacy is also more beneficial for their mental and physical developments during adolescence”.(Case 12, Female, Divorced, 40, Undergraduate)

Additionally, some participants noted that the relatively affordable rent of transitional housing has alleviated their financial burden, enabling them to allocate more resources toward other needs, such as nutritious groceries, to improve their overall quality of life.

“Our rent expenses were significantly lower after moving to there [transitional housing site]. Now I can spare a large portion of living expense to buy fruits, milk and other food supplements to improve children’s health”.(Case 7, Female, Divorced, 47, Tertiary Education)

3.2. Transitional Housing as Infrastructure for Promoting Mental and Physical Health

Research participants shared that, before living in transitional housing, they experienced significant mental health challenges due to the oppressive living conditions in their previous homes. Some participants even developed mental illnesses, such as depression, during the COVID-19 lockdown when confined to cramped spaces for extended periods.

“[I lived in subdivided unit in last five years…] I always had to keep the lights on during the day. The three years of the pandemic made me feel very oppressed and emotionally unstable when being forced to stay in such tiny space. Owing to the living issue, family issue and other problem, I had to see a psychiatrist regularly even now I have to receive follow-up treatments every four months”.(Case 13, Female, Divorced, 53, Tertiary Education)

Research participants indicated that the housing units in transitional housing have more adequate sun exposure and better aeration, which provides them with a more comfortable living environment and consequently leads to improved physical and mental health.

“After moving to my current unit [of transitional housing], which has large windows, I receive ample sunlight and improved air circulation. The room is also significantly larger than my previous one. I find my living conditions here much more comfortable, and my overall mental health has greatly improved”.(Case 13, Female, Divorced, 53, Tertiary Education)

Research participants also reported that, in addition to better sun exposure and aeration, the units of transitional housing normally have larger living spaces compared to their previous accommodations in SDUs. The increased living space allows them to arrange their daily activities more freely according to their preferences, which in turn helps improve their mental health.

“The environment is significantly better than before, as the bathroom is twice as large as my previous one. I prefer having a larger bed. The air quality is also improved. With the increased space, I can now arrange my daily life more freely, such as deciding when to rest and what activities to participate in. Overall, my attitude towards life has become more positive”.(Case 6, Female, Widow, 51, Senior High School Education)

Research participants also indicated that the units in transitional housing have better functional configurations, such as separate bathrooms and kitchens. These improved, independent functional configurations enable them to maintain a more hygienic and stable daily life, thereby enhancing their physical and mental health.

“[After moving to transitional housing] I have a private bathroom and kitchen, eliminating the need to use communal, outdoor cooking and bathing facilities as I did before. The hygiene of my daily life has greatly improved, which has significantly enhanced my psychological well-being since moving in. I no longer feel as anxious and uneasy as I did previously”.(Case 15, Female, Unmarried, 20, Senior High School)

3.3. FCBP Intervention as Infrastructure for Enhancing Health and Well-Being

Participants also highlighted the support by the FCBP teams at transitional housing sites. These teams provide targeted classes and workshops addressing common mental health challenges faced by residents. These initiatives act as soft infrastructure that effectively enhances residents’ understanding and skills for managing their mental well-being.

“Regarding our emotional and mental health issues, they offer different sorts of targeted classes and workshops. They will also follow up if we have any mental issue or concern. Therefore, living here definitely makes me feel more cheerful and at ease in daily lives”.(Case 12, Female, Divorced, 40, Undergraduate)

Furthermore, the enhanced awareness and skills regarding physical and mental health have encouraged participants to actively engage with the ample and easily accessible recreational and cultural facilities available at the transitional housing sites. These facilities have supported participants in maintaining healthy lifestyles and well-being. Many participants reported that regular physical exercise and other healthy habits have become integral parts of their daily routines.

“I gradually developed the habit of doing exercise every day. Every day, I go jogging, stretching and practice yoga. Overall, I really enjoy nice environment there to do exercise every day and have a healthy lifestyle”.(Case 4, Male, Married, 50, Graduate)

3.4. FCBP Intervention as Infrastructure for Promoting Family Communication and Harmony

Research participants recognised that the FCBP teams in transitional housing play a significant role in organising various activities, such as after-school childcare services. These services help alleviate the pressure of childcare on families, foster improved family communication, and enhance family members’ understanding and skills for maintaining harmonious relationships. Acting as soft infrastructure, these family-focused initiatives effectively contribute to building harmonious and mutually supportive family dynamics within transitional housing communities.

“My primary challenge has been taking care of my two children, especially since there was no one to care for them after school. Fortunately, the FCBP promptly provided after-school care services. They [FCBPs] not only take care of children but also instill a sense of responsibility and understanding toward their parents among them. For example, FCBPs encourage older children to look after the younger ones. Over time, I observed that my children began to communicate with me more frequently and developed a stronger sense of responsibility toward our household”.(Case 12, Female, Divorced, 40, Undergraduate)

Participants also reported that transitional housing, compared to their previous overcrowded and harsh living conditions, provides more spacious accommodations with access to communal facilities such as kitchens and televisions. These improved living environments, combined with FCBP interventions, have reduced the risk of family conflicts by creating a more supportive atmosphere for family relationships.

“I developed anxiety due to postpartum depression and prolonged quarantine with my daughter in a confined rooftop subdivided unit during the pandemic. My mental issue led to frequent arguments with my husband over minor disagreements, sometimes escalating to the point of breakdowns, which eventually resulted in referrals to family centre social workers. After moving to transitional housing site, we now raise the importance of nurturing a harmonious environment for our family. When conflicts arise with my husband again, I walk out to public space or park near our housing site and use the knowledge I learned from workshops to calm myself down. We try to maintain a peaceful environment for my daughter, shielding her from our disputes”.(Case 5, Female, Married, 35, Undergraduate)

3.5. FCBP Intervention as Infrastructure for Coping with Poverty-Related Adversities

Research participants shared that living in poverty often leads to marginalisation and social isolation, which limit access to resources and information, trapping individuals in a cycle of poverty. This isolation also negatively impacts physical and mental well-being. However, the FCBP teams attached to transitional housing programmes addressed these issues by offering employment-related guidance and follow-up services. Participants noted that unemployment and underemployment are common challenges they face. In response, the FCBP teams provided timely support and counselling to help residents regain their confidence and re-enter the workforce.

“At that time, I was unemployed and so depressed, so I went travelling. Then they [FCBP] knew that I had been laid off and did follow-up immediately. They comforted me and then gave me advice to restore my confidence first”.(Case 10, Female, Married, 51, Junior High School)

Participants emphasised that the guidance and support of the FCBP teams act as essential infrastructure, helping them realise their potential and improve their overall employability. This includes building confidence, acquiring new knowledge, and developing skills to secure stable employment, ultimately breaking free from the cycle of poverty and addressing associated health risks.

“I feel that they [FCBP] work together to help me find employment. For instance, if I think a job is not suitable, they will immediately follow-up, listen attentively to my feedback and provide effective advice. If I were on my own, I might feel scared or uncertain, but having more people involved gives me more confidence and useful information”.(Case 3, Female, Unmarried, 28, Senior High School)

Some participants further highlighted how poverty-related marginalisation and isolation have undermined their physical and mental health, leaving them without effective support networks to handle daily challenges. The services of the FCBP teams enabled residents to access immediate assistance, helping them cope with adversities and uncertainties in daily life, which improved physical and mental well-being.

“She [FCBP] is very attentive and patient when listening to us, and she often provides advice on various issues I encountered in daily life. Her assistance has indeed been very helpful”.(Case 12, Female, Divorced, 40, Undergraduate)

“They [FCBP] help me address issues I encounter in my daily life and work, always ready to lend a hand whenever needed”.(Case 2, Female, Married, 50, Junior High School)

3.6. FCBP Intervention as Infrastructure for the Formation of Subjectivity with Self-Efficacy and Resilience

Research participants shared that the FCBP teams in transitional housing helped them understand the importance of self-sufficiency and resilience by offering various forms of support. Rather than relying solely on government welfare and subsidies, participants expressed a growing preference for achieving economic self-reliance by exploring their own potential and developing their abilities. For instance, some participants who previously depended on Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) now plan to open savings accounts to regularly set aside money and work toward economic independence.

“Due to my previous reliance on CSSA, it was difficult to save a significant amount. However, as I begin my job search and decide to achieve self-reliance, I plan to establish a stable savings plan”.(Case 3, Female, Unmarried, 28, Senior High School)

Participants further acknowledged that the training and services by the FCBP teams act as soft infrastructure that fosters the development of self-efficacy. This is characterised by confidence, motivation, and a sense of agency, enabling participants to uplift themselves from poverty by pursuing permanent employment and opportunities for self-development.

“I am currently attending classes, taking training courses to become an occupational therapy assistant. I have discovered that there is a lot to learn, and I find it very interesting. There are also other things you can do if you have motivation and plan”.(Case 10, Female, Divorced, 51, Junior High School)

“I think they [FCBPs] help many families, including mine, to have hope and confidence to uplift ourselves from the poverty regarding material and mental dimensions by our own efforts. They will be there and ready to help us”.(Case 11, Male, Married, 34, Undergraduate)

Some participants also emphasised that FCBPs have created an environment conducive to building self-efficacy, which not only benefits individuals but also motivates other family members to pursue their own self-development.

“In my career planning, my ultimate goal is both having a better career path and setting a good example for my two sons. I hope I can show them the importance of being an independent, hard-working people”.(Case 12, Female, Divorced, 40, Undergraduate)

In summary, the supportive services by the FCBP teams served as soft infrastructure that enabled transitional housing residents to develop a strong sense of self-efficacy. With a positive, future-oriented mindset and resilience, these residents gained higher confidence and formulated concrete plans for the sustainable development of themselves and their families.

3.7. FCBP Intervention as Infrastructure to Develop Harmonious Community Life

Research participants described how the FCBP teams in transitional housing organised various community events, such as the Mid-Autumn Festival Gala Show and Halloween Cosplay Show. These activities provided opportunities for residents to build relationships with neighbours, fostering a sense of community and social connection. These connections, in turn, offered emotional support and practical help, such as sharing meals or assisting with household tasks, which contributed to improved subjective well-being.

“They [FCBPs] have done a lot to boost the communication and mutual support among us. They really strive to construct our community like a collective. I noticed that nearly all residents take great pride in the environment. Our residents also contribute to maintaining high standards of hygiene and developing a strong sense of care and love”.Case 1, Male, Unmarried, 31, Undergraduate)

“Through participating in community activities, I have become friends with several neighbours. Sometimes, someone cooks a meal or makes soup, and we all gather to share the food. I have also cooked and made soup for others in their homes”.(Case 19, Male, Divorced, 63, Junior High School)

Participants also reported that, with the community built by the FCBP teams, they have been able to utilise public spaces and facilities within the transitional housing sites to meet neighbours and strengthen their sense of community attachment.

“After moving there [transitional housing site], we have more opportunities and places to meet different neighbours, develop connections and even friendship with them. In the past, we can do nothing but stay at home to play smartphone or watch TV. I feel like that human beings should not be isolated individuals, rather, they should thrive within a community. The atmosphere here encourages me to meet more people, engage in conversations and community activities, and ultimately enhances our well-beings in the community”.(Case 11, Male, Married, 34, Undergraduate)

4. Discussions

This study aimed to examine how transitional housing and integrated support services with UGA function as infrastructure for improving mental health and building family capacity among low-income households in Hong Kong. Our findings demonstrate that transitional housing, combined with the FCBP intervention, serves as a comprehensive infrastructure that addresses multiple dimensions of disadvantage experienced by low-income families. This integrated approach not only provides immediate relief from substandard housing conditions but also creates pathways for sustainable advancement through capability development and community building. In Hong Kong, the acute shortage of public housing and escalating housing prices have exacerbated the severe housing challenges faced by low-income families, forcing many to live in suffocating environments such as SDUs, which detrimentally affects their physical and mental health [29]. The empirical findings of our study reveal that transitional housing, combined with site-based social service programmes—in this case, the FCBP—functions as essential infrastructure for alleviating poverty and enhancing the mental health and overall well-being of poor households.

Our study reveals that transitional housing programmes provide a more stable and decent living environment, functioning as hard infrastructure that ensures the safety and privacy of residents from low-income households. This housing stability, characterised by increased living space and adequate facilities, establishes the preconditions necessary for low-income households to escape the risks and adversities associated with their previous suffocating living environments, such as SDUs. This finding aligns with the previous literature, which highlights the critical role of housing in shaping social life and health outcomes [40,41]. It further emphasises the effectiveness of social housing programmes, including transitional housing, in improving the living conditions and overall well-being of low-income households [32]. Additionally, our study demonstrates that the more affordable rent of transitional housing has significantly alleviated the financial burden of housing costs, enabling residents to explore opportunities for enhancing their employability and overall well-being. This finding aligns with the recent literature on the effectiveness of rent control measures, such as SDU tenancy control, in safeguarding the interests of low-income households and increasing their housing stability [29]

Rather than assuming that decent housing automatically resolves multifaceted adversities, including psychological distress [40,41], our study findings show that TSH as the hard infrastructure is insufficient in addressing the challenges from housing instability until the FCBP intervention began. Our study further sheds light on the role of the FCBP intervention, an indispensable component of the JC PROJECT LIFT, as soft infrastructure that enhances the capacities of low-income households to cope with the multifaceted adversities of poverty identified in previous studies [32]. Our empirical findings indicate that the FCBP programme effectively addresses common mental health challenges by organising targeted lectures and workshops. These initiatives improve residents’ understanding and skills in managing their physical and mental health. Additionally, by providing various supportive services aimed at improving residents’ employability, family communication, and community attachment, the FCBP programme serves as soft infrastructure that fosters the development of self-efficacy and resilience among transitional housing residents. This finding aligns with the infrastructure perspective, which emphasises the role of social housing infrastructure in shaping subjectivities and enabling specific actions [43,44]. Furthermore, our study highlights the UGA, adapted from the proven success of the rural Graduation Approach in poverty alleviation, as a valuable framework in this context. The UGA, when integrated with the FCBP programme, exemplifies a comprehensive strategy for enabling low-income households to transition out of poverty. By addressing immediate needs and simultaneously building capacities for long-term self-reliance, the UGA demonstrates its effectiveness in urban settings like transitional housing. The combination of transitional housing with FCBP intervention serves as a compelling showcase of the UGA in action. This holistic approach to health and well-being underscores the importance of integrating site-based social service interventions with transitional housing facilities to create a supportive environment for low-income households, not only addressing their immediate challenges but also equipping them with the tools for sustainable development and resilience. The Urban Graduation Approach in Hong Kong offers insights for other urban cities but depends on institutional coordination and resources. Key elements, such as combining housing stability with capability development, remain adaptable across settings. While specific mechanisms may vary, the core principle of integrated support is universal. The graduated support model, which builds skills and reduces assistance over time, is particularly transferable for poverty reduction in diverse urban contexts.

This study further contributes to the infrastructure perspective in housing studies by emphasising the role of social service programmes as soft infrastructure in improving the health and well-being of low-income households. Traditionally, housing studies have focused on the physical aspects of housing infrastructure, such as design, space, and materials. However, our findings demonstrate that social service programmes are equally critical in providing support and care for the health of low-income households. The theoretical framework emphasises the need to view infrastructure as socio-technical systems that organise and pattern possibilities for social practices [40,42]. The previous literature noted that the parallel processes of health care marketisation and housing financialisation reinforce the notion of health care as a market commodity and position housing as a privatised asset base for welfare funding, disadvantaging individuals and households who cannot afford the housing investment [20,21]. Our findings reveal that the FCBP programme, as soft infrastructure, has challenged the neoliberal trend of health care by enabling residents to access supportive networks and facilities, reorganise mental health care at various scales, and exert agency in co-creating care networks through FCBP-facilitated peer groups. Our finding directly challenges the neoliberal narratives of disadvantaged groups as passive welfare recipients. This bottom-up care reorganisation supported by the FCBP programme represents a divergence from top-down models in existing infrastructure scholarship [43,44]. Moreover, our study further transcend the dichotomous hard/soft infrastructure frameworks [40,42] by revealing their entanglement in uplifting low-income households from poverty-related adversities.

In the Hong Kong context, the success of transitional housing with integrated support services suggests several specific policy directions. First, the government may consider extending the maximum tenancy period for transitional housing or light public housing for families demonstrating progress toward self-sufficiency but requiring additional time to secure permanent housing. Second, elements of the FCBP programme and UGA could be systematically incorporated into existing public housing estates, particularly in estates with high concentrations of vulnerable households. This would extend the benefits of integrated support beyond transitional housing and create more sustainable community infrastructure. Third, the government may develop well-designed pathways for transitional housing residents to public housing allocation, recognising their demonstrated capacity for successful tenancy. Fourth, the successful community-building aspects of transitional housing should inform the design of future housing developments, with greater attention to communal spaces and facilities that foster social connection.

Finally, the findings of this study underscore the necessity of aligning site-based social service programmes with broader policy interventions aimed at uplifting low-income households from poverty and promoting social equality. Over the past decade, various policies and regulations have been implemented in Hong Kong to address housing challenges for low-income households, such as the Subdivided Unit Tenancy Control Legislation and the TSH initiatives [29]. By integrating social services with broader poverty-alleviation policies, we can create a more comprehensive approach that not only provides immediate support but also contributes to long-term solutions, enhancing the quality of life for low-income individuals. This integrated approach is vital for achieving sustainable social and economic development, offering a pathway toward greater social equality and improved living standards for vulnerable communities.

This study has several methodological limitations that warrant consideration. First, convenience sampling may introduce selection bias by potentially overrepresenting participants with stronger engagement in FCBP services. Second, retrospective self-reports of pre-transition experiences carry inherent recall and social desirability biases. Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal claims about TSH/FCBP impacts and the absence of a comparative component prevents the isolation of TSH’s unique effects. Therefore, future study should employ longitudinal mixed methods to triangulate the self-reported data and track residents post-transition to assess the sustainability of the outcomes. Meanwhile, conducting a comparative study with public housing estates or market rentals with equivalent support social service is also suggested.

5. Conclusions

Our investigation of transitional housing and the Family Capacity Building Planner programme has yielded important insights into addressing urban poverty in high-density environments. First, we advance the “housing as infrastructure” framework by revealing transitional housing as relational infrastructure—a dynamic synthesis of hard and soft elements. Unlike prior conceptualisations treating physical spaces and social services separately [40,42], we demonstrate how TSH units and FCBP programmes mutually reconfigure each other. Hard infrastructure becomes “activated” only when paired with FCBP intervention. Soft infrastructure gains spatial embeddedness, using housing sites as platforms to reorganise care from household to community. This challenges dichotomous models and offers a new lens for evaluating integrated social-housing-attached interventions. Second, we establish the Urban Graduation Approach’s efficacy in high-density settings through contextual recalibration. Where rural Graduation Approaches prioritise physical asset transfers [33], Hong Kong’s spatial and market constraints necessitate shifting to the capacity building of low-income households, including their executive function, social capital development, and future navigation skills, which might be important to tackle urban poverty in other high-density contexts, i.e., Singapore, New York, and Tokyo. For policymakers, our results demonstrate that physical housing improvements must be coupled with social support systems to achieve sustainable outcomes. For service providers, our findings highlight housing stability as a foundation for effective intervention, indicating that service delivery should be coordinated with housing solutions. Our study’s theoretical contribution lies in reconceptualising both housing and social services as interconnected infrastructure that enables human flourishing. This perspective extends beyond traditional views of housing as merely physical shelter, revealing how improved living environments and targeted support create new possibilities for well-being, agency, and social inclusion. The demonstrated effectiveness of the UGA in Hong Kong also shows how rural poverty-alleviation approaches can be successfully adapted to dense urban settings with appropriate modifications.

Author Contributions

S.-M.C.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Research Design and Data Collection, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration; H.X.: Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, and Formal Analysis; Y.-K.T.: Formal Analysis, Investigation, and Writing—Review and Editing; K.K.: Writing—Review and Editing; Mandy K.-M.L.: Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust (Grant number: 2023-0135-016).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Human and Artefacts Ethics Sub-Committee (HU-STA-00000989) on 9 September 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The study is part of a comprehensive evaluation study of JC PROJECT LIFT, an initiative created and funded by The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. We extend our sincere gratitude to The Hong Kong Jockey Club for their visionary leadership in implementing the Urban Graduation Approach and creating the innovative Family Capacity Building Planner (FCBP) 家庭能力顧問® intervention—a pioneering initiative designed to alleviate poverty in Hong Kong. To learn more about the project, please visit: https://jcprojectlift.hk/en/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, A.; Daniel, L.; Baker, E.; Bentley, R. Housing Disadvantage and Poor Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Crane, J.; Baker, M.; Viggers, H.; Chapman, R.; Cunningham, C. Health, well-being and housing. Int. Encycl. Hous. Home 2012, 2, 344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Wells, N.M.; Moch, A. Housing and Mental Health: A Review of the Evidence and a Methodological and Conceptual Critique. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M. Housing and Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 25, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braubach, M. Key Challenges of Housing and Health from WHO Perspective. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 579–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.E.; Griffin, B.A.; Lynch, J. Housing Affordability and Health among Homeowners and Renters. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. Housing tenure and the health of older Australians dependent on the age pension for their income. Hous. Stud. 2018, 33, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, E.; Dodge Francis, C.; Gerstenberger, S. Where I Live: A Qualitative Analysis of Renters Living in Poor Housing. Health Place 2019, 58, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.J. Health risks: Overcrowding. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy, X. Indoor air quality and health: New evidence and challenges for our changing climate. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, R.; Green, D.; Guijt, I.; Walsh, M.; English, R.; Cairney, P. Using Evidence to Influence Policy: Oxfam’s Experience. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, A.; Hughes, A. Housing and Health: New Evidence Using Biomarker Data. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, A.; Gordon, D.; Heslop, P.; Pantazis, C. Housing Deprivation and Health: A Longitudinal Analysis. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piat, M.; Polvere, L.; Kirst, M.; Voronka, J.; Zabkiewicz, D.; Plante, M.-C.; Isaak, C.; Nolin, D.; Nelson, G.; Goering, P. Pathways into Homelessness: Understanding How Both Individual and Structural Factors Contribute to and Sustain Homelessness in Canada. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2366–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuhara, M. Life-Course Diversity, Housing Choices and Constraints for Women of the ‘Lost’ Generation in Japan. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Mason, K.; Bentley, R.; Mallett, S. Exploring the Bi-Directional Relationship between Health and Housing in Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2014, 32, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, A.; Nisenbaum, R.; Kopp, B.; O’Campo, P.; Hwang, S.W.; Stergiopoulos, V. Are Resilience and Perceived Stress Related to Social Support and Housing Stability among Homeless Adults with Mental Illness? Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, N.; Filatova, S.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Miettunen, J. Living Environment and Its Relationship to Depressive Mood: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, M.W.Y.; Hui, E.; Zheng, X. Residential mortgage default behaviour in Hong Kong. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doling, J.; Ronald, R. Home Ownership and Asset-Based Welfare. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2010, 25, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.M. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Power, E.R. Housing, Home Ownership and the Governance of Ageing. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.M.; Chan, W.C.; Chu, N.W.T.; Law, W.Y.; Tang, H.W.Y.; Wong, T.Y.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Lam, L.C.W. Individual and Interactive Effects of Housing and Neighborhood Quality on Mental Health in Hong Kong: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Urban Health 2024, 101, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, Y.; Yip, K.C. No More Illegal Subdivided Units? A Game-Theoretical Explanation of the Failure of Building Control in Hong Kong. Buildings 2022, 12, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.M. Unhealthy Housing Experiences of Subdivided Unit Tenants in the World’s Most Unaffordable City. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2023, 38, 2229–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, E.H.C.; Chiu, S.W.; Lam, H.-M.; Chung, R.Y.-N.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Chan, S.M.; Dong, D.; Wong, H. The Impact of Bedbug (Cimex Spp.) Bites on Self-Rated Health and Average Hours of Sleep per Day: A Cross-Sectional Study among Hong Kong Bedbug Victims. Insects 2021, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, E.H.C.; Wong, H.; Chiu, S.W.; Hui, J.H.L.; Lam, H.M.; Chung, R.Y.; Wong, S.Y.; Chan, S.M. Risk Factors Associated with Bedbug (Cimex spp.) Infestations among Hong Kong Households: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 1411–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-T.W. The Issue of Subdivided Units in Hong Kong: Licensing as a Solution? Ph.D. Thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.-M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, A.; Tang, Y.-K.; Au-Yeung, T.-C.; Tam, N.W.-Y. The Impact of Tenancy Control on Housing Precarity in Hong Kong: A Panel Study of Subdivided Unit Residents. Cities 2025, 158, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region—Meeting Papers. Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/en/legco-business/committees/meeting-papers.html?panels=housing&2024&20240603 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Housing Bureau—Policy—Housing—Transitional Housing—Transitional Housing Projects. Available online: https://www.hb.gov.hk/eng/policy/housing/policy/transitionalhousing/transitionalhousing.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Chan, S.-M.; Wong, H.; Au-Yeung, T.-C.; Li, S.-N. Impact of Multi-Dimensional Precarity on Rough Sleeping: Evidence from Hong Kong. Habitat. Int. 2023, 136, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Sharma, G. Long-Term Effects of the Targeting the Ultra Poor Program. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2021, 3, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Nisat, R.; Das, N. Graduation Approach to Poverty Reduction in the Humanitarian Context: Evidence from Bangladesh. J. Int. Dev. 2023, 35, 1287–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.R.; Wiesel, I.; Mitchell, E.; Mee, K.J. Shadow Care Infrastructures: Sustaining Life in Post-Welfare Cities. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 1165–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.R.; Mee, K.J. Housing: An Infrastructure of Care. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, T.L.; Power, E.R. Conceptualising Housing as Infrastructure: A Framework for Thinking Infrastructurally in Housing Studies. Hous. Stud. 2025, 40, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Martin, C.; Jacobs, K.; Lawson, J. A Conceptual Analysis of Social Housing as Infrastructure; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, J.; Troy, L.; van den Nouwelant, R. Social Housing as Infrastructure and the Role of Mission Driven Financing. Hous. Stud. 2024, 39, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A. Lively Infrastructure. Theory Cult. Soc. 2014, 31, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, B. The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2013, 42, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, D. Infrastructure, Potential Energy, Revolution. In The Promise of Infrastructure; Anand, N., Gupta, A., Appel, H., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018; pp. 223–244. ISBN 978-1-4780-0203-1. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, B. Promising forms: The political aesthetics of infrastructure. In The Promise of Infrastructure; Anand, N., Gupta, A., Appel, H., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018; pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, H.; Anand, N.; Gupta, A. Introduction: Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure. In The Promise of Infrastructure; Anand, N., Gupta, A., Appel, H., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-1-4780-0203-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, C. Last Project Standing: Civics and Sympathy in Post-Welfare Chicago; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwaa, L. Creating Protocols for Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. J. Cult. Divers. 2016, 23, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).