Biophilic Design Application in School Common Areas: Exploring the Potential to Alleviate Adolescent Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Adolescent Depression

2.2. School Common Areas Design

2.3. The Effects and Attributes of Biophilic Design

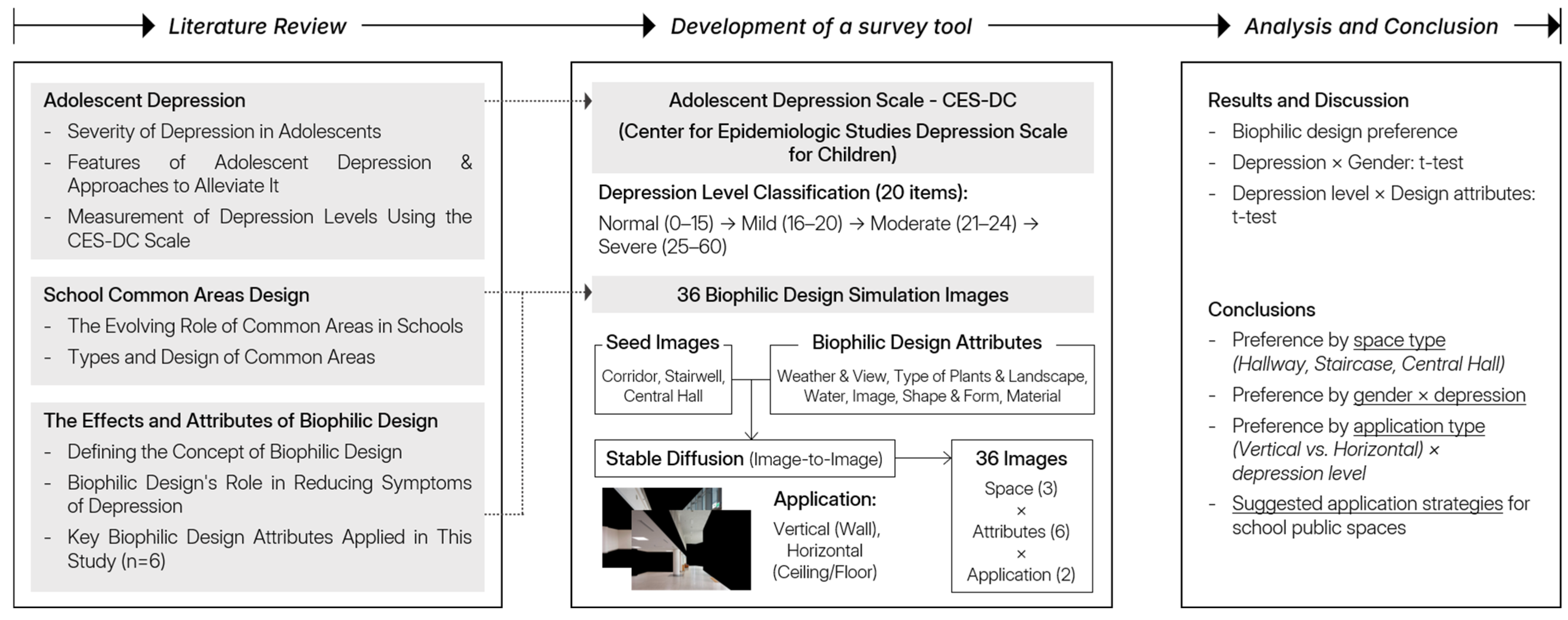

3. Survey and Analysis Methods

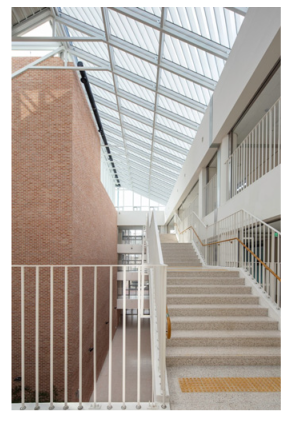

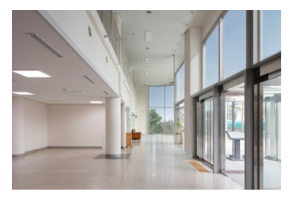

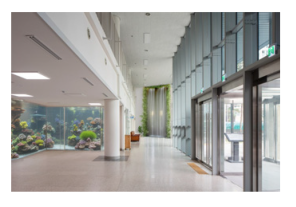

3.1. Development of Survey Tool

3.2. Survey Overview and Analysis Methods

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Characteristics of Participants and Reliability of the Survey Tool

4.2. Preferences for Biophilic Design Attributes in Common Areas

4.3. Preferences for Biophilic Design by Gender According to Depression Status

4.4. Preferences for Biophilic Design Attributes According to Depression Levels

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings and Implications

6.2. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crosnoe, R.; Johnson, M.K. Research on adolescence in the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Calls for Stronger Focus on Adolescent Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kroning, M.; Kroning, K. Teen depression and suicide: A silent crisis. J. Christ. Nurs. 2016, 33, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallfors, D.D.; Waller, M.W.; Ford, C.A.; Halpern, C.T.; Brodish, P.H.; Iritani, B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fricke, O.P.; Halswick, D.; Längler, A.; Martin, D.D. Healing architecture for sick kids: Concepts of environmental and architectural factors in child and adolescent psychiatry. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2018, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, Å.L.; Lindheim, M.Ø.; Røtting, K.; Johnsen, S.Å.K. The meaning of the physical environment in child and adolescent therapy: A qualitative study of the outdoor care retreat. Ecopsychology 2023, 15, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, C. Schools That Heal: Design with Mental Health in Mind; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, S.; Fournier, J.; Grape, C.; Grummon, P.; Morelli, J.; Whitmer, S.; Cevetello, J. Research on Learning Space Design: Present State, Future Directions; Society for College and University Planning: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin, L.R., Jr. Classroom Design—Literature Review; Special Committee on Classroom Design; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, W.; Determan, J. Outcomes of biophilic design for schools. Architecture 2024, 4, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, T.; Cleveland, B. Biophilia and adolescents’ sense of place in Australian vertical schools. Architecture 2024, 4, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.D.; Ryan, C.O.; Clancy, J.O. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health Well-Being in the Built Environment; Terrapin Bright Green: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. The biophilic school: A critical synthesis of evidence-based systematic literature reviews. Architecture 2024, 4, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.J. The ‘nature’ of vertical school design—An evolving concept. Architecture 2024, 4, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Determan, J.; Akers, M.A.; Albright, T.; Browning, B.; Martin-Dunlop, C.; Archibald, P.; Caruolo, V. The Impact of Biophilic Learning Spaces on Student Success; AIA Committee on Architecture for Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Z.; Wang, S.; Yuan, X. Trends in age-standardized incidence rates of depression in adolescents aged 10–24 in 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2019. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 350, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, J.; Wen, H.; Shen, Q. Changes in depression among adolescents: A multiple-group latent profile transition analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Houtum, L.A.; Wever, M.C.; Van Schie, C.C.; Janssen, L.H.; Wentholt, W.G.; Tollenaar, M.S.; Will, G.-J.; Elzinga, B.M. Sticky criticism? Affective and neural responses to parental criticism and praise in adolescents with depression. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Lv, J.J.; Kong, X.M.; Chu, F.; Li, Z.B.; Lu, W.; Li, X.Y. Global, regional and national burdens of depression in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years, from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2024, 225, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Roy, K. Adolescent depression: A review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2001, 35, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Demographic clinical characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, G.; Simmons, A.N.; Wu, J.; Hahn, K.S.; Tapert, S.F.; Max, J.E.; Paulus, M.P.; Brown, G.G.; Yang, T.T. Amygdala response and functional connectivity during emotion regulation: A study of 14 depressed adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.P.; Katzenellenbogen, R. Childhood and adolescent depression: The role of primary care providers in diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2005, 35, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Pyo, E.; Jeong, J.; An, J. Analysis of individual, social, and environmental factors influencing Korean adolescents’ depression and suicidal ideation by gender. J. Korean Soc. Sch. Health 2016, 29, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.A.; Flouri, E.; Kokosi, T. The role of the physical environment in adolescent mental health. Health Place 2019, 58, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Jansen, K.L.; Cloy, J.A. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 86, 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, L.S.; Stein, B.D.; Paddock, S.M.; Jaycox, L.H.; Quinn, V.P.; Chandra, A.; Burnam, A. Perceived barriers to treatment for adolescent depression. Med. Care 2009, 47, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, K.D.; Flynn, M. Adolescent depression. In Handbook of Depression, 2nd ed.; Gotlib, I.H., Hammen, C.L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 444–460. [Google Scholar]

- Faghiholislam, M.; Azemati, H.; Keshmiri, H.; Pourbagher, S. Extraction of effective cycles on reducing patients’ depression in the design of treatment spaces. Facilities 2024, 42, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBose, J.; MacAllister, L.; Hadi, K.; Sakallaris, B. Exploring the concept of healing spaces. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2018, 11, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. An inventory for measuring depression. JAMA Psychiatry 1996, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W.M. Reynolds, W.M. Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS) Second Edition. In Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment; Hersen, M., Segal, D.L., Hilsenroth, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 2: Personality Assessment and Psychopathology, pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Wilkinson, K.; Marcu, S.; Shapiro, C.M. Center for epidemiological studies depression scale for children (CES-DC). In STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales; Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S., Shapiro, C.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M.M.; Orvaschel, H.; Padian, N. Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales: Comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980, 168, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, G.; von Knotting, A.L. Depression among Swedish adolescents measured by the self-rating scale Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Child (CES-DC). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 6, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Hu, D.; Peng, E.; Abbey, C.; Ma, Y.; Wu, C.I.; Chang, C.Y.; Hung, W.T.; Rozelle, S. Depressive symptoms and the link with academic performance among rural Taiwanese children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Guidelines for Mental Health Screening Tools and Their Use; National Center for Mental Health: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2019. (In Korean)

- Jeon, K.; Choi, S.; Yang, B. The development of an integrative Korean version of CES-D. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, I. The role of schools in youth development. EPRA Int. J. Res. Dev. (IJRD) 2021, 6, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, K.; Fayyaz, H.N. Adolescence and academic well-being: Parents, teachers, and students’ perceptions. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2022, 9, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, G.T.; Chung, C.S.; Hertz, M.F.; Antolin, N. The school environment and physical and social-emotional well-being: Implications for students and school employees. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, P.C. Evidence-Based Design of Elementary and Secondary Schools: A Responsive Approach to Creating Learning Environments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. A Study on the Suitability of Communication Environments in Common Spaces of Middle School Buildings–Focusing on the Communication Function of Squares. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Educational Policy, Korea National University of Education, Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zewar, S.S. Contribution to school design through assessment of corridor conditions in foundation schools in Erbil, Iraq. Buildings 2024, 14, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, J. Hostile Hallways: Bullying, Teasing, and Sexual Harassment in School; AAUW Educational Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins Eastman Architects. Building Type Basics for Elementary and Secondary Schools; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zerlenga, O. Staircases as a representative space of architecture. In Le Vie dei Mercanti: Best Practices in Heritage Conservation Management from the World to Pompeii; La scuola di Pitagora: Naples, Italy, 2014; pp. 1632–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Islamoglu, Ö. Amphitheater stairs as socialization space in schools. Anthropologist 2016, 25, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

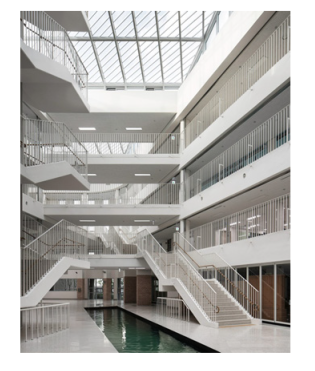

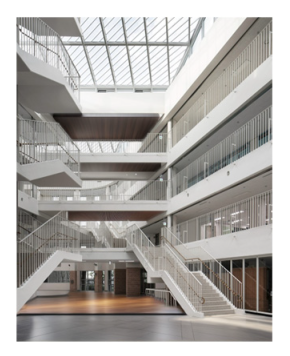

- Wu, X.; Oldfield, P.; Heath, T. Spatial openness and student activities in an atrium: A parametric evaluation of a social informal learning environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 182, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarovaya, A. Redesigning Secure School Entry Thresholds to Create Inclusive and Welcoming Environments. Undergraduate Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurðardóttir, A.K.; Hjartarson, T.; Snorrason, A. Pedagogical walks through open and sheltered spaces: A post-occupancy evaluation of an innovative learning environment. Buildings 2021, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H. Student performance and high school landscapes: Examining the links. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sullivan, W.C. Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelz, C.; Evans, G.W.; Röderer, K. The restorative effects of redesigning the schoolyard: A multi-methodological, quasi-experimental study in rural Austrian middle schools. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesooriya, N.; Brambilla, A. Bridging biophilic design and environmentally sustainable design: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolner, P.; Thomas, U.; Charteris, J. The risks of standardised school building design: Beyond aligning the parts of a learning environment. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 21, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, M.; Demers, C.M.; Potvin, A. Biophilic school architecture in cold climates. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollazadeh, M.; Zhu, Y. Application of virtual environments for biophilic design: A critical review. Buildings 2021, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J. A Hybrid Residential Model for the Biophilic Experience of the Elderly. Ph.D. Thesis, Keimyung University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2022, unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengqi, L.; Jie, Y.; Leiqing, X. Protective and restorative effects of biophilic design in high school indoor environments on stress and cognitive function. Indoor Air 2025, 2025, 8696488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, Y.C.; Choo, S. Generative artificial intelligence and building design: Early photorealistic render visualization of façades using local identity-trained models. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.-J. AI-driven biophilic façade design for senior multi-family housing using LoRA and Stable Diffusion. Buildings 2025, 15, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bezold, C.P.; Banay, R.F.; Coull, B.A.; Hart, J.E.; James, P.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Laden, F. The association between natural environments and depressive symptoms in adolescents living in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greven, C.U.; Lionetti, F.; Booth, C.; Aron, E.N.; Fox, E.; Schendan, H.E.; Homberg, J.R. Sensory processing sensitivity in the context of environmental sensitivity: A critical review and development of research agenda. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 98, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.K. Aesthetics for Green Roofs and Green Walls; Green Roofs for Healthy Cities: Asheville, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elsadek, M.; Liu, B.; Lian, Z. Green façades: Their contribution to stress recovery and well-being in high-density cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and Environment: Advances in Theory and Research; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Nasar, J.L. Urban design aesthetics: The evaluative qualities of building exteriors. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stramaglia, M. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications. 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11393/301629 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Gaekwad, J.S.; Sal Moslehian, A.; Roös, P.B.; Walker, A. A meta-analysis of emotional evidence for the biophilia hypothesis and implications for biophilic design. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 750245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common Areas | Content | Spatial Composition |

|---|---|---|

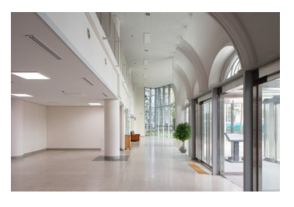

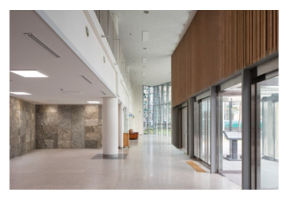

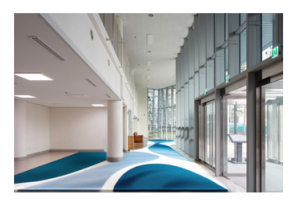

| Horizontal Communication Space | A space where communication between users on each floor takes place | - Corridor - Floor lobby |

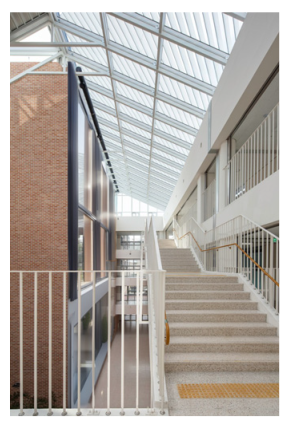

| Vertical Communication Space | A space where communication between upper and lower floors takes place | - Stairwell - Elevator area |

| Collective Communication Space | A space where horizontal and vertical communication spaces meet, and where central communication throughout the school takes place | - Indoor plaza - Central hall (main entrance) |

| BDA * | Subject to Application | Detailed Planning Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Weather & View | Vertical Plane—Wall | Curtain wall or full-face glass |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Light well or courtyard | |

| Type of Plants & Landscape | Vertical Plane—Wall | Green wall or vertical green |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Indoor garden or plant decoration | |

| Water | Vertical Plane—Wall | Waterfall space and decoration |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Water flow space and decoration | |

| Image | Vertical Plane—Wall | Actual and metaphorical images of nature |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Murals or decorations depicting nature | |

| Shape & Form | Vertical Plane—Wall | Decorations or designs utilizing geometric shapes |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Decorations or designs utilizing organic shapes | |

| Material | Vertical Plane—Wall | Wall finishes or decorations using natural materials |

| Horizontal Plane—Ceiling/Floor | Material elements or finishes inspired by natural landscapes |

| № | CES-DC Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. |

| 2 | I did not feel like eating; I wasn’t very hungry. |

| 3 | I felt that I could not shake off the sad feelings even with help from my family or friends. |

| 4 | I felt I was just as good as other kids. |

| 5 | I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing. |

| 6 | I felt down and unhappy. |

| 7 | I felt that everything I did was an effort. |

| 8 | I felt hopeful about the future. |

| 9 | I thought my life had been a failure. |

| 10 | I felt fearful. |

| 11 | My sleep was restless. |

| 12 | I was happy. |

| 13 | I talked less than usual. |

| 14 | I felt lonely, like I had no friends. |

| 15 | People were unfriendly. |

| 16 | I enjoyed life. |

| 17 | I had crying spells. |

| 18 | I felt sad. |

| 19 | I felt that people disliked me. |

| 20 | I could not get going. |

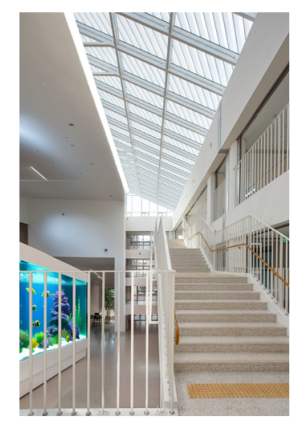

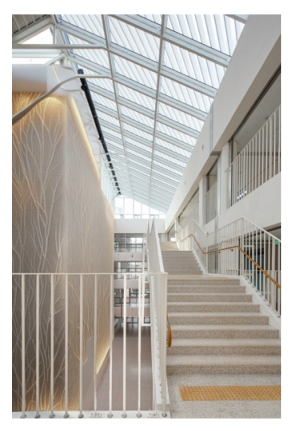

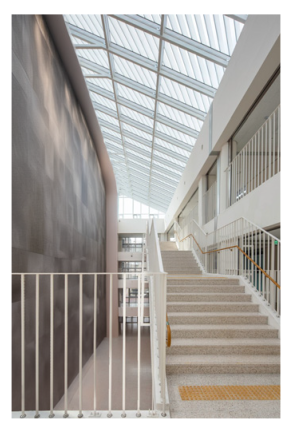

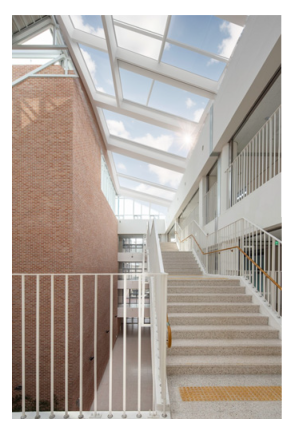

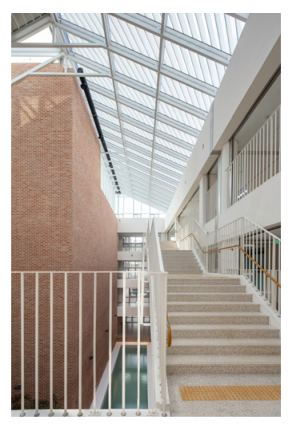

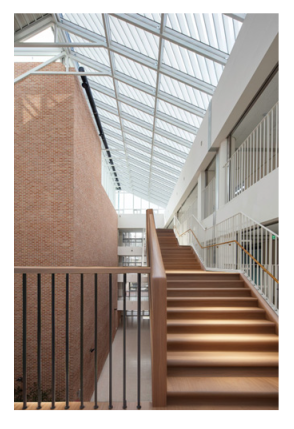

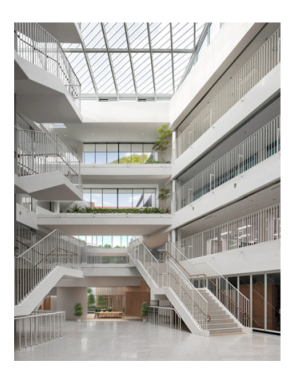

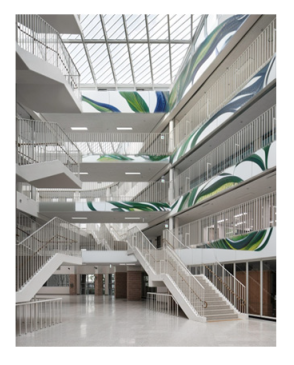

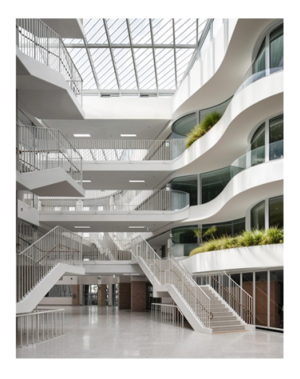

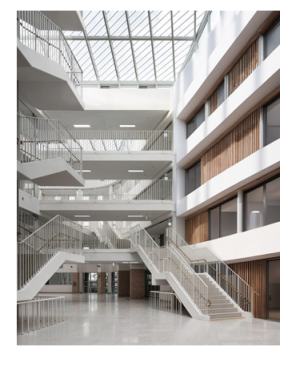

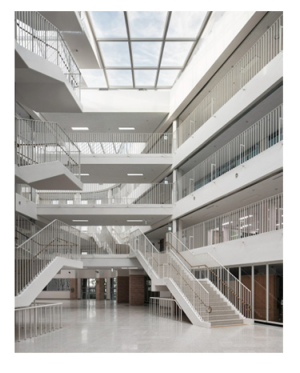

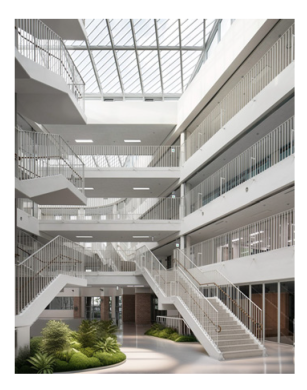

| Seed Image | Image Generation Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corridor | Stairwell | Center Hall | ||

|  |  | Sampler | Exponential SDE 2M DPM++ |

| Image Size | 900 × 600 | |||

| 900 × 1350 | ||||

| 900 × 1143 | ||||

| Steps | 25 | |||

| CGP scale | 9 | |||

| Positive Prompt | Negative Prompt |

|---|---|

| high quality, highly detailed, attention to detail, photorealistic 8k, UHD, HDR, professional photograph, realistic, precise | human, error, bed quality, tiling, sketch, ugly, pixelated, low resolution, high contrast, split image, distortion, text, watermark, name, signature |

| Metric | Details |

|---|---|

| Domain Fidelity | - To what extent do the images accurately represent the attributes of biophilic design? - Do the design elements in the image form a visually coherent and harmonious composition? - Are the biophilic attributes in the image clearly distinguishable and conceptually appropriate? |

| Visual Clarity and Quality | - Do the images for each space (central hall, stairwell, and corridor) maintain sufficient visual clarity and overall quality, considering resolution differences, to effectively convey biophilic attributes? |

| Application Orientation Consistency | - Are the biophilic attributes applied appropriately according to their application characteristics—vertically or horizontally? |

| Attribute Interpretability | - Are the biophilic attributes in the image easily identifiable and distinguishable by observers? |

| Spatial Realism | - Does the spatial composition and structure appear realistic and architecturally plausible with the applied biophilic elements? |

| TCA * | Biophilic Design Attributes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather & View | Type of Plant & Landscape | Water | Image | Shape & Form | Material | ||

| Corridor | Vertical |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Horizontal |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Stairwell | Vertical |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Horizontal |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Central Hall | Vertical |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Horizontal |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Survey Items | N | Details | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Scale (CES-DC) | 20 | 4-point scale (0: not at all~3: very much) | Descriptive statistics |

| Normal (T < 15), Mild (16 < T < 20), Moderate (21 < T < 24), Severe (25 < T < 60) | |||

| Biophilic Design Planning Characteristics Preference | 39 | Image preference for vertical and horizontal application by biophilic experience attributes : 5-point scale (1: not preferred~5: highly) | Descriptive statistics response sample t-test |

| General Matters | 2 | Gender, Age | Frequency analysis |

| Division | F (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 100 (50) |

| Female | 100 (50) | |

| Age | 16 years | 43 (21.5) |

| 17 years | 76 (38.0) | |

| 18 years | 81 (40.5) | |

| Total | 200 (100) | |

| Division | F (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Male | 46 (56.8) | 81 (40.5) | |

| Female | 35 (43.2) | |||

| Depression Level | Mild | Male | 24 (51.1) | 47 (23.5) |

| Female | 23 (48.9) | |||

| Moderate | Male | 8 (47.1) | 17 (8.5) | |

| Female | 9 (52.9) | |||

| Severe | Male | 22 (40.0) | 55 (27.5) | |

| Female | 33 (60.0) | |||

| Total | 200 (100) | |||

| Preference Survey Items | Type of Common Areas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Corridor | Stairwell | Central Hall | |||

| M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | ||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.59(0.95) | −0.699 | 3.43(0.98) | −6.930 *** | 3.93(0.79) | 2.534 * |

| Horizontal | 3.65(1.05) | 3.97(1.03) | 3.73(1.01) | ||||

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 2.73(1.17) | −3.078 ** | 3.31(1.23) | 8.851 *** | 2.91(1.23) | −7.684 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.93(1.23) | 2.56(1.21) | 3.56(1.05) | ||||

| Water | Vertical | 3.55(1.20) | 5.555 *** | 3.17(1.28) | 3.105 ** | 3.16(1.36) | 1.822 |

| Horizontal | 3.06(1.24) | 2.94(1.25) | 3.01(1.18) | ||||

| Image | Vertical | 3.12(1.09) | 5.429 *** | 3.39(1.06) | 9.700 *** | 2.42(1.14) | −3.378 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.67(1.20) | 2.66(1.11) | 2.68(1.18) | ||||

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.21(1.11) | 3.002 ** | 3.79(1.06) | 4.394 *** | 3.49(1.13) | 4.427 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.95(1.17) | 3.40(1.19) | 3.06(1.21) | ||||

| Material | Vertical | 3.64(1.06) | 3.256 ** | 3.50(1.09) | −0.870 | 3.58(1.21) | −1.024 |

| Horizontal | 3.36(1.15) | 3.57(1.08) | 3.66(1.02) | ||||

| Total | 3.21(1.14) | - | 3.31(1.13) | - | 3.27(1.11) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Male (n = 46) | Female (n = 35) | t | Male (n = 54) | Female (n = 65) | t |

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | ||||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.48(1.07) | 3.89(0.80) | −1.889 | 3.59(0.92) | 3.49(0.94) | 0.585 |

| Horizontal | 3.70(1.05) | 3.51(0.98) | 0.791 | 3.70(1.09) | 3.63(1.05) | 0.370 | |

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 2.67(1.27) | 2.66(1.35) | 0.057 | 2.89(1.06) | 2.66(1.11) | 1.137 |

| Horizontal | 2.83(1.43) | 2.74(1.22) | 0.276 | 3.06(1.17) | 3.00(1.15) | 0.261 | |

| Water | Vertical | 3.57(1.31) | 3.57(0.95) | −0.024 | 3.46(1.31) | 3.60(1.16) | −0.605 |

| Horizontal | 2.89(1.48) | 2.74(1.17) | 0.488 | 3.33(1.20) | 3.11(1.09) | 1.074 | |

| Image | Vertical | 3.24(0.99) | 2.86(0.94) | 1.752 | 3.43(1.18) | 2.91(1.10) | 2.480 * |

| Horizontal | 2.85(1.11) | 2.17(1.07) | 2.751 ** | 3.07(1.32) | 2.48(1.09) | 2.707 ** | |

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.00(1.17) | 3.34(1.06) | −1.359 | 3.20(1.19) | 3.29(1.03) | −0.436 |

| Horizontal | 3.04(1.21) | 3.06(1.08) | −0.053 | 3.09(1.15) | 2.71(1.18) | 1.788 | |

| Material | Vertical | 3.67(1.14) | 3.66(0.97) | 0.070 | 3.69(1.08) | 3.57(1.05) | 0.594 |

| Horizontal | 3.30(1.19) | 3.20(1.05) | 0.411 | 3.69(1.10) | 3.22(1.19) | 2.219 * | |

| Total | 3.19(1.20) | 3.12(1.05) | - | 3.35(1.15) | 3.14(1.10) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Male (n = 46) | Female (n = 35) | t | Male (n = 54) | Female (n = 65) | t |

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | ||||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.39(1.18) | 3.66(0.73) | −1.172 | 3.44(0.98) | 3.31(0.93) | 0.776 |

| Horizontal | 4.09(1.13) | 3.91(1.01) | 0.712 | 3.76(1.03) | 4.08(0.97) | −1.729 | |

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 3.35(1.35) | 3.29(1.34) | 0.205 | 3.44(1.21) | 3.17(1.10) | 1.301 |

| Horizontal | 2.67(1.27) | 2.54(1.22) | 0.469 | 2.70(1.27) | 2.37(1.10) | 1.542 | |

| Water | Vertical | 3.04(1.48) | 3.03(1.18) | 0.049 | 3.33(1.26) | 3.20(1.23) | 0.583 |

| Horizontal | 3.04(1.43) | 2.74(1.15) | 1.019 | 3.11(1.27) | 2.82(1.14) | 1.336 | |

| Image | Vertical | 3.43(1.03) | 3.34(0.87) | 0.426 | 3.57(1.21) | 3.22(1.04) | 1.743 |

| Horizontal | 2.80(1.09) | 2.46(1.01) | 1.467 | 3.09(1.05) | 2.29(1.10) | 4.032 *** | |

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.48(1.22) | 3.89(0.87) | −1.674 | 3.89(0.96) | 3.86(1.07) | 0.145 |

| Horizontal | 3.70(1.17) | 3.34(1.06) | 1.401 | 3.31(1.21) | 3.28(1.26) | 0.167 | |

| Material | Vertical | 3.63(1.24) | 3.51(1.01) | 0.452 | 3.65(1.05) | 3.26(1.05) | 2.001 * |

| Horizontal | 3.46(1.19) | 3.83(0.79) | −1.605 | 3.48(1.14) | 3.58(1.09) | −0.503 | |

| Total | 3.34(1.23) | 3.30(1.02) | - | 3.40(1.14) | 3.20(1.09) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Male (n = 46) | Female (n = 35) | t | Male (n = 54) | Female (n = 65) | t |

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | ||||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.93(0.88) | 3.91(0.70) | 0.113 | 3.91(0.76) | 3.95(0.82) | −0.318 |

| Horizontal | 3.76(1.18) | 3.80(0.93) | −0.162 | 3.69(0.99) | 3.71(0.95) | −0.127 | |

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 2.87(1.29) | 2.86(1.26) | 0.043 | 3.17(1.24) | 2.74(1.16) | 1.940 |

| Horizontal | 3.26(1.16) | 3.69(1.08) | −1.680 | 3.52(1.08) | 3.74(0.91) | −1.210 | |

| Water | Vertical | 3.13(1.48) | 3.17(1.18) | −0.134 | 3.39(1.38) | 2.98(1.34) | 1.617 |

| Horizontal | 2.87(1.22) | 2.86(1.09) | 0.047 | 3.20(1.22) | 3.02(1.15) | 0.865 | |

| Image | Vertical | 2.46(1.09) | 2.14(1.00) | 1.327 | 2.89(1.11) | 2.14(1.14) | 3.610 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.63(1.22) | 2.40(1.09) | 0.882 | 2.93(1.15) | 2.66(1.20) | 1.219 | |

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.39(1.11) | 3.37(1.29) | 0.075 | 3.46(1.09) | 3.63(1.11) | −0.826 |

| Horizontal | 3.04(1.17) | 2.83(1.15) | 0.824 | 3.37(1.15) | 2.94(1.29) | 1.911 | |

| Material | Vertical | 3.48(1.22) | 3.57(0.88) | −0.381 | 3.50(0.99) | 3.71(0.96) | −1.158 |

| Horizontal | 3.72(1.07) | 3.71(0.83) | 0.014 | 3.72(0.98) | 3.52(1.12) | 1.022 | |

| Total | 3.21(1.17) | 3.19(1.04) | - | 3.39(1.10) | 3.23(1.10) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal (n = 81) | Depression Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Mild (n = 47) | Moderate (n = 17) | Severe (n = 55) | |||||

| M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | ||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.65(0.98) | 0.257 | 3.47(0.93) | −1.794 | 3.35(1.06) | −0.753 | 3.65(0.89) | 0.381 |

| Horizontal | 3.62(1.02) | 3.74(1.07) | 3.65(1.17) | 3.60(1.05) | |||||

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 2.67(1.29) | −1.485 | 2.85(1.16) | −1.030 | 2.53(1.12) | −0.677 | 2.76(1.02) | −2.481 * |

| Horizontal | 2.79(1.34) | 2.98(1.17) | 2.71(1.16) | 3.16(1.13) | |||||

| Water | Vertical | 3.57(1.16) | 5.160 *** | 3.81(1.14) | 4.955 *** | 3.35(1.17) | 0.824 | 3.36(1.30) | −0.331 |

| Horizontal | 2.83(1.35) | 2.98(1.09) | 3.18(1.33) | 3.42(1.10) | |||||

| Image | Vertical | 3.07(0.98) | 3.940 *** | 3.36(1.22) | 2.921 ** | 2.76(1.03) | 1.562 | 3.07(1.12) | 1.932 |

| Horizontal | 2.56(1.14) | 2.83(1.27) | 2.41(1.06) | 2.78(1.24) | |||||

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.15(1.13) | 0.716 | 3.30(0.95) | 3.149 ** | 3.47(1.07) | 0.000 | 3.15(1.22) | 2.099 * |

| Horizontal | 3.05(1.15) | 2.77(1.24) | 3.47(1.01) | 2.80(1.15) | |||||

| Material | Vertical | 3.67(1.06) | 2.999 ** | 3.77(1.03) | 0.829 | 3.65(0.86) | 1.000 | 3.49(1.14) | 1.252 |

| Horizontal | 3.26(1.13) | 3.64(1.07) | 3.41(1.18) | 3.25(1.24) | |||||

| Total | 3.16(1.14) | - | 3.29(1.11) | - | 3.16(1.10) | - | 3.21(1.13) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal (n = 81) | Depression Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Mild (n = 47) | Moderate (n = 17) | Severe (n = 55) | |||||

| M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | ||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.51(1.01) | −3.846 *** | 3.45(1.00) | −4.644 *** | 3.35(0.86) | −1.852 | 3.31(0.96) | −3.422 ** |

| Horizontal | 4.01(1.08) | 4.09(0.93) | 3.88(0.99) | 3.82(1.07) | |||||

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 3.32(1.34) | 5.285 *** | 3.38(1.15) | 4.371 *** | 2.94(1.09) | 3.347 ** | 3.33(1.17) | 4.575 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.62(1.24) | 2.53(1.25) | 2.12(0.99) | 2.64(1.18) | |||||

| Water | Vertical | 3.04(1.35) | 1.134 | 3.49(1.23) | 2.856 ** | 3.00(1.37) | 0.270 | 3.15(1.19) | 1.759 |

| Horizontal | 2.91(1.32) | 3.09(1.33) | 2.94(1.14) | 2.84(1.12) | |||||

| Image | Vertical | 3.40(0.96) | 6.232 *** | 3.45(1.16) | 4.852 *** | 3.24(1.15) | 2.985 ** | 3.36(1.11) | 4.666 *** |

| Horizontal | 2.65(1.06) | 2.70(1.21) | 2.35(1.22) | 2.71(1.07) | |||||

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.65(1.10) | 0.778 | 3.68(1.02) | 2.733 ** | 4.12(0.78) | 4.386 *** | 3.96(1.07) | 2.889 ** |

| Horizontal | 3.54(1.13) | 3.28(1.28) | 2.76(1.03) | 3.47(1.21) | |||||

| Material | Vertical | 3.58(1.14) | −0.283 | 3.66(1.03) | −0.904 | 3.41(1.00) | 0.000 | 3.25(1.09) | −0.444 |

| Horizontal | 3.62(1.04) | 3.83(1.09) | 3.41(1.12) | 3.33(1.09) | |||||

| Total | 3.32(1.15) | - | 3.39(1.14) | - | 3.13(0.89) | - | 3.26(1.11) | - | |

| Preference Survey Items | Normal (n = 81) | Depression Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDA * | Application Characteristics | Mild (n = 47) | Moderate (n = 17) | Severe (n = 55) | |||||

| M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | M(SD) | t | ||

| Weather & View | Vertical | 3.93(0.80) | 1.180 | 4.00(0.78) | 0.306 | 3.71(0.99) | 1.305 | 3.95(0.73) | 2.206 * |

| Horizontal | 3.78(1.07) | 3.96(0.75) | 3.35(0.86) | 3.58(1.10) | |||||

| Type of Plant & Landscape | Vertical | 2.86(1.27) | −4.931 *** | 2.89(1.22) | −3.971 *** | 2.41(1.06) | −3.405 ** | 3.13(1.22) | −3.107 ** |

| Horizontal | 3.44(1.14) | 3.66(0.98) | 3.59(0.94) | 3.64(1.02) | |||||

| Water | Vertical | 3.15(1.35) | 2.136 * | 3.23(1.35) | 0.850 | 2.47(1.37) | −1.692 | 3.33(1.33) | 0.866 |

| Horizontal | 2.86(1.16) | 3.06(1.22) | 2.88(1.32) | 3.20(1.11) | |||||

| Image | Vertical | 2.32(1.06) | −1.872 | 2.40(1.15) | −2.277 * | 2.24(1.15) | −1.000 | 2.62(1.22) | −1.375 |

| Horizontal | 2.53(1.16) | 2.83(1.13) | 2.53(1.18) | 2.82(1.23) | |||||

| Shape & Form | Vertical | 3.38(1.18) | 2.860 ** | 3.53(1.08) | 2.469 * | 3.24(1.03) | 0.427 | 3.67(1.14) | 2.560 * |

| Horizontal | 2.95(1.16) | 3.06(1.22) | 3.06(1.25) | 3.22(1.27) | |||||

| Material | Vertical | 3.52(1.09) | −1.650 | 3.87(0.80) | 0.711 | 3.53(0.87) | 0.382 | 3.42(1.10) | −0.817 |

| Horizontal | 3.72(0.96) | 3.77(1.05) | 3.41(1.06) | 3.55(1.07) | |||||

| Total | 3.20(1.12) | - | 3.36(1.06) | - | 3.04(1.09) | - | 3.34(1.13) | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Biophilic Design Application in School Common Areas: Exploring the Potential to Alleviate Adolescent Depression. Buildings 2025, 15, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111863

Kim J-Y, Park S-J. Biophilic Design Application in School Common Areas: Exploring the Potential to Alleviate Adolescent Depression. Buildings. 2025; 15(11):1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111863

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ji-Yoon, and Sung-Jun Park. 2025. "Biophilic Design Application in School Common Areas: Exploring the Potential to Alleviate Adolescent Depression" Buildings 15, no. 11: 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111863

APA StyleKim, J.-Y., & Park, S.-J. (2025). Biophilic Design Application in School Common Areas: Exploring the Potential to Alleviate Adolescent Depression. Buildings, 15(11), 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111863