The Impact of Contractual Governance on Project Performance in Urban Sewage Treatment Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Contractual Governance

2.2. Urban Sewage Treatment PPP Projects

2.3. Administrative Efficiency

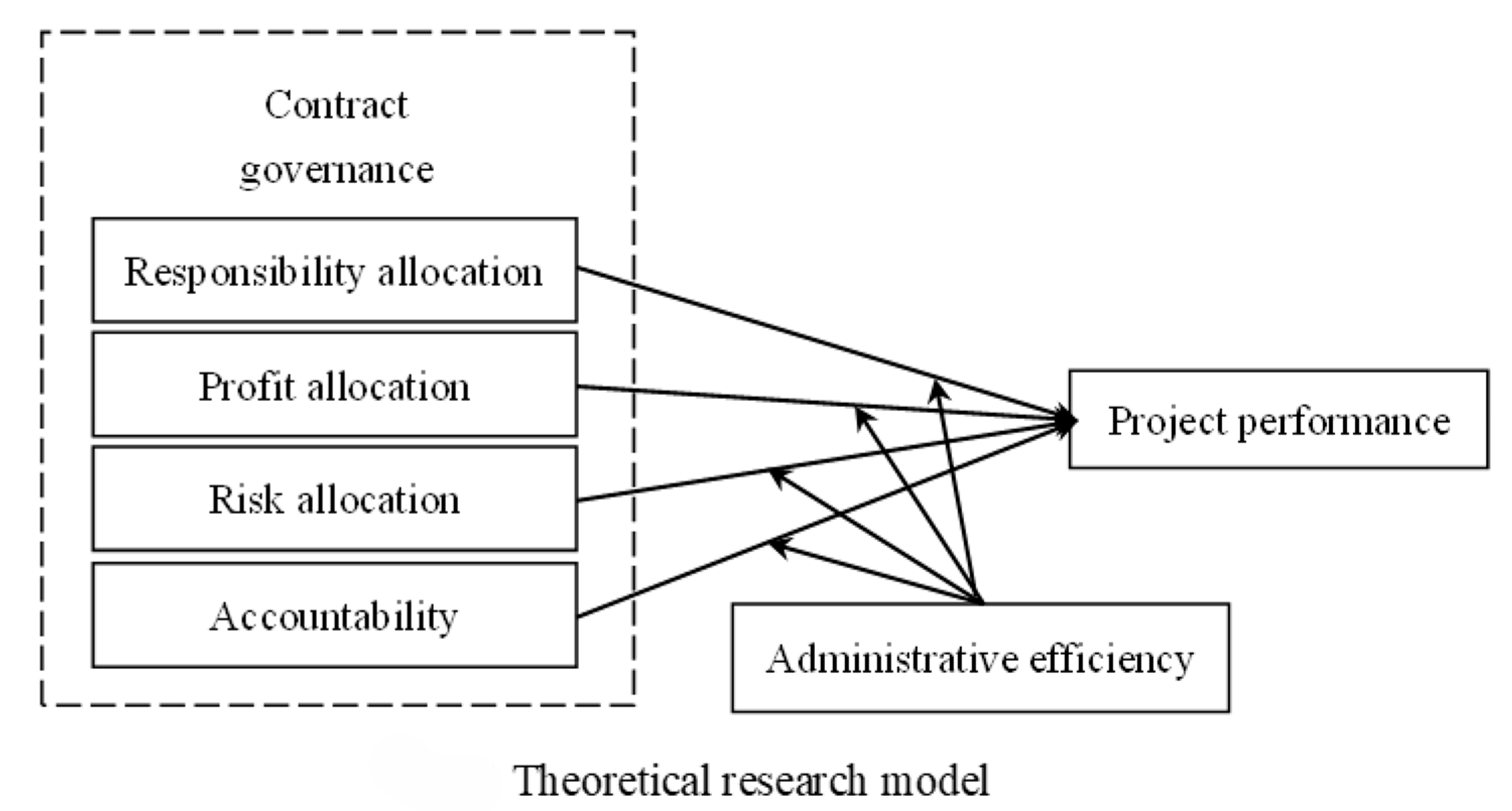

2.4. Theoretical Model

2.5. Research Hypothesis

2.5.1. Responsibility Allocation

2.5.2. Profit Allocation

2.5.3. Risk Allocation

2.5.4. Accountability

2.5.5. The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire Survey

3.3. Variables and Measurement

3.4. Reliability and Validity Test

3.4.1. Reliability

3.4.2. Validity Test

4. Results

4.1. Regression Analysis

4.1.1. Direct Effects of Contractual Relationship on Project Performance

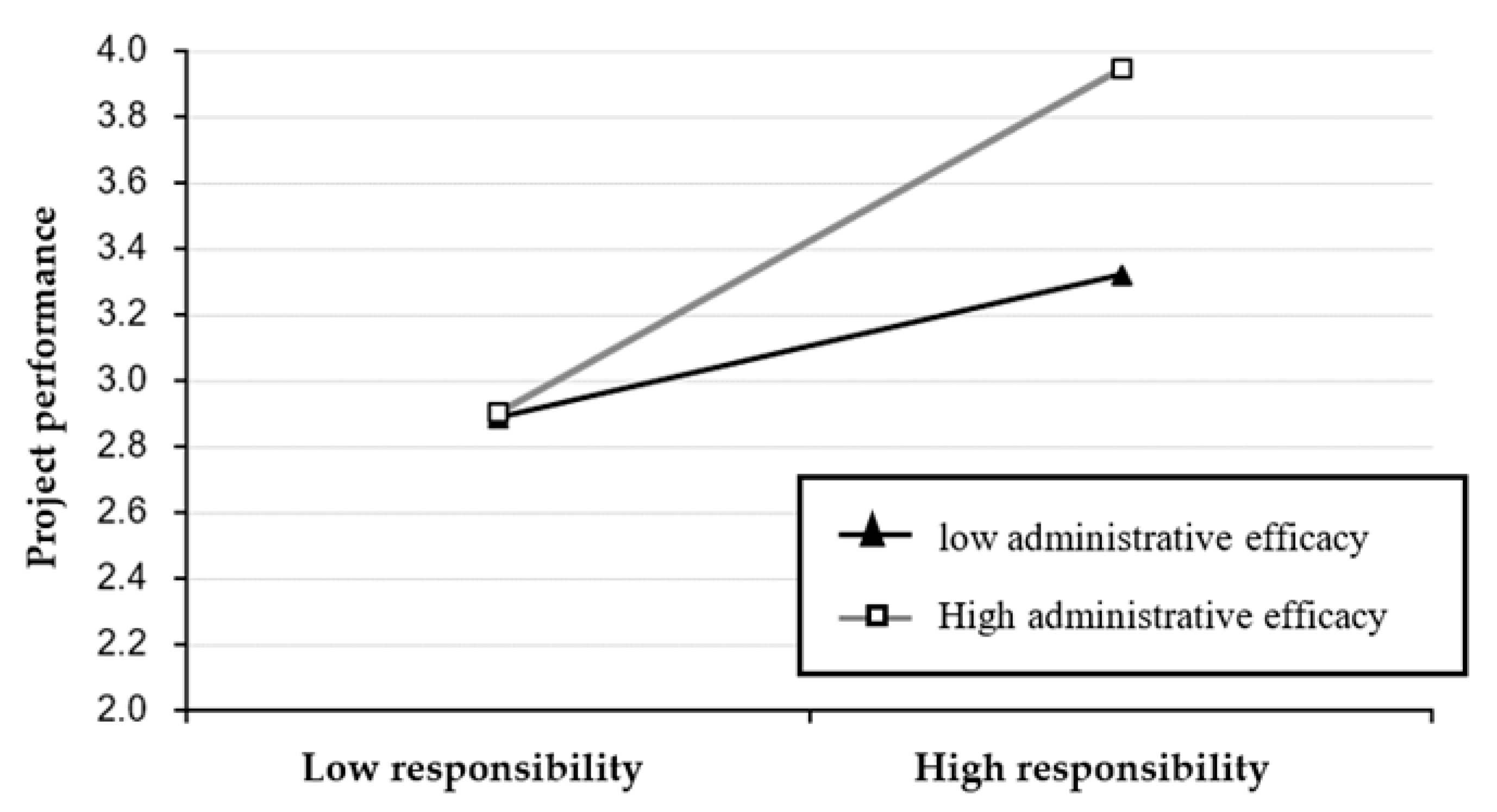

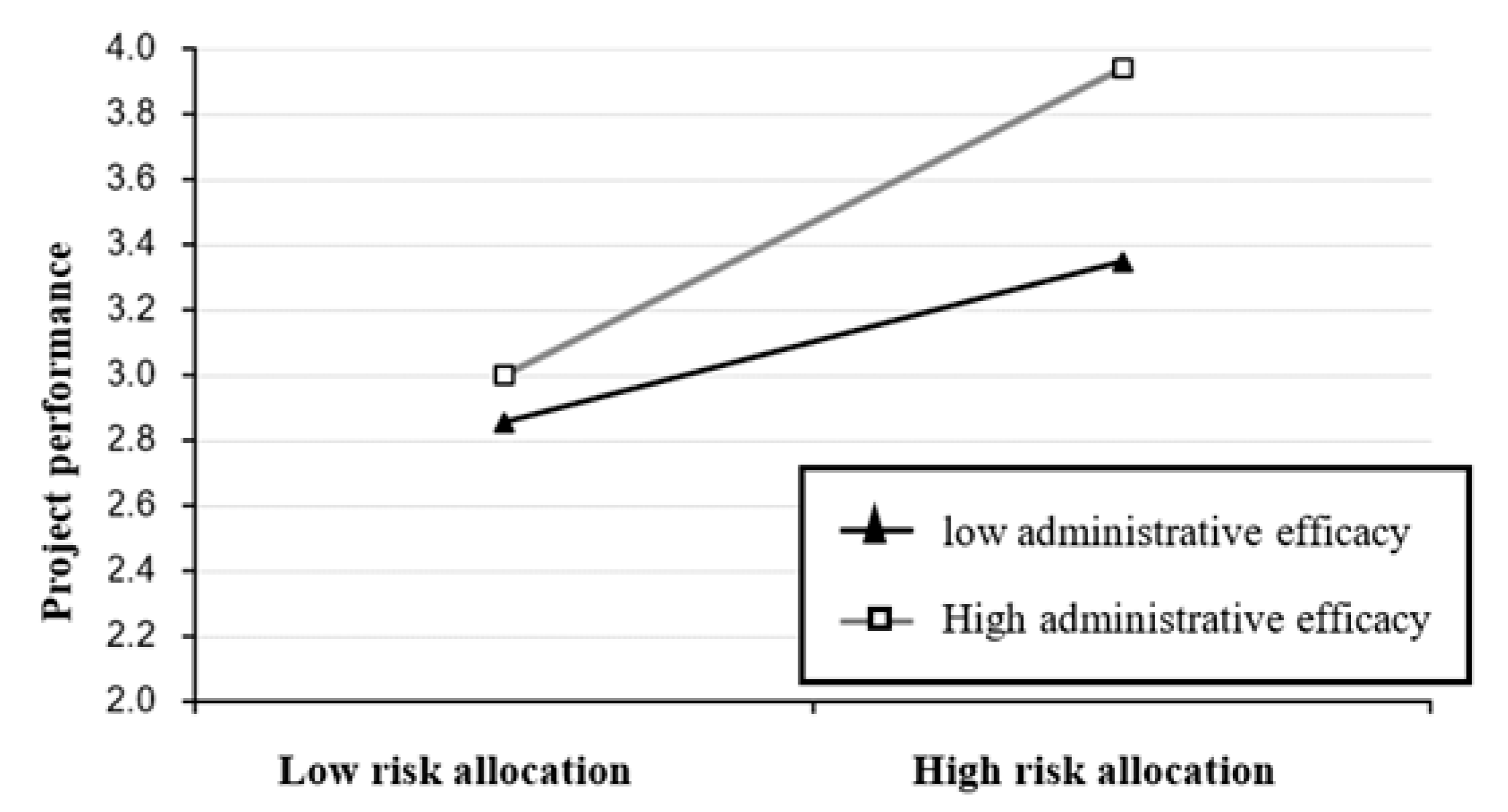

4.1.2. Moderating Effect of Administrative Efficacy on the Relationship Between Contractual Relationship and Project Performance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ameyaw, E.E.; Chan, A.P.C. Risk ranking and analysis in PPP water supply infrastructure projects: An international survey of industry experts. Facilities 2015, 33, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianico, A.; Bertanza, G.; Braguglia, C.M.; Canato, M.; Laera, G.; Heimersson, S.; Mininni, G. Upgrading a wastewater treatment plant with thermophilic digestion of thermally pre-treated secondary sludge: Techno-economic and environmental assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahimbisibwe, A.; Nangoli, S. Project Communication, Individual Commitment, Social Networks and Perceived Project Performance. J. Afr. Bus. 2012, 13, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachtler, J.; Begg, I. Beyond Brexit: Reshaping Policies for Regional Development in Europe. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiganasu, R.; Incaltarau, C.; Pascariu, G.C. Administrative Capacity, Structural Funds Absorption and Development. Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Rom. J. Eur. Aff. 2018, 18, 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Poppo, L.; Zenger, T. Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Lumineau, F. Revisiting the interplay between contractual and relational governance: A qualitative and meta-analytic investigation. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, M.; Cardinal, L.B.; Walter, J.; Lechner, C. Formal and informal control as complement or substitute? The role of the task environment. Strategy Sci. 2016, 4, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, A.; Leruth, L.; Prunier, G. Towards a principal-agent based typology of risks in public-private partnerships. Reflets Perspect. Vie Econ. 2012, 51, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M.; Van Slyke, D.M. Managing complex contracts: A theoretical approach. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.C.; Teo, T.S. Contract performance in offshore systems development: Role of control mechanisms. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 115–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Keil, M.; Hornyak, R.; Wüllenweber, K. Hybrid relational-contractual governance for business process outsourcing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 213–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yeung, J.H.Y.; Zhang, M. The impact of trust and contract on innovation performance: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.L.; Fischer, T.A.; Dibbern, J.; Hirschheim, R. A process model of complementarity and substitution of contractual and relational governance in IS outsourcing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 30, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Simster, S.J. Project contract management and a theory of organization. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 8, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floricel, S.; Miller, R. Strategizing for anticipated risks and turbulence in large scale engineering projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 19, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. J. Law Econ. 1979, 22, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A. Towards a model of governance in complex (product-service) inter-organizational systems. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.J.; Paulin, M.; Bergeron, J. Contractual governance, relational governance, and the performance of interfirm service exchanges: The influence of boundary-spanner closeness. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, W.Q.; Dooley, R. Strategic alliance outcomes: A transaction-cost economics perspective. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Contract, cooperation, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategy Manag. J. 2002, 23, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.; Kishore, R.; Rao, H.; Nam, K. The role of service level agreements in relational management of information technology outsourcing: An empirical study. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Opportunism in inter firm exchanges in emerging markets. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Cavusgil, S.T. Enhancing alliance performance: The effects of contractual-based versus relational based governance. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.T.; Gao, S.X. Price Theory and Practice. J. Price Theory Pract. 2015, 5, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.G.; Shrestha, A.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.B. Government guarantee decisions in PPP wastewater treatment expansion projects. Water 2020, 12, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, A.M.; Akal, A.Y. Assessing and allocating the financial viability risk factors in public-private partnership wastewater treatment plant projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2021, 28, 3014–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M.; Chen, L.M.; Guan, X.Q.; Fan, W.Z. Research on risk sharing of PPP plus EPC sewage treatment project based on bargaining game mode. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2020, 29, 903–912. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A.; Lucas, H.; Pasteur, K. Introduction: Accountability through participation: Developing workable partnership models in the health sector. IDS Bull. 2000, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Ketterer, T. Institutional Change and the Development of Lagging Regions in Europe. Reg. Stud. 2019, 31, 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, A.H. Rethinking European Elections: The Importance of Regional Spillover into the European Electoral Arena. JCMS 2018, 56, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milio, S. Can Administrative Capacity Explain Differences in Regional Performances? Evidence from Structural Funds Implementation in Southern Italy. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abednego, M.P.; Ogunlana, S.O. Good project governance for proper risk allocation in public-private partnerships in Indonesia. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milio, S. How Political Stability Shapes Administrative Performance: The Italian Case. West Eur. Polit. 2008, 31, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper & Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Yin, Y.L. Approach for improving performance of construction agent system for project invested by government based on project governance. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2007, 23, 156–178. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, S.; Hart, O. The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisol, N.; Dainty, A.R.J.; Price, A.D.F. The concept of ‘relational contracting’ as a tool for understanding inter-organizational relationships in construction. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual ARCOM Conference; Khosrowshahi, F., Ed.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: London, UK, 2005; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the critical success factors for public-private partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W. Social Capital and Value Creation: The Role of Intra-firm Networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Simões, P.; Marques, R.C. The hurdles of local government with PPP contracts in the waste sector. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omobowale, E.B.; Kuziw, M.; Naylor, M.T.; Daar, A.S.; Singer, P.A. Addressing conflicts of interest in public private partnerships. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2010, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.A. A classified bibliography of recent research relating to project risk management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1995, 85, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Risk management trends in the construction industry: Moving towards joint risk management. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2002, 9, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.H.; Doloi, H. Interpreting risk allocation mechanism in public-private partnership projects: An empirical study in a transaction cost economics perspective. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Klein, G. Information system success as impacted by risks and development strategies. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2004, 48, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Keil, M.; Rai, A. How software project risk affects project performance: An investigation of the dimensions of risk and an exploratory model. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mudhaf, A.S.; Al-Saeed, S.M. Quantitative analysis of critical success factors in the development of public-private partnership (PPP) project briefs in the United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2023, 5, 893–908. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, T.D.; Gonul, Z.B.; Bilgin, G.; Akcay, E.C. Exploring the critical risk factors of public–private partnership city hospital projects in Turkey. Buildings 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Leidel, K.; Riemann, A.; Alfen, H.W. An integrated risk management system (IRMS) for PPP projects. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2010, 15, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafritz, J.M. Dictionary of public policy and administration. Ref. Rev. 2004, 19, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, J.J.; Murphy, M.P. Public management: Failing accountabilities and failing performance review. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 1996, 9, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M.A.P. Analysing and Assessing Public Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. Eur. Gov. Pap. 2006, 100, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Julnes, P.L.; Holzer, M. Promoting the utilization of performance measures in public organizations: An empirical study of factors affecting adoption and implementation. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, L.; Fox, J.A.; Brown, L.D. The World Bank and public accountability: Has anything changed? In The Struggle for Accountability: The World Bank, NGOs, and Grassroots Movements; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 391–436. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.-Z.; Hao, S.Y. Influence of project governance mechanisms on the sustainable development of public-private partnership projects: An empirical study from China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K.; Slevin, D.P.; English, B. Trust in projects: An empirical assessment of owner/contractor relationships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Bachtler, J.; De Francesco, F.; Olejniczak, K.; Thomson, R.; Sliwowski, P. Administrative Capacity Building and EU Cohesion Policy; European Policy Research Centre: Glasgow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhang, Z.Y.; He, S.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Why are PPP projects stagnating in China? An evolutionary analysis of China’s PPP policies. Buildings 2024, 14, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Determining critical success factors for public–private partnership asset-backed securitization: A structural equation modeling approach. Buildings 2023, 15, 456–478. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 3, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, K.; Masten, S. Regulation and Administered Contracts Revisited: Lessons from Transaction Cost Economics for Public Utility Regulation. J. Regul. Econ. 1996, 8, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatyan, E.; Sarvari, H.; Hosseini, S.A.; Javanshir, H. Determining the Factors Influencing Construction Project Management Performance Improvement through Earned Value-Based Value Engineering Strategy: A Delphi-Based Survey. Buildings 2023, 13, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.K. Capacity, Efficiency, and Effectiveness: Approaches to Improving Administrative Efficiency of Township Governments. Acad. Forum. 2007, 11, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Code | Measurement Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsibility allocation | C11 | There is no overlap of responsibilities among project stakeholders | Faisol and Dainty [40] |

| C12 | There is no responsibility vacuum in the project | ||

| C13 | There is no unauthorized use or abuse of power by any of the stakeholders in the project | ||

| C14 | An equivalent relationship exists between the rights and responsibilities of project stakeholders | ||

| Profit allocation | C21 | The benefits received by project stakeholders match the size, complexity, and special requirements of the project. | Crocker and Masten [65] |

| C22 | The contract price is adjusted and compensated according to price fluctuations, engineering changes, and related policy changes | ||

| C23 | Corresponding penalty clauses for failure to effectively perform the contract are set up | ||

| C24 | Corresponding reward clauses for early completion, investment savings, or project awards are set up | ||

| Risk allocation | C31 | Project stakeholders understand the project risks or changes that may occur in the future | |

| C32 | Project stakeholders understand the procedures and principles for sharing the responsibility for project risks and changes that may occur in the future | Fischer [52] | |

| C33 | When dealing with project risks or changes, the reasonable interests of project stakeholders are considered | Jin and Doloi [47] | |

| Accountability | C41 | Project management issues have corresponding standards and basis for accountability | |

| C42 | Irregular behavior of stakeholders in the project is strictly investigated | Bovens [55] | |

| C43 | Project stakeholders accept and approve the results of an accountability investigation | ||

| G1 | Project stakeholders are able to achieve the expected goals | ||

| Project performance | G2 | Incentives obtained by project stakeholders can effectively drive positive behaviors | Wallace et al. [49] Pinto et al. [59] |

| G3 | Project stakeholders are satisfied with their cooperation with other parties | Nejatyan et al. [66] | |

| G4 | Project stakeholders can be effectively restrained | ||

| P1 | Project stakeholders are satisfaction with the government and the affairs of related governmental departments | ||

| Administrative efficiency | P2 | The governing ability and level of governmental affairs of the government and related departments | Su [67] |

| P3 | Administrative efficiency of the government and related departments | Data survey |

| Scale | Subscale | Measurement Items | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractual relationship | Responsibility allocation | C11-C14 | 0.852 | 0.859 | 0.607 |

| Profit allocation | C21-C24 | 0.857 | 0.851 | 0.590 | |

| Risk allocation | C31-C33 | 0.799 | 0.805 | 0.581 | |

| Accountability | C41-C43 | 0.822 | 0.833 | 0.626 | |

| Project performance | G1-G4 | 0.838 | 0.821 | 0.538 | |

| Administrative efficiency | P1-P3 | 0.815 | 0.820 | 0.607 |

| Responsibility Allocation | Profit Allocation | Risk Allocation | Accountability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responsibility allocation | 0.607 | |||

| Profit allocation | 0.316 | 0.590 | ||

| Risk allocation | 0.353 | 0.365 | 0.424 | |

| Accountability | 0.330 | 0.270 | 0.348 | 0.255 |

| Responsibility Allocation | Profit Allocation | Risk Allocation | Accountability | Administrative Efficiency | Project Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responsibility allocation | 1 | |||||

| Profit allocation | 0.313 ** | 1 | ||||

| Risk allocation | 0.361 ** | 0.362 ** | 1 | |||

| Accountability | 0.330 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.385 ** | 1 | ||

| Administrative efficiency | 0.394 ** | 0.266 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.401 ** | 1 | |

| Project performance | 0.496 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.330 ** | 1 |

| Model | Standard | T-Value | Significance Level | R2 | F | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Deviation | Beta | CS | VIF | ||||||

| 1 | (constant) | 3.075 | 0.349 | 8.819 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.863 | |||

| Project size | −0.002 | 0.028 | −0.007 | −0.083 | 0.934 | 0.871 | 1.148 | |||

| Job position | 0.082 | 0.058 | 0.130 | 1.427 | 0.156 | 0.766 | 1.305 | |||

| 2 | (constant) | 0.381 | 0.361 | 1.055 | 0.293 | 0.463 | 14.375 *** | |||

| Project size | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.053 | 0.824 | 0.411 | 0.858 | 1.166 | |||

| Job position | 0.084 | 0.044 | 0.133 | 1.930 | 0.055 | 0.758 | 1.319 | |||

| Responsibility allocation | 0.225 | 0.061 | 0.255 *** | 3.693 | 0.000 | 0.752 | 1.329 | |||

| Profit allocation | 0.200 | 0.059 | 0.227 ** | 3.370 | 0.001 | 0.790 | 1.265 | |||

| Risk allocation | 0.208 | 0.062 | 0.240 ** | 3.365 | 0.001 | 0.706 | 1.417 | |||

| Accountability | 0.188 | 0.059 | 0.214 ** | 3.171 | 0.002 | 0.785 | 1.274 | |||

| Variable | Project Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Project size | −0.007 | 0.016 | 0.009 |

| Job position | 0.130 | 0.113 | 0.115 |

| responsibility allocation | 0.431 *** | 0.415 *** | |

| Administrative efficiency | 0.154 * | 0.180 * | |

| responsibility allocation × administrative efficiency | 0.155 * | ||

| R2 | 0.027 | 0.283 | 0.306 |

| ∆ R2 | −0.004 | 0.250 | 0.270 |

| F | 0.863 | 8.581 *** | 8.339 *** |

| Variable | Project Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Project size | −0.007 | −0.018 | −0.008 |

| Job position | 0.130 | 0.145 | 0.143 |

| profit allocation | 0.394 *** | 0.383 *** | |

| Administrative efficiency | 0.216 ** | 0.219 ** | |

| Profit allocation × administrative efficiency | 0.129 | ||

| R2 | 0.027 | 0.272 | 0.287 |

| ∆ R2 | −0.004 | 0.238 | 0.249 |

| F | 0.863 | 8.108 *** | 7.603 *** |

| Variable | Project Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Project size | −0.007 | 0.030 | 0.039 |

| Job position | 0.130 | 0.120 | 0.101 |

| Risk allocation | 0.445 *** | 0.448 *** | |

| Administrative efficiency | 0.171 * | 0.189 * | |

| Risk allocation × Administrative efficiency | 0.145 * | ||

| R2 | 0.027 | 0.301 | 0.320 |

| ∆ R2 | −0.004 | 0.268 | 0.284 |

| F | 0.863 | 9.331 *** | 8.869 *** |

| Variable | Project Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Project size | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.007 |

| Job position | 0.130 | 0.160 | 0.159 |

| Accountability | 0.385 *** | 0.384 *** | |

| Administrative efficiency | 0.174 * | 0.176 * | |

| Accountability × administrative efficiency | 0.007 | ||

| R2 | 0.027 | 0.257 | 0.257 |

| ∆ R2 | −0.004 | 0.222 | 0.217 |

| F | 0.863 | 7.497 *** | 6.518 *** |

| Number | Research Hypothesis | Test Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | The contractual relationship positively impacts project performance. | Supported |

| H1a | Responsibility allocation positively impacts project performance. | Supported |

| H1b | Profit allocation positively impacts project performance. | Supported |

| H1c | Risk allocation positively impacts project performance. | Supported |

| H1d | The accountability relationship positively impacts project performance. | Supported |

| H2 | Administrative efficiency positively regulates the relationship between the contractual relationship and project performance. | Partially Supported |

| H2a | Administrative efficiency positively regulates the relationship between responsibility allocation and project performance. | Supported |

| H2b | Administrative efficiency positively regulates the relationship between profit allocation and project performance. | Not Supported |

| H2c | Administrative efficiency positively regulates the relationship between risk allocation and project performance. | Supported |

| H2d | Administrative efficiency positively regulates the relationship between accountability and project performance. | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gui, J.; Song, J.; Xia, W. The Impact of Contractual Governance on Project Performance in Urban Sewage Treatment Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency. Buildings 2025, 15, 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111858

Gui J, Song J, Xia W. The Impact of Contractual Governance on Project Performance in Urban Sewage Treatment Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency. Buildings. 2025; 15(11):1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111858

Chicago/Turabian StyleGui, Jialin, Jinbo Song, and Wen Xia. 2025. "The Impact of Contractual Governance on Project Performance in Urban Sewage Treatment Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency" Buildings 15, no. 11: 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111858

APA StyleGui, J., Song, J., & Xia, W. (2025). The Impact of Contractual Governance on Project Performance in Urban Sewage Treatment Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Moderating Role of Administrative Efficiency. Buildings, 15(11), 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15111858