A Capability Maturity Model for Integrated Project Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Defining IPD Maturity Levels: Establishing distinct maturity levels within IPD practices and providing clear criteria for progressing through these levels.

- Identifying IPD Capabilities: Undertaking a detailed examination, identification, and categorization of specific capabilities essential for successful IPD implementation.

- Identifying IPD Capability Indicators: Identifying indicators of capabilities derived directly from practical applications of IPD.

- Developing the IPD Maturity Matrix: Integrating IPD capabilities and IPD maturity levels to form a detailed maturity matrix that outlines the indicators of each capability within each maturity level.

- IPD Maturity Assessment Tool: Transforming the detailed maturity matrix into a tool that enables evaluation and determines the maturity level of different capabilities.

2. Background

2.1. Established Maturity Models

2.2. Established IPD Frameworks

3. Methodology

3.1. Developing the General IPD Maturity Levels

3.2. Defining IPD Capabilities

3.3. Identifying IPD Capabilities Indicators

- Case study 1: A municipal aquatic facility in British Columbia, Canada was renovated and enhanced with the goals of improving resilience, energy efficiency, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Case study 2: Two state-of-the-art educational institutions were built in Alberta, Canada, underpinned by the principles of 21st-century learning and design.

- Case study 3: A shared infrastructure in Ontario, Canada was developed through collaboration between two public entities, intended for three distinct first responder agencies. A centralized campus was designed to streamline the planning and execution of programs for these responders.

3.4. Developing the IPD Maturity Matrix

3.5. Creating the IPD Maturity Assessment Tool (IPD-MAT)

3.6. Validation and Feedback

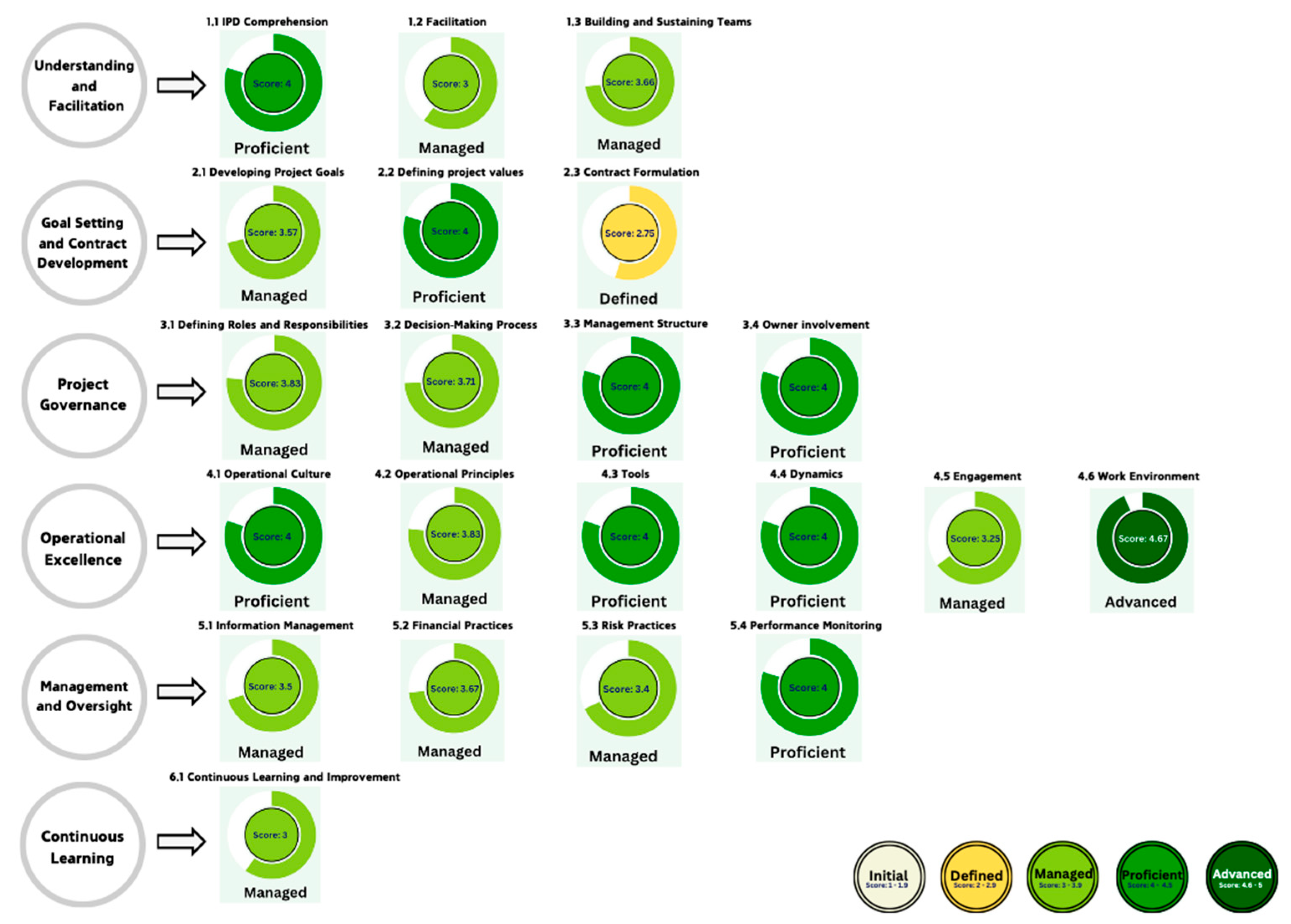

- Evaluation Sessions: These sessions entailed administering the IPD Maturity Assessment Tool questionnaire to owners’ representatives to assess the maturity levels of various capabilities within their projects.

- Maturity Reporting: After the evaluations, detailed reports were compiled to outline the IPD maturity of identified capabilities in each project, providing a detailed overview of current practices and maturity levels.

- Feedback Interviews: Follow-up interviews were conducted with these stakeholders to discuss the findings detailed in the reports and evaluate the overall utility of both the Assessment Tool and the maturity model.

4. The IPD Capability Maturity Model (IPDCMM)

4.1. IPD Maturity Levels

4.2. IPD Capabilities

4.3. IPD Capability Indicators

4.4. IPD Maturity Matrix

4.5. IPD Maturity Assessment Tool (IPD-MAT)

- Initial (1.0–1.9)

- Defined (2.0–2.9)

- Managed (3.0–3.9)

- Proficient (4.0–4.5)

- Advanced (4.6–5.0)

4.6. Application and Validation of the Maturity Model and Assessment Tool

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Capability Set | # | Capability | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Defined | Managed | Proficient | Advanced | |||

| Understanding and facilitation | 1.1 | IPD comprehension | Limited awareness of IPD principles, processes, and key success factors. | Demonstrates familiarity with IPD principles and processes and understands their relevance to project success. | Possesses a solid understanding of IPD principles and processes, actively beginning to integrate and apply these concepts in the project’s execution. | Possesses an in-depth understanding of IPD principles and processes and effectively implements IPD strategies and practices across the project. | Exhibits advanced comprehension of IPD principles, processes, and drivers for success, allowing them to adapt and refine IPD practices based on project needs. |

| 1.2 | Facilitation | Facilitation processes are not well established and may not address team needs adequately within the IPD framework. | Facilitation processes are being developed and are beginning to address the fundamental needs of the team in terms of general knowledge about IPD and its processes and stages. | Established facilitation processes are in place, providing necessary knowledge about IPD and its processes, in addition to any needed training on the tools and techniques that will be applied during the project. | Effective facilitation techniques are employed, addressing the team’s specific needs (or knowledge gaps) based on a thorough assessment and training of the team toward achieving a collaborative IPD project environment. | Innovates in facilitation practices and training to equip the team with the knowledge, latest methods, and tools to be most effective and to contribute to establishing a favorable culture. | |

| 1.3 | Building and sustaining teams | Efforts and resources invested to establish a unified and cohesive team culture are limited. | Attempts to build a cohesive team culture are emerging, with steps to reduce hierarchy and encourage open communication. | Continuous efforts and plans to establish a cohesive team culture are designated as an integral part of the project activities. | Team-building efforts are prioritized and recognized as one of the key drivers for project success. The project culture is supportaive and encourages participation. | Innovative practices are in place to foster a cohesive culture and unity, leading to an exemplary team environment that enhances ownership and encourages active participation and collaboration. | |

| Goal setting and contract development | 2.1 | Developing project goals (validation process) | The validation process is unstructured and conducted with limited collaboration. The validation report is unclear and lacks detail. | Initial efforts at structuring the validation process are visible, with some collaboration among team members beginning to take shape. The validation report is basic and lacks clarity and depth. | The validation process is effectively conducted, with clear project objectives, base target costs, and schedules established through collaborative efforts. Provides a clear validation report and results. | The validation process is highly efficient, detailed, and collaborative, resulting in precise project objectives, costs, and schedules. Delivers a detailed and structured validation report for owner assessment. | The project team excels in the validation process, demonstrating innovation and leading to an insightful validation report that aids owner decision-making. Effectively uses the validation phase to seed and enhance a collaborative project culture. |

| 2.2 | Defining project values | The project values are not defined or unclear. The project team has limited understanding and awareness of these values, and they are not referred to in the decision-making process. | Project values are identified but not fully integrated into project processes. There is an emerging effort to communicate these values to the team, though reference to them in decision-making is limited. | Core values are clearly defined and communicated across the project. The values are frequently referred to in the decision-making processes; however, their application is inconsistent. | Project values are clearly defined and consistently applied in the decision-making processes. The project team frequently does values checks to ensure consistent commitment and alignment. | The project values are clear and deeply integrated into the project’s operations and decision-making processes. The team adopts innovative methods to reinforce values and ensure their active influence on the project’s culture and outcomes. | |

| 2.3 | Contract formulation | Contract formulation lacks true collaboration. Some IPD elements, such as liability waiver, are absent. | Contract formulation is done somewhat collaboratively. The main IPD principles are incorporated into the contract. | Contracts are formulated through a collaborative process with the active participation of all stakeholders. The contract fully integrates IPD principles. | Contract formulation is highly collaborative, leveraging advanced techniques such as workshops and expert consultations. The contract reflects a true IPD project with all of its features. | The contract formulation process is highly collaborative, featuring signs of innovation, with attempts to go beyond standard IPD contracts to enhance stakeholders’ collaboration and optimize contract terms to precisely reflect the project conditions. | |

| Project governance | 3.1 | Defining roles and responsibilities | Limited understanding of individual and collective roles within the project. Roles are not clear, overlapping, and in some cases conflicting, which affects team synergy. | Awareness of roles begins to form. Efforts are made to include all parties in discussions on roles and responsibilities, with leading roles for individuals with prior experience with IPD. | Roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and communicated, emphasizing the importance of each member’s contribution to project success. | The team adopts a new entity mindset and deeply understands their interconnected roles, accountability structure, and how they contribute to the project’s success. | Roles and responsibilities, accountability structure, and unique contributions of each party to the project’s success are deeply understood, allowing for flexibility and adaptability in roles. This enables the team to adjust roles as needed to ensure project success. |

| 3.2 | Establishing the decision-making process | The decision-making process is made with limited transparency and collaboration and with limited guidance from project goals and values. | The team begins to establish a decision-making process that is guided by project goals and values. However, the process does not include all team members, and documentation is inconsistent. | A collaborative decision-making process is in place, with team members actively participating in open discussions that lead to decisions grounded in shared project values. Decision matrices and other tools are employed to evaluate alternatives, with most decisions being well documented. | Decision-making is highly inclusive and reflective of the project’s joint management approach. There is an effective use of tools like decision matrices to assess alternatives, alongside a thorough documentation of the context and rationale of decisions. | In addition to inclusivity, transparency, collaboration, and thorough documentation, the decision-making process is characterized by adaptability, agility, and responsiveness to evolving project needs. | |

| 3.3 | Establishing the management structure | The management structure is undefined or poorly organized. Lack of coordination among SMT, PMT, and PIT leads to confusion and inefficiencies, impacting project flow. | Initial efforts to establish a structured management framework are in place, improving communication between management levels. However, these structures are not fully optimized, resulting in some operational inefficiencies. | A clear management structure is established, with distinct roles and responsibilities across the management levels (SMT—PMT—PIT). This structure enhances project coordination, effective decision-making, and project progression. The PMT undertakes most of the project work, with limited roles for the SMT and PITs. | The management structure operates efficiently and is marked by highly coordinated efforts between SMT, PMT, and PIT, each with a distinct role that is performed entirely to ensure smooth project execution. The PMT acts as the operational core, driving most project activities. The SMT plays a supervisory and conflict-resolution role and stays continuously informed and engaged. PITs are active as multidisciplinary teams handling specific project areas with expertise. | The management structure operates with full efficiently and is characterized by adaptability to the project needs and innovation in management practices to boost collaboration and efficiency across SMT, PMT, and PIT. | |

| 3.4 | Owner involvement | Owner involvement is minimal, with little engagement in daily management or decision-making. | The owner begins to take a more active role, though involvement is still limited to key decisions or milestones. | The owner is actively involved in project governance, contributing to decision-making and supporting the IPD approach. | The owner plays a central role in project governance, fully embracing the IPD model and contributing to its success through active participation and leadership. | The owner is the actual leader of the project and the primary champion of IPD. Their involvement is transformative, where they drive the project forward with a deep commitment to IPD principles, fostering collaboration, and creating a distinct team culture. | |

| Operational excellence | 4.1 | Operational culture | The operation culture is primarily traditional, and no efforts are made to encourage a shift towards lean thinking, collaborative work, and a no-blame culture. | Efforts and initiatives to shift from traditional practices to a lean and collaborative culture, including adopting a no-blame culture, are emerging, and their importance is increasingly recognized. | Determinate and continuous efforts are in place to promote a lean, collaborative, and no-blame culture. Various practices are implemented and regularly assessed for effectiveness. | A lean and collaborative culture, underpinned by a no-blame environment, is well-integrated into the project’s daily activities and significantly influences its operations. | The team fully embodies a lean and collaborative culture, with a solid commitment to a no-blame culture that drives ongoing innovation in practices and implementation. |

| 4.2 | Operational principles | Integrating lean design and construction principles with IPD principles into the project operations is minimal. | Lean design and construction and IPD key principles are starting to be integrated into the project process, and there is growing recognition of their importance for project success. | Key lean design and construction and IPD principles are effectively applied, and their influence on project operations is visible. | Lean design and construction principles are fully integrated into IPD processes. The project’s operational activities are driven by lean principles, focusing on streamlining workflows, reducing waste in methods and materials, and maximizing value. | Lean design and construction principles are an essential part of the project management approach and have a tangible influence on project efficiency with notable innovation and continuous improvement in the application. | |

| 4.3 | Tools | Basic use of BIM for visualization without integration of lean tools, with no substantial contribution to project coordination or collaboration. | BIM is integrated into the project for basic coordination tasks such as clash detection, but its full collaborative potential remains largely untapped. Utilization of lean tools is limited to planning tools such as pull planning and the last planner. | BIM is effectively utilized, directly enhancing project coordination and collaboration. The model is collaboratively developed and regularly updated. A wider range of lean tools, such as pull planning, last planner, plus/delta, and target value design, are being used. | BIM is a central element of the project management strategy, facilitating advanced project coordination and communication and significantly improving workflow. Lean tools are extensively applied, streamlining workflows and reducing waste in processes and materials. | BIM facilitates advanced project coordination and communication, provides a verified source of information in the project, and is characterized by driving innovative practices. Lean tools and techniques are the core of the project’s operational practices, significantly influencing project efficiency. | |

| 4.4 | Dynamics | Multidisciplinary team integration is minimal, with limited inclusivity. Teams are initially formed and remain fixed throughout the project, with no adaptability to project needs. | Teams include a broader range of participants. There is minimal adaptability in team formation based on project demands, and teams take limited responsibility for tasks. | Multidisciplinary teams are fully inclusive. There is emerging flexibility in forming teams as project needs arise, and they are given clearer responsibilities. | Multidisciplinary teams operate with high efficiency and are fully adaptable to project needs. They are empowered to manage their tasks comprehensively. | Multidisciplinary teams are highly effective, fully adaptable, and seamlessly integrate all relevant disciplines and stakeholders. Their work is central to the project’s success, driving innovation and efficiency through true integration. | |

| 4.5 | Engagement | Communication is predominantly formal, confined mostly to emails and paper documents. There is minimal effort to facilitate and enhance active engagement. | Begins to expand beyond formal correspondence with more exchange channels, such as big-room meetings, facilitating greater stakeholder engagement. | Effective, routine communication and engagement practices are well established. Active participation from all team members is evident, supported by both structured communication protocols and informal channels, such as collaboration platforms. | Communication and engagement strategies are effective and inclusive, including the on-site team to keep them in the loop and aligned with the project’s culture and objectives. Engagement features the appropriate use of tools, including various digital communication means. | Innovates in communication and engagement strategies that facilitate communication and active participation, reflecting a superior collaborative culture. | |

| 4.6 | Work environment | Initial use of big room. Infrequant meetings are occurring (physical or virtual) with minimal impact on project collaboration. | Frequent big room meetings occur (physical or virtual). Meetings are primarily traditional in format, with limited impact on team collaboration and culture. | Big room sessions are frequent and tailored to maximize team interaction. The meeting spaces are arranged to encourage open dialogue, and sessions include all team members and are characterized as being highly collaborative and productive. | Big room sessions are integral to the project’s workflow. Sessions include advanced setups that promote superior collaboration and inclusivity. Cultural practices such as equal seating and a no-title zone are evident, enhancing team unity and engagement. | Innovative approaches in big room facilitation regarding accommodations and tools. The dominant culture reflects a true unity and harmony that masters collaboration and engagement. | |

| Management and oversight | 5.1 | Information management | Information sharing is not structured and is often paper-based, with little to no integration of digital tools. | Establishes basic protocols for data management that support the needs of IPD projects. Begins to enhance information accessibility and organization to facilitate better collaboration. | Manages a structured flow of information, offering enhanced data accuracy and real-time access to all project members, facilitated by digital tools like BIM. | Advanced information management systems are fully integrated, providing comprehensive data access and utilization across platforms, supporting collaborative practices and decision making. | There is innovation in information management within IPD projects, with the use of cutting-edge technologies such as AI, digital twins, and VR, which are employed to enhance data utilization and collaborative decision making. |

| 5.2 | Financial practices | Limited engagement in collaborative financial practices. Financial activities are mostly siloed with minimal transparency, and there are no incentive mechanisms to sustain collaboration through out the project phases. | Recognizes the benefits of collaborative financial practices and begins to implement open-book accounting. Efforts to involve team members in financial discussions are underway, fostering a culture of shared financial responsibility. Incentive mechanisms are introduced but are in early stages. | Regularly integrates team members in financial decision making, ensuring financial transparency and shared responsibility. Incentive mechanisms are in place but need further refinement to effectively sustain team collaboration throughout the project. | Team members are fully integrated in financial decisions, with highly transparent operations and established practices of shared responsibility and individual accountability. Incentive mechanisms are well defined and strategically designed to sustain collaboration throughout the project phases. | Demonstrates innovative strategies and tools to integrate team members in financial decision-making with a mature culture of shared financial responsibility and solid individual accountability. The incentive mechanisms are sophisticated, effectively maximizing team performance and fostering sustained collaboration. | |

| 5.3 | Risk practices | Initial steps are taken to collaboratively identify risks using shared tools like risk registers. Awareness of collective risk management practices is emerging among team members. | There is regular use of collaborative tools such as risk registers to identify and assess risks. Team members start to actively engage in joint mitigation efforts and establish clear roles in risk ownership. | Routinely conducts comprehensive risk assessments collaboratively. Strategies for risk mitigation are collaboratively developed and implemented, demonstrating a mature understanding of shared risk ownership. | Advanced integration of risk management practices, with all team members actively using and updating risk management tools like risk registers. Collective ownership of risk mitigation processes is well established, with proactive strategies effectively minimizing risks. | Risk management processes are innovative and fully integrated into every phase of the project, with exceptional team engagement and a strong culture of collective risk ownership. | |

| 5.4 | Performance monitoring | Basic data collection is in place with minimal integration. There is little to no use of unified data forms or dashboards. | Project dashboards are introduced, visualizing basic performance metrics like budget and schedule adherence. Efforts are made to standardize data collection, but comprehensive integration is lacking. | Regular use of project dashboards that track a broader range of metrics, such as safety and culture, tailored to the specific needs of the project. Data from various project members begins to become unified, enhancing the accuracy of performance reviews. | Comprehensive integration of performance metrics into regularly updated dashboards that facilitate decision making and prompt resolution of emerging issues. Metrics are fully unified across all project disciplines, providing a holistic view of the project status. | Innovates in performance monitoring practices. Employing cutting-edge tools and technologies that allow real-time data to be integrated into sophisticated dashboards that offer comprehensive insights into all critical project aspects and drive continuous improvement. | |

| Continuous learning | 6.1 | Continuous learning and improvement | Recognizes the need to capture lessons learned but lacks a formal process with minimal systematic analysis. | Begins to implement structured processes for gathering lessons learned, including basic tools for capturing feedback on IPD practices, client satisfaction, and stakeholder feedback. | Regularly gathers and analyzes lessons learned using established methods. Information from projects is systematically collected and reviewed. Initial steps are taken to integrate findings into project planning and feedback loops. | Effectively capture, analyze, and share lessons learned. Practices are well integrated, with clear protocols for using feedback to refine project practices. | There is innovation in the techniques and tools utilized in lessons-learned practices for the continuous capture, analysis, and application of insights aimed at improving IPD practices and outcomes. |

References

- American Institute of Architects Guide. Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide; American Institute of Architects: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mihic, M.; Sertic, J.; Zavrski, I. Integrated project delivery as integration between solution development and solution implementation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 119, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.; Mutis, I. Trends of integrated project delivery implementations viewed from an emerging innovation framework. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 989–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.W.; Hanna, A.; Kievet, D. Quantitative Comparison of Project Performance between Project Delivery Systems. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Johnson, A. Motivation and Means: How and Why IPD and Lean Lead to Success; Report; Lean Construction Institute and Integrated Project Delivery Alliance: Arlington, VA, USA; Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2016; Available online: http://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/198897 (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Poirier, E.; Arar, A.J.; Staub-French, S.; Zadeh, P.; Bhonde, D. Investigating Factors Leading to IPD Project Success in Canada; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, S.; Drogemuller, R.; Omrani, S. The compatibility of existing BIM maturity models with lean construction and integrated project delivery. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B. Building Information Modelling Maturity Matrix. In Handbook of Research on Building Information Modeling and Construction Informatics: Concepts and Technologies; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 65–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarshar, M.; Haigh, R.; Finnemore, M.; Aouad, G.; Barrett, P.; Baldry, D.; Sexton, M. SPICE: A business process diagnostics tool for construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2000, 7, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, R. The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 1317–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Knackstedt, R.; Pöppelbuß, J. Developing Maturity Models for IT Management. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2009, 1, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, T.; Rosemann, M.; Freeze, R.; Kaulkarni, U. Understanding the Main Phases of Developing a Maturity Assessment Model. In Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS); Bunker, D., Campbell, B., Underwood, J., Eds.; Australasian Chapter of the Association for Information Systems, CD Rom; 2005; pp. 8–19. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/25152/ (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Rashidian, S.; Drogemuller, R.; Omrani, S. Building Information Modelling, Integrated Project Delivery, and Lean Construction Maturity Attributes: A Delphi Study. Buildings 2023, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.; Hefley, B.; Miller, S. People Capability Maturity Model (P-CMM), version 2.0; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Lainhart, J.W., IV. COBITTM: A methodology for managing and controlling information and information technology risks and vulnerabilities. J. Inf. Syst. 2000, 14, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lean Advancement Initiative. Lean Enterprise Self-Assessment Tool (LESAT), version 1.0; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lean Aerospace Initiative: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/81903 (accessed on 17 December 2023).

- Kwak, Y.H.; Ibbs, C.W. Project Management Process Maturity (PM)2 Model. J. Manag. Eng. 2002, 18, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockamy, A.; McCormack, K. The development of a supply chain management process maturity model using the concepts of business process orientation. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Building Sciences. National Building Information Modeling Standard Version 1.0. Part 1: Overview, Principles, and Methodologies; NIBS: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Standards: For Consultants & Contractors: Capital Projects: Capital Planning & Facilities: Indiana University. Capital Planning & Facilities. Available online: https://cpf.iu.edu/capital-projects/consultants-contractors/standards-archived-page.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Allison, M.; Ashcraft, H.; Cheng, R.; Klawens, S.; Pease, J. Integrated Project Delivery: An Action Guide for Leaders. 2018. Available online: http://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/201404 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Arar, A.J.; Poirier, E.; Staub-French, S. A research and development framework for integrated project delivery. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2024, 43, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslesen, A.R.; Nordheim, R.; Varegg, B.; Laedre, O. IPD in Norway. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction: Evolving Lean Construction Towards Mature Production Management Across Cultures and Frontiers, IGLC 2018, Chennai, India, 16–22 July 2018; The International Group for Lean Construction: Chennai, India, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.; Ashcraft, H.W.; Reed, D.; Khanzode, A. Integrating Project Delivery; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft, H.W. The IPD Frameworke. Available online: https://ipda.ca/site/assets/files/1075/ipd_framework.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2012).

- vom Brocke, J.; Maedche, A. The DSR grid: Six core dimensions for effectively planning and communicating design science research projects. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, J.; Pries-Heje, J.; Baskerville, R. FEDS: A Framework for Evaluation in Design Science Research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.; Chatterjee, S. Design Science Research in Information Systems. In Design Research in Information Systems; Integrated Series in Information Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 22, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann Andersen, K.; Lee, J.; Mettler, T.; Moon, M.J. Ten Misunderstandings about Maturity Models. In dg.o ’20: Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 15–19 June 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, R.; van Berlo, L. Tool for benchmarking BIM performance of design, engineering and construction firms in the Netherlands. In Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 254–263. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781849775731-5/tool-benchmarking-bim-performance-design-engineering-construction-firms-netherlands-rizal-sebastian-l%C3%A9on-van-berlo (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Lasrado, F. Self-Assessments: Conducting an Excellence Maturity Assessment for an Organisation. In Achieving Organizational Excellence: A Quality Management Program for Culturally Diverse Organizations; Lasrado, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Framework/Study Title | Citation | IPD Framework Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide | [1] | Phases: Conceptualization, criteria design, detailed design, implementation documents, agency review, buyout, construction, closeout. |

| 2 | Integrated Project Delivery: An Action Guide for Leaders | [21] | Project structuring, team composition, decision-making process, communication, risk mitigation, performance evaluation. |

| 3 | Motivation and Means: How and Why IPD and Lean Lead to Success | [6] | Context, legal/commercial, leadership/management, processes/lean, alignment/goals, building outcomes. |

| 4 | Investigating Factors Leading to IPD Project Success in Canada | [5] | Making the Case for IPD, framing the project, choosing the team, setting the context, executing the work, maintaining excellence, reaping the benefits. |

| 5 | A Research and Development Framework for Integrated Project Delivery | [22] | Choosing IPD, Framing the project, Setting the context, Executing the work, optimizing excellence, reaping the benefits. |

| 6 | IPD in Norway | [23] | Contract, technology and processes, culture. |

| 7 | Integrating Project Delivery/The Simple Framework | [24] | Integrated information, integrated organization, integrated processes, integrated building systems. |

| 8 | The IPD Framework | [24] | Macro-framework: Contract terms, business configuration; micro-framework: Operational protocols, work design, information design, team formation. |

| # | Maturity Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Initial | IPD capabilities are at their foundational level. Practices related to IPD are not yet fully developed, with limited systematic application across the project. |

| Level 2 | Defined | Basic IPD capabilities are established, although their application may still be inconsistent. Practices are in the early stages of systematic development but need further refinement for consistency. |

| Level 3 | Managed | IPD capabilities are developing steadily, with partial consistency in their application across the project. Key practices are becoming more established, though some variability and gaps may still exist in their execution. |

| Level 4 | Proficient | IPD capabilities are well developed, consistently applied, and deeply integrated into project management activities. Practices are standardized and effectively adopted across the project, demonstrating a high level of maturity. |

| Level 5 | Advanced | IPD capabilities are fully developed, integrated, and continually optimized for maximum effectiveness. Practices reflect innovation and are continuously improved to enhance project outcomes. |

| Set | Capability | Capability Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding and facilitation | IPD comprehension | (1) Understanding of IPD principles and processes, (2) recognition of the relevance of IPD to project success, (3) integration of IPD in execution, and (4) adaptation of IPD practices based on project needs. |

| Facilitation | (1) Assessment of gaps in understanding of IPD practices, (2) training of on IPD tools, (3) effectiveness of facilitation in enhancing IPD understanding, and (4) contribution of facilitation to culture establishment. | |

| Building and sustaining teams | (1) Establishment of team culture, (2) implementation of flat hierarchy, (3) open communication, (4) encouragement of participation, and (5) continuous improvement of team-building methods. | |

| Goal setting and contract development | Developing project goals (validation process) | (1) Validation process, (2) collaboration in validation, (3) participation in validation, (4) impact of validation on team culture, (5) defining project goals, (6) clarity and comprehensiveness of validation report, and (7) introduction of new methods in validation. |

| Defining project values | (1) Defining core values, (2) communication of values, (3) reference to values in decision-making, (4) revisitation of values, and (5) strengthening of values through new methods. | |

| Contract formulation | (1) Participation in contract formulation, (2) integration of all IPD principles, (3) utilization of facilitation means, and (4) contract optimization. | |

| Project governance | Defining roles and responsibilities | (1) Definition of roles and responsibilities, (2) overlaps and conflicts, (3) discussion of roles and responsibilities, (4) communication of roles and responsibilities, (5) understanding of roles and accountability, and (6) adaptation of roles. |

| Establishing decision-making process | (1) Inclusion in decision-making, (2) transparency in decision-making, (3) guidance by project goals, (4) use of decision tools, (5) decision outcomes, (6) documentation of decisions, and (7) adaptability and agility in decision-making. | |

| Establishing management structure | (1) Defining management structure, (2) coordination of activities across management levels, (3) coordination of decisions, (4) adaptability of management strategies, and (5) integration of new management strategies. | |

| Owner involvement | (1) Involvement in decision-making, (2) involvement in day-to-day operations, (3) role in project governance, (4) support for the IPD model, (5) contribution to collaborative environment, (6) contribution to team culture, and (7) leadership. | |

| Operational excellence | Operational culture | (1) Promotion of lean practices, (2) support for a collaborative work environment, (3) adoption of a no-blame culture, (4) assessment and implementation of practices enhancing lean culture, and (5) encouragement of new methods to enhance collaborative culture. |

| Operational principles | (1) Streamlining of workflows, (2) emphasis on waste reduction, (3) emphasis on value maximization, (4) emphasis on continuous improvement, (5) integration of lean and IPD principles, and (6) role of operational principles in advancing project management practices. | |

| Tools | (1) Use of BIM, (2) enhancement of collaboration and communication through BIM, (3) BIM as information source, (4) BIM’s role in information quality, (5) use of lean tools, and (6) integration of lean tools and techniques into operational practices. | |

| Dynamics | (1) Structuring of multidisciplinary teams, (2) flexibility of team formations, (3) definition of responsibilities within teams, (4) decision-making authority within teams, and (5) cross-disciplinary collaboration. | |

| Engagement | (1) Use of formal communication, (2) direct and informal engagement, (3) communication and engagement strategies, and (4) continuous improvement of engagement techniques and strategies. | |

| Work environment | (1) Frequency of big room meetings, (2) big room setup, (3) impact of big room sessions on engagement, (4) impact of big room sessions on team unity, (5) impact of big room sessions on collaboration, and (6) incorporation of advanced tools and techniques in big room settings. | |

| Management and oversight | Information management | (1) Information structure, (2) information sharing, (3) access to data, and (4) use of advanced technologies to enhance data utilization and support decision-making. |

| Financial practices | (1) Integrating team members in financial discussions, (2) financial transparency, (3) financial responsibility, (4) use of incentive mechanisms, (5) role of incentive mechanisms in collaboration and performance enhancement, and (6) financial decision-making tools. | |

| Risk practices | (1) Risk management practices inclusivity, (2) frequency of risk management practices, (3) use of collaborative tools, (4) risk ownership, and (5) improvement of risk management practices. | |

| Performance monitoring | (1) Use of dashboards, (2) data collection and analysis, (3) adaptation of metrics, (4) the role of metrics in decision-making, and (5) data and metrics updates. | |

| Continuous learning | Continuous learning and improvement | (1) Capture of lessons learned, (2) analysis of IPD practices feedback, (3) analysis of stakeholder feedback, (4) assessment of client satisfaction, (5) feedback integration, and (6) continuous improvement in feedback capturing and utilization. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arar, A.J.; Poirier, E.; Staub-French, S. A Capability Maturity Model for Integrated Project Delivery. Buildings 2025, 15, 1733. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101733

Arar AJ, Poirier E, Staub-French S. A Capability Maturity Model for Integrated Project Delivery. Buildings. 2025; 15(10):1733. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101733

Chicago/Turabian StyleArar, Ahmad J., Erik Poirier, and Sheryl Staub-French. 2025. "A Capability Maturity Model for Integrated Project Delivery" Buildings 15, no. 10: 1733. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101733

APA StyleArar, A. J., Poirier, E., & Staub-French, S. (2025). A Capability Maturity Model for Integrated Project Delivery. Buildings, 15(10), 1733. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101733