Motivating Green Knowledge Behavior by Mindfulness Leadership in Engineering Design: The Role of Moral Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Green Behaviors in Engineering Project Design Organizations

2.2. Mindfulness Leadership and Green Behaviors

2.3. Mindfulness Leadership and Moral Identity

2.4. Moral Identity and Green Behaviors

2.5. The Mediating Role of Moral Identity

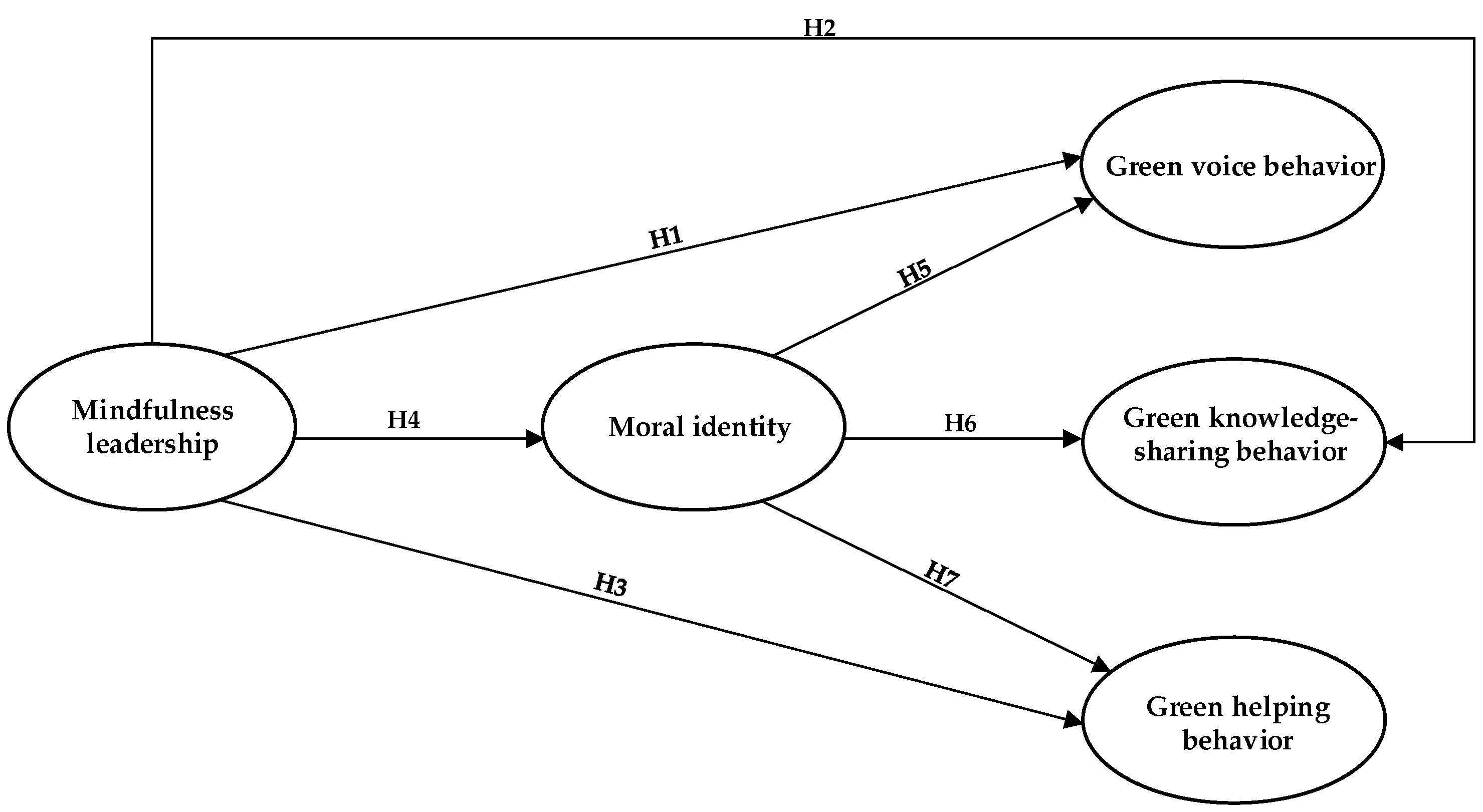

- and Figure 1

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussions and Implications

5.1. Major Findings and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozorhon, B. Analysis of Construction Innovation Process at Project Level. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoh, A.A.; Adefemi, A.; Ibewe, K.I.; Etukudoh, E.A.; Ilojianya, V.I.; Nwokediegwu, Z.Q.S. Green Architecture and Energy Efficiency: A Review of Innovative Design and Construction Techniques. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elforgani, M.S.; Rahmat, I.B. The Influence of Design Team Attributes on Green Design Performance of Building Projects. Environ. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elforgani, M.S.A.; Alabsi, A.A.; Alwarafi, A. Strategic Approaches to Design Teams for Construction Quality Management and Green Building Performance. Buildings 2024, 14, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Qian, Q. How Engineering Designers’ Social Relationships Influence Green Design Intention: The Roles of Personal Norms and Voluntary Instruments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zozul’ak, J.; Zozul’aková, V. Ethical and Ecological Dilemmas of Environmental Protection. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2022, 30, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Sadiq, M.; Kaleem, A. Promoting Green Behavior through Ethical Leadership: A Model of Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ul-Durar, S.; Akhtar, M.N.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. How Does Responsible Leadership Affect Employees’ Voluntary Workplace Green Behaviors? A Multilevel Dual Process Model of Voluntary Workplace Green Behaviors. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 296, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Ying, M.; Mehmood, S.A. The Interplay of Green Servant Leadership, Self-Efficacy, and Intrinsic Motivation in Predicting Employees’ pro-Environmental Behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering Employee’s pro-Environmental Behavior through Green Transformational Leadership, Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C.; Hülsheger, U.R.; Kudesia, R.S.; Sankaran, S.; Wang, L. Mindfulness in Projects. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2023, 4, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M. Managing Construction Projects; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yu, T.; Li, A. How Does Mindful Leadership Promote Employee Green Behavior? The Moderating Role of Green Human Resource Management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5296–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmed, I.; Mahmood, K. Promoting In-Role and Extra-Role Green Behavior through Ethical Leadership: Mediating Role of Green HRM and Moderating Role of Individual Green Values. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Crawford, J.; Turkmenoglu, M.A.; Farao, C. Green Inclusive Leadership and Employee Green Behaviors in the Hotel Industry: Does Perceived Green Organizational Support Matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.W.; Chan, R.Y. Why and When Do Consumers Perform Green Behaviors? An Examination of Regulatory Focus and Ethical Ideology. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Z. Fostering Constructive Deviance by Leader Moral Humility: The Mediating Role of Employee Moral Identity and Moderating Role of Normative Conflict. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, L.; He, M.; Yao, Y. How Does Ethical Leadership Influence Work Engagement in Project-Based Organizations? A Sensemaking Perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 45, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, J. Effect of Knowledge Leadership on Knowledge Sharing in Engineering Project Design Teams: The Role of Social Capital. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Meng, J. Alleviating Knowledge Contribution Loafing among Engineering Designers by Ethical Leadership: The Role of Knowledge-Based Psychological Ownership and Emotion Regulation Strategies. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ma, G.; Wang, D.; Jia, J. How Inclusive Leadership Influences Voice Behavior in Construction Project Teams: A Social Identity Perspective. Proj. Manag. J. 2023, 54, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peráček, T.; Kaššaj, M. Legal Easements as Enablers of Sustainable Land Use and Infrastructure Development in Smart Cities. Land 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, P.K.; Wilkinson, A.; Tse, H.H. An Integrative Review of Employee Voice: Identifying a Common Conceptualization and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Kundi, Y.M.; Becker, A. Green Human Resource Management in Nonprofit Organizations: Effects on Employee Green Behavior and the Role of Perceived Green Organizational Support. Pers. Rev. 2022, 51, 1788–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinsel, S. An Empirical Study on An Organized Industrial Zone: Investigating the Intermediary Function of Green Voice Behavior in the Connection between Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Performance. Sos. Mucit Acad. Rev. 2023, 4, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M.; Rüegger, S.; Holzer, M.; Oghazi, P. The “Golden” Voice of “Green” Employees: The Effect of Private Environmental Orientation on Suggestions for Improvement in Firms’ Economic Value Creation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elforgani, M.S.A.; Alnawawi, A.; Rahmat, I.B. The Association between Client Qualities and Design Team Attributes of Green Building Projects. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2014, 9, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, S.; Ho, S.H.; Han, I. Knowledge Sharing Behavior of Physicians in Hospitals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2003, 25, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Martínez, D.; Cantero Gómez, M.R.; Valls, E.; Puig, R. Circular Economy: The Case of a Shared Wastewater Treatment Plant and Its Adaptation to Changes of the Industrial Zone over Time. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shahzad, M.; Ali, A.; Razzaq, A. Synergistic Effect of Green Knowledge Sharing and Green Creative Climate for Circular Economy Practices: Role of Artificial Intelligence Information Quality. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Park, D.-H. The Effects of Network Sharing on Knowledge-Sharing Activities and Job Performance in Enterprise Social Media Environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafait, Z.; Huang, J. Examining the Impact of Sustainable Leadership on Green Knowledge Sharing and Green Learning: Understanding the Roles of Green Innovation and Green Organisational Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 457, 142402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.S. Environmental Requirements, Knowledge Sharing and Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from the Electronics Industry in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-H.; Huang, J.-K.; Zhao, J.; Wu, P. Open Innovation: The Role of Organizational Learning Capability, Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2019, 1, 260–272. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Xue, Y. Subjective Well-Being, Knowledge Sharing and Individual Innovation Behavior: The Moderating Role of Absorptive Capacity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 1110–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhait, R.M.; Bani-Melhem, S.; Zeffane, R. Empowerment, Knowledge Sharing and Innovative Behaviours: Exploring Gender Differences. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1950006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paretti, M.C.; Richter, D.M.; McNair, L.D. Sustaining Interdisciplinary Projects in Green Engineering: Teaching to Support Distributed Work. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 26, 462. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, S.B.; Van der Vegt, G.S.; Molleman, E. The Relationships among Asymmetry in Task Dependence, Perceived Helping Behavior, and Trust. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.; Nauta, A. Self-Interest and Other-Orientation in Organizational Behavior: Implications for Job Performance, Prosocial Behavior, and Personal Initiative. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for Its Salutary Effects. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.P.; Barber, L.K. The Role of Mindfulness in Response to Abusive Supervision. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Chaturvedi, S. Leading Mindfully: Two Studies on the Influence of Supervisor Trait Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Performance. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P.; Viera-Armas, M.; De Blasio Garcia, G. Does Supervisors’ Mindfulness Keep Employees from Engaging in Cyberloafing out of Compassion at Work? Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Panda, T.K.; Pandey, K.K. Mindfulness at the Workplace: An Approach to Promote Employees pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Panda, T.K.; Pandey, K.K. The Effect of Employee’s Mindfulness on Voluntary pro-Environment Behaviour at the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Connectedness to Nature. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 3356–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C.; Lew, C. Mindfulness, Moral Reasoning and Responsibility: Towards Virtue in Ethical Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.C.; Zheng, M.X.; Xin, K.R.; Fernandez, J.A. The Interpersonal Benefits of Leader Mindfulness: A Serial Mediation Model Linking Leader Mindfulness, Leader Procedural Justice Enactment, and Employee Exhaustion and Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Haar, J.M.; Luthans, F. The Role of Mindfulness and Psychological Capital on the Well-Being of Leaders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornich, J.B.; Lynch, H.M. The Mindful Leader: A Review of Leadership Qualities Derived from Mindfulness Meditation. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1322507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J.; Dane, E. Mindfulness in Organizations: A Cross-Level Review. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. Karl Weick: Concepts, Style and Reflection. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 53, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Ferris, G.R. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Consequences of Leader-Member Exchange: Integrating the Past with an Eye toward the Future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; SIM, S.S.-H.; Chintakananda, K.; Bhave, D.P. Leading with Mindfulness: Exploring the Relation of Mindfulness with Leadership Behaviors, Styles, and Development. Mindfulness Organ. Found. Res. Appl. 2015, 2015, 256–284. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, K.-Y.; Thomas, C.L.; Spitzmueller, C.; Huang, Y. Being Present in Enhancing Safety: Examining the Effects of Workplace Mindfulness, Safety Behaviors, and Safety Climate on Safety Outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, G.; Reinhart, G.; Prote, J.-P.; Sauermann, F.; Horsthofer, J.; Oppolzer, F.; Knoll, D. Data Mining Definitions and Applications for the Management of Production Complexity. Procedia Cirp 2019, 81, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Feng, X. Feeling Stressed but in Full Flow? Leader Mindfulness Shapes Subordinates’ Perseverative Cognition and Reaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2024, 39, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, F.; Scherr, S.; Romer, D. Effects of Exposure to Self-Harm on Social Media: Evidence from a Two-Wave Panel Study among Young Adults. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 2422–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Talbot, D.; Paillé, P. Leading by Example: A Model of Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, D.; Zheng, X.; Liang, L.H. How and When Leader Mindfulness Influences Team Member Interpersonal Behavior: Evidence from a Quasi-Field Experiment and a Field Survey. Hum. Relat. 2023, 76, 1940–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of Halal-Friendly Destination Performances, Value, Satisfaction, and Trust in Generating Destination Image and Loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The Self-Importance of Moral Identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; Freeman, D.; Reed II, A.; Lim, V.K.; Felps, W. Testing a Social-Cognitive Model of Moral Behavior: The Interactive Influence of Situations and Moral Identity Centrality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Carter, M.J. A Theory of the Self for the Sociology of Morality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D. On Ethical Leadership Impact: The Role of Follower Mindfulness and Moral Emotions. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Ethical Leadership and Employee Green Behavior: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Soucie, K.; Alisat, S.; Curtin, D.; Pratt, M. Are Environmental Issues Moral Issues? Moral Identity in Relation to Protecting the Natural World. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A. Moral Cognition and Moral Action: A Theoretical Perspective. Dev. Rev. 1983, 3, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.-T.; Chen, S.-C.; Lee, W.-C. How Does Moral Identity Promote Employee Voice Behavior? The Roles of Work Engagement and Leader Secure-Base Support. Ethics Behav. 2022, 32, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, Z. Employee-Oriented HRM and Voice Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Moral Identity and Trust in Management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 746–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M.; Shao, R.; Lam, L.W. Ethical Leadership and Employee Knowledge Sharing: Exploring Dual-Mediation Paths. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-L. How Ethical Leadership Promotes Knowledge Sharing: A Social Identity Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, T.; de França Carvalho, J.V. Would You Help Me Again? The Role of Moral Identity, Helping Motivation and Quality of Gratitude Expressions in Future Helping Intentions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 196, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Aquino, K.; Mittal, V.; Swartz, R. When Moral Identity Symbolization Motivates Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Recognition and Moral Identity Internalization. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, B.G.; Godwin, L.N. The Antecedents of Moral Imagination in the Workplace: A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1989, 14, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Choi, S.-Y. “Does a Good Company Reduce the Unhealthy Behavior of Its Members?”: The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification and the Moderating Effect of Moral Identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Usher, E.L. Social Cognitive Theory and Motivation. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, 2nd ed.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. The Foundations of Research; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Pollard, D.E. An Encyclopaedia of Translation: Chinese-English, English-Chinese; Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2001; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and Voice Extra-Role Behaviors: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P. To Share or Not to Share: Modeling Tacit Knowledge Sharing, Its Mediators and Antecedents. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Earley, P.C.; Lin, S.-C. Impetus for Action: A Cultural Analysis of Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Chinese Society. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of market research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Ng, F.; Li, J. A Parallel Multiple Mediator Model of Knowledge Sharing in Architectural Design Project Teams. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and Sustainability: Correlation or Causation? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, E.L.; Manning, C.M.; Scott, B.A. Mindfulness and Sustainable Behavior: Pondering Attention and Awareness as Means for Increasing Green Behavior. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T.; Kjønstad, B.G.; Barstad, A. Mindfulness and Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Fry, L.W. A Framework for Leader, Spiritual, and Moral Development. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 184, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Bashir, F. Having a Green Identity: Does pro-Environmental Self-Identity Mediate the Effects of Moral Identity on Ethical Consumption and pro-Environmental Behaviour? (Tener Una Identidad Verde?‘ La Identidad Propia Respetuosa Con El Medioambiente Sirve de Mediadora Para Los Efectos de La Identidad Moral Sobre El Consumo Ético y La Conducta Respetuosa Con El Medio Ambiente?). Stud. Psychol. 2020, 41, 612–643. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Ceranic, T.L. The Effects of Moral Judgment and Moral Identity on Moral Behavior: An Empirical Examination of the Moral Individual. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. Calm down and Enjoy It: Influence of Leader-Employee Mindfulness on Flow Experience. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, J.F.W.; Pircher Verdorfer, A.; Kugler, K.G. Mindfulness and Leadership: Communication as a Behavioral Correlate of Leader Mindfulness and Its Effect on Follower Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.R.; Park, S.; Chaudhuri, S. Mindfulness Training in the Workplace: Exploring Its Scope and Outcomes. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, J.M.; van Berkel, J.; Boot, C.R.; Bosmans, J.E.; Proper, K.I.; Bongers, P.M.; Van Der Beek, A.J.; van Tulder, M.W.; van Wier, M.F. Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness and Return-on-Investment of a Mindfulness-Based Worksite Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 133 | 49.8% |

| Female | 134 | 50.2% | |

| Age | Below 25 | 40 | 15.0% |

| 26–35 | 42 | 15.7% | |

| 36–45 | 106 | 39.7% | |

| Above 45 | 79 | 29.6% | |

| Education level | Below junior college | 39 | 14.6% |

| Undergraduate | 43 | 16.1% | |

| Postgraduate | 117 | 43.8% | |

| PhD | 68 | 25.5% | |

| Position | General employees | 34 | 12.7% |

| Line manager | 70 | 26.3% | |

| Middle manager | 101 | 37.8% | |

| Senior manager | 62 | 23.2% | |

| Work experience | 0–5 | 30 | 11.2% |

| 6–10 | 67 | 25.1% | |

| 11–15 | 111 | 41.6% | |

| >15 | 59 | 22.1% |

| Constructs and Items | Factor Loading | CR | Cronbach’s α | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness leadership | 0.936 | 0.923 | 0.620 | |

| 1. I have my supervisor’s full attention when I am speaking. | 0.761 | |||

| 2. In conversations, my supervisor is impatient. | 0.815 | |||

| 3. My supervisor is only half-listening when I am talking. | 0.831 | |||

| 4. In conversations, my supervisor first listens to what I have to say, before forming his/her own opinion. | 0.762 | |||

| 5. Before I have finished talking, my supervisor has already formed his/her own opinion. | 0.792 | |||

| 6. My supervisor has a preconceived opinion about many topics and holds on to this opinion. | 0.778 | |||

| 7. My supervisor stays calm even in tense situations. | 0.768 | |||

| 8. My supervisor gets easily worked up. | 0.810 | |||

| 9. When my supervisor does not like something, emotions can easily boil over. | 0.764 | |||

| Moral identity | 0.943 | 0.935 | 0.562 | |

| 1. It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics. | 0.735 | |||

| 2. Being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am. | 0.740 | |||

| 3. A big part of my emotional well-being is tied up in having these characteristics. | 0.761 | |||

| 4. I would be ashamed to be a person who has these characteristics. | 0.771 | |||

| 5. Having these characteristics is not really important to me. | 0.766 | |||

| 6. Having these characteristics is an important part of my sense of self. | 0.734 | |||

| 7. I strongly desire to have these characteristics. | 0.763 | |||

| 8. I often buy products that communicate the fact that I have these characteristics. | 0.758 | |||

| 9. I often wear clothes that identify me as having these characteristics. | 0.741 | |||

| 10. The types of things I do in my spare time (e.g., hobbies) clearly identify me as having these characteristics. | 0.686 | |||

| 11. The kinds of books and magazines that I read identify me as having these characteristics. | 0.755 | |||

| 12. The fact that I have these characteristics is communicated to others by my membership in certain organizations. | 0.792 | |||

| 13. I am actively involved in activities that communicate to others that I have these characteristics. | 0.741 | |||

| Green voice behavior | 0.915 | 0.861 | 0.781 | |

| 1. I make recommendations concerning environmental issues which affect my work. | 0.886 | |||

| 2. I speak up and encourage others to get involved in issues that affect the environment. | 0.873 | |||

| 3. I communicate my opinions about green work issues to others even my opinions are different and others at work disagree with me. | 0.893 | |||

| Green knowledge-sharing behavior | 0.911 | 0.870 | 0.720 | |

| 1. I share my environmental job-related experience with my co-workers. | 0.869 | |||

| 2. I share my environmental expertise at the request of my co-workers. | 0.822 | |||

| 3. I share my ideas about environmental issues with my co-workers. | 0.851 | |||

| 4. I talk about my tips on environmental issues with my co-workers. | 0.851 | |||

| Green helping behavior | 0.917 | 0.880 | 0.735 | |

| 1. I am willing to help my co-workers to solve environmental-related issues. | 0.874 | |||

| 2. I am willing to coordinate and communicate with my co-workers on environmental issues. | 0.852 | |||

| 3. I am willing to cover environmental work-related assignments for co-workers when needed. | 0.848 | |||

| 4. I am willing to assist new colleagues to adjust to the environmental work-related issues. | 0.856 |

| MI | ML | GVB | GKSB | GHB | |

| MI | |||||

| ML | 0.388 | ||||

| GVB | 0.519 | 0.494 | |||

| GKSB | 0.550 | 0.473 | 0.561 | ||

| GHB | 0.647 | 0.575 | 0.622 | 0.734 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Qi, Y.; Cheng, J. Motivating Green Knowledge Behavior by Mindfulness Leadership in Engineering Design: The Role of Moral Identity. Buildings 2025, 15, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101602

Wang M, Qi Y, Cheng J. Motivating Green Knowledge Behavior by Mindfulness Leadership in Engineering Design: The Role of Moral Identity. Buildings. 2025; 15(10):1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101602

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Minghui, Yiming Qi, and Jiajia Cheng. 2025. "Motivating Green Knowledge Behavior by Mindfulness Leadership in Engineering Design: The Role of Moral Identity" Buildings 15, no. 10: 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101602

APA StyleWang, M., Qi, Y., & Cheng, J. (2025). Motivating Green Knowledge Behavior by Mindfulness Leadership in Engineering Design: The Role of Moral Identity. Buildings, 15(10), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101602