Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity in the UNESCO Heritage Regulatory Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

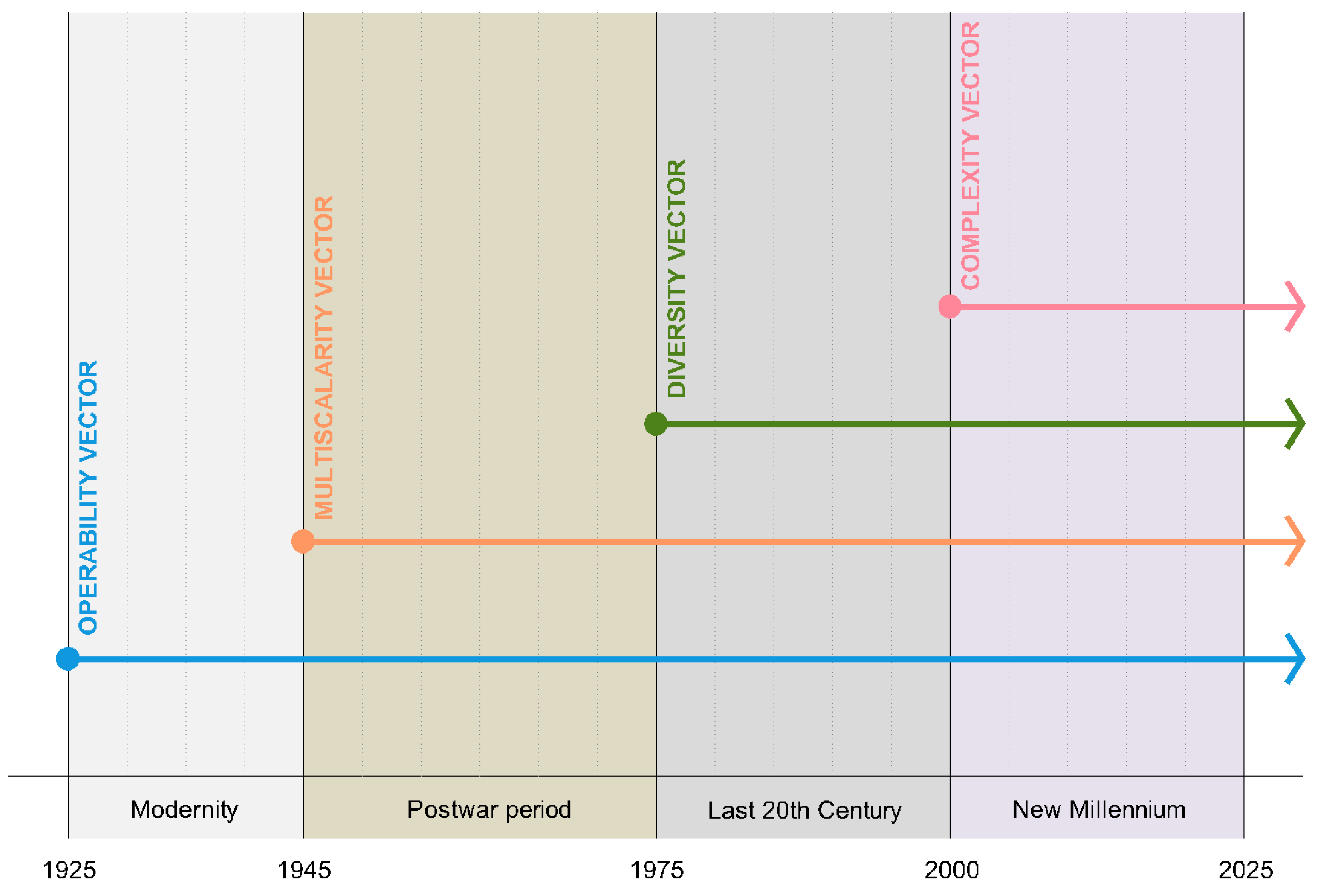

- In the first phase, we revisit UNESCO Charters and Conventions, identifying the four main themes around which we can build an understanding of the heritage phenomenon: Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity. These constitute the four main vectors that cut across heritage. We trace their origin and emergence, corresponding to specific socio-cultural moments, and identify their various nuances and facets through a detailed study of legislative documents.

- In a second phase, we identify and analyze the evolution, scope, and permanence of vectors, exploring all their facets and nuances in UNESCO Charters and Conventions from their origin to the present day.

- Finally, we cross and analyze these vectors in the discussion, revealing the relationships, interactions, and thus mutual influence between them.

1.1. First Phase. Identification of Cross-Cutting Vectors and Dimensions in Heritage: Emergence, Scope, Facets, and Nuances

1.1.1. Phase 1a. The Emergence of Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity Vectors in Understanding Heritage

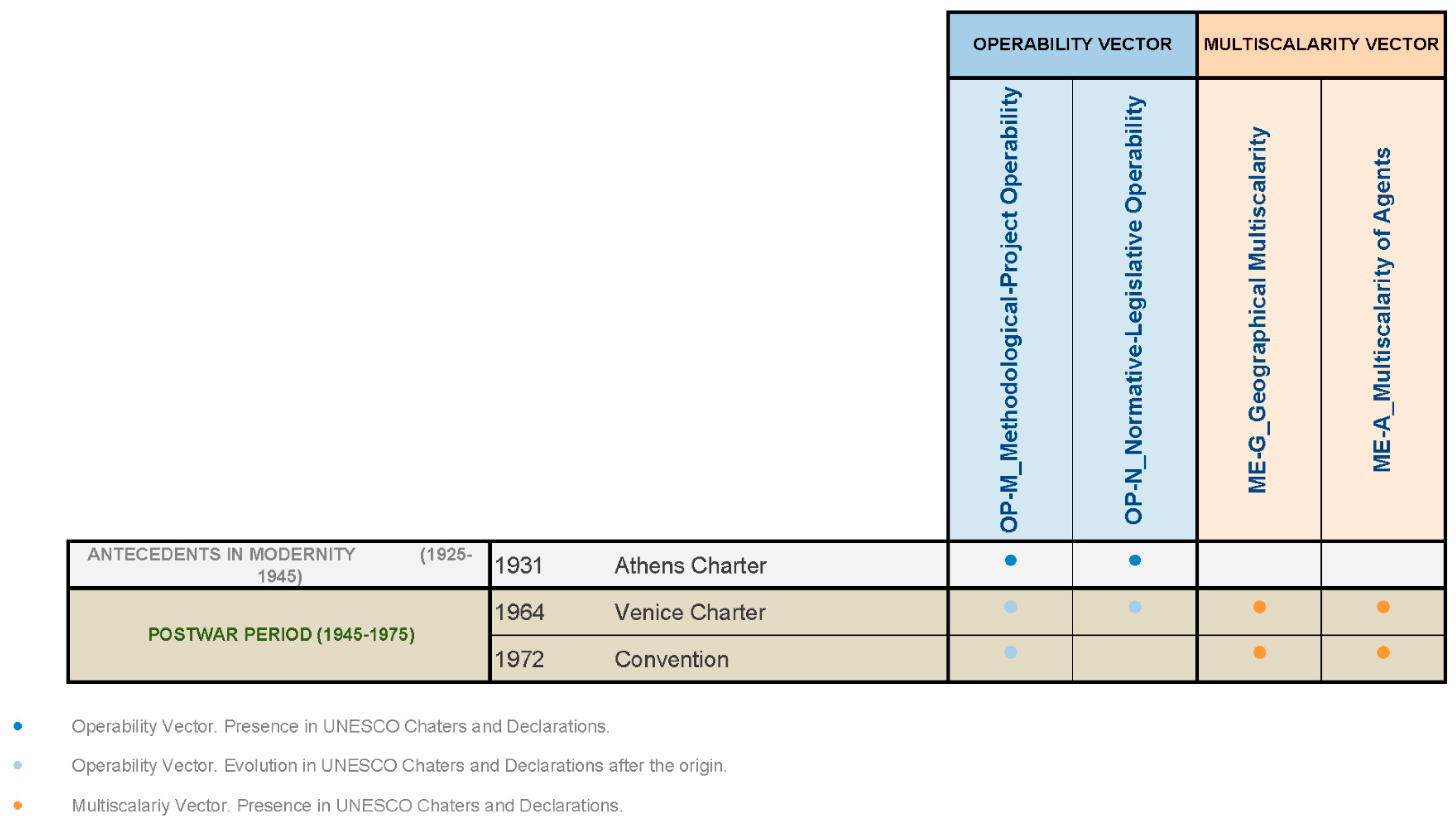

- First, we trace the emergence of Operability (OP) in the autonomous spaces of Modernity. Notably, during this era of unwavering confidence in rational knowledge, experts with technical profiles became concerned with legislating and managing heritage through the implementation of initiatives and policies aimed at its preservation. In the initial UNESCO Charters and Declarations, continuous references to strategies, actions, and recommendations for safeguarding heritage were noted. Initially, we still find an operational focus applied to defending monumental heritage.

- With the emergence of individual spaces in the post-war period, we observe the emergence of a need for Multiscalarity (MS). In the Charters and Declarations of that time, we begin to notice that heritage cannot be fully understood if reduced to a single scale of analysis. The multiscalar approach recognizes the heritage phenomenon beyond its unitary and one-dimensional nature, addressing a network of multiple dimensions manifesting at different scales, levels, and perspectives simultaneously.

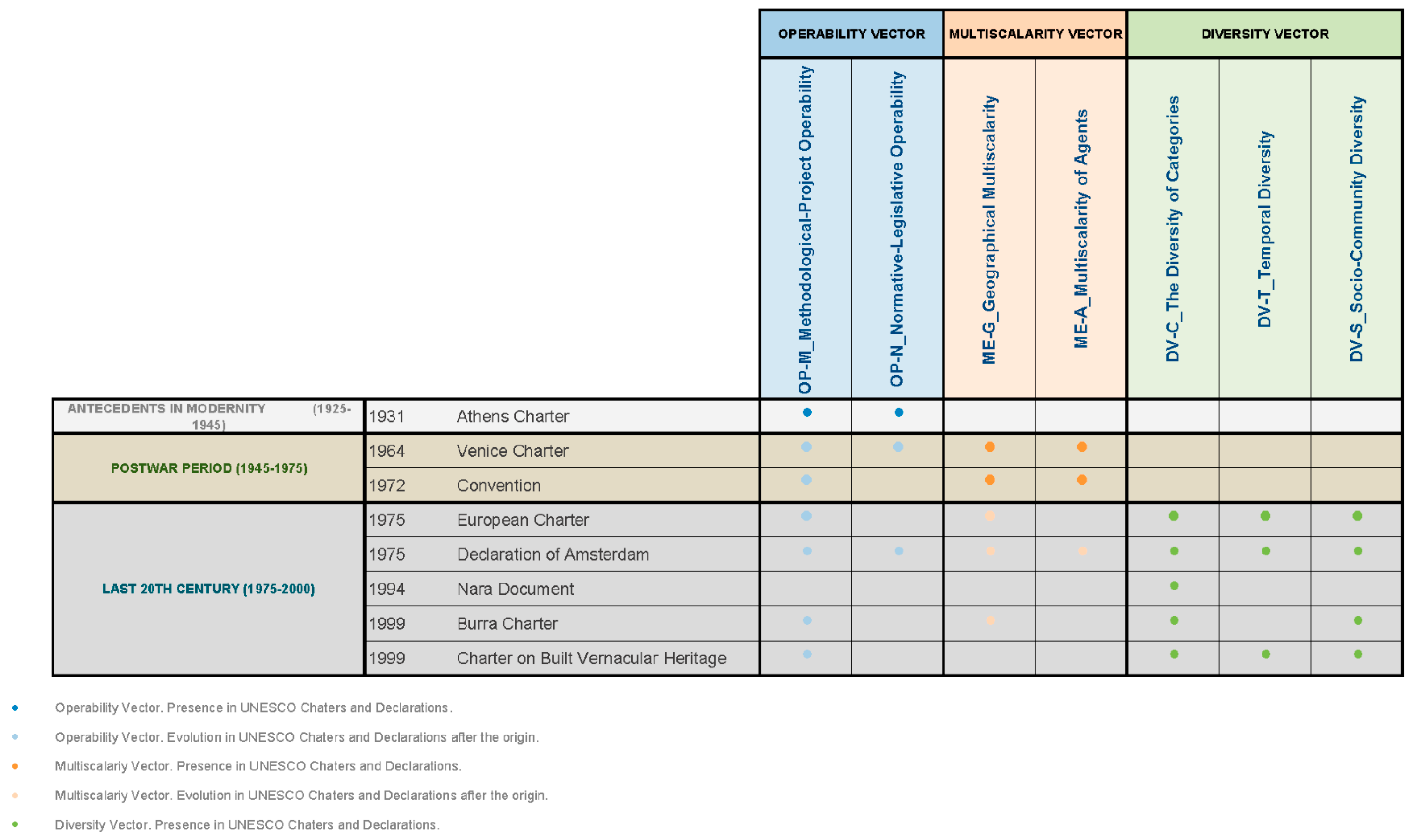

- Overcoming Eurocentrism at the end of the 20th century leads to the awareness of the Diversity Vector (DV). Charters and Declarations of this socio-cultural context begin to refer to heritage, encompassing the richness of cultural expressions, both material and intangible, shaping the legacy inherited by every society. This diverse approach allows heritage to recognize the plurality of identities, temporalities, traditions, expressions, and manifestations.

- Finally, at the turn of the millennium, the dynamic and continuously transforming nature of heritage is recognized, along with Complexity (CP). Here, we situate all that intricate network of interrelated heritage entities built and perpetually reconstructed between communities and their environment.

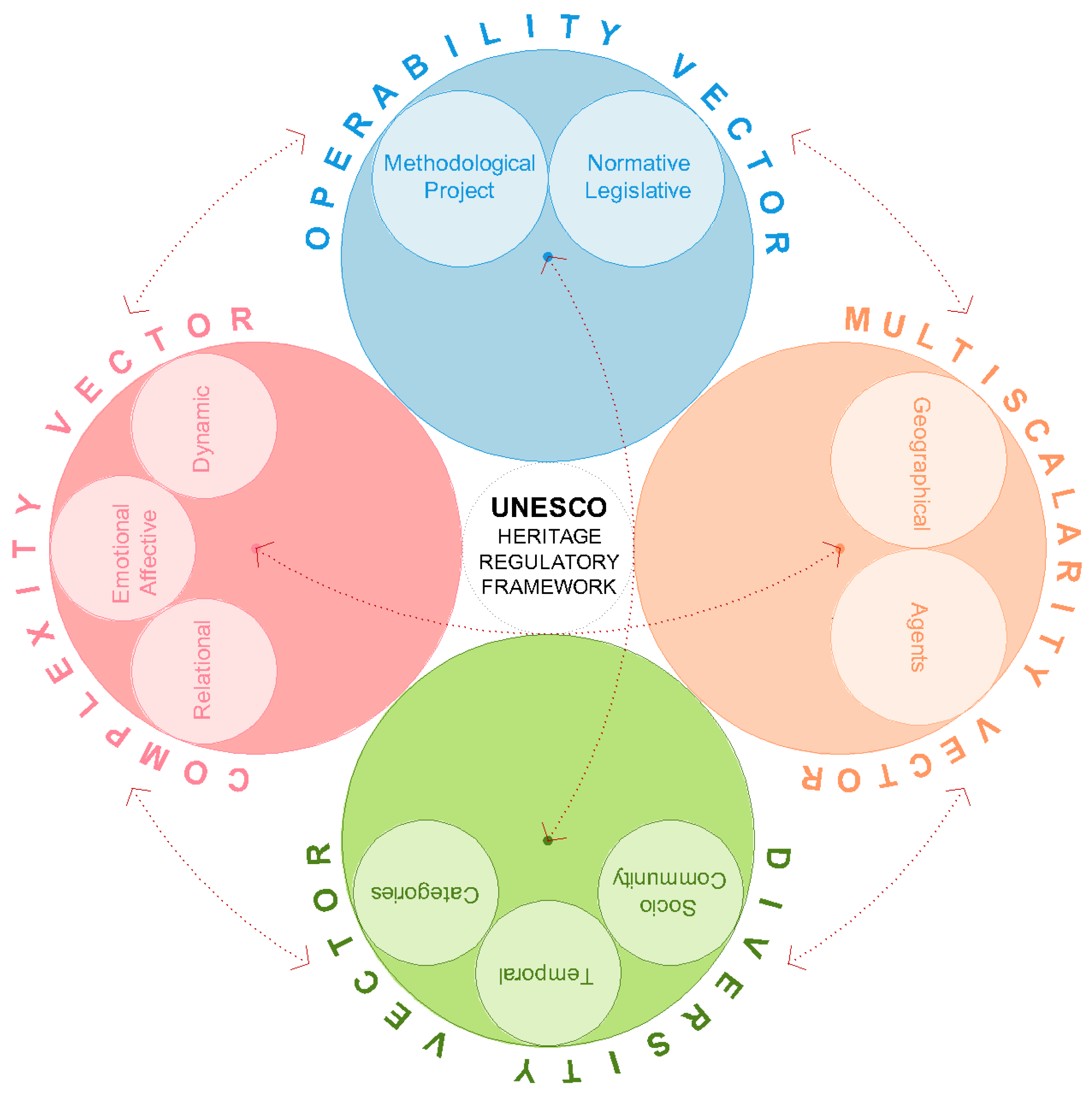

1.1.2. Phase 1b. Scope, Nuances, and Facets

- Methodological-Project Operability (OP-M): set of methodological-project-oriented elements from which heritage management emerges.

- Normative-Legislative Operability (OP-N): normative and legislative frameworks in the heritage approach.

- Geographic Multiscalarity (MS-G): considers the set of specific and concrete realities of each heritage site, transcending the concept of the abstract place of Modernity.

- Multiscalarity of Agents (MS-A): involves new agents, capable of integrating the uniqueness brought by individuals connected to specific locations. This enhances and broadens the heritage debate across disciplines, encompassing anthropology or sociology, among other fields, thereby blurring the only formal valuations and placing the individual at the forefront.

- Temporal Diversity (DV-T): considers every temporal period, blurring hierarchies between historical moments.

- Diversity of Categories (DV-C): explicitly and rapidly incorporates new heritages: vernacular, intangible, modest, industrial heritage, etc.

- Socio-Community Diversity (DV-S): consolidates the role, first of the individual, then of the collective, and finally of the community, in heritage debates.

- Emotional-Affective Complexity (CP-E): incorporates reflection, memory and emotion into the approach to heritage.

- Relational Complexity (CP-R): focuses on the relational interconnection between communities and their heritage environments, moving beyond the location of values in objects or subjects, to focus on the relationship that occurs between them.

- Dynamic Complexity (CP-D): acknowledges the dynamic and living nature of heritage.

1.2. Second Phase. Location, Permanence, and Evolution of Vectors and Dimensions in UNESCO Charters and Declarations

1.3. Third Phase. Crossovers and Vector Operations

1.4. Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Operability in Modernity. The Role of the Expert Figure

- The first arises from methodological and project-oriented mechanisms (OP-M).

- The second, from the formulation and development of normative and legal frameworks (OP-N).

2.1.1. Methodological-Project Operability

2.1.2. Normative-Legislative Operability

“The Conference heard the statement of legislative measures devised to protect monuments of artistic, historic, artistic or scientific interest and belonging to the different countries. It unanimously approved the general tendency which, in this connection, recognizes a certain right of the community in regard to private ownership. […] measures […] should be in keeping with local circumstances and with the trend of public opinion”(OP-N) [2] (p. 1)

2.2. Heritage Multiscalarity after the Post-War Period. Beyond the Universal Object in an Abstract Space

- On the one hand, this implies transcending heritage as a solitary, universal monumental object, and instead considering specific places and their surrounding environments, from the most immediate to their urban or rural contexts. This results in a geographical multiscalarity (MS-G) within the heritage of the built environment.

- On the other hand, the experience and perception of the individual within a specific reality became central to the valuation of these places. This introduces a wide range of stakeholders into the heritage debate (MS-A), extending beyond objective-centered and formal assessments. With these new stakeholders comes the recognition of their own experiences within the “place”, marking a shift from formal analysis to a more sensible approach. Ultimately, it is the experienced place that supersedes the conceptualized space.

2.2.1. Geographical Multiscalarity: Moving beyond the Isolated Monument

- Monuments: (…).

- Groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science,

- Sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view” (MS-G) [6] (p. 2).

2.2.2. Multiscalarity of Agents. Transitioning from Formal Analysis to a New Sensitive Approach in the Latter Half of the 20th Century

2.3. The Diversity Vector at the End of the Century. The Conquest of Global Diversity

- First, temporal hierarchies in time valuation become blurred (DV-T);

- Second, the boundaries of heritage expand with an enhanced focus on intangible aspects (DV-C);

- Finally, the community’s role as a central agent in heritage preservation and recognition is acknowledged (Socio-community diversity).

2.3.1. Temporal Diversity

“The past as embodied in the architectural heritage provides the sort of environment indispensable to a balanced and complete life. In the face of a rapidly changing civilization, in which brilliant successes are accompanied by grave perils, people today have an instinctive feeling for the value of this heritage. This heritage should be passed on to future generations in its authentic state and in all its variety as an essential part of the memory of the human race. Otherwise, part of man’s awareness of his own continuity will be destroyed”(DV-T) [7] (p. 2)

2.3.2. The Diversity of Categories

“(…) an important landmark in the evolution of European thinking about the conservation of the architectural heritage, acknowledging the role of human history within built groups of buildings. It calls for abolishing a hierarchical difference between groups of buildings of outstanding artistic interest and those of lesser importance”(DV-C) [8] (p. 1)

“The European architectural heritage consists not only of our most important monuments: it also includes the groups of lesser buildings in our old towns and characteristic villages in their natural or manmade settings”(DV-C) [7] (p. 2)

“Today it is recognized that entire groups of buildings, even if they do not include any example of outstanding merit, may have an atmosphere that gives them the quality of works of art”(DV-C) [7] (p. 2)

“All cultures and societies are rooted in particular forms and tangible and intangible means of expression, which constitute their heritage, and these should be respected”(DV-C) [9] (p. 1)

“Built Vernacular Heritage is the fundamental expression of the culture of a community, of its relationship with its territory and, at the same time, the expression of the world’s cultural diversity”(DV-C) [10] (p. 1)

2.3.3. Socio-Community Diversity

“In the face of a rapidly changing civilization, in which brilliant successes are accompanied by grave perils, people today have an instinctive feeling for the value of this heritage. This heritage should be passed on to future generations in its authentic state and in all its variety as an essential part of the memory of the human race. Otherwise, part of man’s awareness of his own continuity will be destroyed”(DV-S) [7] (p. 2)

2.4. The Complexity Vector in the New Millennium: Transitioning from the Subject’s Experiential and Emotional-Affective Interaction to a Dynamic Understanding of Heritage

- First, it encompasses emotions, construed in their reflective sense and grounded in the individual’s learned memory, as well as affections, in their unreflective sense (CP-E).

- Second, it emphasizes the relational understanding of communities and their respective heritage contexts (CP-R), transcending the approach of situating heritage values solely within objects or individuals to focus on the interplay and interconnectedness between them.

- Last, it embraces the dynamic and living nature of heritage (CP-D), arising from its emotional, unreflective, and affective nature, as well as the myriad relationships and interactions that underpin the understanding of the heritage phenomenon.

2.4.1. Emotional-Affective Complexity

“[…] promote education for the protection of natural spaces and places of memory whose existence is necessary for expressing the intangible cultural heritage”(CP-E) [11] (p. 18)

“All forms of cultural heritage in Europe which together constitute a shared source of remembrance, understanding, identity, cohesion and creativity”(CP-E) [13] (p. 3)

2.4.2. Relational Complexity

“This involves making links with the built environment of the metropolis, city and town”(CP-R) [14] (p. 3)

“Taking into account the emotional connection between human beings and their environment, their sense of place, it is fundamental to guarantee an urban environmental quality of living to contribute to the economic success of a city and to its social and cultural vitality”(CP-R) [15] (p. 3)

“Landscapes as cultural heritage result from and reflect a prolonged interaction in different societies between man, nature, and the physical environment. They are testimony to the evolving relationship of communities, individuals and their environment”(CP-R) [14] (p. 3)

“Each community, by means of its collective memory and consciousness of its past, is responsible for the identification as well as the management of its heritage”(CP-R) [14] (p. 1)

“The connection between communities and their heritage should be recognized, respecting the community’s right to identify values and knowledge systems embodied in their heritage”(CP-R) [17] (p. 6)

“Because of the indivisible nature of tangible and intangible heritage and the meanings, values, and context intangible heritage gives to objects and places”(CP-R) [12] (p. 2)

“Recognizing that the spirit of place is made up of tangible (sites, buildings, landscapes, routes, objects), as well as intangible elements (memories, narratives, written documents, festivals, commemorations, rituals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colors, odors, etc.), which all significantly contribute to making place and to giving it spirit, we declare that intangible cultural heritage gives a richer and more complete meaning to heritage as a whole”(CP-R) [12] (p. 3)

“The relationship between tangible and intangible heritage, and the internal social and cultural mechanisms of the spirit of place—a term defined as the tangible (buildings, sites, landscapes, routes, objects) and the intangible elements (memories, narratives, written documents, rituals, festivals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colors, odors, etc.)”(CP-R) [12] (p. 2)

“Spirit of place is defined as the tangible and intangible, the physical and the spiritual elements that give the area its specific identity, meaning, emotion and mystery. The spirit of place creates the space and at the same time the space constructs and structures this spirit (Québec Declaration of 2008)”(CP-R) [18] (p. 3)

“We acknowledge that landscapes are an integral part of heritage as they are the living memory of past generations and can provide tangible and intangible connections to future generations. Cultural heritage and landscape are fundamental for community identity and should be preserved through traditional practices and knowledge that also guarantees that biodiversity is safeguarded”(CP-R) [17] (p. 2)

2.4.3. Dynamic Complexity

“Individual elements of this heritage are bearers of many values, which may change in time. This various specific values in the elements characterize the specificity of each heritage”(CP-D) [14] (p. 1)

“The spirit of place offers a more comprehensive understanding of the living and, at the same time, permanent character of monuments, sites, and cultural landscapes. It provides a richer, more dynamic, and inclusive vision of cultural heritage”(CP-D) [12] (pp. 2–3)

“Community identity is rarely uniform or static but is a living concept that is constantly evolving, thanks to an interplay of past and present in the context of current geo-political circumstances”(CP-D) [17] (p. 3)

3. Results

3.1. Graphic Supports and Findings of the Phase 1 Analysis

3.2. Graphic Supports and Findings of the Phase 2 Analysis

3.3. Graphic Supports and Findings of the Phase 3 Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Towards Multiscalar Operability

“The monument is inseparable from the history to which it bears witness and from the setting in which it occurs (MS-G). The moving of all or part of a monument cannot be allowed except where the safeguarding of that monument demands it or where it is justified by national or international interest of paramount importance”(OP-M) [5] (p. 2)

“Excavations should be carried out in accordance with scientific standards and the recommendation defining international principles to be applied in the case of archaeological excavation adopted by UNESCO in 1956”(OP-N) [5] (p. 3)

4.2. Towards a Diverse Multiscalarity

“Formerly limited to the most famous monuments, sites or complexes, the concept of architectural heritage today includes all groups of buildings which constitute an entity (MS-G) not only by virtue of the coherence of their architectural style but also because of the imprint of the communities which have settled there for generations (DV-T). The Congress of Amsterdam confirmed this trend of abolishing a hierarchical difference between groups of buildings of outstanding artistic interest and those of lesser importance”(DV-C) [8] (p. 1)

“Protection is needed today for historic towns, the old quarters of cities, and towns and villages with a traditional character as well as historic parks and gardens. (DV-C) (MS-G) The conservation of these architectural complexes can only be conceived in a wide perspective, embracing all buildings of cultural value, from the greatest to the humblest—not forgetting those of our own day together with their surroundings. (DV-T and DV-C) This overall protection will complement the piecemeal protection of individual and isolated monuments and sites”(MS-G) [8] (p. 4)

“The full development of a continuous policy of conservation requires a large measure of decentralization as well as a regard for local cultures. This means that there must be people responsible for conservation at all levels (central, regional and local) at which planning decisions are taken. The conservation of the architectural heritage, however, should not merely be a matter for experts. The support of public opinion is essential. (MS-A) The population, on the basis of full and objective information, should take a real part in every stage of the work, from the drawing up of inventories to the preparation of decisions”[8] (p. 6)

4.3. Towards a Diverse Operation

“To make the necessary integration possible, an inventory of buildings, architectural complexes and sites demarcating protected zones around them is required. (OP-M) It should be widely circulated, particularly among regional and local authorities and officials in charge of town and country planning, in order to draw their attention to the buildings and areas worthy of protection. Such an inventory will furnish a realistic basis for conservation as a fundamental qualitative factor in the management of space”(MS-A) [8] (p. 5)

“The recognition of the claims of the aesthetic and cultural values of the architectural heritage (DV-C) should lead to the adoption of specific aims and planning rules for old architectural complexes. It is not enough to simply superimpose, without coordinating them, ordinary planning regulations and specific rules for protecting historic buildings”(OP-N) [8] (p. 5)

4.4. Towards a Complex and Relational Diversity

“Landscapes as cultural heritage result from and reflect a prolonged interaction in different societies (DV-S) between man, nature and the physical environment (DV-C and CP-R). They are testimony to the evolving relationship of communities, individuals and their environment”(CP-R) [14] (p. 3)

“Mutual understanding and tolerance of diverse cultural expressions add to quality of life and social cohesion. Heritage resources provide an opportunity for learning, impartial interaction, and active engagement, and have the potential to reinforce diverse community bonds and reduce conflicts”(CP-R and DV-S) [19] (p. 2)

“The expanding notion of cultural heritage, in particular during the last decade, which includes a broader interpretation leading to recognition of human coexistence with the land (CP-R) and human beings in society”(DV-C) [15] (p. 2)

“Promote the objective of quality in contemporary additions to the environment without endangering its cultural values”(DV-T) [13] (p. 5)

4.5. Towards a Complex and Relational Multiscalarity

“The concept of heritage has widened considerably from monuments, groups of buildings and sites to include larger and more complex areas, landscapes, settings (MS-G), and their intangible dimensions, reflecting a more diverse approach (DV-C). Heritage belongs to all people; men, women, and children; indigenous peoples; ethnic groups; people of different belief systems; and minority groups (DV-S). It is evident in places ancient to modern; rural and urban; the small, everyday, and utilitarian; as well as the monumental and elite. It includes value systems, beliefs, traditions and lifestyles, together with uses, customs, practices and traditional knowledge (DV-C). There are associations and meanings, records, related places, and objects. This is a more people-centered approach”(CP-R) [19] (p. 2)

“There is a close relationship between nature, culture and people (CP-R). Cultural places and landscapes, along with communities, traditional management systems and beliefs, constitute living heritage and cultural identity (CP-D). Appropriate conservation and management of living heritage is achievable through intergenerational transfer of knowledge and skills in cooperation with communities and facilitated by multidisciplinary expertise”(MS-A) [19] (p. 3)

4.6. Towards a Complex and Relational Operation

“The plurality of heritage values and diversity (DV-C) of interests necessitates a communication structure that allows, in addition to specialists and administrators, an effective participation of inhabitants in the process. It is the responsibility of communities to establish appropriate methods and structures to ensure the true participation of individuals and institutions in the decision-making process”(OP-M) [14] (p. 4)

“Community participation in planning, the integration of traditional knowledge and diverse intercultural dialogues in collaborative decision-making will facilitate well-reasoned solutions and good use of resources reflecting the four pillars of sustainability”(OP-M) [19] (p. 3)

“Laws and regulations (OP-N) should respect connections between communities and place”(CP-R) [19] (p. 2)

5. Conclusions and Research Developments

- Explore the potential of these four vectors as innovative tools for both qualitative and quantitative analysis of our heritage. These vectors can serve not only as analytical instruments for examining documents but also as methodologies for engaging with any heritage context. By utilizing these vectors, researchers can address methodological differences often encountered in the study of different types of heritage (architectural, landscape, intangible heritage, etc.). It is interesting to note, for example, the research developed by Rodríguez-Segura and Loren-Méndez in 2022 in which they reflect on the indispensable role of experiences, emotions and affects for the understanding of urban complexity based on the review of various urban-architectural methodological cases of a heritage nature [20]. These heritage competencies would undoubtedly be integrated within the Complexity Vector proposed in this research. The integration of the vectors, in their different facets and nuances, proposed in this research could substantially favor the development of another research such as the one in this example. Its methodological and instrumental convergence could reveal new future keys and new relationships between the different vectors, as well as reveal guidelines of practical applicability to integrated heritage management.

- Promote the integration of artificial intelligence, ICT and new GIS tools in this field of knowledge. On the one hand, these tools would allow the review of heritage regulatory frameworks to be substantially contrasted and amplified, revealing new facets and nuances, or even new heritage vectors; on the other hand, these novel digital tools constitute the main channel for the practical applicability of the vectors proposed in this research. Indeed, these vectors and subvectors can constitute novel metadata for future digital tools applied to heritage knowledge.

- Transfer technically and systematically the heritage methodology proposed here at all its geographical levels. In this research we have addressed a large part of the heritage regulatory framework at the regional and international level. However, the vectors and subvectors proposed here can continue to be developed and contrasted with other heritage regulatory frameworks at other scales, including the local regulations of each municipality. It would be an interesting avenue of research to assess the way in which these vectors interact with the local scale: on the one hand, it could reveal heritage deficiencies in the local regulatory framework; on the other hand, new conceptual categories could be revealed that continue to develop in this research.

- Promote informative and comprehensive work on heritage understanding beyond the expert figure. Unfortunately, the heritage regulatory framework continues to be a complex field of knowledge from a conceptual point of view, often intellectually inaccessible to citizens. The work carried out here, together with the new avenues of research that are proposed, could favor the approach to each one of the individuals of the different communities: the conceptual simplification of these regulatory frameworks would contribute to improving the pedagogical and informative work of the patrimonial notions beyond expert figures. This would contribute enormously to the empowerment of communities regarding their own heritage (that is, promoting awareness of the relational complexity of heritage) and to their integral participation in decision-making in heritage management projects.

- Delve into the implications of the Complexity Vector, particularly its implicit redefinitions within the Diversity, Multiscalarity, and Operability Vectors. This involves examining the evolution of charters towards affective-relational dimensions, which suggests an interrelational conception of heritage values. Beyond solely associating the emotional and affective aspects with intangible heritage, this research study advocates for recognizing these elements in the characterization of tangible heritage. This integration of both types of heritage highlights the organic progression of heritage towards a relational connection with people, thereby challenging prevailing assumptions about the inherent nature of tangible heritage values and meanings. This approach is particularly pertinent in the realm of architectural and urban heritage, as it enhances the study of such cases by incorporating the relational and affective dimensions traditionally associated with intangible heritage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitruvius Pollio, M. The Ten Books of Architecture; Domingo, J.L.O., Translator; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Conference of Experts on the Protection and Conservation of Monuments of Art and History. Letter from Athens. Athens Conference 1931. 1931. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Loren-Méndez, M.; Rodríguez-Segura, A.; Galán-Conde, J.M. The experiential and emotional dimension in the updated knowledge of heritage after the Cultural and Affective Turns. Its transfer to the tangible characterization of architecture. Art Individ. Soc. 2023, 35, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loren-Méndez, M.; Rodríguez-Segura, A. Genealogies of social perception: Integration of experience and emotion in the heritage valuation of our environment. In Cultural Landscapes and Social Perceptions; Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2023; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. International Charter on the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (Venice Charter of 1964). II International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historical Monuments, Venice 1964. Adopted by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in 1965. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/157-thevenice-charter (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- United Nations Organization. The 1972 World Heritage Convention. General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, at its 17th session, Paris, 17 October–21 November 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. European Charter for Architectural Heritage. 1975. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/170-european-charter-of-the-architectural-heritage (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Council of Europe. Declaration of Amsterdam. Year of European Architectural Heritage. Amsterdam. 21–25 October 1975. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/090000168092ae41 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Nara Document in Authenticity 1994. 1994. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/nara94.htm (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Built Vernacular Heritage Charter. Rarified by the 12th General Assembly, Mexico, October 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/164-charter-of-the-built-vernacular-heritage (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- United Nations Organization. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Québec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of the Place. 2008. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-646-2.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage to Society. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806a18d3 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- United Nations Organization. Krakow Charter 2000. Principles for the Conservation and Restoration of Built Heritage. 2000. Available online: https://www.triestecontemporanea.it/pag5-e.htm (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- United Nations Organization. Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture. Historic Urban Landscape Management, Vienna. 2005. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140984 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Letter from Donkey. Adopted by ICOMOS Australia for Sites of Cultural Significance on 19 August 1979. Updated 23 February 1981, 23 April 1988 and 26 November 1999. 1999. Available online: http://icomosubih.ba/pdf/medjunarodni_dokumenti/1999%20Povelja%20iz%20Burre%20o%20mjestima%20od%20kulturnog%20znacenja.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. The Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values. Declaration of the Principles and Recommendations on the Value of Cultural Heritage and Landscapes for Promoting Peaceful and Democratic Societies. 2014. Available online: https://culturapedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2014-declaracion-florencia.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Urban Populations and Areas. Adopted by the XVII ICOMOS General Assembly on 28 November 2011. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Valletta-Principles-GA-_EN_FR_28_11_2011.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy. In Proceedings of the XIX General Assembly of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017; Available online: https://culturapedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2017-declaracion-delhi.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Adrián Rodríguez-Segura, A.; Loren-Méndez, M. Emociones, afectos y experiencias en la caracterización urbano-arquitectónica. El apego al lugar en los viajes de la memoria. ZARCH 2022, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Historical-Cultural Context | Heritage Correlate | Cross-Cutting Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents in Modernity (1925–1945) | Functionalist Rationalism: Trust in Reason and the Machine | Focus on the object, which is universal and situated in an abstract realm. | Operability Vector |

| Period | Historical-Cultural Context | Heritage Correlate | Cross-Cutting Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postwar period (1948–1975) | Existentialism in the Reorganization of Western Ethical Values | The experienced place and the present condition of the history of our environment | Multiscalarity Vector |

| Cultural Turn | The expansion of the idea of heritage. Modest works with cultural significance |

| Period | Cultural Context | Heritage Correlate | Cross-Cutting Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 20th century (1975–2000) | Phenomenology | Learned cultural component of rote learning. The assumed intangibility of emotions in heritage | Diversity Vector |

| Postcolonialism | The Vernacular: Cultural Diversity as a Global Heritage Value |

| Period | Cultural Context | Heritage Correlate | Cross-Cutting Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Millennium (2000–2025) | The Affective Turn | The relational dimension and the evolution of emotions towards affections in the valuation of assets. Transcending intangibility. | Complexity Vector |

| Non-Representational Theory | The dynamic and changing nature of heritage. The continuous construction of a community-heritage environment. |

| Period | Context Cultural | Heritage Correlate | Cross-Cutting Vector | Facets and Nuances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents in Modernity (1925–1945) | Functionalist Rationalism: Trust in Reason and the Machine | Focus on the object, which is universal and located in an abstract space. | Operability (OP) | Methodological-Project (OP-M) |

| Normative-Legislative (OP-N) | ||||

| Postwar period (1945–1975) | Existentialism in the Reorganization of Western Ethical Values | The experienced place and the present condition of the history of our environment | Multiscalarity (ME) | Geographic (MS-G) |

| Cultural Turn | The expansion of the idea of heritage. Modest works with cultural significance | of Agents (MS-A) | ||

| Late 20th century (1975–2000) | Postcolonialism | The Vernacular: Cultural Diversity as a Global Heritage Value Learned cultural component of rote learning. The assumed intangibility of emotions in heritage | Diversity (DV) | Temporal (DV-T) |

| Phenomenology | Categories (DV-C) | |||

| Socio-Community (DV-S) | ||||

| New millennium (2000–2025) | The Affective Turn | The relational dimension and the evolution of emotions towards affections in the valuation of assets. Transcending intangibility. | Complexity (CP) | Emotional-Affective (CP-E) |

| Theory Non-Representational | The dynamic and changing nature of heritage. The continuous construction of a community-heritage environment. | Relational (CP-R) | ||

| Dynamics (CP-D) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Segura, A.; Loren-Méndez, M.; Galán-Conde, J.M. Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity in the UNESCO Heritage Regulatory Framework. Buildings 2024, 14, 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072146

Rodríguez-Segura A, Loren-Méndez M, Galán-Conde JM. Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity in the UNESCO Heritage Regulatory Framework. Buildings. 2024; 14(7):2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072146

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Segura, Adrián, Mar Loren-Méndez, and José María Galán-Conde. 2024. "Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity in the UNESCO Heritage Regulatory Framework" Buildings 14, no. 7: 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072146

APA StyleRodríguez-Segura, A., Loren-Méndez, M., & Galán-Conde, J. M. (2024). Operability, Multiscalarity, Diversity, and Complexity in the UNESCO Heritage Regulatory Framework. Buildings, 14(7), 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072146