Abstract

During the recent founding of Saudi Arabia in 1932, there was no interest in the urban and architectural heritage that Jeddah possesses. As a result, historic Jeddah was exposed to many problems similar to many historical Middle Eastern cities. For example, the historic city wall and many heritage buildings were demolished. With the economic recovery during the 1970s, the original dwellers abandoned the city altogether. They were soon replaced by a class of ex-patriate workers who would inhabit the area, and the city’s distinct heritage fell into neglect. At the beginning of the 1980s, attempts to preserve that area began with the expert Robert Matthew, who studied the remaining historical buildings and proposed strategies for preservation that were based on three main directions: restoration, replacement, or new construction. The issuance of “Saudi’s 2030 vision” included programs to develop Saudi cities, including Jeddah. This program includes the removal of unplanned and slum areas around historic Jeddah without developing a clear master plan for what will replace them. In addition, it includes the complete expropriation of historic Jeddah, without announcing a specific plan for what the area will be used for. Therefore, this study seeks to review current preservation strategies, with the aim of reaching results related to the challenges facing the area; demonstrating the effectiveness of the preservation strategies used; and deducing what could contribute in the future to the development, preservation, and optimal exploitation of the area, without losing its value as a result of the modernization processes currently taking place.

1. Introduction

Historic Jeddah has a distinctive architecture as a result of the many changes in its architecture it underwent throughout various historical eras.

It was influenced by Mamluk architecture and then the Ottoman architecture prevalent in most of the historical cities of the Middle East, whether in Egypt, Iraq, the Levant, or elsewhere [1].

As a result of several factors, the historical area of Jeddah witnessed urban deterioration, especially with the rapid urban expansion beginning after the founding of Saudi Arabia in 1932 with the lack of awareness of the importance of such heritage at that time. The demolition of its historical wall in 1947 [2] in particular led to an acceleration in its urban deterioration as its historical urban fabric began to be mixed with the urban fabric of the new areas. This led to a loss of its historical privacy, in addition to the loss of many heritage buildings, whether through neglect or to claims of modernization and development, without a vision or strategy to preserve the area or an awareness of its historical importance, until the end of the 1970s [3].

In addition to the above, changes in its demographic composition with the emigration of its original dwellers to more modern urban areas and their replacement by a class of foreign expatriate workers, with their lack of interest in maintenance operations for its buildings, led to further deterioration. This is the case with many historical areas in existing cities, especially in Saudi Arabia and the Arab Gulf countries [4].

With the renewed interest in this historical area, its urban fabric, and its heritage buildings, in addition to its inclusion on the World Heritage List in 2014 [5], it is necessary to review and analyze the conservation strategies already drawn up. The problems that historic Jeddah currently faces or may face in the future should be studied with the aim of achieving sustainable urban preservation, especially in the context of the comprehensive urban development projects taking place in the city within the framework of “Saudi’s 2030 vision” [6] since 2021. Such developments include the removal of the unplanned districts adjacent to historic Jeddah and their conversion to other uses without the announcement of a clear master plan and without presenting such a plan to public opinion for discussion, especially since this demolition and removal of these slums and unplanned districts around the historical area aims, as was announced, to support the historical area. Therefore, this study aims to draw attention to the selection of appropriate cultural and tourism activities to replace that removed area in order to support and preserve the historical area.

1.1. Study Purpose

This study aims to review and analyze the urban preservation strategies currently implemented in historic Jeddah and review whether or not they are sufficient. It also ad-dresses the most important challenges facing the area and the impacts related to these strategies. This comes as a result of a large project being implemented under the pretext of developing Jeddah, which includes the demolition of the unplanned districts surrounding the historic area and the expropriation of the historic area without a clear plan in place for what the area will become.

Therefore, the study examines development in the area and then proposes a set of recommendations that can be directed to those in charge of those projects and everyone who bears responsibility for preserving that area, with the aim of ensuring that any preservation is primarily in the economic, social, and urban interest of the historic area.

In addition to drawing attention to the necessity of ensuring that the development project for the historical area and its surroundings is carried out in a way that contributes to preserving and supporting the historic area by choosing appropriate activities, whether cultural, touristic, or other, it draws attention to the necessity to replace the removed slums around the historical area.

1.2. Study Significance

The importance of this study lies in the need to ascertain the effectiveness of the strategies drawn up for the urban preservation of historic Jeddah so far in addition to addressing the most important problems and challenges facing the historic area as a world heritage site.

It also highlights the necessity of defining international standards that are approved and applied globally in urban preservation operations, especially in the context of the large project aiming to develop the historic area and its surroundings, which began in 2021. The details of this project have not yet been announced, other than the removal of some of the surrounding districts and the expropriation of the historical area.

A specific and clear plan for what the region will become next was not announced, in addition to no plan being presented to the public and specialists in all fields for discussion. Therefore, it is important for this study to put forward some recommendations that may benefit decision makers in preserving the historical area and converting the surrounding area to uses that are compatible with it as an additional buffer zone. All of this is to be achieved within the framework of developing the historical region without the region as a whole losing its historical identity.

2. Materials and Methods

The study follows a theoretical and descriptive method and deals with the concepts of cultural heritage, including the characteristics and patterns of archaeological and historical areas and their distinctive character according to “the world heritage convention” from 1972 and others [7].

It also reviews how to deal with historical areas and buildings and the urban problems facing them by presenting the most important approved strategies and naming and explaining the most important international charters and institutes that sponsor them.

Then, the study moves on to present and review urban preservation plans and strategies for the historic Jeddah area as a case study of historical areas within existing Middle Eastern cities, for which the first detailed master plan to classify their heritage buildings and historical urban fabrics was prepared by appointing a specialized international consulting body between 1978 and 1979 [8,9].

After that, the study addresses the establishment of the department for the protection of historic Jeddah in 1993 and the launch of Prince Majid bin Abdelaziz’s project to take care of historic Jeddah [9]. Then, the efforts of “the Saudi commission for tourism and national heritage” to develop historic Jeddah since its establishment in 2000 are discussed, thanks to which a special file was prepared to register the area on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2011. This effort was initially met with rejection by the international organization due to several considerations related to the current state of the area at that time, which forced the Saudi government to withdraw the nomination [10].

However, this rejection motivated the Saudi Commission to develop many urgent and future plans to implement specific projects to care for, maintain, and preserve historic Jeddah’s urban heritage. These efforts succeeded in achieving Jeddah’s inclusion on the World Heritage List in 2014 [8,9].

This brings us to the current stage, in which the city of Jeddah is undergoing, through “Saudi’s 2030 vision”, several projects to develop its various districts. This involves the implementation of some modern development projects in Jeddah starting in 2021, which include the expropriation of historic Jeddah and the removal of its neighboring districts as a buffering zone.

Therefore, this study seeks to draw the attention of decision makers by making recommendations on the importance of choosing strategies that support the historical area when developing the general plan for the surrounding areas currently being dealt with, in addition to the historical area itself after its expropriation.

2.1. Definition of the Cultural Heritage

“The world heritage convention” 1972 defines cultural heritage in “Article 1” as including the following [7]:

- -

- Monuments: architectural works, works of monumental sculpture and painting, elements or structures of an archaeological nature, inscriptions, cave dwellings, and combinations of features, which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

- -

- Groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity, or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

- -

- Sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and of man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from historical, aesthetic, ethnological, or anthropological points of view.

2.2. Characteristics and Patterns of Archaeological and Historical Areas

The identity of archaeological and historical areas is formed by many components. Its buildings possess a quantitative and qualitative richness of architectural and historical styles, combining tangible features such as the urban fabric, buildings, and monuments and intangible features such as social traditions, popular culture, commercial activities, etc. The combination of all these factors becomes a multi-dimensional civilizational system. These areas also gain moral value due to the events they witnessed and the meanings associated with them. Therefore, reviving the meanings and events associated with these areas aims to reaffirm their importance in the conscience of its people and visitors [11].

Archaeological and historical areas consist of a group of urban fabrics and foci that record specific periods of the city’s stages. These foci may be in the form of markets, distinctive gates, or archaeological or historical buildings with a distinctive architectural character. They also gain their value or lack thereof based on the state of the urban fabric. Historical and archaeological areas have some other features that distinguish them, including the distinctive and authentic urban environment and the architectural features of buildings with a unique character that have the ability to carry and influence culture. In addition, distinguished urban fabrics contain a large concentration of archaeological and historical buildings characterized by a common architectural vocabulary that confirms the character of these areas [11,12].

2.3. Dealing with Archaeological and Historical Areas and Buildings in Historic Cities

2.3.1. The Urban Problems That Face Historical Areas and Buildings

The historic centers of cities are exposed to many dangers as a result of a number of factors, including increasing rates of population growth, internal and external migration to historic areas, and the increase in the number and size of modern means of transportation and their penetration into areas that were not historically designed for them. This leads to the emergence of other problems related to expanding old existing roads by demolishing historical buildings, as well as providing places to wait for these modern means of transportation [13].

In addition, the high profitability to be gained from constructing modern buildings in historical areas has led to an increase in the size and number of buildings, which exacerbates the problem of transportation and movement, such as the need to build special parking places for vehicles such as cars. In turn, increased space for transportation affects the climates and environments of these historical centers and leads to an increase in environmental pollution. These factors have led to the degradation and destruction of historical areas of high heritage value [13].

The state of imminent danger threatening these historical buildings has also been exacerbated by the neglect of maintenance and care and the community’s lack of awareness of their historical, heritage, and artistic value, and even their economic value [13,14].

Therefore, realistic scientific strategies and plans must be developed to protect and preserve buildings of historical and artistic value. This process is known as an integrated and comprehensive maintenance plan, which is followed by a repair and rehabilitation plan for buildings of historical and heritage value [14,15].

2.3.2. Rehabilitation of Historical Areas and Buildings

The rehabilitation and maintenance process essentially stems from the data on the environment in which the historical areas and buildings to be rehabilitated and maintained are located, taking into account the changes that result from the interactions of economic and social activities and the impact of these changes on the environment and buildings. Accordingly, any practical plan must give great attention to these buildings. Therefore, the process of maintenance and rehabilitation must be given preference and precedence over all other options [16], including the development option itself in its simple, abstract concept, as this process of preservation is considered in itself a development process [17]. A lack of attention to the process of regulating uses at the level of the urban environment or deficiencies in maintenance procedures lead to the destruction of valuable buildings and thus the destruction of historical areas [14].

2.3.3. Considerations for the Rehabilitation and Maintenance of Historic Areas and Buildings

It is important to understand that the maintenance process of historical or heritage buildings does not limit or reduce the standard of living of their residents. There must also be some kind of preparation to meet the requirements of the modern lifestyle. For example, if it is necessary for residents of historical areas to have modern vehicles, then providing parking places for these vehicles within an acceptable distance must be considered, in addition to providing shaded pedestrian paths or using internal means of transportation that do not pollute the surrounding environment, such as bicycles, electric cars, etc. [16].

Infrastructure providing high-quality and appropriate technical methods should be provided in a way that does not conflict with the fact that it is located in an environment that represents a distinctive urban character. The historical area must also be supplied with all utilities and services that have become necessities of modern life. It is also necessary to supervise some necessary public activities and facilities that may be a source of disturbance to the privacy and distinction of such historical areas, such as public restaurants and cafes, which must be placed under surveillance and supervision by the relevant authorities [18].

Perhaps one of the most fundamental problems facing the rehabilitation process is how to create new functions and roles for historical buildings. The development planner must be aware of the extent of the problems and shortcomings that the building or historical center suffers from, and the architect must also know the areas within the scope of the historic area in which historical buildings can be repurposed. Through the integration of these efforts between architects, planners, administrators, and other members of the team, these historical centers can be saved from a state of neglect and decay and transformed into a state in which they can effectively serve their historical and cultural role as pieces of invaluable heritage and cultural wealth [16].

2.4. Strategies and Policies for Preserving Historic Areas and Buildings

The process of preserving the urban and architectural heritage of valuable historical, archaeological, and heritage buildings and areas is carried out by following many strategies and policies. The most important of these methods are listed below [19,20]:

- -

- Restoration.

- -

- Protection.

- -

- Preservation.

- -

- Conservation.

- -

- Adaptation–Reuse.

- -

- Clearance.

- -

- Replacement.

- -

- Renewal.

- -

- Developing.

- -

- Upgrading.

The method used depends on the individual circumstances and conditions of each area or building [15,19].

2.5. International Conventions Related to the Preservation of Historical Areas and Buildings

Many agreements have been sponsored by UNESCO for the maintenance and preservation of historical areas and buildings following the adoption of the Venice Charter [21] in 1964, which was issued in thirteen documents, the most important and famous of which was the first document, known as “International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites” [21]. This document is considered the first international charter upon which most international conventions were based on, and it is considered one of the most important documents related to the preservation of archaeological and historical areas and buildings, as it has become the main reference for restoration and maintenance operations.

This charter established important definitions used in this field [21]. The charter led to the issuance of the “Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage” in 1972, which approved a program aimed at classifying, naming, and preserving sites of special importance to mankind, namely the “World Heritage List” [22], as well as the “Nairobi Recommendations/Recommendation concerning the safeguarding and contemporary role of historic areas” in 1976 [23], which defined protection measures of historical areas into the categories of renewal, prevention, restoration, maintenance, and revitalization of historical or traditional areas and their environments; thus, protection includes all possible methods of intervention [23].

In addition, the 1979 “Burra Charter” was adopted for places of cultural importance in 2013 to be a guide for best practices in preserving and managing cultural heritage, as it emphasizes that preservation processes are required in sites of important cultural value and that, during the preservation process, caution must be taken to minimize change in archaeological buildings [24].

The “Washington Charter” was published for the preservation of historic cities and urban areas in 1987 [25] and indicated that new functions and activities in a historical area should be compatible with their historical nature [25]. There are many other relevant frameworks, charters, agreements, and recommendations related to the processes of preserving the urban and cultural heritage and protecting historical areas and other cultural properties of humankind [8].

3. Historic Jeddah (the Study Case)

3.1. Location and Historical Importance of Jeddah

Jeddah is considered one of the governorates of the “Mecca Region” and is located in the west of Saudi Arabia on the coast of the Red Sea. Its population was about 4,697,000 in 2021 [26]. Jeddah is considered the economic capital and the first tourist destination in Saudi Arabia and is the second largest city after the country’s capital. It is also considered a gateway to “Mecca”, which has unique value to all Muslims. It has the largest seaport on the Red Sea and is thus considered a financial and business center in Saudi Arabia and is a major port for exporting non-oil goods and importing local needs [26].

Jeddah has a long history [27] entwined with the emergence and spread of Islam. The historical transformation of Jeddah took place during the reign of Caliph Othman bin Affan in 647 when he that ordered the city be transformed into a port for sea pilgrims heading to perform the Hajj in Mecca [1]. To this day, Jeddah remains the main crossing for pilgrims and remains under the influence of successive Islamic disputes, starting with the Umayyads and including the Abbasids, Ayyubids, and then the Mamluks [1,27].

3.2. Historical Urbanization in Jeddah (Its Development and the Problems It Faces)

Jeddah has a distinctive historical architecture that differs in quality from the rest of the urban and architectural product present in various regions of Saudi Arabia. This is a result of the diversity of changes in its construction that the city witnessed during various eras and times. It was greatly influenced by Mamluk architecture and then the Ottoman architecture that prevailed in the Levant and Egypt at that time [1], and we can clearly distinguish the features of this distinct urbanism in the remaining historical part of the city, where the traces and evidence of urban products such as buildings, mosques, markets, and others are still witness to a different culture, distinguished by their use of local building materials that were commonly used at that time in building houses [8,26]; it is this cultural evidence which gave the historical part of Jeddah a distinction that earned it inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List [5].

For a long time, this distinctive historical heritage was neglected, especially with the modernization and development processes that the city has witnessed since the founding of the “Third Saudi State” in 1902 by King Abdulaziz Al Saud, who subjugated Jeddah to his kingdom in 1926; the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was later established in 1932 [28]. As a result of this modernization, the historical parts of the city were neglected, and the historic city wall and many of its gates were demolished in 1947 with the aim of expanding and modernizing the city without taking into account the distinctive historical heritage that the city possesses. The last quarter of the twentieth century, however, witnessed a rise in interest in the historical part of the city, and attempts were made to develop it in order to preserve it from neglect and extinction [8].

3.2.1. The Historic City Wall of Jeddah and Its Old Gates

During the Mamluk era (1250–1517), Sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghuri, the last Mamluk sultan in Egypt, built the Jeddah Wall in 1509 to protect it from Portuguese raids [1,2]. The wall includes seven gates: Bab Mecca, Bab Al-Madina, Bab Sharif, Bab Al-Nafi’a, Bab Al-Mughrabi, Bab Al-Sabbah, and Bab Sarif. These gates were built in stages according to necessity. Because of the narrowness of the city gate, an eighth double gate with sufficient width to allow cars to pass through it easily was added on the northern side of the wall at the beginning of the Saudi era, known as Bab Jadid. The entire wall was demolished in 1947 [2] due to the increasing urban expansion of the city [29] (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

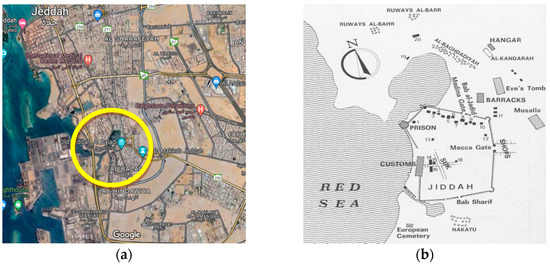

Figure 1.

(a) A current map of Jeddah after the huge expansions it witnessed during last eighty years, showing the size of the historical part of the city, which was located within its old wall before its demolition in 1947 [30]. (b) Map of Jeddah as drawn by the Italian orientalist Carlo Alfonso Nallino in 1938. It shows the historic city wall [31].

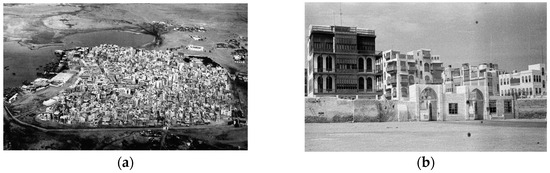

Figure 2.

(a) Jeddah as shown in an aerial photograph taken in 1938, where its urban mass appears inside the historic city wall, which represents the historical area of the current city [32]. (b) “Bab Jadid”—New Gate—which was built at the end of the 1930s. It is considered the last gate built on the wall before its demolition and was a double gate that could accommodate cars [33].

3.2.2. Jeddah’s Historic Districts (Harrat) and Buildings

Historic Jeddah is divided into four main districts; these districts are called “Harah”. In the north is “Haret Al-Sham” and in the south is “Haret Al-Yemen”, “Haret Al-Bahar”, and “Haret Al- Al-Mazloum”. These districts, called “Harrat”, contain many distinctive historical houses and buildings that are considered valuable pieces of human heritage, where construction methods and building materials were used depending on the materials available in the local environment [29,34].

The most famous and oldest buildings existing to date are the houses of “Al-Baeshen”, “Al Sheikh”, and “Al-Shafi’i Mosque”, which are located in “Haret Al-Mazloum”, as well as the houses of “Al-Banaja”, “Al-Zahid”, and “Al-Pasha Mosque” in “Haret Al-Sham”; the houses of “Al-Nassif” and “Nour Wali” in “Haret Al-Yaman”; and the houses of “Al-Sharbatli” and “Al-Nimr” in “Haret Al-Bahr”, among others [34] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) House of “Al-Baeshen”. It was built in 1857 and is considered an example of a historical house whose owners are still keen on maintaining and caring for it [35]. (b) House of “Al-Nassif”, which was built in 1872 and is considered one of the area’s most important heritage landmarks, gaining historical importance since King Abdulaziz resided there in 1925; it has now been transformed into a museum for Jeddah [36].

3.3. Problems of Urban Deterioration in Historic Jeddah

With the rapid development that Jeddah witnessed at the beginning of the second half of the twentieth century, there was rapid growth in the urban population, which is considered one of the most important causes of urban deterioration in the area. As the social composition of historic Jeddah changed, its people moved to live in new, more modern districts, renting the buildings they owned in the historical area to expatriate workers of different nationalities, which led to the deterioration of the area due to the absence of the necessary maintenance and severe neglect from the migrant workers who occupied these historic buildings. Such neglect exposed the historic area more than once to the danger of fire as a result of high electrical loads, lack of safety measures, etc. [4] (Figure 4a).

In addition, natural factors such as a high level of humidity also contributed to urban deterioration. This led to the erosion of wood and damage to the facades, as well as a rise in the groundwater level, which damaged the foundations of the buildings and led to corrosion and cracking and the walls being saturated with moisture. Incorrect restoration operations that did not respect the character of the buildings also led to changing the heritage features of many of these buildings [37,38] (Figure 4b).

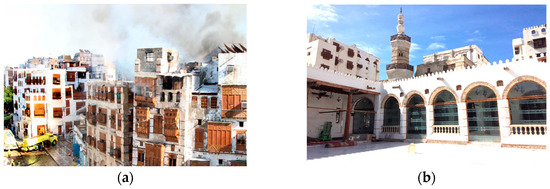

Figure 4.

(a) Historic Jeddah suffered from fires for long periods as a result of the neglect of the area and the poor condition of its infrastructure [39]. (b) An example of the incorrect restoration of the historic Al-Shafi’i Mosque in 2015, which did not respect the original building materials and turned it into what resembles a white plastic block from the outside, with glass doors used on the inside on the courtyard due to air-conditioning and other additions not related to the original building being added to the mosque [40].

4. Strategies and Policies for Urban Preservation of Historic Jeddah

4.1. The Beginnings of Interest in the Urban and Architectural Heritage of Historic Jeddah

Interest in the historic Jeddah area began with the establishment of “the old Jeddah municipality” in 1977. Many steps have been taken that aim to preserve the urban and architectural heritage of the old city of Jeddah, including the following [9]:

- -

- Preparing the first detailed master plan to preserve and develop historic Jeddah and classify its heritage buildings and its historical urban fabric by the British consultant Robert Matthew during the period from 1978 to 1983 [37].

- -

- Establishing “the historic Jeddah protection department” in 1993 with the aim of protecting heritage buildings from demolition [9].

- -

- Establishing the “Prince Majid bin Abdelaziz’s project to take care of historic Jeddah”, which included the restoration of “Nassif house” and turning it into a museum, revealing parts of old city walls, as well as partial restoration of 12 heritage buildings [9,38].

- -

- Forming a “Higher committee for fire extinguishing project”, where the first phase of the fire extinguishing network was implemented in 2011 and which is now completed [8].

- -

- Beginning the implementation of the “King Abdulaziz project for the preservation of historic Jeddah”, starting in 2005, adopting policies for dealing with heritage buildings and establishing “the urban development department in historic Jeddah” [8,9].

4.2. Efforts of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage to Develop Historic Jeddah

The Saudi commission for tourism and national heritage” was established in 2000 [8] and was transformed into the “Ministry of tourism” in 2020. The commission developed the “historic Jeddah development project”, through which it worked in cooperation with the Jeddah municipality to preserve, rehabilitate, and develop its historical sites architecturally, culturally, and economically in a way that highlights its distinctive features and urban heritage. In addition, the commission encouraged the owners of that urban heritage to protect, maintain, and repurpose their properties in a manner commensurate with their historical and cultural value [38].

The authority has also played a role in the restoration of many heritage buildings and others and, in cooperation with the Jeddah municipality, has worked to set a specific timetable for the completion of many projects in historic Jeddah. These efforts have the aim of highlighting the area’s historical and heritage importance and value. Among these efforts, the authority has implemented many tasks, including the following [9]:

- -

- Contracting international consultants to prepare a protection and management plan for the area, within the framework of completing its file for registration on the World Heritage List, which was achieved in 2014.

- -

- Collaborating with the Jeddah municipality in determining a priority plan for the projects required to develop the area, and coordinating on the status of the area and the studies needing to be implemented. Among the most important of these projects is the project to revive tourist axes and paths in historic Jeddah [41]. The most important of these historical and tourist paths and axes are the “Al-Nada axis”, “Alawi axis”, and “Abu Anaba Axis”, on which pedestrians can cross the area in a walking time of fifteen minutes. This last axis is considered a distinguished tourist route; in addition to the distinguished historical buildings it contains, it is flanked on both sides by many outlets displaying the crafts and handicrafts of productive families and many stores that serve popular foods [29,41] (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The project to revive tourist axes and paths in historic Jeddah. (a) Path: “Abu Anaba axis,” on which many historical buildings are located. It has important historical and heritage houses, and pedestrians can cover it in a walking time of fifteen minutes [41]. (b) Path: “Al-Nada axis,” which represents the market in the old city of Jeddah [41].

Figure 5. The project to revive tourist axes and paths in historic Jeddah. (a) Path: “Abu Anaba axis,” on which many historical buildings are located. It has important historical and heritage houses, and pedestrians can cover it in a walking time of fifteen minutes [41]. (b) Path: “Al-Nada axis,” which represents the market in the old city of Jeddah [41].

4.3. Strategies for Preserving the Historic Jeddah

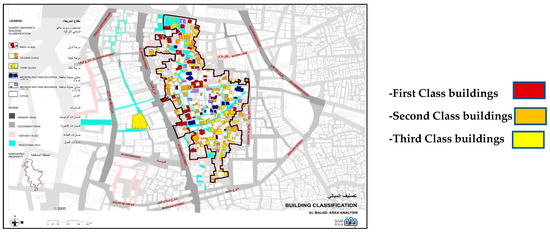

The British consultant Robert Matthew is considered the first to develop a masterplan to preserve the historical area from 1978 to 1983. In his plan, he identified more than a thousand valuable historical buildings, which were classified into three levels, historical, artistic, and spatial, based on several criteria related to the uniqueness of the building’s architectural style and its value, in accordance with adopted standards in the UNESCO classification, as described below [37,42] and illustrated in Figure 6:

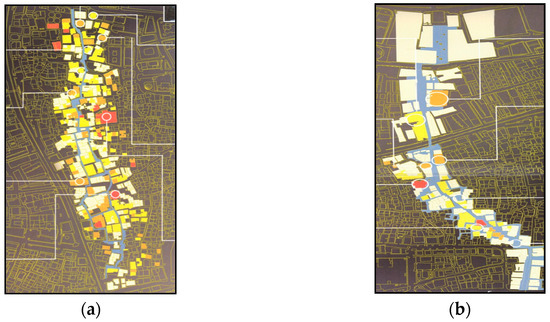

Figure 6.

Matthew’s classification for the historical buildings in historic Jeddah according to the uniqueness of the building’s architectural style and its value. The classes are historical, artistic, and spatial, in accordance with adopted standards in the UNESCO classification [42].

- -

- First Class: buildings of national importance;

- -

- Second Class: buildings of regional importance;

- -

- Third Class: buildings of local importance.

In addition, Matthew’s classification also includes modern high-rise buildings that were constructed in recent periods, as well as vacant lands, paths, corridors, etc.

Matthew’s plan also proposed adopting a “sustainable preservation” strategy [2] by re-using the historical buildings according to their degree of classification, as elaborated below:

- -

- First-level buildings: buildings being used institutionally, whether as governmental, administrative, cultural, or educational buildings [42];

- -

- Second- and third-level buildings: buildings being used for hospitality, residential, office, or commercial activities [42] within a specific zone of the historic area called the “Nominated Property” [42,43] (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of heritage buildings in historic Jeddah and proposals for their reuse *.

Table 1. Classification of heritage buildings in historic Jeddah and proposals for their reuse *.

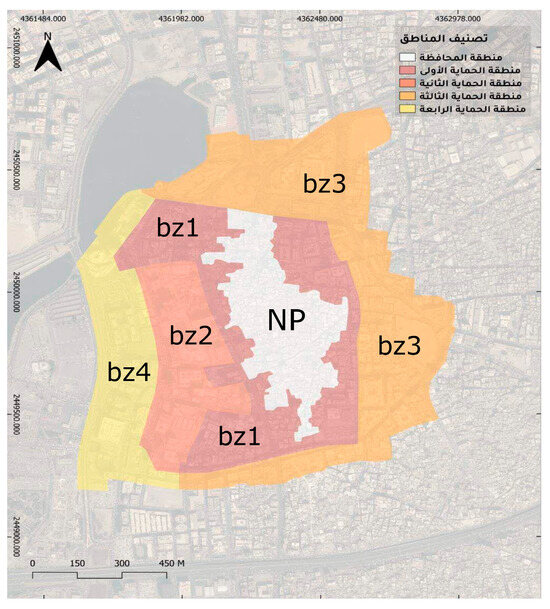

The “Nominated Property” is the protection area that was registered in 2014 on the UNESCO World Heritage List [5], and it includes more than about 250 classified historical and heritage buildings. It also covers an area of 18 hectares. It is located within another circle called the “Buffer Zones”, which are a group of urban areas that surround the “Nominated Property” on all sides and cover an area of 113.53 hectares over the remaining parts of the historic area and other surrounding areas [43].

The Buffer Zones are divided into four conservation areas with the aim of playing an important role in preserving the “Nominated Property” heritage conservation area and enabling it to continue to flourish in light of the changes and developments taking place in the city as a whole. The “Historic Jeddah building requirements system” is followed in this area, which comprises building regulations established by the Jeddah municipality [29,42] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The historic Jeddah protection area “Nominated Property” (NP)—shaded in white—which is the area that was registered in 2014 on the UNESCO World Heritage List, followed by the four “Buffer Zones” (bz1–bz4), which are a group of conservation areas surrounding the historic Jeddah protection area from all sides [43].

With time and the acceleration of the modernization movement, in addition to the various factors leading to deterioration in the historical area, many historical and heritage buildings have been lost. There are now only about 600 buildings remaining out of the approximately 1000 buildings inventoried by Robert Matthew in the 1980s distributed between the protection and conservation areas [4].

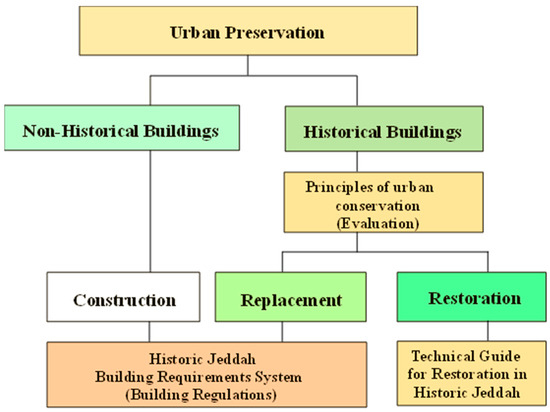

This means that the area has lost about 40% of its buildings in less than 40 years. Therefore, the “Jeddah municipality” has set a system of building regulations—the “Historic Jeddah building requirements system”—to demonstrate strategies for urban preservation in the historic area through three main paths, as follows [4]:

- -

- Restoration of historical and heritage buildings;

- -

- Replacement (by rebuilding) of heritage buildings that already exist but cannot be restored due to their poor structural and urban conditions;

- -

- Constructing new buildings on vacant lands or replacing modern buildings that have no value and distort the urban and visual landscape of the area.

However, it is absolutely forbidden to demolish any historical building, as all buildings located within the “Nominated Property” area are subject to a protection policy that prevents removal, change, modification, addition, or other work [42,43] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The strategies for urban preservation in historic Jeddah [43].

With the continuing state of urban deterioration in the historic area and the increase in the number of buildings on the verge of collapse, there was a need to adopt a number of clear and specific strategies to deal with historical and heritage buildings depending on the condition of each building individually. The Jeddah municipality classified historical and heritage buildings based on their structural and urban conditions, based on what was stated in Robert Matthew’s classification of heritage buildings [43].

Buildings were thus classified into categories A, B, and C, in which the buildings are classified as having either minor damage (A), stable damage (B), or unstable damage(C).

Historical buildings represent 82% of the total building stock in the historical area, 9% of which are category (A) buildings, 54% are category (B) buildings, and 19% are category (C) buildings. These types of buildings require the use of a “Restoration” strategy, in order to prepare them for another strategy, such as the “Adaptation/Reuse” strategy, according to the relevant proposal in Robert Matthew’s proposal of reusing heritage buildings, as reviewed and approved by the Jeddah municipality [4,43].

The rest of the buildings in the area are classified into categories D or E due to their poor structural and urban conditions, classified as having major damage in which there is no point in restoration, including cases of partial or complete collapse. These buildings represent 14% of the total building stock in the historical area. These types of buildings require the use of a “Replacement” strategy and rebuilding, after which they can be used to meet many purposes compatible with the nature of the historical area [4,43].

As for vacant lands, they are classified as category (F), and their percentage does not exceed 4% of the area’s size. These lands are used for the purposes of new construction that is compatible with the historical area and supports it in accordance with the established architectural rules and urban requirements (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Classification of heritage buildings in historic Jeddah according to their structural and urban conditions and the preservation strategies followed [The Researchers].

In general, historical and heritage buildings are subject to an evaluation process carried out by a specialized committee of experts in the fields of architectural and structural preservation before proceeding to determining the most appropriate strategy and then setting the policy for preservation. The evaluation process includes several criteria considering the urban and structural conditions of the building, in addition to an assessment of the surrounding buildings and a study of the soil, foundations, walls, etc., bearing the building’s weight [37,42,43].

From our analysis of the strategies and policies adopted for the urban preservation of the historic Jeddah area, we find that they were represented by several main strategies, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strategies that were adopted for the urban preservation of the historic Jeddah *.

5. The Challenges Facing the Process of Preserving Historic Jeddah while Implementing Modern Development Decisions for the City (2021 until Now)

With the change in political leadership in Saudi Arabia in 2015, a new king of Saudi Arabia assumed power. The King chose, for the first time in the history of Saudi Arabia, a young crown prince in his thirties. The new crown prince was assigned to head the Council of Ministers, as Saudi Arabia was witnessing a radical change represented by openness to the contemporary world. For the first time, several decisions were made that may seem simple to most people in the world, but for Saudi Arabia, they amounted to lifting prohibitions, such as allowing women to drive cars, establishing cinemas, organizing film and theater festivals, and organizing concerts, attracting famous artists to visit Saudi Arabia and present their art there. In addition, sports of all kinds for both genders were promoted, and regional and international sports competitions were organized. These changes encouraged tourism, expanded archaeological excavations, established tourist resorts, etc. Mixing between men and women in restaurants and cafes, which was previously prohibited, was also allowed, among many other changes, in an attempt to change the face of Saudi society, which was accomplished in just a few years.

5.1. Saudi’s 2030 Vision

In the same context, a massive development program was launched in 2016 that includes developing all aspects of economic, social, and cultural life under the name “Saudi’s 2030 vision” [6]. This vision aims primarily to reduce dependence on oil resources and rely on the resources of all industrial, including tourism and other sectors of society. It also includes several development programs. This vision has received support from various groups of the Saudi population, especially the intellectual classes and the youth, and it is an approach that this study and those in charge of it see as worthy of support and encouragement [6].

5.2. Jeddah’s Development Projects and Their Effects on the Historic Jeddah Area

As a result of the development pursued by Saudi Arabia, represented by the issuance of “Saudi’s 2030 vision”, the nation’s political leadership adopted an ambitious program to modernize Jeddah as a tourist destination for the country and establish it as its second capital [44,45]. This includes removing and clearing many slum areas and the existing unplanned districts of the city and replacing them with new districts designed according to the latest global systems aimed at the well-being of citizens. This included the removal of some unplanned districts adjacent to the historical area in Jeddah, the case study area, starting in October 2021 [46].

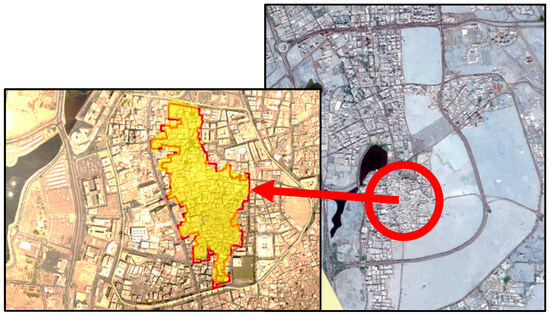

Other sovereign decisions were also issued to expropriate the historical area, including the protection and conservation area, starting March 2022; a final masterplan for developing the area has not been announced to date, other than announcing that the removal of districts aimed to create surrounding areas to support the role of the historical area, and the expropriation of the historical area will contribute greatly to an easier and less re-strictive urban control and development process in the area [46,47] (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Removal and clearance of slum areas around the historical area and expropriation area within the scope of the historical area according to the recent development decisions in Jeddah made in 2021 and 2022, respectively [44].

It is expected that these modern development decisions for the city, which have begun to be implemented, will help confront the challenges facing the urban preservation process of historic Jeddah. Such challenges can be summed up by the need for more investment and funding to complete the preservation and restoration of the urban heritage of the area and then rehabilitate and repurpose it for the various proposed activities mentioned above. This is the actual purpose of those recent development decisions: they provided the necessary support for the expropriation of the area which will then allow for investment through a plan currently being prepared. Increased investment will contribute to creating an autonomous economy for the area that will enable it to continue to prosper as a historical tourist destination with diversified activities. In addition, starting the preservation and restoration work of such expansion, which is supervised by the highest sovereign authorities in Saudi Arabia, will create an opportunity for local cadres to train in conservation and restoration work, which is what the area in particular and Saudi Arabia in general needs [47,48].

The expropriation of the historical area will also contribute to confronting another of the most important challenges facing the area, which is represented by the existing imbalance in its demographic composition after its original people abandoned it and foreign expatriate workers moved in, which posed a threat to the area due their lack of belonging to it or association with its identity.

Other problems resulting from this demographic shift included the workers’ misuse of the existing buildings by crowding in them (as a result of their low-level income), which resulted in many other dangers that the area suffered from for long periods, such as the outbreak of fires and a lack of attention being paid to periodic maintenance operations, ultimately causing the area to lose many of its historical and heritage buildings [46,47].

Furthermore, the removal and clearance of entire districts and huge areas surrounding the historic area has given the relevant administrative authorities a golden opportunity to replace them with new, more contemporary districts and activities that support the historical area culturally, artistically, touristically, economically, etc., and that contribute to its continuation and prosperity. This will be observed in the coming period once all master and detailed plans for that area are approved and their implementations begin [46] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

In the map to the left, the protection area (NP) within the scope of historic Jeddah as it appears before the demolition work. In the map to the right, historic Jeddah within the scope of the demolition of entire districts and huge areas that took place, which will give the relevant administrative authorities an opportunity to replace them with new and contemporary districts featuring activities that support the historical area and contribute to its continuity and prosperity [44].

6. Discussion

After reviewing urban preservation plans, programs, and strategies for the historic Jeddah area as a case study for historical areas within existing cities, this study concludes with the following results:

- Historic Jeddah has a distinctive urban and architectural heritage, which qualified it to be registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2014.

- Interest in the urban and architectural heritage that Jeddah possesses did not begin until the last quarter of the twentieth century, and the historical area lost many of its historical components before that time, such as its historical walls, which were demolished in 1947. This long-term neglect also caused various forms of urban deterioration.

- Despite the great interest in historic Jeddah, especially at the beginning of the current century, the successful attempt to register it on the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the attention it has received through “Saudi’s 2030 vision”, the area is still suffering from urban deterioration as a result of the entire period of neglect and the ac-cumulation of its causes, in addition to the large size of the historical area, both in terms of its area and in terms of the number of buildings within it which need restoration and ongoing maintenance.

- Through the presentation and review of the various plans and strategies that have been developed and implemented, it can be noted that the urban preservation strategies in the historical area in Jeddah have been based on two main trends:

- -

- The first trend is dealing with the historical area itself and its urban fabric, where “developing” and “upgrading” strategies are followed through implementing some projects and following many procedures in the area, such as organizing vehicle traffic, allocating paths for pedestrians, establishing the fire-fighting network, and so on.

- -

- The second trend is dealing with historical and heritage buildings by following one of three strategies according to each individual case. Strategies are deter-mined based on a special classification of buildings that was adopted from three basic classification levels that represent the feasibility, or lack thereof, of preservation and restoration operations. These strategies include implementing strategies of “restoration” for the first level of buildings, “replacement” for the second level of buildings, and the last strategy is for “new construction” for vacant lands or to employ a strategy of “clearance & renewal” for lands recently cleared of modern buildings that pollute or distort the urban visual image.

Moreover, the “Adaptation/Reuse” strategy is followed for historical and heritage buildings that are being restored, in accordance with Robert Matthew’s proposal and classification in this regard.

- E.

- Although the Jeddah municipality has adopted a number of strategies to deal with historical and heritage buildings depending on the conditions of each building in-dividually, the number of restored buildings is considered very small, as the study observed that 82% of the total buildings in the “Nominated Property” (NP) need preservation and restoration operations. This may be due to the lack of funding necessary for such major work, which requires huge open budgets; the recent era of local cadres’ involvement in preservation and restoration work; as well as the scarcity of specialists, which always requires the use of foreign expertise, thus increasing time, effort, and costs.

- F.

- As a result of “Saudi’s 2030 vision”, the political leadership adopted a development program that includes removing many of the existing districts of Jeddah. This included the removal of some districts adjacent to historic Jeddah, and other sovereign decisions were also issued, such as expropriating the historical area of Jeddah, without announcing a final master plan to develop the area, aside from declaring that these removals aim to create surrounding areas that work to support the role of the historical area and that expropriation of the historical area will make the urban control and development process of the area easier and less restrictive. Perhaps as a result of this decision, we can expect that this will contribute to advancing the conservation process by providing all the financial, human, technical, and logistical capabilities necessary to implement the conservation plans and strategies being followed in the area.

7. Conclusions

This study dealt with plans, programs, and strategies for the urban preservation of the historic Jeddah area as a case study of historical areas within existing cities in the Middle East. In addition, the study covered the challenges that face the authorities responsible for urban preservation operations and which led to the recent development decisions to remove many districts around the area and to the complete expropriation of historic Jeddah. Therefore, the study concludes that, in order for the protection of historic Jeddah to be more effective, a masterplan must be put in place for the development of the area and the surrounding cleared areas that adopts integrated development, economic, urban, and social policies that take into account the preservation of what expresses the city’s local character and identity, especially the urban fabric, the relationships between the buildings and the surrounding environment, and the construction methods and materials used.

This, of course, does not mean not constructing modern, contemporary buildings, but rather constructing them in a way that benefits the area functionally and visually.

In addition, the remaining original dwellers of the area should be involved in making decisions related to the preservation, development, or rehabilitation of the historical area.

All of this should also be presented to the public for discussion, especially since a state of satisfaction prevails among all Saudis as a result of the issuance of “Saudi’s 2030 vision” and the resulting tangible openness in Saudi society. This opening trend includes all aspects of life, from interest in culture and arts to the formation of a “Ministry of Culture” for the first time in the history of Saudi Arabia and the establishment of an arts authority that includes the fine and musical arts and others. Therefore, this state of openness must be exploited to advance this praiseworthy trend by starting to consult public opinion when making decisions, especially when such decisions are related to their lives, heritage, and cities.

Based on the previous findings of the study, the authors make the following recommendations:

- -

- First—general recommendations:

- Attention should be paid to the rules and principles of shaping the urban and architectural fabric of historic Jeddah when following development policies, so that the area does not lose its continuity and maintains its population structure, with its unique social and economic characteristics.

- Participation of the original dwellers is recommended in concerted efforts to confront existing challenges through popular, non-governmental institutions that enjoy official and public support.

- Integrated studies of the value of the architectural and urban formation in the historical area should be conducted. The value of these historical formations should be documented and linked to the social values and principles that are rooted in the social fabric of the community of that area before starting on development processes that aim to preserve and consolidate historical formations, so that the science of preservation does not turn into a mere financial investment only.

- -

- Second—recommendations on the scope of the urban content of historic Jeddah:

- The division of the historic Jeddah area into several administrative areas should be studied in order to facilitate dealing with the urban contents therein within the framework of a comprehensive plan for the entire historical area, as one of the current challenges is how to deal with the enormity of the area as a whole.

- A set of controls, requirements, guidelines, and technical standards should be established that would achieve the strategies of the development plan, ensuring that a balance is achieved between the general directions of development and individual desires for improvement and investment (facilitating communication and integration between investors, institutions, and public bodies), with the aim of preserving the historical, urban, and architectural heritage of historic Jeddah.

- The process of restoring and reusing buildings, rehabilitating the area as a whole, rebuilding its dilapidated buildings with appropriate shaping of their original urban structure, and reviving the original urban character of the area as well as original activities or those compatible with the area’s buildings should be accelerated through adherence to sustainable urban development standards.

- The strategy of demolishing some modern buildings built in later periods should be stopped, and instead their appropriate reuse within the historic area should be studied. The history of a city must also be read through the passage of time and the scars that time leaves behind, so that the historic center is not reshaped in a new and false way.

- The remaining original dwellers of the historical area should be encouraged to remain in the area by improving and restoring their residences while learning about their needs and providing them with various services, facilities, etc. They should al-so be given priority over any other projects, with the aim of maintaining their function in a large part of the historical houses in the area, which gives the historical area sustainability and opportunity for continuous development.

- Infrastructure rehabilitation operations should be continued as a basis for development operations to ensure the possibility of the area’s continued development according to the requirements of modernity and without prejudice to historical value within the framework of improving the urban environment.

- Providing a strategic plan for the ongoing periodic maintenance of restored, repurposed, or reconstructed buildings within the framework of the sustainable development of the region is necessary.

- A comprehensive plan must be developed to protect the historical area by establishing scenarios for how to deal with disasters, sources of pollution, potential dangers, and other threats.

- -

- Third—recommendations on the scope of the removed areas (the areas surrounding historic Jeddah):

- The current removed areas surrounding historic Jeddah must have an explicit primary mission to serve as an additional buffer zone to the historical area in Jeddah, and this option should be absolutely preferred over others when setting out to define uses for these areas and the choice of projects with them.

- A clear strategy must be developed and the necessary legislation must be enacted to regulate the reconstruction and urbanization process in the areas surrounding historic Jeddah that have been removed, so that the architectural character of the area, its fabric, and its urban formation are preserved and integrated through all possible means. In addition, the definition of new uses must be compatible with the needs of the historical area.

- Modern urbanism can achieve contemporaneity with local belonging by meeting the requirements of modern life, provided that the urban cultural dimension of Jeddah’s historical heritage is preserved. This can be achieved by drawing inspiration from the spirit, philosophy, characteristics, and features of local architecture and by carrying out building and construction process using the latest contemporary materials and methods.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: conceptualization, M.A., E.M. and K.M.H.; methodology, M.A.; software, E.M.; validation, I.E., M.G. and E.M.; formal analysis, K.M.H.; investigation, I.E.; resources, M.A.; data curation, E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.H.; writing—review and editing, I.E. and M.G.; visualization, E.M.; supervision, K.M.H.; project administration, M.A. and M.H.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-RG23116).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spahic, O. Historic Jeddah as a Unique Islamic City. IIUM J. Relig. Civilizational Stud. 2021, 4, 60–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tawab, A.; El-Din Ahmed, A.G.; Al-Darwish, A.I.; Al-Mutahar, H.A.A.-Y. Achieving the Sustainable Preservation of Historical Urban Commercial Spaces–Case Study–Historic Jeddah. Eng. Res. J. 2021, 5, 239–240. Available online: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/erjeng/vol5/iss4/1 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Badawy, S.; Shehata, A.M. Sustainable Urban Heritage Conservation Strategies—Case study of Historic Jeddah Districts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cities’ Identity through Architecture and Arts (CITAA 2017), Cairo, Egypt, 11–13 May 2017; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018; pp. 83–97. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.1201/9781315166551-8/sustainable-urban-heritage-conservation-strategies%E2%80%94case-study-historic-jeddah-districts-samaa-badawy-ahmed-shehata (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Walid, S.; Nada, S. Policies for conservation of the urban heritage in historical centers historic Jeddah Case study. J. Gulf Arab. Penins. Stud. 2020, 185, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah. Date of Inscription: 2014. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1361/ (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia “Saudi Vision 2030”. 2016. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/cofh1nmf/vision-2030-overview.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Document-57-19, WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE, Paris, 2019. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/compendium/154 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Khaled Mahmoud, H. Development and Employment of Archaeological Areas in Historic Cities: Examples of Historic Arab Cities; Noor Publishing House: Rodgau, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jeddah Municipality; General Authority for Tourism and Antiquities. Historic Jeddah: A Journey of the Past, Present and Future; General Authority for Tourism and Antiquities: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; The World Heritage Committee. Decisions Adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 35th Session, Paris, UNESCO Headquarters 19–29 June 2011; p. 199. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2011/whc11-35com-20e.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Rawiya, H. Developing Urban Spaces as an Entry Point to Preserving Historical Areas. In Proceedings of the Al-Azhar 7th International Engineering Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 7–10 April 2003; Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University: Cairo, Egypt, 2000; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- John, R. The Lamp of Memory; Nabu Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Sattar, I. Methods and Strategies for Heritage Conservation; Research and Training Center for Monuments Conservation, City and Regional Planning Department, University of Engineering and Technology: Lahore, Pakistan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Islam Hamdi, E.-G. The impact of implementing projects to preserve historical areas in improving the city’s urban fabric, a case study: Developing the historical area in the city of Muharraq in the Kingdom of Bahrain. In Proceedings of the First National Architectural Heritage Forum; Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 11–17 November 2011; pp. 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Heba, K. Preserving architectural heritage in historical cities: Study of the architectural heritage with the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century in Alexandria, Egypt. In Proceedings of the Structural Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XI, (STREMAH 2011), Chianciano Terme, Italy, 4–7 September 2011; Volume 118, pp. 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled Mahmoud, H.; Islam Hamdi, E.-G. Introduction to the Preservation and Development of Historical and Heritage Areas and Buildings; Scientific Publishing and Translation, Qassim University Qassim: Buraydah, Saudi Arabia, 2018; pp. 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Baqi, I. Rooting Cultural Values in Building the Contemporary Islamic City; Center for Planning and Architectural Studies: Cairo, Egypt, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dalia, A.-D.; Islam Hamdi, A.-G. Historic and Heritage Areas: Preservation and Development, an Introduction to Improving the City; Foundation for Cultural Development: Alexandria, Egypt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, R. Conservation in the Built Environment; Addison Wesley Longman Ltd.: Chelmsford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. (THE VENICE CHARTER 1964), Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/venice_e.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. The General Conference of UNESCO Adopted on 16 November 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. UNESCO. General Conference, 19th, Nairobi, Kenya. 1976. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000114038.page=136 (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- The Australia ICOMOS. Burra Charter 1979. Adopted by in 2013. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/burra-charter-practice-notes/ (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. (WASHINGTON CHARTER 1987), Adopted by ICOMOS General Assembly in Washington, DC, October 1987. 1987. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeddah (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Ibn al-Mujawar, A.; Jamal al-Din, A.-Y.; Mamdouh Hassan, M. The Description of the Countries of Yemen, Mecca, and Some of the Hijaz, Called the History of the Clairvoyant, 1st ed.; Library of Religious Culture: Cairo, Egypt, 1996; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emirate_of_Nejd_and_Hasa (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Khaled Mahmoud, H. Saudi National Heritage and UNESCO World Heritage List through the Saudi Vision (2030); The General Authority for Tourism and National Heritage: Qassim, Saudi Arabia, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@21.4992151,39.1820272,9331m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en&entry=ttu (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Available online: https://lostopportunitiesandwastedtimes.blogspot.com/2013/07/blog-post_28.html (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeddah#/media/File:Jeddah-1938.jpeg (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Available online: https://www.wafyapp.com/en/article/jeddahs-ancient-gate-bab-makkah (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Abdullah bin Zahir, A.-T. Architecture in the City of Jeddah in the Ottoman Era 923-1334 H/1517-1916 AD. Master’s Thesis, King Abdulaziz University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://al-turath.com/arabic/study-consolidation-and-restoration-of-jeddahs-high-risk-historic-buildings-umar-baeshen-house-historic-jeddah/?lang=en (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1702936/saudi-arabi (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Mathew, R. Study of the Historical District of Jeddah; Ministry of Municipalities and Rural Affairs: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 1980.

- Jeddah Municipality. Restoration Manual for Historical Buildings in Historical Jeddah. Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://al-turath.com/pdf/11.%20JEDDAH%20RESTORATION%20MANUAL.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/338618 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Available online: https://news.iium.edu.my/?p=137354 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Saudi Society for Urban Sciences and King Saud University. Historic Jeddah: A World Heritage Site; An Introductory Bulletin for Tourist Trails in the Historic City of Jeddah; Saudi Society for Urban Sciences: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alhojaly, R.A.; Alawad, A.A.; Ghabra, N.A. A Proposed Model of Assessing the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings in Historic Jeddah. Buildings 2022, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddah Municipality, Government Area. Historic Jeddah Building Requirements System, Jeddah Municipality, Saudi Arabia. 2014. Available online: https://www.jeddah.gov.sa/Business/LocalPlanning/HistoricalJeddah/pdf/Arabic/5.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) Institute of Earth and Space Sciences. Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://kacst.gov.sa/2022 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs. The Comprehensive Urban Vision for Jeddah Governorate. Future Saudi Cities, Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs & the United Nations Human Settlements Programme-UN-Habitat, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 2019. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/04/jeddah.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demolitions_in_Jeddah (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Ayman, I.; Mansour, H.; Amr, A.; Ibrahim, H. Exploring the Quality of Open Public Spaces in Historic Jeddah. ACE Archit. City Environ. 2023, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, S.K.; Hegazy, I.R. Investigating the Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Waterfront Development in Jeddah City. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2023, 18, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).