Micro-Process of Open Innovation in Megaprojects Under Sense-Making Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Open Innovation in Megaprojects

2.2. Sense Making in Innovation Change

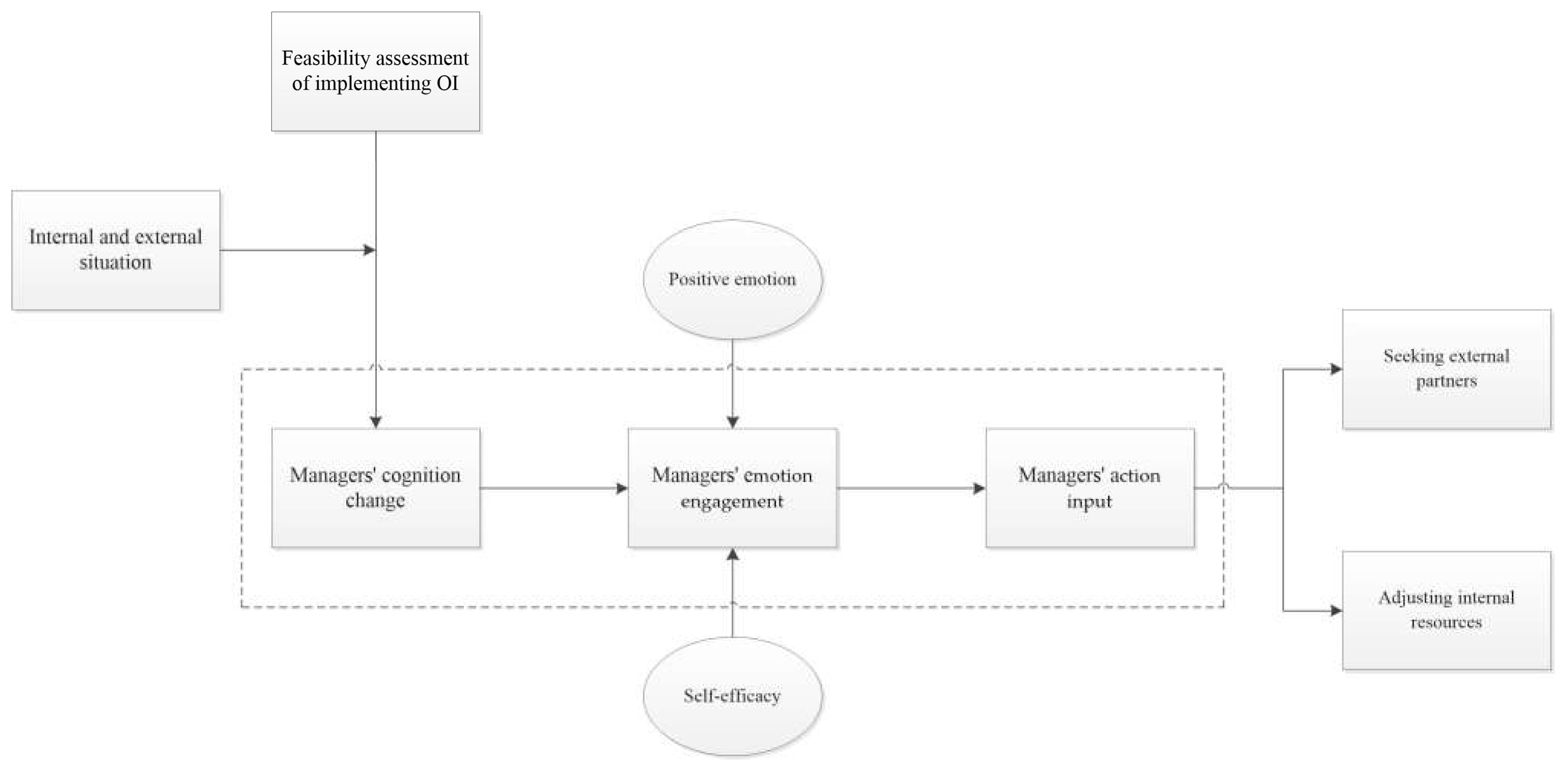

2.3. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Case Description

4.1. Case Project

- Bridge facilities include 2 extra-large bridges, 4 large bridges, 22 medium bridges, and 3 small bridges to span important rivers, lakes, or other obstacles, as well as to meet the passage needs of different sections. In addition, there are 88 culverts used for drainage or the passage of small traffic.

- There are 14 interchanges overpasses and 16 separation overpasses. These overpasses are mainly used to separate different directions or different types of traffic flows to improve driving safety.

- This project also has complete facilities, including 51 footbridges, 56 passageways, 2 management offices, 2 maintenance work areas, 3 service areas, 2 parking areas, and 8 toll stations.

4.2. Open Innovation in Case Project

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Sense Making in the Open Innovation Formulation Stage

“The new round of technological revolution promotes the green, low-carbon and high-quality development of construction industry, which greatly changes the industry environment. Faced with severe industry competition, this project should change innovative thinking and behavior mode to enhance sustainable development”.[Manager #1]

“I was aware of the task conflict and role tension brought about by open innovation. At first, I even had the idea of “retreating”, but I changed cognition and redefined work goals after meaning assessment. I have the ability to coordinate and arrange my own work, repositioning myself”.[Manager #5]

“Negative emotions are likely to be involved in sense-making, as an open and distributed form of innovation process are assumed to call for more administration and inter-organizational engagement, which adds an extra burden to the already stressful work environment. Nonetheless, it is not a bad choice for this project to access external innovation resources through the open innovation model. From a long-term perspective, it is seen as a safeguard, particularly at times when there is a mismatch between internal innovation resources and demand. Moreover, open innovation as a planned change, which is considered safe, novel, and even challenging, tends to aroused more interest”.[Manager #3]

“CCCC has a good innovation culture, which provides institutional guarantee for our project to carry out open innovation. Support from CCCC senior management attempts to open up innovation and offer to help in any way they can. In addition, the company put in place appropriate mechanisms to protect intellectual property”.[Manager #1]

“We look for reliable partners who know each other well, have complementary skills, have extensive experience, and can communicate openly. We recruit partners primarily from organizations or individuals who have worked with us before, and also open up new channels of innovation”.[Manager #2]

“These incentives include bonuses, promotion opportunities, etc. Additionally, performance standards are also a form of support policy used to evaluate and measure employees’ performance in open innovation. For example, active utilization of external knowledge sources by employees and contributions to internal knowledge output could be one of the evaluation indicators”.[Manager #2]

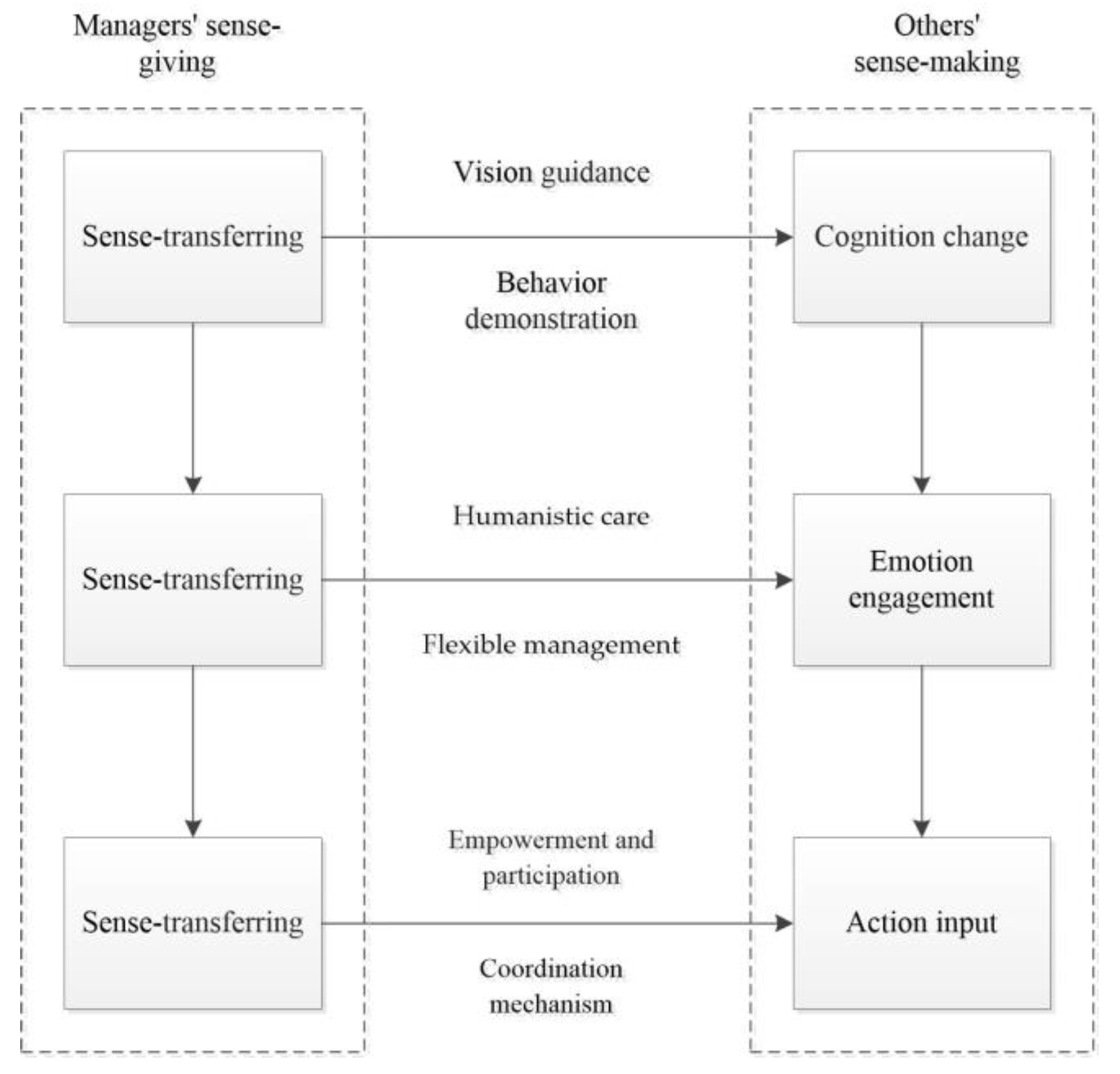

5.2. Sense Giving in the Open Innovation Implementation Stage

“On the one hand, we actively propagate our vision about open innovation to external partners, which enables us to drives mutual recognition and achieve consensus. Usually we are honest with them about our purpose and hope that we can do something together. On the other hand, we have repeatedly raised the crisis in formal and informal communications, and it has been highlighted in meetings”.[Manager #3]

“In the sharing session, I often said that there is more than one form of innovation, and closed innovation may not be the choice for each one, after all, the process is very difficult and requires a lot of efforts. Open innovation is indeed more valuable, and I hope more members will join in”.[Employee #1]

“We believe that timely detection of problems and instant communication is the most direct and efficient way to motivate employees”.[Manager #7]

“My efforts to obtain external innovation resources have been seen by the leadership, which makes me very gratified, so I am willing and confident to do better”.[Employee #3]

“The promotion mechanism is relatively fair, and those who can be promoted are more capable. We all agree on that. Those who actively participate in open innovation and have a strong ability to acquire external resources will have more promotion opportunities”.[Employee #2]

“For some people who participate in open innovation activities, on the one hand, we give them the right to participate in project decision-making to enhance their sense of ownership. On the other hand, we grant them the right to fully determine the external activities for which they are responsible, enhancing the sense of accomplishment”.[Manager #4]

“We and external innovation subjects can collaborate formally and/or informally. Both sides have to agree on the sharing of intellectual property, sign license agreements upfront. The proportion of intellectual property that we own and can use is generally based on its own value and market prospects”.[Manager #2]

“Relatively speaking, individual knowledge or information is highly implicit and not easy to share. To this end, we create a culture of knowledge sharing and improve corresponding incentive mechanisms. For example, reducing information asymmetry between managers and employees, establishing mutual harmonious interpersonal relations, encouraging employees to actively contribute knowledge to share, and so on. On the other hand, we also limit the scope of shared knowledge to protect critical core technologies”.[Manager #6]

5.3. Sense Interaction in the Open Innovation Development Stage

“At the project management level, in addition to regular meetings, there are also countermeasure meetings for individual issues. At the level of innovation practice, team meetings take place at any time. Meetings could thus be seen as a formal collective sense-making tool”.[Manager #5]

“I keep close personal contact with the relevant personnel in external partners, and often follow their latest scientific research dynamic. We often invite each other to exchange experiences online/offline, building a trust relationship. Their suggestions are very relevant, especially those of the experts, and sometimes they can hit the nail on the head”.[Manager #3]

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lehtinen, J.; Peltokorpi, A.; Artto, K. Megaprojects as organizational platforms and technology platforms for value creation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Mao, Y.H.; Lu, S.K. Fostering Participants’ Collaborative Innovation Performance in Megaprojects: The Effects of Perceived Partners’ Non-Mediated Power. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04022141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; MacAulay, S.; DeBarro, T.; Thurston, M. Making innovation happen in a megaproject: London’s Crossrail suburban railway system. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Le, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M. Fostering Ambidextrous Innovation in Infrastructure Projects: Differentiation and Integration Tactics of Cross-Functional Teams. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V.; Frattini, F. The Open innovation journey: How firms dynamically implement the emerging innovation management paradigm. Technovation 2011, 31, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsnop, T.; Miraglia, S.; Davies, A. Balancing open and closed innovation in megaprojects: Insights from crossrail. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Marques, C. University–industry cooperation: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sci. Public Policy 2018, 45, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, I.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Trajectories towards balancing value creation and capture: Resolution paths and tension loops in open innovation projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Locatelli, G.; Serafini, M. How does open innovation enhance productivity? An exploration in the construction ecosystem. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Chittipeddi, K. Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georg, M.; Ingo, P. Sensemaking and sensegiving: A concept for successful change management that brings together moral foundations theory and the ordonomic approach. J. Account. Organ. Change 2018, 14, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Tsoukas, H. Making sense of the sensemaking perspective: Its constituents, limitations, and opportunities for further development. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profting from Technology; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.; Salter, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: The next decade introduction. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Crowther, A.K. Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. RD Manag. 2006, 36, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E.; Chesbrough, H. The Future of Open Innovation. RD Manag. 2010, 40, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscherini, L.; Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V.; Frattini, F. How to use pilot projects to implement open innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2010, 14, 1065–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, J.C.F.; Salerno, M.S.; Freitas, J.S.; Bagno, R.B.; Brasil, V.C. Reprint of: From open innovation projects to open innovation project management capabilities: A process-based approach. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakemond, N.; Bengtsson, L.; Laursen, K.; Tell, F. Match and manage: The use of knowledge matching and project management to integrate knowledge in collaborative inbound open innovation. Ind. Corp. Change 2016, 25, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, I.; Faems, D.; Cruz, N.M.; Santana, P.P. The role of interpartner dissimilarities in Industry-University alliances: Insights from a comparative case study. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 2008–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Greco, M.; Invernizzi, D.C.; Grimaldi, M.; Malizia, S. What about the people? Micro-foundations of open innovation in megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Minshall, T.; Mortara, L. Understanding the human side of openness: The fit between open innovation modes and CEO characteristics. RD Manag. 2017, 47, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Foss, N.J.; Lyngsie, J. The “human side” of open innovation: The role of employee diversity in firm-level openness. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S. The Social Processes of Organizational sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D.; Stacey, P.; Nandhakumar, J. Making sense of sensemaking narratives. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1035–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Vogus, T.J.; Lawrence, T.B. Sensemaking and emotion in organizations. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 3, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren-Henriksson, E.L.; Kock, S. Coopetition in a headwind—The interplay of sensemaking, sensegiving, and middle managerial emotional response in coopetitive strategic change development. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 58, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Sonenshein, S. Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 552–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Lawrence, T. Triggers and enablers in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J. Sensemaking under pressure: The influence of professional roles and social accountability on the creation of sense. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Christianson, M. Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 57–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Zobel, A.K.; Afuah, A.; Almirall, E.; Brunswicker, S.; Dahlander, L.; Frederiksen, L.; Gawer, A.; Gruber, M.; Haefliger, S.; et al. The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 8–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren-Henriksson, E.L.; Kock, S. A sensemaking perspective on coopetition. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 57, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiette, A.; Vandenbempt, K. Change managerialism and micro-processes of sensemaking during change implementation. Scand. J. Manag. 2017, 33, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, D.; Yin, R. Case study research design and methods. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 44, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case selection techniques in case study research. Political Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, M.E.J.; Dor’ee, A.G.; Halman, J.I.M. Innovation and inter-organizational cooperation: A synthesis of literature. Constr. Innov. 2009, 9, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M. How open is innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Kankanhalli, A. Exploring innovation through open networks: A review and initial research questions. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B. Identity, image and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, C. Linking high involvement human resource practices to employee proactivity. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Orlando, B.; Valentina, C.; Nicotra, M.; Di Gioia, L.; Farina Briamonte, M. Uncovering the micro-foundations of knowledge sharing in open innovation partnerships: An intention-based perspective of technology transfer. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 152, 119906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Number | Acquisition |

|---|---|---|

| Managers interviews | 3 top managers and middle 4 managers | One-to-one semi-structured interviews varied from 30 to 60 min in length |

| Other interviews | 5 employees and 3 external personnel | Semi-structured interviews varied from 15 to 50 min in length. |

| Site observation | a total of one month observation in three phases | Participative observation as the main method, e.g., innovation communication meeting, team activities |

| Second-hand data | Public reports and internal documents | Internal publications, meeting minutes, investigation reports |

| Original Data | Conceptualization | First Order Themes |

|---|---|---|

| a1 At present, domestic infrastructure construction has been quite perfect, and fewer and fewer projects can be contracted. a5 Many companies are laying off workers. | aa1 Market saturation | A1 Fierce competition in market |

| a3 If there is no technological advantage, profits can only be compressed in the fierce competition, resulting in very little profit. | aa2 Fierce competition in the industry | |

| a22 Saving research and development costs, saving time. Even small innovations that bring benefits to the project are good. | aa15 Challenges brought by open innovation | A5 Challenges and opportunities brought by open innovation |

| a30 Intellectual property rights, Distribution of benefits, and other issues will bring negative impact. | aa16 Opportunities brought by open innovation | |

| a52 The company encourages new ideas and has supported some worthwhile ones. a53 Many employees have positive attitudes to new ideas. | aa21 Organizational culture | A9 Organizational innovation culture, policy support |

| a56 Providing certain financial support and convenience for innovation. a57 Bonus points in performance appraisal | aa22 Policy support |

| Second Order Themes | First Order Themes |

|---|---|

| XX1 Internal and external situation | A1 Fierce competition in market |

| A2 The demand for high-quality development of construction industry | |

| A3 Internal capacity limitations, as well as external resource demand | |

| XX2 Feasibility assessment | A4 Whether open innovation is reasonable in this megaproject |

| A5 Challenges and opportunities brought by open innovation | |

| A6 Managers’ re-recognition and positioning of their own organizational identity | |

| XX3 Positive emotion | A7 Optimistic and positive attitude towards the transformation of innovation mode |

| A8 Interested in trying and exploring open innovation mode | |

| XX4 Self-efficacy | A9 Organizational innovation culture, policy support |

| A10 Approval and commitment from the high office in CCCC | |

| XX5 Seeking external partners | A11 Seeking long-term and in-depth cooperation with existing partners |

| A12 Opening up innovation channels and seeking new partners | |

| XX6 Adjusting internal resources | A13 Cultivating employees with strong open mindset and open innovation ability |

| A14 Departmental personnel adjustment | |

| A15 Formulating relevant incentive mechanism |

| Stages | Aggregate Themes | Second Order Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Sense-making in formulation stage | X1 Cognition change | XX1 Internal and external situation |

| XX2 Feasibility assessment | ||

| X2 Emotion engagement | XX3 Positive emotion | |

| XX4 Self-efficacy | ||

| X3 Action input | XX5 Seeking external partners | |

| XX6 Adjusting internal resources | ||

| Sense-giving in implementation stage | Y1 Sense-transferring | YY1 Vision guidance |

| YY2 Behavior demonstration | ||

| Y2 Sense-enhancing | YY3 Humanistic care | |

| YY4 Flexible management | ||

| Y3 Sense-empowering | YY5 Empowerment and participation | |

| YY6 Coordination mechanism | ||

| Sense interaction in development stage | Z1 Formal sense interaction | ZZ1 Formal communication |

| ZZ2 Feedback and evaluation | ||

| Z2 Informal sense interaction | ZZ3 Informal communication | |

| ZZ4 Establishing personal relationships |

| Sources | Breadth | Depth | Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universities | 6 | 10 |

|

| Research institutes | 3 | 6 |

|

| Open platforms | 1 | 3 |

|

| Subcontractors | 3 | 2 |

|

| Suppliers | 3 | 2 |

|

| First Order Themes | Second Order Themes | Aggregate Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Fierce competition in market | Internal and external situation | Cognition change |

| The demand for high-quality development of construction industry | ||

| Internal capacity limitations, as well as external resource demand | ||

| Whether open innovation is reasonable in this megaproject | Feasibility assessment | |

| Challenges and opportunities brought by open innovation | ||

| Managers’ re-recognition and positioning of their own organizational identity | ||

| Optimistic and positive attitude towards the transformation of innovation mode | Positive emotion | Emotion engagement |

| Interested in trying and exploring open innovation mode | ||

| Organizational innovation culture, policy support | Self-efficacy | |

| Approval and commitment from the high office in CCCC | ||

| Seeking long-term and in-depth cooperation with existing partners | Seeking external partners | Action input |

| Opening up innovation channels and seeking new partners | ||

| Cultivating employees with strong open mindset and open innovation ability | Adjusting internal resources | |

| Departmental personnel adjustment | ||

| Formulating relevant incentive mechanism |

| First Order Themes | Second Order Themes | Aggregate Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Intensive communication with collaborators | Vision guidance | Sense-transferring |

| Propagandizing vision to external partners to identify with each other and build consensus | ||

| Creating vision to internal employees | ||

| Managers’ words and deeds to set an example | Behavior demonstration | |

| Sharing achievements and exchanging experience | ||

| Emotional support | Humanistic care | Sense-enhancing |

| Instant communication and praise | ||

| More human performance appraisal associated with open innovation | Flexible management | |

| providing more future promotion opportunities | ||

| Giving employees more autonomy and decision-making power | Empowerment and participation | Sense-empowering |

| giving employees the right to participate in decision-making | ||

| Intellectual property protection mechanism | Coordination mechanism | |

| Encouraging the sharing of knowledge and information |

| First Order Themes | Second Order Themes | Aggregate Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Establishing well-developed meeting communication system | Formal communication | Formal sense interaction |

| A variety of communication and learning platforms | ||

| Encouraging employees to provide feedback | Feedback and evaluation | |

| A transparent and open environment | ||

| Encouraging the activities of informal groups | Informal communication | Informal sense interaction |

| Chatting and interviewing with employees | ||

| Social activities | Establishing personal relationships | |

| Showing respect and friendliness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Liu, Q.; Fang, K. Micro-Process of Open Innovation in Megaprojects Under Sense-Making Perspective. Buildings 2024, 14, 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113464

Li F, Liu Q, Fang K. Micro-Process of Open Innovation in Megaprojects Under Sense-Making Perspective. Buildings. 2024; 14(11):3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113464

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fei, Quanle Liu, and Kai Fang. 2024. "Micro-Process of Open Innovation in Megaprojects Under Sense-Making Perspective" Buildings 14, no. 11: 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113464

APA StyleLi, F., Liu, Q., & Fang, K. (2024). Micro-Process of Open Innovation in Megaprojects Under Sense-Making Perspective. Buildings, 14(11), 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113464