Abstract

Innovation districts are widely known as an effective land use type for fostering and sustaining knowledge and innovation economy growth in cities. Knowledge workers and the public are among the main stakeholders and key drivers for the growth of innovation districts. However, these groups’ needs are often not well considered in the top-down implementation of innovation districts. This paper aims to explore the user preferences and decision makers’ perspectives in innovation district planning, design, and development. The study tackles the question of which characteristics fulfil the responsibility of innovation districts toward both societies (reflecting user preferences) and cities (reflecting decision makers’ perspectives). As for the methodology, a case study approach was employed to collect the required data from three innovation districts in Brisbane, Australia. The data are qualitatively and quantitatively analysed. The analysis findings highlighted the similarities between user preferences and decision makers’ perspectives—e.g., usefulness of decentralisation, urbanism, mixed-use development, street life, and social interactions in innovation districts—and the differences that need to be carefully factored into the planning, design, and development of innovation districts with a user-centric approach.

1. Introduction

The emergence of the knowledge and innovation economy has pushed cities into structural changes that are deemed necessary for flourishing growth [1,2]. In that regard, innovation districts are specific land-use settings for knowledge-driven and creative activities [3,4]. These districts not only meet the economic and industrial requirements of cities, but also sustain and balance their growth [5,6,7]. Current innovation districts attempt to associate with the concept of smart sustainable cities. As stated by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), a smart city “uses ICTs and other means to improve quality of life, efficiency of urban operation and services, and competitiveness, while ensuring that it meets the needs of present and future generations concerning economic, social, environmental as well as cultural aspects”.

In association with this perspective, knowledge-intensive activities need to be presented by different zones in cities besides central business districts (CBD) and downtowns that are the main locations of innovation districts [8,9]. This means that innovation districts have the potential to bring knowledge-related facilities and jobs to urban and suburban neighbourhoods to balance the growth potentials [10,11]. Innovation districts naturally cater for knowledge-workers who are highly educated and talented; these workers lead the knowledge economy in cities [12,13]. These districts also provide opportunities for their surrounding general public to be engaged in knowledge-intensive activities [14]. In other words, innovation districts benefit their direct stakeholders as well as people located in nearby neighbourhoods [15].

Urban planners and policymakers, therefore, deal with an extremely complicated phenomenon during the innovation district planning, design, and development stages in their cities [16]. At the same time, they are required to involve the growing interest in user preferences in this process—widely known as people-centric development [17,18]. The people-centric approach involves catering for all users and improving their quality of life [19,20,21,22]. Although some studies explored the preferences of knowledge workers and industries [23,24], there exists no holistic research that includes the preferences of both workers and the public.

This study aims to explore the user preferences and decision makers’ perspectives in innovation district planning, design, and development. The paper attempts to unify user and decision makers’ viewpoints to tackle the question of which characteristics fulfil the responsibility of innovation districts toward both societies (reflecting user preferences) and cities (reflecting decision makers’ perspectives). User preferences and decision makers’ perspectives are studied in the case study innovations of Kelvin Grove Urban Village, Diamantina Knowledge Precinct, and Brisbane Technology Park, located in Brisbane, Australia.

2. Literature Background

Innovation districts refer to industrial clusters with knowledge-intensive potentials involving universities, research institutes, and start-ups to facilitate innovation, networking, and knowledge spill-over opportunities [25]. These districts have been evolving since the 1970s. Early examples of innovation districts were secluded and mono-functional clusters in exurban areas, only focused on institutional and industrial development [26]. In the early 2000s, a new approach emerged that emphasised the concentration of talented and educated workers—the creative class of knowledge workers—as important elements in occupational and infrastructural aspects. Consequently, attracting such a workforce became a priority for innovation districts [10,27]. Knowledge workers were considered highly mobile workers who seek quality of life in a location rather than solely job opportunities [28,29]. In this regard, innovation districts experienced a transition towards urbanisation and multi-purpose development to support the knowledge workers’ expectations [2,30]. These districts were typically located closer to CBDs and relied on the existing dynamics of urban centres [31,32]. Innovation districts from Austin, Barcelona, London, Melbourne, Montreal, San Francisco, and Toronto are among the examples of this transition phase.

Nevertheless, the disproportionate concentration of jobs and amenities in urban centres has caused challenges for cities, including: (a) increased pressures on CBDs, (b) heightened job–housing imbalances, and (c) widened socioeconomic inequalities [29,33,34]. In response to these challenges, a new configuration of innovation districts has emerged during recent years. Besides the CBD and inner city, some suburban innovation districts are developed as an extension of neighbourhoods with no physical boundaries between the districts and their surroundings. These districts are extrovert, mixed-use, and offer a variety of jobs and functions for both workers and the public [35]. In return, the dynamic of these districts deeply relies on involving dense and diverse local communities [36,37]. With the emergence of these districts, work, study, and life have become present at all hours of the day [11,38,39]. One North in Singapore and Brooklyn Tech Triangle in New York are among the examples of this new generation of innovation district [10].

Consistent with these transition phases, earlier studies such as Porter [40] exclusively highlighted the tangible occupational/industrial characteristics of districts—hard factors, such as salary, the value of workspaces, the expense of running a business, tax exceptions, technical infrastructure, and urban mobility systems. Later studies [29,41,42] demonstrated the significant role of the knowledge workers, mostly focusing on the intangible characteristics of districts—soft factors, such as high-quality amenities, authenticity, variety of third places, walkability, diversity, and openness [43,44,45]. Despite the importance of soft factors for attracting knowledge workers, the popularity of hard factors is also noticed in the literature [46,47,48]. Therefore, in the last decade, most studies followed a balanced viewpoint including both soft and hard factors to define the characteristics of innovation districts [49,50,51].

Corresponding to this viewpoint, Esmaeilpoorarabi et al. [52] presented a multidimensional framework reflecting the most significant attributes that form innovation districts (indicators in Table 1). Form and function represent intangible hard factors such as location, physical structures, infrastructure, urban mobility systems, types of activities, labour market, and company profiles [53,54]. Ambiance and image signify soft factors such as social amenities and interactions, diversity, creativity, openness, lifestyles, vibes, and identity [55,56,57]. In addition, this framework includes ‘contexts’, a factor that links the characteristics of innovation districts to their cities/regions, including various economic, social, environmental, political, and governance indicators [58,59].

Table 1.

Key characteristics of case study innovation districts.

These characteristics need to be considered by decision makers when planning, designing, and developing innovation districts. Moreover, if innovation districts are to achieve a high rate of public acceptance, these characteristics also need to be redefined by the exact users of these districts. Although workers and the public are both key stakeholders/users, they are often ignored in the planning, design, and development processes of innovation districts [18]. Capturing and analysing user preferences would motivate them to accept and engage with innovation districts [60].

3. Research Design

3.1. Case Study

This research adopts the case study method [61] to identify user preferences and decision makers’ viewpoints. Eisenhardt’s approach [62], an inductive method with an arranged structure, is applied to the data gathering and analysis steps of the study to unify the structure of the research. The indicators shown in Table 1 are employed as the base structure. The study collects data from various sources, which are then analysed qualitatively and quantitatively.

The case study context is selected from Australia, a country that has, in recent years, shown significant attempts to improve its knowledge and innovation economy [63]. The third largest Australian city (in gross domestic product (GDP) terms), Brisbane has developed various strategies, policies, and plans to support knowledge and innovation economy growth [64]. Following these strategies, several innovation districts have been developed. Of these, the three most renowned innovation districts were selected—Kelvin Grove Urban Village (KGUV), Diamantina Knowledge Precinct (DKP), and Brisbane Technology Park (BTP). They are all planned districts, and this provides an opportunity to compare the initial plans and decision makers’ perspectives with user preferences. The place characteristics of these three cases are different from each other—e.g., centrality, physical form, company profile, and social characteristics (Table 1); these differences make the investigation more interesting and the findings more versatile.

3.2. Data Collection

First, the key users and decision makers were classified into five major groups. The main decision makers consist of: (a) academics and scholars whose practical theories are the base of action for other decision makers; (b) government executives, developers, and body corporates who are the main authorities in the planning and developing phases; and (c) architects and urban planners who are responsible for the designing phases. Key users include: (d) knowledge workers and company managers who are directly involved with the ongoing life of innovation districts on a daily basis; and (e) the general public who are involved in innovation districts on a casual basis. Then, data collection methods were selected for each group, considering the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data.

Qualitative data were collected through 15 scholarly articles from five academics/scholars (group a) whose institutes are in Brisbane and their research includes Brisbane innovation districts, and 27 semi-structured interviews from the three above-mentioned groups b, c, and d (Table 2). The interviewees, both decision makers and users, were directly engaged with these three innovation districts. Depending on the expertise or experiences of each group, the questions were designed for 45–60 min interviews. While the general questions were similar for all interviewees, the detailed questions were different. The interviews were conducted under negligible/low-risk human research ethics. The consent forms were signed by all interviewees. No personal data were reported at any stage of the research. Moreover, the sample size was based on the proposed number of 10 to 30 participants for qualitative research. In addition, 384 online surveys with open-ended questions from the public across Brisbane were also used (group e). The target group was people who live within 30 km of case study districts, with access to pre-existing infrastructure. “The number of participants was determined based on the sample size method proposed by Krejcie and Morgan (1970). The responses were checked for completeness; cases with missing data were excluded from further analysis. This resulted in 343 valid responses” [37].

Table 2.

Interviewee expertise and involvement.

The quantitative data were collected using 32 online surveys gathering data from five targeted academics/scholars and 27 interviewees. These interviewees are asked to complete the Likert-scale questions that aimed to evaluate the place characteristics of each case study district in detail. The aim was to collect numeric data to be compared with the qualitative data collected from the academics and interviewees. These data were interpreted in association with the qualitative data. Considering the limited number of surveys, the results were double-checked with the qualitative results. The above-mentioned 384 online surveys (343 valid) that gathered data from the public across Brisbane were also used for quantitative data collection. However, as some of the members of the public may not be directly engaged with the case study innovation districts, they were not asked to score the characteristics of the cases. Instead, the questionnaire collected data on the general characteristics/roles of innovation districts with which the public is familiar. The questions of the survey were designed based on the decision makers’ perspectives on the general characteristics of Brisbane’s innovation districts, derived from the qualitative analysis results. These questions explored whether the public agrees with the decision makers’ perspectives.

3.3. Data Analysis

The framework (Table 1) was employed in designing and coding the qualitative and quantitative data; since all districts are in Brisbane, the ‘context’ theme of the framework was excluded from the coding system. The qualitative data from articles, interviews, and open-ended questions were coded considering the 32 pre-planned indicators (Table 1), and then content analysis was conducted in NVivo. The results were reported comparatively. The results indicated whether the current characteristics of innovation districts, which are established by decision makers, meet the expectations of the users.

In total, 32 detailed Likert-scale surveys (5-point scale) were coded and uploaded to SPSS software. “The ordered nature (5-point Likert scale) of the outcome variables justifies the selection of ordinal regression model” [37]. Along with the descriptive analysis, ordered probit regression models were also calculated. The results specified whether the decision makers perceive district characteristics differently from the users. The ordinal regression model was selected due to the ordered nature of Likert scale variables. Only the significant (p < 0.05) indicators were reported.

Similarly, quantitative data from 343 valid public surveys were coded by indicators and uploaded into SPSS. Initially, the responses were checked by a control question, which provided the option of ‘I have never heard about innovation districts’. In total, 65 participants with no knowledge about innovation districts were excluded. The public rated their agreement with the overall characteristics/roles of innovation districts in their city that were seen to be thriving from decision makers’ perspectives (278 responses remained valid). They rated their agreement from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The rating system was recoded into three categories to accelerate the analysis, including agree (1), neutral (2), and disagree (3) [65]. Then, a one-sample t-test was conducted to explore whether the differences between the percentage of agreement and disagreement were significant (test value = 2 as neutral, p < 0.05). Only the significant differences were accepted as reliable experiences.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Analysis

The data were collected through: (a) 15 articles from academics; (b) 27 semi-structured interviews from different groups of decision makers and direct users (Table 2); and (c) 278 valid surveys with three open-ended questions from Brisbane residents, including ‘Which characteristics or activities in innovation districts would encourage you to join these districts?’, ‘Which characteristics of innovation districts contribute to increasing the quality of life?’, and ‘What is the role of innovation districts in future cities?’. The results demonstrate a variety of similarities and differences between the sample groups, as presented in Table 3. These differences are reported in Section 4.1.1, Section 4.1.2, Section 4.1.3 and Section 4.1.4.

Table 3.

Similar characteristics of innovation districts.

4.1.1. Form

Location: While all categories of participants believed in the advantage of decentralised districts, the perception of decision makers from suburban districts was different from users. Decision makers, such as Interviewees #2 and #12, defined the suburban BTP as “too far out” and “in the middle of nowhere”. However, direct users of BTP such as Interviewees #22, #24, #25, and #26 happily defined it as an “Ideal place to work, basically because of the location”, “It’s good because there is less traffic to get there”, “It’s not in the city, but then it’s not very far from the city”, and “it’s closer to the suburbs, supporting people with growing families”.

Urban form and structure: While decision makers solely focused on high-density development, both direct users and citizens expected diversity in terms of building size and living options. Users believed that focusing on huge or high-rise buildings limited their options.

Design: Despite similarities, there were three obvious gaps between decision makers’ and users’ opinions. Firstly, users anticipated an opportunity to not only share their expectations and needs in the designing process, but also have a role in shaping their location; they reflected it as “too much fixed design”, which destroyed their chance for personalising the place. Secondly, the decision makers mostly preferred iconic architecture and urban design for innovation districts. However, users expected a balance between an iconic and usual design that perfectly connects the districts to the city fabric. Thirdly, users frequently asked for an environmental-friendly design in their districts—fewer carbon emissions and more solar power. This preference concerns the development of smart sustainable cities. The balance between becoming smarter and remaining sustainable needs to be considered.

Amenities: The participants frequently stated the importance of smart amenities in addition to essential ones. However, all levels of society need to have equal access to these amenities. Such a mechanism is in line with the concept of smart sustainable cities that encourage social equality.

4.1.2. Function

Services: The users questioned current policies and plans for developing innovation districts. They reportedly compared their cities to global leading cities. A respondent mentioned sorrowfully that: “Simply calling someplace an innovation district is not enough. It needs real planning as in Singapore”. Moreover, while the decision makers were concerned about general strategies such as public–private investments, the users were mostly worried about tangible realities such as lack of parking. For example, Interviewee #21 mentioned, “we don’t have any parking. For lots of people it’s an inconvenience if they have children”.

Land use: The users were happy about mixed-use development in districts. They experienced the presence of working, studying, and living options in their districts, which activate the space. However, they preferred not to live in the same location in which they work. Interviewee #14 stated, “I don’t think I would live in the precinct. I work here and I don’t want to live and work in the same place”. Furthermore, the users were unsatisfied with the renting and purchasing prices; a citizen sadly commented: “Don’t try to sell them to the normal folk who work for a living and struggle to survive on minimalist wages, while the elites live in luxury”; Interviewee #21 complained that “houses start at more than a million dollars to buy here and rents are very expensive as well.” In addition, users were unsatisfied with the unbalanced development of functions in their districts; for example, KGUV is occupied by residential blocks and lacks working places, while living options are limited to social and student housing.

Company profile/technology: Both direct users and citizens questioned large-sized businesses. Medium to small businesses, and specifically start-ups, are necessary. They also complained that education and technology need to be accessible and affordable for all, which is expensive now.

Work condition: Despite all of the similarities, there is still a huge gap between the perception of decision makers and the expectations of workers in terms of jobs. Decision makers, especially academics, brand knowledge workers as highly mobile employees who seek shifts between jobs; they believe knowledge workers follow jobs in high-quality locations rather than giving priority to high-salary work. However, the results showed that only young workers match these definitions. Middle-aged workers and workers with families still preferred stability in their jobs as well as well-paid opportunities.

4.1.3. Ambiance

Public spaces and events: Users expected not only unrestricted accessibility, but also the match between their needs and districts’ spaces and programmes.

Public engagement: Knowledge workers needed informal and incidental forms of professional networks with both like-minded co-workers and people from other disciplines. Moreover, incidental interactions accelerate linking to locals. Interviewees #10 and #16 described this informal ambiance in KGUV as follows: “There are lots of incidental spaces where you meet people. So, the whole idea of circulation realm is to meet people”. “It helps your working relationships when occasionally, accidentally or co-incidentally run into people”. Moreover, the public believed that current innovation districts are not successful in developing attractive ambiance due to the lack of both funding and efficient management.

Diversity: the users admired innovation districts that avoid placing too many of the same professions in a district. This provides an opportunity for shaping a heterogeneous community with different lifestyles, e.g., having both artists and scientists in a district. Innovation districts also need to equally value the general public rather than their elite community.

Creativity: There were no significant differences observed between the decision makers and users.

4.1.4. Image

Buzz of place: Despite the similarities, the decision makers and workers had inconsistent opinions about mono-functional districts. The decision makers believed that mono-functional districts are not capable of attracting workers due to the lack of dynamic lifestyles (soft factors). However, the BTP workers mostly mentioned hard factors such as affordability, the presence of well-known companies, and well-paid jobs as attractive factors in BTP.

Sense of safety: Again, mono-functional districts were identified as the subject of disagreement. The decision makers expected that the presence of special functions such as residential blocks or specific characteristics such as nightlife dramatically impacts the sense of safety. However, the experience of workers in DKP and BTP demonstrated that a sense of safety is more related to factors such as a safe urban/architectural design as well as high levels of safety in Brisbane (city scale).

Sense of place: Despite all of the attempts of the decision makers, the public constantly highlighted the current inequality between the community of workers and locals. One participant explained this inequality: “To me, it seems to be cultivating a new elite. It increases the value of nothing. It feeds off its over-inflated ego”. Another participant described it as: “This sounds good, but in practice, the non-educational members would need to be equally enthusiastic”.

Identity: The decision makers mostly believed that iconic architectural/urban designs, in addition to unique vibes, are major keys for branding (soft factors). However, the results showed that users still believed that districts’ reputation is mostly built by the company profiles, job opportunities, and infrastructures that they can provide (hard factors).

4.2. Quantitative Analysis

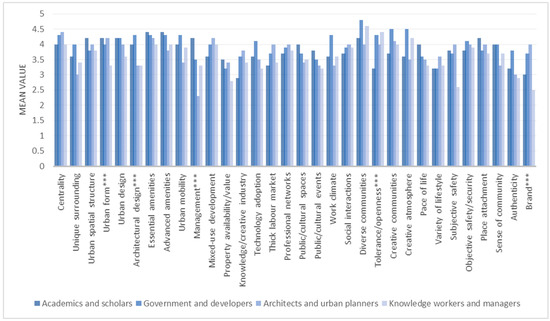

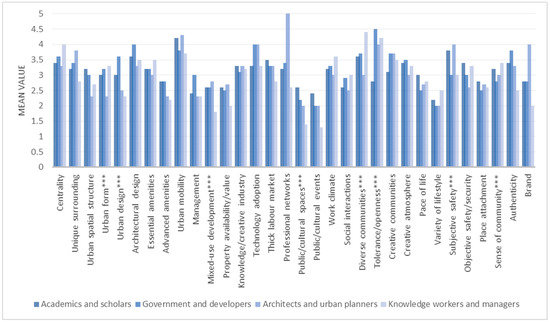

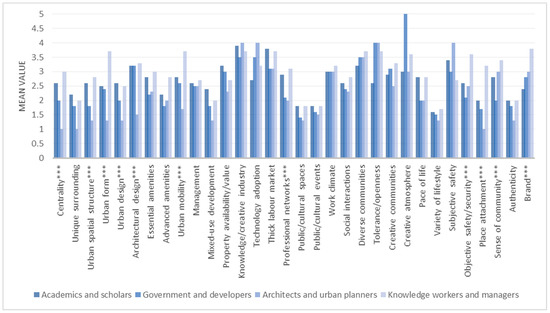

In this study, 27 interviewees and 5 academics (32 participants in total) were asked to assess the detailed characteristics of the case studies. For each group of participants, the mean values were calculated. Ordered probit regression models were also estimated to compare the scores among four groups of participants. Knowledge workers and managers, who are the direct users of districts, were coded as the reference group. The collected data from three other groups of participants including: (a) academics/scholars; (b) government executives, developers, and body corporates, and; (c) urban planners, designers, and architects were compared to the reference group in each case study district (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). The results demonstrated 9 (5 indicators), 9 (8 indicators), and 14 (11 indicators) cases of discrepancy between the groups of participants in KGUV, DKP, and BTP, respectively. Significant indicators are shown with (***) in the figures.

Figure 1.

Quantitative evaluation of place characteristics in Kelvin Grove Urban Village.

Figure 2.

Quantitative evaluation of place characteristics in Diamantina Knowledge Precinct.

Figure 3.

Quantitative evaluation of place characteristics in Brisbane Technology Park.

In total, 278 valid Likert-scale questionnaires from the public across Brisbane were initially identified. Then, 55 questions collected from each participant were classified based on the introduced framework (Table 1). The percentage of agreement was calculated for individual questions and validated using the one-sample t-test (Table 4). In total, 44 questions were identified as reliable experiences since there were no significant differences between the agreement and disagreement scores for the other 11 questions (bold-italic questions in Table 4). While the questions reflected decision maker opinions, the public only disagreed with seven items (bold-italic values under the disagreement percentage in Table 4). Conversely, the public showed high levels of agreement (>50%) in 14 cases (bold-italic values under the agreement percentage in Table 4).

Table 4.

Quantitative evaluation of place characteristics in Brisbane.

Form: While KGUV received the highest score between districts, workers/managers from the creative industries and health sectors still expected more from the urban form and design. Almost all groups of participants agreed on the negative aspects of urban form and design in DKP. Conversely, the knowledge workers/managers in BTP from the ICT sector were less concerned about centrality, urban form, and design in comparison to the decision makers. The public and decision makers agreed on the positive part of innovation districts in providing high-quality open spaces alongside essential and advanced amenities. However, the public believed that innovation districts are incapable of preserving the natural environment. Moreover, unlike the decision makers, the public perceived that the current innovation districts integrated well with the neighbourhood.

Function: The academics/scholars showed a higher level of acceptance for public/private development and other planning and managing strategies in KGUV, while urban planners/designers/architects found the current management system less successful. In DKP, the workers/managers had significantly higher expectations for more mixed-use development in comparison to the decision makers. In BTP, the urban planners/designers/architects believed that being located at a long distance from the CBD has negatively influenced the urban mobility system. However, the direct users were generally satisfied with the condition. Most groups of decision makers also expected lower levels of professional networks in introverted and mono-functional districts such as BTP. The professional networks were of a much higher level. Both the decision makers and the public agreed that urban mobility and professional networks were improved by the presence of innovation districts in neighbourhoods. However, the public questioned the ability of innovation districts to provide reasonably priced properties in their neighbourhoods.

Ambiance: The theoretical opinions of the academics/scholars are different from user experiences in the case of public/cultural spaces and tolerance in KGUV and DKP. However, the decision makers’ perspectives and direct user experiences are mainly similar for other items. On the other hand, the public showed higher levels of tolerance and openness as opposed to the decision makers’ perceptions.

Image: In DKP, the workers/managers experienced lower levels of subjective safety despite the decision makers’ optimistic views. Conversely, in BTP, the workers/managers experienced higher levels of objective safety and a sense of place in comparison to the decision makers. In the case of authenticity and branding, the decision makers assigned higher scores to KGUV and DKP and lower scores to BTP, while direct users experienced it differently: 2.5, 2, and 3.8 in KGUV, DKP, and BTP, respectively. The decision makers expected that the public has negative images of innovation districts, such as ‘being hectic or overcrowded’ or ‘feeling banned from being there’. However, the results not only rejected these negative images, but also verified the positive role of innovation districts in terms of (a) accessibility to different lifestyles, (b) improving subjective safety, and (c) enhancing the reputation of neighbourhoods.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the preferences of users in comparison to approaches that decision makers follow in the planning, design, and development of current innovation districts. The results revealed plenty of characteristics that both users and decision makers similarly expect from innovation districts (Table 3). In general, these similarities showed that current innovation districts are beyond introverted/mono-functional occupational and educational hubs; they are the nexus of urbanism, mixed-use development, street life, and social interactions in neighbourhoods. The public has the increasing chance to benefit from the amenities and activities offered by innovation districts. Both users and decision makers agreed with the emergence of urbanism and social life in innovation districts, which is also frequently mentioned in the literature [11,32,38].

Furthermore, both users and decision makers believed in decentralising innovation districts in inner-city neighbourhoods. They expect innovation districts to accelerate the job–housing balance in cities like many scholars following the ‘smart sustainable city’ strategies [66,67]. The presence of innovation districts in neighbourhoods not only reduces the commuting time, but also involves more parts of cities in knowledge-intensive activities; the aim is to shape smarter cities and populations [9,68].

Besides the abovementioned similarities and many other characteristics that both users and decision makers were unanimous about, this study identified 22 cases of disagreement. The results provided insights into the following characteristics (shown in Table 5 and elaborated below) that need to be revisited in building prosperous innovation districts.

Table 5.

Insights derived from dissimilarities.

Form:

- Centrality is not a priority for all types of workers; for example, ICT workers in BTP were satisfied with their quiet and less expensive location. However, all workers expect innovation districts to be highly connected to CBDs and other urban centres. Even though DKP is located close to the CBD, most workers were unsatisfied with the isolated location. Decision makers need to consider connectivity rather than solely closeness to CBDs.

- While decision makers confidently gave high scores to KGUV’s urban form and extremely low scores to BTP, the choice of workers were different—3.3 and 3.7 for KGUV and BTP, respectively. KGUV lacks parking, workplaces, and a diversity of housing options and instead is occupied by quite tall student accommodation buildings, faculty buildings, and huge research institutes; in other words, KGUV still has a campus form rather than being an innovation district. On the other hand, BTP is more professional. This study suggests that decision makers need to revise their perception that a campus form or an urban village concept can fulfil the requirements of an innovation district. Innovation districts are ‘professional configurations’ for work, study, and living that require a distinguished form from other functions such as universities or research hubs. They also need to be combined with a balanced number of other functions and facilities.

- Unlike decision makers, users expect a hierarchy of places, including planned and designed parts as well as flexible ones. Decision makers should designate a space for the public and workers to shape their place identity and build a sense of attachment [69]. In addition, a flexible design will blur the boundary of innovation districts within their neighbourhoods.

- Decision makers believe that innovation districts are leaders of future urban developments in cities. Therefore, they prefer iconic urban/architectural design for shaping innovation districts, e.g., DKP. This strategy undesirably separates these districts from the city fabric. This research recommends that a balance between iconic and usual design would be suitable for integrating innovation districts into neighbourhoods and attracting the public.

- Decision makers need to plan for an environmentally friendly form of place that respects the concern of users about the natural environment and their health. Otherwise, they will lose the public trust in the efficiency of innovation districts for their cities. In recent years, countries such as China and Japan have employed the concept of healthy urban areas in their innovation districts; their priorities are: (a) constructing healthy environments; (b) building a healthy society; (c) optimising health services; (d) fostering healthy people; and (e) developing healthy culture [70].

- Despite the attempts of decision makers to accomplish open-door policies and benefiting society [38], there is no balance of amenities for all levels of society. At least some activities and services need to meet the expectations of the locals [59]. These facilities must also be accessible and affordable for most people.

Function:

- Urban mobility relates more to ease of access than to public transport. Both DKP and BTP workers evaluated the urban mobility the same—3.7. BTP is highly accessible by car and lacks public transport; oppositely, urban mobility in DKP is restricted to public transport. Decision makers need to accelerate ease of access to innovation districts through all forms of the urban mobility system. In this regard, smart mobility plans can be employed to encourage users to choose different modes of transport; this is widely known as ‘mobility-as-a-service’ (MaaS) [71,72,73].

- Users do not trust the efficiency of the management system in shaping world-class innovation districts that improve their wellbeing. Decision makers, theoretically and practically, should inform and assure users that innovation districts have been professionally planned to serve them. Communicating with users, consulting with them, and directly engaging them in the decision-making process are highly recommended. St. Louis (Missouri), San Diego (California), Detroit Innovation District, and Boston Innovation District are examples of districts that have followed various community engagement plans to gather public and political support [74].

- Decision makers mainly follow a holistic approach for planning innovation districts at the city scale. However, users deal with the tangible characteristics of innovation districts on neighbourhood scales [50]. Decision makers need to replace their current method with a multi-scale plan.

- Both workers and locals prefer not to work and live in the same area. Decision makers need to plan for a new model of an urban setting that keeps the living areas private.

- Innovation districts have been partially effective in mixed-use development and bringing jobs/amenities to neighbourhoods; however, they still struggle with job–housing/amenity matching and balance, e.g., KGUV. The importance of matching and balancing uses has been frequently recommended [75] and needs to be considered by decision makers in the planning phases. In addition, studying valuable plans from other countries for achieving sustainability in the long term is suggested, e.g., Hong Kong [76], Nanjing [77], and Singapore [78].

- Innovation districts are effective in gentrification and increase the value of properties in the neighbourhood accordingly [79]. A lack of reasonably priced workplaces and housing threatens the social mix. Decision makers should anticipate price-controlling plans before establishing innovation districts.

- In both structural and marketing plans, innovation districts need to be prepared for hosting large companies as well as small-/medium-sized businesses and start-ups, e.g., BTP. A lack of diversity will disappoint users, e.g., KGUV and DKP. The Cortex Innovation Community in St. Louis, High Tech Campus Eindhoven, and 22@Barcelona are among the examples of combining various sizes of businesses [80].

- Innovation districts provide no targeted job/educational opportunities for locals who live around the area. The challenge of linking locals to knowledge-based activities is critical [11]. Decision makers should allocate some affordable services and programmes to educate locals.

- Following the ‘creative class hypothesis’ [29], decision makers increasingly value soft quality-based factors for attracting talent to innovation districts. However, the result showed that talented workers initially choose their location based on hard traditional factors such as stability, highly paid jobs, tax-exempting opportunities, and low-rent properties.

Ambiance:

- Decision makers are responsible for introducing, branding, and advertising the social character of innovation districts. This responsibility is undoubtedly beyond moving physical barriers and offering their professional amenities. A community development system is required to not only link locals and workers, but also identify the catalyser activities and amenities.

- Decision makers need to consider that the public, like talented workers, respect diverse communities and are tolerant of openness.

Image:

- Mono-functional districts that offer a variety of appealing hard factors can still be attractive for some categories of workers, e.g., ICT workers in BTP.

- While centrality, nightlife, and the presence of housing blocks improve safety in innovation districts, design and connectivity are the most effective elements in shaping a sense of safety, since KGUV and BTP showed the same sense of safety.

- The public not only has no negative image of innovation districts, but, like workers [48], enjoys high-quality places, authenticity, and dynamic vibes. The public only expect unlimited access to these facilities.

- Decision makers should be aware that innovation districts, unexpectedly, raise the social and economic inequality in society [8,29,32,81,82]. Social coherency needs to be shaped between the community of workers and the locals. Otherwise, innovation districts will threaten social sustainability in neighbourhoods.

- Branding is highly supported by the company profile and economic performance of innovation districts [83,84], e.g., BTP = 3.8. In the absence of these elements, factors such as authentic vibes and award-winning architecture have less influence, e.g., KGUV = 2.5 and DKP = 2.

6. Conclusions

This analysis disclosed the characteristics of innovation districts that successfully deliver their responsibility toward cities and societies. It also identified decision makers’ perspectives and how they differ than those of users. The paper discussed these dissimilarities, generated insights, and advocated for the adoption of a user-centric approach in innovation district planning. The study contributes to the efforts in knowledge-based development of cities through innovation districts [85].

Scholars should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted. Our prospective research will involve more detailed analysis with the engagement of larger stakeholder groups from a larger number of innovation district cases from different city and country contexts.

Additionally, it is necessary to consider two general research limitations. Firstly, the study only involves three cases, and therefore limits the place-specific characteristics to be generalised. A comparative analysis was conducted to decrease the impact of location on the results. However, a study of global best practices would help generalise the findings. Secondly, all case studies were placed in the same context (Brisbane city). The experience of innovation districts in other cities could be different from these case study districts. Before generalising the outcomes, other contexts need to be investigated as well.

Author Contributions

N.E.: data collection, processing, investigation, analysis, and writing—original draft; T.Y.: supervision, conceptualisation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Ethical approval was received from the University Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 1700000201). Informed consent for data collection was obtained from all study participants. Some of the collected data might be available, subjected to ethics guidelines, upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and anonymous referees for their invaluable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bontje, M.; Musterd, S. Creative industries, creative class and competitiveness. Geoforum 2009, 40, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P. Complex spaces. J. Open Innov. 2017, 3, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Public space design of knowledge and innovation spaces. J. Open Innov. 2015, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-McVie, R.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Erol, I.; Xia, B. Classifying innovation districts. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, K. The strategic dimensions of knowledge industries in urban development. DISP Plan. Rev. 2009, 45, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.; Van Winden, W. Planned knowledge locations in cities. Int. J. Knowl. Based Dev. 2017, 8, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Dodson, J.; Gleeson, B.; Sipe, N. Travel self-containment in master planned estates: Analysis of recent Australian trends. Urban Policy Res. 2007, 25, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayanan, C. A critique of innovation districts: Entrepreneurial living and the burden of shouldering urban development. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2022, 54, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Fabian, L.; Coiacetto, E. Challenges to urban transport sustainability and smart transport in a tourist city: The Gold Coast, Australia. Open Transp. J. 2008, 2, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Winden, W.; De Carvalho, L.; Van Tuijl, E.; Van Haaren, J.; Van den Bergs, L. Creating Knowledge Locations in Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.; Wagner, J. The Rise of Innovation Districts; Brooklyn Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. ‘Creative industry clusters’ and the ‘entrepreneurial city’ of Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3561–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Florida, R.; Pogue, M.; Mellander, C.; Gugler, P.; Ketels, C. Creativity, clusters and the competitive advantage of cities. Compet. Rev. 2015, 25, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Adu-McVie, R.; Erol, I. How can contemporary innovation districts be classified? A systematic review of the literature. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. How can an enhanced community engagement with innovation districts be established? Cities 2020, 96, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Horton, S.; Velibeyoglu, K.; Gleeson, B. The Role of Community and Lifestyle in the Making of a Knowledge City; Griffith University: Brisbane, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T.; Burley, J. Assessing user preferences on post-industrial redevelopment. Environ. Plan. B 2016, 43, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Chen, J.; Wei, H.; Su, Y. Towards people-centric smart city development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, I.; Zarlenga, M. Smart city or smart citizens? J. Strategy Manag. 2015, 8, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H. The effects of successful ICT-based smart city services: From citizens’ perspectives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, V.; Fernandez, J.; Giffinger, R. Smart City implementation and discourses. Cities 2018, 78, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Casagrande, R.; Sarate, J.; Silva, K. Smart city and quality of life: Citizens’ perception in a Brazilian case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheim, B.; Hansen, H. Knowledge bases, talents, and contexts. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S.; Tremblay, D. What attracts and retains knowledge workers/students? Cities 2010, 27, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Huang, H.; Walsh, J. A typology of innovation districts. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Societal integration that matters. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 13, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Governance that matters. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, P.; Murphy, E.; Redmond, D. Residential preferences of the creative class? Cities 2013, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The New Urban Crisis; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benneworth, P.; Ratinho, T. Reframing the role of knowledge parks and science cities in knowledge-based urban development. Environ. Plan. C 2014, 32, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Edward, L. Glaeser, review of Richard Florida’s the rise of the creative class. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2005, 35, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, S.; Han, J. Innovation districts and urban heterogeneity: 3D mapping of industry mix in downtown Sydney. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 568–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlin, J. The post-industrial shop floor. Antipode 2016, 48, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Attributes of successful placemaking in knowledge and innovation spaces. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 693–711. [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Placemaking for innovation and knowledge-intensive activities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, R.; Trip, J. Planning for quality? J. Urban Des. 2011, 16, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. How does the public engage with innovation districts? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, E.; Hu, R. Crafting Innovative Places for Australia’s Knowledge Economy; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Inkinen, T. Geographies of Disruption; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. The competitive advantage of nations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E. Are cities dying? J. Econ. Perspect. 1998, 12, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Place quality in innovation clusters. Cities 2018, 74, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E. Best places. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 1909–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, A.; Bendit, E.; Kaplan, S. Residential location choice of knowledge-workers. Cities 2013, 35, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Home from home? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2336–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M.; Scott, A. Rethinking human capital, creativity and urban growth. J. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 9, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. Jobs or amenities? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2010, 89, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfken, C.; Broekel, T.; Sternberg, R. Factors explaining the spatial agglomeration of the creative class. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2438–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, T.; Young, C.; Kulturgeografiska, I.; Stockholms, U.; Samhällsvetenskapliga, F. Getting creative with the creative city? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz, S. Analyzing the quality of place. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Mayere, S.; Caldwell, G.; Medland, R. University and innovation district symbiosis in the context of placemaking. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Evaluating place quality in innovation districts. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Mczyski, M. Complexities. Built Environ. 2009, 35, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.; Buckwold, B. Precarious creativity: Immigrant cultural workers. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2013, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, N.; Cooke, P. Creative knowledge workers and location in Europe and North America. Creat. Ind. J. 2009, 2, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Heebels, B.; Van Aalst, I. Creative clusters in Berlin. Geogr. Ann. 2010, 92, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M. Liveability, quality and place identity in the contemporary city. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2010, 3, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip, J. The role of urban quality in the planning of international business locations. J. Urban Des. 2007, 12, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does place quality matter for innovation districts? Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hwang, M.; Chen, Y. An empirical study of the existence, relatedness and growth theory in consumers selection of mobile value-added services. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 7885–7898. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research, Design and Methods; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; Costa, E.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Ioppolo, G. Stimulating technological innovation through incentives. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Taboada, M.; Pancholi, S. Placemaking for knowledge generation and innovation. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mommaas, H. Cultural clusters and the post-industrial city. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, S.; Ogden, I. Planning the innovation agenda for sustainable development in resource regions. Resour. Policy 2014, 39, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Pique, J. The renaissance of the city as a cluster of innovation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M.; Pitt, M. The characters of place in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2014, 19, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.; Koh, K. Building a Healthy Urban Environment in East Asia; Report No. 1; Joint Lab on Future Cities (JLFC): Hong Kong, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, L.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Paz, A. Barriers and risks of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) adoption in cities: A systematic review of the literature. Cities 2021, 109, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyavina, E.; Nikitas, A.; Njoya, E. Mobility as a service (MaaS): A thematic map of challenges and opportunities. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.; Gkiotsalitis, T.; Fioreze, G.; Visser, G.; Veenstra, M. Chapter Three—The Potential of a Mobility-as-a-Service platform in a Depopulating Area in The Netherlands: An Exploration of Small and Big Data. In Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Franklin, R., Van Leeuwen, E., Paez, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, J.; Kayanan, C.; Renski, H. Innovation Districts as a Strategy for Urban Economic Development: A Comparison of Four Cases. Center for Economic Development Technical Reports. 2019, p. 192. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3498319 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Loo, B.; Chow, A. Jobs-housing balance in an era of population decentralization. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.L.; Mak, H.W.L. From Comparative and Statistical Assessments of Livability and Health Conditions of Districts in Hong Kong towards Future City Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Yang, J. Scale, distribution, and pattern of mixed land use in central districts: A case study of Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre of Livable Cities, Singapore: Integrating Land Use and Mobility. Available online: https://www.clc.gov.sg/research-publications/publications/urban-systems-studies/view/integrating-land-use-mobility (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Lee, J.; Hancock, M.; Hu, M. Towards an effective framework for building smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 89, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Hogan, M.; Brown, E. Planning for an Innovation District: Questions for Practitioners to Consider; No. OP-0059-1902; RTI Press: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gabe, T.; Florida, R.; Mellander, C. The creative class and the crisis. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2012, 6, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisson, A.; Bevilacqua, C. Balancing gentrification in the knowledge economy: The case of Chattanooga’s innovation district. Urban Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M. The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Mark. Theory. 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Kavaratzis, M.; Zenker, S. My city–my brand: The different roles of residents in place branding. J. Place Manag. Development. 2013, 6, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Bulu, M. Dubaization of Istanbul: Insights from the knowledge-based urban development journey of an emerging local economy. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).