Abstract

The tendency of infrastructure projects to be complex, large-scale, and long-term prompts temporary project organizations’ need to have resilience to deal with various risks, uncertainties, and crises. The resource and cognitive capacity of stakeholders are key factors in infrastructure project governance and crisis response in the face of shock generation. Moreover, previous studies on organizational resilience of infrastructure projects have lacked exploration from project governance perspectives. Hence, the objective of this study is to investigate the influence of contractual and relational governance on the organizational resilience of infrastructure projects from the perspectives of resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition. Firstly, this study established a conceptual model through a theoretical background and hypotheses development. Then, a questionnaire was designed for participants in the infrastructure projects to collect data on the respective effects of each variable. A total of 519 complete responses to the questionnaire were collected, and a path model was developed to quantitatively measure the impact of contractual and relational governance on organizational resilience using the partial least squares–structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method. Finally, the model was validated using reliability and validity testing, hypotheses testing, and mediating effect testing. The results of the study showed that the contractual and relational governance can enhance the level of organizational resilience. Resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition play a mediating role in the relationship between project governance and organizational resilience. This study extends the theoretical research on the impact of project governance on organizational resilience, and deepens the intrinsic link between the two from the perspective of resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition, so as to provide effective theoretical guidance for crisis response and sustainable operation of infrastructure projects.

1. Introduction

The construction of infrastructure projects acts as a significant engine for global economic development, with the scale and sophistication of such construction projects being a crucial element of a nation’s core competitiveness [1,2]. Infrastructure projects often face various crises, disasters, and risks in the process of project implementation and operation [3,4]. For example, statistics from the China Construction Industry Association show that 60.95% of construction companies suffered a significant impact on production under the impact of COVID-19 [5]. The volatility of the external environment and the occurrence of many accidents place the organization of major infrastructure projects in a complex situation with many crises and dynamics [6,7]. Therefore, the inherent complexity, large scale, and long-term nature of infrastructure projects necessitate that temporary project organizations possess organizational resilience to effectively manage a multitude of adversarial factors.

Organizational resilience is regarded as a capability of the organization [8,9,10]. In the field of construction, the project organization needs to have the passive adaptation ability to cope with changes and the active ability to solve problems, so as to ensure that the project organization can still run smoothly when it is disturbed by external changes. In the context of the construction industry transformation and high-quality development, if construction project organizations cannot withstand the industry changes brought about by emerging technologies and policy changes and lack adaptability and resilience, then there is no way to talk about construction project performance [11,12]. Therefore, improving the organizational resilience of construction projects is a realistic need to improve project performance, and has become a key issue of widespread concern for scholars and practitioners in the field of infrastructure project management.

Organizational resilience helps to improve the organization’s situational awareness, predict environmental changes, and resist the interference of risks to organizations. This is an essential ability for the organization to survive and grow in a turbulent and changing environment [13]. Thus, improving organizational resilience is critical to the sustainable operation of infrastructure projects. To ensure the effective achievement of infrastructure project objectives, its crisis management needs to consider the formal constraint (contractual governance) and informal (relational governance) constraint among multiple participants from the governance perspective. Contractual governance emphasizes formal rules and the importance of contracts between transactions [14]. Contractual governance can promote information sharing and hasten organizational responsiveness during a crisis. However, relying solely on contractual instruments to manage relationships can potentially heighten opportunism during the transaction process [15]. Therefore, relational governance is needed to provide functional supplement to the contractual governance mechanism [16]. Relational governance can coordinate the relationships of project participants, inhibit opportunism, guarantee timely allocation of resources, and change the perception and positioning of the organization [17]. Therefore, exploring the influencing mechanism of organizational resilience from contractual and relational governance perspectives becomes a key way to improve organizational resilience in infrastructure projects.

In the face of an unexpected crisis, project resilience requires the reallocation of its resources within the relevant organization [18]. Organizations need to continually adapt, modify, and reconfigure their capabilities to respond to a rapidly changing environment. In the crisis governance process, stakeholders should not only focus on short-term resource allocation capacity and traditional risk management objects (human, material, financial, and time), but also consider the long-term resource allocation system and organizational cognitive capacity of infrastructure projects from the perspective of governance [19,20]. As infrastructure projects continue to grow in complexity and size, static resource response strategies no longer fit the internal and external environment of complex large infrastructure projects, and instead seek more flexible stakeholder resource capabilities and cognitive capacity. In addition, through the construction and application of the contract and relationship governance mechanism among stakeholders, the resource mobilization ability and cognitive level of all parties in the project are promoted, thus improving the project’s ability to cope with a crisis. Therefore, in the face of a crisis, it is of great significance to explore the internal operating rules between governance means and crisis response performance from the perspective of resources and cognition to improve the organizational resilience of infrastructure projects.

Existing research on the resilience of infrastructure projects is relatively limited. Previous studies on organizational resilience of infrastructure projects are mainly limited to engineering safety and quality management perspectives, and lack exploration in project governance perspective. Therefore, to bridge these gaps, this study attempts to address two key questions from the perspective of resources and cognition:

Q1: What is the impact of project governance on organizational resilience?

Q2: How does project governance influence organizational resilience?

To address these issues, this study aims to empirically investigate the influence of contractual and relational governance on the organizational resilience of infrastructure projects from the perspectives of resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition. This study not only enriches the theoretical study of the impact of project governance on organizational resilience, but also deepens the intrinsic connection between project governance and organizational resilience from the perspective of resources and cognition. It provides effective theoretical guidance for crisis response and sustainable operation of infrastructure projects.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Organizational Resilience in Resource-Based Theory Perspective

Resource-based theory was first introduced by Wernerfelt [21] and has been used to explain differences in organizational performance due to resource heterogeneity in organizations. Resource-based theory provides a theoretical framework to explore the development of organizational adversity. When an organization faces adversity, it needs to provide unique resource capabilities in response to external changing situations, thus improving environmental resilience and creating new opportunities [22]. Resource-based theory emphasizes that only through unique resources and capabilities can it be ensured that firms can be effectively competitive in the face of crises. And it is valuable and difficult to imitate resources that can have an effective competitive advantage when an organization is facing a difficult situation [23]. In addition, when an organization faces a crisis, it should also make use of its unique ability to coordinate and integrate general resources to ensure that resources are deployed appropriately and effectively, so as to ensure the organizational resilience in improving resource utilization [24].

Due to the high resource heterogeneity among construction project organizations, resource-based theory is equally valued in the field of project management. As a temporary organization, a construction project is essentially a vehicle for project stakeholders to invest resources in order to obtain benefits. From the perspective of resource-based theory, all parties need to invest as much quality resources as possible to ensure that the expected goals of construction projects can be achieved. Moreover, scheduling and coordination capabilities of resources can maintain inter-organizational cooperation and ensure project stability [25]. The ability of organizations to act on certain goals during adverse events depends on the diversity and coordination of resources [19]. Therefore, the human, financial, and technological resources of an organization can create a competitive advantage during a crisis, thus helping the organization to turn the crisis around. Excellent human resource structure has faster response time and better collaboration ability, which helps to enhance organizational resilience [26,27,28]. In addition, resource coordination capabilities are mainly achieved through resource acquisition, integration, reorganization, and reconfiguration. Multiple participants and high asset specificity lead to a greater emphasis on resource allocation in the governance of construction projects, and cross-organizational coordination and resource scheduling increase the management burden. Therefore, the governance of construction projects also requires new explorations in responding to the crisis and improving organizational resilience through resource coordination tools such as resource integration and resource reconfiguration.

The ability involving resource reconfiguration is critical to organizational resilience [29,30,31]. Organizations need to continuously adapt, modify, and reconfigure their capabilities to develop new resources and capacities to respond to rapidly changing environments. Resource reconfiguration can help organizations cope with external disruptions and improve resilience [32]. Zhou [33] systematically combed the literature related to resource reconfiguration and identified the connotation of resource reconfiguration in three aspects. First, in essence, resource reconfiguration means breaking down and starting over. Second, in terms of the degree of change, resource reconfiguration emphasizes innovation and is high-intensity organizational learning. Third, from the perspective of integrating resources, resource reconfiguration is a continuous reallocation of resources by supplementing, removing, recombining, or redeploying resources [7]. Therefore, this study selects resource alignment, resource renewal, resource portfolio decomposition, and resource matching as key factors to measure the resource reconfiguration capability of construction projects based on resource-based theory.

2.2. Organizational Resilience in Cognitive Perspective

The organizational cognition view holds that the organizational cognition can affect the way the organization views the crisis, so as to respond to the crisis with a positive or negative attitude, and thus produce different organizational resilience. Organizational situational awareness stems from an individual’s or team’s cognition of a crisis situation. Zhu, et al. [34] stated that experience can change members’ cognition of crises and thus enhance organizational resilience. Positive psychological perceptions influence the organization’s goals, the efforts the organization seeks to achieve its goal comeback, the level of cooperation of the organization’s members, and the organization’s resilience in the face of adversity [35]. Organizations with excellent cognitive capabilities are able to develop strategies that are more adaptive to their development and perform better in both crisis management and post-crisis growth. Cognition in the organizational environment is no longer limited to the influence of psychological factors with the increasing scope of cognitive research, but becomes interested in the institutional environment of organizations, thus extending social cognitive theory and social norm theory.

In terms of social cognition, the way of organizations’ cognitive affects organizational risk perception, crisis response, and decision-making attitudes. The cognitive response of the organization’s own coping capacity is organizational effectiveness. Organizational effectiveness not only plays a role after an organization experiences a crisis, but also emphasizes the daily crisis response of the project and risk perception [36]. Organizational effectiveness reflects the way organizations view crises and their beliefs to deal with challenges, and efficient organizations have a better ability to deal with challenges [37]. Organizational resilience is built on the organization’s crisis response capability and the organization’s sense of mission and goals, so organizational effectiveness directly affects the improvement of organizational resilience and is a key factor in analyzing the organizational resilience of construction projects. In the crisis response of construction projects, organizational effectiveness has an impact on the organization’s observation and learning from competitors and collaborators, on the realization of the organization’s own sense of mission and competence, and on the absorption of successful experiences [38]. Organizational effectiveness determines how much effort construction projects invest in responding to crises and achieving project goals. The higher the organizational effectiveness, the greater the organizational resilience of construction projects bursting out in the face of adversity.

In addition, in terms of social norms, the organization’s cognition of the institutional environment includes organizational norms, organizational culture, and other aspects. The organizational culture of a project often varies greatly depending on the companies to which the participants belong, and it is difficult to accumulate the overall organizational culture of a project in a temporary organization. Therefore, it is no longer considered as an influential variable. Organizations with stronger constraint ability of organizational norms tend to be able to perceive and correctly handle crises in advance, which can better reflect the implementation effect of governance mechanisms, and are more suitable for the study of influencing factors of organizational resilience. Therefore, under the perspective of cognition, it is necessary to select organizational effectiveness and organizational norms as key factors to measure the organizational cognition and resilience of construction projects.

2.3. Governance in Construction Projects

Construction project governance is an institutional framework for the governance of the relationship between project stakeholders, reflecting the institutional arrangements of rights, responsibilities, and interests among all parties involved, and the completion of a complete construction project transaction under this framework. For the governance of construction projects, formal and non-formal institutions complement each other and are indispensable. The formal institution is a rigid constraint to the participants, which is mainly contractual governance with the contract as the core. The non-formal institution, on the other hand, imposes flexible constraints on participants through the relationship, which is mainly relational governance based on social relations or rules [17,39,40].

Contractual governance is to constrain the behavior of project stakeholders by means of a contract. Effective contracts serve as a framework for cooperation, both in terms of defining deliverables, stipulating appropriate behavior of the parties, and providing sanctions for contract violations, so they are considered one of the most effective governance mechanisms for maintaining cooperation [41,42]. Contractual governance in construction projects refers to the governance activities carried out for each participant in the project based on a formal contract or binding legal agreement during the implementation of the project. In the field of construction engineering, scholars have different views on the composition of the contract governance mechanism from different research perspectives and have not yet reached a consensus. Specifically, Quanji, et al. [41] explored the impact of contractual governance on construction contractor cooperation by dividing the dimensions of contract governance into control, coordination, and adaptation in the Chinese construction industry background. Wang, et al. [40] divided contractual governance into contract details, adaptability, and implementation measures to explore the positive impact of contractual governance on project performance. Yan and Zhang [14] decompose contractual governance into contract specificity, adaptability, and enforcement from a dynamic perspective. In summary, although most scholars differ in the division of contract governance dimensions from different perspectives, they all include the core elements of contract control, coordination, and adaptation. Therefore, this study will choose specificity of contract terms, contingency adaptability of the contract, and rigidness of contract implementation as the three dimensions of contractual governance.

Relational governance, also known as non-formal contractual governance, is a form of governance centered on the relationship between the parties involved in the transaction. Relational governance in construction projects refers to the governance activities in which all project participants use the relational norms with stakeholders to restrict their behavior in the process of project implementation. In the construction project industry, different scholars have different views on what constitutes the relational governance mechanism of an engineering project. Poppo and Zenger [43] argued that the dimensions of relational governance include the five dimensions of open communication, information sharing, trust, dependence, and cooperation. Mesquita, et al. [44] believed that relational governance consists of three basic elements, such as information sharing, mutual assistance, and reciprocity. Lu, et al. [17] classified relational governance into trust, relationship norms, information sharing, and flexibility. Yan, et al. [45] divided relationship governance into four dimensions of trust, communication, promise, and fairness based on public project governance theory. Fang [46] proposed trust, reciprocity, negotiation, and information sharing as four important dimensions of relationship governance in major engineering projects under the perspective of transaction cost. Therefore, combined with the dimensional division of relational governance by most scholars, this study will choose trust, promise, communication, and reciprocity as the four dimensions of measuring relational governance.

The existing studies on the relationship between contractual and relational governance have yielded mixed results and have not reached a consistent view. Many scholars have studied the interaction between the two in different situations and have reached different conclusions, which can be classified into three categories: alternative, complementary, and compound relationships. Scholars with the alternative view believed that contractual and relational governance have the same role and that they can replace each other [47,48]. On the contrary, scholars from the complementary viewpoint argued that both contractual and relational governance have their irreplaceable advantages and unavoidable disadvantages, and they complement each other [16,17]. With the gradual deepening of research on the project governance mechanism, some scholars have proposed that formal governance and non-formal governance should be used simultaneously, which not only requires the formal governance mechanism to serve as the basis for third-party constraints, but also takes into account the constraints imposed by non-formal norms between parties on their own behaviors. Therefore, the governance mechanism of construction projects should be hybrid, including both contractual governance and relational governance.

2.4. Organizational Resilience in Governance Perspective

Resilience derives from resilire and resilio, which mean bounce back or jump back in Latin. The concept of resilience was first developed in physics to measure the maximum pressure a material can withstand. In the early days, resilience emerged mainly in areas such as ecosystems and psychology. Holling [49] introduced resilience into the ecosystem field in 1973, and believed that resilience reflected the ability of the system to absorb changes and disturbances and still maintain the same state. In the field of psychology, resilience has been applied primarily to the study of how children cope with adversity. Over time, Meyer and Rowan [50] introduced resilience into the research field of organizational management, opening the door to research on organizational resilience.

Due to different research perspectives and disciplines, scholars have not yet formed authoritative explanations for the definition of organizational resilience, and there are different ways to express organizational resilience. Annarelli and Nonino [51] defined organizational resilience as a strategic awareness of an organization that is related to the way it manages to cope with shocks and can help it anticipate unexpected events. Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal [52] believed organizational resilience as the ability of organizations to predict and adapt to environmental changes. They argued that resilience is not a static attribute that an organization has or does not have, but rather a set of path-dependent potential capabilities that change as the organization evolves. Garg, et al. [53] considered that organizational resilience is the ability of an organization to cope with various crises and challenges, which can eliminate the negative external influences on an organization and help it adapt to the new environment. In the field of management, scholars’ understanding of organizational resilience is divided into static and dynamic views [54]. From a static view, organizational resilience should be regarded as a static capability or a dynamic process possessed by an organization, including its ability to predict and adjust the impact of environmental uncertainties under strong crisis leadership [55,56,57]. Static organizational resilience is one in which organizational members have good social network relationships, trust each other, and cooperate well to reduce organizational losses under adversity. At the same time, organizational resilience can also be dynamic, which is manifested in the ability to predict uncertain factors, respond quickly, recover quickly from crises, and even acquire the ability to learn and grow. At the same time, organizational resilience can also be dynamic, which is characterized by the ability to anticipate uncertainties, respond quickly, and recover quickly from crises or even gain the ability to learn and grow [27,51,58].

Organizational resilience is a multidimensional and multilevel concept. Currently, the application of organizational resilience in areas such as enterprise management, human resource management, and supply chain management from a governance perspective has received widespread attention. For instance, in the field of supply chain management, Wu, et al. [59] investigated the impact of contractual governance and relational governance on supply chain resilience, as well as the intermediary and moderating roles of supply chain collaboration and the institutional environment in the relationship between cross-organizational governance and supply chain resilience. In the field of human resource management, Mai, et al. [60] revealed the mediating role of team learning in the influence of entrepreneurial team relationship governance on organizational resilience based on a survey of 396 members of social entrepreneurial teams. In the field of enterprise management, Zhao and Li [61] employed the Pressure–State–Response (PSR) model, with the pandemic as the pressure, corporate governance and redundancy resources as the state, and corporate social responsibility performance as the response, to identify key factors affecting organizational resilience. The study found that corporate governance capability has a significant promoting effect on fostering organizational resilience under pandemic pressure, which can compensate for the organization’s deficiencies in resources and relationships. Table 1 presents a brief summary of the literature at the intersection of governance and organizational resilience. Organizational resilience has always been a focus in the field of organizational management research, and the number of studies on the resilience of infrastructure project organizations has also been increasing in recent years. However, research on the effect mechanism of infrastructure project organizational resilience from the perspective of project governance is considerably lacking. Therefore, this study explores the intrinsic relationship between project governance and organizational resilience, which to some extent enriches the related research on organizational resilience.

Table 1.

The brief summary of the literature at the intersection of governance and organizational resilience.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and Organizational Resilience

Project governance, whether through contractual or relational measures, requires a governance structure that supports collective action [69]. To achieve this collective action, it is necessary to push individual organizations through project governance mechanisms to give up their short-term interests in exchange for shared long-term interests and collaborative efforts [7]. Contractual governance can have an effect on the organizational resilience of construction projects through the construction of role systems and emergency procedures [70]. In detail, the establishment of a role system reflects a series of behaviors such as defining roles and assigning authority, specifying tasks and responsibilities, anticipating crises, and preparing solutions. Among them, defining roles and assigning authority is to determine the project stakeholders’ responsibilities and give them corresponding rights to respond to emergencies, which can effectively enhance the synergy among stakeholders. Specifying tasks and responsibilities involves attributes that define the coordination relationship between project stakeholders, which can better enhance the work distribution among project stakeholders. When a crisis occurs, stakeholders can follow the crisis response process agreed to in the contract, which helps accelerate the organization’s response to the crisis and effectively improve the organization’s resilience. Anticipating crises and preparing solutions is a contractual instrument that clearly defines possible uncertainty situations, which helps each participant to construct project goal expectations, develop crisis response plans in advance, and form proactive strategies.

Relational governance, on the other hand, affects organizational resilience of construction projects by coordinating relationships between roles, primarily through behaviors that promote mutual trust, commitment keeping, positive communication, and mutual aid and reciprocity. Trust is the premise for the establishment of relationship resilience. The breakdown of trust will lead to the breakdown of the relationship, which will affect the inter-organizational cooperation ability and reduce the project’s adaptability to a crisis [60]. When project parties build positive relationships based on trust and reciprocity, they can significantly improve the timeliness and accuracy of information sharing and enhance the identification of potential crises [71]. When a crisis strikes, relational resilience will unite organizations and members within organizations to form a strong cohesion and ensure that the project can overcome the difficulties together. Moreover, active communication and effective information exchange among project stakeholders can enable stakeholders to identify problems more quickly and form timely response plans, because organizational resilience relies on a rapid response mechanism [72]. In summary, the relational governance mechanism can facilitate participant communication, contribute to the prevention of uncertainty, and improve the organization’s ability to anticipate crises. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses among contractual governance, relational governance, and organizational resilience:

H1.

Contractual governance is positively associated with organizational resilience.

H2.

Relational governance is positively associated with organizational resilience.

3.2. Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and Resource Reconfiguration

With the deepening professional division of labor among construction project participants, resource allocation has become a key challenge for engineering projects to cope with the crisis, and maintain stable and sustainable operation. In the crisis governance process, it is required not only to focus on the short time resource allocation capacity and traditional risk management objects such as people, money, materials, and time, but also to introduce a governance perspective to analyze the long-term resource allocation system of construction projects. Both contractual and relational governance mechanisms can increase the scheduling and coordination of resources between organizations and facilitate the generation of new resources [73]. In the face of frequent changes in the internal and external environment of construction projects, stakeholders coordinate resources through contractual and relational governance mechanisms, improving the source reconstruction capacity of each stakeholder. It can provide the best combination of resource allocation for the participants, and thus improve the crisis response effectiveness. Resource reconfiguration capability includes resource alignment, resource matching, portfolio decomposition of resources, and resource renewal, the level of which is mainly influenced by the resource coordination process and willingness to allocate resources [70].

Contractual governance mechanisms influence resource reconfiguration through the resource coordination process. In the temporary organization of construction projects, stakeholders have valuable resources that they want from each other, and these resources can be called on by the organization when a crisis occurs. Stakeholders need to agree on resources in contracts to prevent opportunistic behavior and thus reduce impediments in resource mobilization [17]. Contracts not only give a legal basis for stakeholders’ resource mobilization actions, but also provide guidelines for supplementing, deleting, and reorganizing their resources in response to changes [7]. In addition, when the resource coordination process needs to be reconstructed in a crisis, contractual governance can ensure the legitimacy of the resource coordination process by influencing the allocation of rights and reward and punishment mechanisms. On the other hand, the relational governance mechanism influences resource reconfiguration by increasing the willingness to reallocate resources. Relational governance contributes to the stability of inter-organizational cooperative relationships and can increase the degree of cooperation of participants in the resource coordination process [74]. When a construction project faces a crisis, the original resource allocation pattern may no longer be adapted to the crisis, and resources need to be continuously added, removed, and recombined to accommodate the changes in the project. The trust and commitment to the project among the participants provide a basis for legitimacy in the resource reconfiguration of the project, enabling rapid access and matching of resources and activities to deal with unexpected events. In addition, active communication across organizations in construction projects can facilitate the flow and sharing of resources, allowing the advantages brought by the heterogeneity of resources to be brought into full play. At this point, it is necessary to achieve timely communication of important information among stakeholders through technical means, break organizational boundaries, and promote resource reconfiguration among different stakeholders [75]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses among contractual governance, relational governance, and resource reconfiguration:

H3.

Contractual governance is positively associated with resource reconfiguration.

H4.

Relational governance is positively associated with resource reconfiguration.

3.3. Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and Organizational Cognition

Based on the cognitive perspective, this study will explore the relationship between contractual governance, relational governance, and organizational cognition from the three aspects. In construction projects, contractual governance affects organizational effectiveness through the specificity of contract terms, contingency adaptability of the contract, and rigidness of contract implementation. The specificity of the contract terms ensures project oversight processes and project responsibilities, and thus improves organizational capacity. The adaptability in the contract provides organizations with solutions when dealing with challenges, and dealing with challenges is an important dimension of organizational effectiveness. The rigidness of contract implementation can prevent the occurrence of crises well [41,76,77]. For example, opportunistic behavior is prevented through compensation and accountability mechanisms, which provide for the benefit needs of the participants. Similarly, the positive effect of relational governance on organizational effectiveness has been confirmed. Yan and Zhang [14] argued that trust could improve project management performance of cost, quality, and schedule and meet the benefit demand of organizational effectiveness. Trust can also increase personnel cooperation, strengthen team performance, enhance synergy, and enhance organizational ability. Since engineering projects are temporary organizations, the diversity of participants will lead to difficulties in collaboration between participants, and the differences in norms and systems will also lead to project complexity and uncertainty [78]. Contractual and relational governance will discipline and coordinate the behavior of each participant in the project implementation process through the institutional environment and relational regulation capabilities. Contractual governance, which sets out the rights and obligations of the parties through formal contracts or other binding agreements, increases the normative pressure on contracting parties and enhances the constraining force of organizational norms. The mechanism of influence of relational governance on organizational norms is realized by strengthening normative identification. Zhao, et al. [15] argued that networks constructed by relational governance can enhance the normative identity of participants, and that relational networks based on reciprocity and trust can reinforce normative beliefs and avoid opportunistic behavior. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses among contractual governance, relational governance, and organizational cognition.

H5.

Contractual governance is positively associated with organizational cognition.

H6.

Relational governance is positively associated with organizational cognition.

3.4. Resource Reconfiguration and Organizational Resilience

In the resource-based view perspective, the ability of an organization to manage and reconfigure resources will be reflected according to environmental changes [79,80]. These abilities are crucial for the survival and development of an organization, and can even improve the performance of an organization. In construction projects, resource structure is often unable to be effectively used when dealing with risks. In case of a serious crisis, the organization may lose the ability to cope with environmental changes, resulting in project interruption, cooperation failure, and even adverse effects [81]. The more intense the perceived crisis, the more resources and energy are required to support the organizational response. Only then can the crisis be alleviated or even resolved. Construction projects have complex stakeholders, and resource reconfiguration can effectively integrate resources to cope with the impact of risks, thus strengthening organizational resilience for risk management. The resources of construction projects are diverse, numerous, and complex. In the face of internal and external disadvantages, project organizations can coordinate, renew, reconfigure, and realign existing resources to enhance the flexibility of organizational resource allocation and thus improve organizational resilience [30,32]. Therefore, the strengthening of resource reconfiguration of construction project organizations can help project organizations to have the ability of rapid learning and continuous change, so that project organizations can constantly adjust and optimize resources in the dynamic changing environment, and thus enhance the organizational resilience of construction projects. In addition, changing the existing resource pattern, updating the resource pool, and optimizing the resource allocation can further enhance the purpose of the reconfiguration function, which has a significant effect on the improvement of organizational resilience [30,51,82]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses among contractual governance, relational governance, resource reconfiguration, and organizational resilience:

H7.

Resource reconfiguration is positively associated with organizational resilience.

H7a.

Resource reconfiguration plays a mediating role in the relationship between contractual governance and organizational resilience.

H7b.

Resource reconfiguration plays a mediating role in the influence of relational governance on organizational resilience.

3.5. Organizational Cognition and Organizational Resilience

Based on the previous analysis of organizational resilience from the perspective of cognition, this study explores the influence of organizational cognition on organizational resilience from the perspective of organizational effectiveness and organizational norms. Organizational effectiveness is the common belief of an organizational member about the organization’s decisions, executive actions, and ability to achieve organizational goals. Organizational effectiveness affects an organization’s sense of mission and goals, and determines the way an organization views a crisis [83]. Organizational effectiveness reflects the psychological perceptions of the participants in the organization. Participants in projects with high organizational effectiveness tend to have higher morale, enthusiasm for work, and a better communication climate. Highly effective organizations tend to have a more specialized division of labor, more detailed action plans, and a greater capacity for learning. In detail, the specialized division of labor helps to enhance the organization’s perception of a crisis, and quickly find the root cause of the crisis for targeted adjustment. The detailed action plan helps the organization to respond quickly when faced with a crisis [5]. Greater learning capability refers to the various actions that organizations take around information and knowledge skills in order to achieve their development goals and improve their core competencies. It is also the process by which organizations continuously strive to change or redesign themselves to adapt to a continuously changing environment [84]. In the process of construction projects, learning ability can help organizations acquire new technologies to meet with high-standard technical requirements when projects face crises [85,86]. On the other hand, organizational norms are the guidelines that unify and regulate the behavior of organizational members and thus maintain the orderly operation of the organization. The stronger the effective constraining force of organizational norms on members, the stronger the organizational cohesion and the stronger the synergy. Organizational norms have an impact on the behavior of the organization through their constraining effect. Zhou [5] showed that the constraining force of organizational norms can enhance project resilience and reduces project complexity. To sum up, this study proposes the following hypotheses between organizational cognition and organizational resilience:

H8.

Organizational cognition is positively associated with organizational resilience.

H8a.

Organizational cognition plays a mediating role in the relationship between contractual governance and organizational resilience.

H8b.

Organizational cognition plays a mediating role in the influence of relational governance on organizational resilience.

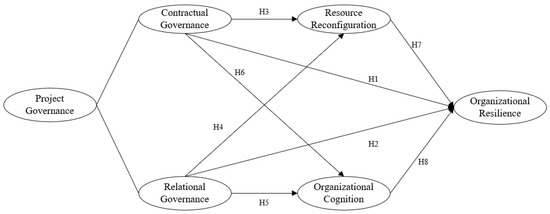

Based on the above hypotheses, the theoretical model constructed in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model and hypotheses.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

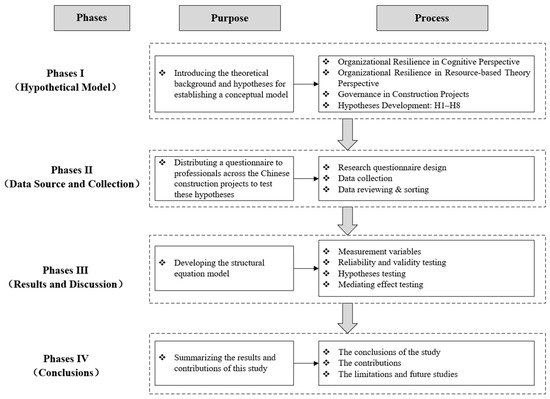

The methodology followed in this study involves four main phases, as shown in Figure 2. In the first phase, the theoretical background and hypotheses development were described in the preceding section. Specifically, the theoretical background includes three parts, organizational resilience in the cognitive perspective, organizational resilience in the resource-based theory perspective, and governance in construction projects. The hypotheses development mainly focuses on the relationship between five variables: contractual governance, relational governance, resource reconfiguration, organizational cognition, and organizational resilience. Finally, the conceptual model was constructed by introducing these two parts. In the second phase, this part mainly introduces data sources and collection, including questionnaire design, data collection, data sorting, and sample description. The survey subjects of this study were selected from the participants in the infrastructure projects, who not only have first-hand knowledge and information about technological innovation, but also are familiar with the operation and governance of relevant infrastructure projects. In the third phase, the collected data are mainly analyzed and discussed. The main purpose of this section is to verify the conceptual model using the Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method. The PLS-SEM is a statistical technique used in research to analyze relationships between observed variables and latent constructs. The process includes measurement variables, reliability and validity testing, hypothesis testing, and intermediate effect testing. In the last phase, the conclusions, contributions, limitations, and future research directions of this study are summarized.

Figure 2.

The overall process of this study.

The methodology employed in this study exhibits strong replicability and applicability, rendering it applicable in research conducted in other countries. This is attributed to our deliberate consideration of universality and adaptability during the design phase, allowing it to accommodate diverse cultural, social, and geographical contexts. For instance, the research methodology we employed is not contingent upon specific regional or cultural conditions. Furthermore, we emphasize transparency and reproducibility in the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. This signifies that research teams in other countries can implement our methodology steps and obtain comparable results in their own studies.

4.2. Data Source and Collection

To test these hypotheses, this study administered a survey to professionals involved in construction projects in China. Given the vast expanse and diverse geographical and cultural contexts of the country, this study ensured the universality of our data by distributing the questionnaire to participants from various regions and categories of infrastructure projects. The respondents of the survey were personnel from owners to contractors involved in infrastructure projects. To enhance the quality and efficiency of data collection, the questionnaire was primarily administered in electronic format. A non-probabilistic sampling method was employed during data collection, which took place between June and December of 2022. Finally, a total of 534 questionnaires were distributed in this study, and 519 valid questionnaires were collected after targeted screening for missing information, incompatibility with research needs, and polarized responses. The questionnaire consisted of two main parts. The first part provided basic descriptions of the respondents, including gender, age, education, work experience, and industry type. The second part provides the required questions for the study variables, including contractual governance (10 questions), relationship governance (12 questions), resource restructuring (4 questions), organizational cognition (7 questions), and organizational resilience (5 questions). The questionnaire value is 13 times that of 38 variable items, which exceeds the threshold standard proposed by Hair, et al. [87] that the statistical power is 10 times the number of variable items.

The final sample collected in this study consisted of 338 male respondents, accounting for 65.1%, and 181 female respondents, accounting for 34.9%. The gap between men and women is relatively obvious, with significantly more men than women, which is related to the characteristics of the study topic. According to the age distribution, 30–35 years old (237 persons, 45.7%) accounted for the largest proportion of all respondents, followed by 35–40 years old (193 persons, 37.2%). This is consistent with the distribution characteristics of working years of 5–10 years (195 persons, 37.6%), followed by 10–15 years (132 persons, 25.4%), which reflects the good quality of the samples to a certain extent. In terms of education level, the number of people with a bachelor’s degree (323 persons, 62.2%) is the highest, while the number of people with a master’s degree (135 persons, 26.0%) and college education or less (61 persons, 11.8%) is more balanced, which also indicates that the respondents have good quality. This study also counts the industry types, mainly water conservancy and hydropower projects (156 projects, 30%), road and bridge engineering projects (113 projects, 22%), building projects (126 projects, 24%), and transportation projects (124 projects, 24%). The distribution of engineering types is relatively even, reflecting the universality of sample coverage. The comprehensive situation shows that the respondents have good experience in construction projects, which can ensure the quality of the questionnaire and improve the reliability of the sample.

4.3. Measurement

To measure all the variables, this study relied upon extant literature to develop multi-item scales (as is shown in Appendix A). In order to further improve the questionnaire design, a pilot study was conducted to identify errors in expression and prevent ambiguity. Respondents were rated on a 5-point Likert scale based on a completed construction project they deeply participated in (1—strongly disagree; 2—disagree; 3—neutral; 4—agree; 5—strongly agree). The details are explained below.

4.3.1. Contractual Governance

This study constructed multi-item scales for contractual governance in three variables, specificity of contract terms, contingency adaptability of the contract, and rigidness of contract implementation. The scale settings can be found in Quanji, et al. [41], Zhang [88], Lee, et al. [77], Ba, et al. [76], Lu and Xu [89], and Ning [90]. Among them, items SCT1–SCT4 measure specificity of contract terms, items CAC1–CAC3 measure contingency adaptability of the contract, and items RCI1–RCI3 measure rigidness of contract implementation. The specific measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

4.3.2. Relational Governance

The variables of relational governance include trust, promise, communication, and reciprocity. The scale settings for measuring the four variables in contract governance can be found in Zhan, et al. [91]; Xue, et al. [92]; Dong, et al. [93]; Yen, et al. [94]; and Chu, et al. [95]. The first variable trust is measured with four items, Trust1–Trust3. The second variable promise is measured with four items, Promise1–Promise3. The third variable communication is measured with four items, COMM1–COMM3. The fourth variable reciprocity is measured with four items, RECI1–RECI3. The specific measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

4.3.3. Resource Reconfiguration

The scale of resource reconfiguration is a single-dimension, four-item measurement scale. The four items RR1–RR4 from Zhou [5]; Wang [70]; and Wang, et al. [7] in measuring resource reconfiguration are for our reference. The specific measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

4.3.4. Organizational Cognition

The variables of organizational cognition include organizational effectiveness and organizational norms. The two variables from Zhou [5] in measuring contracts are for our reference. Among them, items OE1–OE4 measure organizational effectiveness, and items ON1–ON3 measure organizational norms. The specific measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

4.3.5. Organizational Resilience

The scale of organizational resilience is a single-dimension, four-item measurement scale. The four items OR1–OR5 from Wang [70] in measuring organizational resilience are for our reference. The specific measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

4.3.6. Control Variables

This study incorporated two control variables related to organizational resilience to minimize issues related to omitted variable bias [96]. These control variables are associated with the characteristics of the subjects. This study controls for the subject’s working year. The longer the working year of the subjects, the more they understand infrastructure projects, and the more accurate their understanding of project organizational resilience. This study controls for the subject’s industry type. Projects from diverse industries exhibit distinct characteristics when facing crises and resource dynamics. Therefore, this study incorporates control variables (working years, industry types) into the model. Hence, this study incorporates two control variables, working year and industry type, into the model.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

The reliability and validity tests are to check the degree of truth and accuracy of the sample data for the reflection of the variables. In terms of reliability, this study calculated Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity test for a variable scale using SPSS 25.0 software, and the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the scale was also tested to determine the reliability of the questionnaire. In terms of validity, the convergence validity and discriminative validity were determined with Smart PLS 3.0 software to test the validity of the results.

First, we conducted a common method deviation test. Harman’s one-factor test was conducted to test for common method bias according to Podsakoff, et al. [97]. The cumulative variance explained with the data in this study was 70.844%, which is greater than the threshold value of 60%. The first factor explains 24.698% of the total variance, which is less than 40%. These results indicate that there is no serious common method bias and the homogeneous variance of the data is within an acceptable range. Second, we conducted a reliability test of questionnaire data. The overall KMO value was 0.845, and the Bartlett test statistic was significant at less than the 0.001% level. As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of CG, RG, RR, OC, and OR variables range from 0.717 to 0.987. The reliability coefficients of these variables were all greater than 0.7, indicating high internal consistency of the questionnaire data. In addition, the convergent validity is usually determined with composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values. The results are shown in Table 3, where CR is greater than 0.7 and AVE is greater than 0.5. The results show that the measurement model has good convergent validity. Finally, discriminant validity indicates that there are obvious differences among different variables; that is, indicators can effectively distinguish different variables. As shown in Table 3, all the variables were significantly correlated with each other, and the absolute values of the correlation coefficients are the square root of the corresponding AVE. The results indicate that the latent variables are correlated and distinguished from each other, which means that the discriminant validity of the scale data is ideal.

Table 2.

The reliability and validity test of the measurement model.

Table 3.

The values of discriminant validity.

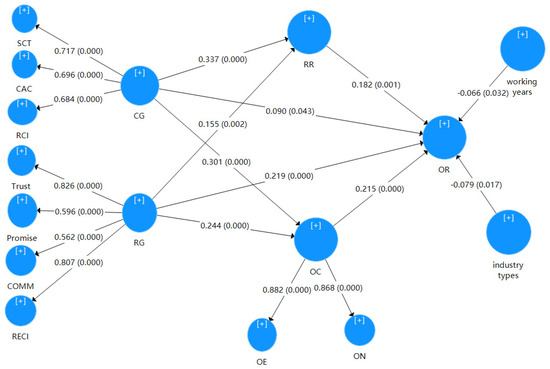

5.2. Hypotheses Testing

To test these hypotheses, this study performed a full model test though Smart PLS software. In this study, the intrinsic relationships among the latent variables were analyzed by calculating parameters such as standardized path coefficients, t-values, and p-values. As shown in Figure 3, the standardized path coefficient, its significance (p-value), and the explained variance (R2) of variables are displayed. The standardized path coefficient of the model is used to test the hypothesis between the latent variables. The standardized path coefficients range from −1 to +1, indicating the positive and negative relationships between latent variables and the strength of the effects.

Figure 3.

The PLS model results.

As shown in Table 4, the path coefficient of CG on OR is 0.099 (T = 2.021, p < 0.05), so the hypothesis H1 is supported and CG has a positive effect on OR. This indicates that contract governance, as a formal system within the temporary organization of a project, can restrict or motivate participants to take on different behaviors through the distribution of rights and responsibilities, and reward and punishment mechanisms, which is conducive to improving the crisis handling ability of construction projects. These findings are in line with previous studies by Lu, et al. [17] and Yan and Zhang [14]. The path coefficient of RG on OR is 0.220 (T = 3.636, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H2 is supported and RG has a positive effect on OR. Relational governance improves the efficiency of collaborative action among project participants through trust and reciprocity mechanisms, which contributes to the rapid adaptation of organizations in a crisis and the realization of post-crisis project objectives. Commitment in relationship governance reflects the participants’ stable expectations for future cooperation and provides a guarantee for the realization of project objectives. This is in line with Poppo and Zenger [43], who found that relationship governance facilitates communication, decision making, and coordinated response to emergencies among all parties involved, enhancing the organization’s ability to respond and adapt to crises.

Table 4.

Path coefficients and hypothesis testing results.

The path coefficient of CG on RR is 0.337 (T = 6.372, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H3 is supported and CG has a positive effect on RR. The path coefficient of RG on RR is 0.155 (T = 2.850, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H4 is supported and RG has a positive effect on RR. Contractual governance can provide a basis for resource reconfiguration activities by constraining the behavior of participants in a crisis, and it can also ensure the interest claims of participants and provide assurance for resource scheduling and renewal activities. Hypothesis H3 was verified, indicating that contractual governance enables prearrangement of resource activities and improves project crisis response. The contractual governance facilitates the allocation, utilization, transformation, and renewal of organizational resources. This is similar to the view of Zhou [5]. Hypothesis H4 was verified, showing that relational governance reduces relationship risk and communication costs for resource reconfiguration and increases the willingness to reallocate resources. This is consistent with findings of Wang, et al. [7].

The path coefficient of CG on OC is 0.300 (T = 5.542, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H5 is supported and CG has a positive effect on OC. The path coefficient of RG on OC is 0.244 (T = 3.625, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H6 is supported and RG has a positive effect on OC. These findings suggest that contractual governance can influence organizational effectiveness by affecting the perceptions and behaviors of the participants. Contractual governance can have a constraining effect on participant behavior, which helps to meet the interest needs of the participants and increases organizational capacity. Moreover, relational governance enhances inter-team cooperation, reduces inter-organizational coordination costs, and provides greater cohesiveness to the project. It alleviates the conflict of interest between participants and contributes to the improvement of organizational cognition.

The path coefficient of RR on OR is 0.183 (T = 3.182, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H7 is supported and RR has a positive effect on OR. Many studies have demonstrated the positive effect of resource reconfiguration on organizational resilience [5,7,70]. Resource reconfiguration promotes the effective allocation of organizational resources, creating a competitive advantage for the project and helping it to remain stable and achieve its goals in a crisis. The path coefficient of OC on OR is 0.216 (T = 3.692, p < 0.01), so the hypothesis H8 is supported and OC has a positive effect on OR. Organizational effectiveness and organizational norms in organizational cognition are critical to enhance organizational resilience in project contexts. Highly organizational effectiveness can build a good learning climate, have stronger organizational and management capabilities, and improve organizational crisis awareness. Highly organizational effectiveness can provide organizations with a more positive crisis response mindset, which facilitates organizations to face and respond to challenges and turn them into opportunities. Therefore, organizational cognition has a significant effect on organizational resilience. In summary, hypotheses HI, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H8 were tested and the relationships were all significant, which provides the basis for further testing of the mediating hypotheses.

5.3. Mediating Effect Testing

This study also explored the mediating effect of resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition in the relationship between the effects of project governance and organizational resilience, i.e., H7a, H7b, H8a, and H8b. To verify whether the mediating effect is significant, this study performed 5000 sampling rounds at the 95% confidence level with the bootstrapping method in PLS-SEM. The 95% bootstrap confidence interval does not contain 0, indicating the existence of a mediating effect; otherwise, it does not exist. The results of the mediating effect calculation are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of mediation effect analysis.

The data analysis results show that the path (CG→RR→OR) 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, indicating that the mediating effect of resource reconfiguration is significant in the relationship between contractual governance and organizational resilience; that is, hypothesis H7a is supported. The uncertainty of the impact and type of crisis requires resources to be reconfigured and structured as needed. Contractual governance can enhance the organizational resilience of engineering projects by structuring the resource mobilization structure and forming reactive resource response ability [7]. The path (CG→OC→OR) 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, indicating that the mediating effect of organizational cognition is significant in the relationship between contractual governance and organizational resilience; that is, hypothesis H8a is supported. In the context of construction projects, there are few studies on organizational cognition as a mediating factor between contractual governance and organizational resilience. However, studies have demonstrated that contractual governance in firms can improve team members’ role perceptions, enhance members’ motivation and productivity, and thus improve organizational crisis response ability [98].

The path (RG→RR→OR) 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, indicating that relational governance can influence the level of organizational resilience by influencing resource reconfiguration; that is, hypothesis H7b is supported. This is in line with Robson, et al. [99], who found that trusting relationships of alliance partners help develop resource complementarity, which facilitates resource reconfiguration activities in a crisis and ultimately translates into motivation to achieve performance goals. In the context of construction projects, reciprocity and trust build a good team climate and communication environment that facilitates the rapid combination and efficient allocation of resources, which helps organizations in a crisis to react quickly and adapt to new changes. The path (RG→OC→OR) 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, proving that relational governance can influence organizational effectiveness and organizational norms from the cognitive perspective, thus improving organizational resilience. H8b is supported. Relational governance helps communication between participants in the collaborative process, and facilitates decision making and command work in a crisis. In terms of cognition, it promotes the perception and exchange of each other’s team status, and forms a more complementary crisis response ability.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Organizational resilience has been the focus of research in the field of organizational management, and the number of studies on organizational resilience of infrastructure projects has been increasing in recent years. However, there is a considerable lack of research on the mechanisms influencing organizational resilience in infrastructure projects under the project governance perspective. Therefore, this study explored the influencing factors of organizational resilience in infrastructure projects, and established and validated the relationship mechanisms among contractual governance, relational governance, and organizational resilience in order to fill the gaps of existing studies. First, from the perspective of resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition, this paper constructed the mechanism model of contractual and relational governance affecting the organizational resilience of infrastructure projects. Then, based on the constructed conceptual model, this study collected 519 sample data values by determining variable measurement, questionnaire design, and data collection. Finally, PLS-SEM and bootstrap testing techniques were applied to empirically test the research hypotheses and influence paths, and the results were discussed and analyzed.

The results of the study showed that contractual and relational governance can increase the level of organizational resilience. First, there is a direct effect between project governance and organizational resilience, and both relationship governance and contractual governance can directly affect the level of organizational resilience. Second, resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition play a mediating role in the relationship between contractual governance and organizational resilience. Among them, the mediating role of organizational cognition is greater than that of resource reconfiguration. Finally, resource reconfiguration and organizational cognition also play a mediating role in the relationship between relational governance and organizational resilience, where the mediating role of organizational cognition is greater than that of resource reconfiguration.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Crisis response and risk prevention for infrastructure projects is a significant topic in the field of project management. Organizational resilience, a critical dynamic capability addressing uncertainty and complexity, can effectively enhance the success rate and performance of infrastructure projects. Contractual governance, as a formal governance mechanism, can regulate the behaviors of participants effectively through incentive mechanisms and distribution of rights and responsibilities. Relational governance, as an informal governance mechanism, can efficiently coordinate the interests of all participants, resolve conflicts, and aid in crisis management. Through a theoretical analysis and practical investigation, this study provides the following managerial implication insights.

Firstly, establishing a multi-party agreement and cooperative atmosphere will reinforce the collective response to crises. This study suggests that contracts or agreements be signed with multiple stakeholders, specifying the basic responsibilities of participants. Particularly concerning potential future risks, it is crucial to clarify the distribution of rights, responsibilities, and benefits among all parties, alongside the collective crisis response measures in advance. Incentives and penalties can be established within these contracts to create collective constraints for stakeholders. Moreover, all parties involved in the project should foster mutual trust, enhance communication, and build a consensus culture. Through increasing risk awareness, arranging emergency drills, and enhancing safety consciousness, stakeholders can foster a consensus on crisis management. This will enable them to swiftly identify risks in everyday circumstances, rapidly adapt during crisis situations, and promptly recover functionality from crises.

Secondly, the importance of resource reconfiguration capabilities should be highlighted to enhance crisis response ability. Project managers of infrastructure projects need to realize the substantial impact of resource reconfiguration on organizational resilience. Facing resource issues within the infrastructure project organization, managers should effectively undertake the adjustment and renewal of resources, emphasizing the control of resources within the project organization. An effective integration of various resources should be carried out, along with reasonable storage and allocation, aiming at swiftly supplementing relevant resources when major construction projects encounter crises. This ensures the supply of resources and prevents infrastructure projects from suffering losses due to resource issues.

Lastly, there should be an emphasis on enhancing organizational effectiveness and organizational norms. Project managers of infrastructure projects must understand the potent role of enhanced organizational cognition in promoting organizational resilience. By undertaking specific measures, managers can augment the recognition of the project organization among all participants, effectively enhancing the organization’s resilience toward unforeseen circumstances. For example, the establishment of unambiguous reward and punishment mechanisms and the construction of open communication channels and feedback systems can diminish the uncertainty among various stakeholders, fostering their desire for self-improvement. The implementation of equitable risk allocation allows their participation in the distribution process, and the setting of clear project objectives provides a common foundation for the organization to strive toward project goals.

6.3. Contributions and Limitations

This paper makes three contributions. Firstly, this study opens up new research directions and ideas for the study of organizational resilience in infrastructure projects. This paper explores the influencing factors of organizational resilience in the context of infrastructure projects, which is of great significance for promoting the study of governance theory and resilience in infrastructure projects. Secondly, the organizational resilience of infrastructure projects is studied in depth from the perspective of governance, which realizes the leap from relational contract theory to organizational resilience theory and enriches the existing research in the field of organizational resilience. Finally, this study integrates different theoretical perspectives of organizational resilience research, which makes up for the shortcomings of single theoretical research and disconnection from reality, and is conducive to the enhancement of organizational resilience and improvement of governance mechanisms of infrastructure projects.

While this study makes the above-mentioned contributions, several limitations and future research opportunities should be emphasized. Organizational resilience of infrastructure projects is a dynamic capability of an organization, which will constantly change with the project environment during the crisis, and the governance of infrastructure projects will also change dynamically over time. Therefore, a future study can try to collect panel data through multiple time periods to achieve a deeper understanding of organizational resilience in infrastructure projects. Additionally, this study did not specifically categorize and discuss stakeholders based on different types and levels of involvement. This may lead to variations in the effectiveness of contract governance or relationship governance mechanisms for specific types of stakeholders. Future research could conduct in-depth case analyses focused on specific types of stakeholders, further exploring the impact relationship between the resilience level of a particular stakeholder within the project organization and the overall resilience level of the project organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; Methodology, C.C.; Writing—original draft, L.L.; Writing—review & editing, C.C. and Z.W.; Supervision, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities grant number B230205050, the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province grant number KYCX22_0683 And the APC was funded by L.L.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to its complexity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Items

- (1)

- Contractual governance (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9458)

- Specificity of contract terms (four items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.8903)

- SCT1

- The contract terms clearly describe the responsibilities of both parties.

- SCT2

- The contract terms clearly express the specifications and standards to be met by the project.

- SCT3

- The contract terms describe the detailed rules and regulations of the project quality inspection clearly and unambiguously.

- SCT4

- The contract terms clearly describe the risks assumed by both parties.

- Contingency adaptability of contract (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.8695)

- CAC1

- The contract has a complete response mechanism for unforeseen events.

- CAC2

- The contract has a sound implementation procedure for engineering changes.

- CAC3

- The contract has a specific procedure for resolving disputes and conflicts.

- Rigidness of contract implementation (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.8643)

- CRI1

- The owner will periodically review the implementation of the project in accordance with contract terms.

- CRI2

- Both parties follow the contractual procedures exactly.

- CRI3

- The standard of contract execution is strictly unified, and the defaulting party will be severely punished by law and economy.

- (2)

- Relational governance (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9496)

- Trust (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- Trust 1

- We believe that all the participants in the construction project can meet the requirements of the contract in terms of technology and management.

- Trust 2

- We believe that the technical knowledge shared by all participants in the construction project can promote the better completion of the project.

- Trust 3

- The trust among the participants in the construction project facilitates the sharing of skills and experience among the employees.

- Promise (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- Promise 1

- The project construction participants will strictly abide by the verbal commitments made.

- Promise 2

- The project construction participants will strictly fulfill the series of contracts signed and invest a lot of energy and resources into the project.

- Promise 3

- We value our relationship with other project participants and promise not to do harm to each other.

- Communication (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- COMM 1

- In the process of project implementation, the communication between the project construction participants is frequent.

- COMM 2

- We will have meetings to discuss problems in the project, learn from each other, and share experiences.

- COMM 3

- Differences between the participants in the construction of the project are mainly resolved through communication.

- Reciprocity (two items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- RECI 1

- We are able to actively return the help of other project members during the implementation of the project.

- RECI 2

- We may feel disgusted with members who are self-interested or lack teamwork spirit.

- RECI 3

- We are willing to help the project achieve greater benefits with less sacrifice.

- (3)

- Resource reconfiguration (four items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9496)

- RR1

- Our project changes the order of resource use in response to environmental changes.

- RR2

- Our projects rematch resources and work content in response to changes in the environment.

- RR3

- Our projects break down and recombine existing resources in response to changing circumstances.

- RR4

- Our projects absorb new resources in response to changing business circumstances.

- (4)

- Organizational cognition (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9496)

- Organizational effectiveness (four items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- OE1

- Compared to other projects, our project has a stronger organizational capability.

- OE2

- Compared to our competitors, our project has a clear strategic advantage.

- OE3

- Our program will achieve higher performance for the benefit of other parties involved.

- OE4

- We are able to handle challenging tasks that arise during the course of a project.

- Organizational norms (three items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.9383)

- ON1

- The parties involved in a project usually fit in easily with each other.

- ON2

- When unforeseen circumstances arise, there is usually agreement among the project participants.

- ON3

- Participants in a project usually agree with the decisions of other members.

- (5)

- Organizational resilience (five items, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.8482)

- OR1

- We have the ability to deal with a crisis.

- OR2

- We are able to adapt easily to crisis events.

- OR3

- We are able to respond to crisis events very quickly.

- OR4

- We are able to stay alert to changes in our environment.

- OR5

- After the crisis, we were able to get back to business as usual quickly.

References

- Flyvbjerg, B. What You Should Know About Megaprojects and Why: An Overview. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Hertogh, M.; Bosch-Rekveldt, M.; Zhu, J.; Sheng, Z. Exploring Decision-Making Complexity in Major Infrastructure Projects: A Case Study From China. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 51, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcar Dunovic, I.; Radujkovic, M.; Vukomanovic, M. Internal and external risk based assessment and evaluation for the large infrastructure projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2016, 22, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, L.M.; Nabawy, M. Identifying key risks in infrastructure projects—Case study of Cairo Festival City project in Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2019, 10, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y. The Influence Mechanism of Organizational Resilience of Major Construction Projects Based on Dual Governance Perspective; Shandong Construction University: Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]