Testing Olmsted’s Lasting Legacy—Comparing Design Theory and the Post-Occupancy Conditions of New York Central Park

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How did Olmsted envision the landscape elements, activities, and tourists’ perceptions in the park?

- What landscape elements will the current users prefer, what activities are they more willing to participate in, and what perceptions will they have of the landscape site?

- What is the relationship between the landscape elements focused on by the tourists, the activities there in and the perceptions of the site?

- What lessons can we learn by comparing Olmsted’s original theory and the current usage pattern of Central Park?

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Olmsted’s Design Theory Extraction from Literature

- The first source is Frederick Law Olmsted: Essential Texts, which was purchased by one of the authors on the AbeBooks website (http://abebooks.com/ accessed on 12 January 2021.). This book mainly collects 16 essays by Olmsted from the 1950s to the 1990s, revealing his thoughts on cities, residential sites, and the history and theory of urban parks. Most of Olmsted’s design theories cited in this study are derived from this book.

- The second document source is the official website of New York Central Park (https://www.centralparknyc.org/ accessed on 20 June 2022), which contains the historical records of the park, the description of the current uses of the park and the introduction of maintenance and management. In addition, in order to facilitate the research and protection of Central Park by tourists, students, teachers, scholars and professionals, the Central Park Conservancy provides a guide to researching Central Park and the Central Park Conservancy (https://www.centralparknyc.org/central-park-research-guide accessed on 20 June 2022). The research guide lists a large number of research materials in detail, including books on general park history, biographies, memoirs and papers, guidebooks and descriptions, annual reports, Department of Parks files, management reports and other official documents, and news about Olmsted’s design ideas and the planning, design and management of Central Park. This study thus acts as an important source of literature and information.

- The online website of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/ accessed on 20 June 2022) and the Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (https://www.nycgovparks.org/news/reports/archive accessed on 20 June 2022) were used to search for resources. There are various electronic materials in the Library of Congress, such as newspapers, books, printed material, photos, prints, drawings, and manuscripts about Olmsted and Central Park. Olmsted’s manuscripts, historical photos, newspapers and historical maps of Central Park were selected from this website. The Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation contains historical reports, press releases, and minutes related to all parks and public places in New York, and was thus also an important source for our research.

- Finally, the Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/basic-search accessed on 20 June 2022) database and China’s National Knowledge Infrastructure (https://www.cnki.net/ accessed on 20 June 2022) were used to search for research papers by other researchers. “Olmsted” and “New York Central Park” were selected as keywords. The research results regarding these scholars, as well as the papers and resources related to our research that they referred to, were used as a source of information here.

2.3. Current Usage of the Park Extracted from TripAdvisor Comments

2.3.1. Post-Occupation Comments Extraction from TripAdvisor

2.3.2. Comment Processing and High-Frequency Word Coding

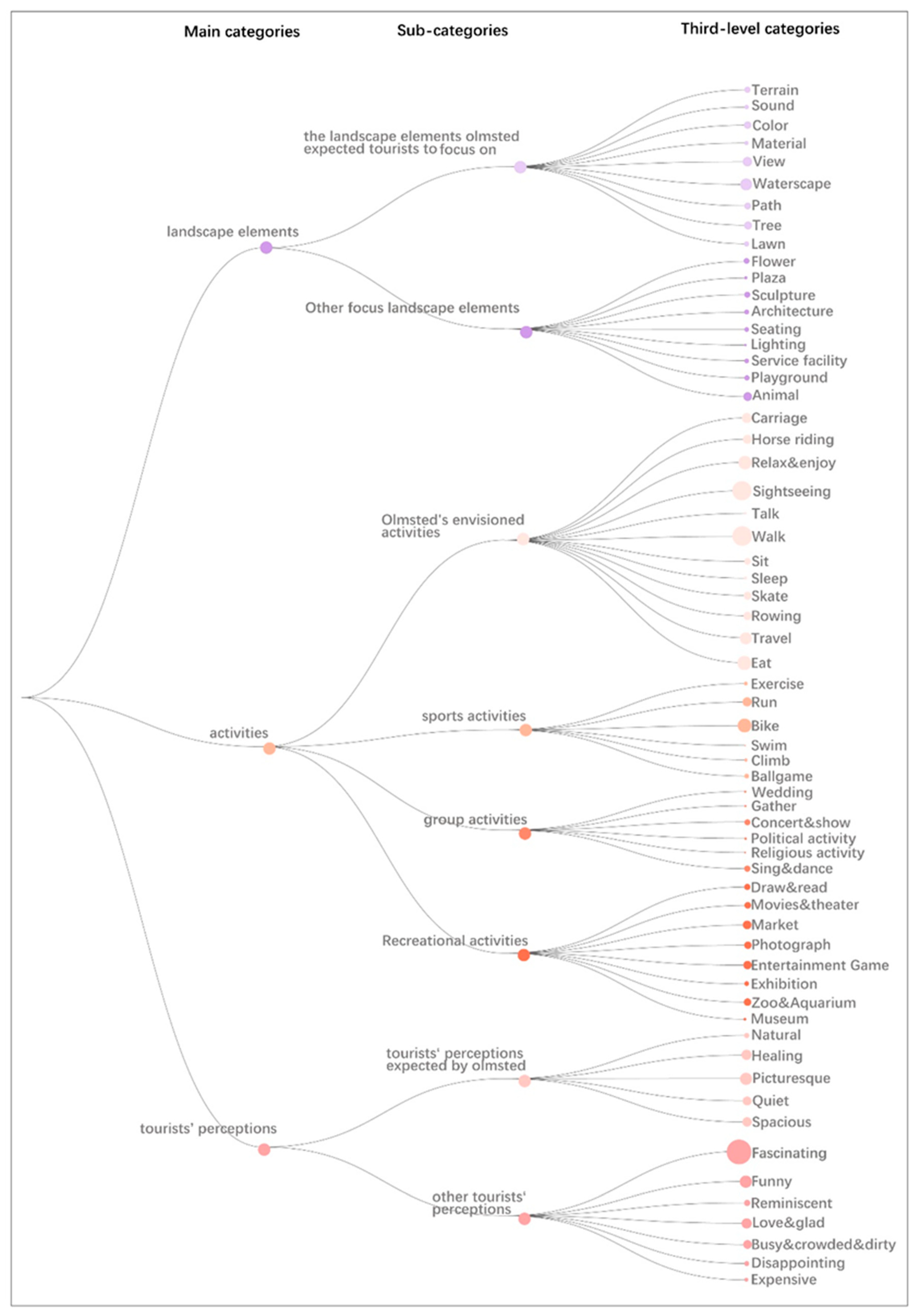

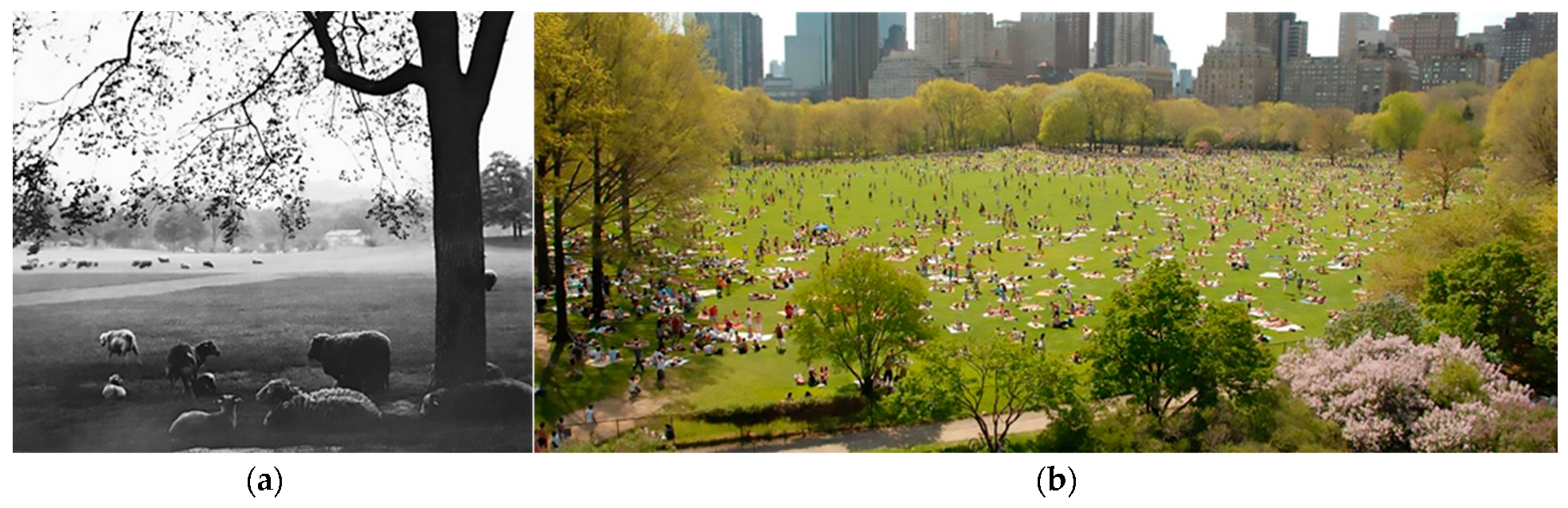

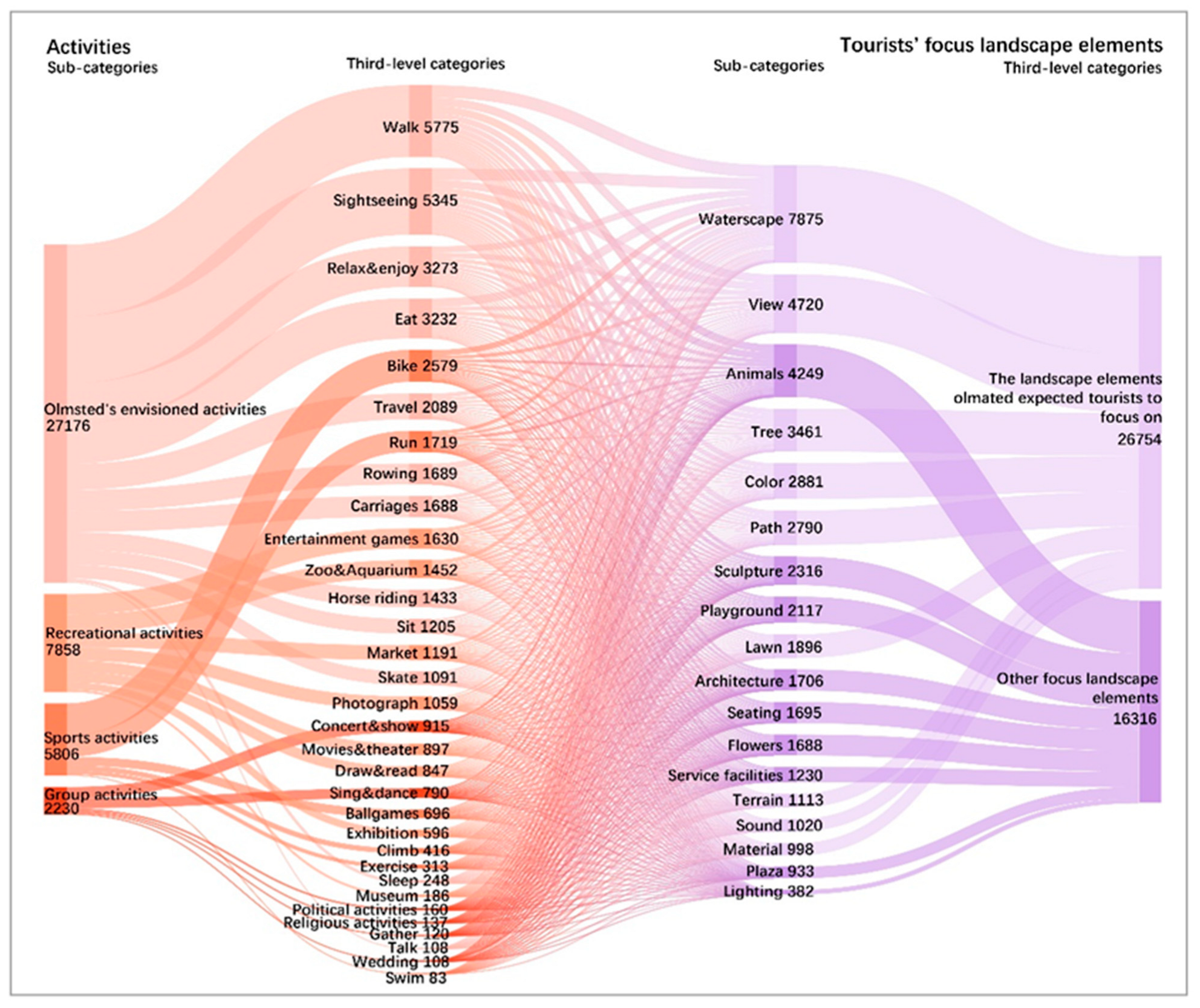

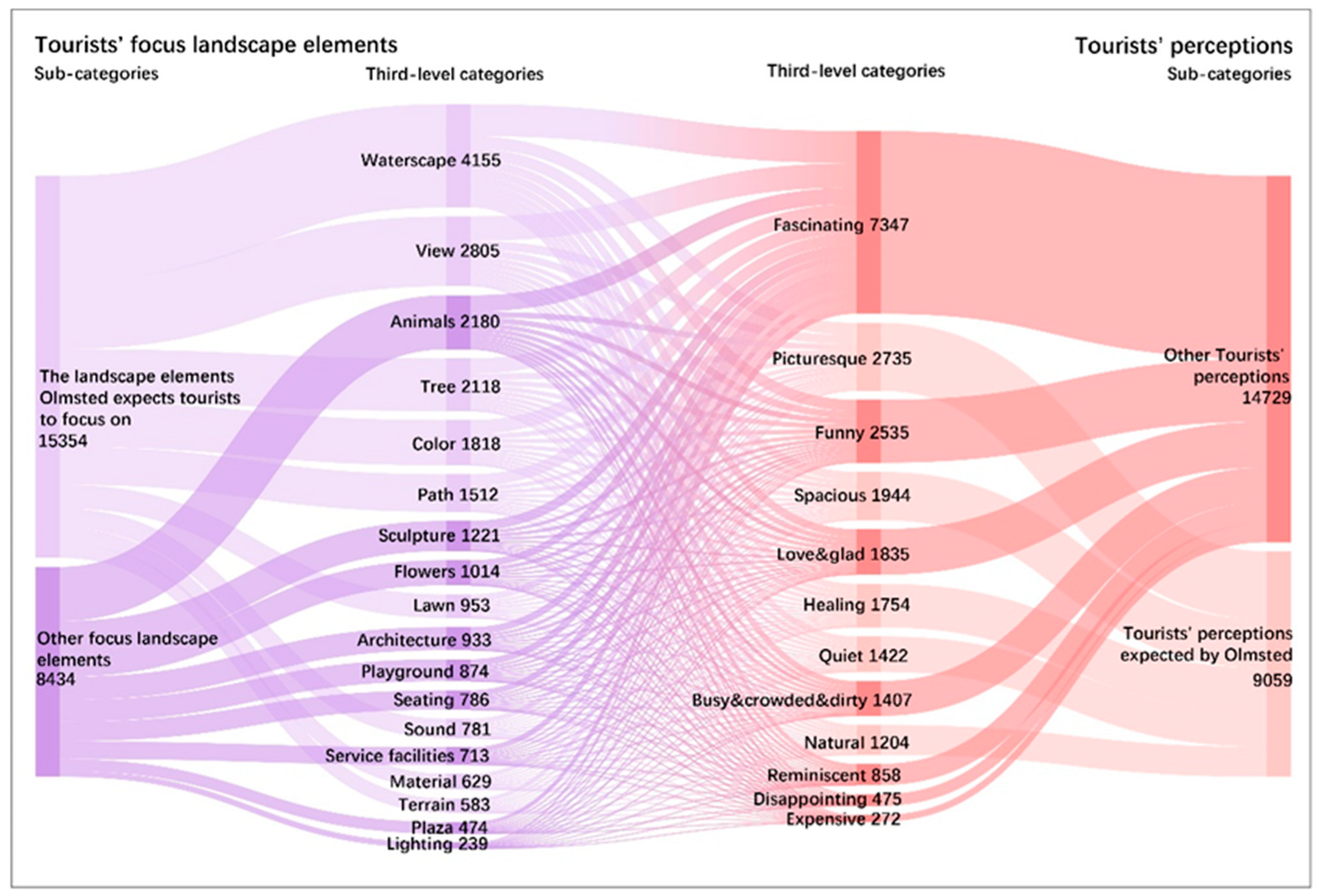

- Landscape elements. This category reflected the tourists’ attention towards the park elements and facilities. This category was further divided into the landscape elements designed or mentioned by Olmsted (terrain, sound, color, material, view, waterscape, path, tree, lawn, etc.) and other elements (flower, plaza, sculpture, architecture, seating, lighting, service facility, playground, animal, etc.).

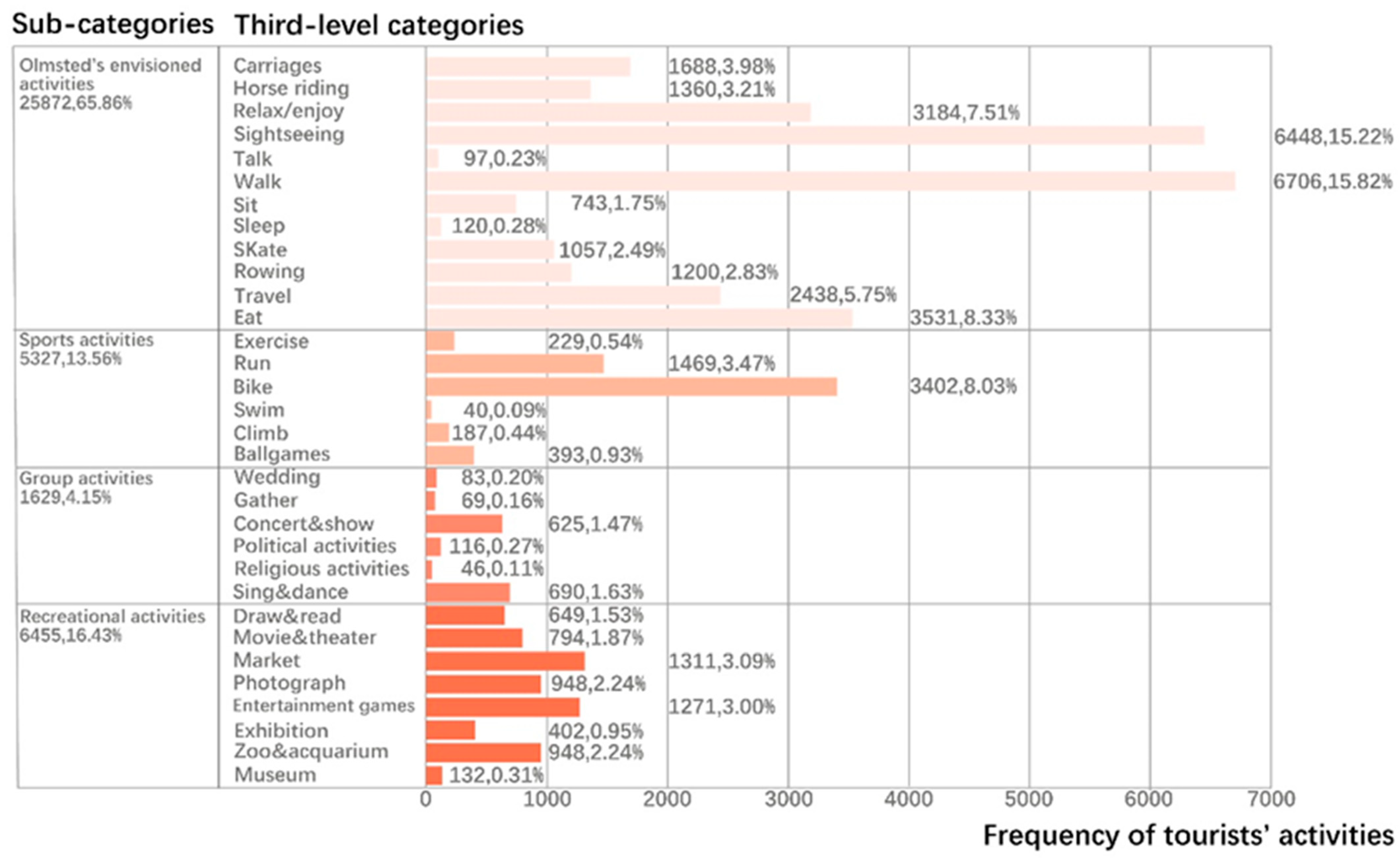

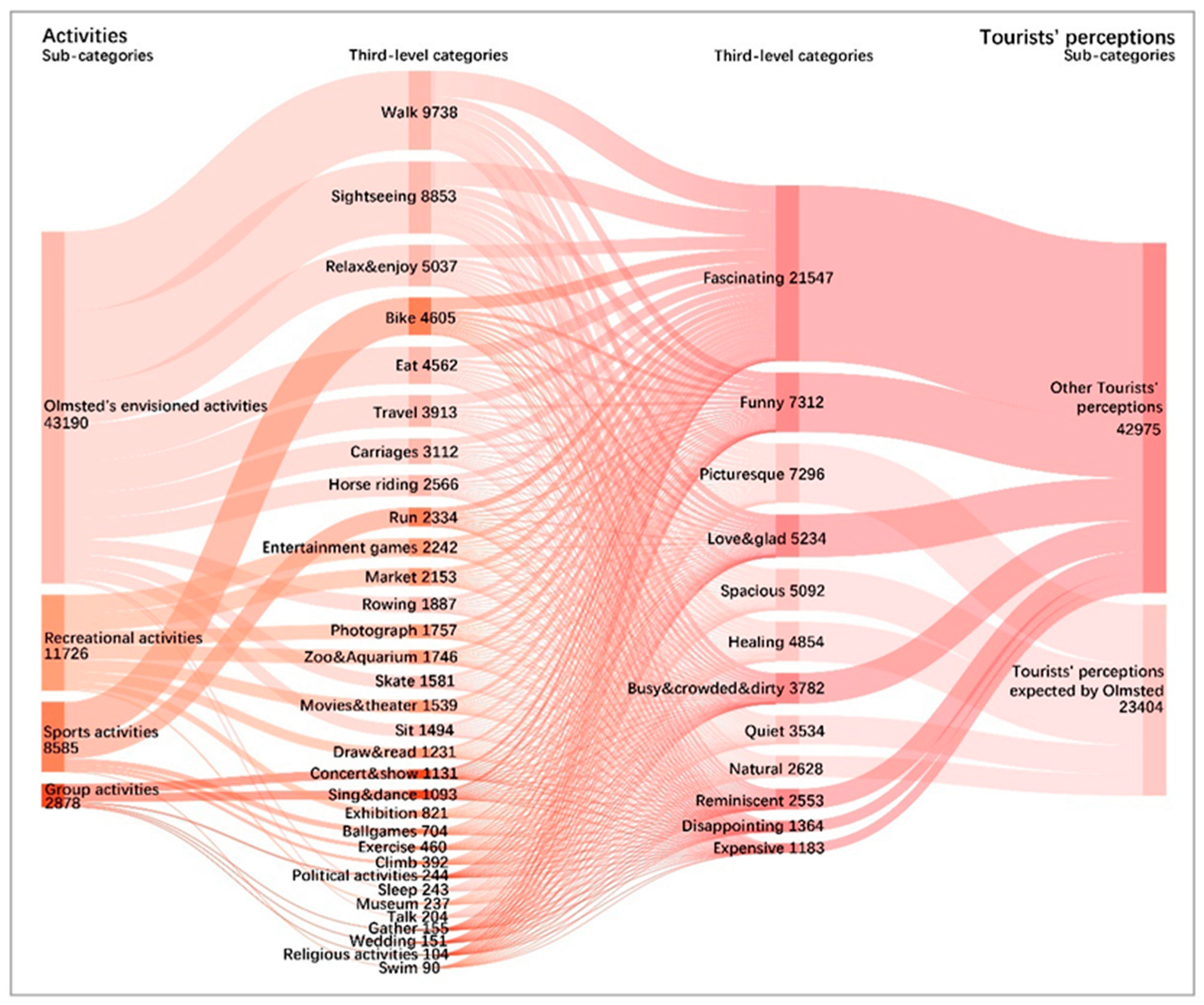

- Activities. This category described the types of visitor activities undertaken in the park. It was further divided into four subcategories, including the activities envisioned by Olmsted (carriage, horse riding, relaxing and enjoying, sightseeing, talking, walking, sitting, sleeping, skating, rowing, traveling, eating), sports activities (exercise, run, bike, swing, climb, ballgame), group activities (wedding, gather, concert and show, political activity, religious activity, sing and dance), and recreational activities (draw and read, movies and theatre, market, photo-taking, entertainment games, exhibition, zoo and aquarium, museum).

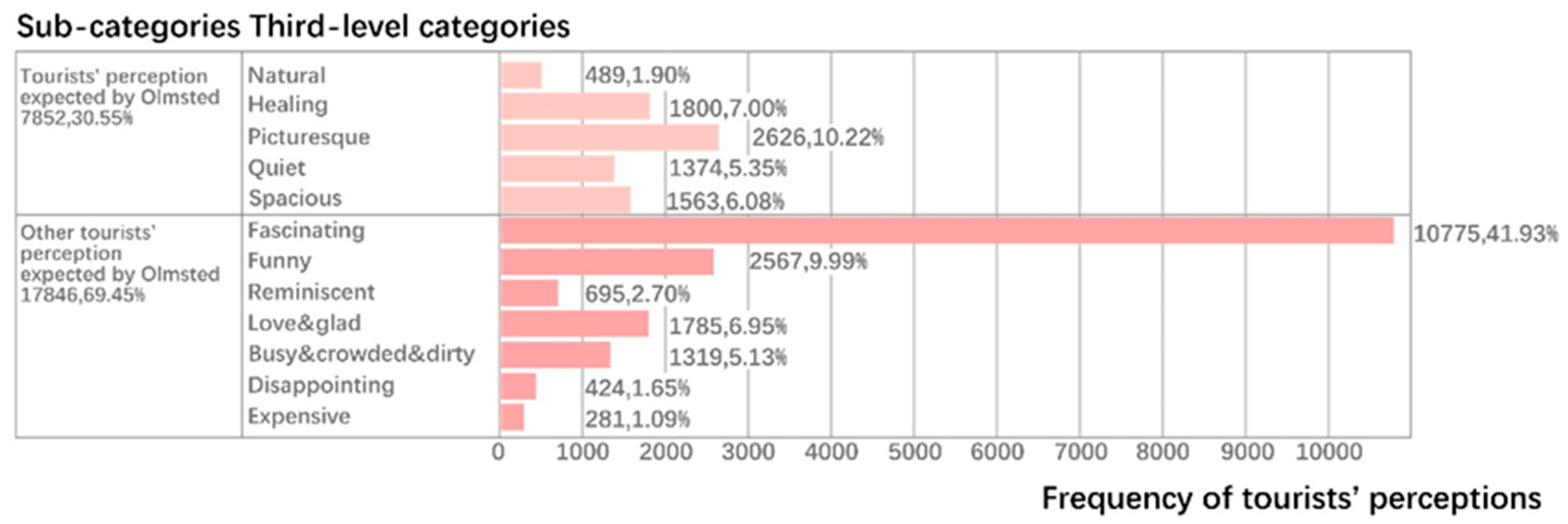

- Tourists’ perceptions. This category was further divided into the categories described by Olmsted (natural, healing, picturesque, quiet, spacious) and other perceptions (fascinating, funny, reminiscent, love, glad, busy, crowded, dirty, disappointing, expensive).

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Olmsted’s Design Theory

3.1. The Righteous Landscape Elements

3.2. The Desirable Activities

3.3. The Expected Tourists’ Perceptions

4. Big Data Analysis Results

4.1. Analysis of Tourists’ Focus on Landscape Elements

4.2. Analysis of Activities

4.3. Analysis of Tourists’ Perceptions

4.4. Analysis of the Relationship between Tourists’ Focus on Landscape Elements and Activities

4.5. Analysis of the Relationship between Tourists’ Focus on Landscape Elements and Perceptions

4.6. Analysis of the Relationship between Activities and Tourists’ Perceptions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, K.; Lin, Y.; Jiao, Z. Planning ideas of Olmsted–Beyond park design and landscape design. Chin. Gard. 2005, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, G. The construction and management of New York Central Park. Shaanxi For. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63–65, 71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L. The Formation and Development of the Planning Concept of Olmsted Urban Park. Master’s Degree, Shanxi Agricultural University, Shanxi, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, F. A case study on adaptive revitalization of the Central Park in New York. Chin. Gard. 2005, 68–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Commissioners of the Central Park. Annual Report on the Improvement of the Central Park; Wm., C., Ed.; Bryant & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1858; Available online: https://www.nycgovparks.org/news/reports/archive (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Central Park Conservancy. Central Park: A Research Guide. 2021. Available online: https://www.centralparknyc.org/central-park-research-guide (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Central Park Conservancy. About Us. Source. Available online: https://www.centralparknyc.org/about (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Kang, T. 160 Years of Central Park: A Brief History. 2017. Available online: https://www.centralparknyc.org/articles/central-park-history (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Duan, X. Heterogeneous imagination, tourist gaze and the reliability of visual representation of tourism evaluation websites: Take TripAdvisor’s photographs of Chinese and foreign tourists as an example. J. Liaoning Univ. 2020, 48, 122–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twombly, R.C. Frederick Law Olmsted: Essential Texts; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. New York Central Park. Chin. Gard. 1994, 38–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Reuniting Man and Nature: Recreating Nature Theme of New York’s Central Park. World Archit. 2003, 86–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, F.L. Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove: A Preliminary Report. 1865. Available online: http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/olmsted/report.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Taylor, D.E. Central Park as a model for social control: Urban parks, social class and leisure behaviour in nineteenth-century America. J. Leis. Res. 1999, 31, 420–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, F.L. General Order for the Organization and Routine of Duty of the Keepers’ Service of the Central Park; Document No. 43. Minutes; Department of Public Parks: New York, NY, USA, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, F.L. Report of the Landscape Architect on the Recent Changes in the Keepers’ Service; Document No. 47. Minutes; Department of Public Parks: New York, NY, USA, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, F.L. The Years of Olmsted, Vaux, and Co, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, 2nd ed.; Schuyler, D., Censer, J.T., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992; Volume 4, pp. 1865–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, F.L. Writings on Public Parks, Parkways, and Park Systems, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, 2nd ed.; Beveridge, C.E., Hoffman, C.F., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, L.W. FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R. Reviews on historical figures of American landscape architecture at beginning stage from the perspective of the history of civilization and its enlightenment. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 128–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beame, A.D.; Spatt, B.M. Landmarks Preservation Commission, Central Park Designation Report; Landmarks Preservation Commission: New York, NY, USA, 1974.

- Board of Commissioners of the Department of Parks for the City of Boston. Seventh Annual Report, for the Year 1881; Rockwell and Churchill: Boston, MA, USA, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Ozguner, H. Cultural differences in attitudes towards urban parks and green spaces. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, F.L. Creating Central Park, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, 2nd ed.; Beveridge, C., Schuyler, D., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1983; Volume 3, pp. 1857–1961. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, F.L. The Greensward Plan, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, 2nd ed.; Beveridge, C., Schuyler, D., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1958; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Typhina, E. Urban park design plus love for nature: Interventions for visitor experiences and social networking. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Luo, E.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Differing perceptions of the youth and the elderly regarding cultural ecosystem services in urban parks: An exploration of the tour experience. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talal, M.L.; Santelmann, M.V.; Tilt, J.H. Urban park visitor preferences for vegetation–An on-site qualitative research study. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, C.; Swait, J.; Vij, A.; Thiene, M. Determinants of recreational activities choice in protected areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Flowers, E.; Balla, K.; Deforchebc, B.; Timperioa, A. Designing parks for older adults: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xie, J.; Furuya, K. Assessing the preference and restorative potential of urban park blue space. Land 2021, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, H. Restorative benefits of urban green space: Physiological, psychological restoration and eye movement analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, P.O.W.; Agyei, F.K. Biodiversity, environmental health and human well-being: Analysis of linkages and pathways. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1085–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.W.F.; Brindley, P.; Mears, M.; McEwan, K.; Ferguson, F.; Sheffield, D.; Jorgensen, A.; Riley, J.; Goodrick, J.; Ballard, L.; et al. Where the wild things are! Do urban green spaces with greater avian biodiversity promote more positive emotions in humans? Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of neighbourhood nature: The benefits for mental health of living with nature. Bioscience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, K.R. The lungs of the city: Green space, public health and bodily metaphor in the landscape of urban park history. Environ. Hist. 2019, 24, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Remenyik, B.; Barcza, A.; Csapo, J.; Szabo, B.; Fodor, G.; David, L.D. Overtourism in Budapest: Analysis of spatial process and suggested solutions. Reg. Stat. 2021, 11, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, B. Using social media data in understanding site-scale landscape architecture design: Taking Seattle Freeway Park as an example. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Specific | Design Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape elements | lawn | 1. Lawn was necessary to creating picturesque park scenes |

| forest | 2. The forest created a lush and mysterious effect that was more interesting and entertaining than an urban enclosure. | |

| waterscape | 3. Waterscape will be best situated where it can be seen from the greatest number of widely distributed Points of view. | |

| plants | 4. The planting forms included solitary planting, group planting, and patch planting. High branch points and large crowns were preferred, with more native species and less delicate neatly trimmed plants. | |

| terrain | 5. The surface of the park should be smooth rather than rugged, and gently undulating rather than hilly. | |

| road | 6. Winding and rolling roads were more interesting, and straight roads were boring. | |

| architectures and sculptures | 7. Elements such as architectures and sculptures should be kept to a minimum. | |

| buildings | 8. The form of the buildings should keep a low profile and be consistent with the form of the landscape. | |

| Botanical gardens, zoos and other gardens | 9. Botanical gardens, zoos and other gardens should not be placed in parks. | |

| Activities | Activities he agreed to | 1. Peaceful recreation should be the main activity in an urban park. |

| 2. The public should be guided through the park landscape to unconscious relaxation. | ||

| 3. Olmsted had liked horse riding, rowing and skating since childhood, and he did not think that these activities were sports activities, but forms of transportation, so he designed enough space for these activities. | ||

| Activities prohibited by him | 1. Noisy, exciting games, and bad behaviour should be prohibited. | |

| 2. Not to walk upon the grass; Not to pick any flowers, leaves, twigs, fruits or nuts; Not to deface, scratch or mark the seats or other constructions; Not to throw stones or other missiles; Not to annoy the birds; Not to publicly use any provoking or indecent language; Not to offer any articles for sale. | ||

| 3. Fishing, swimming, playing musical instruments, giving speeches and climbing walls were added to the activities he prohibited. | ||

| Perceptions | 1. Urban parks should provide a place for spacious, quiet, natural, and picturesque experiences that restore calm. | |

| 2. Urban parks served to create the same degree of “poetic beauty” as the original natural features present in urban areas. | ||

| 3. Urban parks should present a feeling of “spaciousness and “tranquillity” with a “variety and intimacy” of arrangement. | ||

| 4. Urban parks act as a tranquil resting place for the soul, and brings people “tender, subdued and filial-like joy”. | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, X.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, W.; Mihalko, C. Testing Olmsted’s Lasting Legacy—Comparing Design Theory and the Post-Occupancy Conditions of New York Central Park. Buildings 2022, 12, 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122217

Zhu X, Zhang B, Xiang S, Zhao W, Mihalko C. Testing Olmsted’s Lasting Legacy—Comparing Design Theory and the Post-Occupancy Conditions of New York Central Park. Buildings. 2022; 12(12):2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122217

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Xun, Bo Zhang, Shurong Xiang, Wei Zhao, and Cheryl Mihalko. 2022. "Testing Olmsted’s Lasting Legacy—Comparing Design Theory and the Post-Occupancy Conditions of New York Central Park" Buildings 12, no. 12: 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122217

APA StyleZhu, X., Zhang, B., Xiang, S., Zhao, W., & Mihalko, C. (2022). Testing Olmsted’s Lasting Legacy—Comparing Design Theory and the Post-Occupancy Conditions of New York Central Park. Buildings, 12(12), 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122217