Collaborative Interorganizational Relationships in a Project-Based Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Method

2.1. Planning the Review

2.2. Conducting the Review

3. Research Synthesis

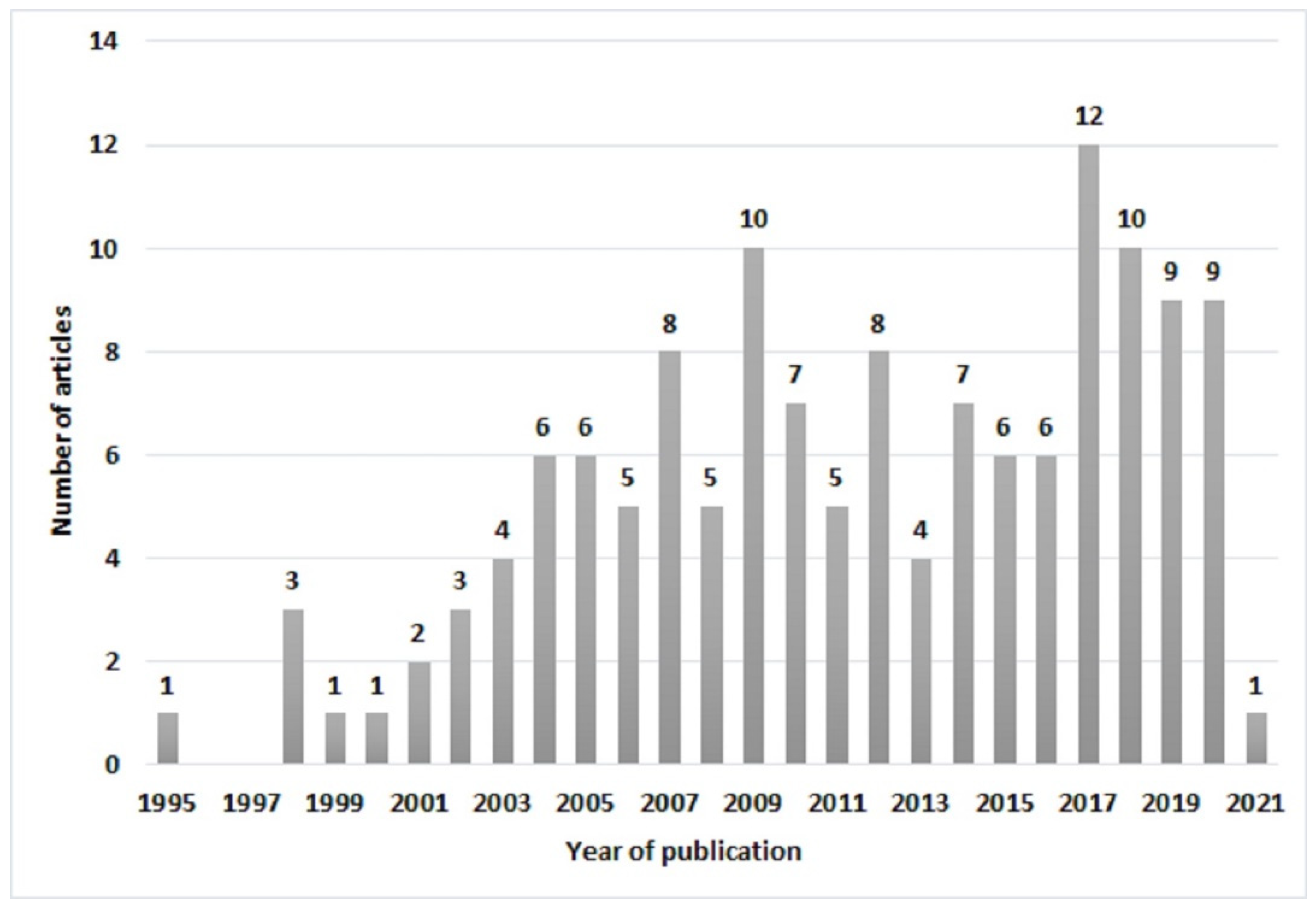

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Relational Forms Existing between Construction Companies (RQ1)

3.2.1. Partnering

3.2.2. Alliancing

3.2.3. Project Delivery Methods (PDMs)

3.2.4. Supply Chain Integration (SCI)

3.2.5. Joint Ventures (JVs)

3.2.6. Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

3.2.7. Joint Risk Management (JRM)

3.2.8. Collaborative Design

3.2.9. Contingent Collaboration

3.2.10. Quasi-Fixed Network

3.2.11. Resource Sharing

3.2.12. Collaborative Planning

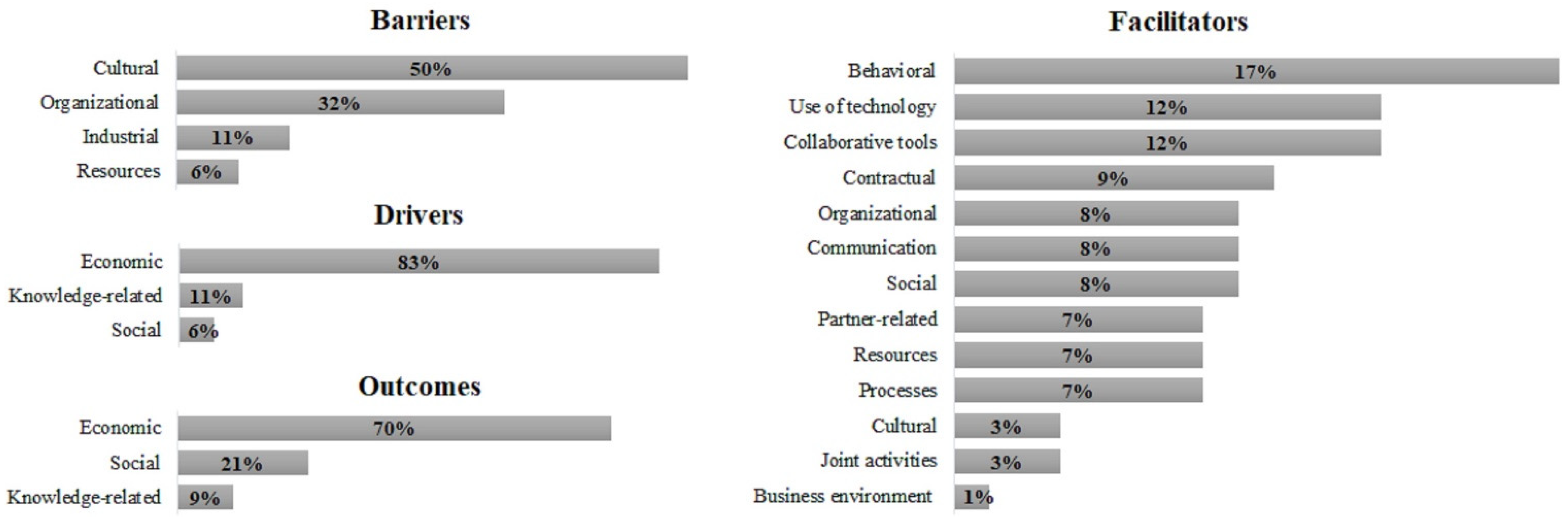

3.3. Drivers, Barriers, Facilitators, and Outcomes (RQ2)

3.3.1. Drivers

3.3.2. Barriers

3.3.3. Facilitators

3.3.4. Outcomes

4. Organizing Relationships in the Construction Industry

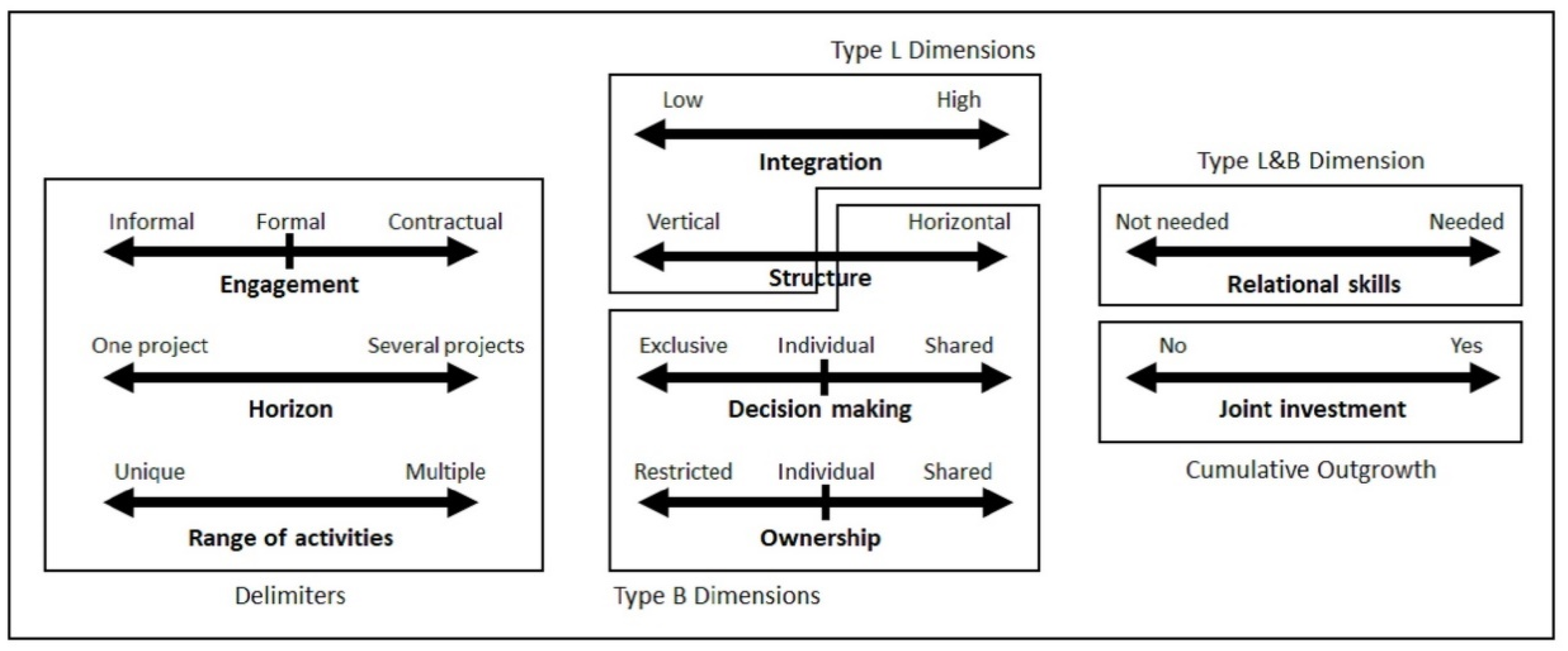

4.1. Multidimensional Profile

- Engagement: This refers to how partners will commit to each other and make sure that the duties and rights of each one is fulfilled. They may sign a contract (contractual), define a set of rules (formal), or just rely on social conventions with no declared rules (informal);

- Horizon: this relates to how long the collaborative IOR will last. Partners may choose to work together for one project (short-term), or engage in a series of projects (long-term);

- Range of activities: The range indicates whether the collaboration will be during one activity or phase of the project or encompasses the whole construction endeavor. Therefore, the collaborative work may be limited to one activity, or stretch over multiple ones (e.g., planification, design, and construction);

- Control i.e., decision-making: This dimension pertains to who will be in charge in terms of decisions, and hence assume liability. Partners can agree to pursue a joint decision-making (shared). It may be that each partner makes their own decisions separately (individual). Another possibility is that of a partner (dyadic relationship) or partners (multi-party relationship) assuming all the responsibility (exclusive);

- Ownership: This dimension mainly describes how financial assets will be organized between partners. These assets may refer to material possessions (e.g., construction equipment) or equities (e.g., in the case of a joint venture). This ownership can be distributed between partners according to agreed upon portions (shared), or each partner can use their own assets (individual). The ownership can be eventually restricted to one or some partners (exclusive);

- Structure: This indicates how the relationship will be organized in terms of positions in the supply chain. Hence, partners can have a client-supplier relationship (vertical) or be at the same supply chain level (horizontal). In some cases, a relationship may have features of both types, resulting in a hybrid structure;

- Integration: This dimension mainly refers to the “tangible activities or technologies” [78] and to what degree information systems are integrated, i.e., compatibility and effectiveness of communication [79]. The level of integration needed for the prospective IOR can be low due to previous collaborative efforts between partners or increased compatibility, or high due to the lack of compatibility of systems and communication procedures;

- Financial investment: This dimension portrays a direct consequence of all other dimensions, e.g., if a high degree of integration is requested, partners have to invest in some activities or technologies. This investment can be performed jointly or separately, for instance a partner may need to upgrade their information system for compatibility purposes.

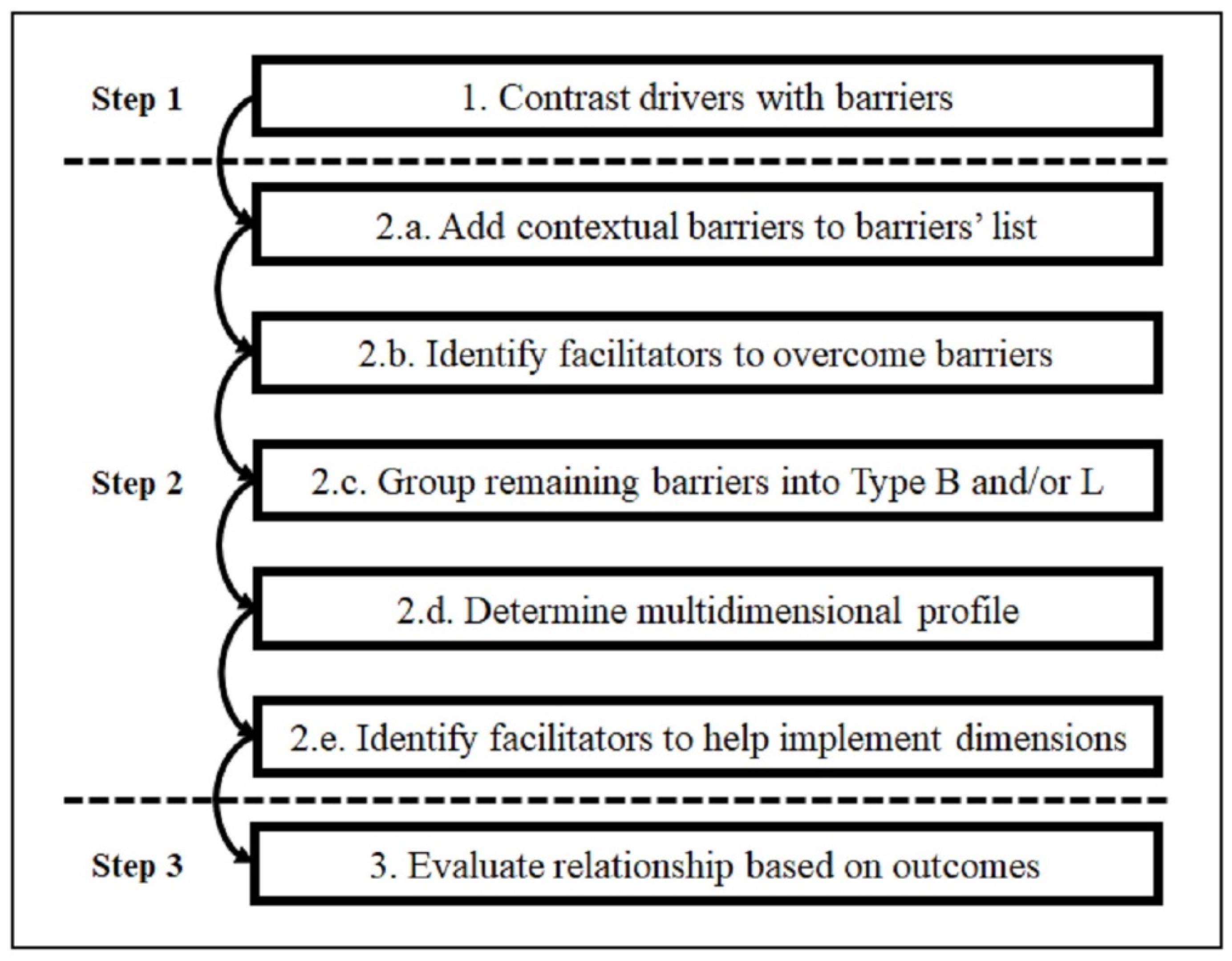

4.2. IOR Framework

5. Conclusions

- There is a coherent trend in construction publications, i.e., topics such as the building information modeling technology are gaining more attention [48]. Albeit such topics are important and reflect an increasing industrial need, other areas of interorganizational relationships should also be appropriately studied, such as supply chain-related issues, the perspective of organizational behavior (e.g., to study the element of trust), or building performance [40];

- A methodological gap that was often observed is the scarcity of longitudinal studies, which can examine the dynamic aspect of the construction industry and its actors;

- There is clearly a lack of quantitative models and especially mathematical and simulation modeling. Such techniques could be used e.g., to assess the risk coming from cases where companies work together;

- It was noticed that emerging branches of the construction industry, such as prefabricated wood construction, did not receive much recognition. According to Toppinen et al. [51], assessing the role of the socio-political environment in promoting the use of wood in construction projects is needed. In that regard, collaborative IORs can help implement new concepts, i.e., novel wood structures in a sector as conservative as the construction industry [13];

- There is a lack of studies on performance measurement of construction joint ventures, especially the aspects of sustainability and evolutionary contexts. Measurement factors are also an issue in governance structures. The question of how to better transfer knowledge between partners of CJVs should be addressed along with investigations on conflict contingencies and resolution. Because CJVs can be an international relational form, more attention should be given to developing countries [41];

- Publications addressing the topic of SCI in the construction industry are quite limited. Indeed, research works tend to discuss the supply chain management in general [70];

- The mechanism and impact of incentives is another research direction for future works.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Cheng, E.W.L.; Love, P.E.D. Partnering Research in Construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2000, 7, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction Industry Institute. SP17-1—In Search of Partnering Excellence; Univ. of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, M. Constructing the Team; HMSO: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. Rethinking Construction; Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions: London, UK, 1998.

- National Building and Construction Council. Strategies for the Reduction of Claims and Disputes in the Construction Industry—No Dispute; National Building and Construction Council: Canberra, Australia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, V. T40 Process Re-Engineering in Construction; Fletcher Construction Australia Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Gajendran, T.; Davis, P.R. Relational Contracting in the Construction Industry: Mapping Practice to Theory. In Proceedings of the AEI 2015, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 17 February 2015; American Society of Civil Engineers: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Saukko, L.; Aaltonen, K.; Haapasalo, H. Inter-Organizational Collaboration Challenges and Preconditions in Industrial Engineering Projects. IJMPB 2020, 13, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespin-Mazet, F.; Ingemansson Havenvid, M.; Linné, Å. Antecedents of Project Partnering in the Construction Industry—The Impact of Relationship History. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 50, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ey, W.; Zuo, J.; Han, S. Barriers and Challenges of Collaborative Procurements: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2014, 14, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnen, M.; Marshall, N. Partnering in Construction: A Critical Review of Issues, Problems and Dilemmas. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute. Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity; McKinsey & Company: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, A.; Blanchet, P.; Lehoux, N.; Cimon, Y. Collaboration Enables Innovative Timber Structure Adoption in Construction. Buildings 2018, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Challender, J.; Farrell, P.; Sherratt, F. Effects of an Economic Downturn on Construction Partnering. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Manag. Procure. Law 2016, 169, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engebø, A.; Lædre, O.; Young, B.; Larssen, P.F.; Lohne, J.; Klakegg, O.J. Collaborative Project Delivery Methods: A Scoping Review. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.F.Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chan, D.W.M. Defining Relational Contracting from the Wittgenstein Family-Resemblance Philosophy. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahdenperä, P. Making Sense of the Multi-Party Contractual Arrangements of Project Partnering, Project Alliancing and Integrated Project Delivery. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2012, 30, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.L.; Gonzalez, V.; Alarcón, L.F. Selection of Third-Party Relationships in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, B4013005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F.; Maqsood, T.; Khalfan, M. An Overview of Construction Procurement Methods in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.H.T.; Lloyd-Walker, B.M. Collaborative Project Procurement Arrangements; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-62825-067-1. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a Literature Review to a Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Devers, K.J. Qualitative Data Analysis for Health Services Research: Developing Taxonomy, Themes, and Theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, D.M.; Emmelhainz, M.A.; Gardner, J.T. So You Think You Want a Partner? Mark. Manag. 1996, 5, 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ngowi, A.B. The Role of Trustworthiness in the Formation and Governance of Construction Alliances. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.F.Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chan, D.W.M. The Definition of Alliancing in Construction as a Wittgenstein Family-Resemblance Concept. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnfot, A.; Sardén, Y. Prefabrication: A Lean Strategy for Value Generation in Construction. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction—Understanding and Managing the Construction Process: Theory and Practice, Santiago, Chile, 25 July 2006; pp. 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Anvuur, A.M.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Conceptual Model of Partnering and Alliancing. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, R.B. Partnering Construction Contracts: A Conflict Avoidance Process. AACE Int. Trans. 2004, CDR. 17, CD171–CD179. [Google Scholar]

- Bygballe, L.E.; Jahre, M.; Swärd, A. Partnering Relationships in Construction: A Literature Review. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2010, 16, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, P.; Love, P. Alliance Contracting: Adding Value through Relationship Development. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2011, 18, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, S.C.; Storgaard, K. Flexible Strategic Partnerships in Danish Construction. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual ARCOM Conference, Birmingham, UK, 4 September 2006; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Birmingham, UK, 2006; pp. 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E.W.L.; Li, H.; Love, P.E.D.; Irani, Z. Strategic Alliances: A Model for Establishing Long-Term Commitment to Inter-Organizational Relations in Construction. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; El-Sayegh, S. Critical Review of the Evolution of Project Delivery Methods in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, B.W.; Leicht, R.M. An Alternative Classification of Project Delivery Methods Used in the United States Building Construction Industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2016, 34, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrbom Gustavsson, T.; Samuelson, O.; Wikforss, Ö. Organizing IT in Construction: Present State and Future Challenges in Sweden. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. (ITcon) 2012, 17, 520–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, J.; Sutrisna, M.; Egbu, C. Modelling Knowledge Integration Process in Early Contractor Involvement Procurement at Tender Stage—A Western Australian Case Study. Constr. Innov. 2017, 17, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkling, A.E.; Mollaoglu, S.; Kirca, A. Research Synthesis Connecting Trends in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Project Partnering. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 04016033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Gao, X.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P.; Wang, G. Construction Supply Chain Integration: Past and Future. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2019, Banff, AB, Canada, 29 August 2019; American Society of Civil Engineers: Banff, AB, Canada, 2019; pp. 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kesidou, S.; Sovacool, B.K. Supply Chain Integration for Low-Carbon Buildings: A Critical Interdisciplinary Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, M.O.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of Concepts and Trends in International Construction Joint Ventures Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lu, C.; Chan, D.W.M. Review of Joint Venture Studies in Construction. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2017, Guangzhou, China, 9 November 2017; American Society of Civil Engineers: Guangzhou, China, 2017; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Ho, S.P. Impacts of Governance Structure Strategies on the Performance of Construction Joint Ventures. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, H.A.; Molenaar, K.R.; Alarcón, L.F. Exploring Performance of the Integrated Project Delivery Process on Complex Building Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.M.; Molenaar, K.R. Association between Construction Contracts and Relational Contract Theory. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2014, Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–21 May 2014; American Society of Civil Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014; pp. 1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Osipova, E.; Eriksson, P.E. The Effects of Procurement Procedures on Joint Risk Management. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual ARCOM Conference, Nottingham, UK, 7–9 September 2009; Dainty, A., Ed.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Nottingham, UK, 2009; pp. 1305–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Potential for Implementing Relational Contracting and Joint Risk Management. J. Manag. Eng. 2004, 20, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, J.M.; Saari, A.; Männistö, A.; Kähkonen, K. Indicators of Collaborative Design Management in Construction Projects. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2018, 16, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehn, L.; Bergström, M. Integrated Design and Production of Multi-Storey Timber Frame Houses—Production Effects Caused by Customer-Oriented Design. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2002, 77, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; He, Q.; Cui, Q.; Hsu, S.-C. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Construction Megaprojects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; Miilumäki, N.; Vihemäki, H.; Toivonen, R.; Lähtinen, K. Collaboration and Shared Logic for Creating Value-Added in Three Finnish Wooden Multi-Storey Building Projects. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 14, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shields, R.; West, K. Innovation in Clean-Room Construction: A Case Study of Co-Operation between Firms. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2003, 21, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Model of Equipment Sharing between Contractors on Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.I.; Pasquire, C.; Dickens, G.; Ballard, H.G. The Relationship between the Last Planner® System and Collaborative Planning Practice in UK Construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Écuyer, R. L’analyse de contenu: Notion et étapes. In Les Méthodes de la Recherche Qualitative; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 1987; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.H.T.; Johannes, D.S. Construction Industry Joint Venture Behaviour in Hong Kong—Designed for Collaborative Results? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfgren, P.; Eriksson, P.E. Effects of Collaboration in Projects on Construction Project Performance. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual ARCOM Conference, Nottingham, UK, 7–9 September 2009; Dainty, A., Ed.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Nottingham, UK, 2009; pp. 595–604. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.E.; Atkin, B.; Nilsson, T. Overcoming Barriers to Partnering through Cooperative Procurement Procedures. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2009, 16, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundquist, V.; Hulthén, K.; Gadde, L.E. From Project Partnering towards Strategic Supplier Partnering. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian Jelodar, M.; Yiu, T.W.; Wilkinson, S. Assessing Contractual Relationship Quality: Study of Judgment Trends among Construction Industry Participants. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 04016028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Le, Y. Understanding the Determinants of Program Organization for Construction Megaproject Success: Case Study of the Shanghai Expo Construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 05014019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerstedt, A.; Olofsson, T. Supply Chains in the Construction Industry. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, C.L.; Lowe, D.J.; Duff, A.R. Generating Opportunities for SMEs to Develop Partnerships and Improve Performance. Build. Res. Inf. 2001, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.I.A.; Flanagan, R.; Lu, S.-L. Managing the Complexity of Information Flow for Construction Small and Mediumsized Enterprises (CSMES) Using System Dynamics and Collaborative Technologies. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ARCOM Conference, Lincoln, UK, 7–9 September 2015; Raidén, A.B., Aboagye-Nimo, E., Eds.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Lincoln, UK, 2015; pp. 1177–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Suneson, K. Sensemaking and Organizational Boundaries—Aspects in Introducing Virtual Reality for Inter-Organizational Collaboration. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil and Building Engineering (2014), Orlando, FL, USA, 23–25 June 2014; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VI, USA, 2014; pp. 833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.E. Improving Construction Supply Chain Collaboration and Performance: A Lean Construction Pilot Project. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, T.; Cormican, K. The Influence of Technology on the Development of Partnership Relationships in the Irish Construction Industry. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2013, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutten, M.E.J.; Dorée, A.G.; Halman, J.I.M. How Companies without the Benefit of Authority Create Innovation through Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 24th ARCOM conference, Cardiff, UK, 1 September 2008; pp. 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Radziszewska-Zielina, E.; Szewczyk, B. Examples of Actions That Improve Partnering Cooperation among the Participants of Construction Projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 251, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, H.; Einur Azrin Baharuddin, H.; Arzlee Hassan, A.; Aisyah Asyikin Mahat, N.; Khalidah Kaharuddin, S. Success Factors Among Industrialised Building System (IBS) Contractors in Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 233, 022033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.; Webster, M.; Campbell, K.M. An Evaluation of Partnership Development in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. The Effect of Relationship Management on Project Performance in Construction. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, A.; Luo, J. Factors Affecting Construction Joint Ventures in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2004, 22, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Chan, D.W.M.; Ho, K.S.K. An Empirical Study of the Benefits of Construction Partnering in Hong Kong. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2003, 21, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, N.; Audy, J.-F.; D‘Amours, S.; Rönnqvist, M. Issues and Experiences in Logistics Collaboration. In Leveraging Knowledge for Innovation in Collaborative Networks; Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Paraskakis, I., Afsarmanesh, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 307, pp. 69–76. ISBN 978-3-642-04567-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom, B. Inter-Firm Collaboration, Networks and Strategy an Integrated Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9786610075706. [Google Scholar]

- Cruijssen, F.C.A.M. Horizontal Cooperation in Transport and Logistics; Tilburg University, School of Economics and Management: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koolwijk, J.S.J.; van Oel, C.J.; Wamelink, J.W.F.; Vrijhoef, R. Collaboration and Integration in Project-Based Supply Chains in the Construction Industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdev, H.S.; Thoben, K.-D. Anatomy of Enterprise Collaborations. Prod. Plan. Control. 2001, 12, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropper, S.; Ebers, M.; Huxham, C.; Ring, P.S. Introducing Inter-Organizational Relations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Dialdin, D.A.; Wang, L. Organizational Networks. In Blackwell Companion to Organizations; Baum, J.A.C., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Determinants of Interorganizational Relationships: Integration and Future Directions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Gemünden, H.G. Interorganizational Relationships and Networks. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Form | Engagement | Horizon | Range of Activities | Decision Making | Ownership | Structure | Integration | Investment | Number of Articles (% of 118) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnering | Non-contractual | Short- and long-term | From unique to multiple activities | Could be shared | Not shared | Any or none | High | Optimization-oriented | 52 (44%) |

| Alliancing | Contractual | Short- and long-term | From unique to multiple activities | Shared | Shared | Hybrid | High | Joint | 22 (19%) |

| Project delivery methods | Contractual | Short-term | Cover the whole project | Depends on the method | Not shared | Vertical and horizontal | Depends on the method | Individual | 19 (16%) |

| Supply chain integration | Rather contractual | Short- and long-term | Multiple | Could be shared | Not shared | Vertical and horizontal | High | Individual | 16 (14%) |

| Joint ventures | Contractual | Short- and long-term | Multiple | Depends on the governance | Depends on the governance | Horizontal | Depends on the governance | Joint | 13 (11%) |

| Integrated project delivery | Contractual | Short-term | Covers the whole project | Shared | Shared | Horizontal | High | Joint | 12 (10%) |

| Join risk management | Contractual | Short-term | Only planning | Shared | Not shared | Any | High | Individual | 4 (3%) |

| Collaborative design | Contractual | Short-term | Only design | Shared | Not shared | Vertical and horizontal | High | Individual | 3 (3%) |

| Contingent collaboration | Non-contractual | Short-term | Multiple | Not shared | Not shared | Any | High as a target | Individual | 2 (2%) |

| Quasi-fixed network | Rather formal | Short-term | From unique to multiple activities | Not shared | Not shared | Vertical and horizontal | Two levels | Individual | 1 (1%) |

| Resource sharing | Contractual | Short-term | Only construction | Not shared | Shared | Horizontal | Low | Individual | 1 (1%) |

| Collaborative planning | Formal | Short-term | Only planning | Shared | Not shared | Vertical and horizontal | High | Individual | 1 (1%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khouja, A.; Lehoux, N.; Cimon, Y.; Cloutier, C. Collaborative Interorganizational Relationships in a Project-Based Industry. Buildings 2021, 11, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11110502

Khouja A, Lehoux N, Cimon Y, Cloutier C. Collaborative Interorganizational Relationships in a Project-Based Industry. Buildings. 2021; 11(11):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11110502

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhouja, Ahmed, Nadia Lehoux, Yan Cimon, and Caroline Cloutier. 2021. "Collaborative Interorganizational Relationships in a Project-Based Industry" Buildings 11, no. 11: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11110502

APA StyleKhouja, A., Lehoux, N., Cimon, Y., & Cloutier, C. (2021). Collaborative Interorganizational Relationships in a Project-Based Industry. Buildings, 11(11), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11110502