1. Introduction

Industrialized construction is a method of construction that promotes the advancement of the process from design through construction by employing intelligent manufacturing and automation. Many other interchangeable terms have been used to describe industrialized construction, such as off-site construction [

1], prefabricated construction [

2], modular construction [

3], and manufactured homes [

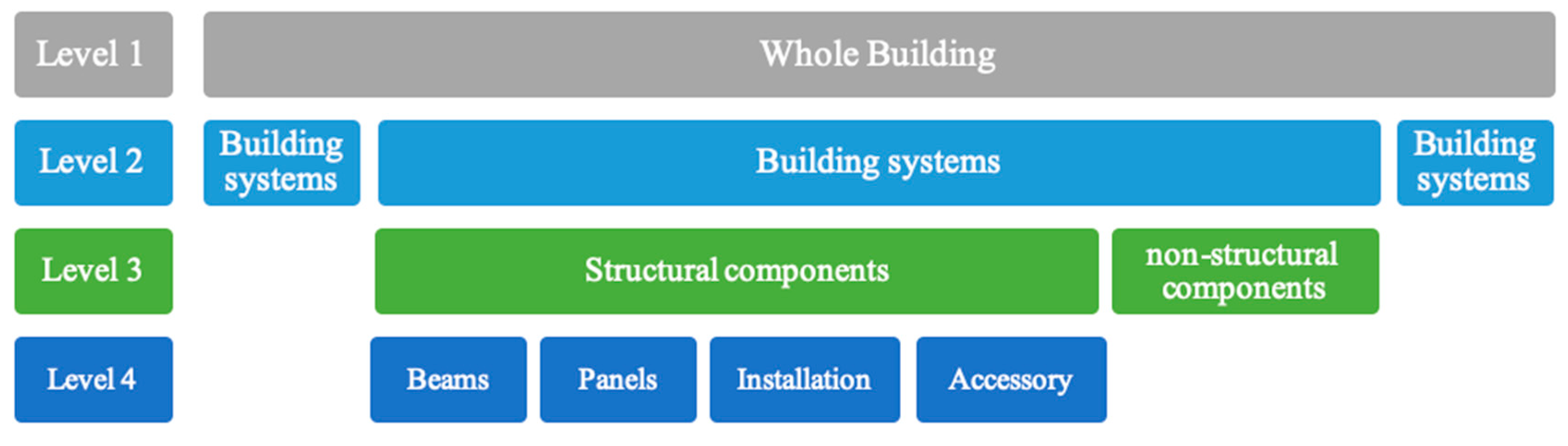

4]. There are differences between the definition and scope of these terms. In addition, industrialized construction works can be divided into four categories depending on the level of prefabrication (

Figure 1).

The benefits of industrialized construction have been well-explored. Some common arguments for industrialized construction being better than traditional construction include reducing construction cost, reducing construction time, and reducing labor [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, industrialized construction projects have increased gradually in the United States. According to the 2018 Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) report, 93,000 new modular residential homes were produced in 2017, approximately 9% of new single-family homes in the United States. However, industrialized construction still suffers from some issues such as lack of mutual communication, lack of manufacturing and installation quality inspection systems, and low supply chain efficiency [

10,

11,

12]. These issues may hamper the performance of industrialized construction and hinder the process of replacing traditional construction methods. Meanwhile, the factory-based nature of industrialized construction makes it easier to adopt the Industry 4.0 emerging technologies than traditional construction. The application of emerging technologies has the potential to mitigate the influence of these issues and further promote the development of industrialized construction.

Industry 4.0 is used to describe the tendency towards digitization, automation of the manufacturing environment. Many emerging technologies that enable the development of an automated and digital manufacturing environment are included within the concept of Industry 4.0 [

13]. In recent years, many new emerging technologies have been implemented into the modular construction production process in order to better exploit the advantages and overcome the challenges brought by industrialization. For example, [

6] proposed a prefabricated component management system framework with the assistance of RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) and BIM (Building Information Modeling) technology. [

14] adopted visual sensors for quality supervision on light-gauge steel frame production. Several researchers [

1,

15] claim that the combination of new technologies can significantly improve the management level of the industrialized construction project.

Despite the increasing amount of research in academia, the studies focusing on the development of emerging technology in the actual industrialized construction industry is limited. Our preliminary study [

16,

17] distributed a questionnaire survey to the construction practitioners in the United States to collect practitioners’ perceptions toward emerging technologies. Results indicate a discrepancy in the needs of emerging technology in industrialized construction between academia and industry. Specifically, the majority of the respondents agreed that the applications of technologies in the actual industrialized construction industry are relatively scarce. However, our preliminary research is based on a limited number of cases (i.e., 20 valid responses). Some gaps also still exist by reviewing recent years’ research and practice: (1) previous research (e.g., [

18]) have systematically categorized the emerging technologies in the manufacturing industry. However, the current mainstream technologies and the technologies with the greatest development potential in the actual industrialized construction industry remain unknown; (2) there have been limited studies focusing on the perceptions of practitioners towards potential barriers and benefits of emerging technologies in the industrialized construction despite these barriers and benefits having been identified in previous studies (e.g., [

19,

20]); (3) there have been limited investigations on whether practitioners’ company background and career profile can affect their perceptions on the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction. Filling these gaps can help adjust current research focus and give guidance on future research direction within the domain. It is also essential for the development and adoption of new technology.

Therefore, this paper aims to provide an in-depth understanding of industry practitioners’ attitudes towards the adoption of emerging technologies in the U.S. industrialized construction. The main objective of this paper is to answer the following four research questions:

1. What are the technology types with the highest current utilization level and future investment level?

2. What are the major factors, including benefit and challenge variables that affect the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?

3. Does the company background (i.e., type and size) of the practitioner affect their perceptions on the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?

4. Does the career profile (i.e., experience and position) of the practitioner affect their perceptions on the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?

This paper collectively adopts industrialized construction to contain all-inclusive terms referring to the process of production, transportation, and assembly of either prefabricated systems, components, or building structures. It includes all levels of prefabrication and types of off-site construction practices. This paper contributes to the body of knowledge of the industrialized construction by conducting a qualitative study that identifies the current and promising technologies, discusses the major benefits and barriers of implementing emerging technologies, and addresses practitioners’ perceptions of emerging technology.

2. Background

Recently, the manufacturing industry is experiencing the fourth Industrial Revolution, also referred to as Industry 4.0, that revolves around cyber-physical systems (e.g., the Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence) and the tendency towards digitization and automation of the manufacturing environment [

21]. Various types of emerging technologies under the concept of Industry 4.0 have been used in manufacturing sectors for the purpose of productivity improvement. Despite the construction industry often being blamed for its reluctance to implement emerging technologies and non-traditional management methods, some recent research attempted to integrate Industry 4.0 emerging technologies to keep up the pace with the other manufacturing sectors. Some technologies that are specific to the construction industry have also been developed. The incorporation of emerging technologies can help realize the expected performance improvement and benefits brought by industrialized construction. Meanwhile, the implementation of emerging technology might also bring some challenges to existing industrialized construction industry. The following sections will briefly introduce the emerging technologies existing in the manufacturing sector and what benefits and challenges they bring into the construction industry.

The new generation of smart machinery of Industry 4.0 is capable of monitoring the physical environment, performing functions with little or no direct human control, and also interacting with the cloud databases to create a gateway for implementing Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) [

19]. Various simulation and optimization algorithms are applied intensively to optimize the products, material, and production processes by mirroring the physical world in a virtual model [

22]. Advanced data analytic techniques such as big data and machine learning are adopted in order to deal with the complex and intensive knowledge, and data that appeared within the Industry 4.0 [

19,

20].

One of the base techniques to support Industry 4.0 is digital fabrication, which is a fabrication process controlled by a computer [

19]. Another base technique to support Industry 4.0 is the Internet of Things (IoT), referring to numerous connected devices that rely on sensory, communication, networking, and information techniques [

19,

20]. Regarding sensing technologies, many sensing techniques such as digital imaging and laser scanning are often applied to collect data from real project conditions [

18].

2.1. Technologies in the Construction Sector

Technologies and techniques from the manufacturing sector have been increasingly adopted into the construction industry. This new wave, called Construction 4.0, adopts automation, lean principles, digital technologies, and manufacturing techniques for offsite construction [

23]. Information and communication technologies that enable smart and connected cities, such as Cyber Physical Systems (CPS) and the Internet of Things (IoT), are also on the rise [

24]. The information integration system is also emerging in the construction industry for coordination, design documents sharing, and communication between project sectors. Effective information sharing and integration can be realized by existing Cloud-based business information models such as Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), and self-designed system integration applications. Additive manufacturing refers to the manufacturing technique that builds 3D objects by adding layer-upon-layer of material, which enables the automatic manufacturing of complex architectural components without extra labor costs.

Digital design, known as Building Information Modeling (BIM), is the central technology for the digitization of the construction environment and project delivery. The emergence of BIM tools also adds parametric and standard features into the 3D geometries and expands the application of 3D models. BIM enables the fusion of other technologies needed for various applications for construction [

25,

26]. The development in BIM now goes beyond 3D and creates the 4D (time), 5D (cost), or 6D (quality) models. Furthermore, Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Mixed Reality (MR) are getting attention for visualization of design information, creating real-and-virtual combined environments, and human-machine interactions.

2.2. Benefits and Challenges

The variety of technologies and techniques can bring a multitude of benefits to the industrialized construction industry. IoT technologies have been shown to increase construction safety and productivity [

27]. The quality of component manufacturing [

14] and on-site installation [

28] can be improved based on the quality inspection system using laser scanning, industrial cameras, and BIM. The total construction cost and time can also be reduced through the application of optimization and algorithms [

29,

30]. In addition, the requirements on labors can be eliminated through digital fabrication and automation techniques. 3D visualization techniques can help to train construction workers to understand the component assembling sequence better and thus enable the effective transfer of industrialization knowledge [

31]. Other benefits that emerging technologies can bring to the industrialized construction include sustainability and improved flexibility [

32].

Even with the multitude of benefits, there have been many challenges for integrating new technologies. Pervasive conservatism in the construction industry may become one of the challenges. Companies and workers from the construction industry are often unwilling to accept the innovation due to the reasons including lack of reliable hardware or software [

33], increased capital cost [

14], increased operation complexity [

34], lack of standards [

34], unawareness of the benefits [

35], worker push-back [

36], and unwillingness to change [

37]. In addition, the lack of interoperability (i.e., compatibility) between various software and equipment is another major challenge that needs to be addressed [

24]. The isolation between different systems would cause errors, omissions, or data loss when information is transferred from the application to application [

34]. Furthermore, information privacy and security issues are also the challenges that might impede the development of interoperability between different technologies [

19].

3. Research Methodology

This paper aims to have an in-depth understanding of industry practitioners’ attitudes towards the adoption of emerging technologies in industrialized construction in the United States. In order to answer the four research questions proposed in the Introduction section, this research applies the following methodology: (1) literature review; (2) interviews; (3) questionnaire survey design, distribution, and collection; and (4) data analysis. The scope of this research focuses on analyzing industry practitioners’ current state and future expectation of technology applications, and their views on the general benefits and technologies that emerging technologies could bring. The benefits and challenges specific to each technology are not included. In addition, this research only focuses on the U.S. construction industry and thus all the respondents are working in the United States. Due to the difference in the economy, society, and culture, the results and discussion obtained from this research may not be applicable to other countries. Industry practitioners are asked through a survey to evaluate their implementation of emerging technologies from four aspects, including current technology utilization level, future technology investment level, potential benefits, and challenges. The specific applied methods are presented in the following subsections.

3.1. Pilot Study

The pilot study focused on collecting the information necessary for designing the survey by reviewing academic literature and interviewing industry experts. Based on preliminary research [

16,

17], technologies that have already been applied or have the potential to be applied in the industrialized construction industry were grouped into twelve categories (See

Table 1). Similarly, nine major benefit variables and ten major challenge variables that might be encountered during the implementation of the emerging technologies in industrialized construction were also summarized (See

Table 2).

Afterward, four experts experienced in industrialized construction, including two construction management professors and two project managers from the modular construction company, were invited to a pilot interview to evaluate the rationality of the collected information. The purpose of this pilot interview was to evaluate whether the information retrieved from the literature is in line with the actual situation. The results of the interview validated the feasibility of the technology categorization and the existence of the selected benefits and challenges in the actual industry.

3.2. Survey Design

Based on the information collected from the pilot study, a four-part online survey was designed to collect industry practitioners’ perspectives. The first part introduced the objectives of this survey and had a brief introduction of the concepts about industrialized construction and each category of emerging technologies. The second part asked the respondents’ basic background information, which included company type, their company annual revenue, occupation type, and working experience. This part also has some multiple-choice questions that collect respondents’ past experience on industrialized construction projects (e.g., Have you utilized any industrialized construction strategies? Which type of projects have you utilized industrialized construction strategies?) and the locations of their industrialized construction projects. Question types included single-choice, multiple-choice, and text entry. The third part of the survey asked the respondents to rate their current utilization level and expected future investment level for each technology type in industrialized construction projects separately using a four-point scale (i.e., 1 = none, 2 = low level, 3 = medium level, 4 = high level). In the fourth part, respondents were requested to rate the impacts of identified benefit and challenge variables on their decisions to adopt emerging technologies using a four-point rating scale (i.e., 1 = none impact, 2 = low impact, 3 = moderate impact, 4 = high impact). A four-point rating, instead of a five-point or three-point rating, was used because it could avoid respondents’ selecting middle, non-committing answers [

38].

Afterward, the survey was sent to the same two project managers interviewed in the pilot to solicit feedback on the design, format, and content. In particular, some concepts extracted from academic literature might be a bit obscure for industry practitioners. These concepts were either reworded or clarified in additional notes. The survey was then updated accordingly, and the final version was published on the professional platform Qualtrics for distribution.

3.3. Survey Distribution and Collection

A snowball sampling method was utilized to distribute the survey. This method ensured a comprehensive and extensive delivery to people within the same domain [

39]. Twenty people, including eight manufacturers, four designers, and eight project managers from several modular construction companies in Florida, were selected as the initial respondents. They were then requested to answer the survey and distribute it to other knowledgeable participants working in the United States such as developers, modular homes designers, prefabricated components manufacturers, and the prefabrication general contractors. The respondents were sent e-mails containing the hyperlinks to access the survey. The survey distribution lasted for one month, starting from August 9 to September 9, 2019. The exact number of distributions could not be determined because according to the snowball distribution method, the initial respondents have been requested to distribute the survey link to any others they thought were appropriate.

3.4. Data Analysis

Respondents were also requested to evaluate their application of emerging technologies on four aspects: current technology utilization level, future technology investment level, benefits, and challenges. Some statistical methods were implemented to analyze the collected rating scores, including Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, average score ranking analysis, Shapiro–Wilk test, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Kruskal–Wallis test, and factor analysis.

3.4.1. Data Reliability

It was necessary to check the reliability of the scaled responses before the detailed analysis. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for internal consistency test was applied to test each item to ensure the reliability of the data. The value of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha should fall between 0 and 1. The closer the score is to 1, the greater the reliability of the data.

3.4.2. Average Score Ranking

The average score ranking analysis was applied to compare the importance level of specific items. The technology type with a high average score in current utilization and future investment level was regarded as the technology type that practitioners put a priority on. Technology type with a low score would indicate that it is not widely used. In addition, another indicator named development potential level was applied, which was the difference between the future investment level and current utilization level. It was assumed that the higher the development potential level is, the greater the potential is for the future development of the corresponding technology. Among benefit and challenge variables, those with the highest score were regarded as the major variables that influenced the adoption of emerging technologies. By comparison, a low impact level or lack of sufficient understanding from the respondents were considered to be the reasons that caused the low scores of specific variables. Results of the average score ranking analysis can be used to answer the first and second research questions.

3.4.3. Inter-Group Comparison

In addition to the overall analysis, it was necessary to investigate whether there existed significant differences in the perspectives of respondents from different companies or with different positions. Two methods that were commonly used for inter-group comparison: Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), which is a commonly used parametric statistical method that can investigate the differences between group means, and the Kruskal–Wallis test, which is a rank-based non-parametric statistical test. The application of parametric statistical tests was based on the assumption that data are normally distributed while non-parametric tests have no such assumption. Thus, it was necessary to adopt the Shapiro–Wilk test to test the normality of the data and therefore determine which method would be used for inter-group comparison [

40]. If the

p-value of the Shapiro–Wilk test was less than 0.05, then the data were not normally distributed, and the Kruskal–Wallis test would then be applied for inter-group comparison. Otherwise, the ANOVA would be adopted.

The respondents were grouped separately according to company type, company size, occupational positions, and working experience. Under each grouping, the research hypotheses would be set that practitioner’s perceptions are affected by the corresponding case. An ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test would then be applied to investigate whether there were significant differences on the ratings of respondents from different subgroups. If the generated p-value (i.e., probability value) was less than 0.05, then the null hypotheses were rejected and the research hypotheses were supported, which means there existed significant differences among the respondents’ attitudes from different groups. Results of the inter-group comparison would be used to answer the third and fourth research question.

3.4.4. Factor Analysis

In addition, this research had listed multiple benefit and challenge variables during the implementation of emerging technologies. Collapsing a large number of original variables into a few interpretable underlying factors would enable a better understanding of the situation and put forward associated measures to promote the development of emerging technologies in industrialized construction. Factor analysis is a statistical method to describe variability among observed, correlated variables in terms of a potentially lower number of unobserved variables called factors [

41]. In previous studies, factor analysis techniques were adopted to identify the factors associated with potential barriers that influence the adoption of offsite methods in housing construction [

38,

42]. This research adopted factor analysis to extract the major factors that promote or impede the application of emerging technologies in industrialized construction from the listed benefit and challenge variables. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett test of sphericity were also conducted to examine the feasibility of conducting a factor analysis method. The KMO statistic varies between zero and one. A KMO value close to one would indicate a strong correlation among variables and would verify the appropriateness for factor analysis. It was believed that the sample would be appropriate for factor analysis if KMO value was larger than 0.5 [

43]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity focused on testing whether a correlation matrix was an identity matrix, which would indicate that the variables were unrelated and thus not appropriate for factor analysis. If the

p-value of Bartlett’s test was smaller than 0.05, then the population correlation matrix would not be an identity matrix, and thus it would be suitable for factor analysis.

4. Results

This section presents the respondents’ demographic information as well as the data analysis results. Specifically, the overall analysis results of technology utilization can help answer the first research question (“What are the technology types with the highest current utilization level and future investment level?”); the inter-group comparison results of technology utilization level help answer the third research question (“Does the company background (i.e., type and size) of the practitioner affect their perceptions on the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?”); the overall analysis results of benefit and challenge variables answer the second research question (“What are the major factors, including benefit and challenge variables, that affect the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?”); and the inter-group comparison results of benefit and challenge variables answer the fourth research question (“Does the career profile (i.e., experience, position) of the practitioner affect their perceptions on the implementation of emerging technologies in industrialized construction?”).

4.1. Respondents’ Demographics

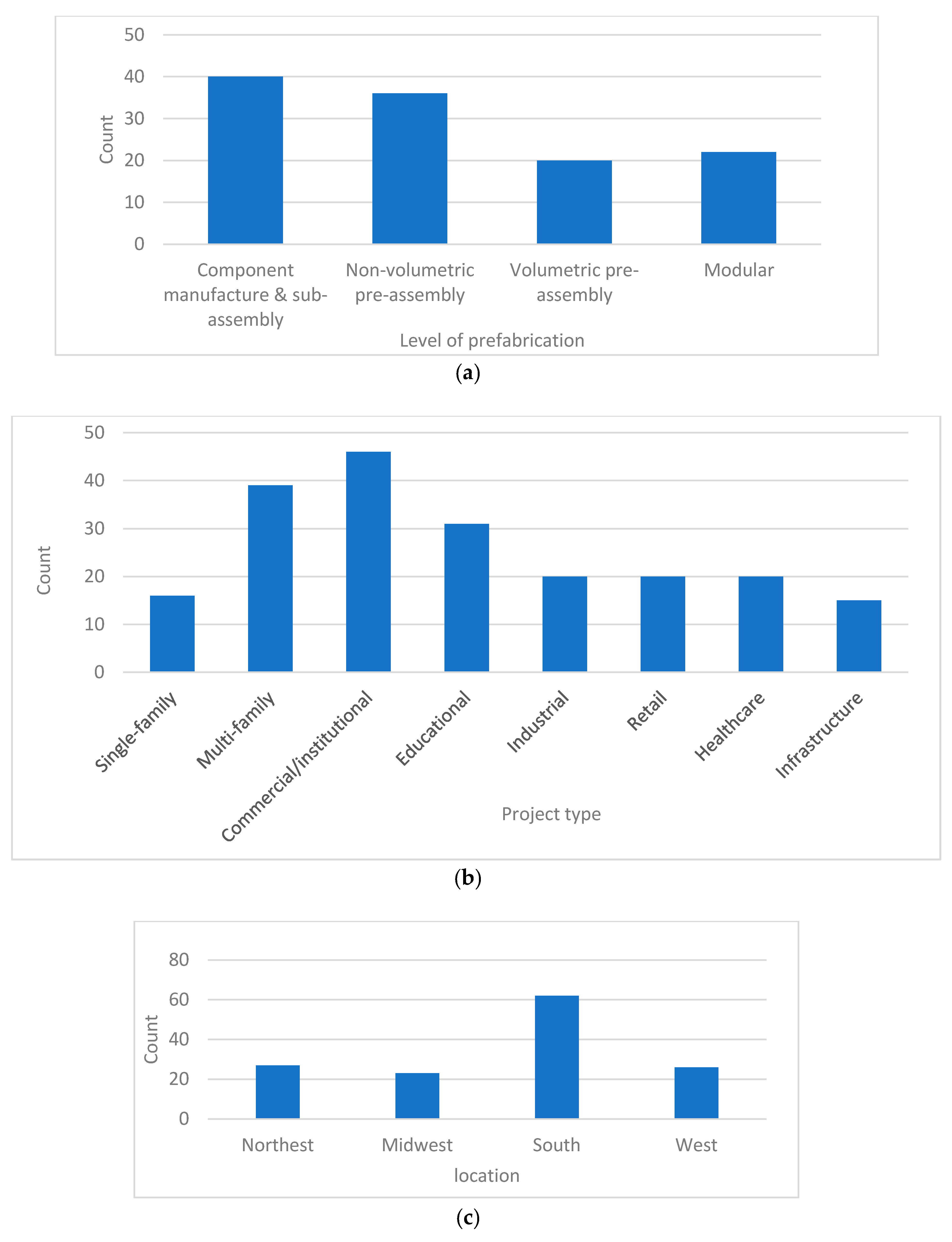

A total of 99 responses are received, in which 81 respondents (82%) are regarded as valid responses since they meet the criteria. As seen in

Figure 2, the component manufacture and sub-assembly technique, that is the lowest level of prefabrication, is the most widely applied prefabrication technique. Additionally, commercial/institutional, multi-family, and education projects are the top three industrialized project types that respondents have participated. In addition, the locations of respondents’ industrialized projects are scattered in different places in the United States.

Respondents are from different types of companies, in which more than half are from the construction company (

Table 3). The annual revenue of respondents’ organization is used to serve as an indicator of company size: the companies with annual revenue less than

$100 million USD are categorized into small-size; those with annual revenue within the range of

$100 million to

$1 billion USD are medium-size; those with annual revenue greater than

$1 billion USD are large-size. The working positions of respondents are also divided into different types where engineering and designing include civil engineer, mechanical engineer, electrical engineer, architect, interior designer, and structural designer; the project management group includes project manager, assistant project manager, and project executive; the management group contains the other managerial positions besides the project managers. In addition, the respondents are divided into three groups according to their working experience: the respondents with industry working experience less than 5 years are categorized as junior; those with industry working experience within the range of 5 and 15 years are categorized as middle; those with experience greater than 15 years are categorized as senior.

4.2. Technology Utilization

4.2.1. Overall Analysis

First, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha values for all twelve technology types in utilization level and future investment level are all around 0.92, which identifies the reliability of the data. Based on average score ranking analysis on total data,

Figure 3 summarizes the average current utilization level and average future investment level of 12 technology types. The standard deviations for these technology types are all around 0.9. Due to limited space, all technology types are represented by corresponding labels, and readers can refer to

Table 1 for the meaning of each label. Accordingly, 3D and nD (T3), business information model (T1), and sensing technology (T6) have the highest scores in both the average current utilization level and average future investment level.

4.2.2. Inter-Group Comparison

Shapiro–Wilk test results indicate that for all technology types, the

p-values are all smaller than 0.05, which means data are not normally distributed, and the Kruskal–Wallis test should be used for inter-group comparison. Respondents are divided into different groups according to different company types, company sizes, position types, and working experience.

Table 4 and

Table 5 present each group’s average current utilization level and average future investment level of each technology type, as well as the overall average scores of all technology types. Kruskal–Wallis test results for the inter-group comparisons are also presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

First, among four types of company, component manufacturers have the highest score of overall average current utilization level (2.14) and overall average future investment level (2.96). By comparison, developers have the lowest overall average current utilization level (1.67), and construction companies have the lowest overall average future investment level (2.5). Kruskal–Wallis test results indicate that other than autonomous machinery (T11), there is no significant difference on the current utilization level and future investment level of each technology type between four company types.

Then, in terms of different company sizes, it is found that large-size companies have the highest overall average current utilization level (2.16). Regarding the overall average future investment level, three groups are very close to each other. Moreover, the small-size companies have the lowest overall average current utilization level and future investment level (1.93) of all technology types. The differences in current utilization level and future investment level between companies of different sizes are not significant according to Kruskal–Wallis test results.

In terms of working experience, the senior group is with the highest overall average current utilization level (2.12). The junior group lags in the overall average current utilization level (1.88) behind the middle and senior group. In addition, the middle group is in the leading position in the overall average future investment level (2.68), with the senior group having the lowest score (2.55). Kruskal–Wallis test results indicate no significant differences in the current utilization level and future investment level of each technology type between practitioners with different working experience. In addition, it is surprisingly found that the future investment level of machinery (T11) and additive manufacturing (T12) have achieved relatively high scores in the middle group. The junior group has a relative high score on the future investment level extended reality (T5).

Regarding different working positions, the engineering and designing group has the highest score in both the overall average current utilization level (2.24) and overall average future investment level (2.83), with the project manager group being the lowest (1.78 and 2.38). Based on Kruskal–Wallis test results, other than 3D and nD models (T3), design optimization (T4), and digital fabrication (T10), respondents from different positions have not presented significant disagreements on current utilization level and future investment level of the rest of technology types.

4.3. Benefits and Challenges

4.3.1. Overall Analysis

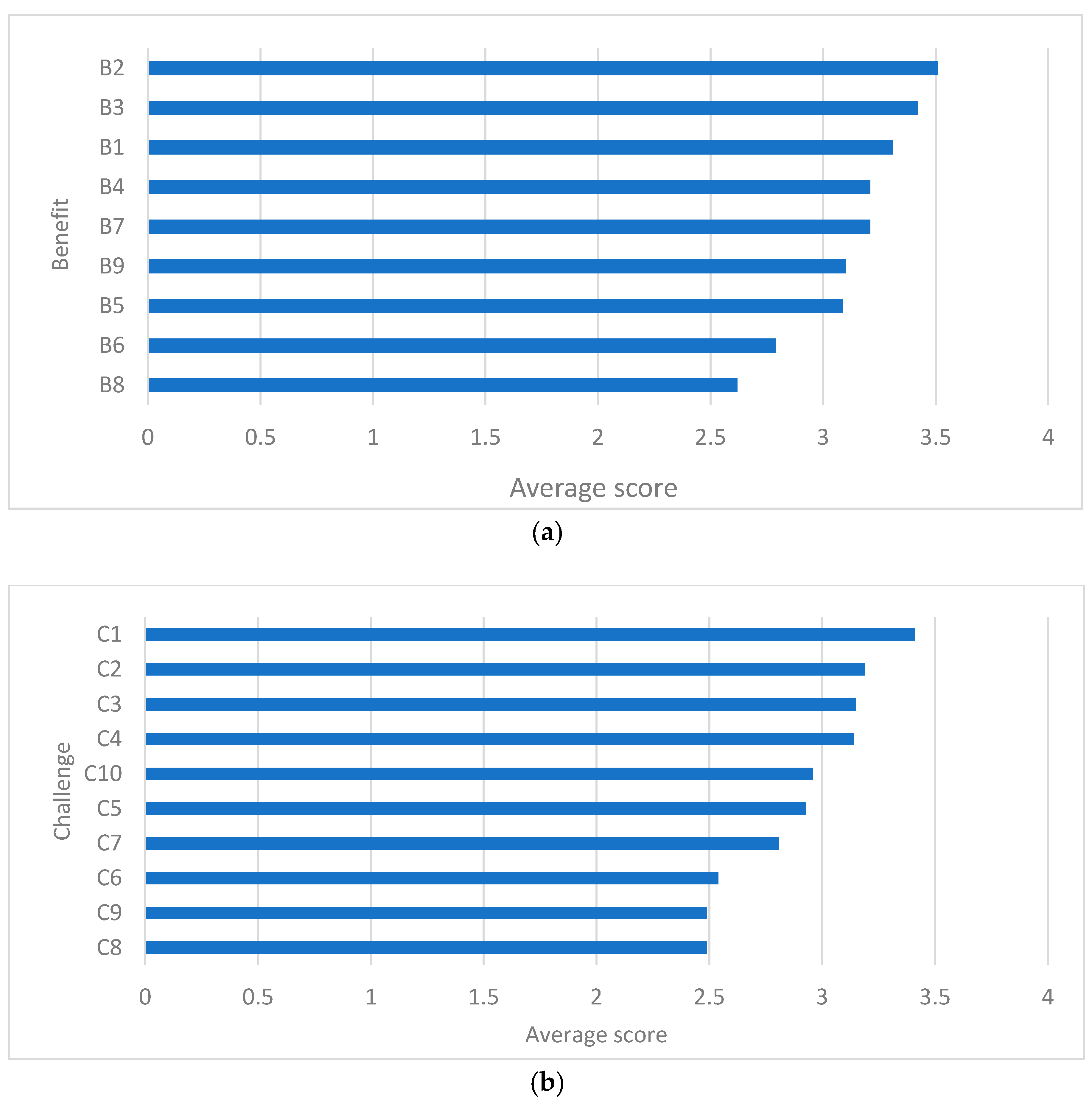

The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha value for all benefit and challenge variables’ ratings are all around 0.90, which identify the reliability of the data. Nine benefit and ten challenge variables are ranked according to average scores of total data, which are presented in

Figure 4. The standard deviations for these benefits and challenges are all around 1. The top three benefit variables with the highest average scores are reducing construction cost (B2), reducing construction time (B3), and improved quality (B1). In addition, three challenge variables with the highest average scores include high capital costs (C1), continuous demand for upgrading hardware and software (C1), and lack of software or hardware compatibility, applicability, and practicability (C3).

4.3.2. Inter-Group Comparison:

Shapiro–Wilk test results indicate that the

p-values are all smaller than 0.05 for all benefit and challenge variables, which means that the Kruskal–Wallis test should be used for inter-group comparison. The average scores of each variable and the overall average scores of all variables for different groups, as well as Kruskal–Wallis test results, are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7. Among four different company types, the overall average score of all benefit variables (3.17) for consultant organizations are the highest and developers are the lowest (2.93). For the overall average score of challenge variables, component manufacturers are the highest (3.16), with developers still being the lowest (2.83). With

p-values all larger than 0.05, it indicates no significant differences in the rating for benefit and challenge variables between four company type groups.

Regarding different sizes of company, large-size companies still lead in the overall average scores of benefit (3.22) and challenge variables (3.02), with the medium-size companies have the lowest value (2.91 and 2.74). Kruskal–Wallis test results indicate that differences on the rating for each benefit and challenge variable between three groups are not statistically significant.

In terms of three groups according to working experience, the senior group has the largest score in overall average scores of benefit (3.23) and challenge (3.07) variables, and the middle group has the lowest value (2.91 and 2.74). Kruskal–Wallis test results show that respondents with different working experiences show disagreement on several benefit (e.g., B3, B4, B6, and B9) and challenge (e.g., C1, C2, C4, and C10) variables.

Among three groups with different position types, the engineering and designing group has the highest value in overall average benefit (3.4) and challenge (3.12) variables, and the managerial group has the lowest value (2.87 and 2.48). It is presented by the Kruskal–Wallis test that respondents from different positions present significant disagreements on challenge variables (e.g., C4, C5, and C10).

4.4. Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is implemented on benefit and challenge variables separately, whose results are presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9. When conducting the factor analysis on benefit variables, the KMO value is 0.88 and the significance level of Bartlett’s test is 0.00, which all prove the appropriateness of using factor analysis. The factor analysis extracted two factors in explaining approximately 67% of variances. The first factor is named “project input” and consists of B2, B3, and B4. The second factor is named “project output”, including B1, B5, B6, B7, B8, and B9.

For the factor analysis in challenge variables, the generated KMO value is 0.84, and Bartlett’s test significance level is 0.000, which also proves the feasibility of factor analysis. Three factors have been extracted, which explain approximately 69% of variances. The first factor is named as skills and attitudes, which is comprised of C4, C10, and C5. The second factor is named as potential risks, including C9, C6, C7, and C8. The third factor includes C1, C2, and C3, which is referred to as cost and software constraints.

5. Discussion

Through the use of a questionnaire survey and various data analysis methods, this research focuses on answering the four research questions proposed in the Methodology section. The results can help identify the current development status and future development tendencies of emerging technologies in industrialized construction. The following subsections focus on summarizing several major trends revealed from data analysis results and explaining the answers to four research questions. Recommendations for future research directions are also proposed.

5.1. Current and Future of Technology Development

According to the ranking analysis, 3D and nD models, sensing techniques, and business information models are the top three technology types with the highest current utilization level and future investment level. It indicates that these three technologies are the most widely applied techniques by practitioners in the industrialized construction projects. By comparison, the extended reality, additive manufacturing, and advanced data analytics have the lowest current utilization level but have the largest development potential level (i.e., gaps between future investment and current utilization level). Therefore, more efforts are deserved to explore their applications in industrialized construction projects. Extended reality, often combined with 3D models, has the potential to be applied for construction safety improvement. Advanced data analytics, such as big data technology, has been investigated for its application in the construction data-driven decision-making process. Additive manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing is already being used in construction material property testing. These techniques have the potential to enhance the industrialization performance further and overcome the challenges that are difficult to be solved by currently mainstream techniques. Future research is suggested to investigate the influence of these technologies into industrialized construction.

5.2. Factors that Affect Practitioners’ Decisions

5.2.1. Benefits that Affect Practitioners’ Decisions

First, factor analysis divided the nine benefit variables into two broad factors. Three variables in the first factor (i.e., project input), namely reduce construction cost, reduce construction time, and reduce construction labor, are also the benefits with the highest score. Variable improved quality from the second factor (i.e., project output) is also among the top-scoring variables. These four benefit variables can be regarded as the variables that practitioners are most concerned about when they decide to adopt the emerging technologies in their industrialized construction projects. Research that highlights these benefits can be better recognized by practitioners and better promoted in the industry. Some benefits, such as the promotion of industrialization, environmental friendliness, and improved flexibility, have not gained too much attention from practitioners.

For existing research, it is necessary to develop the measurement criteria that mainly evaluate how emerging technology can affect the construction cost, time, labor requirement, and quality of the industrialized construction project. The reduction in cost, time and labor, and an improvement of quality should become the main goal and starting point of future research.

5.2.2. Challenges that Affect Practitioners’ Decisions

Factor analysis divided the ten challenge variables into three factors. It is found that three variables in the third factor (i.e., cost and software constraints), that is high capital cost, continuous software upgrading, and lack of software compatibility are exactly the top three variables with the highest scores.

First, the increased cost caused by the introduction of emerging technologies is made up of the purchase of equipment, the building of software, personnel training, operation, and maintenance. Recommendations for future research include conducting cost-benefit comparisons to prove the feasibility of the system and introducing cost-effective technology types.

Next, information incompatibility between different systems and different versions of the same system is another major challenge. Isolated systems can result in significant increases in cost and resource consumption for actual practice. Therefore, it is necessary to connect sub-systems into a single larger system that functions as one in future research. The integration of different standalone systems can reduce the training time for administers to use multiple tools, getting access to data easier, better collecting, and analyzing of real-time data. Techniques such as ontologies and the semantic web are encouraged to create the domain knowledge database to ensure the information interoperability between isolated sub-systems.

5.3. Practitioners’ Perspectives Comparison between Different Groups

The Kruskal–Wallis test has been used to compare the differences between the views of respondents from different groups. Kruskal–Wallis test results indicate that that practitioners’ company background (i.e., type and size) may have little significant influence on their opinions towards the application of emerging technologies, while their personal career profiles (i.e., working experience and position type) may have significant influences on part of their perspectives.

However, some trends can be obtained by observing the slight differences between each group’s overall average scores of four aspects (i.e., current utilization level, future investment level, benefit, and challenge variables).

In terms of different company types, component manufacturers and consultant organizations are ahead of the construction companies and developers in overall average scores of all four aspects. This indicates that component manufacturers and consultant organizations are more inclined to adopt technologies and have a clearer understanding of how each factor could affect the adoption of technologies in industrialized projects. Developers have the lowest overall average scores in three out of the four aspects (i.e., current utilization level, benefits, and challenges), which presents their relatively lower utilization level of technologies and unknown of the related knowledge. However, the overall average future investment level of developers is larger than construction companies. This phenomenon expresses their relative interest in leveraging emerging technologies to facilitate their work. Some technology-based applications, such as high-efficiency business information management systems, have the potential to improve the working efficiency of the developers.

In terms of different company sizes, large-size companies lead in overall average scores of three out of four aspects (i.e., current utilization level, benefits, and challenges). It implies that the companies with higher revenue are more likely to adopt emerging technologies in their industrialized projects. By comparison, the small-size companies put relatively fewer efforts on emerging technologies and thus lack sufficient knowledge about potential benefits and challenges brought by emerging technologies. However, the overall average future investment level of both the medium-size and small-size companies are very close to that of the large-size company, which expresses their interest in the application of emerging technologies in the future. As presented in

Figure 4, high capital costs and lack of technical training and the high cost of education are among the top-ranked barriers that affect the adoption of technology for both medium and small-size companies. Therefore, more research is needed to design appropriate training programs for project practitioners to effectively learn how to apply these techniques and how the techniques can benefit their working procedures. Moreover, some measures, such as the applications of low-price technology and effective cooperation between companies, should be encouraged in order to promote the development of emerging technologies for medium-size and small-size companies.

Compared to others, the senior group leads in overall average scores of three out of the four aspects (i.e., current utilization level, benefits, and challenges). It could be explained by longer working experience leading to more opportunities to get exposed to various types of technologies. However, the practitioners with a lot of working experience lag behind in their expectations on future investment levels of technologies. Smart machinery, additive manufacturing, and extended reality have received a high level of future investment expectation from the middle group and junior group. This indicates that practitioners with less working experience are more likely to hold open attitudes towards the adoption of emerging technologies. There are relatively fewer expectations from practitioners with long working experience on the future application of emerging technologies. The potential reason is that they are conservative and reluctant to accept new working methods. According to this result, future research can seek support from junior practitioners in the development and validation of research achievements.

In terms of different working positions, engineers and designers lead in all four aspects. Overall average current utilization level and overall average future investment level for managers and project managers is relatively low. They also present a lack of knowledge about how technologies can benefit or challenge their works in industrialized projects. However, various managers often play an important role in deciding to adopt emerging technologies in the whole industrialized construction projects. It is necessary to investigate how to apply various types of technologies to support the organization management works of managerial practitioners. Therefore, they can better understand how various types of technologies can support the whole industrialized construction. For example, advanced data analytics can help the managers to understand employee behaviors, organization operation, and market trends better. For project managers, they can also benefit from some technology-based applications such as construction process tracking.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, the application of emerging technologies from Industry 4.0 has gradually received attention from academia. However, research that investigates industry practitioners’ perspectives towards the application of emerging technologies is lacking. Based on preliminary research, a survey was designed and distributed to the industrialized construction industry practitioners through snowball sampling methods. Respondents were requested to rate their technology utilization level and the factors that affect their adoption of emerging technologies using a 1–4 scale. Based on the survey results, it was identified that the current mainstream technology (i.e., 3D and nD models, sensing techniques, and business information models) and the technology type with high development potential in the future (i.e., extended reality, additive manufacturing and advanced data analytic). By analyzing the benefit and challenge variables, it was found that project input (e.g., cost, time, and labor), cost and software constraints (high capital costs, continuous software upgrading, and lack of software compatibility) are the key factors that affect practitioners’ decisions to adopt emerging technologies. Based on inter-group comparison, company background (i.e., type and size) had little significant influence on practitioners’ opinions towards the application of emerging technologies, while their personal career profiles (i.e., working experience and position type) could significantly affect their perspectives. Even so, some tendencies were observed when comparing the overall average scores of different groups. For example, developers were among the lowest for all of the four aspects, with component manufacturers among the highest; large-size companies led in three of all four aspects with the small-size company being lowest in all four aspects; the senior group led three out of the four aspects except for future investment level; the engineer and designer group perceived a higher score for all of the four aspects compared to project manager and manager. Based on the results, several specific recommendations on future research have been summarized including: (1) increasing the exploration of extended reality, additive manufacturing and advanced data analytics in industrialized construction; (2) the reduction of cost, time and labor, as well as the improvement on quality should become the main indicators to evaluate the practicability of the developed system; (3) research on information interoperability should be emphasized; (4) designing technology-based applications that can improve the working efficiency for managers or developers; (5) introducing cost-effective technology types; (6) seeking for the support from junior practitioners in the development and validation of research achievements.

The major contributions of this paper include: (1) identifying the current mainstream emerging technologies and promising technologies in the actual industrialized construction; (2) identifying the major benefits and barriers of implementing emerging technologies in the industrialized construction projects; (3) identifying subgroup variations of perceptions towards applying emerging technologies in the industrialized construction. Significantly, such a comprehensive analysis of practitioner viewpoints can help promote the development of emerging technologies in the actual construction industry. Moreover, it can help adjust the current research focus and give guidance on future research direction within the domain.

Despite the great benefits, this paper still has a few limitations. First, it is found that nearly half of the respondents are from construction companies, which could cause bias in the survey results. Second, the language and format of the survey still needs to be improved since some of the feedback from the respondents present that they are unclear of the concepts of some technology types. Third, this research just investigates the overall impact of using technology. The in-depth interviews can be performed in the next step to specify impacts of each technology type further. Future research should also focus on expanding sample size to improve the reliability of the survey data. In addition, a model that specifies the relationship between the practitioners’ technology utilization level and their company background and career profiles should be set up, which could become a useful utilization level prediction and assessment tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Q., M.R., A.C. and C.K.; Methodology, B.Q. and M.R.; Validation, J.L. and S.Q.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.Q., M.R. and J.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.C. and C.K.; Supervision, A.C. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC was funded by the University of Florida College of Design, Construction and Planning (DCP) seed funding. Their support is gratefully acknowledged. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of others.

Acknowledgments

This study was approved by University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB201801656).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jin, R.Y.; Gao, S.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Aboagye-Nimo, E. A holistic review of off-site construction literature published between 2008 and 2018. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 1202–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benros, D.; Duarte, J.P. An integrated system for providing mass customized housing. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghaddos, H.; Hermann, U.; Abbasi, A. Automated crane planning and optimization for modular construction. Autom. Constr. 2018, 95, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.G.; Hastak, M.; Syal, M.; Hong, T. Framework of manufacturer and supplier relationship in the manufactured housing industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.; Ogden, R.; Goodier, C. Design in Modular Construction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 9780203870785. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Chen, K.; Costin, A.M. RFID and BIM-enabled prefabricated component management system in prefabricated housing production. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–4 April 2018; pp. 591–601. [Google Scholar]

- Abanda, F.H.; Tah, J.H.M.; Cheung, F.K.T. BIM in off-site manufacturing for buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Al-Hussein, M. Building information modelling for off-site construction: Review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Holistic review and conceptual framework for the drivers of offsite construction: A total interpretive structural modelling approach. Buildings 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lee, M.W.; Jaillon, L.; Poon, C.S. The hindrance to using prefabrication in Hong Kong’s building industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, H.; Canal, C.; Costin, A. Modular Construction: Assessing the Challenges Faced with the Adoption of an Innovative Approach to Improve U.S. Residential Construction. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress, Hong Kong, China, 17–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam, S.; Ngo, T.; Gunawardena, T.; Henderson, D. Performance review of prefabricated building systems and future research in Australia. Buildings 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, T.D.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Comput. Ind. 2016, 83, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Hussein, M. A vision-based system for pre-inspection of steel frame manufacturing. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Wang, L. Identifying barriers to off-site construction using grey dematel approach: Case of China. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razkenari, M.; Qi, B.; Fenner, A.; Hakim, H.; Costin, A.; Kibert, C.J. Industrialized construction: Emerging methods and technologies. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2019: Data, Sensing, and Analytics, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 352–359. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Costin, A.M. Challenges of implementing emerging technologies in industrialized construction. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress, Hong Kong, China, 17–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oztemel, E.; Gursev, S. Literature review of Industry 4.0 and related technologies. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 127–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. Industry 4.0: A survey on technologies, applications and open research issues. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2017, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xu, E.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends, International. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallasega, P.; Rauch, E.; Linder, C. Industry 4.0 as an enabler of proximity for construction supply chains: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. 2018, 99, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Martínez, J.A.; Pérez-Lara, M.; Marmolejo-Saucedo, J.A.; Salais-Fierro, T.E.; Vasant, P. Industry 4.0 framework for management and operations: A review. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput 2018, 9, 789–801. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney, A.; Riley, M.; Irizarry, J. Construction 4.0: An Innovation Platform for the Built Environment; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 13-978-0367027308. [Google Scholar]

- Costin, A.; Eastman, C. Need for Interoperability to Enable Seamless Information Exchanges in Smart and Sustainable Urban Systems. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2019, 33, 04019008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.; Teizer, J.; Schoner, B. RFID and BIM-Enabled Worker Location Tracking to Support Real-time Building Protocol Control and Data Visualization on a Large Hospital Project. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. (Itcon) 2015, 40, 495–517. [Google Scholar]

- Costin, A.; Teizer, J. Fusing Passive RFID and BIM for Increased Accuracy in Indoor Localization. Vis. Eng. 2015, 3, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Costin, A.; Wehle, A.; Adibfar, A. Leading Indicators—A Conceptual IoT-Based Framework to Produce Active Leading Indicators for Construction Safety. Safety 2019, 5, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.Z.; Zhong, R.Y.; Xue, F.; Xu, G.; Chen, K.; Huang, G.G.; Shen, G.Q. Integrating RFID and BIM technologies for mitigating risks and improving schedule performance of prefabricated house construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, R.; Formoso, C.T.; Viana, D.D. Site logistics planning and control for engineer-to-order prefabricated building systems using BIM 4D modeling. Autom. Constr. 2019, 98, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, H.M.; Chalasani, T.; Logan, S. Exterior prefabricated panelized walls platform optimization. Autom. Constr. 2017, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Z.; Mei, T.; Li, Q.; Li, P. Labor crew workspace analysis for prefabricated assemblies’ installation: A 4D-BIM-based approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 374–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperzyk, C.; Kim, M.K.; Brilakis, I. Automated re-prefabrication system for buildings using robotics. Autom. Constr. 2017, 83, 184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Li, M.; Chen, C.H.; Wei, Y. Cloud asset-enabled integrated IoT platform for lean prefabricated construction. Autom. Constr. 2018, 93, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaji, I.J.; Memari, A.M.; Messner, J.I. Product-oriented information delivery framework for multistory modular building projects. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2017, 31, 04017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Lu, W.; Liu, D.; Chen, K.; Anumba, C.; Huang, G.G. An SCO-enabled logistics and supply chain–management system in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 143, 04016103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.; Pradhananga, N.; Teizer, J. Leveraging Passive RFID Technology for Construction Resource Field Mobility and Status Monitoring in a High-Rise Renovation Project. Autom. Constr. 2012, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Costin, A.; Adibfar, A.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.S. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for transportation infrastructure—Literature review, applications, challenges, and recommendations. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, R.F.; Liu, A.M. Research Methods for Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Gao, Y. Constraints on the promotion of prefabricated construction in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2516. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, B.G.; Shan, M.; Looi, K.Y. Key constraints and mitigation strategies for prefabricated prefinished volumetric construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Norusis, M.J. SPSS 16.0 Advanced Statistical Procedures Companion; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.; Shen, Q.; Pan, W.; Ye, K. Major Barriers to off-site construction: The developer’s perspective in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 31, 04014043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika 1970, 35, 401–405. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).