Abstract

This article focuses on gendered experiences of the criminal justice system, specifically the experiences of adult female victims of sexual offending and the communication difficulties they experience during the criminal justice process. Drawing on the findings from qualitative interviews about sentencing with six victims and 15 justice professionals in Australia, we compare the lived experiences of the victims with the perceptions of the justice professionals who work with them, revealing a significant gap between the information justice professionals believe they are providing and the information victims recall receiving. We then analyse the international literature to distil effective communication strategies, with the goal of improving victims’ experiences of the criminal justice system as a whole. Specifically, we recommend verbal communication skills training for justice professionals who work with victims of crime and the development of visual flowcharts to help victims better understand the criminal justice process. We also recommend that Australian victims’ rights regimes be reformed to place the responsibility for providing information about the criminal process on the relevant justice agencies, rather than requiring the victim to seek this information, and suggest piloting automated notification systems to help agencies fulfil their obligations to provide victims with such information.

1. Introduction

This article considers the criminal justice experiences of adult female victims of sexual offending in Australia. It is drawn from a larger project on the use of victim impacts statements in sentencing (see Davies 2017; Davies and Bartels forthcoming). Victim impact statements (or VIS) were introduced in Australia from the 1980s, among a range of reforms intended to address the re-traumatisation of sexual offence victims (Australian Law Reform Commission 2010) and reduce ‘many of the anti-therapeutic tendencies entailed by [victims’] involvement in [criminal justice] proceedings’ (Erez et al. 2011, p. 37). These statements are prepared by the victim prior to sentencing and outline the harms caused to them as a consequence of the offending.

Despite being introduced, in part, to address problems arising from the justice system experience of victims of sexual offending, subsequent impact statement research has generally excluded victims of sexual offending, not distinguished their experiences from those of other crime victims, and not involved interviews with victims themselves (see Du Mont et al. 2008; Miller 2013). Miller has explained that:

‘The few studies that were designed to specifically examine VIS use by sexually assaulted women are now outdated, did not originally include empirical data from victims, or combined victims’ use of the VIS with other forms of criminal justice participation, which made meaningful interpretation difficult’(Miller 2013, p. 1445).

Even the most recent research into sexual assault victims’ experiences of the criminal justice system conducted by the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government (ACT Government 2009) only mentions victim impact statements in passing. This is despite the fact that the act of submitting an impact statement meets two of the long-established justice needs of victims of sexual offending, namely, the need to participate in the justice process and the need for voice (see Daly 2014; Lievore 2005; Shapland et al. 1985). It has therefore been argued that ‘completing a VIS or having the opportunity to do so, …[is] essential to a sexually assaulted woman’s therapeutic well-being’ (Miller 2013, p. 1447).

The larger project from which this article was drawn has begun to address this dearth of research, by examining the impact statement experiences of female victims of sexual offending specifically. For this research, we conducted interviews with six women who were victims of male sexual offending in two jurisdictions (South Australia and Tasmania) and 15 justice professionals who work with such victims in four Australian jurisdictions (the ACT, South Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria). Our research was conducted through a feminist and therapeutic jurisprudence lens (see generally Davies 2017; Davies and Bartels forthcoming), with an emphasis on empowering victims of sexual offending, especially those who complete a victim impact statement. Although beyond the scope of the present project, we acknowledge complementary developments in relation to the use of restorative justice in sexual offences (see e.g., Centre for Innovative Justice 2014; ACT Government 2020a).

This article focuses on the specific challenges of communicating with victims about the criminal justice process. Crime victims’ need to be provided with information about the criminal justice system, including information about the progress of their matter, has been long established. As Shapland et al. (1985, p. 78) noted, the ‘absence of information, both at the investigation and at the outcome stage, seems to be felt very keenly by victims’. Since then, researchers have consistently found that one of the greatest needs for victims throughout their justice system experience is to be provided with timely, accessible and accurate information (see e.g., Clark 2010; Wemmers 2011; Laxminarayan et al. 2013; Wedlock and Tapley 2016). Consistent with Tyler’s (2007) theory of procedural justice, ‘victim satisfaction is linked to the amount of information they receive as to the progress of the case’ (Shapland et al. 1985, p. 48). Furthermore, as the Victorian Law Reform Commission has argued, ‘accurate, timely and personalised legal information can help ensure [that] victims have realistic expectations about what the criminal justice system can deliver, and what their role is [in this system]’ (Victorian Law Reform Commission 2014, p. 171). In contrast, a lack of information, and the resulting stress and confusion about the justice process, can re-traumatise victims (Konradi 2007; Wemmers 2011).

Victims’ Right to Information

Emerging in the 1970s, the victims’ rights movement began drawing particular attention to the ‘unenviable and essentially powerless position of victims of sexual crimes’ (O’Connell 2015, p. 243). The movement advocated for the needs of victims that were largely ignored by the justice system, including the need for information, emotional support, and to be heard, compensated and acknowledged (see, e.g., Hoyle and Zedner 2007). By the 1980s, the goals of the movement shifted toward establishing formal rights for victims in the criminal justice system. Legislatures in some Australian jurisdictions responded quickly. For example, in 1981, South Australia established a Committee of Inquiry into Victims of Crime (O’Connell 2015). By 1985, the United Nations General Assembly had resolved to ‘adopt and implement the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power’ (the Declaration) (Mossman 2012, p. 3). The Declaration recognised victims’ need to be:

- Treated with compassion and respect;

- Informed of their role within the justice system, the progress of the proceedings, and of the disposition of their cases;

- Have their views presented and considered at appropriate stages of the proceedings (United Nations 1985).

Since then, victims’ rights instruments have been introduced in Australia and other jurisdictions worldwide (for a comparison between the United Kingdom and United States (US), see Manikis 2019). These instruments reflect many of the United Nations Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime, such as victims’ right to receive information about their case as it progresses through the justice system.

In Australia, there are eight substantive legislative frameworks across six states (New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (Qld), South Australia (SA), Tasmania (Tas), Victoria (Vic), Western Australia (WA)) and two territories (ACT and Northern Territory (NT)) that deal with most sexual offences. There is also a federal legislative framework, but this deals with different types of offences and federal matters only account for 2% of all Australian offences. The importance of providing information to victims is reflected in current victims’ rights legislation and charters around Australia. Most provide that a victim has the right to receive information about trial processes generally (see Victims of Crime Act 1994 (ACT) s 4(g); Victims of Crime Act 2001 (SA) s 8(1); Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic) s 11(1); Victims of Crime Assistance Act 2009 (Qld) Sch 1AA, Pt 1, Div 2, cl 3; Northern Territory Charter of Victims’ Rights (Northern Territory Government 2019, p. 3); Charter of Rights for Victims of Crime (Tas) s 7). In addition, all jurisdictions provide the right to receive information about the progress of the case itself, such as information about the charges laid, scheduled hearings and outcomes, including decisions made about acceptance of guilty pleas (see Victims of Crime Act 1994 (WA) Sch 1 s 6; Victims of Crime Act 1994 (ACT) ss 4(b), 4(d); Victims of Crime Act 2001 (SA) ss 8(1)(a), (e); Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic) ss 9(a), (c); Victims of Crime Assistance Act 2009 (Qld) Sch 1AA, Pt 1, Div 2, cl 2; Victims’ Rights and Support Act 2013 (NSW) ss 6.5, 6.6; Northern Territory Charter of Victims’ Rights (Northern Territory Government 2019, p. 4); Tasmanian Charter of Rights of Victims of Crime (Tas) 2–4). A summary of victims’ informational rights in Australia is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Victims’ informational rights in Australian legislation and charters.

In this article, we compare the lived experiences of victims with the perceptions of the justice professionals who work with them. Despite the established need of crime victims to be informed throughout the justice process and the existing obligations under Australian victims’ rights regimes, we reveal a significant gap between the information that justice professionals believe they are providing victims and the information that victims recall receiving from the justice professionals involved in their case. We then analyse the international literature to distil effective communication strategies for professionals who work with vulnerable persons and suggest strategies to improve communication with victims of crime, in order to improve victims’ experiences of the criminal justice system overall.

2. Materials and Methods

This research had approval from the University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee (H0014988; for further detail of the ethics approval process, see Davies 2017). Interviews were undertaken with six adult victims of sexual offending and a variety of justice professionals who work with victims, including prosecutors, witness assistance officers, and victim support workers.

2.1. Identifying Victim Participants

The victim participants for this research were chosen on the basis of strict inclusion criteria. The participants were required to be adult female victims of sexual offending that had resulted in a conviction, who

- Were receiving or had received support from a victim support or witness assistance agency;

- Had submitted a victim impact statement during the sentencing process; and

- Had retained a copy of their impact statement and the sentencing remarks for their trial.

The participants were all at least 18 years old at the time that the offending occurred—that is, the research design specifically excluded victims of childhood sexual offending. This category of victim participants was chosen based on research indicating that victim participants do not tend to be negatively affected by participating in research about their trauma, except where that trauma involved childhood sexual abuse (Edwards et al. 2009).

Participants were provided with an information sheet and their informed consent was obtained prior to the interview commencing. The information sheet included the following information:

‘We are inviting you to participate in this research because your support worker has identified you as somebody who has been a victim of a sexual offence, and who has submitted a victim impact statement to court. You can participate in this research even if you did not attend court in person for the trial or the sentencing hearing.’

Participants were advised that their participation in the research was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time. They were provided with the contact details of support services and could choose to have their support worker present during the interview.

The requirement that participants have a copy of their impact statement and sentencing remarks from their matters was to prevent re-traumatisation. It was important that the participants had already read, processed, and understood the sentencing remarks in their case. It would not have been appropriate to ask them to read the remarks for the first time in the lead-up to the interview, because this may have deprived them of the time needed to adequately process the information contained therein.

Having access to copies of the participants’ impact statement and sentencing remarks was also important from the interviewer’s perspective, for two reasons. First, these documents provided a comprehensive overview of each matter, which allowed for triangulation (see Webley 2010). These documents provided background information on both the offending and the effect that the offending had on the victim, allowing the interview to complete an otherwise ‘incomplete picture.’ Secondly, possession of the documents ensured that the interviewer was fully informed of the circumstances of the offending prior to the interview, which obviated the need to ask for any information on that subject from the victim participants.

2.2. Recruiting Victim Participants

Victim participants were recruited with the assistance of victim support and witness assistance workers from various agencies. Each agency was contacted to discuss the research and ascertain if they would have the capacity and interest to assist in identifying potential participants. The agencies were also asked to make a suitable space available for the interviews, to ensure that the interviews took place in a private, quiet environment that was familiar to the victim participants. Each agency was also asked to make a support worker available during the interview, if requested by the victim participant. Arrangements were made with at least one agency in each research jurisdiction to provide the required assistance.

Despite the commitment of each agency, a number of difficulties arose in recruiting victim participants. These difficulties stemmed from the strict inclusion criteria, which were designed to protect victim participants, but consequently limited the number of potential interview participants who could be identified by the victim services agencies.

Unfortunately, the criteria prevented the recruitment of any victim participants in Victoria. The assisting agency was unable to locate potential participants who had received a copy of the sentencing remarks from their case, as it is not their practice to obtain a copy of the remarks relating to the victims they counsel. Nor is it normal practice for the Office of Public Prosecutions (OPP) in Victoria to provide victims with a copy of the remarks, unlike in Tasmania and South Australia, where this is standard practice. Furthermore, a large number of sentencing remarks in Victoria are not published online, which prevented easy access to the transcripts from alternative sources.

It emerged that it was also not possible to arrange interviews with victim participants from the ACT. Victim Support ACT advised that this was because adult victims of sexual offending do not tend to remain in the ACT following a criminal trial. While the ACT support service offered to recruit interstate victims for telephone interviews, it was decided that this would not be appropriate. The interview design required that interviewees have the option of the presence of a victim support worker, which would have been very difficult to arrange with an interstate telephone interview.

Consequently, victim interviews were able to be conducted only in South Australia and Tasmania. As a result, only six victim interviews were undertaken.

2.3. Recruiting Justice Professionals

To supplement the data collection, 15 justice professionals were interviewed across the four research jurisdictions, resulting in 21 interviews in total.

Justice professional participants were recruited through direct contact with the agencies for which they worked. Senior managers from each agency were contacted by telephone and asked to seek expressions of interest from staff willing to participate in the research. Interviews were sought with:

- Prosecutors, who work with victims in the conduct of prosecuting defendants (n = 3);

- Witness assistance officers, who work to support victims from within a prosecuting agency (n = 5);

- Victim support workers, who work to support victims, but who do not work for a prosecuting agency (n = 7).

2.4. Conducting and Analysing the Interviews

Victim participants were asked about their experience of completing and presenting a victim impact statement, as well as the process of participating in a sentencing hearing. This included discussion of the support they received from various agencies prior to and during the court hearing. Victim participants were also asked to share their feelings about the way they were acknowledged by the judicial officer in court.

Justice professionals were asked thematically similar questions, which included the type of support that they provide to victims prior to and during trial, and their opinions on the effectiveness of the impact statement processes in their jurisdiction. They were also asked about their views on how victims tend to be acknowledged by judicial officers in the courtroom.

The interviews began in September 2015 and were completed in June 2016. As they progressed, it became increasingly evident from the victim interviews that there were pervasive problems around receiving information arising in each victim’s case. Because of these problems, the interview questions were refined in early 2016 to ask victim interviewees about receiving information during the criminal process and justice professional interviewees about their provision of such information. These issues are the focus of the present article.

The interviews ranged in length from 17 to 105 min, with an average length of 48 min. The transcripts totalled 91,735 words. The interview transcripts were imported into and systematically coded, using the qualitative analysis software NVIVO (Version 11).

3. Results

Table 2 sets out some information about the six courageous women we interviewed for this research.

Table 2.

Experiences of the victims interviewed.

As mentioned above, victims’ need to be provided with timely information about developments in their case as it progresses through the criminal justice system is long-established (see Shapland et al. 1985). Yet, despite widespread academic appreciation of the need to keep victims informed throughout the justice process and the existing obligations under Australian victims’ rights regimes detailed above, the victims of sexual offending we interviewed reported not knowing or understanding some or all of the details of the criminal justice process. This included not being kept informed about the progress of their matter and being unaware of the sentencing process. The following quotes demonstrate that the interviewed victims’ need for information was not met by the justice professionals who worked with them:

‘Being more in the loop would be something that I would [have preferred]… I felt like I was told just “be here at this time, this is what is happening”, while all this stuff was happening in the background, and that was the stuff I wanted to know.’(August, South Australia)

‘I had no idea what the process was and I would have to ask what was next. They would tell me if I asked, but I had no idea.’(Rachel, Tasmania)

‘Even that he had pleaded guilty, and wasn’t trying to fight the charge, I wasn’t told for a while. I thought I was still potentially going to trial for quite a while…there were a few holes in the system that meant I was kept out of the loop.’(Laura, South Australia)

Laura’s case, in which she ‘wasn’t told for a while’ that the offender had pleaded guilty, is a particularly alarming example of the failure to keep victims informed in a timely fashion. Timeliness, as noted above, is an important aspect of victims’ need for information. Yet a lack of timely information placed two of the victims we interviewed in a position where they felt obliged to attend each court hearing, in order to remain informed of the progress of their matter. This caused them significant disruption throughout the course of the justice process:

‘Had I not made the decision to go to every court hearing, [the justice process] would not have worked for me. Because I wouldn’t have had the information I was wanting and when I did get it, it would have been weeks and weeks down the track. It worked for me, because I was there for every step of the process and I therefore knew what was happening as it happened. It got to the point when Witness Assistance would be ringing me and asking me for an update on what was happening.’(Philippa, South Australia)

‘I attended until the end [of the sentencing process], merely to be kept thoroughly in the loop, because the time lapse and wait between hearings until the subsequent court date following adjournments, of sometimes weeks or months, were unbearable and the feedback that followed was a bare minimum.’(Jessica, South Australia)

Several justice professionals reported being aware of problems around the lack of information provided to victims. For example, Victorian Victim Support Officer Trish said:

‘We hear from people all the time about how they feel that they are invisible throughout the legal process, that they are not communicated with regularly, that they aren’t talked to about the purposes of the different court hearings and they often don’t know whether they are supposed to attend or not. Really basic stuff and they are being left out of the loop.’

It is clear from Trish’s comments that problems around a lack of information are not exclusive to the victims interviewed for this research. Instead, this appears to be a widespread issue (for international examples, see Englebrecht 2011; Iliadis 2020).

During their interviews, many justice professionals indicated that they were aware of the importance of keeping victims informed. When prompted, several shared the approaches they take to ensure that victims are made aware of the justice process. Some of these included:

‘[providing] lots of procedural information and lots of practical information about their involvement, their role. And the rules and the etiquette of the court … It’s really important that they understand their role in court.’(Samuel, Witness Assistance Officer, South Australia)

‘We explain the procedure. For example, where the judge will be, where the jury will be, where counsel will be. We show them the courtroom. We explain examination-in-chief and … cross-examination … and there are witness assistance officers who will take them down and show them the court and will be in regular contact with them.’(Michael, Prosecutor, Tasmania)

It is significant that each of these justice professionals described the importance of explaining the trial process to victims, yet none mentioned the importance of keeping victims informed as the trial progresses. Of all the justice professionals interviewed, only Robert (Witness Assistance Officer, Tasmania) described his efforts to ensure that victims are kept informed on an ongoing basis about the progress of their trials:

‘Normally what we would do is explain to them over the phone when the first appearance is happening in court and that we would get back to them and let them know what the plea is either at the first or second appearance. For an indictable matter, when it comes to the Supreme Court, [we would keep them updated about] what was happening.’

This suggests that some of the justice professionals interviewed may not fully understand that victims’ need for information includes the need for timely and ongoing information about the progress of the matter, as it progresses through the criminal justice system. An example of the gravity of failing to keep a particular victim updated about the progress of a trial was described by Cathy (Victim Support Officer, South Australia), who said:

‘we had the unfortunate experience where a client was in the waiting room and opened up the newspaper and read about what had happened in court for her matter. No one had told her about it’.

Justice professionals therefore need to be aware of the importance of providing victims with information both about the justice process and the progress of the victim’s matter. This may be more easily facilitated through the implementation of a victim-focused automated notification system, which is discussed below.

For some victims, the lack of information they received extended to a lack of information about the nature of the hearing at which their impact statement was presented. Four of the six victims reported not having been advised prior to this hearing about the substance of a sentencing plea in mitigation. That is, they were not informed that the hearing at which their impact statement would be presented would otherwise be largely offender-focused. This might include favourable submissions about the offender, including, for example, information about the offender’s good character or community involvement.

Victims August, Philippa, and Laura (all from South Australia) and Rachel (from Tasmania) did not recall being informed about this process at all. Consequently, Laura felt very uncomfortable during the hearing. She explained:

‘It would have been good if someone had said, “don’t take it to heart. This is the norm. This is what happens”. Afterward, when I had said “I feel bad after hearing [the plea in mitigation]”, the detective said to me, “that’s just what they do; that’s what his lawyers are paid to do”. There wasn’t any warning about it. The court process was all very new to me and not well explained at all.’

This is another example of an unsatisfactory outcome for victims, stemming from a lack of information. August, Philippa, Laura and Rachel should have been informed prior to the hearing of the nature of a plea in mitigation. This would have prepared them for the hearing and could have alleviated the distress described by Laura.

Significantly, justice professionals from all of the four jurisdictions in which we conducted our research spoke of the importance of ensuring that victims are adequately prepared for the content of the offender’s submissions in mitigation at sentencing. Two Victim Support Officers particularly noted the distress victims may feel upon hearing these submissions and explained the importance of preparing them for the hearing. As Colette, from Victoria, noted:

‘[A plea in mitigation] is really confronting … [Victims] often will have in their mind that they are going to hear his sentence, but not factoring in how distressing it can be to hear people get up and speak of his good character. That’s something I would prepare them for. I would [explain] it’s just part of the court process … I have had clients feel distressed listening to it, so if someone wasn’t prepared for it, it would be really distressing.’

Other justice professionals also noted how unfair such submissions can feel to victims and consequently emphasised the importance of ensuring they are prepared for the type of submissions that may be made by the defence:

‘If they are going to attend [sentencing], I like to make sure that they know that a lot of it will be about the offender. Some victims go, not realising that they might do character references or they might talk about what a great person the offender is. I think that’s really hard for victims to hear those things.’(Suzanna, Victim Support Officer, ACT)

Many of the justice professionals revealed an awareness of the importance of informing victims about the plea in mitigation and demonstrated how carefully they ensure that victims are educated about this subject. Yet, most of the interviewed victims reported not receiving this information. Accordingly, there appears to be a disconnect between the information that justice professionals and victims believe that victims are receiving.

This article proceeds upon the assumption that both victims and justice professionals are accurately reporting their experiences of information provision. That is, it assumes that justice professionals do attempt to communicate relevant information to victims, but that victims do not actually receive some or all of this information (or do not recall receiving it, which suggests that it is not communicated in a way that they are able to take on board). On that assumption, it explores two significant issues that may act as barriers between justice professionals’ communication of information and victims’ receipt of that information. The first of these barriers is the current lack of clarity as to who is responsible for communicating certain types of information to victims, which may explain why victims appear to receive only some of the information to which they are entitled. The second barrier is the problematic approaches that professionals may take when communicating with victims. This may explain why the information that justice professionals believe they are sharing with victims may not be wholly, or even partly, understood by the intended recipients.

Barriers to Effective Communication with Victims of Crime

In most Australian jurisdictions, including the two in which we conducted the victim interviews, victims’ right to information only exists if the victim actively requests that information from the relevant agency. For example, s8(1) of the Victims of Crime Act 2001 (SA) states that the ‘victim should be informed, on request’ about information such as the progress of the investigation and the charges laid. The NSW, Queensland, Tasmanian, and Western Australian instruments are all expressed in similar terms; that is, the onus in these jurisdictions is on the victim to contact the police, witness assistance or DPP to obtain the required information, rather than the obligation resting with those agencies to keep the victim informed.

In contrast, the Victorian legislation states that ‘[a]n investigatory agency is to inform a victim, at reasonable intervals, about the progress of an investigation into a criminal offence’ (Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic) s8(1)) and that ‘[t]he prosecuting agency is to give a victim, as soon as reasonably practicable, the [relevant] information’ (s9) (the key prosecuting agency in Victoria is the OPP). The ACT currently places the obligation to keep the victim informed on the police and prosecution agency, but recent legislative reforms will change this. Under s15F(1) of the Victims Rights Legislation Amendment Act 2020 (ACT), which is scheduled to come into effect in January 2021, the police and/or DPP must:

within a reasonable period before a victim of an offence would be able to make a victim impact statement, tell the victim the following:

- (a)

- Who may make a victim impact statement;

- (b)

- That a victim impact statement may be made orally or in writing;

- (c)

- What information a victim impact statement must and may include:

- (d)

- how a victim impact statement may be used in court during a proceeding, including that—

- (i)

- A copy of the victim impact statement will be given to the offender;

- (ii)

- The victim may be cross-examined about the contents of the victim impact statement;

- (iii)

- The court must consider the victim impact statement in deciding how the offender should be sentenced.

This legislation also expanded victims’ rights in the ACT in a range of other ways and has been described by the current Victims of Crime Commissioner as a ‘a crucial opportunity to … better uphold the rights and interests of those affected by crime’ (Yates 2020, n.p.).

Our interviews in South Australia and Tasmania suggest that the victims’ rights instruments in those jurisdictions are operating entirely in accordance with their provisions; that is, the interviewed victims were not apprised of the progress of their case unless they contacted the appropriate agency to seek information. These provisions are therefore problematic, because of the negative consequences that arise for victims when they are not kept appropriately informed. These consequences, which were explored above, were summarised by Victorian Victim Support Officer Collette: ‘if the person is left hanging, and there is no communication and no word of what is happening, people can get to highly traumatised states’.

While it is possible that some victims may be aware that it is their responsibility to request information and may also possess the capacity to seek it from the relevant agencies, it is equally possible that victims may not know that the onus is on them to seek such information and/or they may not possess the resilience or capacity to follow this up. This view is supported by Victorian Victim Support Officer Trish, who argued:

‘I think it’s unfair to expect someone who is traumatised and going through the pressure of a court case to be able to advocate for themselves or even to be informed enough…to do that. I think that expectation is unrealistic and unfair.’

This was certainly the experience of some of the victims interviewed, such as Eve, who said:

‘If I have learned anything from this process, it’s that nobody actually cares about the victim. I got a phone call out of the blue 15 months after he raped me, saying, “can you come to the DPP’s office.” No one got in contact with me after it happened…nobody did any follow-up [with me]…Throughout the 15 months, I had to make phone calls to follow up, and I was always put through to different people, because the others were on holidays or whatever. So, it was just bringing it all back every few months that I rang up to ask what was going on’(Victim, Tasmania).

In her high-profile memoir about her experience of child sexual assault, lawyer, journalist and advocate Bri Lee (2018) documented a similar experience about ‘standing up, speaking out and fighting back’ against the man who sexually assaulted her. This echoes Eve’s experience and confirms that a lack of communication with the victim can result in their re-traumatisation. This is particularly unsatisfactory, given that victims’ rights regimes and victim impact statements were introduced as part of reforms intended to reduce the re-traumatisation of victims of sexual offending by the criminal justice process.

Accordingly, it is problematic that victims’ rights regimes in some jurisdictions place the obligation on the victim to seek information about the progress of the investigation and trial, rather than placing the onus to provide that information on the police or prosecution agency. As Trish argued, it is not reasonable or fair to expect victims, who are likely to be in a traumatised state, to take responsibility for following up with various agencies to determine the progress of their matters. It is also not satisfactory that an instrument that purports to grant informational rights to potentially vulnerable and traumatised victims is only activated in cases where victims have the personal capacity and resilience to follow up on that right themselves.

We recommend that, in order to increase the level of information provided to victims throughout the justice process, there should be consistency across Australian victims’ rights instruments. This would require most jurisdictions to remove the responsibility for obtaining information about the progress of the criminal investigation and trial process from the victim and instead place the onus to provide that information on the relevant agency. The recent reforms in the ACT are a step in the right direction. Reforms of this nature should also be supported by training to ensure that agencies are aware of their responsibility to keep victims informed throughout the entire justice process, which could begin to alleviate the problem of victims feeling ‘out of the loop’.

As the quote from Trish above indicates, however, even where provisions of this nature exist, as in Victoria, victims may not receive adequate information and continue to feel left out of the loop. This suggests that there may be problems with the implementation of informational rights, even in jurisdictions where the legislation places the onus on agencies to keep victims informed. This is also supported by the Victorian Law Reform Commission, which was told ‘by a parent whose child had been killed, that she was not informed of sentencing hearing dates and was therefore not able to attend’ (Victorian Law Reform Commission 2016, p. 107). This suggests that justice professionals’ approaches to communication with victims of crime may be ineffective.

Our interviews demonstrate both that the justice professionals were aware of the need to provide sufficient information to victims about court processes (including sentencing hearings) and that the victims did not recall being told this type of information. It may be that the interviewed victims were provided with this information, but did not recall it because they did not fully understand it.

Our research suggests that issues of effective communication have rarely been explored in the context of justice professionals working with victims (especially victims of sexual and other gendered violence) and little has been written on practical communication strategies in this area. In fact, many communication texts ‘devote the majority of their content to specific communication issues and give correspondingly less attention to core communication skills’ (Silverman et al. 2013, p. 323; emphasis added). For example, Lewis and Jaramillo (2008) identified many barriers that can affect communication between victims and service providers, but provided few explicit strategies to overcome them. Similarly, a publication by the United States Office for Victims of Crime (2005) outlined a list of barriers that can prevent effective communication with victims, without offering practical solutions to overcome these problems.

In contrast, medical professionals have long recognised the vast communication difficulties that can arise between doctors and patients. The medical literature is therefore a valuable resource for applied communication skills training. Silverman et al. (2013) consolidated a large number of studies on the frequent problems that arise in communication in medical practice. They reported that doctors tend to give sparse information to their patients, often underestimating the amount of information patients actually want. Furthermore, patients frequently do not understand the language that doctors use, including technical language and shorthand. Consequently, patients tend not to understand or recall all of the information imparted by their doctors. This can be compounded by the ‘highly emotional nature of illness [that may impede] rational communication and understanding’ (p. 162).

We believe that the same problems may affect communication between justice professionals and victims. This is likely to be particularly the case in respect of sexual offences, which may leave victims particularly vulnerable and are often subject to ‘he said, she said’ evidentiary issues. It is arguable that prosecutors and witness assistance and victim support officers share information with victims about justice processes that may not be fully understood by the victims. This may be because the information is sparse, victims may not possess a fundamental understanding of the justice process and/or they may not understand legal jargon or shorthand, including acronyms such as ‘DPP’ or ‘OPP’. This argument is supported by Hargie, who noted that, in the legal context, ‘problems of comprehension [arise] with vocabulary and the technical meaning of some terms that can be at odds with everyday interpretations’ (Hargie 2011, p. 211). It is also borne out by Rachel, one of the victims in our study, who reported ‘not knowing who the DPP was’. She stated that ‘the prosecutor and witness assistance…deal with these situations, these words, these people, these documents, on a daily basis, but I had no idea. They were saying all these words and I just didn’t know’. Similarly, Laura explained:

‘I understand that they are busy. But I think it’s the little things. They assume that others understand the system enough to understand what is going to happen next. It’s easy to assume that if you have that knowledge, that other people will have the same knowledge of the system and how it works. I have a decent amount of common sense, but there were things that were worded in ways that weren’t clear and they assumed I would understand that if one thing happened, that other things would follow.’

These communication difficulties may be exacerbated by the psychological sequelae experienced by victims of crime, including ‘difficulties in processing information … poor concentration, difficulty with memory retrieval…and a decreased ability to consider long range implications of events’ (Reyes et al. 2008, p. 176). Tasmanian victim Rachel also reflected on these difficulties: ‘I didn’t understand a lot and at the time was overwhelmed … I was in a frame of mind where they could have talked to me all day, and I wouldn’t have taken that in’. Consequently, as Ashworth has noted, ‘being told is not the same as being made to understand’ (Ashworth 1998, p. 64).

4. Discussion: Evidence-Based Strategies for Communicating with Victims

Applying the research of Silverman et al. (2013) to the criminal justice context, in this section, we explore a range of evidence-based solutions to address the communication challenges between professionals and victims we identified in the previous section. These solutions are designed to ensure that appropriate levels of information are provided to victims and can be properly processed and retained by them.

As set out in Table 1 above, victims in Australia have the right to receive information about trial processes in a general sense, as well as information about the progress of their case, including information about the charges laid and scheduled hearings, and outcomes, including the decisions made concerning acceptance of a guilty plea. In essence, this means that victims are entitled to information about how the criminal justice system operates, starting with the role of the prosecution agency, defence lawyer and judge. They must be informed prior to each court date of what the hearing might entail, followed by the outcome of hearings, as they occur. They must also be informed about their right to submit a victim impact statement, including information about how and when it might be used.

A consideration throughout this should be whether the information is communicated to victims in a form that can be easily understood and processed, both at the time of the communication and later. Silverman et al. (2013) have provided a number of strategies to assist medical professionals to impart comprehensible information to patients. We suggest that these strategies are equally applicable to justice professionals working with victims and will help to provide accessible communication of information verbally, as well as effectively conveying information using visual methods.

4.1. Effective Verbal Communication

Silverman et al. (2013) have recommended a number of strategies to ensure that verbal information is conveyed effectively. These require professionals to:

- Assess the recipient’s starting point, prior to giving information, by determining the amount of information or knowledge the recipient already possesses in relation to the subject matter, prior to providing any further information;

- Give information in small, ‘assimilable chunks’ (p. 24). The professional must ensure that information is given in small amounts, to enable the recipient to hear and process each piece of information before further information is provided;

- Check the recipient has understood the small chunk of information and use their response as a guide to how to proceed before providing any further information;

- Repeat information if the recipient has not understood;

- Reduce or eliminate the use of jargon;

- Ask the recipient what other information might be helpful.

Combined, these strategies should ensure that victims are able to comprehend the information presented to them verbally. For example, South Australian victim Laura complained that the justice professionals she encountered seemed to ‘assume that others understand the system enough to understand what is going to happen next’. This situation could have been avoided if the first strategy listed above had been used. By determining Laura’s prior understanding of the justice system, the professionals who worked with her could have avoided the assumption that she understood more than she did and, consequently, could have provided Laura with appropriate levels of introductory information. Furthermore, by avoiding the use of jargon, the justice professionals who worked with Rachel could have avoided the confusion that she experienced when ‘they were saying all these words and I just didn’t know [what they meant]’.

Consequently, we recommend that, based on the above-described strategies, verbal communication skills training should be conducted with justice professionals to improve their communication when working with victims of crime.

4.2. Effective Visual Communication

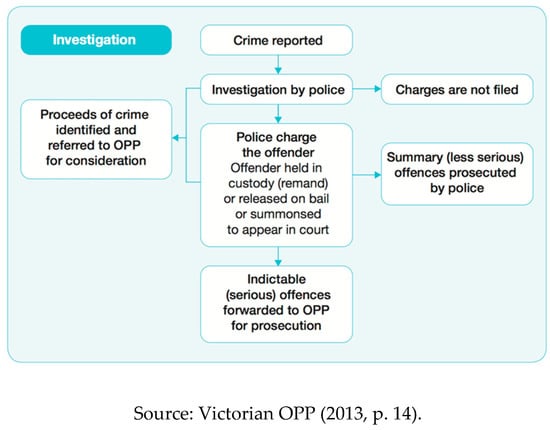

In addition, Silverman et al. (2013; see also Hargie 2011) recommended using visual methods of conveying information to aid the recipient’s recall and understanding. Many victim support agencies and prosecution offices already publish information booklets designed for victims. However, these vary in their accessibility and may not serve as effective aids to victims’ understanding. For example, the booklet Information for Victims of Crime: Treatment, Impact and Access to the Justice System is published by the South Australian Commissioner for Victims’ Rights (2014). This booklet is very comprehensive, but potentially overwhelming; it was at 84 pages long at the time of our interviews, although the version on the website in 2020 appeared to have been reduced to 74 pages. When reflecting on the length of such booklets, Rose (Prosecutor, Victoria) was sceptical of their utility, commenting that ‘for example, 80 pages, that’s very big. Ours [the Victorian booklet] is quite compact and small … I think you have to assume that although people are sent that information, that they don’t really read it’.

A shorter booklet that is less comprehensive, but provides clear and specific information about each stage in the court process, would arguably serve as a greater aid to victims’ understanding of the justice system generally. This view is supported by Laura’s experience:

‘They gave me an information sheet and booklets about the legal process. [These explained] what court is for what sort of offence, and about negotiations and sentencing. But I would have liked a little side bar of minor details about what happens there, because those are the things I didn’t know … Like where to sit or where the offender is sitting or who is going to go first. Those little details that add to the stress. I would have liked to be able to mentally prepare myself for it and remain as calm as I could. So, I think that’s what is lacking and is probably not hard to fix, because they are very small details.’(Victim, South Australia)

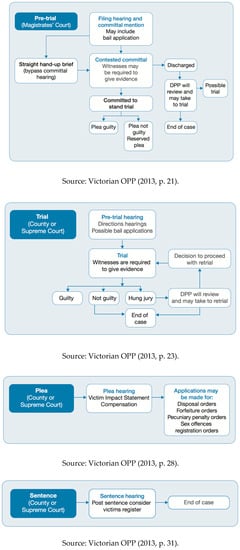

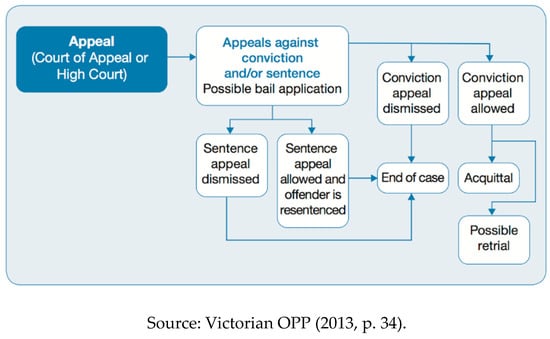

Her comment is significant, because the South Australian booklet does in fact contain much of the information that Laura desired. The booklet even contains a diagram of both the lower and higher courts, to illustrate the locations of the parties in the room. However, as Prosecutor Rose from Victoria pointed out, it is unlikely that victims would read a booklet of that length. Accordingly, a shorter and more concise booklet would be preferable. The Victorian OPP (2013) has its own booklet, Pathways to Justice: A Guide to the Victorian Court System for Victims and Witnesses of Serious Crime. As set out above, Rose, a Victorian prosecutor, described this as ‘quite compact’. However, at 50 pages, it may also be overwhelming in length. It is preferable that victims be provided with condensed versions of these booklets and the option of receiving a copy of the longer publication if desired. The need for ‘succinct, victim friendly and accessible’ materials for victims was recently accepted by the NSW Government (2018, p. 13) in its response to recommendations by the NSW Sentencing Council (2018) on victims’ involvement in sentencing.

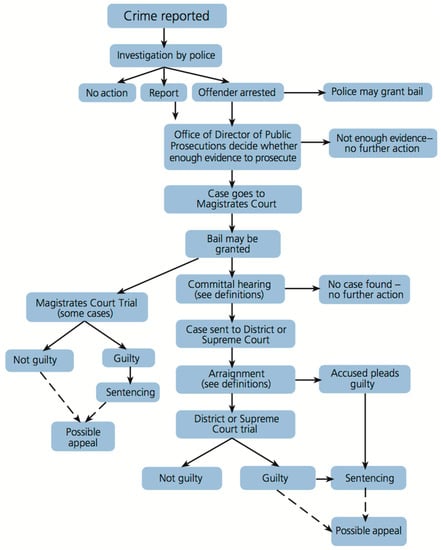

Of key importance in the development of a condensed booklet is the presentation of material in flowcharts, as included the current South Australian and Victorian booklets. A flowchart is ideal, because it assists with visually communicating information, in accordance with Silverman, Kurtz and Draper’s recommendations. The South Australian and Victorian flowcharts are concise, but contain sufficient detail to present the complete course of a criminal prosecution. The justice professionals we interviewed spoke highly of the Victorian flowchart. For example, Victim Support Officer Collette commented that she frequently uses the Pathways to Justice booklet (Victorian OPP 2013), because it ‘has a really good flowchart in it’.

We have set out the flowcharts in the Victorian and South Australian booklets below in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. They are undoubtedly a useful guide for lay people about the various stages of the criminal justice process. However, they are at risk of being overlooked by victims, due to the overall length of the publications in which they are published. Therefore, the inclusion of the chart and other vital information, such as legal definitions, in a condensed booklet is likely to be of more use to victims.

Figure 1.

South Australian Flowchart—The Criminal Justice System for Adult Offenders. Source: South Australian Commissioner for Victims’ Rights (2014, p. 20).

Figure 2.

Victorian Flowcharts on Criminal Justice Processes.

There is also some information for victims in the ACT contained in the Australian Federal Police (2013) Pocketbook Guide for Victims of Crime, although the information on court processes appears alongside information on issues such as family violence and home and vehicle security. The ACT Government’s Victim Support website includes information that acknowledges that ‘[t]he Court process can be very confusing and intimidating for people who have been a victim of crime’ (ACT Government 2020b, n.p.). The website also provides information about the different court levels in the ACT (ACT Government 2020c), the role of the prosecution (ACT Government 2020d) and sentencing (ACT Government 2020e), but does not include a visual explanation of the kind we suggest. We note that Tasmania does not have an equivalent booklet or chart. When asked if a flowchart would have been useful to her, Eve said:

‘Yes. To know anything would have been helpful … I think as soon as you say that you want [the defendant] charged, they should give the flowchart to you. And then you would know how long it might take and when they might contact you next, and what would happen at court.’

Similarly, Rachel (Victim, Tasmania) said that ‘a summary would have been helpful to actually know why I was doing what I was doing, and what they were going to do with the information I was giving. That would have been quite helpful’.

Accordingly, we recommend that similar charts be prepared for the ACT and Tasmania and all other jurisdictions in Australia and elsewhere that have similar frameworks, in order to ensure their communication with victims is accessible and effective. This information should be included in short informational booklets that briefly explain court processes and define key terms. To be of most practical use, these booklets should also contain adequate space for victims to take notes and write questions they may wish to ask of support services or prosecutors.

4.3. Automated Victim Notification Systems

One further strategy for providing information that may complement the approaches proposed above is the introduction of automated systems that provide victims with brief details of upcoming hearings and outcomes. In response to problems around crime victims’ receipt of information about court hearings and outcomes, automated methods for communicating with victims have been developed in the US. These systems have been rolled out over nearly 30 years and were operating in 47 states by 2015 (Irazola et al. 2015). These systems provide victims with the opportunity to sign up to receive notifications about scheduled court hearings and outcomes via a range of mechanisms, including telephone, email and text message (United States Department of Justice 2020).

One of our study jurisdictions has also considered this approach, with a recent ACT Government options paper on victims of crime noting that:

New Zealand recently introduced a similar text messaging system. England and Wales have introduced a ‘track my crime’ system where people log in and opt-in to receive alerts, and in Canada victims have access to a secure website to obtain information about offenders who harmed them .(ACT Government 2018, p. 21)

It was suggested that, although privacy issues need to be considered, such a system ‘would benefit victims and reduce the burden on agencies to provide this information’ (ACT Government 2018, p. 22).

While there is little literature on the operation and effectiveness of such systems, Irazola et al. (2015) found that victims who subscribed to these systems indicated that the notifications helped them to feel more empowered and safe and made them want to be more involved in their case (for discussion, see also Healy 2019). Accordingly, we recommend that similar systems be considered in the Australian context. While this would not alleviate the problems surrounding victims’ lack of understanding of the criminal justice system and sentencing more generally, they could help agencies to fulfil their legislative obligations to provide victims with regular and timely information.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented key insights from interviews with six Australian women who were victims of sexual offending and had their matter proceed through the criminal justice system to sentencing, supplemented by interviews with 15 justice professionals who work with victims of crime. In interviews with both victims and justice professionals, we identified communication difficulties that seem to act as a barrier to justice professionals’ fulfilment of their obligation to keep victims appropriately informed of the justice process, including the sentencing process. Trish (Victim Support Officer, Victoria) summarised the problem clearly:

‘[Victims] feel uninformed, they don’t understand the process, they feel out of control within the process in terms of how long it takes, what happens and what their role is within it. I think it’s a real problem. I think it re-traumatises the vast majority of victims who have experienced sexual assault, by the nature of how the process operates.’

Several justice professionals detailed the type of information they usually provide to victims throughout the justice process, yet each of the victims interviewed reported not receiving at least some of the information they were entitled to. This suggests that there is a disjuncture between the information that justice professionals believe that victims are receiving and the information victims recall being told.

The solutions proposed in this article are based on the assumption that both victims and justice professionals accurately reported their experiences of information provision. On this basis, we identified two significant problems that may act as barriers between justice professionals’ communication of information and victims’ receipt of that information. The first is the lack of clarity as to who is responsible for the communication of certain types of information to victims, which may explain why they receive only some of the information to which they are entitled. In response to this problem, we recommended that the victims’ rights regimes in NSW, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia be amended to remove the responsibility for obtaining information about the criminal investigation and trial process from the victim and instead place the onus to provide that information on the relevant agency, as is the case in the ACT, Northern Territory and Victoria. We also recommended piloting automated notification systems, which could further assist agencies to fulfil their obligations to provide victims with relevant information on an ongoing basis.

The second identified barrier relates to the problems that may arise when professionals attempt to communicate with victims. This barrier may explain why the information that justice professionals believe they are providing to victims may not be wholly, or even partly, understood by the recipients of that information. Based on Silverman et al.’s (2013) recommendations, we made suggestions for strategies that might improve verbal communication. Together, these strategies should ensure that victims are able to better comprehend and remember the information presented to them verbally. Based on these strategies, verbal communication skills training should be conducted with justice professionals in order to improve their communication with victims of crime.

We also recommended that victims be provided with condensed versions of the existing victim information booklets in South Australia and Victoria. Similar—but shorter—booklets should be developed in all Australian jurisdictions that do not currently offer victims this type of information. This would alleviate the problem identified by one of the victims we interviewed, Rachel:

‘If someone could have told me ‘this is probably what is going to happen, this is probably the path that it’s going to take’, that would have been a really good heads-up … getting my head around that sort of stuff is a task … A cheat sheet would have been great.’

There has been increasing recognition in recent decades that victims, especially victims of sexual offending, may be retraumatised by the criminal justice process. However, there is also increasing recognition that some victims wish to speak about their experiences and may find this therapeutic. For example, the victim in the ‘Stanford rape’ case, whose anonymous victim impact statement received significant public attention (see, e.g., De Léon 2019), subsequently published a powerful memoir on her experience (Miller 2019). In addition, the ‘Let Her Speak’ campaign in Tasmania has been seeking to overturn laws in Tasmania and elsewhere in Australia that preclude sexual assault survivors from using their real name in the media unless a court makes a special exemption order (Funnell 2019). We hope that the steps proposed in this article will also go some way to supporting and empowering victims, like the brave women we interviewed for this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D. methodology, R.D.; software, R.D.; validation, R.D.; formal analysis, R.D.; investigation, R.D.; resources, R.D.; data curation, R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.; writing—review and editing, L.B.; supervision, L.B.; project administration, R.D.; funding acquisition, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Tasmania and ACT Victims of Crime Commissioner.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Her Excellency Professor the Honourable Kate Warner AC and Adjunct Professor Terese Henning, who co-supervised the doctoral research on which this paper is based. We also gratefully acknowledge the time and contributions of our interviewees, especially the victims who shared their lived experiences of the justice system.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ACT Government. 2009. A Rollercoaster Ride: Victims of Sexual Assault: Their Experiences With and Views about the Criminal Justice Process in the ACT; Canberra: ACT.

- ACT Government. 2018. Charter of Rights for Victims of Crime: Options Paper; Canberra: ACT Government.

- ACT Government. 2020a. Restorative Justice Empowers Victims of Crime. In Media Release; November 26. Available online: https://www.cmtedd.act.gov.au/open_government/inform/act_government_media_releases/rattenbury/2020/restorative-justice-empowers-victims-of-crime (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- ACT Government. 2020b. Court Process. Available online: https://www.victimsupport.act.gov.au/criminal-justice-system/court-process (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- ACT Government. 2020c. The Courts. Available online: https://www.victimsupport.act.gov.au/criminal-justice-system/court-process/the-courts (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- ACT Government. 2020d. The Role of the Prosecution. Available online: https://www.victimsupport.act.gov.au/criminal-justice-system/court-process/the-role-of-the-prosecution (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- ACT Government. 2020e. Sentencing. Available online: https://www.victimsupport.act.gov.au/criminal-justice-system/court-process/sentencing (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Ashworth, Andrew. 1998. The Criminal Process: An Evaluative Study, 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Federal Police. 2013. Pocketbook Guide for Victims of Crime. Available online: https://police.act.gov.au/sites/default/files/PDF/Victims-of-crime-booklet-September-2013.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Australian Law Reform Commission. 2010. Family Violence—A National Legal Response. Report 114. Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Innovative Justice. 2014. Innovative Justice Responses to Sexual Offending—Pathways to Better Outcomes for Victims, Offenders and the Community. Melbourne: RMIT University. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Haley. 2010. ‘What Is the Justice System Willing to Offer?’ Understanding Sexual Assault Victim/Survivors’ Criminal Justice Needs. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Kathleen. 2014. Reconceptualizing Sexual Victimization and Justice. In Justice for Victims: Perspectives on Rights, Transition and Reconciliation. Edited by Inge Vanfraechem, Antony Pemberton and Felix Mukwiza Ndahinda. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Rhiannon. 2017. Stories of Pervasive Uncertainty: A Victim-focused Analysis of Victim Impact Statements and Sentencing in Sexual Offence Cases. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Rhiannon, and Lorana Bartels. The Use of Victim Impact Statements in Sentencing for Sexual Offences: Stories of Strength. Abingdon: Routledge, Forthcoming.

- De Léon, Concepción. 2019. You Know Emily Doe’s Story. Now Learn Her Name. New York Times. September 4. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/books/chanel-miller-brock-turner-assault-stanford.html (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Du Mont, Janice, Karen-Lee Miller, and Deborah White. 2008. ‘Social Workers’ Perspectives on the Victim Impact Statements in Cases of Sexual Assault in Canada’. Women and Criminal Justice 18: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Katie, Megan Kearns, Karen Calhoun, and Christine Gidycz. 2009. College Women’s Reactions to Sexual Assault Research Participation: Is It Distressing? Psychology of Women Quarterly 33: 225–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englebrecht, Christine. 2011. ‘The Struggle for “Ownership of Conflict”: An Exploration of Victim Participation and Voice in the Criminal Justice System’. Criminal Justice Review 36: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, Edna, Peter Ibarra, and Daniel Downs. 2011. Victim Welfare and Participation Reforms in the United States: A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Perspective. In Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Victim Participation in Justice: International Perspectives. Edited by Edna Erez, Michael Kilchling and Jo-Anne Wemmers. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell, Nina. 2019. ‘Let Her Speak Campaign Aims to Ensure All Victims Can Take Back Their Voices’. ABC News. August 13. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-13/let-her-speak-campaign-tasmania-nt/11405050 (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Hargie, Owen. 2011. Skilled Interpersonal Communication: Research, Theory and Practice, 5th ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, Deirdre. 2019. Exploring Victims’ Interactions with the Criminal Justice System: A Literature Review. Dublin: Irish Department of Justice and Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, Carolyn, and Lucia Zedner. 2007. Victims, Victimization and Criminal Justice. In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Edited by Mike Maguire, Rodney Morgan and Robert Reiner. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iliadis, Mary. 2020. Adversarial Justice and Victims' Rights: Reconceptualising the Role of Sexual Assault Victims. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Irazola, Seri, Erin Williamson, Emily Niedzwiecki, Sara Debus-Sherrill, and Jing Sun. 2015. Keeping Victims Informed: Service Providers’ and Victims’ Experiences Using Automated Notification Systems. Violence and Victims 30: 533–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konradi, Amanda. 2007. Taking the Stand: Rape Survivors and the Prosecution of Rapists. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan, Malini, Mark Bosmans, Robert Porter, and Lorena Sosa. 2013. Victim Satisfaction with Criminal Justice: A Systematic Review. Victims and Offenders 8: 119–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Bri. 2018. Eggshell Skull: A Memoir About Standing Up, Speaking Out and Fighting Back. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Nancy, and Ann Jaramillo. 2008. Communication with Victims and Survivors. Rockville: National Victim Assistance Academy. Available online: https://ce4less.com/Tests/Materials/E055Materials.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Lievore, Denise. 2005. No Longer Silent: A Study of Women’s Help-Seeking Decisions and Service Responses to Sexual Assault. Research Report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. [Google Scholar]

- Manikis, Marie. 2019. Contrasting the Emergence of the Victims’ Movements in the United States and England and Wales. Societies 9: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Chanel. 2019. Know My Name: A Memoir. New York: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Karen-Lee. 2013. Purposing and Repurposing Harms: The Victim Impact Statement and Sexual Assault. Qualitative Health Research 23: 1445–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossman, Elaine. 2012. Victims of Crime in the Adult Criminal Justice System: A Stocktake of the Literature. London: UK Ministry of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Government. 2018. Schedule of Government Response to Recommendations on Victims’ Involvement in Sentencing. Available online: http://www.sentencingcouncil.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Current-projects/Victims/Victims_gov.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- New South Wales Sentencing Council. 2018. Victims’ Involvement in Sentencing—Report; Sydney: New South Wales Sentencing Council.

- Northern Territory Government. 2019. Northern Territory Charter of Victims’ Rights; Darwin: Northern Territory Government.

- O’Connell, Michael. 2015. The Evolution of Victims’ Rights and Services in Australia. In Crime, Victims and Policy: International Contexts, Local Experiences. Edited by Dean Wilson and Stuart Ross. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Gilbert, Jon Elhai, and Julian Ford. 2008. The Encyclopedia of Psychological Trauma. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Shapland, Joanna, Jon Willmore, and Peter Duff. 1985. Victims in the Criminal Justice System. Aldershot: Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Jonathan, Suzanne Kurtz, and Juliet Draper. 2013. Skills for Communicating with Patients, 3rd ed. Oxford: Radcliff Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- South Australian Commissioner for Victims’ Rights. 2014. Information for Victims of Crime: Treatment, Impact and Access to the Justice System; Adelaide: South Australian Commissioner for Victims’ Rights.

- Tyler, Tom. 2007. Procedural Justice and the Courts. Court Review 44: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 1985. Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/victimsofcrimeandabuseofpower.aspx (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- United States Department of Justice. 2020. Victim Notification System. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/criminal-vns/victim-notification-system (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- United States Office for Victims of Crime. 2005. Listen to My Story: Communicating with Victims of Crime. Available online: https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/media/document/listen_to_my_story_vdguide.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Victorian Law Reform Commission. 2014. The Role of Victims of Crime in the Criminal Trial Process: Consultation Paper; Melbourne: Victorian Law Reform Commission.

- Victorian Law Reform Commission. 2016. The Role of Victims of Crime in the Criminal Trial Process: Report; Melbourne: Victorian Law Reform Commission.

- Victorian Office of Public Prosecutions. 2013. Pathways to Justice: A Guide to the Victorian Court System for Victims and Witnesses of Serious Crime. Available online: http://www.opp.vic.gov.au/getdoc/9556d0e4-0d59-4fd3-ac0e-f4f60edf2b97/Pathways-to-justice.aspx (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Webley, Lisa. 2010. Qualitative Approaches to Empirical Legal Research. In Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Edited by Peter Cane and Herbert Kritzer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wedlock, Elaine, and Jacki Tapley. 2016. What Works in Supporting Victims of Crime: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Report for the Victims Commissioner for England and Wales. Available online: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/what-works-in-supporting-victims-of-crime(d3ad0ff3-7f6d-4cc5-8220-1c250c5fe55e).html (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Wemmers, Jo-Anne. 2011. Victims in the Criminal Justice System and Therapeutic Jurisprudence: A Canadian Perspective. In Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Victim Participation in Justice: International Perspectives. Edited by Edna Erez, Michael Kilchling and Jo-Anne Wemmers. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, Heidi. 2020. Opinion: I Am Hoping This is a Turning Point for Victims of Crime. Canberra Times. July 5. Available online: https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6818695/i-am-hoping-this-is-a-turning-point-for-victims-of-crime/ (accessed on 6 July 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).