Abstract

Thailand places a high priority on the gender-specific contexts out of which offending arises and the differential needs of women in the criminal justice system. Despite this, Thailand has the highest female incarceration rate in South East Asia and there has been substantial growth since the 1990s. This increase has been driven by punitive changes in drug law, criminal justice policy/practice which have disproportionately impacted women. As female representation in Thailand’s prisons grows, so does the number of women who return to communities. Thus, one of the challenges facing Thai society is the efficacious re-integration of growing numbers of formally incarcerated women. However, what is known about re-entry comes almost exclusively from studies of prisoners (usually men) returning home in western societies. Re-integration does not occur in a vacuum. Supporting women post-release necessitates knowledge of their pathways to, experiences of, and journeys out of prison. Utilising in-depth interviews with (n = 80) imprisoned/formally incarcerated women and focus groups with (n = 16) correctional staff, this paper reports findings from the first comprehensive study of women’s re-integration expectations and experiences in Thailand. Findings showed that women had multifaceted and intersectional needs which directed their pathways into, during, and out of prison.

1. Introduction

Thailand imprisons more of its citizens than any other country in South East Asia. It has the highest female incarceration rate in the region, and prisoner numbers have grown rapidly since the 1990s. Principally, this progression has been compelled by changes in drug law, policy, and criminal justice practice. The government of Thailand has taken, and continues to take, a punitive approach to illicit drugs (particularly methamphetamine). Predictably, this has caused prison populations to escalate. Drug offenders are significantly over-represented, and punitiveness has disproportionately impacted women. Compared to men, drug offenders constitute a higher proportion of the female prison population (Jeffries 2014; Jeffries and Chuenurah 2016). For example, Jeffries and Chuenurah’s (2016, p. 96) study of imprisonment trends in Thailand from 2003 to 2013 found that drug offending was the most substantial driver behind prison population changes, and “in every year drug offenders constituted the largest proportion of sentenced prisoners regardless of sex. However, compared to men, far higher proportions of the female sentenced prison population were incarcerated for a drug offence over the decade (72.1–89.5% cf. 45.4–65.4%).”

As women’s representation in Thailand’s prisons grow, so do the numbers of women re-entering communities. Thus, a challenge confronting Thailand is the effective re-integration of mounting numbers of formally incarcerated women. However, to date, there have been no assessments of women’s re-entry in Thailand. Current knowledge of re-integration largely comes from studies conducted with prisoners (usually men) going home in western countries. This is an oversight. Understanding the expectations and experiences of women returning to society in Thailand is crucial to facilitate their successful re-entry.

Re-entry does not occur in a vacuum. Supporting women post-release necessitates knowledge of their pathways to, experiences of, and journeys out of prison. Utilising the voices of women (imprisoned and formally imprisoned) and correctional staff, this paper reports findings from the first comprehensive study of women’s experiences of drug offending/criminalisation, imprisonment, and re-entry in Thailand. The aims of this research are to understand the expectations and experiences (including needs, challenges, and successes) of women re-entering Thai society post-imprisonment.

2. Review of the Extant Research

Gender structures the social world and, as such, impacts women’s experiences of offending/criminalisation, imprisonment, and re-entry. Studies illustrate that female prisoners and those returning home constitute special populations. Formally incarcerated women share similar needs to their male counterparts, but their experiences are often unique and differ in significant ways. This creates challenges during women’s return to society (Covington and Bloom 2007).

Supporting the successful re-integration of formally incarcerated women firstly requires knowledge of their pathways to, and experiences of, incarceration. A now widespread corpus of research demonstrates that women’s offending/criminalisation is connected to a clustering of interrelated and interconnected circumstances that constrain and mould their behaviours and life choices. These circumstances comprise victimisation and trauma, disordered family lives, other adverse life experiences, deviant friendships, addiction (and other mental health problems), male influence and control, limited education, poverty, and familial caretaking responsibilities (Daly 1994; Jeffries and Chuenurah 2018; Jeffries and Chuenurah 2019; Jeffries et al. 2019a; Jeffries et al. 2019b; Owen et al. 2017).

Although men’s pathways to prison are characterised by many of these same factors, women experience these aspects differently, and perhaps more acutely, than men. For example, while victimisation and associated trauma are linked to both female and male imprisonment trajectories, incarcerated women tend to be victimised earlier in their lives, in multiple ways (e.g., child abuse and domestic violence), and more frequently. As a result, victimisation appears to be an experience that carries more weight in shaping women’s pathways to prison (Jeffries et al. 2019b; Owen et al. 2017).

Victimisation is linked to women’s offending in both direct and indirect ways. For example, women may be threatened or coerced into offending by violent romantic partners, and the financial abuse which often characterises domestically violent relationships can limit women’s financial means, leading them into crime out of economic necessity. Domestic violence during teen years, and abuse within the familial home, can also amplify the chances of poverty and concomitant offending in interconnected and interrelated ways. For example, young women may run away from home to escape childhood abuse and, as a result, stop attending school. Resultant low levels of education reduce employment prospects, increasing the chances of economic marginalisation and, in turn, offending. Domestic violence in teen relationships may have similar educational, and thus economic impacts. Additionally, the trauma of victimisation can spearhead mental health problems, associated substance abuse (as a form of self-medication), and offending (Daly 1994; Jeffries and Chuenurah 2018, 2019; Jeffries et al. 2019a, 2019b; Owen et al. 2017).

In addition, gendered norms result in a greater emphasis on social bonding and relationship building for women. Thus, attachments to family and intimate partners are more likely related to women’s offending/criminalisation than men. These bonds are exacerbated in societies with matrifocal kinship systems like Thailand. Here, cultural expectations are placed on women to meet the needs of both immediate and extended family. To uphold familial obligations, matrifocality in Thailand requires women to undertake daughter duty. Dutiful daughters take care of parents and other family members (e.g., siblings, grandparents, extended kin), including the provision of financial support (Angeles and Sunanta 2009, p. 554). Imprisoned women are generally undereducated, which results in poor employment prospects, increasing the chances of economic marginalisation. Poverty plays a key role in many women’s pathways into crime, intersects with familial economic provisioning, and is exacerbated in cultural contexts where women’s financial familial responsibilities expand beyond the nuclear family (Cherukuri et al. 2009; Jeffries and Chuenurah 2019; Jeffries et al. 2019b; Khalid and Khan 2013; Shen 2015).

The particularities of women’s requisites and background not only set them on a pathway to prison, but also determine imprisonment experiences. Women’s incarceration experiences are, in many ways, different from those of men. Most prisons and prison regimes have been established for the male majority, making women’s gender-specific needs peripheral. Subsequently, imprisonment can be an especially castigatory experience for women, further compounding the trauma and marginalisation that led them into prison in the first place. It is important that rehabilitative efforts in prison pay attention to the pathways that women have travelled (Brown and Bloom 2009, p. 314).

Re-entry, like pathways to, and experiences of imprisonment, is a gendered phenomenon because women’s lives post-release are distinct from men’s (Brown and Bloom 2009, p. 315; Cobbina 2010, p. 211). Gender differences in pathways to prison are inherent in re-entry. Formally incarcerated women have multifaceted and intersectional needs distinct from those of men, stemming largely from victimisation, trauma, substance abuse, mental illness, economic marginality, and their need to reconnect with families (Cobbina 2010). More explicitly, the research literature on re-integration highlights the following as foremost to women: (1) obtaining stable and secure housing, (2) maintaining healthy relational connections, (3) establishing financial security, (4) healing from trauma, mental health problems and substance abuse, (5) normative community acceptance, (6) provision of through care support/continuity of care, (7) supportive prison environments and re-entry planning, (8) having spirituality and faith, and (9) possessing emotional strength and motivation to change. Each are discussed in detail below.

For many formally incarcerated women, the ability to acquire housing is ‘out of reach’ due to poverty, individual level disadvantages (e.g., mental illness and substance abuse), stigma, and gender discrimination in the housing market (Baldry et al. 2006; Heidemann et al. 2016). Research shows that post-release, women have greater problems securing housing than their male counterparts (Baldry et al. 2006). Yet having a place to call home is imperative for successful re-entry, as it enables women to regain independence, privacy, and to exert autonomy (O’Brien 2001; Opsal 2015; Heidemann et al. 2016; Tarpey and Friend 2016).

In contrast, there is a strong correlation between poor accommodation and negative outcomes (O’Brien and Leem 2007; Severance 2004; Tarpey and Friend 2016). Research by Baldry et al. (2006), for example, found that women who have unstable or unsuitable accommodation are more likely to return to prison. For those re-entering the community, homelessness creates an environment conducive to substance misuse and other criminality (Carter 2019, p. 4). Women who cannot secure stable housing may also be forced to return to unhealthy and unsafe housing environments because there are no alternatives (Van Olphen et al. 2009, p. 4).

Research consistently shows that connections to family and friends strongly predict re-entry success (O’Brien 2001; Bui and Morash 2010). Arditti and Few (2006, p. 103) conclude that, “those [women] who maintain family ties and re-enter family life successfully after incarceration are less likely to be re-arrested.” Relationships with romantic partners, family, and friends provide formally incarcerated women with crucial sources of support via practical assistance (e.g., money, housing childcare and employment opportunities), and/or emotional provisioning, while also tendering a sense of belonging (Leverentz 2006; Arditti and Few 2008; Cobbina 2010; Leverentz 2011; Opsal 2015). Furthermore, and compared to men, positive interpersonal relationships are more significant to women’s positive transformation post-incarceration (Herrschaft et al. 2009). However, it is important to recognise that interpersonal relationships might also impede women’s re-entry. Intimate partners, friends, and family members may be deviant/criminal themselves. These associations can lead women back down a pathway to substance abuse and offending (Bui and Morash 2010; Few-Demo and Arditti 2014).

Women’s victimisation and associated trauma via intimate relationships contribute to their pathways into prison. Thus, abusive and criminal intimate partners can cause difficulties during re-entry. They can, for example, make home an unsafe place to live. As a coping mechanism, women may start/return to drugs and/or alcohol misuse. Furthermore, abusive and criminal romantic partners may use, coerce, or manipulate women into further offending (Bui and Morash 2010; Cobbina 2010). Even if boyfriends/husbands are not overtly abusive, intimate relationships with dysfunctional men can be a source of much apprehension (Cobbina 2010; Kellett and Willging 2011). Women may find themselves embroiled in their intimate partners’ deviant/criminal activities. Disconnecting from this could mean separating the family. Women may not be economically and/or personally prepared to do this. Thus, to maintain intimate relationships and economic survival, women may participate in their intimate partners’ deviant/criminal enterprises (Few-Demo and Arditti 2014, p. 1301).

Studies of women’s re-entry show that children can be an important catalyst for change, with motherhood providing the impetus to desist from crime and substance misuse (Cobbina 2010; VanDeMark 2007). Women will often be anxious to re-unite with their children after release. While motherhood can act as a motivator for women’s re-entry success, it nevertheless poses challenges that may result in strain, maternal distress, and as a result, may lead women back down a pathway to crime and/or substance misuse (Arditti and Few 2008; Brown and Bloom 2009; Harm and Phillips 2001). Circumstances that set women on a pathway to prison to begin with frequently remain unchanged or are made worse post-incarceration. This means that post-release, women attempting to re-unite and parent their children must still grapple with issues such as poverty, domestic violence victimisation, and addiction (Arditti and Few 2008; Brown and Bloom 2009). For example, Harm and Phillips’ (2001) study of re-entry showed that while some women were positive about re-uniting and parenting their children, others were concerned about their ability to provide financially and emotionally. Women expressed angst about drug use and/or the desire to use drugs as a result of dealing with their children. Like other relationships, motherhood can have positive or negative impacts upon women’s re-entry success.

As noted previously, poverty which is frequently linked to under-education, often underpins women’s pathways into prison. Women’s economic marginality is usually exacerbated by serving time. Women regularly leave prison with no savings and few job prospects (Severance 2004, p. 76). Furthermore, post-release studies show that men have “better opportunities for securing a sufficient income-producing and legal job by virtue of their gender alone” (O’Brien 2001, p. 2). Formally incarcerated women are “ineligible for some jobs and turned down for others” and the ex-inmate stigma weighs particularly hard on them (Dodge and Pogrebin 2001; Blitz 2006; Severance 2004, p. 77). Thus, to support women’s re-entry, it is important that women are provided with education, training, and work opportunities during incarceration in order to enhance their prospects of procuring meaningful, and adequately paying, employment post-release.

Dodge and Pogrebin’s (2001) research illustrate the difficulties of securing employment post-release. Here, most women reported experiencing negative reactions from potential employers because of their criminal histories. This resulted in women taking meaningless, low paid ‘dead-end’ jobs, with no chance of advancement. Securing stable employment and earning enough money to support themselves and their families is crucial to women’s re-integration (Blitz 2006; O’Brien 2001; O’Brien and Leem 2007; Pogrebin et al. 2014; Severance 2004; Van Olphen et al. 2009; Valera et al. 2017). O’Brien and Leem (2007) found that the crucial needs reported by women in their study included job placement, job training, and education. The inability to secure adequately paying employment may force women to return to unsafe or unhealthy living situations (e.g., return to abusive families or spouses for support), and/or pressure them to earn a living illegally (e.g., by selling drugs, sex work or property offending) (Van Olphen et al. 2009, p. 10).

Women in prison often have co-occurring needs related to experiences of victimisation, trauma, substance abuse, mental and physical ill health (Binswanger et al. 2011b, 2011a; Colbert et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2015; Lewis and Hayes 1997; Salem et al. 2013). Prison environments can both ameliorate, by forcing sobriety, physically removing women from ‘outside hardships’ such as abusive intimate partners and exacerbate these problems. In terms of the latter, studies show that the prison experience can be especially traumatic for women (Carlton and Segrave 2011). Thus, in their research on women’s re-entry, Carlton and Segrave (2011, p. 558) found that, “the experience of imprisonment can emulate and magnify pre-existing traumas, placing women at risk upon release.”

Being released from prison can intensify women’s suffering. Studies show that re-entry is often traumatic and overwhelming. Women may feel unprepared to leave the stable and predictable structure of the prison (Kenemore et al. 2006). Going from possessing little or no agency to doing everything for themselves can be overwhelming and stress-inducing (Kellett and Willging 2011). As concluded by Carlton and Segrave (2011, p. 560), “trauma at once precedes and is often compounded by imprisonment and the pains associated with release” (e.g., inability to find housing, employment, feelings of loneliness, despair, and strain created by moving from a very controlled to uncontrolled environment) (also see Colbert et al. 2013).

Given the relationship between trauma and ill health, it is unsurprising that women’s post-release mental and physical well-being is typically poorer than for women in the general community, and they are significantly more likely to die of unnatural causes (Carlton and Segrave 2014, p. 271; Lewis and Hayes 1997). Predictably, re-entering society with histories of trauma, mental and/or physical health problems poses challenges. For example, Mallik-Kane and Visher’s (2008) study on health and women’s re-entry showed that reintegration experiences varied by health status. Women with physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions followed distinct trajectories, reporting significantly more negative experiences in terms of obtaining housing, securing employment, gleaning familial support, and maintaining abstinence. In particular, and compared to their counterparts, women leaving prison with pre-existing substance abuse problems engaged in more post-release substance use, criminal behaviour, and were more likely to be re-incarcerated within one year of release (also see Severance 2004; Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008; Visher and Bakken 2014).

Believing that you will be accepted back into normative society is an important factor in re-entry success, yet formally incarcerated women often experience on-going stigmatisation. Through women’s social interactions they become acutely aware that they are viewed as perpetually untrustworthy, deviant, and criminal. This stigma is perpetuated by normative constructions of ex-inmates as having an essential and, therefore, inescapable, non-normative immorality. The label ‘ex-prisoner’ is typically viewed by normative community members as not only a reflection of a woman’s past misdeed, but as a prediction of her future behaviour. The potency of this narrative means that women labelled criminal by the state via incarceration may struggle to escape the label (Opsal 2011, p. 139).

Women re-entering society are intensely aware of their criminal label. Furthermore, the ex-inmate stigma is more acutely damaging for women because they are perceived as doubly deviant; having violated normative cultural expectations pertaining to appropriate feminine behaviour in addition to criminal law (Dodge and Pogrebin 2001; Moran 2012; Opsal 2011). The impact of the ex-inmate stigma on women re-entering the community manifests in several ways. First, compared to those without a criminal record, employers are significantly less likely to hire ex-inmates. Second, securing housing is difficult for those with a history of imprisonment. Third, as women become aware of their outsider status, they may isolate themselves, experience psychological stress, and other health problems (Opsal 2011).

Reconnecting to normative society can be difficult for formally incarcerated women due to a myriad of factors (e.g., stigma, mental health problems, substance abuse histories, trauma). The pains of re-entry can be soothed by connecting women on the outside with health care, social support services, and programming that is relevant to their needs (Carter 2019; Valera et al. 2017). However, studies show that pre-release planning is rarely done in prison, and as a result, formally incarcerated women find it difficult to access much needed community support services. This is concerning because “institutional and community anchors” (e.g., non-profit service organisations and health care services) provide considerable support and create “positive pathways” for formerly incarcerated women (Valera et al. 2017, pp. 8–10). Therefore, it is crucial that through-care support/continuity of care is provided, because when women’s needs are negated, they are at greater risk of failure (Arditti and Few 2006; Morozova et al. 2013; Baldwin 2009; Cobbina 2010; Valera et al. 2017; Schram et al. 2006).

In many correctional systems, women may be released on parole. The parole system, at least in theory, delivers a readymade avenue for service provision and through-care support. Originally, the aims of parole were to assist the criminal justice system in achieving the ambitions of rehabilitation and re-integration. However, more recently, a shift has occurred in many western nations (e.g., the United Kingdom and United States), and systems of parole are now framed around surveillance and risk management (Opsal 2009, pp. 311–12).

Given what is known about women’s pathways into prison, re-entry planning prior to release is imperative to address women’s individual needs, and to allow for through-care support/continuity of care. However, and as noted above, re-entry plans are frequently negated (Valera et al. 2017, pp. 8–10). Prison authorities should be planning for re-entry from the beginning of a woman’s sentence. In prison, women should be supported to heal from trauma, remain connected with families, address problems of substance misuse and mental ill, and be extended training and educational opportunities that increase their chances of securing meaningful, adequately paying employment post-release (Dodge and Pogrebin 2001).

Unfortunately, women’s incarceration experiences rarely prepare them for life outside prison walls. For instance, Huebner et al. (2010) study of recidivism amongst formally incarcerated women showed no correlation between participation in prison-based programmes and recidivism because of the inability of such programmes to address women’s needs. Baldwin’s (2009) study revealed that women’s pre-incarceration experiences (e.g., abuse and trauma) followed them from the community into prison. Women in this research reported being re-victimised by prison staff and were not offered programmes explicit to their requirements; namely, education, employment, help for physical, mental and sexual abuse, re-entry programming/planning, and connection to post-release support services. Teh’s (2006) study of women’s re-integration requirements resulted in recommendations for the introduction of substance abuse programmes in women’s prisons, alongside programmes/services to address mental health needs and victimisation histories.

Finally, religion has long played a significant role in prison programmes and treatment. Religious practices can provide comfort and guidance to some women in prison and as such, may continue to do so post-release. Severance (2004) explored how female inmates prepare themselves for re-entry. Faith and prayer were highlighted as strategies many women viewed as essential to re-entry success. Similarly, Parsons and Warner-Robbins (2002, p. 11) found that a belief in god is important to some formally incarcerated women. In this study, faith provided women with “a source of strength and peace in their lives.” Nevertheless, acceptance into religious communities outside prison walls is not always guaranteed. The stigma of the ex-inmate label may result in rejection by religious communities (Dodge and Pogrebin 2001).

3. Research Methods

Utilising the voices of criminalised women and those who support them during imprisonment (i.e., prison personnel), this study identifies the expectations and experiences (including needs, challenges, and successes) of imprisoned/formally imprisoned women re-entering the community in Thailand. Most women returning to Thai society will have been incarcerated for a drug offence. This study subsequently focused on drug offending/criminalised women. Pathways to prison and experiences of imprisonment are inherent in re-entry expectations and experiences. Thus, trajectories into and through prison are explored alongside re-entry expectations and experiences.

Thailand places a high priority on the gender-specific contexts out of which offending arises, and the different needs of women in prison. This is manifested in the work undertaken to guide the development of the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules), which were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010 (United Nations General Assembly 2010). In practice, several women’s prisons in Thailand are now considered Bangkok Rules-compliant. Further, in 2019, one model prison was piloting an intensive re-entry programme denoting it as a Model Prison Plus.

To adequately reflect variation in experiences by prison type, research participants were drawn from a mainstream women’s prison, Bangkok Rules Model Prison, and the Model Prison Plus. To protect the anonymity of participants, the names and locations of these correctional facilities are not provided. Further, research participants were allocated pseudonyms, and results are presented thematically.

In Thailand, close to 50% of women imprisoned for drug offending are sentenced to terms of between two and five years (personal communication, Thailand Department of Corrections). Thus, we attempted to recruit women serving sentences within this radius. To capture differences between first time and repeat offenders’ re-entry expectations, and gain insight into the latter’s prior re-integration experiences, we sought participation from equal numbers of women who had served prior imprisonment terms and were incarcerated for the first time. We also conducted interviews with women who had recently returned to prison because re-entry experiences were foremost in their minds, and we followed a small group of women out of prison.

Prisoners who met the study’s inclusion criterion were first invited to participate by prison staff, and those who volunteered, were introduced to the researchers. From here, the researchers provided further, more detailed information about the study to potential participants (i.e., study aims, voluntary nature of participation, ethnical issues including risks, confidentiality and anonymity). Those who agreed to participant were then provided with a written information sheet about the study, and they provided signed/written consent to participate.

In total, n = 75 interviews were undertaken with imprisoned women, and an additional n = 5 interviews were completed with women post-release. Interview topics consisted of women’s responses to broad discussion topics as follows:

- Pathways into prison

- Childhood experiences

- Adulthood experiences

- Education, employment and economic circumstances

- Health and substance abuse histories

- Circumstances surrounding their offending/criminalisation

- Prior arrests and terms of imprisonment

- Lives in prison

- Experiences of imprisonment

- Needs addressed/not addressed in prison

- Pre-release planning

- Expectations/experiences of re-entry

- Definitions of success and how these might/were/are being achieved

- Challenges that might be/were/are being faced

- Needs and how these might/were/are being addressed

Three focus groups with n = 16 correctional staff in each correctional facility were also conducted to gauge perceptions of women’s: (1) pathways into prison, (2) needs and experiences in prison, (3) re-entry expectations/experiences, needs, challenges and successes. All staff were informed about the research by prison administration, and volunteers were called for. Written consent to participate was obtained from all focus group participants. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained by not naming or identifying prison staff.

The interviews and focus groups lasted from between one and two hours and were audio recorded. Some interviews were conducted in English and simultaneously translated into Thai. Other interviews, and the focus groups, were conducted in Thai. All interviews and focus groups were transcribed into English, collated and analysed thematically to identify common topics, ideas and patterns of meaning. Results are presented sequentially below. We begin with a descriptive overview of the research participants. This is then followed by our thematic findings of women’s pathways into prison, lives in prison, re-entry expectations and experiences, including needs, challenges, and successes.1

4. Descriptive Overview of Research Participants

The average age of the women interviewed was 36.5 years. Most women identified as Buddhist (80%), and some reported being Muslim (15%) or Christian (5%). Educational levels were generally low. Only 20% had completed upper secondary school, and over 40% had never attended/or only ever completed primary school. Most women reported drug selling as their primary means of income prior to imprisonment (45%). The remaining women were predominately employed as shop assistant/salesperson (15%), factory workers/general labourers2 (11%), were supported by family members (9%), worked in the sex industry (9%), or in hotels/bars/restaurants (5%). Women were convicted and sentenced to prison for being either in possession of illicit drugs for use (24%), for distribution/selling (39%), or the actual distribution/selling of drugs (36%). One woman was incarcerated for driving under the influence of narcotics. Nearly every woman (97%) was imprisoned for a drug offence involving Yabba tablets (a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine) and/or Ice (crystal methamphetamine). Around 65% of interviewees were sentenced to imprisonment from between two and five years. The recently re-incarcerated women had only been imprisoned from between two and five months. Most of the remaining women (65%) were due for release within four months. Just over half the women (53%) had served prior terms of imprisonment.

Focus group participant details are provided in Table 1 (below). As can be seen, the prison staff undertook a variety of roles and had extensive experience.

Table 1.

Focus group participant characteristics.

5. Women’s Pathways into Prison

The first step toward understanding and constructively responding to women’s reintegration, is knowledge of how they came to be imprisoned in the first place. The characteristics of women’s life histories set them on a pathway to prison, impact their incarceration and post-release experiences. The following themes were identified: (1) victimisation, (2) other adverse life experiences, (3) economic marginalisation and familial caretaking responsibilities, (4) deviant friendships and childhood deviant behaviour, (5) emotional distress, substance misuse and help seeking. Each are explored in detail below.

5.1. Victimisation

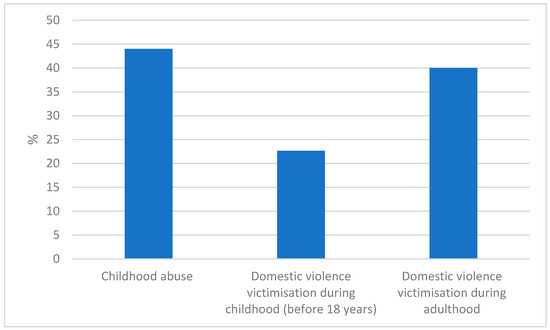

Victimisation (including physical and emotional abuse) in childhood was a common theme in the women’s stories, as was being the victim of domestic violence over the life course (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Women’s victimisation experiences.

As children, 44% of the women recounted growing up in homes marred by violence either perpetrated directly against them by caregivers, and/or their mothers, by male family members. For example, Boonsri experienced physical violence ‘at the hands’ of both her father and stepmother, and later witnessed her mother being violently assaulted by her stepfather. When she was a toddler, her father “threw [her] to the wall because [she] was too attached to [her] mother and [she] cried all the time.” Boonsri’s parents eventually separated, and she was left in her father’s and stepmother’s care. Both were abusive. Eventually, the violence Boonsri endured at home led her to drop out of school and run away from home. She said, “I chose to call off my education [in grade 8] even though I had never missed school. I was very miserable and desperate. I ran away and hid out in an overgrown forest under motorway bridge so my father wouldn’t find me. I took a bus [to find my mother].” However, there was no respite from violence at Boonsri’s mother’s house. She continued, “after living with her for a while, I had to move out again. My mother had a new husband. One day, they were drunk and fighting and he was going to use a knife with my mother.”

Abuse experienced in the family home frequently caused young women to “run away,” become “attached” to deviant friendship groups, and use and/or sell drugs. Childhood abuse, therefore, played a fundamental role in women’s offending pathways. In the following quote, the link between child abuse and subsequent deviant/criminal behaviour is described:

“My foster father drank quite a lot. When he was drunk, he was always yelling. I was beaten by him every time he was drunk which was almost every day. My memory of him was always him beating me. I felt really scared of him at the time so that’s part of the reason why I decided to use drugs. [The abuse] made me feel like I didn’t want to stay home. So that’s part of the reason I decided I didn’t want to go to school. So, I spent time with my friends and started doing drugs. It was around the fifth grade when I started using drugs [Yabba], it helped me forget about what was going on at home. [I was using Yabba] Every day. I moved in with my friends and never went back to school. I started selling drugs [to support myself].”

Like child abuse, the trauma of intimate partner abuse can also lead to substance misuse as a coping mechanism. For example, when Ploy was 13 years old, she was raped by her boyfriend. They were subsequently married because he “took responsibility” for having ‘sex’ with (i.e., raping) her. After they “moved in” together, Ploy’s boyfriend “kicked, punched and [did] all kinds of things that a man can do to hurt people every day.” Ploy fell pregnant when she was 15 years old, but her boyfriend “hit me until I lost my unborn child.” Ploy explained how she started to “sniff glue” and later Yabba because she “didn’t know what to turn to.”

Drug offending also provided women with a way to physically extradite themselves from abuse. Hom decided to sell drugs so she could save money to escape her domestically violent intimate partner. She explained:

“I had already got one child. He used drugs and sometimes, under the drug influence he couldn’t control himself, he hit me, hurt me. He also had affairs with other women and didn’t come back home. I was just housewife. I couldn’t go to work. I had to wait for him at home. He took drugs, not only Yabba, he took heroin. I couldn’t leave. The reason why [I started selling drugs] is because at that time I had two babies and I wanted to have my own house outside of this family. So, I needed to earn some money to provide for myself with my children. I wanted to have somewhere we could stay outside [away from my husband].”

Abusive intimates can further use women’s addictions to control, entrap, and punish them. Sroy explained how her imprisonment was the direct result of her domestically violent boyfriend. She said, “he made me feel like I’m a really bad person because I’m a drug addict, but he was the one who gave me the drugs. He’s addicted to drugs. He was really controlling and wanted me to stay in the house. I could use drugs in the house, but I couldn’t go out and use it with my friends.” Sroy eventually left her abuser. However, as is often the case with domestically violent men who lose control over their victims, Sroy’s now ex-boyfriend punished her for leaving the relationship, and his actions resulted in her imprisonment. She explains, “we got into a fight and separated so we lived separately. He got really upset with me [and] that’s why he called the police to my house to arrest me.”

5.2. Other Adverse Life Experiences

Other adverse life experiences are stressful or traumatic events that include, but are not limited to, victimisation (discussed above). In childhood, these may incorporate community and household dysfunction, like growing up with substance-abusing family members, parent-child separation, poverty, and leaving home to take on adult responsibilities, such as parenting, employment, and/or getting married. During adulthood, adversity can be embedded in dysfunctional intimate relationships, families, and communities. Like victimisation, other adversity across the life course is associated with both substance abuse and offending/criminalisation.

During childhood, many of the women described living in disordered communities characterised by drug use and dealing, households marred by severance of the parent-child relationship, familial substance abuse and/or other deviant/criminal behaviour, poverty, associated low levels of education, and child labour. Teen pregnancy and motherhood were also common alongside marrying young, and/or being in intimate relationships with partners who were unfaithful, and/or drug offended.

Close to three-quarters of women were estranged from their parents as children. Parents either died, were incarcerated, went away to work, and/or separated from each other, fracturing the parent–child relationship. Prison personnel expressed the centrality of parent-child detachment to women’s offending. They said, “mostly we find that their parents got divorced and they grow up with one parent or some of them grow up by themselves. Family issues, they think that doing drugs can help.”

Some of the women (21%) reported witnessing drug offending in their childhood neighbourhoods. Phonphan said, “I grew up in a slum where there are plentiful of drugs. You just open your door and you can see drug trafficking and dealing everywhere.” Prison personnel noted that one of the reasons women committed drug offences was because “they live in drug communities, in the red zones.” Red zones are districts denoted by law enforcement as locales with an over-preponderance of drug dealers, and isochronal congregation of drug users including “slum like neighbourhoods” (Hayashi et al. 2013, p. 4).

Further to residing in neighbourhoods saturated by drug use and offending, 52% of the women narrated living with familial substance abuse and/or other deviant/criminal behaviour as children. This included fathers, mothers, older siblings and stepsiblings, cousins, uncles, aunts, and grandparents who resided with the women during childhood (or close by, usually in the family compound). The women described these family members as one or more of the following: alcoholics, gambling addicts, drug users, drug sellers, drug addicts. Exposure to these types of familial behaviours during childhood was linked to offending by both prison staff and women.

Prison personnel observed, “[The] majority of the [women] prisoners, either [have a] father or mother [who] is an alcoholic. So, the child would not want to be at home. It is [a pathway to prison] because that father and mother drink, siblings, aunts also drink and do gambling, so they think this is not wrong to drink or gamble and this also leads to smoke cigarettes and other issues.” Tansanee explained how seeing her cousin use drugs in her early teen years led her to try Yabba. She said, “because I saw the relative [older cousin] with drugs and I wanted to know, I wanted to try.” Rotsukhon’s mother “sold drugs since the beginning.” She said, “I’ve never been involved with it. but after I moved in with her [during early adolescence], I had no choice [but to help her sell drugs]. I knew all the things she was doing.” Prija similarly started to use and sell drugs during her early adolescence after witnessing her parents operate a drug business throughout her childhood. She narrated, “For me, I didn’t see any good thing in my life. I wanted to try [drugs, using a selling] because my parents sold drugs. My life was supposed to be better than that. And I didn’t understand why my family had to be like that. Why me?”

Some women (37%) lived with childhood poverty, reporting that their caregivers struggled to meet daily household expenses. Poverty is stress inducing, and invariably resulted in the women exiting education at a young age (thus reducing future employment prospects) and taking on adult work/employment tasks to help support their families. Arich explained how she left school in grade six and collected wood with her siblings, “we have six kids in the family and our financial situation is not good. We were poor. I had to earn some money by going to collect some wood from the factory. My parents could not afford education. I did not want to trouble them. They had to work hard for all of us, so I just quit [school in grade 6].”

Adolescent pregnancy, motherhood, and marriage (including unofficial coupling) were commonplace (47%). This also caused women to leave school early, with collateral flow on effects to employability. Often, these teenage intimate relationships were formed with significantly older men, and in some cases, pregnancies and marriages emerged against the backdrop of sexual assault. Kaali was only 12 years old when she met her 20-year-old boyfriend. She stayed “with [her] boyfriend at his place and I didn’t go to school.” Yungying “got pregnant” to a man “20 years older” and as a result, “didn’t pursue studies.” When Adranuch was 14 years old, she “got married” to a man who had “raped” her because “he took responsibilities.” She would later endure ongoing domestic violence at her husband’s hands.

Several women (33%) narrated stressful/dysfunctional intimate adolescent relationships marred by infidelity, spousal drug use, and/or other deviant/criminal behaviours. During adulthood, dysfunctional intimate relationships continued to be commonplace. Most frequently, the women reported being romantically involved with men who either used and/or sold drugs (67%). Women’s pathways to prison are often directly connected with boyfriends, husbands, and/or other men in their lives. The connection between intimate relationships with men and women’s offending/criminalisation was highlighted by prison personnel during the focus groups:

“One of the reasons [why women are in prison] is because of the boyfriend. The big drug dealers are men. The women are the victims of the men. They have been forced to deliver, sell drugs. They become the victim. Sometimes their boyfriend did it, and since they kind of stick with their boyfriend so they go to do it together. Or some of them just did not stop their boyfriend from doing so. Just like Thai proverb, ‘you are who you associate with’, yes sometimes their boyfriends influenced them to involve with drugs. If they have the boyfriend who is a [drug] seller, she will become seller. Boyfriends do sell [drugs], the girlfriends do not know, but must also come in jail. For female drug offenders, they are not the lead offenders, mostly the boyfriends … they live with. So, when the police go to the house, she must also come to jail.”

Other focus group participants explained that women often intentionally ‘took the fall’ for drug-offending boyfriends/husbands. This occurred for two reasons. First, ‘doing time’ in a woman’s prison was perceived as being easier than in a male facility. This resulted in women taking the blame for their romantic partners to spare them the grief of incarceration. Second, gender norms that tie women to unpaid domestic labour within the home while ensuring male earning capacity meant that incarcerating women, rather than the men, was deemed as being in the best interests of familial economic survival:

“There is also a belief that if imprisoned it will not be as difficult [prison life] for the female as it is for the male. As in if the female accepts the charge for the male, there is a belief that it will not be as difficult for her [to serve time] as the male. People view female prison as better. They believe that the female prison is not as bad as the male, so this means more females are imprisoned. Normally it is a woman’s mentality that will accept the charge for men, it is because of love. They accept being imprisoned for the man and hope the man [will] stay outside the prison to take care of the children. In case the man is imprisoned instead, the woman must be the one who works and take care of the children which would be more difficult.”

Similarly, for the women interviewed, intimate relationships with drug offending men often represented a decisive life moment propelling them toward imprisonment. Women were either introduced to drug use and selling by their intimate partners, and/or their drug offending accelerated in partnership with their boyfriends/husbands. Women also expressed ‘taking the fall’ for their intimate partners’ drug crimes.

Pensri told us, “My boyfriend was using drugs. At first, I didn’t use it, but then my boyfriend said, ‘Would you like to experiment? You can try it. If you don’t like it, you don’t have to.’ I tried and got addicted. I wanted my boyfriend to be happy. He told me to use it, so I did.” Khajee had already tried Ice with her friends before she met her boyfriend, who both sold and used Yabba. Within this relationship, Khajee’s drug use changed from Ice to Yabba, and she soon developed an addiction to the latter. She explains how this unfolded:

“[Eventually] I sort of knew that he had the style of a drug dealer. He gave me some Ice. He had asked me if I did Ice and I said yes. So, he gave me some, but when I used drugs with him it was different from when I used it with my friend. When I was with the friend, it was like she was hogging the stuff for herself. I didn’t know at the time that sometimes she would syringe an empty bottle for me. But when I was with him, he would syringe the drugs directly for me and it felt like we went all-out. It felt fulfilling. When I was doing it with the friend it always seemed like she was hesitating for me to use, but when I was with him it seemed like he was willing to give me all I wanted. So, from that time I became addicted.”

In the examples above, drug use began, or was extenuated via intimate relationships, but women also described how they started to sell/deal drugs as a result of their romantic entanglements. Phueng explained how she started to sell drugs in partnership with her boyfriend:

“Even after I knew that he was using drugs, I decided to stay with him. After I realised that he is addicted to it, he asked me to help him in selling it because we could earn some money. That’s when I started selling drugs. He would deal with the clients and they will come pick it up from me, pay the money to me. Because he was selling drugs, I start selling drugs. I was the one who volunteered to help. I just wanted to help him earn some money.”

Separation from drug using/dealing intimate partners presented as another pivotal juncture in the women’s life histories. Sari, for example, started selling drugs after her husband went to prison. She said, “[I was not involved with drugs] until I met my husband. [This was the critical moment in my life] because he was addicted to drugs. My husband got arrested [went to prison], so I had to send him money. I started to sell on his behalf when he was gone.”

Some women reported being imprisoned as a result of guilt by association. Narissara, for example, had tried Yabba “a couple of times” with her boyfriend, but had not been directly involved in his drug-selling business. Despite this, she is now in prison for drug distribution. She explained, “I found out that he [boyfriend] deals with drugs. I lived with him and I started using drugs. So, on the day that police arrested us, the police wanted to arrest that guy [boyfriend]. But then when the police came to the house, he ran away and then I was the owner of the house. So, I was there and got arrested.” Rutna ‘took the fall’ for her boyfriend’s drug offending out of love. She explained:

“There was a friend who had a boyfriend who just got out from prison. And we constantly bought drugs from this friend. But then the last time we went to buy drugs from this friend the police were there. And then both I and my boyfriend got arrested. I told the police that it is all on me. So, I came in here alone and my boyfriend did not. I once promised my boyfriend that if this kind of thing happened, I would take the responsibility. My boyfriend had already gone to prison once and if he had to go again, it would last more than two years. So, I decided to come in here for him. I love him very much.”

Drug addiction will often result in problematic dynamics in romantic relationships and emotional distress. Thus, it was not uncommon for the women to recount broader intimate relationship dysfunction (51%), and the fracturing of romantic bonds. In most cases, intimate partner infidelity was relayed. This contributed to drug use and offending. For example, Tola’s husband and father of her children “brought a woman home. I was hurt by the husband.” She left him and started selling Yabba to support her children because her husband did not financially provide for them. Beam and the father of her children “broke up when [their] youngest child was just over one year old”. She explained, “my boyfriend had affairs. I couldn’t take it.” Beam “started to use more drugs after we broke up [because] at that time it hurt when I found out that my boyfriend went out with other girls.”

5.3. Economic Marginalisation and Familial Caretaking Responsibilities

Nearly all the women in this study were mothers (83%), and/or had other family members (most frequently parents and grandparents) who were economically reliant on them (36%). Thus, drug selling often occurred within the milieu familial economic provisioning and daughter duty. Dara had to take care of her children and other family members. She explained, “I was the main source of income to provide for my father, my mother, and my baby.” Toey “was the only one who was responsible for taking care financially of the children and grandchildren.” Nadir expounded, “I just wanted to earn money and send some money to my mum.” Pundit stated, “the money wasn’t enough. I wanted to earn money for my mother, not for myself,” and Karawek said, “if I hadn’t dealt drugs, we wouldn’t have had enough to live. I have the grandchildren who need milk, need food.”

Other women reported using Yabba because it “gave them energy,” enabling them to work longer hours. Waan “only used drugs to keep [herself] working,” and Pen Chan “started using drugs because [she] had to stay alert at work for long periods of time.” Women who “worked at night” in bars, clubs, and/or the sex industry also used Yabba to keep them awake and alert, enhancing their ability to drink alcohol with clients, lose weight, and protect themselves. Waan explained, “[I had to work] pretty late. That’s how I found out all my co-workers were on drugs. They recommended me to take drug and claimed that I won’t get sleepy and that it helps me remain skinny. [Yabba] helped me stay awake. I also got skinny because I didn’t feel hungry after I took it.”

The association between drug use, ‘working at night,’ and sex work was also underscored during focus group discussions. In the following dialogue, prison staff deliberate how labouring in these industries can lead to drug use, addiction, and eventually imprisonment.

“Some need to work at night so drugs help them. Yes, many are night-workers, bar workers, sometimes they use drugs with the customers. Many women need to sleep with the customers, so they need to take drugs. When working at night they must stay awake. Then they must sleep with the customers. The customers will bring drugs for them to take for sex. They must follow the customer’s instruction and just get [the sex] over with. When this happens more often, they become addicted to drugs.”

Prison personnel’s comments regarding addiction were supported by the women interviewed. Invariably, using drugs within the context of employment can lead women down a pathway to addiction. Lawan who “worked at night, used almost every day.” Similarly, Phloi explained, “[I started to use Yabba] because I had to work the night shift, some of my colleagues recommended I take it so that I won’t feel sleepy. So, I took it. And the more I used, the more addicted I have become.”

While most of the women who sold drugs for economic reasons were motivated by survival, for some material consumption, “partying” with friends, and the “night life” was the galvanising factor. Honey said, “so all the money I earned from selling [drugs] during those times, I just spent it all on going out at night.” Likewise, prison personnel commented that while “poverty” and “the family’s financial situation” was central to offending, some women came from wealthy families and “only used drugs just for fun, for friends, for partying.”

5.4. Deviant Friendships and Childhood Deviant Behaviour

Over half the women (53%) reported deviant peer group associations during childhood, and 63% had engaged in deviant/criminal behaviour themselves including: drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, skipping school, partying, and using and selling drugs. By adulthood, every woman had drug offending associates.

Childhood friendships presented as central to women’s initiation into drug offending. One prisoner officer noted, “also it [imprisonment pathway] is because of their friends and neighbours that they spend most of their time with.” Another stated, “teenagers are in the stage that they are curious to try, want to follow friends, which leads to usage of drugs and so on.” These sentiments were further reflected in the words of women interviewed. Amabil, for example, said, “We were so close to each other [friends growing up]. We went everywhere together. At first, I saw them use drugs, but I didn’t have any intention to try it. But later, they challenged me to use drugs, so I tried.”

For some, childhood abuse/victimisation and other significant adversity invariably propelled them into deviant friendship groups and problematic adolescent behaviour. Ngam-Chit told us, “I felt like my father didn’t love me. I quit school, I started using more drugs because I had more issues with my family. I ran away from home and moved in with my friends. I started using more drugs, every day.” Other women were pulled away from loving families during childhood into deviance/offending by anti-social peers and the excitement associated with partying, drinking alcohol, and eventually, using drugs. Prison personnel described these women as the “spoiled kids.”

Finally, like those who “worked at night,” some women were introduced to methamphetamine by female peer groups during adolescence as a panacea to weight loss. Body image often plays a crucial role in women’s self-esteem, especially during the teenage years. In Thailand, as is the case in many cultures, thinness is equated to beauty. Perceptions of attractiveness, as per the patriarchally defined societal standard, can morph into a central defining feature of an adolescent girl’s assessment of self-worth (Page and Suwanteerangkul 2007; Pisitsungkagarn et al. 2014). Mint explained, “[I started to use drugs because] I was fat, and I wanted to be in shape. My friends introduced me to drugs. I was worried my boyfriend would cheat on me. he has never told me that I’m cute. He has never given me any compliment. So, I was scared that he would cheat on me. There was someone who said that he had a fat girlfriend.” Ning stated, “at 16, I wanted so bad to get skinnier. Following my friend’s stupid advice for weight loss, I had my first contact with methamphetamine, believing that it can help my body lean and firm. I was sure that I would never become addicted to it [but] as time passed, I took it more and more and became addicted.”

5.5. Emotional Distress, Substance Misuse and Help-Seeking

Victimisation, other adversities (in childhood and/or adulthood), emotional distress, mental illness, substance abuse, and offending are often interconnected. Adverse life experiences, including victimisation, can negatively impact emotional well-being, and lead to mental health problems. Drugs and/or alcohol can be utilised as a form of self-medication to numb the emotional pain (Covington and Bloom 2007; Drapalski et al. 2009; Owen et al. 2017; Saxena et al. 2016). As noted by one prison officer, “for those who use drugs only it is probably because they are so desperate and so lonely.” As demonstrated above, adversity was a common theme in the lives of the women interviewed, and the negative life experience/substance misuse nexus was frequently narrated.

Women’s substance misuse is understood to be a defining factor in their offending/criminalisation, and women’s drug use is more closely related to their criminality than it is for men (Willis and Rushforth 2003). Thus, many of the women in this research sold drugs to support their addiction. As narrated by one group of prison personnel, “there are often two reasons behind women selling drugs. One is to have money to self-support and the other reason is to have drugs to use. When the drugs are out, they will need to have money to buy more, so they might have to sell. The profit received from selling goes to buying more drugs. One day they only use one to two tablets but before long, it could become ten per day. When the money is not enough, they would think selling would help.” Noo similarly explained, “It was like I was selling drugs just to get money to use drugs. I went out with a drug dealer friend, stayed in the same house with them, and helped them transport drugs. I guess it was because I wanted to use drugs. I was probably already addicted by then. It was an easy way to earn money, and I always had drugs to use.” Maew said, “Both me and my husband sold drugs just so that we can get the profit, use the profit that we got by selling it to buy our own drugs to use.”

At some point in their lives, close to 85% of the women defined themselves as being “addicted,” or narrated using drugs and/or alcohol regularly i.e., “usually” or “almost” “every day.” Taay, for example, stated:

“I was addicted to drugs because I need it every day. Sometimes my body cannot take it, so I go to sleep for a long time. But when I woke and need it again, I must take it. The amount that I take, 30 to 40 [Yabba] tablets a day. At that moment, it was like no way out. I was stuck in the drugs. Some moments, I am conscious, and I think it will be nice if somebody or some organisation would help me. But there is none. If you start taking drugs, you cannot go back.”

Every woman who narrated drug dependence had used methamphetamine (Yabba and/or Ice), but some (16%) also described the problematic use of alcohol. As described by Mook, “it was around one pill [Yabba] before going to work in the morning. Another pill or two in the evening after work. I drank every day. I carried a bottle with me to work every day.” Concerningly, given the connection between addiction and criminality, and the significant number of women in this research who reported problematic substance misuse, only four of the women had sought or received help prior to imprisonment.

6. Women’s Lives in Prison

As demonstrated above, economic marginalisation, familial caretaking, victimisation, trauma, substance abuse, disordered communities, and familial, intimate, and peer group relationships presented as crucial variables in women’s prison trajectories. Thus, to aid re-entry, during incarceration, gender responsive/trauma informed care/practice and programming should be utilised to empower and support women’s healing. This ought to include the provision of a healthy, rather than harming, prison environment/experience alongside programmes and support mechanisms to improve women’s wellbeing and rehabilitation prospects (Owen et al. 2017). More specifically, the women’s life histories suggest that the provision of substance misuse treatment/programmes, and support/programmes around victimisation, mental health, and trauma recovery had salience. Additionally, due to the connection between economic marginalisation and offending, educational and vocational opportunities presented as key to supporting rehabilitation and community reintegration. Furthermore, because of the centrality of caregiving to women’s lives and re-integration, prison systems should be supporting social connectiveness. Finally, prison authorities should be planning for re-entry from the beginning of a woman’s sentence. Re-entry programming and connections to post-release support services/through-care are vital. Below, we discuss women’s experiences of imprisonment including, prison environments and overall experiences, connection and disconnection with family and other loved ones, and rehabilitative programmes and support.

6.1. Environment and Overall Experiences

Women and prison staff highlighted the ways in which the general prison environment impacted prisoners in both positive and negative ways. In terms of overall positives, narrations culminated under the following themes: (1) prison as an ameliorator, (2) prison as a medium to reprioritise relationships, (3) prison as an instrument for self-reflection and growth, (4) prison as a source of support and encouragement, and (5) prison as a supplier of learning and knowledge. Each theme demonstrated how prison environments could be healthy, rather than harming. However, prison environments could also be problematic. Negatives included issues associated with overcrowding and access to necessities, an inability to source additional provisions, and the anxiety of being separated from family and other loved ones. Each theme is discussed in detail below.

Some women described how imprisonment ameliorated their problems by forcing sobriety and removing them from the hardships they faced outside prison walls. In reference to her Yabba addiction, Piti expressed that “being in here is like [drug] rehabilitation itself.” Som’s imprisonment ameliorated her from a dysfunctional and abusive intimate relationship. She said, “I feel like being in here, it is so much better than living with my boyfriend. It felt like I was in prison when I was living with him. He was jealous, he got jealous easily, I couldn’t really go out or leave the place. I feel better living here than living with him. He got mad, he physically abused me almost every day. He was extremely violent.” For Palm, prison provided a respite from the loneliness and monotony of life on the outside. She explained, “being home is more stressful because I am alone. I had a lot more fun in prison.” Pim felt better cared for in prison expounding, “I’m still worried about my life [outside of prison]. Sometimes I didn’t have enough money to buy food. I ate one pack of instant noodles. But in here, I have three meals, I have food, shelter, I have a blanket. I even have a mosquito net. So, it is safer.”

Imprisonment also helped women reassess the value of family, leading to reprioritisation of these relationships over problematic peers and intimate partners. As explained by Arpa, “prison makes me think more. I know who really loves me. I only have my mother and this time I’m in prison, I’m in prison for my boyfriend.” Bunmi explained, “like, for me, I feel like if I was never imprisoned, I imagine that I would be even more of a mess. But it’s made me realise a lot of things. I really see who has always cared about me [family not friends].” Prison staff explained how imprisonment can “soften them [prisoners] as a person, they become gentler. They never hugged their parents, but when they are imprisoned and their parents come to visit, they are able to give them hugs.”

Women expressed that prison provided the space for self-reflection, made them feel stronger/empowered, develop patience, self-discipline and parsimoniousness. Kanda commented that “the good thing [about prison] is that I get to spend my time here pondering deeply over my life.” Punika said, “I even know myself better,” and Lawana said, “at least I could organise my thoughts and sort out my life.” Janjira aired, “prison taught me to be stronger, tougher and better.” Han stated, “I learned self-discipline,” while Buppha said, “It taught me to be more patient. In the past, I was very impatient and hot-tempered.” Mae Noi specified, “I know more about spending money wisely.”

For some women, the most positive feature of prison life was that it provided them with a source of support and encouragement. Charoenrasamee told us, “I have a lot of people to talk to [in prison] because outside I don’t have many people to talk to. In here they give [me] words of encouragement.” Encouragement emanated from positive relationships with prison staff and fellow intimates. The women recurrently narrated the constructive nature of their prison friendships. “Meeting good friends” was viewed as a positive of imprisonment because it enabled women to “openly talk,” about their “problems,” and receive “help” and “support,” particularly when they were feeling “stressed.” Additionally, women expressed that prison staff were “friendly,” “nice,” “kind,” “supportive,” easy to “talk to,” and, “helpful.” Nong Yao said, “the prisoner officers are kind. They do not see me as prisoner. They see me as a person.” Prison staff confirmed, “we try to encourage them” and “what makes us prouder is that we see them encourage their friends.” These narrations indicated a level of sensitivity by prison personnel toward women’s needs.

Finally, while prison programmes are discussed in more detail below, gaining knowledge was highlighted more generally by the women as being a positive prison experience. Yu-Phin said, “they [prisons] provide you tons of knowledge,” and Pakpao said, “they [prisons] give us knowledge that some prisoners actually use out there.”

During interviews, the most common hardship expressed by the women were problems associated with prison overcrowding. Overcrowding was “stressful”, made women feel “rushed”, “uncomfortable” and like they were constantly “competing.” In addition, yet connected to overcrowding, women expressed concerns over an inability to access necessities including water, quality food, and mattresses for sleeping. Som-O said, “it is difficult because I have never lived like this before. I have never slept like this, or showered like this, or eaten food like this.”

While access to necessity items may have been stressful and sometimes less than optimal, women never went without food, water, or bedding. Still, prison life could be markedly improved for those who engaged in formal paid work, had family able to deposit money into prison accounts and/or provide provisions. With money, prisoners could purchase additional items from the prison shop. However, the capacity to access supplementary provisions depended on several elements. First, formal work was not available to everyone. Second, familial economic hardship, frequently exacerbated by women’s incarceration because they were the main economic provider, meant families were not always able to give support. Thus, for some women, the economic marginalisation experienced outside continued inside. As noted by Chompoo, “[The hardest aspect of being in prison is] necessities, especially for those without relatives, it’s really hard to get what you need.”

For many women, separation from family was the most difficult feature of imprisonment. Sirikit said, “I cry a lot because I miss my children so much.” In addition to the emotional distress caused by estrangement, women agonised over the well-being of family members. Many women were the primary caregivers of children and dutiful daughters, so the question of how families were coping financially and with the care of children was a source of anxiety. Thurian said, “I miss my family. I am worried about how they can financially support themselves. I specifically worry about the grandchildren, whether they will have food to eat, whether they get to go to school.”

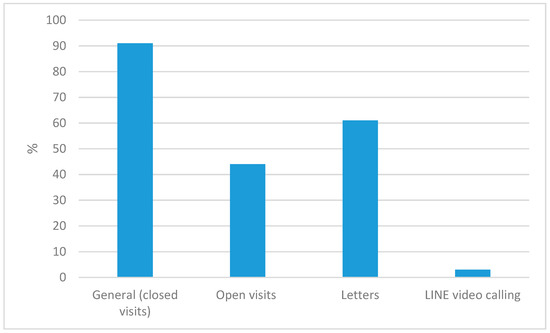

6.2. Staying Connected to Loved Ones

Separation from family through incarceration can be distressing, and connectedness to families can aid women’s re-entry success. Thus, prison systems that support the preservation of familial bonds are crucial to the well-being of women, both during, and post-incarceration. The prisons where the women were housed made every attempt, within the confines of prison overcrowding and resourcing, to support connectedness with family, friends, and intimate partners through the provision of visitation (both open and closed), letters, and3 video calling. Each are discussed in more detail below, but as demonstrated in Figure 2, most women had been in contact with the people that they cared about, at least to some degree, during their incarceration term.

Figure 2.

Women’s contact with the outside world.

Overall, women commented that staying connected to loved ones provided them with hope, happiness, and encouragement. Leila said, “I think it is happy to wait for a letter. It is a part of my encouragement,” and Nin commented, “I am very happy every time I see my family.” Duanphen stated that visitation, “encourages me a lot.”

The women explained that general or closed visitations were available at their facilities on specific days each week and tended to run from between five and 20 min. On busy days, usually weekends, women reported that visitation times were restricted due to higher visitor volume. This is likely related to coexistent prison overcrowding. Screens divided women from guests, and communication occurred through a telephone. When asked how they felt about general visitation, most women conveyed satisfaction with the environment, while some felt it was too “noisy.” Some women were satisfied with the allotted times, while others felt it was insufficient.

Open visits materialised from a couple of times per year to every few months, and tended to be longer than general visits, with women reporting session times of “twenty-five minutes” to “half a day long.” The most positive feature of open visitation was the removal of the screen, and the ability of women to physically connect with loved ones. No one objected to the environment or the designated times. However, open visitation was not accessible to everyone. Several women expounded that those classified as “lower class,” serving short terms, and/or sentenced for more than one offence, were disqualified from open visitation. Ink told us that she, “didn’t have an open visit because my class is still the bad one and because I’m here for a short period. So, my class wouldn’t be good enough for an open visit.”

Letters may also be sent and received. However, as was the case with open visitation, the ability to write letters reportedly varied according to prisoner classification. Prisana explained, “I think the system is good but here who gets to write letters depends on your class. They limit of the number of letters you can write. In like the best class the maximum that I can write is two letters a week. And then the lower class it is once a week. The third class gets twice a month.” For some, letter writing was not an option because they “cannot remember the address,” and/or their family members had literacy challenges.

LINE video calling gave women an additional way to stay connected. It was underutilised (see Figure 2, above) although it was not clear why this was the case. Prison visitation can be difficult for family and other loved ones who reside in areas located long distances from the prison. As explained by Fa Ying, “They started to use this [LINE] about one to two months ago. It is more convenient. Because our visitors don’t have to travel here to the prison, but we can see each other through the device.” Kohsoom’s mother was only able to visit her “once a year” because she lived in a province that was too “far from” the prison. Since the introduction of LINE, Kohsoom speaks to her mother on a weekly basis. She said, “It is very good. It doesn’t matter how far you are if you can see their faces. You don’t have to spend time travelling to the prison. [My mother] is far from here. It is five hours.” Once again, however, eligibility depended on prisoner classification. Dok explained, “I cannot use that because of my prisoner class that I’m in.”

6.3. Disconnection from Loved Ones

Despite provisions for visitation, letter writing and LINE video calling, at some point 67% of women recounted disconnection from loved ones. Children, parents, intimate partners, and/or other family members of central importance to the women either rarely made contact, were communicative at some point then ceased, or became completely estranged. The reasons for this varied. Some women did not tell their loved ones that they were in prison. Others explained that visitation was simply not feasible for their loved ones because of distance, and/or financial constraints, and/or age. For others, children did not visit because their caregivers, or the women themselves, did not want them to. Finally, family and/or spouses simply disappeared without explanation.

Some women explained having lost contact with family, spouses, and friends because they never told anyone about their incarceration. The reasons for this appeared threefold. First, relationships were already fractured. For example, Naowarat’s familial connections were splintered by childhood abuse, parental substance misuse, and on-going neglect. She said, “I have been alone most of my life. All my life, I’ve been mistreated a lot by my family, relatives and cousins” and “I can survive alone.” Second, women did not want to cause their families undue stress or worry. Chomesri explained, “My family doesn’t know that I’m in prison. I’ve never told them. I don’t want them to be worried or think too much about it.” Third, feelings of guilt and shame impeded women from contacting family. Chuasiri expressed, “I don’t want my children to know that their mother used drugs and is now in prison. So, I didn’t contact anyone. I have no visitor.”

Other women were housed in prisons located a long way from their families. This made visitation difficult, if not impossible. Bam’s family could only visit “around once a month” because they “live far away from this place.” Travelling long distances costs money, several women explained that their families could not afford to come and visit. Taeng expressed, “my family only visited me once. They do not have enough money and live far away. That makes me feel stressed and sometimes upset.” Once incarcerated, the care of children frequently fell to aging parents and grandparents. Travelling, especially over long distances with limited money, can be a chore with small children, and for older adults.

Concerns about children in prison either came from those caring for the women’s children outside prison walls, the women themselves, or their children. Karnchana conveyed that her auntie, who was caring for her child, “doesn’t want the baby to get involved in anything bad. She didn’t allow the baby to come visit me.” Jasmine did not want her child to see her in prison. She explained, “I don’t want him [my baby] to see me like this.” Sumalee’s grandchild would not visit because facing his grandmother/primary caregiver in prison was emotionally distressing.

Finally, for some women, loved ones simply disappeared. Hanuman explained, “my first child used to visit me a lot. But now he is disappeared. Both him and his girlfriend. They are gone for two months now.” Kalaya’s adult daughter “disappeared too.” She explained, “The last time she visited me was in February [six months ago]. But now she’s gone. I can’t contact her.” Ammara “wrote a few letters asking my boyfriend to visit but he never replied,” and Benyapa’s “mother was gone, I have no one.”

6.4. Rehabilitative Programmes and Support

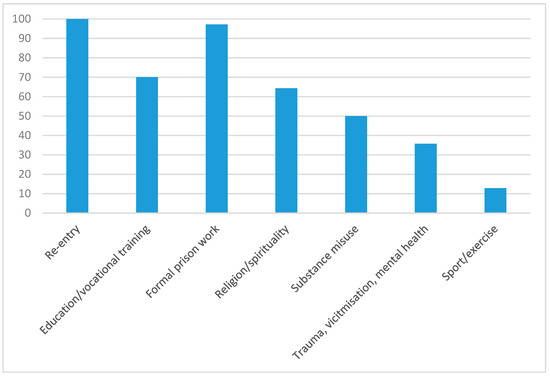

Prison authorities should be preparing women for re-entry from the beginning of their sentence, and ideally, support and programming should be targeted to address the factors that led women on a pathway to prison. For the women in this research, exploration of prison trajectories suggests programming/support aimed at addressing the following would be useful: substance misuse, victimisation, mental health and trauma recovery, and poverty, via meaningful educational, vocational, and work opportunities. Re-entry planning, programming, and connections to post-release support services/through-care are also vital.

A broad overview of women’s participation in programming/support is provided in Figure 3. Every woman participated in a re-entry programme, and most engaged in vocational/educational training, and/or formal work. Half had undertaken a substance abuse treatment programme. Support/programmes specifically concerned with victimisation, mental health, and trauma recovery were limited. However, it is important to note that religious programmes, sport, exercise, vocational/educational training, work, and substance abuse treatment programmes all had a role to play in women’s emotional well-being. Each are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 3.

Women’s participation in prison programmes/support.