Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Diffusion Bonded Joint

Abstract

1. Introduction

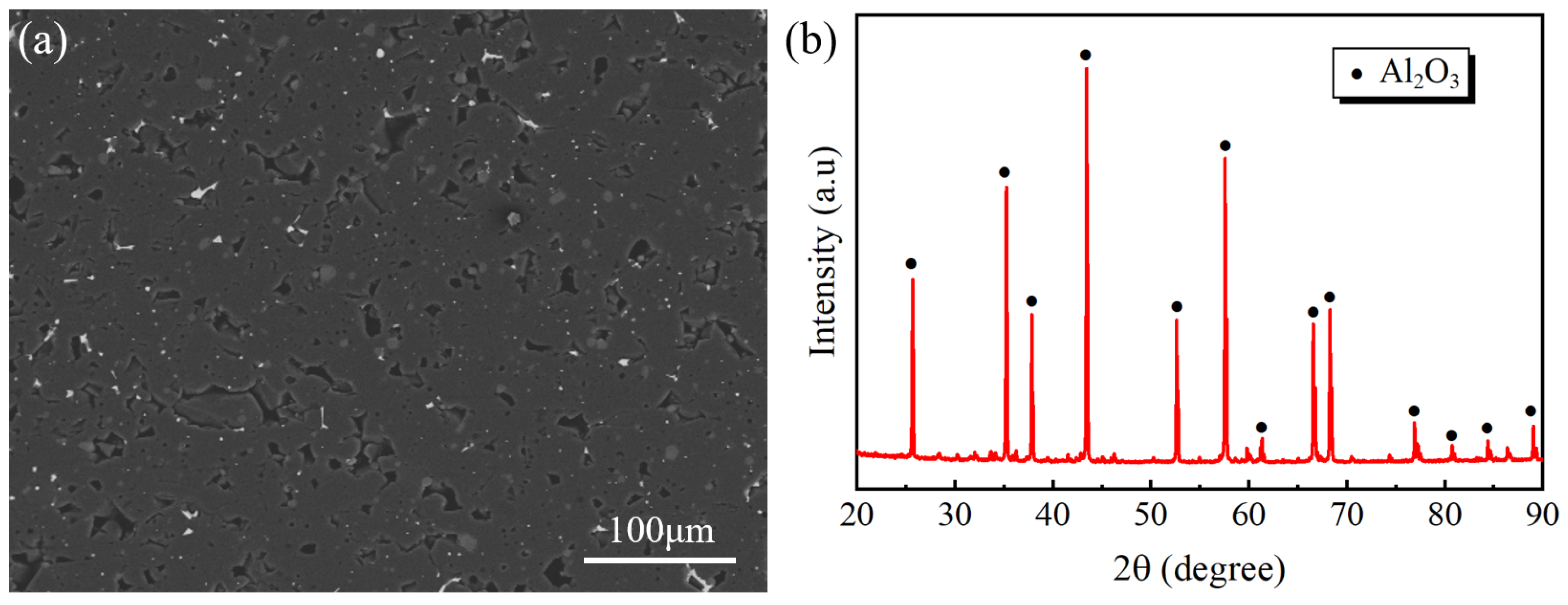

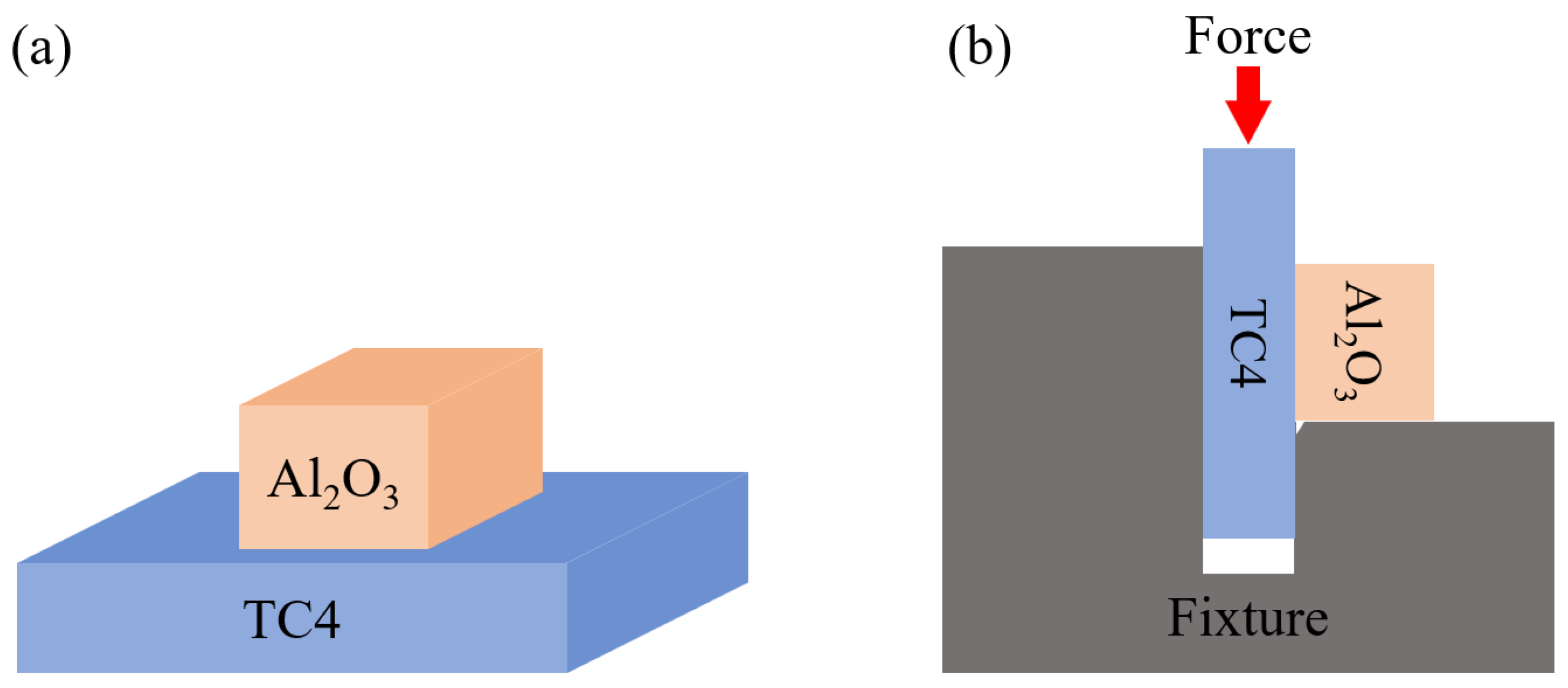

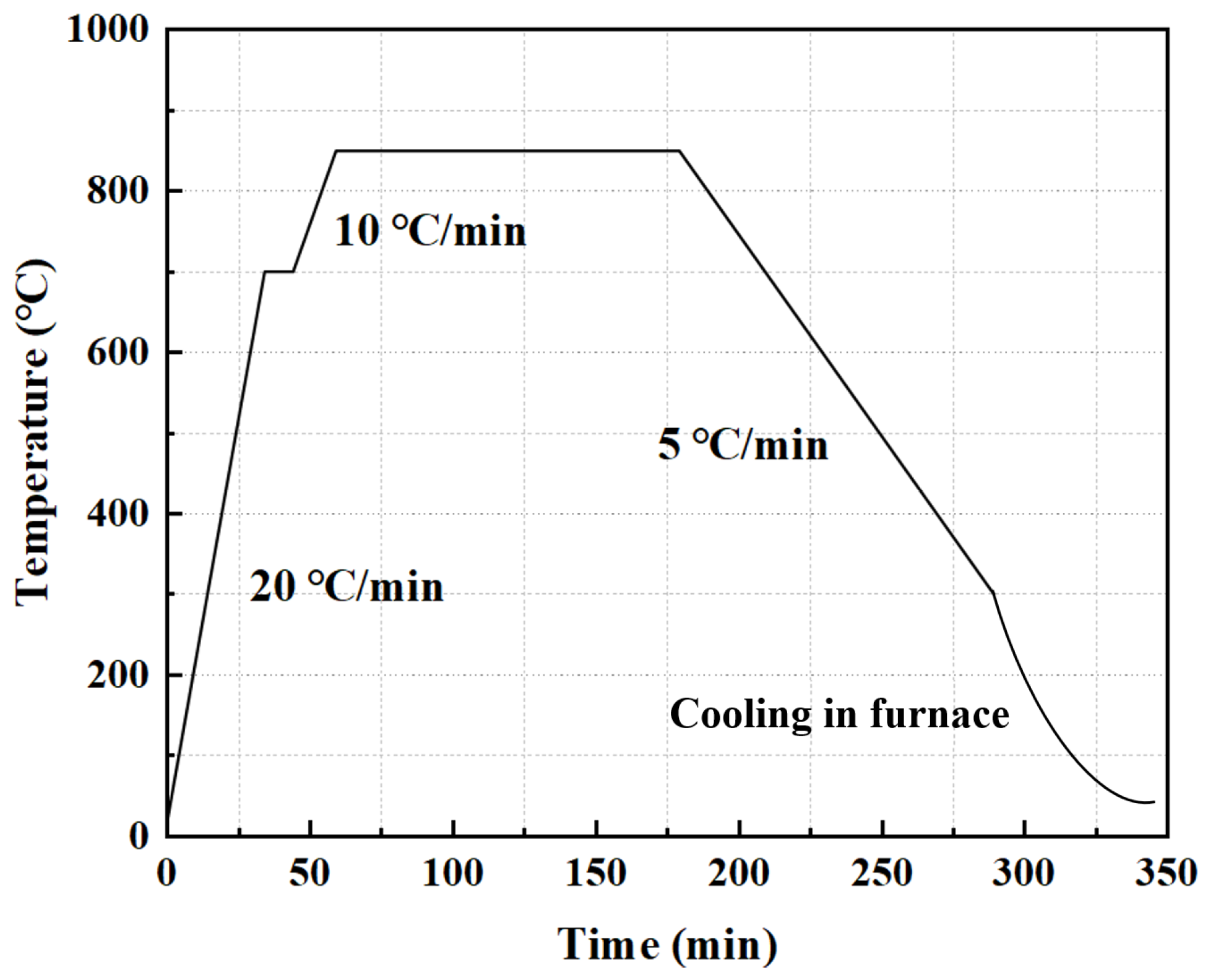

2. Materials and Methods

3. Finite Element Modeling

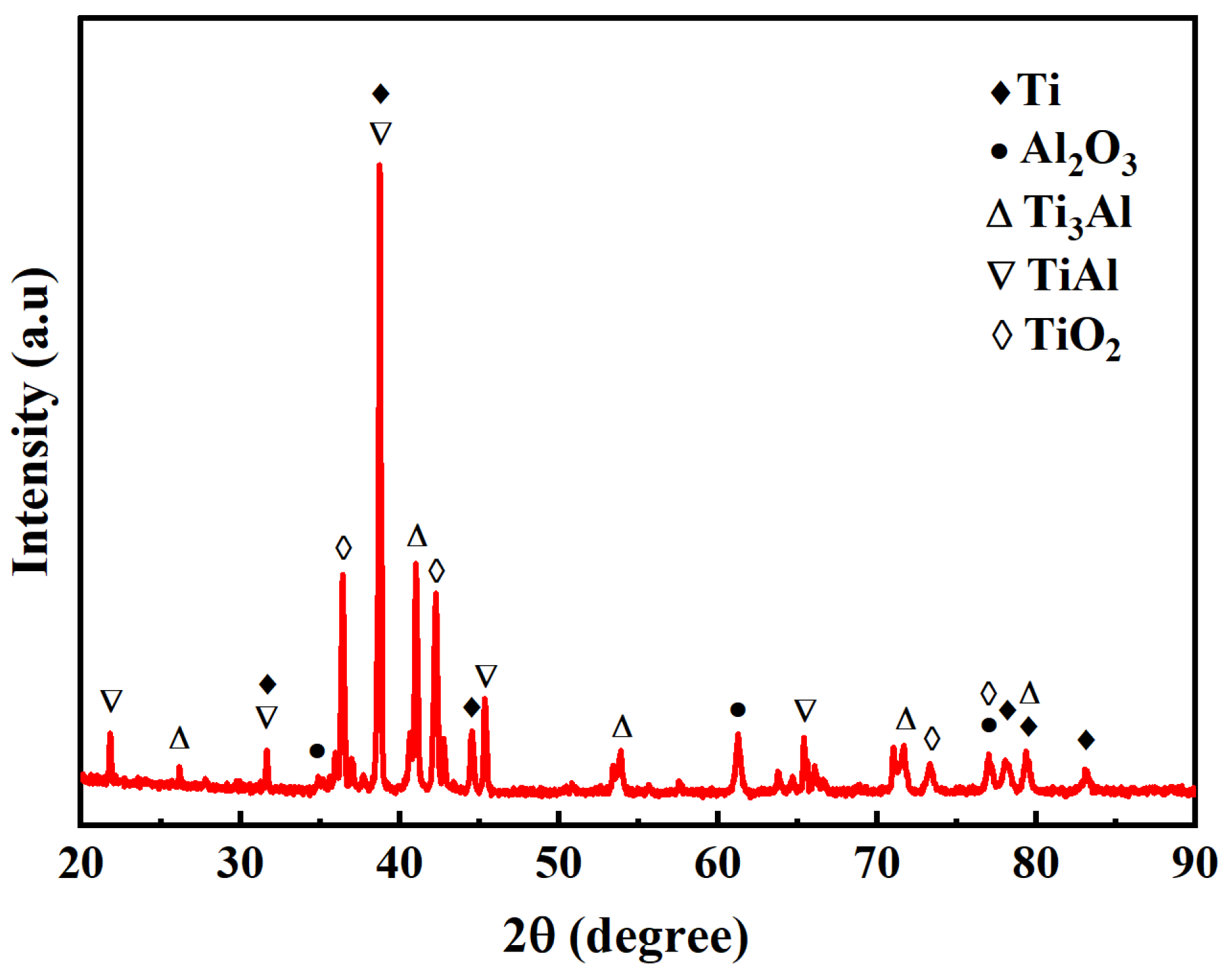

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Typical Joint Microstructure

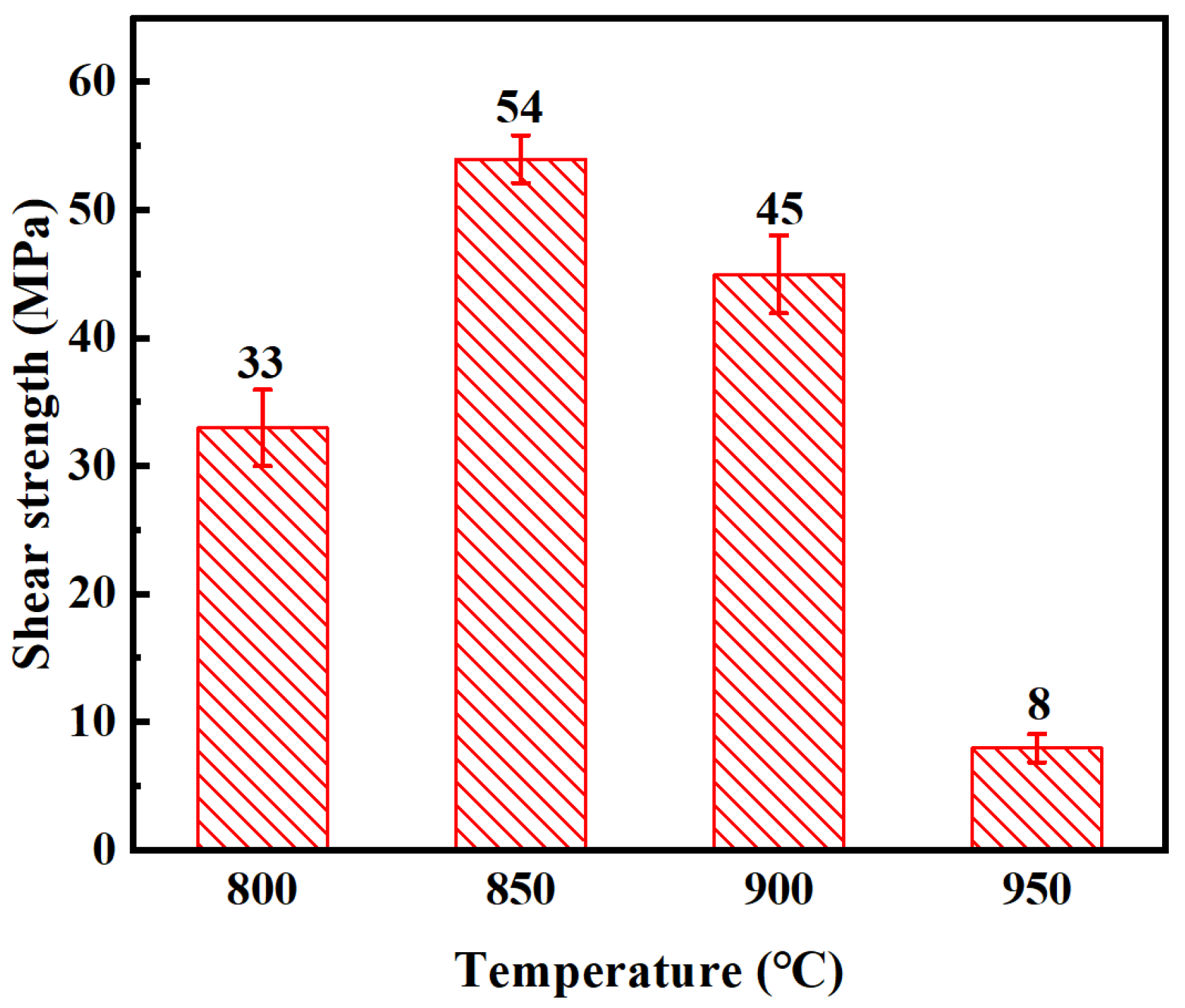

4.2. Microstructure Evolution and Shear Strength of Al2O3/TC4 Joints

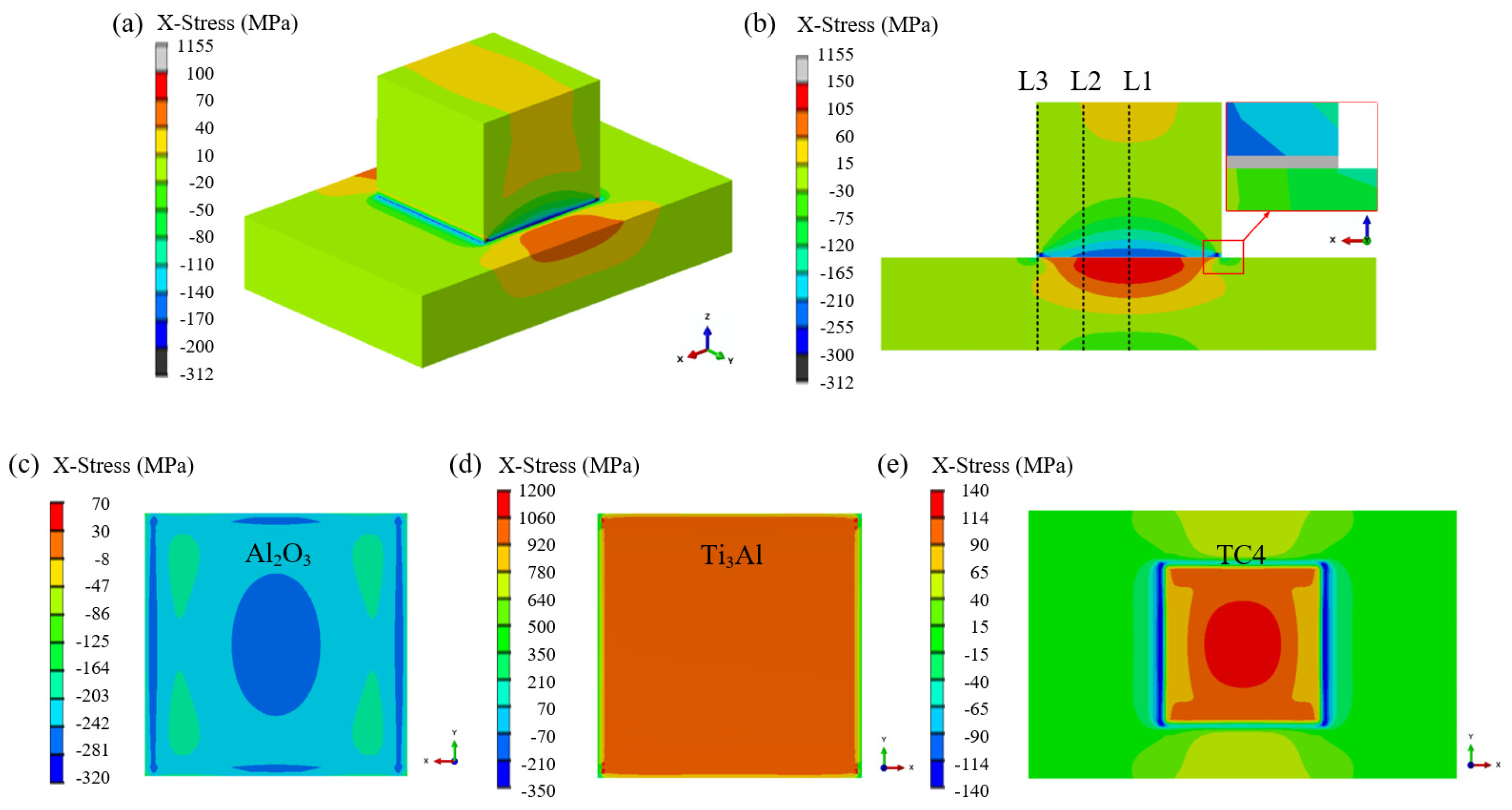

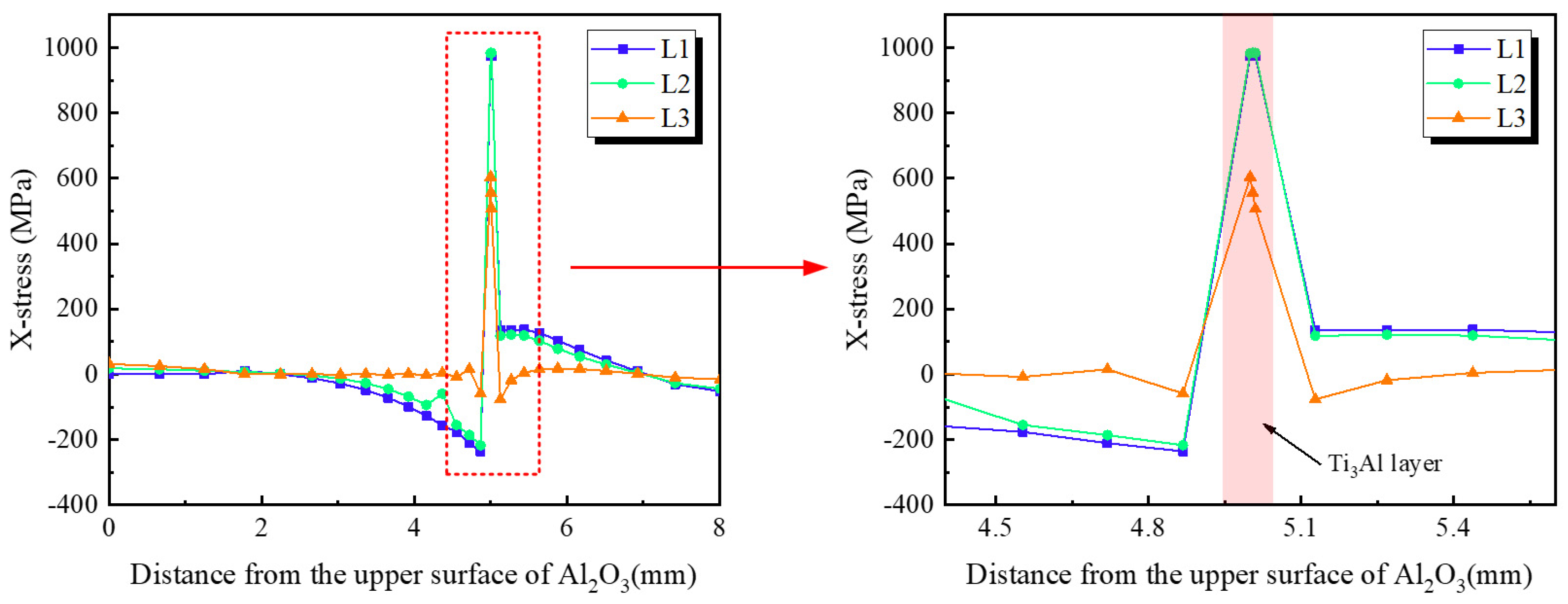

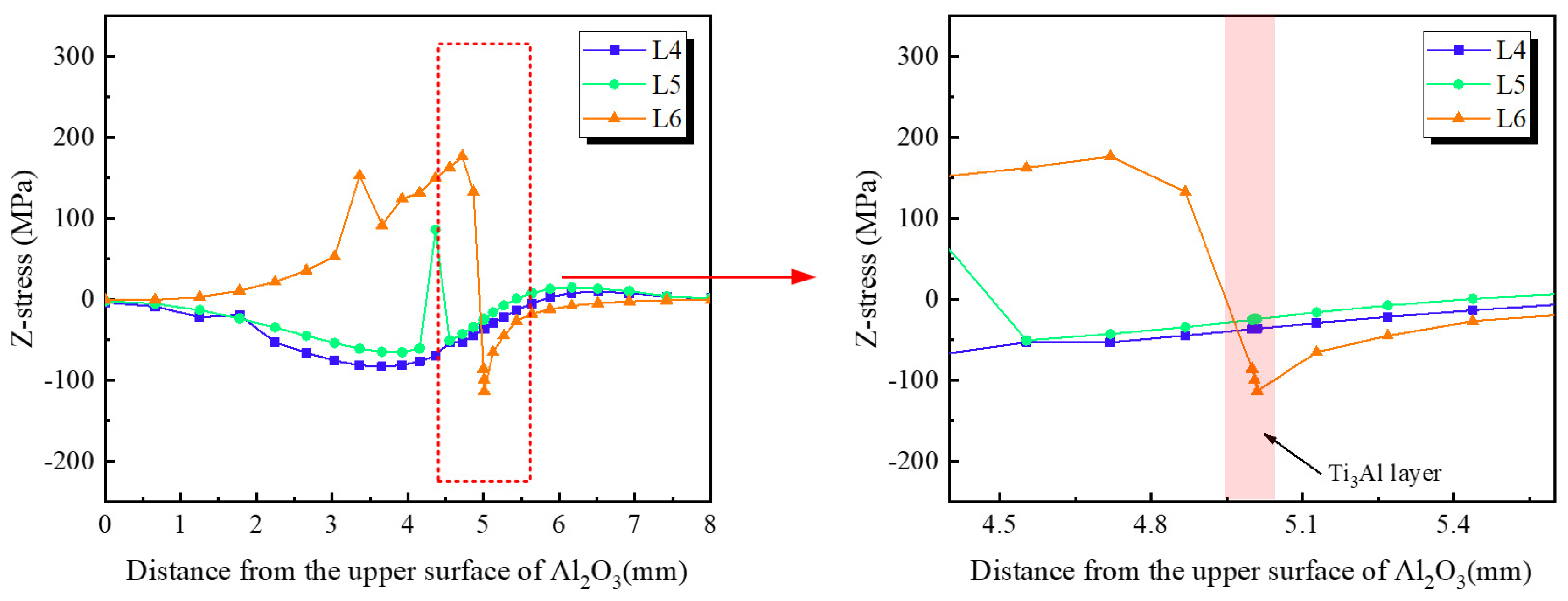

4.3. Residual Stress Prediction of the Al2O3/TC4 Diffusion Bonded Joint

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Reliable diffusion bonding of Al2O3 ceramic to TC4 alloy was achieved. The interfacial microstructure consists of a Ti3Al reaction layer and a fine-grained region within the adjacent TC4 substrate. With increasing bonding temperature, enhanced atomic interdiffusion promotes the growth of the Ti3Al layer, while the fine-grained zone progressively diminishes due to the dominance of grain growth over strain-induced refinement at elevated temperatures.

- (2)

- The joint shear strength shows a strong dependence on bonding temperature, attaining a maximum value of 54 MPa at 850 °C. Beyond this temperature, excessive thickening of the brittle Ti3Al reaction layer leads to pronounced residual stresses and interfacial cracking, resulting in significant degradation of mechanical performance.

- (3)

- Finite-element simulations confirm that residual stresses originate primarily from the CTE mismatch among Al2O3, Ti3Al, and TC4. The Ti3Al layer experiences the highest tensile stress in the X-direction (~980 MPa), whereas the Al2O3 ceramic near the interface is subjected to compressive stresses. In the Z-direction, tensile stress concentrations are localized along the vertical edges of the ceramic, representing potential sites for crack initiation during mechanical loading.

- (4)

- These findings highlight the necessity of balancing interfacial reaction layer growth with residual stress control in the design of Al2O3/TC4 joints. Optimizing the bonding temperature to regulate the Ti3Al layer thickness, together with geometrical or processing strategies to alleviate edge stress concentrations, is essential for improving the structural integrity and reliability of such hybrid joints.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, Z.; Dong, R.; Li, J.; Su, Y.; Long, X. Determination of Gradient Residual Stress for Elastoplastic Materials by Nanoindentation. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 109, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Gu, J.; Shi, H.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, G. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties Analysis of TiAl Joints Using Novel Brazing Filler Metal. Weld. World 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xie, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Ni, Z.; Ling, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Numerical Simulation and Process Optimization of Laser Welding in 6056 Aluminum Alloy T-Joints. Crystals 2025, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Qian, X.; Li, Y.; Qiang, D.; Shao, C.; Cheng, L.; Ding, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, D.; et al. Printable Fabrication of High-Temperature Electrical Insulating Layers on TC4 Titanium Alloy for Thin-Film Sensor Applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1044, 184443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Jin, J.; Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Mu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Preparation and Toughening Mechanism of Al2O3 Composite Ceramics Toughened by B4C@TiB2 Core-Shell Units. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 2371–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Pan, S.; Chai, X. Enhanced Strength and High-Temperature Wear Resistance of Ti6Al4V Alloy Fabricated by Laser Solid Forming. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng.-Trans. ASME 2022, 144, 111011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Feng, G.; Cao, J.; Zhang, H.; Deng, D. Characterization of ZTA Composite Ceramic/Ti6Al4V Alloy Joints Brazed by AgCu Filler Alloy Reinforced with One-Dimensional Al18B4O33 Single Crystal. Crystals 2022, 12, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Yi, R.; He, L. The Brazing of Al2O3 Ceramic and Other Materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.; Zeeshan, M.D.; Ansari, M.I.; Sharma, D. Progress in Tribological Research of Al2O3 Ceramics: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 82, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Han, G.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Li, J. Preparation of High Performance Dense Al2O3 Ceramics by Digital Light Processing 3D Printing Technology. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 2083–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Direct Laser Melting of Al2O3 Ceramic Paste for Application in Ceramic Additive Manufacturing. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 14273–14280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, W.; Yu, D.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Fang, R.; Ouyang, P. Effect of Ti Content on Microstructure and Properties of Cu/AgCuTi/Al2O3 Brazed Joints. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, X. Brazing of Al2O3-6061 Aluminum Alloy Based on Femtosecond Laser Surface Groove Structure. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 36953–36960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, J.; Li, S.; Xiong, J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al2O3 Ceramic and Ti2AlNb Alloy Joints Brazed with Al2O3 Particles Reinforced Ag–Cu Filler Metal. Vacuum 2021, 192, 110430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Li, Z.; He, P.; Shen, L.; Zhou, Z. Laser-Induced Combustion Joining of Cf/Al Composites and TC4 Alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Wei, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, Y.; Deng, D.; Yang, X. Vacuum Diffusion Bonding of Ti2AlNb Alloy and TC4 Alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Qi, F.; Sun, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Vacuum Diffusion Bonded Zr-4 Alloy Joint. Crystals 2021, 11, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wen, Z.; Chang, M.; Feng, G.; Deng, D. Fabrication of Reliable ZTA Composite/Ti6Al4V Alloy Joints via Vacuum Brazing Method: Microstructural Evolution, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 4273–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Li, Z.; Feng, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, P. Self-Propagating Synthesis Joining of Cf/Al Composites and TC4 Alloy Using AgCu Filler with Ni-Al-Zr Interlayer. Rare Met. 2021, 40, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, D.; Li, H. Compound Connection Mechanism of Al2O3 Ceramic and TC4 Ti Alloy with Different Joining Modes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Lin, T.; He, P.; Huang, Y. Brazing of Al2O3 to Ti–6Al–4V alloy with in situ synthesized TiB-whisker-reinforced active brazing alloy. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 3029–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, K.-Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.-C.; Meng, X.; Liang, L.; Liu, P.; Wang, X. Effects of Ti Migration on the Microstructure and Properties of Al2O3/Ti Brazing Interfaces in Accelerator Tubes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 64910–64920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Huang, X.; Zou, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Mao, Y. Joining of Al2O3 Ceramic to Cu Using Refractory Metal Foil. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 3455–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; He, L.; Yi, R. Investigation of Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of 2024 Al/Al2O3 Ceramic Joints. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2022, 27, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.Q.; Wang, D.P.; Qi, F.G.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Q.W.; Yang, Z.W. Joining of Titanium Diboride-Based Ultra High-Temperature Ceramics to Refractory Metal Tantalum Using Diffusion Bonding Technology. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, F.A.; Khan, N.Z.; Parvez, S. Recent Advances and Development in Joining Ceramics to Metals. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 6570–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Wang, G.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; He, R.; Tan, C. Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of SiC and Nb Joint Brazed with AgCuTi/(Sr0.2Ba0.8)TiO3-Cu/AgCuTi Composite Fillers. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 34005–34016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Qin, B.; Lin, J.; Cao, J.; Qi, J.; Feng, J. Regulating the Interfacial Reaction of Sc2W3O12/AgCuTi Composite Filler by Introducing a Carbon Barrier Layer. Carbon 2022, 191, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.G.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Hu, S.P.; Lin, D.Y.; Chen, N.B.; Liu, D.; Long, W.M. Brazing of SiC Ceramic to Al0.3CoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy by Graphene Nanoplates Reinforced AgCuTi Composite Fillers. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 19216–19226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Chen, X.; Xie, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Wu, M.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Interfacial Microstructural Evolution and Residual Stress Modulation in SiC/Kovar Joints Using TiC-Reinforced AgCuTi Filler: Experiment and Finite Element Modeling. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 59149–59160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Wang, M.R.; Cao, J.; Song, X.G.; Tang, D.Y.; Feng, J.C. Brazing TC4 Alloy to Si3N4 Ceramic Using Nano-Si3N4 Reinforced AgCu Composite Filler. Mater. Des. 2015, 76, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Song, X.G.; Zhou, W.L.; Fu, W.; Song, Y.Y.; Long, F.; Qin, J.; Hu, S.P. Microstructure evolution and shear strength optimization in SiC ceramic/MA956 ODS steel joints brazed with Cu-5Ti filler. Mater. Charact. 2025, 225, 115107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.B.; Wang, D.P.; Yang, Z.W.; Wang, Y. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al2O3/TiAl Joints Brazed with B Powders Reinforced Ag-Cu-Ti Based Composite Fillers. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lin, T.; He, P.; Zhu, M.; Song, C.; Jia, D.; Feng, J. Microstructural Evolution and Growth Behavior of In Situ TiB Whisker Array in ZrB2-SiC/Ti6Al4V Brazing Joints. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 3712–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B. Recent Advances in Brazing Fillers for Joining of Dissimilar Materials. Metals 2021, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.; Willingham, J.; Goodall, R. Brazing Filler Metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 2020, 65, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Ramos, A.S.; Vieira, M.T.; Simoes, S. Diffusion Bonding of Ti6Al4V to Al2O3 Using Ni/Ti Reactive Multilayers. Metals 2021, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M., Jr.; Ramos, A.S.; Simoes, S. Joining Ti6Al4V to Alumina by Diffusion Bonding Using Titanium Interlayers. Metals 2021, 11, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. Interfacial Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Joints Diffusion Bonded with an Aluminum Interlayer. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 64744–64758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitt, H.A.; Shechtman, D.; Schafrik, R.E. The Deformation and Fracture of Ti3Al at Elevated Temperatures. Met. Trans. A 1980, 11, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikala, H.; Suryanarayana, S.; Murthy, K.; Naidu, S. Thermal-Expansion Characteristics of Ti3Al and the Effect of Additives. J. Less-Common Met. 1989, 155, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar’kina, L.E.; Elkina, O.A.; Yakovenkova, L.I. Dislocation Structure of Intermetallic Ti3Al Subjected to High-Temperature Deformation. Phys. Solid. State 2008, 50, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, X.; Li, L.; Guo, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J. Comparison of the Laser-Repairing Features of TC4 Titanium Alloy with Different Repaired Layers. Crystals 2023, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Feng, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Deng, D. Influence of Lumping Passes on Calculation Accuracy and Efficiency of Welding Residual Stress of Thick-Plate Butt Joint in Boiling Water Reactor. Eng. Struct. 2020, 222, 111136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, G.; Pu, X.; Deng, D. Influence of Welding Sequence on Residual Stress Distribution and Deformation in Q345 Steel H-Section Butt-Welded Joint. J. Mater. Res. Technol. JMRT 2021, 13, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Wang, Y.; Luo, W.; Hu, L.; Deng, D. Comparison of Welding Residual Stress and Deformation Induced by Local Vacuum Electron Beam Welding and Metal Active Gas Arc Welding in a Stainless Steel Thick-Plate Joint. J. Mater. Res. Technol. JMRT 2021, 13, 1967–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, P.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Du, W.; Wang, L. Microstructure Evolution Mechanisms Endowing High Compression Strength Assisted by Stacking Fault-Twin Synergy in TiC/TC4 Alloy Nanocomposites Prepared by Laser Powder Bed Fusion under Hot Isostatic Pressing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 924, 147789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prithiv, T.S.; Bhuyan, P.; Pradhan, S.K.; Subramanya Sarma, V.; Mandal, S. A Critical Evaluation on Efficacy of Recrystallization vs. Strain Induced Boundary Migration in Achieving Grain Boundary Engineered Microstructure in a Ni-Base Superalloy. Acta Mater. 2018, 146, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Han, J.; Zhang, C. Interfacial Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of TiAl Alloy/TC4 Titanium Alloy Joints Diffusion Bonded with CoCuFeNiTiV0.6 High Entropy Alloy Interlayer. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 935, 167987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lei, Y.; Chen, L.; Ye, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Advances in Mechanism and Application of Diffusion Bonding of Titanium Alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2025, 337, 118736. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, W.; Fu, Y.; He, P.; Lin, T.; Feng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Phase Transformation Toughening Behaviors of T-ZrO2 Nanoparticles in Glass Sealing of YSZ Ceramic and Crofer22H Stainless Steel for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 525, 169928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.; Fu, Y.; He, P.; Lin, T.; Feng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Microstructure Evolution and Chromium Suppression Mechanism in Pre-Oxidized Ce/Co-Coated AISI 441 Stainless Steel for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Interconnects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 151044. [Google Scholar]

| Materials | Temperature (°C) | CTE (10−6/°C) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Density (g/cm3) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | 20 | 7.1 | - | 355 | 3.62 | 0.27 |

| 200 | 7.2 | 348 | ||||

| 400 | 7.3 | 343 | ||||

| 600 | 7.6 | 333 | ||||

| 800 | 7.8 | 325 | ||||

| 1000 | 8.0 | 315 | ||||

| TC4 | 20 | 8.82 | 870 | 117 | 4.43 | 0.32 |

| 75 | 8.90 | 820 | 116 | 0.32 | ||

| 85 | 8.90 | 750 | 116 | 0.32 | ||

| 100 | 8.93 | 340 | 115 | 0.32 | ||

| 200 | 9.08 | 130 | 113 | 0.32 | ||

| 400 | 9.43 | 78 | 107 | 0.33 | ||

| 600 | 9.76 | 54 | 101 | 0.33 | ||

| 800 | 10.1 | 31 | 95 | 0.33 | ||

| 1000 | 10.4 | 12 | 89 | 0.34 | ||

| Ti3Al | 20 | 9.60 | 1009 | 148 | 4.30 | 0.32 |

| 200 | 11.19 | 1135 | 147 | |||

| 400 | 12.58 | 1602 | 133 | |||

| 600 | 13.58 | 1788 | 112 | |||

| 800 | 14.19 | 1497 | 73 | |||

| 1000 | 14.40 | 404 | 25 |

| Spot | Ti | Al | V | O | Possible Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 55.09 | 31.04 | 1.91 | 11.93 | TiO2 + TiAl |

| B | 80.40 | 17.54 | 2.06 | - | Ti3Al |

| C | 89.34 | 7.86 | 2.80 | - | α-Ti |

| D | 85.74 | 5.13 | 9.13 | - | β-Ti |

| E | 91.53 | 6.49 | 1.98 | - | α-Ti |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fu, Y.; Cong, D.; Hu, T.; Feng, G.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.; Yi, Z.; Yu, G.; Cong, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Diffusion Bonded Joint. Metals 2026, 16, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020189

Fu Y, Cong D, Hu T, Feng G, Li Z, Chen D, Yi Z, Yu G, Cong W, Wang Y, et al. Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Diffusion Bonded Joint. Metals. 2026; 16(2):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020189

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Yangfan, Dalong Cong, Tao Hu, Guangjie Feng, Zhongsheng Li, Dajun Chen, Zaijun Yi, Guangyu Yu, Wei Cong, Yifeng Wang, and et al. 2026. "Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Diffusion Bonded Joint" Metals 16, no. 2: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020189

APA StyleFu, Y., Cong, D., Hu, T., Feng, G., Li, Z., Chen, D., Yi, Z., Yu, G., Cong, W., Wang, Y., & Deng, D. (2026). Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress Prediction of Al2O3 Ceramic/TC4 Alloy Diffusion Bonded Joint. Metals, 16(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020189