Assessing the Potential of Heterotrophic Bioleaching to Extract Metals from Mafic Tailings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling of Mafic Tailings

2.2. Isolation of Acid-Producing Bacteria from the Mafic Tailings

2.3. Screening for Organic Acid Production

2.4. Phylogenetic Identification of the Organic Acid-Producing Bacterial Isolates

2.5. Heterotrophic Bioleaching of the Mafic Tailings

2.6. Chemical Analyses

2.7. Morphological and Mineralogical Study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Primary Screening for Organic Acid-Producing Bacteria

3.2. Identification of the Isolates

3.3. Bioleaching of the Mafic Tailings

3.3.1. Variation in Optical Cell Density and pH Value

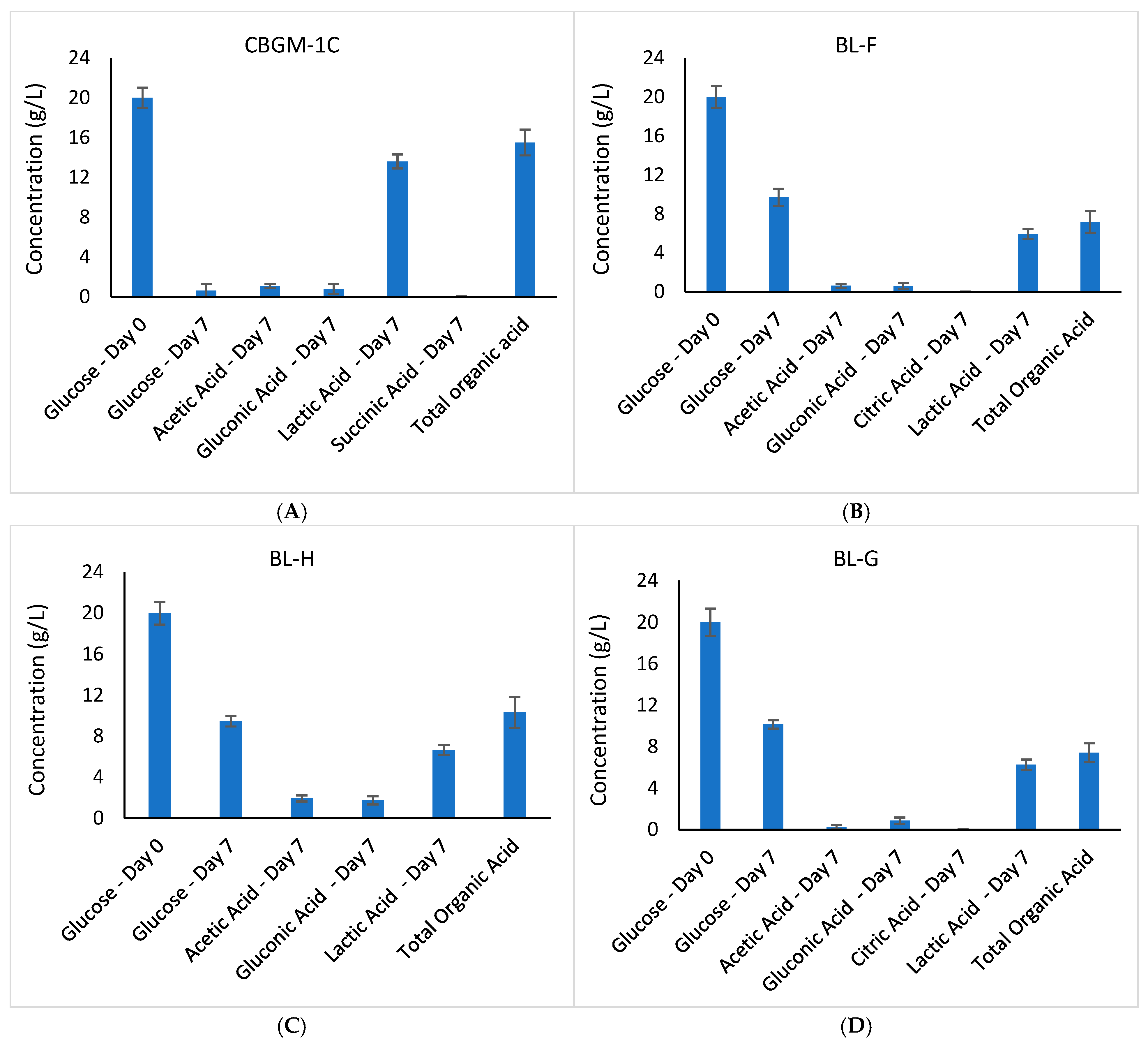

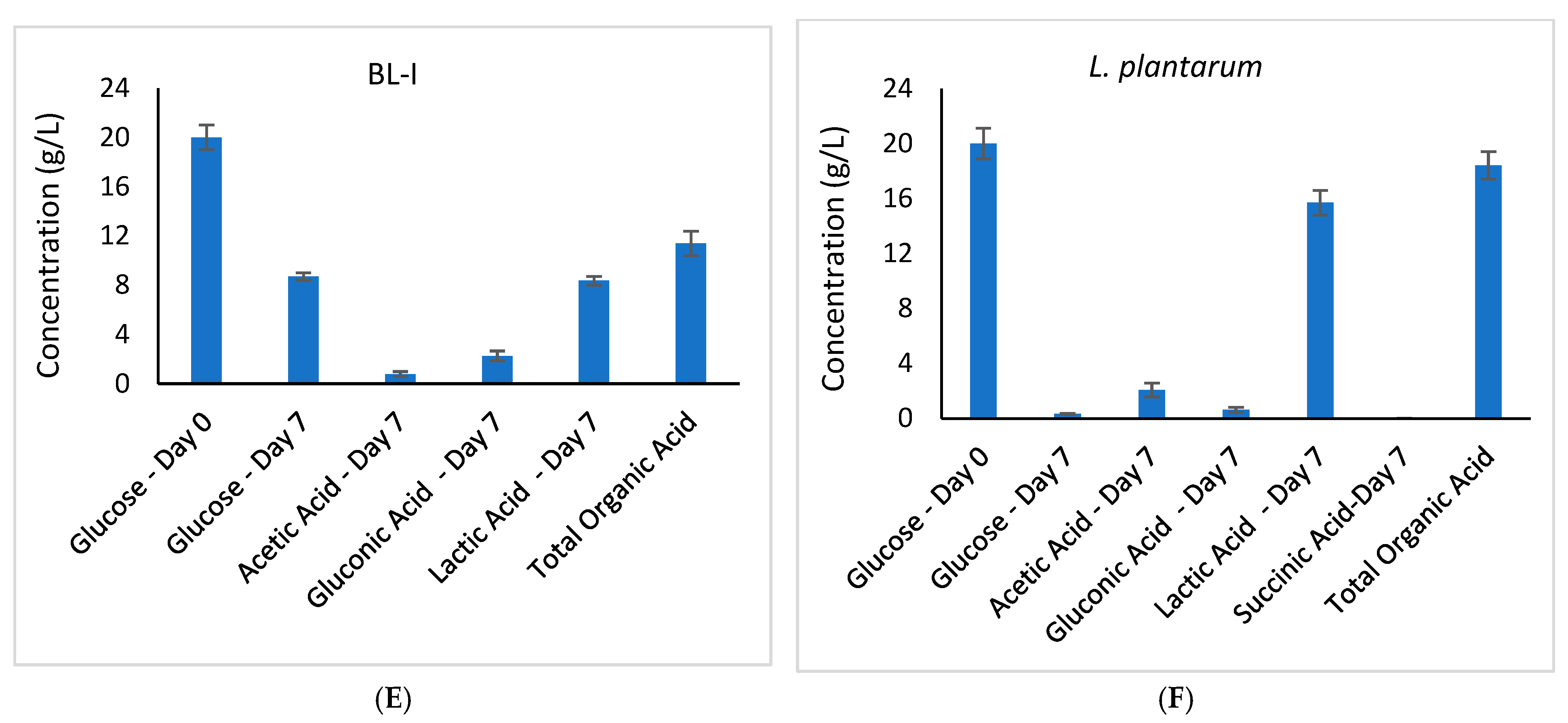

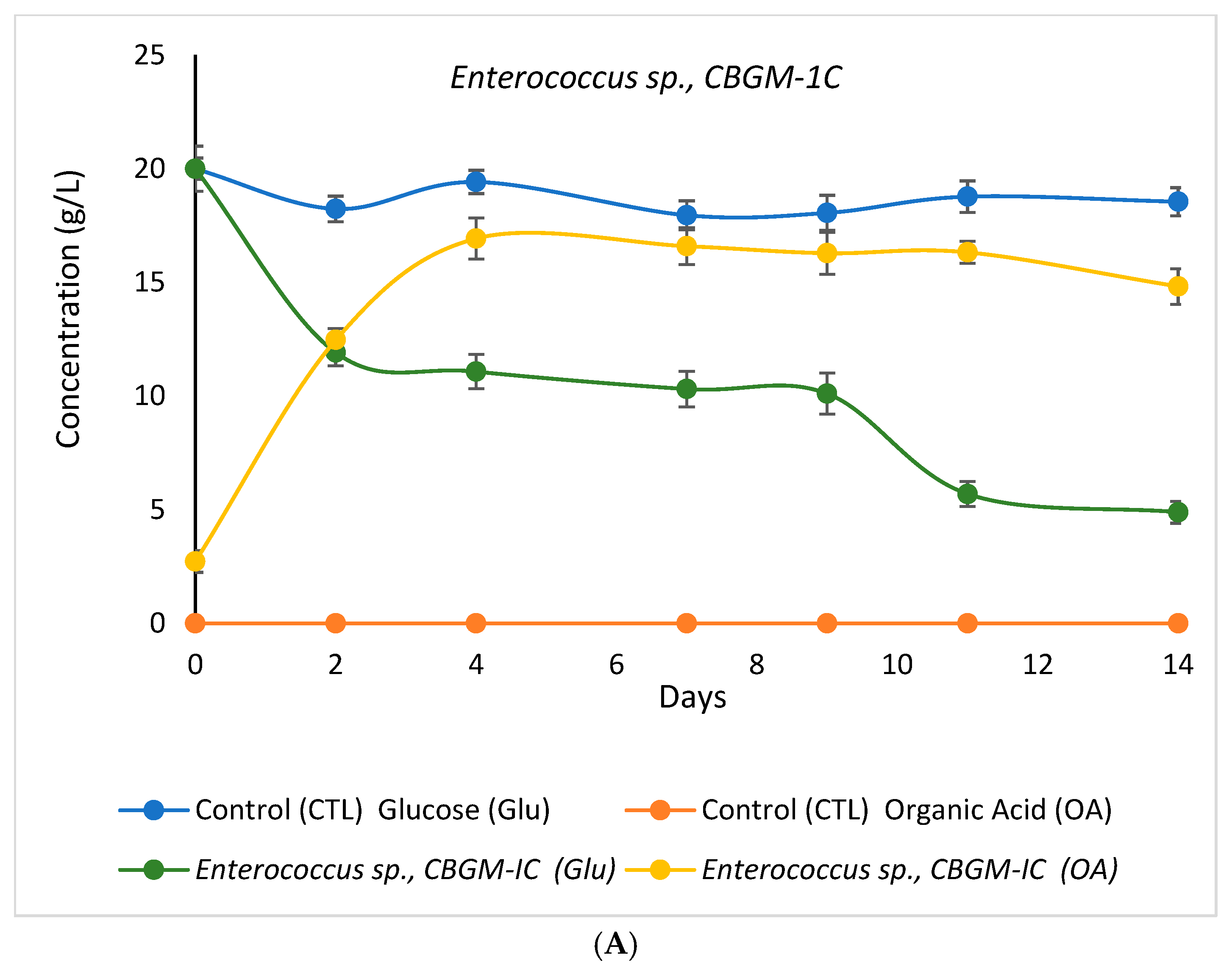

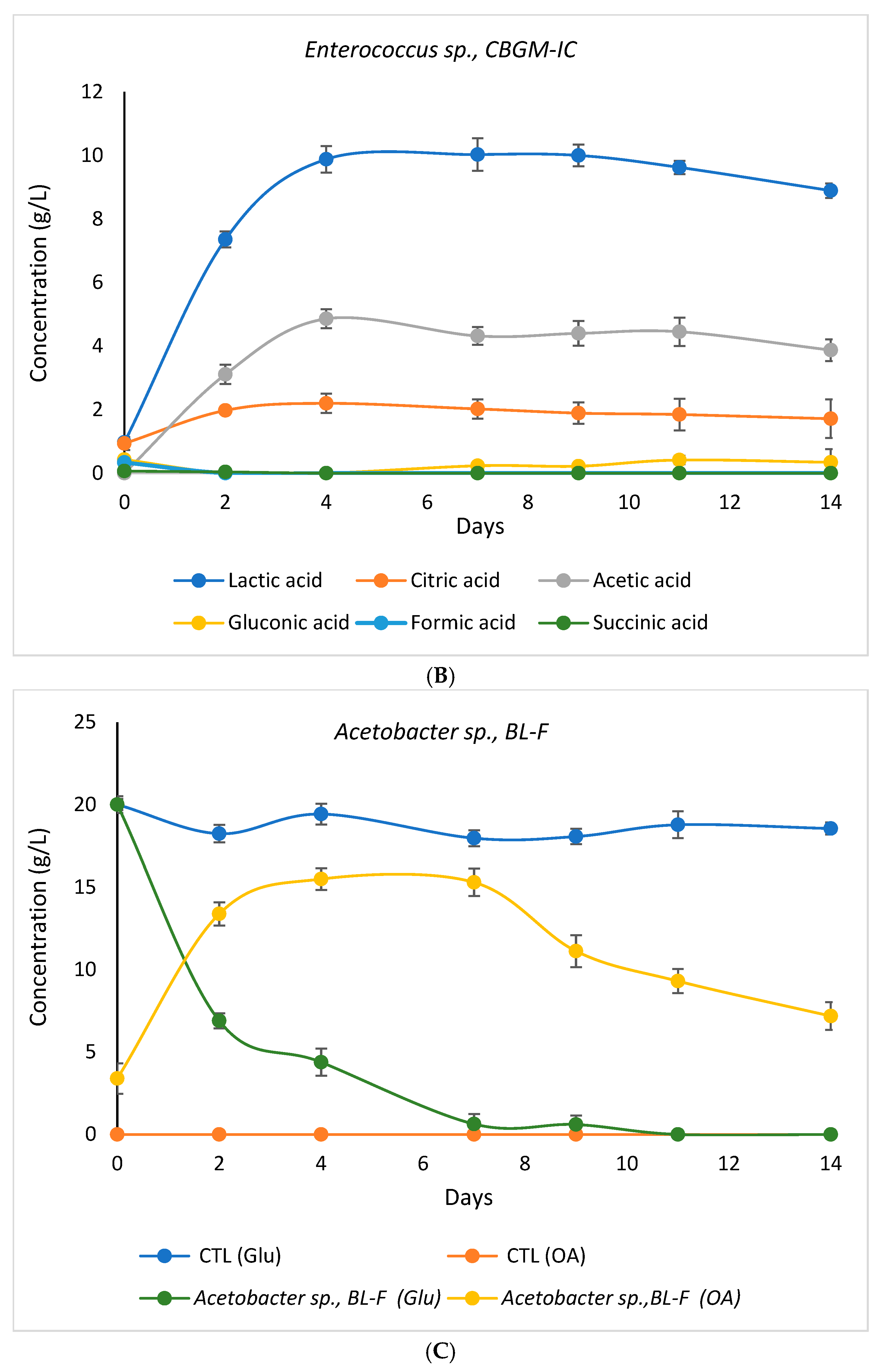

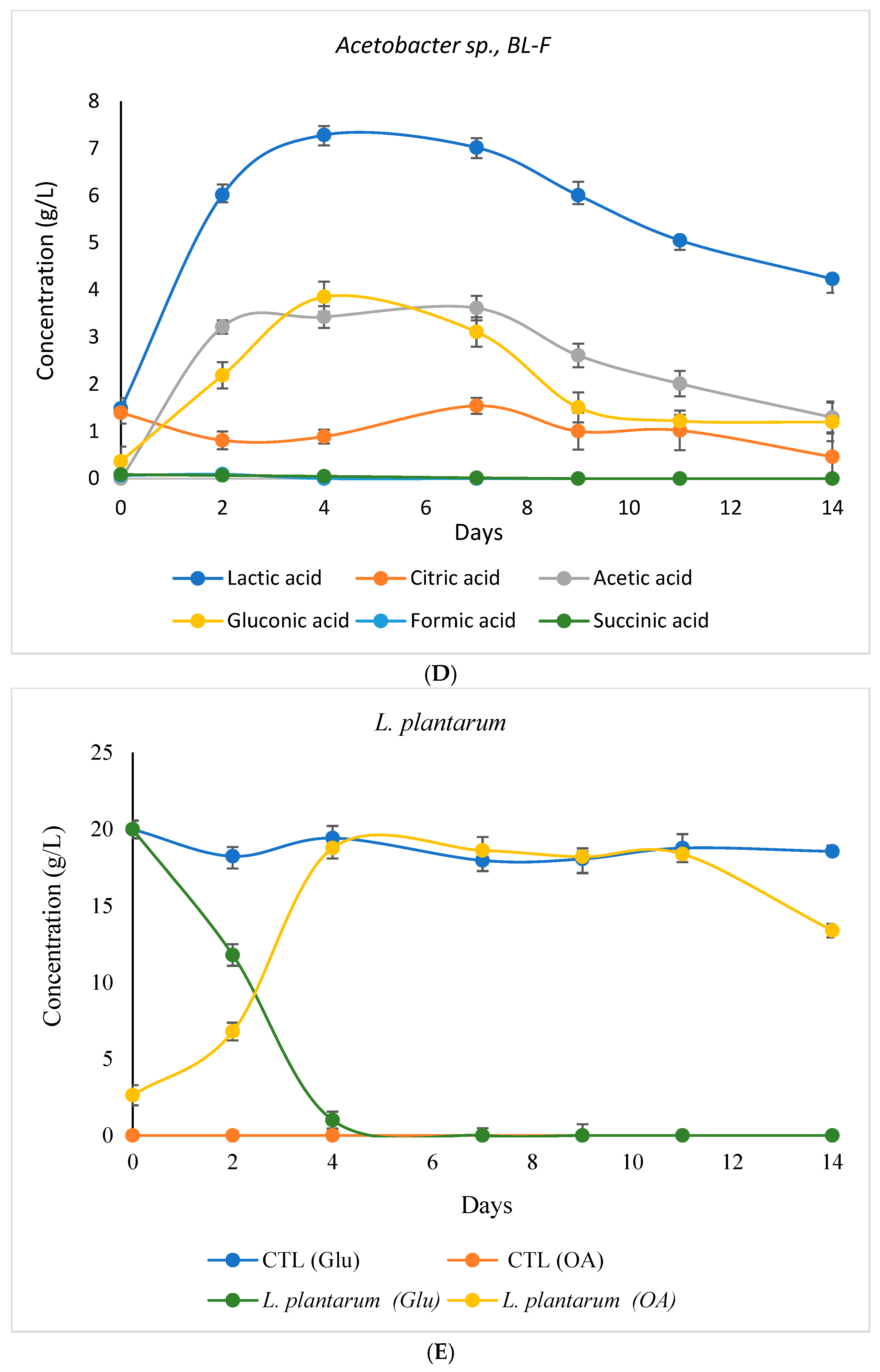

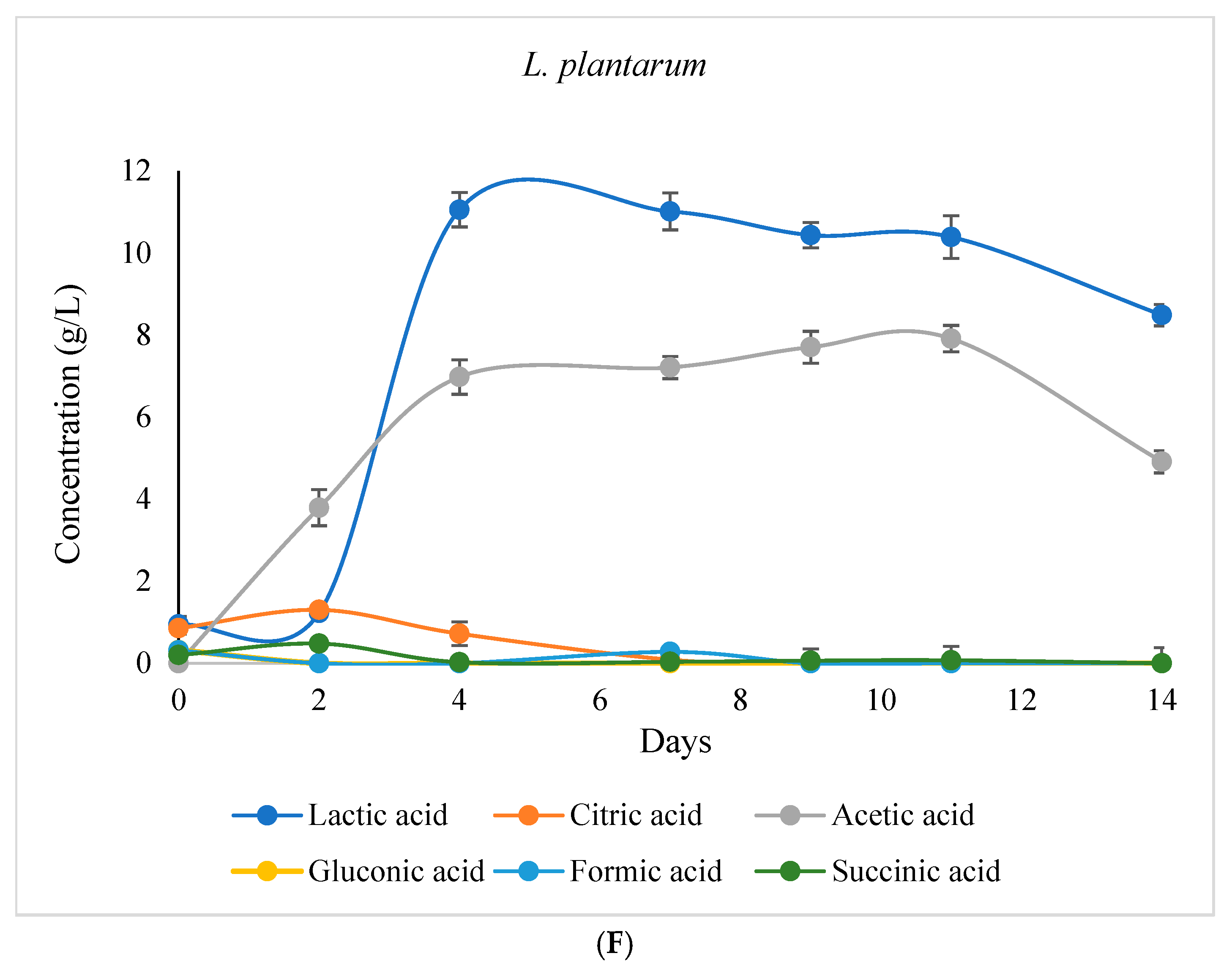

3.3.2. Variation in Glucose and Organic Acid Concentrations

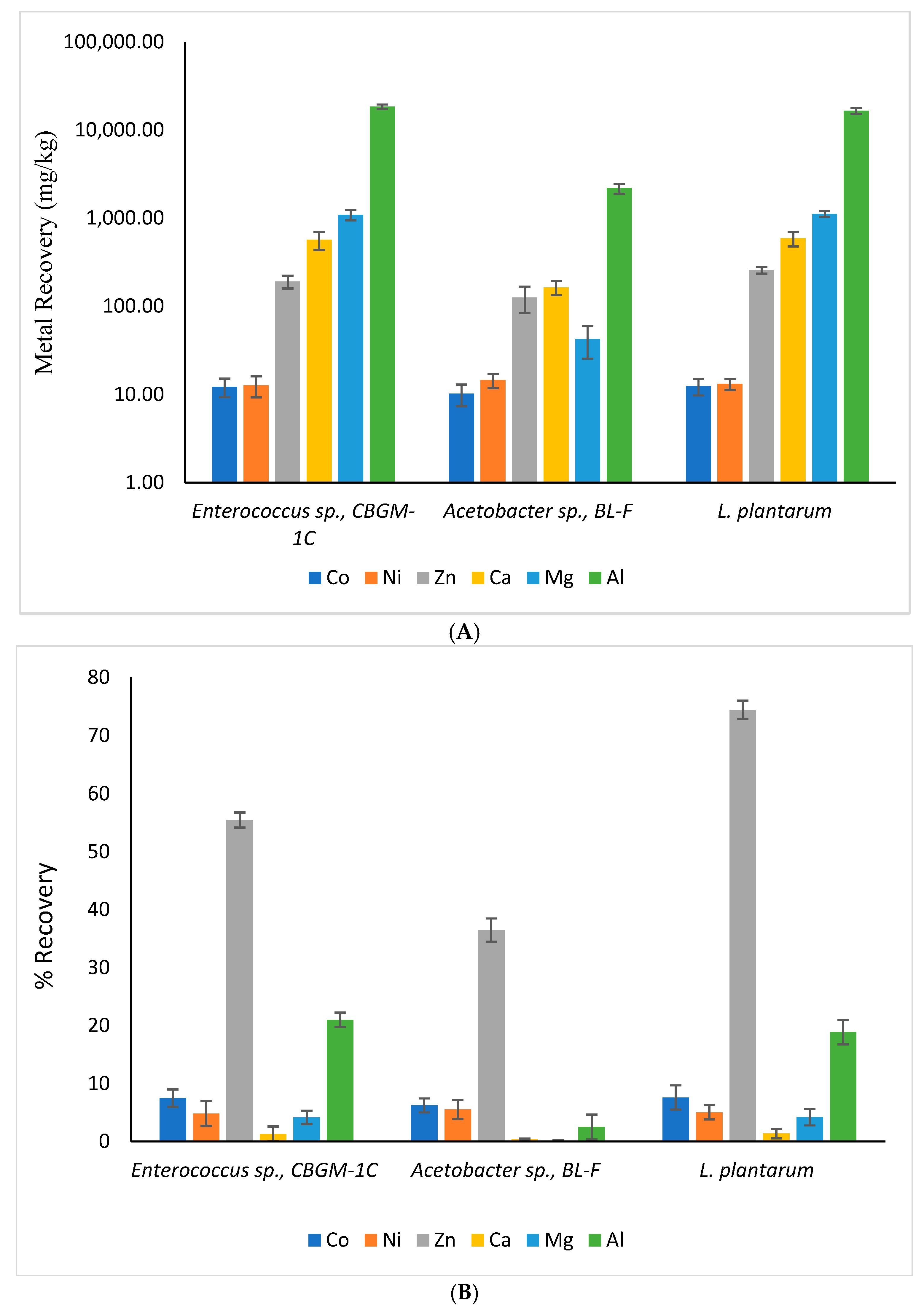

3.4. Recovery of Metals from the Mafic Tailings

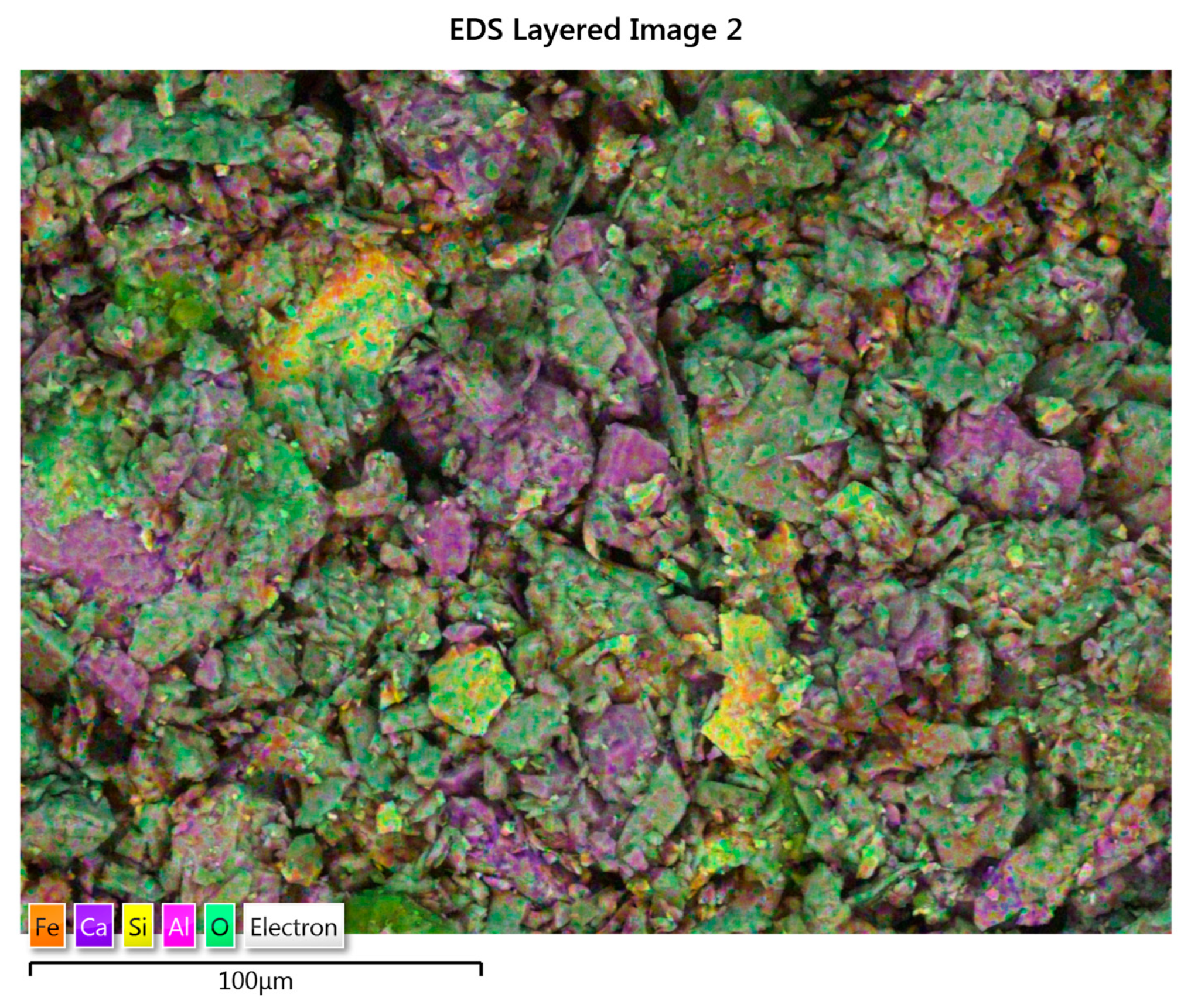

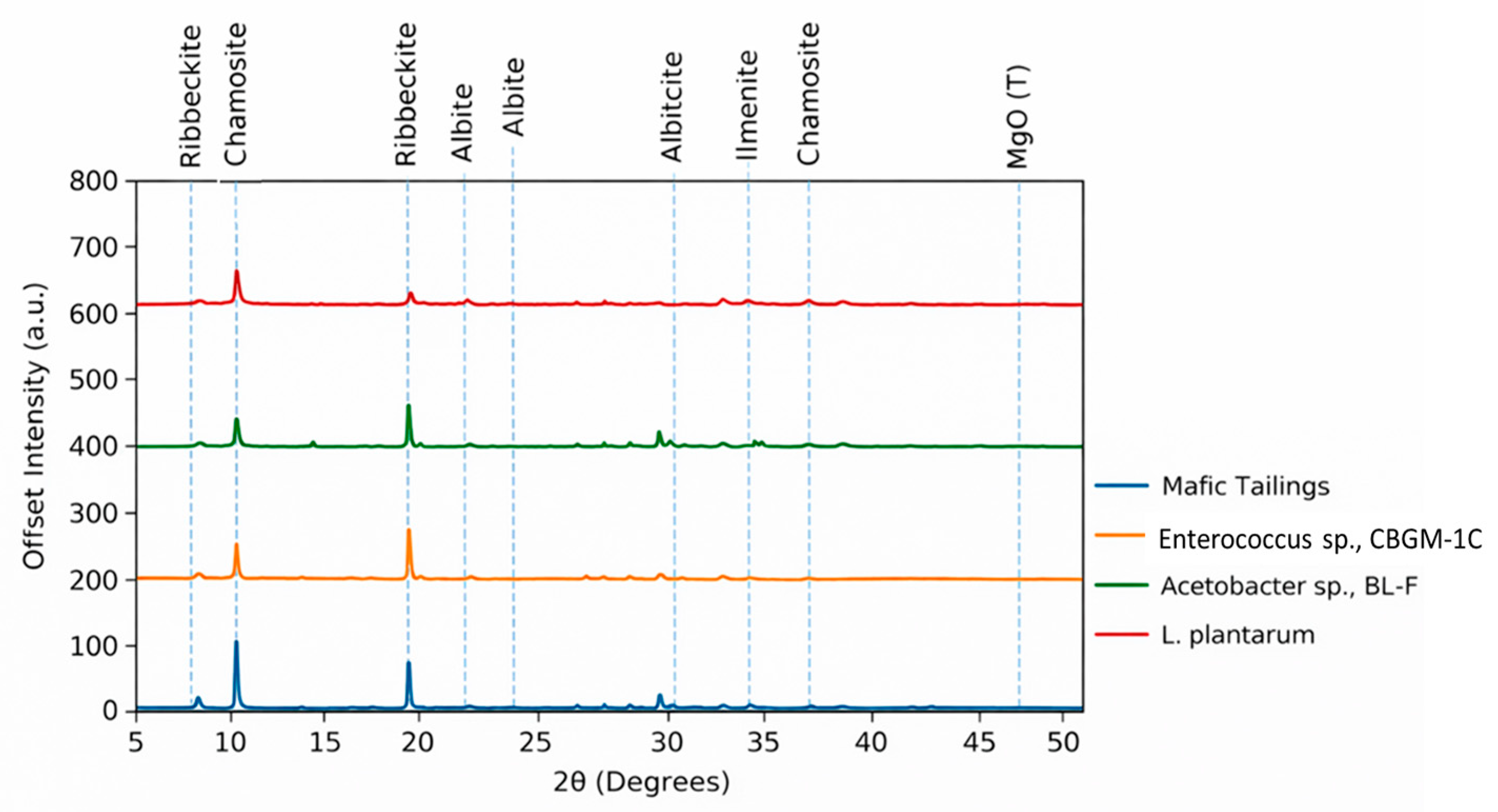

3.5. Minerological Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watari, T.; Nansai, K.; Nakajima, K. Major metals demand, supply, and environmental impacts to 2100: A critical review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024: U.S. Geological Survey; USGS Publications Warehouse: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; 212p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, T.; Nansai, K.; Nakajima, K. Review of critical metal dynamics to 2050 for 48 elements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backstrom, S.S.M. Sampling of Mining Waste—Historical Background, Experiences and Suggested Methods. 2018. Available online: https://resource.sgu.se/produkter/regeringsrapporter/2018/RR1805-appendix2.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Kursunoglu, S. A Review on the Recovery of Critical Metals from Mine and Mineral Processing Tailings: Recent Advances. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 2023–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Brar, K.K.; Asgarian, A.; Kaur, K.; Magdouli, S.; Perreault, N.N. Advancements in Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS): A Comprehensive Review of Technologies and Prospects. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebel, T.; Boon, N.; Maes, S.; Lenz, L. Biotechnologies for critical raw material recovery from primary and secondary sources: R&D priorities and future perspectives. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirete, S.; Morgante, V.; González-Pastor, J.E. Acidophiles: Diversity and mechanisms of adaptation to acidic environments. In Adaption of Microbial Life to Environmental Extremes: Novel Research Results and Application; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.X.; Huang, L.N.; Méndez-García, C.; Kuang, J.L.; Hua, Z.S.; Liu, J.; Shu, W.S. Microbial communities, processes and functions in acid mine drainage ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 38, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Hedrich, S.; Römer, F.; Goldmann, D.; Schippers, A. Bioleaching of cobalt from Cu/Co-rich sulfidic mine tailings from the polymetallic Rammelsberg mine, Germany. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 197, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, K.K.; Magdouli, S.; Perreault, N.N.; Tanabene, R.; Brar, S.K. Reviving Riches: Unleashing Critical Minerals from Copper Smelter Slag Through Hybrid Bioleaching Approach. Minerals 2024, 14, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadi, A.; Mucsi, G. A review on complex utilization of mine tailings: Recovery of rare earth elements and residue valorization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, U.; Su, C.; Hocheng, H. Leaching of metals from printed circuit board powder by an Aspergillus niger culture supernatant and hydrogen peroxide. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 43442–43452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulnia, P.; Mousavi, S.M.; Rastegar, S.O.; Azargoshasb, H. Fungal leaching of valuable metals from a power plant residual ash using Penicillium simplicissimum: Evaluation of thermal pretreatment and different bioleaching methods. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtzel, J.; Ueberschaar, N.; Deckert-Gaudig, T.; Krause, K.; Deckert, V.; Gadd, G.M.; Kothe, E. Organic acids, siderophores, enzymes and mechanical pressure for black slate bioweathering with the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezyapar Kara, I.; Kremser, K.; Wagland, S.T.; Coulon, F. Bioleaching metal-bearing wastes and by-products for resource recovery: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 3329–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisinska, M.; Gajda, B.; Saternus, M.; Brozová, S.; Wojtal, T.; Rzelewska-Piekut, M. The effect of organic acids as leaching agents for hydrometallurgical recovery of metals from PCBs. Metalurgija 2022, 61, 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo Schueler, T.; Mettke, L.N.; Crutziger, F.; Rasenack, K.; Yagmurlu, B.; Goldmann, D. Leaching of Mine Tailings Flotation Fractions Using Inorganic and Organic Acids for Metals Extraction. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 3014–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willscher, S.; Bosecker, K. Studies on the leaching behaviour of heterotrophic microorganisms isolated from an alkaline slag dump. Hydrometallurgy 2003, 71, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Gao, B.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Lactobacillus pentosus enabled bioleaching of red mud at high pulp density and simultaneous production of lactic acid without supplementation of neutralizers. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, J.; Chen, C.; Yang, M.; Lu, J.; Zhang, B. Heterotrophic bioleaching of vanadium from low-grade stone coal by aerobic microbial consortium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, V.S.; de Souza Monteiro, A.; Júlio, A.D.L.; Queiroz, A.L.L.; Dos Santos, V.L. Diversity of metal-resistant and tensoactive-producing culturable heterotrophic bacteria isolated from a copper mine in Brazilian Amazonia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancucheo, I.; Johnson, D.B. Characteristics of an iron-reducing, moderately acidophilic Actinobacterium isolated from pyritic mine waste, and its potential role in mitigating mineral dissolution in mineral tailings deposits. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, P.; Németh, T.; Kis, V.K.; Mohai, I. Sorption of copper, zinc and lead on soil mineral phases. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; McLaren, R.G.; Cameron, K.C. Effect of pH on Zinc Sorption–Desorption by Soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 39, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, X.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Release and bioavailability of heavy metals in three typical mafic tailings under the action of Bacillus mucilaginosus and Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 5087–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Plante, L.; Pian, B.; Marecos, S.; Medin, S.A.; Klug, J.D.; Reid, M.C.; Gadikota Mudbhatkal, A. Transition of CO2 from Emissions to Sequestration During Chemical Weathering of Ultramafic and Mafic Mine Tailings. Minerals 2025, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, B. The bioleaching of boron waste for lithium, rubidium, and cesium extraction using Bacillus licheniformis. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 4272–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilchap, F.; Mousavi, S.M. Influence of culture media on bacterial organic acids production for sustainable indirect bioleaching of spent printed circuit boards. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glucose-Ethanol (GE) Medium | Brain Heart Infusion Medium (BHI) | Nutrient Broth + Lactose (NBL) | deMan, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose—20 g/L | Glucose—20 g/L | Lactose—10 g/L | Glucose—20 g/L |

| Yeast Extract—11 g/L | Calf brain infusion—12 g/L | Yeast Extract—2 g/L | Lab-lemco Powder—8 g/L |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate—1.1 g/L | Beef heart infusion—5 g/L | Nutrient Broth—8 g/L | Yeast Extract—4 g/L |

| Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate—3.3 g/L | Sodium Chloride—5 g/L | Sodium Chloride—5 g/L | Peptone—10 g/L |

| Ethanol—20 g/L | Disodium hydrogen phosphate—2.5 g/L | Sorbitan mono-oleate—1 ml/L | |

| Di-potassium hydrogen phosphate 2 g/L | |||

| Sodium acetate—5 g/L | |||

| Tri-ammonium citrate—2 g/L | |||

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate—0.2 g/L | |||

| Magnesium sulfate tetrahydrate—0.05 g/L |

| Al | Ba | Ca | Co | Cr | Cu | Fe | Ga | Li | |

| mg/kg | 87,500 ± 1460.03 | 40 ± 1.04 | 43,500 ± 914.65 | 164 ± 5.19 | 180 ± 6.18 | 87 ± 2.15 | 184,000 ± 1907.98 | 33 ± 1.01 | 19 ± 0.33 |

| Mg | Mn | Mo | Ni | Sc | Sr | Ti | V | Zn | |

| mg/kg | 26,600 ± 781.09 | 1742 ± 20.79 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 264 ± 12.57 | 26 ± 1.1 | 139 ± 6.62 | 48,600 ± 3091.88 | 1182 ± 67.32 | 347 ± 10.45 |

| Mineral Oxides | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O (%) | MgO (%) | K2O (%) | CaO (%) | Al2O3 (%) | SiO2 (%) | P2O5 (%) | SO3 (%) | TiO2 (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | MnO (%) |

| 1.22 | 4.43 | 0.14 | 6.91 | 17.65 | 29.63 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 8.55 | 28.23 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brar, K.K.; Preez, A.D.; Perreault, N.N. Assessing the Potential of Heterotrophic Bioleaching to Extract Metals from Mafic Tailings. Metals 2026, 16, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020178

Brar KK, Preez AD, Perreault NN. Assessing the Potential of Heterotrophic Bioleaching to Extract Metals from Mafic Tailings. Metals. 2026; 16(2):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020178

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrar, Kamalpreet Kaur, Avi Du Preez, and Nancy N. Perreault. 2026. "Assessing the Potential of Heterotrophic Bioleaching to Extract Metals from Mafic Tailings" Metals 16, no. 2: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020178

APA StyleBrar, K. K., Preez, A. D., & Perreault, N. N. (2026). Assessing the Potential of Heterotrophic Bioleaching to Extract Metals from Mafic Tailings. Metals, 16(2), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020178