The Effect of NbC Precipitates on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Dual-Phase Steels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Procedure

2.1. Experimental Materials

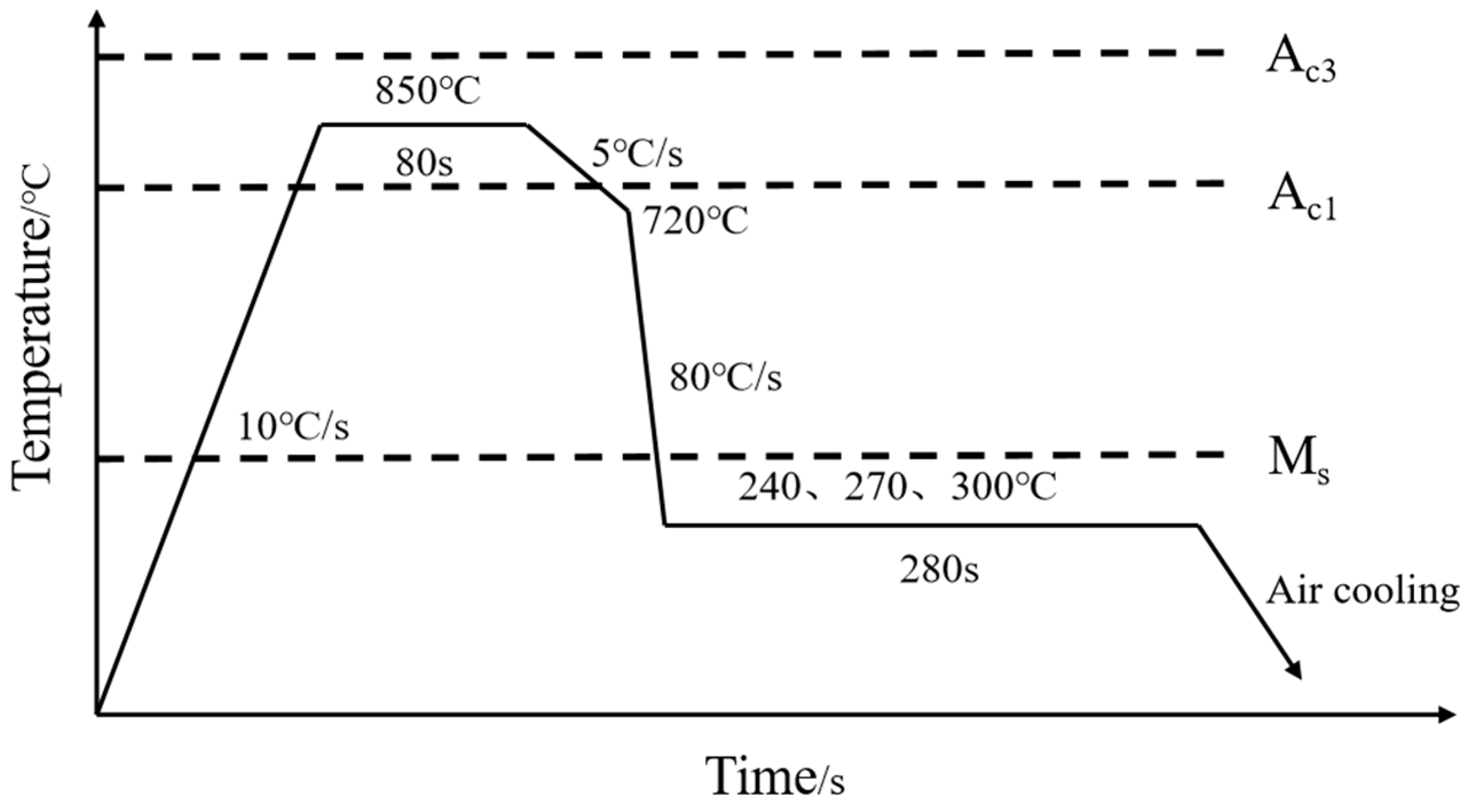

2.2. Heat Treatment Process

2.3. Material Characterizations

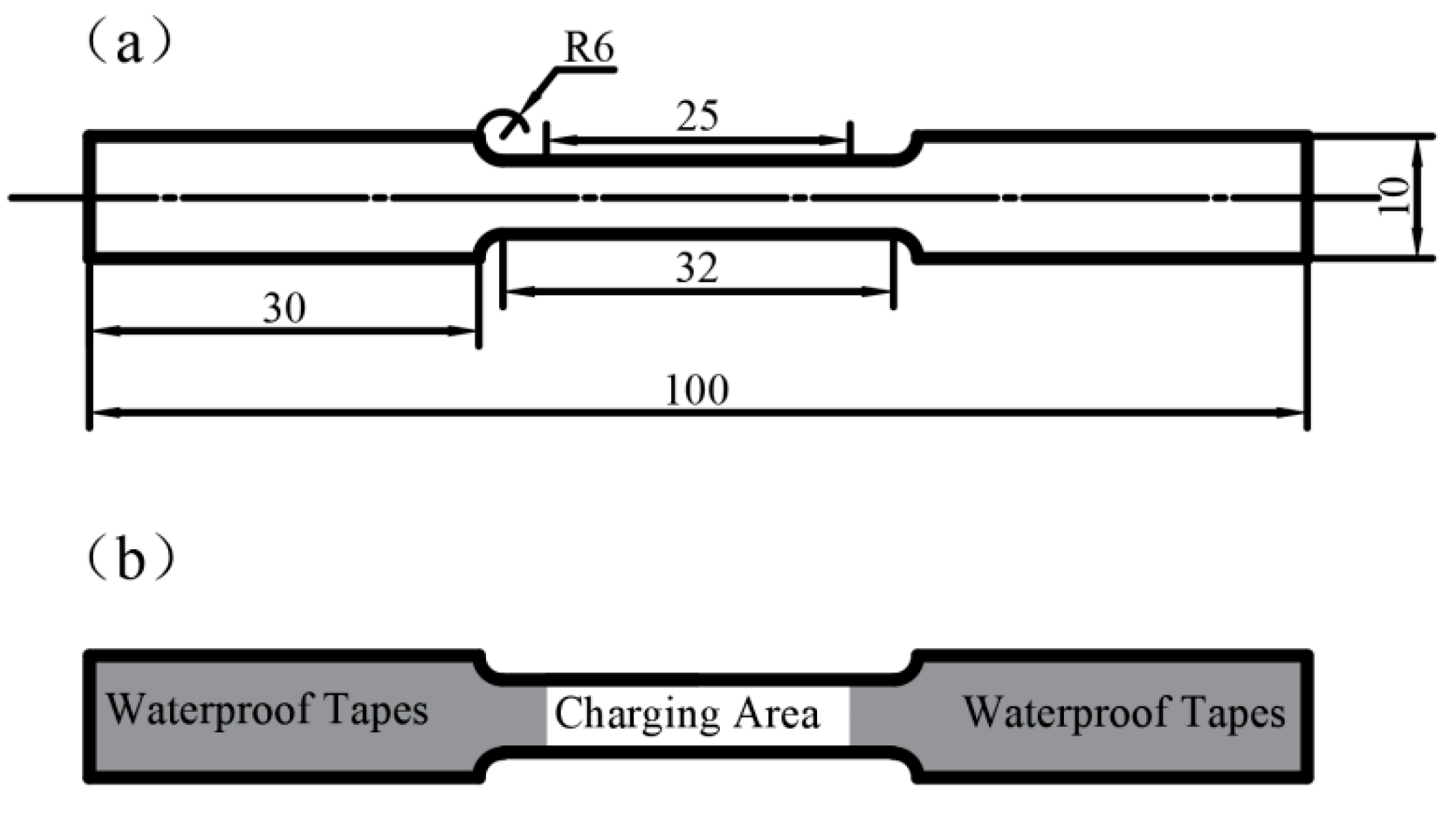

2.4. Mechanical Testing

2.5. Hydrogen Trap Characterizations

3. Results

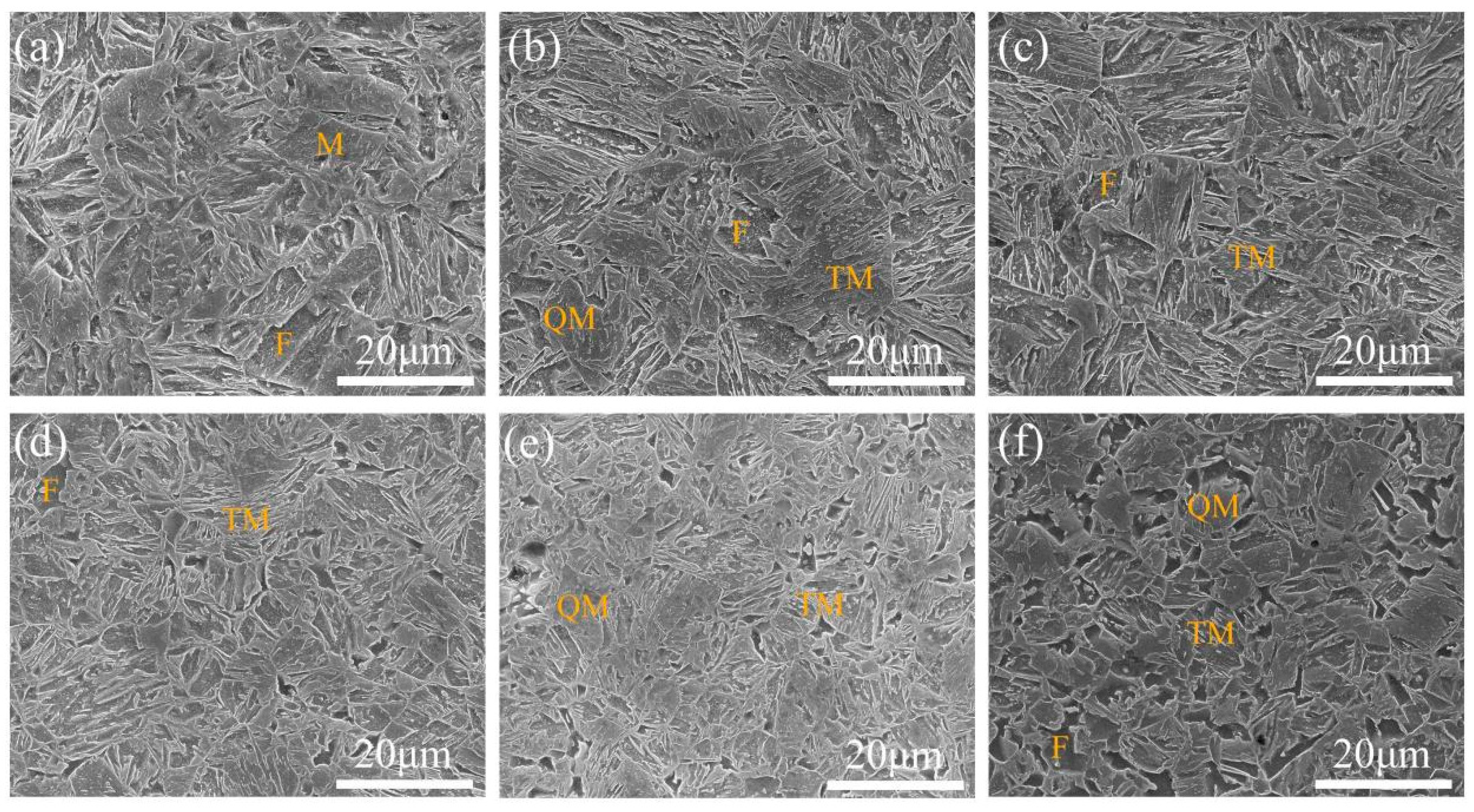

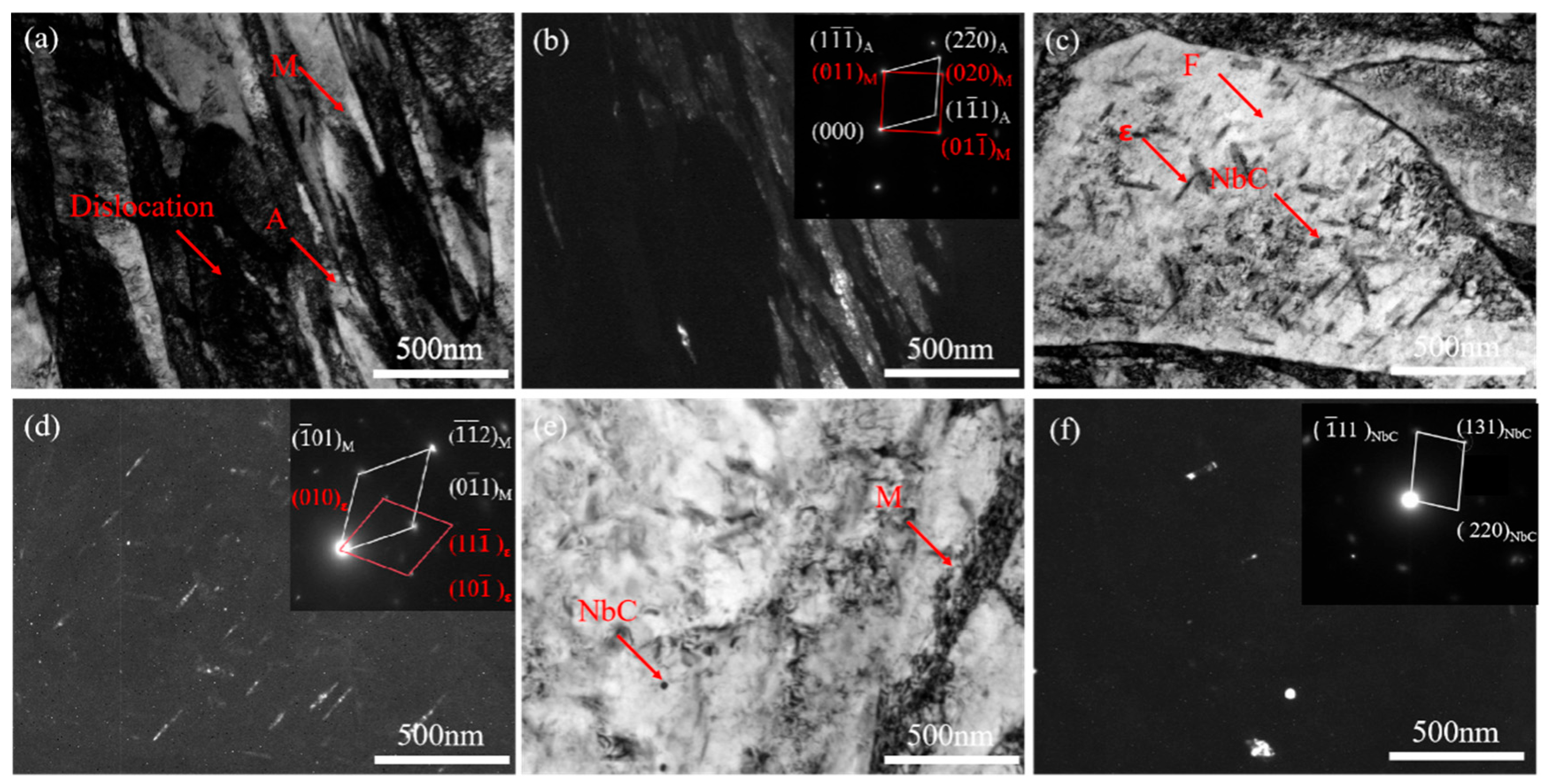

3.1. Microstructural Observations

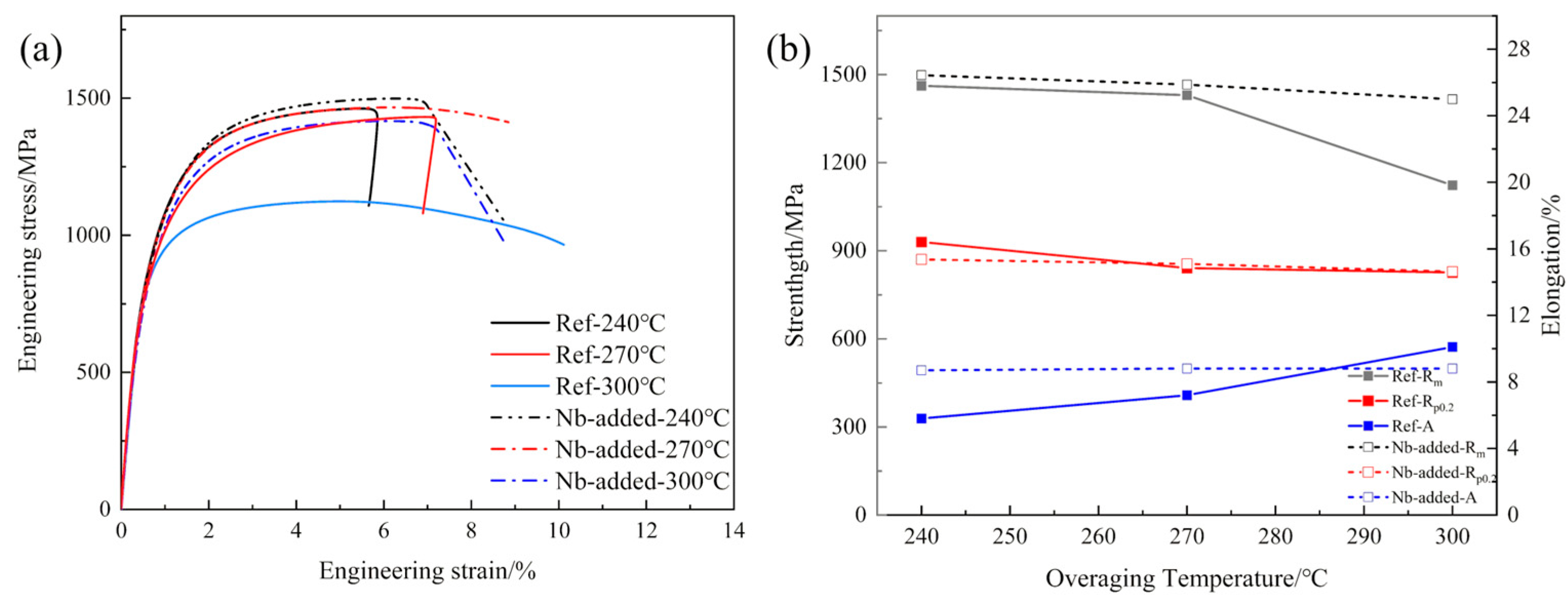

3.2. Mechanical Properties

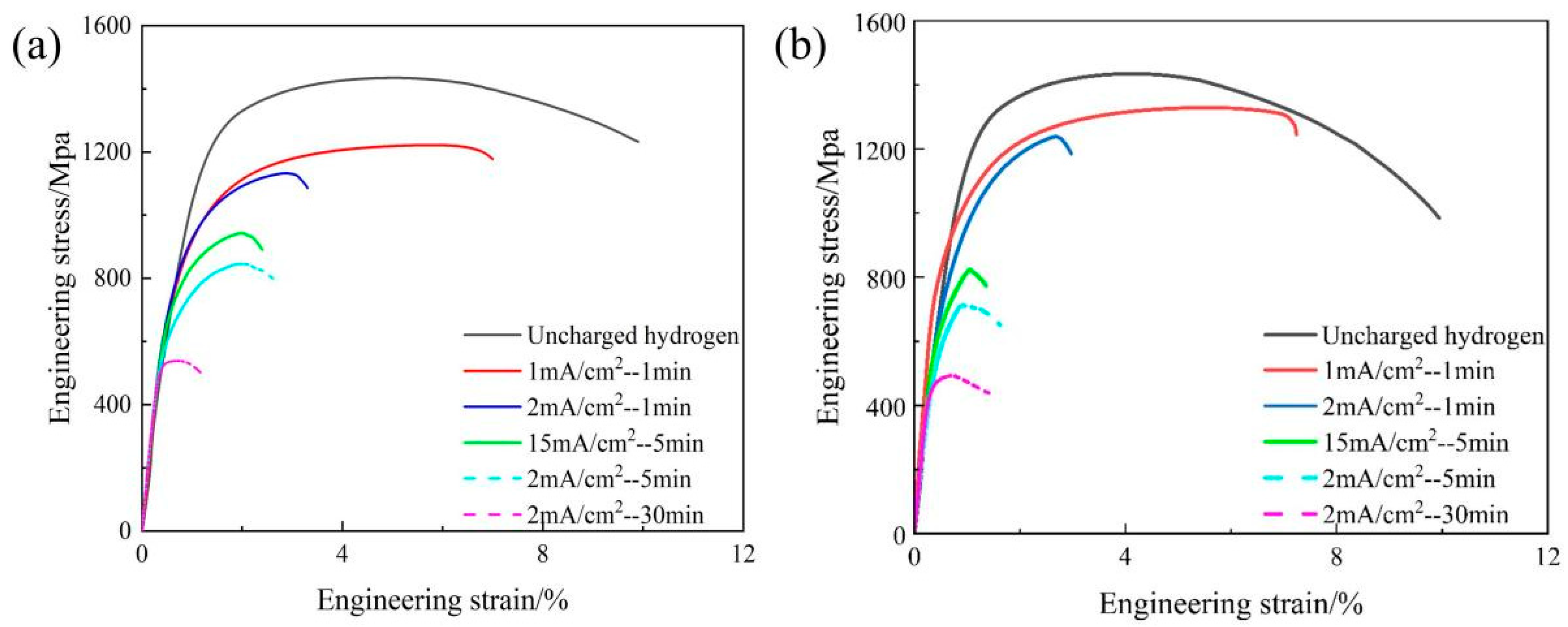

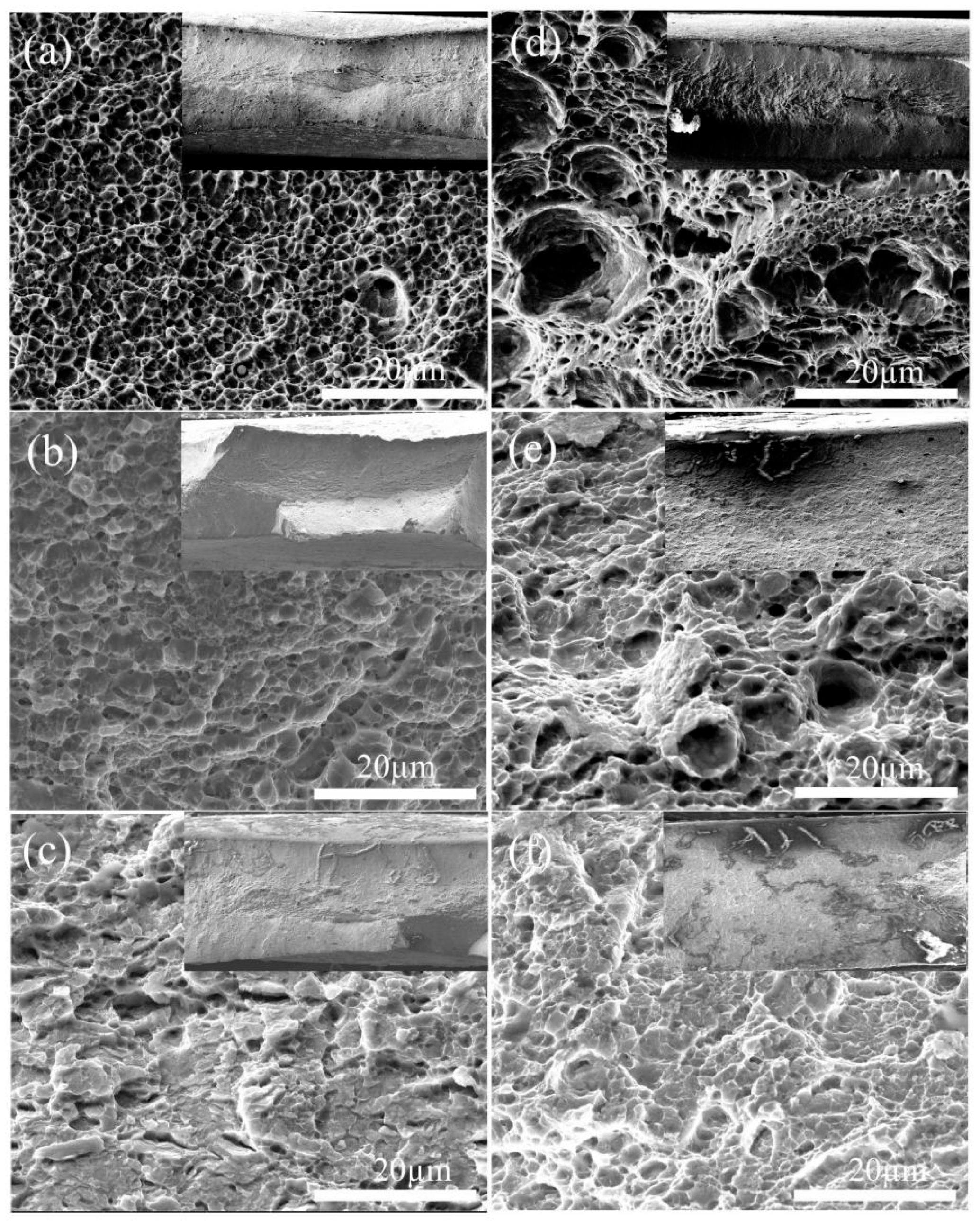

3.3. Hydrogen Embrittlement Sensitivity

4. Discussion

4.1. Synergistic Strengthening and the Role of Over-Aging Temperature

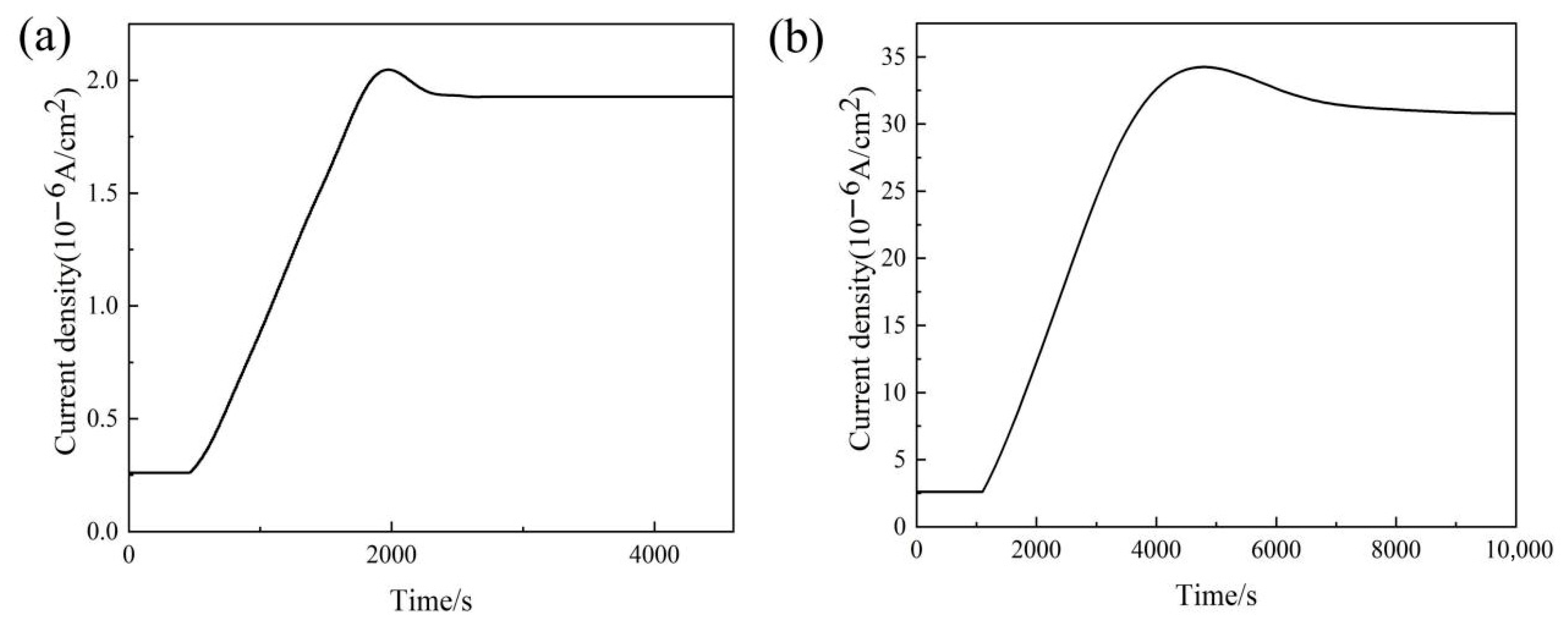

4.2. Decoupling the Dual Role of Nb in Hydrogen Embrittlement: The Triumph of Beneficial Trapping

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Increasing the over-aging temperature promotes martensite decomposition and carbide precipitation, resulting in blurred martensite morphology, an increased fraction of quenched martensite, and the stabilization of retained austenite. The addition of Nb significantly refines the microstructure, including prior austenite grains, martensite laths, and ferrite, thereby enhancing microstructural homogeneity.

- (2)

- The evolution of mechanical properties reveals a synergistic effect between the over-aging temperature and Nb microalloying. Although the strength of both steels decreases due to martensite softening during over-aging, the Nb-added steel exhibits a superior strength–ductility balance under all processing conditions. This is attributed to the pronounced effects of fine-grained strengthening and precipitation strengthening, which effectively compensate for the strength loss.

- (3)

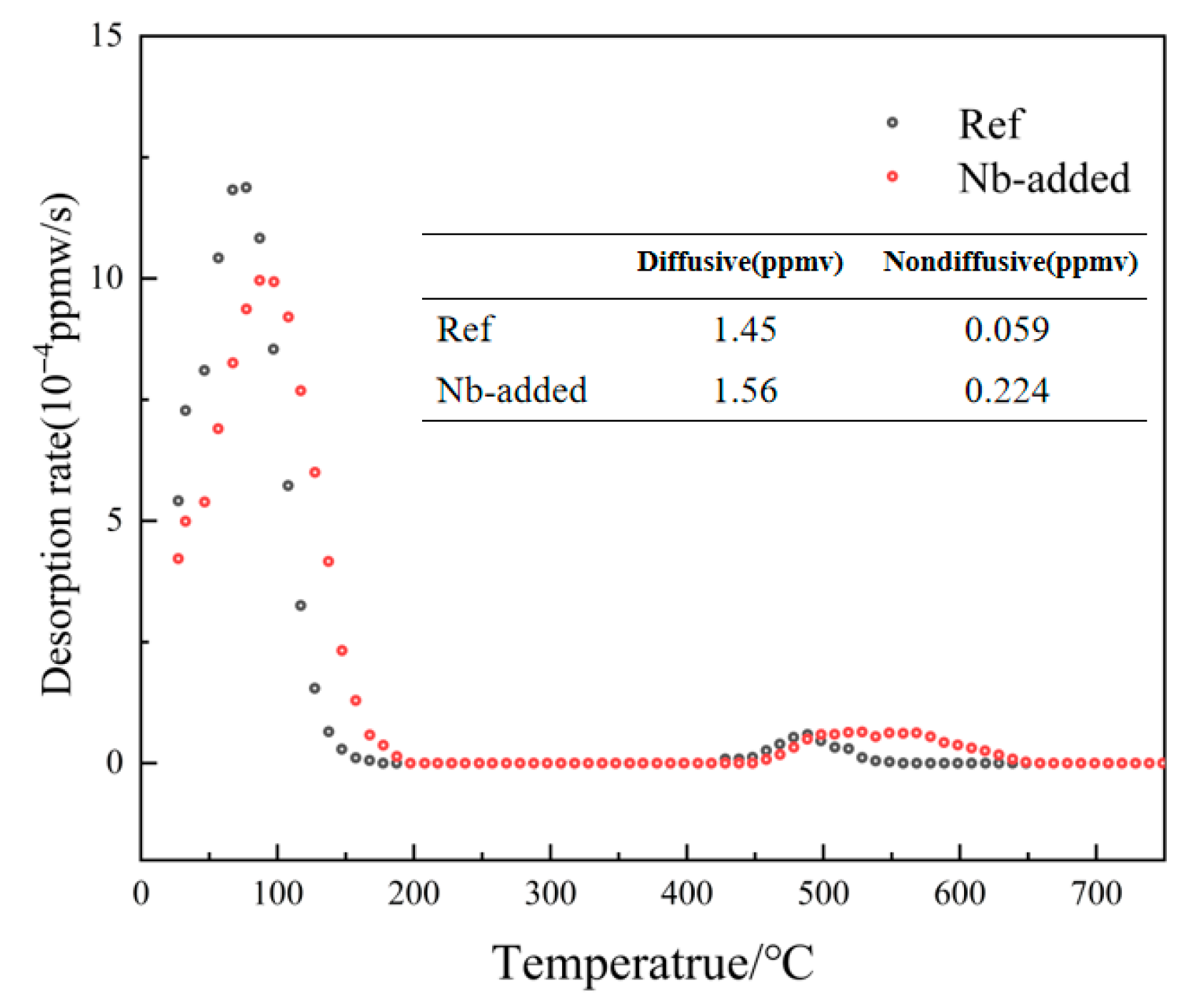

- The superior HE resistance of Nb-added steel is attributed to the irreversible hydrogen trapping capability of nano-sized NbC precipitates. While these precipitates increase the total hydrogen content, they effectively reduce mobile hydrogen diffusivity and prevent detrimental hydrogen accumulation at critical microstructural interfaces, thereby mitigating hydrogen-induced degradation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khosravani, A.; Cecen, A.; Kalidindi, S.R. Development of high throughput assays for establishing process-structure-property linkages in multiphase polycrystalline metals: Application to dual-phase steels. Acta Mater. 2017, 123, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Baig, M.; Choi, S.H.; Yang, H.S.; Sun, X. Quasi-static and dynamic responses of advanced high strength steels: Experiments and modeling. Int. J. Plast. 2012, 30–31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Lai, Q.Q.; Chai, Z.S.; Wei, X.L.; Xiong, X.C.; Yi, H.L.; Huang, M.X.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.F. Revolutionizing car body manufacturing using a unified steel metallurgy concept. Sci. Adv. 2022, 7, eabk0176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagnotto, M.; Ponge, D.; Demir, E.; Raabe, D. Orientation gradients and geometrically necessary dislocations in ultrafine grained dual-phase steels studied by 2D and 3D EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 2738–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierman, A.P.; Bouaziz, O.; Pardoen, T.; Jacques, P.J.; Brassart, L. The influence of microstructure and composition on the plastic behaviour of dual-phase steels. Acta Mater. 2014, 73, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Bouaziz, O.; Gouné, M.; Brassart, L.; Verdier, M.; Parry, G.; Perlade, A.; Brechet, Y.; Pardoen, T. Damage and fracture of dual-phase steels: Influence of martensite volume fraction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 646, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva, I.; Allain, S.; Scott, C.; Redjaïmia, A.; Moulin, A. Relationship between microstructure, mechanical properties and damage mechanisms in high martensite fraction dual phase steels. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhor, A.; Taheri, A.K.; Mirzadeh, H.; Uthaisangsuk, V. Processing, microstructure adjustments, and mechanical properties of dual phase steels: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 561–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atreya, V.; Bos, C.; Santofimia, M.J. Understanding ferrite deformation caused by austenite to martensite transformation in dual phase steels. Scr. Mater. 2021, 202, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.; Palkowski, H. Tensile properties and bake hardening response of dual phase steels with varied martensite volume fraction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 777, 139044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnotto, M.; Adachi, Y.; Ponge, D.; Raabe, D. Deformation and fracture mechanisms in fine-and ultrafine-grained ferrite/martensite dual-phase steels and the effect of aging. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, T.; Teodosiu, C.; Maeda, D.; Uenishi, A. Mesoscale simulation of the early evolution of ductile fracture in dual-phase steels. Int. J. Plast. 2015, 74, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, J.; Matlock, D.K.; Cooman, B.C.; Schroth, J.G. Carbon partitioning into austenite after martensite transformation. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 3324–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, D.; Robinson, M.J. The effects of sacrificial coatings on hydrogen embrittlement and re-embrittlement of ultra high strength steels. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, J.Y.; Qiao, L.J.; Volinsky, A.A. Microstructure effect on hydrogen-induced cracking in TM210 maraging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 586, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, M.J.; Hojo, T. Hydrogen susceptibility of nanostructured bainitic steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, S.P.; Yang, J.R. Microstructure characterization and strengthening behavior of dual precipitation particles in Cu-Ti microalloyed dual-phase steels. Mater. Des. 2019, 166, 107613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samei, J.; Zhou, L.F.; Kang, J.D.; Wilkinson, D.S. Microstructural analysis of ductility and fracture in fine-grained and ultrafine-grained vanadium-added DP1300 steels. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 117, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelligra, C.; Samei, J.; Kang, J.; Wilkinson, D.S. The effect of vanadium on microstrain partitioning and localized damage during deformation of unnotched and notched DP1300 steels. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 158, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatani, R.A.; DeArdo, A.J. Rational Alloy Design of Niobium-Bearing HSLA Steels. Metals 2020, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H.; Yang, J.R.; Chen, Y.W.; Rehrl, J.; Hebesberger, T. Metallurgical Effects of Niobium in Dual Phase Steel. Metals 2020, 10, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruysse, F.; Claeys, L.; Depover, T.; Verleysen, P.; Petrov, R.H.; Verbeken, K. The effect of Nb on the hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of Q&P steel under static and dynamic loading. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 852, 143652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Yang, X.S.; Qiao, L.J.; Pang, X.L. Atomic-scale investigation of deep hydrogen trapping in NbC/α-Fe semi-coherent interfaces. Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lu, H.Z.; Liang, J.T.; Rosenthal, A.; Liu, H.W.; Sneddon, G.; McCarroll, I.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Li, W.; Guo, A.M.; et al. Observation of hydrogen trapping at dislocation, grain boundaries, and precipitates. Science 2020, 367, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.D.; Li, C.Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, K. Effect of microstructure on hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility in quenching-partitioning-tempering steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Hui, W.J.; Fang, B.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Zhao, S.X. Hydrogen embrittlement of a V+Nb-microalloyed high-strength bolt steel subjected to different austenitizing temperatures. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 169, 109178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Turk, A.; Nutter, J.; Yu, F.; Wynne, B.; Ricera-Diaz-del-Castillo, P.; Rainforth, W.M. Hydrogen embrittlement mechanism in advanced high-strength steels. Acta Mater. 2022, 223, 117881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-22; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ISO 17081:2004(E); Method of Measurement of Hydrogen Permeation and Determination of Hydrogen Uptake and Transport in Metals by An Electro-Chemical Technique. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Redhead, P.A. Thermal desorption of gases. Vacuum 1962, 12, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.J.; Baker, T.N. The effects of small titianium additions on the mechanical properties and the microstructures of controlled rolled niobium-bearing HLSA plate steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1993, 169, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, B.; Hoche, H.; Oechsner, M. Hydrogen-assisted cracking (HAC) of high-strength steels as a function of the hydrogen pre-charging time. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 261, 108246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, J.F.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Huang, Y.H.; Li, X.G. Dual role of nanosized NbC precipitates in hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of lath martensitic steel. Corros. Sci. 2020, 164, 108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chakraborty, P.; Ponge, D.; Hickel, T.; Sun, B.; Wu, C.H.; Gault, B.; Raabe, D. Hydrogen trapping and embrittlement in high-strength Al alloy. Nuture 2022, 602, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerscheidt, T.A.; Dey, P.; Bogdanovski, D.; Appen, J.V.; Hickel, T.; Neugebauer, J.; Dronskowski, R. The Role of κ-Carbides as Hydrogen Traps in High-Mn Steels. Metals 2017, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Xu, W.Z.; Guo, Z.H.; Wang, L.; Rong, H.Y. Carbide characterization in a Nb-microalloyed advanced ultrahigh strength steel after quenching–partitioning–tempering process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 3373–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, B.; Remy, B.; Scott, C.; Deschampa, A.; Chene, J.; Dieudonne, T. Hydrogen trapping by VC precipitates and structural defects in a high strength Fe-Mn-C steel studied by small-angle neutron scattering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 536, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Vercruysse, F.; Petrov, R.; Verleysen, P. The effect of Niobium on austenite evolution during hot rolling of advanced high strength steel. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1270, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steel | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Al | Nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference steel | 0.22 | 0.53 | 2.44 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0 |

| Nb steel | 0.22 | 0.59 | 2.42 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.032 |

| Reference Steel | Nb-Added Steel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 240 °C | 270 °C | 300 °C | 240 °C | 270 °C | 300 °C | |

| original austenite grain size/μm | 2.61 | 3.05 | 3.22 | 2.14 | 2.33 | 2.64 |

| Reference Steel | Nb-Added Steel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 240 °C | 270 °C | 300 °C | 240 °C | 270 °C | 300 °C | |

| Rm/MPa | 1462.8 ± 5.2 | 1430.5 ± 6.8 | 1123.5 ± 8.1 | 1498.1 ± 4.1 | 1466.4 ± 5.5 | 1416.8 ± 7.2 |

| Rp0.2/MPa | 909.7 ± 4.8 | 841.5 ± 5.2 | 826.5 ± 6.5 | 870.6 ± 3.9 | 855.7 ± 4.7 | 829.4 ± 5.8 |

| A/% | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.5 |

| Hydrogen Charging Current Density (mA/cm2) | Hydrogen Charging Time (min) | Rm (MPa) | Rp0.2 (MPa) | A (%) | Elloss (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference steel | 0 | 0 | 1434.93 | 1043.6 | 12.06 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1215.87 | 794.6 | 7.79 | 35.4 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1132.95 | 645.8 | 5.22 | 54.2 | |

| 15 | 1 | 942.45 | 650.5 | 3.22 | 73.3 | |

| 2 | 5 | 845.72 | 508.8 | 2.87 | 76.2 | |

| 2 | 30 | 538.60 | 480.2 | 1.63 | 86.5 | |

| Nb-added steel | 0 | 0 | 1513.57 | 1080.9 | 12.95 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1327.85 | 857.8 | 8.94 | 30.9 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1237.38 | 786.5 | 2.97 | 77.1 | |

| 15 | 1 | 820.22 | 790.5 | 3.94 | 69.5 | |

| 2 | 5 | 711.03 | 580.5 | 3.18 | 75.4 | |

| 2 | 30 | 493.75 | 482.5 | 2.29 | 82.3 |

| Hydrogen Permeation Experiments | DP0Nb Steel | DP3Nb Steel |

|---|---|---|

| L (cm) | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| I∞ (A/cm2) | 1.93 × 10−6 | 3.77 × 10−5 |

| tL (s) | 1330 | 1669 |

| J∞L (mol cm−1s−1) | 1.24 × 10−12 | 2.48 × 10−11 |

| Deff (cm2 s−1) | 2.87 × 10−7 | 2.49 × 10−7 |

| Capp (mol cm−3) | 4.32 × 10−6 | 9.95 × 10−5 |

| NT (cm−3) | 3.86 × 1020 | 9.84 × 1021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Qiang, K.; Cao, B.; Tang, Y.; Ma, F.; Li, W.; Zhang, K. The Effect of NbC Precipitates on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Dual-Phase Steels. Metals 2025, 15, 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121342

Li W, Qiang K, Cao B, Tang Y, Ma F, Li W, Zhang K. The Effect of NbC Precipitates on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Dual-Phase Steels. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121342

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wei, Kejia Qiang, Boyu Cao, Yu Tang, Fengcang Ma, Wei Li, and Ke Zhang. 2025. "The Effect of NbC Precipitates on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Dual-Phase Steels" Metals 15, no. 12: 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121342

APA StyleLi, W., Qiang, K., Cao, B., Tang, Y., Ma, F., Li, W., & Zhang, K. (2025). The Effect of NbC Precipitates on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Dual-Phase Steels. Metals, 15(12), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121342