Abstract

Lithium batteries have emerged as the mainstream technology in the current energy storage field due to their advantages, such as high energy density and long cycle life. However, from a multi-physics coupling perspective, research remains relatively scarce regarding the analysis of dendrite nucleation and growth, as well as their influence on lithium dendrite growth. Based on the phase field theory, this study develops a mechanical-thermal-electrochemical coupling model to systematically investigate the evolution mechanisms and suppression strategies of lithium dendrites induced by relevant physical quantities through the coupled effects of mechanical, thermal, and electrochemical fields. The dynamic behavior of the solid-solid interface is characterized by introducing order parameters. The governing nonlinear partial differential equations are formulated by combining the Cahn-Hilliard and Ginzburg-Landau equations. The present numerical results and the previous results are compared to validate the present model in properly predicting lithium dendrite growth. Numerical simulations are performed to analyze the influence of various physical parameters, such as electric potential, anisotropic intensity and anisotropic modulus, on the morphological evolution of lithium dendrites. These findings provide critical insights for advancing strategies to suppress lithium dendrite growth and enhance battery performance in solid-state lithium batteries under multi-field coupling conditions.

1. Introduction

Solid-state lithium batteries (SSLBs) are regarded as an ideal solution to break through the performance and safety bottlenecks of traditional lithium batteries due to their non-flammable solid electrolytes, wider electrochemical stability window, and greater potential for high energy density [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The solid electrolyte of SSLBs performs dual roles of lithium-ion conduction and electron insulation [8]. For the positive electrode, metallic lithium is regarded as an ideal choice for SSLBs owing to its high theoretical capacity, but its adverse side reactions with electrolytes severely impair battery performance [9,10]. The development of solid electrolytes still confronts two core challenges. Firstly, the contact area between the electrode and solid electrolyte is far smaller than that between the electrode and liquid electrolyte, leading to a significant reduction in interfacial ion conduction efficiency at the interface. Secondly, lithium dendrite formation is driven by metallic lithium deposition. Although solid electrolytes have better mechanical properties than liquid electrolytes, lithium dendrites seriously affect the safety and cycle life of SSLBs [11,12].

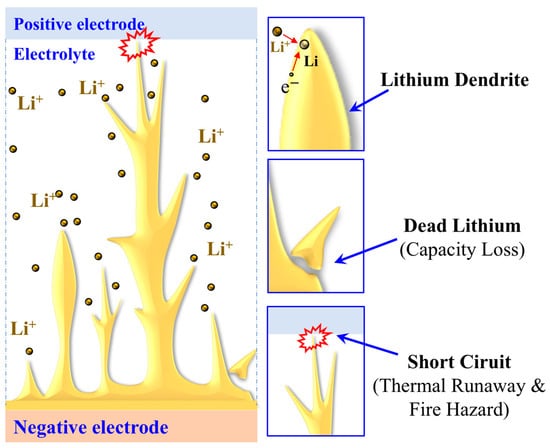

During charge-discharge cycling, uneven deposition of lithium-ions on the surface of the metallic lithium electrode is the root cause of lithium dendrite initiation. When micro-protrusions or defects exist on the electrode surface, the local electric field and lithium-ion flux distort, creating conditions for instability. According to the space charge model [13], the depletion of anions near the anode surface generates a steep electric field gradient. This drives the lithium-ion to recombine with electrons, forming nascent dendrites that continue to nucleate and grow. Meanwhile, if lithium-ion migration in the electrolyte lags behind the plating reaction rate, the local lithium-ion concentration approaches zero, thereby accelerating dendrite formation. The uncontrolled dendrite formation gives rise to multiple adverse consequences, including reducing the Coulombic efficiency, stripping the interface between the solid electrolyte and the electrode, and forming “dead lithium”. More critically, uncontrolled dendrite growth can puncture the solid electrolyte, which causes an internal short circuit and even triggers thermal runaway [14,15], as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the “dead lithium” and internal short circuit of SSLBs caused by uncontrolled dendrite growth.

Many scholars have conducted extensive research on the causes of lithium dendrite formation and their growth and evolution mechanisms, focusing on three key issues: initial nucleation models, nucleation locations, and morphologies. In terms of initial nucleation models, the main models can be divided into heterogeneous models, surface diffusion models, space charge models, and crystallographic models. All of these models revolve around the lithium-ion deposition and aggregation forming lithium nuclei induced by local electric field inhomogeneity [15]. Regarding nucleation locations, existing studies have proposed three viewpoints: tip nucleation, bottom nucleation, and multi-point nucleation. Tip nucleation stems from the enhanced electric potential and concentration gradient at the tip, and the tip curvature significantly promotes the growth rate of dendrites. Bottom nucleation is induced by uneven defects at the bottom of the electrode, which can be confirmed through in situ scanning electron microscopy observations [16]. Multi-point nucleation is manifested in the multi-directional growth of dendrites, which not only extend longitudinally but also generate new branches at bends. In terms of morphology, lithium dendrites exhibit three main forms: moss-like [17], needle-like [18], and tree-like [19], affected by factors such as electrode materials, current density, and electrolyte composition. When the current density is low (approximately 0.22 mA/cm2), the dendrite morphology is moss-like; when the current density is high (approximately 0.5 mA/cm2), it transforms into a needle-like shape. The influence of current density on dendrites can be seen. Research methods for lithium dendrites are mainly divided into two categories: experimental observation methods and multi-physics field modeling methods. However, the study of lithium dendrites can only be carried out at the macro level, and it is difficult to go deep into the micro scale to capture the reaction process due to the limitations of experimental equipment. In addition, the experimental method also has the problems of high time cost and high sensitivity to environmental conditions, which has led some researchers to investigate lithium dendrites using multi-physics field modeling methods. Multi-physics field modeling methods provide theoretical support for the growth mechanism of lithium dendrites. Barton and Bockris [20] conducted the first quantitative analysis of metal dendrite growth, pointing out that the maximum growth rate of dendrites is related to overpotential. However, this method cannot be used to predict incubation time and cannot explain the physics in this period. Chazalviel [21] proposes that dendrite growth only occurs when the current density exceeds the limiting current. Furthermore, Monroe and Newman [22] further considered the tip curvature of dendrites, confirming that the growth rate of dendrites is related to current density, tip curvature, and lithium-ion concentration in the electrolyte. In addition, combining lithium-ion diffusion rate, concentration, and overpotential, Akolkar [23] further verifies the conclusions of the model proposed by Monroe and Newman [22].

The phase field method has risen to prominence as a preeminent research frontier in contemporary lithium dendrite studies, owing to its singular strength in providing a universal mathematical framework that seamlessly captures the full complexity of interfacial evolution dynamics. Based on thermodynamics, this method treats the transition region between different phases as a diffuse interface with a certain thickness, breaking through the limitations of traditional sharp interface models. It can naturally characterize the interface position and morphology through the spatial distribution of field variables (such as order parameters, concentration, and temperature). The advantages of the phase field method lie in that it cannot only reproduce typical phenomena observed in experiments, such as dendrite tip splitting and trunk growth, but also explore the regulatory laws of external conditions (such as electrolyte composition and current density) on dendrite growth through parametric analysis. Guyer et al. [24] proposed a one-dimensional linear phase field model to study equilibrium states and electrochemical reaction kinetics. Furthermore, a one-dimensional nonlinear phase field model was established by Liang et al. [25], making the variation of variables more consistent with the actual lithium dendrite growth process. The above phase field models were rooted in one-dimensional electrochemical reaction kinetics. A dendrite growth model for liquid electrolytes based on phase field theory was constructed by Chen et al. [26] to analyze the influence of electrochemical reactions on dendrite morphology. By simplifying the nucleation as a deterministic process, dendrite growth was simulated by Di et al. [27] using the phase field method. In addition, the new calculation method proposed by Aryanfar et al. [28] can reveal the growth mechanism of lithium dendrites in inhomogeneous electric fields. Yan et al. [29] coupled the phase field model with a heat transfer model and found that temperature gradients can change the morphology of lithium dendrites by affecting the distribution of lithium-ion concentration. However, previous studies mainly focused on the effects of a single physical field or the coupling of two physical fields. In addition, there have been relatively few studies analyzing the effect of electric potential, anisotropic intensity, and anisotropic modulus on lithium dendrite growth and suppression strategies from the perspective of mechanical-thermo-electrochemical coupling.

Therefore, based on the phase field theory, this study develops a multi-physics coupling model to systematically investigate the evolution mechanisms and suppression strategies of lithium dendrites induced by relevant physical quantities through the coupled effects of mechanical, thermal, and electrochemical fields. The dynamic behavior of the solid-solid interface is characterized by introducing order parameters. The governing nonlinear partial differential equations are formulated by combining the Cahn-Hilliard and Ginzburg-Landau equations. Numerical simulations are performed to analyze the influence of electric potential, anisotropic intensity, and anisotropic modulus on the morphological evolution of lithium dendrites. A Gaussian-distributed noise term is used to simulate real-world fluctuations in lithium-ion deposition. The synergistic effects (e.g., temperature-dependent modulated by anisotropic modulus, stress concentration amplified by thermal gradients) for lithium dendrite suppression strategies are revealed. The analysis of their effects on lithium dendrite growth provides new insights into understanding the mechanism of lithium dendrite growth and suppression.

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Basis of the Phase Field Model

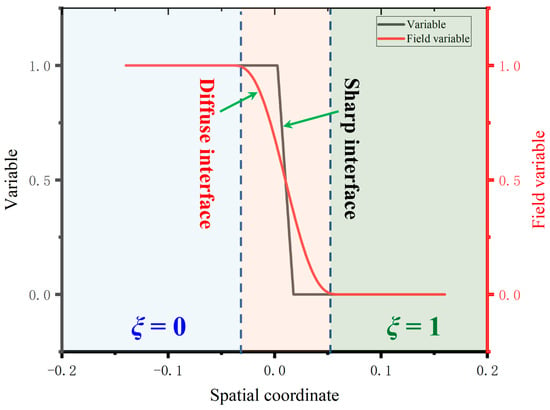

The phase transition process model originated from the Stefan model or the sharp interface model. This model assumed that the thickness of the two-phase interface was 0, which would lead to the need to constantly solve the normal velocity at the interface to track the interface movement, making the calculation and solution extremely difficult. The establishment of the phase field method proposed a dispersion interface model and established continuous field variables, namely order parameters, to distinguish each phase. Taking the value of the order parameter as 1 to represent the solid phase and the value of the order parameter as 0 to represent the liquid phase, while for the interface region, it is a continuous change from 0 to 1 [30]. Thus, a continuous function is used to describe the interface change, and the interface region with a dispersed distribution can be formed in this way, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the sharp model and the diffuse model.

The multi-field coupling modeling approach based on phase field theory, combined with the lithium dendrite growth model for liquid electrolytes developed by Chen et al. [26], incorporates elastic strain energy into the model. This modification transforms the nonlinear phase field model of liquid electrolytes into a nonlinear phase field model for solid electrolytes and adjusts the parameters of the solid electrolyte. The Helmholtz free energy functional is established as follows:

where F(ξ, ci, φ, u) is the Helmholtz free energy density per unit volume, ξ is the order parameter, ci is the concentration of the substance, φ is the electrostatic potential, and u represents the displacement field.

The local chemical free energy density Fch(ξ, ci) can be expressed as:

where g(ξ) is a double-well function, and the common form taken is g(ξ) = Wξ2(1 − ξ)2, W represents the barrier height. R is the molar gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and is the normalized Li+ ion concentration and anion concentration, respectively. μi represents the chemical potential of each component.

The gradient free energy density fgrad(ξ) can be expressed as:

where kξ is represented as the gradient energy coefficient. To handle the anisotropic interface energy, the gradient term may need a more complex form to solve the problem that the anisotropic surface energy in crystal growth will cause the interface energy to change with direction. At this point, the gradient energy coefficient is replaced by a function of anisotropy and can be expressed as kξ = k0[1 + δcos(ωθ − θ0)], k0 is the gradient energy coefficient, δ is the anisotropic intensity, ω is the anisotropic modulus, and θ is the Angle between the interface normal vector and the reference axis.

The electrochemical free energy density felch(ξ, ci, φ) can be expressed as:

where n represents the ion charge number, which is 1 for lithium-ion. F is Faraday’s constant, F = 96,485 C·mol−1.

Assuming that under the elastic condition of small deformation lines, by the generalized Hooke’s law, the energy density of elastic strain fels(ξ, u) can be expressed as:

where represents the second-order elastic strain tensor, which is the influence of strain in the direction i on the direction j, and Cijkl is the local elastic tensor.

The second-order elastic strain tensor is . is the total strain. represents the local eigenstrain, which is caused by the growth of dendrites. λi represents the Vegard strain coefficient, which is obtained from the density functional theory.

For composite material electrolytes, the local elastic tensor can be expressed as:

Based on the mixing rules of composite materials, the effective elastic modulus and effective Poisson’s ratio can be obtained by using interpolation functions, and their expressions are as follows:

where and represent the elastic modulus of lithium metal and electrolyte respectively, and represent the Poisson’s ratios of lithium metal and electrolyte respectively. The interpolation function is h(ξ) = ξ3(6ξ2 − 15ξ + 10). δij is Kronecker delta function, which equals 1 when i = j and 0 otherwise.

The noise term fns(ci) is as follows:

where h’(ξ) is the first derivative of h(ξ), which determines the distribution intensity of noise near the phase interface. γ = 1 represents the magnitude of the noise amplitude, χ represents the random number sequence, making it follow a Gaussian distribution or a uniform distribution, thereby introducing random disturbances. The noise term is introduced to simulate the crucial role that actual fluctuations play in the nucleation and growth of dendrites in real-world situations.

To accurately describe the charge transfer on the electrode surface. Using the Butler-Volmer equation and Ginzburg-Landau equation, the nonlinear phase field control equation is obtained as follows:

where L0 is the interface mobility.

In addition, during the lithium deposition process, the mass conservation of lithium-ion must be guaranteed during the diffusion process. According to the law of conservation of mass, it can be obtained that:

where represents the normalized lithium-ion concentration and represents the molar flux. The molar flux of lithium-ion is determined by the corresponding mobility and electrochemical potential gradient, and its expression is as follows:

Meanwhile, in order to consider the material consumption on the surface, according to the Nernst-Einstein relation, the following concentration conservation equation is:

where Deff = DLi·h(ξ) + De [1 − h(ξ)] is the effective diffusion coefficient. Among them, DLi and De are the diffusion coefficients of the electrode and electrolyte, respectively. K is a ratio constant.

For the time evolution of the electrostatic potential, assume that the system is electrically neutral. Under this condition, the evolution of the electrostatic potential can be constructed through the Nernst-Planck current conservation Equation (12), and the potential distribution equation is as follows:

where σeff = σLi·h(ξ) + σe [1 − h(ξ)] is the effective electrical conductivity, σLi and σe are the conductivity of the electrode and electrolyte, respectively.

Due to the unique physical properties of solid electrolytes, a mechanical equilibrium equation is introduced to describe the interaction between dendrite growth and the mechanical deformation of the electrolyte, as follows:

2.2. Mechanical-Thermo Coupling Model

2.2.1. Thermal Coupling Method

A heat transfer model is established in the phase field equation of lithium dendrites, which is based on the law of conservation of energy and Fourier’s law of heat conduction. Then the temperature control equation is as follows:

where Cp is the specific heat capacity per unit volume, ρ is the mass density, and κ = κe·h(ξ) + κLi·[1 − h(ξ)] is the effective thermal conductivity coefficient, where κLi and κe are the thermal conductivity coefficients of electrode and electrolyte, respectively.

The internal heat generation rate Q, which also includes reversible heat and irreversible heat. Compared with irreversible heat, the influence of reversible heat can be ignored. The heat rate dominated by irreversible heat can be expressed as:

where qohmic is the Joule heat generated by ion resistance, qover is the Joule heat generated by overpotential. De and DLi represent the diffusion coefficients of the electrolyte and electrode, respectively. φe and φLi are the potential of the electrolyte and electrode, respectively. Uj represents the open-circuit potential, and as is the empirical factor.

The relationship between the diffusion coefficient of lithium-ion and temperature can be established through the Arrhenius empirical equation:

where pe = 2.582 × 10−9 m2·s−1 and b = 2.735 × 103 mol m−3 represent the pre-index and correlation coefficient independent of temperature, respectively. ED is the activation energy.

2.2.2. Mechanical Coupling Method

The growth of lithium dendrites in solid-state lithium batteries under stress coupling conditions is simulated by the phase field method. Based on the Helmholtz free energy functional of the dendrite growth model established by Chen et al. [16], the influence of the stress field is coupled to the Helmholtz free energy functional in the form of elastic free energy, and the free energy functional theory is obtained, as shown in Equation (1). Under the premise of the small deformation assumption, the elastic free energy density is based on the generalized Hooke’s law to establish the elastic strain energy of the composite electrolyte, as shown in Equation (14).

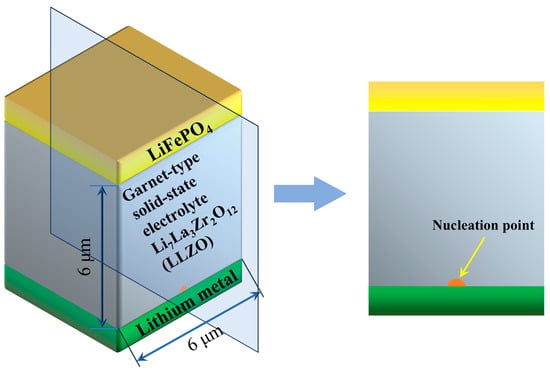

3. Finite Element Model

Based on the phase field theory content in the previous text, and the partial differential equations to be solved. The two-dimensional nonlinear phase field model is established by COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 software to simulate the micron-scale lithium dendrite growth, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of a finite element geometric model to simulate the micron-scale lithium dendrite growth.

The size of the finite element model is 6 μm × 6 μm. At the bottom position of the model is the negative electrode, and the material is lithium metal. The top position is set for the positive electrode, made of lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4). In order to facilitate the observation of the inhibition of dendrite growth by the mechanical strength of the electrolyte, the Garnet-type solid-state electrolyte Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) is used in the middle position. The nucleation site of lithium dendrites is set at the center of the lithium electrode to ensure the uniform growth of dendrites. The phase field simulation parameters of the lithium dendrite growth model are shown in Table 1. Furthermore, the initial values of the phase field equation are set through the Step Function module in COMSOL Multiphysics software. The nonlinear phase field control equation, concentration conservation equation, potential distribution equation, and temperature control equation are defined by Equations (9), (12), (13), and (15), respectively. The equation template obtained according to the General Form PED (g) module is and , where Γ is the conserved flux, f is the source item, da is the damping coefficient, ea is the mass coefficient. The differential equations in the template are set. The conserved fluxes corresponding to Equations (9), (12), (13), and (15) are , , , and , respectively. Similarly, the source items are , , , and , respectively. Damping Coefficients da are 1, 1, 1, and Cpρ, respectively. The mass coefficient ea is 0. The strain tensor is . The settings of the initial values and Dirichlet boundary conditions are shown in Table 2. In the present work, both the lithium metal and the solid-state electrolyte are modeled as small-strain, isotropic linear elastic materials, and plastic deformation and explicit fracture of either phase are not included. This choice allows us to focus on the effects of coupled electrochemical-mechanical-thermal fields and different initial nucleation geometries on the early-to-intermediate stages of dendrite evolution with a limited number of material parameters.

Table 1.

Phase field simulation parameters of the lithium dendrite growth model. Adapted from Refs. [31,32,33].

Table 2.

Initial value and boundary condition settings.

The partial differential equations can be solved by setting the boundary conditions and initial values in sequence. For mesh settings, a free quadrilateral mesh is adopted, with the maximum element size set to 0.05 μm, the minimum element size set to 0.005 μm, the maximum element growth rate and curvature factor set to 1.3 and 0.3, respectively, and the narrow region resolution set to 1. For the research operation, the Newton iterative method is adopted in this paper. The step size and time are set as follows: the operation time is 120 s, and the time step is set as 1 s.

4. Results and Discussion

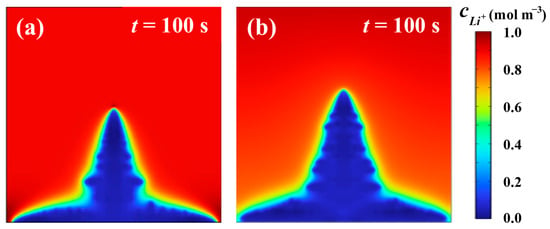

4.1. Verification of Finite Element Results

A dendrite growth model under the same research conditions as Wen et al. [34] is established. The lithium dendrites are relatively short with a height of 3.82 μm at an ambient temperature of 293.15 K. A comparison of lithium-ion concentration between present simulation results and previous results at 293.15 K and a potential difference of 0.1 V for 100 s is shown in Figure 4. In this paper, the lithium-ion concentration distribution under the same conditions is also established, as shown in Figure 4b. The height of the lithium dendrite is 4.04 μm at the same ambient temperature. The error between the previous result and the current result is 5.45%. By comparison, it can be found that the lithium-ion concentration distribution established by the two is basically the same. This consistency confirms that the model can provide reliable and suitable results for simulating lithium dendrite growth.

Figure 4.

Comparison of lithium-ion concentration between present simulation results and previous results when t = 100 s: (a) Lithium-ion concentration obtained by Wen et al. [34] (reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society); (b) lithium-ion concentration of present finite element results.

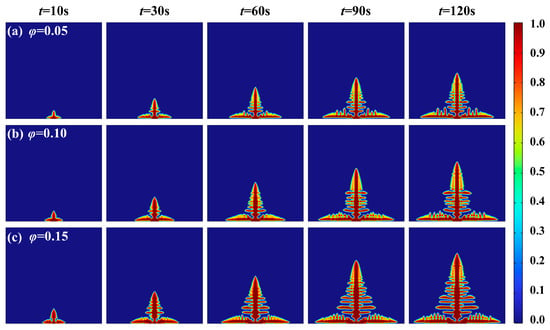

4.2. Influence of Electric Potential on Lithium Dendrite Growth

Existing research demonstrates that the lithium dendrite growth initiates once the electrical potential attains a critical threshold. This phenomenon is closely related to the local overpotential caused by the electric potential in the electrolyte. The choice of potential parameters plays a crucial role in the evolution process of dendrites. As revealed by electrochemical overpotential equations, the applied external electric potential directly modulates overpotential magnitude. When integrated with phase field theory, variations in electric potential further exert direct control over the dynamic evolution of lithium dendrite growth. To compare the influence of electric potential on the dendrite morphology of lithium, the lithium dendrite morphology diagrams were obtained by setting the electric potentials of 0.05 V, 0.10 V, and 0.15 V in the finite element model, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. When electric potentials increase from 0.15 V to 0.05 V, the critical nucleation time increases from 0.11 s (4.2 MPa) to 0.25 s (5.2 MPa), as stress reduces the lithium-ion flux at the electrode-electrolyte interface. As shown in Figure 5, the magnitude of the electric potential directly influences the diameter size. Higher voltages result in greater overpotential, which significantly accelerates the lithium dendrite growth rate. This observation suggests that elevated overpotential promotes the dendrite nucleation. The underlying mechanism is that overpotential enhances the driving force for dendrite evolution and intensifies the overall evolution process.

Figure 5.

Lithium dendrite growth morphology under different electric potentials: (a) φ = 0.05 V; (b) φ = 0.10 V; (c) φ = 0.15 V.

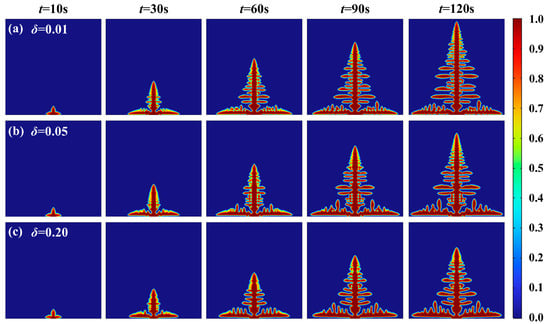

4.3. Influence of Anisotropic Intensity on Lithium Dendrite Growth

The anisotropy strength is one of the key physical parameters that affect the growth morphology and orientation of lithium dendrites. Especially in the solid electrolyte systems, it interacts with the elastic modulus of the electrolyte and exerts a significant regulatory effect on the tip splitting and trunk growth of dendrites [35]. Phase-field simulations have shown that solid electrolytes with high anisotropic moduli can effectively hinder the mechanical penetration of lithium dendrites. Based on this mechanism, incorporating MXene nanosheets into the lithium metal anode can establish an MXene-bonded transport network, enhancing the mechanical strength of the electrolyte and suppressing dendrite propagation [36]. According to the free energy functional theory, the anisotropy of surface energy plays a critical role in determining the direction of lithium deposition. To investigate the effect of anisotropy intensity on dendrite morphology, simulations are conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 with δ values set at 0.01, 0.05, and 0.20, respectively. The lithium dendrite growth morphology under varying anisotropic intensities at different time intervals is presented in Figure 6. The maximum longitudinal growth rate decreases 47% (from 0.042 to 0.022 μm/s) by anisotropic intensity from 0.20 to 0.01, attributed to stress-induced reduction in effective diffusion coefficient and increased interfacial resistance.

Figure 6.

Lithium dendrite growth morphology with different anisotropic intensities: (a) δ = 0.01; (b) δ = 0.05; (c) δ = 0.20.

It is observed that during the evolution process, when the anisotropy intensity is relatively low, the lateral branches of the dendrites develop continuously toward both sides, forming new branches, with multiple secondary lateral branches emerging from the primary ones. This occurs because, within the phase-field method, the anisotropy intensity directly influences the gradient energy coefficient, thereby increasing the magnitude of interfacial free energy and amplifying interfacial instability. From the phase-field morphology results, it can be seen that as the anisotropic intensity increases, branching growth along the dendritic trunk becomes more pronounced. Meanwhile, the lithium-ion concentration gradient at the discontinuity continues to rise, leading to a sharp tip phenomenon.

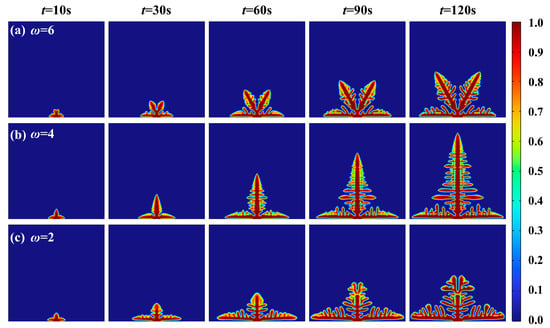

4.4. Influence of Anisotropic Modulus on Lithium Dendrite Growth

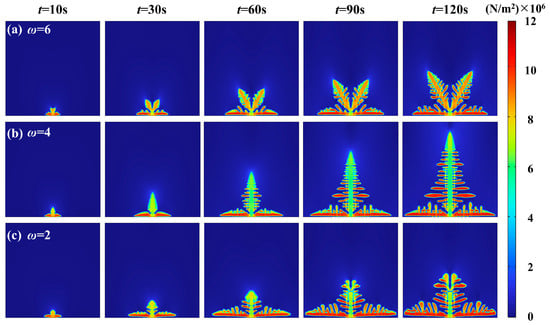

The anisotropic modulus also exerts a significant influence on the formation and growth of lithium dendrites. As evident from the phase field equation above, these anisotropic moduli directly affect the gradient coefficient, which in turn is incorporated into the phase field model governing lithium dendrite growth within solid-state electrolytes. Therefore, this section investigates the influence of different anisotropic moduli on the phase field model of lithium dendrites in solid-state electrolytes. Specifically, the anisotropic modulus is adjusted in the lithium dendrite phase field model within the electrolyte and set to ω = 2, ω = 4, and ω = 6 for analysis, respectively. When the anisotropic modulus is set to 2, the dominant growth direction of the dendrite is oriented horizontally. With an anisotropic modulus of 4, the dominant growth directions occur at 0°, 90°, 180°, and 360°. When the anisotropic modulus is set to 6, the dominant growth directions are 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 360°. The corresponding lithium dendrite growth morphology under different anisotropic moduli is presented in Figure 7. Since the nucleation points are defined at the bottom, the growth direction of the dendrites is in a 0° to 180° angular range. As can be seen from Figure 7, adjusting the anisotropy modulus can exert a discernible inhibitory effect on the growth of lithium dendrites, which is particularly more pronounced along the vertical direction. The results of the numerical simulation show that the growth height of the longitudinal dendrites with ω = 6 (the preferred growth direction of hexagonal shape) is 18% less than that of ω = 2 and 49% less than that of ω = 4 (Figure 7). This can be achieved by doping LLZO electrolytes with Mg2+ or Al3+, which modify crystal orientation and increase anisotropic modulus.

Figure 7.

Lithium dendrite growth morphology under different anisotropic moduli: (a) ω = 6; (b) ω = 4; (c) ω = 2.

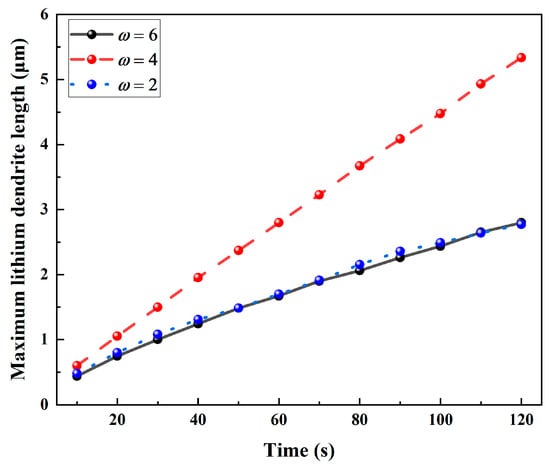

When the preferred growth direction of the anisotropic modulus deviates from the vertical orientation, a constant current condition causes lithium atoms to distribute across multiple directions during deposition. Consequently, some lithium atoms from regions of initially high deposition are redirected along other orientations, which reduces the growth rate of lithium dendrites along the longitudinal direction. As shown in Figure 8, the vertical preferred growth direction leads to the maximum height of lithium dendrites. Future studies could focus on precise control of the degree of anisotropy through material design, particularly by employing solid electrolytes with specific crystal structures or microstructural features, to effectively suppress lithium dendrite growth.

Figure 8.

Curves of the maximum length of lithium dendrites with different anisotropic moduli varying with time.

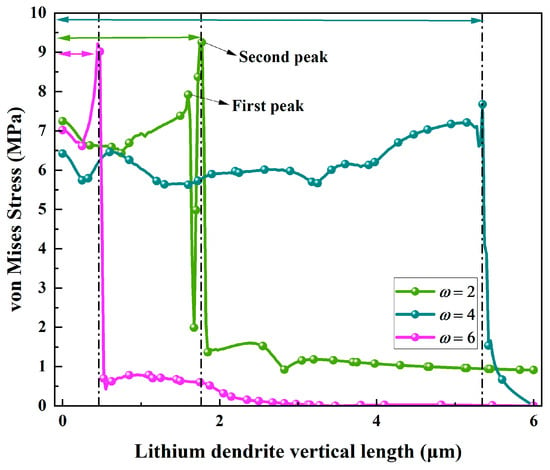

Furthermore, based on the phase-field model coupled with mechanical stress, this study analyzes the von Mises stress distribution resulting from different anisotropic moduli under varying preferred growth directions, as presented in Figure 9. The von Mises stress distribution visually illustrates the correlation between anisotropic moduli and stress localization. For the highly anisotropic lithium dendrites, the von Mises stress concentrates at the tip regions and directional bifurcations; for the moderately anisotropic dendrites, it is predominantly localized at the main stem tips; whereas in low anisotropy dendrites, the von Mises stress is widely dispersed throughout the multi-branch regions. This phenomenon reveals the regulation of anisotropic moduli on the feedback mechanism between stress and dendrite growth. The vertical growth region not only serves as an active site for rapid lithium-ion deposition but also represents a mechanically sensitive zone during dendrite evolution. By modulating the location and magnitude of von Mises stress concentration, anisotropic moduli further influence the growth kinetics of dendrites.

Figure 9.

von Mises stress distribution with different anisotropic moduli: (a) ω = 6; (b) ω = 4; (c) ω = 2.

The influence of anisotropic moduli on the mechanical behavior of lithium dendrites is further quantified in Figure 10 by analyzing the evolution of von Mises stress with respect to the vertical length of the dendrites. When the anisotropic modulus is set to 6, an initial stress peak of 9.22 MPa occurs as the lithium dendrite vertical length reaches 0.45 μm, after which the stress rapidly decays to near-zero levels. This behavior is attributed to the directional branching morphology resulting from the high anisotropy modulus. The regular growth pattern minimizes the accumulation of disordered stress, thereby enhancing the mechanical stability of dendrites and effectively suppressing the risk of electrolyte penetration due to stress concentration. When the anisotropic modulus is set to 4, the von Mises stress remains at a relatively high level of 5.67–7.68 MPa as the lithium dendrite vertical length increases from 0 μm to 5.35 μm. A pronounced stress peak emerges in the later stage, reflecting the mechanical behavior characteristic of main trunk dendrite growth: the longitudinal extension of the main trunk continuously accumulates stress, while the development of secondary branches further intensifies stress concentration. This stress behavior increases the possibility of dendrites penetrating the electrolyte. When the anisotropic modulus is set to 4, the von Mises stress is at a relatively high level of 6.15–6.97 MPa as the lithium dendrite vertical length increases from 0 μm to 0.73 μm. As the lithium dendrite vertical length reaches 1.60 μm, the stress attains its first peak of 7.71 MPa. When the dendrite length further increases to 1.75 μm, a second stress peak of 9.17 MPa is observed. During these stages, the stress exhibits significant fluctuations, and the multi-peak characteristics observed in the early and middle stages align well with the disordered multi-branched moss-like morphology of the dendrites. Frequent tip splitting and disordered growth lead to repeated cycles of stress concentration and release. The residual stress eventually indicates that the mechanical stability of such dendrites is the lowest.

Figure 10.

Variation of von Mises Stress curves with lithium dendrite vertical length for different anisotropic moduli.

5. Conclusions

Based on the phase field theory, this study develops a multi-physics coupling model to systematically investigate the evolution mechanisms and suppression strategies of lithium dendrites induced by key physical parameters (electric potential, anisotropic intensity/modulus) through the coupled effects of mechanical, thermal, and electrochemical fields. The governing nonlinear partial differential equations are formulated by combining the Cahn-Hilliard and Ginzburg-Landau equations. Numerical simulations are performed to analyze the influence of various physical parameters on the morphological evolution of lithium dendrites. Quantitative predictions (e.g., absolute dendrite length at specific times) of lithium dendrite suppression strategies in an LLZO electrolyte are provided for the simulated conditions with electric potentials of 0.05–0.15 V, anisotropic intensity of 0.01–0.2, and anisotropic modulus of 2–6. The main findings of this work are summarized as follows:

Based on the established phase field equation, the effects of electric potential, anisotropic intensity, and anisotropic modulus on the growth of lithium dendrites are investigated. It is found that reducing the interfacial electric potential between the electrode and electrolyte lowers the overpotential in the phase-field equations, which decreases the lithium-ion migration rate. This effectively suppresses the longitudinal growth of dendrites and slows their deposition kinetics. The reduction in anisotropic intensity leads to a significant decrease in the gradient-free energy at the electrode-electrolyte interface, thereby causing the deposition rate of lithium dendrites to slow down. The anisotropic modulus affects the growth direction of lithium dendrites. When the growth angle of diffused lithium dendrites is adjusted, the deposition rate of lithium dendrites in the longitudinal direction is alleviated.

In addition, the current model assumes small elastic deformation and ignores plastic flow, which may become significant at high stress (>50 MPa) or long cycling times. This investigation focuses on micron-scale dendrite evolution and does not consider macro-scale battery performance. Quantitative validation is limited to lithium-ion concentration distribution, with future work needed to compare with in situ experimental data (e.g., dendrite growth rate). The literature indicates that elastic-plastic deformation and fracture of both lithium metal and solid electrolytes become critical near failure and short-circuit conditions [37,38,39]. Extending the present elasticity-based framework to incorporate elastic-plastic constitutive behavior and electro-chemo-mechanical fracture of the electrolyte and lithium metal will therefore be an important direction of future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H. and J.X.; methodology, W.H.; software, W.H. and F.G.; validation, W.H., J.L. and F.G.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, W.H., J.L. and J.X.; data curation, J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.H., J.X. and F.G.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and J.L.; visualization, J.X. and F.G.; supervision, W.H.; project administration, W.H.; funding acquisition, W.H. and J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 12202407) and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (grant numbers: 202503021211122; 202403021221111).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Viswanathan, V.; Epstein, A.H.; Chiang, Y.M.; Takeuchi, E.; Bradley, M.; Langfordc, J.; Winter, M. The challenges and opportunities of battery-powered flight. Nature 2022, 601, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Xue, M.; Zhang, C. Modified Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) and LLZO-polymer composites for solid-state lithium Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 39, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.Q.; Xie, J.M. Reducing diffusion induced stress of bilayer electrode system by introducing pre-strain in lithium-ion battery. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2021, 18, 020909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, H.; Li, H. Flame-retarding quasi-solid polymer electrolytes for high-safety lithium metal Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 67, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.Q.; Bo, X.Q.; Xie, J.M.; Xu, T.T. Mechanical properties of macromolecular separators for lithium-ion batteries based on nanoindentation experiment. Polymers 2022, 14, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Lei, D.; Yang, W.; Liu, C.; Shi, K.; Hao, X.G.; Shen, L.; Lv, W.; Li, B.H.; Yang, Q.H.; et al. Low Resistance-Integrated All-Solid-State Battery Achieved by Li7La3Zr2O12 Nanowire Upgrading Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) Composite Electrolyte and PEO Cathode Binder. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1805301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.Q.; Xie, J.M.; Bo, X.Q.; Wang, F.H. Resistance exterior force property of lithium-ion pouch batteries with different positive materials. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 4976–4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiner, L.J.; Bezerra, C.A.G.; Howell, T.G.; Powell, A.S. Digital Printing of Solid-State Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1900737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Han, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, B.G.; Jung, K.N.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, S.W. Elastomeric electrolytes for high-energy solid-state lithium batteries. Nature 2022, 601, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCalla, E. Electrodes with 100% active materials. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 1056–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.S.; Liang, W.Z.; Su, S.; Jiang, X.F.; Bando, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ma, Z.S.; Wang, X.B. Advances of solid polymer electrolytes with high-voltage stability. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, C.; Cai, X.; Yue, K.; Yue, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yuan, H.; Nai, J.; Zou, S.; et al. Structural composite solid electrolyte interphases on lithium metal anodes induced by inorganic/organic Activators. Mater. Today Energy 2024, 46, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, V.; Chazalviel, J.N.; Rosso, M.; Sapoval, B. The role of the anions in the growth speed of fractal electrodeposits. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1990, 290, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Chien, P.H.; Amouzandeh, G.; Hou, D.; Truong, E.; Oyekunle, I.P.; Bhagu, J.; Holder, S.W.; Xiong, H.; et al. Dendrite formation in solid-state batteries arising from lithium plating and electrolyte reduction. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Wang, Y.; Dai, L.; Yuan, C. Cell failures of All-solid-state lithium metal batteries with inorganic solid electrolytes: Lithium Dendrites. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 33, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cheng, Z.; Liao, Y.Q.; Yuan, L.X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.H. Selection of Redox Mediators for Reactivating Dead Li in Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.; Kramer, D.; Mönig, R. Microscopic observations of the formation, growth and shrinkage of lithium moss during electrodeposition and dissolution. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 136, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.; Kramer, D.; Mönig, R. Mechanisms of dendritic growth investigated by in situ light microscopy during electrodeposition and dissolution of lithium. J. Power Sources 2014, 261, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Ma, S.B.; Lee, D.J.; Im, D.; Doo, S.G.; Yamamoto, O. A highly reversible lithium metal anode. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.L.; Bockris, J.O.M. The electrolytic growth of dendrites from ionic solutions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1962, 268, 485–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chazalviel, J.N. Electrochemical aspects of the generation of ramified metallic electrodeposits. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; Newman, J. Dendrite Growth in Lithium/Polymer Systems: A Propagation Model for Liquid Electrolytes under Galvanostatic Conditions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akolkar, R. Mathematical model of the dendritic growth during lithium electrodeposition. J. Power Sources 2013, 232, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, J.E.; Boettinger, W.J.; Warren, J.A.; McFadden, G.B. Phase field modeling of electrochemistry. I. Equilibrium. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 021603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.Y.; Qi, Y.; Xue, F.; Bhattacharya, S.; Harris, S.J.; Chen, L.Q. Nonlinear phase-field model for electrode-electrolyte interface evolution. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 86, 051609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.W.; Liang, L.Y.; Liu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Lu, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.Q. Modulation of dendritic patterns during electrodeposition: A nonlinear phase-field model. J. Power Sources 2015, 300, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.B.; Huang, Z.J.; Gao, L.; Zuo, Y.X.; Zhu, J.L.; Sun, M.Y.; Zhao, S.S.; Zheng, J.X.; Han, S.B.; Zou, R.Q. Dynamic control of lithium dendrite growth with sequential guiding and limiting in all-solid-state batteries. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryanfar, A.; Medlej, S.; William, A.G., III. Morphometry of Dendritic Materials in Rechargeable Batteries. J. Power Sources 2021, 481, 228914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Bie, Y.; Cui, X.; Xiong, G.P.; Chen, L. A computational investigation of thermal effect on lithium dendrite growth. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 161, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguello, M.E.; Gumulya, M.; Derksen, J.; Utikar, R.; Calo, V.M. Phase-field modeling of planar interface electrodeposition in lithium-metal batteries. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.D.; Wang, Z.J. Effects of pressure, temperature, and plasticity on lithium dendrite growth in solid-state electrolytes. J. Solid. State Electrochem. 2023, 27, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.L.; Lu, Y.J.; Chen, Z.P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, F.H. Phase-field investigation of dendrite suppression strategies for all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.Y.; Xie, J.M.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.K.; Hao, W.Q.; Tian, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, F.Z. Phase field simulation of dendrite growth in solid-state lithium batteries based on mechanical-thermo-electrochemical coupling. Acta Phys. Sin. 2025, 74, 070201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.G.; Zhang, M.L.; Wang, S.J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.X.; Zhang, D.Y.; Sun, X. Dynamic Evolution and Effective Tuning of Lithium Dendrites Revealed by Phase Field Model and 2D Numerical Simulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7881–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Liu, X.; Dou, R.; Liu, X.L.; Dou, R.F.; Wen, Z.; Zhou, W.N.; Liu, L. A three-dimensional multiphysics field coupled phase field model for lithium dendrite Growth. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroozan, T.; Sharifi-Asl, S.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Mechanistic understanding of Li dendrites growth by In- situ/operando imaging Techniques. J. Power Sources 2020, 461, 228135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Chang, L.G.; Song, Y.C.; He, L.H.; Ni, Y. Effect of plasticity on voltage decay studied by a stress coupled phase field reaction model. Extreme. Mech. Lett. 2021, 42, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.Z.; Mi, F.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Sun, C.W. Solid composite electrolyte with a Cs doped fluorapatite-interfacial layer enabling dendrite-free anodes for solid-state lithium batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehe, C.; Dal, H.; Schänzel, L.M.; Raina, A. A phase-field model for chemo-mechanical induced fracture in lithium-ion battery electrode particles. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 2016, 106, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.