Development of a Workflow for Topological Optimization of Cutting Tool Milling Bodies

Abstract

1. Introduction

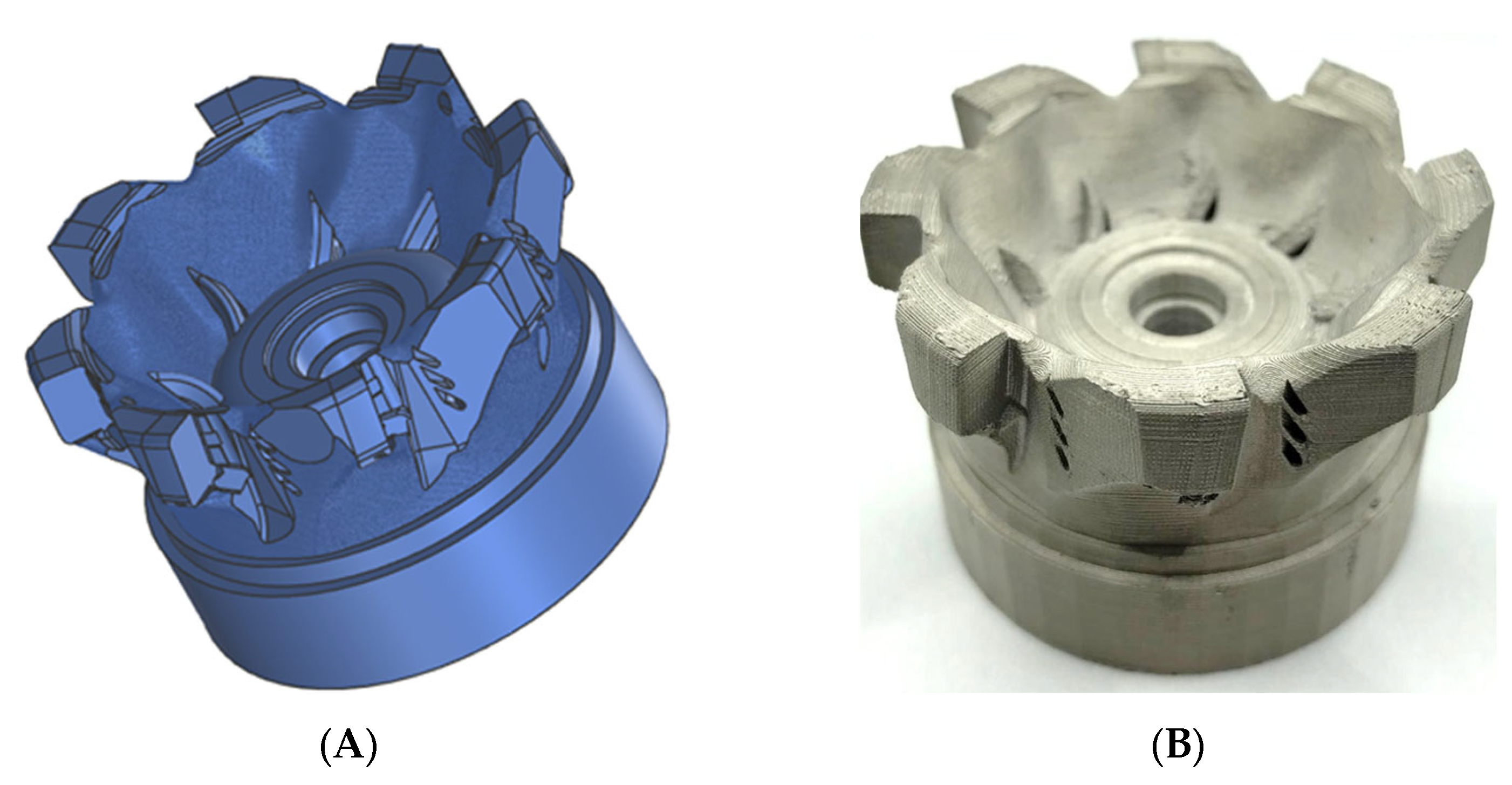

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

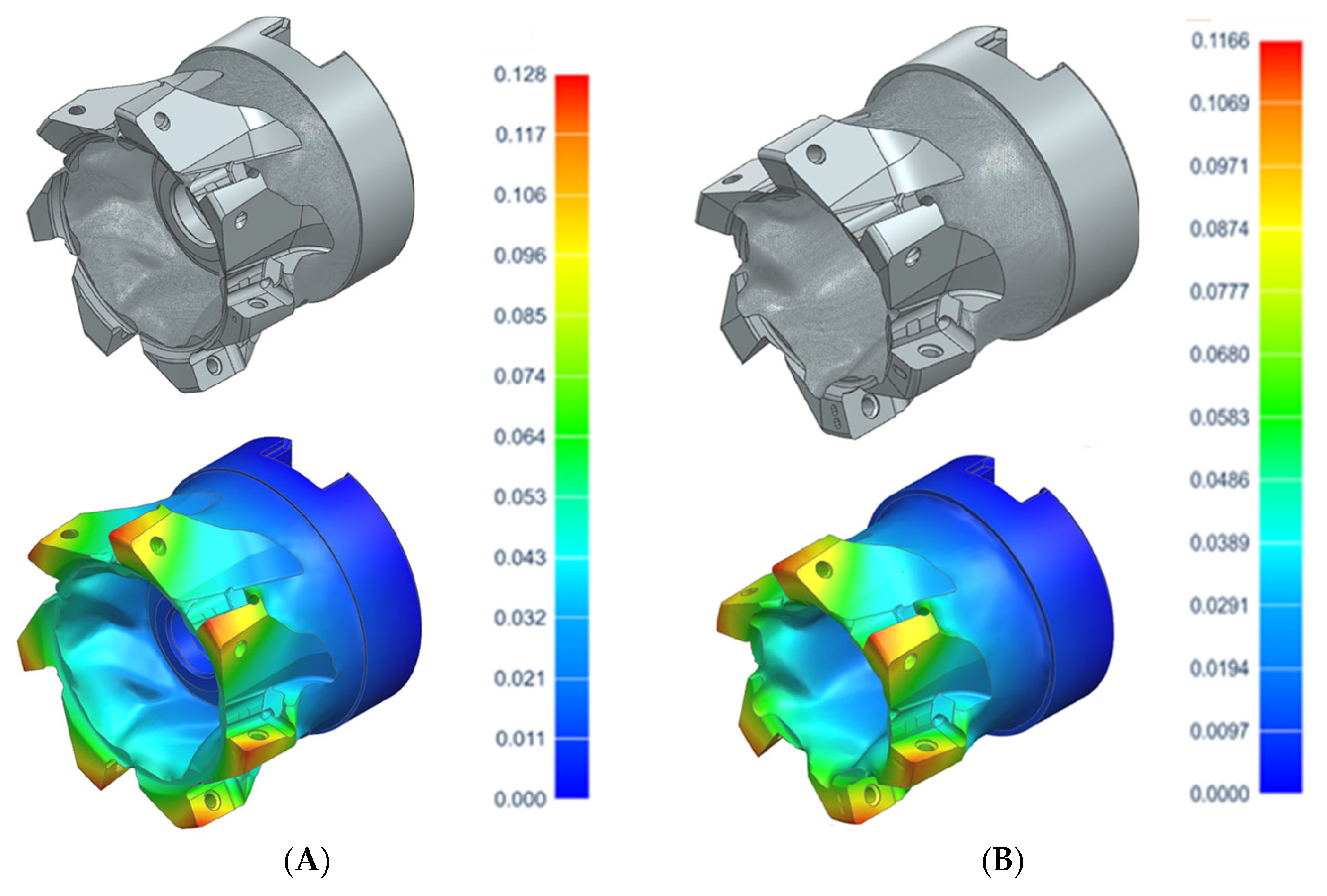

3.1. Topology Optimization

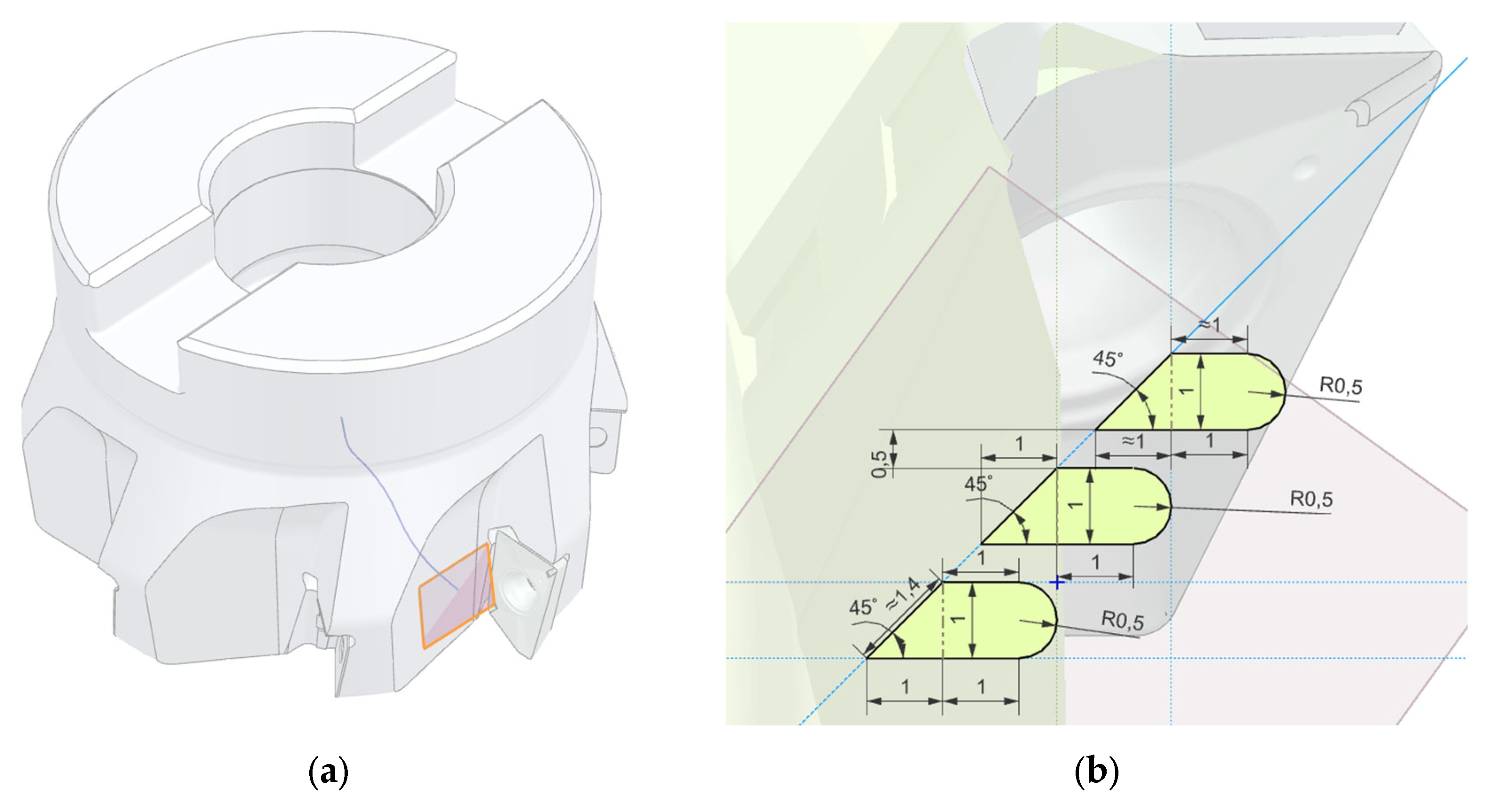

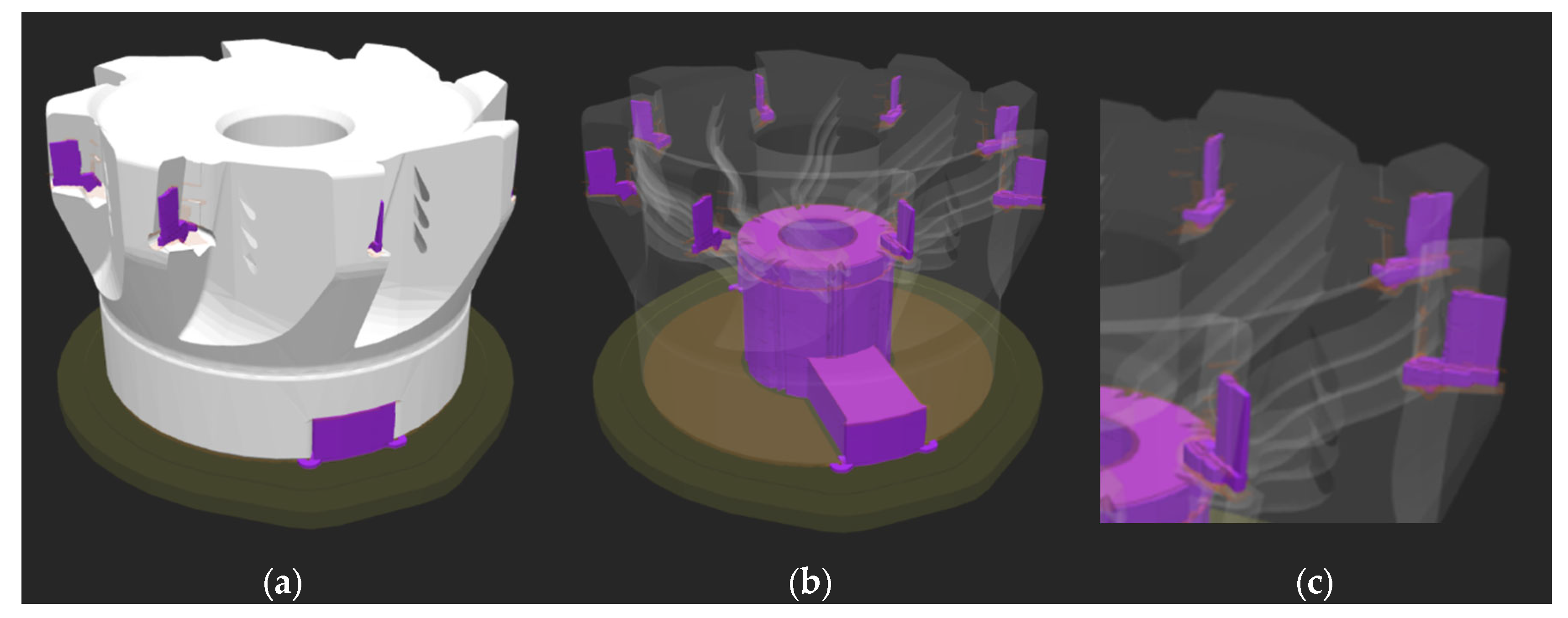

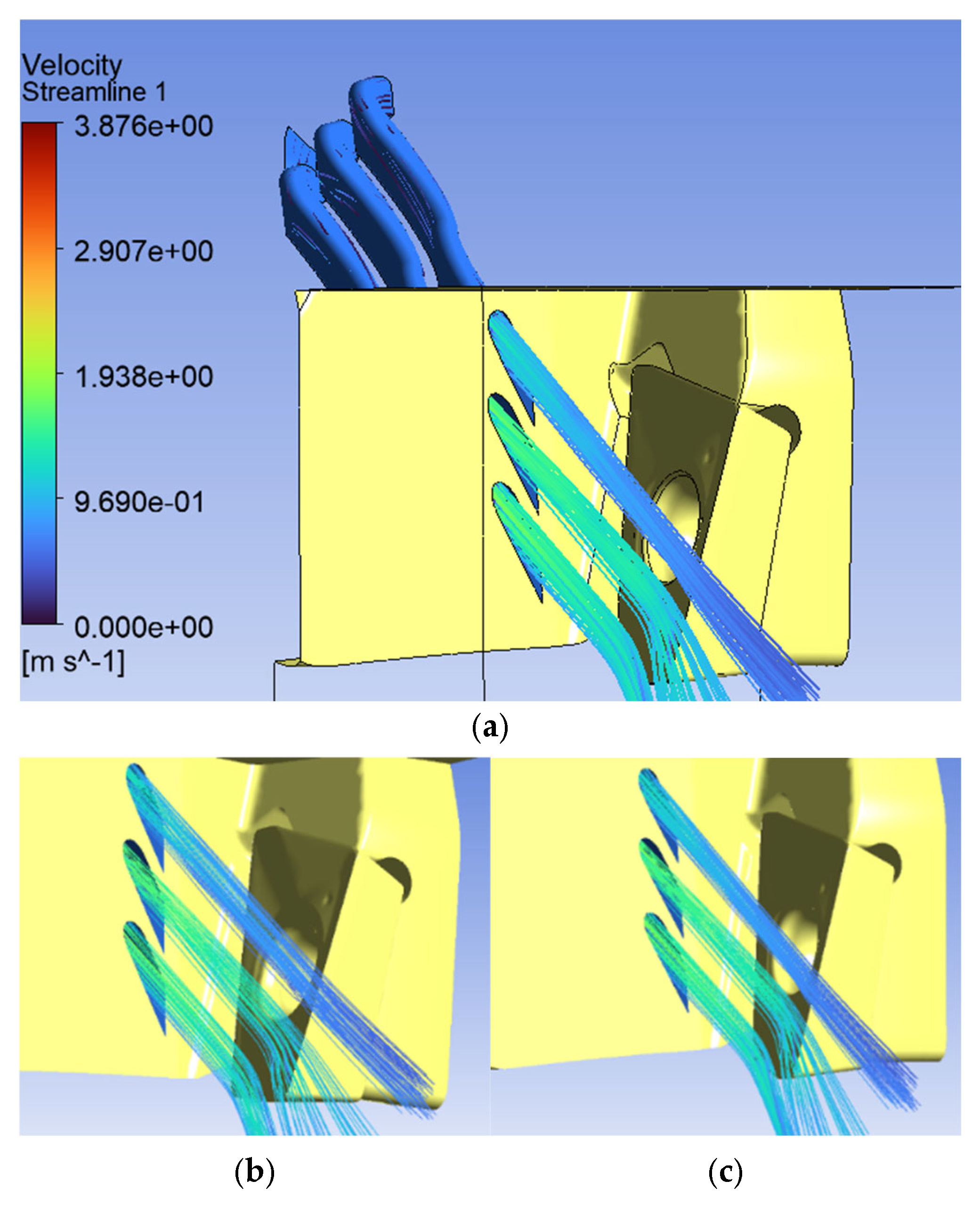

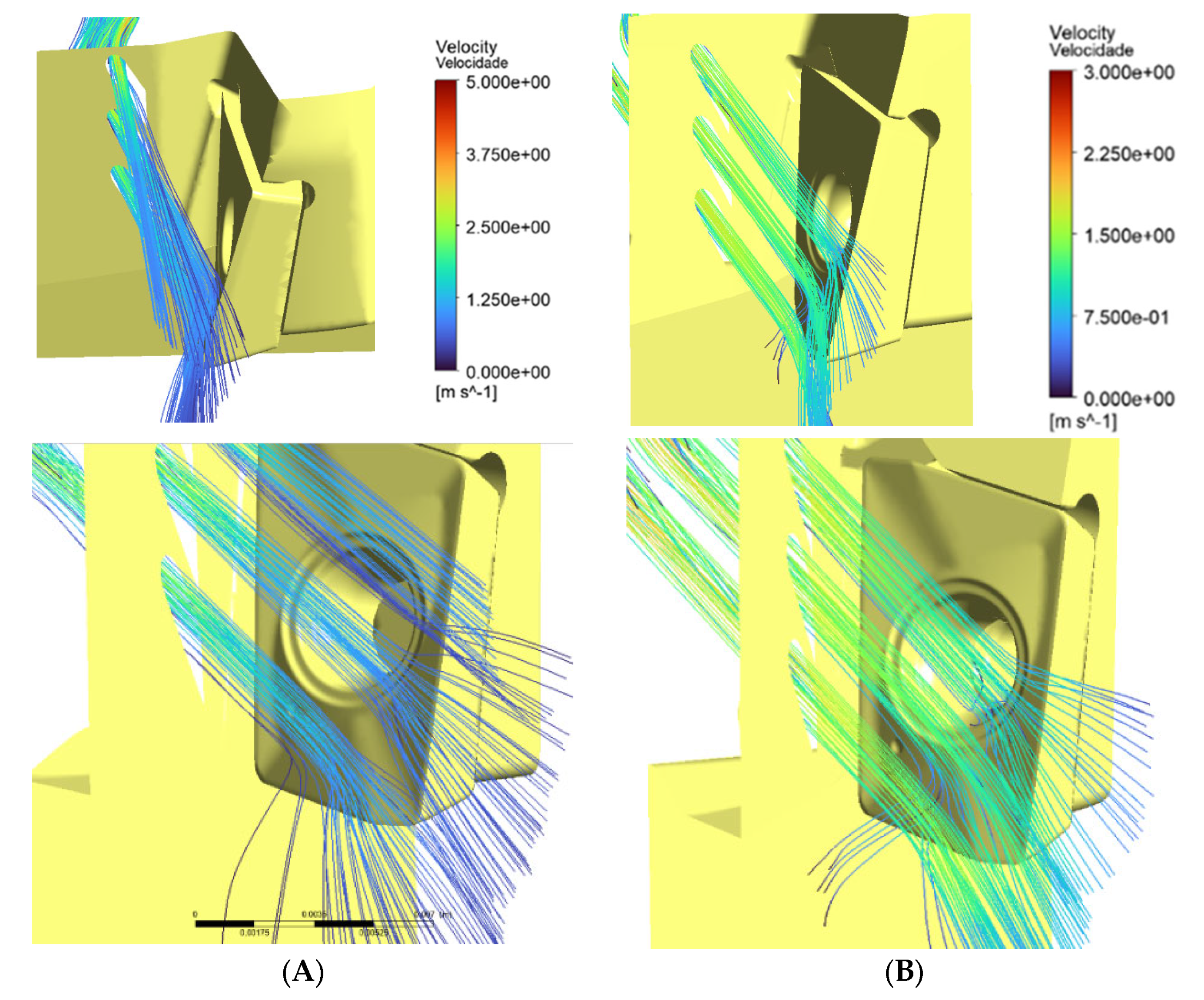

3.2. Coolant Channel Design

3.3. Print Preparation

3.4. Post-Processing

3.5. Workflow Validation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, H.M. The machine tool industry and the effects of technological change. In Technology Shocks; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 59–97. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, F.; Coelho, H.; Emadinia, O.; Amaral, R.; Silva, T.; Gonçalves, N.; Marouvo, J.; Figueiredo, D.; de Jesus, A.; Reis, A. Additively manufactured milling tools for enhanced efficiency in cutting applications. In Proceedings of the Third European Conference on the Structural Integrity of Additively Manufactures Materials, (ESIAM23), Porto, Portugal, 4–6 September 2023; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leymann, F.; Roller, D. Production Workflow: Concepts and Techniques; Prentice-Hall: EnglewoodCliffs, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, J.L.; Guevara, A.; Aguayo, A. Workflow: A solution for cooperative information system development. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2003, 9, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Hornick, M.; Sheth, A. An overview of workflow management: From process modeling to workflow automation infrastructure. Distrib. Parallel Databases 1995, 3, 119–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxel, K.D.; Bandyopadhyay, A. First Demonstration of Additive Manufacturing of Cutting Tools using Directed Energy Deposition System: Stellite™-Based Cutting Tools. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 25, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, B. The development and use of machine tools in historical perspective. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1984, 5, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Sequeiros, E.W.; Santos, R.F.; Vieira, M.F. Benchmarking L-PBF Systems for Die Production: Powder, Dimensional, Surface, Microstructural and Mechanical Characterisation. Metals 2024, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Ç.V.; Kıvak, T.; Sarıkaya, M.; Şirin, Ş. Evaluation of tool wear, surface roughness/topography and chip morphology when machining of Ni-based alloy 625 under MQL, cryogenic cooling and CryoMQL. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2079–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadria, S.I.A.; Harmain, G.A.; Wani, M.F. Influence of Tool Tip Temperature on Crater Wear of Ceramic Inserts During Turning Process of Inconel-718 at Varying Hardness. Tribol. Ind. 2020, 42, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, S.; Ghiotti, A.; Bruschi, S. Hybrid lubricating/cooling strategies to reduce the tool wear in finishing turning of difficult-to-cut alloys. Wear 2017, 376–377, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuj Srivathsa, S.S.; Muralidharan, B. Review on 3D printing techniques for cutting tools with cooling channels. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, M.; Jia, D.; Li, C. Lubricant transportation mechanism and wear resistance of different arrangement textured turning tools. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, G.; Yudianto, A. Functional design and testing of additively manufactured milling cutting heads with enhanced structural and lubrication properties. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 4165–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischmann, P.; Galland, S.; Zange, F. Improved coolant channel flow efficiency for grooving tools through simulation and additive manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2025, 133, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Xiao, G.; Chen, Z.; Yi, M.; Xu, C.; Fan, L.; Li, G. Analysis of tool wear of TiAlN coated tool, machined surface morphology and chip during titanium alloy milling. Tribol. Int. 2024, 197, 109751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall, R.; Lenrick, F.; M’Saoubi, R.; Ståhl, J.-E.; Bushlya, V. Performance and wear mechanisms of uncoated cemented carbide cutting tools in Ti6Al4V machining. Wear 2021, 477, 203824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Tool wear on machining of difficult-to-machine materials: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 989–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; Yao, X.; Zhao, B.; Ding, W.; Xu, J. Wear mechanisms of superhard cutting tools in machining of SiCp/Al composites. Wear 2025, 564–565, 205695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogedengbe, T.S.; Okediji, A.P.; Yussouf, A.A.; Aderoba, O.A.; Alabi, I.O.; Alonge, O.I. The Effects of Heat Generation on Cutting Tool and Machined Workpiece. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering for Sustainable World, Ota, Nigeria, 3–8 July 2019; IOP Publishing Ltd: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Komanduri, R.; Hou, Z.B. Thermal modeling of the metal cutting process * Part II: Temperature rise distribution due to frictional heat source at the tool}chip interface. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2001, 43, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B. Multi-pattern failure modes and wear mechanisms of WC-Co tools in dry turning Ti–6Al–4V. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 24512–24525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, T.; Bergs, T.; Döbbeler, B. Additively manufactured milling tool with focused cutting fluid supply. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesriklioglu, S. Ineffectiveness of flood cooling in reducing cutting temperatures during continuous machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 3957–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, U.S.; Sarma, D.K.; Davim, J.P. Environmentally Friendly Machining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Race, A.; Zwierzak, I.; Secker, J.; Walsh, J.; Carrell, J.; Slatter, T.; Maurotto, A. Environmentally sustainable cooling strategies in milling of SA516: Effects on surface integrity of dry, flood and MQL machining. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchosal, A.; Serra, R.; Leroy, R.; Hamdi, H. Numerical optimization of the Minimum Quantity Lubrication parameters by inner canalizations and cutting conditions for milling finishing process with Taguchi method. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhanapu, M.; Chaganti, P.K.; Ghosh, A.; Mahale, A.; Kulkarni, O.P. Whole-body inhalation study of nanoparticle-enhanced vegetable oil metalworking fluids in mice for assessing occupational health risks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Machado, A.R.; França, P.H.P.; Pintaude, G.; Unune, D.R.; Kuntoğlu, M.; Krolczyk, G.M. A comprehensive review of machinability of difficult-to-machine alloys with advanced lubricating and cooling techniques. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mativenga, P.; Schoop, J.; Jawahir, I.S.; Biermann, D.; Kipp, M.; Kilic, Z.M.; Özel, T.; Wertheim, R.; Arrazola, P.; Boing, D. Engineered design of cutting tool material, geometry, and coating for optimal performance and customized applications: A review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachert, C.; Liu, H.; Lakner, T.; Schraknepper, D.; Bergs, T. CFD simulation to optimize the internal coolant channels of an additively manufactured milling tool. Procedia CIRP 2021, 102, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Jiang, H.; Tang, X.; Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hu, Y. Design and performance of an internal-cooling turning tool with micro-channel structures. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 45, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofail, S.A.M.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S.; O’Donoghue, L.; Charitidis, C. Additive manufacturing: Scientific and technological challenges, market uptake and opportunities. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.; Nóbrega, J.M. Conformal Cooling Channels in Injection Molding and Heat Transfer Performance Analysis Through CFD—A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; Al Tamimi, Z.; Hansotte, G.; Sunkara, L.D.; Bernat, J. Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Roan Eagle, I.N.; Yodo, N. A Review on Filament Materials for Fused Filament Fabrication. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Gold, S.A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: II. Materials, dimensional accuracy, and surface roughness. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Maia, M.; Costa, J. Production of an Office Stapler by Material Extrusion Process, using DfAM as Optimization Strategy. U.Porto J. Eng. 2023, 9, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Pejak Simunec, D.; Kandjani, A.E.Z.; Trinchi, A.; Sola, A. A Review of Fused Filament Fabrication of Metal Parts (Metal FFF): Current Developments and Future Challenges. Technologies 2024, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Sequeiros, E.; Vieira, M.T.; Vieira, M. Additive Manufacturing: Material Extrusion of Metallic Parts. U.Porto J. Eng. 2021, 7, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Sequeiros, E.W.; Vieira, M.F. Fused Filament Fabrication for Metallic Materials: A Brief Review. Materials 2023, 16, 7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, M.; Bragaglia, M.; Slemenik Perše, L.; Nanni, F. Advancements in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review of Material Extrusion with Highly Filled Polymers. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Sequeiros, E.W.; Figueiredo, D.; Reis, A.R.; Vieira, M.F. Optimizing Metal AM Potential through DfAM: Design, Performance, and Industrial Impact; IntechOpen: Hamilton, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, I.B.; Cunha, B.R.; Marouvo, J.; Figueiredo, D.; Guimarães, B.M.; Vieira, M.F.; Costa, J.M. Topology Optimization of a Milling Cutter Head for Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2025, 15, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KENNAMETAL. KM Solid End Mill Torque & Horsepower Calculator. Available online: https://www.kennametal.com/be/en/resources/engineering-calculators/end-milling/km-solid-end-mill-torque-and-horsepower.html (accessed on 30 April 2025).

| Tool Reference | Diameter (mm) | Number of Inserts | Role in Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| 063 A 201 90-08-08-022040 | 63 | 8 | Development |

| 050 A 201 90-07-08-022040 | 50 | 7 | Validation |

| 040 A 201 90-06-08-022040 | 40 | 6 | Validation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cunha, B.R.; Guimarães, B.M.; Figueiredo, D.; Vieira, M.F.; Costa, J.M. Development of a Workflow for Topological Optimization of Cutting Tool Milling Bodies. Metals 2026, 16, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010116

Cunha BR, Guimarães BM, Figueiredo D, Vieira MF, Costa JM. Development of a Workflow for Topological Optimization of Cutting Tool Milling Bodies. Metals. 2026; 16(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Bruno Rafael, Bruno Miguel Guimarães, Daniel Figueiredo, Manuel Fernando Vieira, and José Manuel Costa. 2026. "Development of a Workflow for Topological Optimization of Cutting Tool Milling Bodies" Metals 16, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010116

APA StyleCunha, B. R., Guimarães, B. M., Figueiredo, D., Vieira, M. F., & Costa, J. M. (2026). Development of a Workflow for Topological Optimization of Cutting Tool Milling Bodies. Metals, 16(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010116