1. Introduction

The ladle furnace (LF) is a critical secondary steelmaking unit dedicated to refining operations under a non-oxidizing atmosphere, typically ensured by argon stirring and arc heating in the presence of a basic white slag [

1,

2]. The two main operations during this step consist of (1) harmful particles removal, including impurities (i.e., sulfur and oxygen) and inclusions (i.e., nonmetallic particles) that float to the slag, and (2) the addition of alloying elements to adjust the concentration of each targeted element [

3]. The transformation processes of steel, particularly the LF refining step, are known to be complex thermodynamic systems circumscribed by an interplay of thermodynamic equilibriums responsible for the direction of chemical reactions, while kinetics define their rates. Thus, tracking and controlling both metallurgical and thermodynamic variables are crucial. Given the complexity of the reactions occurring simultaneously, modeling an LF process becomes even more challenging when developing new metallurgical schedules to produce novel steel grades. Computational thermodynamics, and more specifically the CALPHAD (Calculation of Phase Diagrams) approach, has become a powerful tool in modern metallurgical process modeling. Thus, the development of CALPHAD databases has led to the emergence of high accuracy computer-based tools since the 1980s [

4], providing the foundation for Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME) [

5,

6,

7]. The simulation of refining processes is typically performed by coupling the kinetics of multiphase reactions with thermodynamic databases describing liquid steel and slag oxides at the phase interface. Several studies have established such kinetic descriptions using the Effective Equilibrium Reaction Zone (EERZ) method, in which local equilibrium is assumed within an effective reaction volume to describe interactions between the bulk phases and the interface [

8]. EERZ-based modeling has demonstrated strong agreement with both experimental observations and industrial data. The main commercial thermodynamic software and methods used in the literature included FactSage (

http://www.factsage.com/, assessed on 13 January 2026), Metsim (

https://metsim.com/, assessed on 13 January 2026), ChemApp (

https://gtt-technologies.de/software/chemapp/, assessed on 13 January 2026), and SimuSage (

https://gtt-technologies.de/software/simusage/, assessed on 13 January 2026), in addition to the Thermo-Calc

® approach used in this work.

This latter approach was selected because the Thermo-Calc

® software includes a powerful add-on, referred to as the Process Metallurgy Module (PMM), which was developed by integrating thermodynamic equilibria with EERZ-based kinetic descriptions and robust industrial data, enabling a more accurate in silico representation of steelmaking processes [

9,

10]. Furthermore, when coupled with CALPHAD-based oxide databases such as TCOX, the PMM provides an industrially validated framework for modeling kinetically constrained slag–metal reactions throughout the tap-to-tap refining cycle and supports the design of optimized process schedules [

10,

11]. In this context, this approach was applied herein to upgrade the S355J2R steel grade to S355J2W and S355J2WP grades at the industrial scale through the in silico definition of optimized LF refining schedules.

Obviously, using this approach, one should expect that both grades fit the weathering steel standards and properties. COR-TEN (CORrosion resistance TENsile) is a well-known commercial weathering steel developed since the 1930s to exhibit higher anti-corrosion properties compared to conventional carbon steel, while maintaining superior tensile strength [

12]. This family of steels undergoes a corrosion process characterized by the formation of a self-protective oxide layer, meaning less maintenance costs related to periodic painting. ArcelorMittal© is known for producing two weathering steels under the trade names Arcorox

® for long products and Indaten

® for heavy plates or steel coils. These products are mainly oriented towards architecture and construction applications [

13]. As reported in

Table 1, when producing a weathering steel, specific composition ranges of certain alloys should be respected to reach a low-carbon steel grade with enhanced corrosion resistance properties. In this regard, Cr, Cu, and P are the main alloying elements known for their contribution in enriching, forming, and stabilizing the protective patina layer over time and with exposure to a corrosive environment [

14,

15,

16]. Furthermore, several studies also highlighted the effect of Si content on the stabilization and enhancement of such protective rust layers [

17]. After prolonged exposure, Cr-substituted ultra-fine goethite, which has a maximum crystal size of about 15 nm, undergoes a long-term phase transformation towards its final state of fine goethite (FG)

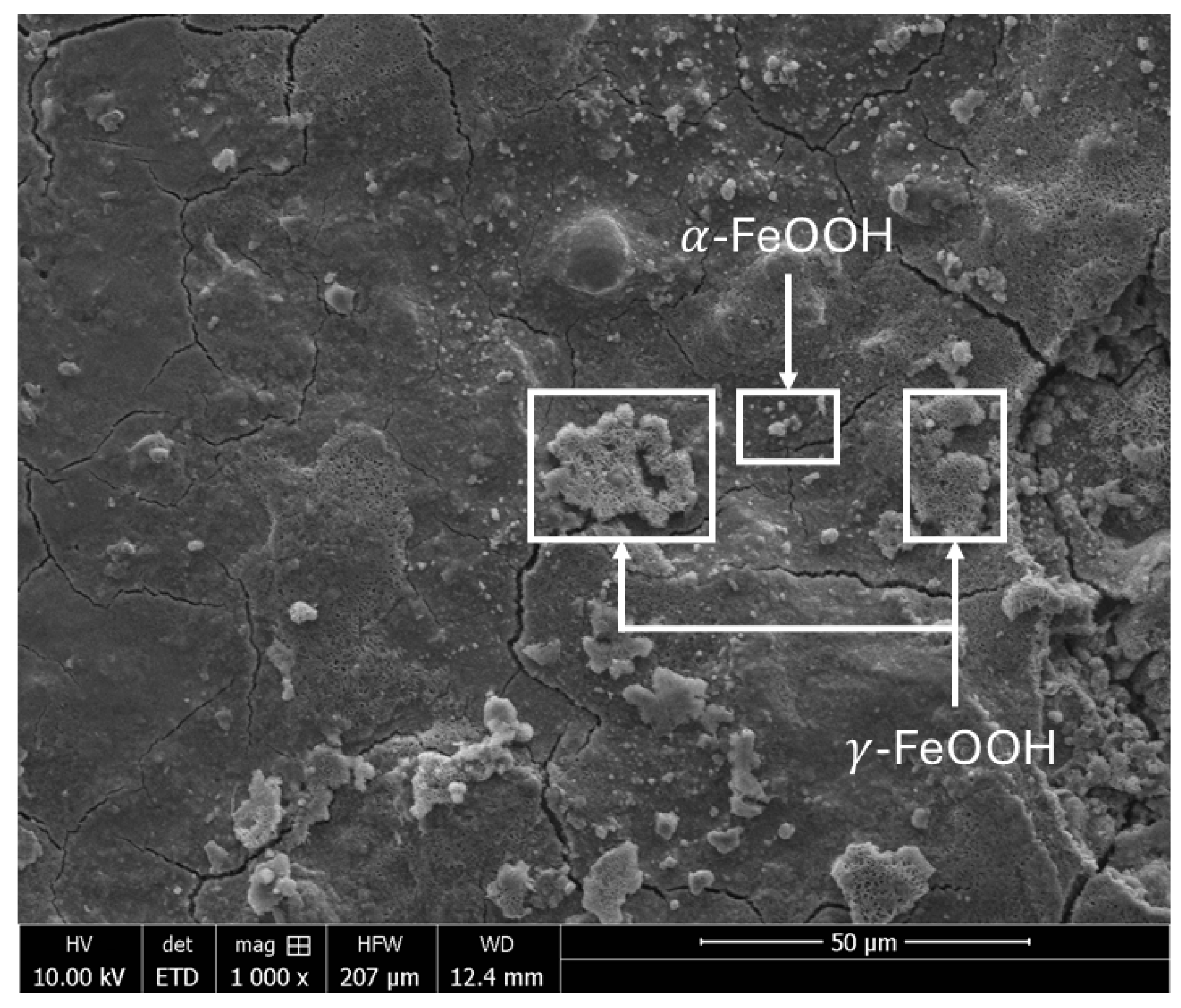

. Yamashita et al. [

15] reported that, at an early corrosion stage, lepidocrocite γ-FeOOH is formed at the surface of the weathering steel, while it dissolves in the inner portion of the rust layer, referred to as the X-ray amorphous substance layer. Over time, this layer forms a stable protective rust layer containing stable and packed Cr-FG, known as the protective patina layer. This protective layer impedes the diffusion of elements, limiting the penetration of aggressive species, and thus reduces their contact with the steel substrate.

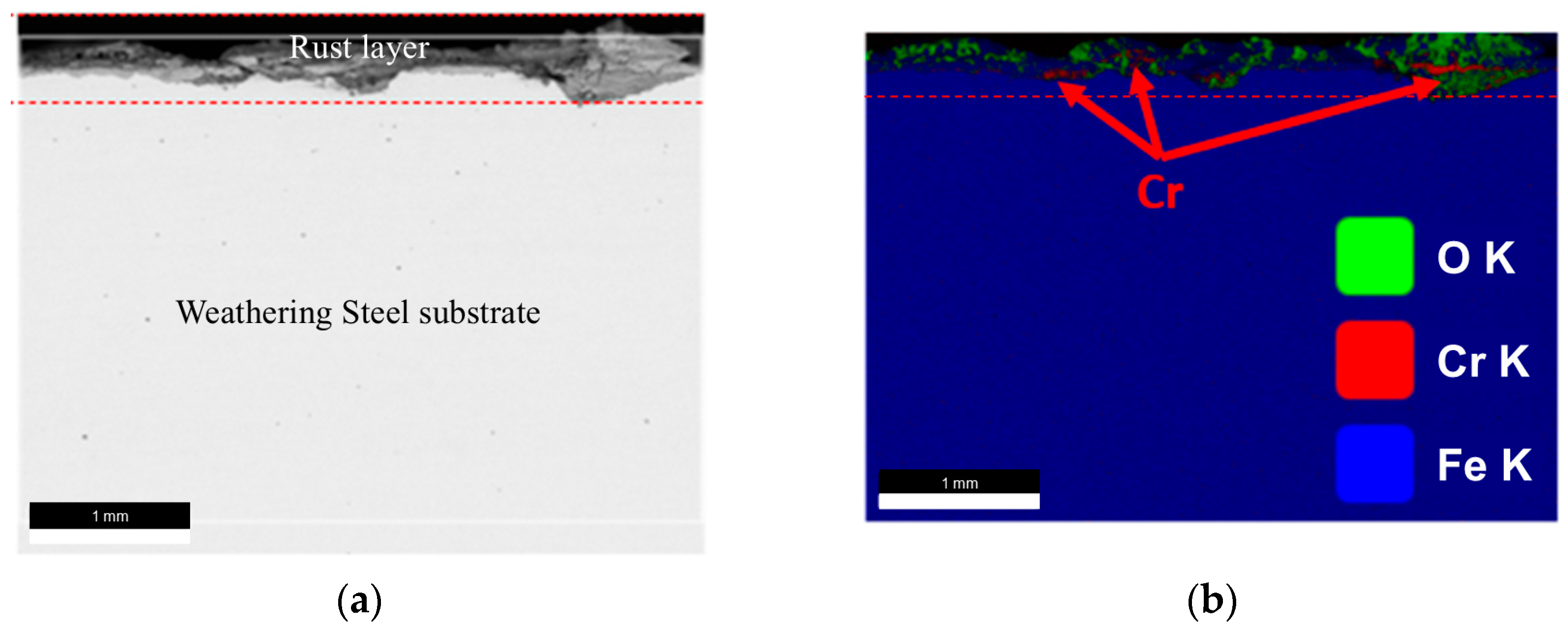

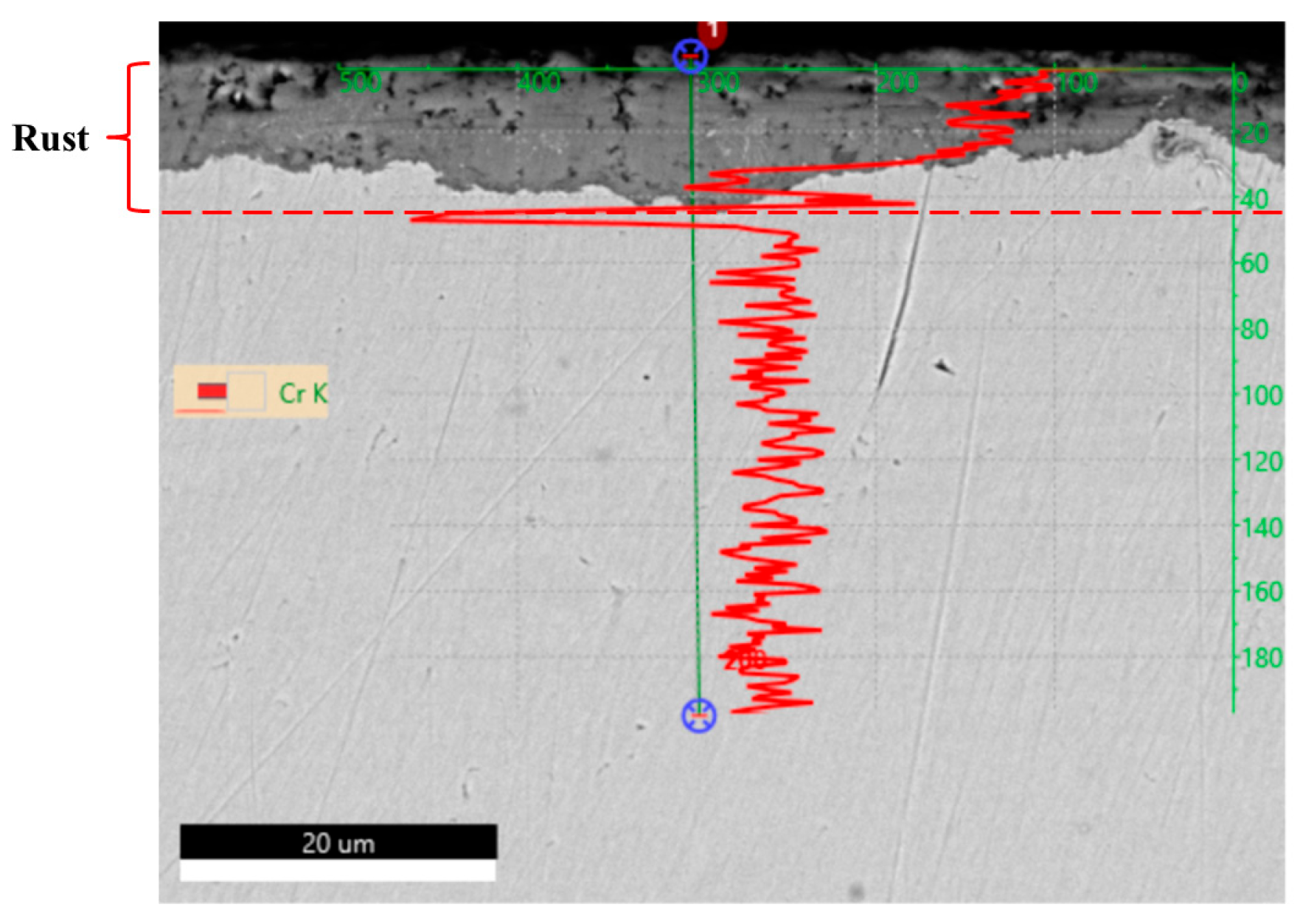

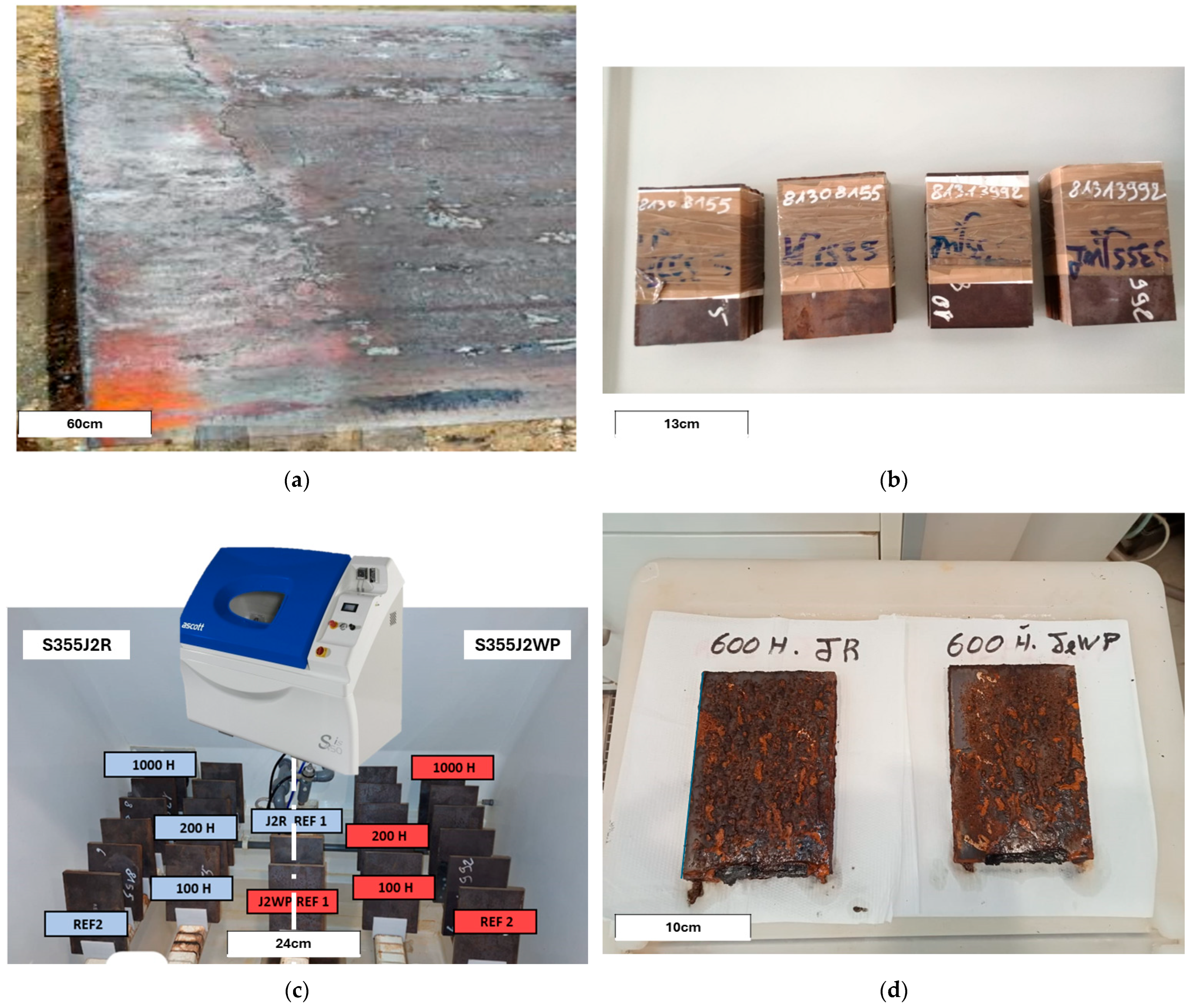

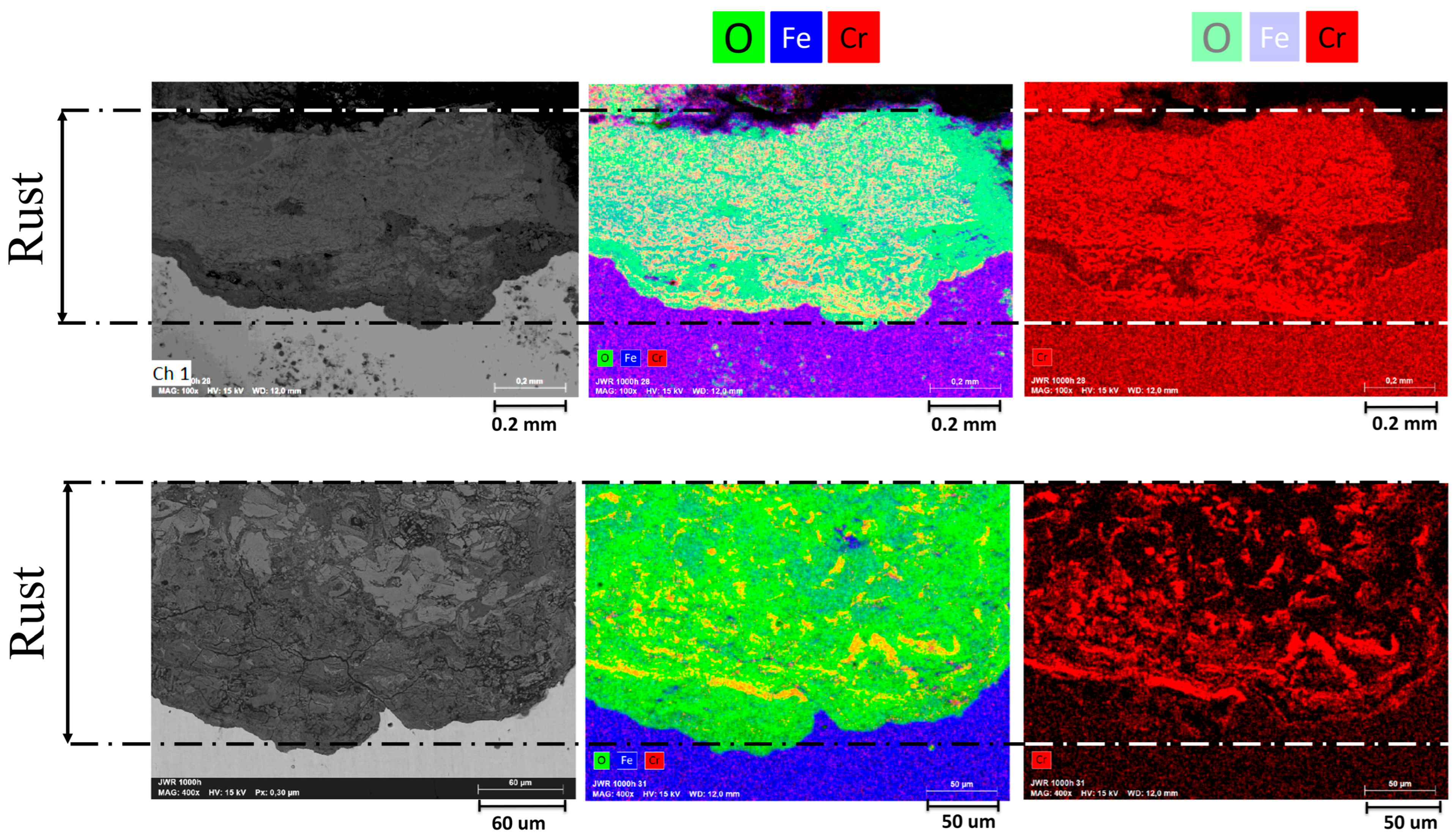

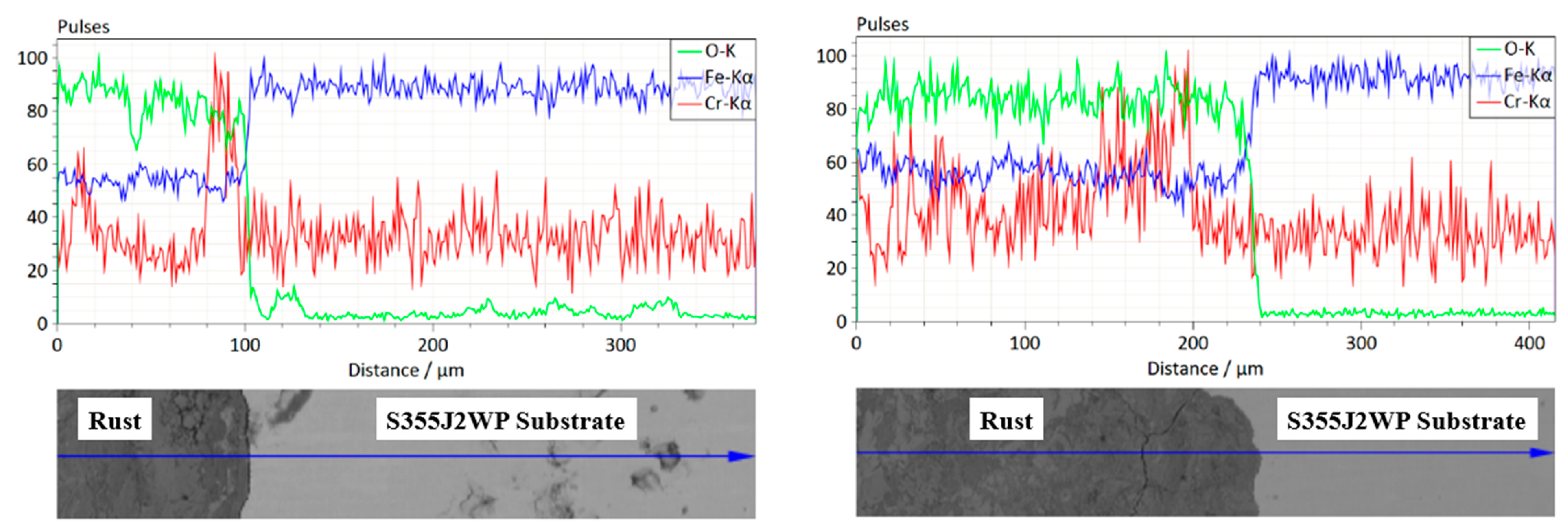

As part of the state-of-the-art assessment, preliminary corrosion observations were performed on a commercially available, normalized S355J2WP weathering steel used in this study as a reference material (See

Table 1 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). This commercial product, not produced within the present work, provides an experimental benchmark representative of the expected corrosion behavior of compliant weathering steel grades. Accelerated salt spray tests conducted for up to 1000 h in accordance with the ASTM B117-19/ISO 9227:2022 standard [

18,

19], combined with cross-sectional Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analyses, were used to qualitatively assess the morphology and elemental distribution within the corrosion product layer. These preliminary observations, presented here to motivate the experimental and modeling approach adopted in this study, are consistent with trends previously reported in the literature [

14,

15].

Table 1.

Weathering steel ranges in wt.% according to EN 10025-5 standards (Adapted form Refs. [

20,

21]).

| | C | Mn | Si | Al | P | S | Nb | Cr | Cu |

|---|

| S355J0W | Min | - | 0.50 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| Max | 0.16 | 1.50 | 0.50 | - | 0.035 | 0.035 | - | 0.80 | 0.55 |

| S355J2W | Min | - | 0.50 | - | 0.02 | - | - | 0.015 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| Max | 0.16 | 1.50 | 0.50 | - | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.060 | 0.80 | 0.55 |

| S355J0WP | Min | - | - | - | - | 0.060 | - | - | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Max | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.75 | - | 0.150 | 0.035 | - | 1.25 | 0.55 |

| S355J2WP | Min | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.060 | - | 0.015 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Max | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.75 | - | 0.150 | 0.030 | 0.060 | 1.25 | 0.55 |

In agreement with trends reported in the literature [

14,

15,

16], these state-of-the art preliminary observations (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) indicate, as expected, chromium concentration enrichment within the patina, particularly near the substrate–rust interface, a feature commonly associated with the formation and long-term stability of a protective corrosion layer. These initial data serve to define target compositional ranges and corrosion performance expectations for the modeling and validation strategy developed in this work. To reach such expectations, one can agree that the chemistry of targeted weathering steels, displayed in

Table 1 with respect to the EN 10025-5 standard, ref. [

20] is crucial, where the Cr, P, and Cu wt.% are within the ranges 0.3–1.25, 0.06–0.15, and 0.25–0.55, respectively.

In this context, the present work provides a proof of concept for the application of a Fab-to-Lab-to-Fab modeling and validation strategy to upgrade a conventional steel grade already under industrial production. Using the Thermo-Calc

® Process Metallurgy Module coupled with the TCOX11 database and an EERZ-based kinetic framework [

10,

22,

23], the approach starts from industrial-scale data acquisition to reproduce in silico the LF refining conditions of the reference S355J2R steel grade. This industrial baseline is then used to optimize LF refining schedules in silico, enabling the controlled design of deoxidation, desulfurization, and alloying sequences for the production of both S355J2W and S355J2WP steel grades. In particular, two tap-to-tap LF schedules were developed through targeted additions of Fe–Cr- and Fe–P-ferroalloys and subsequently validated at the industrial scale through the production of a total of 261.87 tonnes of steel via two distinct metallurgical routes. Finally, the resulting steels were assessed by accelerated salt spray exposure for 1000 h in accordance with the ASTM B117/ISO 9227 standard, allowing a qualitative correlation between refining process design and corrosion performance, benchmarked against preliminary observations obtained on a commercial, normalized S355J2WP weathering steel.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the above-mentioned Fab-to-Lab-to-Fab strategy, the LF refining schedules investigated in this study were simulated using the Thermo-Calc

® Process Metallurgy Module (PMM) along with the CALPHAD-based slag oxide database TCOX11 (version 2022a) [

10,

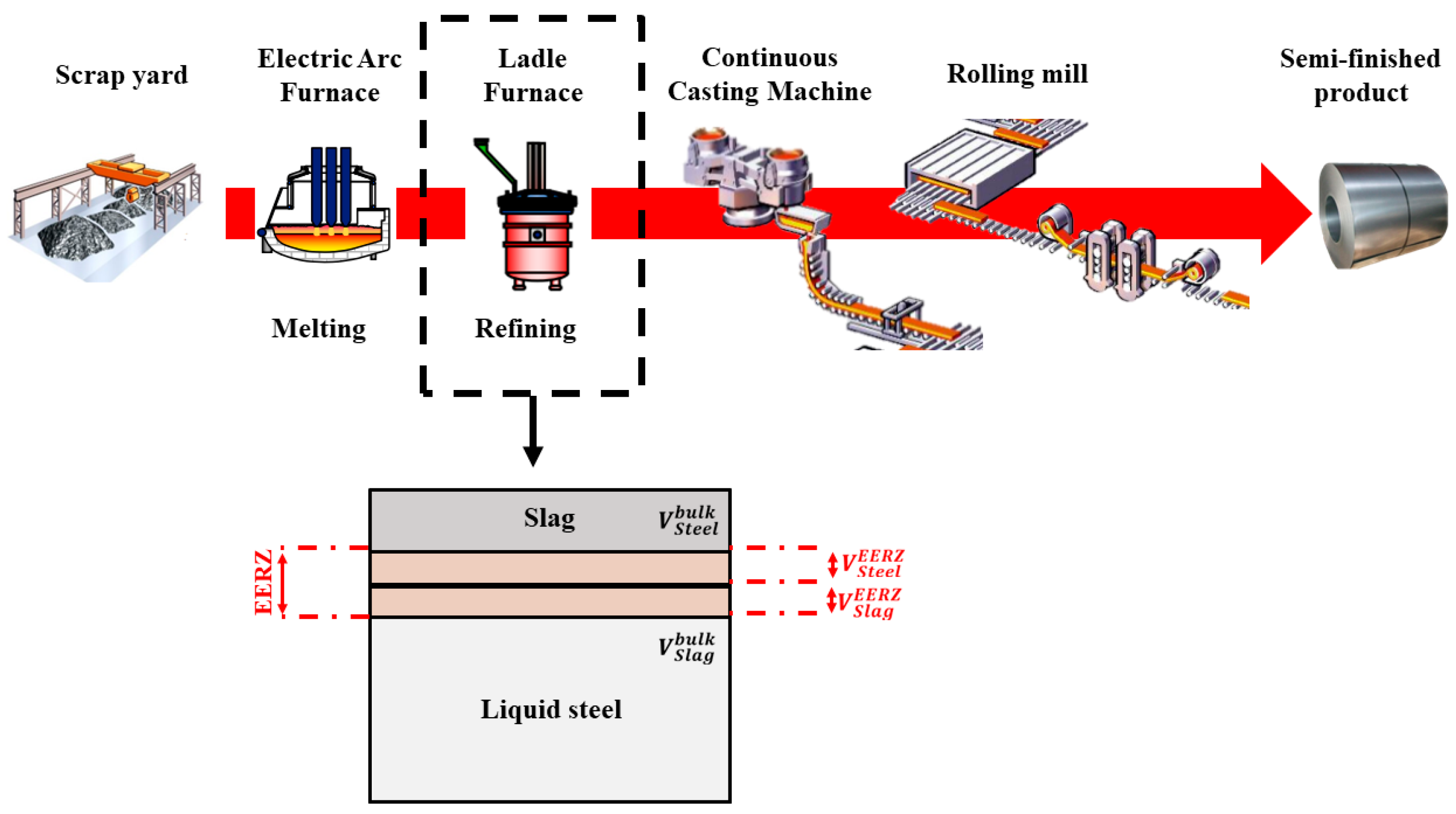

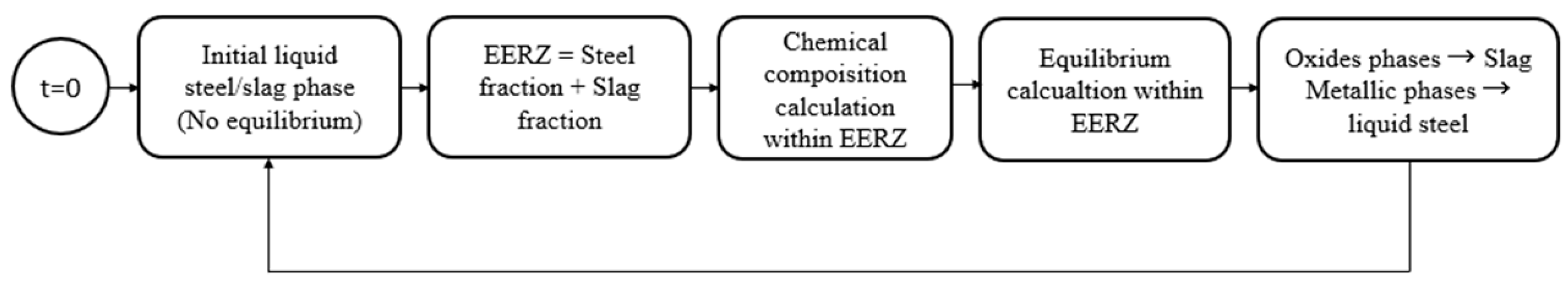

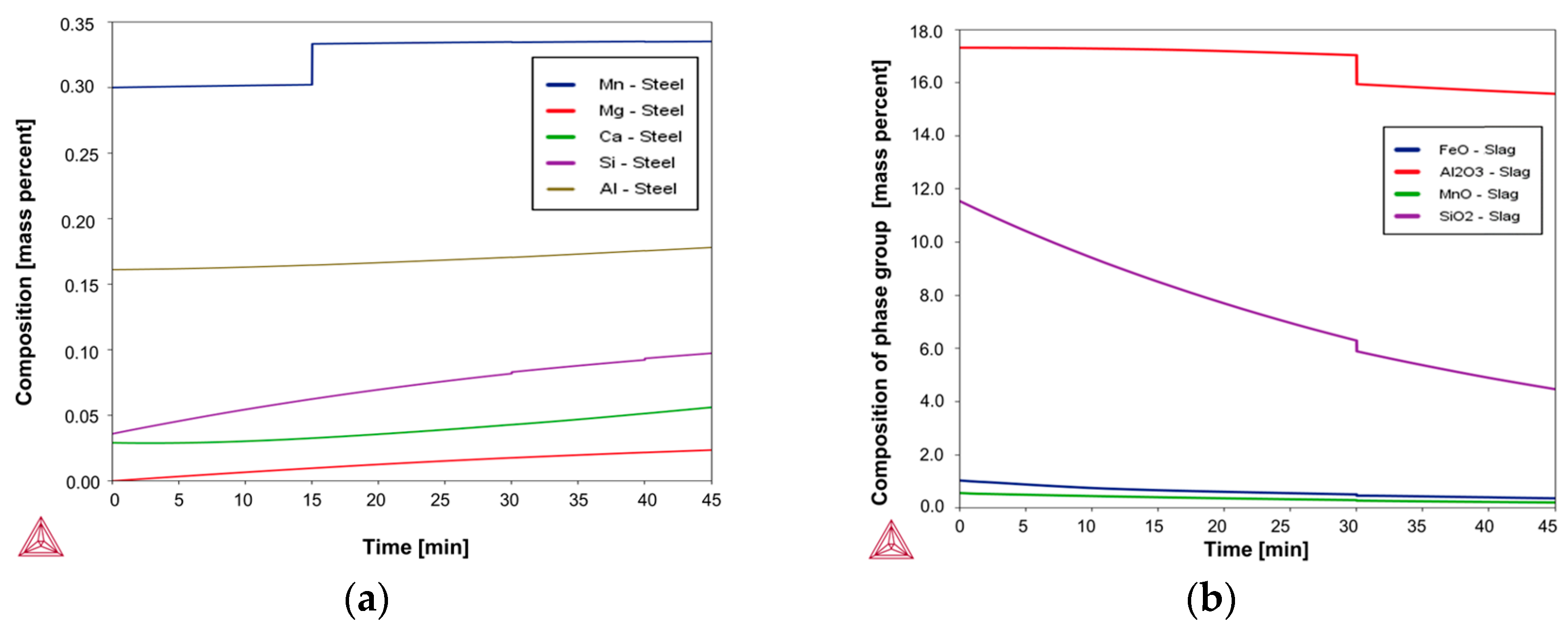

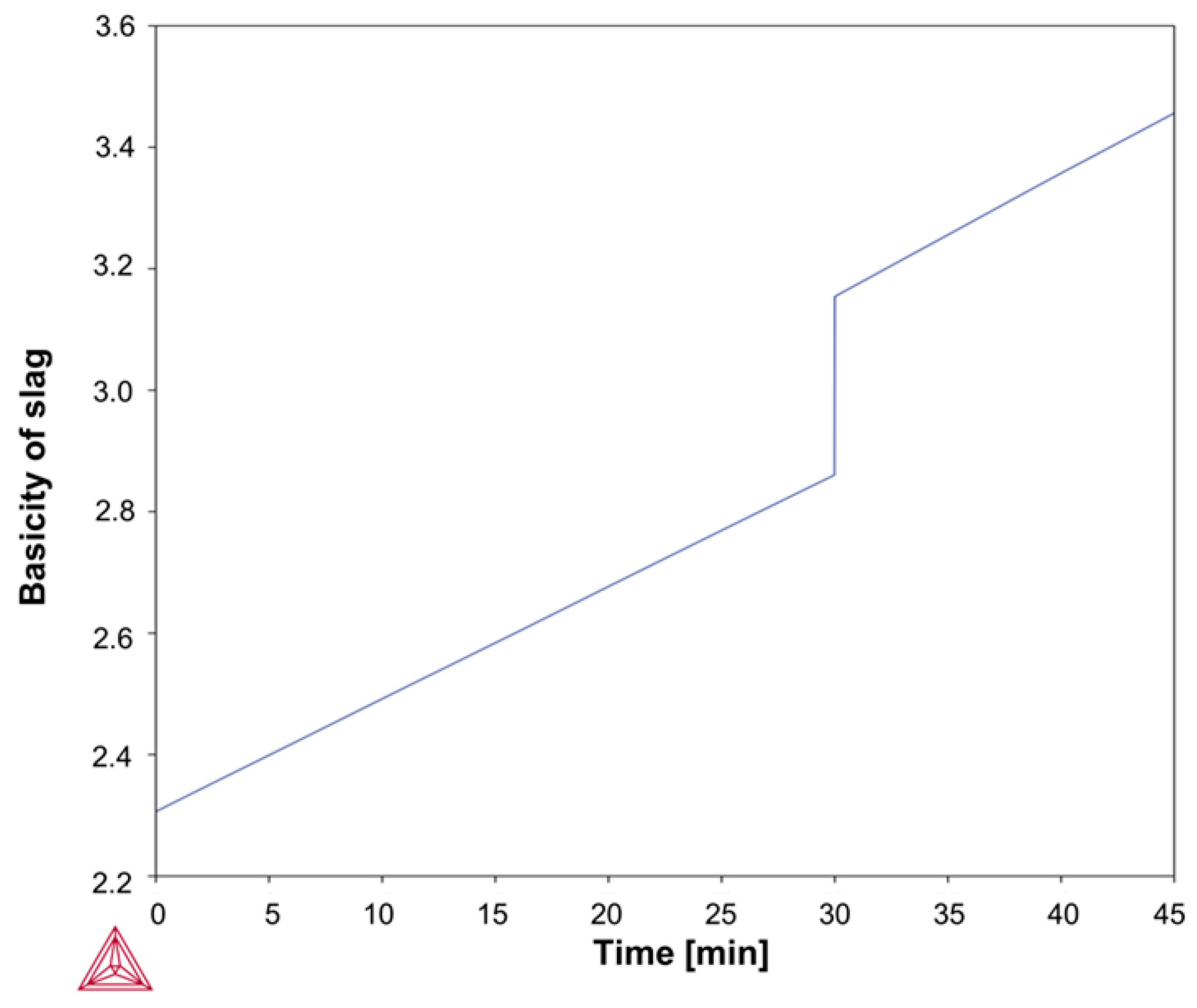

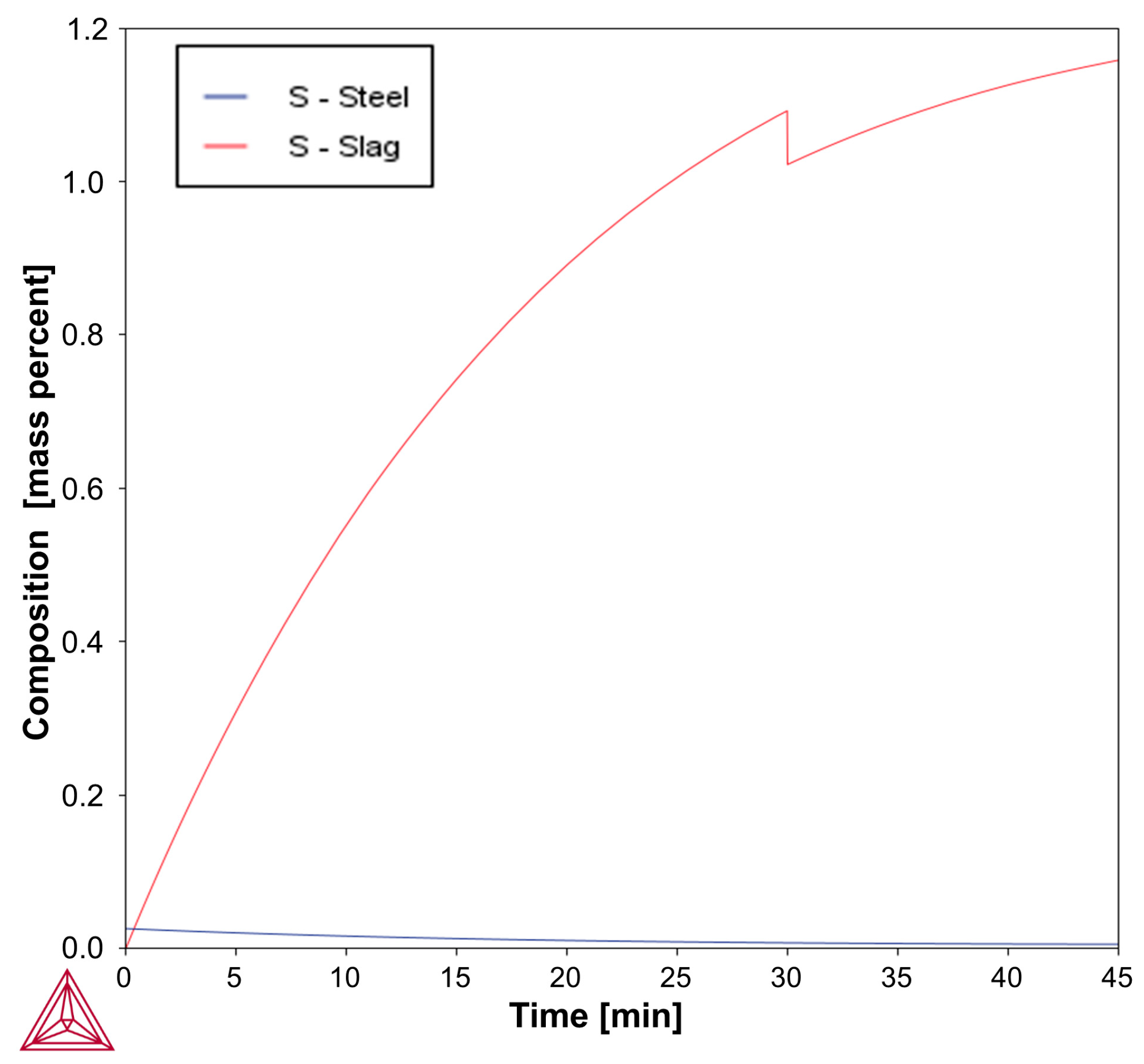

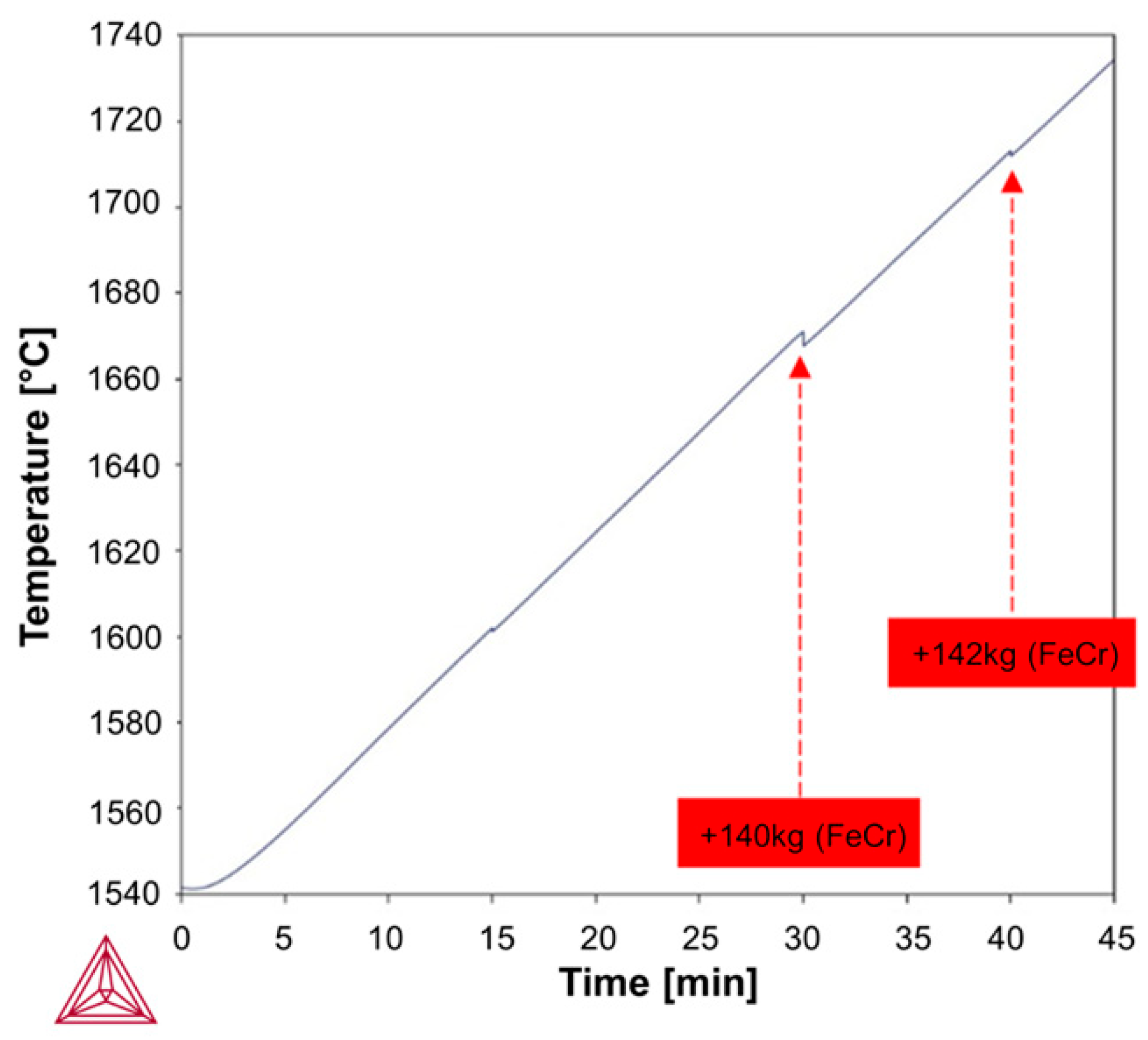

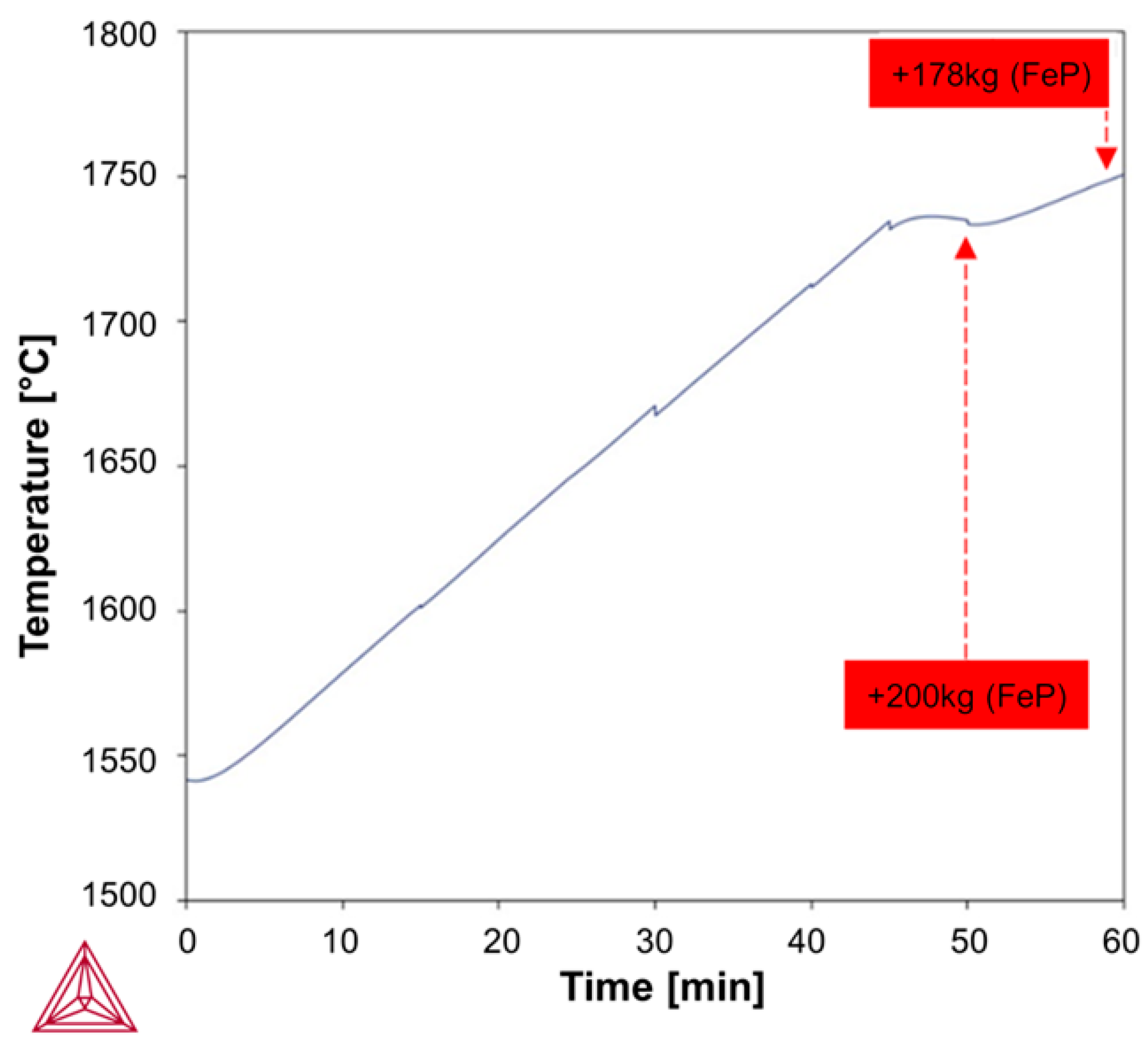

11]. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, simulations were performed under kinetically constrained process conditions by applying an iterative EERZ approach at the liquid steel–slag interface, allowing the prediction of both transient and final process parameters under constant total pressure. To first reproduce the industrial fabrication of the reference S355J2R steel grade, industrial-scale and literature data were used as inputs to the model. These inputs included the composition and mass of all added materials, the sequence and timing of process additions, and a set of kinetic parameters governing mass transfer phenomena during refining [

10,

11].

Within the EERZ framework, slag–metal reactions are assumed to occur within an effective interfacial reaction volume. At the liquid steel–slag interface, reaction kinetics are controlled by coupled mass and heat transfer balances driven by compositional and thermal gradients. The sizes of the effective reaction volumes in the steel and slag phases, denoted as

and

are defined by the rates of mass transport to and from the interface, with higher mass transfer coefficients resulting in larger EERZ volumes and faster reaction kinetics, as sketched in

Figure 3. When ferroalloys are added, the PMM assumes complete melting of the additions and a homogeneous temperature distribution within the liquid steel bulk at each simulation time step, consistent with industrial ladle furnace operating conditions [

11]. The overall simulation proceeds through an iterative time-stepping procedure in which thermodynamic equilibrium calculations within the EERZ are coupled with kinetic mass transfer updates, as presented in

Figure 4.

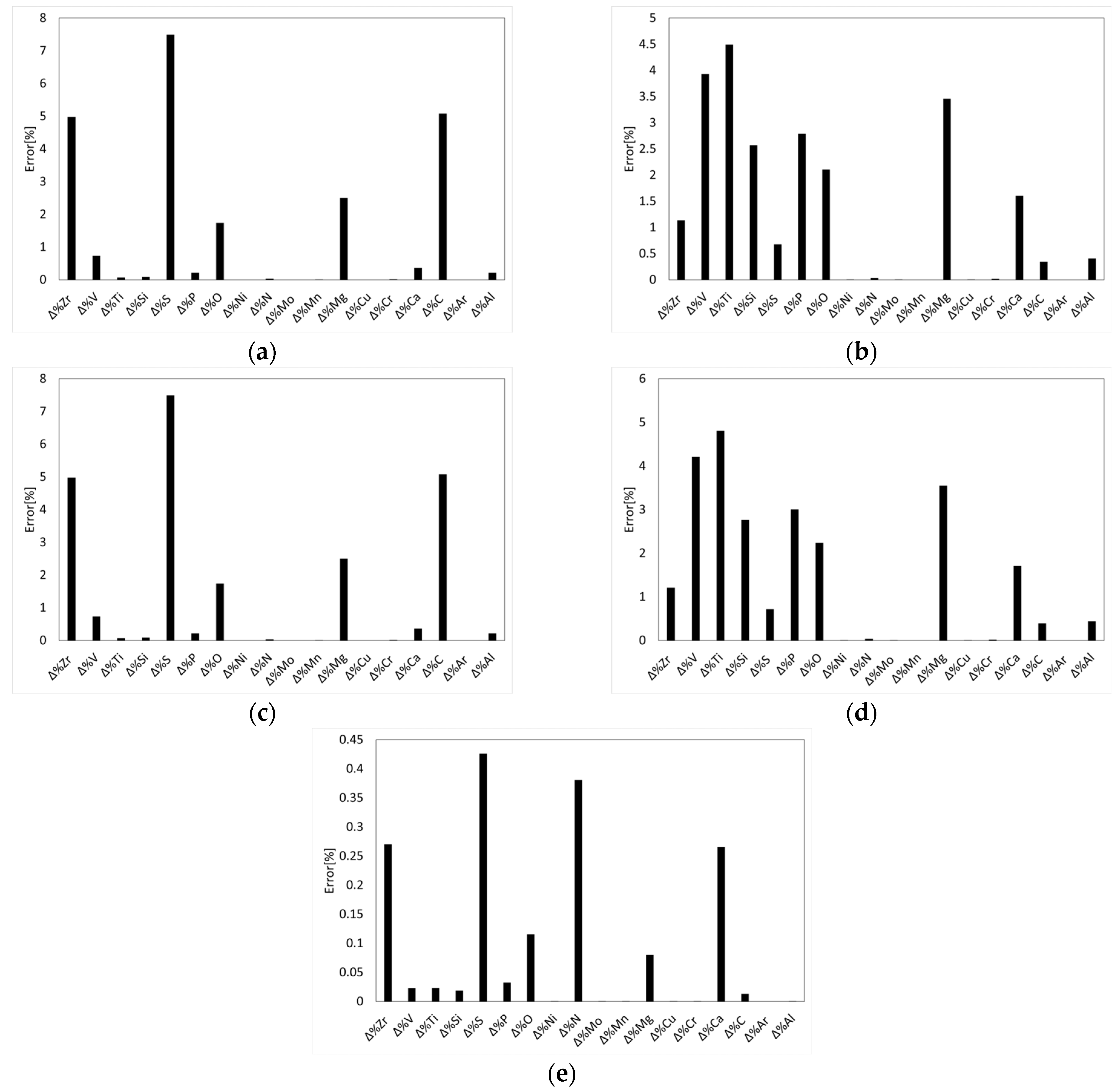

To assess the sensitivity of LF schedule predictions using Thermo-Calc

®, the performance of the PMM was evaluated by quantifying the impact of input parameter uncertainties on the predicted liquid steel composition. Accordingly, a series of simulations was performed by applying a ±10% deviation to each input variable, as summarized in

Table 2. This approach is consistent with common industrial practices for uncertainty analysis and allows the identification of the most influential kinetic parameters while evaluating the robustness of the PMM in accommodating such deviations. Then, two LF refining schedules were simulated, following the initial deoxidation and desulfurization steps performed at the tapping stage, to upgrade the reference S355J2R steel grade to (i) S355J2W through the addition of Fe-Cr and (ii) S355J2WP through the combined addition of Fe-Cr and Fe-P, to produce targeted weathering steel grades in compliance with the EN 10025-5 standard. In industrial practice, composition thresholds are defined prior to processing; accordingly, as shown in

Table 3, the S355J2W grade was represented by a target composition denoted S355WT3, while S355WT4–5 was assigned to the S355J2WP grade. Validation of the simulated LF refining schedules was performed through industrial trials. The weathering steel performance of the as -produced S355J2WP was then evaluated using an accelerated salt spray test conducted for 1000 h in an ASCOTT Analytical iS

® chamber (Ascott Analytical, Tamworth, UK), in accordance with the ASTM B117/ISO 9227 standard (

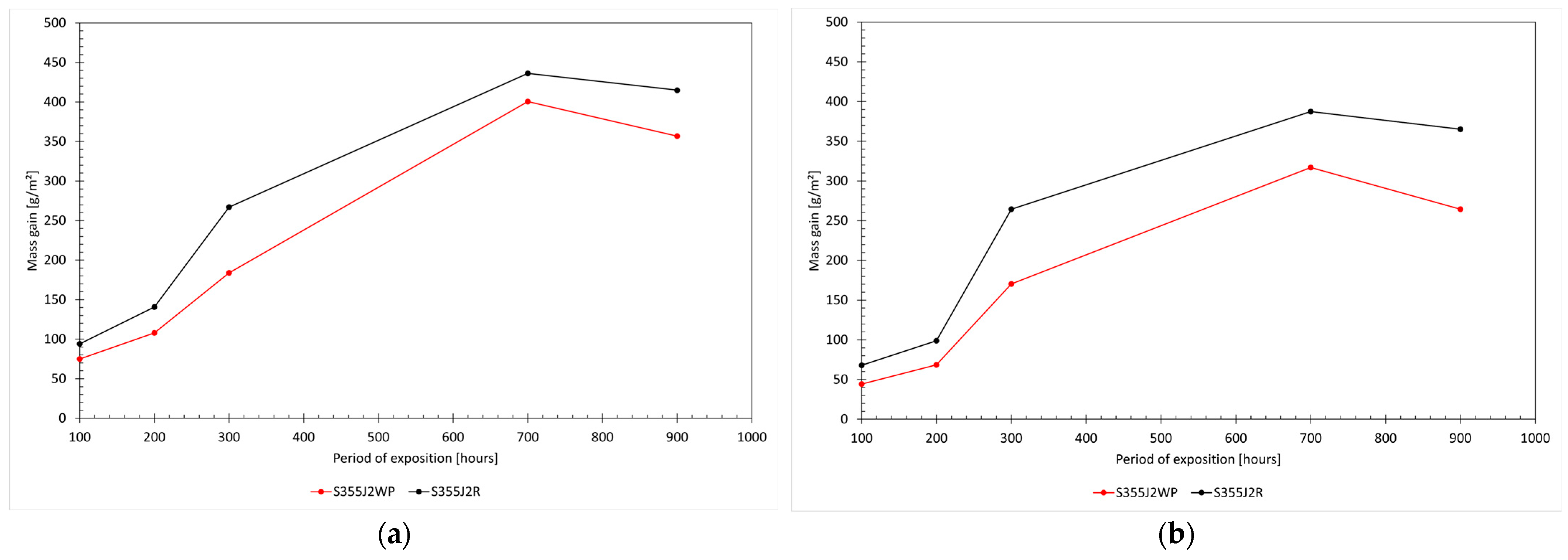

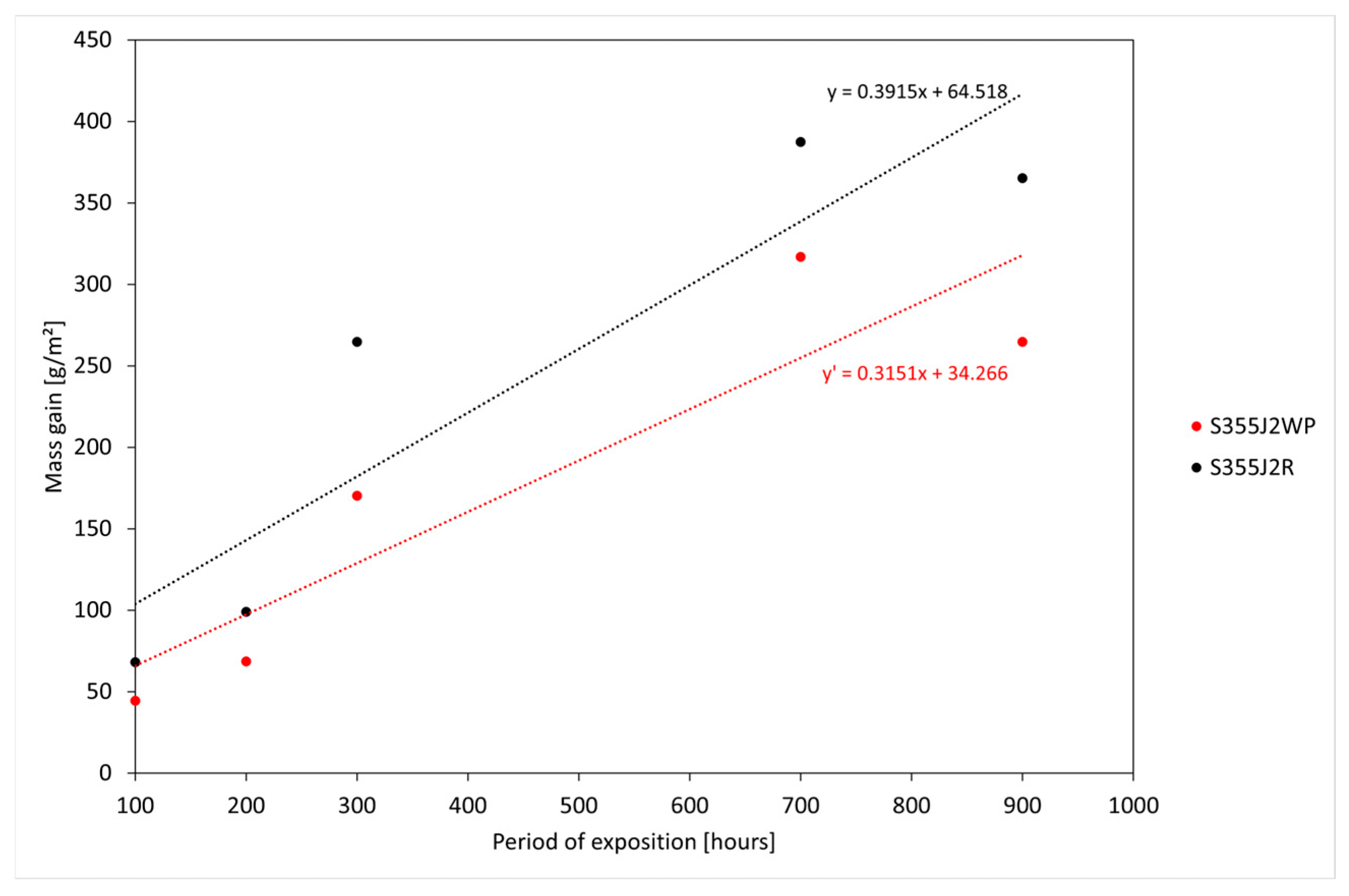

Figure 5). The microstructural and chemical changes associated with corrosion product formation were examined by comparing steel plates before and after exposure to the accelerated corrosion test using a Zeiss EVO10

® Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a SMART

® Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) detector. Energy calibration was regularly performed using a copper sample, and quantification accuracy was checked with a certified quality control testing block. The chemical composition of the plates was measured using a calibrated S3 MiniLab 300 Spark Optical Emission Spectrometer (GNR France by metal instruments, Marnay, Haute Saône, France). In addition, mass gain as a function of exposure time was quantified for both steel grades. Samples were weighed at 100 h intervals throughout the test duration. For each measurement, the mass was recorded immediately after removal from the test chamber and again after cleaning by brushing with distilled water, in accordance with ASTM B117-19/ISO 9227:2022 procedures. The mass gain

[g/m

2] was calculated according to Equation (1):

where

is the mass gain [g/m

2];

and

are the initial mass and mass after exposition, respectively (g); and

, w, and

e are the length, width, and thickness of the sample, respectively.

In addition, the relative corrosion rate,

, was calculated according to Equation (2):

where

and

are the slopes of the fitted lines of mass measurements of the produced S355J2WP(MS) samples and S355J2R samples, respectively.