Picolinoyl N4-Phenylthiosemicarbazide-Modified ZnAl and ZnAlCe Layered Double Hydroxide Conversion Films on Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel for Enhancing Corrosion Protection in Saline Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

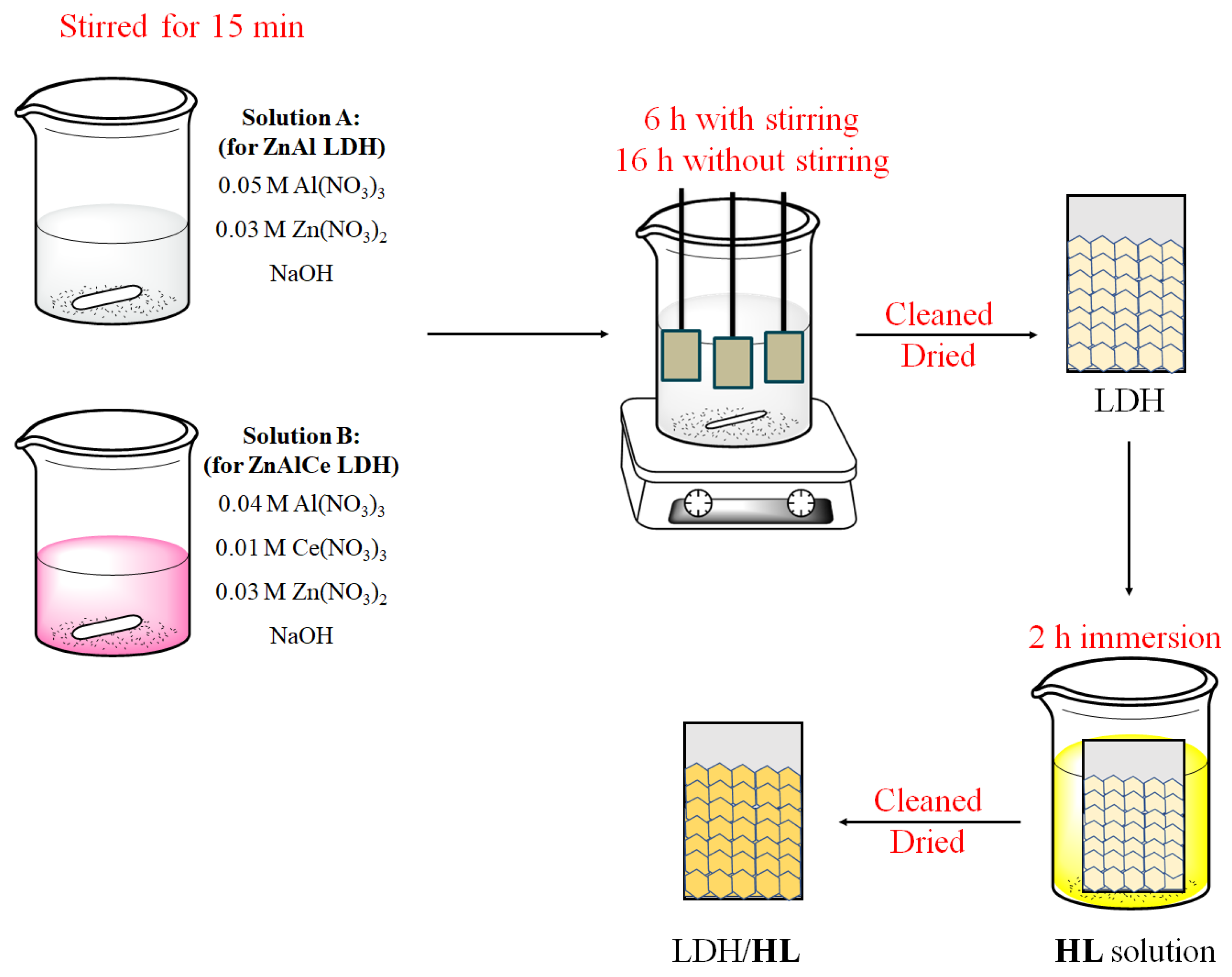

2.2. LDHs Conversion Layer Preparation

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Tests

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of LDH Conversion Layers

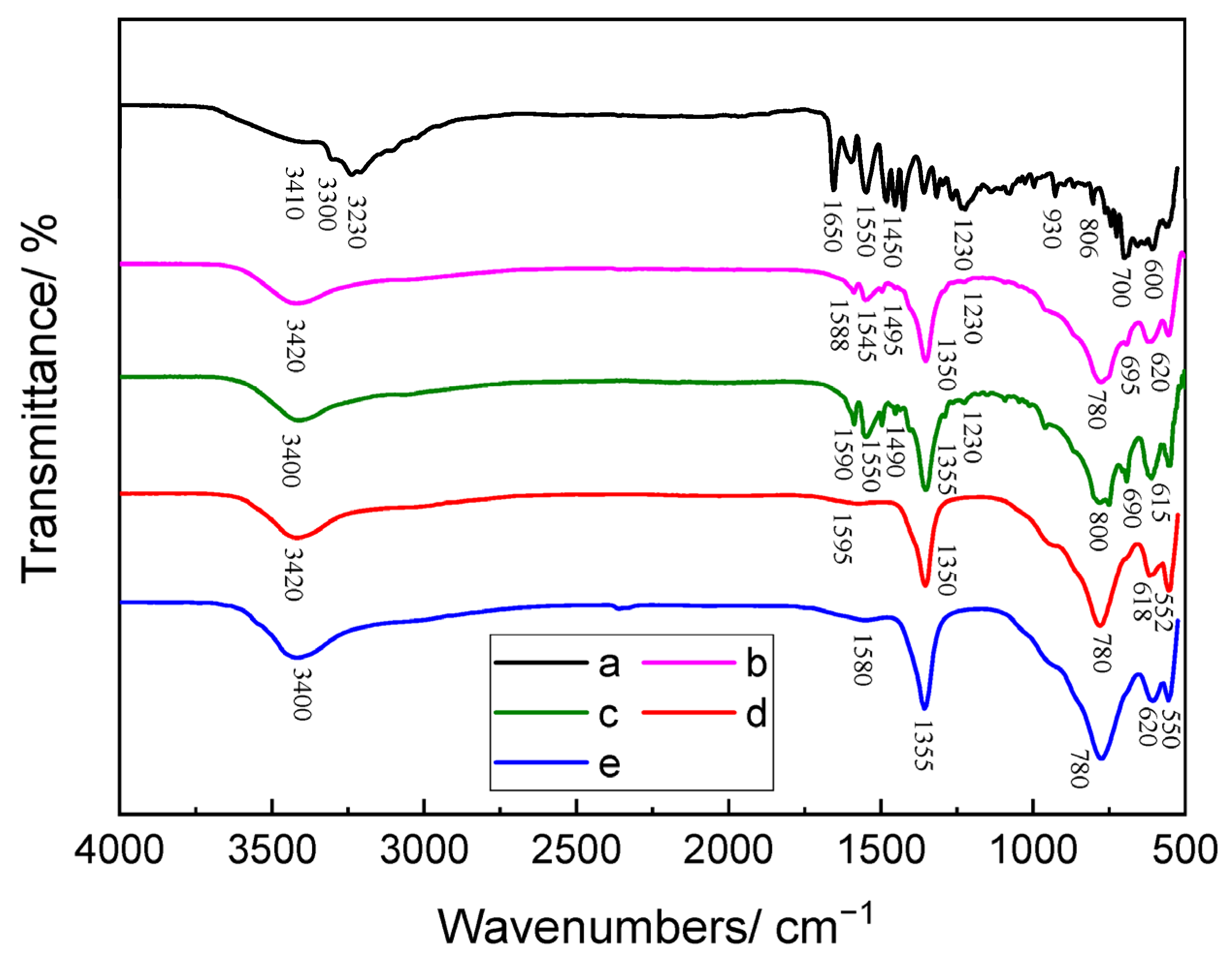

3.1.1. FT-IR Results

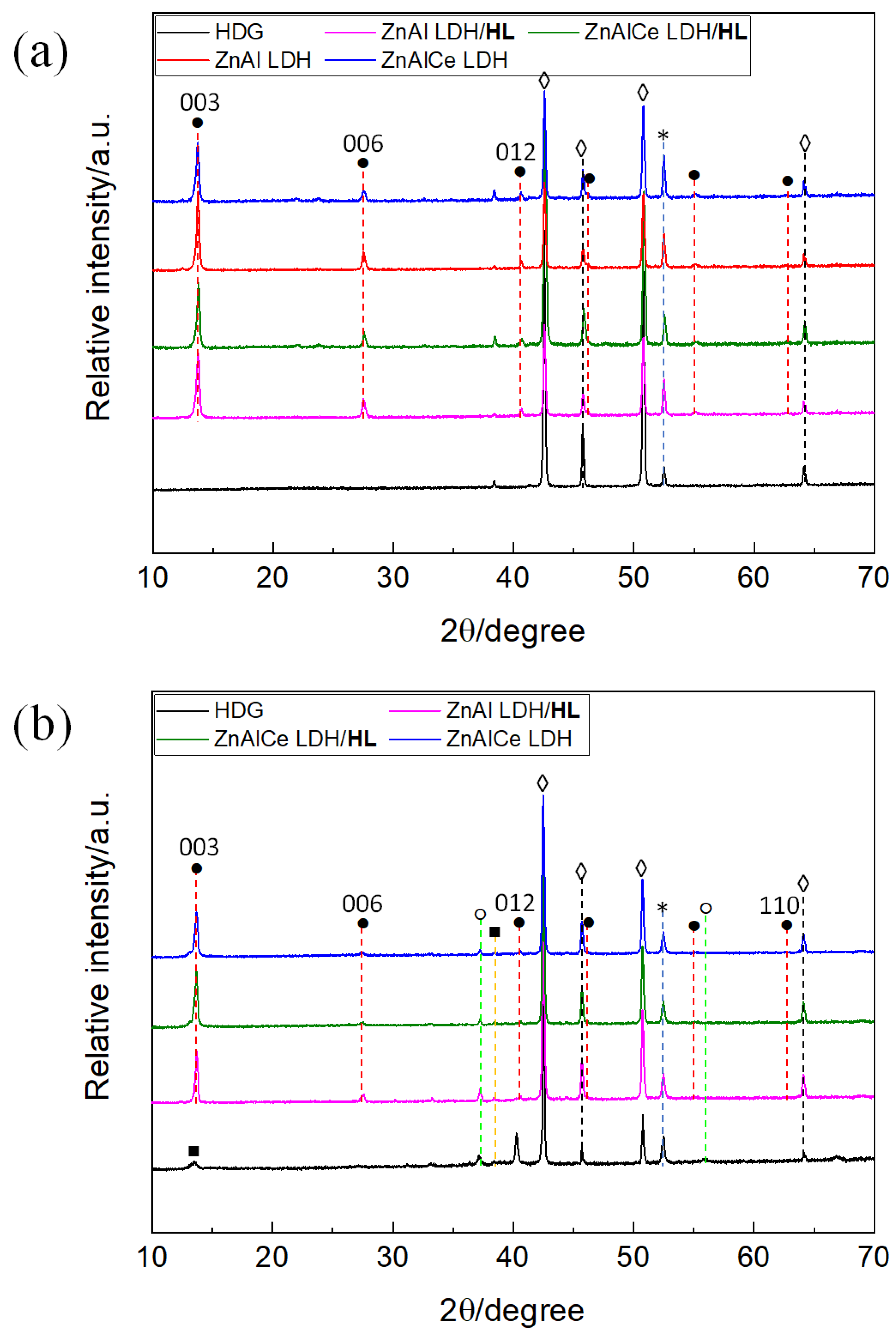

3.1.2. XRD Results

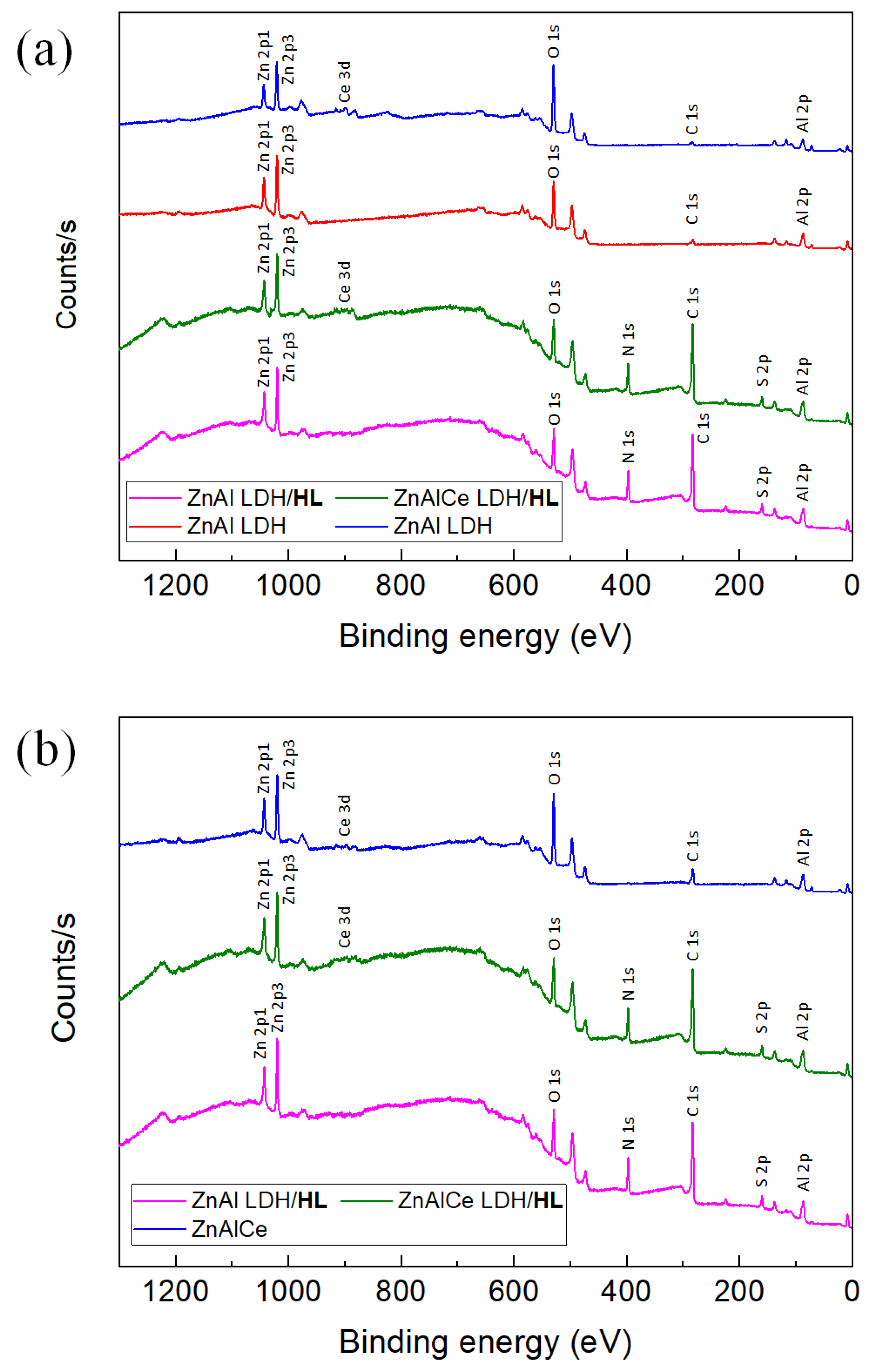

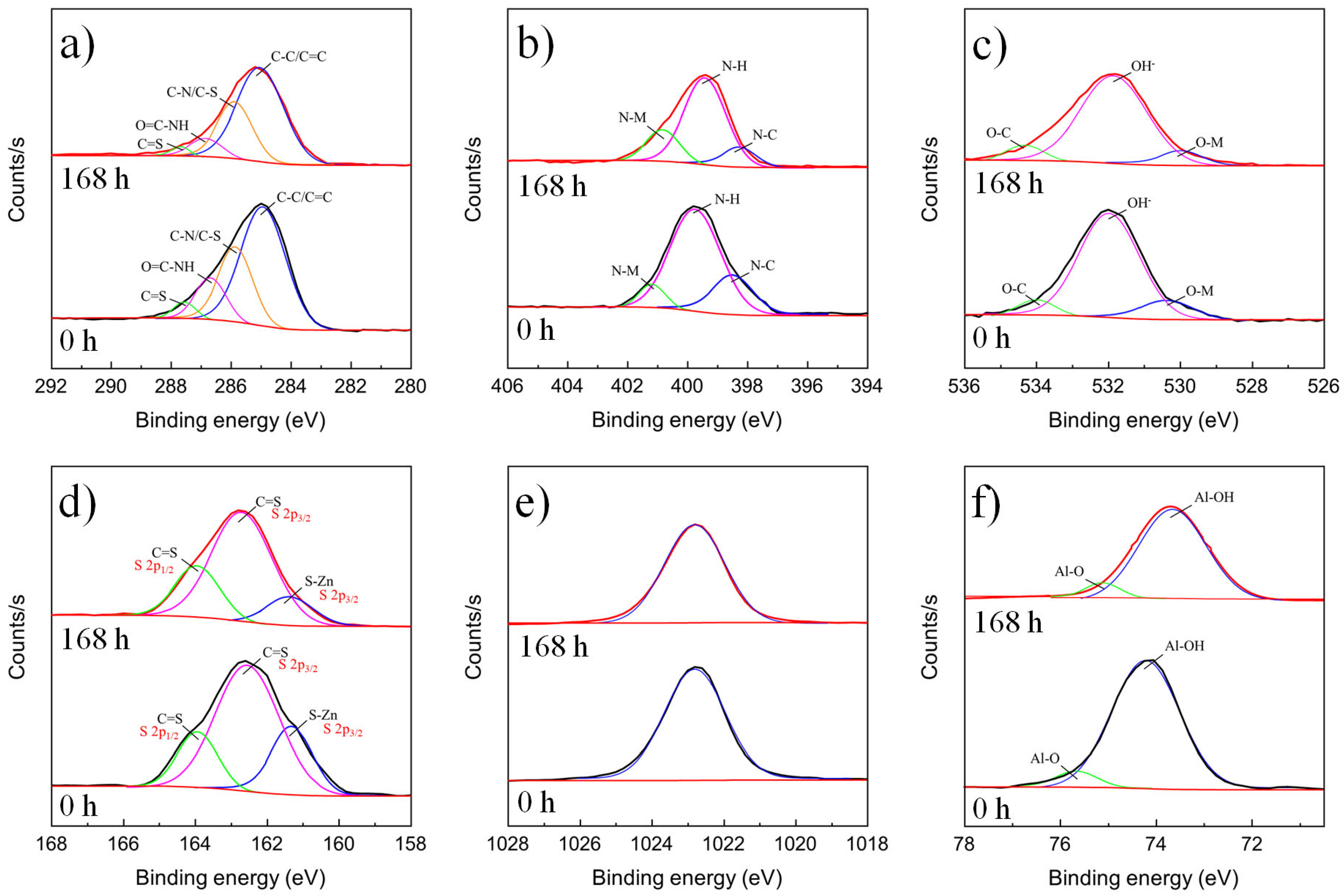

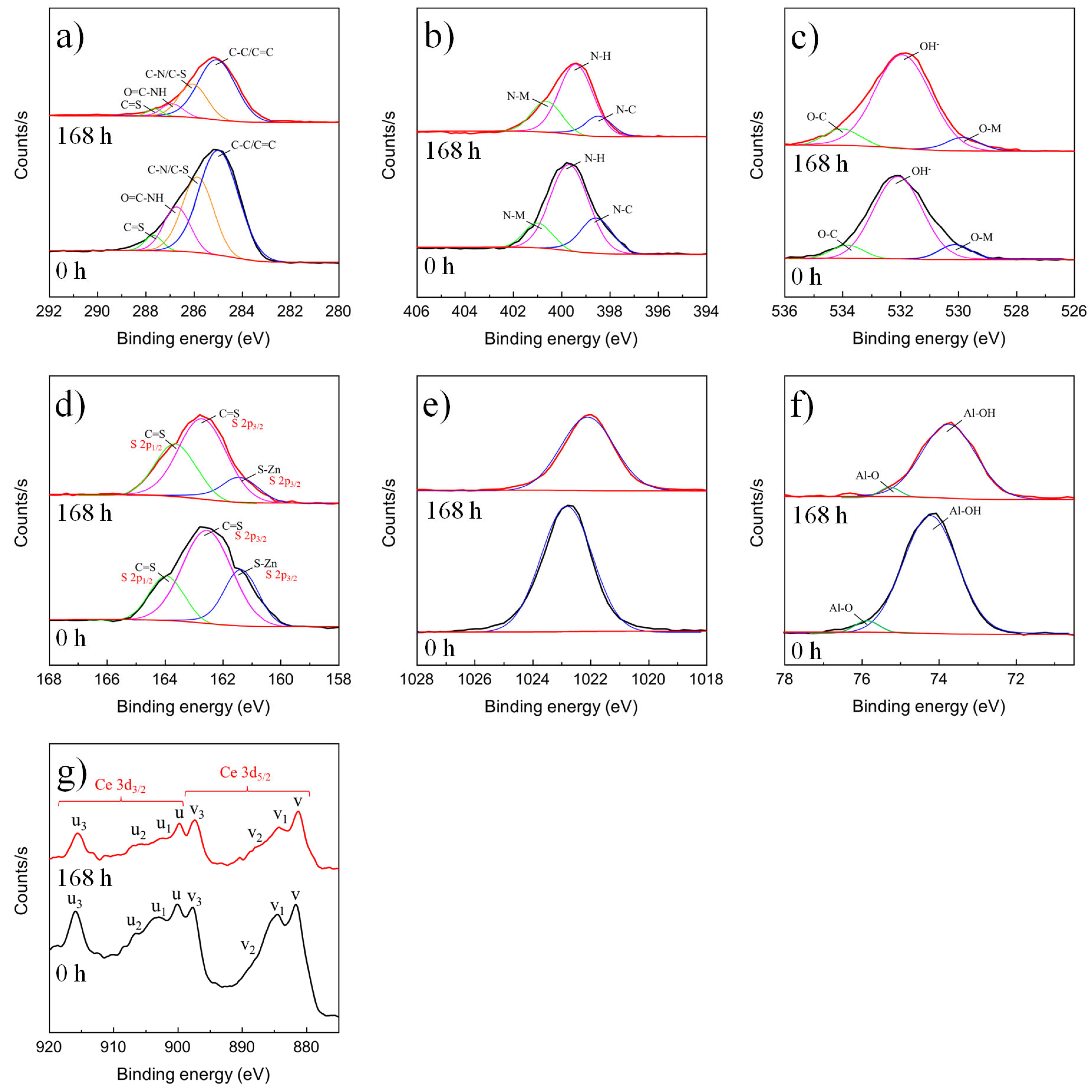

3.1.3. XPS Results

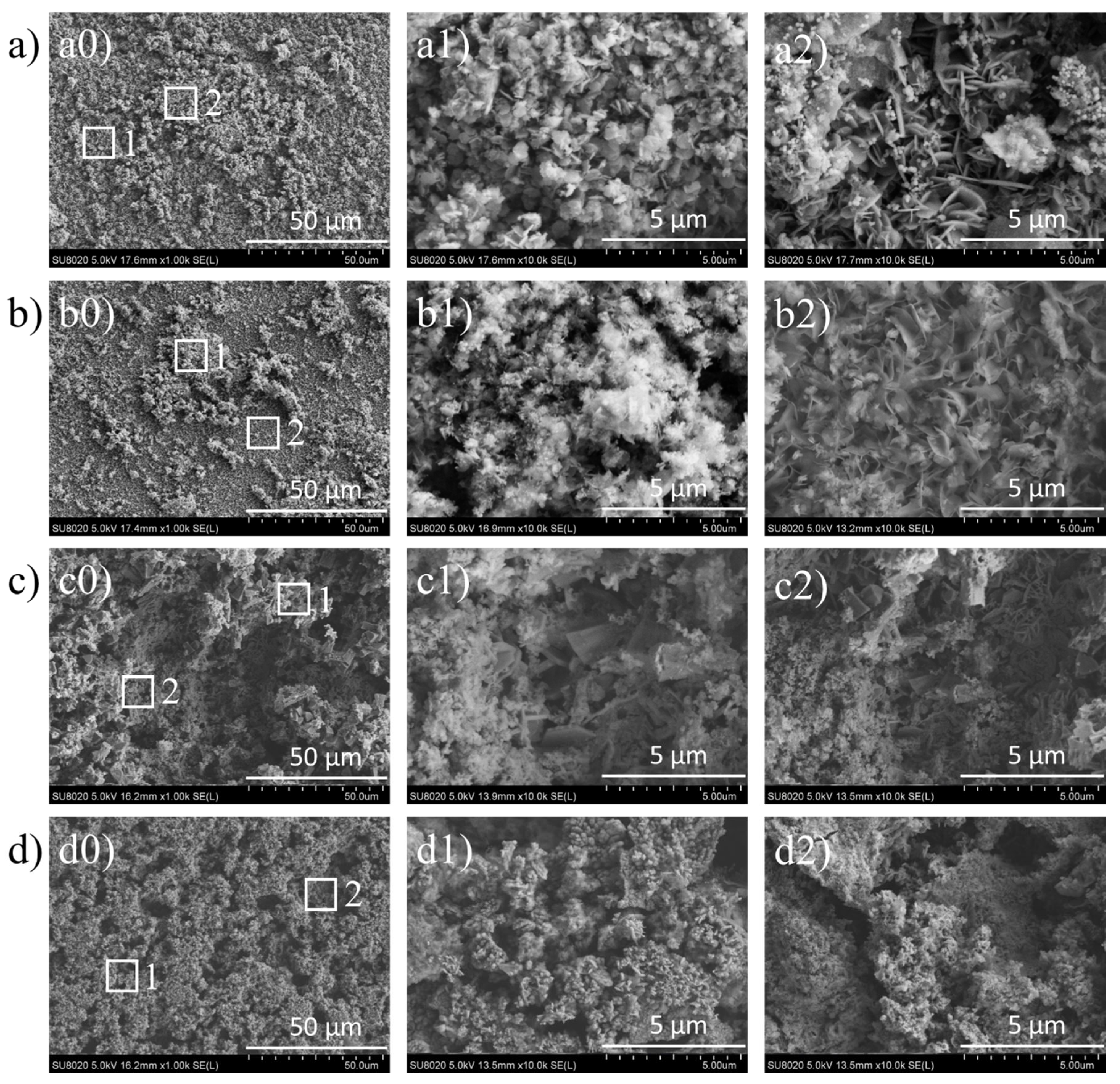

3.1.4. FE-SEM/EDS Results

3.2. Corrosion Protection of LDH Layers

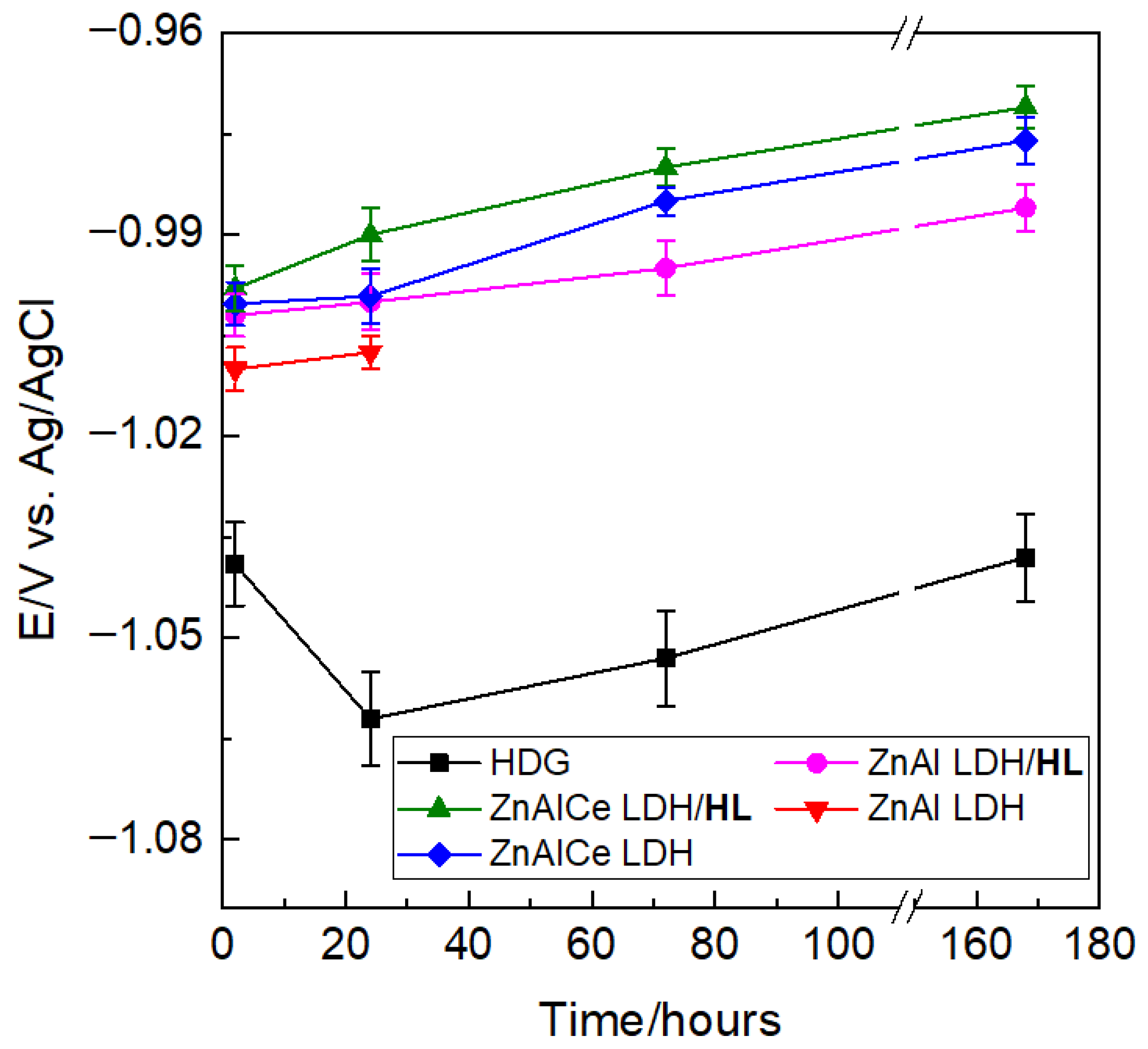

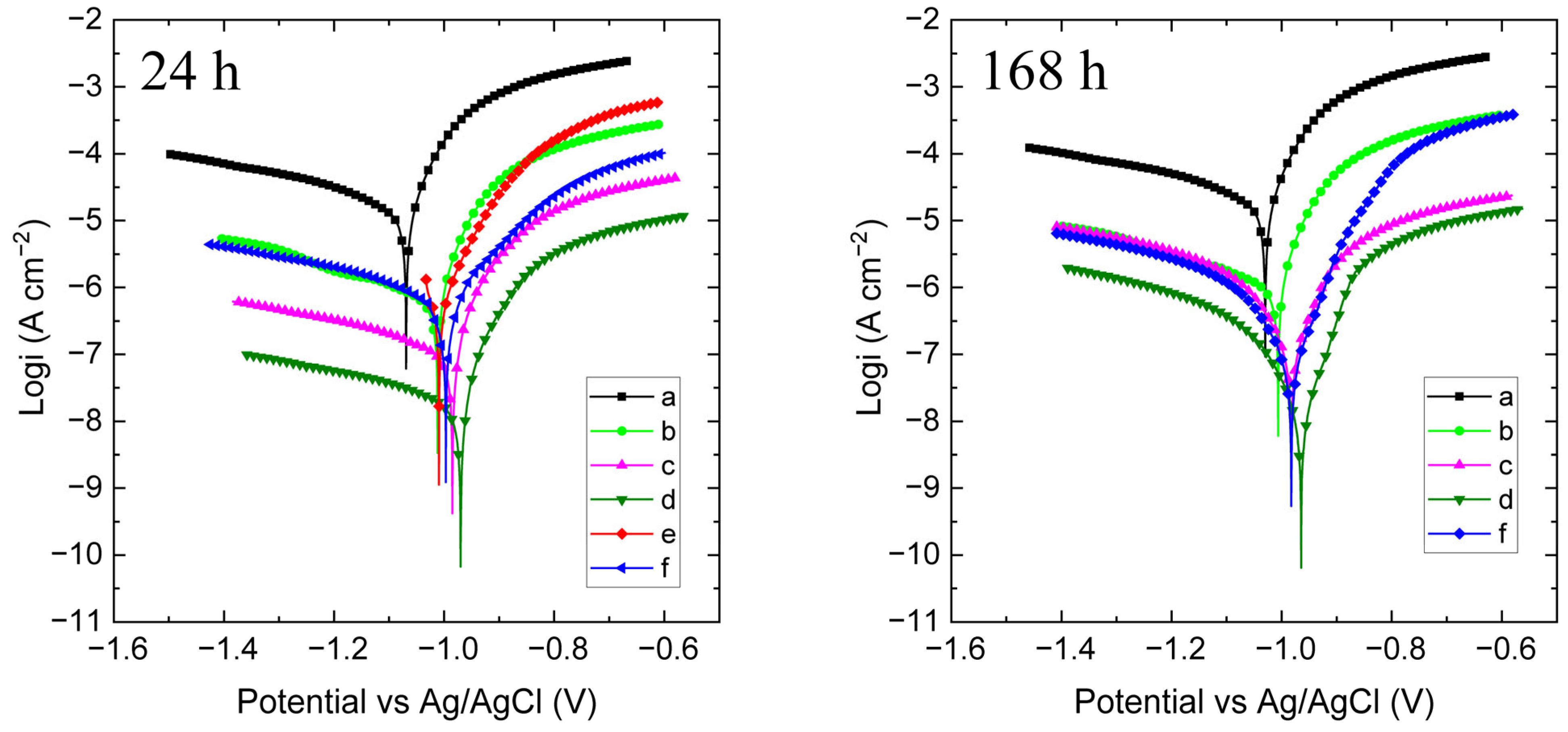

3.2.1. OCP Monitoring and Polarization Curves

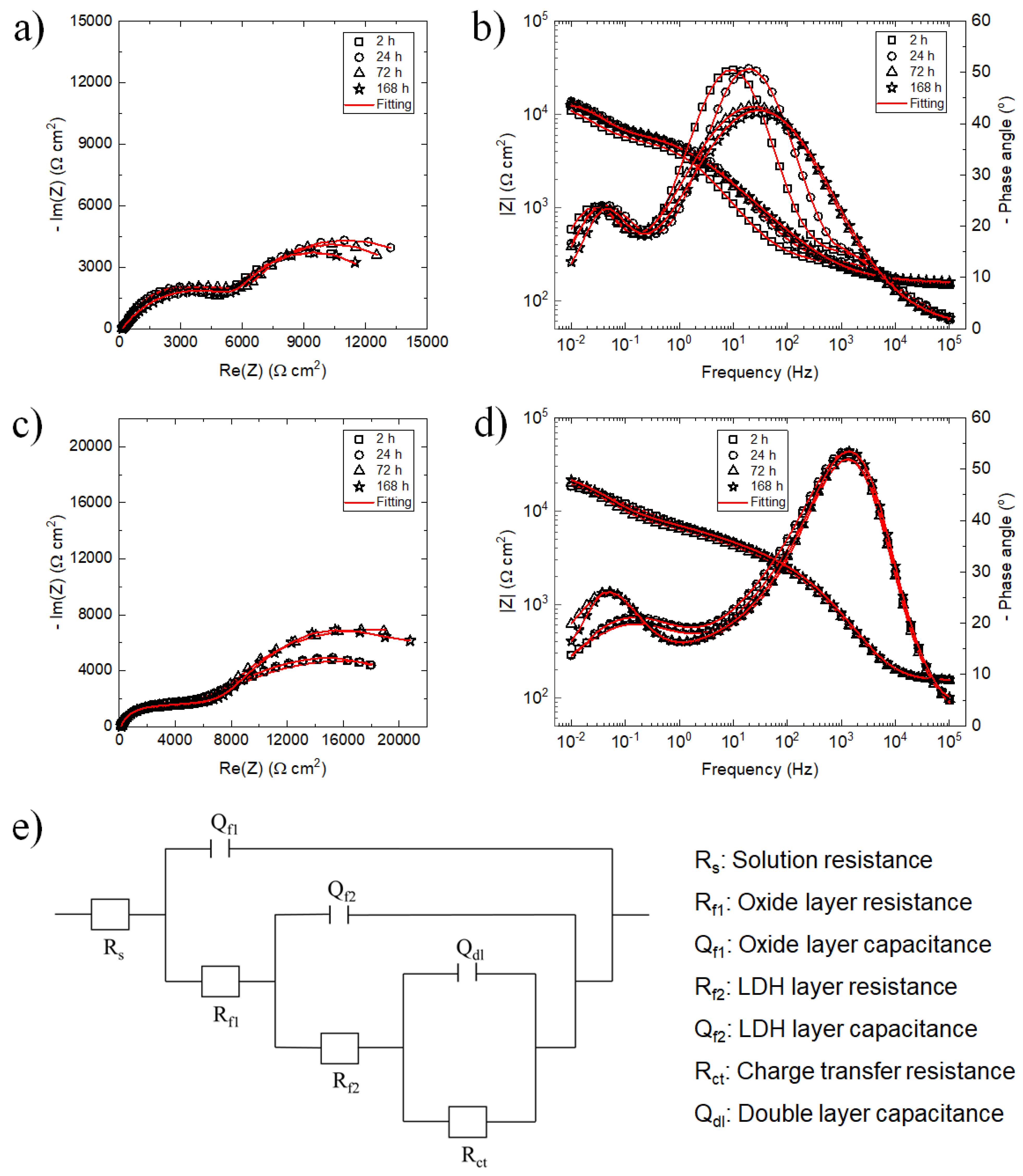

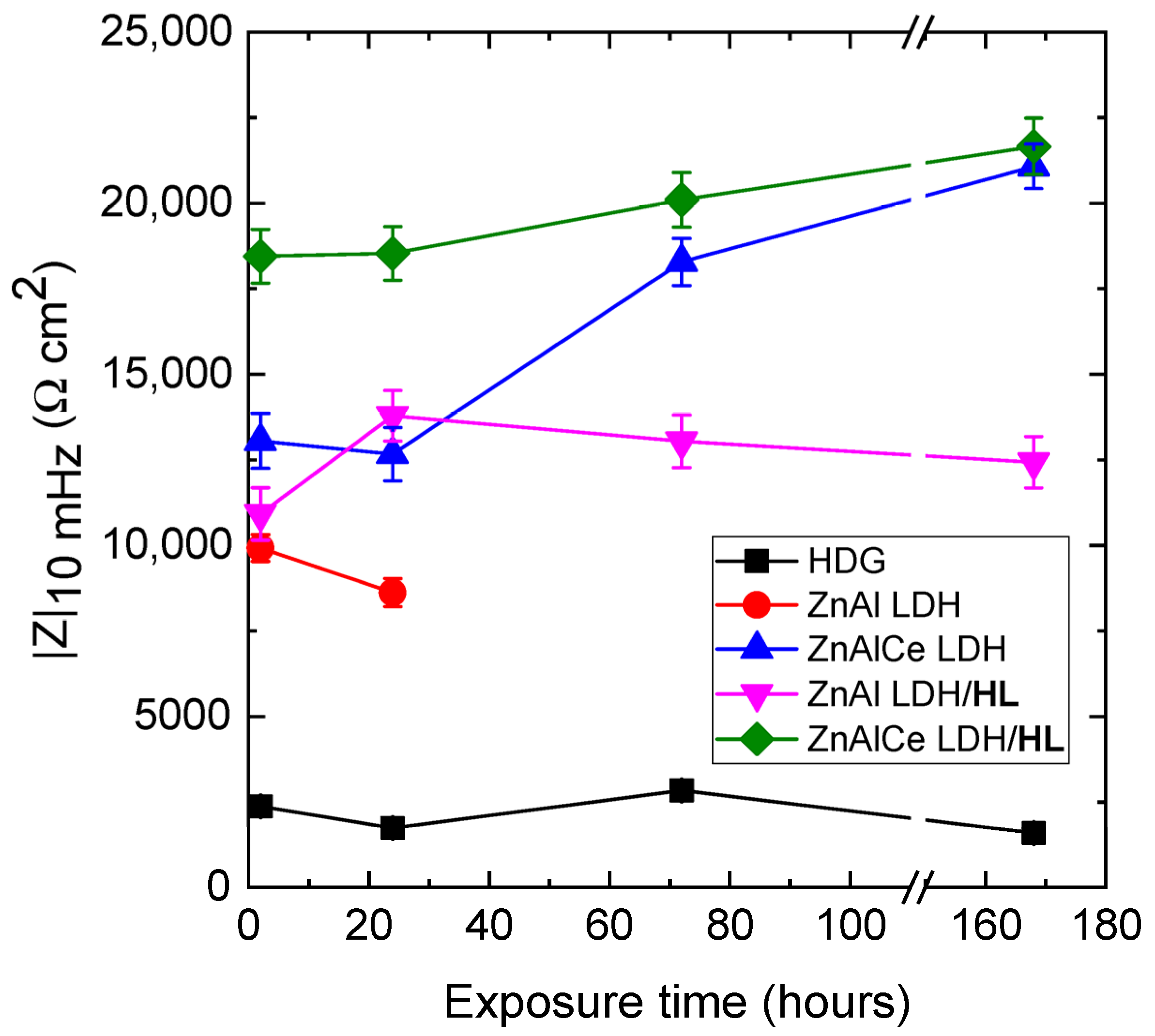

3.2.2. Electrochemical Investigations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, S.; Xie, S.-K.; Xiao, F.; Lu, J.-T. Corrosion behavior of spangle on a batch hot-dip galvanized Zn-0.05Al-0.2Sb coating in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 163, 108237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedel, M.; Poelman, M.; Olivier, M.; Deflorian, F. Sebacic acid as corrosion inhibitor for hot-dip galvanized (HDG) steel in 0.1 M NaCl. Surf. Interface Anal. 2019, 51, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, A.S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Gonon, M.; Belfiore, A.; Paint, Y.; To, T.X.H.; Olivier, M.G. Role of Al and Mg alloying elements on corrosion behavior of zinc alloy-coated steel substrates in 0.1 M NaCl solution. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sloof, W.; Hovestad, A.; Van Westing, E.; Terryn, H.; De Wit, J. Characterization of chromate conversion coatings on zinc using XPS and SKPFM. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 197, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomachuk, C.R.; Elsner, C.I.; Di Sarli, A.R.; Ferraz, O.B. Morphology and corrosion resistance of Cr(III)-based conversion treatments for electrogalvanized steel. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2009, 7, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanian, S.; Naderi, R.; Mahdavian, M. Benzotriazole modified Zn-Al layered double hydroxide conversion coating on galvanized steel for improved corrosion resistance. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 150, 105072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustín-Sáenz, C.; Martín-Ugarte, E.; Jorcin, J.B.; Imbuluzqueta, G.; Santa Coloma, P.; Izagirre-Etxeberria, U. Effect of organic precursor in hybrid sol–gel coatings for corrosion protection and the application on hot dip galvanised steel. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q. Current status, opportunities and challenges in chemical conversion coatings for zinc. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 546, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xiong, Z.; Ma, F.; Wu, Q.; Ying, L.; Wang, G. Long-term corrosion resistance of superhydrophobic Ce-Co-Al LDH composite coatings prepared on the surface of Al alloy. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, W. Review of Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanosheets in Corrosion Mitigation: Recent Developments, Challenges, and Prospects. Materials 2025, 18, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Qian, Y.; Jian, R.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y. Intelligent anti-corrosion coating with multiple protections using active nanocontainers of Zn Al LDH equipped with ZIF-8 encapsulated environment-friendly corrosion inhibitors. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 185, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Tan, H.; Yang, W.; Yue, D.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z.; He, C. Effect of pH on long-term corrosion protection of Zn doped MgAl-LDHs coatings by in situ growth on 5052 aluminum alloy. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 64, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Yu, L.; Hu, J.-M. In-situ Zn-Al layered double hydroxide conversion coatings prepared on galvanized steels by a two-step electrochemical method. Corros. Sci. 2024, 233, 112057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouali, A.C.; Serdechnova, M.; Blawert, C.; Tedim, J.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) as functional materials for the corrosion protection of aluminum alloys: A review. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 21, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Wei, Y. Electrodeposition preparation of ZnAlCe-LDH film for corrosion protection of 6061 Al alloy. Mater. Lett. 2024, 359, 135965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, C.S.; Bastos, A.C.; Salak, A.N.; Starykevich, M.; Rocha, D.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Cunha, A.; Almeida, A.; Tedim, J.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Layered Double Hydroxide Clusters as Precursors of Novel Multifunctional Layers: A Bottom-Up Approach. Coatings 2019, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Luo, X.; Pan, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Enhanced corrosion resistance of LiAl-layered double hydroxide (LDH) coating modified with a Schiff base salt on aluminum alloy by one step in-situ synthesis at low temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 463, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Xie, Z.-H.; Yu, G. Duplex coating combining layered double hydroxide and 8-quinolinol layers on Mg alloy for corrosion protection. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 283, 1845–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F. Preparation of slippery liquid-infused porous surface based on MgAlLa-layered double hydroxide for effective corrosion protection on AZ31 Mg alloy. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 131, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailau, A.; Maltanava, H.; Poznyak, S.K.; Salak, A.N.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Yasakau, K.A.; Ferreira, M.G.S. One-step synthesis and growth mechanism of nitrate intercalated ZnAl LDH conversion coatings on zinc. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 6878–6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouali, A.C.; Iuzviuk, M.H.; Serdechnova, M.; Yasakau, K.A.; Wieland, D.C.F.; Dovzhenko, G.; Maltanava, H.; Zobkalo, I.A.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Zn-Al LDH growth on AA2024 and zinc and their intercalation with chloride: Comparison of crystal structure and kinetics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 501, 144027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuzviuk, M.H.; Bouali, A.C.; Serdechnova, M.; Yasakau, K.A.; Wieland, D.C.F.; Dovzhenko, G.; Mikhailau, A.; Blawert, C.; Zobkalo, I.A.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; et al. In situ kinetics studies of Zn-Al LDH intercalation with corrosion related species. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 17574–17586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasakau, K.A.; Kuznetsova, A.; Maltanava, H.M.; Poznyak, S.K.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Corrosion protection of zinc by LDH conversion coatings. Corros. Sci. 2024, 229, 111889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, A.S.; Gonon, M.; Belfiore, A.; Paint, Y.; Hang To, T.X.; Olivier, M.-G. Influence of solution pH on the structure formation and protection properties of ZnAlCe hydrotalcites layers on hot-dip galvanized steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 472, 129918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, G.E. The role of some thiosemicarbazide derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for C-steel in acidic media. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2529–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, P.; Kalaignan, G.P. 1, 4-Bis (2-nitrobenzylidene) thiosemicarbazide as Effective Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, K.; Mohan, R.; Anupama, K.K.; Joseph, A. Electrochemical and theoretical studies on the synergistic interaction and corrosion inhibition of alkyl benzimidazoles and thiosemicarbazide pair on mild steel in hydrochloric acid. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 149–150, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.S.; Ansari, K.R.; Sorour, A.A.; Quraishi, M.A.; Lgaz, H.; Salghi, R. Thiosemicarbazide and thiocarbohydrazide functionalized chitosan as ecofriendly corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.M.; Rastogi, R.B.; Upadhyay, B.N.; Yadav, M. Thiosemicarbazide, phenyl isothiocyanate and their condensation product as corrosion inhibitors of copper in aqueous chloride solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 80, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Pham, C.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, Q.K.; Nguyen, A.S.; Cornil, D.; Cornil, J.; Nguyen, T.D.; Belfiore, A.; To, T.X.H.; et al. Acyl thiosemicarbazides as novel inhibitors for zinc substrate in saline solution. J. Mol. Struct. 2026, 1351, 144342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, A.S.; Paint, Y.; Gonon, M.; To, T.X.H.; Olivier, M.-G. A comparative study of the structure and corrosion resistance of ZnAl hydrotalcite conversion layers at different Al3+/Zn2+ ratios on electrogalvanized steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 429, 127948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmy, A.; Ibrahim, K.; Bekheit, M.; Mostafa, M. Synthesis and Structural Studies of Co (II), Ni (II), Cu (II), Zn (II) and Cd (II) Chelates Derived From Semicarbazide and Thiosemicarbazide Derivatives. J. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 1985, 15, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Pham, Q.T.; Phung, Q.M.; Le, C.D.; Pham, T.T.; Pham, T.N.O.; Pham, C.T. Syntheses, Structures, and Biological Activities of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes with some 1-picolinoyl-4-substituted Thiosemicarbazides. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1269, 133871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, A.S.; Gonon, M.; Noirfalise, X.; Paint, Y.; To, T.X.H.; Olivier, M.-G. Study of the formation and anti-corrosion properties of Zn Al hydrotalcite conversion films grown “in situ” on different zinc alloys coated steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 173, 107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, K.; Furuya, S.; Buchheit, R.G. Effect of Solution pH on Layered Double Hydroxide Formation on Electrogalvanized Steel Sheets. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Wu, W. High corrosion-resistant octanoic acid vapor-phase modified Ce-LDH surface film of aluminum alloy. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 686, 133370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, F.; Yan, Z.; Sun, Z. Efficient degradation of diuron using Fe-Ce-LDH/13X as novel heterogeneous electro-Fenton catalyst. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 910, 116189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, T.; Quan, D.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Shen, Y. Thiosemicarbazide-Linked Covalent Organic Framework: Preparation, Properties and Applications. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 11490–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, B.; Niu, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Bai, L. Synthesis of silica supported thiosemicarbazide for Cu(II) and Zn(II) adsorption from ethanol: A comparison with aqueous solution. Fuel 2021, 286, 119287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, A.; Liu, J. Interface engineering of double-layered nanosheets via cosynergistic modification by LDH interlayer carbonate anion and molybdate for accelerated industrial water splitting at high current density. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 598, 153690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Menon, D.; Jain, P.; Prakash, P.; Misra, S.K. Linker mediated enhancement in reusability and regulation of Pb(II) removal mechanism of Cu-centered MOFs. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 318, 123941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlica, D.K.; Kokalj, A.; Milošev, I. Synergistic effect of 2-mercaptobenzimidazole and octylphosphonic acid as corrosion inhibitors for copper and aluminium—An electrochemical, XPS, FTIR and DFT study. Corros. Sci. 2021, 182, 109082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Jeschke, S.; Murdoch, B.J.; Hirth, S.; Eiden, P.; Gorges, J.N.; Keil, P.; Chen, X.-B.; Cole, I. In-depth insights of inhibitory behaviour of 2-amino-4-methylthiazole towards galvanised steel in neutral NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2022, 199, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.D.; Peng, Z.C.; Dong, B.Q.; Wang, Y.S. In situ growth of corrosion resistant Mg-Fe layered double hydroxide film on Q235 steel. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 610, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi Asl, V.; Zhao, J.; Palizdar, Y.; Junaid Anjum, M. Influence of pH value and Zn/Ce cations ratio on the microstructures and corrosion resistance of LDH coating on AZ31. Corros. Commun. 2022, 5, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi Asl, V.; Zhao, J.; Anjum, M.J.; Wei, S.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Z. The effect of cerium cation on the microstructure and anti-corrosion performance of LDH conversion coatings on AZ31 magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 821, 153248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Element Content (wt%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Al | Zn | Ce | Cl | N | S | |

| Before immersion in NaCl | |||||||

| ZnAl LDH/HL | 32.0 | 7.4 | 56.6 | - | - | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| ZnAlCe LDH/HL | 35.8 | 9.6 | 44.1 | 6.2 | - | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| After 168 h of immersion in NaCl | |||||||

| ZnAl LDH/HL | 39.7 | 5.9 | 50.2 | - | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| ZnAlCe LDH/HL | 40.4 | 7.7 | 41.2 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Samples | Time (h) | Qf1 (Ω−1·sn·cm−2) | nf1 | Rf1 (Ω·cm2) | Qf2 (Ω−1·sn·cm−2) | nf2 | Rf2 (Ω·cm2) | Qdl (Ω−1·sn·cm−2) | n | Rct (Ω·cm2) | |Z|10mHz (Ω·cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnAl LDH/HL | 2 | 1.61 × 10−5 | 0.72 | 188 | 2.15 × 10−5 | 0.80 | 5166 | 1.95 × 10−4 | 0.81 | 7430 | 10,921 |

| 24 | 1.89 × 10−5 | 0.71 | 268 | 3.25 × 10−5 | 0.82 | 5846 | 2.85 × 10−4 | 0.83 | 10,360 | 13,788 | |

| 72 | 4.38 × 10−5 | 0.64 | 319 | 5.74 × 10−5 | 0.73 | 6041 | 4.57 × 10−4 | 0.80 | 9840 | 13,039 | |

| 168 | 5.42 × 10−5 | 0.62 | 332 | 6.21 × 10−5 | 0.71 | 6025 | 5.85 × 10−4 | 0.80 | 7810 | 12,434 | |

| ZnAlCe LDH/HL | 2 | 4.25 × 10−6 | 0.88 | 1771 | 1.45 × 10−5 | 0.54 | 5312 | 1.15 × 10−4 | 0.84 | 20,670 | 18,448 |

| 24 | 4.29 × 10−6 | 0.89 | 1802 | 1.49 × 10−5 | 0.55 | 6001 | 1.18 × 10−4 | 0.85 | 21,260 | 18,533 | |

| 72 | 4.30 × 10−6 | 0.90 | 1889 | 2.05 × 10−5 | 0.55 | 6325 | 1.20 × 10−4 | 0.89 | 23,210 | 20,097 | |

| 168 | 4.02 × 10−6 | 0.90 | 1890 | 3.01 × 10−5 | 0.55 | 6402 | 1.22 × 10−4 | 0.89 | 26,010 | 21,663 | |

| ZnAl LDH | 2 | 1.89 × 10−5 | 0.7 | 182 | 2.34 × 10−5 | 0.85 | 4803 | 1.08 × 10−3 | 0.75 | 6071 | 9927 |

| 24 | 3.01 × 10−5 | 0.74 | 489 | 7.24 × 10−5 | 0.75 | 4087 | 1.32 × 10−3 | 0.83 | 8777 | 8615 | |

| ZnAlCe LDH | 2 | 5.17 × 10−6 | 0.88 | 1684 | 1.65 × 10−5 | 0.55 | 4926 | 2.89 × 10−4 | 0.73 | 11,640 | 13,049 |

| 24 | 5.71 × 10−6 | 0.88 | 1609 | 2.02 × 10−5 | 0.52 | 5033 | 1.74 × 10−4 | 0.71 | 10,920 | 12,664 | |

| 72 | 5.94 × 10−6 | 0.88 | 1630 | 1.84 × 10−5 | 0.53 | 5152 | 1.27 × 10−4 | 0.82 | 18,700 | 18,282 | |

| 168 | 3.30 × 10−6 | 0.90 | 1709 | 4.45 × 10−5 | 0.55 | 5370 | 1.37 × 10−4 | 0.90 | 25,340 | 21,078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, A.S.; Pham, C.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Gonon, M.; Dangreau, L.; Noirfalise, X.; Nguyen, T.D.; To, T.X.H.; Olivier, M.-G. Picolinoyl N4-Phenylthiosemicarbazide-Modified ZnAl and ZnAlCe Layered Double Hydroxide Conversion Films on Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel for Enhancing Corrosion Protection in Saline Solution. Metals 2026, 16, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010115

Pham TT, Nguyen AS, Pham CT, Nguyen HN, Gonon M, Dangreau L, Noirfalise X, Nguyen TD, To TXH, Olivier M-G. Picolinoyl N4-Phenylthiosemicarbazide-Modified ZnAl and ZnAlCe Layered Double Hydroxide Conversion Films on Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel for Enhancing Corrosion Protection in Saline Solution. Metals. 2026; 16(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010115

Chicago/Turabian StylePham, Thu Thuy, Anh Son Nguyen, Chien Thang Pham, Hong Nhung Nguyen, Maurice Gonon, Lisa Dangreau, Xavier Noirfalise, Thuy Duong Nguyen, Thi Xuan Hang To, and Marie-Georges Olivier. 2026. "Picolinoyl N4-Phenylthiosemicarbazide-Modified ZnAl and ZnAlCe Layered Double Hydroxide Conversion Films on Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel for Enhancing Corrosion Protection in Saline Solution" Metals 16, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010115

APA StylePham, T. T., Nguyen, A. S., Pham, C. T., Nguyen, H. N., Gonon, M., Dangreau, L., Noirfalise, X., Nguyen, T. D., To, T. X. H., & Olivier, M.-G. (2026). Picolinoyl N4-Phenylthiosemicarbazide-Modified ZnAl and ZnAlCe Layered Double Hydroxide Conversion Films on Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel for Enhancing Corrosion Protection in Saline Solution. Metals, 16(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010115