Determination of Damage Constant and Critical Damage by the Combined Experiment and FEM Using the Reference Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Two Clear Fracture Cases—Reference Processes

2.1. Tensile Test

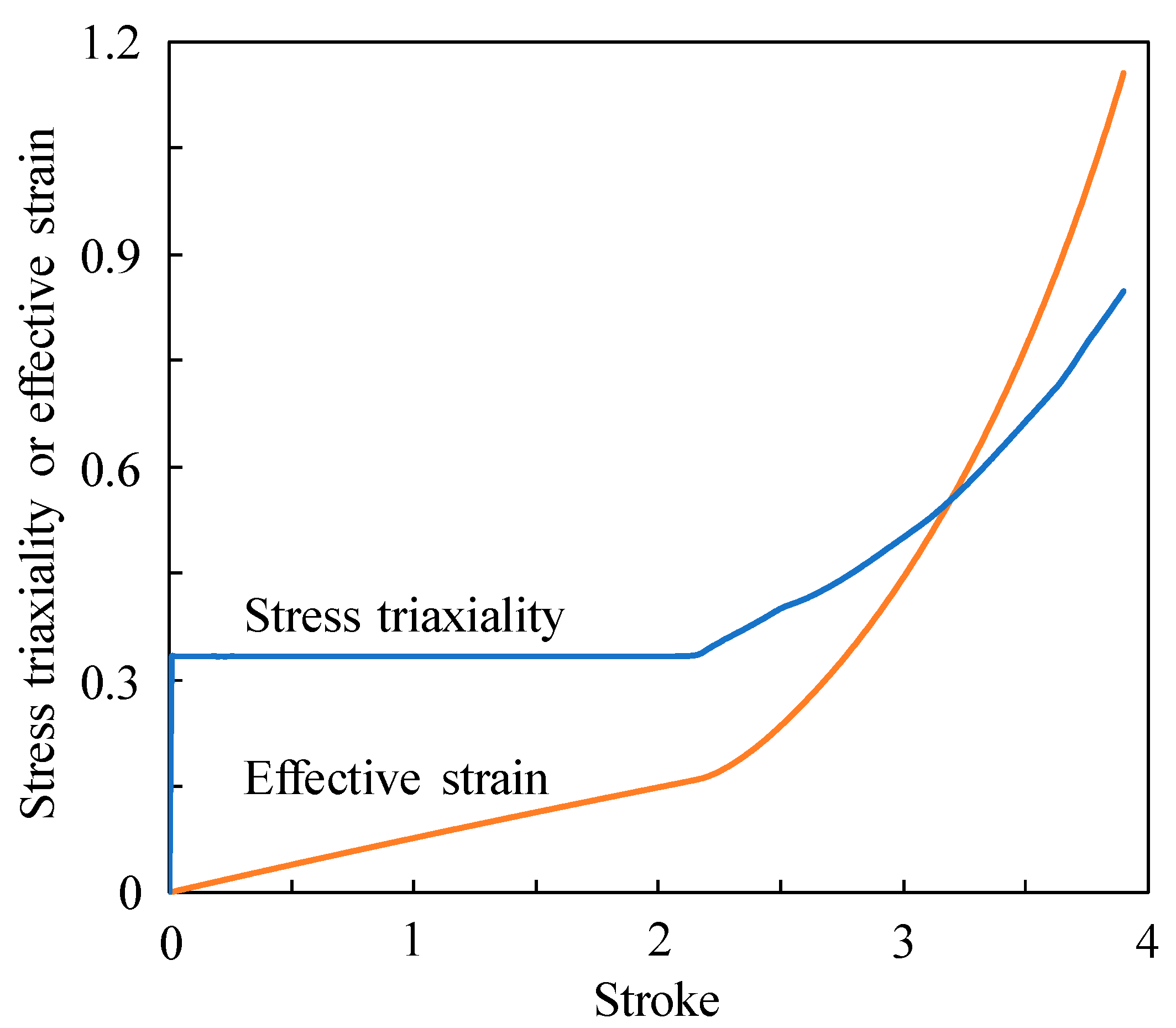

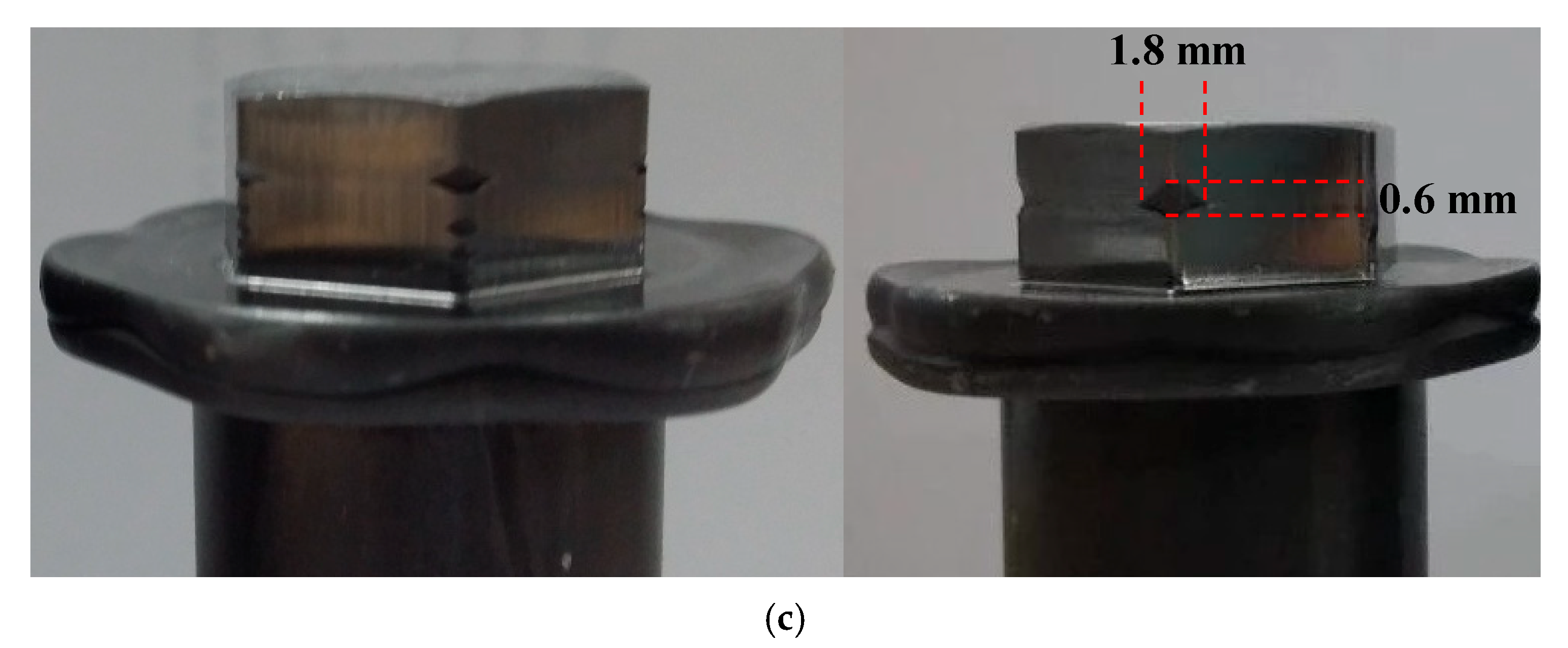

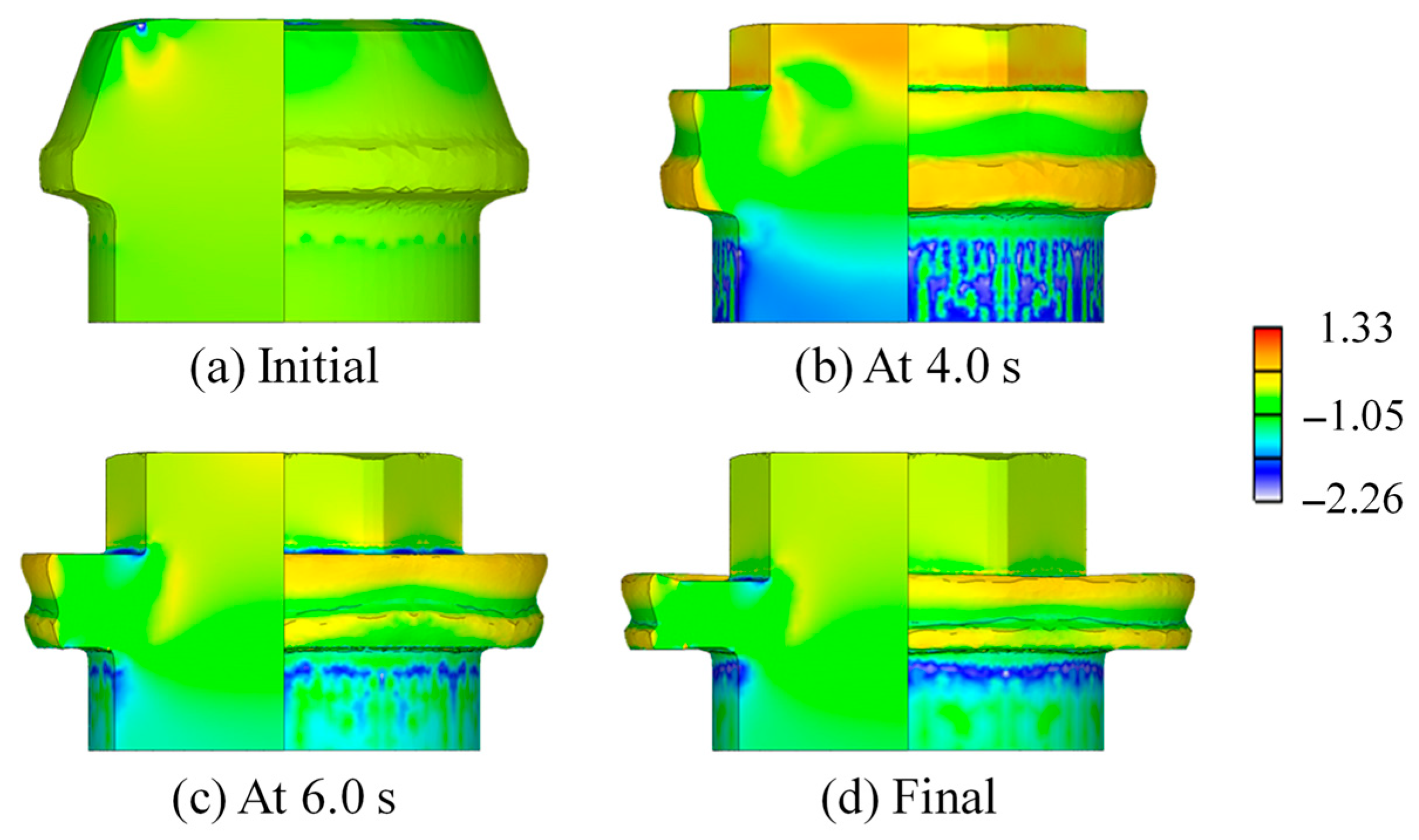

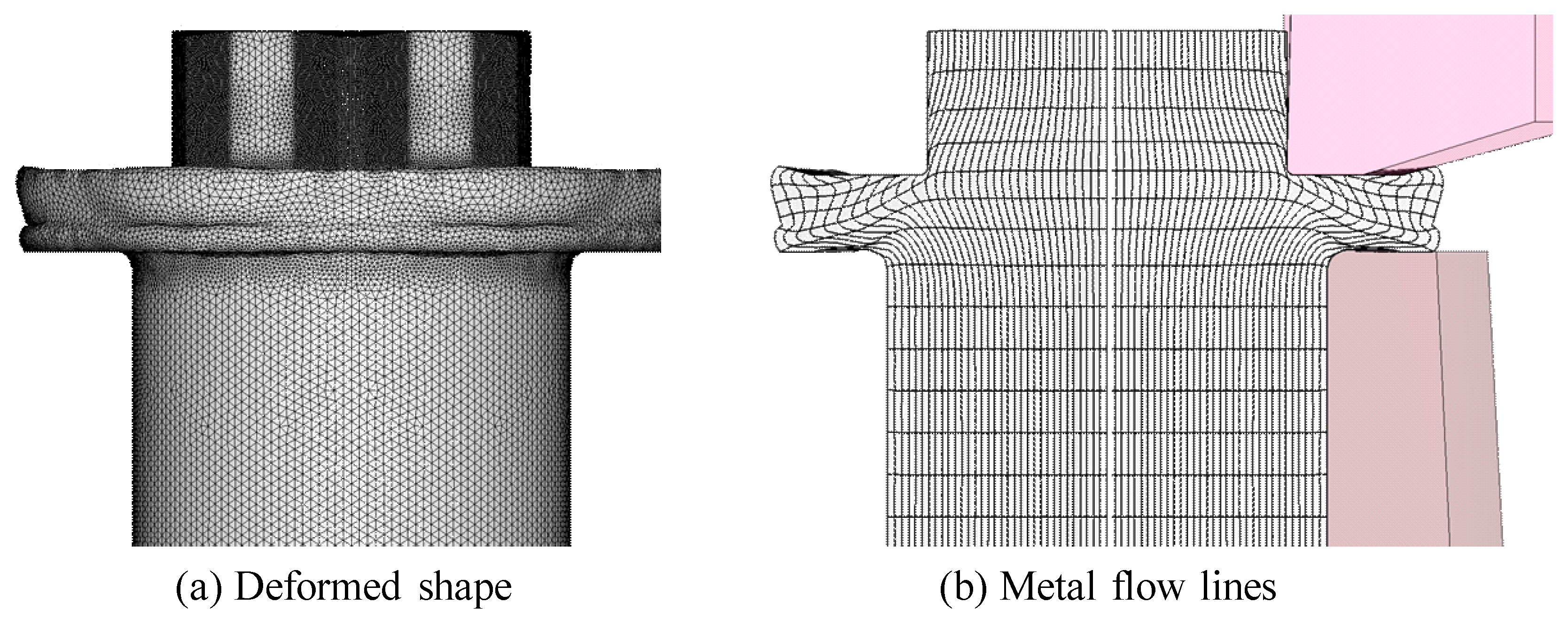

2.2. Bolt Heading Process

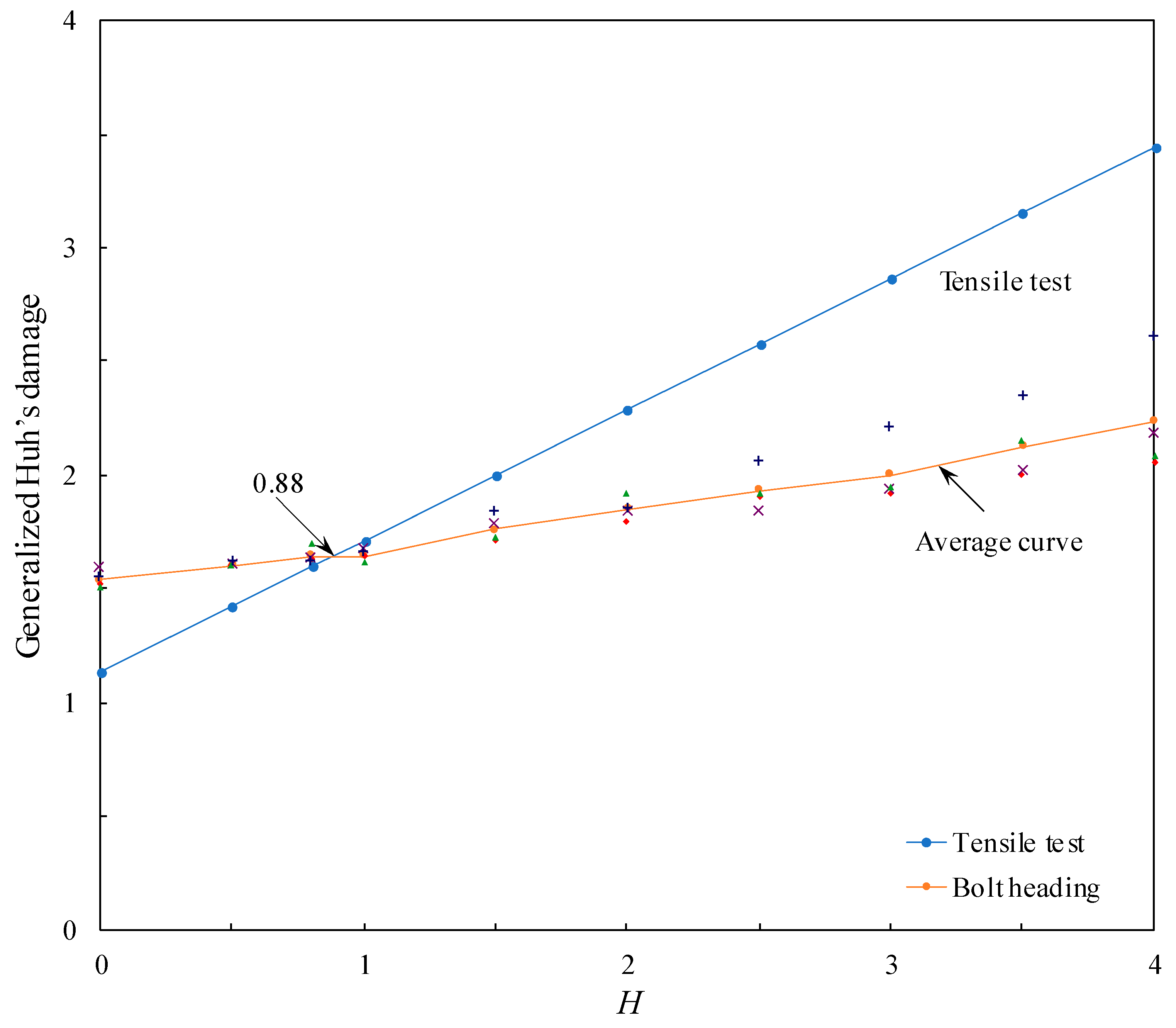

3. Characterization of Damage Constant of the Generalized Huh’s Damage Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenthal, M. The Inelastic Behavior of Engineering Materials and Structures; John Wiley Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1950; Volume 55, p. 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, F.A. A criterion for ductile fracture by the growth of holes. J. Appl. Mech. 1968, 35, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft, M.G.; Latham, D.J. Ductility and workability of metals. J. Inst. Met. 1968, 96, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, J.R.; Tracey, D.M. On the ductile enlargement of voids in triaxial stress fields. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1969, 17, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozzo, P.; Deluca, B.; Rendina, R. A new method for the prediction of formability limits in metal sheets. In Proceedings of the 7th Biennial Congress of the IDDRG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 9–13 October 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gurson, A.L. Continuum theory of ductile rupture by void nucleation and growth. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1977, 99, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D.M.; Reaugh, J.E.; Moran, B.; Quin˜ones, D.F. A plastic strain mean-stress criterion for ductile fracture. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1978, 100, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyane, M.; Sato, T.; Okimoto, K.; Shima, S. Criteria for ductile fracture and their applications. J. Mech. Work. Technol. 1980, 4, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, A.; Tvergaard, V. An analysis of ductile rupture in notched bars. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1984, 32, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1985, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoudadi, R.; Meester, P.D.E.; Vandermeulen, W. Damage work as ductile fracture criterion. Int. J. Fract. 1994, 66, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, R. Design of Crashworthy Ship Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2003; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y.K.; Lee, J.S.; Huh, H.; Kim, H.; Park, S. Prediction of fracture in hub-hole expanding process using a new ductile fracture criterion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 187–188, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wierzbicki, T. A new model of metal plasticity and fracture with pressure and Lode dependence. Int. J. Plast. 2008, 24, 1071–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Huh, H. Extension of a shear-controlled ductile fracture model considering the stress triaxiality and the lode parameter. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013, 50, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukamm, F.; Feucht, M.; Haufe, A. Consistent damage modelling in the process chain of forming to crashworthiness simulations. LS-Dyna Anwenderforum 2008, 30, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, A.; Fujikawa, S.; Ikeda, A.; Shiga, N. Prediction of ductile fracture in cold forging. Procedia Eng. 2014, 81, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickhey, F.; Hong, S.M. Stress triaxiality in anisotropic metal sheets—Definition and experimental acquisition for numerical damage prediction. Materials 2022, 15, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yamanaka, M.; Altan, T. Prediction and elimination of ductile fracture in cold forging by FEM simulations. In Proceedings of the 23th NAMRC Conference, Lincoln, Nebraska, 24–26 May 1995; pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kõrgesaa, M. The effect of low stress triaxialities and deformation paths on ductile fracture simulations of large shell structure. Mar. Struct. 2019, 63, 4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Ji, S.M.; Joun, M.S.; Lee, S.W.; Hong, S.M. Flow behavior dependence of rod shearing phenomena of various materials in automatic multi-stage cold forging. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.J.; Lim, J.M.; Hong, S.M. Determination and verification of GISSMO fracture properties of bolts used in radioactive waste transport containers. Materials 2022, 15, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joun, M.S.; Razali, M.K.; Jee, C.W.; Byun, J.B.; Kim, M.C.; Kim, K.M. A review of flow characterization of metallic materials in the cold forming temperature range and its major issues. Materials 2022, 15, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, M.K.; Ju, Y.W. Extraction of equivalent stress versus equivalent plastic strain curve of necking material in tensile test without assuming constitutive model. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 2024, 146, 021007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.Y.; Kim, N.H.; Razali, M.K.; Lee, H.M.; Joun, M.S. Analytical and numerical evaluation of the relationship between elongation calibration function and cyber standard tensile tests for ductile materials. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joun, M.S. Recent advances in metal forming simulation technology for automobile parts by AFDEX. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 834, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.N.; Brezzi, F.; Fortin, M. A stable finite element for the Stokes equations. Calcolo 1984, 21, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Chung, S.H.; Jang, S.M.; Joun, M.S. Three-dimensional simulation of forging using tetrahedral and hexahedral elements. Finite. Elem. Anal. Des. 2009, 45, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.K.; Joun, M.S.; Chung, W.J. A novel flow model of strain hardening and softening for use in tensile testing of a cylindrical specimen at room temperature. Materials 2021, 14, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joun, M.S.; Heo, Y.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, N.Y. On lubrication regime changes during forward extrusion, forging, and drawing. Lubricants 2024, 12, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Joun, M.S.; Lee, J.K. Adaptive tetrahedral element generation and refinement to improve the quality of bulk metal forming simulation. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2007, 43, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, B.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.; Joun, M. Determination of Damage Constant and Critical Damage by the Combined Experiment and FEM Using the Reference Processes. Metals 2025, 15, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121376

Hong B, Lee H, Hong S, Joun M. Determination of Damage Constant and Critical Damage by the Combined Experiment and FEM Using the Reference Processes. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121376

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Boseung, Hyeonmin Lee, Seokmoo Hong, and Mansoo Joun. 2025. "Determination of Damage Constant and Critical Damage by the Combined Experiment and FEM Using the Reference Processes" Metals 15, no. 12: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121376

APA StyleHong, B., Lee, H., Hong, S., & Joun, M. (2025). Determination of Damage Constant and Critical Damage by the Combined Experiment and FEM Using the Reference Processes. Metals, 15(12), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121376