Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Compositional Space Exploration

Abstract

1. Introduction

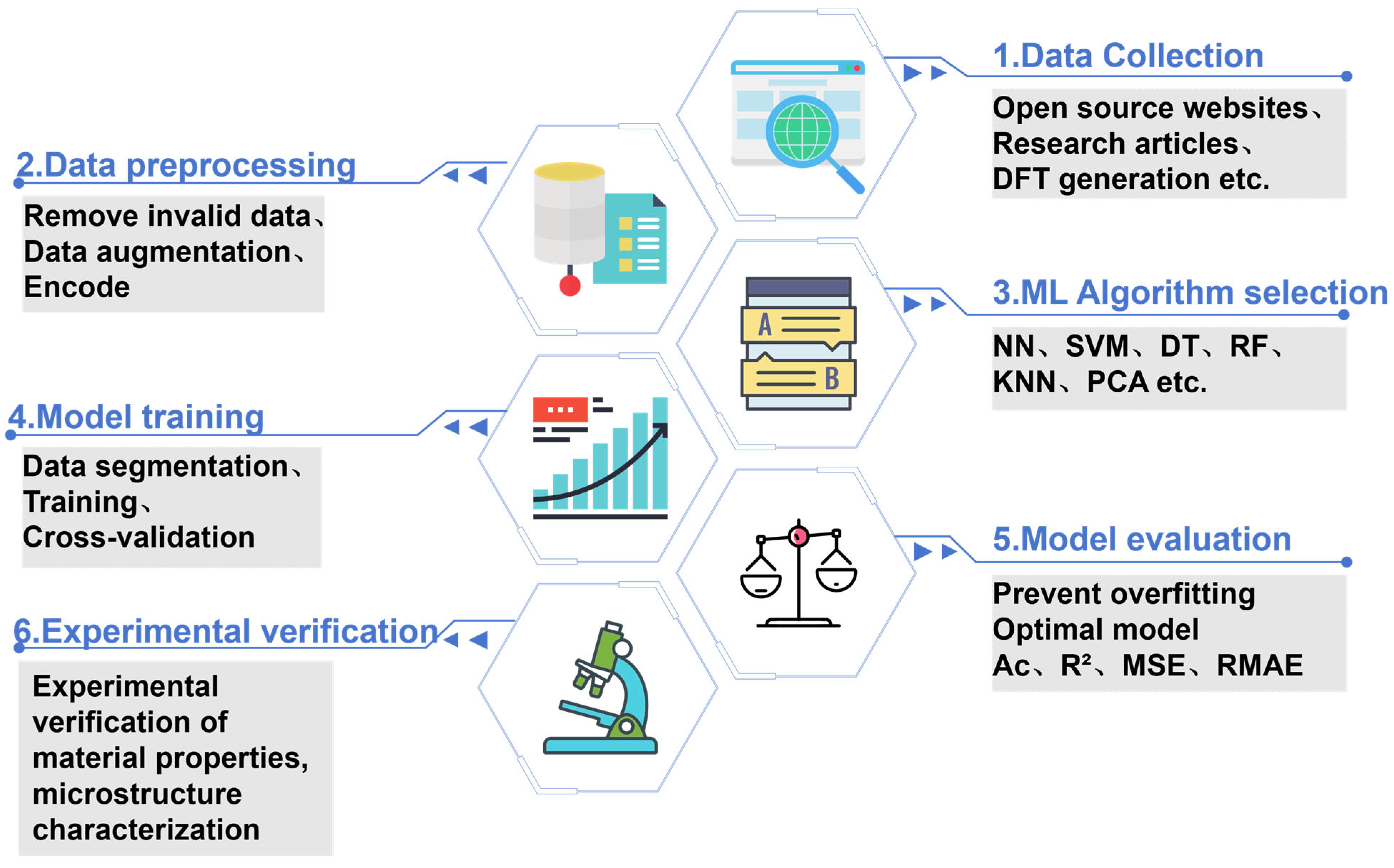

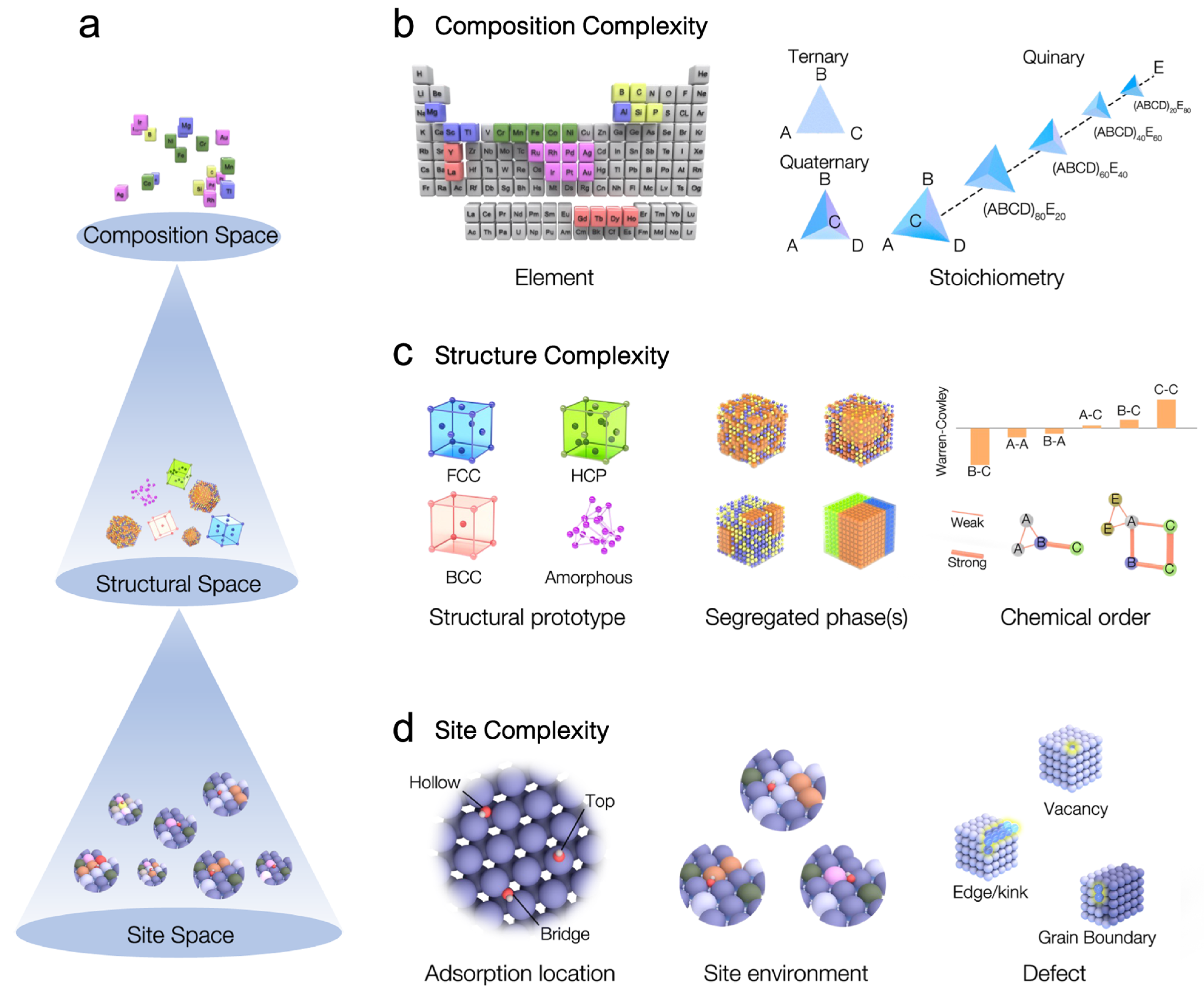

2. General Workflow for Machine Learning (In HEA Design)

2.1. Key Components of Machine Learning

2.1.1. Data Preparation

2.1.2. Algorithm Selection

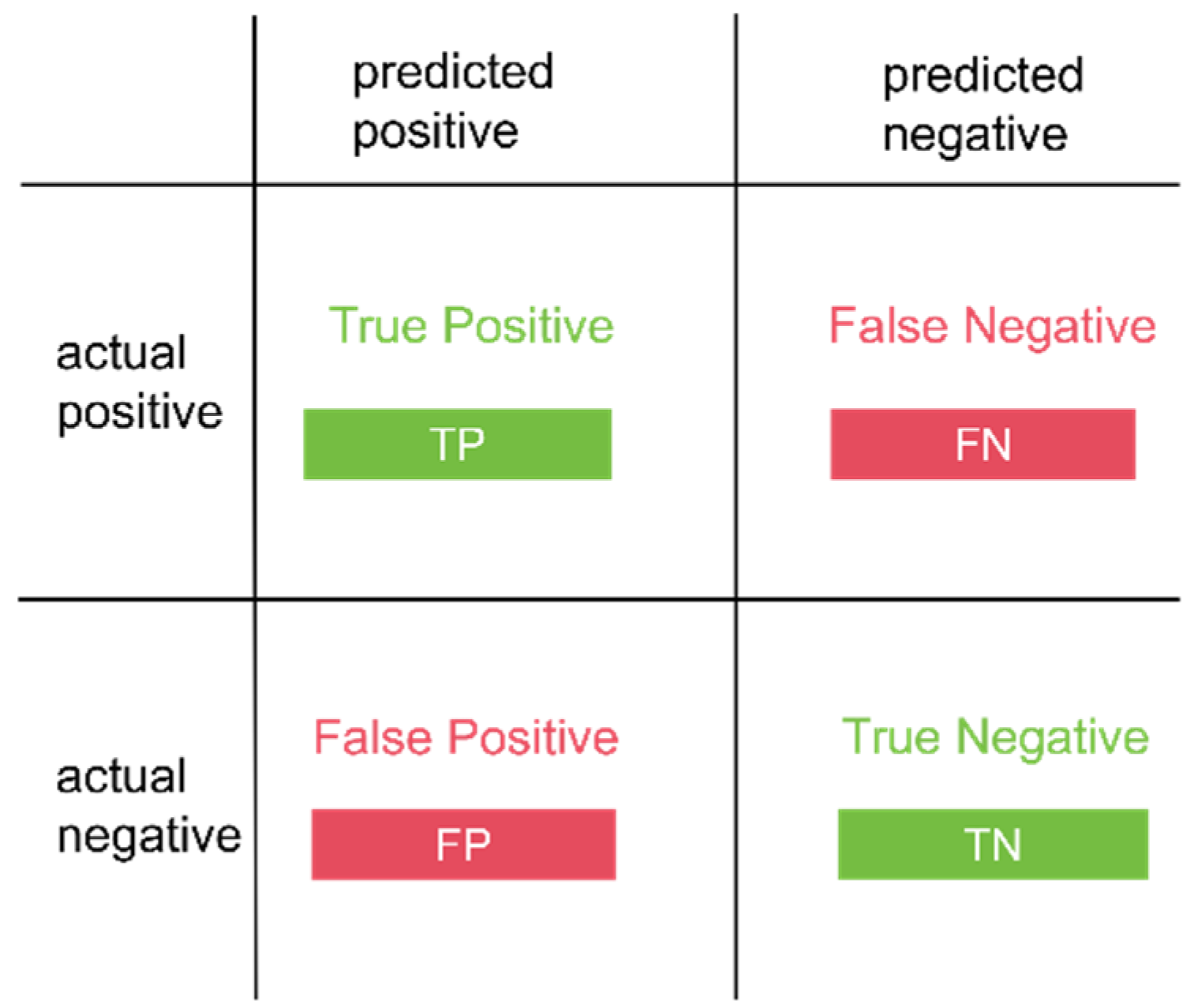

2.1.3. Model Training and Evaluation

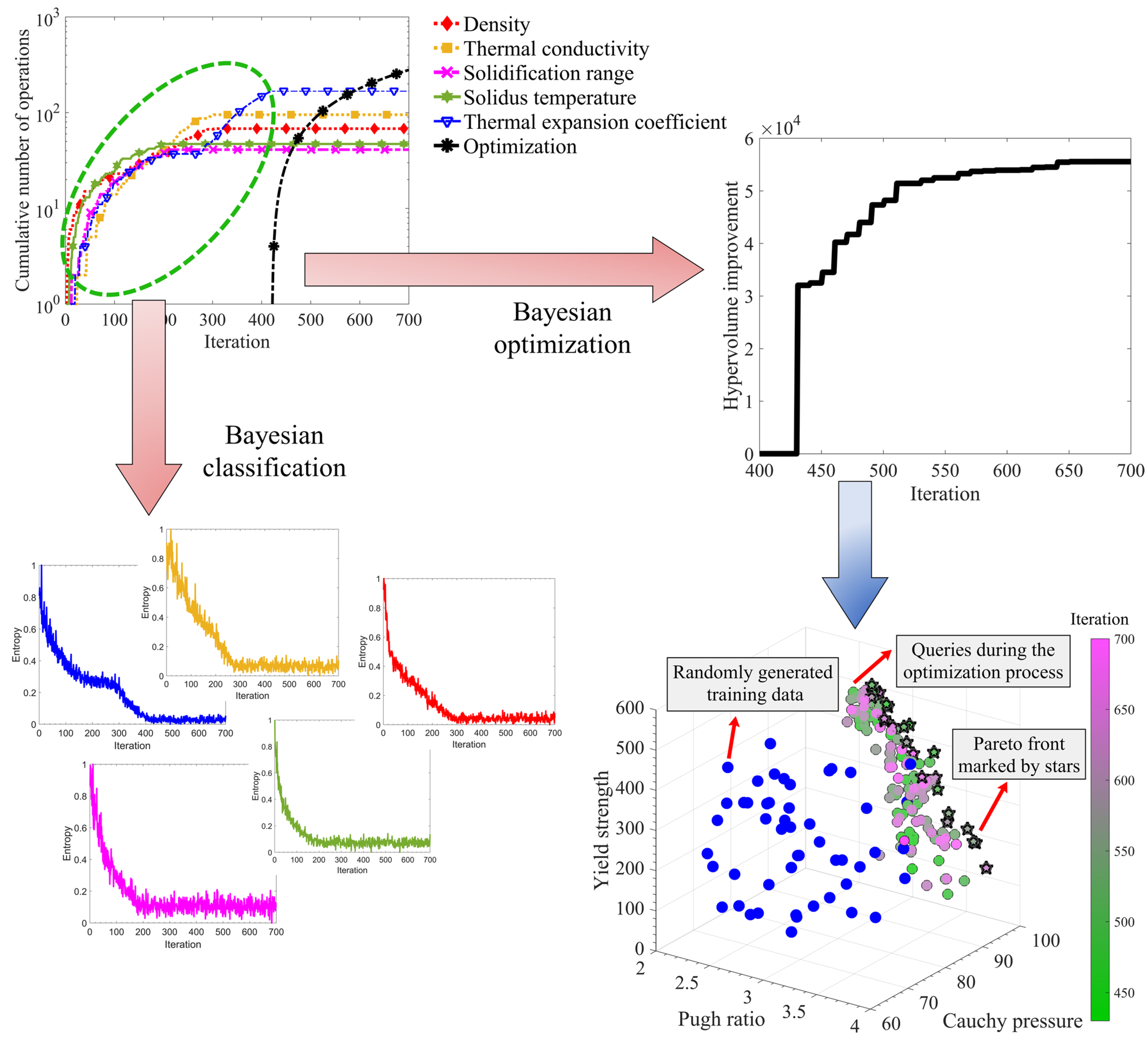

2.2. Example Diagram of the Application of Machine Learning to Phase Prediction, Performance and Composition Design

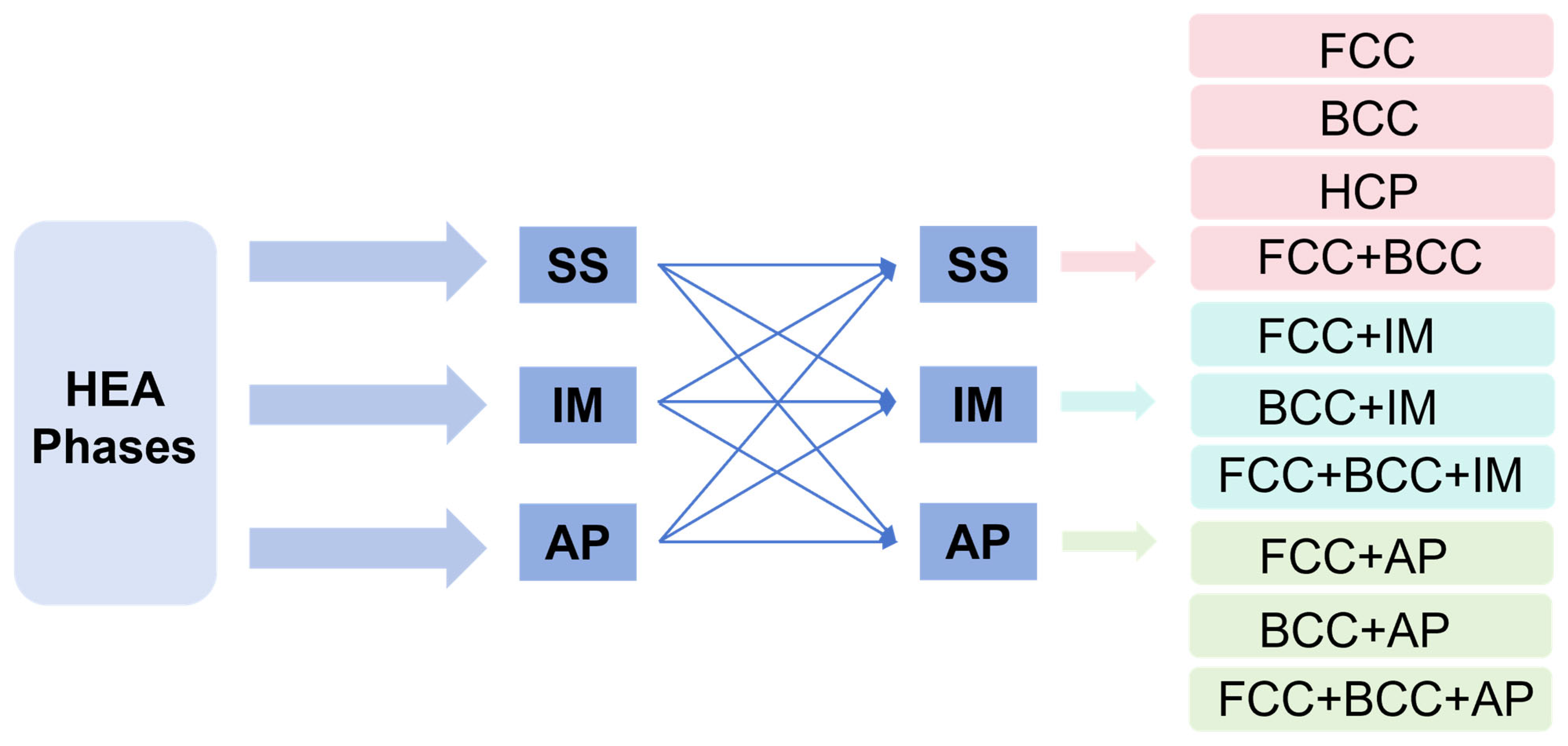

3. Phase Prediction of HEA

3.1. ML Model Prediction

3.1.1. RF

3.1.2. NN

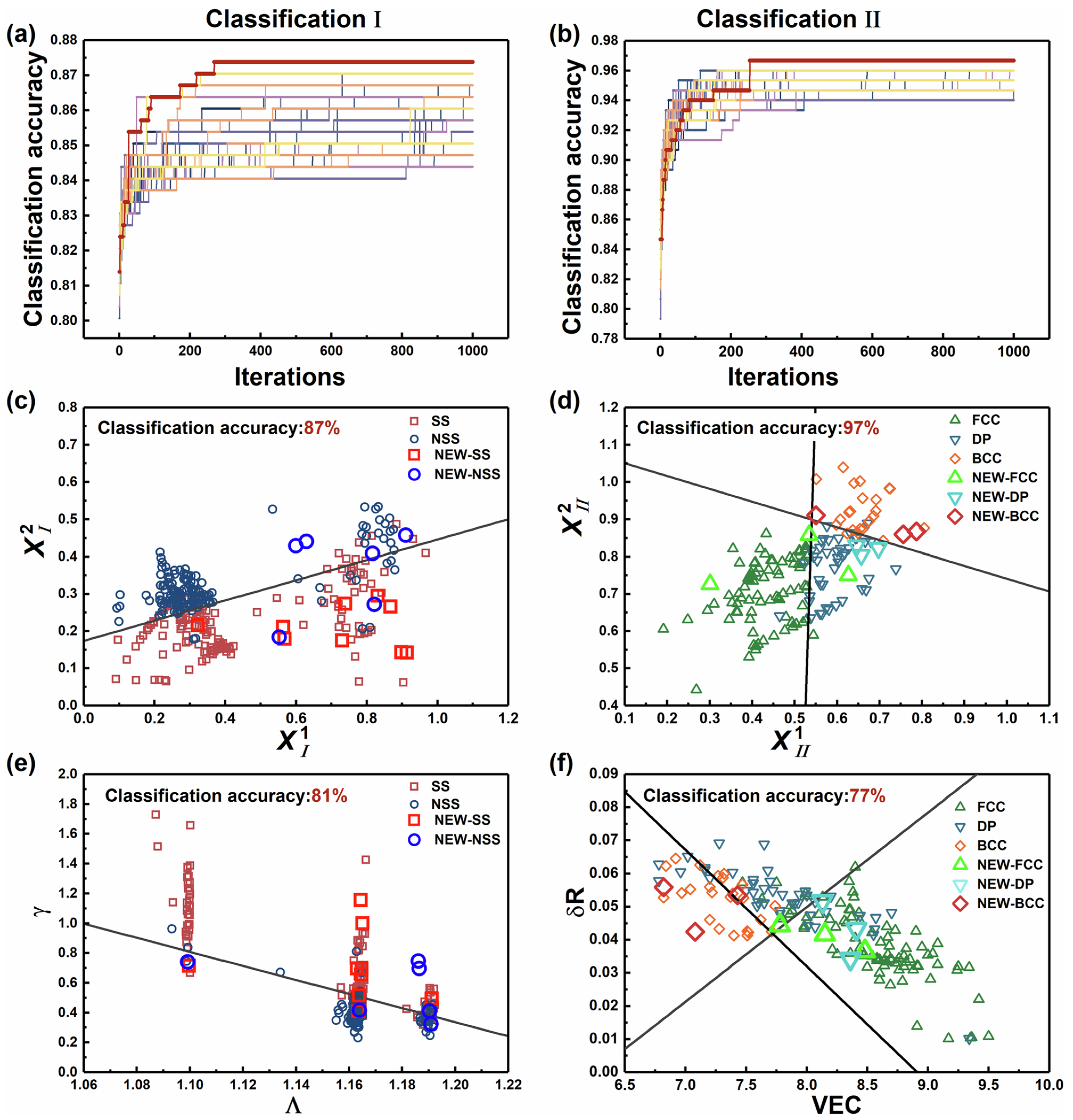

3.1.3. SVM

3.1.4. KNN

3.1.5. Boosting

3.2. Mixed Model Phase Prediction

3.2.1. Combined with Thermodynamic Calculations

3.2.2. Combined with DS Evidence Theory

3.3. Incorporating Physical Constraints into Machine Learning and the Applicability Boundaries of Purely Data-Driven Methods

3.4. Multi-Model Integration and Structural Fusion: From Statistical Complementarity to Mechanism-Data Coupling

4. Prediction of HEA Performance

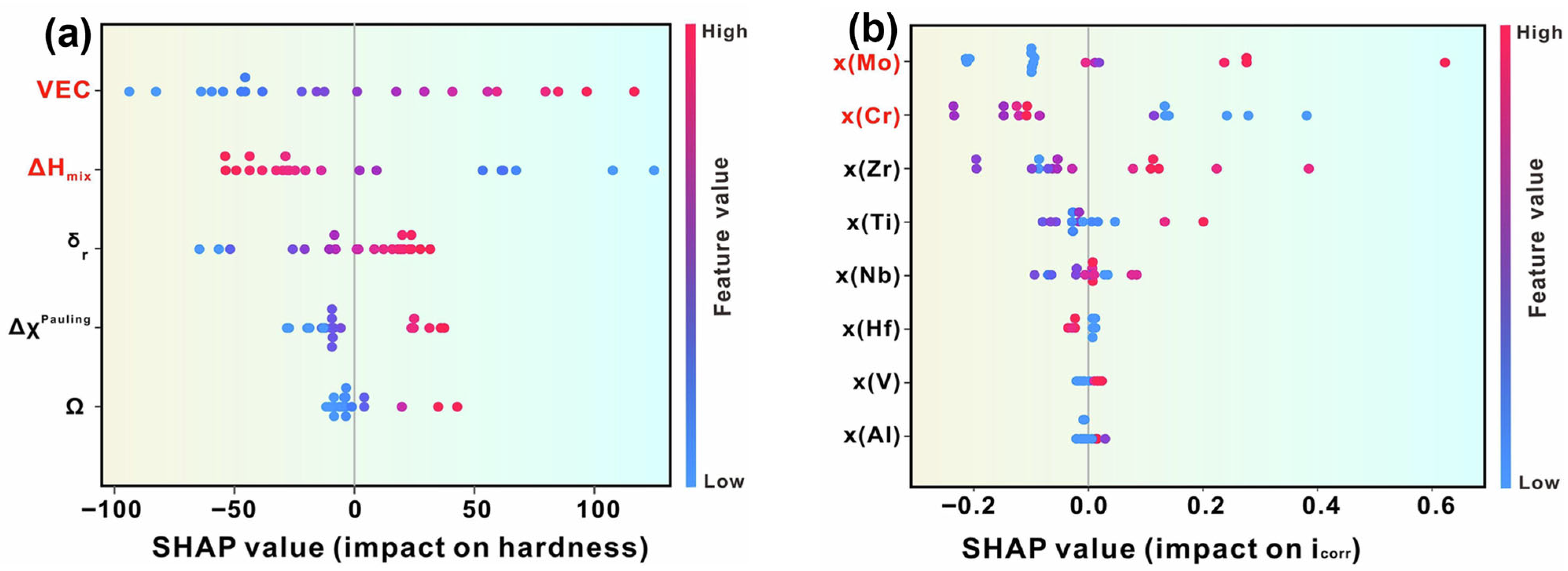

4.1. Hardness Model Prediction

4.1.1. Add SHAP Interpretation

4.1.2. Neural Network Prediction

4.1.3. Modeling of Novel Solid-State Solution Hardening (SSH)

4.2. Other Performance Predictions

4.2.1. Elastic Performance Prediction

4.2.2. Tensile Performance Prediction

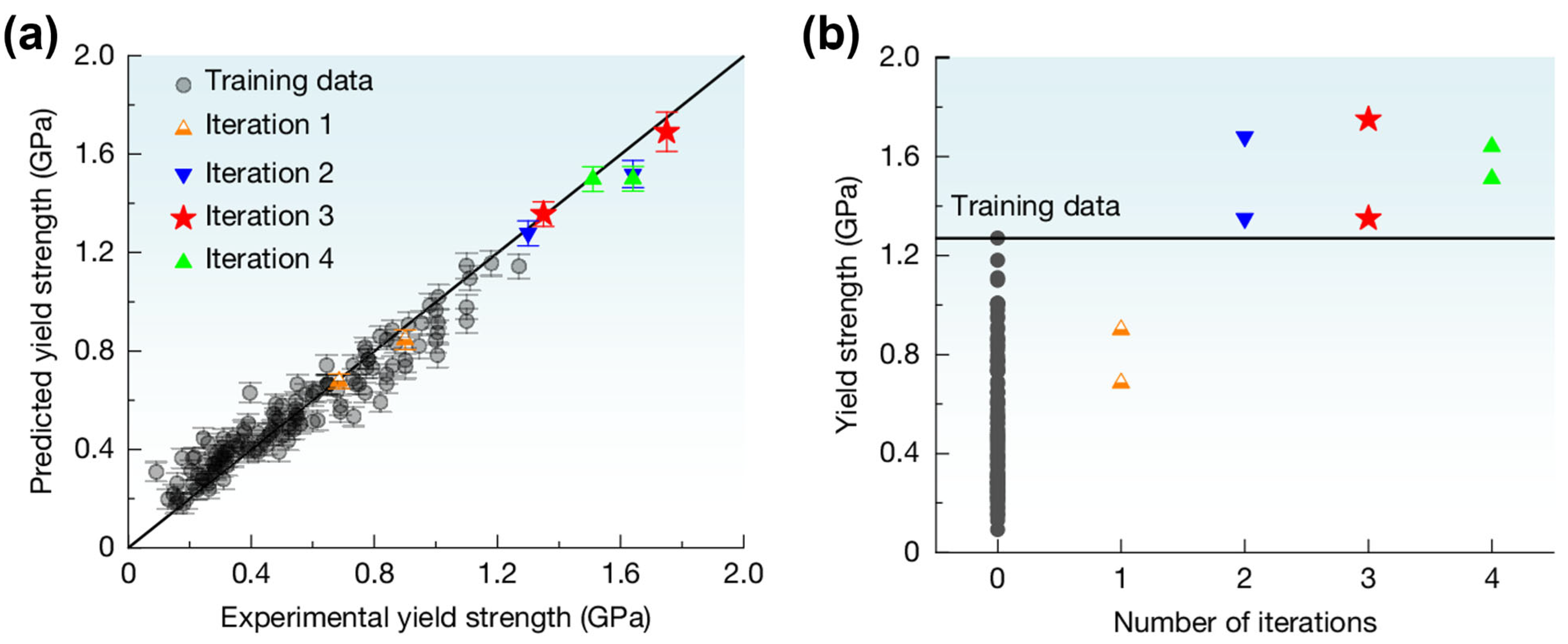

4.2.3. Yield Strength Prediction

4.2.4. Antioxidant Performance Prediction

4.2.5. Corrosion Performance Prediction

4.2.6. Prediction of Parameters Related to Mechanical Properties

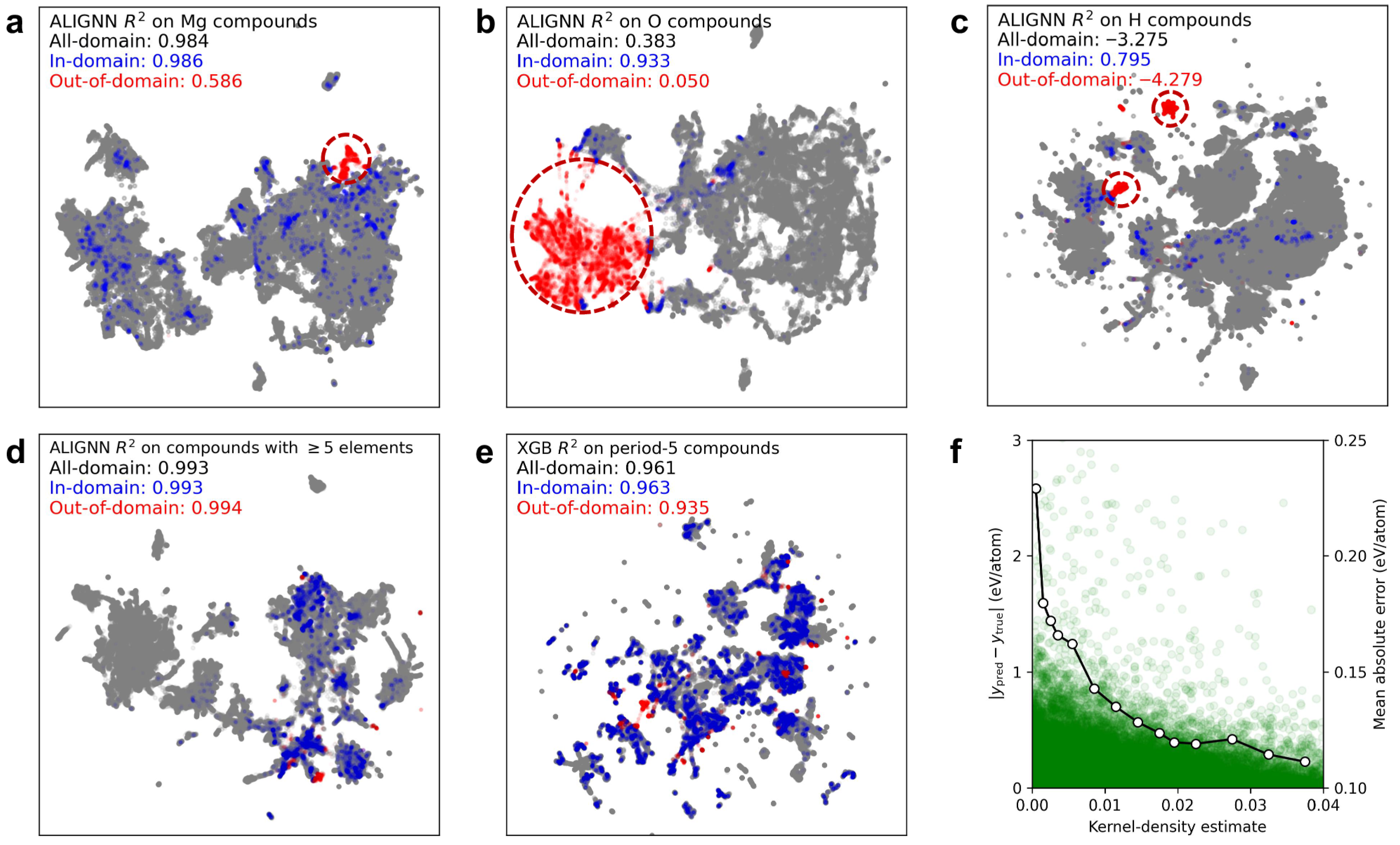

5. Design, Exploration and Optimization of New High-Entropy Alloys

- Exploring explainable relationships between HEA properties, elemental compositions, and alloy characteristics;

- Searching for high-performance HEAs across a broad compositional space;

- Employing ML algorithms to optimize both alloy composition and model parameters to identify superior HEAs.

5.1. Exploration of Structure-Activity Relationship

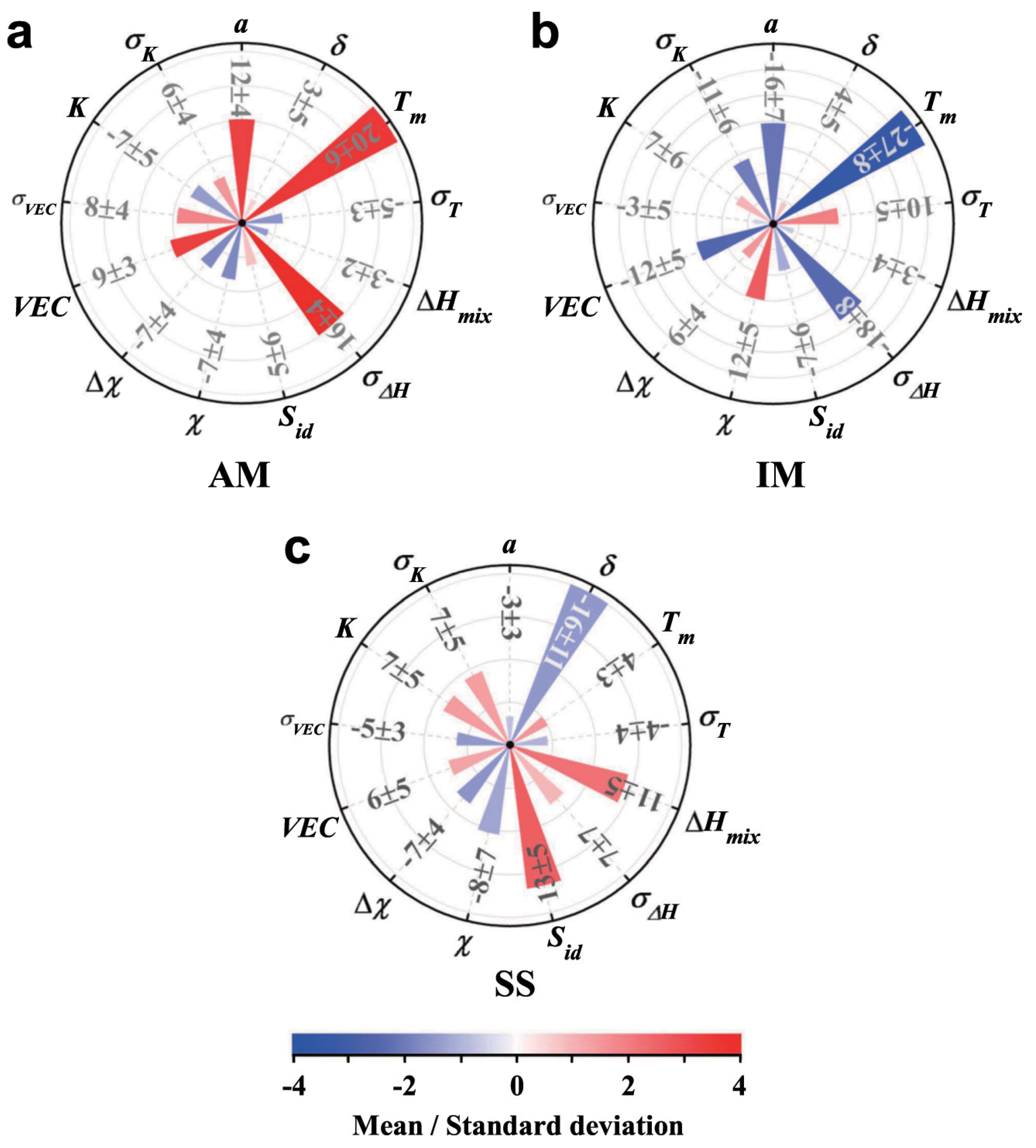

5.1.1. Feature-Correlated Structure–Property Relationships

5.1.2. Elemental Component Relationships

5.1.3. Explanatory Formulas/Parameters

5.2. Explore the HEA Space

5.2.1. DNN Global Search

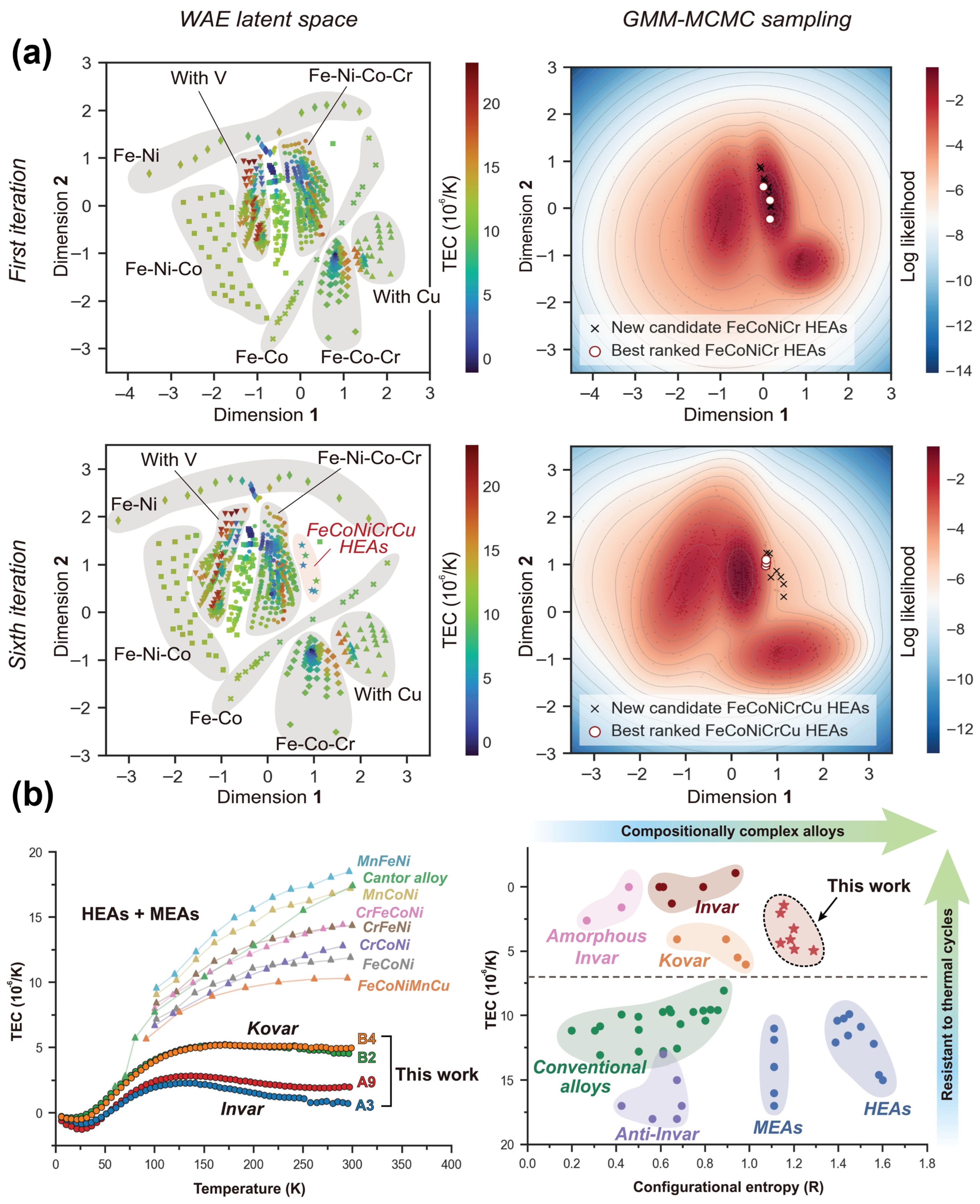

5.2.2. Active Learning Loop Iteration

5.2.3. Exploration of Eutectic High-Entropy Alloys

5.3. Optimize the Design

5.3.1. Optimize the Model Using Genetic Algorithms

5.3.2. GAN

5.3.3. Optimize the Model and Optimized Component Design

5.4. ML-Driven Research in HEAs: Emerging Trends and Applications

6. Conclusions, Challenges, and Outlooks

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Challenges

6.3. Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeh, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J.; Chin, T.-S.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chen, S.-K.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chou, S.-Y. Formation of simple crystal structures in Cu-Co-Ni-Cr-Al-Fe-Ti-V alloys with multiprincipal metallic elements. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2004, 35, 2533–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 75–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.-J.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chin, T.-S.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-K.; Yeh, J.-W.; Shun, T.-T.; Chen, S.-K. Multi-principal-element alloys with improved oxidation and wear resistance for thermal spray coating. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunce, I.; Polanski, M.; Bystrzycki, J. Structure and hydrogen storage properties of a high entropy ZrTiVCrFeNi alloy synthesized using Laser Engineered Net Shaping (LENS). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 12180–12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-M.; Jo, Y.H.; Sohn, S.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, B.-J. Understanding the physical metallurgy of the CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy: An atomistic simulation study. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlöv, A.; Ji, W.; Zhu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Babicheva, R.; An, R.; Seet, H.L.; Nai, M.L.S.; Zhou, K. Molecular dynamics study on the strengthening mechanisms of Cr–Fe–Co–Ni high-entropy alloys based on the generalized stacking fault energy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 905, 164137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Grabowski, B.; Körmann, F.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. Ab initio thermodynamics of the CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy: Importance of entropy contributions beyond the configurational one. Acta. Mater. 2015, 100, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, Y.; Toher, C.; Vecchio, K.S.; Curtarolo, S. The search for high entropy alloys: A high-throughput ab-initio approach. Acta Mater. 2018, 159, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.H.; Choi, W.M.; Kim, D.G.; Zargaran, A.; Sohn, S.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, B.J.; Kim, N.J.; Lee, S. FCC to BCC transformation-induced plasticity based on thermodynamic phase stability in novel V10Cr10Fe45CoxNi35−x medium-entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Liaw, P.K.; Gao, M.C.; Widom, M. First-principles prediction of high-entropy-alloy stability. npj Comput. Mater. 2017, 3, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zuo, Y.; Abu-Odeh, A.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.-G.; Ding, J.; Ong, S.P.; Asta, M.; Ritchie, R.O. Atomistic simulations of dislocation mobility in refractory high-entropy alloys and the effect of chemical short-range order. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Disentangling diffusion heterogeneity in high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 224, 117527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zong, H.; Ding, X.; Lookman, T. Anomalous dislocation core structure in shock compressed bcc high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2021, 209, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Shi, S.Q.; Zhang, T.Y. A machine-learning approach to predicting and understanding the properties of amorphous metallic alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 187, 108378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancret, F.; Toda-Caraballo, I.; Menou, E.; Rivera Díaz-Del-Castillo, P.E.J. Designing high entropy alloys employing thermodynamics and Gaussian process statistical analysis. Mater. Des. 2017, 115, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menou, E.; Toda-Caraballo, I.; Rivera-Díaz-del-Castillo, P.E.J.; Pineau, C.; Bertrand, E.; Ramstein, G.; Tancret, F. Evolutionary design of strong and stable high entropy alloys using multi-objective optimisation based on physical models, statistics and thermodynamics. Mater. Des. 2018, 143, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; He, Z.; Che, L.; Cheng, H.; Ge, M.; Si, T.; Xu, X. Deep alloys: Metal materials empowered by deep learning. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 2024, 179, 108514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; He, Z.; Zheng, K.; Xu, X.; Zhao, F. An automatic segmentation and quantification method for austenite and ferrite phases in duplex stainless steel based on deep learning. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 13, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.-W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, P.; Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaderberg, M.; Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Spatial transformer networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasiuk, P.; Pryczek, M. Geometric transformations embedded into convolutional neural networks. J. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2016, 24, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mounsaveng, S.; Laradji, I.; Ben Ayed, I.; Vazquez, D.; Pedersoli, M. Learning Data Augmentation with Online Bilevel Optimization for Image Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 1691–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Jiang, W.; Fan, X.; Zhang, C. Stnreid: Deep convolutional networks with pairwise spatial transformer networks for partial person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 22, 2905–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Wang, D. A survey of transfer learning. J. Big Data 2016, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Pei, Z. Machine learning for high-entropy alloys: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 131, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Tan, Q.; Knibbe, R.; Xu, M.; Jiang, B.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.-X. Recent applications of machine learning in alloy design: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2023, 155, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Hu, X.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, W.; Zhou, T. Recent machine learning-driven investigations into high entropy alloys: A comprehensive review. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 60, 177823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Review: Machine learning in high-entropy alloys-transformative potential and innovative application. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 12385–12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, B.; Chen, R.; He, J.; Kang, D.; Dai, J. Computational simulation of short-range order structures in high-entropy alloys: A review on formation patterns, multiscale characterization, and performance modulation mechanisms. Adv. Phys. X 2025, 10, 2527417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liaw, P.K.; Yang, T. Machine Learning-Based Computational Design Methods for High-Entropy Alloys. High Entropy Alloys Mater. 2025, 3, 41–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechtl, J.; Liaw, P.K. (Eds.) High-Entropy Materials: Theory, Experiments, and Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, I.; Lakhouaja, A. Data science in light of natural language processing: An overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 127, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souili, A.; Cavallucci, D.; Rousselot, F. Natural Language Processing (NLP)–A Solution for Knowledge Extraction from Patent Unstructured Data. Procedia Eng. 2015, 131, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, P.; Varoquaux, G.; K’egl, B. Similarity encoding for learning with dirty categorical variables. Mach. Learn. 2018, 107, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.Q.; Pan, S.P.; Zhang, Y.; Liaw, P.K.; Qiao, J.W. Structure prediction in high-entropy alloys with machine learning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 231904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Xu, T.; Wei, X.; Ding, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Using machine learning and feature engineering to characterize limited material datasets of high-entropy alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 175, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Krzywinski, M.; Altman, N. Machine learning: A primer. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1119–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Xu, X.; Pei, X.; Duan, Z.; Liaw, P.K.; Hou, H.; Zhao, Y. Predict the phase formation of high-entropy alloys by compositions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3331–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Ren, W.; Wang, W.-L.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Li, X.-M.; Li, W.-H. VInterpretable hardness prediction of high-entropy alloys through ensemble learning. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 945, 169329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Tung, P.-Y.; Xie, R.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ferrari, A.; Klaver, T.P.C.; Körmann, F.; Sukumar, P.T.; Kwiatkowski da Silva, A.; et al. Machine learning–enabled high-entropy alloy discovery. Science 2022, 378, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareharen, K.; Panneerselvam, T.; Raj Mohan, R. Improving the performance of machine learning model predicting phase and crystal structure of high entropy alloys by the synthetic minority oversampling technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 991, 174494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liaw, P.K.; Ren, J. Phase prediction of high-entropy alloys based on machine learning and an improved information fusion approach. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 239, 112976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeresham, M.; Sake, N.; Lee, U.; Park, N. Unraveling phase prediction in high entropy alloys: A synergy of machine learning, deep learning, and ThermoCalc, validation by experimental analysis. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1744–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Kompella, L.; Sanagavarapu, L.M.; Varam, S. Ensemble-based machine learning models for phase prediction in high entropy alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 210, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Su, Y.; Cui, H. Data-driven based phase constitution prediction in high entropy alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 215, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peivaste, I.; Jossou, E.; Tiamiyu, A.A. Data-driven analysis and prediction of stable phases for high-entropy alloy design. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñate, A.; Sanhueza, J.P.; Zegpi, D.; Tuninetti, V.; Ramirez, J.; Medina, C.; Melendrez, M.; Rojas, D. Supervised machine learning-based multi-class phase prediction in high-entropy alloys using robust databases. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 962, 171224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Zhuang, H. Quantum machine-learning phase prediction of high-entropy alloys. Mater. Today 2023, 63, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Martin, P.; Zhuang, H.L. Machine-learning phase prediction of high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2019, 169, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, Y.V.; Jaiswal, U.K.; Rahul, R.M. Machine learning approach to predict new multiphase high entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 2021, 197, 113804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, Q.; Ding, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, Y. Machine learning guided appraisal and exploration of phase design for high entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Huo, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Ren, K.; Tan, S.; Fang, F.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, J. Phase formation prediction of high-entropy alloys: A deep learning study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Complex multiphase predicting of additive manufactured high entropy alloys based on data augmentation deep learning. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 2388–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, D.; Neigapula, V.S.N. Prediction of phase via machine learning in high entropy alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Tao, Y.; Liaw, P.K.; Ren, J. Phase prediction and effect of intrinsic residual strain on phase stability in high-entropy alloys with machine learning. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 921, 166149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Han, T.; Liao, M.; Lai, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Machine learning guided phase formation prediction of high entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risal, S.; Zhu, W.; Guillen, P.; Sun, L. Improving phase prediction accuracy for high entropy alloys with Machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 192, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbili, R.; Ramakrishna, B. Prediction of phases in high entropy alloys using machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, F.; Diao, H.; Gao, M.C.; Tang, Z.; Poplawsky, J.D.; Liaw, P.K. Understanding phase stability of Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 2016, 109, 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.-O.; Helander, T.; Höglund, L.; Shi, P.; Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, computational tools for materials science. Calphad 2002, 26, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raturi, A.; Aditya, J.; Gurao, N.P.; Biswas, K. ICME approach to explore equiatomic and non-equiatomic single phase BCC refractory high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 806, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.; Guo, S.; Luan, J.; Shi, S.; Liu, C. Entropy-driven phase stability and slow diffusion kinetics in an Al0.5CoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 2012, 31, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Yao, M.; Pradeep, K.; Tasan, C.C.; Springer, H.; Raabe, D. Phase stability of non-equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2015, 98, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. The phase selection via machine learning in high entropy alloys. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 37, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Man, M.; Bai, K.; Zhang, Y.-W. Revealing high-fidelity phase selection rules for high entropy alloys: A combined CALPHAD and machine learning study. Mater. Des. 2021, 202, 109532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Chen, T.; Zhou, X. Design of BCC/FCC dual-solid solution refractory high-entropy alloys through CALPHAD, machine learning and experimental methods. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Guo, X.; Deng, Y. A novel method for combining conflicting evidences based on information entropy. Appl. Intell. 2016, 46, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Sun, M.; Bai, M.; Lin, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, W. A hybrid prediction frame for HEAs based on empirical knowledge and machine learning. Acta Mater. 2022, 228, 117742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamankar, S.; Jiang, S.; Webb, M.A. Accelerating multicomponent phase-coexistence calculations with physics-informed neural networks. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2025, 10, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, R.; Mondal, S. Advancements in thermochemical predictions: A multi-output thermodynamics-informed neural network approach. J. Cheminform. 2025, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittig, J.G.; Mitsos, A. Thermodynamics-consistent graph neural networks. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 18504–18512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, G.; Du, S.; Politowicz, A.; Emory, J.P.; Yang, X.; Gautam, A.; Gupta, G.; Li, Z.; Jacobs, R.; Morgan, D. Calibration after bootstrap for accurate uncertainty quantification in regression models. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Rubungo, A.N.; Lei, X.; Persaud, D.; Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Dieng, A.B.; Hattrick-Simpers, J. Probing out-of-distribution generalization in machine learning for materials. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sarıtürk, D.; Arróyave, R. Accelerating CALPHAD-based phase diagram predictions in complex alloys using universal machine learning potentials: Opportunities and challenges. Acta Mater. 2025, 286, 120747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, C.; Hao, C.; Lu, K.; Wang, Z. Stacking ensemble learning assisted design of Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr lightweight high-entropy alloys with high hardness. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Jain, R.; Dewangan, S.; Bhowmik, A.A. Machine learning perspective on hardness prediction in multicomponent Al-Mg based lightweight alloys. Mater. Lett. 2024, 365, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, M.H.; Tsai, M.H.; Wang, W.R.; Lin, S.J.; Yeh, J.W. Microstructure and wear behavior of AlxCo1.5CrFeNi1.5Tiy high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 6308–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.P.; Dong, Y.; Guo, S.; Jiang, L.; Kang, H.J.; Wang, T.M.; Wen, B.; Wang, Z.J.; Jie, J.C.; Cao, Z.Q.; et al. A promising new class of high-temperature alloys: Eutectic high-entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 2014, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Nieh, T. Friction and wear behavior of a single-phase equiatomic TiZrHfNb high-entropy alloy studied using a nanoscratch technique. Acta Mater. 2018, 147, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Nation, B.L.; Wellington-Johnson, J.A.; Curry, J.F.; Kustas, A.B.; Lu, P.; Chandross, M.; Argibay, N. Evidence of Inverse Hall-Petch Behavior and Low Friction and Wear in High Entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Lang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y. Study on corrosion behavior of (CuZnMnNi)100 xSnx high-entropy brass alloy in 5 wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 921, 166051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Sohn, S.S.; Lu, W.J.; Li, L.L.; Li, X.G.; Soundararajan, C.K.; Krieger, W.; Li, Z.M.; Raabe, D. A strong and ductile medium-entropy alloy resists hydrogen embrittlement and corrosion. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, R.; Rogal, Ł.; Dąbek, J.; Wójcik-Bania, M.; Przybylski, K. High temperature oxidation behaviour of non-equimolar AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloys. Vacuum 2021, 184, 109969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.N.; Walley, S.M. The Hall–Petch and inverse Hall–Petch relations and the hardness of nanocrystalline metals. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 55, 2661–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Pan, Y.; Hou, H.; Zhao, Y. Predicting the hardness of high-entropy alloys based on compositions. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 112, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ren, C.; Jia, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, M.; Lu, W. A machine learning-based alloy design system to facilitate the rational design of high entropy alloys with enhanced hardness. Acta Mater. 2022, 222, 117431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Gao, J.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L. Data-driven design of novel lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys with superb hardness and corrosion resistance. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundela, A.S.; Rahul, M.R. Machine learning-enabled framework for the prediction of mechanical properties in new high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908, 164578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Samal, S.; Kumar, V. Development of an ANN-based generalized model for hardness prediction of SPSed AlCoCrCuFeMnNiW containing high entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Hardness prediction of high entropy alloys with periodic table representation of composition, processing, structure and physical parameters. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 967, 171735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jin, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Fu, H. Machine learning assisted modelling and design of solid solution hardened high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 2021, 211, 110177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy cantor alloys. Prog. Mater Sci. 2020, 120, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Miller, J.D.; Miracle, D.B.; Woodward, C. Accelerated exploration of multi-principal element alloys with solid solution phases. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda-Caraballo, I.; Rivera-Díaz-del Castillo, P.E.J. Modelling solid solution hardening in high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2015, 85, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda-Caraballo, I. A general formulation for solid solution hardening effect in multicomponent alloys. Scr. Mater. 2017, 127, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Diao, H.; Lee, C.; Samaei, A.T.; Phan, T.; de Jong, M.; An, K.; Ma, D.; Liaw, P.K.; Chen, W. First-principles and machine learning predictions of elasticity in severely lattice-distorted high-entropy alloys with experimental validation. Acta Mater. 2019, 181, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandavalli, M.; Agarwal, A.; Poonia, A.; Kishor, M.; Ayyagari, K.P.R. Design of high bulk moduli high entropy alloys using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yan, B. First-principles calculations for topological quantum materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bai, S.; Chong, K.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Zou, Y. Machine learning accelerated design of non-equiatomic refractory high entropy alloys based on first principles calculation. Vacuum 2023, 207, 111608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qian, K.; Huang, J.; Liu, M.; Shibuta, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation and machine learning of mechanical response in non-equiatomic FeCrNiCoMn high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. Jul. 2021, 13, 2043–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Z. Composition optimization of AlFeCuSiMg alloys based on elastic modules: A combination method of machine learning and molecular dynamics simulation. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, G.; Singh, P.; Sauceda, D.; Couperthwaite, R.; Britt, N.; Youssef, K.; Johnson, D.D.; Arróyave, R. Efficient machine-learning model for fast assessment of elastic properties of high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 232, 117924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, C.; Kim, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Composition design of high-entropy alloys with deep sets learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pradeep, K.G.; Deng, Y.; Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strengtheductility trade-off. Nature 2016, 534, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Hui, X.; Wu, Y.; Gault, B.; Kontis, P.; et al. Enhanced strength and ductility in a high-entropy alloy via ordered oxygen complexes. Nature 2018, 563, 546e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; He, Z.; Ge, M.; Che, L.; Zheng, K.; Si, T.; Zhao, F. Composition design and optimization of Fe–C–Mn–Al steel based on machine learning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 8219–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, S.; Gu, L.; Wei, F.; Bei, H.; Gao, Y.; et al. Tuning element distribution, structure and properties by composition in high-entropy alloys. Nature 2019, 574, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgack, O.; Almomani, B.; Syarif, J.; Elazab, M.; Irshaid, M.; Al-Shabi, M. Molecular dynamics simulation and machine learning-based analysis for predicting tensile properties of high-entropy FeNiCrCoCu alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 5575–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, D.; Xiao, H.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, L.; et al. Prediction of phase and tensile properties of selective laser melting manufactured high entropy alloys by machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fang, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Liaw, P.K. Lattice-distortion dependent yield strength in high entropy alloys. Mater Sci. Eng. A. 2020, 784, 139323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingrimsson, B.; Fan, X.; Feng, R.; Liaw, P. A physics-based machine-learning approach for modeling the temperature-dependent yield strengths of medium- or high-entropy alloys. Appl. Mater. Today 2023, 31, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeresham, M.; Jain, R.; Lee, U.; Park, N. Machine learning approach for predicting yield strength of nitrogen-doped CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloys at selective thermomechanical processing conditions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 2621–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, W.; Weng, X.; Chen, J. A yield strength prediction framework for refractory high-entropy alloys based on machine learning. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 125, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, U.; Rafi Md, R.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S. Yield strength prediction of high-entropy alloys using machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 26, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xue, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Gao, S.; Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; et al. Machine-learning design of ductile FeNiCoAlTa alloys with high strength. Nature 2025, 643, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, M. Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Huang, T.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, C. Enhancing antioxidant properties of hydrogen storage alloys using PMMA coating. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 4339–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Sun, A.; Yang, S.; Yu, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, L.; Song, J.; Wang, D.; Kang, Y. Machine learning-assisted discovery of Cr, Al-containing high-entropy alloys for high oxidation resistance. Corros. Sci. 2023, 220, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Song, X.; Duan, Z.; Hao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Han, Y.; Ran, X.; Liu, Y. Improving the high-temperature ductility of γ-TiAl matrix composites by incorporation of AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy particles. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1012, 178515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.L.; Xu, J.L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.W.; Luo, J.M. Wear Resistance of N-Doped CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Coating on the Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2024, 33, 2408–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Jain, S.; Nagarjuna, C.; Samal, S.; Rananavare, A.P.; Dewangan, S.K.; Ahn, B. A Comprehensive Review on Hot Deformation Behavior of High-Entropy Alloys for High Temperature Applications. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 31, 2181–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lu, D.; Wang, K. Accelerated discovery of single-phase refractory high entropy alloys assisted by machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 199, 110723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birbilis, N.; Choudhary, S.; Scully, J.R.; Taheri, M.L. A perspective on corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 2021, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, H.; Du, C.W.; Li, X.G. Recent advances on environmental corrosion behavior and mechanism of high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 80, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Thomas, S.; Gibson, M.A.; Fraser, H.L.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion of high entropy alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 2017, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, H.; Nazarahari, A.; Yilmaz, B.; Canadinc, D.; Bedir, E.; Yilmaz, R.; Unal, U.; Maier, H. Machine learning–Informed development of high entropy alloys with enhanced corrosion resistance. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 476, 143722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepski, P.; Szocinski, M.; Lentka, G.; Darowicki, K. Novel fast non-linear electrochemical impedance method for corrosion investigations. Measurement 2021, 173, 108667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S. Study of electrochemical corrosion on Q235A steel under stray current excitation using combined analysis by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and artificial neural network, Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Xu, J.; Pang, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, J.; Cai, Z.; Yan, M.; Sun, C. Prediction of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of high-entropy alloys corrosion by using gradient boosting decision tree. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Rahul, M.R.; Chakraborty, P.; Sabat, R.K.; Samal, S.; Park, N.; Phanikumar, G.; Tewari, R. Integrated experimental and modeling approach for hot deformation behavior of Co–Cr–Fe–Ni–V high entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Jain, R.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Jain, S.; Paswan, M.; Samal, S.; Ahn, B. Enhancing flow stress predictions in CoCrFeNiV high entropy alloy with conventional and machine learning techniques. J. Mater. Res. Technol. Jmrt 2024, 30, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Lee, H.; Kumar, V.; Ahn, B. Prediction of nanoindentation creep behavior of tungsten-containing high entropy alloys using artificial neural network trained with Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 958, 170359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Jain, R.; Rao, K.R.; Bhowmik, A. Leveraging machine learning to minimize experimental trials and predict hot deformation behaviour in dual phase high entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Jain, S.; Dewangan, S.K.; Rahul, M.R.; Samal, S.; Song, E.; Lee, Y.; Jeon, Y.; Biswas, K.; Phanikumar, G.; et al. Machine-learning-driven prediction of flow curves and development of processing maps for hot-deformed Ni–Cu–Co–Ti–Ta alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 7447–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.; Ge, M.; Si, T.; Che, L.; Zheng, K.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Q. Machine learning guided BCC or FCC phase prediction in high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. Jmrt 2024, 29, 3477–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Sun, Z.; Tu, J.; Wu, W.; Yang, H. Intelligent design of Fe–Cr–Ni–Al/Ti multi-principal element alloys based on machine learning. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 6864–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ma, D.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z. High-throughput and data-driven machine learning techniques for discovering high-entropy alloys. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Lookman, T.; Yuan, R. Closed-loop inverse design of high entropy alloys using symbolic regression-oriented optimization. Mater. Today 2025, 88, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Tao, X.; Cai, H.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Du, Y. Machine learning reveals the importance of the formation enthalpy and atom-size difference in forming phases of high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 193, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, U.K.; Vamsi Krishna, Y.; Rahul, M.R.; Phanikumar, G. Machine learning-enabled identification of new medium to high entropy alloys with solid solution phases. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 197, 110623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, J.; Elbeltagy, M.B.; Nassif, A.B. A machine learning framework for discovering high entropy alloys phase formation drivers. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, J.; Ma, S.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, S.; Kai, J.J.; Zhao, S. Revealing the crucial role of rough energy landscape on self-diffusion in high-entropy alloys based on machine learning and kinetic Monte Carlo. Acta Mater. 2022, 234, 118051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Farkas, D.; Bai, X.-M. High-throughput machine learning-Kinetic Monte Carlo framework for diffusion studies in Equiatomic and Non-equiatomic FeNiCrCoCu high-entropy alloys. Materialia 2023, 32, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W.; Niu, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y. Machine-learning-assisted discovery of highly efficient high-entropy alloy catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Patterns 2022, 3, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xiao, X.; Huang, L.; Tan, L.; Liu, Y. Design of NiCoCrAl eutectic high entropy alloys by combining machine learning with CALPHAD method. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 30, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jiang, B.; Song, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Si, D.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, C.; Liu, P.; et al. Machine learning assisted design of high-entropy alloys with ultra-high microhardness and unexpected low density. Mater. Des. 2024, 238, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, K.; Zhao, L.; Liang, S.; Huang, M.; Li, Z. A statistics-based study and machine-learning of stacking fault energies in HEAs. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 966, 171547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, C.; Dang, P.; Jiang, X.; Xue, D.; Su, Y. Elemental numerical descriptions to enhance classification and regression model performance for high-entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Zhang, T.; Lu, W.; Qian, Q.; Low, J.S.; Yune, J.H.; Tan, D.Z.; Bressan, S.; Sanvito, S.; Kalidindi, S.R. Materials informatics. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 30, 2307–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lookman, T.; Balachandran, P.V.; Xue, D.; Yuan, R. Active learning in materials science with emphasis on adaptive sampling using uncertainties for targeted design. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Cao, B.; Deng, L.; Sun, A.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, T.-Y. Discovering a formula for the high temperature oxidation behavior of FeCrAlCoNi based high entropy alloys by domain knowledge-guided machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 149, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zheng, L.; Xu, H.; Fu, H. Predicting and understanding the ductility of BCC high entropy alloys via knowledge-integrated machine learning. Mater. Des. 2024, 239, 112797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014, Banff, AB, Canada, 14–16 April 2014. Conference Track Proceedings. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetto, A.; Grant, E.; Strelchuk, S.; Carleo, G.; Severini, S. Learning hard quantum distributions with variational autoencoders. npj Quantum Inf. 2018, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Pei, Z.; Gao, M.C. Neural network-based order parameter for phase transitions and its applications in high-entropy alloys. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2021, 1, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, J.E.; Berglund, I.S.; Sebastian, J.T.; Liaw, P.K.; Olson, G.B. Equilibrium high entropy alloy phase stability from experiments and thermodynamic modeling. Scr. Mater. 2018, 146, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, Y. Harnessing machine learning for high-entropy alloy catalysis: A focus on adsorption energy prediction. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.; Vecchio, K.S. Searching for high entropy alloys: A machine learning approach. Acta Mater. 2020, 198, 178–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Duan, P.; Ghamisi, P.; Filip, F.; Band, S.S.; Reuter, U.; Gama, J.; Gandomi, A.H. Data science in economics: Comprehensive review of advanced machine learning and deep learning methods. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hou, B.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J. Machine learning and artificial neural network accelerated computational discoveries in materials science. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10, e1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H. Neural networks and information in materials science. Stat. Anal. Data Min. ASA Data Sci. J. 2009, 1, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kwon, H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, B.-J. A neural network model for high entropy alloy design. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ye, Y.; Yang, Y. The configurational entropy of mixing of metastable random solid solution in complex multicomponent alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 154902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Su, R.; Hu, Y.-C.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Guan, P. Common mechanism for controlling polymorph selection during crystallization in supercooled metallic liquids. Acta Mater. 2018, 161, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ding, Z.; Ye, Y.; Yang, Y. Design of high-entropy alloy: A perspective from nonideal mixing. Jom 2017, 69, 2092–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillinger, F.H. A topographic view of supercooled liquids and glass formation. Science 1995, 267, 1935–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debenedetti, P.G.; Stillinger, F.H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 2001, 410, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, G.; Chakravarty, S.; Gurrola, R.; Arróyave, R. A deep neural network regressor for phase constitution estimation in the high entropy alloy system Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Nb-Ni. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y.; Jui, C.-Y.; Yeh, A.-C.; Chang, Y.-J.; Lee, W.-J. Inverse design of high entropy alloys using a deep interpretable scheme for materials attribution analysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, P.V.; Kowalski, B.; Sehirlioglu, A.; Lookman, T. Experimental search for high-temperature ferroelectric perovskites guided by two-step machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernatis, J.E.; Lookman, T. Machine learning in materials design and discovery: Examples from the present and suggestions for the future. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 120301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Balachandran, P.V.; Hogden, J.; Theiler, J.; Xue, D.; Lookman, T. Accelerated search for materials with targeted properties by adaptive design. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Liu, Z.; Balachandran, P.V.; Xue, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, X.; Sun, J.; Xue, D.; Lookman, T. Accelerated Discovery of Large Electrostrains in BaTiO3 -Based Piezoelectrics Using Active Learning. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1702884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yuan, R.; Liang, H.; Wang, W.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Towards high entropy alloy with enhanced strength and ductility using domain knowledge constrained active learning. Mater. Des. 2022, 223, 111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Liaw, P.K. Promising properties and future trend of eutectic high entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 2020, 187, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Zheng, T.; Yang, Z.; He, F.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Uncovering the eutectics design by machine learning in the Al–Co–Cr–Fe–Ni high entropy system. Acta Mater. 2020, 182, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Man, M.; Koon Ng, C.; Aitken, Z.; Bai, K.; Wuu, D.; Jun Lee, J.; Rong Ng, S.; Wei, F.; Wang, P.; et al. Search for eutectic high entropy alloys by integrating high-throughput CALPHAD, machine learning and experiments. Mater. Des. 2024, 241, 112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, W.; Jain, S.; Jung, D.; Lee, J. Optimization of flow behavior models by genetic algorithm: A case study of aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3349–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalewicz, Z.; Schoenauer, M. Evolutionary Algorithms for Constrained Parameter Optimization Problems. Evol. Comput. 1996, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.T.; Davies, D.W.; Cartwright, H.; Isayev, O.; Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raccuglia, P.; Elbert, K.; Adler, P.D.F.; Falk, C.; Wenny, M.; Mollo, A.; Zeller, M.; Friedler, S.A.; Schrier, J.; Norquist, A. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 2016, 533, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, C.; Wang, C.; Antonov, S.; Xue, D.; Bai, Y.; Su, Y. Phase prediction in high entropy alloys with a rational selection of materials descriptors and machine learning models. Acta Mater. 2020, 185, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, D.; Zou, R.; Yang, Z. Hardness prediction of high entropy alloys with machine learning and material descriptors selection by improved genetic algorithm. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 205, 111185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative Adversarial Networks: An Overview. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousmalis, K.; Silberman, N.; Dohan, D.; Erhan, D.; Krishnan, D. Unsupervised pixel-level domain adaptation with generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Byeon, S.; Kim, H.S.; Jin, H.; Lee, S. Deep learning-based phase prediction of high-entropy alloys: Optimization, generation, and explanation. Mater. Des. 2021, 197, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, D. A two-step data augmentation method based on generative adversarial network for hardness prediction of high entropy alloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 220, 112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, C.; Tran, N.-D.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ni, J. EFTGAN: Elemental features and transferring corrected data augmentation for the study of high-entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Qu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; You, J.; Su, R. Phase selection and mechanical properties of (Al21.7Cr15.8Fe28.6Ni33.9)x(Al9.4Cr19.7Fe41.4Ni29.5)100–x high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 751, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.E.; Mullis, A.M. Rapid screening of high-entropy alloys using neural networks and constituent elements. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 199, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Kauffmann, A.; Laube, S.; Choi, I.-C.; Schwaiger, R.; Huang, Y.; Lichtenberg, K.; Müller, F.; Gorr, B.; Christ, H.-J.; et al. Contribution of lattice distortion to solid solution strengthening in a series of refractory high entropy alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2017, 49, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, R.L. Substitutional solid solution hardening of titanium. Scr. Metall. 1987, 21, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labusch, R. A statistical theory of solid solution hardening. Phys. Status Solidi 1970, 41, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Antonov, S.; Xue, D.; Lookman, T.; Su, Y. Modeling solid solution strengthening in high entropy alloys using machine learning. Acta Mater. 2021, 212, 116917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, K. Bayesian Optimization. In Many-Criteria Optimization and Decision Analysis; Brockhoff, D., Emmerich, M., Naujoks, B., Purshouse, R., Eds.; Natural Computing Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, B.; Khatamsaz, D.; Acemi, C.; Karaman, I.; Arróyave, R. Data-augmented modeling for yield strength of refractory high entropy alloys: A Bayesian approach. Acta Mater. 2023, 261, 119351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatamsaz, D.; Vela, B.; Singh, P.; Johnson, D.D.; Allaire, D.; Arróyave, R. Multi-objective materials bayesian optimization with active learning of design constraints: Design of ductile refractory multi-principal-element alloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 236, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, B. Uncertainty quantification of predicting stable structures for high-entropy alloys using Bayesian neural networks. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 81, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulley, G.A.; Raush, J.; Montemore, M.M.; Hamm, J. Accelerating high-entropy alloy discovery: Efficient exploration via active learning. Scr. Mater. 2024, 249, 116180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpren, E.; Yao, X.; Chen, Z.W.; Singh, C.V. Machine learning assisted design of BCC high entropy alloys for room temperature hydrogen storage. Acta Mater. 2024, 270, 119841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Gotovos, A.; Burdick, J.W.; Krause, A. Bayesian optimization with active learning of design constraints using an entropy-based approach. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 1539–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wang, W.-L.; Ding, S.-J.; Li, N. Prediction and design of high hardness high entropy alloy through machine learning. Mater. Des. 2023, 235, 112454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Li, C.; Pan, H.; Ding, W.; Yu, J. Accelerated design of low-activation high entropy alloys with desired phase and property by machine learning. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 36, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Quek, X.K.; Suo, H.; Wuu, D.; Lee, J.J.; Teh, W.H.; Wei, F.; Made, R.I.; Tan, D.C.C.; Ng, S.R.; et al. Composition driven machine learning for unearthing high-strength lightweight multi-principal element alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2024, 1008, 176517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Shang, C.; Ran, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhang, X.; Nie, M.; Xu, W.; Lu, X. Reinforcement Learning in Materials Science: Recent Advances, Methodologies and Applications. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2025, 11, 2077–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Trehern, W.; Sundar, A.; Wang, Y.; San, S.; Lu, T.; Zhou, F.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, Y.; et al. Machine learning and high-throughput computational guided development of high temperature oxidation-resisting Ni-Co-Cr-Al-Fe based high-entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daulton, S.; Eriksson, D.; Balandat, M.; Bakshy, E. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization over high-dimensional search spaces. In Proceedings of the 38th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1–5 August 2022; PMLR: Breckenridge, CO, USA; Volume 180, pp. 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, C.; Marzolf, B. BoTorch: A framework for efficient Monte-Carlo Bayesian optimization. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 13–18 July 2020; Volume 119, pp. 3409–3418. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G.; Yao, A.; Song, D.; Abbeel, P.; Darrell, T.; Harari, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Xue, L.; Shalev-Shwartz, S.; et al. Managing extreme AI risks amid rapid progress. Science 2024, 384, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Cheng, X. Machine learning-assisted design of refractory high-entropy alloys with targeted yield strength and fracture strain. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Pei, J.; Hou, H.; Zhao, Y. Optimizing casting process using a combination of small data machine learning and phase-field simulations. Npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Zhu, J. Cuckoo search-artificial neural network aided the composition design in Al–Cr–Co–Fe–Ni high entropy alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 669, 160539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Wu, Y.; Lookman, T.; Su, Y. Machine-Learning-Assisted Compositional Design of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys with Optimal Strength and Ductility. Engineering 2024, 46, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S. Feature selection in machine learning: A new perspective. Neurocomputing 2018, 300, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Huang, J.; Xie, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Gao, T. Machine learning-based phase prediction in high-entropy alloys: Further optimization of feature engineering. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 3999–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Shen, H.; Tian, Y.; Lou, G.; Wang, N.; Su, Y. Accelerated discovery of refractory high-entropy alloys for strength-ductility co-optimization: An exploration in NbTaZrHfMo system by machine learning. Scr. Mater. 2024, 252, 116240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, A.N.; Bates, S.; Fannjiang, C.; Jordan, M.I.; Zrnic, T. Prediction-powered inference. Science 2023, 382, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, A.; Wang, Q.; Ganose, A.; Dopp, D.; Jain, A. Benchmarking materials property prediction methods: The Matbench test set and Automatminer reference algorithm. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Target | ML Algorithms | Dataset & Performance | Refs | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hareharen et al. | Phase | DT, KNN, RF, GB, XGBoosting | 84.0% accuracy | [45] | 2024 |

| Veeresham et al. | Phase | KNN, bagging, adaboost, DT, extra trees, and ANN | ANN 90.62% accuracy; extra trees 89.73% accuracy | [47] | 2024 |

| Jain et al. | thermal deformation behavior | ANN | R = 0.9983 | [135] | 2023 |

| Dewangan et al. | flow stress | BR, EN, LR, RF, GBoosting, SV, RR, PR | R2 = 0.994, MAE = 7.77%, RMSE = 9.7% | [136] | 2024 |

| Dewangan et al. | the room temperature creep behavior | ANN | The ANN model can accurately forecast the room temperature creep behavior of HEAs | [137] | 2023 |

| Wu et al. | thermal deformation behavior | RF, KNN, XGBoost, DT and SVR | Predicted flow stress behavior of dual FCC phase CoCrCu1.2FeNi high entropy alloy (HEA) at new temperatures and strain rates | [138] | 2024 |

| Jain et al. | flow curves | RF, XGBoost, DT, KNN and GB | R2 = 0.97, RMSE = 10.1%, and MAE = 8.9% | [139] | 2025 |

| He et al. | Phase | KNN, SVM, DT, RF, LR | 399 date, 87.0% accuracy | [140] | 2024 |

| Zhou et al. | structural energy | NN | root mean squared error of the energy predicted is 1.37 meV/atom | [141] | 2023 |

| Author | Target | Algorithms | Results | Refs | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. | find HEAs with high hardness | RF, PSO | Obtained a HEA with an average hardness value of 966 HV, which is higher than that of the existing alloys in the AlCoCrCuFeNi system | [143] | 2023 |

| Zhao et al. | design of HEAs with ultra-high microhardness and unexpected low density | GAN, AL, XGBoost | Four Al-rich compositions exhibit ultra-high microhardness (>740 HV, with a maximum of ~780.3 HV) and low density (<5.9 g/cm3) in the as-cast bulk state. | [151] | 2024 |

| Xu et al. | represent the local atomic environment dependence of PEL in HEAs | NN, KMC | TixZr2−xCrMnFeNi (x = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5) hydride formation enthalpy of −25 to −39 kJ/mol is designed for hydrogen storage at room temperature. | [147] | 2022 |

| Rao et al. | to accelerate the design of high-entropy Invar alloys | DFT, AL, WAE | identified two high-entropy Invar alloys with extremely low thermal expansion coefficients around 2 × 10−6 per degree kelvin at 300 kelvin | [44] | 2022 |

| Wei et al. | aims at the discovery of a thematical formula | XGBoost, SHAP | performed a domain knowledge-guided machine learning to discover high interpretive formula describing the high- temperature oxidation behavior of FeCrAlCoNi-based high entropy alloys (HEAs) | [156] | 2023 |

| Sulley et al. | exploration of the complex composition space | NN, AL | Active learning can through an iterative search process and hence reducing the expense of exploring the entire design space | [205] | 2024 |

| Yin et al. | find a representative order parameter | VAE, CNN | Coined a new concept of “VAE order parameter” | [160] | 2021 |

| Wang et al. | Developed a neural network model to search vast compositional space of HEAs | DNN, CNN | Two HEAs were designed using this model and experimentally verified to have the best combination of strength and ductility. | [167] | 2023 |

| Halpren et al. | design of BCC high entropy alloys for room temperature hydrogen storage | MOBO | Discovered 8 new HEA candidates for hydrogen storage, including the VNbCrMoMn HEA that can store 2.83 wt% hydrogen at room temperature and atmospheric pressure | [206] | 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; He, Z.; Zheng, K.; Che, L.; Feng, W. Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Compositional Space Exploration. Metals 2025, 15, 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121349

Xu X, He Z, Zheng K, Che L, Feng W. Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Compositional Space Exploration. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121349

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiaotian, Zhongping He, Kaiyuan Zheng, Lun Che, and Wei Feng. 2025. "Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Compositional Space Exploration" Metals 15, no. 12: 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121349

APA StyleXu, X., He, Z., Zheng, K., Che, L., & Feng, W. (2025). Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Compositional Space Exploration. Metals, 15(12), 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121349