Laser Cladding of Iron Aluminide Coatings for Surface Protection in Soderberg Electrolytic Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure Characterization

3.2. XRD Analysis

3.3. Microhardness

4. Conclusions

- X-ray diffraction analysis of the iron aluminide Fe3Al track revealed a shift in the peak (110) position at 2θ from 44.7° to 44.2°, indicating the presence of aluminum in the solid Fe-α solution, which was homogeneously distributed. However, the presence of the ordered D03 phase in Fe3Al was not directly identified with X-ray diffractometry analysis a fact attributed to the strong crystallographic texture generated by rapid solidification, its presence is strongly indicated by the microhardness values achieved (approximately 350 HV0.1), distinct from the substrate.

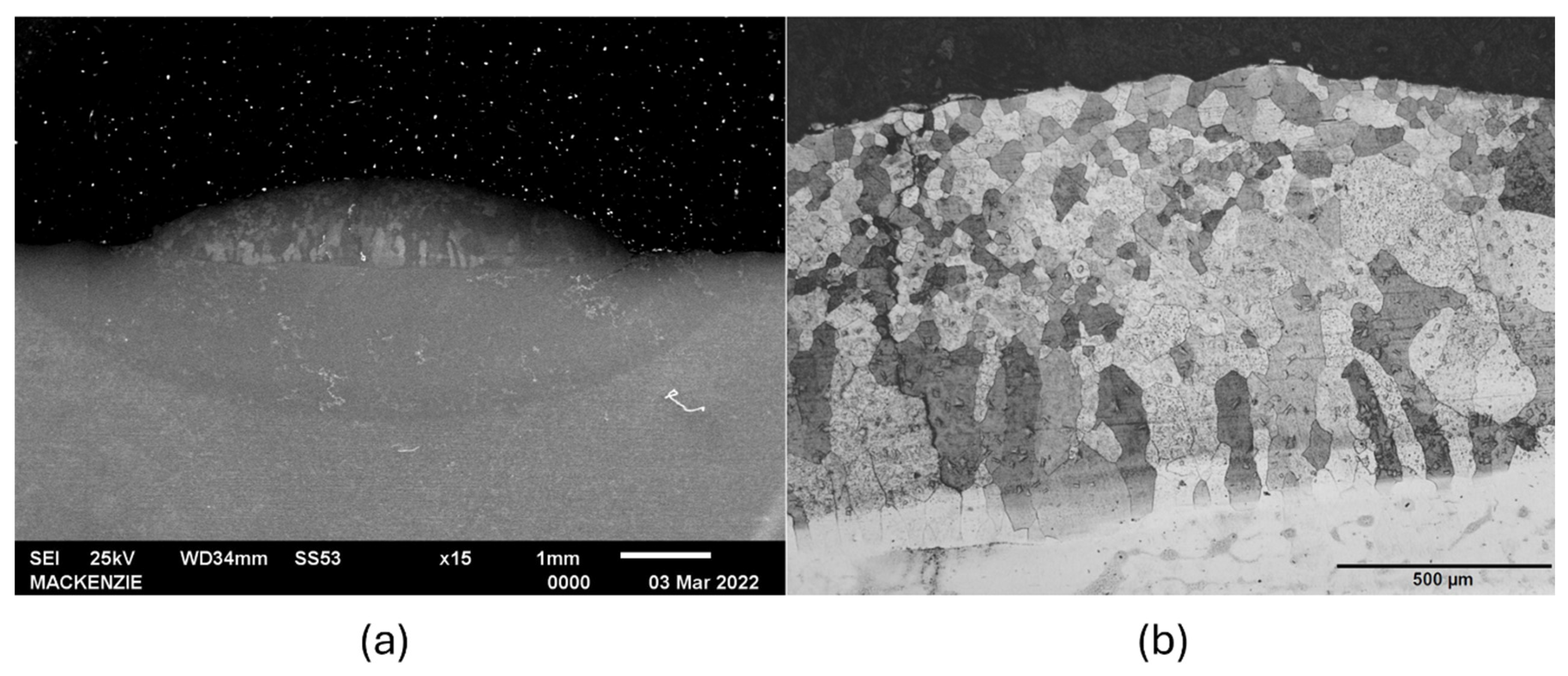

- The micrograph of the Fe3Al iron aluminide tracks shows the presence of columnar grains from the interface region with the substrate, driven by the local temperature gradient, without the precipitation of secondary phase in the cross-section. This solidification condition may have generated a crystallographic texture consistent with the nonappearance of some diffraction peaks of the ordered D03 phase in Fe3Al.

- X-ray diffraction analysis of the FeAl iron aluminides revealed the presence of the ordered structure B2. An increase in the laser power to 4.5, 5.5, and 6.5 kW in the fusion of the tracks increased the diffraction intensity of the (100) plane. This indicated that the higher heat inputs favor a great degree of ordering of the B2 structure. The grain morphology exhibited typical behavior, with columnar grains at the interface with the substrate and equiaxed grains in the upper region of the track. The average microhardness of ~400 HV0.1 confirms the obtaining of the B2 intermetallic phase.

- At 3.5 kW and 3 mm/s, coatings showed homogeneous microstructure and crack-free intermetallic phases, while 6.5 kW at the same speed promoted higher B2 ordering but increased susceptibility to cracking due to greater thermal contraction.

- The coatings produced demonstrated promising potential for application in anodic pins of Soderberg-type electrolytic cells, combining high hardness and microstructural stability. For industrial validation, it is recommended to carry out complementary corrosion, oxidation, adhesion and wear tests. As only small tracks were tested in this work, future studies should address automated deposition and detailed coating thickness measurements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Society for Metals. ASM Handbook: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials; ASM International: Novelty, OH, USA, 2001; Volume 2, ISBN 0871700077. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, A.A. Influência Do Teor de Cromo e de Tratamentos Térmicos Na Microestrutura e No Comportamento Mecânico de Ligas Intermetálicas Ordenadas à Base de Fe3Al; University of São Paulo: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.I.; Couto, A.A.; de Paola, J.C.C. The Effects of Chromium Addition and Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Fe-24Al (at.%). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1995, 192–193, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzade, M.; Barnoush, A.; Motz, H. A Review on the Properties of Iron Aluminide Intermetallics. Crystals 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojacz, H.; Varga, M.; Mayrhofer, P.H. High-Temperature Abrasive Wear Behaviour of Strengthened Iron-Aluminide Laser Claddings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 496, 131585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deevi, S.C. Advanced Intermetallic Iron Aluminide Coatings for High Temperature Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.J.; Jay, A.H. The Formation of Superlattices in Alloys of Iron and Aluminium. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Contain. Pap. A Math. Phys. Character 1932, 136, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.T.; Lee, E.H.; McKamey, C.G. An Environmental Effect as the Major Cause for Room-Temperature Embrittlement in FeAl. Scr. Metall. 1989, 23, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airiskallio, E.; Nurmi, E.; Heinonen, M.H.; Väyrynen, I.J.; Kokko, K.; Ropo, M.; Punkkinen, M.P.J.; Pitkänen, H.; Alatalo, M.; Kollár, J.; et al. High Temperature Oxidation of Fe-Al and Fe-Cr-Al Alloys: The Role of Cr as a Chemically Active Element. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3394–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorelli, P.F.; Natesan, K. Critical Factors Affecting the High-Temperature Corrosion Performance of Iron Aluminides. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 258, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrovatka, V.L.; Umanskiy, A.P.; Yakovlieva, M.S.; Martsenyuk, I.S.; Labunets, V.F. Oxidation Resistance of Iron Aluminide Materials. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2019, 58, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.M. Microstructure and Wear Resistance of Laser Clad TiC Reinforced FeAl Intermetallic Matrix Composite Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 168, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Dubey, A.K. Recent Trends in Laser Cladding and Surface Alloying. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Liu, W. Laser Surface Cladding: The State of the Art and Challenges. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2010, 224, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.; Göbel, M.; Fu, E. Perspectives for Conventional Coating Processes Using High-Speed Laser Cladding. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2022, 144, 044501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Dai, Y.; Deng, B.; Lin, J. Enhancing Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Nickel–Aluminum Bronze through Laser-Cladded Amorphous-Crystalline Composite Coating. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2024, 2, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Hariharasakthisudhan, P.; Katiyar, J.K.; Sathickbasha, K. Advancements in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Manufacturing of Alloy 718: Microstructural Insights and Mechanical Behaviours. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 182631. [Google Scholar]

- Thawari, N.; Gullipalli, C.; Katiyar, J.K.; Gupta, T.V.K. Effect of Multi-Layer Laser Cladding of Stellite 6 and Inconel 718 Materials on Clad Geometry, Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 28, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawari, N.; Gullipalli, C.; Katiyar, J.K.; Gupta, T.V.K. Influence of Buffer Layer on Surface and Tribomechanical Properties of Laser Cladded Stellite 6. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 263, 114799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, J.H.; Rawlings, R.D.; West, D.R.F. Functionally Graded Nickel-Aluminide and Iron-Aluminide Coatings Produced via Laser Cladding. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 5931–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, B.; Schäfer, M.; Pauly, C.; Mücklich, F. Coating and Prototyping of Single-Phase Iron Aluminide by Laser Cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 235, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovrov, V.; Zaikov, Y.; Tsvetov, V.; Shtefanyuk, Y.; Pingin, V.; Golubev, M. Aluminide Coating Application for Protection of Anodic Current-Supplying Pins in Soderberg Electrolytic Cell for Aluminium Production. Mater. Sci. Forum 2017, 900, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, G. Effect of Process Parameters on the Microstructure and Wear Resistance of Fe3Al/Cr3C2 Composites. Coatings 2024, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaei, H.; Amirabdollahian, S.; Menapace, C.; Straffelini, G.; Gialanella, S. Microstructure and Wear Resistance of Fe3Al Coating on Grey Cast Iron Prepared via Direct Energy Deposition. Lubricants 2023, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, D.; Gao, P.; Naumov, A.; Li, Q.; Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Microstructure and Properties of FeAlC-x(WC-Co) Composite Coating Prepared through Plasma Transfer Arc Cladding. Coatings 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, E.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Research Progress on Laser Cladding of Refractory High-Entropy Alloy Coatings. Jinshu Xuebao/Acta Metall. Sin. 2025, 61, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostolaza, M.; Zabala, A.; Arrizubieta, J.I.; Llavori, I.; Otegi, N.; Lamikiz, A. High-Temperature Tribological Performance of Functionally Graded Stellite 6/WC Metal Matrix Composite Coatings Manufactured by Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. Friction 2024, 12, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Dong, S.; Coddet, P.; Liao, H.; Coddet, C. Fabrication and Microstructure Characterization of Selective Laser-melted FeAl Intermetallic Parts. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 4704–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Awasthi, R.; Chandra, K. A Facile Route to Produce Fe–Al Intermetallic Coatings by Laser Surface Alloying. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 2124–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.M. Growth Morphology and Mechanism of Primary TiC Carbide in Laser Clad TiC/FeAl Composite Coating. Mater. Lett. 2003, 57, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Track | Aluminides | Output (kW) | Scan Speed (mm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Fe3Al | 3.5 | 3 |

| 4 | Fe3Al | 3.5 | 3 |

| 5 | FeAl | 3.5 | 3 |

| 6 | FeAl | 3.5 | 3 |

| 7 | Fe3Al | 4.5 | 3 |

| 8 | Fe3Al | 5.5 | 3 |

| 9 | Fe3Al | 6.5 | 3 |

| 10 | FeAl | 4.5 | 3 |

| 11 | FeAl | 5.5 | 3 |

| 12 | FeAl | 6.5 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, A.F.; Santos, H.C.d.; Seno, R.; Francisco, A.; Lima, N.B.d.; Almeida, G.F.C.; Reis, L.; Massi, M.; Couto, A.A. Laser Cladding of Iron Aluminide Coatings for Surface Protection in Soderberg Electrolytic Cells. Metals 2025, 15, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121337

Gomes AF, Santos HCd, Seno R, Francisco A, Lima NBd, Almeida GFC, Reis L, Massi M, Couto AA. Laser Cladding of Iron Aluminide Coatings for Surface Protection in Soderberg Electrolytic Cells. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121337

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Alex Fukunaga, Henrique Correa dos Santos, Roberto Seno, Adriano Francisco, Nelson Batista de Lima, Gisele Fabiane Costa Almeida, Luis Reis, Marcos Massi, and Antonio Augusto Couto. 2025. "Laser Cladding of Iron Aluminide Coatings for Surface Protection in Soderberg Electrolytic Cells" Metals 15, no. 12: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121337

APA StyleGomes, A. F., Santos, H. C. d., Seno, R., Francisco, A., Lima, N. B. d., Almeida, G. F. C., Reis, L., Massi, M., & Couto, A. A. (2025). Laser Cladding of Iron Aluminide Coatings for Surface Protection in Soderberg Electrolytic Cells. Metals, 15(12), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121337