Kinetic Simulation of Gas-Particle Injection into the Molten Lead

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Simulation

2.1. Kinetic Behavior

2.2. Residence Time and Melting Time

2.3. Hydrodynamic Model Summary

2.4. Validation Metric

3. Results and Discussion

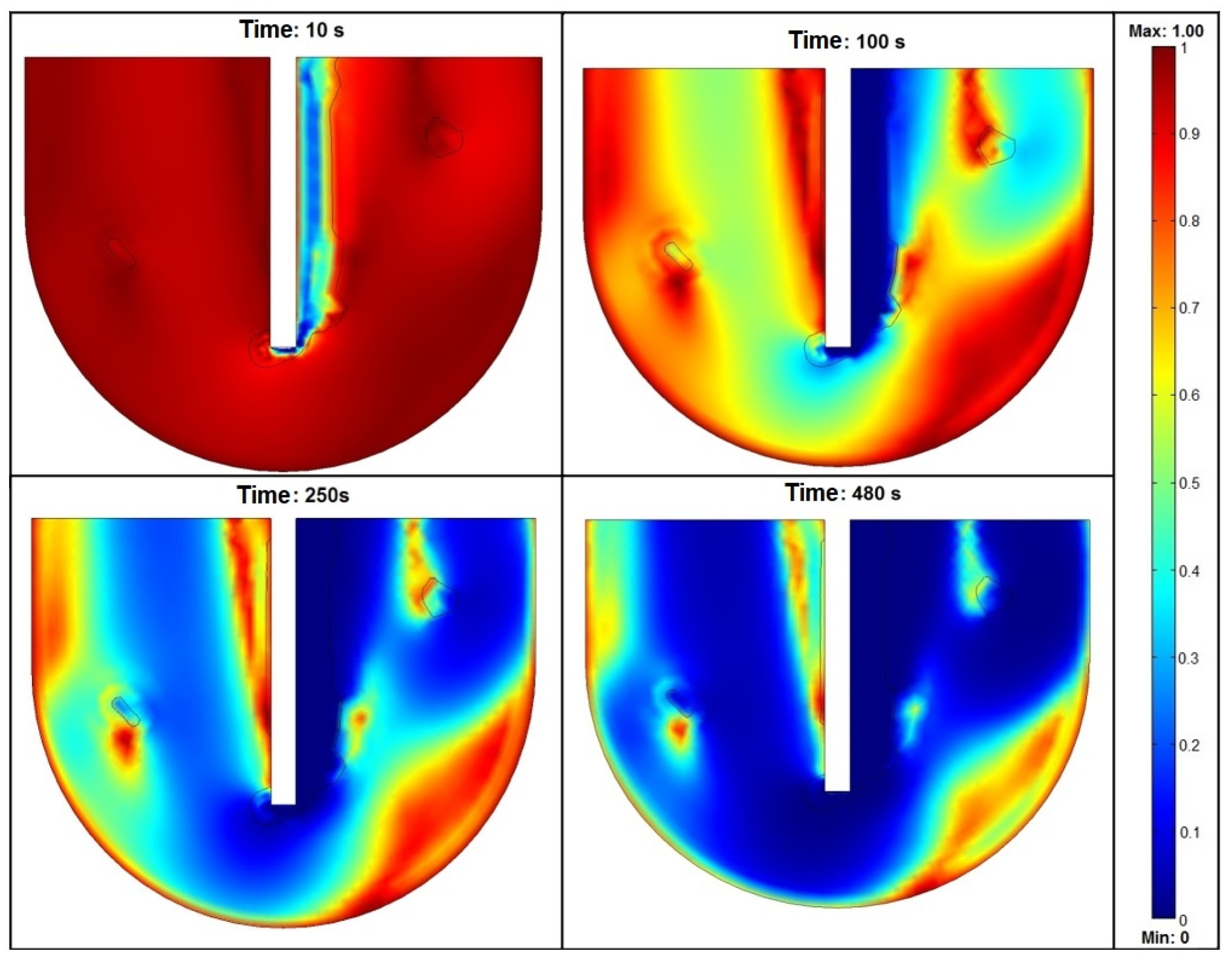

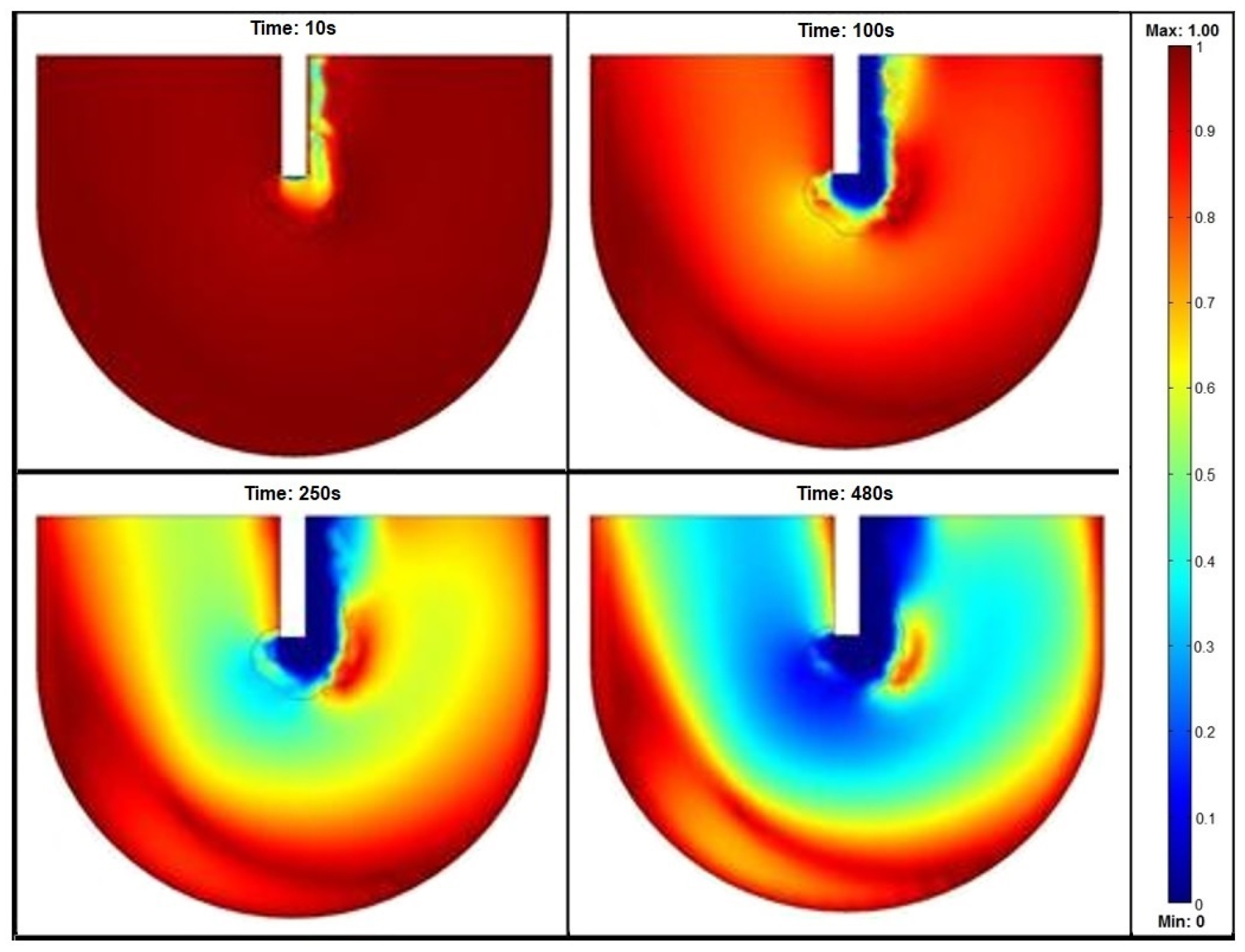

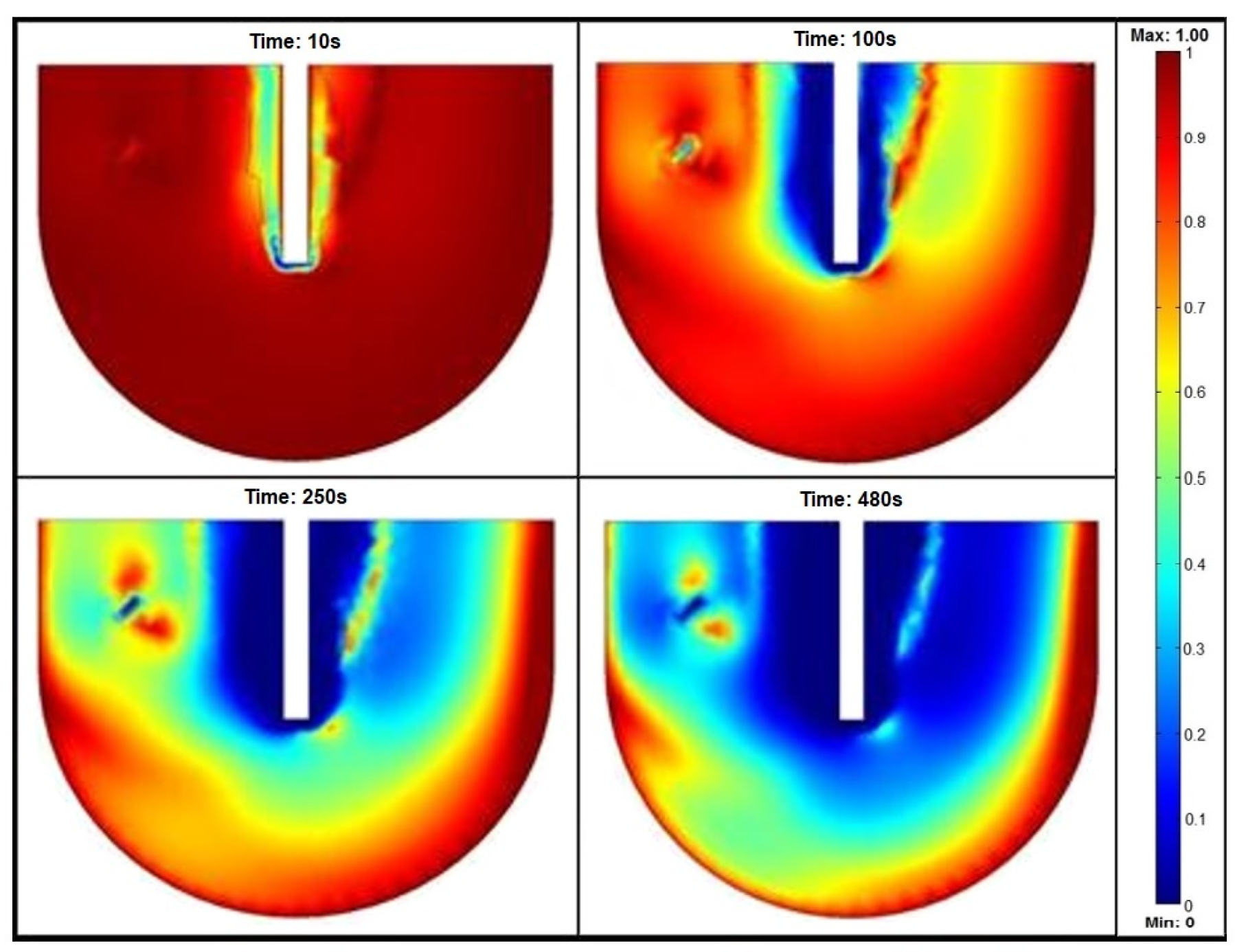

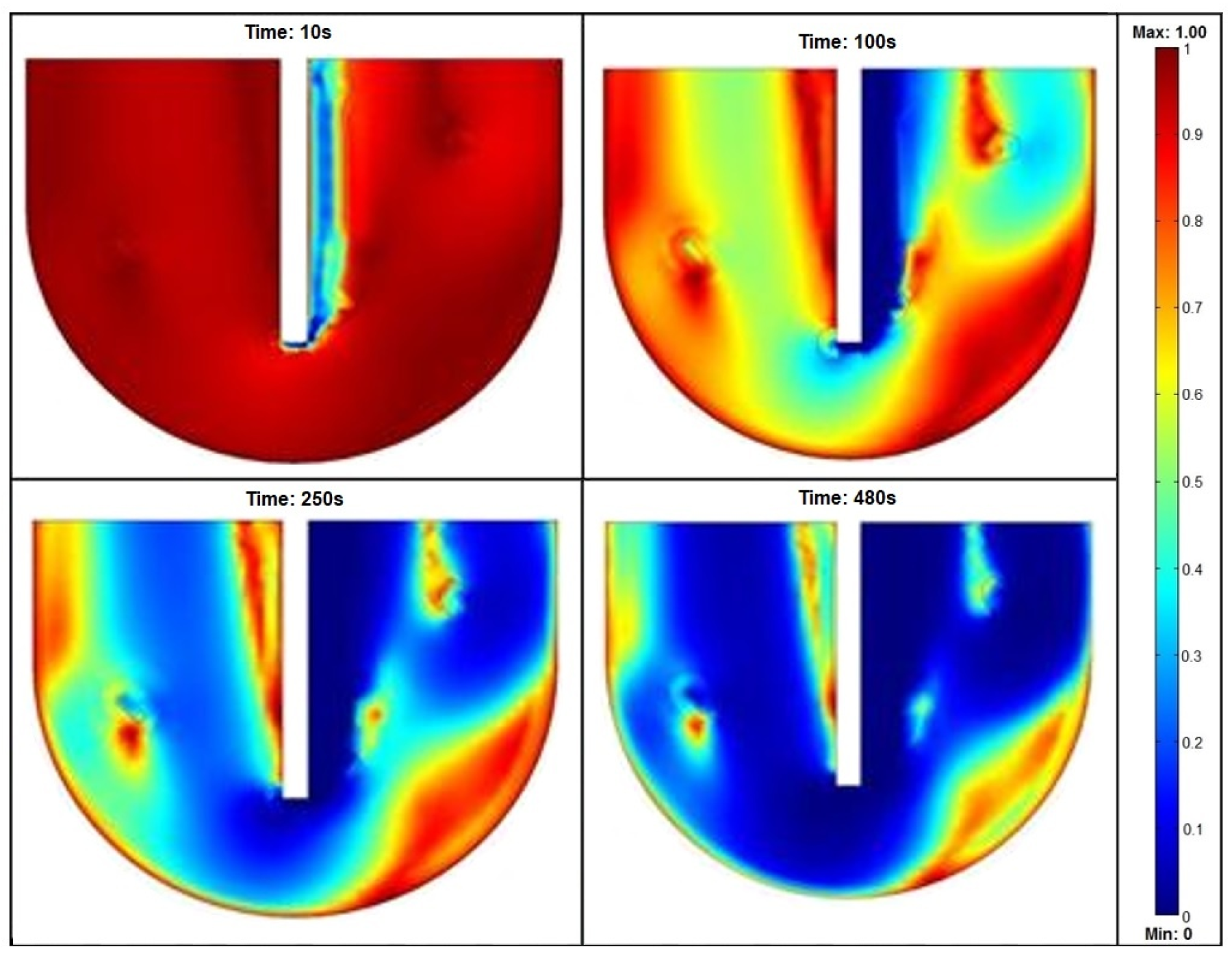

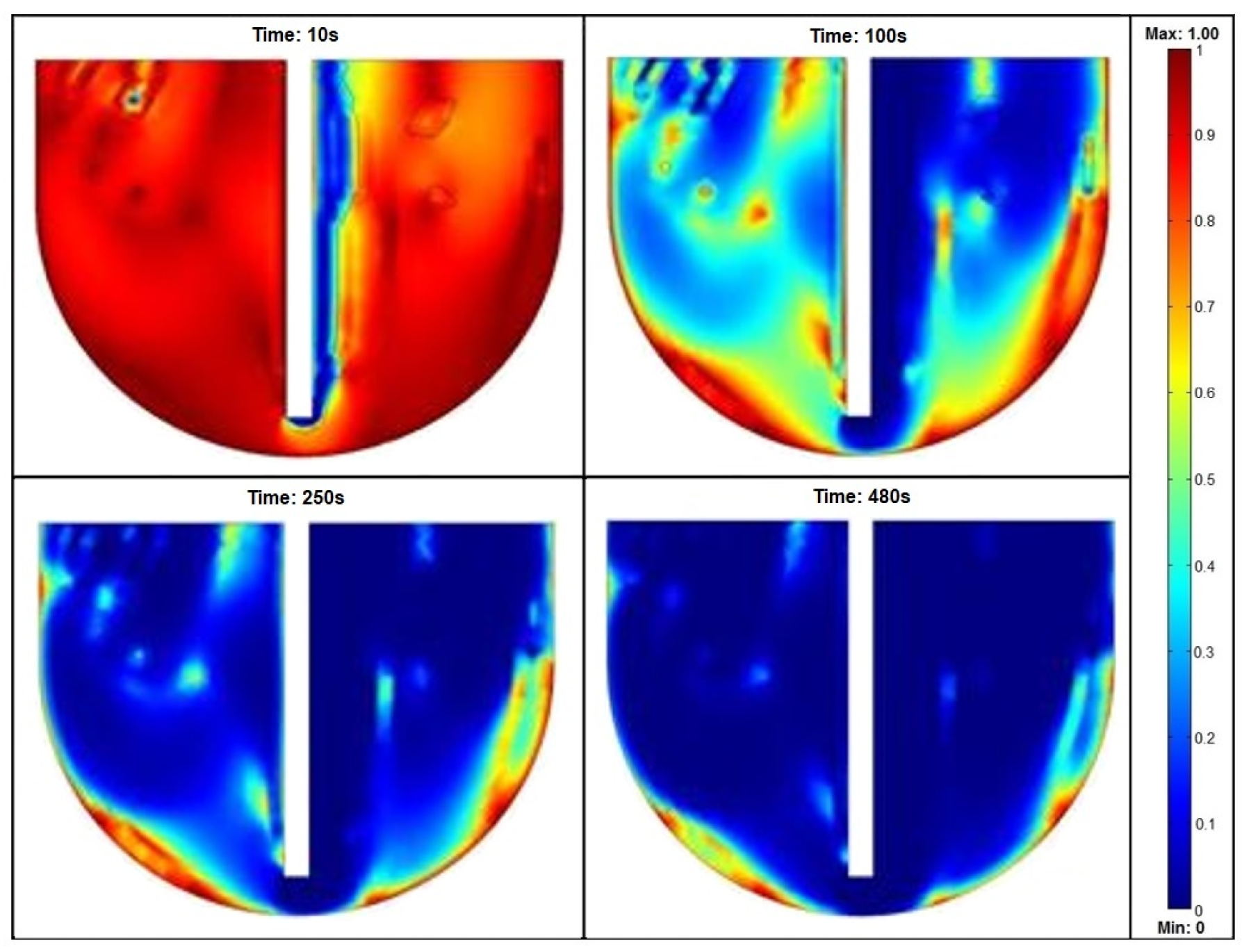

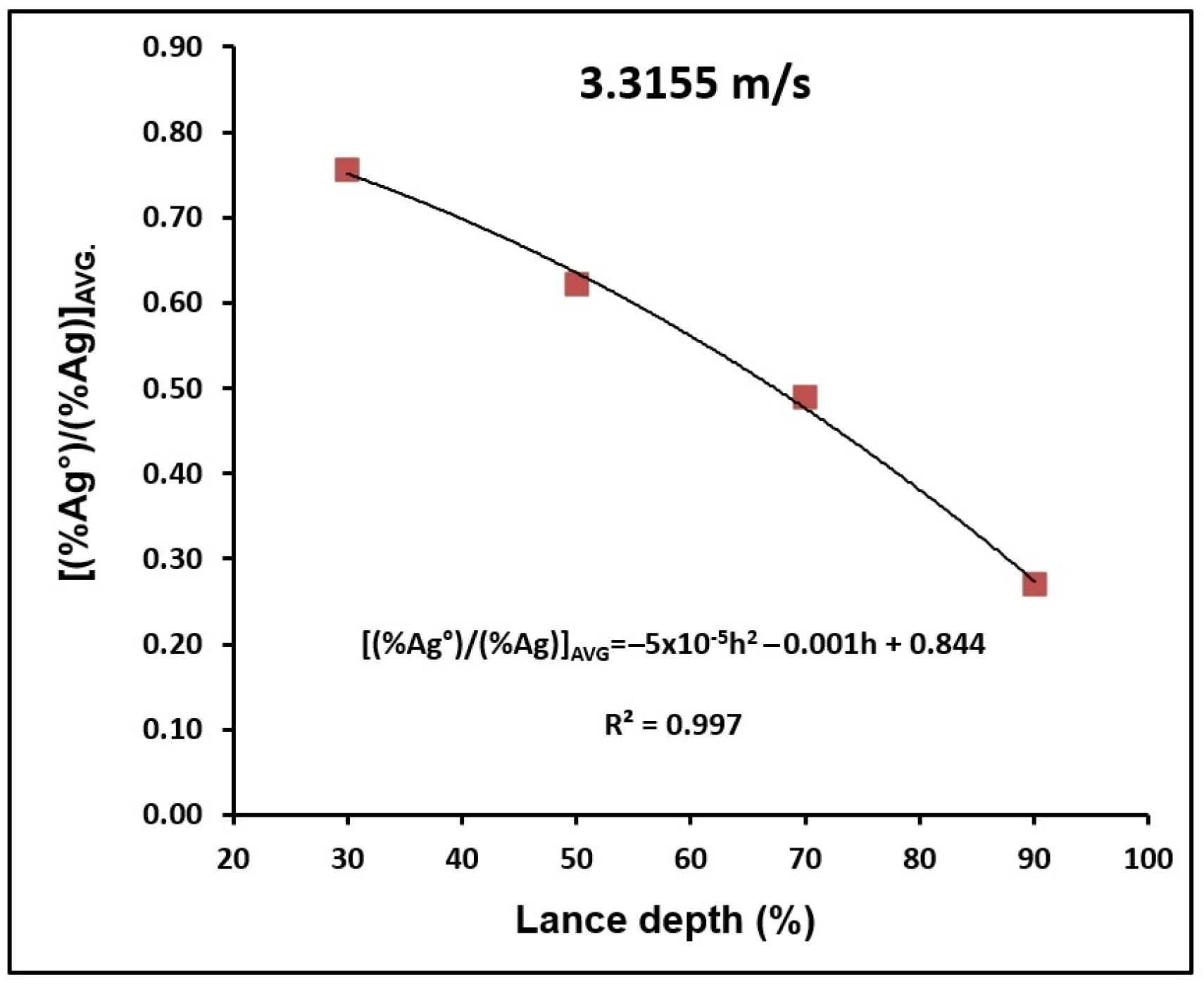

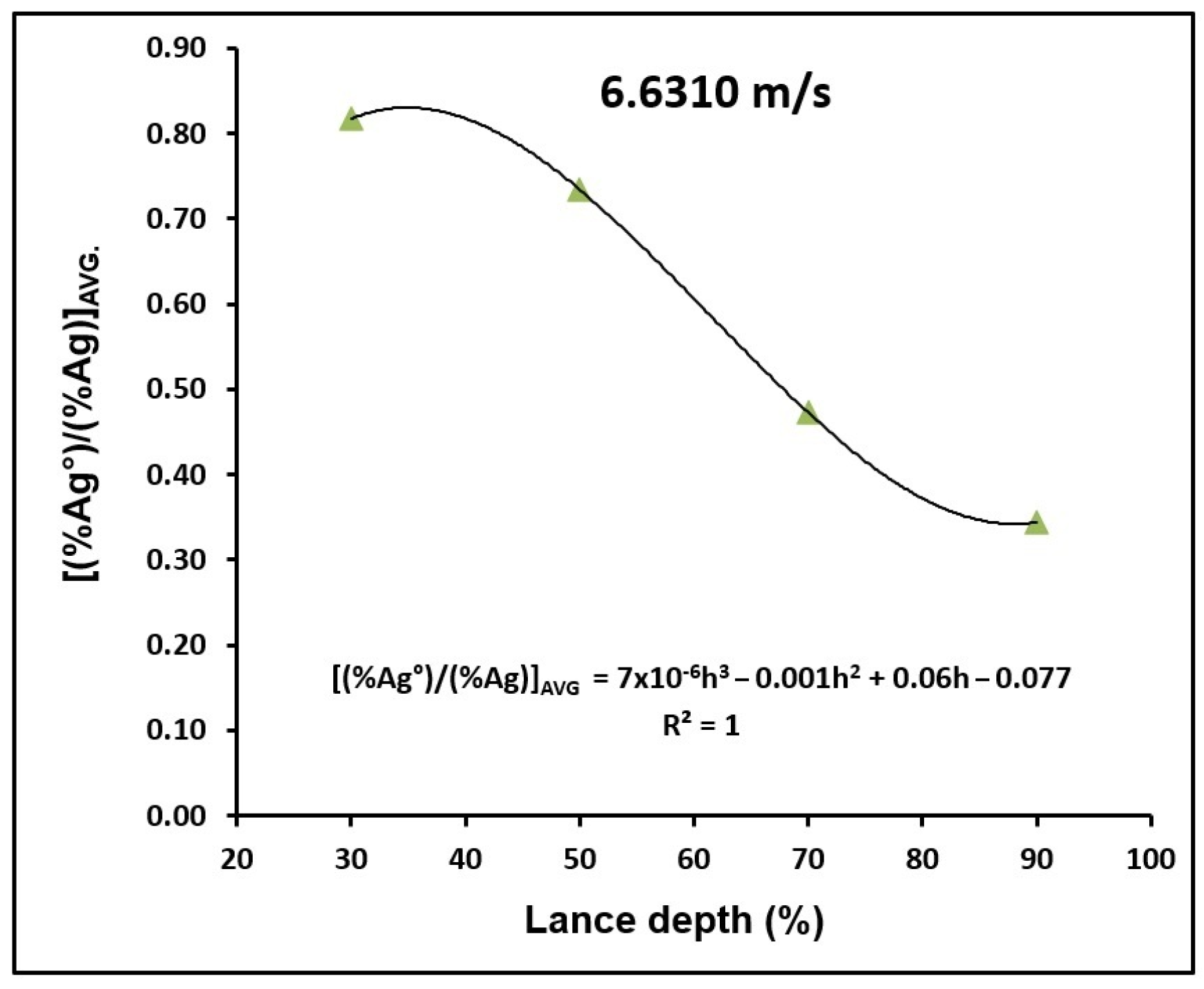

3.1. Depth of Lance

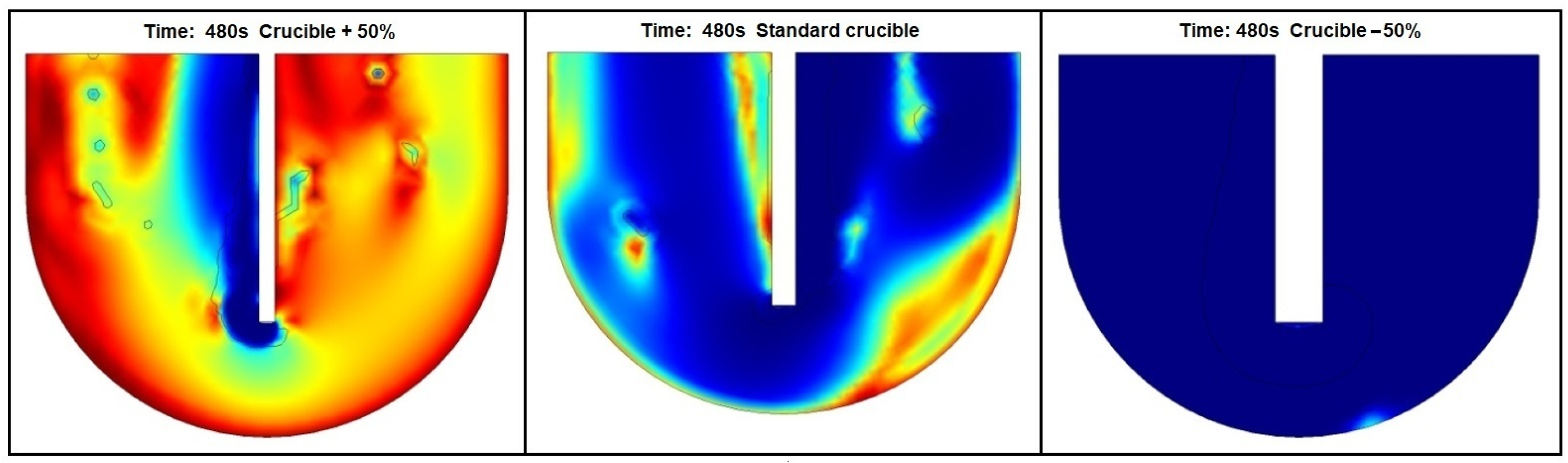

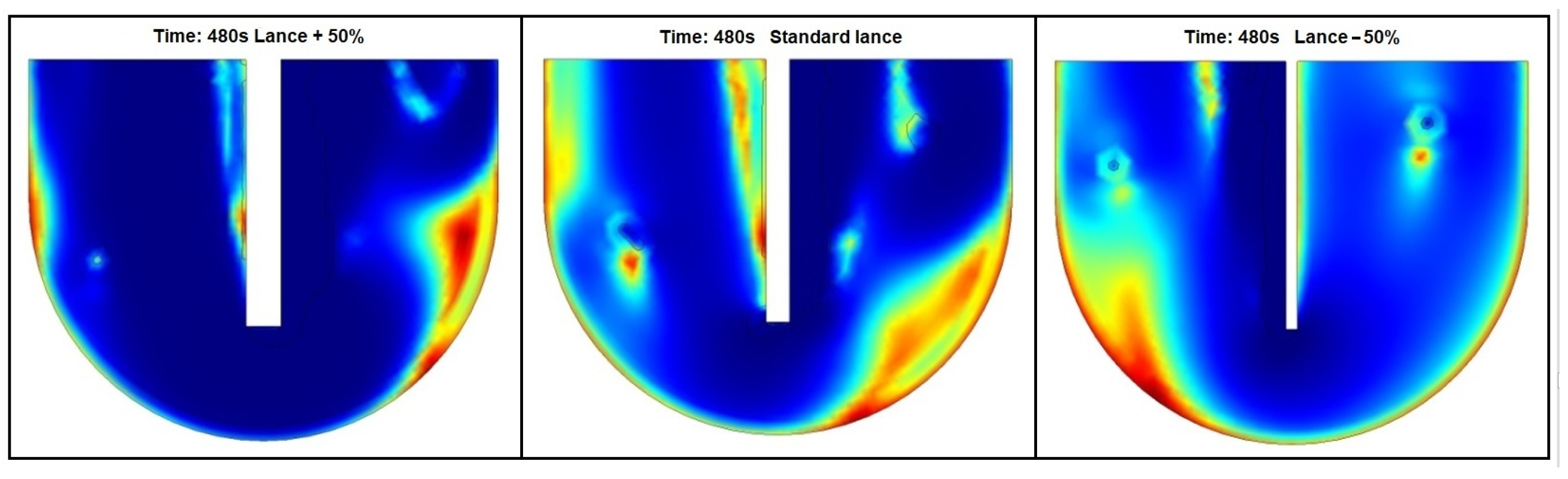

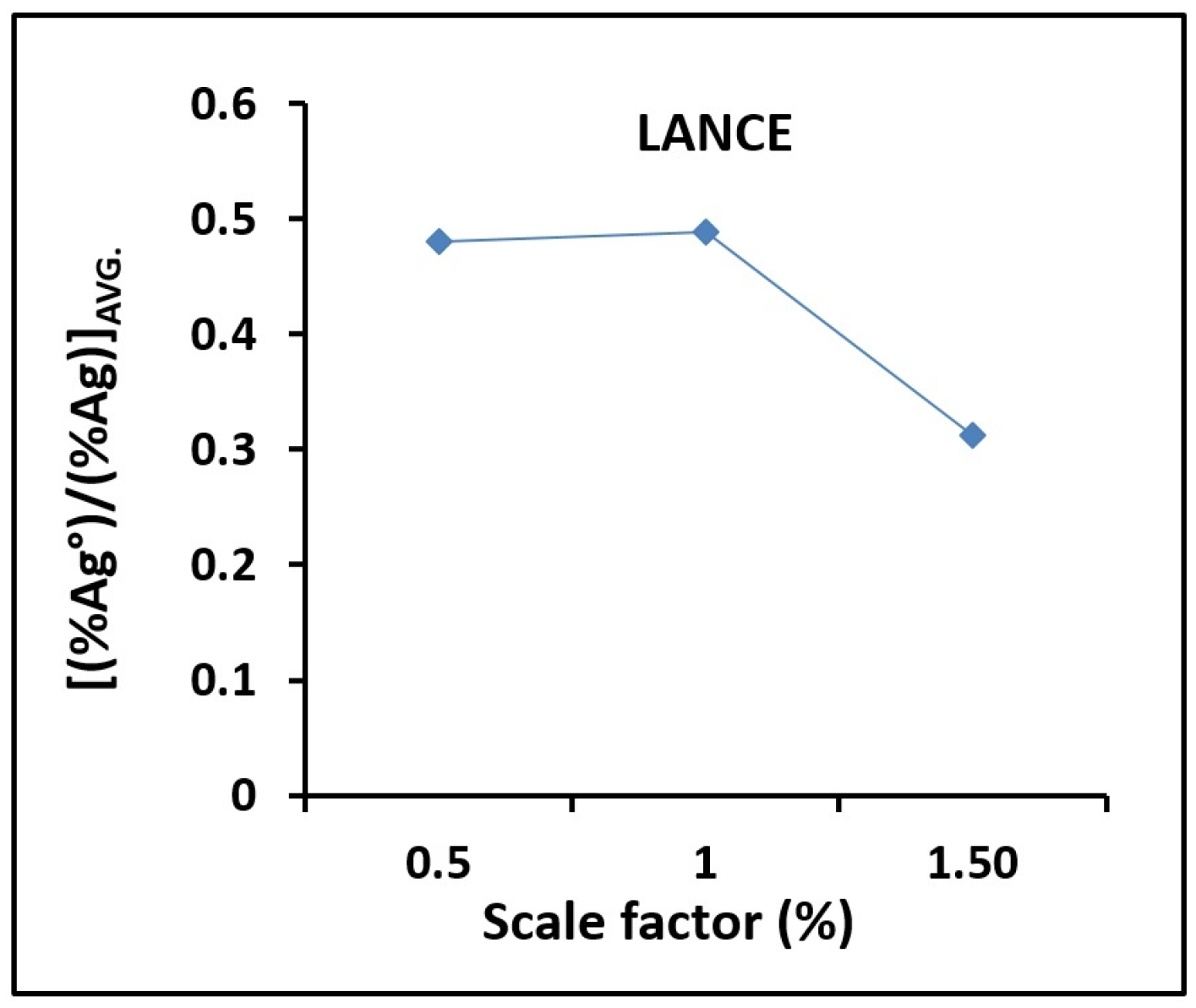

3.2. Lance and Crucible Dimensions

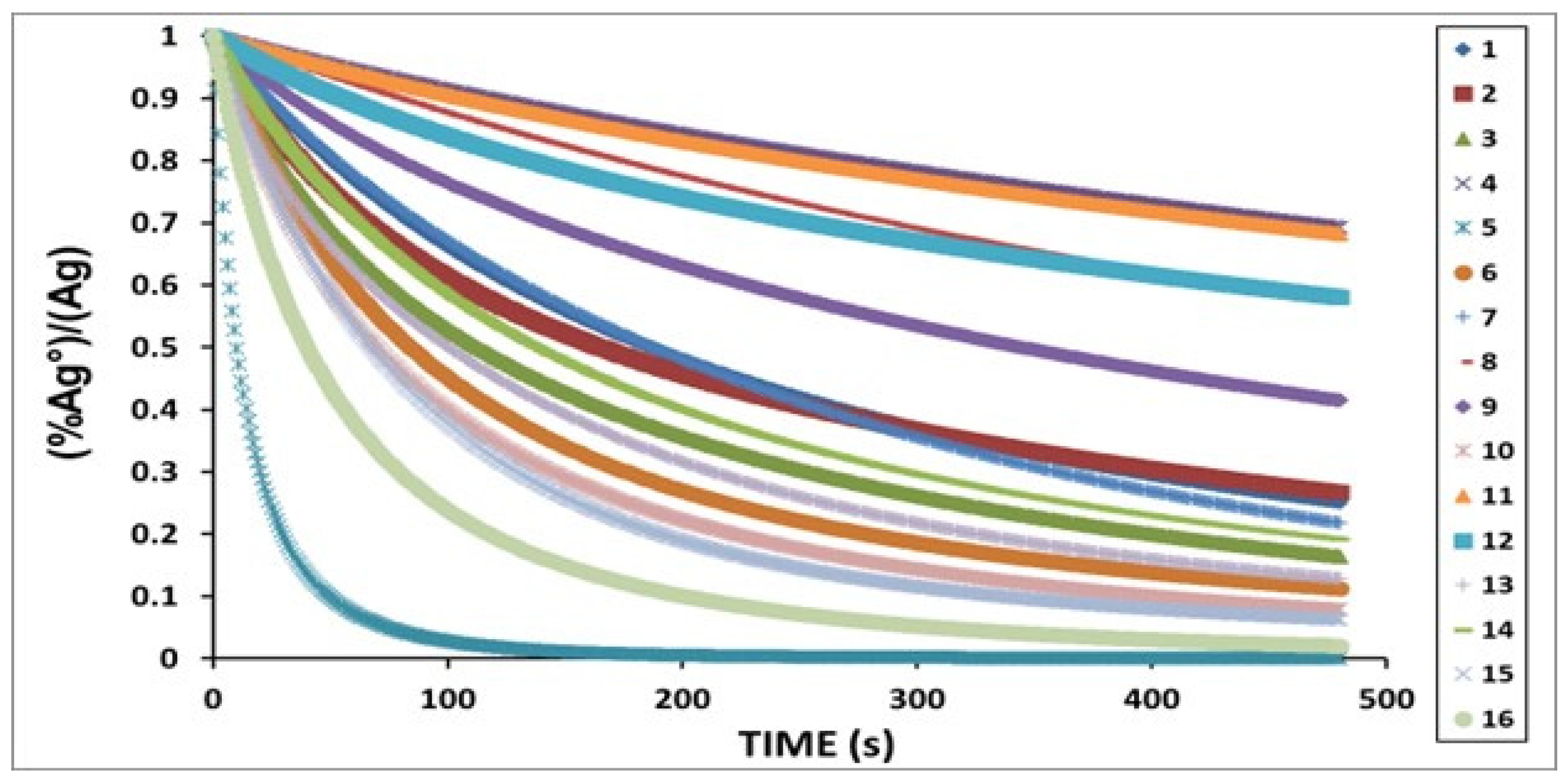

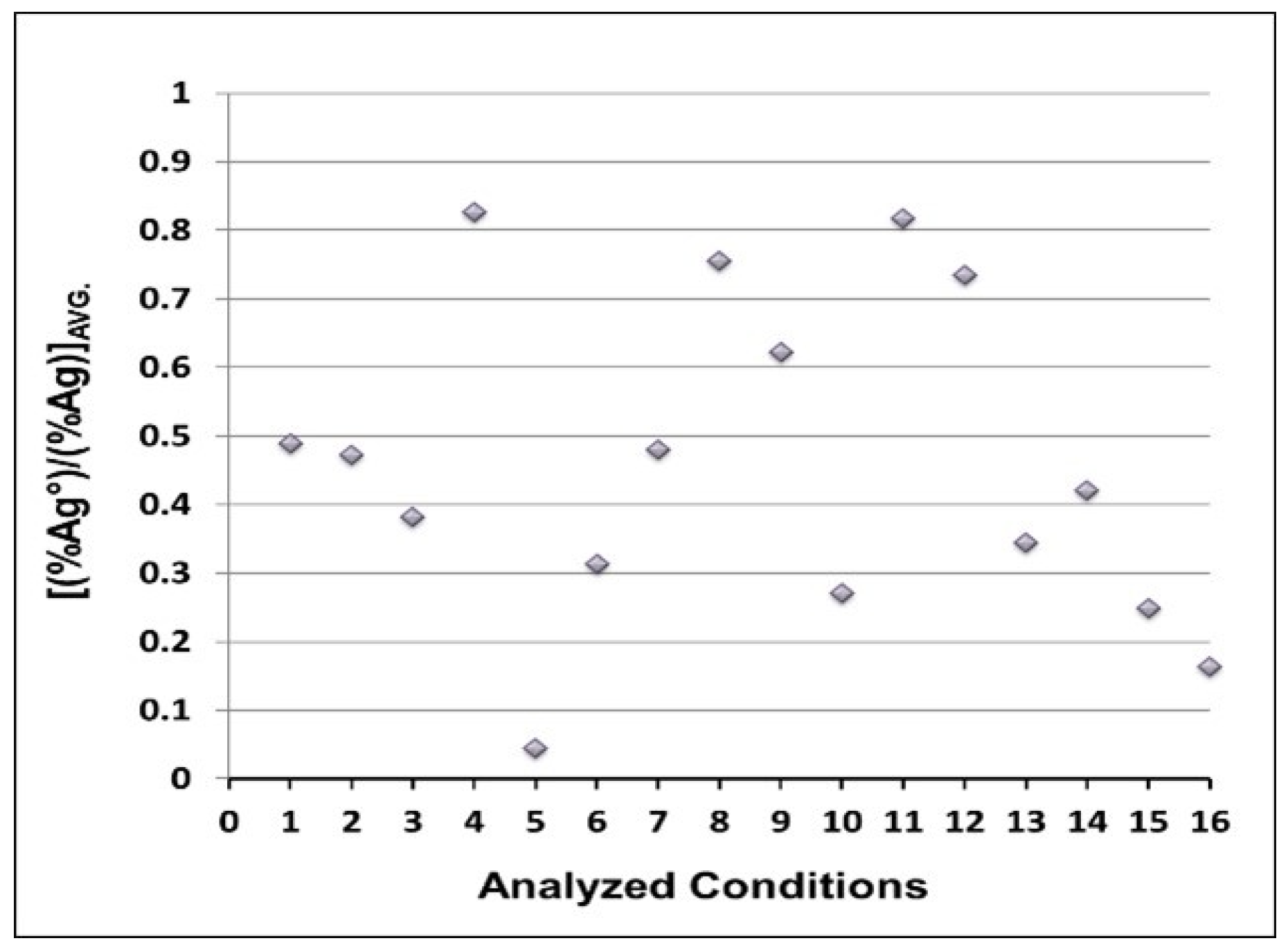

3.3. Kinetic Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plascencia, G.; Romero, A.; Morales, R.; Hallen, M.; Chávez, F. Sulfur Injection to Remove Copper from Recycled Lead. Can. Metall. Q. 2001, 40, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, T.R.A. Desilverizing of Lead Bullion. JOM 1954, 6, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalam, A.; Reuter, M.A.; Stelter, M.; Reinmöller, M.; Gräbner, M.; Richter, A.; Charitos, A. A Review of Top-Submerged Lance (TSL) Processing—Part I: Plant and Reactor Engineering. Metals 2023, 13, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalam, A.; Reuter, M.A.; Stelter, M.; Reinmöller, M.; Gräbner, M.; Richter, A.; Charitos, A. A Review of Top-Submerged Lance (TSL) Processing—Part II: Thermodynamics, Slag Chemistry and Plant Flowsheets. Metals 2023, 13, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emi, T.; Yin, H. The Howard Worner International Symposium on Injection in Pyrometallurgy; TMS, Pennsylvania State University: University Park, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, M.; Romero, A.; Morales, R.; Hernandez, M.; Chavez, F.; Castro, J. Hot metal pretreatment by powder injection of lime-based reagents. Steel Res. 2001, 72, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiso, D.; Schwitalla, D.H.; Korobeinikov, I.; Meyer, B.; Reuter, M.A.; Richter, A. Dynamics of Rising Bubbles in a Quiescent Slag Bath with Varying Thermo-Physical Properties. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2020, 51, 2843–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, T.; Schubert, C.; Eickhoff, M.; Pfeifer, H. A Review of Bubble Dynamics in Liquid Metals. Metals 2021, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Blanpain, B.; Reuter, M.; Guo, M. The State-of-the-Art in the Top Submerged Lance Gas Injection Technology: A Review. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2022, 53, 3345–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. Cfd–Pbm Simulation on Bubble Size Distribution in a Gas–Liquid–Solid Three-Phase Stirred Tank. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 1934–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F. Two-Way PBM–Euler Model for Gas and Liquid Flow in the Ladle: Influence of Ladle Geometry on Bubble-Size Distribution. Materials 2023, 16, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, V.H.; Vargas, M.; Cruz, A.; Romero, A.; Rivera, J.E. Hydrodynamic simulation of gas-particle injection into molten lead. Mater. Res.-Ibero-Am. J. Mater. 2014, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.E.; Gutiérrez, V.H.; Vargas, M.; Gregorio, K.M.; Cruz, A.; Avalos, F.; Ortíz, J.C.; Escobedo, J.C. Application of Computational fluid dynamic in aluminum refining through pneumatic injection of powders. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 1550–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, D.; Živković, Ž.; Liu, Y.-H. Comparative study of thermodynamic predicting methods applied to the Pb–Zn–Ag system. J. Alloys Compd. 1998, 265, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohguchi, S.; Robertson, D. Kinetic model for refining by submerged powder injection: Part 1 Transitory and permanent-contact reaction. Ironmak. Steelmak. 1984, 11, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell, D. An Introduction to Transport Phenomena in Materials Engineering, Editorial; Macmillan Publishing Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, V.H.; Vargas, M.; Cruz, A.; Sanchez, R.G. Silver removal from molten lead through zinc powder injection. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, V.H.; Cruz, A.; Romero, A.; Rivera, J.E. Analysis of the sulfur decoppering from molten lead by powder injection. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2015, 56, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langberg, D.E.; Nilmani, M. The production of nickel-zinc alloys by powder injection. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1996, 27, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.G.C.; Deo, B.; Ohguchi, S. Multicomponent mixed-transport-control theory for kinetics of coupled slag/metal and slag/metal/gas reactions: Application to desulphurization of molten iron. Ironmak. Steelmak. 1984, 11, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Visuri, V.V.; Vuolio, T.; Haas, T.; Fabritius, T. A Review of Modeling Hot Metal Desulfurization. Steel Res. Int. 2020, 91, 1900454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User’s Guide CFD Module; COMSOL Multiphysics 4.1; COMSOL: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010.

- Scheepers, E.; Eksteen, J.J.; Aldrich, C. Optimization of The Lance Injection Desulphurization of Molten Iron using Dynamic Modeling. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter [12,13,14,15,16,17] | Symbol | Value | Unit | Material/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic length | Lc | 5.061 × 10−3 | m | Used in Equations (10)–(12) |

| Injected volume | Vinj | 1.466 × 10−5 | m3 | From Zn mass and true density |

| Solid initial temperature | T0 | 25 | °C | Zinc |

| Solid melting temperature | Tf | 420 | °C | Zinc |

| Solid density | ρs | 7140 | kg m−3 | Zinc (true density) |

| Latent heat of fusion | ΔHfs | 1.12 × 105 | J kg−1 | Zinc |

| Temperature (bath) | Tm | 480 | °C | Molten lead |

| Specific heat (bath) | Cpm | 153 | J·kg−1 K−1 | Molten lead |

| Density (bath) | ρm | 10,359 | kg m−3 | Molten lead (≈480 °C) |

| Thermal conductivity (bath) | km | 19 | W m−1 K−1 | Molten lead |

| Base Crucible Geometry | ||||

| Crucible diameter (base) | Dc | 0.127 | m | — |

| Bath depth (base) | (H) | 0.100 | m | — |

| Base Lance Geometry | ||||

| Lance outer diameter (base) | DL | 0.00635 | m | — |

| Lance length (base) | LL | 0.070 | m | — |

| Reference Injection Velocities | 3.32; 6.63; 9.79 | m·s−1 | Used in condition matrix |

| Velocity (m/s) | Lance Height (70%) | Crucible Size (+50%) | Crucible Size (50%) | Lance Size (+50%) | Lance Size (50%) | Lance Height (30%) | Lance Height (50%) | Lance Height (90%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.32 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 6.63 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||

| 9.79 | 3 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Velocity (m/s) | Lance Height (70%) | Crucible Size (+50%) | Crucible Size (50%) | Lance Size (+50%) | Lance Size (50%) | Lance Height (30%) | Lance Height (50%) | Lance Height (90%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.32 | 1.0 s | 2.0 s | 2.0 s | 0.8 s | 0.9 s | 2.0 s | 1.5 s | 1.0 s |

| 6.63 | 1.2 s | 1.2 s | 1.4 s | 1.6 s | ||||

| 9.79 | 1.5 s | 1.5 s | 2.0 s | 2.6 s |

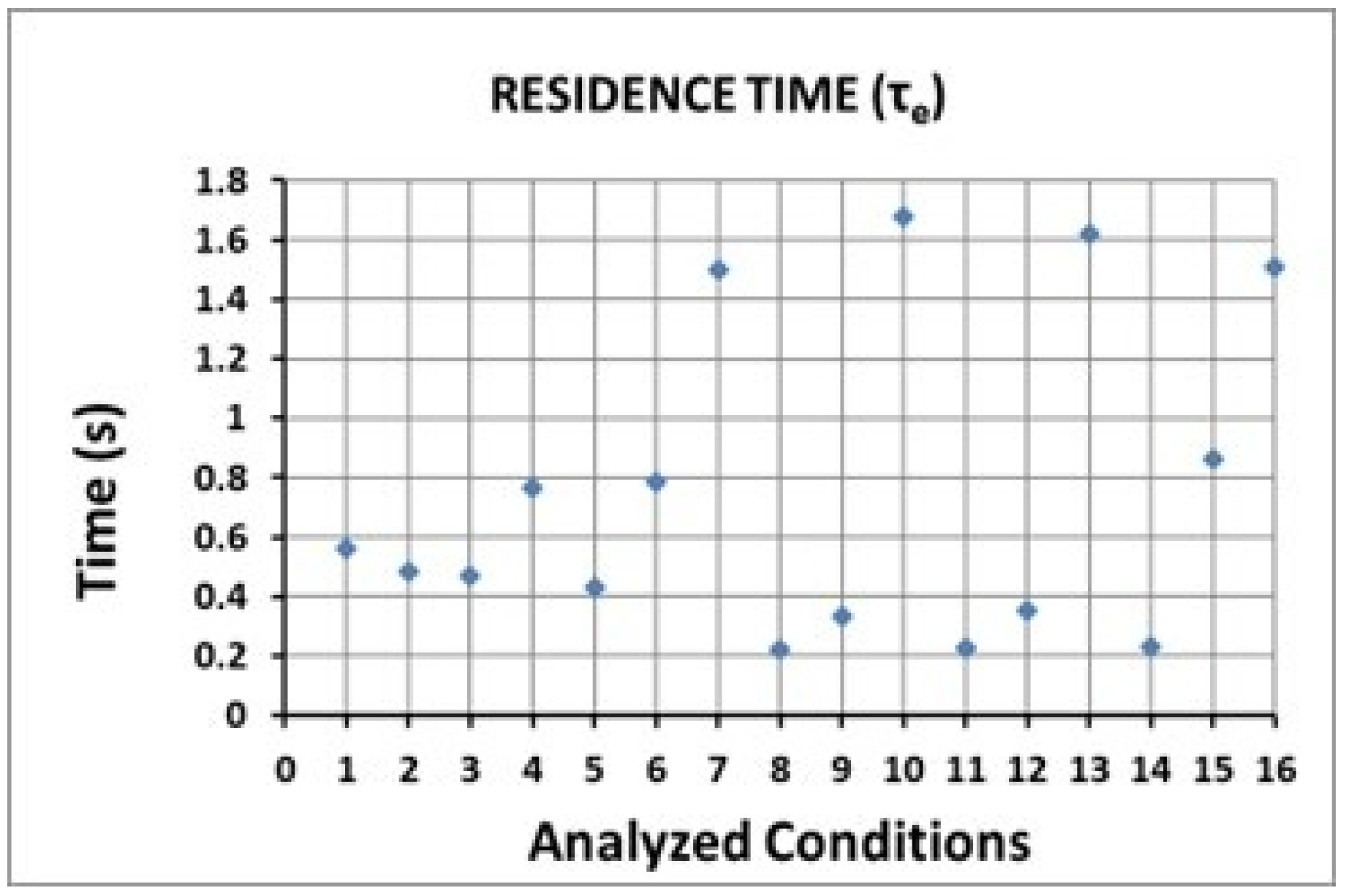

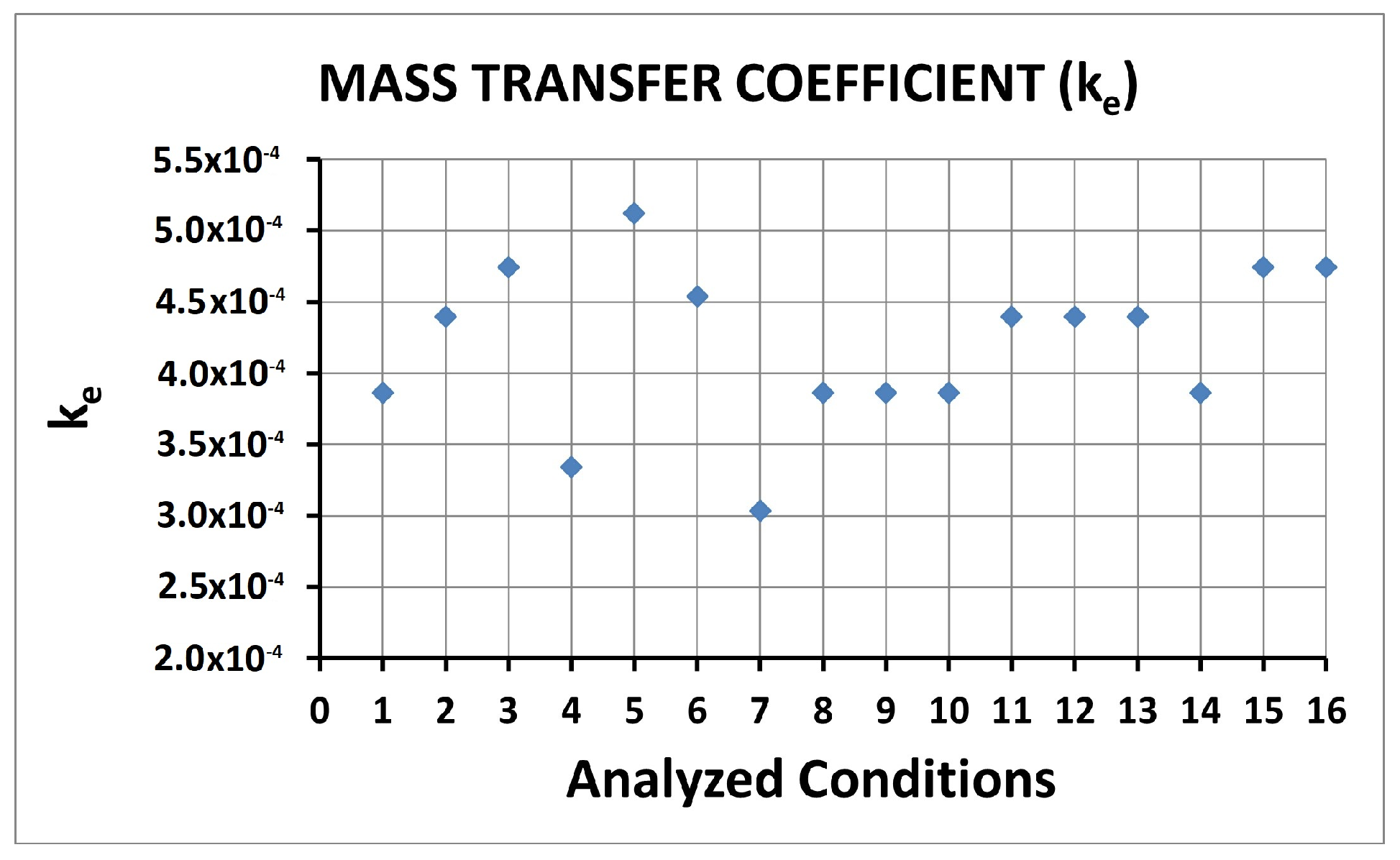

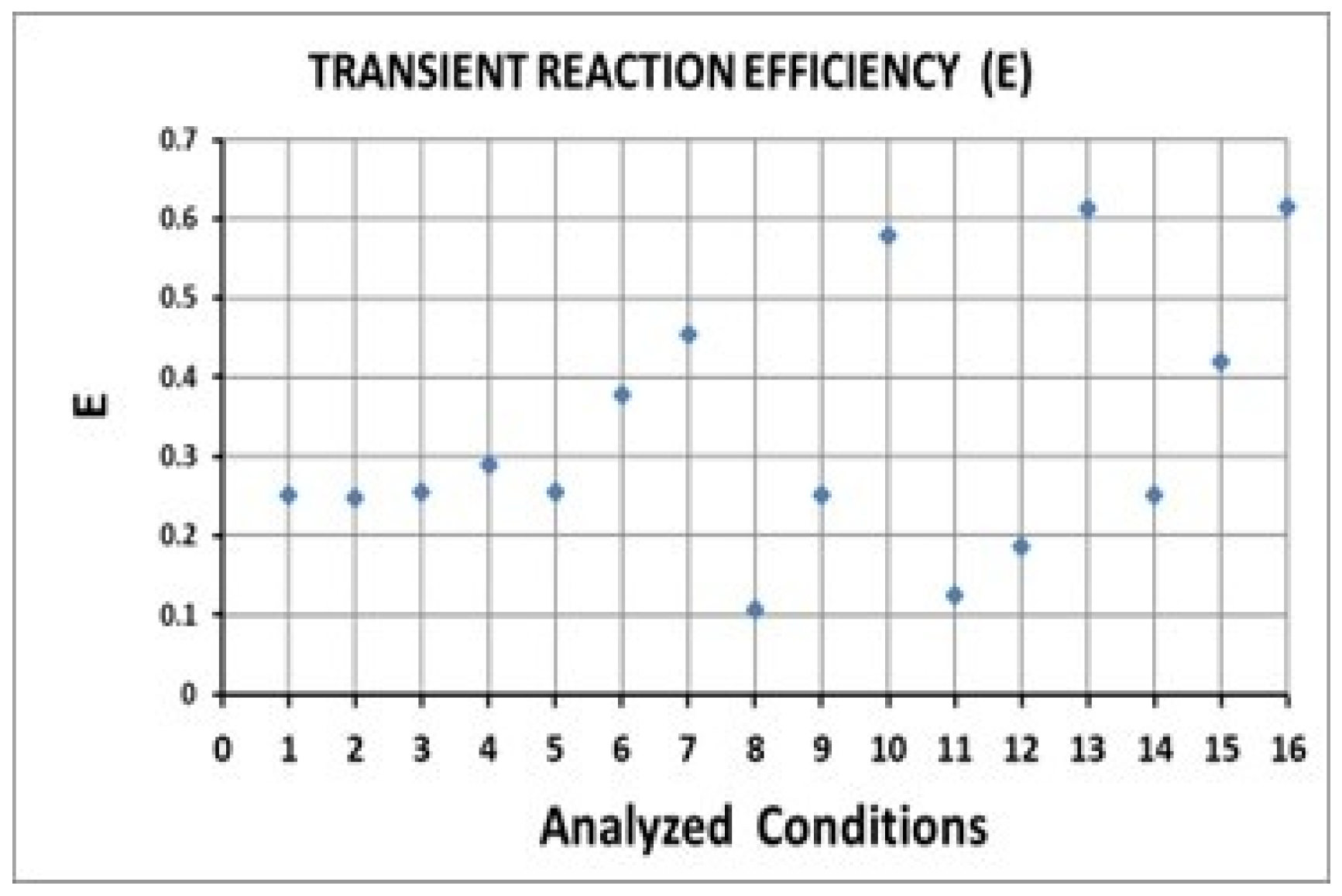

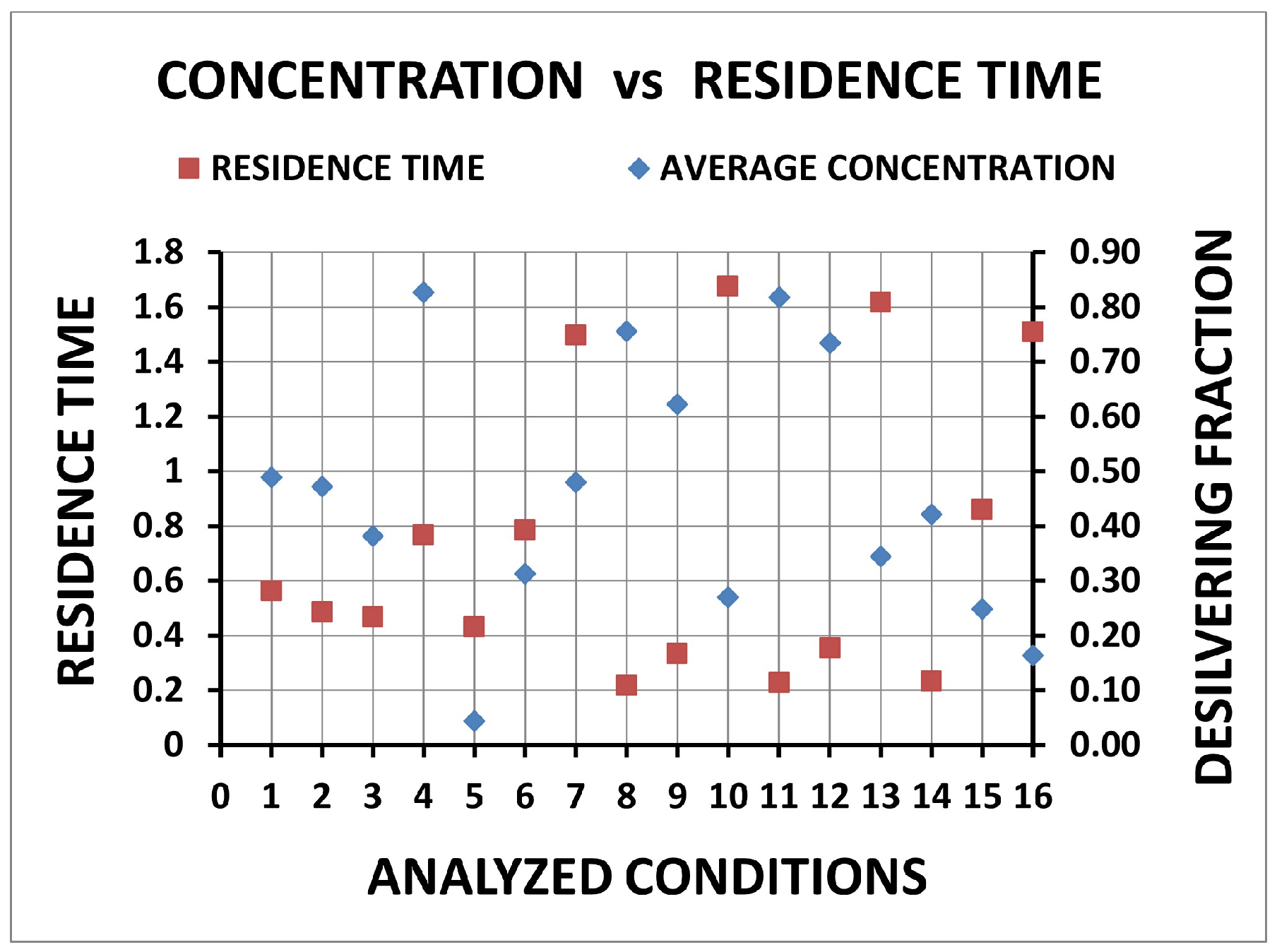

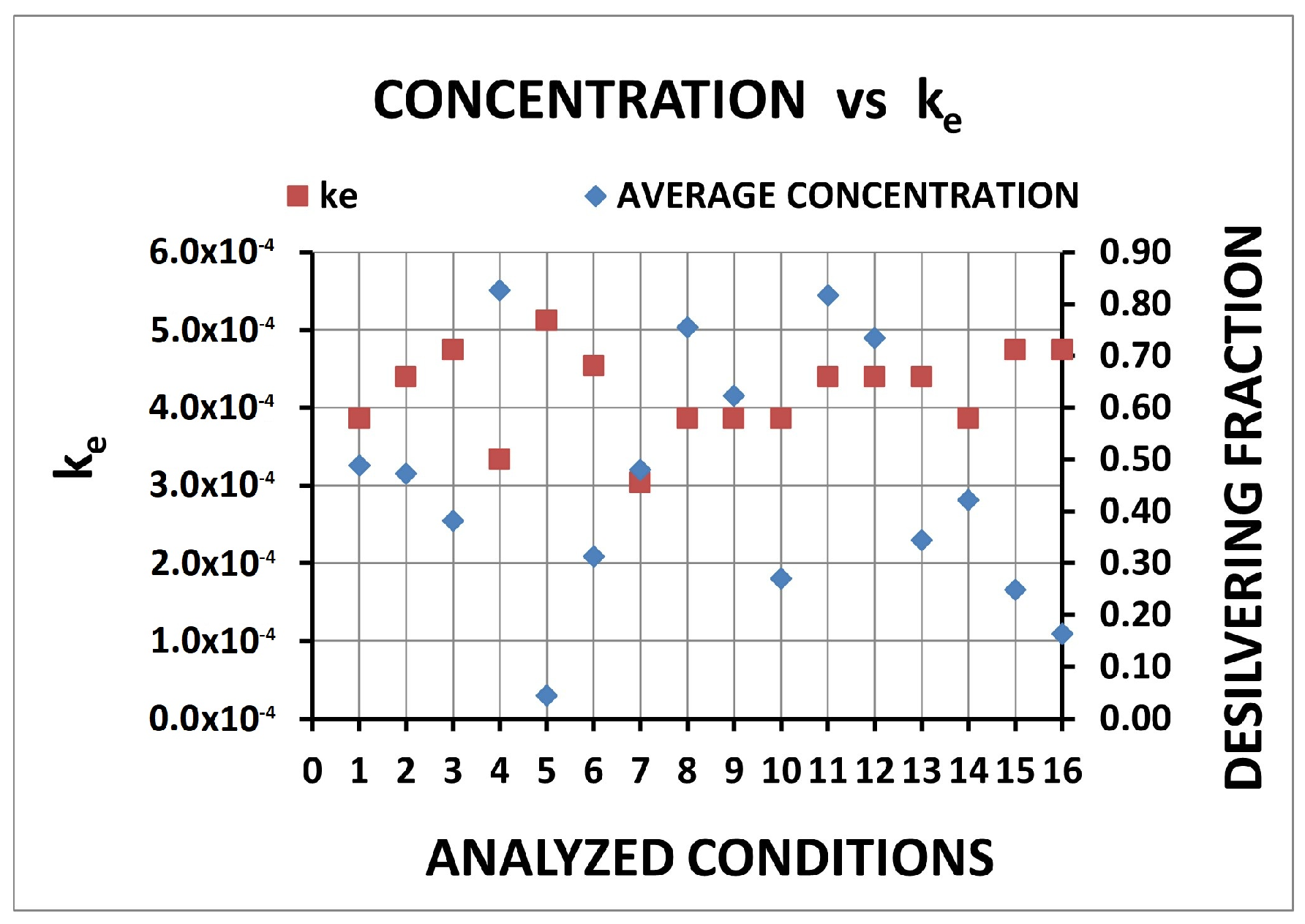

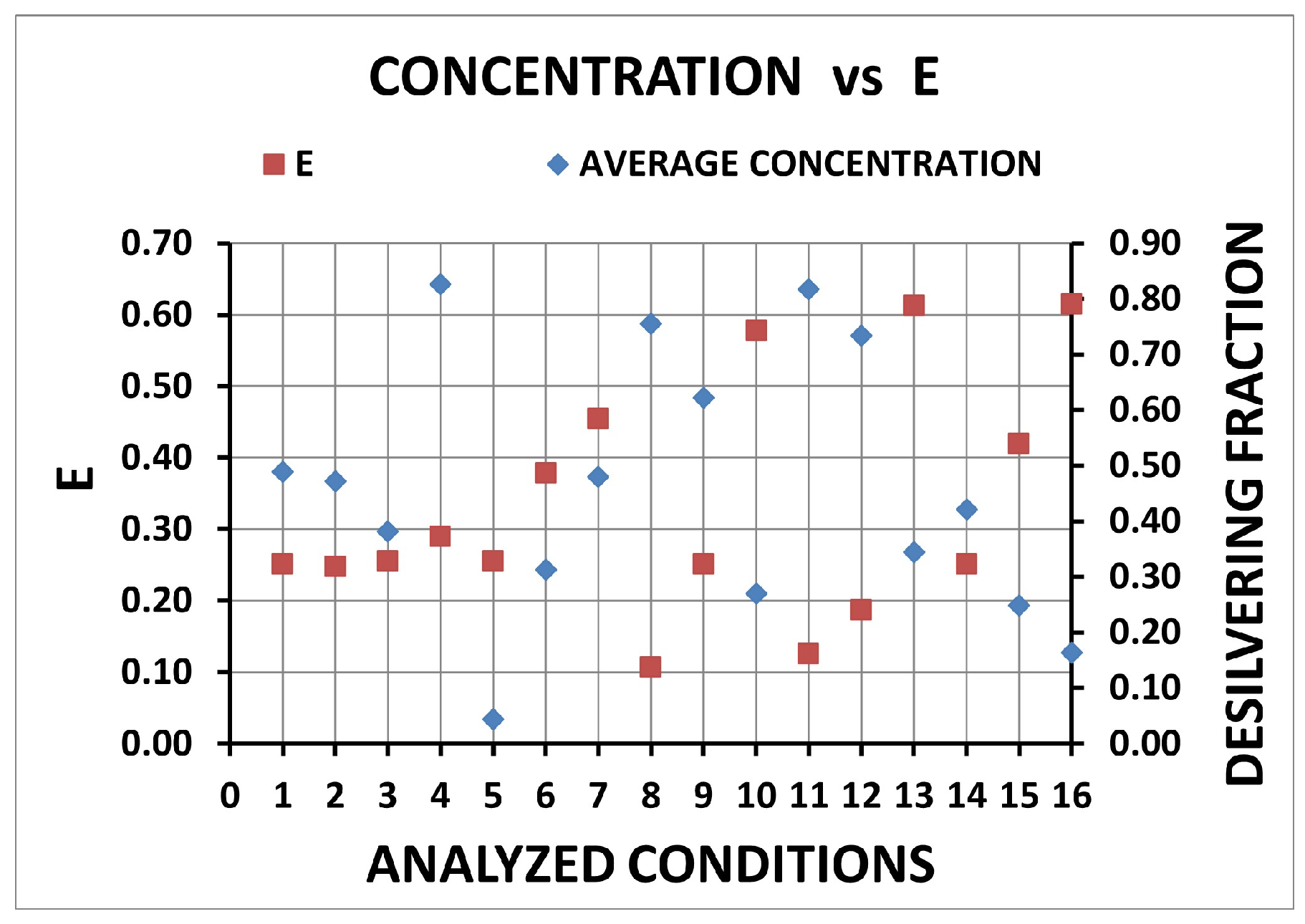

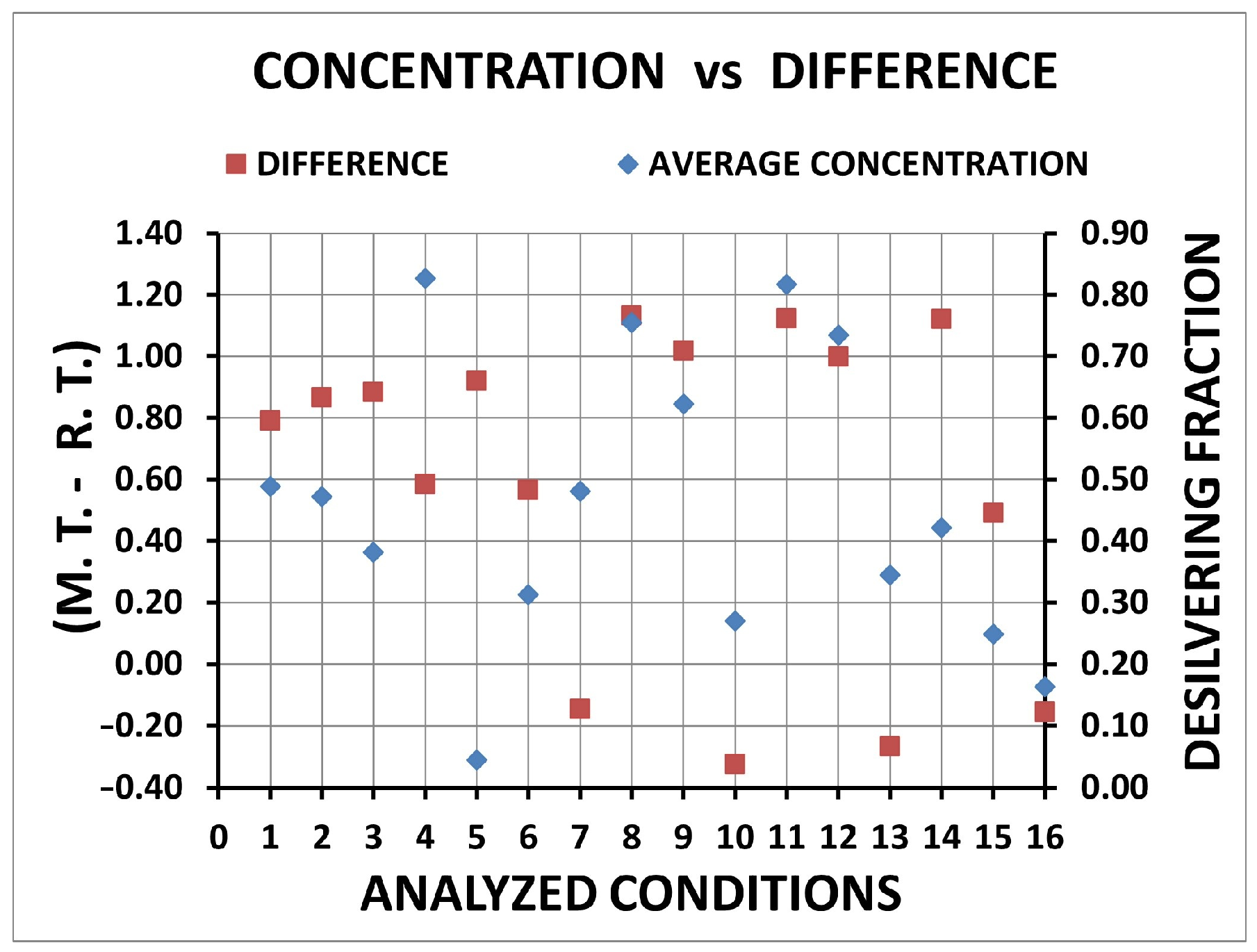

| Condition | Desilvering Fraction | Residence Time (s) | Mixing Time (s) | ke | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.49 | 0.562 | 0.062 | 3.86 × 10−4 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 0.47 | 0.485 | 0.064 | 4.40 × 10−4 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 0.38 | 0.468 | 0.066 | 4.74 × 10−4 | 0.26 |

| 4 | 0.83 | 0.768 | 0.125 | 3.34 × 10−4 | 0.29 |

| 5 | 0.04 | 0.432 | 0.014 | 5.12 × 10−4 | 0.26 |

| 6 | 0.31 | 0.787 | 0.052 | 4.54 × 10−4 | 0.38 |

| 7 | 0.48 | 1.498 | 0.070 | 3.04 × 10−4 | 0.45 |

| 8 | 0.76 | 0.220 | 0.074 | 3.86 × 10−4 | 0.11 |

| 9 | 0.62 | 0.334 | 0.051 | 3.86 × 10−4 | 0.25 |

| 10 | 0.27 | 1.677 | 0.070 | 3.86 × 10−4 | 0.58 |

| 11 | 0.82 | 0.229 | 0.055 | 4.40 × 10−4 | 0.13 |

| 12 | 0.73 | 0.354 | 0.052 | 4.40 × 10−4 | 0.19 |

| 13 | 0.34 | 1.618 | 0.090 | 4.40 × 10−4 | 0.61 |

| 14 | 0.42 | 0.232 | 0.045 | 3.86 × 10−4 | 0.25 |

| 15 | 0.25 | 0.861 | 0.051 | 4.74 × 10−4 | 0.42 |

| 16 | 0.16 | 1.508 | 0.096 | 4.74 × 10−4 | 0.61 |

| Better Conditions Rank | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figures | ||||||

| Desilvering fraction | 5 | 16 | 15 | 10 | 6 | |

| Residence time | 10 | 13 | 16 | 7 | 15 | |

| Mixing time | 5 | 14 | 9 | 15 | 12 | |

| E | 16 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 15 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez, V.H.G.; Vázquez, S.L.O.; Ramírez, A.C.; Alvarado, R.G.S.; Salinas, J.E.R.; Gutiérrez, M.C.O.; Diaz, M.P.C. Kinetic Simulation of Gas-Particle Injection into the Molten Lead. Metals 2025, 15, 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121334

Pérez VHG, Vázquez SLO, Ramírez AC, Alvarado RGS, Salinas JER, Gutiérrez MCO, Diaz MPC. Kinetic Simulation of Gas-Particle Injection into the Molten Lead. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121334

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez, Victor Hugo Gutiérrez, Seydy Lizbeth Olvera Vázquez, Alejandro Cruz Ramírez, Ricardo Gerardo Sánchez Alvarado, Jorge Enrique Rivera Salinas, Mario Cesar Ordoñez Gutiérrez, and Mercedes Paulina Chávez Diaz. 2025. "Kinetic Simulation of Gas-Particle Injection into the Molten Lead" Metals 15, no. 12: 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121334

APA StylePérez, V. H. G., Vázquez, S. L. O., Ramírez, A. C., Alvarado, R. G. S., Salinas, J. E. R., Gutiérrez, M. C. O., & Diaz, M. P. C. (2025). Kinetic Simulation of Gas-Particle Injection into the Molten Lead. Metals, 15(12), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121334