Abstract

Zirconium belongs to the group of critical rare metals and is primarily used in industry. Its most important application, as the basis for specialized alloys, is in nuclear reactors, owing to its exceptionally very low thermal neutron absorption cross-section. Based on theoretical and experimental investigation, the potential for removing metallic (Al, Ti, Hf, V, Fe, Cr, Cu, Ni) and non-metallic (O, C) impurities from technogenic zirconium during electron beam melting (EBM) was assessed. The influence of temperature (ranging from 2350 K to 2750 K) and refining duration (10, 15, and 20 min) under vacuum conditions (1 × 10−3 Pa) was investigated concerning the degree of impurity removal, the microstructure, and the micro-hardness of the resulting ingots. It was established that under optimal EBM conditions for technogenic zirconium (T = 2750 K, τ = 20 min), the total refining efficiency reached approximately 87%, and the achieved Zr purity was 99.756%. Among the impurities present in the technogenic zirconium, the lowest removal efficiencies were recorded for Al (54.90%) and Cr (88.89%), with the lower refining efficiency for Al influencing the microstructure and micro-hardness of the ingots produced after EBM.

1. Introduction

Zirconium (Zr) is a metal from the group of rare elements (Nb, Ta, and Hf) and is known for its special properties [1]. These include high resistance to corrosion, good mechanical strength, and unique nuclear characteristics, which make it essential for several important industries, including nuclear power, microelectronics, medicine, etc. [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Its most significant use is in the nuclear power industry. The most important property for nuclear reactors is a very low thermal neutron absorption cross-section of zirconium (0.18 barns). This makes its alloys the best material for making the cladding that covers nuclear fuel and for other structural parts inside a reactor core operating at temperatures between 350 and 400 °C [9]. For a nuclear reactor to operate safely and efficiently, the base zirconium metal used for alloying must be very pure. It is critical to remove hafnium (Hf), an element that is always found with zirconium in nature. Hafnium has a very high neutron absorption cross-section (113 barns) and is used for control rods, but it must be removed from zirconium to a level below 0.01 wt.% [9].

In addition to its nuclear uses, zirconium is also important in other fields. Because it is biocompatible and does not corrode, it is used successfully in the biomedical industry for dental and orthopedic implants [7]. The quality of these medical devices depends on the purity of the zirconium material used [5]. The requirements for all these applications are becoming more demanding, and there is a growing need for zirconium with very high purity and precise composition.

Recently, zirconium has also become a critical material for the new green energy economy, especially for hydrogen technologies [8]. Zirconia-based materials are being developed for high-performance diaphragms in Alkaline Electrolyzers (AEL). Also, yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) is the main material used for the electrolyte in Solid Oxide Electrolyzers (SOEL) and Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC) [8]. These new, high-technology uses show that a reliable supply of high-purity zirconium is more important than ever.

To use zirconium effectively in these advanced applications, it must be refined to a very high purity. Impurities can damage its performance. For example, interstitial impurities, such as oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon, as well as a range of metallic contaminants (e.g., Mg, Ni, Si), are known to negatively impact the mechanical and corrosion properties of zirconium alloys [9]. The importance of removing specific impurities is shown in an industrial example for the E110 alloy [10]. In this case, electron beam melting (EBM) was used to remove fluorine impurities to a level below 1 ppm. This step was critical to ensure the alloy’s safety and performance in high-temperature steam environments [10].

However, there are serious challenges in the global supply of zirconium. The traditional methods for producing zirconium, such as the Kroll process and solvent extraction, have major problems. They are expensive, not very efficient, use a lot of chemicals, and cause significant environmental pollution [11,12]. This creates a strong reason to find cleaner and more efficient purification technologies. This need for better technology is made more urgent by problems in the global supply chain. For example, China controls over 60% of the world’s zirconium oxide refining, which creates a supply risk [8]. Furthermore, studies project that by 2050, the demand for zirconium will be greater than the known reserves, creating a risk of resource depletion. The problem is made worse because there is almost no recycling; the current end-of-life recycling rate for zirconium is less than 1% [8]. In [13], a potential pathway for Zr purification from complex nuclear waste streams is presented by introducing a new class of ligands for the selective solvent extraction of Zr(IV) from simulated high-level liquid radioactive waste, exemplifying modern research efforts to improve chemical purification pathways that are fundamentally different from the physical approach offered by the EBM method. All these factors—the high cost and environmental problems of old methods, supply chain risks, the future lack of resources, and very low recycling rate—show an urgent need for effective advanced refining and recycling technologies.

Electron beam melting is an advanced high-vacuum technology that is very suitable for purifying refractory and chemically active metals, such as Ta, W, Mo, Ti, Hf, Zr, Nb, etc. [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In this process, a high-energy electron beam melts the material inside a high-vacuum chamber. This method has several key advantages for refining [14]. First, the high vacuum accelerates the refinement processes and prevents contamination from atmospheric gases. Another important advantage of the method is that the intense localized heating (high energy density of e-beam) allows impurities with a high vapor pressure to evaporate from the molten metal. The purified liquid metal is then cooled and solidified in a water-cooled copper crucible, which prevents recontamination. The final product is a metal with higher purity and improved properties [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

Recent research shows that EBM is a very relevant technology for producing high-value zirconium products. For example, EBM has been used successfully as the final refining step after zirconium was produced by aluminothermic reduction, where it effectively removed the leftover aluminum [24]. The effectiveness of EBM in refining a zirconium-containing alloy (niobium base metal) for a demanding nuclear application, highlighting the technology’s flexibility with reactive and refractory metals, is shown in [4]. It has also been used to produce specialized, high-purity alloys, such as a Zr-1%B alloy for nuclear applications [3]. In addition to refining, the technology can also be used for additive manufacturing to create finished parts, like biomedical Zr-2.5Nb alloy implants [6].

A review of the scientific literature reveals a specific opportunity for new research in this field. Although electron beam melting is an established innovative method for the purification of refractory metallic materials, systematic and detailed studies on EBM for the purification of zirconium materials, including zirconium waste, are limited. While pioneering foundational work exists, it provides a critical foundation upon which a modern, systematic approach can build. There is a clear opportunity to re-examine the fundamental relationships between EBM process parameters and the resulting material quality.

The goal of this study is to provide detailed research on the removal mechanisms of different impurities and analysis of the changes in chemical composition, microstructure, and micro-hardness of zirconium after refining technogenic zirconium by the EBM method and to investigate how key process parameters such as e-beam melting power (operating temperature), duration of purification time, and vacuum pressure affect the final quality of the metal. By using experimental and theoretical studies as well as precise characterization tools, this work aims to create a robust link between the EBM process conditions and the final quality of the zirconium after EBM refining of technogenic zirconium.

2. Material and Methods

The experiments on electron beam melting and refining (EBMR) of technogenic Zr were carried out in an ELIT-60 (Leybold GmbH, Cologne, Germany) laboratory furnace with a power of 60 kW at the Physical Problems of the E-Beam Technologies Laboratory of the Institute of Electronics, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. The furnace is equipped with a melting chamber with a volume of around a cubic meter and one electron gun with an accelerating voltage of 24 kV. The metal was irradiated and heated by an electron beam with a beam spot radius of 10 mm, and the beam current was in the range of 300 mA to 700 mA. The refined metal material solidifies in a water-cooled copper crucible (with a diameter of 60 mm) with a moving bottom, and the operation vacuum pressure is 1 × 10−3 Pa.

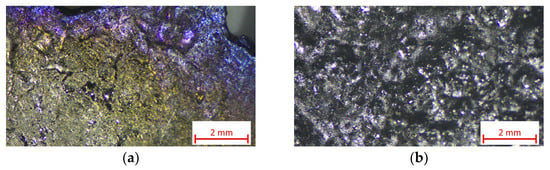

The appearance of two different sections of the technogenic Zr subjected to refining is shown in Figure 1. The samples were observed in reflected light with a Stemi 305 stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss IQS Deutschland GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an Axiocam 208 camera (Zeiss, Carl Zeiss IQS Deutschland GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany).

Figure 1.

Appearance of two different sections (a) and (b) of technogenic zirconium.

It can be observed that the used material is heterogeneous, and in some sections, it exhibits strong oxidation. The chemical analysis of the starting material and the ingots obtained after EBM was determined using ICP-OES (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), CS Analyzer (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) and ONH Analyzer (Leco, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The average elemental composition of the initial technogenic zirconium is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average chemical composition (mass %) of the technogenic zirconium prior to EBMR treatment.

The table shows that the impurity content in technogenic Zr is high. The content of titanium (1.2%) is the highest, followed by iron (0.56%), aluminum (0.51%), and vanadium (0.2%). The total content of impurities is 1.85%, including the content of oxygen (0.1%) and carbon (0.055%). The presence of oxygen and carbon in technogenic Zr indicates that the metallic impurities can also be present in the form of oxides and carbides.

EBMR of technogenic zirconium was carried out at electron beam powers corresponding to temperatures (T) of 2350 K, 2450 K, 2550 K, and 2750 K. The refining times (τ) at a given temperature were 10 min, 15 min, and 20 min. The temperature was determined by an optical pyrometer QP-31 using special correction filters.

To determine the microstructural features, microscopic observations were carried out in plane-polarized reflected light with an Axioscope 5 polarization microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) with an Axiocam 208 camera (Zeiss, Carl Zeiss IQS Deutschland GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany). ZENcore software v.2.3.69.1018 was used to process the microscopic images. The observations were carried out on polished samples processed according to the following procedure: a series of abrasive papers (120, 240, 400, and 800 grit) were used, and following this step, the samples were polished in three stages using diamond pastes on polishing cloths. The first polishing step used a 6 µm diamond paste (Akasel, Roskilde, Denmark) on a DURLAP silk cloth. The second step involved a 3 µm diamond paste (DP-Paste M, Struers, Ballerup, Denmark) on a MEDIOLAP cloth. The final polish used a 1 µm diamond paste (Akasel Stick Mono, Roskilde, Denmark) on a MICROLAP fine polishing cloth. To reveal the microstructure, the polished samples were etched for 5 s with a solution of 45 mL HNO3, 45 mL H2O, and 10 mL HF. The samples were immediately rinsed with running water and then dried before microscopic examination.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Zirconium Refining Process Under EBM Conditions

One of the undoubted advantages of EBM is the combination of high temperature and vacuum environment for chemical reactions. The electron beam melting and refining process occurs mainly on the reaction surface of the liquid metal (its interface with the vacuum) [14]. Therefore, the main parameters that will affect the removal of impurities are the temperature, the physical state of the impurities during refining, and the mass transfer of molten or solid particles to the reaction surface, which depends on their density [25].

From a thermodynamic point of view, under EBM conditions, liquid metal is a multicomponent system with metal impurities, their oxides and carbides, which, depending on the temperature, will be in a solid, liquid or gaseous state.

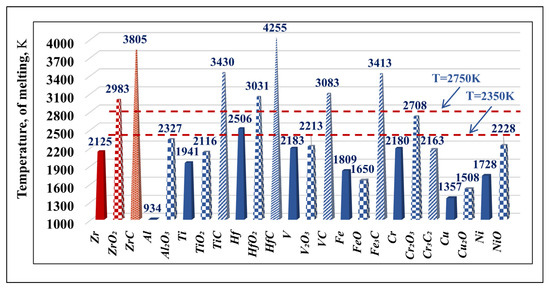

Figure 2 shows the melting temperatures of pure metals (Zr, Al, Ti, Hf, V, Fe, Cr, Cu, Ni), their oxides (ZrO2, Al2O3, TiO2, HfO2, V2O3, FeO, Cr2O3, Cu2O, NiO), and carbides (ZrC, TiC, HfC, VC, Fe3C, Cr2C3). The operating temperature range (2350–2750 K) of the EBMR process of technogenic Zr is marked in the figure with dashed lines.

Figure 2.

The melting temperatures of metals, oxides, and carbides in the studied material.

It can be observed that in the entire studied temperature range, the metal impurities such as Al, Ti, V, Fe, Cr, Cu, Ni will be in a liquid state. At T = 2506 K, hafnium will pass from a solid to a liquid state. The oxides Al2O3, TiO2, V2O3, FeO, Cu2O, and NiO will also be in a liquid state. At a temperature of 2708 K, chromium oxide also passes into the liquid state. The melting temperatures of the oxides ZrO2, HfO2 as well as the carbides significantly exceed the maximum operating temperature, i.e., they will remain in a solid state. According to [26], the melting temperatures of ZrC and HfC can vary by about 30–40 K depending on their stoichiometric composition with respect to carbon. TiC, VC, and Fe3C can be seen to have high (over 3000 K) melting points, suggesting that they will remain in the solid state. The only exception is chromium carbide (Cr3C2), which has a low melting point (2163 K).

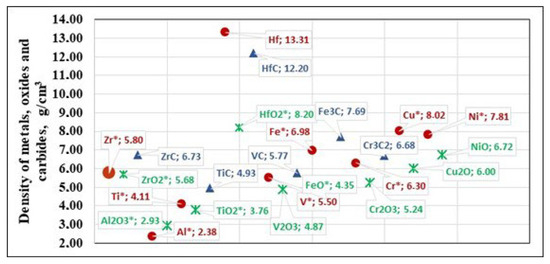

The densities of liquid metals and some oxides measured at high temperatures are shown in Figure 3 (marked with *). For the studied temperature range, the density of liquid Al2O3 is 2.93 g/cm3 [27,28]. The density of liquid TiO2, measured at T = 2200 K, is 3.76 g/cm3 [29]. The density of liquid FeO varies and is approximately ~4.35 g/cm3 [30], which is due to the instability of the melt formed during melting, which can oxidize or decompose at high temperatures.

Figure 3.

Density of zirconium, metallic impurities, and compounds of these impurities present in technogenic Zr.

There is no data in the literature on the density of the liquid oxides V2O3, Cu2O, and NiO, as these oxides decompose at high temperatures close to their melting points [27]. The release of oxygen changes the liquid phase composition and limits the formation of a stable liquid phase, which complicates density measurements. In the case of Cr2O3, in addition to the high melting temperature, the possibility of oxide disproportionation also has an influence, which hinders density measurements.

We can infer from the available evidence (Figure 3) that within the studied temperature range, most impurities present in liquid Zr are of lower density. These are the liquid metal impurities Al, Ti, and V, the oxides ZrO2, Al2O3, TiO2, FeO, V2O3, Cr2O3, and the carbides TiC and VC. In practice, this means that these impurities concentrate on the surface of the liquid zirconium, where they can be more easily removed either by evaporation or by the chemical reactions occurring during melting and refining.

Thermodynamic analysis of possible chemical interactions occurring during the refining of technogenic zirconium from metallic (Al, Ti, Hf, V, Fe, Cr, Cu, Ni) and non-metallic impurities (O, C) under EBM conditions was conducted based on the equilibrium constant and Gibbs free energy (ΔG). Calculations were performed using the HSC Chemistry ver.10 professional software, “Reaction Equation” module, considering the physical state of each impurity during refining [31].

The thermodynamic characteristics enthalpy (H), entropy (S), and specific heat capacity (Cp) of the respective elements, required for the calculations, were taken from the program database. The indices (s), (l), and (g) mean that at a given temperature the substance is in a solid, liquid, or gaseous state, respectively.

From a thermodynamic point of view, the vapor pressure of the metallic impurities (pMe) and their compounds present in the base metal plays a decisive role in the refining process [14]. Depending on the thermodynamic parameters (temperature and pressure in the vacuum chamber) and the physical state of the impurities, refining can proceed by degassing (when (pMe) > (pZr)) and distillation (evaporation of more volatile compounds of the metal components).

In some cases, non-volatile metallic impurities form volatile components with high vapor pressure and are removed by distillation.

(pMeO) > (pMe) > (pZrO2) > (pZr)

If the conditions (1) are not satisfied for the impurities, i.e., if (pZrO2) > (pMeO); (pZrO2) > (pMe) or (pZrO2) < (pZr), the losses of the base metal (Zr) are higher and the refining process is not efficient.

The calculations were performed for the operating temperatures 2350 K, 2450 K, 2550 K, and 2750 K and a constant pressure in the vacuum chamber 1 × 10−3 Pa. These parameters correspond to the real melting and refining conditions of technogenic Zr in the laboratory electron beam furnace ELIT-60.

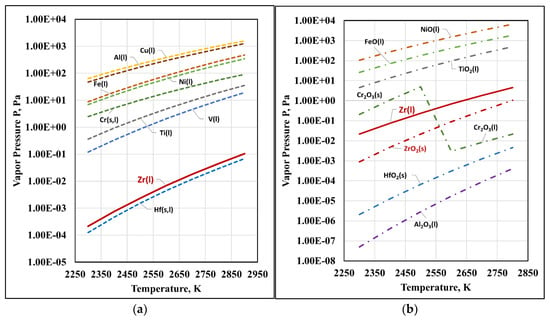

Figure 4 shows the numerical values of the vapor pressure of liquid zirconium, metal impurities, and their oxides. No thermodynamic data were found for ZrC(g), TiC(g), VC(g), and Cr3C2(g). The calculated values of pZrC for the studied temperature range are of the order of 10−4 Pa; therefore, they are not marked in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Vapor pressure of zirconium, metal impurities (a), and their oxides (b).

The analysis of the obtained results shows that in the studied temperature range, the vapor pressure of the metal impurities present in technogenic zirconium is nearly three orders of magnitude higher than that of liquid Zr. Within the entire temperature range, the partial pressures of impurities can be arranged in the following order: pCu(l) > pAl(l) > pNi(l) > pFe(l) > pCr(s,l) > pTi(l) > pV(l) > pZr(l). Therefore, the relevant impurities will be removed by degassing. The vapor pressure of hafnium is lower than that of zirconium (pHf(l) < pZr(l)), making the process thermodynamically impossible. However, the difference in the calculated values of pZr and pHf is insignificant, which, in practice, shows that under certain conditions, hafnium can be removed together with the base metal (Zr). This is an undesirable process leading to losses of zirconium.

The vapor pressure of the oxides ZrO2(s), Cr2O3(s,l), HfO2(s), and Al2O3(l) is significantly lower than that of liquid zirconium. Therefore, their removal by evaporation is thermodynamically impossible. In contrast to these oxides, the oxides NiO(l), FeO(l), and TiO2(l) have a higher vapor pressure than that of zirconium (pNiO(l) > pFeO(l) > pTiO2(l) > pZr(l)), which makes the process of their removal by distillation, thermodynamically probable.

The refining process efficiency of a multicomponent metal system can be calculated by the relative volatility α [32], which is determined by the equation:

where pZr and pi are the vapor pressure of zirconium and the impurity, respectively, MZr and Mi are the molecular masses of zirconium and the inclusion (metallic and oxide), respectively.

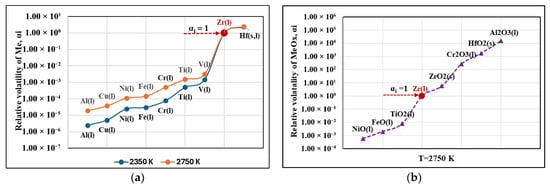

The values of αi of the metal impurities at the minimum (2350 K) and maximum (2750 K) operating temperatures and of the metal oxides at T = 2750 K calculated by Equation (2) are shown in Figure 5. The parameter αi for the metal impurities varies within the range 10−6–101, and for the metal oxides at the highest operating temperature αi varies from 10−3 to 104.

Figure 5.

Values of the relative volatility αi for the metal impurities in zirconium at temperatures of 2350 K and 2750 K (a), and metal oxides at a temperature of 2750 K (b).

The analysis of the obtained results shows that at T = 2350 K and T = 2750 K, the relative volatility of aluminum, copper, nickel, iron, chromium, titanium, and vanadium is significantly less than 1 (αi << 1), which indicates their high tendency to volatilize. In contrast to these metal impurities, αHf > 1, which in practice means that the relative volatility of this impurity is lower than that of zirconium.

The calculated values of the relative volatilities of oxide impurities show that only NiO, FeO, and TiO2 have αi << 1 and therefore, only these oxides can be removed by distillation. The calculated values of αi for the oxides ZrO2, Cr2O3, HfO2, and Al2O3 are much higher than that of the parent metal zirconium. This indicates that their removal under EBMR conditions is inefficient.

Thermodynamic assessment of possible chemical interactions in the Zr-Mei-O system was made based on the following equations:

where ΔGT, Zr/ZrO2, ΔGT, Mei/MeiOx, and ΔGT are the Gibbs free energies.

Zr(l) + 2[O] = ZrO2(s,l) + ΔGT, Zr/ZrO2

Mei(s,l) + [O] = MeiO(s,l,g) + ΔGT, Mei/MeiOx

ZrO2(s) + 2Mei(s,l) = 2MeiO(s,l) + Zr(l) + ΔGT

Calculations were carried out at temperatures of 2350 K, 2450 K, 2550 K, and 2750 K and working pressure in the vacuum chamber of 1 × 10−3 Pa, taking into account the aggregate state of the metal impurities and their oxides.

When considering the practical side, the process is considered thermodynamically probable if the values of ΔGT < −60 kJ/mol [33].

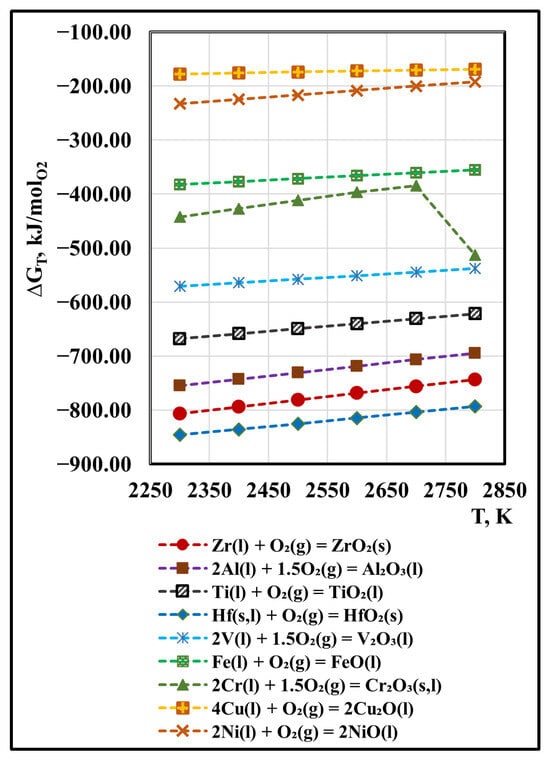

Figure 6 shows the temperature dependence of the free energy of the oxidation reactions of zirconium (ΔGT, Zr/ZrO2) and metal impurities (ΔGT, Mei/MeiOx). They are calculated for one mole of oxygen.

Figure 6.

Influence of the temperature on ΔGT of oxidation reactions of Zr(l) and metal impurities Mei(s,l) under vacuum conditions.

It can be seen that with increasing temperature, the ΔGT of oxidation of Zr(l) to ZrO2(s) increases from −806 kJ/molO2 to −744 kJ/molO2. Of the impurities present in zirconium, hafnium has the greatest affinity for oxygen. With increasing temperature, the ΔGT values of HfO2(s) increase from −845 kJ/molO2 to −792 kJ/molO2 and approach those of the oxidation of zirconium. During the transition of hafnium from solid to liquid state, the change in free energy is ≈ −20 kJ/molO2.

Based on the obtained dependences, it can be concluded that within the entire studied temperature range, the possibility of oxide formation decreases in the order Al2O3 > TiO2(l) > V2O3(l) > Cr2O3(s,l) > FeO(l) > NiO(l) and Cu2O(l).

A characteristic of the phase transition bend in the slope of the curve is observed in the temperature dependence ΔGT = f(T) for the oxidation of chromium to dichromium trioxide. In this case, it is due to the phase transition of solid Cr2O3(s) into the liquid Cr2O3(l) state.

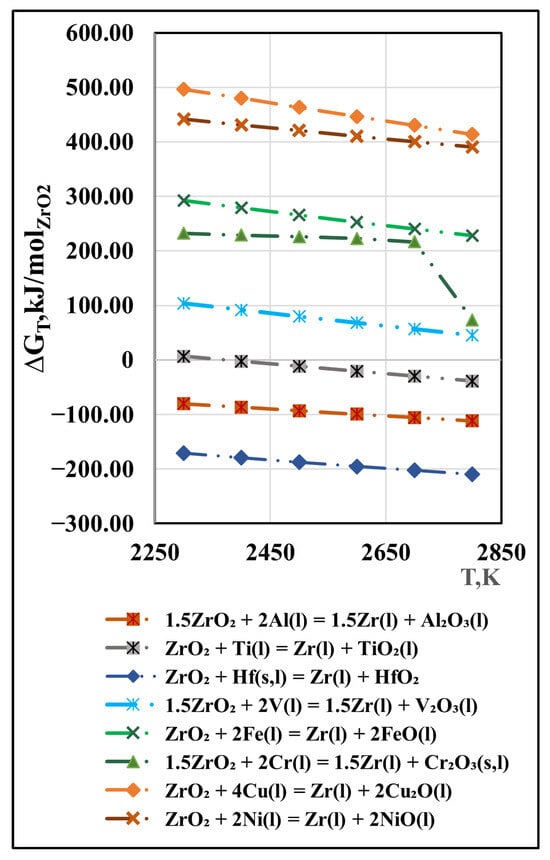

Of the oxides present in the Zr-Mei-O system, the most stable are HfO2(s) and ZrO2(s). Since the hafnium content in the studied material is very small, it is not of interest from a practical point of view, unlike zirconium dioxide. The possibility of chemical interactions between ZrO2(s) and metal impurities is described by Equation (5). The calculated free energy values (ΔGT) in the studied temperature range are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Free energy for interaction between ZrO2 and metal impurities in vacuum.

The calculated Gibbs free energy values indicate that in the studied system, only the reactions of zirconium dioxide with the impurities Hf(s,l) and Al(l) are thermodynamically probable. Reaction with Ti(l) is theoretically possible at all operating temperatures above 2550 K. The positive values of ∆G of the interaction reactions between ZrO2(s) and the impurities V(l), Cr(l), Cu(l), and Ni(l) mean that these reactions are thermodynamically impossible under the studied conditions.

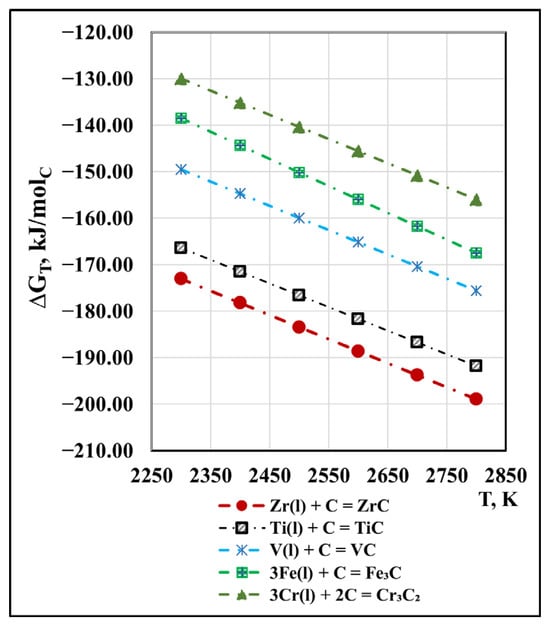

ICP analysis of technogenic zirconium confirmed the presence of carbon, suggesting that some of the impurities may be present in the form of carbides. The following carbides are possible in the system: ZrC, HfC, VC, Fe3C, and Cr3C2. The calculated values of the Gibbs energy of their formation, except for HfC, for which thermodynamic data are missing, are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Influence of the temperature on ΔGT of carbide formation under vacuum conditions.

It can be observed that within the studied temperature range, ZrC is the most stable, and Cr3C2 is the most unstable. Unlike oxides, with increasing temperature, the thermodynamic probability of carbide formation increases only slightly (by ≈20–30 kJ/molC).

According to the studies in [34], zirconium carbide forms non-stoichiometric compounds with carbon that can dissolve, albeit small, amounts of oxygen. For example, at a temperature of 2123 K, ZrC can form a solid solution with the composition ZrC1-xOx, where x = 0.26. With a further increase in temperature, removal of oxygen and carbon is possible by the formation and release of gases CO(g) and CO2(g). The presence of these gases was established in [35] during heating the samples in graphite pots within the temperature range of 2773 K–3073 K in an atmosphere of helium. Similar compounds can also be formed by hafnium.

In our study, the thermodynamic assessment of the possibility of removing carbon and oxygen from technogenic Zr was based on the following equations:

ZrC(s) + MeiO(s,l,g) = ZrOZrO2(l) + Mei(l) + CO(g)

ZrC(s) + 2MeiO(s,l,g) = ZrO2(l) + Mei(l) + CO2(g)

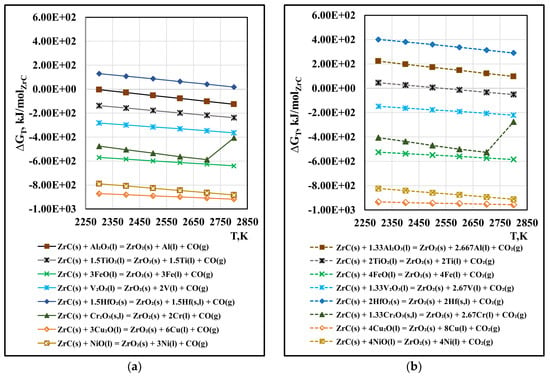

The calculated values of the Gibbs free energy for the studied operating temperatures and vacuum are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Free energy for interaction between ZrC(s) and oxides of metal impurities in vacuum: (a) reactions with forming of CO(g); (b) reactions with forming of CO2(g).

The analysis of the obtained results shows that within the studied temperature range, the interaction reactions of ZrC with the oxides FeO(l), V2O3(l), Cr2O3(s,l), Cu2O(l), TiO2(l), and NiO(l), which form gaseous CO(g) (Figure 9a) are thermodynamically probable. The probability of interaction with Cu2O(l) is the highest and the lowest is with TiO2(l). When increasing the temperature above 2400 K, the reaction between ZrC(s) and Al2O3(l) is also likely to occur. The interaction reaction between ZrC(s) and HfO2(s) is thermodynamically impossible under the conditions considered.

The calculated ∆G values of the interaction reactions of ZrC(s) with oxides with the formation of CO2(g) are shown in Figure 9b. It can be seen that the calculated values of the Gibbs free energy for the oxides FeO(l), V2O3(l), Cr2O3(s,l), Cu2O(l), and NiO(l) are ~30–40 kJ/molZrC higher than the values for the same reactions with the formation of CO(g). The positive values for the reactions of interaction of ZrC(s) with HfO2(s) and Al2O3(l) indicate that they are thermodynamically impossible in the entire temperature range, while the reaction with TiO2(l) is possible only at the highest operating temperature (2750 K).

The conducted thermodynamic analysis indicates that the metallic impurities (Al, Cu, Ni, Fe, Cr, Ti, and V) will be removed mainly by degassing. The high vapor pressure of NiO(l), FeO(l), and TiO2(l) shows that they can be removed by distillation.

The non-metallic impurities present in technogenic zirconium—oxygen and carbon—will most likely be removed in the form of CO(g) and CO2(g), which are products of the interaction between ZrC and TiO2, FeO, V2O3, Cr2O3, Cu2O, and NiO. At the maximum operating temperature (2750 K), removal of Al2O3 with the formation of gaseous carbon monoxide is also possible.

An impurity that is difficult to remove is hafnium, as it has similar thermodynamic characteristics to those of zirconium metal, zirconium oxide, and zirconium carbide.

Although the reaction between ZrO2(s) and Hf(s,l) is thermodynamically probable, the HfO2(s) formed by this reaction is a very stable compound with a high melting point. During smelting and refining processes, Hf can be removed together with zirconium, which is an undesirable process leading to losses of the parent metal.

3.2. Refining Efficiency at EBM of Zirconium Scrap

The chemical compositions of ingots obtained after EBMR of technogenic zirconium under different technological regimes are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Process parameters and chemical composition of ingots before and after refining of technogenic zirconium during EBM.

For easier interpretation of the obtained results, graphical dependences for the influence of temperature and refining time on the degree of impurity removal (βi) from liquid zirconium have been constructed.

The values of the removal rate (βi) of the i-th element are calculated from:

where are the initial and final concentrations of the i-th element in the studied material, respectively.

The removal rates of Hf, Cu, and Ni were not calculated, as their contents in the initial zirconium are very low, being less than 50 ppm even at the lowest operating temperature (2350 K) and 10 min refining time (τ).

The content of Cr in the initial sample is also low (450 ppm). At the lowest operating temperature, as well as at T = 2450 K and τ = 10 min, the chromium content in the resulting ingots allows to calculate the removal degree of this impurity.

From a thermodynamic point of view (Figure 9), metallic hafnium, as well as HfO2, cannot be removed by evaporation before zirconium, because their vapor pressure is lower than that of Zr. Zirconium and hafnium have full mutual solubility in both the solid and liquid states [36], i.e., hafnium can be evaporated together with zirconium.

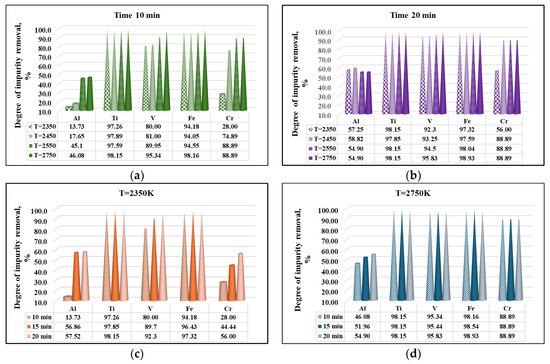

The influence of temperature and residence time on the removal rates of Al, Ti, V, Fe, and Cr impurities during the e-beam refining process is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Effect of melting temperature (a,b) and refining duration (c,d) on the removal rate of impurities present in technogenic zirconium.

The analysis of the obtained results shows that aluminum has the lowest removal rate. When increasing the temperature, and at a refining time of 10 min, the βAl value increases from 13.73% to 46.08%. At the highest operating temperature (T = 2750 K), extending the refining time to 20 min increases the removal rate of this impurity by only ~8.82%. The low removal rate of Al indicates that this impurity is present in liquid zirconium mainly in the form of oxide (Al2O3). The maximum removal rate of aluminum (58.82%) was obtained at T = 2450 K and τ = 20 min.

Our thermodynamic analysis showed that, unlike liquid aluminum (Al(l)), aluminum oxide (Al2O3) cannot be removed by evaporation (distillation), because its vapor pressure is much lower than that of the liquid zirconium (Figure 4b).

A thermodynamically possible reaction that can be used for Al2O3 removal is the chemical reaction with ZrC (Figure 9a), accompanied by the release of gaseous CO(g) and evaporation of the resulting liquid aluminum (Al(l)), which has a high vapor pressure (Figure 4a). The calculated values of the Gibbs energy for a similar reaction, but with the formation of CO2(g), show that it is thermodynamically impossible (Figure 9b).

Unlike aluminum, more than 97% of Ti(l) and 94% of Fe(l) are removed even at a low working temperature (T = 2350 K) and τ = 10 min (Figure 10a). With increasing temperature up to 2750 K, βTi and βFe increase to 98.15% and 98.93%, respectively. The influence of refining time is weakly expressed in this case (Figure 10d).

Figure 10 indicates that both temperature and refining time have a significant influence on the degree of vanadium removal. At lower operating temperatures (T = 2350 K), the influence of refining time is greater. Increasing the refining time from 10 min to 20 min leads to an increase in the degree of removal by 12.3% (Figure 10c). The maximum degree of vanadium removal (95.83%) is obtained at T = 2750 K and τ = 20 min (Figure 10d).

An impurity that is also difficult to remove from technogenic zirconium is chromium. Figure 10c shows that at T = 2350 K with an extension of the refining time from 10 min to 20 min, the value of βCr increases significantly from 28.0% to 56.0%. The process of chromium removal continues with increasing temperature and refining time and the degree of refining reaches a value of 88.89% at a temperature of 2750 K.

Unlike liquid chromium, which has a high vapor pressure (Figure 4a), Cr2O3(s) cannot be removed by distillation, since the vapor pressure of the oxide is much lower than that of liquid zirconium (Figure 4b). From a thermodynamic point of view, Cr2O3(s) can react with zirconium carbide (Figure 9), forming liquid chromium (Cr(l)), which can be removed by degassing.

3.3. Microstructure of Samples Obtained After EBMR of Technogenic Zirconium

The information available in the literature on the influence of different types of impurities on the macro- and micro-structure of zirconium is quite scarce and it concerns different composition of initial technogenic materials and melting conditions [9,10].

At room temperature, zirconium has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure, known as the α-phase, which at 1136 K transforms into a body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure, the β-phase. Zirconium exists in this phase until the melting point is reached. According to [37], the α area consists of a set of α-phase lamellae with a specific orientation. Out of six possible variants, five different orientations of HCP packets were found. The existence of structural heredity in the Zr single crystal after the α → β → α transformation cycle at a heating and cooling rate of 4–5 K/s was established.

The presence of various impurities affects both the α→β phase transition temperature and the formation of intermetallic compounds. For example, zirconium and aluminum form an intermetallic compound (Al3Zr), which affects the grain size and mechanical properties of zirconium [38].

The influence of oxide phases of aluminum, titanium, and chromium can be assessed based on phase diagrams with ZrO2. A study of the Al2O3-ZrO2 phase diagram under inert atmosphere and vacuum conditions shows that below the eutectic temperature (2139 K), up to 1.1 ± 0.3 mass. % Al2O3 is dissolved in a solid solution of zirconium [39]. This dissolution affects the temperature of the α→β phase transition.

The solubility of Ti and Cr in ZrO2 is also significant. Both impurities change the temperature of the α-phase transformation into the β-phase. In the ZrO2-TiO2 system [40], an intermetallic compound ZrTiO4 is also formed, which improves the thermal insulation properties of nanoceramic coatings used in nuclear reactors.

Dichromium trioxide (Cr2O3) forms an extensive area of solid solutions in the cubic, α-phase of ZrO2 up to the eutectic temperature (2113 K), after which it decomposes into the tetragonal β-phase [41].

Hafnium and zirconium have full mutual solubility in both the solid and liquid states [36] with the α→β phase transformation temperature being determined by the ratio between the two metals.

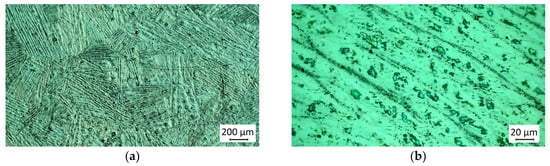

The macro- and microstructure of technogenic zirconium before electron beam melting and refining is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Macrostructure (a) and microstructure (b) of technogenic zirconium.

From the conducted microscopic observation, it is established that the macrostructure of technogenic zirconium is composed of differently oriented light lamellae corresponding to the α-phase. At higher magnification (Figure 11b), it can be seen that these lamellae are surrounded by crystallized dark, non-homogeneous melts. This non-homogeneity is due to the presence of solid solutions, intermetallic compounds, and precipitates of different compositions, formed between zirconium and the impurities Al, Fe, Ti, and V (Table 2) present in it. The formed solid solutions, high-temperature eutectics, and intermetallic compounds affect the temperature of the α→β phase transition.

The overall amount of other impurities, such as Hf, Cr, Cu, and Ni, is low (0.155%) and therefore their influence on the microstructure of zirconium can be neglected. The content of oxygen and carbon is of the same order.

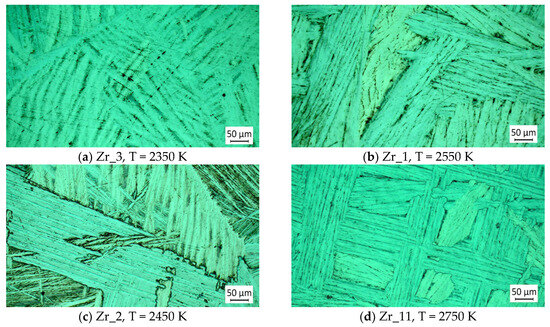

Figure 12 shows the microstructure of zirconium ingot samples obtained at different temperatures and a retention time of 10 min.

Figure 12.

Influence of the electron beam melting temperature on the microstructure of zirconium at τ = 10 min.

It can be observed that with increasing the temperature during e-beam melting, the lamellae are gradually destroyed, and the zirconium crystals are mainly formed from the α-phase. At the boundaries of the forming crystals, a gradual reduction in the dark phases is observed, although their volume still remains significant.

The chemical analysis of the samples indicated that with the increase in the melting temperature from 2350 K to 2750 K, the purity of the obtained zirconium slightly increases, from 99.447% to 99.705% for a retention time of 10 min (Table 2). For the same refining time, aluminum has the lowest removal rate—13.73% at T = 2350 K, which increases to 46.08% at T = 2750 K (Figure 10). The degree of Cr removal under the same conditions is also low: 28.0% and 88.89%, respectively (Figure 10a), but since the amount of this impurity in the initial material is low (450 ppm), its influence can be neglected.

The degree of removal of other impurities (Ti, V, Fe) present in zirconium at the highest operating temperature (2750 K) is more than 95–98% (Figure 10c). Therefore, the aluminum present in zirconium exerts the main influence on its microstructure.

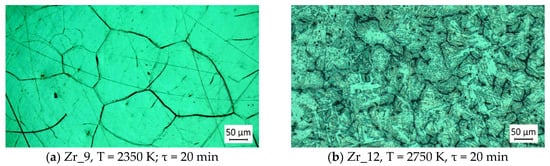

The microstructures of samples obtained at the lowest and highest operating temperatures and a longer retention time of 20 min are shown in Figure 13. The purity of the obtained zirconium is 99.726% and 99.756%, respectively, and the difference in purity is within the limits of the error that can be allowed in the ICP analysis of the impurities.

Figure 13.

Effect of extended refining time on the microstructure of zirconium.

Comparing the microstructures of the samples shows that the extension of the refining time leads to the fragmentation of zirconium crystals. It is possible that this is due to the formation of the intermetallic compound Al3Zr. A similar conclusion was made in [38], where the presence of Al3Zr and its influence on the grain size was found when studying Al-Zr alloys.

3.4. Micro-Hardness Measurement

A number of studies on the microstructure and mechanical properties of zirconium alloys obtained by different methods are described in the literature [42,43,44,45]. One of the main mechanical characteristics is micro-hardness, which depends both on the type and content of impurities and on changes in the zirconium microstructure.

Table 3 presents the average micro-hardness values measured by the Vickers (HV) method, as well as the corresponding standard deviation values at a load of 0.2 kgf/mm2 and a dwell time of 10 s of the zirconium specimens obtained under different technological modes of EBMR.

Table 3.

Micro-hardness of ingots produced by EBM.

The analysis of the results shows that the micro-hardness of the initial technogenic zirconium is relatively high (2907 MPa), which is due to the high content of impurities. Increasing the temperature of the EBMR process leads to a gradual decrease in the micro-hardness from 2706 MPa at T = 2350 K to 2550 MPa at T = 2750 K. This trend is the result of two competing effects. The grain refinement at higher temperatures is expected to increase the hardness, according to the Hall-Petch relationship, which is known to be valid for alpha-zirconium [46]. However, a stronger, opposing effect also occurs: the higher temperature removes more strengthening impurities, which causes the material to soften. Our observation that the finer-grained sample Zr_12 is actually softer than the coarser-grained Zr_9 confirms that this purification-induced softening is the dominant mechanism, and its effect is greater than that of the grain size hardening. The effect of refining time on micro-hardness is negligible. The micro-hardness values of the refined zirconium samples measured in this study are higher than the data available in the literature. It was found that EBM refining of iodide zirconium reduces the micro-hardness from 1200 MPa to 800 MPa [9], and for calcithermal zirconium, the Brinell hardness decreases from 2250 MPa to 1370 MPa after two EBM cycles [47], which was due to a softening effect caused by grain refinement and/or annealing.

The higher micro-hardness values measured in the present study after EBM of technogenic zirconium are the result of the low degree of removal of aluminum, which can remain in zirconium both in the form of the intermetallic compound Al3Zr and in the form of Al2O3, which has a low vapor pressure and is not removed during refining.

4. Conclusions

Based on the conducted theoretical and experimental research, the possibility of removing metallic (Al, Ti, Hf, V, Fe, Cr, Cu, Ni) and non-metallic (O, C) impurities from technogenic zirconium by EBMR was evaluated. The obtained results allow the following conclusions to be made:

- Impurities present in technogenic zirconium will evaporate in the following order: Cu, Al, Ni, Fe, Cr, Ti, and V, based on the calculated values of their vapor pressures (pCu(l) > pAl(l) > pNi(l) > pFe(l) > pCr(s,l) > pTi(l) > pV(l) > pZr(l)) in the studied temperature range (2350–2750 K). Under certain conditions, hafnium can be removed together with the base metal Zr due to the slight difference in pZr and pHf values, which is an undesirable process leading to losses of the base metal.

- Removal by evaporation of ZrO2(s), Cr2O3(s,l), HfO2(s), and Al2O3(l) is thermodynamically impossible, due to their significantly lower vapor pressure than that of the liquid zirconium. The removal of these oxides under EBM conditions is also ineffective due to the much larger values of their relative volatilities (αi) than that of the base metal (Zr).

- NiO, FeO, and TiO2 can be removed by distillation based on the calculated values of their vapor pressures (pNiO(l) > pFeO(l) > pTiO2(l) > pZr(l)) and their relative volatilities.

- Non-metallic impurities (O, C) present in technogenic Zr can be removed in the form of CO(g) and CO2(g), which are products of interaction between ZrC and Cu2O, NiO, FeO, Cr2O3, V2O3, and TiO2.

- The maximum overall refining efficiency is 87%, and the purity of Zr is 99.756%. Of the impurities present in technogenic zirconium, the degree of removal of Al (54.9%) is the lowest, which mainly affects the microstructure and micro-hardness of the ingots obtained after refining. Al can remain in zirconium both in the form of the intermetallic compound Al3Zr and in the form of Al2O3, which has a low vapor pressure and is not removed during refining.

The obtained results provide an updated, in-depth scientific understanding of the purification process of technogenic zirconium by electron beam melting and help optimize this technology for its use across a range of demanding, high-value applications such as nuclear energy, biomedical implants, etc.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V. and V.S.; methodology, K.V.; validation, V.S., E.M. and M.N.; formal analysis, V.S., K.V., I.M., M.N. and E.M.; investigation, K.V., V.S., E.M. and P.I.; resources, M.N., E.M. and P.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V. and V.S.; writing—review and editing, K.V., V.S. and E.M.; visualization, V.S., I.M. and E.M.; supervision, K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to V. Vassileva, S. Toshev, R. Nikolov, and D. Manoilov for their technical assistance in processing the samples and to R. Ratheesh, R.C. Reddy, and A. Kumar for performing the elemental analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gupta, C.K. Chemical Metallurgy: Principles and Practice; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; ISBN 3-527-30376-6. [Google Scholar]

- Garde, A.M. Current Perspectives on Zirconium Use in Light Water Reactor Fuel and Its Continued Use in Nuclear Power; ASTM Special Technical Publication: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023; Volume STP 1645, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhachev, A.; Yelatontsev, D.; Kharytonova, O.; Grechanyuk, N. Production of Neutron-Absorbing Zirconium-Boron Alloy by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis and Its Refining via Electron Beam Melting. Alloys 2024, 3, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Rupa, P.V.; Kumar, N.; Singh, R.N.; Choudhury, P.; Chakravartty, J.K. Preparation and characterization of Nb-1Zr-0.1C alloy suitable for liquid metal coolant channels of high temperature reactors. J. Nucl. Eng. Radiat. Sci. 2021, 7, 011603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Chaharmahali, R.; Keshavarz, M.K.; Babaei, K. Surface characterization of bioceramic coatings on Zr and its alloys using plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO): A review. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 25, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Niinomi, M. Low-cost surface modification of a biomedical Zr-2.5Nb alloy fabricated by electron beam melting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 143, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yao, M.; Chen, Z.; Xu, S.; Hu, L. Research Progress of Zirconium-based Biomedical Alloys. Cailiao Daobao/Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 24020141. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, D.; Liu, M.; Hao, H.; Sun, X.; Geng, Y.; You, F.; Dou, H.; Li, H.; Dong, Z. Sustainable supply of critical materials for water electrolysers and fuel cells. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, M.M. High pure zirconium. Probl. At. Sci. Technol. 2018, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Markelov, V.A.; Malgin, A.G.; Filatova, N.K.; Novikov, V.V.; Shevyakov, A.Y.; Gusev, A.Y.; Shelepov, I.A.; Golovin, A.V.; Ugryumov, A.V.; Dolgov, A.B.; et al. Fabrication of E110 Alloy Fuel Rod Claddings from Electrolytic Zirconium Base with Removing Fluorine Impurity for Providing Resistance to Breakaway Oxidation in High-Temperature Steam; ASTM Special Technical Publication: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021; Volume STP 1622, pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhao, H.; Hu, C.; Liu, L.; Chang, Z. Research Progress in Solvent Extraction and Separation of Nuclear Grade Zirconium and Hafnium. Mater. China 2023, 42, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Che, Y.; Shu, Y.; He, J.; Song, J.; Yang, B. Review-Preparation of Zirconium Metal by Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 062508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orino, T.; Cao, Y.; Tashiro, R.; Takeyama, T.; Gericke, R.; Tsushima, S.; Takao, K. Utility of Interchangeable Coordination Modes of N,N′-Dialkyl-2,6-pyridinediamide Tridentate Pincer Ligands for Solvent Extraction of Pd(II) and Zr(IV) from High-Level Radioactive Liquid Waste. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 24647–24661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, G.; Koleva, E.; Vutova, K.; Vasileva, V. Experimental and theoretical studies of electron beam melting and refining. In Practical Aspects and Applications of Electron Beam Irradiation; Nemtanu, M., Brasoveanu, M., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2011; pp. 43–93. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. Refining tungsten purification by electron beam melting based on the thermal equilibrium calculation and tungsten loss control. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2015, 34, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vutova, K.; Vassileva, V.; Stefanova, V.; Amalnerkar, D.; Tanaka, T. Effect of electron beam method on processing of titanium technogenic material. Metals 2019, 9, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, M.; Mirji, K.V.; Prasad, V.S.; Baligidad, R.G.; Gokhale, A.A. Purification of niobium by electron beam melting. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2016, 35, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vutova, K.; Stefanova, V.; Iliev, P. Application of electron beam melting method for recycling of tantalum scrap. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 106505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.W.; Choi, S.H.; Sim, J.J.; Lim, J.H.; Seo, K.D.; Hyun, S.K.; Kim, T.Y.; Gu, B.W.; Park, K.T. Fabrication of 4N5 Grade Tantalum Wire from Tantalum Scrap by EBM and Drawing. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2019, 64, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, H.; Kunfeng, C.; Dongfeng, X. Research progress of high purity tantalum niobium. Inorg. Chem. Ind. 2024, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vutova, K.; Vassileva, V.; Stefanova, V.; Naplatanova, M. Influence of process parameters on the metal quality at electron beam melting of molybdenum. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on High-Temperature Metallurgical Processing, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 February 2020; The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, X.; Zhu, Z.; You, X.; Zhao, Z. Purification of molybdenum by electron beam bath smelting. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, M.; Stefanova, V.; Vutova, K. The effectiveness of electron beam melting for removing impurities from technogenic metal materials. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2024, 59, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, Z.; Yan, G.; Wang, L. Perpetration of Zr from ZrO2 by Aluminothermic Reduction. Xiyou Jinshu/Chin. J. Rare Met. 2021, 45, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Kalugin, A. Electron Beam Melting of Metals; Metallurgy Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 1980. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Perevislov, S.N.; Vysotin, A.B.; Shcherbakova, O.Y. Studying the properties of carbides in the system ZrC-HfC, TaC-ZrC, TaC-HfC. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 848, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Paradis, P.F.; Koyama, C. Thermophysical property measurements of refractory oxide melts with an electrostatic levitation furnace in the International Space Station. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 954126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, P.F.; Ishikawa, T.; Saita, Y.; Yoda, S. Non-contact thermophysical property measurements of liquid and under cooled alumina. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 43, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwell, D.B. The Density of Titanium (IV) Oxide Liquid. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74, 2718–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, O.L.G.; Skinner, L.B.; Benmore, C.J.; Tamalonis, A.; Weber, J.K.R. Structure of molten titanium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 094204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outotec. HSC Chemistry ver. 10; Outotec, Research Center Pori: Pori, Finland, 2025; Available online: https://www.metso.com/portfolio/hsc-chemistry (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Bobrov, U.P.; Virich, V.D.; Dimitrenko, A.E.; Koblik, D.V.; Kovtun, G.P.; Manjos, V.V.; Pilipenko, N.N.; Tancura, I.G.; Shterban, A.P. Refining of Ruthenium by electron beam melting. Vopr. At. Nauk. I Tekhniki Vac. Pure Mater. Supercond. 2011, 6, 11–17. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kubaschewski, O.; Alcock, C.B. Metallurgical Thermochemistry, 5th ed.; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ushakov, S.V.; Navrotsky, A.; Hong, Q.J.; van de Walle, A. Carbides and Nitrides of Zirconium and Hafnium. Materials 2019, 12, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Réjasse, F.; Rapaud, O.; Trolliard, G.; Masson, O.; Maître, A. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic evaluation of the C-Hf-O ternary system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 3757–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriata, J.P.; Bolcich, J.C.; Peretti, H.A. The Hf-Zr (Hafnium-Zirconium) System. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 1982, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlebnikova, Y.V.; Sazonova, V.A.; Rodionov, D.P.; Vil’danova, N.F.; Egorova, L.Y.; Kaletina, Y.V.; Solodova, I.L.; Umova, V.M. Formation of macro- and microstructure during the β→α transformation in zirconium single crystals. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2009, 108, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.E.; Mahfouz, M.G.; Gad-Elrab, H.G.; Doheim, M.A. Grain Refinement of Commercial Pure Aluminium by Zirconium. J. Eng. Sci. Assiut Univ. Fac. Eng. 2014, 42, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerebtsov, D.A.; Mikhailov, G.G.; Sverdina, S.V. Phase diagram of the system: Al2O3±ZrO2. Ceram. Int. 2000, 26, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilova, S.A.; Almjashev, V.I.; Stolyarova, V.L. Phase equilibria and materials in the TiO2-SiO2-ZrO2 system: A review. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2021, 12, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerebtsov, D.A.; Mikhailov, G.G.; Sverdina, S.V. Phase diagram of the system: ZrO2-Cr2O3. Ceram. Int. 2001, 27, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Lou, H.; Liang, T.; Dong, H.; Xu, D.; Song, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. The effect of impurities in zirconium on the formation and mechanical properties of Zr55Cu30Al10Ni5 metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 596, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Liu, Y.; He, G.; Lian, L. Microstructure and mechanical performance of zirconium, manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, R.; Zhu, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, R.; Yuan, T.; Liu, K. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloy Additively Manufactured by Laser Direct Energy Deposition. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2022, 1, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroonia, A.; Iravania, M.; Khajepoura, A.; King, J.M.; Khalifa, A.; Gerlich, A.P. Mechanical properties and microstructures in zirconium deposited by injected powder laser additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, S.V.; Rodriguez, P. Grain size dependence of the deformation behaviour of alpha zirconium. Can. Metall. Q. 1972, 11, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhazha, V.M.; V’yugov, P.N.; Lavrinenko, S.D.; Pilipenko, N.N. Vacuum Conditions and EBM of Zirconium. Voprosy atomnoj nauki i tehniki. Fizika radiacionnyh povreždenij i radiacionnoe materialovedenie 2006, 4/89, 144–151. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).