Thermodynamic and Experimental Analysis of the Selective Reduction of Iron by Hydrogen from the Kergetas Iron–Manganese Ore

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

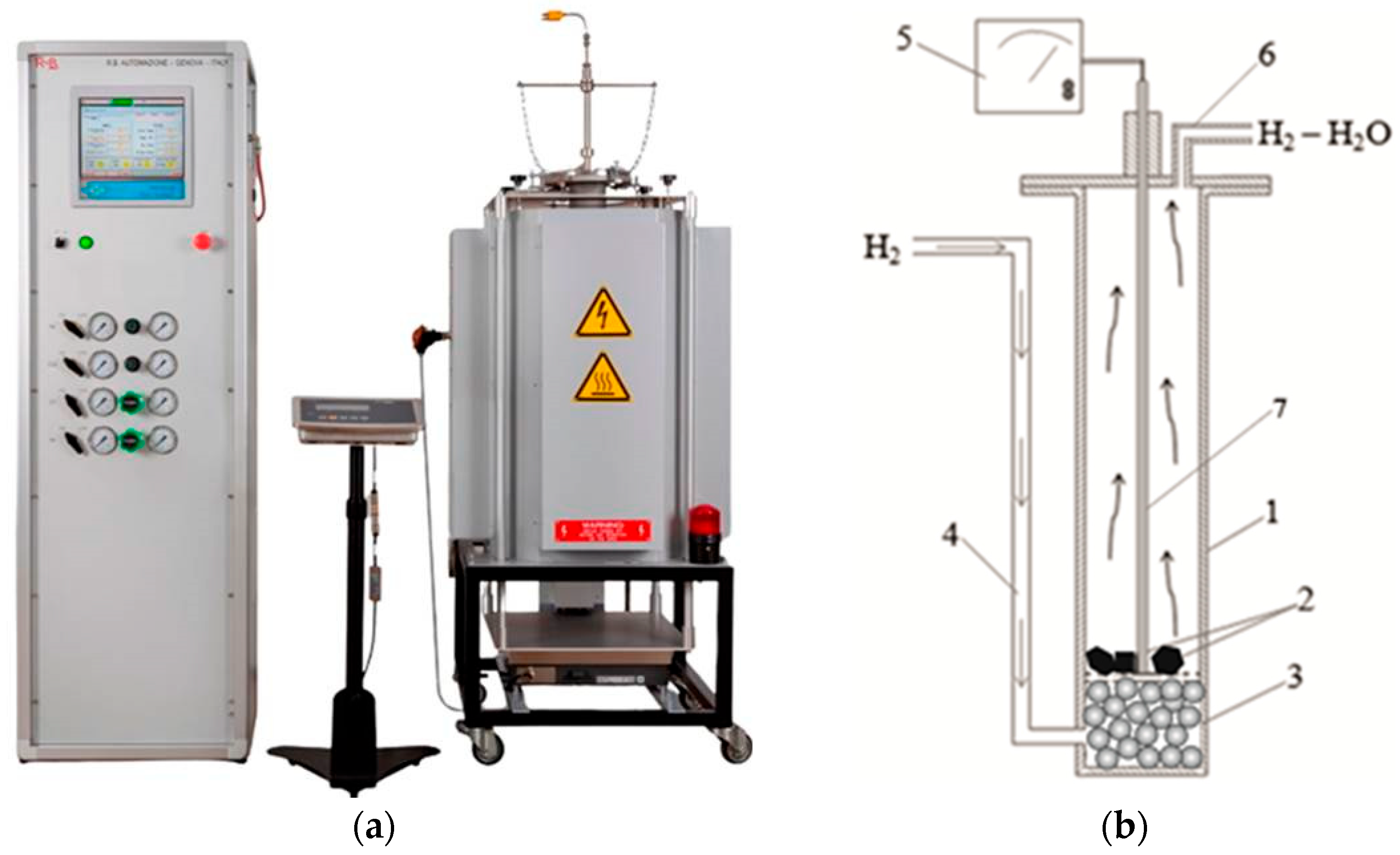

2.1. Solid-State Reduction of Iron–Manganese Ore

2.2. Phase and Microstructural Analysis

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

2.4. Object of the Study

3. Results

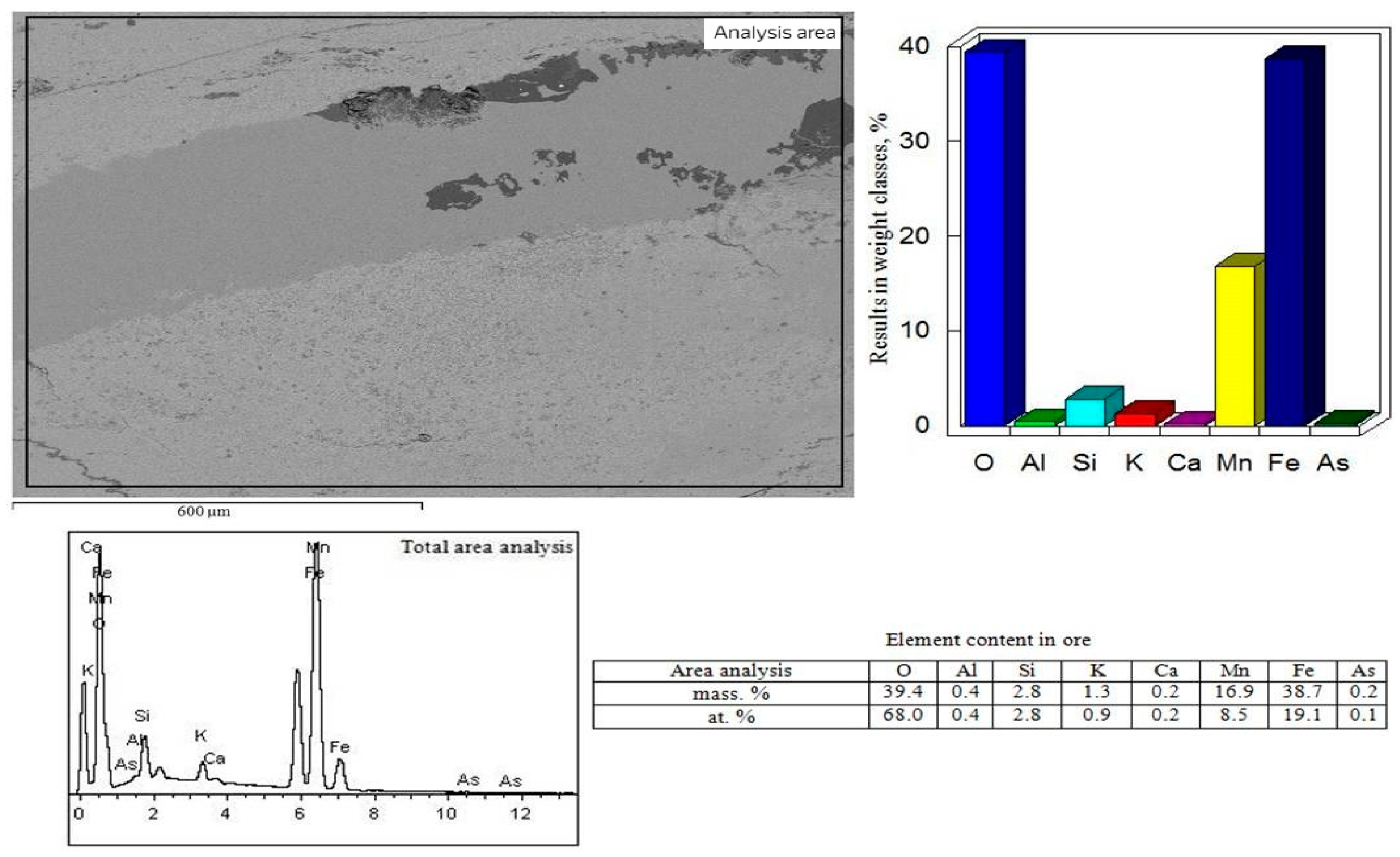

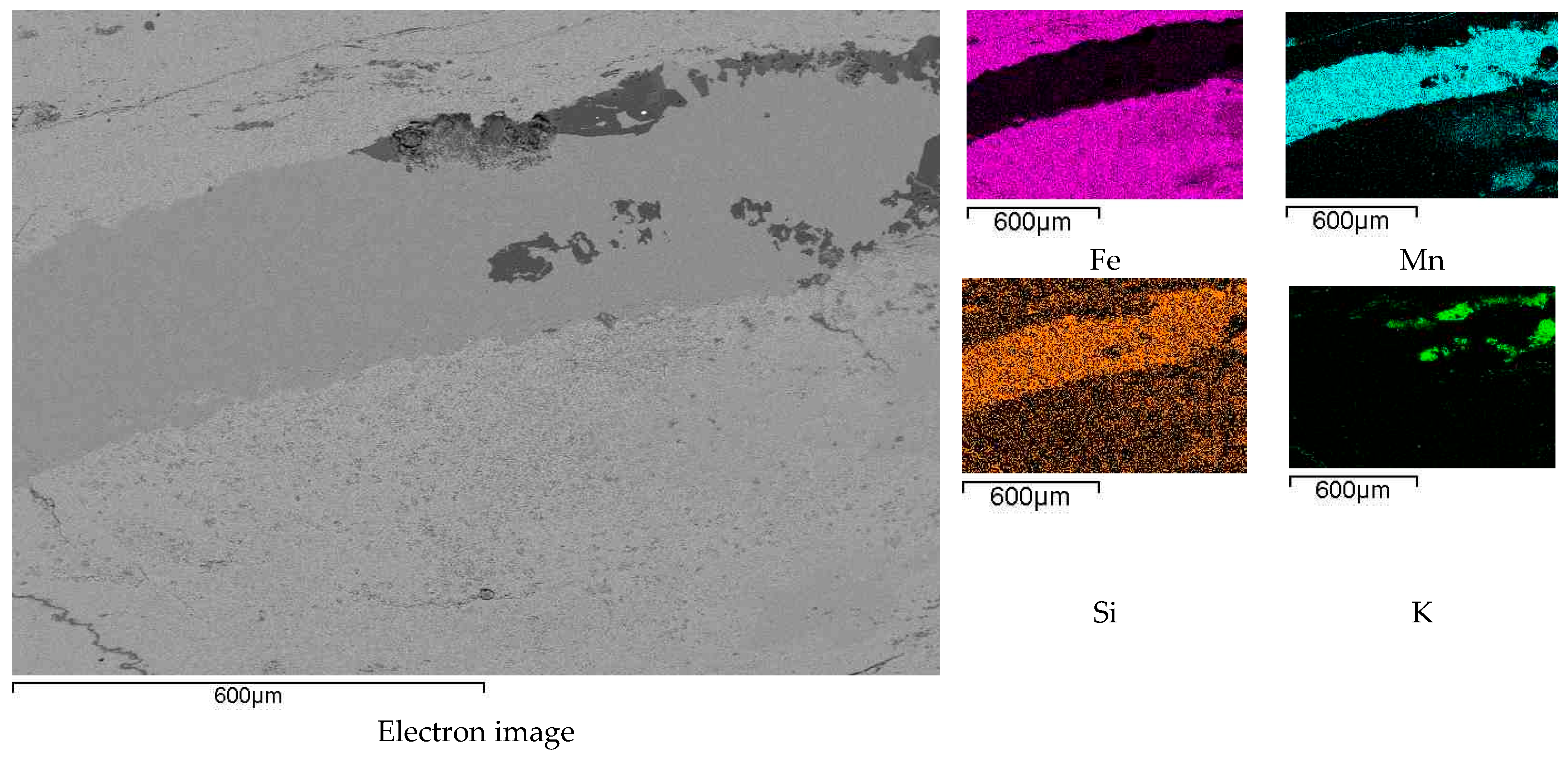

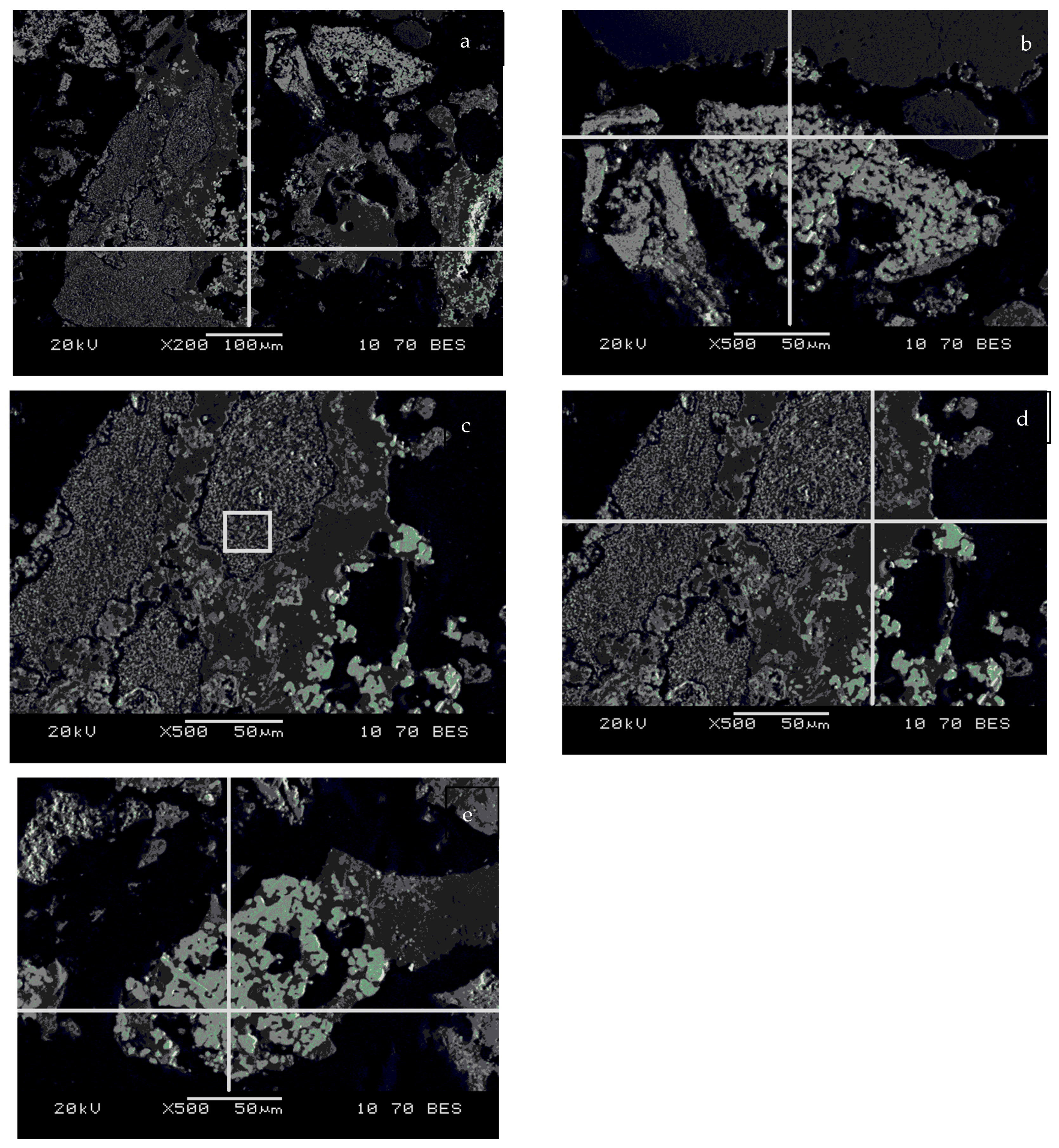

3.1. Results of the Elemental Distribution in the Original Ore

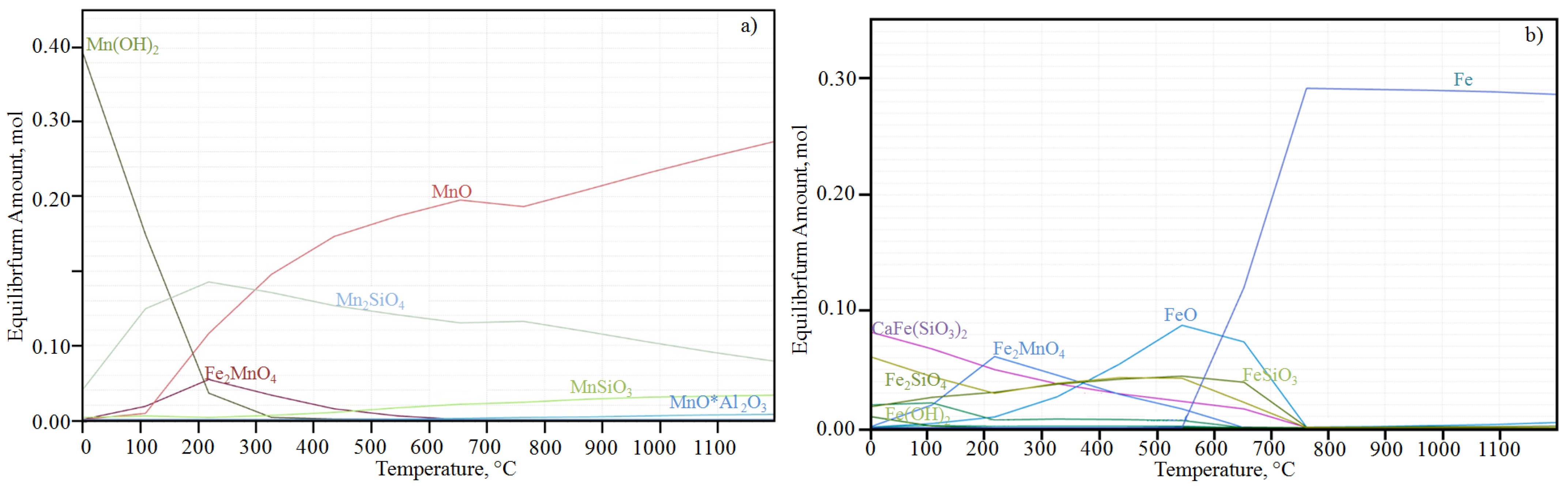

3.2. Thermodynamic Calculation Results

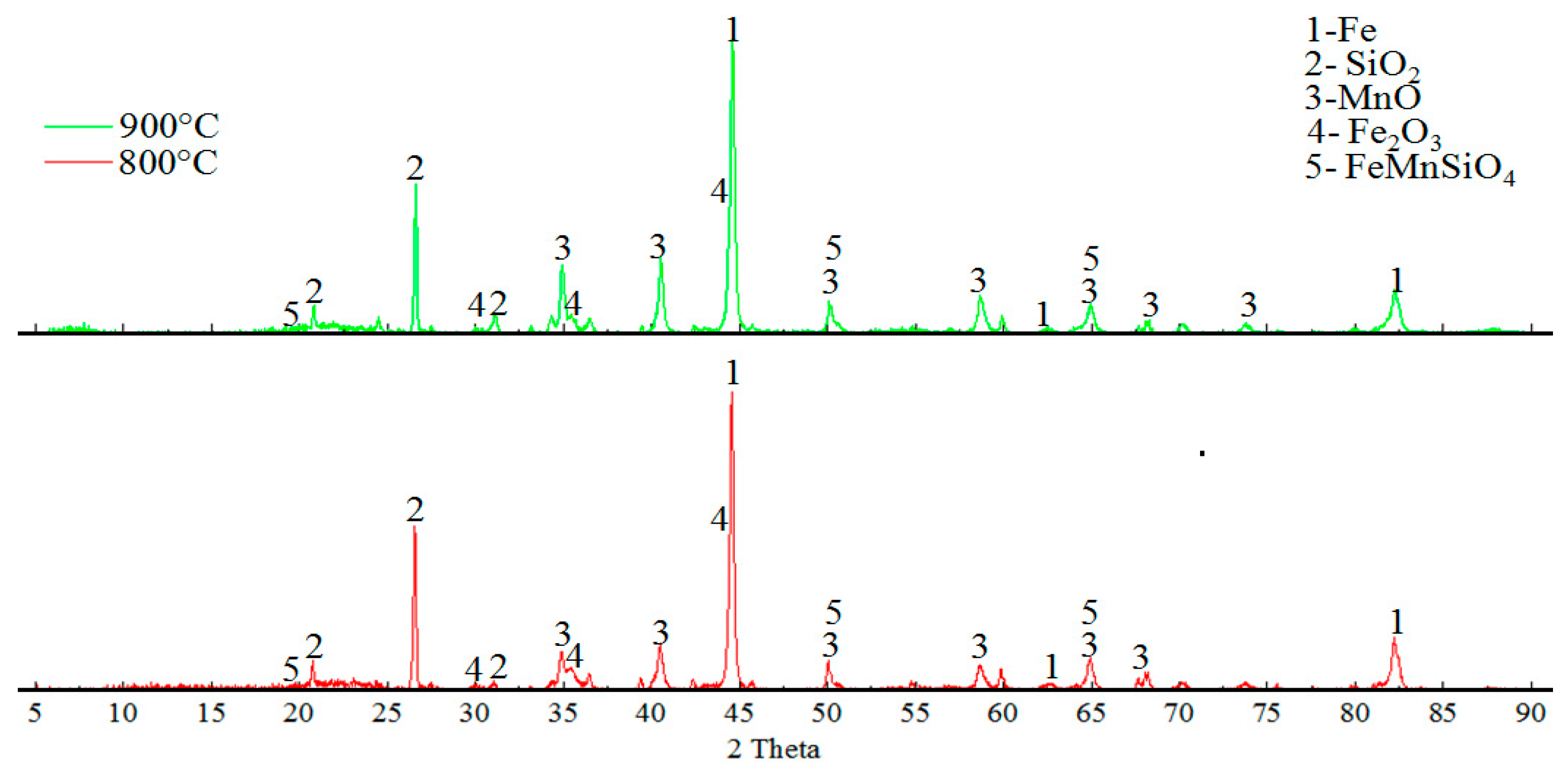

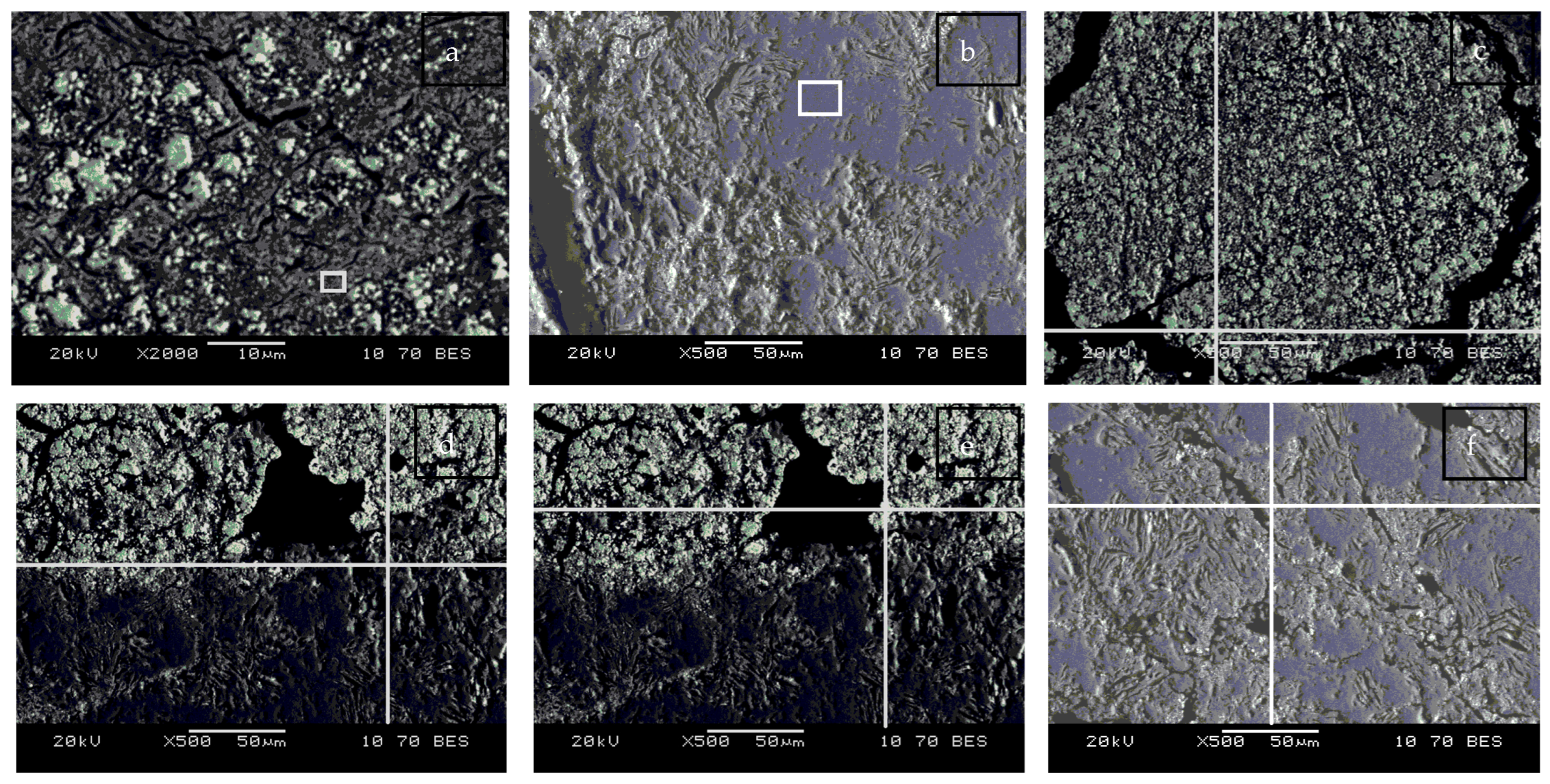

3.3. Results of Reduction Roasting in a Hydrogen Atmosphere

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baisanov, A.; Maishina, Z.; Isagulov, A.; Smagulova, N.; Yudakova, V. Experimental melting of high-silicon ferromanganese with the use of ferromanganesian ore and manganese slag. Metalurgija 2021, 60, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tastanova, A.Y.; Kuldeyev, Y.I.; Temirova, S.S.; Abdykirova, G.Z.; Biryukova, A.A. Processing of low-grade manganese-containing raw materials with pellet production for the manufacture of ferromanganese alloys. Eng. J. Satbayev Univ. 2023, 145, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhrina, O.I.; Rozhikhina, I.D.; Edil’baev, A.I.; Edil’baev, B.A. Manganese ores of the Kemerovo Region–Kuzbass and methods of their beneficiation. Izvestiya. Ferr. Metall. 2020, 63, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybenko, I.A.; Rozhikhina, I.D.; Nokhrina, O.I.; Golodova, M.A. Rational application of high quality manganese concentrate. Izvestiya. Ferr. Metall. 2024, 67, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhrina, O.I.; Rozhikhina, I.D.; Golodova, M.A. Production of high-quality concentrates by hydrometallurgical beneficiation of manganese ores. Mech. Eng. Online Sci. J. 2023, 10, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rybenko, I.A.; Nokhrina, O.I.; Rozhikhina, I.D.; Golodova, M.A. Thermodynamic modeling of cobalt and nickel reduction using hydrometallurgical concentrates for steel alloying. Izvestiya. Ferr. Metall. 2024, 67, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, S.; Wang, X. New progress in the development and utilization of ferromanganese ore. Miner. Eng. 2024, 216, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y.Z.; Gao, P.; Li, Y.J. Present situation of global manganese ore resources and progress of beneficiation technology. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 2023, 43, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Reddy, K.V.K.; Tripathy, S.K.; Kumari, P.; Dubey, A.K.; Mohanty, R.; Satpathy, R.R.; Mukherjee, S. A sustainable reduction roasting technology to upgrade the ferruginous manganese ores. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.K.; Mallick, M.; Singh, V.; Murthy, Y.R. Preliminary studies on teeter bed separator for separation of manganese fines. Powder Technol. 2013, 239, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.K.; Nathsarma, K.C.; Das, S.C.; Misra, V.N. Leaching of low-grade Joda manganese ore with sulphur dioxide in aqueous medium. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. 2023, 112, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hazek, M.N.; Lasheen, T.A.; Helal, A.S. Reductive leaching of manganese from low grade Sinai ore in HCl using H2O2 as reductant. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 84, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, R.N.; Naik, P.K.; Das, S.C. Leaching of manganese from low-grade manganese ore using oxalic acid as reductant in sulphuric acid solution. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 62, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A.; Ali, A.E.; Ibrahim, A.I.; Ahmed, M.S. A comparative study on acid leaching of low-grade manganese ore using some industrial wastes as reductants. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2004, 82, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Chakraborty, T.; Tripathy, S.K. A review of low-grade manganese ore upgradation processes. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2020, 41, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.K.; Ghosh, Y.; Ramamurthy, V.; Tathavadkar, V. Beneficiation and agglomeration process to utilize low–grade ferruginous manganese ore fines. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 99, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononov, R.; Ostrovski, O.; Ganguly, S. Carbothermal solid state reduction of manganese ores: 1. Manganese ore characterization. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuratov, Y.; Baisanov, A.; Tolymbekov, M. Complex processing of iron–manganese ore of Central Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Ferroalloys Congress, Helsinki, Finland, 6–9 June 2010; pp. 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Samuratov, E.K.; Baysanov, A.; Tolymbekov, M. Development of efficient technological processes for processing ferromanganese ores. Proc. Univ. 2007, 4, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Zhou, W.; Han, Y.; Li, Y. Separation of manganese and iron for low-grade ferromanganese ore via fluidization magnetization roasting and magnetic separation technology. Miner. Eng. 2020, 152, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Feng, C.; Ge, Y.; Chu, M. A study on separation of Mn and Fe from high-alumina ferruginous manganese ores by the carbothermal roasting reduction process. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.B.; Zhang, Y.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Su, Z.J.; Li, G.H.; Jiang, T. New understanding on separation of Mn and Fe from ferruginous manganese ores by the magnetic reduction roasting process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 444, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoy, D.; Sukhomlinov, D.; Tangstad, M. Pre-reduction behaviour of manganese ores in H2 and CO containing gases. ISIJ Int. 2020, 60, 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.S.; Tangstad, M.; Du Preez, S.P. Pre-reduction of Nchwaning manganese ore in CO/CO2, H2/H2O, and H2 atmospheres. Miner. Eng. 2024, 216, 108854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri Seftejani, M.; Schenk, J. Thermodynamic of liquid iron ore reduction by hydrogen thermal plasma. Metals 2018, 8, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, D.; Schenk, J. Reduction of iron oxides with hydrogen—A review. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilov, G.; Suleimen, B.; Kosdauletov, N. Challenges and Opportunities in the Recycling of Copper Slags. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, K.I.; Salikhov, S.P.; Roshchin, V.E. Solid-phase reduction of iron from suroyam titanomagnetite ore during metallization in rotary kiln. Mater. Sci. Forum 2019, 946, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, K.I.; Gamov, P.A.; Samolin, V.S.; Roshchin, V.E. Selective reduction of iron from ilmenite concentrate. Chernye Met. 2024, 7, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.H.S.; Hayes, P.C. Microstructural features produced by the reduction of wustite in H2/H2O gas mixtures. Metall. Trans. B 1982, 13, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, S.P.; Cho, T.R.; Hayes, P.C. Mechanisms of porous iron growth on wustite and magnetite during gaseous reduction. Metall. Trans. B 1990, 21, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, S.P.; Hayes, P.C. Microstructural changes occurring during the gaseous reduction of magnetite. Metall. Trans. B 1990, 21, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, S.P.; Hayes, P.C. In situ observations of the gaseous reduction of magnetite. Metall. Trans. B 1990, 21, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farren, M.; Matthew, S.P.; Hayes, P.C. Reduction of solid wustite in H2/H2O/CO/CO2 gas mixtures. Metall. Trans. B 1990, 21, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimen, B. Selective Reduction of Iron in High-Phosphorus Oolitic Ore from the Lisakovsk Deposit. Materials 2024, 17, 5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosdauletov, N.; Nurumgaliyev, A.; Zhautikov, B.; Suleimen, B.; Adilov, G.; Kelamanov, B.; Smirnov, K.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Kuatbay, Y.; Bulekova, G.; et al. Selective Reduction of Iron from Iron–Manganese Ore of the Keregetas Deposit Using Hydrogen. Metals 2025, 15, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimen, B.; Yerzhanov, A.; Kosdauletov, N.; Adilov, G.; Nurumgaliyev, A.; Pushanova, A.; Kelamanov, B.; Gamov, P.; Smirnov, K.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; et al. Behavior of Phosphorus During Selective Reduction of Iron from Oolitic Ore and Separation of Reduction Products. Materials 2025, 18, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshchin, V.E.; Roshchin, A.V. Electrochemistry of reduction processes and prospects for the development of reduction technologies. Izvestiya. Ferr. Metall. 2025, 68, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Schanche, T.L.; Safarian, J. Isothermal Pre-Reduction Behavior of Nchwaning Manganese Ore in H2 Atmosphere. Mater. Proc. 2023, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanche, T.L.; Tangstad, M. Prereduction of Nchwaning Ore in CO/CO2/H2 Gas Mixtures. Minerals 2021, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 3022-80; Metals. Methods for Determination of Density. Izdatelstvo Standartov: Moscow, Russia, 1980.

- GOST 10157–2016; Fireclay Refractories. Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- Bajpai, A.; Ratzker, B.; Shankar, S.; Raabe, D.; Ma, Y. Sustainable Pre-reduction of Ferromanganese Oxides with Hydrogen: Heating Rate-Dependent Reduction Pathways and Microstructure Evolution. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.10451. [Google Scholar]

- Khama, M.I.; Reynolds, Q.G.; Xakalashe, B.S. A Macro-Scale Approach to Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling of the Reduction of Manganese Ore by Hydrogen. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2025, 125, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Schanche, T.L.; Wallin, M.; Safarian, J. Evaluating the Reaction Kinetics on the H2 Reduction of a Manganese Ore at Elevated Temperatures. J. Sustain. Metall. 2024, 10, 2085–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, K.I.; Gamov, P.A.; Roshchin, V.E.; Samolin, V.S. Thermodynamic analysis of conditions for iron and titanium separation in ilmenite concentrate by selective reduction of elements. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metall. 2025, 68, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

| Spectrum, at % | O | Na | Al | Si | K | Mn | Fe | As |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrum (a) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.7 | 95.5 | 1.8 |

| Spectrum (b) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 96.7 | 3.3 |

| Square (c) | 46.4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.5 | 0.00 | 42.3 | 8.8 | 0.00 |

| Spectrum (d) | 41.4 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 34.9 | 6.2 | 11.6 | 1.1 | 0.00 |

| Spectrum (e) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 97.3 | 1.7 |

| Spectrum, at % | O | Mg | Al | Si | K | Ca | Mn | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square (a) | 34.01 | 0.00 | 11.48 | 12.61 | 1.10 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 39.36 |

| Square (b) | 57.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| Spectrum (c) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Spectrum (d) | 52.42 | 2.57 | 8.65 | 22.87 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.39 | 11.41 |

| Spectrum (e) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 99.58 |

| Spectrum (f) | 53.73 | 1.29 | 9.81 | 26.33 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosdauletov, N.; Suleimen, B.; Adilov, G.; Nurumgaliyev, A.; Kelamanov, B.; Kuatbay, Y.; Zhunuskaliyev, T.; Bulekova, G.; Salikhov, S.; Abdirashit, A. Thermodynamic and Experimental Analysis of the Selective Reduction of Iron by Hydrogen from the Kergetas Iron–Manganese Ore. Metals 2025, 15, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121330

Kosdauletov N, Suleimen B, Adilov G, Nurumgaliyev A, Kelamanov B, Kuatbay Y, Zhunuskaliyev T, Bulekova G, Salikhov S, Abdirashit A. Thermodynamic and Experimental Analysis of the Selective Reduction of Iron by Hydrogen from the Kergetas Iron–Manganese Ore. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121330

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosdauletov, Nurlybai, Bakyt Suleimen, Galymzhan Adilov, Assylbek Nurumgaliyev, Bauyrzhan Kelamanov, Yerbol Kuatbay, Talgat Zhunuskaliyev, Gulzat Bulekova, Semen Salikhov, and Assylbek Abdirashit. 2025. "Thermodynamic and Experimental Analysis of the Selective Reduction of Iron by Hydrogen from the Kergetas Iron–Manganese Ore" Metals 15, no. 12: 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121330

APA StyleKosdauletov, N., Suleimen, B., Adilov, G., Nurumgaliyev, A., Kelamanov, B., Kuatbay, Y., Zhunuskaliyev, T., Bulekova, G., Salikhov, S., & Abdirashit, A. (2025). Thermodynamic and Experimental Analysis of the Selective Reduction of Iron by Hydrogen from the Kergetas Iron–Manganese Ore. Metals, 15(12), 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121330