Diffusion of Mg/Al Interface Under Heat Treatment After Being Manufactured by Magnetic Pulse Welding

Abstract

1. Introduction

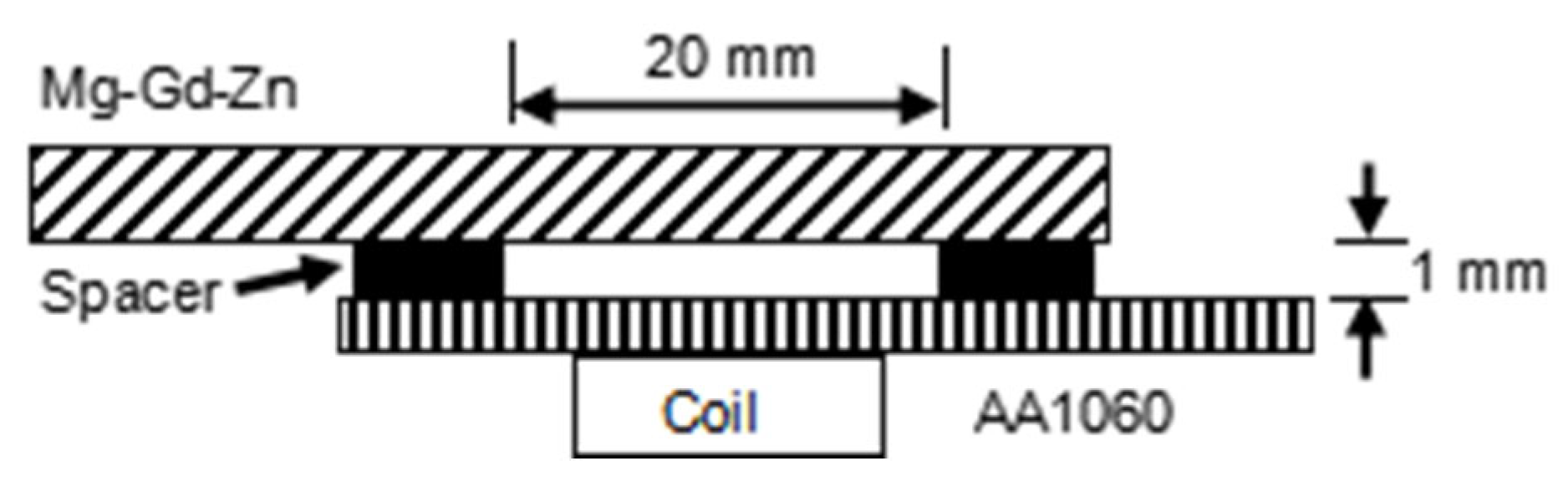

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

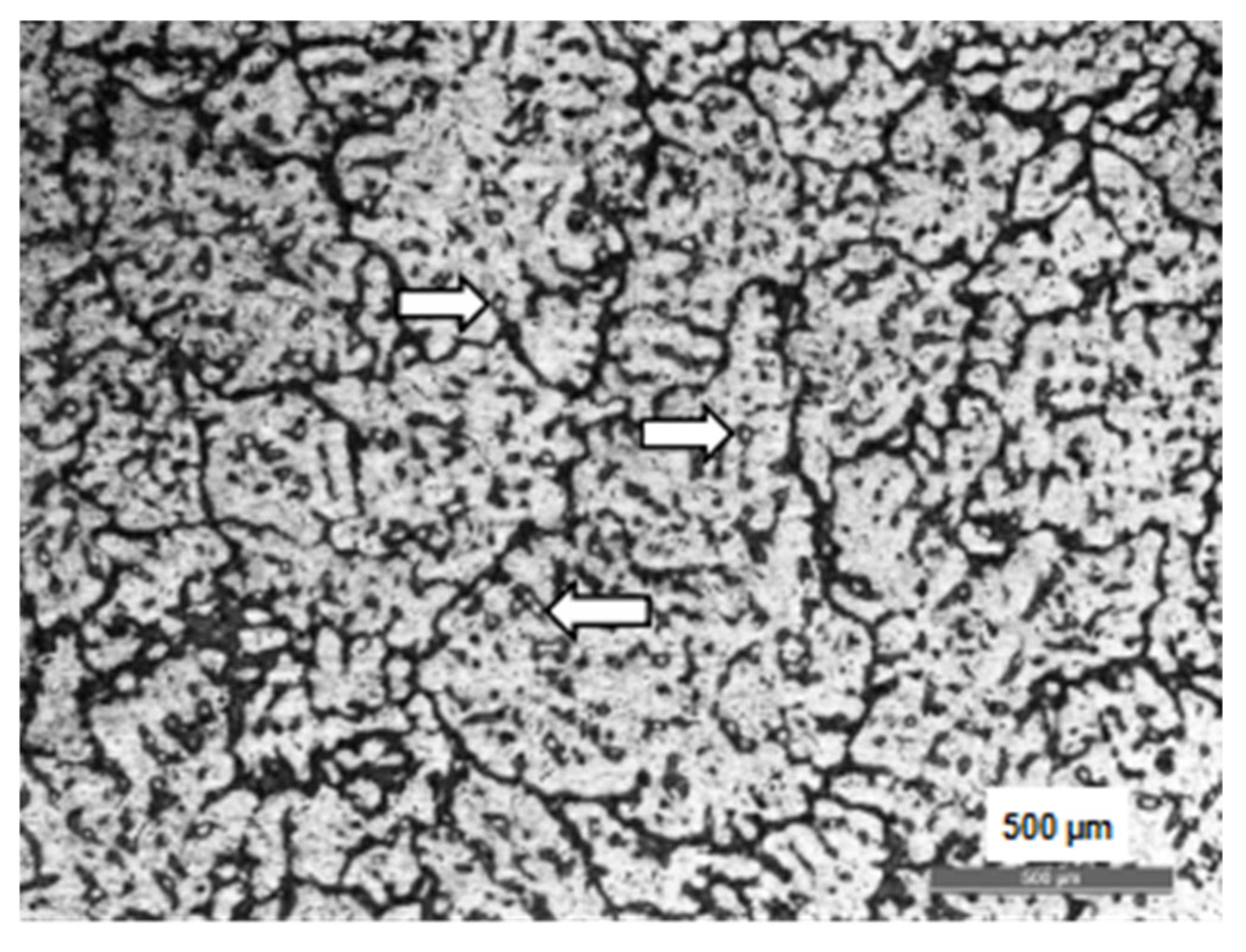

3.1. The As-Cast Magnesium Alloy

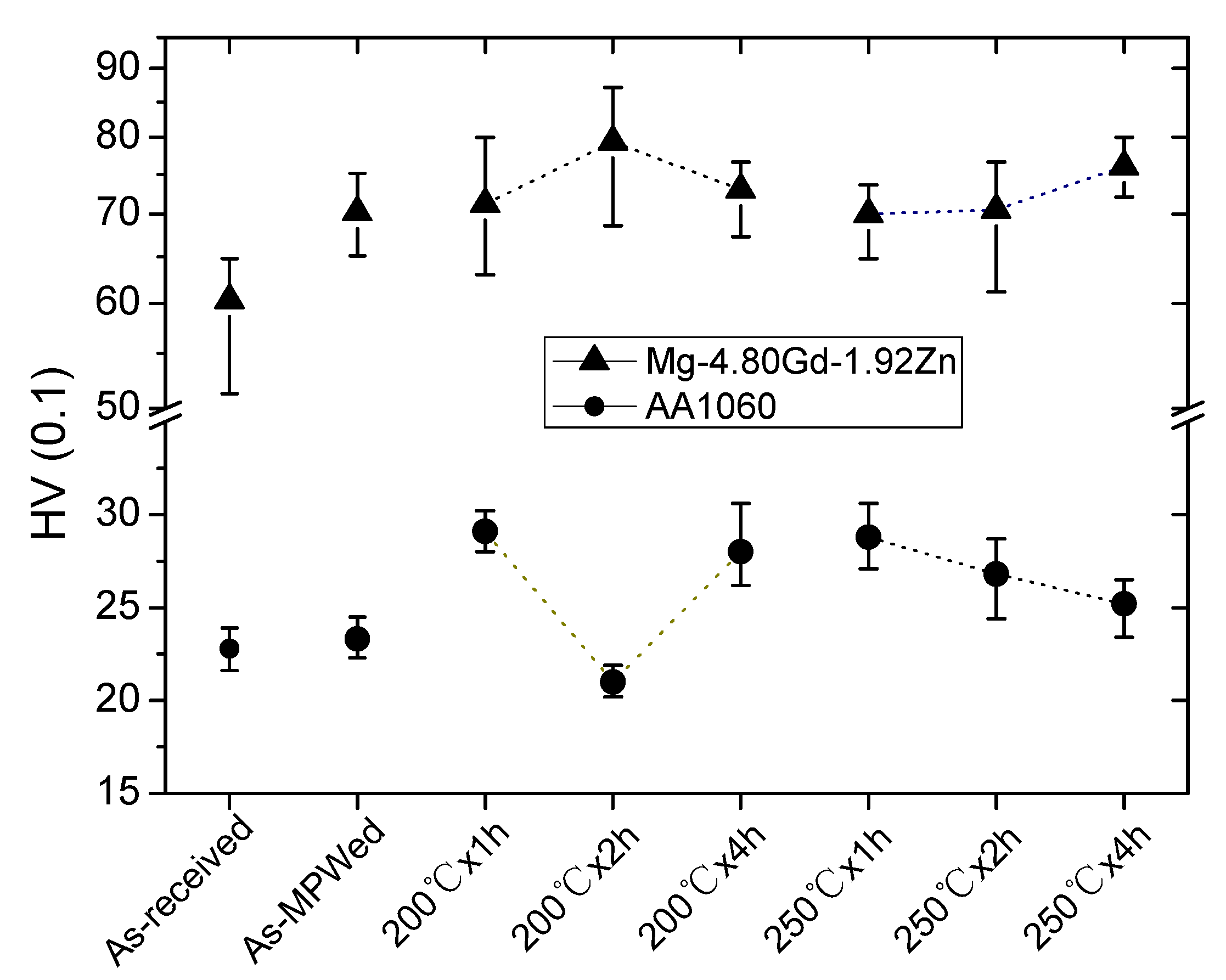

3.2. Hardness

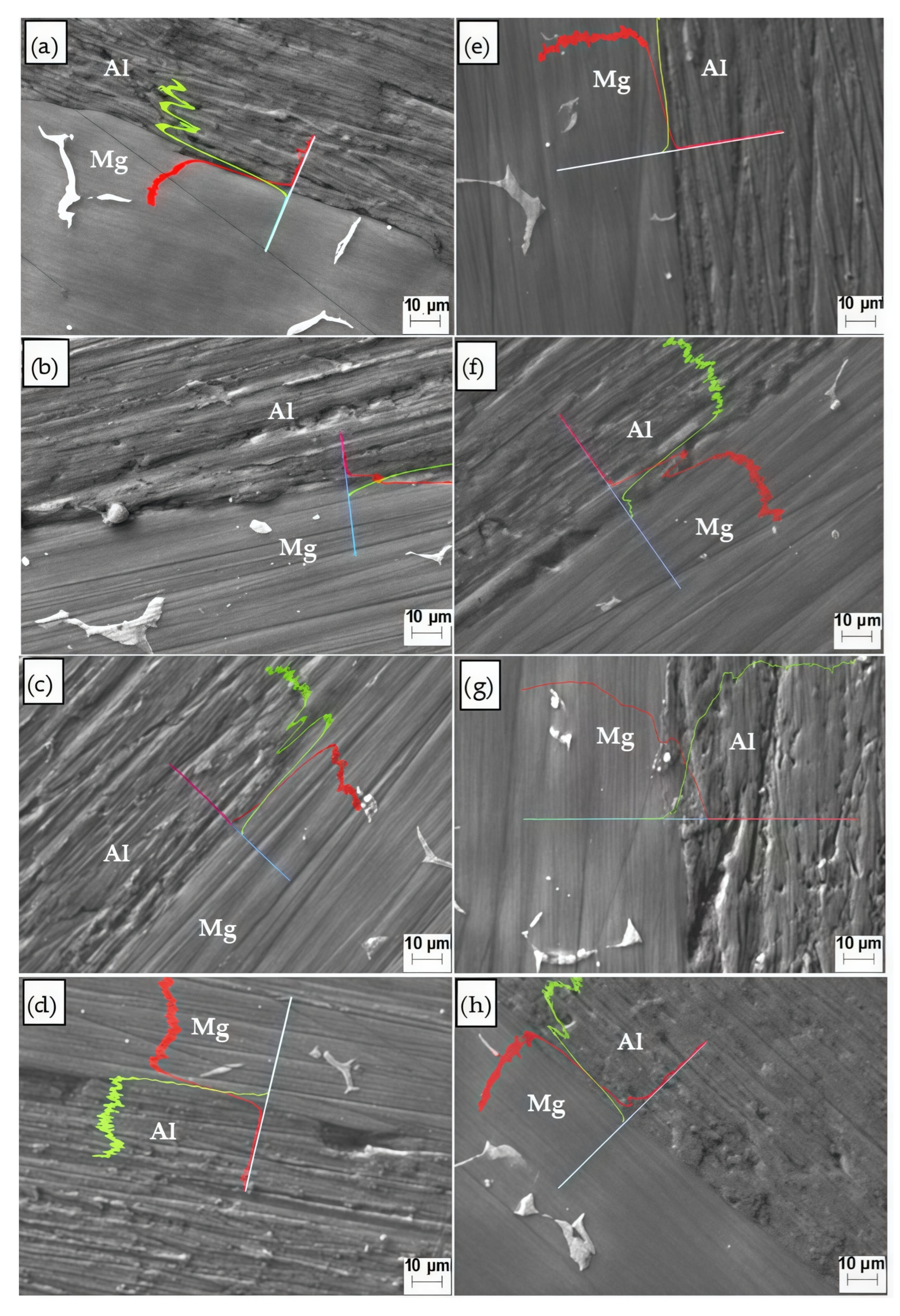

3.3. SEM Results

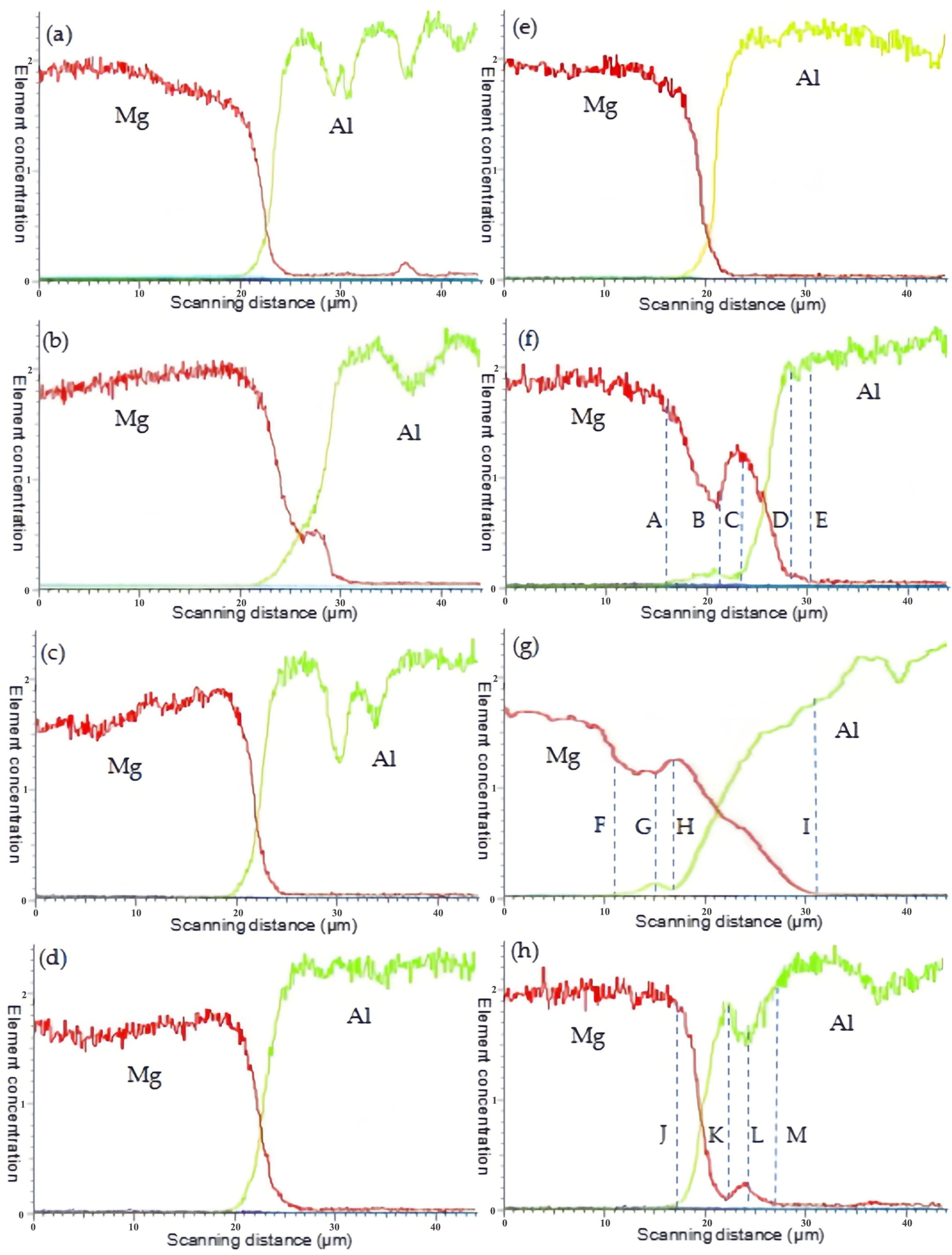

3.3.1. Mg and Al Sides of Mg/Al Interface

3.3.2. Mg/Al Interfaces

4. Discussion

4.1. AA1060 Aluminum Alloy

4.2. Elements in Mg-Gd-Zn Alloy

4.3. Diffusion in Mg/Al Interface

4.3.1. Diffusion of Mg and Al Elements

4.3.2. Diffusion at 250 °C

4.3.3. Hindrance of the Diffusion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, H.; Zhao, H.; Guo., X.; Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Song, J.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F. Recent progress on cast magnesium alloy and components. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 9969–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Tsuruyama, H.; Hino, R.; Aoki, Y.; Morisada, Y.; Fujii, H.; Lee, S.-J. Dissimilar linear friction welding of AZ31 magnesium alloy and AA5052-H34 aluminum alloy. Materialia 2024, 6, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, J.; Dong, Q.; Lv, H.; Wang, F.; Tang, A.; Eckert, J.; Pan, F. Enhancing the room-temperature plasticity of magnesium alloys: Mechanisms and strategies. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 4741–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakhov, A.; Saikov, I.; Denisov, I.; Berdychenko, A.; Ivanov, S.; Niyozbekov, N.; Mironov, S.; Kaibyshev, R.; Dolzhenko, P. Study of microstructure evolution in the aluminum—magnesium alloy AlMg6 after explosive welding and heat treatment. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 4451–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Peng, J.; Wen, C.; Peng, X. Research on the microstructure and properties of a multi-pass friction stir processed 6061A1 coating for AZ31 Mg alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Das, A.; Ballav, R.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, K.K. Enhancing the tensile performance of Mg/Al alloy dissimilar friction stir welded joints by reducing brittle intermetallic compounds. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 115, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, M.; Puri, A.B. Formation of intermetallic compounds (IMCs) in FSW of aluminum and magnesium alloys (Mg/Al alloys)—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 33, 105017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, J.; Yan, K.; Liang, H.; Song, S. Microstructure characterization and mechanical properties of Mg/Al dissimilar joints by friction stir welding with Zn interlayer. Phys. Metals Metall. 2020, 121, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Saravanan, S.; Barma, J.D. Effect of explosive loading ratio on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al 5052/AZ31B explosive weld composite. JOM 2023, 75, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhao, H. Effect of interlayer on interface microstructure and properties of Mg/Al friction stir welded joints. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2025, 46, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahzadeh, A.; Vanani, B.B.; Koohdar, H.; Jafarian, H.R. Influence of variation ambient system on dissimilar friction stir welding of Al alloy to Mg alloy by the addition of nanoparticles and interlayer. Met. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 2830–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ke, L.; Nie, H.; Xia, C.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S. Precipitation behavior of intermetallic compounds at the interface of thick plate friction stir welded Al alloy/Mg alloy joints under local strong cooling. Acta Metall. Sin. 2024, 60, 777–788. [Google Scholar]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Banjare, P.N.; Tripathi, M.K.; Manoj, M.K. Effect of vertical and horizontal zinc interlayer on material flow, microstructure, and mechanical properties of dissimilar FSW of Al 7075 and Mg AZ31 alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 4453–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zheng, Z.; Du, P.; Chang, L. A double molten pool laser welding process for joining magnesium alloys and aluminum alloys: The process, microstructure and mechanical properties of joints. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 35, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liao, R.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L. Investigations of the properties of Mg–5Al–0.3Mn–xCe (x = 0–3, wt.%) alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 477, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, B.; Cai, Q.; Wang, L. Effect of mischmetal and yttrium on microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg-Al alloy. T. Nonferr. Metal. Soc. (Eng. Ed.) 2003, 13, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Nakata, K.; Liao, J. Microstructural modification and mechanical property improvement in friction stir zone of thixo-molded AE42 Mg alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Leng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Meng, J.; Wu, R. Effect of Ce on microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of high-pressure die-cast Mg–4Al–based alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, S.; Feng, G.; Huisheng, C.; Liang, L. Structural analysis of Al–Ce compound phase in AZ–Ce cast magnesium alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 6301–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, M. Effects of Ce on Microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Li-Al Alloy. Spec. Cast. Nonfer. Alloys 2007, 5, 329–331. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Fan, R.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Fu, Y.; Pu, Z. Using multiscale second phases to fabricate high-performance Mg–3Al–3Nd–0.1Mn alloys with bimodal grain structures. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Kang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Effect of Pr addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ61 magnesium alloy. China Foundry (Eng. Ed.) 2014, 11, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.U.; Lee, G.M.; Park, S.H. Bending properties of extruded AZ91–0.9Ca–0.6Y alloy and their improvement through precompression and annealing. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 2238–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbahari, B.; Emamy, M.; Mirzadeh, H. Synergistic effect of Al and Gd on enhancement of mechanical properties of magnesium alloys. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2017, 27, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Qin, S.; Qin, Z.; Lei, C. Effects of Gd/Nd ratio on the microstructures and tensile creep behavior of Mg–8Al–Gd–Nd alloys crept at 423K. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2522–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Zha, M.; Jia, H.-L.; Tian, T.; Zhang, X.-H.; Wang, C.; Ma, P.-K.; Gao, D.; Wang, H.-Y. Influences of the Al3Sc particle content on the evolution of bimodal grain structure and mechanical properties of Al–Mg–Sc alloys processed by hard-plate rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 802, 140451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Okagawa, K.; Kashani, M. Application of magnetic pulse welding technique for flexible printed circuit boards (FPCB) lap joints. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2013, 213, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, X. Microstructure evolution during magnetic pulse welding of dissimilar aluminium and magnesium alloys. J. Manuf. Process. 2015, 19, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Yin, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Feng, W. Research progress of electromagnetic pulse welding technology: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.-Y.; Kang, B.-Y.; Yun, T.-J.; Lee, B.-R.; Kim, I.-S. The present situation of the research and development of the electromagnetic pulse technology. Mater. Today-Proc. 2020, 22, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, A.; Sharma, A. Magnetic pulse welding: An efficient and environmentally friendly multi-material joining technique. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 100, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jing, L.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Cui, J.; Tang, X.; Jiang, H. Mechanical properties and joining mechanisms of Al-Fe magnetic pulse welding by spot form for automotive application. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 76, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, T.; Li, G.; Cui, J. Mechanical properties and interfacial microstructures of magnetic pulse welding joints with aluminum to zinc-coated steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 788, 139425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Sun, L.; Li, G.; Cui, J.; Huang, L.; Xu, Z. Fatigue fracture properties of magnetic pulse welded dissimilar Al-Fe lap joints. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 121, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, Z.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C. Mechanical property and microstructure of aluminum alloy-steel tubes joint by magnetic pulse welding. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 561, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-P.; Xu, Z.-D.; Jiang, H.-W.; Zhao, Z.-X.; Li, C.-F. Magnetic pulse joining of aluminum alloy–carbon steel tubes. T. Nonferr. Metal. Soc. 2012, 22, s548–s552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Arora, K.S.; Shome, M.; Bysakh, S. Interface characteristics and performance of magnetic pulse welded copper-Steel tubes. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 245, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoelison, R.N.; Racine, D.; Zhang, Z.; Buiron, N.; Marceau, D.; Rachik, M. Magnetic pulse welding: Interface of Al/Cu joint and investigation of intermetallic formation effect on the weld features. J. Manuf. Process. 2014, 16, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Sapanathan, T.; Raoelison, R.N.; Hou, Y.L.; Simar, A.; Rachik, M. On the complete interface development of Al/Cu magnetic pulse welding via experimental characterizations and multiphysics numerical simulations. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 296, 117185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xu, S.; Gao, W.; Meng, Y.; Lin, S.; Dai, L. Microstructure characteristics and mechanical properties of Mg/Al joints manufactured by magnetic pulse welding. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoelison, R.N.; Sapanathan, T.; Li, J.S.; Zhang, Z.; Racine, D.; Chen, X.-G.; Marceau, D.; Rachik, M. Transformation sequence of Mg-Si precipitates towards a precipitation of Mn and Cr containing phase governed by the high strain-rate collision during magnetic pulse welding of Al-Mg-Si alloy. J. Alloys Metall. Systems 2023, 4, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yin, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S. Interfacial microstructure and mechanical properties of the Al/Ti joint by magnetic pulse welding. Mater. Charact. 2022, 194, 112462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H. Simulation and experimental analysis of Al/Ti plate magnetic pulse welding based on multi-seams coil. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 83, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Cui, J.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, H. A sandwich structure realizing the connection of CFRP and Al sheets using magnetic pulse welding. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295, 115865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, A.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, G.; Cui, J. Fatigue behavior of Al-CFRP spot-welded joints prepared by electromagnetic pulse welding. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 174, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, L. Research status of Mg/Al dissimilar alloys welding. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 66, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Cui, J. Study on Process and Mechanical Properties of Mg/Al dissimilar metal sheet joints by magnetic pulse welding. J. Netshape Form. Eng. 2021, 13, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Pan, F. Enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding in ZK60 magnesium alloy by ageing precipitation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2013, 74, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.K.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.B.; Han, E.H. The effect of precipitates on the mechanical properties of ZK60-Y alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 420, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tong, Y.; Kaneda, J. Effects of heattreatments on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-15Gd-5Y-0.5Zr alloy. J. Rare Earth. 2008, 26, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Peng, M.; Duan, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Bu, H.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, M. Molecular dynamics simulation of diffusion mechanisms of Al–Mg interface. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 715, 17620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L. Electrolytic deposition and diffusion of lithium onto magnesium-9 wt pct yttrium bulk alloy in low-temperature molten salt of lithium chloride and potassium chloride. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2009, 40, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Fe | Si | Zn | Mn | Cu | Gd | Al | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA1060 | 0.18 | 0.051 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | —— | Bal. | —— |

| Mg | —— | —— | 1.92 | —— | —— | 4.80 | —— | Bal. |

| (a) | (b) | (c) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | 79.96 at.% | 98.95 at.% | 90.38 at.% |

| Gd | 12.59 at.% | 1.05 at.% | 7.52 at.% |

| Zn | 7.45 at.% | —— | 2.10 at.% |

| Total | 100 at.% | 100 at.% | 100 at.% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, H.; Ye, X.; Liu, K. Diffusion of Mg/Al Interface Under Heat Treatment After Being Manufactured by Magnetic Pulse Welding. Metals 2025, 15, 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121331

Dong H, Ye X, Liu K. Diffusion of Mg/Al Interface Under Heat Treatment After Being Manufactured by Magnetic Pulse Welding. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121331

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Hanwu, Xiaozhou Ye, and Ke Liu. 2025. "Diffusion of Mg/Al Interface Under Heat Treatment After Being Manufactured by Magnetic Pulse Welding" Metals 15, no. 12: 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121331

APA StyleDong, H., Ye, X., & Liu, K. (2025). Diffusion of Mg/Al Interface Under Heat Treatment After Being Manufactured by Magnetic Pulse Welding. Metals, 15(12), 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121331