Evaluation of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-0.5Mg Alloy Modified with Ca/P and TCB Complex

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructures of AC and AP Samples

3.2. Tensile Properties of AC and AP Samples

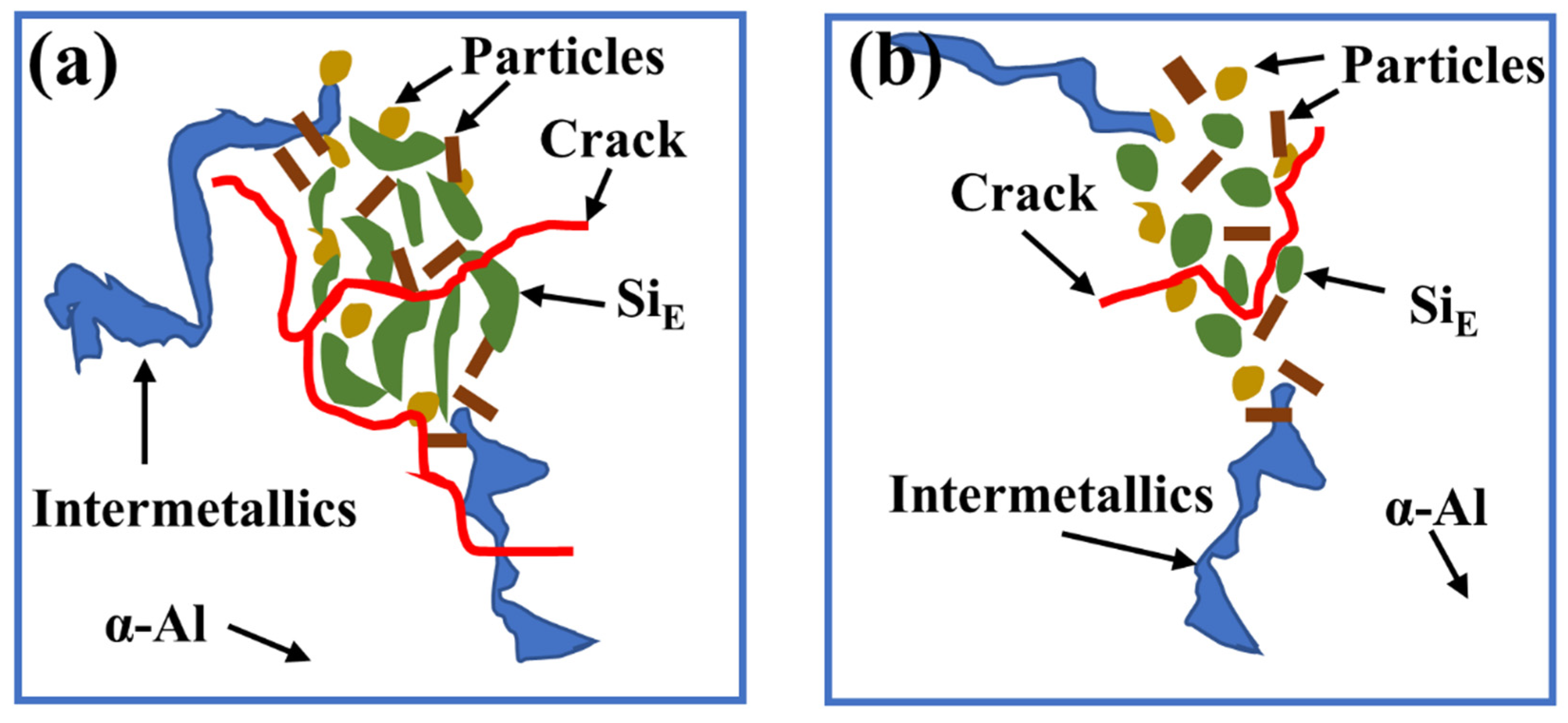

3.3. Fracture Morphology of AC and AP Samples

3.4. Microstructure and Tensile Properties of ATCB Alloy Samples

3.5. Strengthening Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Eutectic Si particles in the AC sample had a fibrous structure, whereas the AP sample contained elongated eutectic Si particles. The AC sample exhibited higher elongation because of its better plasticity under the effect of fibrous eutectic Si particles; thus, it had a higher QI value at 350 °C. Ca modification is a potential method for enhancing the matching degree of strength and plastic at high temperature for Al-Si-Cu-Ni-Mg piston alloys.

- (2)

- The micron and submicron C-TiB2 and Al4C3 particles formed by the in situ reaction of TCB particles acted as bridging phases within the second-phase network structure. During high-temperature deformation, these particles improved the stability of the second-phase network structure, causing a significant strength improvement in the alloy. The ultimate tensile strength at 350 °C increased from 74 MPa for the AC-ZC sample to 101 MPa for the ATCB-ZC sample, representing a 36.5% enhancement.

- (3)

- The T6-treated samples displayed higher FR than the ZC-treated samples due to the disruption of the second-phase network structure and the Ostwald ripening of nanoscale precipitates. The comprehensive analysis revealed that Orowan strengthening was the dominant strengthening mechanism at room temperature, whereas load transfer and network structure strengthening were the key strengthening mechanisms at high temperatures.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niu, G.D.; Mao, J.; Wang, J. Effect of Ce Addition on Fluidity of Casting Aluminum Alloy A356. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2019, 50, 5935–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pang, J.C.; Liu, H.Q.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, M.X.; Zhang, Z.F. Effect of constraint factor on the thermo-mechanical fatigue behavior of an Al-Si eutectic alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 783, 139279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.J.; Feng, B.; Ye, J.; Bao, Q.H.; Kong, X.Y.; Jiang, H.Y.; Ding, W.J. Phases Formation and Evolution at Elevated Temperatures of Al-12Si-38Cu-2Ni-1Mg Alloy. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2017, 19, 1600623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Sandoval, J.; Garza-Elizondo, G.H.; Samuel, A.M.; Valtiierra, S.; Samuel, F.H. The ambient and high temperature deformation behavior of Al-Si-Cu-Mg alloy with minor Ti, Zr, Ni additions. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.G.; Lee, J.M.; Cho, Y.H.; Yoon, W.H. Combined effects of ultrasonic melt treatment, Si addition and solution treatment on the microstructure and tensile properties of multicomponent Al-Si alloys. J. Alloy Compd. 2017, 693, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.Q.; Gao, T.; Liu, G.L.; Sun, Q.Q.; Han, M.X.; Xu, Q.F.; Liu, X.F. Comparative Evaluation of the Mechanical Properties of Al-Si-Cu-Ni-Mg Alloys with Distinct Spatial Architectures at Ambient and High Temperatures. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 31, 1932–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Sasa, Y.; Kobashi, M.; Kato, M.; Segawa, M.; Shimono, Y.; Nomoto, S. Persistent Homology Analysis of the Microstructure of Laser-Powder-Bed-Fused Al–12Si Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.W.; Ha, S.-H.; Siddique, J.A.; Kim, B.-H.; Yoon, Y.-O.; Lim, H.-K.; Kim, S.K. Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of Al–Cu–Mg Alloys with Si Addition. Materials 2023, 16, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xiang, Z.L.; Li, J.H.; Huang, J.C.; Li, L.Z.; Li, M.; Sun, W.C.; Ma, X.Z.; Chen, Z.Y. The influence of Sr on the modification mechanism and mechanical properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-Mg alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebaie, O.; Samuel, A.M.; Samuel, F.H. Effects of Sr-modification, iron-based intermetallics and aging treatment on the impact toughness of 356 Al-Si-Mg alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 3027–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riestra, M.; Ghassemali, E.; Bogdanoff, T.; Seifeddine, S. Interactive effects of grain refinement, eutectic modification and solidification rate on tensile properties of Al-10Si alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 703, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.D.; Chen, X.H.; Wang, Z.D.; Chen, K.X.; Pan, S.W.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.L. Synergistic influence of La and Zr on microstructure and mechanical performance of an Al-Si-Mg alloy at casting state. J. Alloy Compd. 2022, 902, 163829. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, M.R.; Styles, C.M.; Reed, P.A.S. Elevated temperature short crack fatigue behaviour in near eutectic Al-Si alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2003, 25, 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuya, T.O.; Sinclair, I.; Moffat, A.J.; Reed, P.A.S. Micromechanisms of fatigue crack growth in cast aluminium piston alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2012, 42, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.R.; Song, W.; Zhong, G.; Huang, W.Q.; Zuo, Z.X.; Zhao, C.Z.; Yan, K.J. High-cycle fatigue failure analysis of cast Al-Si alloy engine cylinder head. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 127, 105546. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Y.D.; Wang, Q.D.; Wang, G.L.; Liu, T. Effects of Sr content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of cast Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-08Mg alloys. J. Alloy Compd. 2015, 622, 572–579. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.C.; Lu, L.Z.; Li, G.J.; Huang, Y.L.; Yang, L.L.; Guo, H.T.; Wu, F. Influence of minor addition of La and Ce on the ageing precipitation behavior of Sr-modified Al-7Si-06Mg alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108825. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, T.H.; Schaffer, P.L.; Arnberg, L. Influence of Some Trace Elements on Solidification Path and Microstructure of Al-Si Foundry Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. 2013, 44, 3783–3796. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, S.D.; Dahle, A.K.; Taylor, J.A.; StJohn, D.H. Modification-related porosity formation in hypoeutectic aluminum-silicon alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2004, 35, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; Tiryakioglu, M. Review of effect of P and Sr on modification and porosity development in Al-Si alloys. Mater. Sci. Tech-Lond. 2010, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, T.H.; Schaffer, P.L.; Arnberg, L. Influence of Phosphorus on the Nucleation of Eutectic Silicon in Al-Si Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. 2013, 44, 5796–5805. [Google Scholar]

- Rakhmonov, J.; Timelli, G.; Basso, G. Interaction of Ca, P trace elements and Sr modification in AlSi5Cu1Mg alloys. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 133, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Z.; Wang, S.H.; Dong, X.X.; Liu, X.F.; Ji, S.X. Morphologically templated nucleation of primary Si on AlP in hypereutectic Al-Si alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 100, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T.; Kim, H.J.; Niinomi, M. Effect of calcium on mechanical properties of recycled aluminium casting alloys. Mater. Sci. Tech-Lond. 1997, 13, 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.Y.; Liu, C.F.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.P.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, Z.M.; Gao, J.M.; Xiong, S.M. Effect of Ca addition on solidification microstructure of hypoeutectic Al-Si casting alloys. China Foundry 2019, 16, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarif, M.; Spacil, I.; Pabel, T.; Schumacher, P.; Li, J. Effect of Ca and P on the Size and Morphology of Eutectic Mg2Si in High-Purity Al-Mg-Si Alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.J.; Feng, J.; Xu, X.J.; Kong, X.Y.; Jiang, H.Y. Effect of δ-Al3CuNi phase and thermal exposure on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Si-Cu-Ni alloys. J. Alloy Compd. 2019, 791, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pang, J.C.; Liu, H.Q.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, Z.F. Influence of microstructures on the tensile and low-cycle fatigue damage behaviors of cast Al12Si4Cu3NiMg alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 759, 797–803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.X.; Yan, X.R.; Fan, Y.; Liu, G.L.; Nie, J.F.; Liu, X.F.; Liu, S.D. An anti Si/Zr-poisoning strategy of Al grain refinement by the evolving effect of doped complex. Acta Mater. 2023, 249, 118812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Zhi, Y.T.; Zou, W.B.; Nie, J.F.; Fan, Y.; Liu, R.C.; Chen, H.R.; Zhong, G.; Zhou, Y.L.; Li, C.; et al. Achieving significant grain refinement and enhanced mechanical properties of sand-cast ZL114A alloy by s a new synergetic addition strategy of Al-TCB grain refiner and Sr modifier. J. Alloy Compd. 2025, 1018, 179246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.T.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Ren, X.M.; Han, M.X.; Liu, G.L.; Wang, W.Y.; Liu, S.D.; Liu, X.F. A strategy for adjusting the microstructure configuration and high temperature mechanical properties of Al-Cu alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 6422–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 228.2-2015; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 2: Method of Test at Elevated Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Chandrashekharaiah, T.M.; Kori, S.A. Effect of grain refinement and modification on the dry sliding wear behaviour of eutectic Al-Si alloys. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschini, L.; Morri, A.; Morri, A.; Gamberini, A.; Messieri, S. Correlation between ultimate tensile strength and solidification microstructure for the sand cast A357 aluminium alloy. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 4525–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Zhao, Y.T.; Kai, X.Z.; Wang, Y.; Qian, W.; Yang, Y.G.; Wang, M.; Xu, W.T. The effects of Er addition on the microstructure and properties of an in situ nano ZrB2-reinforced A3562 composite. J. Alloy Compd. 2018, 731, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoosi, V.; Abbasi, S.M.; Mirsaed, S.M.G.; Mostafaei, M. Influence of cooling rate on the solidification behavior and microstructure of IN738LC superalloy. J. Alloy Compd. 2016, 680, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, A.; Su, G.; Zhang, J. Effect of Final Thermomechanical Treatment on the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of T Phase Hardened Al-5.8Mg-4.5Zn-0.5Cu Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, D.; Tang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Song, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in a Gd-Modified Extruded Mg-4Al-3.5Ca Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Lu, Y.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, H.P.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Characterization and strengthening effects of different precipitates in Al-7Si-Mg alloy. J. Alloy Compd. 2021, 885, 161028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.K.; Chen, L.Q.; Wolverton, C. First-principles calculations of β”-Mg5Si6/α-Al interfaces. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 5934–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, R.; van Huis, M.A.; Jansen, J.; Zandbergen, H.W.; Marioara, C.D.; Andersen, S.J. The crystal structure of the β′ phase in Al-Mg-Si alloys. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 3815–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Jiang, W.Q.; Liu, C.T.; Zhang, Z.W.; Liaw, P.K. Nanoprecipitate-Strengthened High-Entropy Alloys. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Q.; Pang, J.C.; Wang, M.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, Z.F. Effect of temperature on the mechanical properties of Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Ni-Ce alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 824, 141762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, G.; Peng, L.M.; Fu, P.H.; Yuan, L.Y.; Liu, Y. Role of Mg2Si precipitates size in determining the ductility of A357 cast alloy. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.C.; Zhang, W.Z. Low cycle fatigue and fatigue-creep interaction effects on softening behavior and life prediction of cast aluminum alloy at elevated temperature. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evsevleev, S.; Mishurova, T.; Cabeza, S.; Koos, R.; Sevostianov, I.; Garcés, G.; Requena, G.; Fernández, R.; Bruno, G. The role of intermetallics in stress partitioning and damage evolution of AlSil2CuMgNi alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 736, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.J.; Ye, B.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H.X.; Kong, X.Y.; Jiang, H.Y. Effect of ε-Al3Ni phase on mechanical properties of Al-Si-Cu-Mg-Ni alloys at elevated temperature. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Si | Cu | Mg | Ni | Fe | Ca | P | Ti | B | C | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 11.41 | 3.67 | 0.52 | 1.92 | 0.17 | 0.052 | - | - | - | - | Bal. |

| AP | 11.47 | 3.61 | 0.58 | 1.91 | 0.16 | - | 0.026 | - | - | - | Bal. |

| ATCB | 12.03 | 3.64 | 0.68 | 2.04 | 0.21 | 0.059 | - | 0.404 | 0.031 | 0.039 | Bal. |

| Point | Al | Si | Cu | Ni | Mg | Fe | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.8 | 83.9 | 0.3 | - | - | - | eutectic Si |

| 2 | 24.8 | 32.5 | 9.1 | 0.4 | 33.3 | - | Al5Cu2Mg8Si6 |

| 3 | 58.8 | - | 30.4 | 10.8 | - | - | Al7Cu4Ni |

| 4 | 66.7 | 1.2 | 31.5 | 0.7 | - | - | Al2Cu |

| 5 | 57.7 | - | 23.2 | 18.3 | - | 0.8 | Al3CuNi |

| 6 | 15.8 | 83.9 | 0.3 | - | - | - | eutectic Si |

| 7 | 2.4 | 97.6 | - | - | - | - | primary Si |

| 8 | 58.9 | - | 31.6 | 9.6 | - | - | Al7Cu4Ni |

| 9 | 66.7 | 1.4 | 31.4 | 0.6 | - | - | Al2Cu |

| 10 | 59.0 | - | 20.4 | 20.3 | - | 0.3 | Al3CuNi |

| Temp/°C | Samples | UTS/MPa | YS/MPa | EL/% | FR/% | QI/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | AC-ZC | 293.2 ± 3.1 | 270.5 ± 5.1 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | - | 306 |

| AP-ZC | 327.9 ± 2.3 | 310.0 ± 4.0 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | - | 341.5 | |

| AC-T6 | 353.9 ± 6.2 | 317.5 ± 3.4 | 0.87 ± 0.02 | - | 361 | |

| AP-T6 | 370.3 ± 4.2 | 330.5 ± 3.3 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | - | 368 | |

| 350 | AC-ZC | 74.0 ± 0.5 | 59.2 ± 1.1 | 7.16 ± 0.24 | 74.76 | 417.2 |

| AP-ZC | 75.5 ± 1.5 | 61.3 ± 2.0 | 6.84 ± 0.31 | 76.97 | 403.3 | |

| AC-T6 | 78.0 ± 1.0 | 69.0 ± 1.0 | 8.95 ± 0.22 | 77.96 | 516.5 | |

| AP-T6 | 80.1 ± 1.0 | 71.0 ± 1.0 | 8.31 ± 0.28 | 78.38 | 486.5 |

| Temp/°C | Samples | UTS/MPa | YS/MPa | EL/% | FR/% | QI/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | ATCB-ZC | 257.8 ± 5.8 | 255.4 ± 3.4 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | - | 277.8 |

| ATCB-T6 | 280.9 ± 6.3 | 275.8 ± 2.8 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | - | 301.9 | |

| AC-ZC | 293.2 ± 3.1 | 270.5 ± 5.1 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | - | 306 | |

| 350 | ATCB-ZC | 101 ± 1.0 | 78 ± 2.0 | 3.8 ± 0.11 | 60.82 | 291.0 |

| ATCB-T6 | 91.5 ± 0.5 | 75 ± 1.0 | 4.75 ± 0.25 | 67.42 | 329.0 | |

| AC-ZC | 74.0 ± 0.5 | 59.2 ± 1.1 | 7.16 ± 0.24 | 74.76 | 417.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Ren, X.; Li, X.; Duan, H.; Wang, W.; Han, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, X. Evaluation of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-0.5Mg Alloy Modified with Ca/P and TCB Complex. Metals 2025, 15, 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111276

Sun Y, Ren X, Li X, Duan H, Wang W, Han M, Liu G, Liu S, Liu X. Evaluation of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-0.5Mg Alloy Modified with Ca/P and TCB Complex. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111276

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yuan, Xiaoming Ren, Xueting Li, Hong Duan, Weiyi Wang, Mengxia Han, Guiliang Liu, Sida Liu, and Xiangfa Liu. 2025. "Evaluation of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-0.5Mg Alloy Modified with Ca/P and TCB Complex" Metals 15, no. 11: 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111276

APA StyleSun, Y., Ren, X., Li, X., Duan, H., Wang, W., Han, M., Liu, G., Liu, S., & Liu, X. (2025). Evaluation of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Al-12Si-4Cu-2Ni-0.5Mg Alloy Modified with Ca/P and TCB Complex. Metals, 15(11), 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111276