Selective Oxidation Control for Synchronous Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention from Vanadium- and Chromium-Bearing Hot Metal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamic Analysis for Oxidative Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention in Hot Metal

2.1. Optimal Temperature Control Strategy

- Region I (T < 1517 K):

- Region II (1517 K < T < 1704 K):

- Region III (T > 1704 K):

2.2. Oxygen Partial Pressure Control

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Raw Materials

3.2. Experimental Apparatus

3.3. Experimental Design

3.4. Experimental Procedure

3.5. Calculation Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effect of Temperature on Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

4.1.1. Temperature-Dependent Oxidation and Separation of [V] and [Cr] in Hot Metal

4.1.2. Carbon-Mediated Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

4.1.3. Temperature-Dependent Migration Behavior of Vanadium and Chromium

4.2. Effect of FeO Content on Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

4.2.1. FeO-Dependent Oxidative Separation of [V] and [Cr]

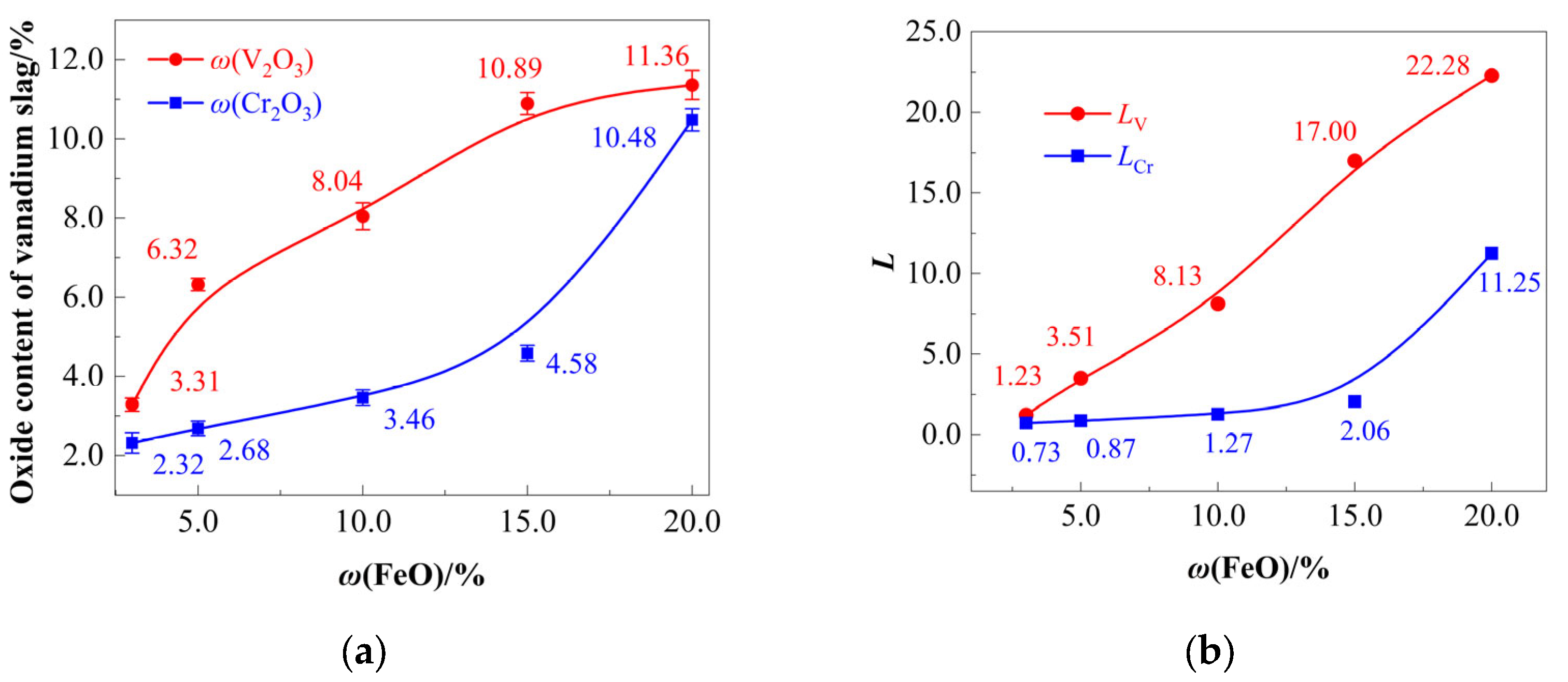

- Region I(O) (V-Dominant Zone, ω(FeO) = 3–10%): ηV increases sharply due to preferential vanadium oxidation (thermodynamically favored; Section 2.2), while ηCr increases marginally;

- Region II(O) (Cr-Activation Zone, ω(FeO) = 10–15%): ηCr oxidation accelerates;

- Region III(O) (Cr-Runaway Zone, ω(FeO) > 15%): ηCr undergoes rapid escalation, exceeding chromium’s oxidation threshold.

4.2.2. FeO-Dependent Migration of Vanadium and Chromium

4.3. Comprehensive Discussion on the Synergistic Control of Temperature and Oxygen Potential

4.4. Comparative Analysis of the Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention (VECR) Process with Conventional Methods

5. Conclusions

- The thermodynamic analysis established that the temperature window of 1517–1704 K is critical, as it enables carbon to function as an effective redox mediator. Within this regime, the oxidation priority of [V] > [C] > [Cr] creates a thermodynamic pathway for selective V extraction. Furthermore, there is a hierarchy of oxygen partial pressure required for oxidizing vanadium and chromium. An optimal oxygen partial pressure window of −11.91 to −10.94 (logarithmic scale) at 1723 K was identified to achieve high V oxidation while suppressing Cr loss. This theoretical prediction provides a key parameter window for optimizing experimental conditions, and its core conclusion is directly verified in subsequent experiments.

- Temperature-dependent experiments demonstrate the differential responses of ηV and ηCr: vanadium oxidation exhibits higher temperature sensitivity than chromium, a phenomenon attributed to the stronger protective effect of carbon on chromium compared to its promoting effect on vanadium extraction. The optimal temperature range is 1693–1753 K (SIV-Cr > 0.67). In the low-temperature region (<1693 K), vanadium oxidation is incomplete, whereas in the high-temperature region (>1753 K), the separation efficiency deteriorates.

- Both ηV and ηCr increase upon adding FeO, with ηV consistently exceeding ηCr. [V] oxidation occurs preferentially at lower FeO dosages. The optimal FeO dosage range is 10.0–15.7%. FeO contents exceeding this range lead to the over-oxidation of [Cr], while insufficient FeO additions result in incomplete [V] oxidation.

- Under optimized process conditions, ηV exceeds 72.5%, while ηCr remains below 42.9%. These conditions result in a reduction of ω[V] to less than 1%, while ω[Cr] remains above 2.17%. Additionally, ω(V2O3) and ω(Cr2O3) are 10.88–14.01% and 3.46–7.31%, respectively, meeting the criteria for recycling low-chromium vanadium slag. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the process for selectively oxidizing vanadium while minimizing chromium oxidation losses.

- Compared to traditional processes, the proposed VECR method demonstrates significant advantages. It reduces oxygen consumption by over 80 kg/tFe and Cr oxidation losses by more than 40%, directly translating to lower operational costs and enhanced resource utilization. The resulting V-Cr slag, with 10.88–14.01% V2O3 and 3.5–7.3% Cr2O3, meets the industrial standard for low-Cr feedstock. Most importantly, this process completely eliminates the need for the energy-intensive roasting and complex hydrometallurgical steps, offering a shorter, cleaner, and more economical flowsheet.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Diao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Xie, B. Highly efficient utilization of hazardous vanadium extraction tailings containing high chromium concentrations by carbothermic reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, Q.; Lv, W.; Pei, G.; Lv, X.; Bai, C. Recovery of tailings from the vanadium extraction process by carbothermic reduction method: Thermodynamic, experimental and hazardous potential assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 357, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, Q.; Lv, W.; Pei, G.; Lv, X.; Liu, S. Co-recovery of iron, chromium, and vanadium from vanadium tailings by semi-molten reduction–magnetic separation process. Can. Metall. Q. 2018, 57, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Jiang, M. Self-digestion of Cr-bearing vanadium slag processing residue via hot metal pre-treatment in steelmaking process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2022, 53, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, C. Chromium and iron recovery from hazardous extracted vanadium tailings via direct reduction magnetic separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-W.; Yang, M.-E.; Meng, Y.-Q.; Gao, D.-X.; Wang, M.-Y.; Fu, Z.-B. Cyclic metallurgical process for extracting V and Cr from vanadium slag: Part I. Separation and recovery of V from chromium-containing vanadate solution. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kauppinen, T.; Tynjälä, P.; Hu, T.; Lassi, U. Water leaching of roasted vanadium slag: Desiliconization and precipitation of ammonium vanadate from vanadium solution. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 215, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Gao, M.; Feng, G. Extraction of vanadium from vanadium slag by sodium roasting-ammonium sulfate leaching and removal of impurities from weakly alkaline leach solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, K.; Luo, D. Optimization and kinetic analysis of co-extraction of vanadium (IV) and chromium (III) from high chromium vanadium slag with titanium dioxide waste acid. Miner. Eng. 2025, 233, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, T. A sustainable chromium and vanadium extraction and separation process from high-chromium vanadium slag via synchronous roasting and asynchronous leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 133020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, T.; Wen, J.; Yu, T.; Li, F. Review of leaching, separation and recovery of vanadium from roasted products of vanadium slag. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 226, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, F.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhen, Y.; Qi, T.; Zheng, S.; Wang, M. A novel process to prepare high-purity vanadyl sulfate electrolyte from leach liquor of sodium-roasted vanadium slag. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 208, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Chen, X.-M.; Hai, D.; Diao, J.; Xie, B. Eco-friendly chromium recovery from hazardous chromium-containing vanadium extraction tailings via low-dosage roasting. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Du, G.-C.; Wang, J.-P.; Wu, Z.-X.; Li, H.-Y. Eco-friendly efficient separation of Cr (VI) from industrial sodium vanadate leaching liquor for resource valorization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G. Comparison and evaluation of vanadium extraction from the calcification roasted vanadium slag with carbonation leaching and sulfuric acid leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 297, 121466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ren, Q.; Tian, J.; Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Shang, Y.; Liu, J.; Fu, L. Efficient recovery of vanadium from calcification roasted-acid leaching tailings enhanced by ultrasound in H2SO4-H2O2 system. Miner. Eng. 2024, 205, 108492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Ye, L.; Du, J. Research progress of vanadium extraction processes from vanadium slag: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 342, 127035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Y. Removal of sodium from vanadium tailings by calcification roasting in reducing atmosphere. Materials 2023, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, B.; Wang, C. Non-salt roasting mechanism of V–Cr slag toward efficient selective extraction of vanadium. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 126, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Du, H.; Gao, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Direct Leaching of Vanadium from Vanadium-bearing Steel Slag Using NaOH Solutions: A Case Study. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2020, 42, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunikata, Y.; Morita, K.; Tsukihashi, F.; Sano, N. Equilibrium Distribution Ratios of Phosphorus and Chromium between BaO-MnO Melts and Carbon Saturated Fe-Cr-Mn Alloys at 1573 K. ISIJ Int. 2007, 34, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turkdogen, E.T. Fundamentals of Steelmaking; Stainless Steel Industry; The Institute of Materials: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shyrokykh, T.; Neubert, L.; Volkova, O.; Sridhar, S. Two Potential Ways of Vanadium Extraction from Thin Film Steelmaking Slags. Processes 2023, 11, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, W. Physical Chemistry An Advanced Treatise; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chimenos, J.M.; Cuspoca, F.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Mañosa, J.; Rosell, J.R.; Andrés, A.; Faneca, G.; Cabeza, L.F. MSW incineration bottom ash-based alkali-activated binders as an eco-efficient alternative for urban furniture and paving: Closing the loop towards sustainable construction solutions. Buildings 2025, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.K.; Rady, M.; Tawfik, N.M.; Kassem, M.; Mahfouz, S.Y. Enhancing strength and sustainability of concrete with steel slag aggregate. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, O.; Petrisková, P. Binary and ternary vanadium oxides: General overview, physical properties, and photochemical processes for environmental applications. Processes 2021, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-Y.; Tang, P. Optimization on temperature strategy of BOF vanadium extraction to enhance vanadium yield with minimum carbon loss. Metals 2021, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-Y.; Tang, P.; Hou, Z.-B.; Wen, G.-H. Investigation of the end-point temperature control based on the critical temperature of vanadium oxidation during the vanadium extraction process in BOF. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2018, 71, 1957–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, B.; Li, X.; Xiao, F. Influence of Vanadium Extraction Converter Process Optimization on Vanadium Extraction Effect. Metals 2022, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, H.; Brungs, M. Oxidation-reduction equilibria of vanadium in CaO-SiO2, CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 and CaO-MgO-SiO2 melts. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lin, M.-M.; Diao, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Xie, B.; Li, G. Novel strategy for green comprehensive utilization of vanadium slag with high-content chromium. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 18133–18141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Sun, Y.; Ning, P.; Xu, G.; Sun, S.; Sun, Z.; Cao, H. Deep understanding of sustainable vanadium recovery from chrome vanadium slag: Promotive action of competitive chromium species for vanadium solvent extraction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 422, 126791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-c.; Kim, E.-y.; Chung, K.W.; Kim, R.; Jeon, H.-S. A review on the metallurgical recycling of vanadium from slags: Towards a sustainable vanadium production. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam, C.; Prathap, K. Recycling Fe (III)/Cr (III) hydroxide, an industrial solid waste for the removal of phosphate from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 123, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Cao, W.; Liang, Y.; Rohani, S.; Xin, Y.; Hua, J.; Ding, C.; Lv, X. Green and efficient separation of vanadium and chromium from high-chromium vanadium slag: A review of recent developments. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 10006–10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | C | Si | Mn | Cr | V |

| Content | 4.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| −0.12 | −0.0003 | −0.16 | 0.015 |

| Materials | Fe | V | Cr | C | Si | Mn | S | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF iron powder | 88.50 | 4.00 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.005 | 0.005 | ||

| FeV50 powder | 47.10 | 50.00 | 0.65 | 1.45 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| HC FeCr powder | 42.50 | 49.53 | 7.45 |

| Heat No. | Design Stage | Temperature/K | ω(FeO) in Final Slag (Set Value), % | Initial Slag, g | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeO | CaO | SiO2 | R2 | ||||

| 1 | 1 (Temp) | 1633 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.9 | 1.8 |

| 2 | 1 (Temp) | 1663 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.9 | |

| 3 | 1 (Temp) | 1693 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.9 | |

| 4 | 1 (Temp) | 1723 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.9 | |

| 5 | 1 (Temp) | 1753 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.9 | |

| 6 | 2 (FeO) | 1723 | 3.0 | 12.1 | 21.6 | 10.9 | |

| 7 | 2 (FeO) | 1723 | 5.0 | 12.9 | 21.0 | 10.6 | |

| 8 | 2 (FeO) | 1723 | 15.0 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 9.1 | |

| 9 | 2 (FeO) | 1723 | 20.0 | 19.1 | 17.1 | 8.4 | |

| Region | Name | ω(FeO) Range | Dominant Process | ηV/ηCr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (O) | V-Dominant Zone | 3–10% | Vanadium Preferential Oxidation | 2.5–3.1 |

| II (O) | Cr-Activation Zone | 10–15% | Chromium Oxidation Activation | 1.8–2.4 |

| III (O) | Cr-Runaway Zone | >15% | Chromium Massive Oxidation | <1.1 |

| Parameter | Traditional Process | VECR Process | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature/K | 1623–1693 [29,30] | 1693–1753 | +65 K (optimized oxidation) |

| Oxygen supply/kg·(tFe)−1 | 43.0–195.0 | 33.1–38.2 | >80 kg/tFe reduction |

| ηV/% | 75.0–90.0 [29] | 72.5–82.2 | Comparable efficiency |

| ηCr/% | 50.0–70.0 [31] | 28.2–42.9 | >40% reduction |

| ω(V2O3)/% | 8.2–16.5 [32,33] | 10.9–14.0 | Higher purity |

| ω(Cr2O3)/% | 5.0–10.0 | 3.5–7.3 | Meets low-Cr standards |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.-Y.; Zhao, H.-Q.; Wang, L.-F.; Liu, Q.-C.; Yan, D.-L.; Wang, F.; Qi, Y.-H. Selective Oxidation Control for Synchronous Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention from Vanadium- and Chromium-Bearing Hot Metal. Metals 2025, 15, 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111275

Wang X-Y, Zhao H-Q, Wang L-F, Liu Q-C, Yan D-L, Wang F, Qi Y-H. Selective Oxidation Control for Synchronous Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention from Vanadium- and Chromium-Bearing Hot Metal. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111275

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xin-Yu, Hai-Quan Zhao, Lu-Feng Wang, Qiao-Chu Liu, Ding-Liu Yan, Feng Wang, and Yuan-Hong Qi. 2025. "Selective Oxidation Control for Synchronous Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention from Vanadium- and Chromium-Bearing Hot Metal" Metals 15, no. 11: 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111275

APA StyleWang, X.-Y., Zhao, H.-Q., Wang, L.-F., Liu, Q.-C., Yan, D.-L., Wang, F., & Qi, Y.-H. (2025). Selective Oxidation Control for Synchronous Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention from Vanadium- and Chromium-Bearing Hot Metal. Metals, 15(11), 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111275