Effect of Aluminum Content on the Corrosion Behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C Structural Steels in Marine Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Test Materials and Preparation

2.2. Full-Immersion Corrosion Test

2.3. Characterization and Analysis of Corrosion Products

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

- -

- The working electrode is a corroded sample with an exposed area of 1 cm2.

- -

- The reference electrode is a saturated calomel electrode.

- -

- The counter electrode is a platinum electrode with an exposed area of 0.5 cm2. Before the electrochemical test, the working electrode was subjected to an open circuit potential test for 1 h to ensure that the three-electrode system was in a steady state. The parameters of the Tafel test were as follows: the test potential range was set to −2.0~1.0 V, and the scanning rate was 0.01667 mV/s. The parameters of the electrochemical impedance test were as follows: the frequency range was set to 105 Hz~10−2 Hz, and the applied disturbance potential amplitude was ±10 mV.

3. Results

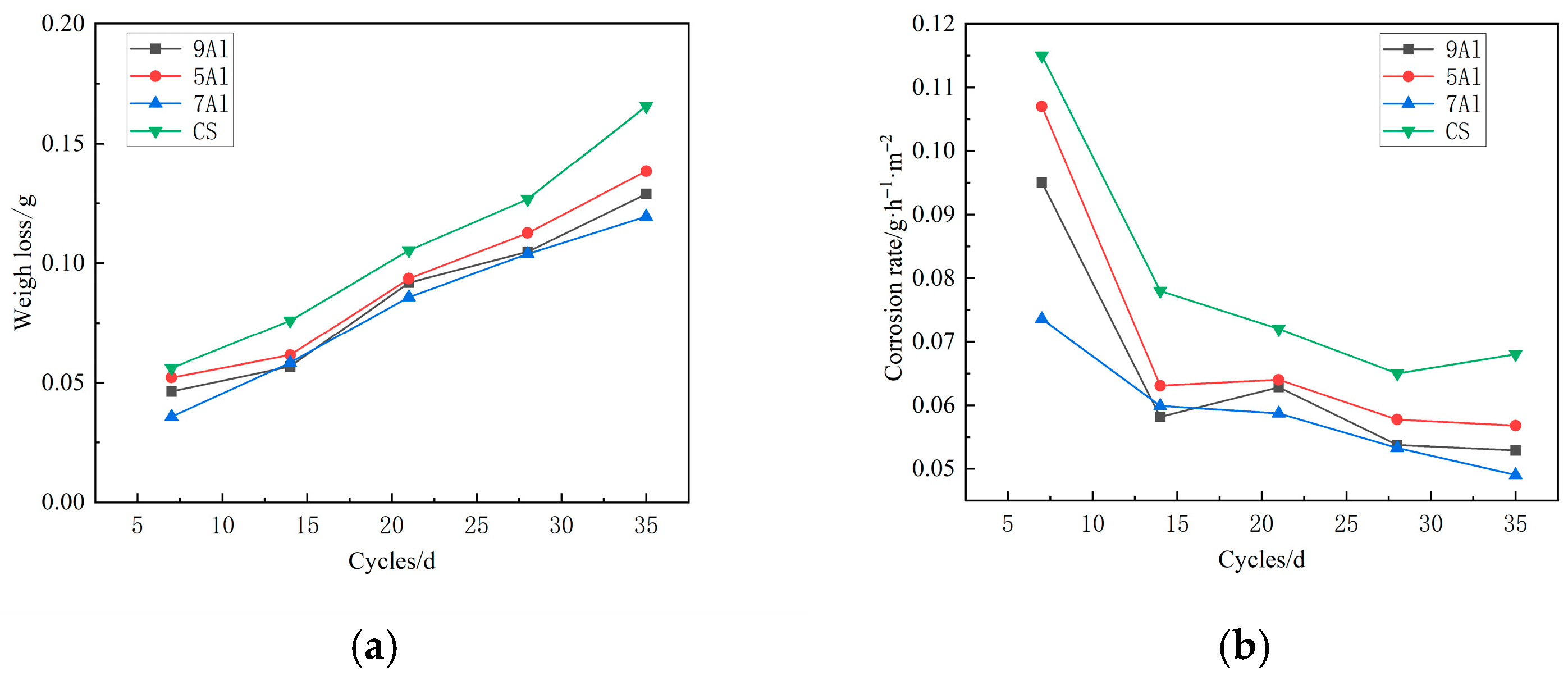

3.1. Corrosion Kinetics

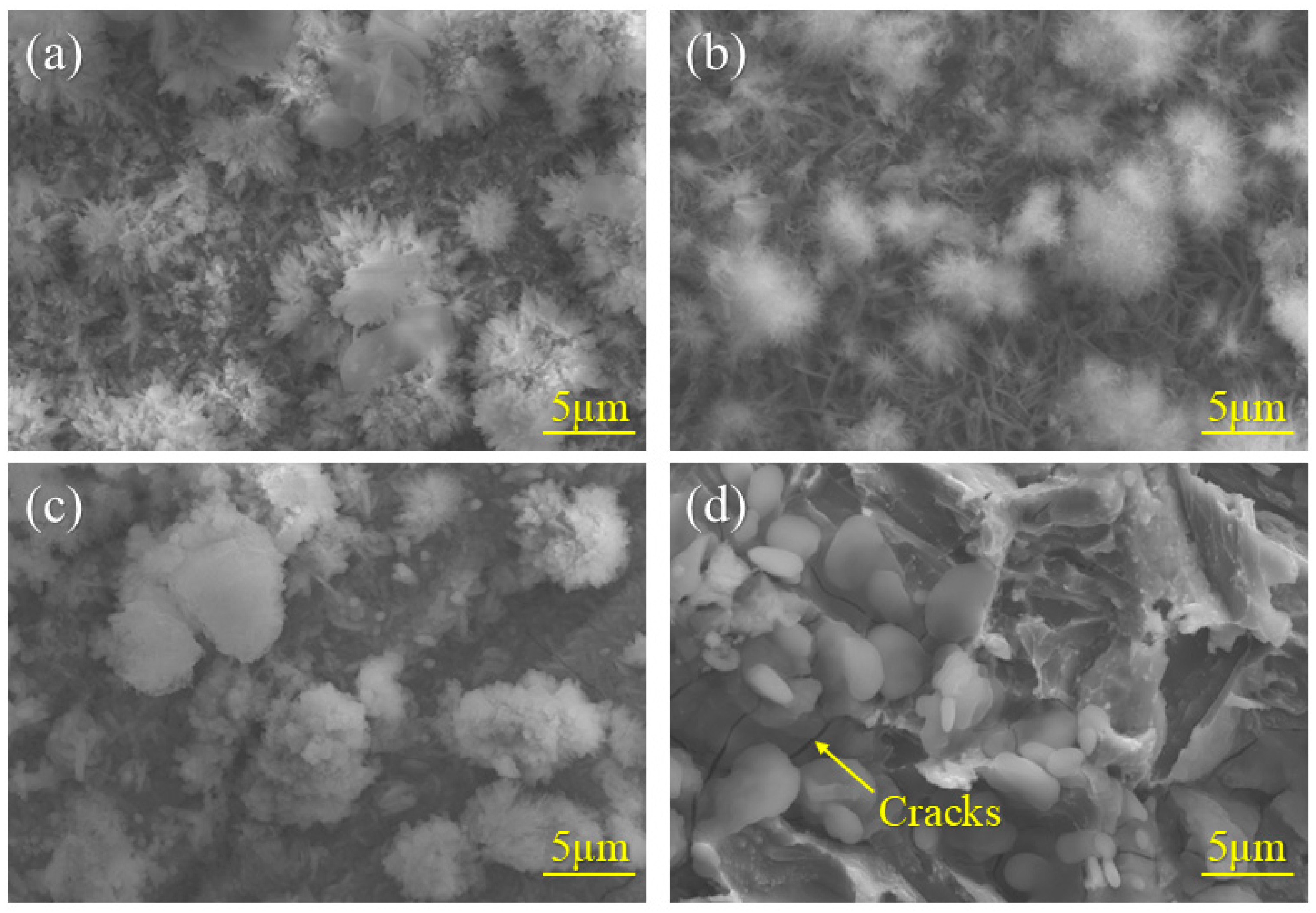

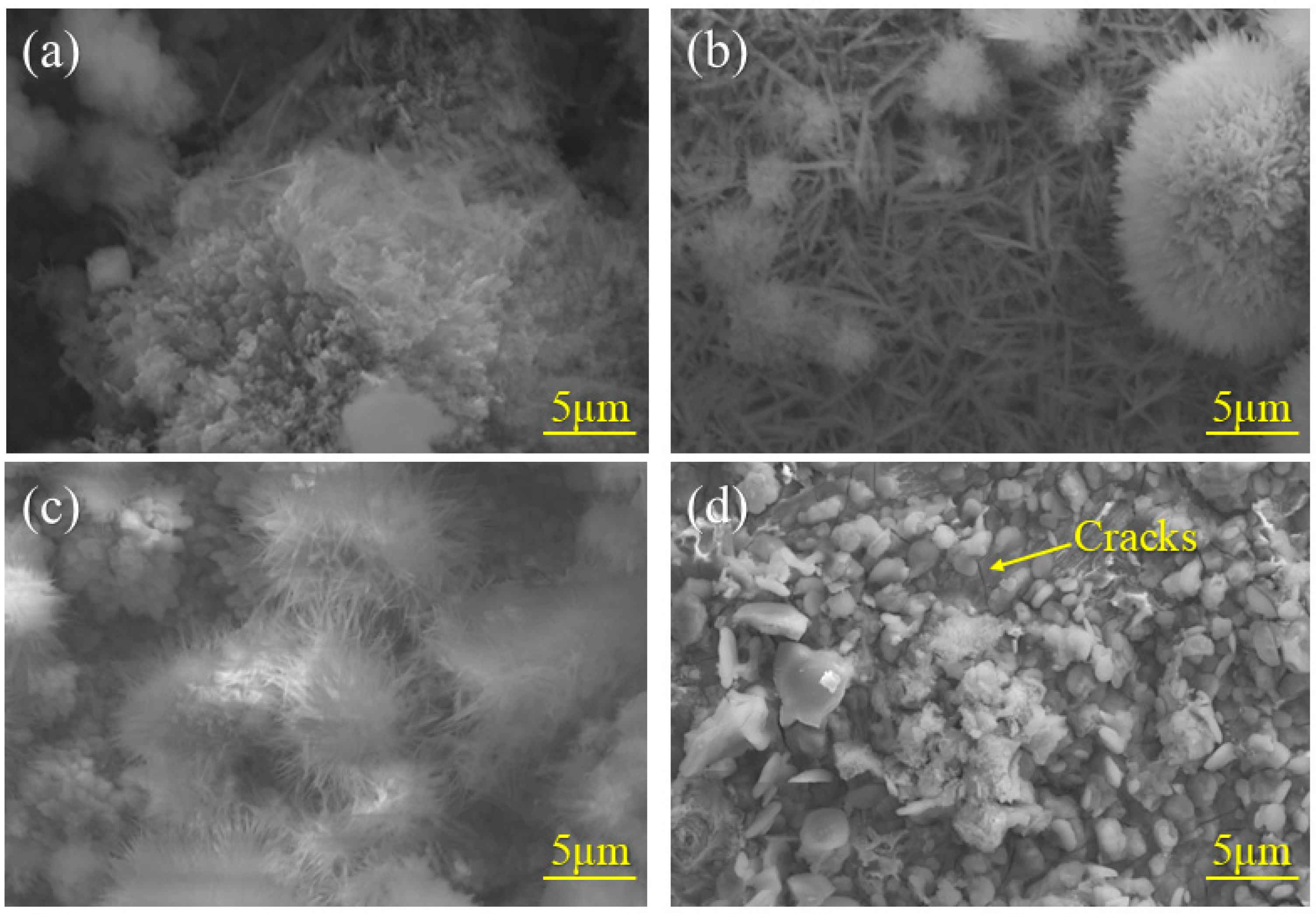

3.2. Macroscopic Studies of Corrosion Products

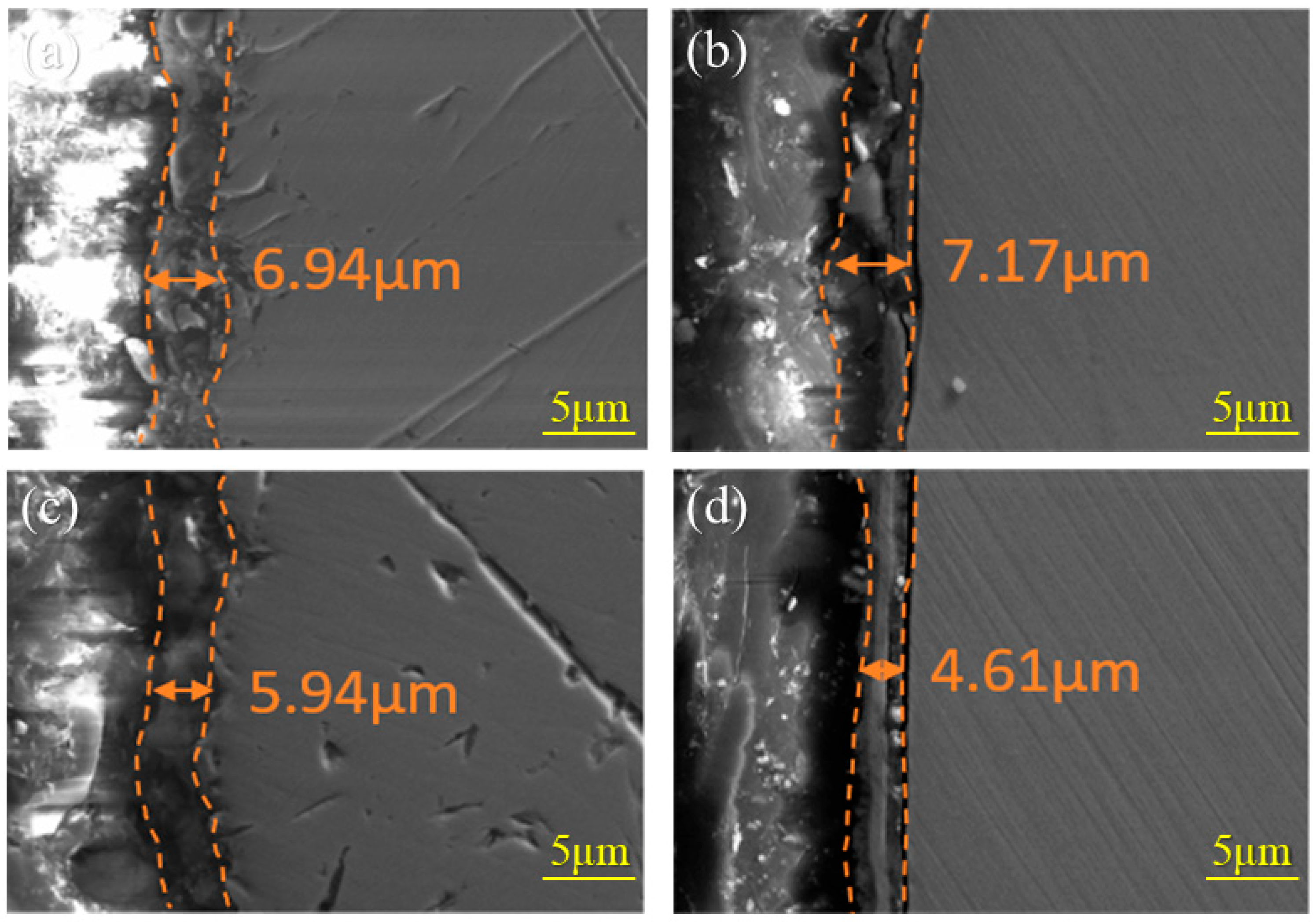

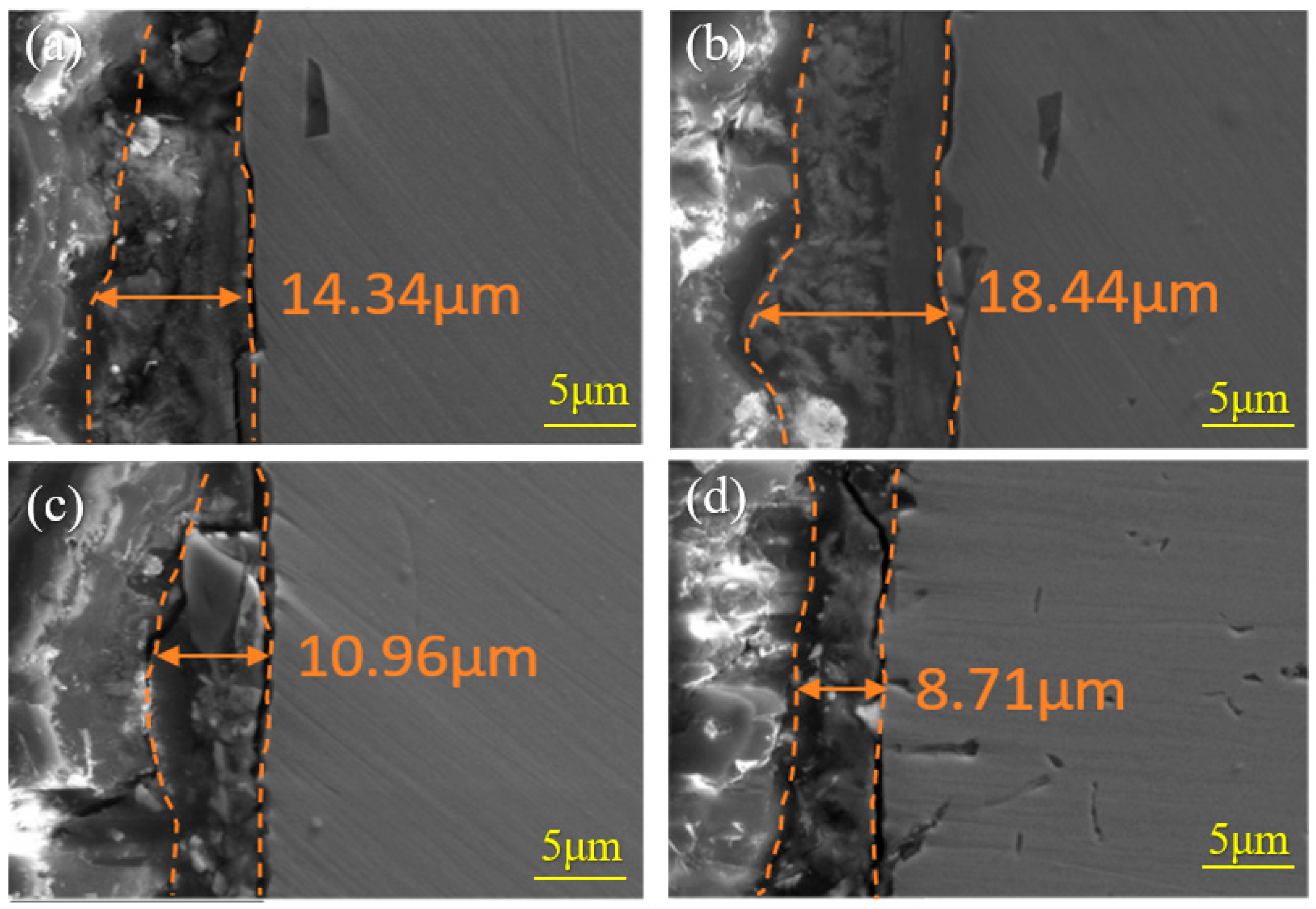

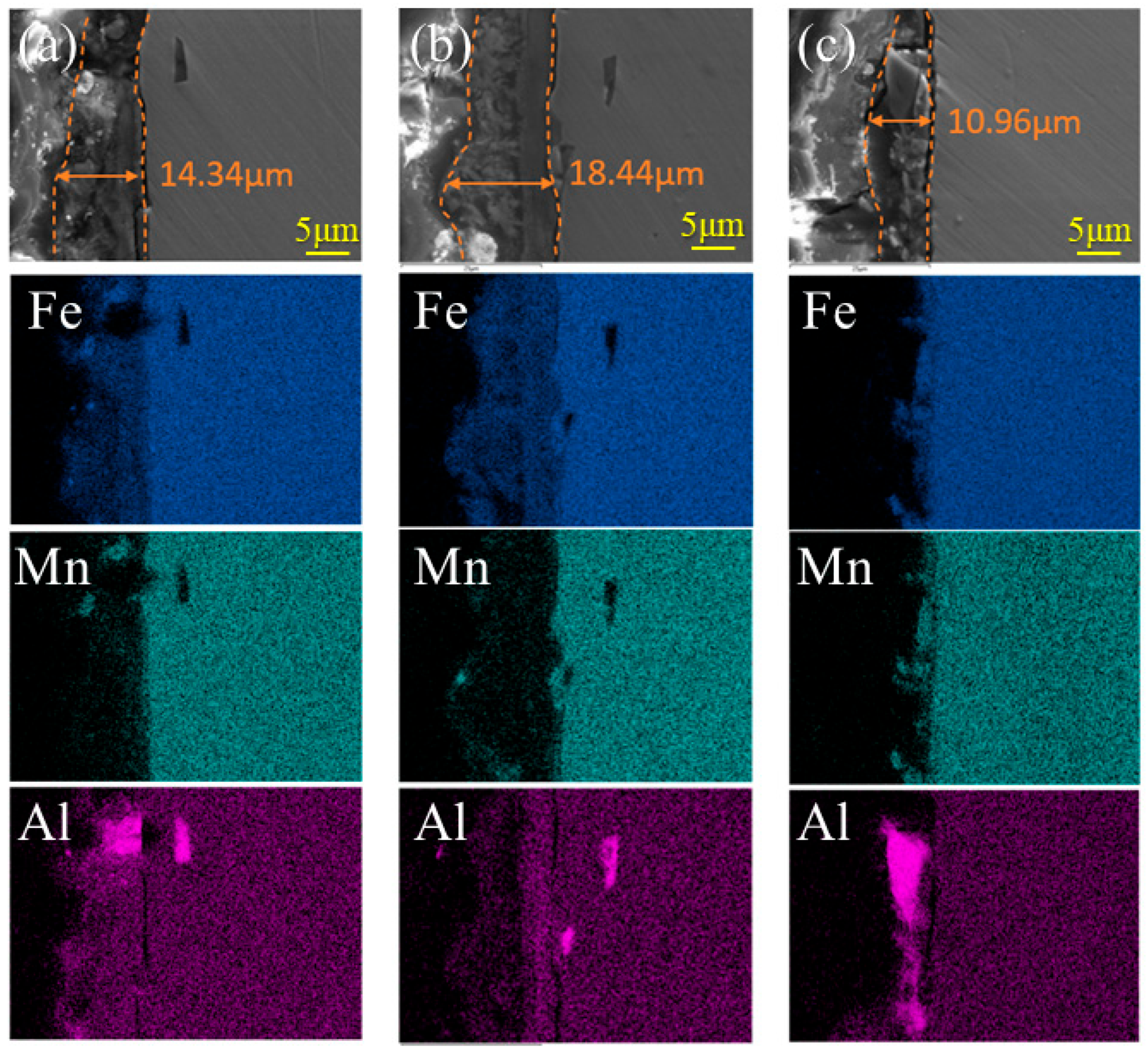

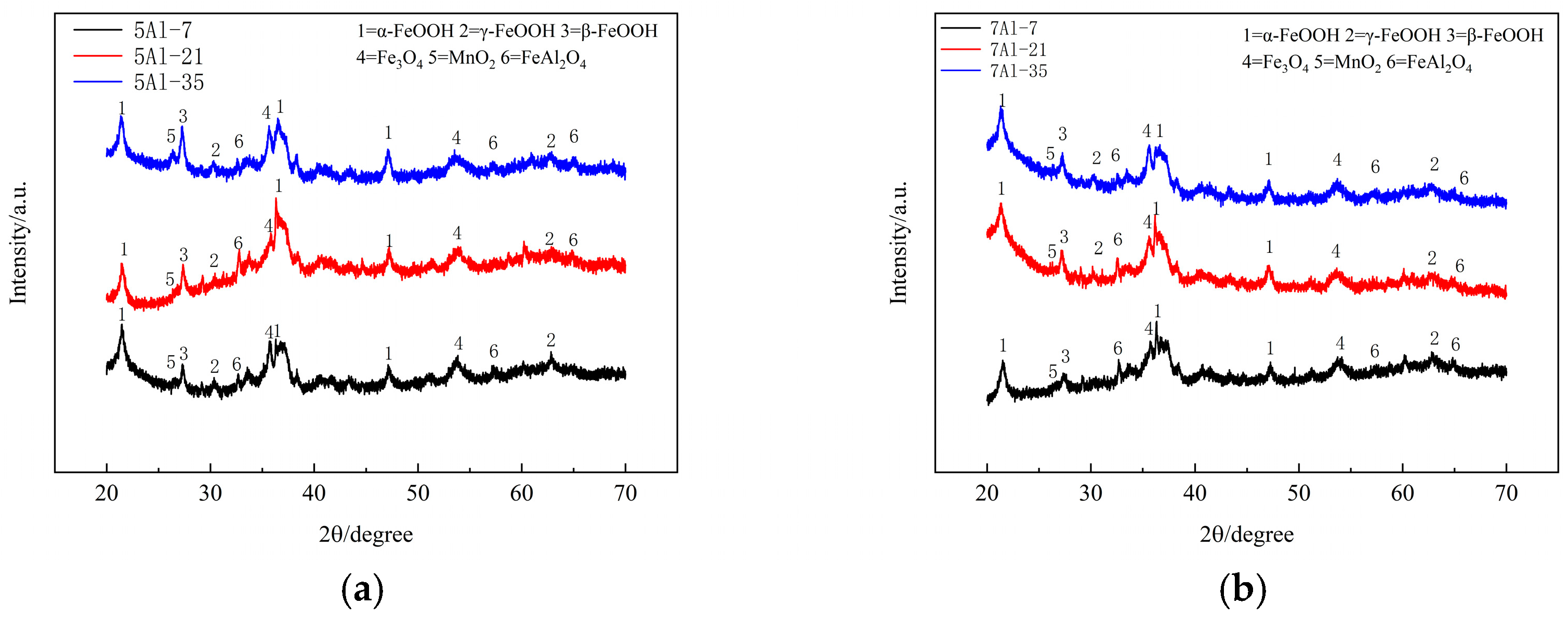

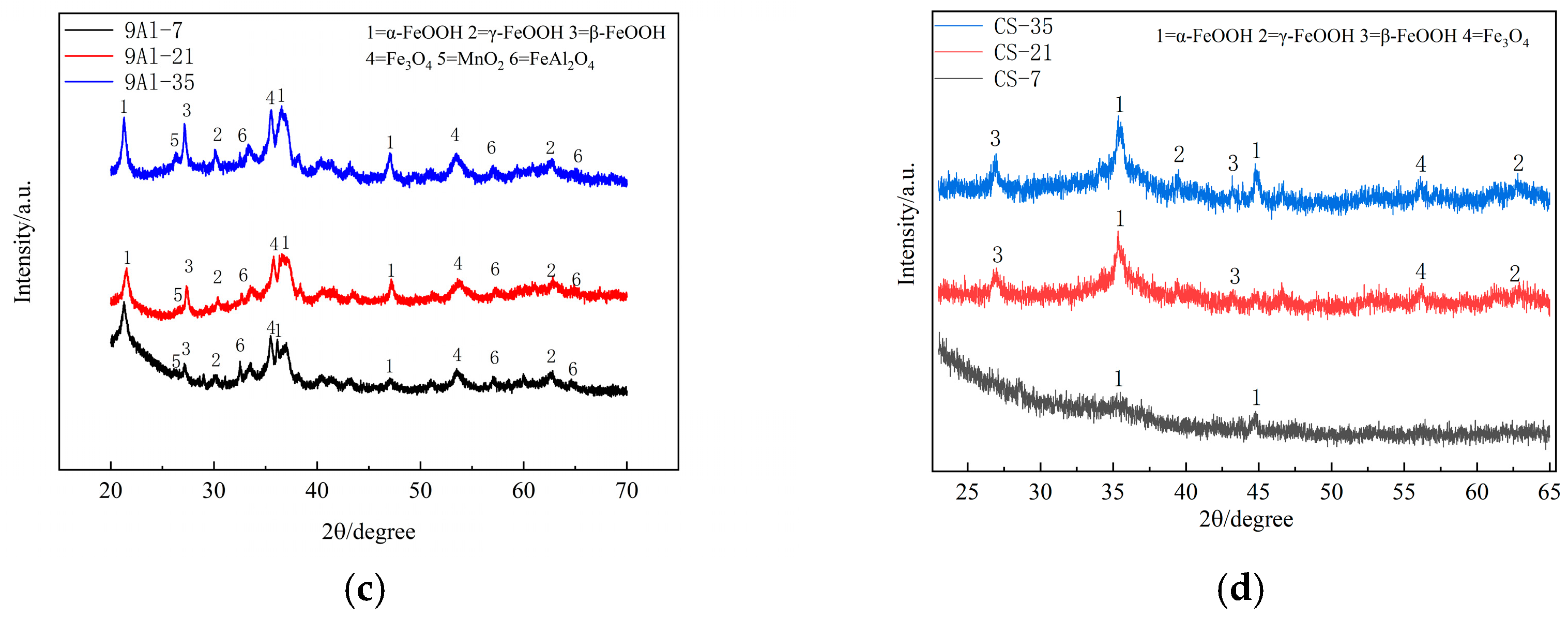

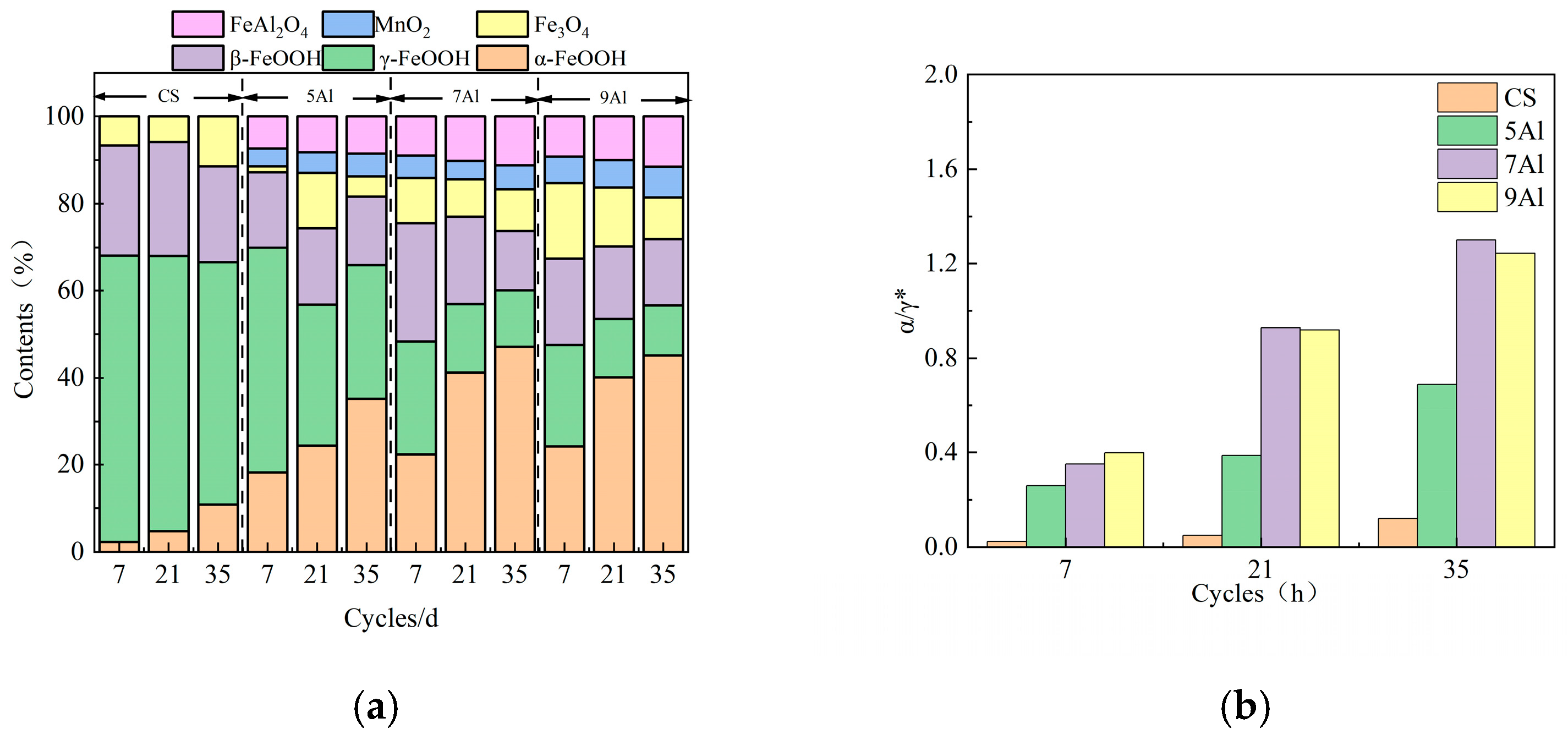

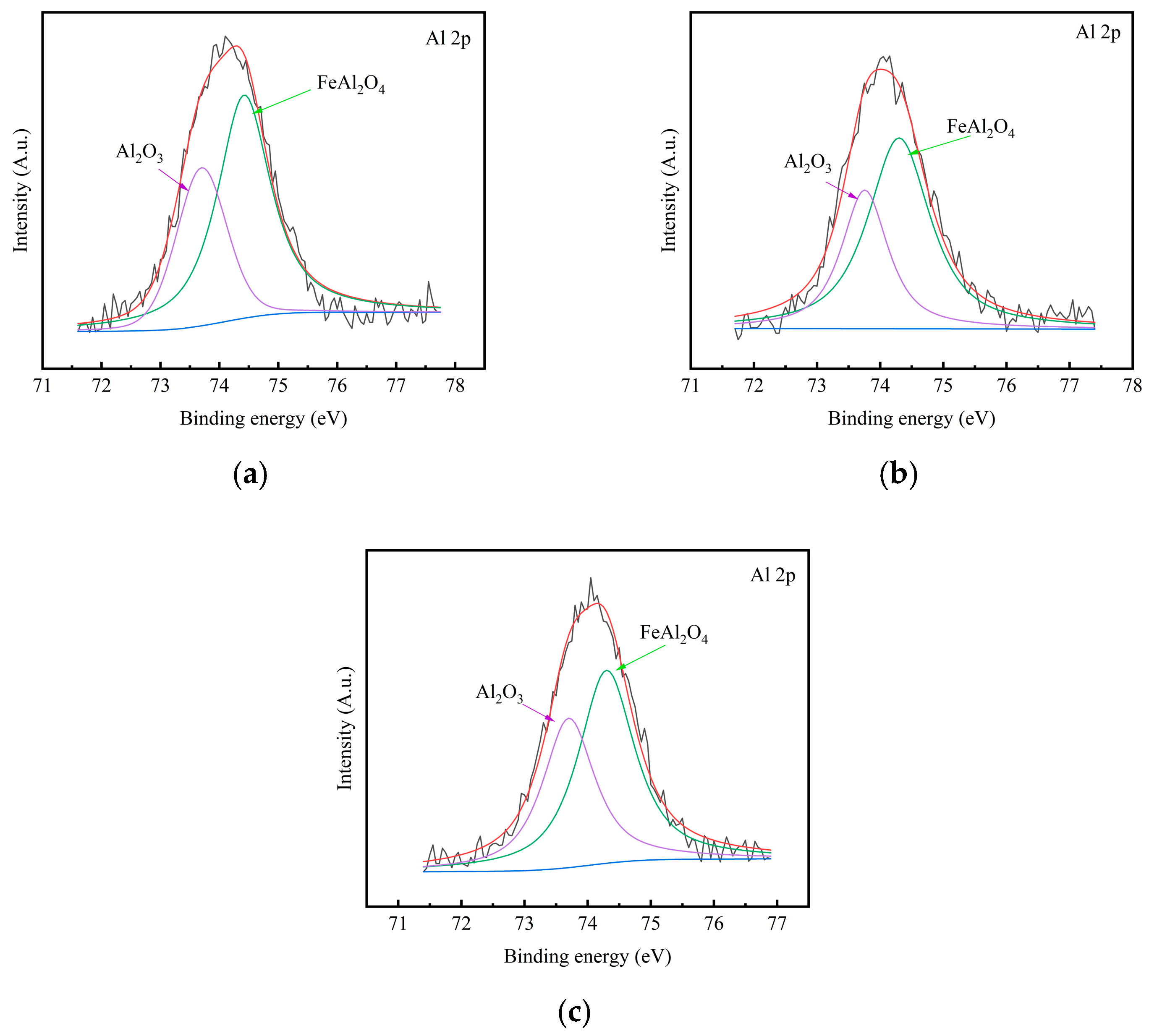

3.3. Composition of the Rust Layer

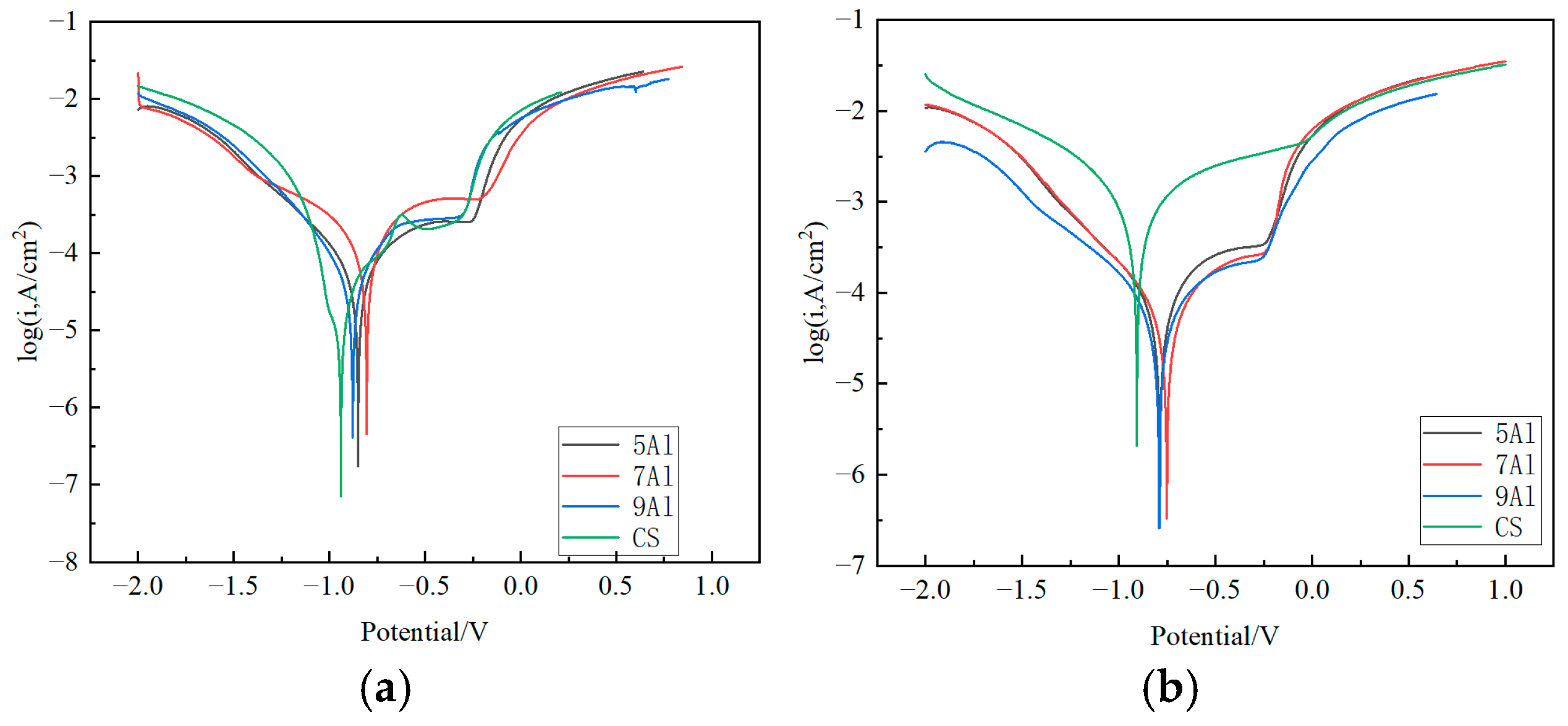

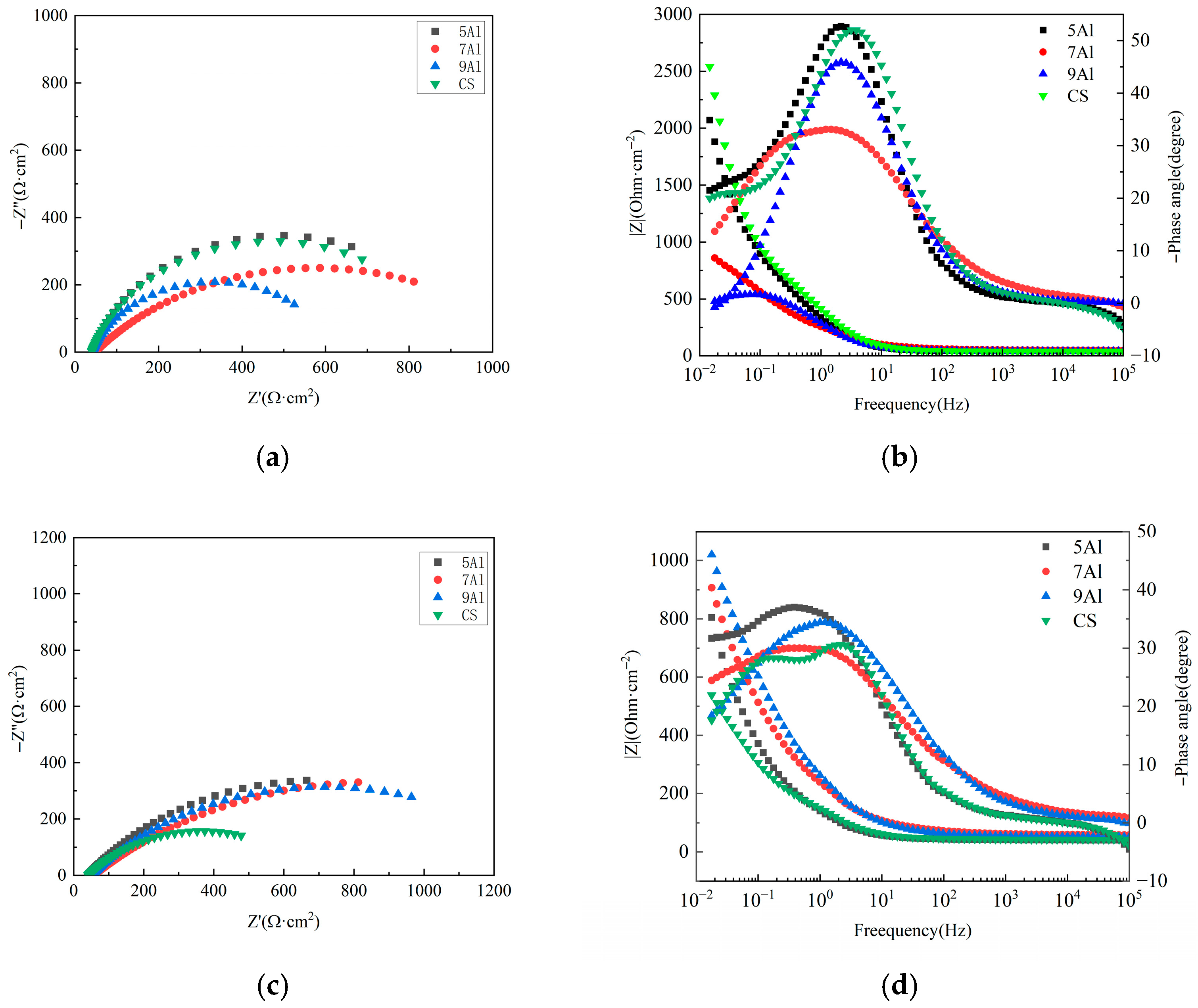

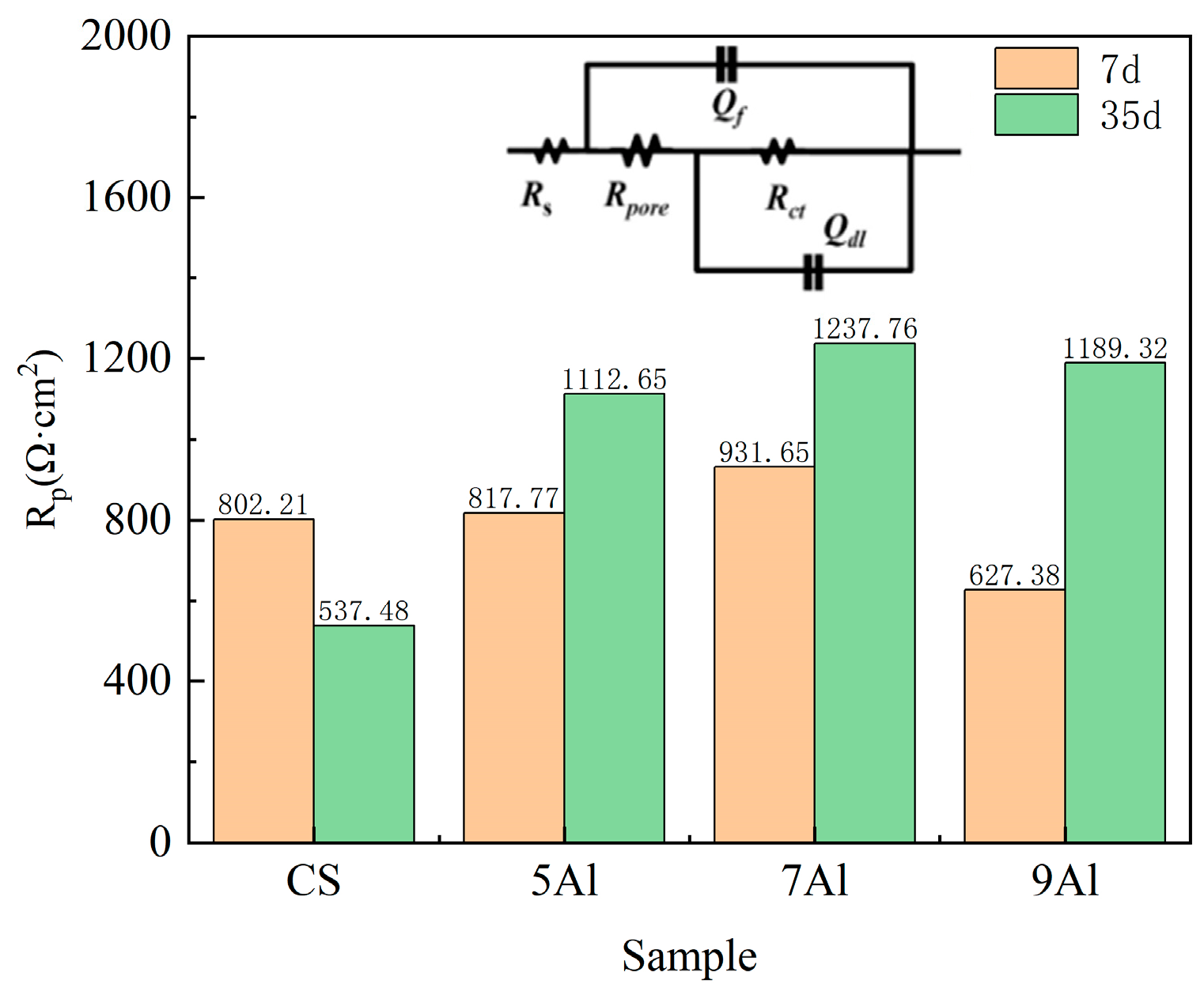

3.4. The Rust Layer’s Electrochemical Properties

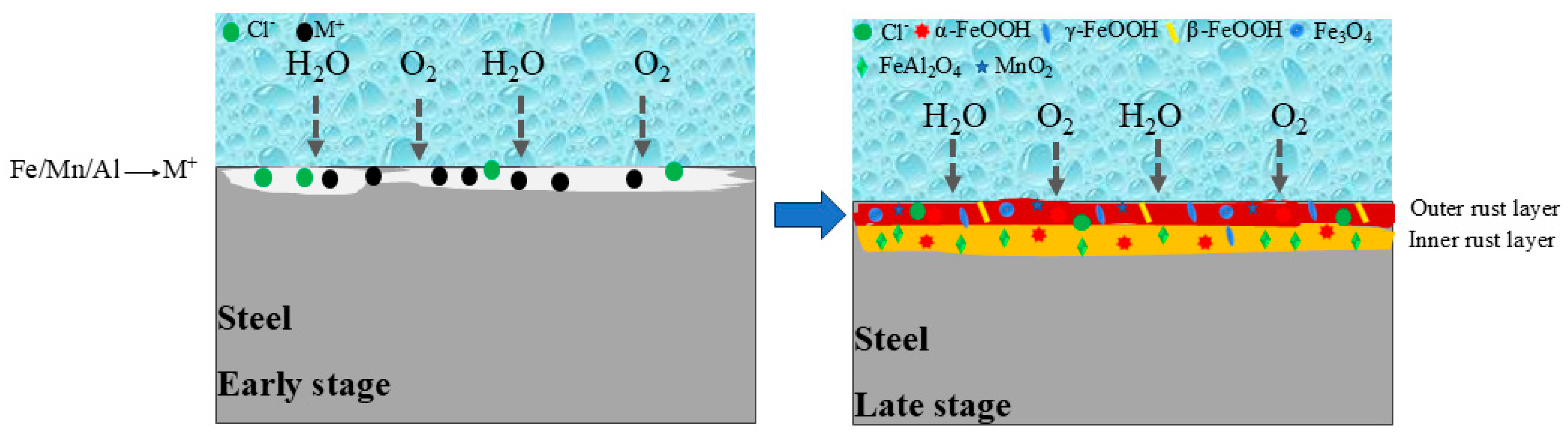

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The addition of Al can significantly reduce the corrosion weight loss and corrosion rate of steel among 5~9%Al contents. Among them, 7Al steel and 9Al steel have the lowest and similar corrosion rates, and the corrosion resistance has increased by two times. Hence, 7% Al content is the key threshold for improving corrosion resistance.

- Al can effectively form Al-rich oxides within the rust layer. These oxides act as a stable protective phase, thereby enhancing the corrosion resistance. FeAl2O4, as a nucleation site, refines rust layer grains, reduces internal pores and cracks, and enhances the physical barrier effect. However, as the standard electrode potential of Al is too low, excessively high Al content would lead to excessive dissolution and increase the corrosion rate.

- The electrochemical stability of Al-containing steels is significantly better than that of CS. The 7Al steel has the highest Rp value (1237.76 Ω·cm2), and the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and rust layer pore resistance (R(pores)) increase simultaneously, indicating that its rust layer has the strongest blocking effect on electrochemical reactions and the best corrosion resistance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veis, V.; Semenko, A.; Voron, M.; Tymoshenko, A.; Likhatskyi, R.; Likhatskyi, I.; Parkhomchuk, Z. Lightweight Fe–Mn–Al–C Steels: Current State, Manufacturing, and Implementation Prospects. Steel Res. Int. 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Suh, D.W.; Kim, N.J. Fe–Al–Mn–C lightweight structural alloys: A review on the microstructures and mechanical properties. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2013, 14, 14205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, B.; Moon, J.; Park, S.J.; Lee, C. Influence of κ-carbide precipitation on the microstructure and mechanical properties in the weld heat-affected zone in various FeMnAlC alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 726, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.X.; Li, J.N.; Chen, K.; Xu, G.; Yang, Y.K.; Li, X.M. Research status of high-manganese high-aluminum steel and key points of continuous casting. Jom 2024, 76, 7011–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.D.; Wan, S.; Yang, Y.; Su, Q.; Han, W.W.; Zhu, Y.B. Accelerated corrosion behavior of weathering steel Q345qDNH for bridge in industrial atmosphere. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, E.; Heidarpour, A.; Javidan, F. Mechanical performance of high strength steel under corrosion: A review study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 220, 108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Banis, A.; Avella, M.; Molina-Aldareguia, J.M.; Petrov, R.H.; Dutta, A.; Sabirov, I. The effect of κ-carbides on high cycle fatigue behavior of a Fe-Mn-Al-C lightweight steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 184, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghdadi, N.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A.; Farabi, E.; Cizek, P.; Beladi, H.; Hodgson, P.D. Strain rate dependence of ferrite dynamic restoration mechanism in a duplex low-density steel. Mater. Des. 2017, 132, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Cai, J.; Cheng, X. Evaluating the effect of aluminum on the corrosion resistance of the structural steels used for marine engineering. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 4181–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, B.; Ji, P.; Zhang, X.; Ma, M.; Liu, R. Benefit of the rust layer formed on AlMn lightweight weathering steel in industrial atmosphere. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 394, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ji, P.; Li, B.; Xia, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, R. Optimizing the corrosion performance of rust layers: Role of Al and Mn in lightweight weathering steel. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Tahara, A.; Kodama, T. Effect of Al on the Corrosion Behavior of Low Alloy Steels in Wet/Dry Environment. Mater. Trans. 2001, 7, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wu, W.; Jiang, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z. Optimizing the resistance of Ni-advanced weathering steel to marine atmospheric corrosion with the addition of Al or Mo. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 279, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 7901-1999; Metals Materials—Uniform Corrosion-Methods of Laboratory Immersion Testing. State Administration of Machinery Industry: Beijing, China, 1999.

- Brash, D.E.; Rudolph, J.A.; Simon, J.A.; Lin, A.; Mckenna, G.J.; Baden, H.P.; Ponten, H.J. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 10124–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, X.; Dong, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Gu, X. Layer-by-layer investigation of the multilayer corrosion products for different Ni content weathering steel via a novel Pull-off testing. Corros. Sci. 2021, 195, 109988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Dong, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. Insights into the corrosion mechanism and electrochemical properties of the rust layer evolution for weathering steel with various Cl deposition in the simulated atmosphere. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 36515–36518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Jin, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, X. Optimizing the nickel content in weathering steels to enhance their corrosion resistance in acidic atmospheres. Corros. Sci. 2017, 115, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, X. Benefit of the corrosion product film formed on a new weathering steel containing 3% nickel under marine atmosphere in Maldives. Corros. Sci. 2019, 165, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, T.; Hara, S.; Miyuki, H.; Yamashita, M.; Uchida, H. Composition and protective ability of rust layer formed on weathering steel exposed to various environments. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 2799–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Song, S.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Xia, D.H. Electrochemical Noise Monitoring of the Atmospheric Corrosion of Steels: Identifying Corrosion Form Using Wavelet Analysis. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhang, S.; Dong, J.; Ke, W. Evolution of corrosion of MnCuP weathering steel submitted to wet/dry cyclic tests in a simulated coastal atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Dong, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. The Role of the Direct Current Electric Field in Enhancing the Protective Rust Layer of Weathering Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 6309–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, F. Tafel slopes and corrosion rates obtained in the pre-Tafel region of polarization curves. Corros. Sci. 2005, 47, 3178–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyab, M.A.; Mohsen, Q. Inhibitory influence of cationic Gemini surfactant on the dissolution rate of N80 carbon steel in 15% HCl solution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyab, M.A.M. Corrosion Inhibition and Adsorption Behavior of Sodium Lauryl Ether Sulfate on L80 Carbon Steel in Acetic Acid Solution and Its Synergism with Ethanol. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2015, 18, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazo, A.; Nóvoa, X.R.; Pérez, C.; Puga, B. EIS study of the rust converter effectiveness under different conditions. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 7565–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J. Is niobium more corrosion-resistant than commercially pure titanium in fluoride-containing artificial saliva? Electrochim. Acta 2017, 233, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcia, O.E.; D’Elia, E.; Frateur, I.; Mattos, O.R.; Tribollet, B. Application of the impedance model of de Levie for the characterization of porous electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2002, 47, 2109–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, D. Electrochemical characterization and stress corrosion cracking of E690 high strength steel in wet-dry cyclic marine environments. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 710, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; He, X. Influence of outer rust layers on corrosion of carbon steel and weathering steel during wet–dry cycles. Corros. Sci. 2014, 82, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, M.; Chico, B.; Diaz, I.; Cano, H.; Fuente, D.D.L. Atmospheric corrosion data of weathering steels. A review. Corros. Sci. 2013, 77, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, X.; Du, C.; Li, X. Development and optimization of Ni-advanced weathering steel: A review. Corros. Commun. 2021, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Qin, L.; Cheng, X.; Xu, F.; Li, X. Microstructural evolution and its effect on corrosion behavior and mechanism of an austenite-based low-density steel during aging. Corros. Sci. 2023, 212, 110936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, N. Local Corrosion Chemistry—A Review. Corros. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 73, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, M.A.; Ortíz, M.R.; Iannuzzi, M.; Carranza, R.M. Use of the Critical Acidification Model to Estimate Critical Localized Corrosion Potentials of Duplex Stainless Steels. Corros. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 73, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmadi, A.; Kendrick, J.; Leusen, F.J.J. Crystal structure prediction and isostructurality of three small organic halogen compounds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 8571–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Lv, X. The function of Cr on the rust formed on weathering steel performed in a simulated tropical marine atmosphere environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 277, 122298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Kihira, H.; Ohta, N.; Hashimoto, M.; Senuma, T. Control of Fe(O,OH)6 nano-network structures of rust for high atmospheric-corrosion resistance. Corros. Sci. 2005, 47, 2499–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steel | C | Si | Mn | Al | Cr | Ni | Mo | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.44 | - | <5.0 | Balance | ||

| 5Al | 0.91 | 0.42 | 28.12 | 4.95 | <1.0 | Balance | ||

| 7Al | 0.89 | 0.44 | 28.44 | 7.13 | <1.0 | Balance | ||

| 9Al | 0.88 | 0.41 | 27.89 | 9.19 | <1.0 | Balance | ||

| Cycles | Samples | Ecorr/V (vs. SCE) | Icorr/μA·cm−2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | CS | −0.940 ± 0.011 | 92.33 ± 4.79 |

| 5Al | −0.850 ± 0.014 | 78.73 ± 2.16 | |

| 7Al | −0.805 ± 0.007 | 73.73 ± 2.18 | |

| 9Al | −0.946 ± 0.002 | 82.46 ± 4.13 | |

| 35 days | CS | −0.906 ± 0.008 | 213.7 ± 7.79 |

| 5Al | −0.798 ± 0.006 | 47.24 ± 3.15 | |

| 7Al | −0.768 ± 0.005 | 9.89 ± 0.79 | |

| 9Al | −0.770 ± 0.007 | 13.49 ± 3.01 |

| Samples | Cycles (d) | Rs (Ω·cm2) | Qf(Y0) × 10−3 (Ω−1·cm−2·sn) | nf | Rpore (Ω·cm2) | Qdl(Y0) × 10−3 (Ω−1·cm−2·sn) | ndl | Rct (Ω·cm2) | χ2 (×10−5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 7 | 43.85 | 15.37 | 0.31 | 87.35 | 19.19 | 0.22 | 714.86 | 1.27 |

| 35 | 40.30 | 12.64 | 0.42 | 66.79 | 18.14 | 0.45 | 470.69 | 0.47 | |

| 5Al | 7 | 48.35 | 16.47 | 0.35 | 90.34 | 23.47 | 0.22 | 727.43 | 1.87 |

| 35 | 57.64 | 24.67 | 0.51 | 140.33 | 22.22 | 0.35 | 972.32 | 3.47 | |

| 7Al | 7 | 41.33 | 20.13 | 0.34 | 80.79 | 27.94 | 0.41 | 850.86 | 1.74 |

| 35 | 51.35 | 32.47 | 0.50 | 167.97 | 34.78 | 0.35 | 1069.79 | 3.76 | |

| 9Al | 7 | 40.80 | 10.10 | 0.38 | 79.41 | 22.78 | 0.42 | 547.97 | 1.87 |

| 35 | 41.53 | 27.97 | 0.55 | 153.79 | 43.78 | 0.42 | 1035.53 | 2.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Li, D.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Q. Effect of Aluminum Content on the Corrosion Behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C Structural Steels in Marine Environments. Metals 2025, 15, 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111249

Wang S, Sun Z, Li D, Yu Q, Wang Q. Effect of Aluminum Content on the Corrosion Behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C Structural Steels in Marine Environments. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111249

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Suotao, Zhidong Sun, Dongjie Li, Qiang Yu, and Qingfeng Wang. 2025. "Effect of Aluminum Content on the Corrosion Behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C Structural Steels in Marine Environments" Metals 15, no. 11: 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111249

APA StyleWang, S., Sun, Z., Li, D., Yu, Q., & Wang, Q. (2025). Effect of Aluminum Content on the Corrosion Behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-C Structural Steels in Marine Environments. Metals, 15(11), 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111249