The Effect of Organic Compounds on Iron Concentration in the Process of Removing Iron from Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solution via Oxidation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experiment

2.3. Analysis and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

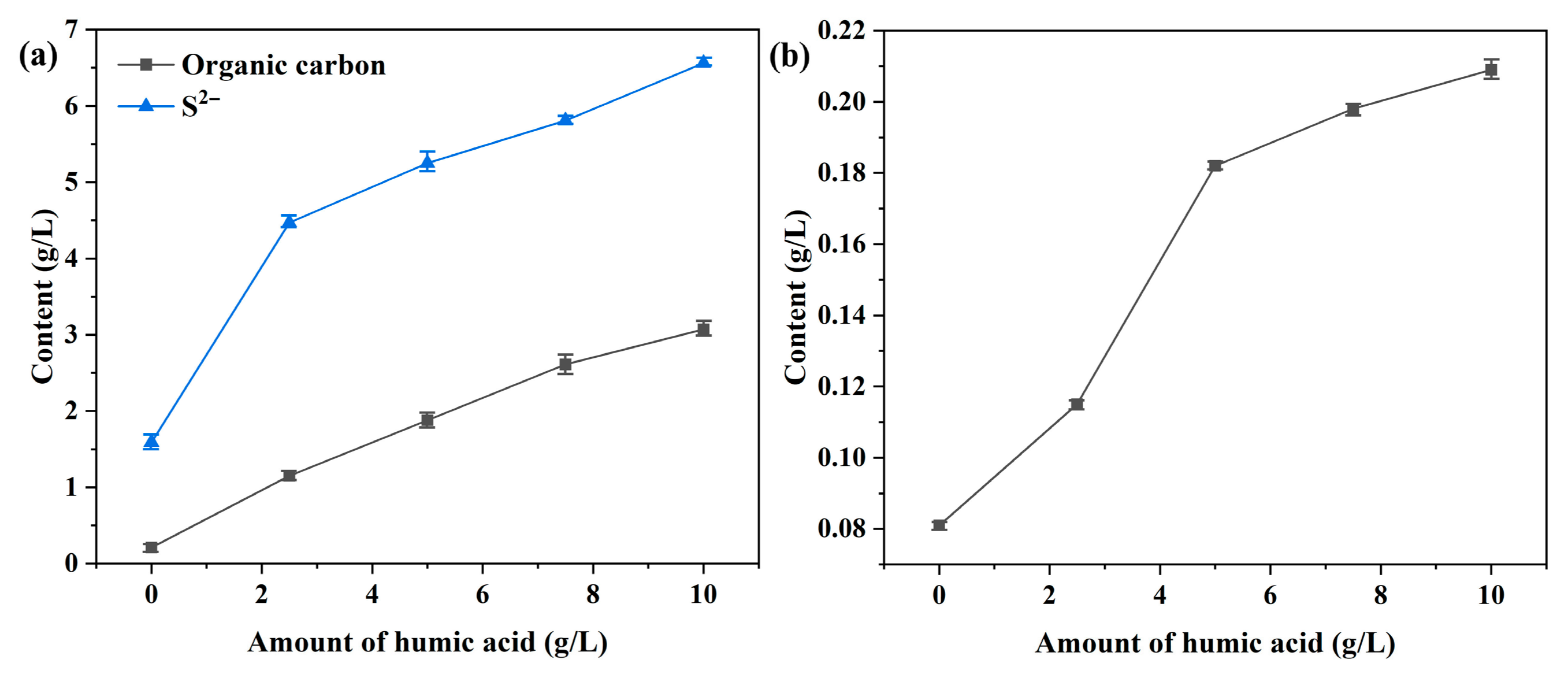

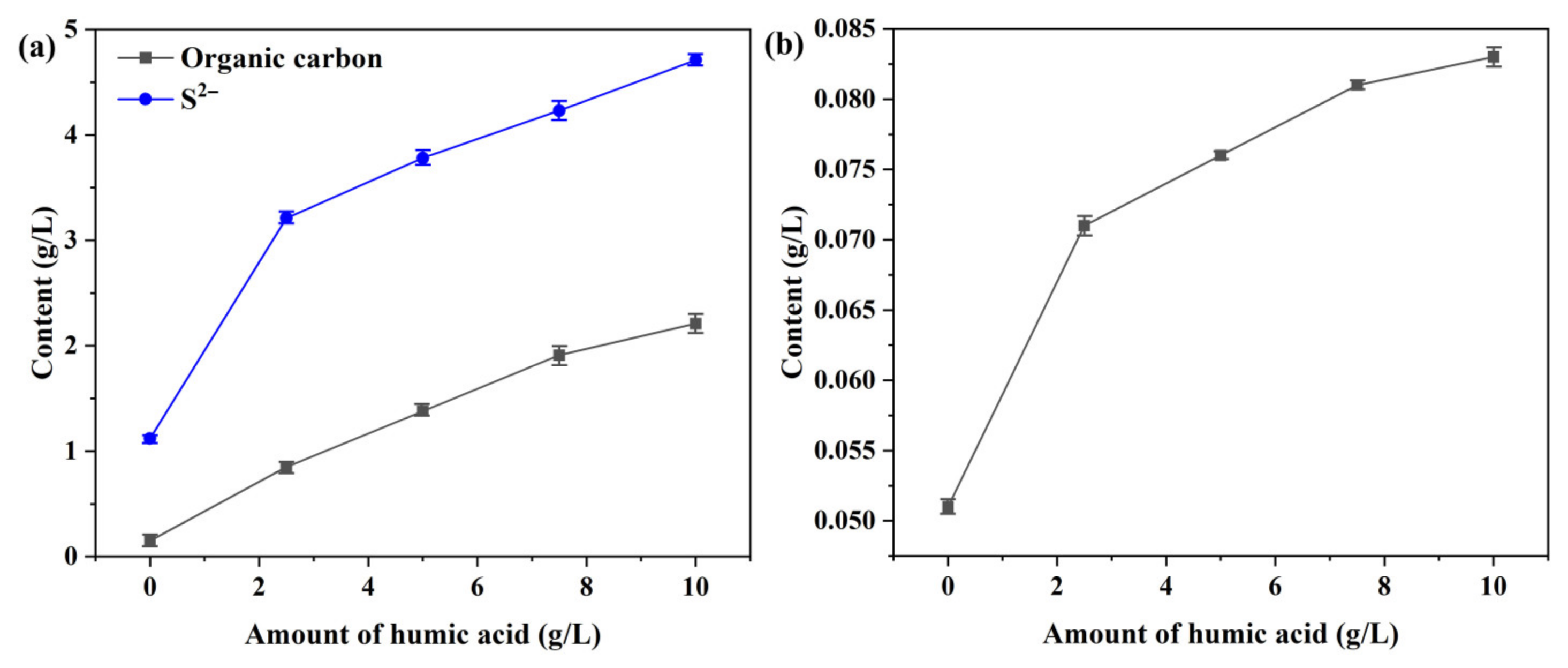

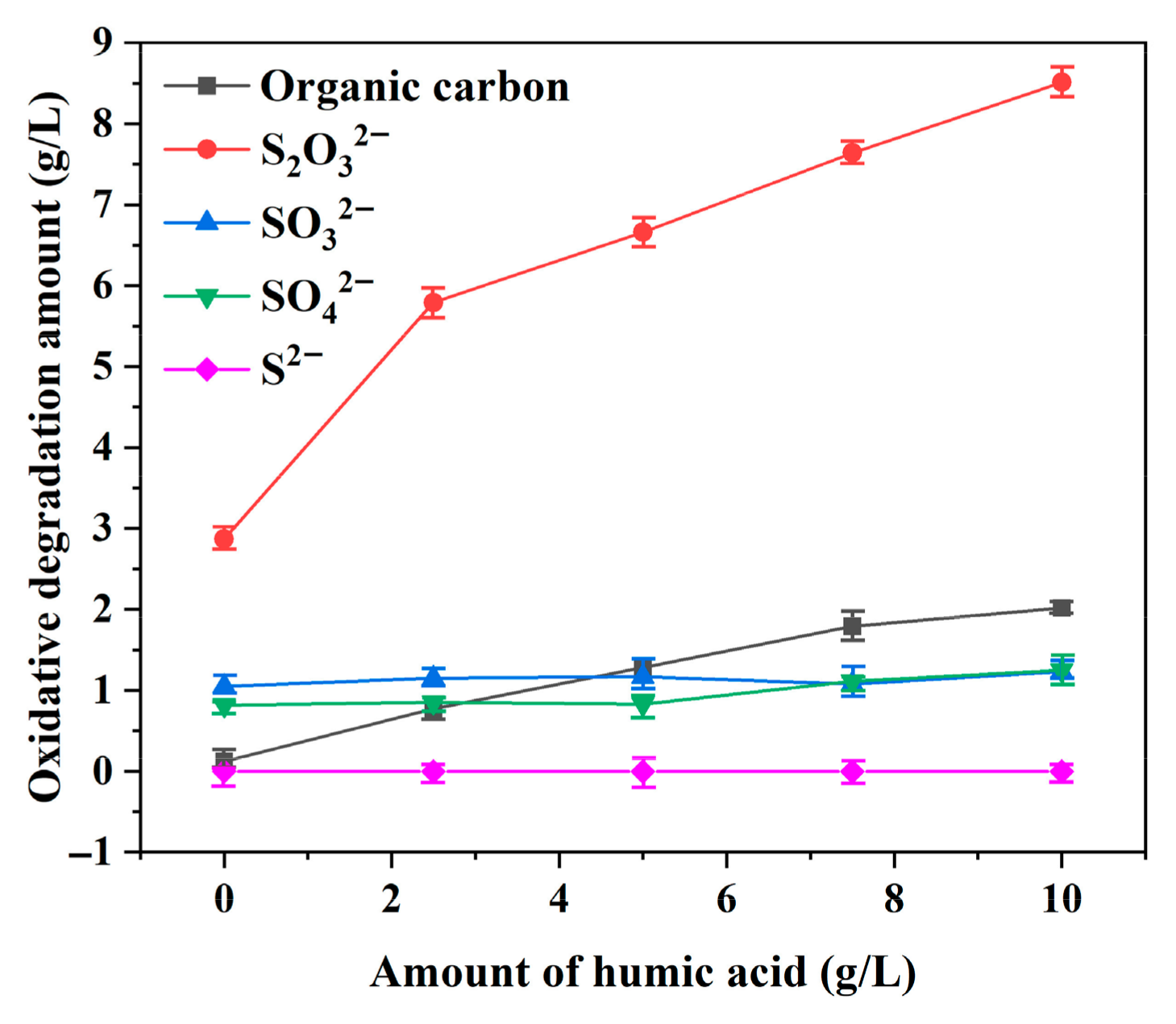

3.1. Effect of Organic Compounds on the Sulfur and Iron Content in Digested and Diluted Liquors

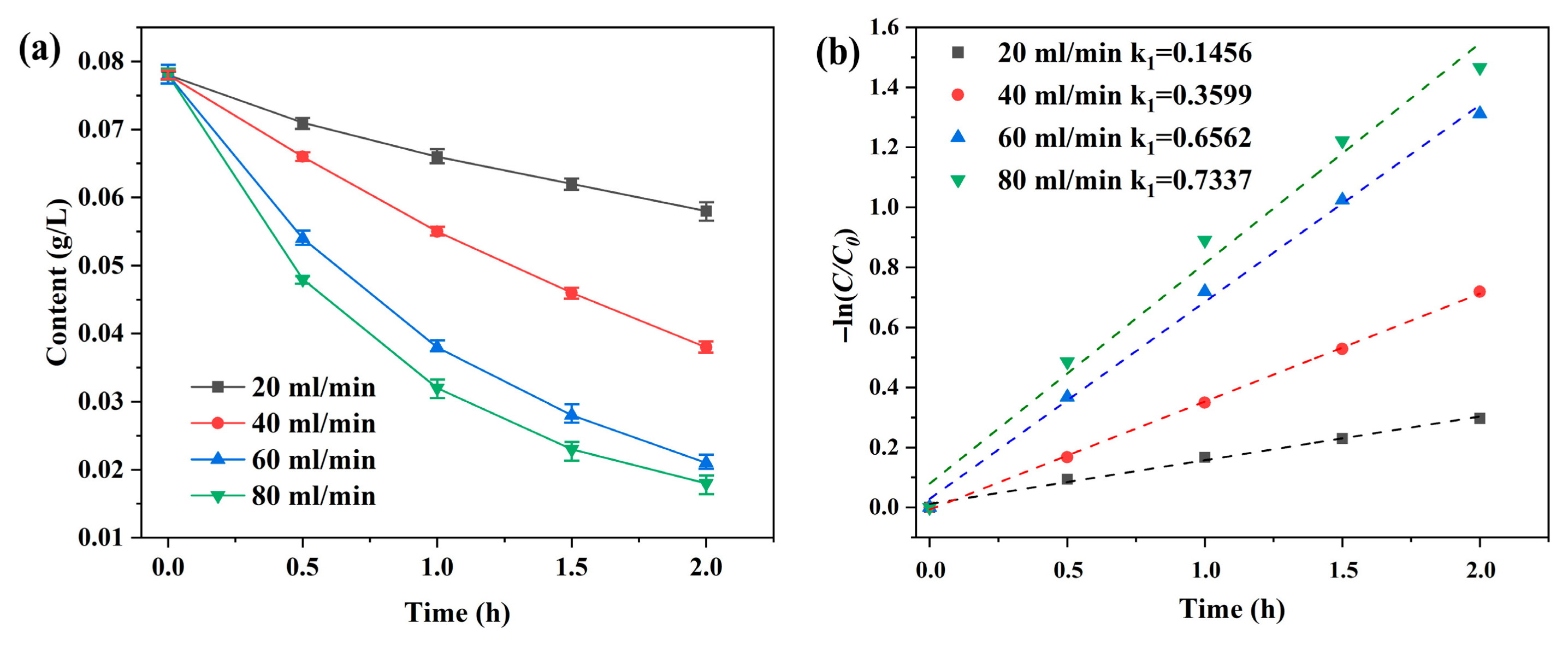

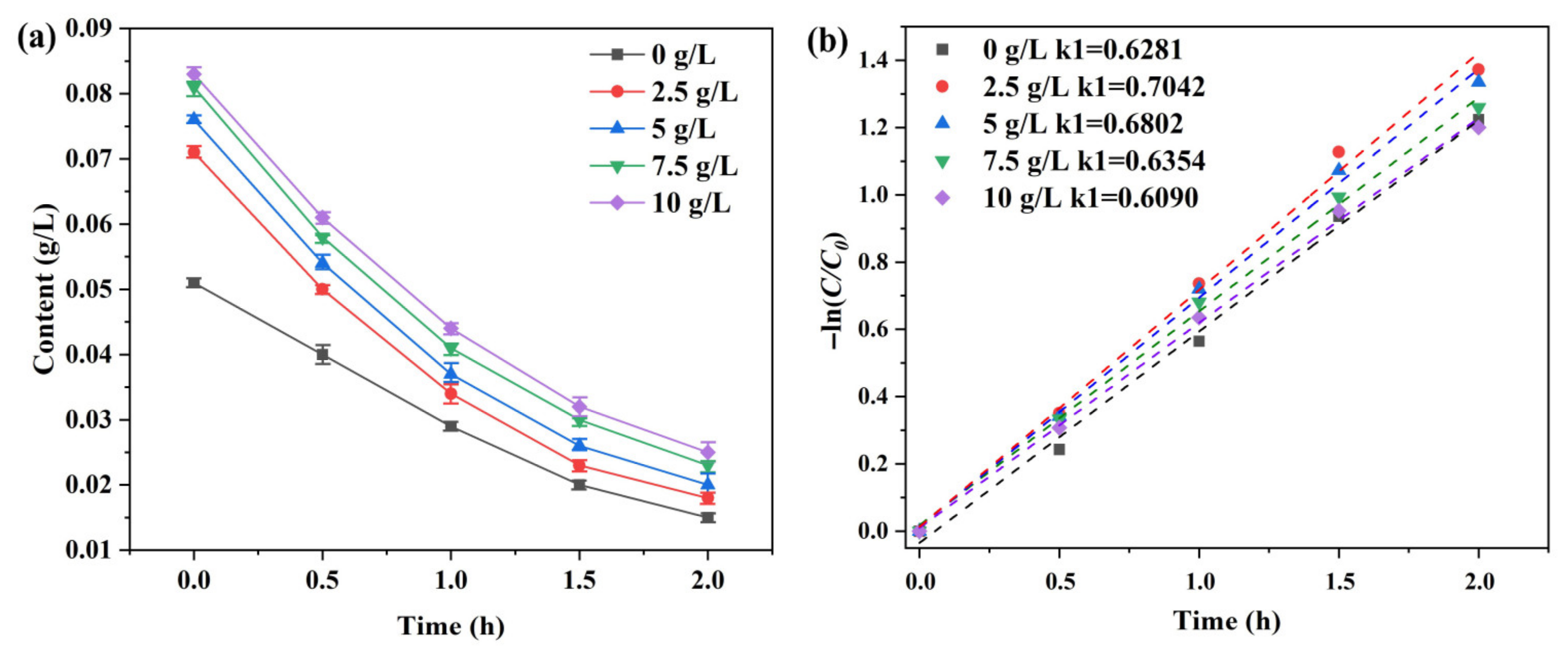

3.2. Removal of Iron from the Diluted Liquor via Atmospheric Oxygenation

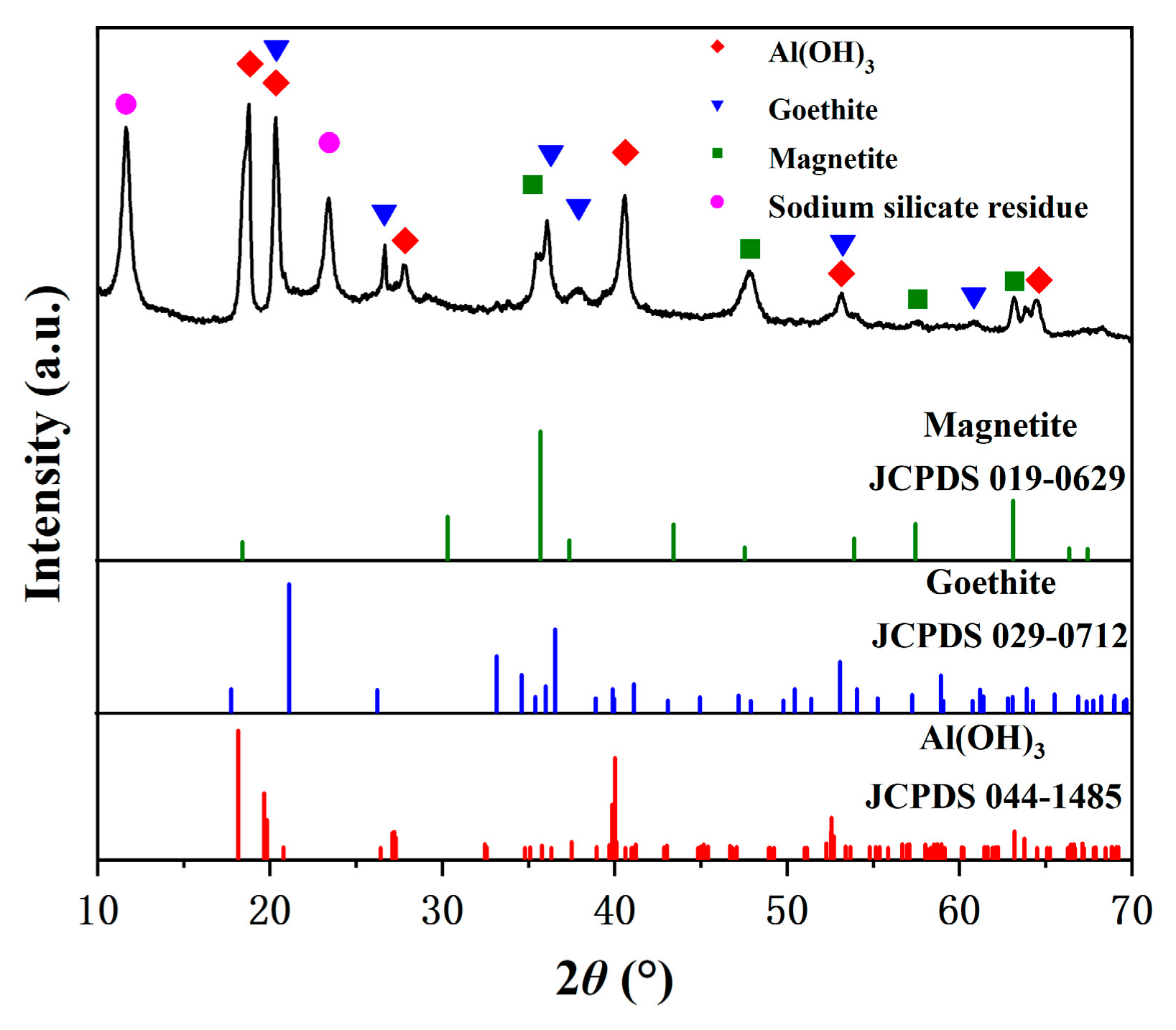

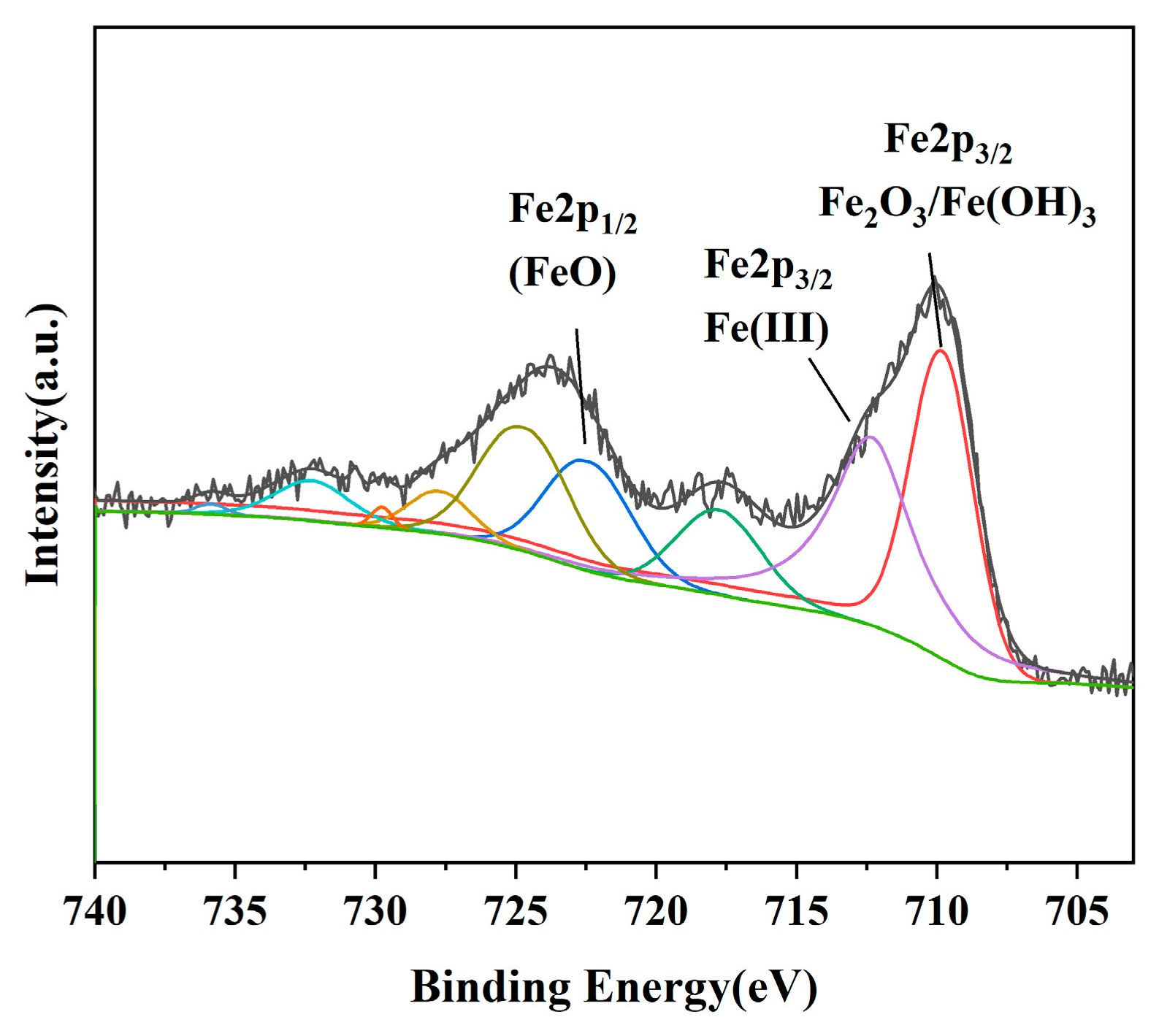

3.3. Characterization of the Iron Removal Precipitate from Oxidation

3.4. Mechanism Analysis

3.4.1. Mechanism of Organic Compounds’ Influence on Iron Content in Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solutions

3.4.2. Mechanism of Iron Removal via Oxygen Aeration in Diluted Solutions

4. Conclusions

- Under the high-temperature and highly alkaline digestion conditions of the Bayer process, fulvic acid and its transformed organic derivatives accelerate the dissolution of pyrite by complexing with iron ions, thereby disrupting the hydrophilic iron hydroxide (or ferrous hydroxide) film formed on the pyrite surface. This leads to a sharp increase in the iron concentration in the digested liquor. The iron content in the digestion solution increased by 1.6 times (from 0.08 to 0.208 g/L) when the amount of humic acid added increased from 0 to 10 g/L.

- After the cooling and dilution of the digested liquor (from 270 to 100 °C), the iron concentration in the diluted solution exhibited a positive correlation with the organic compounds content. Furthermore, the iron concentration in the diluted solution increased from 0.052 to 0.085 g/L when the content of humic acid added increased from 0 to 10 g/L. Complexation between iron ions and organic compounds increases the equilibrium iron concentration in the solution, with the majority (approximately 90%) of iron present being in Fe2+ form.

- The iron removal precipitate obtained via oxygen aeration contains a high amount of iron, predominantly in the Fe3+ form, with no coprecipitated iron–sulfur phases detected. Oxygen aeration oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+, which is less soluble under alkaline conditions, thereby reducing its equilibrium concentration in the solution. In the presence of organic compounds, iron showed a synergistic removal with organic compounds under oxidative conditions, demonstrating that atmospheric oxygen aeration is a promising method to use for the removal of iron and organic compounds in sodium aluminate solutions containing organic compounds, sulfur, and iron.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Geological Survey. Summary of Mineral Commodities of the United States Geological Survey; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.B.; Li, C.Y.; Qi, T.G.; Zhou, Q.S.; Liu, G.H.; Peng, Z.H. Reaction behavior of pyrite during Bayer digestion at high temperature. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2013, 23, 829–835. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.-J.; Tan, F.; Chen, Y.-L.; YIN, J.-G.; Xia, W.-T.; Huang, Q.-Y.; Gao, X.-D. Thermodynamic analysis of Na−S−Fe−H2O system for Bayer process. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 2046–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Chen, W.; Yang, Q. Corrosion behavior of four kinds of steels in sulfide-containing Bayer liquor. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2014, 45, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Chen, C.Y.; Li, J.Q.; Lan, Y.P.; Zhang, X.Q.; Yuan, J.J. Effect of Time on the Corrosion of Q345 Steel in Thiosulfate Sodium Aluminate Solution. Surf. Technol. 2018, 47, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, B.; Li, J.; Chen, C. Effects of Sodium Thiosulfate on Corrosion Dynamics of Q235 Steel in Alkaline Environment. Corros. Prot. 2018, 39, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.-H.; Gao, J.-L.; Li, X.-B.; Xu, S. Study on variation rule of iron in the aluminate solution after digestion process at high temperature by Bayer process. Min. Metall. Eng. 2007, 27, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, F.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z. Variation of mass concentration of iron in sulfur sodium aluminate solution. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2015, 46, 4398–4403. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-M.; Chen, X.-G.; Guo, J.-Q.; Huang, W.-G.; Hu, X.-L. Research on the behavior of iron in bayer liquor. Light Met. 2008, 4, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yin, J.; Chen, Y.; Xia, W.; Xiang, X.; Yuan, X. Simultaneous removal of sulfur and iron by the seed precipitation of digestion solution for high-sulfur bauxite. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 181, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-B.; Li, C.-Y.; Peng, Z.-H.; Liu, G.-H.; Zhou, Q.-S.; Qi, T.-G. Interaction of sulfur with iron compounds in sodium aluminate solutions. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Jin, L.-Y. Development and application of bauxite containing high sulfur. Light Met. 2010, 11, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q. Research of iron content of sulfur-rich bauxite in Bayer process after heat-exchange and filtration of green and pregnant liquors. Light Met. 2010, 8, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Y.-L.; Zhang, M.-N. Research progress on desulfurization technology of high-sulfur bauxite. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 3374–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-W.; Li, W.-X.; Ma, W.-H.; Yin, Z.-L.; Wu, G.-B. Comparison of deep desulfurization methods in alumina production process. J. Cent. South Univ. 2015, 22, 3745–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, G.; Loh, J.S.C.; Niemelä, K. Organic compounds in the processing of lateritic bauxites to alumina: Addendum to Part 1: Origins and chemistry of organics in the Bayer process. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 108, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardio, J.; Bhargava, S.; Prasad, J.; Akolekar, D.B. Catalytic wet oxidation of the sodium salts of citric, lactic, malic and tartaric acids in highly alkaline, high ionic strength solution. Top. Catal. 2005, 33, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Li, J.; Jin, H.; Mao, X.; Zhou, W. Morphology Change of Organics in Humic Acid During High Pressure Dissolution of Sodium Aluminate Solution. Hydrometall. China 2016, 35, 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tan, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, L. Preparation and characterisation of seed for simultaneous removal of sulphur and iron from sodium aluminate solution. Can. Metall. Q. 2023, 62, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Hou, H.; Lin, Y.; Yan, W.; Hu, X.; Zi, F. Study on the efficient removal of trace iron from sodium aluminate solution by the heterogeneous nucleation method. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 316, 121993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.-H.; Liu, G.-H.; Qi, T.-G.; Zhou, Q.-S.; Peng, Z.-H.; Shen, L.-T.; Wang, Y.-L.; Li, X.-B.; Zhang, Y.-M. Directional transformation of pyrite in sodium aluminate solution for desulfurization and the reduction of red mud based on electrochemical mechanism. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 522, 145926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-N.; Liu, Z.-W.; Yan, H.-W.; Wei, J.; Liu, S. Removal of organic compounds from Bayer liquor by oxidation with sodium nitrate. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 215, 105972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.-A.; Muntean, S.G.; Ianoș, R.; Racoviceanu, R.; Ianași, C.; Cseh, L. Adsorption of Anionic Dyes from Wastewater onto Magnetic Nanocomposite Powders Synthesized by Combustion Method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Guadalupe, H.; Ramiro, E.; Francisco, P.; Iván, A.; Mizraim, F.; Elia, G.; Julio, J.; Francisco, B. Surface Spectroscopy of Pyrite Obtained during Grinding and Its Magnetisation. Minerals 2022, 12, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-M.; Shen, S.-Y.; Myers, R. Wet carbonation and stabilities of Fe(II)-containing materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 163, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paola, C.; Margherita, S.; Laura, S.; Stefano, E. XRD, FTIR, and thermal analysis of bauxite ore-processing waste (red mud) exchanged with heavy metals. Clays Clay Miner. 2008, 56, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R. Electrochemical potential controlling flotation. Miner. Eng. 2003, 2, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevic, A.; Orlowska, E.; Kandioller, W.; Jirsa, F.; Keppler, B.K.; Tafili-Kryeziu, M.; Linert, W.; Krachler, R.F.; Krachler, R.; Rompel, A. Photoreduction of terrigenous fe-humic substances leads to bioavailable iron in oceans. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6417–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlowska, E.; Enyedy, É.A.; Pignitter, M.; Jirsa, F.; Krachler, R.; Kandioller, W.; Keppler, B.K. Β-o-4 type dilignol compounds and their iron complexes for modeling of iron binding to humic acids: Synthesis, characterization, electrochemical studies and algal growth experiments. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 11546–11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, G.; Wang, D. The mechanism of activation flotation of Pyrite depressed by Lime. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 1995, 26, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.-W.; He, G.-P. The Thermodynamic Handbook for Calculation at High Temperature in Solution; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 412–414. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.-Y. Principles of Non-Ferrous Metals Metallurgy; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1993; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar]

| Element wt% | Signal Type | Zone A | Zone B | Zone C | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | EDS | 9.46 | 23.95 | 7.42 | 13.61 | 9.01 |

| O | EDS | 55.45 | 34.58 | 56.00 | 48.68 | 12.21 |

| Na | EDS | 1.21 | 3.24 | 2.18 | 2.21 | 1.02 |

| Al | EDS | 20.57 | 7.05 | 24.48 | 17.36 | 9.15 |

| Si | EDS | 0.00 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 4.62 |

| S | EDS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| Fe | EDS | 13.32 | 23.18 | 9.91 | 15.47 | 6.89 |

| Total amount | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | - |

| Compound | Fe(OH)2 | Fe(OH)3 | FeS | FeS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility product Ksp | 1.95 × 10−17 | 9.11 × 10−37 | 4.83 × 10−18 | 6.66 × 10−25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, J.; Fu, D.; Xu, N.; Han, Q. The Effect of Organic Compounds on Iron Concentration in the Process of Removing Iron from Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solution via Oxidation. Metals 2025, 15, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111206

Hao J, Fu D, Xu N, Han Q. The Effect of Organic Compounds on Iron Concentration in the Process of Removing Iron from Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solution via Oxidation. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111206

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Jingyi, Daxue Fu, Na Xu, and Qing Han. 2025. "The Effect of Organic Compounds on Iron Concentration in the Process of Removing Iron from Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solution via Oxidation" Metals 15, no. 11: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111206

APA StyleHao, J., Fu, D., Xu, N., & Han, Q. (2025). The Effect of Organic Compounds on Iron Concentration in the Process of Removing Iron from Sulfur-Containing Sodium Aluminate Solution via Oxidation. Metals, 15(11), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111206