Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding

Abstract

1. Introduction

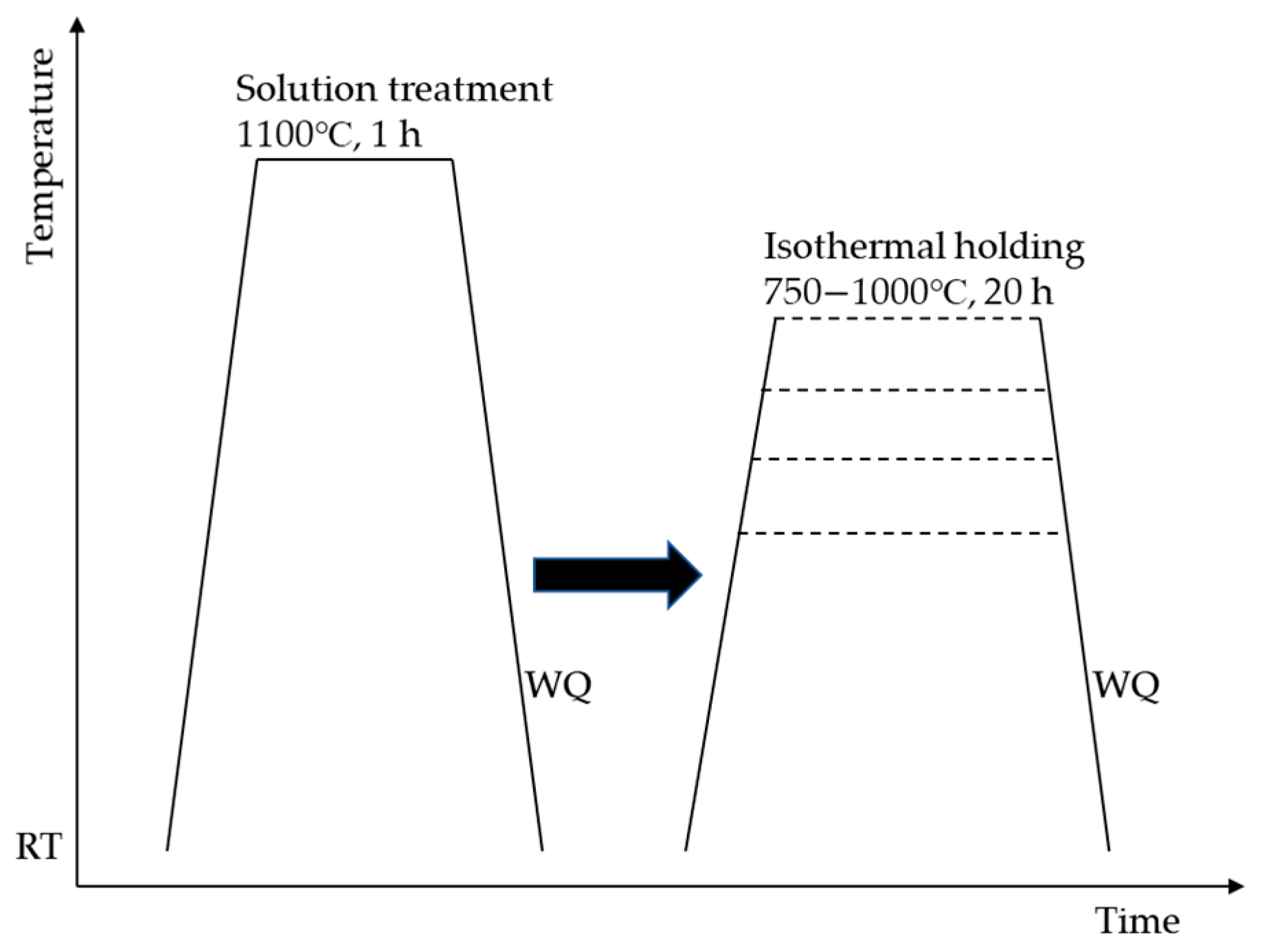

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure of As-Quenched Alloy

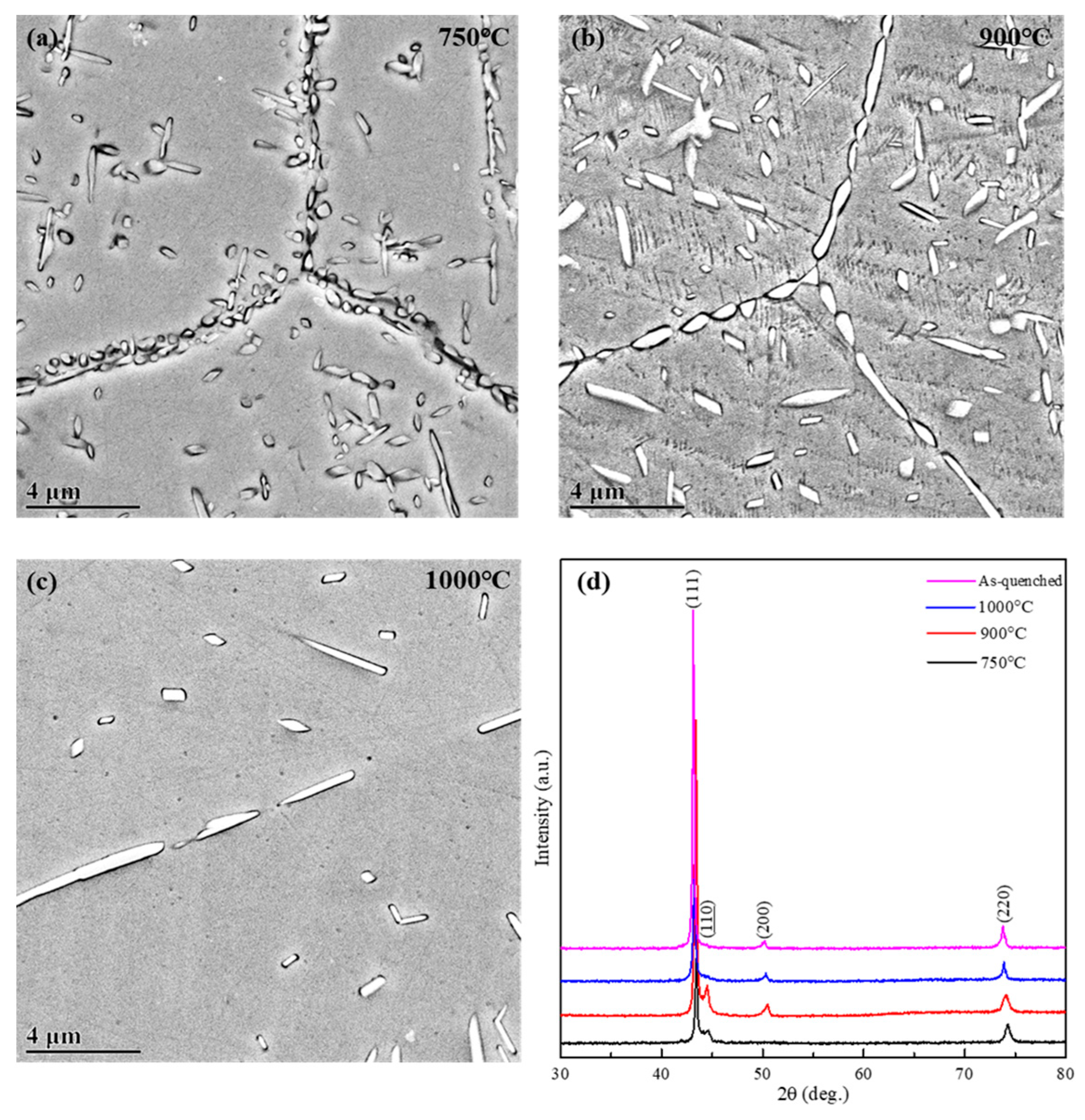

3.2. Formation of B2 Phase During Isothermal Holding

3.3. Elemental Distribution in Alloy After Isothermal Holding

3.4. Formation of Martensite Phase

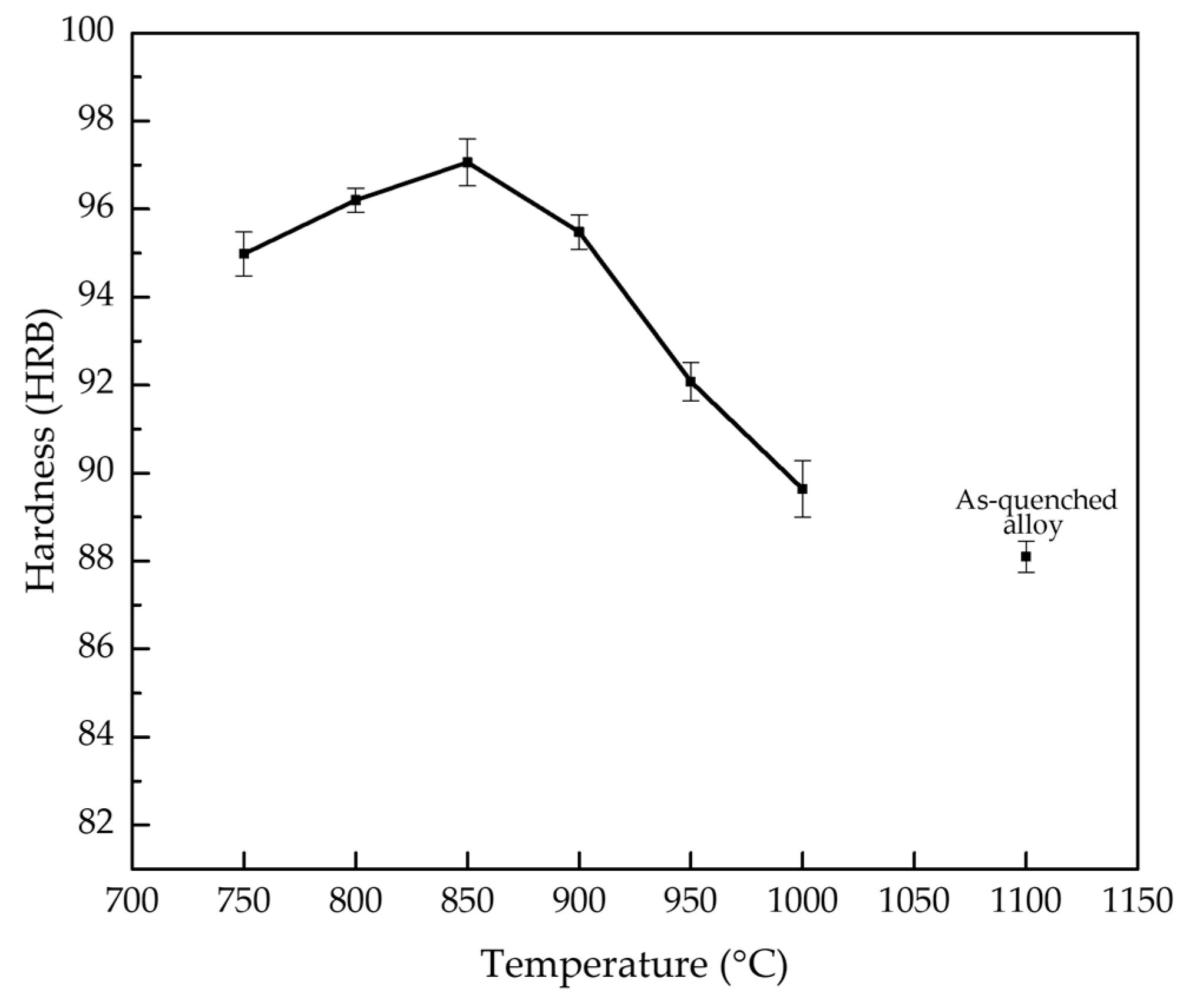

3.5. Hardness Evolution and Its Correlation with Phase Transformations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- In the as-quenched condition, the alloy exhibits a single-phase austenite (γ) microstructure with a low hardness of 88.1 HRB, consistent with the absence of secondary strengthening phases.

- Isothermal holding at intermediate temperatures between 750 °C and 900 °C promotes B2 precipitation accompanied by α′-martensite formation during cooling. These microstructural changes result in a significant hardness increase, with a maximum of 97.1 HRB at about 850 °C.

- No martensite was observed in the as-quenched alloy or in samples held above 900 °C, conditions characterized by either no B2 or only a low precipitate volume fraction. The Ms temperature for these alloys is predicted to be much below room temperature. This highlights the critical role of B2 precipitation in promoting martensitic transformation.

- Hardness increases in the 750–850 °C range due to combined B2 precipitation and martensitic transformation, but declines at higher temperatures because of precipitate coarsening, partial dissolution, and suppressed martensite formation.

- B2 phases exhibit a cube-on-cube orientation relationship with the α′ matrix, defined by (011)B2//(011)α′ and [100]B2//[100]α′.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Furuta, T.; Kuramoto, S.; Ohsuna, T.; Oh-Ishi, K.; Horibuchi, K. Die-hard plastic deformation behavior in an ultrahigh-strength Fe-Ni-Al-C alloy. Scr. Mater. 2015, 101, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, S.; Kawano, Y.; Mori, Y.; Kobayashi, J.; Emura, S.; Sawaguchi, T. Mechanical Properties and Deformation Behavior in Severely Cold-Rolled Fe-Ni-Al-C Alloys with Lüders Deformation-Overview with Recent Experimental Results. Mater. Trans. 2023, 64, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Simm, T.; Martin, T.; McAdam, S.; Galvin, D.; Perkins, K.; Bagot, P.; Moody, M.; Ooi, S.; Hill, P. A novel ultra-high strength maraging steel with balanced ductility and creep resistance achieved by nanoscale β-NiAl and Laves phase precipitates. Acta Mater. 2018, 149, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Morris, M.A.; Morris, D.G. Microstructure and mechanical behaviour of a Fe-Ni-Al alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 444, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Bai, Y.; Shibata, A.; Tsuji, N. Microstructures and mechanical property of a Fe-Ni-Al-C alloy containing B2 intermetallic compounds. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Roskilde, Denmark, 4–8 September 2017; p. 012020. [Google Scholar]

- Eleno, L.; Frisk, K.; Schneider, A. Assessment of the Fe-Ni-Al system. Intermetallics 2006, 14, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumak, I.; Richter, K.W.; Ipser, H. Isothermal sections in the (Fe, Ni)-rich part of the Fe-Ni-Al phase diagram. JPED 2008, 29, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.; Koch, C. The effect of composition and cooling rate on the structure of rapidly solidified (Fe,Ni)3Al-C alloys. J. Mater. Res. 1989, 4, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaple, S.; Baligidad, R.; Rao, S. Effect of alloying additions on the structure and mechanical properties of Fe3Al-1C intermetallic alloy. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2009, 62, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.; Sauthoff, G. Deformation behaviour of perovskite-type phases in the system Fe-Ni-Al-C. I: Strength and ductility of Ni3AlCx and Fe3AlCx alloys with various microstructures. Intermetallics 1997, 5, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, M.; Yuan, F.; Wu, X. Ultra-high tensile strength via precipitates and enhanced martensite transformation in a FeNiAlC alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 803, 140498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Liu, T. Grain boundary precipitation reactions in a wrought Fe-8Al-5Ni-2C alloy prepared by the conventional ingot process. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1998, 29, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, P.; Yuan, F.; Wu, X. Plastic deformation mechanisms in a severely deformed Fe-Ni-Al-C alloy with superior tensile properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarreal, J.; Koch, C. Metastable microstructures of rapidly solidified and undercooled Fe-Al-C and Fe-(Ni,Mn)-Al-C alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1991, 136, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Ding, H.; An, X.H.; Han, D.; Liao, X.Z. Influence of Al content on the strain-hardening behavior of aged low density Fe-Mn-Al-C steels with high Al content. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 639, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Badillo, E.; Dorantes Rosales, H.J.; Saucedo Muñoz, M.L.; Lopez Hirata, V.M. Analysis of Phase Transformations in Fe-Ni-Al Alloys Using Diffusion Couples of Fe/Fe-33at.% Ni-33at.% Al Alloy/Ni. Metals 2023, 13, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwarth, M.; Chen, G.; Rahimi, R.; Biermann, H.; Zargaran, A.; Duffy, M.; Zupan, M.; Mola, J. Aluminum-alloyed lightweight stainless steels strengthened by B2-(Ni, Fe) Al precipitates. Mater. Des. 2021, 206, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Niu, B.; Dong, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liaw, P.K. Coherent precipitation and stability of cuboidal B2 nanoparticles in a ferritic Fe-Cr-Ni-Al superalloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 2021, 9, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, I.; Karaca, H.E.; Nagasako, M.; Kainuma, R. Effects of aging temperature and aging time on the mechanism of martensitic transformation in nickel-rich NiTi shape memory alloys. Mater. Charact. 2020, 159, 110034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Palma, C.; Contreras-Piedras, E.; Cayetano-Castro, N.; Saucedo-Muñoz, M.; Lopez-Hirata, V.; Gonzalez-Velazquez, J.; Dorantes-Rosales, H. Effect of temperature and composition on NiAl precipitation and morphology in Fe-Ni-Al alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2017, 48, 5285–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahr, D. Stress-and strain-induced formation of martensite and its effects on strength and ductility of metastable austenitic stainless steels. Metall. Trans. A 1971, 2, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.K.; Srivastava, V.C.; Mahato, B.; Chowdhury, S.G. Microstructure-mechanical property evaluation and deformation mechanism in Al added medium Mn steel processed through intercritical rolling and annealing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 799, 140100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Chen, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, M.; Lai, Q.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, H. A high-strength heterogeneous structural dual-phase steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 12898–12910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yoshimura, T.; Mao, W.; Bai, Y.; Gong, W.; Park, M.-h.; Shibata, A.; Adachi, H.; Sato, M.; Tsuji, N. Tensile deformation of ultrafine-grained Fe-Mn-Al-Ni-C alloy studied by in situ synchrotron radiation X-ray diffraction. Crystals 2020, 10, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; van der Wolk, P.J.; van der Zwaag, S. Determination of martensite start temperature for engineering steels part II. Correlation between critical driving force and Ms temperature. Mater. Trans. 2000, 41, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroz, D.; Chrobak, D. Effect of internal strain on martensitic transformations in NiTi shape memory alloys. Mater. Trans. 2011, 52, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Y.; San Martín, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, W. A review of the thermal stability of metastable austenite in steels: Martensite formation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 91, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzaki, K.; Fukiage, T.; Maki, T.; Tamura, I. The effect of Ni content on the isothermal character of lath martensitic transformation in Fe-Ni alloys. In Proceedings of the Materials Science Forum, Millersville, PA, USA, 1990; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Northwood, D.O.; Liu, Y. A new empirical formula for the calculation of MS temperatures in pure iron and super-low carbon alloy steels. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 113, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, J.; Kunert, M. Prediction of the Martensite Start Temperature in High-Carbon Steels. Steel Res. Int. 2022, 93, 2100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K. Calculation of the effect of alloying elements on the Ms temperature in steels. J. Alloys Compd. 1995, 220, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Maurya, A.K.; Ishtiaq, M.; Kang, S.G.; Reddy, N.G.S. Knowledge Discovery in Predicting Martensite Start Temperature of Medium-Carbon Steels by Artificial Neural Networks. Algorithms 2025, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jung, M. Prediction of martensite start temperatures of highly alloyed steels. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2021, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Narayana, P.; Maurya, A.; Kim, H.I.; Hur, B.Y.; Reddy, N. Modeling the quantitative effect of alloying elements on the Ms temperature of high carbon steel by artificial neural networks. Mater. Lett. 2021, 291, 129573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Roca, P.M.; Medina, J.; Sobrero, C.E.; Avalos, M.C.; Malarria, J.A.; Baruj, A.L.; Sade, M. Effects of B2 nanoprecipitates on the phase stability and pseudoelastic behavior of Fe-Mn-Al-Ni shape memory alloys. MATEC Web Conf. 2015, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sun, D.; Ji, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z. Shape memory effect and martensitic transformation in Fe-Mn-Al-Ni Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, J.M.; Giordana, M.F.; Sobrero, C.E.; Malarría, J. Phase stability of three Fe-Mn-Al-Ni superelastic alloys with different Al: Ni ratios. SMJ 2021, 7, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, J.; George, E.P.; Dlouhy, A.; Somsen, C.; Wagner, M.-X.; Eggeler, G. Influence of Ni on martensitic phase transformations in NiTi shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 3444–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, H.H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.-Q. Influence of Ni4Ti3 precipitation on martensitic transformations in NiTi shape memory alloy: R phase transformation. Acta Mater. 2021, 207, 116665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Geng, Y.; Zuo, S.; Jin, X. Precipitation and its effects on martensitic transformation in Fe-Ni-Co-Ti alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, S837–S840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemoto, M.; Liu, Z.; Tsuchiya, K.; Sugimoto, S.; Bepari, M. Relationship between hardness and tensile properties in various single structured steels. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2001, 17, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlina, E.; Van Tyne, C. Correlation of yield strength and tensile strength with hardness for steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2008, 17, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.B.; Carter, C.B. Obtaining and Indexing Parallel-Beam Diffraction Patterns. In Transmission Electron Microscopy: A Textbook for Materials Science; Springer: New York, USA, 2009; pp. 283–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Rosas, B.J.A.; López, H.V.M.; Rivas, L.D.I.; J, D.R.H. Phase separation and coarsening of NiAl (β′) intermetallic in quench-aged Fe-Ni-Al alloys. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, V.O.; Saucedo, M.M.L.; Lopez, H.V.M.; Paniagua, M.A.M. Coarsening of β′ precipitates in an isothermally-aged Fe75-Ni10-Al15 alloy. Mater. Trans. 2010, 51, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.C.; Lee, K.H.; Lin, S.M.; Chien, S.Y. The observation of austenite to ferrite martensitic transformation in an Fe-Mn-Al austenitic steel after cooling from high temperature. MSF 2017, 879, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhao, A. Effect of austenitizing temperature and cooling rate on Ms temperature of Fe-Ni-Cr cast iron. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, J.; Wieczorek, A.; Opahle, I.; Maaß, B.; Drautz, R.; Eggeler, G. On the effect of alloy composition on martensite start temperatures and latent heats in Ni-Ti-based shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2015, 90, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, H.; Kajiwara, S. Effects of carbon content and ausaging on γ ↔ α′ transformation behavior and reverse-transformed structure in Fe-Ni-Co-Al-C alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1994, 25, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Fe | Ni | Al | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt.% | 74.5 | 20 | 4.5 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korir, R.C.; Huang, Y.-T.; Cheng, W.-C. Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding. Metals 2025, 15, 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101135

Korir RC, Huang Y-T, Cheng W-C. Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding. Metals. 2025; 15(10):1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101135

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorir, Rosemary Chemeli, Yen-Ting Huang, and Wei-Chun Cheng. 2025. "Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding" Metals 15, no. 10: 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101135

APA StyleKorir, R. C., Huang, Y.-T., & Cheng, W.-C. (2025). Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding. Metals, 15(10), 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101135